Highlights

What are the main findings?

- An infrared–visible fusion network, named MSDF-Mamba, is proposed for vehicle detection in aerial imagery. MSDF-Mamba addresses the problem of infrared–visible images’ misalignment, providing a mutual-referenced solution for target misalignment correction. Its fusion mechanism is also designed to enhance detection performance while keeping low computational costs.

- A Mutual-Spectrum Deformable Alignment (MSDA) module is introduced to achieve precise spatial alignment of cross-modal objects, and a Selective Scan Fusion (SSF) module is designed to enhance the fusion capability of dual-modal features. Experimental results on two cross-modal benchmark datasets, DroneVehicle and DVTOD, demonstrate that our method achieves an mAP of 82.5% and 86.4%, respectively, significantly outperforming other fusion detection methods.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- By taking full advantage between visible and infrared modalities, this study offers a feasible fusion detection approach for all-day object detection.

- This work provides a high-accuracy, low-complexity Mamba network solution for cross-modal vehicle detection on UAV platforms.

Abstract

To ensure all-day detection performance, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) usually need both visible and infrared images for dual-modality fusion object detection. However, misalignment between the RGB-IR image pairs and complexity of fusion models constrain the fusion detection performance. Specifically, typical alignment methods choose only one modality as a reference modality, leading to excessive dependence on the chosen modality quality. Furthermore, current multimodal fusion detection methods still struggle to strike a balance between high accuracy and low computational complexity, thus making the deployment of these models on resource-constrained UAV platforms a challenge. In order to solve the above problems, this paper proposes a dual-modality UAV image target detection method named Mutual-Spectrum Perception Deformable Fusion Mamba (MSDF-Mamba). First, we designed a Mutual Spectral Deformable Alignment (MSDA) module. This module employs a bidirectional cross-attention mechanism to enable one modality to actively extract the semantic information of the other, generating fusion features rich in cross-modal context as shared references. These fusion features are then used to predict spatial offsets, with deformable convolutions achieving feature alignment. Based on the MSDA module, a Selective Scan Fusion (SSF) module is carefully designed to project the aligned features onto a unified hidden state space. With this method, we achieve full interaction and enhanced fusion of intermodal features with low computational complexity. Experiment results demonstrate that our method outperforms existing state-of-the-art cross-modality detection methods on the mAP metric, achieving a relative improvement of 3.1% compared to baseline models such as DMM, while still maintaining high computational efficiency.

1. Introduction

In drone remote sensing, object detection technology serves as a critical foundation for environmental perception [1]. Existing unimodal detection methods have demonstrated remarkable performance. For example, Zhang et al. [2] proposed an infrared target detection approach based on a feature modulation network, which enables real-time and accurate detection in complex backgrounds through nonlocal quadrature difference measure and multi-scale receptive field design. However, unimodal approaches suffer from inherent limitations: infrared images lack texture and color information, while visible images suffer from severe information degradation under low-light conditions. These limitations restrict their detection accuracy and robustness in all-day scenarios.

Recently, visible–infrared (RGB-IR) object detection on UAVs has attracted significant attention due to its ability to fully leverage complementary information and achieve robust all-day detection [3,4,5]. However, the visible and infrared images collected by different sensors are often not aligned correctly, resulting in misalignment of the interesting targets in the same observation scenario, as shown in Figure 1. This poses challenges to effective feature fusion in traditional cross-modal methods. Although extensive research has focused on achieving image preregistration, precise image alignment for UAVs remains challenging in practice. This challenge arises from the factors such as different imaging times of each sensor, diverse fields of viewing, and complex target motion [6].

Figure 1.

Target misalignment between visible and infrared images. These two images are selected from the DroneVehicle dataset, where the bounding box in the visible modality is indicated by a solid red line, while the dashed yellow line represents the infrared modality. Due to factors such as calibration errors in the capture device and shooting angle discrepancies, the paired images cannot be perfectly aligned. This results in positional misalignment of the annotated target bounding boxes.

To address image misalignment, researchers have proposed various approaches. For example, Zhang et al. [7] introduced a novel region feature alignment module that predicts regional offsets by improving methods with adjacent similarity constraints. Yuan et al. [8] introduced C2Former, a framework based on the Transformer architecture. They designed an inter-modality cross-attention (ICA) module. This module learns the cross-attention relationship between the RGB and IR modality to obtain the calibrated and complementary features. It achieves both feature calibration and complementary fusion, achieving an mAP of 74.2% on the UAV benchmark dataset. However, this method requires substantial computation. A better balance between efficiency and detection accuracy remains necessary. Tian et al. [9] proposed a cross-modality proposal-guided feature mining (CPFM) mechanism; it first predicts cross-modal proposal boxes based on fused features. These boxes are designed to enclose targets from both modalities. Using these proposals as guidance, it then applies deformable convolution to adaptively mine target features in each modality. Finally, it predicts target locations separately for both modalities. Yuan et al. [10] designed a translation–scale–rotation alignment (TSRA) module. This module first calculates positional, scale, and rotational deviations between RGB and IR feature maps. A modality selection (MS) strategy is then used to select the better-annotated modality as a reference. This, along with multi-task jittering (MJ) for improved alignment robustness, leads to final feature calibration. Liu et al. [11] employed deformable convolution guided by cross-modal offsets for spatial alignment. They also enforced semantic consistency through contrastive learning in a shared space. This approach effectively mitigated the challenges of weak cross-modal alignment.

Although the aforementioned methods have improved feature alignment performance at different levels, most of them still rely on a single modality as the alignment reference. This fixed reference modality selection strategy may fail to the dynamic variations in different scenarios, thereby limiting their potential application. Furthermore, using only a single modality as a reference makes it difficult to fully leverage the complementary information between visible and infrared modalities. In reality, significant cross-modal variations exist between infrared and visible images, creating a domain gap [12]. Directly predicting spatial offsets using a single reference modality may lead to mismatched feature of both modalities. Therefore, designing a more robust alignment mechanism to avoid reliance on a single reference modality is crucial under conditions of significant domain gap.

Furthermore, most current image object detection methods are based on convolutional neural networks (CNNs) [13,14,15] and Transformer [8,16,17,18]. CNN-based methods are constrained by their local receptive field characteristics, so their capability is often limited in capturing long-range dependencies within an image. Effectively capturing these long-range dependencies is important for accurately detecting small targets in remote sensing images. Although Transformers [19] demonstrate strong performance in capturing global context and long-range dependencies through self-attention mechanisms, their quadratic computational complexity and high memory requirements make it difficult to meet real-time demands on UAV platforms.

Recently, Mamba [20] has demonstrated outstanding performance in multimodal fusion due to its selective scanning mechanism and hardware-friendly computational strategies, with its efficient global modeling capability and balanced complexity. For example, DMM [21] adaptively merges features from visible and infrared images using modal disparity information to mitigate inter-modal conflicts. It then leverages Mamba’s ability to capture long-range dependencies, achieving robust fusion of cross-modal RGB and IR features. Moreover, MGMF [22] employs candidate regions from one modality to cover the corresponding intermediate-level features from another modality. Simultaneously, it extracts cross-modal guidance through regularization constraints. Then the cross-modal features are mapped to a shared hidden state for interaction, thereby reducing discrepancies between cross-modal features and enhancing information fusion. COMO [23] leverages high-level features that are less affected by misalignments to facilitate interaction and transmit complementary information between modalities, addressing positional shifts caused by varying camera angles and capture times. It further enhances information interaction and fusion by using Mamba’s global and local scanning mechanisms to capture features containing both global sequence information and local correlations. Fusion-Mamba [24] maps cross-modal features into a hidden state space for interaction, thereby reducing discrepancies between them. It designs a State Space Channel Swapping (SSCS) module to facilitate shallow feature fusion while also designing a dual state space fusion module for deep fusion. This design enhances the representational consistency of the fused features. However, these approaches commonly struggle with the trade-off between detection effectiveness and real-time performance. Some models pursue higher detection accuracy by introducing complex module designs or multi-stage fusion mechanisms, resulting in low processing speed. Conversely, lightweight approaches may fall short in feature fusion and cross-modal alignment, limiting the performance ceiling for downstream tasks. Therefore, a multimodal object detection framework that balances detection performance and inference efficiency has significant theoretical and practical value.

