Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Low cloud variability was analyzed using ISCCP-H observations and the Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition method, revealing distinct cloud–meteorology relationships over land and ocean.

- Low clouds exhibit nonlinear trends; stratocumulus and cumulus are primarily sensitive to temperature changes, while stratus responds to mid-level humidity over ocean and surface sensible heat flux over land.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- Timescale-dependent analysis shows low cloud feedback cannot be fully captured by linear frameworks, calling for reconsideration of cloud–climate coupling in current models.

- These results provide observational constraints to improve cloud parameterization and climate projections.

Abstract

Low clouds significantly influence Earth’s radiation budget, but their climate feedback remains highly uncertain due to complex interactions with meteorological conditions across spatial and temporal scales. The cloud controlling factor framework is widely used to link meteorological variables with cloud properties. However, most studies assume a static, linear relationship, potentially obscuring the timescale-dependent responses. In this study, we apply the Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition method to ISCCP-H cloud observations and ERA5 data (1987–2016) to isolate low cloud amount across multiple intrinsic timescales and trends over global land and ocean. The trends show a nonlinear increase in stratocumulus (Sc) and a significant nonlinear decline in cumulus (Cu), while stratus (St) exhibits weaker trends. We categorize timescales short (≤1 year) for annual variations, medium (1–8 years) for interannual variability such as ENSO, and long (>8 years) for decadal and longer-term climate changes. It is found that Sc and Cu over land are primarily influenced by near-surface heating, while sea surface temperature and surface sensible heat flux (SHF) dominate over ocean at short timescales. SHF becomes dominant over land at medium timescales, largely reflecting ENSO-related induced surface anomalies. At long timescales, atmospheric stability and wind speed influence continental clouds, while SHF remains dominant over ocean. Trend components reveal that Sc and Cu are most sensitive to temperature changes, whereas St responds to mid-level humidity over ocean and SHF over land. These findings underscore the importance of timescale-dependent cloud–meteorology relationships to improve cloud parameterizations and reduce climate projection uncertainties. Overall, our results demonstrate that low cloud variability and trends cannot be explained by a single linear mechanism but instead arise from distinct meteorological controls that change across timescales, cloud types, and surface regimes.

1. Introduction

Clouds play a pivotal role in modulating Earth’s energy balance and hydrological cycle by reflecting solar radiation, trapping longwave radiation, and affecting precipitation patterns [1,2]. Among these, low clouds are particularly important due to their close coupling with temperature, surface fluxes, and lower tropospheric stability [3]. They are broadly categorized into stratocumulus (Sc), shallow cumulus (Cu), and stratus (St), covering approximately 30% of the global surface, and they exert a disproportionately large impact on planetary albedo [4]. Their high reflectivity and proximity to the surface result in a net cooling effect, partially offsetting the warming induced by greenhouse gases [5]. Although low clouds generally cool the climate, different types of low clouds have different extents of radiative effects due to their distinct formation mechanisms and primary locations [6].

The Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC AR6) highlights low cloud feedback, defined as the change in the radiative effect of low clouds in response to global warming, as a critical yet highly uncertain component of the climate system [7,8,9]. This feedback not only influences global mean temperatures but also modulates regional climate patterns, including shifts in tropical rainfall, expansion of the subtropical dry zone, and variability in the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) [10,11]. However, large uncertainties in both the sign and magnitude of low cloud feedback make it one of the dominant contributors to the spread in climate sensitivity estimates [12,13]. The uncertainty primarily stems from two sources. First, despite their strong radiative impact, long-term trends in low cloud amount (LCA) remain poorly understood, particularly as different low cloud types may respond in distinct or even opposing ways to warming [14,15]. Second, the physical processes regulating low cloud formation and evolution are not well represented in current climate models, leading to large biases in simulating their macro and microphysical properties [16,17]. Addressing these challenges requires an improved understanding of both LCA trends and their meteorological drivers to better quantify low cloud responses to climate change.

Satellite observations have clearly revealed pronounced spatial and temporal heterogeneity in LCA across regions in the context of global warming [18,19]. Most previous studies have investigated long-term variations in LCA using traditional linear analyses, either by comparing multi-decadal mean differences to identify regional increases or decreases [16,20], or by applying fixed-slope linear regression models to estimate trend rates over time [21,22]. While these methods are intuitive and straightforward, they often fail to capture the inherently non-stationary behavior of low clouds in response to evolving climatic conditions. Such approaches also often overlook critical features, such as trend accelerations, decelerations, and potential regime shifts, which may be central to understanding the mechanisms behind low cloud variability and feedback [23]. Addressing these limitations requires methods capable of identifying and isolating short-term fluctuations driven by weather processes from nonlinear longer-term trends associated with climate feedbacks. Moreover, merely documenting nonlinear trends is insufficient to understand their origins; it is equally important to interpret these changes within the context of large-scale meteorological conditions.

Numerous studies have adopted the cloud controlling factor (CCF) framework to link large-scale thermodynamic and dynamic conditions to the physical and radiative properties of low clouds [16,24,25]. In this framework, CCFs serve as proxies for key meteorological drivers, enabling the quantification of relationships between environmental variability and cloud behavior [26,27,28]. For instance, a higher estimated inversion strength (EIS) suppresses the entrainment of dry free-tropospheric air, favoring increased LCA [29,30]. Cooler sea surface temperature (SST) promotes Sc formation, whereas warmer SST enhances convective mixing that dissipates low clouds [31,32]. Vertical velocity further differentiates regimes: persistent subsidence over ocean compresses boundary layers and favors marine LCA formation, while ascending motions over land caused by surface heating or orographic lifting, support transient Cu [33]. Relative humidity near the surface regulates low clouds condensation: marine regions typically maintain high relative humidity due to continuous moisture supply, while over land, lower relative humidity contributes to generally reduced LCA [34]. Further, near surface wind speed also influences low cloud dynamics, with stronger winds enhancing turbulent mixing and often increasing LCA [15,32]. Different types of low cloud exhibit distinct sensitivities to specific meteorological drivers, resulting in varied contributions to cloud feedback across different climate regimes [6,35]. However, the traditional CCF method often assumes that cloud sensitivities to meteorological variables are temporally invariant [16,20]. This simplifying assumption neglects the fact that low cloud responses to meteorological drivers may change considerably across timescales [36]. Furthermore, these relationships are often derived from coarse spatial and temporal averages, which can obscure important regional and regime-specific processes critical for accurate diagnosis and modeling of cloud feedback [37]. It has been increasingly suggested that the response of low clouds to meteorological drivers varies substantially across different temporal scales based on observational evidence. For example, Szoeke et al. [38] demonstrated that EIS explains 29% of the variance in LCA at decadal scales, increasing to 39% at annual scales, with a more pronounced influence on Sc compared to on Cu. Similarly, SST explains up to 52% of LCA variability on annual timescales, but only about 30% at decadal scales [38,39]. Although the influence of vertical velocity is generally weaker than that of thermodynamic factors, its contribution to long-term variability is non-negligible, with explanatory power at the decadal scale nearly twice that at the annual scale [40]. These findings highlight the importance of investigating the multiple timescale sensitivities of low clouds to different meteorological drivers.

Thus, advancing our understanding of the diverse behaviors of low cloud regimes across timescales and meteorological conditions is critical for improving cloud representations in models and narrowing uncertainties in projections of cloud feedback and climate sensitivity. This study aims to address the following key questions: (1) What are the characteristics and differences in the nonlinear trend evolution of the three major low cloud types (Sc, Cu, and St) over ocean and land? (2) What are the dominant meteorological drivers governing the formation of three low cloud types across different timescales, and how do the underlying physical mechanisms differ between oceanic and continental environments? To answer these questions, we utilize high-resolution, continuous ISCCP-H satellite observations of low clouds from 1987 to 2016, applying the Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition (EEMD) method to isolate intrinsic multi-timescale variations in LCA along with long-term trend components. From the extracted trend components for the three low cloud types, we systematically analyze the spatiotemporal evolution of nonlinear trends. Based on the LCA and meteorology variations at distinct timescales, we quantitatively evaluate the relative contributions of six key CCFs to low cloud evolution. This study reveals the nonlinear trend characteristics of different low cloud types and demonstrates that their dominant meteorological drivers vary substantially across timescales and between oceanic and continental regimes. These findings provide a robust quantitative foundation for understanding the timescale-dependent sensitivity of low clouds to climate change. The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the datasets and the key methods; Section 3 presents the multiple timescales evolution of low clouds and the influence of meteorological drivers; Section 4 offers a discussion; and Section 5 shows conclusions.

2. Materials and Methods

In this study, we use ISCCP-H satellite data and the EEMD method to analyze the distribution and multi-timescale variability of three typical low cloud types over ocean and land. We first identify the nonlinear trend evolution of each cloud type based on the extracted trend components. Then, by examining variations across different timescales, we quantify the relative contributions of six key CCFs, revealing the dominant drivers of low cloud changes under climate change. The following context provides detailed descriptions of the data sources for the meteorological factors and satellite-observed low cloud types, the EEMD method and nonlinear trend extraction procedures, and the regression framework used to quantify the contributions of large-scale CCFs to variations in LCA.

2.1. Cloud Controlling Factors Data

The fifth-generation Global Atmospheric Reanalysis Dataset developed by the European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasts (ERA5) provides high-precision, long-term meteorological and climate data. The ERA5 dataset provides monthly data with 37 pressure-level parameters at a 0.25° × 0.25° resolution, which we re-grid to a 1° × 1° resolution by using bilinear interpolation to ensure consistency with satellite dataset. We used monthly meteorological factors from 1987 to 2016 from ERA5 reanalysis datasets including SST, 2 m surface temperature (T2m), vertical velocity at 850 hPa (ω850), 10 m wind speed (WS), surface sensible heat flux (SHF), and relative humidity at 700 hPa (RH700). The calculation of EIS is shown in Equation (1) [30]:

where the lower-tropospheric stability (LTS) is calculated as the potential temperature difference between the surface and 700 hPa level. Meanwhile, represents the moist adiabatic lapse rate at 850 hPa, with and denoting the heights of 700 hPa level and the lifting condensation level, respectively. These CCFs can comprehensively reveal the generation mechanism of low clouds from the perspectives of dynamic and thermodynamic.

