Highlights

What are the main findings?

- A minor 1.37% proportion loss in high-ecological value of grassland, woodland, wetland, and water body caused a large ESV loss of CNY 116.141 billion.

- The negative contribution of precipitation and human activities to ESV is gradually weakening, while the promoting effect from both is strengthening.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- Small losses of high-ecological-value land leading to large ESV declines highlight the priority of conserving these land types in policy-making; quantifying ESV losses also supports ecological compensation standards in fragile regions.

- As precipitation and human activities shift to exert positive impacts on ESV, this change supports the transition of regional environmental governance from passive restoration to active enhancement.

Abstract

The spatiotemporal evolution of ecosystem services has a profound influence on the fragile eco-environment in Inner Mongolia and the arid/semi-arid and the ecological barrier regions of Northern China; in particular, the small-scale and high-value land variables may lead to large eco-environment effects through altering the ecosystem services, which is still unclear in this vulnerable area. The differential driving mechanism of both human activities and natural factors on ecosystem services also needs to be revealed. To solve this scientific issue, the synergistic methodology of spatial analysis technology, the improved ecosystem service assessment method, flow gain/loss model, global/local Moran’s I approach, and the Geographically and Temporally Weighted Regression (GTWR) model were applied. Our main results are as follows: remote sensing monitoring showed that the land changes featured a persistent expansion of cropland and built-up areas, with a decline in grassland and wetland, along the east–west gradient from forests, grasslands, and unused-lands, to become the dominant cover type. According to our improved model, the ecosystem services considering the internal structure of build-up lands were first investigated in this ecologically fragile area of China, and the evaluated ecosystem service value (ESV) reduced from CNY 5515.316 billion to CNY 5425.188 billion, with an average annual decrease of CNY 3.004 billion from 1990 to 2020. Another finding was that the small-scale land variables with large ecological service impacts were quantified; namely, the proportion of grassland, woodland, wetland, and water body decreased from 62.71% to 61.34%, with only a relatively minor fluctuation of −1.37%, but this decline resulted in a large ESV loss of CNY 116.141 billion from 1990 to 2020. From the driving perspective, the temperature, digital elevation model (DEM), and slope exhibited negative effects on ESV changes, whereas a positive association was analyzed in terms of the precipitation and human footprint during the studied period. This study provides important support for optimizing land resource allocation, guiding the development of agriculture and animal husbandry, and protecting the ecological environment in arid/semi-arid and ecological barrier regions.

1. Introduction

The ESV is essential for maintaining ecosystem stability, human well-being, and sustainable socio-economic development [1]. Early frameworks by Daily and Costanza proposed monetized models for ESV quantification [2,3,4]. Subsequently, in China, ESV assessments commonly use the function value approach and equivalent factor method [5], with the latter being more prevalent due to its simplicity and accessibility [6]. Here, Xie et al. developed a widely adopted equivalent factor table for the Chinese ESV, though its initial version misclassified built-up land as desert, potentially underestimating the ESV [5]. Under the background of rapid urbanization and corresponding policies like urban renewal and rural revitalization, integrating blue–green infrastructure into urban and town planning has gained prominence. Green space changes within built-up areas significantly influence ecological services, including microclimate regulation, air–water purification, and biodiversity conservation. The diversity of green spaces, such as forests and grasslands, also supports urban–rural wildlife habitats and enhances ecosystem resilience. Therefore, the internal land change and ecological environment issues of build-up land have become a popular academic topic. However, classifying built-up areas as deserts in ESV assessments may overlook their internal structural components, leading to underestimation in the equivalent factor model. The expansion of the impervious surface area (e.g., roofs, roads, squares) further alters the land cover composition, highlighting the need for improved ESV models [7,8]. This study addresses this issue by integrating built-up land’s internal structural components into ESV assessments using remote sensing images and spatial analysis techniques. By incorporating these elements, the model aims to provide a more accurate valuation of ecosystem services, supporting decision-making in urban–rural planning and ecological conservation.

The quantification of surface ecosystem services predominantly relies on land use as a key indicator, since land cover change acts as an essential medium for ESV assessment [9,10]. For land use products, due to the limitations in early remote sensing satellite imaging systems, land use data with coarser resolutions were more widely utilized, such as the 5 km resolution Global Land Surface Satellite–Annual Dynamics of Global Land Cover (GLASS-GLC), the 1 km resolution Moderate-resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) product, and the 300 m resolution European Space Agency Climate Change Initiative Land Cover (ESA CCI-LC) dataset [11]. Subsequently, advancements in remote sensing big data and cloud computing platforms have facilitated high-precision land mapping such as global land 30, offering a critical pathway for accurately assessing the effect of the land system on the environmental system [12]. Although the land system is characterized by diversification, the land use dataset from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) institution demonstrates high precision in national, regional, and local ecosystem assessments, owing to its continuity across multiple time periods and its comprehensive land classification system [13,14,15]. Consequently, this dataset was utilized in the present study. A review of the existing literature indicates that land-use change-based ecosystem service research is a well-established field with extensive studies across global, regional, and local scales. In the humid coastal regions, most of the literature has predominantly examined land area dynamics’ impacts on ecosystem services’ trends and patterns [16,17,18,19]; however, a gap remains in analyzing the land gain/loss effects [20]. Meanwhile, as widely recognized, forests, grasslands, wetlands, and water bodies exhibit higher ecosystem service values than croplands, built-up areas, or deserts. This valuation disparity is particularly critical in arid/semi-arid regions with drought/desertification backgrounds, where intense land-use transitions between these categories demand urgent attention [21]. Consequently, monitoring land use change and its ecosystem impacts remains a hot topic from a land gain/loss effect perspective. Arid/semi-arid regions exhibit heightened ecological sensitivity, and minor land changes in high-value ecosystems may obviously change the values of the entire regional ecosystem. Compared to previous studies, such research should be achieved in arid/semi-arid regions of China, to conduct comprehensive studies of the land-environment systems in the future.

For simulation of the driving factors of ecosystem services, this issue continues to be a focus considering the substantial influence of ecosystem services on both the living environment and human well-being [22,23,24]. This analysis typically employs model-based approaches, with Ordinary Least Squares Regression (OLS), Geographic Detector (GD), Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR), and GTWR being widely utilized in existing literature [25,26,27]. Among which, the OLS model, a conventional regression technique, effectively analyzes linear relationships between ESV and drivers but cannot capture spatial heterogeneity. While GD and GWR models can address spatial variations, they overlook temporal dynamics. After recognizing that spatial drivers often exhibit temporal patterns [25,28,29], the GTWR model was developed to integrate both dimensions, enabling comprehensive spatiotemporal analysis of ESV changes [30]. By leveraging the distinct advantages of each model, namely, OLS for linear relationships, GD and GWR for spatial analysis, and GTWR for spatiotemporal evaluation, the researchers can adopt tailored approaches to analyze complex driver–ESV relationships. This multi-model way enhances the understanding of ecosystem service dynamics, as well as the corresponding spatiotemporal heterogeneity driven by different factors.