To address the above issues, we propose the Mutual-Spectrum Perception Deformable Fusion Mamba (MSDF-Mamba) Network, which consists of two key modules: the Mutual-Spectrum Deformable Alignment (MSDA) module and the Selective Scan Fusion (SSF) module. The core challenge in cross-modal feature alignment lies in establishing semantic correspondences between the two modalities, but traditional approaches often directly operate raw features, overlooking the inherent information asymmetry between modalities and failing to fully exploit complementary cross-modal information. Therefore, we design the MSDA module to employ a bidirectional cross-attention mechanism so as to obtain in-depth information between the visible and infrared modalities. This mechanism allows each modality to actively query complementary information from the other, generating a set of enhanced features rich in cross-modal contextual information. The MSDA module can dynamically learn and generate an optimal shared reference feature directly from the data itself, rather than relying on a single modality—which may be an inherent contain defect—as the reference. Our method fundamentally avoids offset estimation bias caused by poor reference modality quality. Subsequently, guided by the generated shared reference features, the spatial offset required for deformable convolution is predicted. This design enables the convolution kernel to adaptively adjust its sampling position, achieving pixel-level spatial correction, and finally, the aligned dual-modal features are obtained.

Based on these aligned features, the SSF module further provides a unified hidden state space. It maps both infrared and visible modalities into this space to achieve unified semantic-level encoding, enabling full interaction between the two modal features in the same semantic dimension. The SSF module effectively mitigates fusion bias caused by representational inconsistencies between modalities. Moreover, this module simplifies the internal structure of the state space model and reduces redundant state dimensions and complex connectivity patterns. While preserving the core mechanism of selective state space, it significantly lowers computational complexity. This design enables the model to dynamically regulate cross-modal information interaction and maintain long-range dependency modeling capabilities while improving computational efficiency.

In summary, this paper contributes the following:

- We propose a novel multimodal object detection framework based on the Mamba architecture, which solves two problems specific to visible–infrared images’ object detection tasks: positional misalignment and the imbalance between effectiveness and computational complexity.

- We design the Mutual Spectrum Deformable Alignment (MSDA) module, which acquires complementary features through bidirectional cross-attention and generates a shared reference for predicting offsets. Based on offsets, deformable convolutions are used to explicitly align features, thereby effectively overcoming modal misalignment.

- We also design a Selective Scan Fusion (SSF) module that maps features to a shared hidden state space via a selective scanning mechanism. This module achieves efficient cross-modal feature interaction while maintaining linear computational complexity.

- We validate the effectiveness of our proposed framework on two widely used remote sensing datasets, DroneVehicle and DVTOD. Our method achieves state-of-the-art performance with 82.5% mAP on DroneVehicle and 86.4% mAP on DVTOD, significantly outperforming existing fusion detection methods in both accuracy and efficiency.

2. Materials

State space models (SSMs) are emerging as a powerful alternative to Transformer architectures due to their exceptional long-sequence modeling capabilities and linear computational complexity. SSMs process one-dimensional input sequences through an intermediate hidden state to produce output , where N denotes the dimension of the hidden layer. The internal state of the models is represented as a set of linear equations:

where is the state transition matrix, controlling the evolution of the state vector and influencing how the state updates over time. and are projection parameter matrices. is the skip connection.

Since SSMs are inherently continuous-time systems, they cannot be directly applied to deep learning architectures and must undergo discretization. In the context of computer vision, this means converting continuous state-space models into discrete forms to ensure compatibility with visual models used for tasks such as image classification, object detection, and image segmentation. A common approach is to use methods similar to the zero-order hold principle [25]. Given the time scale parameter , the formula for converting continuous parameters and to their discrete counterparts and is as follows:

Therefore, Equations (1) and (2) can be written as

where D is considered a residual connection and is typically omitted in the equation.

Traditional SSMs have effectiveness in handling discrete sequences, but fixed parameters limit their application. The selective state space model (S6), known as Mamba, replaces the static parameters by dynamically inferring matrices , , and from the input, thereby granting the ability to adaptively adjust based on context [25]. In computer vision, Mamba struggles to directly process two-dimensional structured data like images because it was originally designed for one-dimensional sequence modeling and lack of explicit modeling capabilities for spatial relationships. To overcome this limitation, VMamba [26] proposes the 2D Selective Scanning (SS2D) method. This strategy unfolds images along four directions to turn independent sequences to extract multi-directional features. These features are then fused to reconstruct a two-dimensional spatial representation. SS2D method enables each unit in the sequence to interact fully with scanned elements by compressing hidden states, thereby capturing global context within images. It achieves success in effective global context modeling while maintaining linear computational complexity. This method delivers comprehensive and efficient feature fusion without sacrificing efficiency. Leveraging its capability for efficient modeling of two-dimensional spatial features in images, the SS2D method has achieved great success in the field of remote sensing image object detection [21,22,23,24].

3. Methods

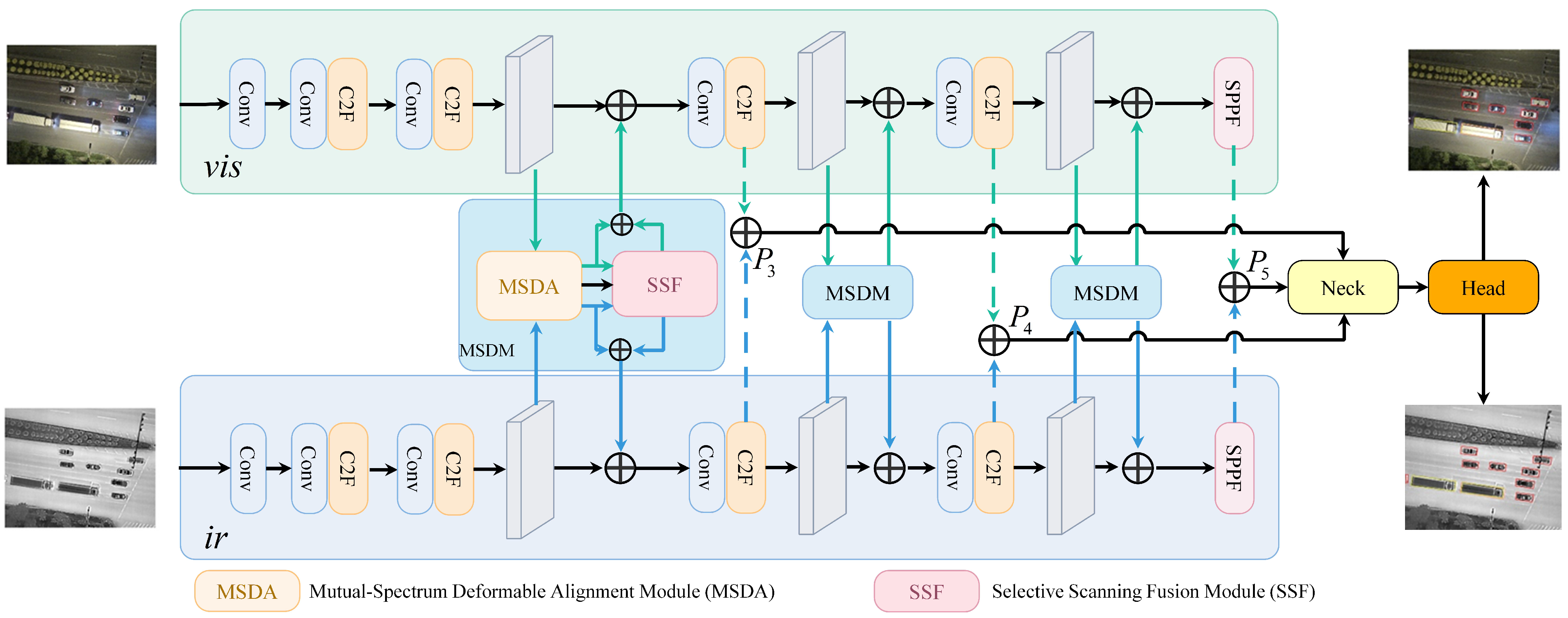

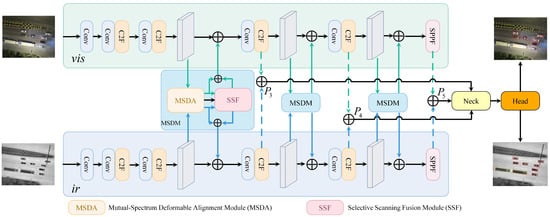

This section introduces the network architecture (as shown in Figure 2) of MSDF-Mamba. The framework consists of three core components: a dual-stream feature extraction backbone network based on YOLOv8, the MSDA module, and the SSF module. We first outline the methodological framework in Section 3.1, elaborate on the MSDA module in Section 3.2, and introduce the SSF module and its fusion process in Section 3.3. Finally, Section 3.4 presents the detection head and discusses the design of the loss function.