2.2. ISCCP Cloud Types Dataset

The International Satellite Cloud Climatology Project released the latest generation dataset (ISCCP-H) in 2019. The cloud detection and cloud-type classification in the ISCCP-H dataset are based on pixel-level satellite passive radiance observations and radiative inversion procedures. First, the observed radiances undergo spatiotemporal tests to estimate clear-sky radiance values, which are then combined with auxiliary products to generate clear-sky radiances for each pixel at each time globally. Second, when the observed satellite radiances in the infrared or visible channels deviate significantly from the estimated values based on various infrared and visible threshold combinations, the pixel is classified as cloudy. Third, for pixels identified as cloudy, cloud-top temperature is retrieved from infrared brightness temperatures, and relevant cloud properties are inferred using atmospheric temperature profiles. This dataset offers higher spatial resolution and a longer temporal span, providing key physical parameters such as cloud top pressure, cloud top temperature, and cloud water path. The classification of cloud types in this study follows the standard algorithm used in the ISCCP-H dataset rather than being manually redefined. ISCCP-H differentiates cloud types based on the joint histogram of cloud-top pressure (CTP) and cloud optical thickness (τ), following the operational scheme described in Young et al. [41]. According to this classification framework, clouds are first separated into high (CTP < 440 hPa), middle (440 ≤ CTP < 680 hPa), and low clouds (CTP ≥ 680 hPa). Optical thickness is further divided into thin (τ ≤ 3.6), intermediate (3.6 < τ ≤ 23), and thick (τ > 23) categories, where CTP ≥ 680 hPa, τ ≤ 3.6 is Cu, CTP ≥ 680 hPa, and 3.6 < τ ≤ 23 is Sc, while CTP ≥ 680 hPa and τ > 23 is St. In this study, the fractional cover of each low-cloud category was directly extracted from the corresponding ISCCP-H histogram bins. In the previous D-series ISCCP data, the long-term trends in cloud cover are subject to artifacts, mainly the effect of changes in satellite zenith angles during the increase in the number of geostationary satellites over the past few decades [42]. However, the latest version of the ISCCP-H cloud cover product has been compared with other satellite datasets and finds good consistency in the study of global cloud cover trends [43]. Therefore, the long-term observations of ISCCP-H have been widely used in the study of long-term trends in cloud cover [43,44,45]. Here, we use monthly mean LCA from the ISCCP-H dataset for the period from 1987 to 2016 to analyze the spatiotemporal variations in three typical low cloud types within the latitude range of 50°N to 50°S and at a spatial resolution of 1° × 1°. We investigate the differences and trend characteristics of key meteorological controlling factors that govern the evolution of different low cloud types using multiple timescale method.

2.3. EEMD Method and Nonlinear Trend Calculation

The EEMD method is a time series analysis technique that decomposes a data series into a set of intrinsic mode functions (IMFs), each representing oscillatory components at different timescales, and a residual term representing a long-term trend change [46]. It introduces ensemble averaging with added white noise, thereby effectively mitigating the issue of mode mixing in the original Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) and allowing clear separation of interannual, decadal, and trend components [47]. EEMD does not rely on any predefined basis functions but instead extracts variability modes purely based on the data itself. It works by adding independent white noise of varying amplitudes to the original time series, performing multiple perturbations followed by mode decomposition. It has been widely used in the analysis of climate change, oceanic, and atmospheric signals [23,46,48]. We apply the EEMD method to perform multi-scale decomposition of the monthly mean cloud amount series of three types of low clouds over ocean and land for the period 1987–2016. The mathematical expression of the EEMD is as follows:

where represents the original time series, is the j IMF, n is the total number of IMF, and is the trend term. The number of IMF components depends on the length m of the original time series, and it is commonly estimated using the following formula:

where represents the floor function, which returns the greatest integer less than or equal to a given value. We obtain a total of seven IMF components and a trend term in this study.

To quantitatively describe the role of each IMF component at different timescales, we further calculate the cycle and the variance contribution (Con) of each IMF to the total variability. The cycle is derived by averaging the time intervals between consecutive extrema, which reflects the dominant timescale of the mode. The Con is calculated using the following formula [49]:

where represents the variance of the j IMF component, and is the variance of the trend term.

Based on the temporal properties of the trend component extracted using the EEMD method, we computed the cumulative nonlinear trend of cloud cover at each grid point by subtracting the value in 1987 from the value at each subsequent year. This allows us to assess relative changes in the nonlinear trend over time, using 1987 as the reference. To further characterize the rate at which this nonlinear trend evolves, we approximated its first derivative using a central difference method, calculated as the difference between the values at the adjacent years divided by two [23,50].

2.4. Quantifying the Relative Contribution of CCFs to Low Cloud Across Timescales

We aimed to quantify the relative contributions of different meteorological factors to LCA variations across multiple timescales. To achieve this, we first applied the EEMD method to decompose both the LCA of the three low cloud types and the large-scale controlling meteorological variables for the period of 1987–2016, respectively. We then classified the seven decomposed IMFs into three categories of timescales based on their cycles. In this study, the short timescale includes all components with periods less than one year, mainly reflecting intra-seasonal and annual fluctuations. The medium timescale includes components with periods between one and eight years, primarily associated with interannual variability such as ENSO [51,52]. The long timescale includes components greater than eight years, representing decadal to long-term climate background changes. We then used stepwise linear regression to compute the partial correlation coefficients between each meteorological factor and LCA at different timescales. The specific calculation formula is shown below [53]:

where denotes the partial correlation coefficient. All variables were normalized prior to regression analysis to eliminate the influence of unit differences. The correlation coefficients not statistically significant at the 95% confidence level (i.e., p > 0.05) were set to zero. Over ocean, the six selected meteorological factors include SST, EIS, ω850, WS, SHF, and RH700. Over land, SST is replaced by T2m, while the other variables remain unchanged. Based on the obtained partial correlation coefficients and the variability of each meteorological factor, we further calculated their relative contributions to low cloud variations. The corresponding formula is given below:

where represents the relative contribution rate, and is the variance of the meteorological factor i.

3. Results

3.1. Distribution of Low Cloud and EEMD Analysis

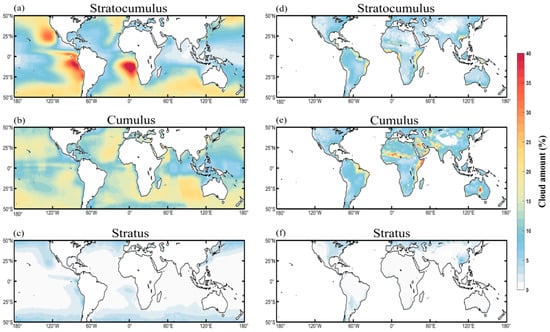

Figure 1 illustrates the spatial distributions of the three low cloud types, i.e., Sc, Cu, and St, over both ocean and land for the study period. Over ocean, Sc exhibits the highest coverage, forming extensive and persistent decks in the subtropical eastern Pacific and Atlantic, particularly along the west coasts of South America and southern Africa. In these regions, Sc frequency exceeds 35%, highlighting the dominance of marine boundary layer clouds in cold upwelling zones [54]. In contrast, Sc coverage is minimal in the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), where deep convection suppresses low cloud formation (Figure 1a). Cu clouds are more broadly distributed across the tropical and subtropical ocean, especially in the trade wind region, with relatively stable occurrence rates of around 20% [55]. Unlike Sc, Cu shows enhanced occurrence frequency within the ITCZ in Figure 1b. As shown in Figure 1c, St clouds are relatively rare over ocean, primarily confined to mid-to-high latitudes (>40°), such as the Southern Ocean and North Pacific, where large-scale synoptic systems prevail [56]. Their frequency remains below 10%, and they are nearly absent from tropical and subtropical regions.

Figure 1.

Three types of low cloud distribution from 1987 to 2016 over ocean and land: (a) stratocumulus for ocean, (b) cumulus for ocean, (c) stratus for ocean, (d–f) same as (a–c) but for land.

Over land, LCA is generally much lower than over ocean, primarily due to limited moisture availability. Among the three types, Cu clouds are the most prevalent over land, with occurrence frequencies reaching up to 15% in regions such as the Sahel region to South Sudan, the Arabian Peninsula, central Australia, and southeastern Africa in Figure 1e [6]. In contrast, Sc clouds are far less extensive than over ocean and are largely confined to narrow coastal zones, including the eastern coasts of South America, southern Africa, and eastern China. These continental Sc regions often represent landward extensions of the adjacent subtropical marine Sc decks, highlighting the continuity of cloud regimes across the land–sea boundary under oceanic influence (Figure 1d) [57]. St clouds are the least frequent over land, mainly occurring at high-latitude regions such as Siberia, northern Canada, and Alaska. Interestingly, their coverage slightly exceeds that over ocean at the same latitudes (Figure 1f), likely due to persistent low-level thermal inversions and strong static stability during the cold season, which are conducive to their formation [58]. It should be clarified that the present study focuses exclusively on tropospheric low cloud systems. Stratospheric clouds, including polar stratospheric clouds, occur at much higher altitudes above approximately 15–20 km, form under extremely low temperatures, and possess distinct microphysical and radiative characteristics [59]. Although these clouds are scientifically important in atmospheric chemistry and climate processes, their formation mechanisms, thermodynamic environments, and climatic impacts differ fundamentally from those of tropospheric low clouds. Therefore, stratospheric cloud types are not included in the scope of this analysis.

According to Figure 1, different types of low clouds exhibit distinct spatial distributions, with pronounced contrasts between oceanic and continental regions. To further explore their temporal variations, we applied the EEMD method described in Section 2.3 to decompose the monthly LCA time series into intrinsic components corresponding to different timescales. This decomposition allows us to isolate dominant variability patterns and identify long-term trends for each low cloud type over both ocean and land. Figure 2 presents the EEMD results for the three low clouds over ocean, while Figure 3 shows the corresponding decomposition over land. A summary of the dominant cycle and the percentage of total variance explained by each IMF and residual trend term is provided in Table 1.

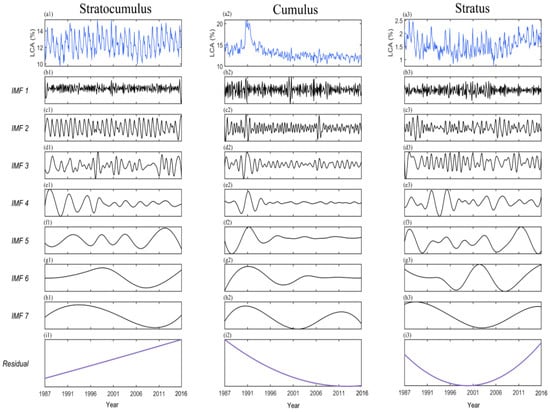

Figure 2.

