Highlights

What are the main findings?

- A unified FS-SNIC-ML workflow was developed, integrating multi-source optical fusion, semi-automatic sample generation, feature selection, and object-based machine-learning classification for burned forest mapping in mountainous regions.

- dNBR, dNDVI, and dEVI were jointly identified as the most discriminative variables, and the SNIC-supported RF classifier provided the most reliable burned-area mapping performance among the evaluated models.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- The workflow enables accurate burned-area extraction under persistent cloud cover and limited-sample conditions, producing spatially coherent results across multiple wildfire events in Dali Prefecture.

- Geographical detector revealed that temperature, precipitation, soil moisture, and their nonlinear interactions dominate the spatial patterns of wildfire hotspot density, supporting quantitative understanding of wildfire-driving mechanisms.

Abstract

Accurate mapping of burned forest areas in mountainous regions is essential for wildfire assessment and post-fire ecological management. This study develops an FS-SNIC-ML workflow that integrates multi-source optical fusion, semi-automatic sample generation, feature selection, and object-based machine-learning classification to support reliable burned-area mapping under complex terrain conditions. A pseudo-invariant feature (PIFS)-based fusion of Sentinel-2 and Landsat 8 imagery was employed to generate cloud-free, gap-free, and spectrally consistent pre- and post-fire reflectance datasets. Burned and unburned samples were constructed using a semi-automatic SAM–GLCM–PCA–Otsu procedure and county-level stratified sampling to ensure spatial representa-tiveness. Feature selection using LR, RF, and Boruta identified dNBR, dNDVI, and dEVI as the most discriminative variables. Within the SNIC-supported GEOBIA framework, four classifiers were evaluated; RF performed best, achieving overall accuracies of 92.02% for burned areas and 94.04% for unburned areas, outperforming SVM, CART, and KNN. K-means clustering of dNBR revealed spatial variation in fire conditions, while geographical detector analysis showed that NDVI, temperature, soil moisture, and their pairwise interactions were the dominant drivers of wildfire hotspot density. The proposed workflow provides an effective and transferable approach for high-precision burned-area extraction and quantification of wildfire-driving factors in mountainous forest regions.

1. Introduction

Forests are among the most vital ecosystems on Earth, serving not only as key habitats for global biodiversity but also as essential components of the hydrological cycle, carbon cycle, and soil conservation processes [1]. By absorbing carbon dioxide, regulating climate, and releasing oxygen, forests play an irreplaceable role in maintaining global climate stability [2]. However, under the intensification of global climate change and human disturbances, forest ecosystems are increasingly threatened, among which forest wildfires stand out as one of the most severe and widespread natural hazards with profound ecological consequences [3,4]. Wildfires are triggered by both natural factors (e.g., lightning) and human activities (e.g., agricultural burning), and they can lead to significant ecological damage, including the loss of forest resources, deterioration of air quality, increased carbon emissions, and reduced soil stability. When fires occur too frequently or with high intensity, the resilience and regeneration capacity of forest ecosystems are weakened, ultimately resulting in long-term functional degradation [5]. Each year, forest wildfires cause substantial ecological and economic losses globally, severely disrupting the carbon cycle and climate system and imposing considerable environmental and societal costs [6]. In recent decades, the scale, intensity, and frequency of forest wildfires have continued to increase worldwide, particularly in forest-rich regions such as North America, South America, and Australia [7]. In China, wildfires are predominantly concentrated in the northeast and southwest, especially in the northeastern forest zone and high-risk regions such as Yunnan and Sichuan, where changing climatic conditions are driving an upward trend in wildfire occurrence and severity, posing growing challenges to local ecosystems, economic development, and social security [8].

Cloud removal remains a major challenge in satellite-based Earth observation. Common approaches—such as Savitzky–Golay (SG) smoothing [9] and the Harmonic Analysis of Time Series (HANTS) [10]—can effectively suppress clouds and their shadows. However, they often perform poorly when the objective is to detect short-lived or abrupt surface changes, such as those associated with forest wildfires. Although HANTS efficiently smooths multi-temporal imagery, misclassification may still occur because clouds and active or burned surfaces exhibit similar spectral characteristics in the infrared domain, particularly during fire events [11]. Previous studies have also demonstrated that cloud and cloud-shadow contamination can easily be mistaken for burned surfaces, reducing the accuracy of post-fire mapping [12]. Furthermore, harmonic-based gap-filling algorithms such as HANTS may be unreliable for capturing short-duration and rapidly evolving land-surface dynamics [13]. Conventional spatial interpolation methods typically infill missing pixels using imagery from other dates, based on the assumption that surface conditions change gradually over time. However, because wildfires occur abruptly and unpredictably, substituting imagery from different periods rarely captures the true fire conditions. Prior work has highlighted that during active fire periods, rapid surface changes and cloud obstruction limit the reliability of temporal gap-filling or compositing, leading to uncertainties in burned area monitoring outputs [14,15,16]. Taken together, these issues indicate that single cloud-removal or interpolation strategies are inadequate for wildfire monitoring, as the fast-changing surface signals and persistent cloud effects during fire episodes exceed the capability of traditional approaches. Sentinel-2 offers high spatial resolution and a short revisit interval; nevertheless, extensive cloud cover remains problematic, especially over plateau regions [17]. Hofmeister et al. [18] highlighted that, despite the nominal 5-day revisit, acquiring cloud-free scenes in high-elevation areas within short time windows is difficult, which constrains the timeliness of fire monitoring. Landsat 8 revisits less frequently (8 days) but provides stable imagery at 30 m resolution, enabling precise burned area delineation over broad extents. Therefore, to overcome the limitations of any single sensor, integrating Landsat 8 and Sentinel-2 imagery—thereby combining finer spatial detail with denser temporal sampling—can substantially improve both the accuracy and the timeliness of wildfire monitoring. In current wildfire studies, many efforts rely on incident records from ground agencies, compiled from field reports, suppression activities or aerial patrols [19,20]. While useful, these datasets are constrained in spatial coverage and latency, leading to omissions that fail to capture the full distribution and dynamics of fires. Researchers often select a few typical events for analysis to validate single-fire identification [21,22,23]. Although this helps assess feature extraction and classifier suitability, the limited spatial focus hampers recognition of multiple or spatially dispersed fires at regional scales and can bias monitoring outcomes. At the regional scale, sample construction remains pivotal. Most studies still depend on manual labelling, in which researchers delineate burn perimeters by visual interpretation and select representative samples for training [8,24,25,26]. This works for large, clearly scarred fires but is labor-intensive, subjective and difficult to scale to large areas and multi-temporal monitoring.