Figure 2.

Overall architecture of our proposed MSDF-Mamba network, which includes an MSDA module that employs cross-attention mechanisms for feature enhancement. The enhanced features serve as reference modalities for predicting offsets, with deformable convolutions ultimately achieving alignment. The aligned features are inputted into an SSF module, which projects them onto the hidden state space to achieve comprehensive fusion of the two modal features. The final detection result is output through the neck and head.

3.1. Overall Framework of MSDF-Mamba

Our baseline model adopts a dual-stream architecture to accommodate input data from different modalities. Specifically, it employs two structurally consistent YOLOv8 [27] backbone networks (CSPDarkNet-S) to extract features from visible and infrared images, respectively. Subsequently, the output features from the last three stages of both branches are fused through element-wise addition, yielding the fused P3, P4, and P5 feature layers. These fused features are fed into the YOLOv8 neck and detection head to produce final detection results. Based on above basic framework, we propose a novel object detection framework, MSDF-Mamba. To address misalignment issues, a Mutual-Spectrum Perception module is designed first. This module employs a bidirectional cross-attention mechanism to achieve complementary enhancement between visible and infrared features. These enhanced features are then concatenated as a reference modality to predict offset values. Subsequently, deformable convolutions are applied to align the features. To further enhance feature interaction and fusion, the SSF module is proposed. It leverages cross-modal interactions within the hidden state space to reduce modal differences and strengthen complementarity. Finally, the outputs from the last three stages of the YOLOv8 network are summed to obtain the fused features named P3, P4, and P5, respectively. The P3, P4, and P5 serve as inputs to the YOLOv8 neck and head, predicting the final detection results.

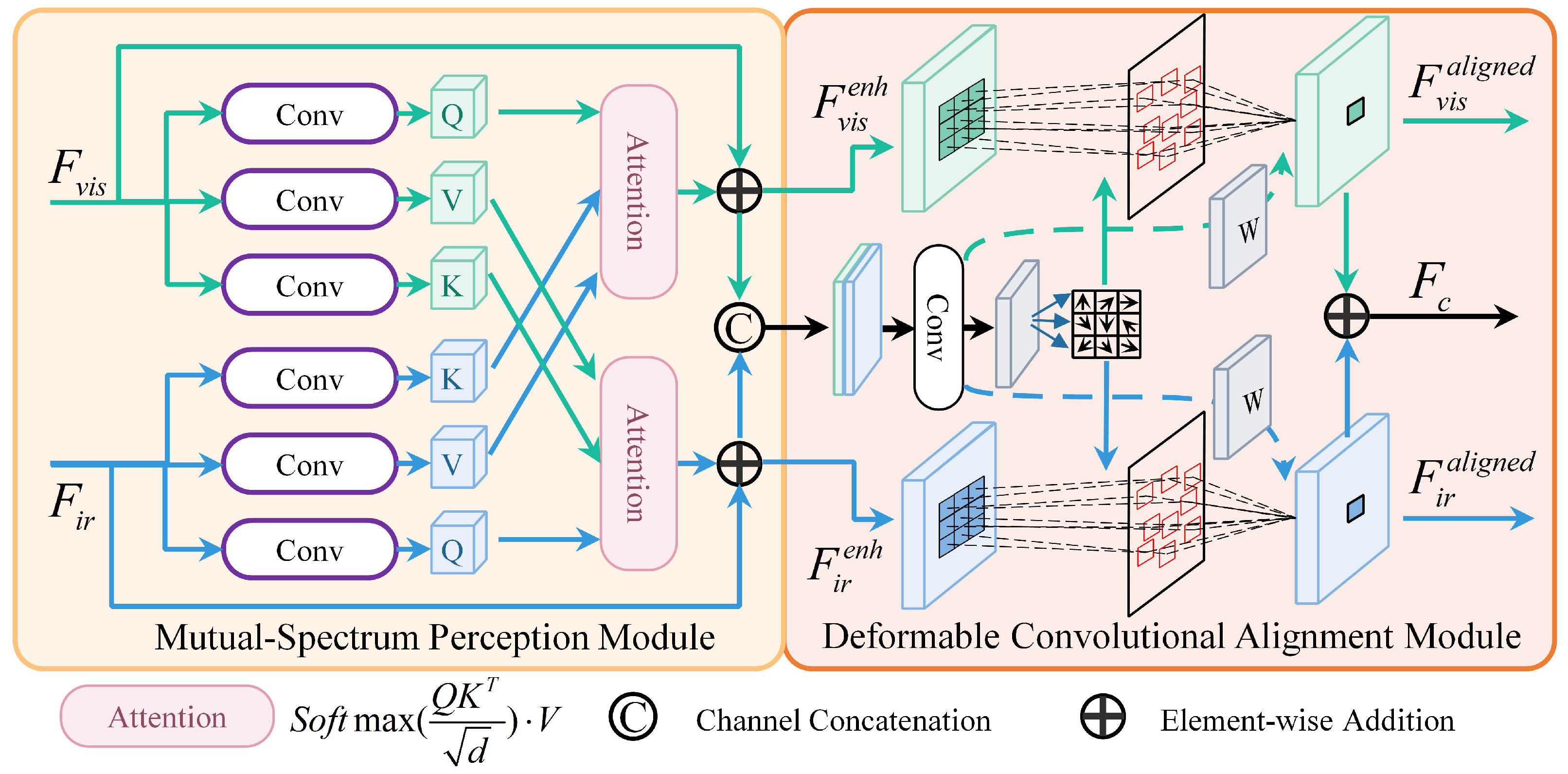

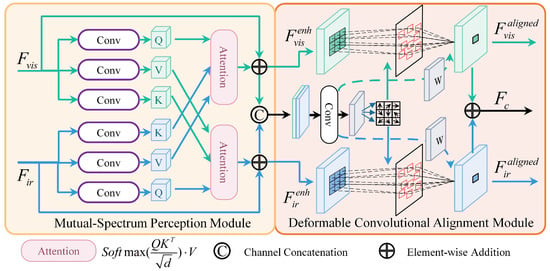

3.2. MSDA Module

The core challenge of cross-modal feature alignment lies in establishing precise semantic correspondences between the two modalities. Traditional approaches often directly process raw features, overlooking the inherent information asymmetry and complementarity between modalities. To address this problem, we design a mutual spectral perception (MSP) module to achieve interaction and collaborative enhancement through a bidirectional cross-attention mechanism. Here, “spectral” refers to the characteristic feature spaces of each modality. “Mutual spectral perception” means that, through a bidirectional attention mechanism, the model can actively explore and fuse complementary information within this multi-scale feature space to achieve feature enhancement. However, only enhanced features are insufficient for precise spatial alignment. Therefore, we further utilize the enhanced features as a reference modality through deformable convolutions [28] to achieve end-to-end feature calibration. Combining the explicit geometric transformation capability of deformable convolutions with the feature enhancement capability of MSP mechanism, the MSDA module learns its spatial transformation parameters with high semantic consistency. The whole design is illustrated by Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Visualization of the MSDA module. This module achieves deep information interaction and collaborative enhancement between visible and infrared modalities through a bidirectional cross-attention mechanism. It then utilizes the enhanced features as reference modalities to predict the offset required for deformable convolution and finally employs deformable convolution to achieve feature alignment.

Given visible features and infrared features extracted from the backbone network, an MSP module is first designed to process them through a parallel and symmetric dual-path architecture. The mechanism of MSP module is as follows:

(1) In the infrared-guided visible feature enhancement path, visible features can focus and fuse the prominent thermal target information and clear boundaries within infrared features, enhancing robustness against challenges such as occlusion and illumination variations. Based on the attention mechanism of the Transformer model [19], visible features serve as the query source: , and infrared features serve as the information sources: , . The computational process is as follows:

where is the scaling parameter related to the dimension of K. By scaling the dot product of Q and K, it ensures the stability of the softmax output.