The EEMD map of the monthly average low cloud amount over ocean. The blue solid lines represent the original time series distributions of the three types of low cloud amount, and each black solid line represents the time series distributions of the decomposed components at different intrinsic mode functions (IMFs); the purple solid line is the residual trend term. (a1–i1) for stratocumulus, (a2–i2) for cumulus, (a3–i3) for stratus.

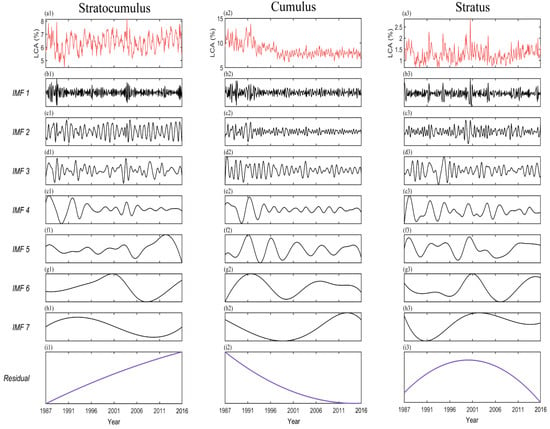

Figure 3.

The EEMD map of the monthly average low cloud amount over land. The red solid lines represent the original time series distributions of the three types of low cloud amount, and each black solid line represents the time series distributions of the decomposed components at different intrinsic mode functions (IMFs); the purple solid line is the residual trend term. (a1–i1) for stratocumulus, (a2–i2) for cumulus, (a3–i3) for stratus.

Table 1.

The cycle and variance contributions of the IMF components and residuals of the three types of low clouds over ocean and land.

Over ocean, Figure 2(b1–d3) show that the first three IMFs (IMF1–IMF3) predominantly capture the high-frequency of intra-seasonal oscillations with periods shorter than across all three low cloud types. These high-frequency modes are particularly dominant in Sc and St, accounting for 84.18% and 59.56% of their total variance, respectively. Among them, IMF2, characterized by a period of approximately 12 months, represents the primary annual cycle and contributes 61.43% of the variance in Sc and 30.08% in St, indicating strong seasonality in these two cloud types. IMF1, with a period of about 6 months, captures sub-seasonal fluctuations and contributes 17.78% of the variance in Sc and over 20% in St. In contrast, as shown in Figure 2(b2–i2), the temporal evolution of Cu is dominated by low-frequency and trend components, with the combined variance explained by high-frequency components (IMF1–IMF3) being only 12.53%, significantly lower than for Sc and St. Specifically, IMF5, with a period of about 90 months, accounts for 18.27% of the variance, while the residual trend term contributes as much as 56.51%. These findings suggest that Cu over ocean is primarily influenced by decadal-scale modulations and long-term trends in contrast to the strong seasonal cycle observed in Sc and St. The pronounced differences in timescales among these cloud types may be attributed to their typical formation regions and associated meteorological backgrounds. Sc and St are mainly found in cold ocean regions such as the eastern subtropics, where seasonal variations in SST and upward motion jointly drive their strong seasonality [32]. In contrast, Cu tends to occur in tropical deep convection zones or areas with weak boundary layer stability, where its formation is more strongly influenced by large-scale tropical circulations and exhibits a greater cumulative response [6].

The multi-scale structures of three low cloud types over land differ markedly from those observed over ocean. As shown in Figure 3(b1–e1), Sc over land remains dominated by high-frequency fluctuations, with the first three IMFs jointly accounting for 69.46% of the total variance. Among these, IMF2 as the dominant mode contributes 43.24%, which is notably lower than the 61.43% contribution observed in oceanic Sc, indicating a weaker annual cycle signal over land. Moreover, the residual trend component for continental Sc contributes 7.16% of the variance, nearly three times that of the ocean, suggesting a stronger influence of land-surface processes on long-term variability. St clouds over land also exhibit pronounced intra-seasonal variability (Figure 3(b3–h3)), with IMF1 (6-month period) alone contributing 40.14% of the total variance, substantially higher than the 20.54% seen in oceanic St. IMF2 further contributes 23.09%, resulting in a combined high-frequency variance of 63.23%. In contrast, the residual trend is just 0.23%, much lower than the 25.84% observed over ocean, underscoring a sharp and ocean contrast in the long-term evolution of St clouds. This may suggest that the formation of Sc and St clouds over land relies more on short-term or seasonal-scale weather processes rather than on stable large-scale background evolution. Due to their high sensitivity to boundary layer structure and variations in relative humidity, the stronger seasonal variability and topographic disturbances over land may suppress the emergence of long-term trend signals [57]. Cu over land continues to display a strong trend-dominated structure (Figure 3(b2–i2)), with the residual trend component explaining 58.14% of the variance, comparable to the 56.51% over ocean. Low-frequency components (IMF4–IMF7) together contribute an additional 16%, while high-frequency components (IMF1–IMF3) contribute less than 26%. These findings reinforce the conclusion that Cu variability over both land and ocean is primarily governed by long-term trend and decadal climate forcing, reflecting a dominant sensitivity to changes in the large-scale climatic background.

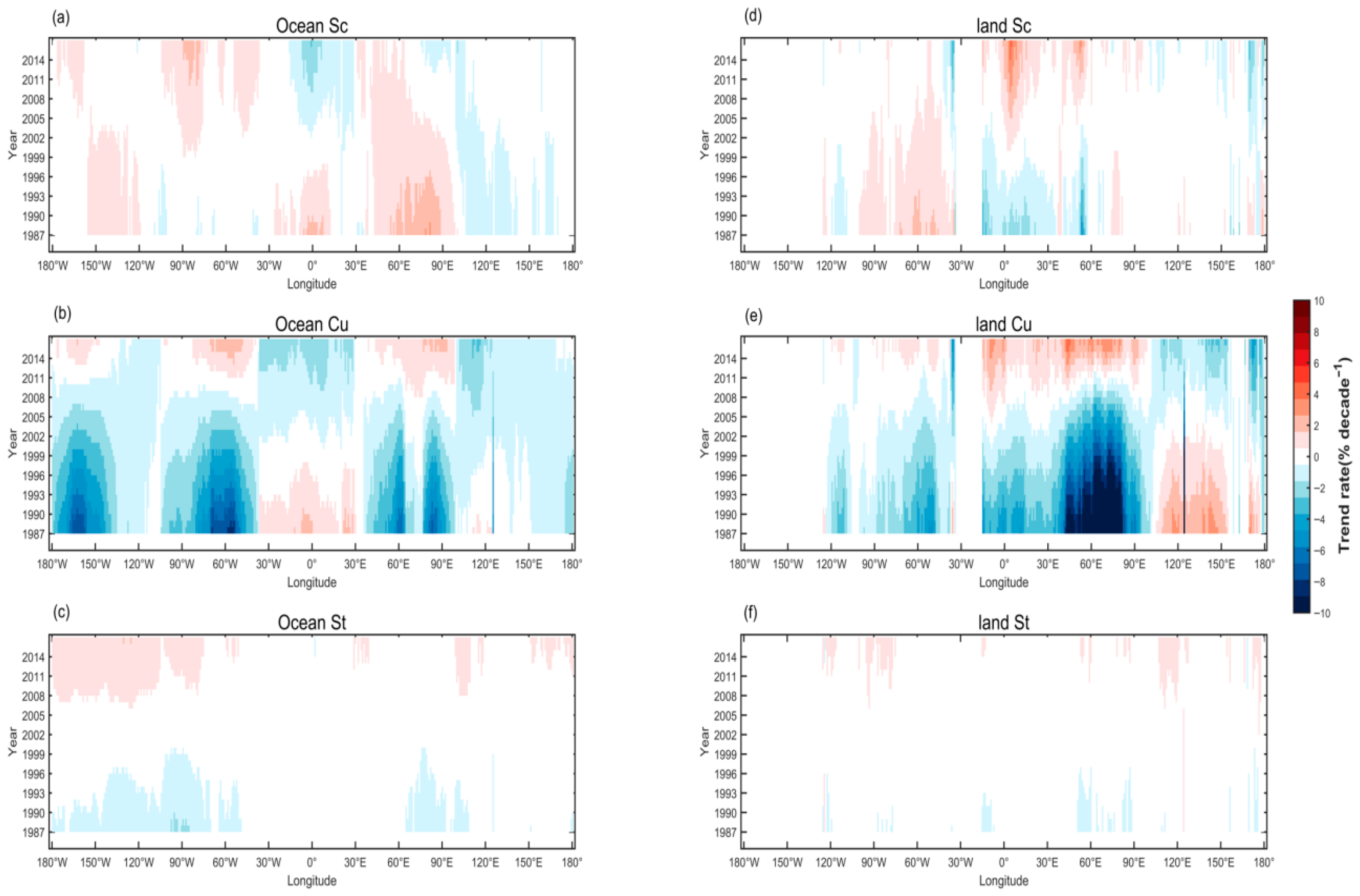

3.2. Temporal and Spatial Evolution of Long-Term Nonlinear Trend of LCA

Observational studies have provided clear evidence of positive feedback associated with low clouds under global warming [27]. However, previous research has also shown that different types of low clouds respond differently to temperature changes, leading to distinct trend patterns [35]. These findings are consistent with the spatial distributions of trend components over land and ocean derived from our EEMD analysis (Figure 2 and Figure 3). While previous studies have mostly focused on linear trends [21], we calculated the cumulative nonlinear trend of LCA based on the EEMD-derived trend term (see Section 2.3).