To address these constraints, recent work has explored automated or semi-automated sample generation to enhance efficiency and objectivity [27,28]. Recent studies have demonstrated the potential of automated or semi-automated sample generation to improve burned-area mapping, yet important limitations remain. For example, Kulinan et al. [29] applied an object-based workflow to derive training samples from Sentinel-2 imagery for the Uljin wildfire in South Korea, showing that automated sampling can achieve high classification accuracy. Similarly, Silva and Modica [5] integrated dNBR with radar backscatter features to construct burned and unburned samples through a semi-automated procedure, illustrating the effectiveness of combining multisource indicators. Together, these studies suggest that automation can enhance mapping reliability, but their methods still depend on event-specific conditions and empirical thresholds, limiting generalisability across heterogeneous landscapes. Therefore, developing an approach capable of producing accurate and scalable regional fire recognition under limited training samples remains an important challenge—one that this study seeks to address.

The integrated use of multi-source remote sensing provides rich spectral and index features for burned area detection [30]. However, expanding the feature set often introduces high-dimensional redundancy and multicollinearity, which increases computational cost and can degrade classification accuracy and stability [31]. Establishing an efficient feature-selection strategy is therefore essential. Given the heterogeneity of burn signatures across spectral responses, terrain context and vegetation types, identifying the most discriminative variables is a central challenge. Logistic Regression (LR) [32], Random Forest (RF) [33] and Boruta [34] are widely used for feature selection and importance assessment. LR quantifies linear relations between predictors and class membership and facilitates significance testing; RF, as an ensemble learner, evaluates importance within non-linear spaces and is robust to noise and outliers; Boruta augments RF with shadow features to iteratively isolate globally significant variables. Combined, these methods reduce redundancy and systematically identify features that contribute most to burned area classification, enabling models that are both interpretable and accurate.

With the maturation of machine-learning methods, data-driven classifiers show strong potential for wildfire monitoring and burned area mapping [35]. Pixel-based classification, however, is prone to noise in high-resolution scenes—especially in southwestern mountainous regions and heterogeneous landscapes—leading to fuzzy boundaries and reduced accuracy. Object-based image analysis (GEOBIA) has therefore gained traction [36]. The Simple Non-Iterative Clustering (SNIC) algorithm aggregates spectrally similar, spatially contiguous pixels into super pixels by fusing spectral and spatial cues, thereby improving spatial consistency and boundary precision [37]. Although SNIC’s segmentation strengths are well documented, its deeper integration with machine-learning classifiers remains underexplored. In particular, under multi-source data and southwestern mountainous environments, the synergistic performance and generalisation of SNIC-based segmentation with machine-learning classifiers lack systematic validation. Accordingly, this study integrates multi-source imagery with SNIC segmentation and multiple machine-learning classifiers to build a high-accuracy workflow for burned area identification, aiming to deliver regional-scale, high-precision mapping with limited samples and to provide a new technical pathway for fire monitoring in southwestern mountainous regions.

This study develops an FS-SNIC-ML workflow for regional burned forest mapping in a mountainous environment by integrating multi-source optical fusion, semi-automatic sample construction, feature selection, object-based segmentation, and machine-learning classification. The specific objectives are to: (1) construct cloud-free, gap-free, and spectrally harmonised pre- and post-fire reflectance datasets by fusing Sentinel-2 and Landsat 8 imagery using a PIFS-based strategy; (2) implement and evaluate a semi-automatic workflow for generating burned and unburned samples under limited-sample conditions at the regional scale; (3) use LR, RF, and Boruta to identify the most discriminative spectral and index-based variables from the multi-source feature pool, thereby optimising model inputs; (4) integrate SNIC-based GEOBIA with multiple machine-learning classifiers to map burned forest areas in Dali Prefecture and to compare their accuracy and robustness in complex terrain; and (5) derive burn-severity patterns and quantify the influence and interactions of topographic, vegetation, and meteorological factors on wildfire hotspot density using dNBR-based clustering and geographical detector.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