(2) In the visible-guided infrared feature enhancement pathway, infrared features query the relevant contextual information from visible features actively. The contextual information is then integrated into the infrared features through weighted aggregation to compensate their detailed representation limitation. Specifically, infrared features serve as the query source: , and visible features serve as the information sources: , . The computational process is as follows:

The MSF module outputs the complementary enhanced features and . Compared to the original features, these enhanced features not only retain original specificity but also integrate the complementary information of each other modality.

The enhanced features are then fed into the offset generation network . This network takes the channel-concatenated enhanced features as input and predicts spatial offsets through a lightweight convolutional network:

where represent the predicted offset and modulation scalar, respectively. The offset is subsequently employed to drive the deformable convolution, which is the core operation for achieving explicit spatial alignment. Along the visible modality alignment path, the offset are utilized to perform a deformable convolution operation on the enhanced feature , thereby yielding the spatially transformed aligned visible feature:

Similarly, by performing a deformable convolution operation on with the shared , we obtain the aligned infrared feature:

Specifically, given the center sampling value in the enhanced features and , each counterpart in aligned features can be obtained as follows:

where K, and denote the number of kernel weights, the kth fixed offset, and the kth kernel weight, respectively. represents the learned offset for the kth position. For example, defines the regular grid for a 3 × 3 kernel when K = 9. is the modulation scalar corresponding to sampling point , which dynamically adjusts the contribution of each . is usually a decimal. In this paper, we employ bilinear interpolation to address this issue. Finally, the aligned features from both paths are obtained by element-wise addition.

The alignment features make further feature interaction and enhancement possible during the subsequent fusion process.

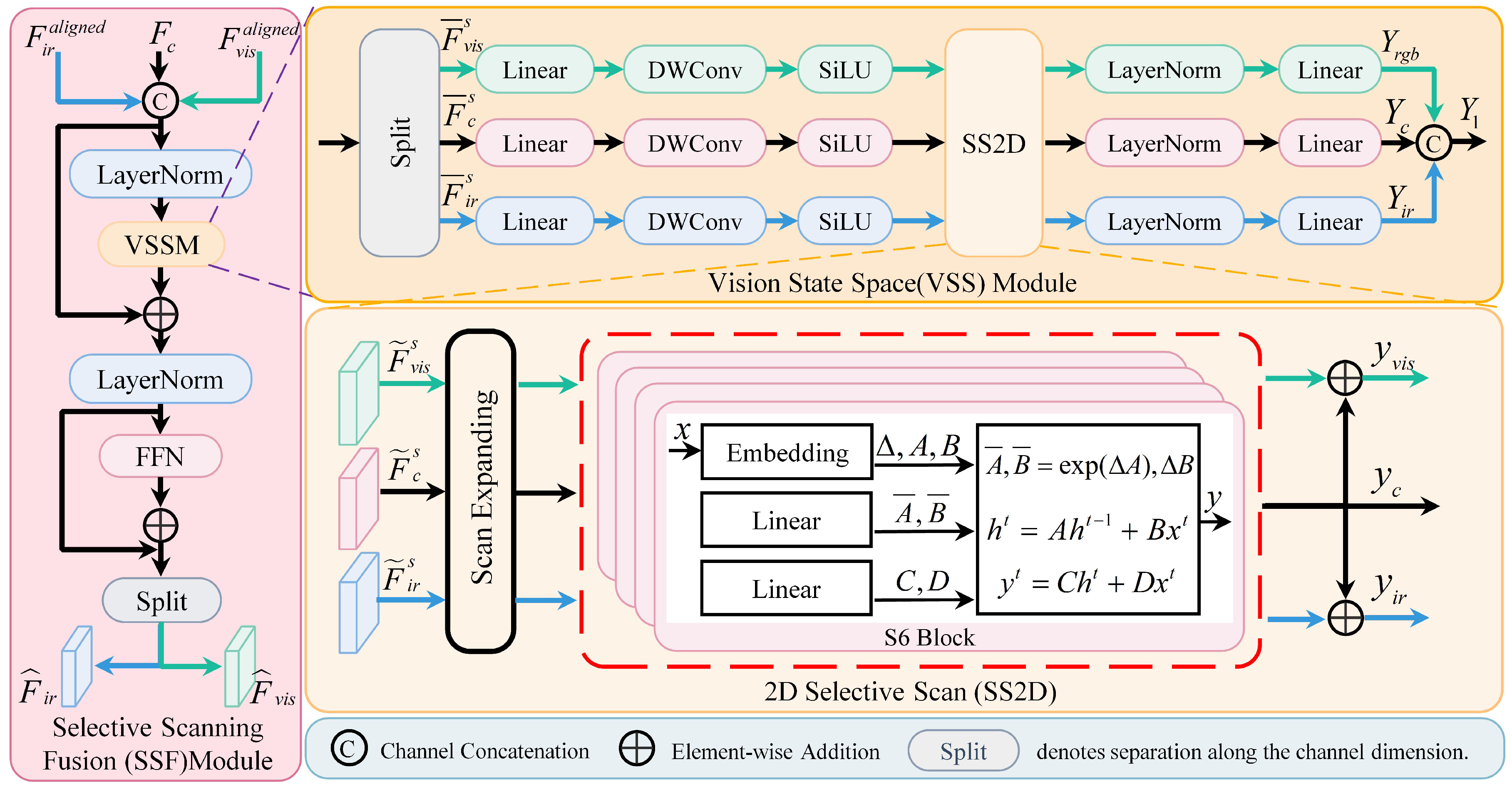

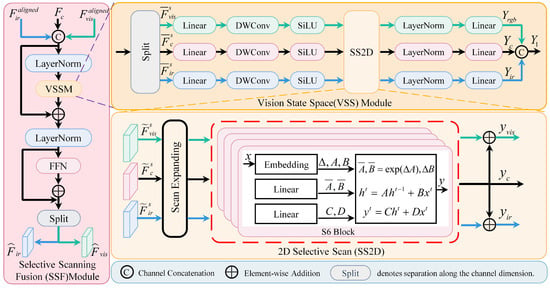

3.3. SSF Module

After obtaining spatially aligned visible features , infrared features and fused features from MSDA module, a robust mechanism is required to deeply integrate multimodal information. So, we designed the SSF module. Figure 4 illustrates the fusion process in it.

Figure 4.

Visualization of the SSF module. This module simplifies the internal structure of state space models and eliminates redundant complex connections to retain only the core mechanisms of selective state space.

The fusion process of the SSF module is as follows: First, input features , and are concatenated along the channel dimension to form a composite feature.

Subsequently, this composite feature undergoes a LayerNorm layer before being fed into the Vision State Space (VSS) module for training stabilization. The entire processing sequence includes a residual connection to ensure training stability and gradient flow, calculated as follows:

The fusion mechanism within the VSS module determines its efficiency. Specifically, the input feature is split along the channel dimension into three independent branches again, according to visible, infrared, and fusion modalities:

The features of each branch first undergo channel-dimensional transformation and information compression through a linear projection layer. Then, deep convolutions are applied to the projected features. Finally, nonlinear transformations are carried out via the SiLU activation function. The above process can be expressed as

where Linear(·) represents projection operations using linear transformations, DWConv(·) are deep convolution operations, and SiLU(·) means the SiLU activation function. The results and , respectively, represent the visible modality, infrared modality, and fusion modality inputs for the latter SS2D module. All input modalities are fed into a shared SS2D module, yielding outputs , and .

In the SS2D module, input features , and are first processed through linear layers to generate state matrices , . Meanwhile, the parameter matrices are initialized. After discretization, these matrixs map their respective modal features to the hidden state space h. The mapping process can be represented as follows:

where , , , , , are the discretization form of matrices and . It is worth noting that, following the method in [29], the parameter matrices , , and are added to form the output matrix , which is used to reconstruct the hidden state. The specific implementation is as follows:

Thus, after decoding the hidden states of the three modalities, selective scanning outputs , , and are generated.

Additionally, the further fusion features are composed of the selective scanning outputs, i.e.,

Finally, after layer normalization and linear projection, the concatenated outputs are

where Concat(·) means channel concatenation.

Following above processing, a feedforward neural network split features into two parts: and . The specific implementation process is as follows:

where FFN(·) is the feedforward neural network.

The enhanced features and are used to generate the fused feature . This fused feature then enters the neck network and head network of the YOLOv8 architecture and finally produces the prediction results. The neck network and head network utilize the original YOLOv8 architecture.