Located in arid and semi-arid regions, Inner Mongolia faces precipitation scarcity with pronounced spatial and temporal variability. The prevailing high-intensity wind accelerates the soil desertification processes, while the winter cold surges and summer thermal extremes synergistically amplify evaporative water loss. Vegetation restoration in this region always requires protracted periods of 5–10 years, and the intricate topography exhibits the heightened vulnerability to erosional degradation. Meanwhile, acute urban land expansion, grassland’s degradation/restoration, and other land changes in this region evidently caused a series of eco-environmental issues. Considering the importance that examining the effects of land use alterations on ESV and the related drivers in environmentally sensitive areas, this study focuses on the Inner Mongolia with three primary objectives: (1) to track the spatiotemporal patterns of land use changes using the remote sensing images to provide the information on main land types, (2) to explore the resulting variations in ESV from different land changes, with a key focus here is to examine ESV gains and losses associated with the conversion between high-ecological-value green spaces and low-ecological-value land categories (i.e., cropland, deserts, and built-up land), and (3) to delineate the distinct influences of natural environments and human activities on ESV across both temporal and spatial dimensions. Theoretically, this study contributes to the literature by integrating high-resolution remote sensing data with field investigations to refine the classification of built-up land within ecosystem service models, thereby addressing the common issue of ESV underestimation in ecologically fragile/semi-arid regions. Practically, the findings are expected to provide a robust scientific basis for optimizing land resource allocation, protecting vulnerable grassland ecosystems, and guiding sustainable agricultural and pastoral planning, while also offering a reference for relevant decision-making within environmental protection departments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

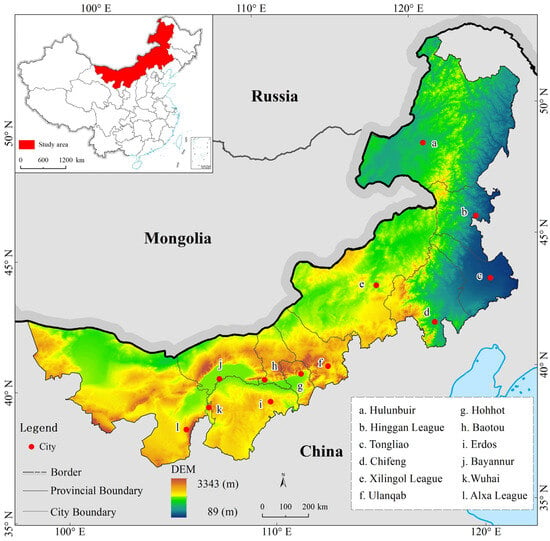

Inner Mongolia plays the role of an ecological barrier functional region in Northern China (Figure 1). The total area of Inner Mongolia is 1.14 million km2, comprising 12 prefecture-level administrative divisions, namely, nine cities (i.e., Hohhot, Baotou, Wuhai, Chifeng, Tongliao, Ordos, Hulunbuir, Bayannur, Ulanqab) and three leagues (i.e., Hinggan, Xilingol, Alxa). The region experiences a mid-latitude continental monsoon climate, characterized by abrupt spring temperature rises, brief and hot summers, sharp autumn temperature drops, and long and cold winters. Monsoon influence creates distinct longitudinal climatic variations, including humid, semi-humid, semi-arid, and arid zones, underscoring the area’s ecological fragility.

Figure 1.

Location, administrative division, and elevation distribution map of the research area.

2.2. Data Sources

The data collection comprised four categories: natural environment, human activity, statistical information, and other data (Table 1). The natural environment data encompassed the DEM, temperature, precipitation, normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), the net primary productivity (NPP), the fractional vegetation cover (FVC), and soil wind erosion. The human activity data included China Land Use/Cover Dataset (CLUD), impervious surface, and the human footprint. The statistical information contained crop planting area and crop net profit. Other data included urban center points. Among them, the DEM, soil wind erosion, the CLUD [13,14,15], impervious surface [8], and urban center points were sourced from CAS. Among which, the CLUD was selected as the primary land use data source. This dataset was chosen after reviewing the relevant literature and consulting research institutions, owing to its extensive temporal coverage, comprehensive land classification system (i.e., 25 land categories), and high-precision vector format, which offered superior accuracy compared to raster data. Given its advantages in long time series, detailed land classification, and vector-based precision, the CLUD was employed for this study. Specifically, the initial time point of land 1990 and the available time point of 2020 were utilized, with a 10-year interval between time steps to ensure temporal consistency and data monitoring reliability. National Tibetan Plateau Science Data Center provided the temperature and precipitation data used in this study. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration of the United States provided NDVI and NPP. The human footprint was derived from the Urban Environment Monitoring and Modeling (UEMM) team [31]. Statistical data were derived from the National Compilation of Agricultural Product Cost and Revenue Data and Inner Mongolia Statistical Yearbook. The study implemented a series of preprocessing steps on the original data, including radiometric correction, geometric correction, projection transformation, scale conversion, boundary extraction, and attribute integration. Subsequently, all raster datasets were resampled to a standardized spatial resolution of 30 m to guarantee spatial homogeneity throughout the analytical process. Meanwhile, the OLS model was applied to calculate the variance factor for the nine selected indicators, including the DEM, slope, temperature, precipitation, soil wind erosion, FVC, NDVI, NPP, and human footprint. The statistical evaluation identified five indicators (i.e., DEM, slope, temperature, precipitation, and human footprint) as suitable for subsequent modeling, exhibiting variance inflation factor (VIF) values below the critical threshold (i.e., DEM: 1.491; slope: 1.973; temperature: 2.546; precipitation: 2.728; human footprint: 1.502).

Table 1.

List of data names, years, and corresponding sources.

2.3. Methods

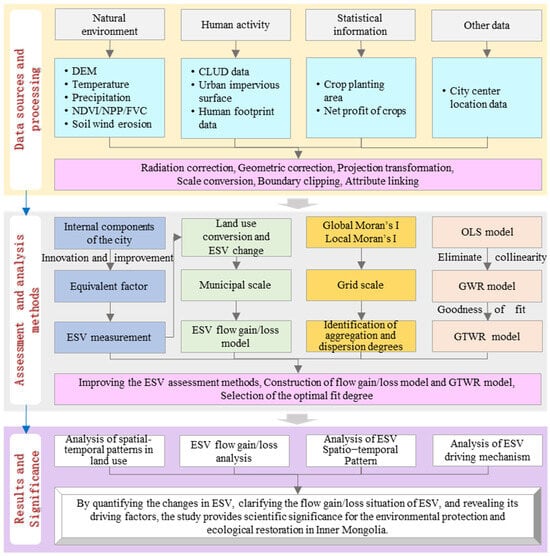

The equivalent factor approach for ESV assessment was first enhanced. Then, utilizing the land use transfer matrix, a flow gain/loss model was developed to quantify ESV variations. Spatial patterns of agglomeration and dispersion within Inner Mongolia were analyzed using global/local Moran’s I statistics. Subsequently, the models of OLS, GWR, and GTWR were conducted to simulate the optimal goodness-of-fit and elucidate the contribution levels of the influencing factors to the ESV. The main research framework is provided in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The framework of this study.

2.3.1. Assessment Methods for ESV

The equivalent factor model, while having been extensively utilized for ecosystem service valuation throughout China [32], was found to require a fundamental equivalent factor correction for the built-up land ecosystem (i.e., urban–rural settlements and standalone industrial/mining lands), because its corresponding ecosystem factor parameter was set as desert. Notably, greening spaces within the built-up land ecosystem played a critical ecological role in supporting livable cities, ecological urban development, and rural tourism initiatives [33]. Therefore, the equivalent factor correction was implemented through methodological innovation to rectify the systematic underestimation of built-up land ecosystem service values. A detailed process of correcting equivalent factors was displayed in the Improvement for Computing Ecosystem Service Section, in which the refinement of the correction methods mainly contained the space extraction technology of the built-up boundary, the clustering technology of the land ecosystem service indicators, the mixed-pixel decomposition model, and the modified normalized difference water index for the land component correction parameters.

Improvement for Computing Ecosystem Services

- (1)

- Improved Classification of Built-up Land Ecosystem Service Indicators

The impervious surface area (ISA) and greening space constituted the predominant land cover categories in built-up regions, where the ISA was characterized by its impermeability to rainfall, encompassing roofs, roads, squares, and similar surfaces [34]. The greening spaces mainly included courtyard vegetation, lawns, roadside trees, urban parks, and other vegetated zones. Through comprehensive on-site surveys and high-resolution satellite imagery analysis, it was observed that the built-up areas in Inner Mongolia additionally comprise water bodies and bare soil. In accordance with the actual land cover distribution patterns, these regions were systematically classified into four distinct subtypes: ISA, greening spaces, bare soil, and water bodies. These classifications were subsequently consolidated into three overarching ecosystem service categories, including desert services, greening services, and water services, using the clustering technology of land ecosystem service indicators in built-up areas.