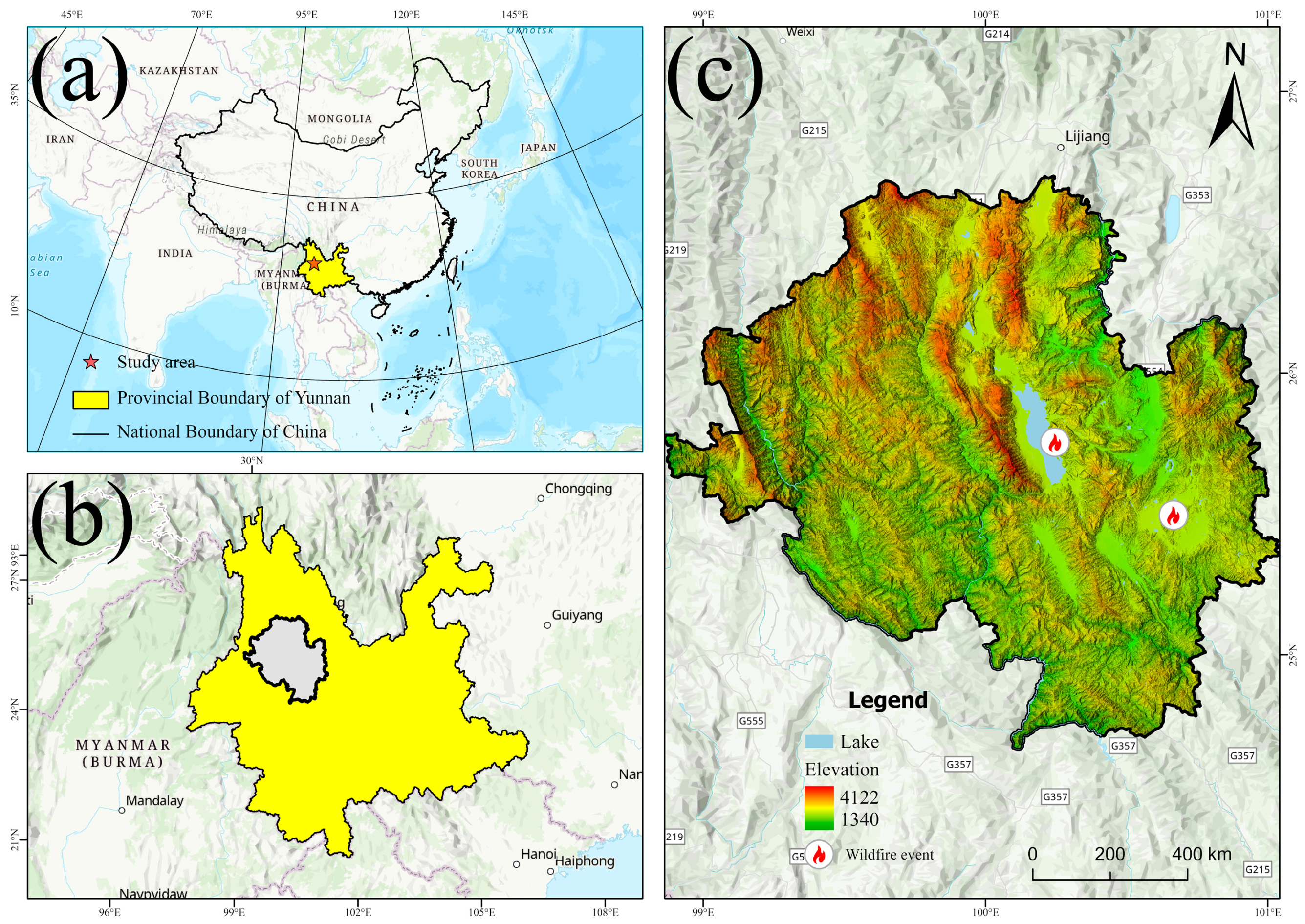

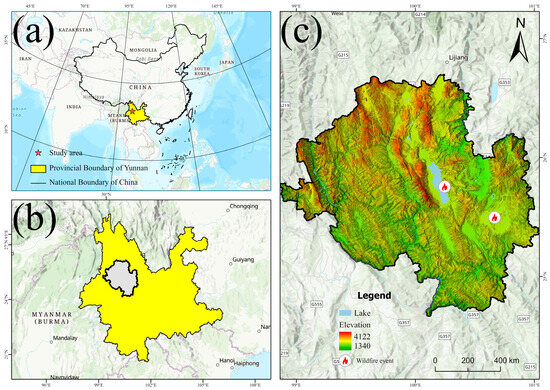

The study area is located in the Dali Bai Autonomous Prefecture of Yunnan Province, with geographical coordinates ranging from 98°52′E to 101°03′E and 24°41′N to 26°42′N, covering approximately 29,459 km2 (Figure 1). Situated in the western part of central Yunnan, Dali lies within a low-latitude plateau region characterised by a subtropical plateau monsoon climate. The region exhibits pronounced seasonal variations in precipitation, with a prolonged dry season and a wet season marked by concentrated and intense rainfall. These climatic conditions substantially influence the occurrence and spread of forest fires, especially during the dry season when large amounts of flammable materials accumulate, leading to elevated fire frequency and intensity [38]. The long-term alternation between dry and wet seasons further shapes the seasonal patterns of vegetation growth and fuel accumulation, providing a climate-driven foundation for wildfire occurrence. Dali features highly fragmented terrain dominated by continuous mountain ranges and deep valleys, with substantial elevation differences that create strong spatial heterogeneity. Such complex topography not only generates diverse microclimatic conditions but also forms channels along slopes and valleys that facilitate rapid fire spread, resulting in a typical high-risk mountain fire environment [39,40,41]. This terrain-driven spatial structure amplifies the combined effects of climate and fuel availability, contributing to greater uncertainty and more rapid-fire expansion. In addition, Dali has high forest coverage and diverse vegetation types, including widely distributed pine, cedar, and mixed broadleaf forests, which provide abundant and continuous combustible fuel, forming a major basis for the region’s frequent wildfires [42]. The combined influence of complex terrain and high fuel availability makes Dali a representative high-fire-risk region in Yunnan and the wider northwestern plateau, offering an ideal natural laboratory for validating regional-scale burned area mapping methods.

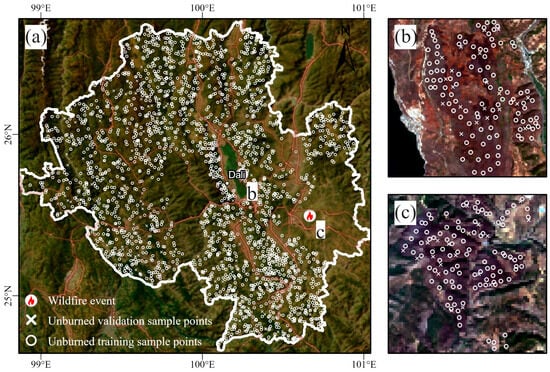

Figure 1.

Spatial context of the study area displayed through: (a) national-level location in China, (b) provincial-level extent in Yunnan, and (c) the corresponding digital elevation model.

2.2. Data Source and Preprocessing

2.2.1. Optical Satellite Data

To improve cloud-free data availability within short temporal windows, this study adopted an image fusion strategy in which Sentinel-2 (Earth engine snippet: ee.ImageCollection (“COPERNICUS/S2_SR_HARMONIZED”)) serves as the primary data source and Landsat 8 (Earth engine snippet: ee.ImageCollection (“LANDSAT/LC08/C02/T1”)) is used for gap filling. After cloud and shadow masking using the SCL band (Sentinel-2) and QA_PIXEL band (Landsat 8) [43], all datasets were radiometrically and geometrically harmonized and resampled to a unified spatial resolution of 30 m under the WGS 1984 Web Mercator Auxiliary Sphere projection [10]. To ensure spectral comparability before and after wildfire disturbance, two short-term acquisition windows were defined: pre-fire (1 December 2018–1 January 2019) and post-fire (1 June–1 July 2019) [21].