3.4. Loss Function

For the loss function, we utilize the YOLOv8 detection loss function including three components: classification loss (evaluating the model’s prediction accuracy for object categories), bounding box loss (primarily measuring the positional and shape discrepancies between predicted and ground truth bounding boxes), and its coordinate optimization loss . The overall loss is

where , , and represent the weights of loss. In this paper, we set , and to 7.5, 0.5, and 1.5, respectively.

4. Results

In this section, we first introduce the datasets, evaluation metrics, and the experimental setup. Then, we compare our method with previous state-of-the-art approaches. Finally, the ablation experiment shows the effectiveness of MSDF-Mamba.

4.1. Datasets and Evaluation Metrics

4.1.1. DroneVehicle Dataset

The DroneVehicle dataset [30] is a large-scale remote sensing dataset collected by drones, comprising 28,439 pairs of visible and infrared images. The dataset covers diverse real-world scenarios including urban roads, rural areas, residential zones, and parking lots. Images are categorized into three types according to lighting conditions: daytime, nighttime, and extremely dark nighttime. Each image is annotated with five types of oriented bounding boxes (cars, trucks, buses, vans, and freight cars), totaling 953,087 instances. The dataset is formally partitioned into 17,990 training pairs, 1469 validation pairs, and 8980 test pairs. We use ground truth data from infrared images as training labels, as object annotation is more comprehensive in infrared mode.

4.1.2. DVTOD Dataset

The DVTOD [31] dataset is a benchmark dataset specifically constructed for visible–infrared misaligned object detection tasks in UAV scenarios. This dataset contains 2179 pairs of visible and infrared image pairs, including 4358 images with 6142 annotated bounding boxes. It covers three target types: person, car, and bicycle. The DVTOD dataset covers diverse challenging real-world scenarios, including adverse weather (rain, snow, fog), complex lighting conditions (extreme exposure, daytime, nighttime, and dark environments), and occlusions caused by special materials (e.g., wood, opaque objects and glass). Additionally, the scene design incorporates mixed conditions, e.g., target occlusion combined with low light. This make its scenarios consistent with real-world conditions. Following the training–test partition principle recommended by Ref. [31], we selected 1606 image pairs for training and 573 pairs for testing. All images were uniformly resized to 640 × 640 pixel size.

4.1.3. Evaluation Metrics

We evaluate our model’s performance using a set of metrics, including precision (P), recall (R), average precision (AP), and mAP@0.5 (mAP@0.5 indicates an IoU threshold of 0.5) as the comprehensive metric. The specific operation formulas are as follows:

where n refers to the distinct classes.

4.2. Implementation Details

The experiments are conducted on a computer with an Intel i9-13900HX CPU and an NVIDIA Geforce RTX 4090 GPU. The code environment is based on CUDA 12.1 and PyTorch 2.3.0. During training, we use a dual-stream feature extraction network initialized with pre-trained weights. The weight decay is set to 0.0005, and the initial learning rate is 0.01. The input image size is set to 640 × 640. Since the infrared labels contain more object annotations than the visible in dark environments, we use the infrared modal labels as the ground truth labels. For specific configuration details, see Table 1.

Table 1.

Model parameter settings.

4.3. Comparison Experiments

4.3.1. Comparison on DroneVehicle Dataset

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed method, we first compare it with state-of-the-art single-modal detection methods, including: RetinaNet [32], R3Det [33], S2ANet [34], Faster R-CNN [35], RoITransformer [36], and YOLOv8(OBB) [27]. The test results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of our method with other single-modality methods on the DroneVehicle dataset. The best results are in red and the second-best results are in blue.

The AP values of different single-modal detection methods and our proposed model across various categories are shown in Table 2. The table data shows YOLOv8 achieves the highest detection accuracy among single-modal detection methods, due to its carefully designed multi-scale feature extraction network. It achieves an mAP@0.5 of 74.5% for detecting RGB images and 78.6% for detecting infrared images. In contrast, our model achieves a higher mAP@0.5, exceeding YOLOv8 (OBB) by 3.9%. Additionally, AP values increase across all categories. The most significant improvements are observed in three categories—truck, bus and van, with gains of 9.4%, 3.3%, and 3.3%, respectively. The enhancement in detection accuracy demonstrates the effectiveness of our method for vehicle detection in remote sensing images.

The experimental results presented in Table 3 are a comparative analysis between MSDF-Mamba and other multimodal methods, including UA-CMDet [30], Halfway Fusion [37], CIAN [38], AR-CNN [7], MBNet [39], TSFADet [10], C2Former [8], DMM [21], OAFA [40] and RemoteDet-Mamba [41]. Compared with Table 2, most multimodal fusion detection methods outperform single-modal approaches significantly, demonstrating the advantage of multimodal data over single-modal data. Among these multimodal methods, RemoteDet-Mamba based on Mamba framework achieves the highest detection accuracy. It achieves an mAP@0.5 of 81.8% on the test set. Next are the DMM and OAFA methods, both achieving an mAP@0.5 of 79.4%. However, our MSDF-Mamba method achieves the highest mAP@0.5 on the test set at 82.5%, surpassing the second-place method by 0.7% and outperforming the baseline models like DMM by 3.1%. Table 3 shows that our method has significant advantages in detecting vehicle targets, such as car, truck, and bus, achieving the highest detection accuracy for all three categories. Detection capabilities for less frequent categories, such as freight car, are also enhanced to achieve near-optimal detection accuracy. This improvement likely stems from the proposed MSDA module, which enables precise feature alignment to obtain more accurate target features after fusion.

Table 3.

Comparison of our method with multimodal methods on the DroneVehicle dataset. The best results are in red and the second-best results are in blue.