- (2)

- Determination of the Sub-land Equivalent Factor Correction Parameter

Upon completing the comprehensive internal classification of built-up land, the equivalent factor correction parameter proportion of desert space, greening space, and water space should be quantified. Within built-up regions, the spatial boundaries of urban areas, rural settlements, and independent industrial/mining lands were delineated through CLUD data encoding (i.e., codes 51, 52, and 53), by space extraction technology. These boundaries were subsequently overlaid with the 30 m resolution land components of ISA, bare soil (BS), and greening vegetation (GV) that were produced by the mixed-pixel decomposition model, all derived from CAS datasets [8,15]. Utilizing spatial analytical techniques, the mean values of the three components were derived within the specified boundaries. Water bodies were identified through the modified normalized difference water index applied to Landsat imagery. Ultimately, the equivalent factor correction parameter proportion of ISA, BS, GV, and water bodies within urbanized areas were determined.

Evaluation of ESV

This section consisted of three parts. Initially, the equivalent factor table for Inner Mongolia was formulated. Subsequently, value coefficients for distinct ecological land types were derived, wherein the per-unit-area ESV of the Inner Mongolia region was monetized. The ecosystem service coefficients were subsequently computed via mathematical statistics, employing the equivalent factor table of heterogeneous land types and the monetary value of a single equivalent factor. Ultimately, the ESV was quantified by multiplying each land value coefficient by its respective area.

- (1)

- Establishment of Equivalent Factor Table

The establishment of an equivalence factor table was conventionally guided by ecological classification principles. The equivalence factor model incorporated an intrinsic ecological classification system with associated parameter values. In this study, a one-to-one correspondence was established between land types in the CAS ecosystem classification and those embedded within the model framework, thereby enabling the transfer of model-derived ecological parameters to the CAS ecosystem classification. These parameters were subsequently refined to align with the ecological characteristics of Inner Mongolia, during which the subclass proportion parameters for built-up land were systematically incorporated (Table 2).

Table 2.

Equivalent factors of ESV.

- (2)

- Monetization of Equivalent Factor and Its Corresponding Ecological Land Value Coefficient

The standard unit of equivalent factor value was operationally defined as the economic value (i.e., the net profit per unit area of grain production) derived from the annual grain yield per hectare of agricultural land [32]. This quantification approach enabled the monetization of individual equivalent factors, thereby facilitating ecosystem service valuation, which represented the prevailing methodological framework in contemporary research. Field investigation was conducted in Inner Mongolia to identify rice, wheat, corn, and soybeans as the predominant crop types. Historical net profit data for these crops across the study period were systematically extracted from statistical yearbooks. Considering the fact this study covered a 30-year span study from 1990 to 2020, the impact of inflation may affect the calculation results. To eliminate the impact of inflation, all numerical calculations from an economic perspective were based on the 30-year average. Mathematical statistical methods were subsequently employed to derive the monetary value of a single equivalent factor using Equation (1). These processes yielded the Inner Mongolia ecosystem service monetization coefficient table, which is presented in Table 3.

where is one equivalent factor of ESV (yuan/hm2). , , , and are the proportion of rice, wheat, corn, and soybean crops in the total sowing area. , , , and are the average net profit of rice, wheat, corn, and soybean crops, respectively.

Table 3.

Value coefficients for different ecological land types (Unit: CNY/hm2).

- (3)

- Calculation of ESV

The ESV was calculated by integrating the ESV’s coefficient table with the respective areas of distinct land types. The formula is as follows:

where represents ecosystem service value, is the land area of type , and is the land value coefficient of type .

2.3.2. Flow Gain/Loss Model of ESV

The model quantified ESV variations by analyzing land use conversion process, to display the precise characterization of ESV gain/loss dynamics. The equation is presented below:

where is the change in ESV caused by the conversion from to types of land use. and are the value coefficients of and types. is the area of land use type from to .

2.3.3. Spatial Characteristics Analysis

Both global and local Moran’s I methodologies were applied to perform spatial heterogeneity analysis on the aggregation pattern of the total ESV using Equations (4)–(6). A fishnet grid system was systematically generated across the study area to quantify the spatial land type at grid cell level. Utilizing the ESV coefficients specific to distinct land cover categories, the total ESV for each pixel was quantitatively derived and subsequently spatially visualized [35].

where and are the global and local Moran index, respectively. is the number pixel, is the measure value of the pixel, is the deviation between the measure and mean on the pixel, is the standardized spatial weight matrix, is the variance.

2.3.4. GTWR Model

The advantage of the GTWR is that it can address spatial–temporal non-stationarity in regression coefficients [30,36], thereby offering a unified interpretation of the spatiotemporal heterogeneity mechanisms underlying different geographical phenomena process (Equation (7)). In this study, prior to implementing the GTWR model, we conducted a VIF analysis for the nine initially selected indicators. To address potential multicollinearity issues, a threshold value was employed as a diagnostic criterion [36], retaining only those indicators with VIF values below this established limit. This systematic screening procedure obtained a final set of five indicators: DEM, slope, temperature, precipitation, and human footprint, with corresponding VIF values of 1.491, 1.973, 2.546, 2.728, and 1.502, respectively. These selected indicators were subsequently utilized as explanatory variables in the driving factor analysis.

where is the observed value, is the spatiotemporal coordinate of the observation point; compared with the GWR model, GTWR has added a time dimension. is the intercept parameter, is the factor of the -variable at -location, is the total number of variables, is the observed value of the -variable at -location, and is the random error at the -location observation point.

To ensure the reliability and rationality of the model results, a Gaussian kernel function was systematically employed for the computation of spatiotemporal weight matrices among observational units. The optimal bandwidth parameter, which balanced the model fit and complexity, was algorithmically derived through minimization of the corrected Akaike Information Criterion (AICc). The AICc was also used as the primary goodness-of-fit criterion to compare the performance of the GWR and GTWR models, with a lower AICc value indicating a better model fit. The higher R2 and adjusted R2 values reflected stronger explanatory power of the model for the dependent variable. These clarifications pre-empted redundancy by providing a clear basis for interpreting the model comparison indices.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of the Evolved Land Changes in Inner Mongolia During 1990–2020

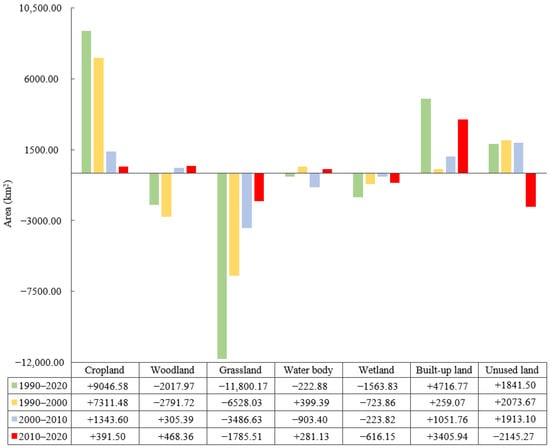

From 1990 to 2020, the land-use changes in Inner Mongolia exhibited distinct spatial–temporal patterns. Cropland and built-up land displayed continuous expansion, whereas grassland and wetland areas consistently declined. In contrast, woodland, water bodies, and unused land displayed fluctuating trends during this period (Figure 3). The expansion of cropland exhibited a decelerating growth trend. It was primarily driven by land reclamation in the first decade, but the later implementation of the ‘Grain for Green’ policy restricted further expansion of cropland area. Built-up land exhibited accelerated growth after 2000, fueled by rapid urbanization and population growth that escalated demand for infrastructure and residential development, resulting in an expansion rate 8.6 times higher than that of the first decade. Despite both grassland and wetland showing a decrease across all time periods, the decline in the grassland area lessened, primarily because of ecological protection measures. In contrast, wetland exhibited a trend of reduction characterized by acceleration–deceleration–acceleration. This was caused by the initial expansion of agricultural and built-up land, the mitigating effect of ecological protection policies in the middle period, and higher temperature leading to increased evaporation in the final phase. Simultaneously, the status of woodland was characterized by a decrease–increase–increase pattern, water body followed an increase–decrease–increase pattern, and unused land showed an increase–increase–decrease pattern.