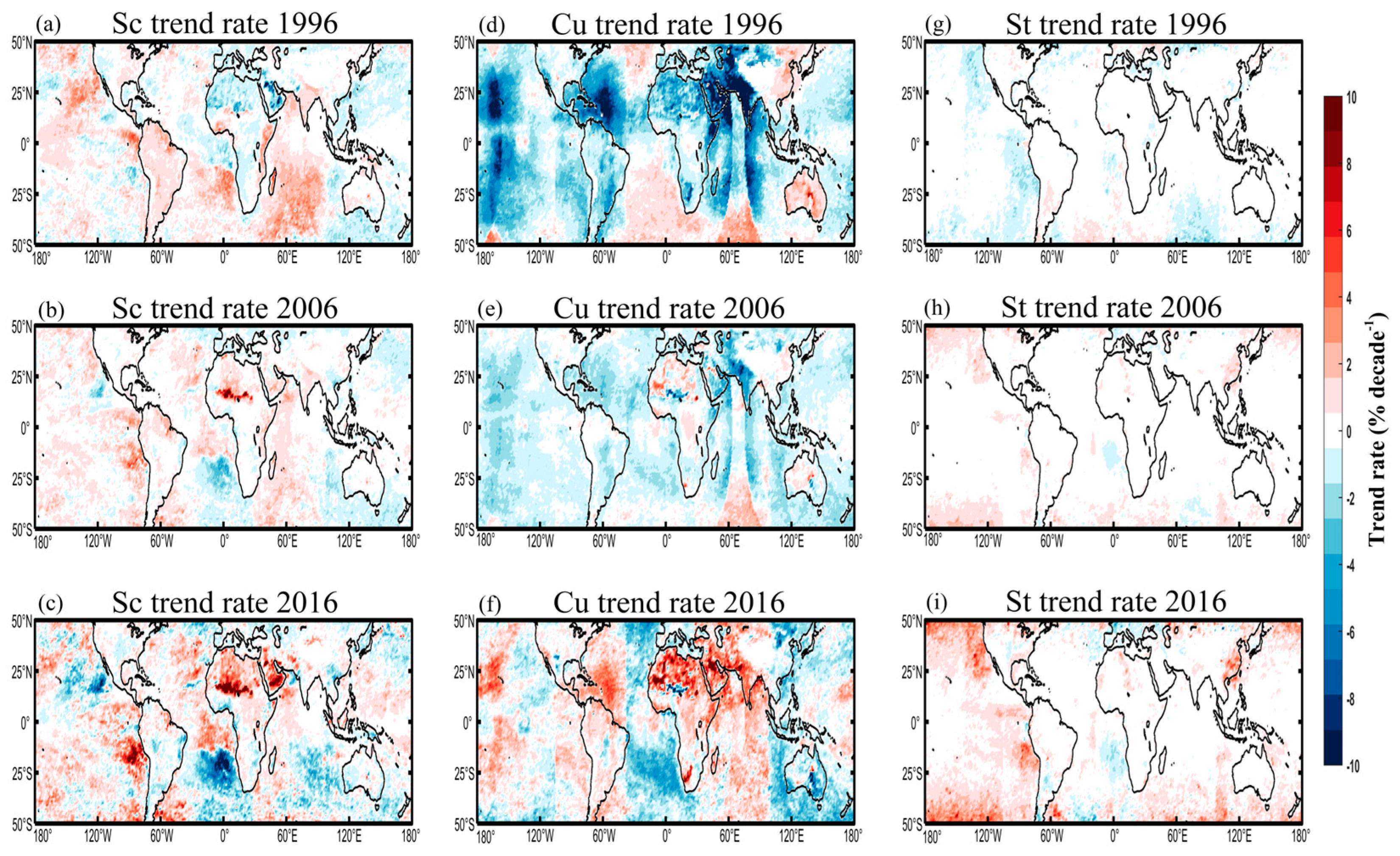

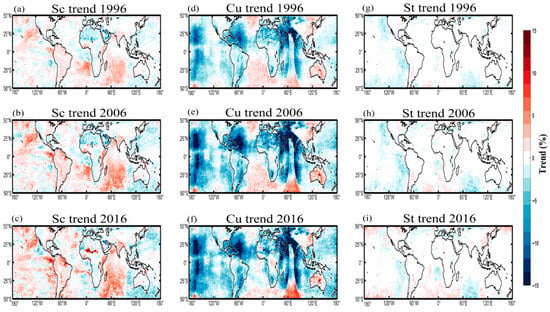

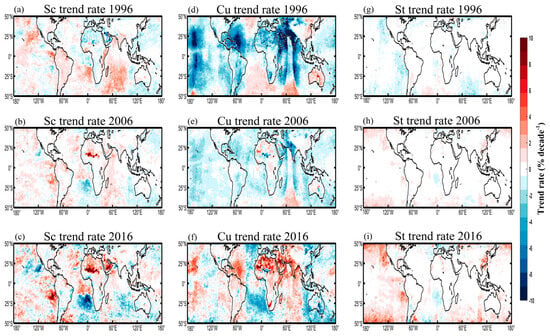

Figure 4 shows the spatial distribution of nonlinear trends for three low cloud types. By 1996, Sc over ocean showed a notable increase across the South Indian Ocean, North Pacific, western Pacific warm pool, and off the South American coast (Figure 4a). In contrast, Cu decreased significantly over the central Pacific, North Atlantic, and western Europe, while increases were found in parts of the South Atlantic and South Indian Ocean (Figure 4d). St showed weak changes overall, with slight increases over the South Atlantic and decreases elsewhere, consistent with their sensitivity to local cooling, inversion intensity, and water supply [16] (Figure 4g). By 2006 (Figure 4b,e,h), the Sc increase extended across key ocean basins, with cumulative trends exceeding 8% in some regions. Cu exhibited a stronger decreasing trend, particularly in the central Pacific, North Atlantic, and western Europe, with reductions over 13%, highlighting a persistent nonlinear decline. Considering that the formation of Cu mainly relies on surface heating and shallow convection processes, in these regions, surface warming without sufficient water vapor or uplift mechanisms may suppress the formation [60]. St began to show modest negative trends in the south Indian Ocean and western Pacific, though overall changes remained limited. In 2016 (Figure 4c,f,i), Sc trends became more widespread and intensified in the tropics and subtropics, especially over the Indian Ocean and eastern tropical Pacific, with increases exceeding 10%, indicating a sustained nonlinear rise. These regions are typically associated with cold SST, strong subsidence, and clear EIS. The observed nonlinear increase may reflect the enhanced stability and radiative cooling under a warming climate, which is conducive to the sustained increase in Sc [16,61]. Cu patterns remained largely unchanged, but areas like the South Atlantic, previously increasing, shifted to decreasing. St showed a contraction of negative zones and expansion of positive trends, signaling a trend reversal. In summary, low cloud types exhibit distinct spatial trends, with Cu decreasing over the North Atlantic and Sc increasing over the Indian Ocean. Previous studies indicate that stronger subsidence, a drier boundary layer, and enhanced thermodynamic stability in the North Atlantic suppress shallow convection, contributing to the persistent decline of Cu in this region [62]. Over the Indian Ocean, sea surface warming accompanied by weaker mid-level warming enhances EIS, and higher low-level humidity creates conditions favorable for the formation and maintenance of stratiform clouds, promoting the development and persistence of Sc [16,32,63].

Figure 4.

Spatial distribution of long-term cumulative nonlinear trend of three different types of low clouds in 1996, 2006, and 2016: (a) stratocumulus in 1996, (b) stratocumulus in 2006, (c) stratocumulus in 2016, (d–f) same as (a–c) but for cumulus, (g–i) same as (a–c) but for stratus.

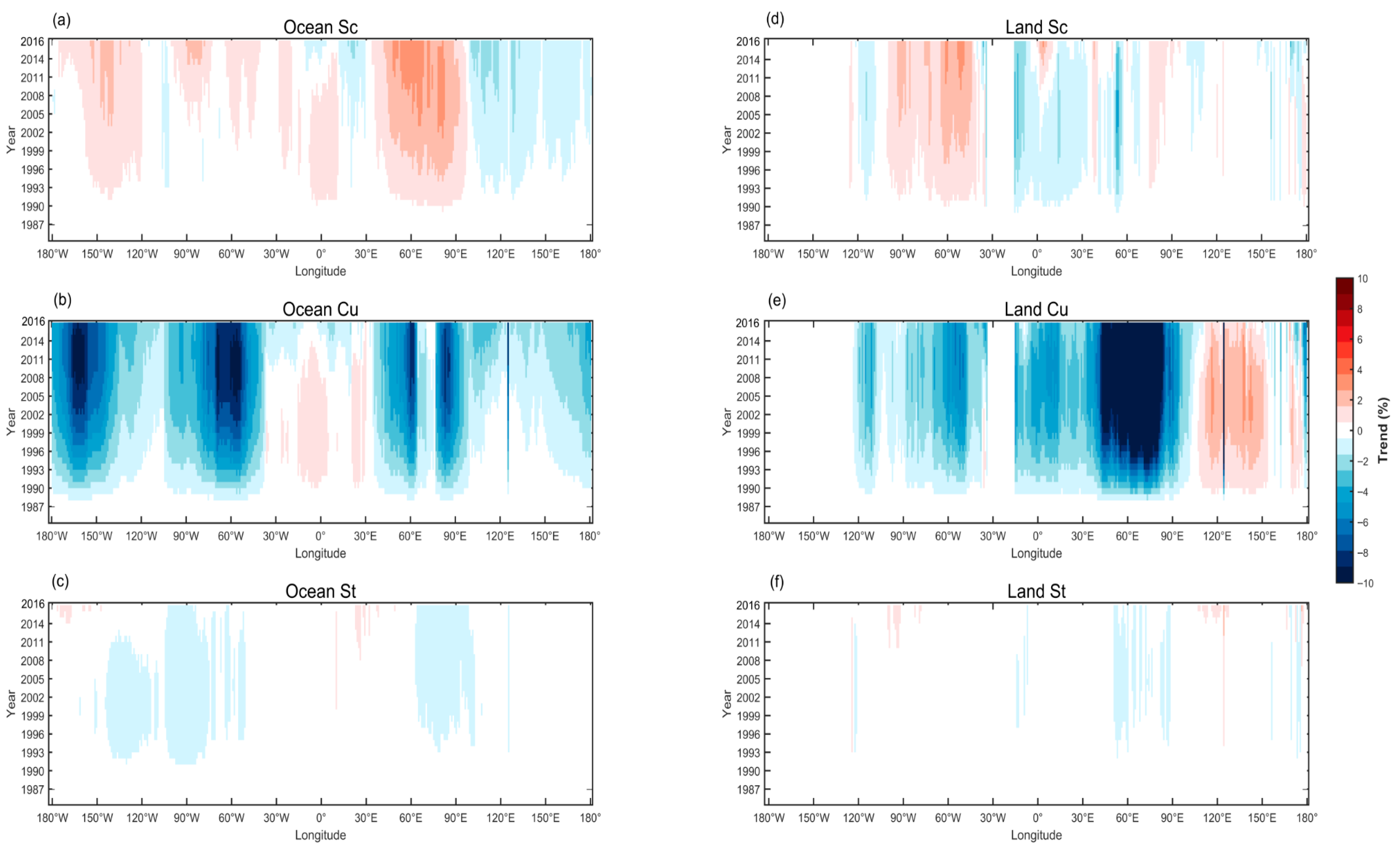

Figure 5 further illustrates the distribution of the nonlinear trends in low cloud changes across longitude and time, enabling a clearer comparison of the magnitude and direction of changes across different longitudes and helping to identify key regions where low clouds consistently increase or decrease over time. Over ocean, Sc exhibited a dominant nonlinear increase, particularly between 45°E and 90°E (Figure 5a), while weak decreases were confined to limited regions like 15°E–30°E and 100°E–180°E. Cu showed broadly consistent nonlinear decreases over 180°W–50°W and 30°E–100°E, with reductions exceeding 10% after 2000 (Figure 5b). St trends were relatively weak, characterized by a “decrease–increase” pattern between 150°W and 50°W and more sustained decreases over 60°E–100°E (Figure 5c). Over land, Sc trends (Figure 5d) were weaker and spatially fragmented, though a notable increase of up to 5% emerged between 90°W and 40°W, subtropical coastal regions such as eastern South America, likely influenced by adjacent marine conditions [54]. Cu (Figure 5e) also showed pronounced nonlinear declines, especially over 40°E–90°E, with reductions exceeding 10% after 1995. However, Cu over Australia and East Asia (110°E–150°E) experienced a nonlinear increase followed by a decline, with peak growth reaching about 6%, possibly related to monsoon dynamics or land-atmosphere interactions [64]. St trends over land (Figure 5f) remained weak and spatially incoherent, lacking clear spatial patterns, which aligns with their reliance on persistent inversion and moist boundary layers, conditions less prevalent over continental interiors [58].