2.2.2. Reference Data

Forest Wildfire Event Data

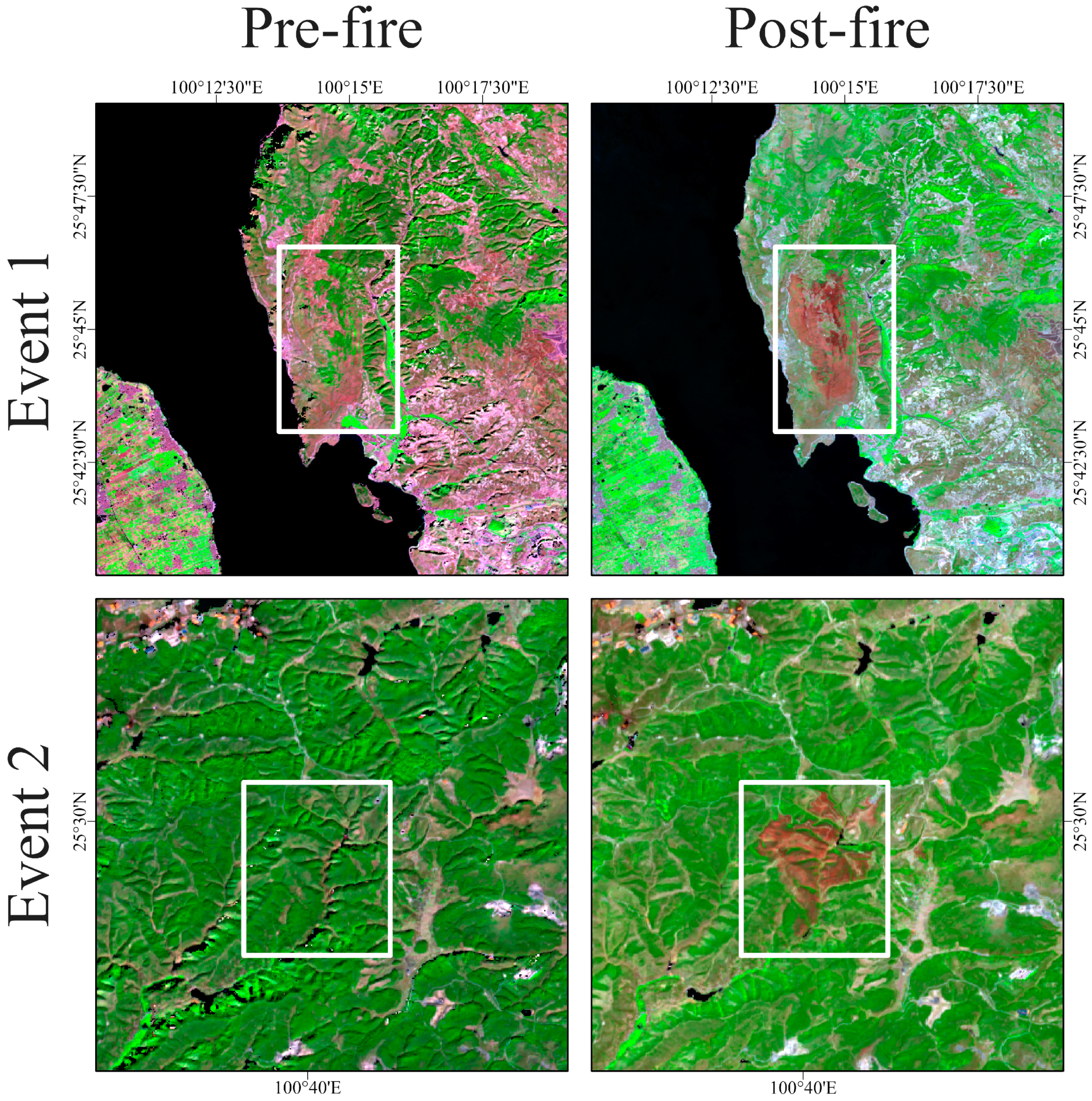

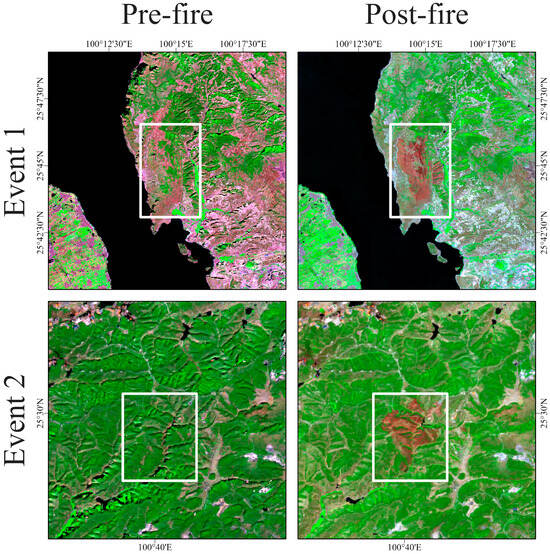

During the 2019 fire season, this study selected two typical forest wildfire events in Dali Prefecture, Yunnan Province, that were reported by mainstream media as the training dataset for burned area identification. The first event occurred on 9 February 2019 in Haidong Town, Dali City (https://www.chinanews.com.cn/m/sh/2019/02-10/8750164.shtml, accessed on 10 May 2025), and the second on 12 February 2019 at the Qinghua Cave Forest Farm in Xiangyun County (https://news.cnr.cn/native/city/20190215/t20190215_524512077.shtml?utm_source=ufqinews, accessed on 10 May 2025). Based on the geographic locations and temporal information provided in these reports, pre- and post-fire false-color composites were generated using the Red, NIR, and SWIR2 bands from Landsat 8 and Sentinel-2 imagery (Figure 2), which were then used to delineate the spatial extent of the two wildfire events (Figure 1c). For each wildfire event, 100 representative burned samples were collected to construct the training dataset. In addition, the official 2019 forest wildfire statistics provided by the Dali Prefecture Forestry and Grassland Bureau were used as the validation dataset. This dataset contains detailed fire attributes, including ignition location, ignition time, suppression time, cause of fire, fire type, classification level, and burned area, providing reliable information for evaluating the burned area extraction accuracy. For validation, 20 samples were selected from each wildfire event to form the independent validation set.