Figure 3.

Column statistics and 10-year interval dynamic trends of land changes in Inner Mongolia during 1990–2020.

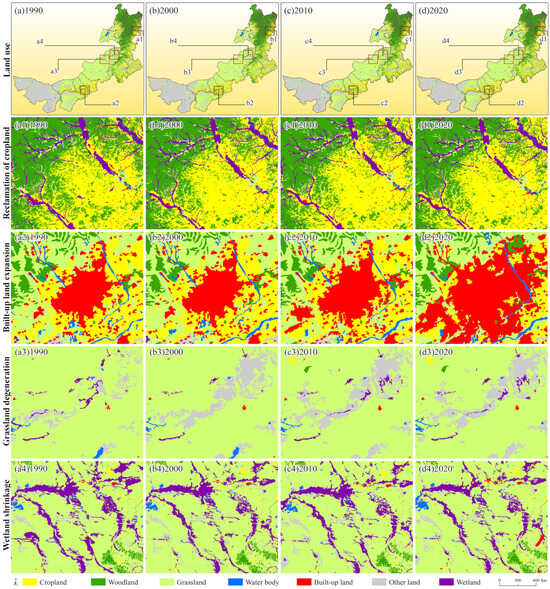

Figure 4 reveals that the predominant land spatial distribution types in Inner Mongolia were woodland, grassland, and unused land, exhibiting a distinct stepped east–west gradient across the region. Among these land types, woodland was concentrated in Hulunbuir and Hinggan League, attributable to the implementation of Three-North Shelter Forest Program of China. Grassland exhibited a focal distribution in Xilingol League and Ordos, while unused land, primarily comprising desert areas, showed extensive spatial coverage across Alxa League. There are three deserts in Alxa League, including the Badain Jaran desert, Tengger desert, and Ulan Buhe desert, because the arid/semi-arid climatic conditions coupled with low precipitation levels acted as substantial constraints on the large-scale planting of woodland or grassland vegetation.

Figure 4.

Multi-temporal spatial patterns of land use and their typical land type changes from cropland (a1–d1), built-up land (a2–d2), grassland (a3–d3), and wetland (a4–d4) in Inner Mongolia during 1990–2020.

3.2. Analysis of the Spatiotemporal Changes of ESV in Inner Mongolia from 1990 to 2020

Throughout the study period, the variations in the total ESV within Inner Mongolia exhibited a fluctuating pattern, characterized by a general downward trajectory (Table 4). Specifically, the ESV declined from CNY 5515.316 billion to CNY 5425.188 billion during 1990–2020, reflecting an average annual reduction of CNY 3.004 billion. The changing trend of ESV in Inner Mongolia was influenced by grassland, wetland, woodland, and water body ecosystems. The ESV declined by CNY 65.513 billion for grassland, CNY 28.576 billion for wetland, and CNY 12.217 billion for woodland. The primary factors driving this trend were the reclamation of cropland, the expansion of built-up areas, and excessive grazing practices. Additionally, substantial agricultural water consumption and climatic limitations led to a reduction in water services from CNY 629.821 to 619.986 billion during 1990–2020, marking a decline of CNY 9.835 billion over the 30-year period. The land service values of other lands such as unused land, built-up land, and cropland exhibited opposite trends, with corresponding values of +12.732 billion CNY, +12.440 billion CNY, and +0.841 billion CNY, though these values were comparatively lower than those of grassland, wetland, woodland, and water bodies.

Table 4.

Changes in ecosystem service in Inner Mongolia from 1990 to 2020 (×108 CNY).

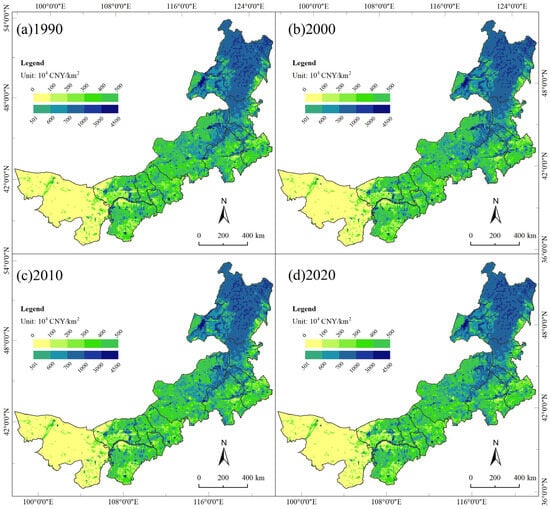

Regarding the changes in spatial distribution, high ESV was concentrated in the eastern region, medium ESV in the central region, and low ESV in the western region, indicating an east-to-west declining gradient across Inner Mongolia (Figure 5). This pattern is closely linked to the distribution of land-use types. Quantitatively, grasslands and forests were the principal contributors to the total ESV, comprising 65.86% of the regional total changes. In contrast, croplands, built-up areas, and unused land types collectively contributed less than 10%. At the administrative level, high-ESV zones were concentrated in Hulunbuir, a region characterized by extensive land types of grassland and forest coverage. Meanwhile, the observed ESV decline in the central and western regions was primarily attributed to land-use transitions, particularly from grassland to cropland, which accounted for 21.32% of the total ESV loss. Conversely, the primary driver of ESV enhancement was the reversion of croplands and unused lands to forests and grasslands, contributing 28.92% to the total ESV gain over the studied period. Then, middle values were widespread in the cities of Hohhot, Baotou, and Ordos, and only a small number of high-values were distributed in northern Baotou and western Ordos. Meanwhile, the cities of Tongliao and Chifeng were mainly situated in the middle values. The low values were located in the southern part of Ulanqab, Alxa League, and Wuhai.

Figure 5.

Maps of ESV in Inner Mongolia from 1990 to 2020.

3.3. Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis of ESV

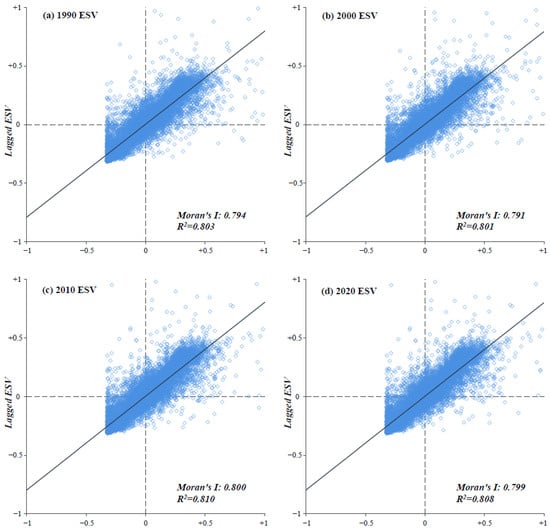

Moran’s I parameters for ESV across Inner Mongolia were calculated for 1990, 2000, 2010, and 2020, with the results indicating significant positive spatial autocorrelation in ESV distribution (Table 5 and Figure 6).

Table 5.

Global Moran’s I statistic of ESV at the fishnet grid scale.