Figure 5.

Longitude and time distribution of long-term cumulative nonlinear trend for different types of low cloud amount over ocean and land: (a) stratocumulus for ocean, (b) cumulus for ocean, (c) stratus for ocean, (d–f) same as (a–c) but for land.

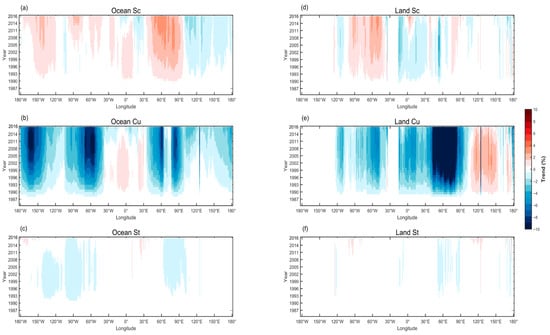

Based on Figure 4 and Figure 5, it is evident that Sc exhibits a nonlinear increasing trend on a global scale, while Cu shows a strong nonlinear decreasing trend. In contrast, St displays relatively weak and spatially inconsistent changes. To gain deeper insight into how these low cloud types evolve over time, we further analyze the evolution rates of their nonlinear trends (see Section 2.3). This approach captures the pace of changes, revealing whether cloud trends are accelerating or decelerating in different regions. Such insights help identify transitional zones and improve our understanding of cloud climate interactions that may not be well discernible from traditional linear trend analyses [50]. As shown in Figure 6a–c, Sc exhibited positive evolution rates in 1996 over the south Indian Ocean, North Pacific, and western Pacific warm pool, indicating a phase of accelerating increases. However, by 2006, the rate of increase had weakened in these regions, suggesting a deceleration in Sc growth. By 2016, several of these areas had transitioned to negative evolution rates, implying a reversal from increasing to decreasing trends. By contrast, Cu showed widespread negative evolution rates in 1996, reflecting a rapid decline. This decline slowed by 2006, with evolution rates moderating to around 2% per decade. By 2016, regions such as the central Pacific, the Americas, Africa, and western Europe began to exhibit positive evolution rates (Figure 6d–f), indicating trend stabilization or slight recovery. St showed modest fluctuations especially over land. Over ocean, St evolved from predominantly negative evolution rates in 1996 to positive in 2006, and continued to rise by 2016, highlighting a “decrease–increase” nonlinear pattern (Figure 6g–i).

Figure 6.

Spatial distribution of the evolution rate of trend for three different types of low clouds in 1996, 2006, and 2016: (a) stratocumulus in 1996, (b) stratocumulus in 2006, (c) stratocumulus in 2016, (d–f) same as (a–c) but for cumulus, (g–i) same as (a–c) but for stratus.

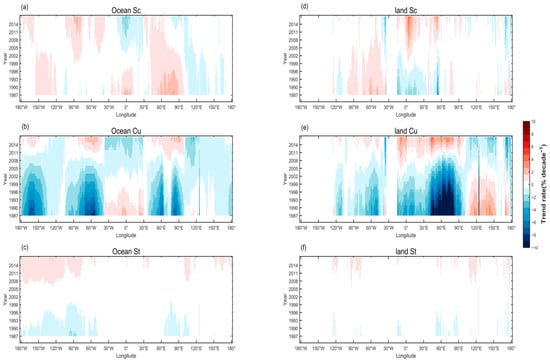

Figure 7 further shows the distribution of evolution rates across longitude and time. Sc over ocean (Figure 7a) maintained consistently positive evolution rates between 45°E and 90°E, indicating a sustained nonlinear increase with a decelerating trend. In Figure 7b, Cu initially showed negative evolution rates in most regions (180°W–50°W and 30°E–100°E), which gradually shifted to positive values, reflecting a slowdown in the decreasing trend. Near the equator (30°W–30°E), the evolution rates first increased and then decreased. St (Figure 7c) had generally weak evolution rates, mostly transitioning from negative to positive over time. In Figure 7d, Sc over land maintained a positive evolution rate in the 90°W–40°W range, indicating persistent growth, albeit with decreasing speed. Cu (Figure 7e) in the key region of 40°E–90°E reached an evolution rate of 10% per decade, showing a shift from rapid decline to stabilization and slight recovery. In contrast, St (Figure 7f) over land exhibited low amplitude and insignificant variability due to the overall weak trend magnitude.

Figure 7.

Longitude and time distribution of the evolution rate of trend for different types of low cloud amount over ocean and land: (a) stratocumulus for ocean, (b) cumulus for ocean, (c) stratus for ocean, (d–f) same as (a–c) but for land.

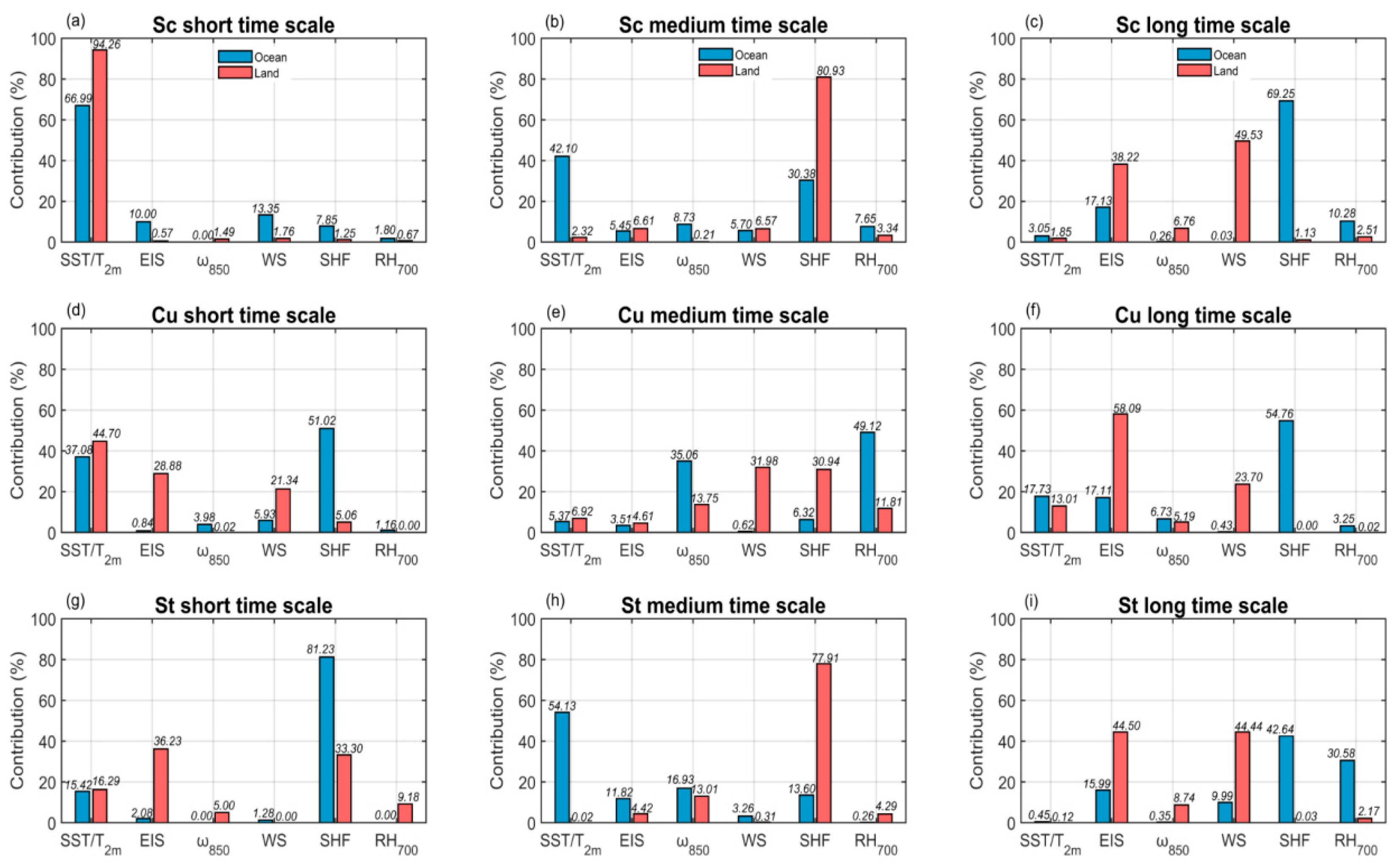

3.3. Dominant CCFs for Multiple Timescales of Low Cloud over Ocean and Land

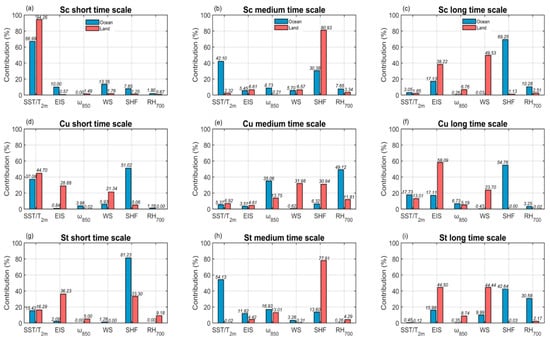

The decompositions of LCA have revealed substantial differences in variability among cloud types and between oceanic and continental regions across both temporal and spatial scales. Importantly, these timescale-dependent differences in cloud behavior primarily arise from variations in the dominant CCFs. Thus, identifying the key meteorological drivers and underlying physical mechanisms at different timescales is essential for improving our understanding of low cloud responses to climate change and long-term warming. Figure 8 summarizes the relative contributions of six selected meteorological factors to LCA across different timescales by using the method described in Section 2.4. For Sc (Figure 8a), short timescale variability over land is overwhelmingly dominated by T2m, with a contribution as high as 94.26%. This highlights the strong sensitivity of Sc to rapid surface heating over land. Over ocean, SST also shows a significant impact, though with a lower contribution, likely due to the ocean’s larger heat capacity, which buffers temperature changes and reduces its influence on Sc variability on short timescale. For Cu, the dominant short-term drivers differ by region. Over land, T2m and EIS contribute 44.70% and 28.88%, respectively, indicating that Cu in convective regions responds strongly to surface warming and local stability changes. Over ocean, SHF emerges as the primary driver, accounting for 51.02% (Figure 8d), underscoring the importance of short-term air–sea heat exchange in modulating Cu development. Our results are consistent with previous parameterization studies. For instance, short-term SST perturbations have been shown to increase Sc coverage by approximately 20%, while SHF and inversion-related processes can enhance Cu coverage by 15–20%, with relatively limited influence on Sc [65]. St exhibits more distinct contrasts between land and ocean. Over ocean, SHF contributes up to 81.23%, while over land, both EIS (36.23%) and SHF (33.30%) play significant roles (Figure 8g). This reflects the strong sensitivity of St to thermal instability. Over land, where surface conditions exhibit greater variability, St formation becomes more reliant on changes in the vertical thermodynamic structure of the lower atmosphere.