Figure 2.

Pre-fire and post-fire false-color composite images (SWIR–NIR–Red) derived from Sentinel-2 and Landsat 8 for two wildfire events in the study area. The left panels represent pre-fire conditions, while the right panels show post-fire conditions. White rectangles delineate the wildfire-affected areas selected for subsequent analysis.

Forest Cover Data

The pre-fire forest mask for Dali Prefecture was generated using the Dynamic World V1 dataset (Earth Engine snippet: ee.ImageCollection (“GOOGLE/DYNAMICWORLD/V1”)), which provides 10 m near–real-time land cover information derived from Sentinel-2 imagery [44]. All Sentinel-2 observations acquired in 2018 were processed to calculate the proportion of times each pixel was labeled as forest. Pixels with a forest occurrence greater than 60% were classified as forest, producing a pre-fire forest distribution map that ensured the wildfire events analyzed in this study occurred within forested areas. Based on this pre-fire forest extent, non-burned forest samples were constructed separately for training and validation. For the training dataset, 2400 non-burned forest samples were manually interpreted from post-fire Dynamic World imagery collected between 1 June and 1 December 2019. For validation, 480 non-burned forest samples were obtained from the 2019 China Land Cover Dataset (CLCD), downloaded from https://zenodo.org/record/5816591.

2.2.3. Driving Factor Data

A set of nine environmental variables, including topographic, vegetation, and meteorological factors, were selected to characterize the potential drivers of forest wildfire occurrence in Dali Prefecture. These factors were chosen based on established fire-ecology mechanisms, particularly their influence on fuel availability, vegetation moisture conditions, microclimate, and fire spread dynamics. The datasets were obtained from GEE and processed to a unified spatial resolution of 30 m for subsequent analysis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of environmental driving factors and their corresponding datasets used in this study.

Topographic factors (elevation, slope, and aspect) were derived from the SRTM DEM at a native resolution of 30 m. Slope and aspect were computed using the ee. Terrain module. These variables control fuel distribution, solar exposure, drainage conditions, and potential fire-spread pathways.

Vegetation indicators included NDVI and TVDI. NDVI was computed from Landsat 8 Surface Reflectance (LANDSAT/LC08/C02/T1_L2) using a median composite for the period from 1 January to 1 June 2019. Before compositing, cloud, shadow, and snow pixels were removed using the QA_PIXEL band to ensure the reliability of spectral indices. TVDI was calculated using a combination of Landsat 8–derived NDVI and land-surface temperature (LST) following the standard triangular feature-space method. LST was retrieved from the thermal infrared bands of Landsat 8 using a mono-window algorithm, with land-surface emissivity estimated via an NDVI threshold method. The dry and wet edges of the NDVI–LST feature space were extracted automatically using the minimum/maximum envelope of the scatter distribution. TVDI derived through this procedure represents pixel-level vegetation moisture stress, which is closely related to the flammability of surface fuels.

Meteorological factors included cumulative precipitation, mean temperature, and soil moisture, all derived from the TerraClimate dataset (IDAHO_EPSCOR/TERRACLIMATE). The native ~4 km TerraClimate products were resampled to 30 m using bilinear interpolation to maintain spatial compatibility with Landsat-based predictors; we acknowledge that such downscaling may introduce scale-related uncertainties and have added corresponding explanations in the revised manuscript. Precipitation was summed over the study period, while mean temperature and soil moisture were averaged from 1 January to 1 June 2019. All TerraClimate variables were corrected using the official scale factors (e.g., tmmn/tmmx values multiplied by 0.1 to convert to degrees Celsius; soil water storage expressed in mm).