Figure 6.

Moran’s I scatter plot of Inner Mongolia from 1990 to 2020.

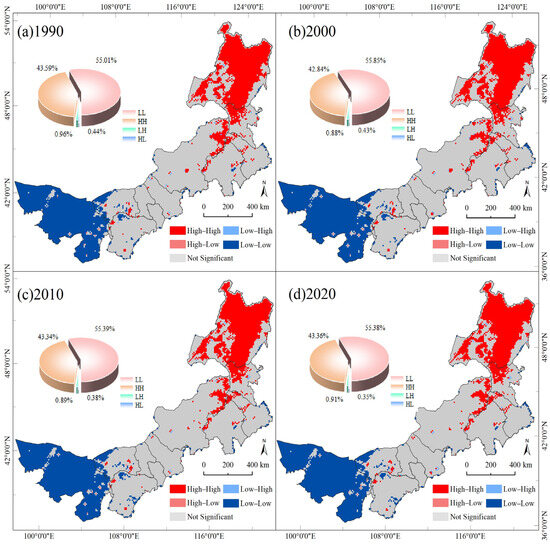

As shown in Figure 7, a consistent spatial pattern of ESV in Inner Mongolia was observed from 1990 to 2020, characterized by spatial clustering features of high–high (i.e., H–H) and low–low (i.e., L–L) types. The high–high clusters mainly occurred in eastern Inner Mongolia, including Hulunbuir, northern Hinggan League, and eastern Xilingol League. They were also found sporadically in northern and central parts of Tongliao, as well as the eastern part of Chifeng. The main reason was that these regions possessed abundant natural and tourism resources and also served as important bases for animal husbandry. Furthermore, with the support of policies such as the Green for Grain Project and delimitation of an ecological protection red line in China, the economic development has been relatively strong, resulting in a high-value spatial agglomeration. Low–low clusters were mainly found in Alxa League in western Inner Mongolia. There were also small distributions in Bayannur and northern Ordos. This pattern result from the arid climate, harsh natural environment, and fragile ecological conditions in the western region. These factors limited synergistic development among nearby areas. High–low clusters occurred sporadically in southern Alxa League, while low–high clusters were found sporadically in the central Inner Mongolia prefecture-level cities.

Figure 7.

LISA cluster of ESV from 1990 to 2020.

3.4. Gain and Loss Analysis of ESV from 1990 to 2020

Through the application of the land transfer technology and Equation (3), the ESV gain–loss matrix was calculated for Inner Mongolia from 1990 to 2020 (Table 6). The total ESV loss was CNY 90.128 billion from 1990 to 2020. Specifically, the losses amounted to CNY 50.646 and 47.297 billion from 1990 to 2000 and 2000 to 2010, respectively, while a gain of CNY 7.815 billion yuan was recorded for the period 2010–2020.

Table 6.

Value flows of gain and loss of various ecosystem service (×108 CNY).

From 1990 to 2020, the ESV losses resulting from outflow from water bodies, grassland, wetlands, and woodland amounted to CNY 73.555, 56.209, 37.389, and 9.987 billion, respectively. In contrast, the outflow from cropland, unused land, and built-up land generated ESV gains of CNY 44.908, 41.783, and 0.321 billion, respectively. Therefore, the ESV of conversion from water bodies to other land use types was entirely negative, indicating that water bodies exhibited the highest ESV among all land types. On the contrary, the converted ESV from cropland to built-up land was positive. It may imply that the proportion of types such as green space within built-up land increased. This land configuration offered support for enhancing urban greening, alleviating the urban heat island effect, and regulating the microclimate. Meanwhile, when analyzing different time periods, the outflow from water bodies and wetlands consistently reduced the ESV throughout each period, while the outflow from land types of unused land, cropland, and built-up land contributed to ESV increases.

3.5. Analysis of the Driving Mechanism of ESV Changes

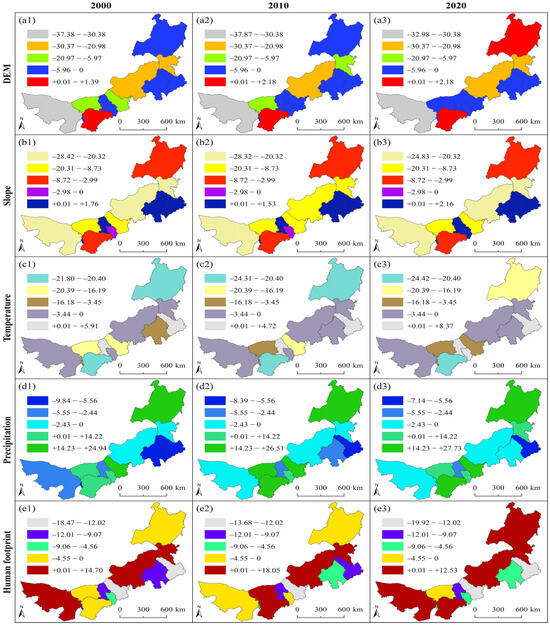

This study selected the DEM, slope, temperature, precipitation, and human footprint as key factors. The aim was to explore how natural environments and human activities differentially affected ESV across time and space (Table 7 and Figure 8). Among natural factors, with respect to the selection of static topographic factors, namely the DEM and slope, although their values remained constant throughout the period from 2000 to 2020, their influence on the dynamics of ESV manifested through the temporal variations in their interaction with dynamic factors, including temperature and precipitation. Specifically, the DEM played a crucial role in regulating the spatial distribution of water and heat, such as the higher altitude and lower temperature, thereby affecting the distribution of vegetation. Similarly, the slope of the terrain impacts soil moisture retention and erosion intensity and further affects vegetation under different lighting and rainfall conditions. Meanwhile, the examination of driving factors was performed at the administrative division unit level, specifically encompassing prefecture-level leagues and cities. This methodological selection was predicated upon the fact that ecosystem management and conservation initiatives, including desertification control policies, enclosure projects, and the returning grazing to grassland program, were administratively implemented at these jurisdictional levels. Meanwhile, the compilation of socio-economic data was conducted at this corresponding scale. By executing the analysis of influencing factors on ecosystem services at the prefecture-level league or city administrative units, it became more feasible to discern disparities in ecological services from an administrative standpoint and thereby facilitated ecosystem restoration efforts.

Table 7.

Fitting parameters of different models.

Figure 8.

Contributions of the influencing factors to the ESV. The contributions of DEM (a1–a3), slope (b1–b3), temperature (c1–c3), precipitation (d1–d3), human footprint (e1–e3) during 2000–2020.

Over the period 2000–2020, the DEM primarily exerted an inhibitory effect on Inner Mongolia’s ESV (Figure 8(a1–a3)). Spatially, Alxa League exhibited the highest degree of negative contribution, whereas Ordos recorded the highest positive contribution. Starting in 2010, the negative contribution continually lessened in Ulanqab, and similarly, beginning in 2020, the negative contribution also decreased in Bayannur. Conversely, its positive impact on Hulunbuir enhanced. From the perspective of the contribution values, the inhibitory effect of slope on ESV exceeded its promoting effect (Figure 8(b1–b3)). Temperature predominantly exerted a negative influence on ESV, with the highest inhibition in Hulunbuir and Ordos (Figure 8(c1–c3)). Conversely, it positively influenced the ESV in Baotou and Tongliao. Thus, the inhibitory effect in Chifeng and Bayannur began to decrease starting in 2010, and similarly, it started to decrease in Ulanqab from 2020. For numerical values, there was a continuous declining trend in the negative impact of precipitation on ESV, alongside a simultaneous increase in its positive impact (Figure 8(d1–d3)). This suggested that adequate precipitation could enhance the state of ecosystem services. With temporal progression, the influence of anthropogenic activities on ESV exhibited an improvement trajectory (Figure 8(e1–e3)). The initial suppression effect was primarily attributable to overgrazing, which induced a substantial contraction of grassland area and consequent ESV decline.