Figure 8.

Relative contribution rates of six key meteorological factors to low cloud amount at different timescales: (a) stratocumulus for short timescale, (b) stratocumulus for medium timescale, (c) stratocumulus for long timescale, (d–f) same as (a–c) but for cumulus, (g–i) same as (a–c) but for stratus.

At the medium timescale, differences in low cloud responses are closely related to air–sea coupling associated with ENSO. As shown in Figure 8b,h, Sc and St exhibit similar controlling factors over both land and ocean. Over ocean, both Sc and St are primarily influenced by SST, with contributions of 42.1% and 54.13%, respectively. These results underscore the dominant role of SST as a regulator of marine low clouds at the interannual scale, consistent with previous studies showing that tropical Pacific SST variations are a key regulator of low cloud coverage and radiative feedback [16]. Over land, SHF becomes the dominant factor, contributing 80.93% of the variance for Sc and 77.91% for St. This result extends the focus of previous research, which mainly focused on marine SST by emphasizing the critical influence of land surface processes in shaping low cloud variability [66]. For Cu, the dominant factors over ocean are ω850 and RH700, contributing 35.06% and 49.12%, respectively. This reflects the sensitivity of convective low clouds to ENSO-induced influences on large-scale circulation and lower-to-mid-level moisture transport [67]. This result aligns with the classical interpretations of ENSO impacts on Walker and Hadley circulations, and their modulation of convective cloud distributions [68]. In contrast, Cu over land is mainly affected by WS (31.98%) and SHF (30.94%), suggesting that local turbulence and energy exchange at the surface play dominant roles in shaping convective cloud development over continents (Figure 8e).

At the long timescale, the dominant controlling mechanisms shift markedly toward large-scale background conditions (Figure 8c,f,i). Over land, low cloud development becomes increasingly influenced by EIS and WS. Notably, the response of Sc and Cu to EIS reaches 38.22% and 58.09%, respectively, highlighting the growing importance of large-scale circulation and atmospheric stability in shaping low cloud structures under decadal climate variability. This suggests that at the long timescale, persistent changes in the thermodynamic profile become more influential than transient surface conditions in regulating low cloud coverage. Over ocean, all three cloud types remain predominantly controlled by SHF. This continued dominance suggests a potential link to the role of air–sea heat exchange as a cumulative process that integrates and moderates short-term disturbances, storing and gradually releasing energy over extended periods. Such sustained thermodynamic forcing is consistent with the mechanism proposed by a persistent driver of low cloud variations in the context of long-term climate change [32].

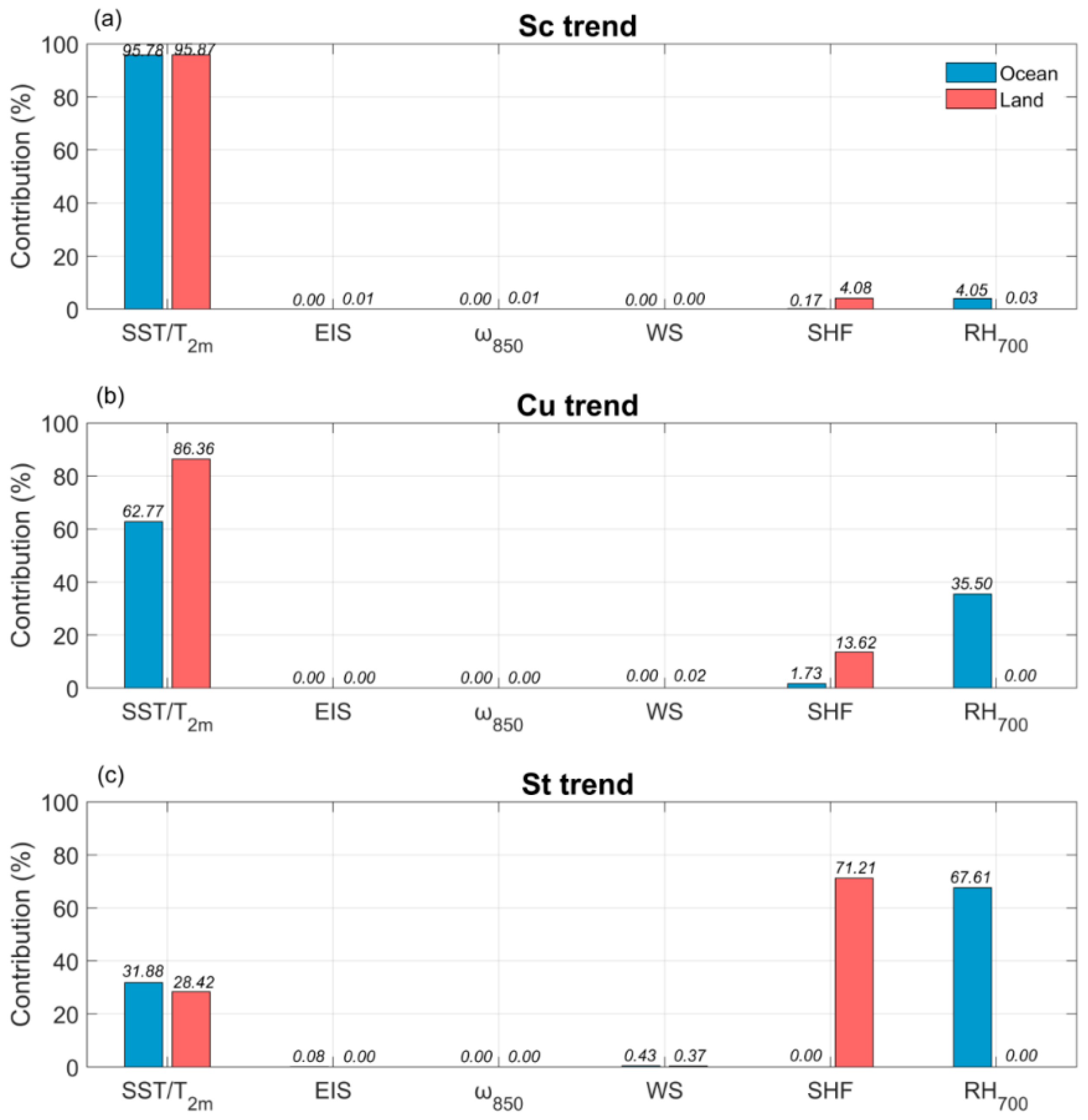

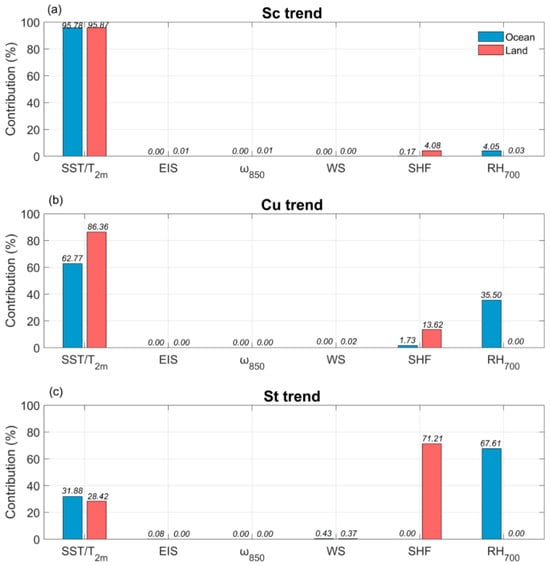

We further quantified the contributions of various CCFs to the nonlinear trend components of low clouds, isolating long-term changes potentially associated with anthropogenic forcing after removing natural interannual and decadal variability. As shown in Figure 9a, for Sc, temperature-related factors dominate the trend signal over both ocean and land. Over ocean, SST dominates, accounting for more than 95%, while over land, T2m plays an equally dominant role. This strong temperature dependence is consistent with previous findings that Sc is particularly sensitive to sustained SST warming [20]. For Cu over land, T2m also remains the leading factor, contributing 86.36%. Over ocean, both SST (62.77%) and RH700 (35.50%) play major roles (Figure 9b), indicating a potential association with the long-term trend in marine Cu, which is jointly modulated by surface thermal conditions and mid-level moisture availability, both of which influence convection initiation and cloud maintenance. This pattern suggests that sustained changes in mid-tropospheric humidity under long-term warming exert a notable influence on marine Cu evolution. In contrast, the dominant drivers of St trends exhibit more regional variability (Figure 9c). Over land, SHF contributes 71.21%, which is in line with the mechanism suggested by its role in modulating boundary layer stability and supporting the persistence of stratiform clouds. Over ocean, RH700 is the primary contributor (67.61%), pointing to a possible role of mid-tropospheric moisture in maintaining St through radiative cooling and condensation processes. These results show that even after removing internal climate variability (e.g., ENSO), long-term changes in free-tropospheric humidity remain a major driver of St variability. This finding aligns with Sherwood et al. [35], who emphasized the role of free-troposphere humidity in regulating St, and it provides new evidence for the persistent uncertainties in marine stratiform cloud feedback under future warming.

Figure 9.