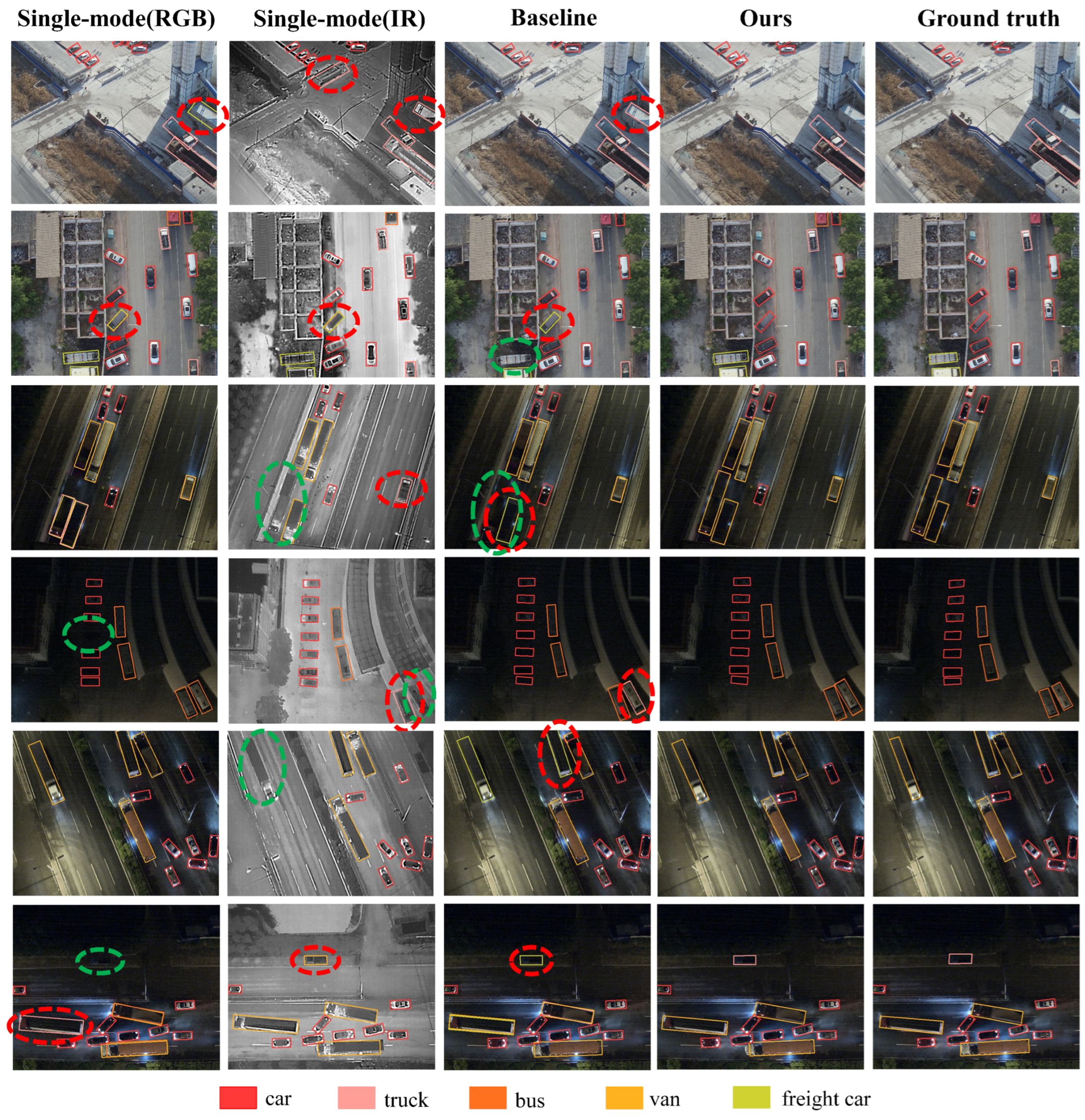

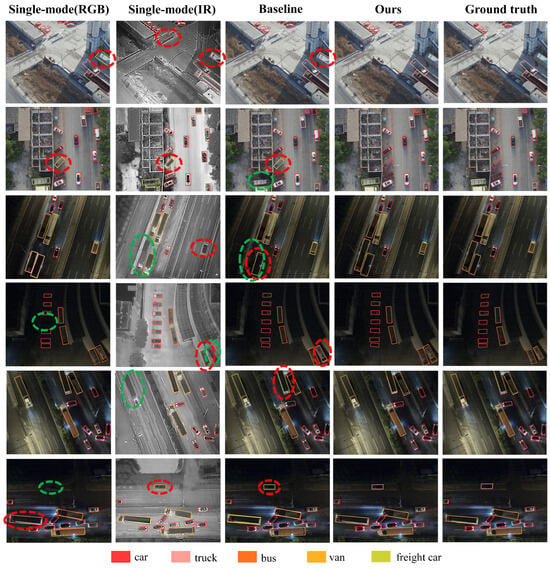

Our detection model is based on an enhanced version of YOLOv8. Therefore, we choose YOLOv8 as the baseline model and compare its detection outputs with our MSDF-Mamba through visualization. We select six representative images from the DroneVehicle dataset, each with different scenes, camera angles, and lighting conditions. The detection results are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Visualization of detection results on the DroneVehicle dataset. Red dashed circles indicate false positives, while green dashed circles denote false negatives. Single-mode (RGB) and single-mode (IR) represent YOLOv8’s detection results on visible and infrared images, respectively. Baseline represents YOLOv8’s detection results using bimodal images. Ground truth shows the true labels, here using infrared labels.

The visual detection results of our method and baseline models are shown in Figure 5. From the first to the last column, the visualization results are as follows: single-modal (RGB), single-modal (IR), baseline, ours, and ground truth. The false targets are marked with red circles, while the missed targets are marked with green circles. It can be observed that our method successfully detects true targets even when their positions are misaligned. In contrast, both the single-modal and baseline methods make classification and localization mistakes or fail to detect targets, particularly for those occluded and few-instance targets. It can be inferred that the weak misalignment confuses other multimodal methods. In contrast, our method captures aligned and reliable features, thereby enhancing its object detection performance.

4.3.2. Comparison on DVTOD Dataset

To demonstrate our method’s generalization capability, we conduct comparsion experiments not only on the DroneVehicle dataset but also on another drone-captured visible–infrared benchmark dataset, DVTOD. Our comparison includes YOLO series detection algorithms, YOLOv3 [42], YOLOv5 [43], YOLOv6 [44], YOLOv7 [45], YOLOv8 [27], YOLOv10 [46], along with four bimodal detection methods, CMA-Det [31], YOLOv5 + Add, YOLOv5 + CMX [47] and CFT [48]. Among these, YOLOv5 + Add refers to a simple feature addition fusion method that directly sums visible and infrared modality features without additional processing. The specific results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparison of our method with YOLO series and other detections methods on the DVTOD dataset. The best results are in red and the second-best results are in blue.

As shown in Table 4, all YOLO series methods demonstrate significantly superior performance in the infrared modality compared to the visible modality. This indicates the inherent stability advantages of infrared data in challenging scenarios such as lighting variations, occlusions and camouflage. The improvement is particularly significant for detecting “Person” and “Bicycle” categories. For example, YOLOv3’s AP for the person category increased dramatically from 25.1% to 87.1%. The other four dual-modal methods also performed well as expected. Among them, the baseline model CMA-Det achieved an mAP@0.5 of 85.0%. Nevertheless, our method achieved an mAP@0.5 of 86.4% on the DVTOD dataset, significantly outperforming other comparative methods. Specifically, our method outperformed the current best fusion detection method CMA-Det (85.0%) by 1.4 percentage points, compared to the CFT method (82.7%), YOLOv5 + CMX (81.6%), and YOLOv5 + Add (79.2%). It achieved improvements of 3.7, 4.8, and 7.2 percentage points respectively. In terms of detection accuracy across categories, our method achieved 89.8% for the person category, comparable to CMA-Det’s 90.3%. For the car category, our method attained 83.3% detection accuracy, surpassing CMA-Det’s 81.6% by 1.7 percentage points. It also achieved 86.2% detection accuracy for the bicycle category, improving by 3.1 percentage points over CMA-Det’s 83.1%. These test results demonstrate the effectiveness and superiority of our fusion strategy.

4.3.3. Comparisons of Computational Costs and Speed

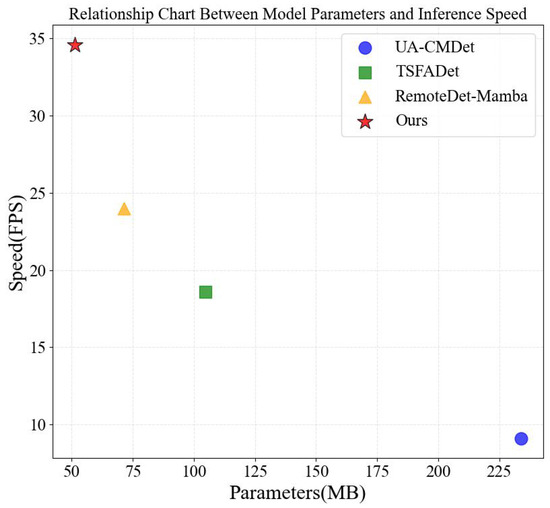

Figure 6 shows a comparison of our method with several others in terms of computational parameters and speed. The testing is conducted on the DroneVehicle dataset. For a fair comparison, the test images size for all detection models are set to 640 × 640. Our proposed MSDF-Mamba achieves the best detection performance among all compared methods while operating at 34.6 FPS with a model size of only 51.34 MB. Notably, it reduces the number of parameters by approximately 40% compared to the DMM baseline (87.97 MB).This achieves a balance between effectiveness and computational complexity.

Figure 6.

Relationship chart between model parameters and inference speed across different methods. Our method achieves the highest FPS while maintaining the lowest parameter size, significantly outperforming other methods.

4.4. Ablation Experiments

To validate the effectiveness of our method, three sets of ablation experiments are conducted to examine the impact of each individual module designed in Section 3. The first experiment evaluated the MSDA module; the second experiment assessed the isolated effect of the SSF module; and the third experiment systematically examined the collective contribution of all improvements. The tests are conducted on the DroneVehicle dataset. The results of these three ablation experiments are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Results of the ablation experiments.

Table 5 demonstrates the performance of different modules when operating independently. The detailed descriptions are as follows. The YOLOv8 dual-stream feature extraction network serves as the baseline for ablation experiments. We employ CSPDarkNet-S as the backbone and utilized mAP@0.5 as the metric for model performance evaluation. To ensure experimental fairness and accuracy, all experimental data and parameters have the same settings.