4. Discussion

4.1. Ecosystem Services Considering the Internal Structure of Build-Up Land Were First Investigated in the Ecological Barrier Region of Northern China

For the first time in the academic field, this research quantified the spatiotemporal ESV evolution in Inner Mongolia, the fragile ecosystem region of China, from 1990 to 2020, with the explicit inclusion of build-up land factors. The equivalent factor model has been widely employed as the primary method for ESV assessments in China. While many researchers have adapted this approach to suit specific study contexts, there is still insufficient research addressing land structure classification within built-up areas [37]. Conventional studies often assigned the desert system value to the ESV of built-up land [38]. Nevertheless, given the growing proportion of artificial green spaces and water bodies within urbanized areas, their contribution to ecosystem services should not be overlooked, especially in fragile ecosystem areas, such as Inner Mongolia, China [39]. Therefore, utilizing remote sensing satellite technology and field research, we classified build-up land into four distinct types, including impervious surfaces, green spaces, bare soil, and water bodies. A comparative variable experiment was conducted, wherein the ecosystem was compared through both the original model and our improved model. The results displayed that the ESV increments from built-up land in 1990, 2000, 2010, and 2020 amounted to CNY 29.109, 29.897, 32.607, and 41.549 billion, respectively, which was the first report in the Inner Mongolia region of China.

We further investigated the drivers behind the rise in ecosystem services within urban and rural construction land regions. In terms of cities, the urban expansion and development policies resulted in a heightened proportion of green spaces and water bodies within urban areas. Specifically, the enhancement and renovation of urban park landscapes, the afforestation and greening of residential zones, and the creation of artificial lakes have substantially improved human living comfort [40]. In terms of rural areas, the construction of new rural internal land structure paid more attention to the ecological preservation and blue–green landscape integration within village settlements. This approach not only created aesthetically pleasing environments for residents but also stimulated rural tourism development, thereby boosting local economic growth while enhancing rural ecosystem service provision. According to our statistical analysis, these two factors accounted for 47.82% of the total ESV changes over the 30-year study period. Consequently, the newly improved method effectively assessed the ecosystem service capacity of urban–rural areas, offering more precise scientific insights for environmental assessments in arid and ecologically fragile in China and abroad.

4.2. Small-Scale Land Variables with Large Ecological Service Impacts Were Quantified in China’s Arid/Semi-Arid Zones in Inner Mongolia, China

Inner Mongolia in China encompassed extensive desert areas, as well as significant amounts of built-up land and cropland. These land types generally provided relatively low ecosystem services [41]. Despite their substantial area fluctuations, their influence on regional ecosystem changes remained the limited in terms of decisive impact. Through the investigation of this study, the ESV decreased from CNY 5515.316 billion to CNY 5425.188 billion from 1990 to 2020 in the whole region, with net changes of −90.128 billion CNY. This change was determined by grassland, wetland, woodland, and water bodies. According to the monitoring results, the combined proportion of grassland, woodland, wetland, and water body land use types decreased from 62.71% in 1990 to 61.34% in 2020, only a relatively minor fluctuation of −1.37%; however, this decline resulted in an ESV loss of CNY 116.141 billion (i.e., Table 4 and Figure 3 and Figure 4). This means that this change exceeded the reduced quantity observed across the entire study area during the same period. This study marked the first quantification of such ESV losses in China’s arid/semi-arid regions from 1990 to 2020, namely, Inner Mongolia.

We also searched the previous literature to find whether there was other research assessing the ecosystem services change from other aspects, using the similarity and differences analysis in the ecologically fragile areas and arid/semi-arid areas. The previous research on ecosystem service dynamics in these regions has predominantly explored two non-value dimensions (i.e., function and structure). Functionally, lots of investigations have centered on single-service evaluations, such as soil conservation, carbon sequestration, and water regulation [21,39]. These studies lacked a comprehensive value quantification. Structurally, most of the research efforts have frequently relied on land use transfer matrices to analyze the trajectories of ecosystem changes [41]. Nevertheless, there was a dearth of quantification regarding the ‘disproportionate impact’ of small yet high-value land types (e.g., wetlands and water bodies) on the large ESV changes (i.e., slight change, huge loss). This study firstly revealed the phenomenon that the small reduction in the areas of grassland, wetland, woodland, and water bodies resulted in the huge ESV loss, displaying an important scientific research value in the ecologically fragile areas and arid/semi-arid areas.

For high ecological land types such as forests, grasslands, and wetlands, water body areas exhibited an increasing–decreasing–increasing fluctuating trend, declining to the minimum value in 2010. In 2010, the region’s total ESV also reached its lowest point, amounting to CNY 5417.373 billion. This indicates that the dynamic changes in water bodies emerged as the predominant factor influencing regional ESV fluctuations compared to other land types, since water bodies had the highest per-unit-area value across all land categories. Wetland was also recognized as a high ecological value land type [42]. Wetland and water bodies played a fundamental role in maintaining the water cycle balance and mitigating climate change by conserving water and regulating runoff. They are particularly crucial for hydrological and climate regulation [21]. Meanwhile, grassland and woodland ecosystems provided essential foundations for soil formation, nutrient cycling, and biodiversity preservation through vegetation-based carbon sequestration and oxygen production [24]. These four land use types of grassland, wetland, woodland, and water body together formed the core parts for the region’s ecosystem services. They not only provided high-value ecosystem services numerically but also carried important ecological functions in Inner Mongolia.

4.3. A Comparison of Ecosystem Services from This Study and Other Regions

From a comparative regional perspective, the arid/semi-arid regions exhibited a distinct pattern characterized by “Slight Change, Huge Loss.” Specifically, small-scale land variables with high ecological value, such as forests, grasslands, and wetlands, drove significant fluctuations in ecosystem services. This phenomenon may be attributed to the prevalence of low-ecological-value deserts in arid areas, where the small loss of high-ecological-value land disproportionately impacted regional ecosystem services.

A similar trend was observed in Northeast China’s agricultural zones, a region renowned for its fertile land, flat terrain, and high agricultural productivity—often referred to as China’s “granary.” Over the past half century, this area experienced dramatic land-use changes, marked by the rapid expansion of low-ecological-value cropland and substantial declines in high-ecological-value forests, grasslands, and wetlands [43].

In contrast to Inner Mongolia’s arid/semi-arid regions and Northeast China’s agricultural areas, Southeast China, a rapidly developing economic region, demonstrated different impacts from agricultural land loss, urban/rural expansion, and the construction of industrial-mining land. These land-use changes exerted profound spatiotemporal effects on ecosystems [44]. Consequently, differentiated land-change patterns in Inner Mongolia, Northeast China, and Southeast China collectively shaped region-specific trajectories of ecosystems.

4.4. Screening Influencing Factors and Spatiotemporal Heterogeneity Analysis Through Different Models

Following a comprehensive review of the pertinent literature and in consideration of Inner Mongolia’s distinctive natural environment, this study adopted nine key indicators, namely, DEM, slope, temperature, precipitation, soil wind erosion, FVC, NDVI, NPP, and human footprint, to systematically investigate the influencing factors of ESV [18,25]. Given the similar functions of these indicators, the factor analysis was prone to multicollinearity issues, which could obscure the distinct contributions of individual predictors. The OLS model was suitable for analyzing data with uniform distribution and multicollinearity relationships. To mitigate this, the OLS model was employed to iteratively remove variables exhibiting a VIF exceeding 7.5 (i.e., a commonly threshold) to quantify the relationships between these factors and ESV and, further, to more accurately analyze the driving effects of these factors on ESV [36]. Through rigorous application of the aforementioned methodology, the analysis obtained five key determinants exhibiting significant influence, namely, the DEM, slope, temperature, precipitation, and human footprint. After completing the screening of the number of driving factors, the OLS model could not reflect spatiotemporal heterogeneity [25]. To explore the driving forces underlying the spatiotemporal heterogeneity of ESV, we further used the GTWR model. By incorporating both temporal and spatial dimensions, the GTWR assigned location-and-time-specific weights to each data point, enabling a dynamic capture of how relationships change across different times and places. This avoided the limitations of global linear regression, rendering it particularly well-suited for analyzing highly complex spatiotemporal processes (Table 7). To address the inherent challenges in indicator selection and spatiotemporal heterogeneity analysis, this study employed a multi-model approach, strategically leveraging the complementary strengths of each modeling approach (e.g., OLS for collinearity control, GTWR for spatiotemporal heterogeneity). This methodology was specifically designed to mitigate indicator redundancy and enable rigorous quantification of spatiotemporal variability.