Relative contribution rates of six key meteorological factors to low cloud amount for the trend term: (a) stratocumulus trend, (b) cumulus trend, (c) stratus trend.

4. Discussion

The application of EEMD provides a new analytical perspective for identifying low cloud variability across multiple temporal scales; however, several limitations should still be noted. Firstly, the extracted IMF modes represent statistical oscillations rather than physically independent processes. Therefore, the results do not imply physical causality and cannot independently reveal the mechanisms driving cloud changes. Thus, combining EEMD with physically based diagnostics or modeling approaches is necessary. Future studies should integrate EEMD with climate simulations or idealized experiments to validate the statistical findings and improve understanding of the physical feedbacks governing low cloud evolution across different timescales. Secondly, this study primarily focuses on the statistical influence of meteorological controlling factors on low cloud variability across multiple timescales, but it does not incorporate aerosol effects. Previous studies have shown that aerosols can significantly affect the formation and evolution of low clouds by altering their microphysical properties [69,70], particularly in polluted regions or areas with substantial changes in anthropogenic emissions. Therefore, excluding aerosols may lead to an incomplete interpretation of the mechanisms driving long-term low cloud changes. Future work will integrate long-term aerosol reanalysis datasets or model simulations to further distinguish the relative contributions of meteorological factors and aerosols to low cloud variability, explore aerosol–low cloud interactions and their scale dependence, reduce uncertainties in cloud feedbacks, and improve aerosol–cloud parameterizations in climate models. Lastly, due to limited sensor detectability in regions with extensive high cloud coverage or complex multilayer structures, the ISCCP-H dataset may partially omit low clouds or misclassify cloud types, potentially leading to an underestimation of LCA and introducing systematic uncertainty into long-term trend analysis. Moreover, this study relies solely on ISCCP-H cloud products without cross-validation using other satellite datasets, which may introduce additional bias into the results. Future work will consider incorporating multi-source observations to evaluate consistency and further strengthen the reliability of the conclusions.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we used ISCCP-H data to analyze the spatial distribution of three types of low clouds over both global ocean and land from 1987 to 2016. We found that the Sc had the highest coverage in the ocean, mainly distributed in the subtropical eastern basin of the cold upwelling zone. Cu is widely distributed in tropical and subtropical trade wind zones, while St is limited to mid to high latitudes affected by weather systems. The LCA on land is relatively low, with Cu being the most common, Sc mostly distributed along narrow coastal areas, and St mainly appearing in high-latitude inversion zones.

By applying the EEMD method, we effectively separated the LCA sequence into components across multiple timescales, including annual, interannual, decadal, and long-term trends. This decomposition provides a foundation for examining both the low cloud variability and controlling mechanisms on different timescales. Our results reveal that Sc and St over ocean mainly exhibit high-frequency annual cycles, whereas Cu contains a greater proportion of low-frequency and trend components, suggesting a stronger response to long-term climate background changes. Over land, Sc and St also maintain strong high-frequency fluctuations; however, Cu shows a weak annual cycle and stronger trend contribution, indicating the influence from land surface processes in shaping its long-term behavior. These differences across cloud types illustrate the importance of separating timescales when interpreting low cloud responses, as processes governing short-term variability can be substantially different from those controlling long-term changes. The multi-timescale signal separation therefore enhances our ability to attribute low cloud variations to their dominant physical drivers.

The global trend analysis over the past 30 years reveals that Sc exhibits a significant nonlinear increasing trend in regions such as the Indian Ocean and tropical Pacific, driven by strengthened EIS associated with warmer sea surface temperatures and enhanced lower-tropospheric humidity, although the rate of increase has recently slowed down or even reversed. Cu has experienced a sustained decline in the Central Pacific, North Atlantic, and other regions, largely due to stronger subsidence and enhanced thermodynamic stability that suppresses shallow convection. Although the decrease is decelerating or slightly rebounding. In contrast, St displays an overall weak global trend, but features a regional “decrease increase” pattern, reflecting its localized sensitivity to surface cooling, inversion strength, and water vapor conditions. EEMD provides insights into trend behavior that go beyond traditional linear trend analysis, offering a new perspective for understanding the dynamic evolution of low cloud variability.

We conducted a quantitative assessment of six large-scale CCFs across multiple timescales and found distinct mechanisms governing low cloud variability. For short timescales, Sc and Cu over land are primarily controlled by strong near-surface heating, whereas over ocean, SST and SHF are the dominant influences. On medium timescales, oceanic Sc and St are strongly modulated by SST anomalies associated with ENSO, while their land counterparts respond more to SHF. Cu is particularly sensitive to ω850 and RH700, indicating a strong dependence on circulation and moisture transport. For long timescales, SHF dominates the evolution of all three low cloud types over ocean, while shifts in Sc and Cu over land are primarily controlled by EIS and WS. St shows a significant dependence on mid-level humidity. The trend-focused component of our analysis further highlights that Sc and Cu are particularly responsive to temperature-related factors across both land and ocean, whereas St trends are more affected by humidity transport and surface heating. These findings provide a comprehensive characterization of the temporal behavior and drivers of low clouds and underscore the importance of differentiating cloud type, region, and timescale when assessing cloud–climate interactions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.G. and Y.L.; methodology, Y.L.; software, Y.L.; validation, Y.H. and Z.X.; formal analysis, Y.L.; investigation, Y.L.; resources, Y.L.; data curation, Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L.; writing—review and editing, J.D., Z.X. and Q.M.; visualization, Y.L.; supervision, J.G.; project administration, J.G.; funding acquisition, J.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 42275076 and 41875028), and the Excellent Graduate Student “Innovation Star” Project of Gansu Province (grant no. 2025CXZX-076).

Data Availability Statement

The ISCCP-H data set is publicly available at the website (https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/international-satellite-cloud-climatology (accessed on 22 January 2024)). The ERA5 reanalysis data can be found from the ECMWF Datasets center web interface (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/reanalysis-era5-pressure-levels?tab=form (accessed on 24 January 2024)).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fueglistaler, S. Observational Evidence for Two Modes of Coupling Between Sea Surface Temperatures, Tropospheric Temperature Profile, and Shortwave Cloud Radiative Effect in the Tropics. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 9890–9898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, B.; Clement, A.C.; Benedict, J.J.; Zhang, B. Investigating the Impact of Cloud-Radiative Feedbacks on Tropical Precipitation Extremes. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2021, 4, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bony, S.; Stevens, B.; Frierson, D.M.W.; Jakob, C.; Kageyama, M.; Pincus, R.; Shepherd, T.G.; Sherwood, S.C.; Siebesma, A.P.; Sobel, A.H.; et al. Clouds, Circulation and Climate Sensitivity. Nat. Geosci. 2015, 8, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesana, G.; Del Genio, A.D.; Chepfer, H. The Cumulus And Stratocumulus CloudSat-CALIPSO Dataset (CASCCAD). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2019, 11, 1745–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duveiller, G.; Filipponi, F.; Ceglar, A.; Bojanowski, J.; Alkama, R.; Cescatti, A. Revealing the Widespread Potential of Forests to Increase Low Level Cloud Cover. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.; Zhao, C.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Yang, J. Global Characteristics of Cloud Macro-Physical Properties from Active Satellite Remote Sensing. Atmos. Res. 2024, 302, 107316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Quaas, J.; Han, Y. Diurnally Asymmetric Cloud Cover Trends Amplify Greenhouse Warming. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eado5179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mülmenstädt, J.; Salzmann, M.; Kay, J.E.; Zelinka, M.D.; Ma, P.-L.; Nam, C.; Kretzschmar, J.; Hörnig, S.; Quaas, J. An Underestimated Negative Cloud Feedback from Cloud Lifetime Changes. Nat. Clim. Change 2021, 11, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelinka, M.D.; Myers, T.A.; McCoy, D.T.; Po-Chedley, S.; Caldwell, P.M.; Ceppi, P.; Klein, S.A.; Taylor, K.E. Causes of Higher Climate Sensitivity in CMIP6 Models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47, e2019GL085782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fermepin, S.; Bony, S. Influence of Low-Cloud Radiative Effects on Tropical Circulation and Precipitation. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2014, 6, 513–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Xie, S.-P.; Shen, S.S.P.; Liu, J.-W.; Hwang, Y.-T. Low Cloud–SST Feedback over the Subtropical Northeast Pacific and the Remote Effect on ENSO Variability. J. Clim. 2022, 36, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceppi, P.; Myers, T.A.; Nowack, P.; Wall, C.J.; Zelinka, M.D. Implications of a Pervasive Climate Model Bias for Low-Cloud Feedback. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2024, 51, e2024GL110525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konsta, D.; Dufresne, J.-L.; Chepfer, H.; Vial, J.; Koshiro, T.; Kawai, H.; Bodas-Salcedo, A.; Roehrig, R.; Watanabe, M.; Ogura, T. Low-Level Marine Tropical Clouds in Six CMIP6 Models Are Too Few, Too Bright but Also Too Compact and Too Homogeneous. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2021GL097593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X. Spatiotemporal Changes in Sunshine Duration and Cloud Amount as Well as Their Relationship in China during 1954–2005. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2010, 115, D00K06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grise, K.M.; Tselioudis, G. Understanding the Relationship between Cloud Controlling Factors and the ISCCP Weather States. J. Clim. 2024, 37, 5387–5403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, T.A.; Scott, R.C.; Zelinka, M.D.; Klein, S.A.; Norris, J.R.; Caldwell, P.M. Observational Constraints on Low Cloud Feedback Reduce Uncertainty of Climate Sensitivity. Nat. Clim. Change 2021, 11, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Hall, A.; Klein, S.A.; DeAngelis, A.M. Positive Tropical Marine Low-Cloud Cover Feedback Inferred from Cloud-Controlling Factors. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015, 42, 7767–7775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, J.; Cermak, J.; Andersen, H. Building a Cloud in the Southeast Atlantic: Understanding Low-Cloud Controls Based on Satellite Observations with Machine Learning. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 16537–16552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tselioudis, G.; Rossow, W.B.; Jakob, C.; Remillard, J.; Tropf, D.; Zhang, Y. Evaluation of Clouds, Radiation, and Precipitation in CMIP6 Models Using Global Weather States Derived from ISCCP-H Cloud Property Data. J. Clim. 2021, 34, 7311–7324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, T.A.; Zelinka, M.D.; Klein, S.A. Observational Constraints on the Cloud Feedback Pattern Effect. J. Clim. 2023, 36, 6533–6545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ge, J.; Du, J.; Peng, N.; Su, J.; Hu, X.; Zhang, C.; Mu, Q.; Li, Q. Projection of Low Cloud Variation Through Robust Meteorological Linkage and Its Comparison with CMIP6 Models at the SACOL Site. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2024, 129, e2023JD040668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Dessler, A.E.; Zelinka, M.D.; Yang, P.; Wang, T. Cirrus Feedback on Interannual Climate Fluctuations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 9166–9173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Ji, F.; Hu, S.; He, Y. Asymmetric Drying and Wetting Trends in Eastern and Western China. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2024, 41, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Su, H.; Jiang, J.H.; Neelin, J.D.; Wu, L.; Tsushima, Y.; Elsaesser, G. Muted Extratropical Low Cloud Seasonal Cycle Is Closely Linked to Underestimated Climate Sensitivity in Models. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiro, K.A.; Su, H.; Ahmed, F.; Dai, N.; Singer, C.E.; Gentine, P.; Elsaesser, G.S.; Jiang, J.H.; Choi, Y.-S.; David Neelin, J. Model Spread in Tropical Low Cloud Feedback Tied to Overturning Circulation Response to Warming. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, J.; Li, W.; Huang, J.; Mu, Q.; Li, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Su, J.; Xie, Y.; Alam, K.; Zhu, Z.; et al. Dust Accelerates the Life Cycle of High Clouds Unveiled through Strongly-Constrained Meteorology. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2024, 51, e2024GL109998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, D.T.; Eastman, R.; Hartmann, D.L.; Wood, R. The Change in Low Cloud Cover in a Warmed Climate Inferred from AIRS, MODIS, and ERA-Interim. J. Clim. 2017, 30, 3609–3620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, R.C.; Myers, T.A.; Norris, J.R.; Zelinka, M.D.; Klein, S.A.; Sun, M.; Doelling, D.R. Observed Sensitivity of Low-Cloud Radiative Effects to Meteorological Perturbations over the Global Oceans. J. Clim. 2020, 33, 7717–7734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, L.; Brunke, M.A.; Zeng, X. Re-Evaluation of Low Cloud Amount Relationships with Lower-Tropospheric Stability and Estimated Inversion Strength. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2022GL098137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, R.; Bretherton, C.S. On the Relationship between Stratiform Low Cloud Cover and Lower-Tropospheric Stability. J. Clim. 2006, 19, 6425–6432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evan, A.T.; Allen, R.J.; Bennartz, R.; Vimont, D.J. The Modification of Sea Surface Temperature Anomaly Linear Damping Time Scales by Stratocumulus Clouds. J. Clim. 2013, 26, 3619–3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naud, C.M.; Elsaesser, G.S.; Booth, J.F. Dominant Cloud Controlling Factors for Low-Level Cloud Fraction: Subtropical versus Extratropical Oceans. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2023, 50, e2023GL104496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamaakel, O.; Matheou, G. Organization Development in Precipitating Shallow Cumulus Convection: Evolution of Turbulence Characteristics. J. Atmos. Sci. 2022, 79, 2419–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Su, H.; Neelin, J.D. Multi-Objective Observational Constraint of Tropical Atlantic and Pacific Low-Cloud Variability Narrows Uncertainty in Cloud Feedback. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, S.C.; Webb, M.J.; Annan, J.D.; Armour, K.C.; Forster, P.M.; Hargreaves, J.C.; Hegerl, G.; Klein, S.A.; Marvel, K.D.; Rohling, E.J.; et al. An Assessment of Earth’s Climate Sensitivity Using Multiple Lines of Evidence. Rev. Geophys. 2020, 58, e2019RG000678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.A.; Hall, A.; Norris, J.R.; Pincus, R. Low-Cloud Feedbacks from Cloud-Controlling Factors: A Review. In Shallow Clouds, Water Vapor, Circulation, and Climate Sensitivity; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 135–157. [Google Scholar]