2.3. Methods

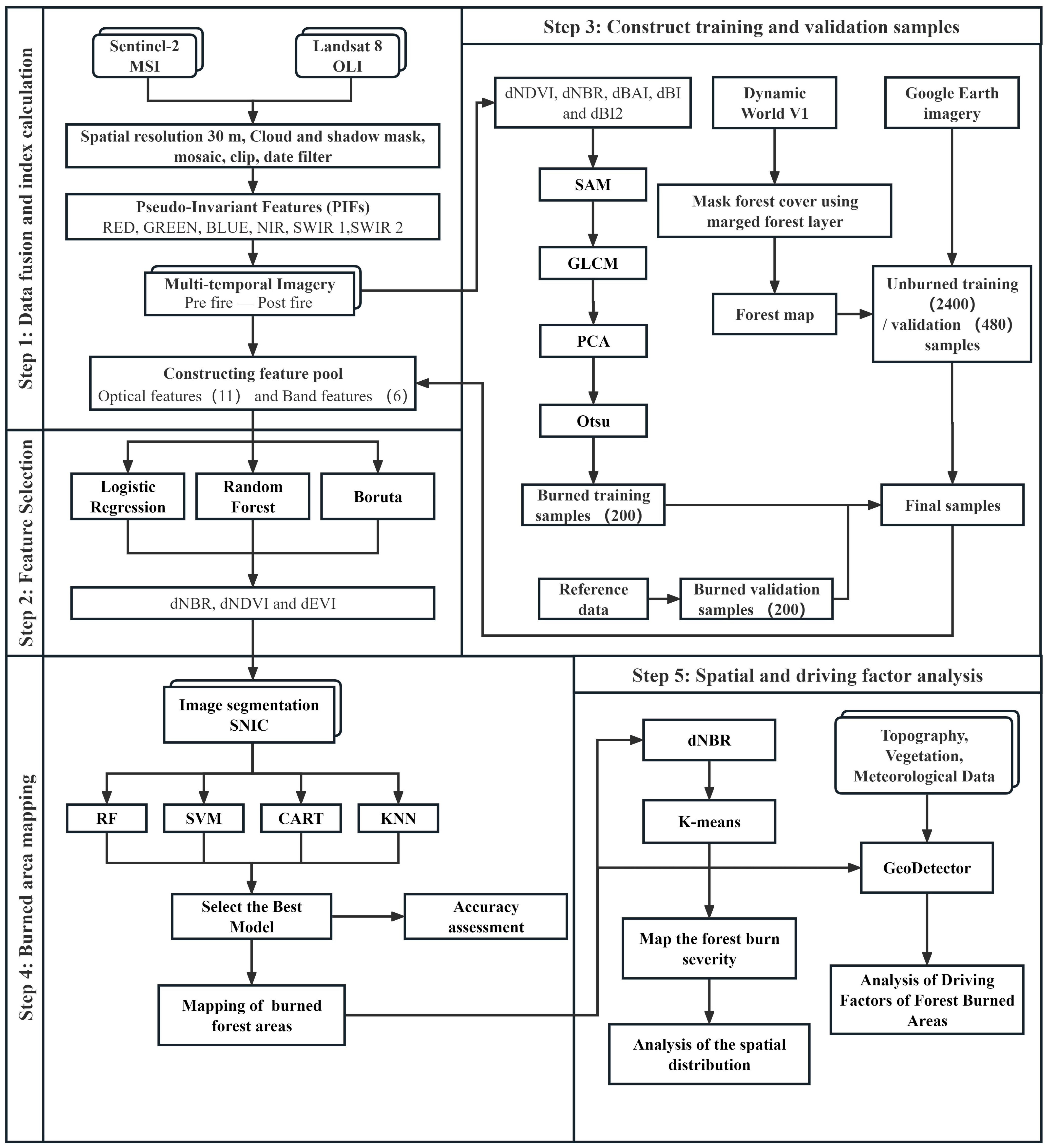

2.3.1. Method Overview

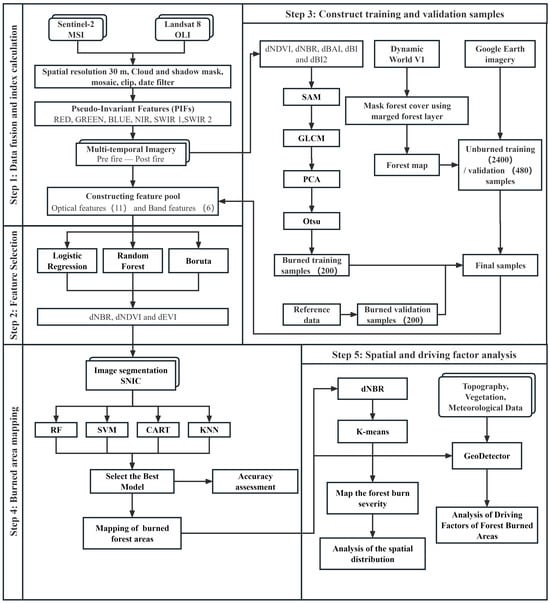

This study developed an FS-SNIC-ML workflow for forest burned area identification (Figure 3). In Step 1, Sentinel-2 MSI and Landsat 8 OLI imagery were acquired and preprocessed, including cloud and shadow masking, mosaicking, clipping, and resampling to a unified spatial resolution of 30 m. Multitemporal pre-fire and post-fire imagery was then constructed using Pseudo-Invariant Features (PIFSs), and spectral features together with vegetation indices were extracted to form the feature pool. In Step 2, LR, RF, and Boruta were applied for feature selection, and dNBR, dNDVI, and dEVI were identified as the most discriminative variables. In Step 3, burned samples were automatically generated using SAM, GLCM, PCA, and Otsu methods, while unburned samples were derived from the Dynamic World forest layer and visual interpretation of Google Earth imagery. In Step 4, SNIC segmentation was performed to generate object-based image regions, and burned area classification was conducted using RF, SVM, CART, and KNN classifiers, followed by selecting the optimal model for accuracy assessment. In Step 5, the final dNBR image was combined with K-means clustering to analyze the spatial pattern of burn severity, and GeoDetector was employed to identify the major driving factors of burned area distribution.

Figure 3.

Workflow of the FS-SNIC-ML approach for mapping forest burned area.

2.3.2. Multi-Source Optical Data Fusion

To obtain cloud-free, spectrally consistent, and temporally aligned pre-fire and post-fire reflectance datasets, we developed a multi-source optical data fusion strategy integrating Sentinel-2 and Landsat 8 imagery within predefined temporal windows. Sentinel-2 was used as the primary data source due to its higher spatial resolution. All valid Sentinel-2 observations within each window were composited using a median operator to generate a base mosaic:

where denotes the pixel location and is the temporal window. Due to frequent cloud cover in high-elevation areas, Sentinel-2 still exhibited data gaps, which may distort change detection results. Therefore, Landsat 8 observations from the same period were introduced to complement missing pixels.

Pseudo-Invariant Features (PIFSs) Extraction

To reduce spectral discrepancies between the two sensors, cross-sensor spectral harmonization was performed using pseudo-invariant features (PIFSs), which are surface targets characterized by temporal and spatial reflectance stability. PIFSs were identified using a two-step procedure:

To reduce spectral discrepancies between the two sensors, cross-sensor spectral harmonization was performed using PIFSs, which are surface targets characterized by temporal and spatial reflectance stability. PIFSs were identified using a two-step procedure:

- Candidate selection:

We first masked water bodies, vegetation, and cloud-shadow regions using Sentinel-2 SCL and NDVI thresholds to ensure that only radiometrically stable surfaces (e.g., bare soil, infrastructure, dry riverbeds) were retained.

- 2.

- Statistical refinement:

A robust regression-based filtering was applied to remove outliers. Only pixels falling within the central 60–90% of the reflectance distribution for both sensors were retained as final PIFS samples.

This process ensured that PIFSs remained stable across sensors and dates, forming reliable samples for band-wise spectral correction. For each spectral band , a linear regression model was constructed:

The harmonized Landsat 8 reflectance was computed as:

Pixel-Level Fusion and Temporal Constraints

The final fused reflectance was generated using a pixel-by-pixel decision rule:

The 30-day threshold follows previous optical data fusion literature and represents a balance between spectral stability and data availability. Pixels labeled as null were retained as masked areas and did not affect subsequent dNBR differencing because both pre- and post-fire composites were required to be valid simultaneously for classification.