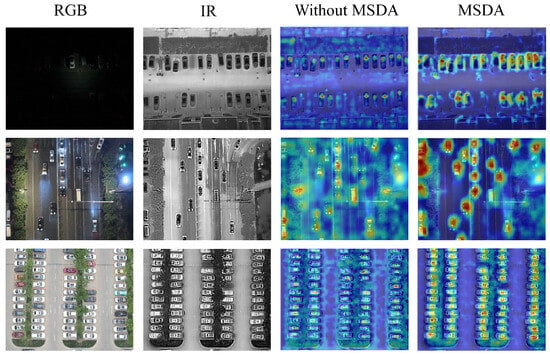

We first analyzed the impact of MSDA module, which employs a bidirectional cross-attention mechanism to achieve deep interaction between two modalities. As shown in Table 5, the baseline mothod achieves an mAP@0.5 of 78.9% while the baseline + MSDA method increases the mAP@0.5 by 1.9% to 80.8%. To visualize how the MSDA module enables more precise feature region localization, we utilized Grad-CAM [49] to generate heatmaps of intermediate features with and without the MSDA module, as shown in Figure 7. To clearly present the results, we overlay the heatmap onto the original image. The results clearly show that after adding the MSDA module, both the number and intensity of activation regions increase significantly, especially in the central area of target. By contrast, feature responses in non-target regions or misaligned areas are significantly suppressed. These experiment results illustrate that the baseline + MSDA method focuses its attention more intently on the target region, leading to more accurate detection.

Figure 7.

Visualization results of the intermediate feature heatmap (here, the heatmap is overlayed on the original image). The first two columns show the visible and infrared raw images. The third column displays the visualization results from the baseline model without the MSDA module. The last column presents the visualization results from the model with the MSDA module. Visualization results under different lighting conditions are shown here, demonstrating effective feature alignment across all-weather environments.

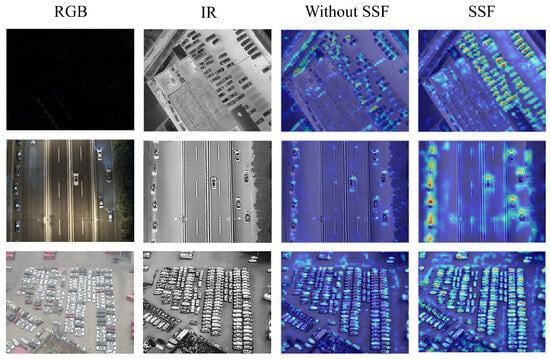

We then validated the necessity of the SSF module within the fusion network architecture. It is well known that mismatching in visible and infrared images ruins good modeling of cross-modal features. When adding SSF module, the baseline + SSF method yields a significant improvement of +2.2% mAP@0.5, demonstrating the effectiveness of SSF model. To further investigate its effectiveness, a comparison of intermediate feature heatmaps is shown in Figure 8. With the SSF module, it is clear that the heatmaps show a higher degree of focus on target objects while effectively suppressing background noise.

Figure 8.

Visualization results of the intermediate feature heatmap (here, the heatmap is overlayed on the original image). The first two columns show the original visible and infrared images. The third column displays the visualization results from the baseline model without the SSF module. The last column presents the visualization results from the model with the SSF module. Visualizations under different lighting conditions are shown here, demonstrating effective feature alignment across all-weather environments.

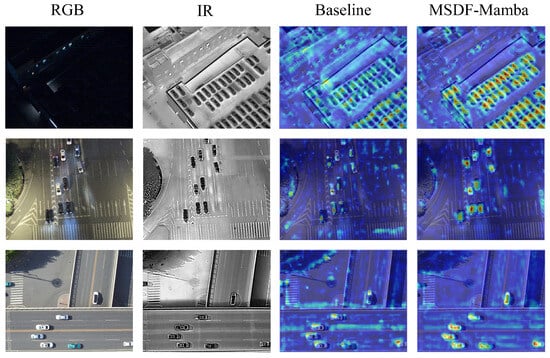

Lastly, we integrated both the MSDA module and SSF module to demonstrate the effectiveness of our method. Our method achieves the best detection performance with an mAP of 82.5%, gaining a 3.6% improvement over the baseline. This demonstrates the effectiveness of our method. The specific visualization results are shown in Figure 9. From the figure, it can be seen that compared with the original baseline model, our model pays more attention to the target of interest, indicating that our method can better capture useful features and is effective.

Figure 9.

Visualization results of the intermediate feature heatmap (here, the heatmap is overlayed on the original image). The first two columns show the original visible and infrared images. The third column presents the baseline model visualization results. The last column presents our MSDF-Mamba visualization results. Visualizations under different lighting conditions are shown here, demonstrating effective feature alignment across all-weather environments.

5. Discussion

5.1. Rationality Analysis of the SSF Module

The original vision state space module is designed for processing single-modal input sequences and cannot handle dual modalities. To address this issue, this study proposes an innovative architecture capable of effectively fusing dual-modal information. Specifically, after the MSDA module completes feature alignment, we first perform a preliminary fusion of the aligned infrared and visible features, generating a fused feature that contains cross-modal interaction information. Subsequently, the preliminary fused feature and the two aligned single-modal features are concatenated along the channel dimension and jointly fed into the SSF module for deep processing. In the SSF module, we designed a unique three-branch parallel processing pipeline: the aligned infrared features, the aligned visible features, and the preliminary fused features are each independently processed through a selective scanning procedure. This design enables each feature to fully leverage the global receptive field of the state space model for sequence modeling, allowing them to learn long-range dependencies within their respective modalities and within the fused features without mutual interference. After the scanning process, we obtain three sets of deeply optimized feature representations. Finally, we perform additive fusion of the processed fused features with the processed infrared and visible modal features. This design is driven by two key motivations: first, the infrared and visible modalities retain their modality-specific information through independent processing paths, avoiding feature dilution caused by premature fusion. Second, through secondary fusion, each modality can selectively absorb complementary information from the other modality, enhancing the effectiveness of fusion. Ablation experiments, as presented in Table 5, further validate the rationality of this design. Compared with the original model, the mAP increases from 78.9% to 81.5% after the integration of the designed SSF module, which confirms the effectiveness of the SSF module.

5.2. Limitations of MSDF-Mamba

Although the fusion module SSF maintains linear computational complexity through its selective scanning mechanism, the bidirectional cross-attention mechanism adopted in the feature alignment module MSDA introduces quadratic complexity, which may become a bottleneck for computational efficiency. Experimental results indicate that after incorporating the MSDA module, the model’s FPS drops from a baseline of 337.05 to 68.15, while the parameters increases from 11.70 MB to 38.36 MB. To further investigate the cause of the efficiency decline, we perform a statistical analysis of the parameters across different modules, as detailed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Comparison of module parameters.

As shown in Table 6, “Baseline” denotes the number of additional parameters introduced by the baseline model with only addition-based fusion. As the addition operation itself introduces no new parameters, this number is zero. “MSDA” represents the number of additional parameters introduced by integrating the MSDA module independently. Specifically, the combined number of parameters in the three MSDA modules (named Stage 1/2/3 according to their processing stages) reaches 21.87 M, accounting for 57% of the total parameters. This indicates that the quadratic complexity attention mechanism in the MSDA module is a direct cause leading to the decline in inference speed. In particular, as the network deepens, the input channels of the MSDA module increase from 128 to 512, resulting in a significant growth in the computational overhead of its internal attention matrices, which further exacerbates the computational burden.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we propose a novel multimodal UAV object detection framework named Mutual Spectral Perception Deformable Fusion Mamba (MSDF-Mamba). Based on YOLOv8 and Mamba, this framework incorporates two innovative modules. First, the MSDA module employs a bidirectional cross-attention mechanism to achieve deep mutual spectral perception between visible and infrared modalities, generating complementary enhanced features. These enhanced features are concatenated as a reference modality to generate offset values, which then drive deformable convolutions to achieve precise feature alignment. Second, the SSF module projects the aligned bi-modal features onto a unified hidden state space. Leveraging the Mamba model’s unique selective scanning mechanism, it enables efficient feature interaction and fusion under a global receptive field, fully exploiting cross-modal contextual information while maintaining linear computational complexity. Comparison experiments on the challenging DroneVehicle dataset demonstrate that our MSDF-Mamba outperforms state-of-the-art visible–infrared detection methods, achieving a 3.1% improvement in mAP while reducing model parameters by 40% compared to the baseline model. We also demonstrate our method’s generalization capability on the DVTOD dataset, achieving a 1.4% improvement in mAP. In summary, MSDF-Mamba achieves higher detection accuracy with fewer parameters, significantly enhancing the model’s perception capabilities in complex scenes. It achieves a balance between performance and efficiency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S. and J.H.; investigation, J.S., J.H., Q.L., Z.Z., G.W. and D.L.; methodology, J.S., J.H. and Z.Z.; software, J.S.; validation, J.S. and Q.L.; data curation, J.S.; visualization, J.S., Q.L. and J.H.; writing—original draft preparation, J.S. and Q.L.; writing—review and editing, J.H., Z.Z., Q.L., J.S., G.W. and D.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (No. 62303478).