4.5. Causal Mechanisms and Policy Implications

Our research primarily focused on the impact of land use change on ecosystem services within the ecological barrier zone of northern China, Inner Mongolia. It was found that the loss of small-scale high-value forests, grasslands, wetlands, and water bodies has resulted in a huge decline in ecosystem services on the background of widespread drought and the desertification of land. Additionally, we examined the spatiotemporal heterogeneity of ecosystem services. The causal mechanism behind these findings in ecosystem services stemming from land evolution is shaped by a multitude of factors, including the natural environment, policy orientation, and human activities. In detail, the climate characteristics, ranging from humid to semi-humid, semi-arid, and arid regions from east to west, drive the transition of land use from forest and grassland in the east to desert in the west, thereby creating a gradient effect in the ESV distribution from east to west. Concurrently, the targeted ecological policies such as the Three-North Shelterbelt, Grain-for-Green, and Grassland Protection initiatives serve as pivotal intervention variables, modifying land use structures (e.g., expanding ecological land and restoring degraded land) to enhance ecosystem functions and ultimately achieve ESV improvement [45,46]. Moreover, the impact of land on ESV is more pronounced in areas adjacent to cities, rural regions, and industrial and mining zones due to the influence of humans and production activities [9]. Thus, a causal mechanism is formed for the multidimensional impact of land changes on ESV.

To address the complex challenges identified in this causal mechanism, a more in-depth process should be integrated from a policy perspective, considering both the natural environment and human activities, including multi-level and differentiated policies and engineering measures. Firstly, the synergy of ecological policies can be strengthened by integrating engineering projects, financial subsidies, and regulatory measures into a cohesive system. This approach aims to address regional disparities in ecosystem services by prioritizing the protection or restoration of high-value land types (i.e., forest, grassland, and wetland) in the eastern region, balancing ecological and production functions in the central transitional zone, and intensifying restoration efforts in the fragile western region (i.e., desert land). Secondly, in the east, central, or western regions, government departments should enhance the implementation of ecological protection projects/policies tailored to distinct natural environments and human activity variations, with particular emphasis on key biological protection areas. Finally, at the local scale, land use planning should prioritize ecological security and appropriately restrict the expansion of non-ecological land to safeguard the stability of critical ecological spaces [47].

4.6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Despite the 30-year temporal scope of this study, some land-use changes and their ecological functional effects necessitated longer observation periods to obtain more robust scientific insights. Concurrently, the study concentrated on arid and semi-arid regions of China. It is noteworthy that analogous climatic zones exist globally, including Central Asia, Africa, and other regions. Building upon this study’s quantification of land variables and their ecological impacts, future research should pursue two key directions: Firstly, we will implement more long spatiotemporal analyses to examine the temporal dynamics and spatial heterogeneity of ecosystem services, such as carbon sequestration and water regulation, in response to land-use change [48]. Secondly, we will expand the scope to other global arid/semi-arid regions through comparative studies to evaluate the generalizability of these findings from this study and, further, to elucidate region-specific drivers of ecosystem service variability and their relevance for sustainable land management practices [49]. A limitation of the current study is the absence of spatial scale sensitivity analysis within the GWR-family models. To address this issue, in future, we will explicitly justify the selection of grid cell dimensions and bandwidth parameters for each predictor variable. Further, multi-scale robustness checks to assess the parameter stability across spatial resolutions will be implemented.

5. Conclusions

This study applied an integrated methodology that includes arithmetic statistics, spatial analysis technology, field investigation, model simulation, and improved ecosystem measurement models to address spatiotemporal changes and define their driving factors across the Inner Mongolia in Northern China. The main conclusions of this research are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- Remote sensing revealed cropland and built-up areas expanded persistently, while grassland and wetland declined. Spatially, forest, grassland, and unused land dominated sequentially along the east–west gradient.

- (2)

- Ecosystem service accounting for built-up land internal structure in Northern China’s ecological barrier region was first examined, where the ESV declined from CNY 5515.316 billion to CNY 5425.188 billion from 1990 to 2020.

- (3)

- Another key finding was that small-scale variables with significant ecological service impacts were quantified: only a relatively minor fluctuation of −1.37% among the grassland, woodland, wetland, and water bodies resulted in a huge ESV loss of CNY 116.141 billion, with ESV trends primarily driven by these four land cover types.

- (4)

- The ESV displayed obviously spatial agglomeration effects. The high–high clusters were primarily concentrated in eastern Inner Mongolia, but the low–low clusters were predominantly distributed across the western region and centered around Alxa League.

- (5)

- From the driving perspective, the DEM, slope, and temperature exerted significant negative effects on ESV, but precipitation and human footprint displayed positive correlations during the study period.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Y.; methodology, Z.Y., C.G., W.B. and Z.W.; formal analysis, Z.Y. and W.K.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Y.; writing—review and editing, W.K., G.H., Y.H. and Y.D., funding acquisition, Z.Y. and W.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Planning Project in Inner Mongolia, grant numbers 2025YFHH0200 and 2025KJHZ0060, and the Postgraduate Research Innovation Project of Department of Education of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, grant number KC2024029B.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editor and anonymous reviewers for their helpful and constructive comments to improve this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ESV | Ecosystem Service Value |

| GLASS-GLC | Global Land Surface Satellite–Annual Dynamics of Global Land Cover |

| MODIS | Moderate-resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer |

| ESA CCI-LC | European Space Agency Climate Change Initiative Land Cover |

| CAS | Chinese Academy of Sciences |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares Regression |

| GD | Geographic Detector |

| GWR | Geographically Weighted Regression |

| GTWR | Geographically and Temporally Weighted Regression |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| NPP | Net Primary Productivity |

| FVC | Fractional Vegetation Cover |

| CLUD | China Land Use/Cover Dataset |

| UEMM | Urban Environment Monitoring and Modeling |

| ISA | Impervious Surface Area |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