This fusion approach ensures that Sentinel-2 maintains its spatial detail while harmonized Landsat 8 observations effectively fill cloud-induced gaps. The resulting fused pre-fire and post-fire images are spatially continuous and spectrally uniform, forming high-quality datasets for differencing and burned area mapping.

Spectral Consistency Evaluation

To quantitatively validate the effectiveness of spectral harmonization, we evaluated the spectral consistency between Sentinel-2 reflectance and harmonized Landsat 8 reflectance using PIFS samples. Three metrics were computed for each spectral band: coefficient of determination (R2), root mean square error (RMSE), and mean bias (BIAS).

2.3.3. Burned/Unburned Samples

The generation of training samples in this study was divided into two categories: burned samples and unburned samples.

Burned Samples

The generation of burned samples followed the automatic sample generation approach proposed by Almo Senja Kulinan [29] and incorporated two major forest wildfire events reported by mainstream media as reference data. Burned areas were automatically extracted from post-fire imagery through a sequence of processing steps to ensure accurate identification of the burned area.

First, change features were derived. Four spectral indices—NDVI, NBR, BI, BI2, and BAI—were calculated and appended as additional bands to each image. The indices and their corresponding expressions are listed in Appendix A. Spectral differences between pre- and post-fire images were then analysed using the Spectral Angle Mapper (SAM) technique. This method quantifies the angular difference between spectral vectors of the same pixel before and after the fire. A larger angle indicates a greater degree of spectral change caused by burning, while a smaller angle suggests limited disturbance. The angle between the target vectorx and its reference vector y can be determined using the following equation:

where represents the similarity angle between the two spectra, is the number of bands, and and are the target (pre-fire) and reference (post-fire) spectra in band , respectively.

Next, texture features were extracted using the Gray-Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM) to describe spatial relationships between pixels. Seven texture metrics—angular second moment, contrast, entropy, correlation, inverse difference moment, variance, and mean—were computed within a 3 × 3 moving window. These texture measures enhance the differentiation between burned and unburned surfaces and improve classification accuracy. The texture indices used in this study and their corresponding expressions are listed in Appendix A.

To reduce redundancy and improve computational efficiency, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was used to identify the most representative variables. The first principal component, which explained the largest proportion of variance, was selected as the primary feature for sample extraction.

Finally, the Otsu adaptive thresholding method was applied to distinguish burned from unburned pixels. This approach automatically determines an optimal threshold based on pixel-intensity contrast. Pixels exceeding the threshold were classified as burned, and the resulting binary layer was converted into vector polygons used as candidate regions for random sampling.

Unburned Samples

Given the substantial variation in forest distribution across counties in Dali Prefecture, omitting spatial stratification would cause non-burned samples to be disproportionately concentrated in counties with larger forested areas, thereby reducing the generalizability of the classification model. To minimize such sampling bias and enhance the spatial representativeness of the dataset, a county-level stratified sampling strategy was implemented. Within the unburned forest mask of all administrative counties in Dali Prefecture—including Yangbi, BinChuan, Heqing, Binchuan, Jianchuan, Dali, Weishan, Nanjian, Midu, Yongping, Yunlong, and Eryuan—200 non-burned forest samples were manually interpreted for each county to construct the training dataset, while an additional 40 non-burned samples were randomly selected from each county to form the validation dataset. This design resulted in a spatially balanced and county-consistent sample framework. This stratified sampling approach effectively accounts for differences in forest coverage and wildfire severity among counties, ensuring that both training and validation samples are evenly distributed across the region. It provides a stable, reliable, and representative foundation for subsequent burned area classification.

2.3.4. FS-SNIC-ML Mapping Model

Feature Selection

To distinguish forest-related wildfires from those occurring in non-forest areas, a comprehensive feature pool was constructed based on previous studies. All spectral and index-based features were computed as pre-fire minus post-fire differences, and the corresponding formulas are provided in Appendix A. Six primary spectral bands (Blue, Green, Red, NIR, SWIR1, and SWIR2) were extracted from the optical images. From these reflectance bands, eleven vegetation-related indices were further derived, including NBR, NDVI, DVI, EVI, BI, BI2, BAI, RDVI, SAVI, RI, and NDWI [45]. These difference-based features capture the magnitude of spectral change associated with vegetation condition, soil moisture, and surface water dynamics, forming the basis for identifying burned and unburned areas.

In this study, Logistic Regression (LR), Random Forest (RF), and Boruta were applied to select informative variables for burned area mapping. The three resulting feature subsets were then merged using a union operation to retain all features identified as important by any of the methods, ensuring that no potentially relevant variable was discarded. LR quantifies the contribution of each feature by mapping a weighted combination of predictors to a probabilistic output, and its generalization performance was improved using cross-validation [32]. RF, as an ensemble learning method, aggregates multiple decision trees, handles high-dimensional data effectively, reduces overfitting, and provides feature importance measures [46]. Boruta, built upon RF, evaluates each real feature against randomized shadow features to identify truly informative predictors, thereby reducing redundancy and improving model robustness [34]. The combined use of these three methods, along with the union of their selected features, enhances both the accuracy and stability of the burned-area classification.

SNIC-ML Modelling

In this study, burned forest areas were mapped using a GEOBIA-based workflow, where optical satellite data served as the primary input. The Simple Non-Iterative Clustering (SNIC) method was adopted for segmentation, and the resulting objects were subsequently classified using a machine learning algorithm. As an object-oriented image analysis approach, GEOBIA groups spectrally and spatially similar pixels into meaningful image objects, allowing a more reliable representation of surface characteristics. Compared with the widely used SLIC method, SNIC offers faster computation and lower memory consumption through a non-iterative clustering scheme, which is advantageous when processing large and heterogeneous datasets [47].