- Proistosescu, C.; Donohoe, A.; Armour, K.C.; Roe, G.H.; Stuecker, M.F.; Bitz, C.M. Radiative Feedbacks from Stochastic Variability in Surface Temperature and Radiative Imbalance. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2018, 45, 5082–5094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Szoeke, S.P.; Verlinden, K.L.; Yuter, S.E.; Mechem, D.B. The Time Scales of Variability of Marine Low Clouds. J. Clim. 2016, 29, 6463–6481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Hall, A.; Qu, X. On the Relationship between Low Cloud Variability and Lower Tropospheric Stability in the Southeast Pacific. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2011, 11, 9053–9065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, T.A.; Norris, J.R. Observational Evidence That Enhanced Subsidence Reduces Subtropical Marine Boundary Layer Cloudiness. J. Clim. 2013, 26, 7507–7524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.H.; Knapp, K.R.; Inamdar, A.; Hankins, W.; Rossow, W.B. The International Satellite Cloud Climatology Project H-Series Climate Data Record Product. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2018, 10, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evan, A.T.; Heidinger, A.K.; Vimont, D.J. Arguments against a Physical Long-Term Trend in Global ISCCP Cloud Amounts. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007, 34, L04701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossow, W.B.; Knapp, K.R.; Young, A.H. International Satellite Cloud Climatology Project: Extending the Record. J. Clim. 2022, 35, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Letu, H.; Shang, H.; Shi, J. Cloud Cover over the Tibetan Plateau and Eastern China: A Comparison of ERA5 and ERA-Interim with Satellite Observations. Clim. Dyn. 2020, 54, 2941–2957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; You, Q.; Ma, Y.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Niu, M.; Zhang, Y. Changes in Cloud Amount over the Tibetan Plateau and Impacts of Large-Scale Circulation. Atmos. Res. 2021, 249, 105332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Huang, N.E. Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition: A Noise-Assisted Data Analysis Method. Adv. Adapt. Data Anal. 2009, 01, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N.E.; Wu, Z. A Review on Hilbert-Huang Transform: Method and Its Applications to Geophysical Studies. Rev. Geophys. 2008, 46, RG2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, F.; Wu, Z.; Huang, J.; Chassignet, E.P. Evolution of Land Surface Air Temperature Trend. Nat. Clim. Change 2014, 4, 462–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Tang, G.; Yuan, Y.; Guo, H.; Xu, Z.; Jiang, G.; Chen, X. Unraveling the Relative Impacts of Climate Change and Human Activities on Grassland Productivity in Central Asia over Last Three Decades. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 743, 140649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Han, X.; Ji, F.; Xu, Z.; Guan, X.; Huang, J. Observed Evolution of Global Climate Change Hotspots. Environ. Res. Lett. 2025, 20, 074031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Santoso, A.; Collins, M.; Dewitte, B.; Karamperidou, C.; Kug, J.-S.; Lengaigne, M.; McPhaden, M.J.; Stuecker, M.F.; Taschetto, A.S.; et al. Changing El Niño–Southern Oscillation in a Warming Climate. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 628–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrence, C.; Webster, P.J. Interdecadal Changes in the ENSO–Monsoon System. J. Clim. 1999, 12, 2679–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, B.; Li, J.; Wang, G.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Huang, J. Evaluation of the CMIP6 Marine Subtropical Stratocumulus Cloud Albedo and Its Controlling Factors. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21, 9809–9828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, C.; Sourdeval, O.; Mülmenstädt, J.; Quaas, J.; Crewell, S. Cloud Base Height Retrieval from Multi-Angle Satellite Data. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2019, 12, 1841–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhlbauer, A.; McCoy, I.L.; Wood, R. Climatology of Stratocumulus Cloud Morphologies: Microphysical Properties and Radiative Effects. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2014, 14, 6695–6716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassen, K.; Wang, Z.; Liu, D. Global Distribution of Cirrus Clouds from CloudSat/Cloud-Aerosol Lidar and Infrared Pathfinder Satellite Observations (CALIPSO) Measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2008, 113, D00A12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M.D.; Platnick, S.; Menzel, W.P.; Ackerman, S.A.; Hubanks, P.A. Spatial and Temporal Distribution of Clouds Observed by MODIS Onboard the Terra and Aqua Satellites. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2013, 51, 3826–3852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, R.T.; Stephens, G.L. Retrieval of Stratus Cloud Microphysical Parameters Using Millimeter-Wave Radar and Visible Optical Depth in Preparation for CloudSat: 1. Algorithm Formulation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2001, 106, 28233–28242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valjarević, A.; Popovici, C.; Djekić, T.; Morar, C.; Filipović, D.; Lukić, T. Long-Term Monitoring of High Optical Imagery of the Stratospheric Clouds and Their Properties New Approaches and Conclusions. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2022, 25, 1037–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, B. On the Growth of Layers of Nonprecipitating Cumulus Convection. J. Atmos. Sci. 2007, 64, 2916–2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, T.A.; Norris, J.R. Reducing the Uncertainty in Subtropical Cloud Feedback. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 2144–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuijens, L.; Medeiros, B.; Sandu, I.; Ahlgrimm, M. Observed and Modeled Patterns of Covariability between Low-Level Cloudiness and the Structure of the Trade-Wind Layer. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2015, 7, 1741–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, R. Stratocumulus Clouds. Mon. Weather Rev. 2012, 140, 2373–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neggers, R.A.J.; Siebesma, A.P.; Jonker, H.J.J. A Multiparcel Model for Shallow Cumulus Convection. J. Atmos. Sci. 2002, 59, 1655–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.-M.; Cheng, A.; Zhang, M. Cloud-Resolving Simulation of Low-Cloud Feedback to an Increase in Sea Surface Temperature. J. Atmos. Sci. 2010, 67, 730–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, R.; Gu, Q.; Chen, X.; Jia, X.; Zhang, Y. Influences of Tropical Pacific and North Atlantic SST Anomalies on Summer Drought over Asia. Clim. Dyn. 2023, 61, 5827–5844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, H.; Wang, B. Patterns and Frequency of Projected Future Tropical Cyclone Genesis Are Governed by Dynamic Effects. Commun. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radley, C.; Fueglistaler, S.; Donner, L. Cloud and Radiative Balance Changes in Response to ENSO in Observations and Models. J. Clim. 2014, 27, 3100–3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, M.; Rosenfeld, D.; Zhou, C.; Liu, J.; Liang, Y.; Huang, K.-E.; Wang, Q.; Bai, H.; et al. Improving Prediction of Marine Low Clouds Using Cloud Droplet Number Concentration in a Convolutional Neural Network. J. Geophys. Res. Mach. Learn. Comput. 2024, 1, e2024JH000355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, M.; Rosenfeld, D.; Cao, Y.; Yuan, T. Cloud Susceptibility to Aerosols: Comparing Cloud-Appearance Versus Cloud-Controlling Factors Regimes. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2024, 129, e2024JD041216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).