References

- Costanza, R.; d’Arge, R.; De Groot, R.; Farber, S.; Grasso, M.; Hannon, B.; Limburg, K.; Naeem, S.; O’Neill, R.V.; Paruelo, J. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 1997, 387, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiszewski, I.; Costanza, R.; Anderson, S.; Sutton, P. The future value of ecosystem services: Global scenarios and national implications. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 26, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; De Groot, R.; Sutton, P.; Van der Ploeg, S.; Anderson, S.J.; Kubiszewski, I.; Farber, S.; Turner, R.K. Changes in the global value of ecosystem services. Global Environ. Change 2014, 26, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, G.C.; Söderqvist, T.; Aniyar, S.; Arrow, K.; Dasgupta, P.; Ehrlich, P.R.; Folke, C.; Jansson, A.; Jansson, B.O.; Kautsky, N. The value of nature and the nature of value. Science 2000, 289, 395–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Zhang, C.; Zhen, L.; Zhang, L. Dynamic changes in the value of China’s ecosystem services. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 26, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Qiu, J.; Amani-Beni, M.; Wang, Y.; Yang, M.; Chen, J. A modified equivalent factor method evaluation model based on land use changes in Tianfu new area. Land 2023, 12, 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wang, R.; Paulussen, J.; Liu, X. Comprehensive concept planning of urban greening based on ecological principles: A case study in Beijing, China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2005, 72, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, W.; Zhang, S.; Li, X.; Lu, D. A 30 m resolution dataset of China’s urban impervious surface area and green space, 2000–2018. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuai, X.; Huang, X.; Wu, C.; Li, J.; Lu, Q.; Qi, X.; Zhang, M.; Zuo, T.; Lu, J. Land use and ecosystems services value changes and ecological land management in coastal Jiangsu, China. Habitat. Int. 2016, 57, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Li, J.; Ye, M.; Pu, R.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Q.; Feng, B.; Song, X. Changes of ecosystem service value in a coastal zone of Zhejiang province, China, during rapid urbanization. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Tian, L.; Lin, M.; Xu, S.; Zhu, C. A Comparison of recent global time-series land cover products. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cao, J.; Zhu, C.; Yang, H. The impact of land use change on ecosystem service value in the upstream of Xiong’an new area. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, J.; Liu, J.; Kuang, W.; Xu, X.; Zhang, S.; Yan, C.; Li, R.; Wu, S.; Hu, Y.; Du, G. Spatiotemporal patterns and characteristics of land-use change in China during 2010–2015. J. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Kuang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, X.; Qin, Y.; Ning, J.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, S.; Li, R.; Yan, C. Spatiotemporal characteristics, patterns, and causes of land-use changes in China since the late 1980s. J. Geogr. Sci. 2014, 24, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, W.; Zhang, S.; Du, G.; Yan, C.; Wu, S.; Li, R.; Lu, D.; Pan, T.; Ning, J.; Guo, C. Monitoring periodically national land use changes and analyzing their spatiotemporal patterns in China during 2015–2020. J. Geogr. Sci. 2022, 32, 1705–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yi, P.; Xia, J.; He, W.; Gao, X. Temporal and spatial analysis of the ecosystem service values in the Three Gorges Reservoir area of China based on land use change. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 2022, 29, 26549–26563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Bai, H.; Luo, P.; Liu, J. Spatio-temporal evolution and coupled coordination of LUCC and ESV in cities of the Transition Zone, Shenmu City, China. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shataer, R.; Zhang, Z.; Zhen, H.; Xia, T. Evaluation and analysis of influencing factors of ecosystem service value change in Xinjiang under different land use types. Water 2022, 14, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Zheng, G.; Liang, T. The impact of land use and land cover changes on the landscape pattern and ecosystem service value in Sanjiangyuan region of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 325, 116539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Liu, C.; Shan, L.; Lin, J.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, G. Spatial-Temporal responses of ecosystem services to land use transformation driven by rapid urbanization: A case study of Hubei Province, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 19, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.S.; Zhen, L.; Miah, M.G.; Ahamed, T.; Samie, A. Impact of land use change on ecosystem services: A review. Environ. Dev. 2020, 34, 100527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzman, J.; Bennett, G.; Carroll, N.; Goldstein, A.; Jenkins, M. The global status and trends of Payments for Ecosystem Services. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Tang, H.; Wang, B.; Chen, J. Effects of land-use intensity on ecosystem services and human well-being: A case study in Huailai County, China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Liu, H.; Xu, Z.; Ren, J.; Lu, N.; Fan, W.; Zhang, P.; Dong, X. Linking ecosystem services supply, social demand and human well-being in a typical mountain–oasis–desert area, Xinjiang, China. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 31, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liu, X.; Yang, L.; Zhu, Z. Variations in ecosystem service value and its driving factors in the Nanjing Metropolitan Area of China. Forests 2023, 14, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xue, H.; Li, A.; Ma, X.; Sun, A.; Zhang, J. Spatial-temporal differentiation and influencing factors of ecosystem health in Three-River-Source national Park. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 171, 113183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Kang, F.; Han, H.; Cheng, X.; Li, Z. Exploring drivers of ecosystem services variation from a geospatial perspective: Insights from China’s Shanxi Province. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 131, 108188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Zhang, X.; Halik, Ü. The driving mechanism and spatio-temporal nonstationarity of oasis urban green landscape pattern changes in Urumqi. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D. Spatially varying development mechanisms in the Greater Beijing Area: A geographically weighted regression investigation. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2006, 40, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Wang, Z.; Du, Z.; Huang, B.; Zhang, F.; Liu, R. Geographically and temporally neural network weighted regression for modeling spatiotemporal non-stationary relationships. Int. J Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2021, 35, 582–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.; Li, X.; Wen, Y.; Huang, J.; Du, P.; Su, W.; Miao, S.; Geng, M. A global record of annual terrestrial Human Footprint dataset from 2000 to 2018. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, L.; Chen, W.; Li, S. Improvement of the evaluation method for ecosystem service value based on per unit area. J. Nat. Resour. 2015, 30, 1243–1254. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, T.; Xu, Y.; Jones, L.; Boeing, W.J.; Calfapietra, C. Green infrastructure sustains the food-energy-water-habitat nexus. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 98, 104845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, W. Mapping global impervious surface area and green space within urban environments. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2019, 62, 1591–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ji, J. Spatiotemporal differentiation of ecosystem service value and its drivers in the Jiangsu Coastal Zone, Eastern China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Luo, X.; Ma, C.; Xiao, D. Spatial-temporal analysis of pedestrian injury severity with geographically and temporally weighted regression model in Hong Kong. Transport. Res. F Traf. Psychol. Behav. 2020, 69, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, Z.; Du, H.; Li, H. Response of ecosystem service value to LULC under multi-scenario simulation considering policy spatial constraints: A case study of an ecological barrier region in China. Land 2025, 14, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; An, M.; He, W.; Wu, Y. Research on land use optimization based on PSO-GA model with the goals of increasing economic benefits and ecosystem services value. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 119, 106072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luederitz, C.; Brink, E.; Gralla, F.; Hermelingmeier, V.; Meyer, M.; Niven, L.; Panzer, L.; Partelow, S.; Rau, A.-L.; Sasaki, R. A review of urban ecosystem services: Six key challenges for future research. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 14, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, Y.C. Spatial–temporal dynamics of urban green space in response to rapid urbanization and greening policies. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 100, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, A.; Sardans, J.; Zeng, F.; Graciano, C.; Hughes, A.C.; Farré-Armengol, G.; Peñuelas, J. Impact of aridity rise and arid lands expansion on carbon-storing capacity, biodiversity loss, and ecosystem services. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Li, J.; Yang, J.; Li, S.; Tang, W. Land use and land cover change in the Qinghai Lake region of the Tibetan Plateau and its impact on ecosystem services. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, J.; Huang, S. Evaluation of cultivated land ecosystem service value in the black soil region of Northeast China. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Y.; Wang, H.; Ou, W.; Guo, J. A land-cover-based approach to assessing ecosystem services supply and demand dynamics in the rapidly urbanizing Yangtze River Delta region. Land Use Policy 2018, 72, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Niu, X.; Wang, B. Prediction of ecosystem service function of Grain for Green Project based on ensemble learning. Forests 2021, 12, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. Effect of the Grain for Green Project on freshwater ecosystem services under drought stress. J. Mt. Sci. 2022, 19, 974–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; Liu, Y.; Meadows, M.E. Ecological restoration for sustainable development in China. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2023, 10, nwad033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Liu, M. Relationships among LUCC, ecosystem services and human well-being. J. Beijing Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2022, 58, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhard, B.; Crossman, N.; Nedkov, S.; Petz, K.; Alkemade, R. Mapping and modelling ecosystem services for science, policy and practice. Ecosyst. Serv. 2013, 4, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).