Data Availability Statement

This study utilized publicly available datasets. The DroneVehicle dataset can be accessed at https://github.com/VisDrone/DroneVehicle (accessed on 24 October 2025). The DVTOD dataset is available at https://github.com/VDT-2048/DVTOD (accessed on 24 October 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express many thanks to all the anonymous reviewers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, Z.; Fu, R.; Liu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Du, J. Enhanced Cross-Domain Dim and Small Infrared Target Detection via Content-Decoupled Feature Alignment. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, R.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, D.; Du, J. Learning Nonlocal Quadrature Contrast for Detection and Recognition of Infrared Rotary-Wing UAV Targets in Complex Background. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, C.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Z. DVIF-Net: A Small-Target Detection Network for UAV Aerial Images Based on Visible and Infrared Fusion. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Hu, Q.; Zhou, B.; Yao, Y.; Lin, J.; Yang, K. CFMW: Cross-modality Fusion Mamba for Robust Object Detection under Adverse Weather. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 12066–12081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Rui, X.; Song, W. A UAV-Based Multi-Scenario RGB-Thermal Dataset and Fusion Model for Enhanced Forest Fire Detection. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, S. Image Registration Techniques: A Survey. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1712.07540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, X.; Song, Z.; Yang, X.; Lei, Z. Weakly Aligned Feature Fusion for Multimodal Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2025, 36, 4145–4159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Wei, X. C2Former: Calibrated and Complementary Transformer for RGB-Infrared Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5403712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Zhou, Z.; Huang, Y.; Li, G.; He, Z. Cross-Modality Proposal-Guided Feature Mining for Unregistered RGB-Thermal Pedestrian Detection. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2024, 26, 6449–6461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Wang, Y.; Wei, X. Translation, Scale and Rotation: Cross-Modal Alignment Meets RGB-Infrared Vehicle Detection. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV2022, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Avidan, S., Brostow, G., Cissé, M., Farinella, G.M., Hassner, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 509–525. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Luo, H.; Wang, Z.; Wei, Y.; Zuo, H.; Zhang, J. Cross-modal Offset-guided Dynamic Alignment and Fusion for Weakly Aligned UAV Object Detection. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.16737. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Liu, J.; Fan, X.; Liu, R. Unsupervised Misaligned Infrared and Visible Image Fusion via Cross-modality Image Generation and Registration. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.11876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Tang, L.; Xu, M.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, G. STDFusionNet: An infrared and visible image fusion network based on salient target detection. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, S.; Thachan, S.; Chen, J.; Qian, Y.; Lei, Z. Deconv R-CNN for Small Object Detection on Remote Sensing Images. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2018—2018 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Valencia, Spain, 22–27 July 2018; pp. 2483–2486. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Liao, X.; Yuan, J.; Yao, Y.; Li, Z. CDC-YOLOFusion: Leveraging Cross-Scale Dynamic Convolution Fusion for Visible-Infrared Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024, 10, 2080–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Huang, T.; Deng, L.; Dou, H.; Hong, D.; Vivone, G. Fusformer: A Transformer-Based Fusion Network for Hyperspectral Image Super-Resolution. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 6012305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhang, H.; Xu, H.; Liu, S.; Zhang, L.; Ni, L.M.; Shum, H.-Y. Mask DINO: Towards a Unified Transformer-Based Framework for Object Detection and Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 3041–3050. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Z.; Li, D.; Kuai, Y.; Chen, R.; Wen, G. Visible-Infrared Image Alignment for UAVs: Benchmark and New Baseline. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5613514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.; Liao, B.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Kiu, W.; Wang, X. Vision Mamba: Efficient Visual Representation Learning with Bidirectional State Space Model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.09417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Li, T.; Qiao, C.; Xie, D.; Wang, G. DMM: Disparity-Guided Multispectral Mamba for Oriented Object Detection in Remote Sensing. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5404913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, C.; Shi, C.; Liu, Y.; Lu, M. Mask-Guided Mamba Fusion for Drone-Based Visible-Infrared Vehicle Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5005712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Ma, X.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, Y. COMO: Cross-Mamba Interaction and Offset-Guided Fusion for Multimodal Object Detection. Inf. Fusion. 2025, 125, 103414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Zhu, H.; Lin, S.; Luo, X.; Shen, Y.; Guo, G. Fusion-Mamba for Cross-Modality Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2025, 27, 7392–7406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, A.; Dao, T. Mamba: Linear-time Sequence Modeling with Selective State Spaces. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.00752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, H.; Xie, L.; Wang, Y.; Ye, Q.; Jiao, J.; Liu, Y. Vmamba: Visual State Space Model. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 103031–103063. [Google Scholar]

- Jocher, G.; Chaurasia, A.; Qiu, J. Ultralytics YOLO 2023. Available online: https://docs.ultralytics.com/zh/models/yolov8/ (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Zhu, X.; Hu, H.; Lin, S.; Dai, J. Deformable ConvNets V2: More Deformable, Better Results. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 9300–9308. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhang, W.; Xiao, Y.; Li, C.; Tang, J. Reflectance-Guided Progressive Feature Alignment Network for All-Day UAV Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5404215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Cao, B.; Zhu, P.; Hu, Q. Drone-Based RGB-Infrared Cross-Modality Vehicle Detection Via Uncertainty-Aware Learning. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2022, 32, 6700–6713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Xue, X.; Wen, H.; Ji, Y.; Yan, Y.; Meng, Q. Misaligned Visible-Thermal Object Detection: A Drone-Based Benchmark and Baseline. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024, 9, 7449–7460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollar, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollar, P. R3Det: Refined Single-Stage Detector with Feature Refinement for Rotating Object. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2–9 February 2021; pp. 3163–3171. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Ding, J.; Li, J.; Xia, G. Align Deep Features for Oriented Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 5602511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2016, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Xue, N.; Long, Y.; Xia, G.; Lu, Q. Learning RoI Transformer for Oriented Object Detection in Aerial Images. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 2844–2853. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, S.; Metaxas, D. Multispectral Deep Neural Networks for Pedestrian Detection. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1611.02644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Yang, X.; Qiao, H.; Huang, K.; Hussain, A. Cross-modality Interactive Attention Network for Multispectral Pedestrian Detection. Inf. Fusion 2019, 50, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Chen, L.; Cao, X. Improving Multispectral Pedestrian Detection by Addressing Modality Imbalance Problems. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV2020, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Vedaldi, A., Bischof, H., Brox, T., Frahm, J.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 787–803. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Qi, J.; Liu, X.; Bin, K.; Fu, R.; Hu, X.; Zhong, P. Weakly Misalignment-Free Adaptive Feature Alignment for UAVs-Based Multimodal Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 26826–26835. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, K.; Wu, X.; Xu, L.; Wang, L. RemoteDet-Mamba: A Hybrid Mamba-CNN Network for Multi-modal Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.13532. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. Yolov3: An Incremental Improvement. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.02767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocher, G.; Stoken, A.; Borovec, J.; Changyu, L.; Hogan, A.; Diaconu, L.; Ingham, F.; Poznanski, J.; Fang, J.; Yu, L.; et al. ultralytics/yolov5: v3. 1-Bug Fixes and Performance Improvements. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/4154370 (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Li, C.; Li, L.; Jiang, H.; Weng, K.; Geng, Y.; Li, L.; Ke, Z.; Li, Q.; Cheng, M.; Nie, W.; et al. YOLOv6: A Single-Stage Object Detection Framework for Industrial Applications. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.02976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H. YOLOv7: Trainable Bag-of-Freebies Sets New State-of-the-Art for Real-Time Object Detectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 7464–7475. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J.; Ding, G. YOLOv10: Real-Time End-to-End Object Detection. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 107984–108011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Yang, K.; Hu, X.; Liu, R.; Stiefelhagen, R. CMX: Cross-Modal Fusion for RGB-X Semantic Segmentation with Transformers. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 14679–14694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Han, D.; Wang, Z. Cross-modality fusion transformer for multispectral object detection. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.00273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-CAM: Visual Explanations from Deep Networks via Gradient-Based Localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 618–626. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).