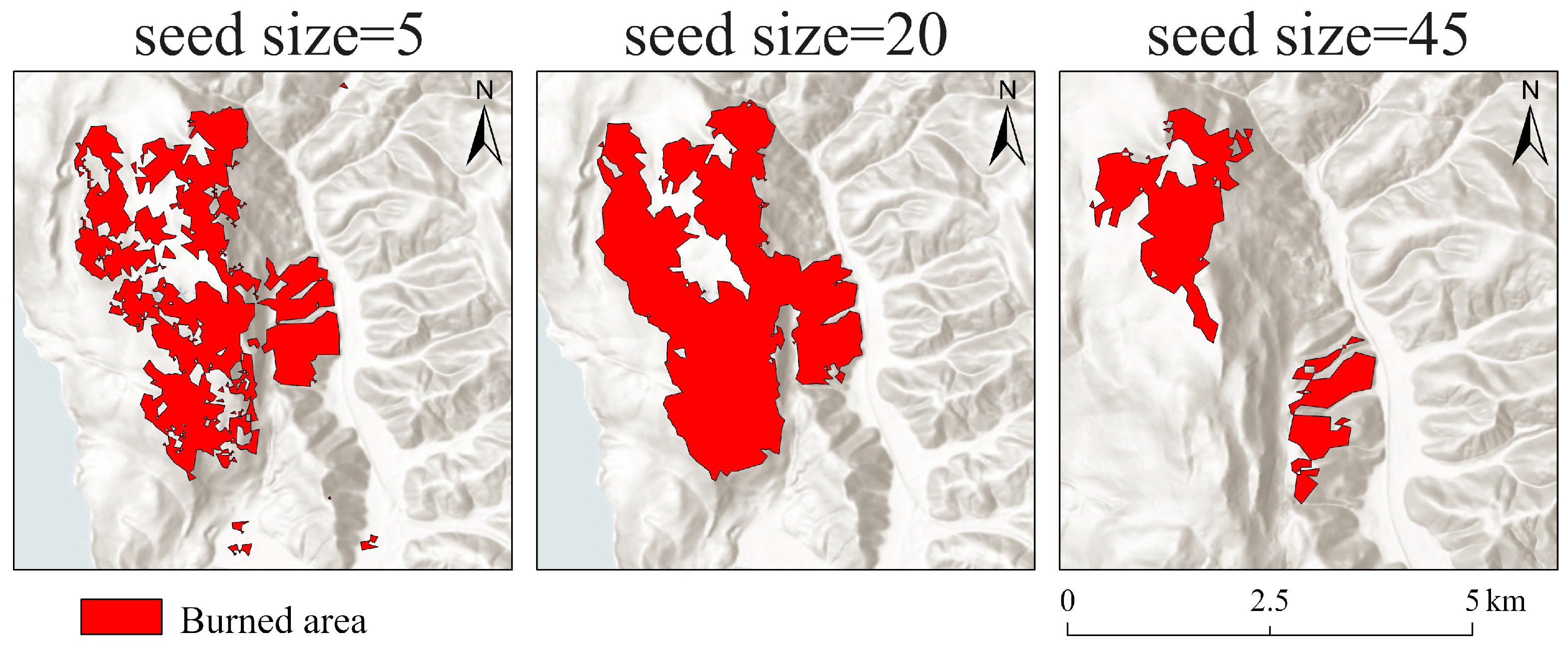

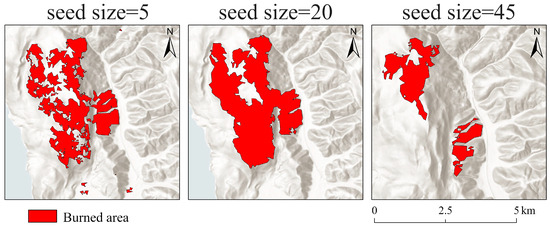

SNIC segmentation is governed by several key parameters, including seed size, compactness, connectivity, and neighborhood extent. Among these, seed size strongly influences the granularity of the resulting objects. As shown in Figure 4, using a small seed size (5) produces overly fragmented segments and noisy burned patches, while a large seed size (45) results in excessive merging and a loss of fine-scale fire boundaries. A medium seed size (20) provides a better balance between spatial detail and internal homogeneity, generating coherent burned patches that more accurately match the underlying fire pattern. Based on these parameter-tuning tests, the SNIC configuration used in this study was set to a seed size of 20, compactness of 0, connectivity of 8, and a neighborhood size of 256. For each segment, spectral statistics including the mean, variance, and standard deviation were extracted and used as object-level features in the subsequent classification stage.

Figure 4.

Effects of different SNIC seed sizes on burned area segmentation. Comparison of segmentation results using seed sizes of 5, 20, and 45 pixels.

To identify burned areas, this study adopted an object-based machine-learning classification framework, with all parameter tuning and data-quality checks conducted within the GEE environment. GEE provides built-in implementations of several widely used classifiers, including Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Classification and Regression Trees (CART), and k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN). Within the unified workflow of SNIC segmentation and object-level feature extraction, RF was first optimized through a series of preliminary experiments. The optimal hyperparameter configuration consisted of 150 trees (n_estimators = 150), max_features = “sqrt”, min_samples_split = 2, and min_samples_leaf = 1, which achieved a desirable balance between model stability and classification accuracy. To further benchmark RF against alternative classifiers under the same SNIC-based workflow, three additional algorithms—SVM (RBF kernel, C = 1.0, γ = 0.01), CART (max_depth = 20, min_samples_leaf = 1), and KNN (k = 5, weights = “uniform”)—were trained and validated using the same set of SNIC-derived object features, ensuring a consistent and comparable assessment across classifiers.

Accuracy Assessment

To evaluate the accuracy of the classification results, we used the confusion matrix method and quantified the model’s performance through several metrics [48]. A confusion matrix was employed to assess accuracy with Overall Accuracy (OA), User’s Accuracy (UA), Producer’s Accuracy (PA), and F1-Score.

where denotes true positives, denotes false positives, denotes true negatives, and denotes false negatives.

2.3.5. Burn Severity

In this study, burn severity was derived using the differenced normalized burn ratio (dNBR = NBRbefore − NBRafter). Because the burned area had already been identified during the classification stage, severity thresholds were applied only to the mapped burned pixels. To avoid subjective threshold selection, the K-means clustering algorithm [48] was used to group dNBR values within the burned area, automatically dividing burn severity into three levels: low, moderate, and high. K-means, a classical unsupervised clustering method, iteratively assigns samples to the nearest cluster centroid and updates the centroids until convergence or a predefined maximum number of iterations is reached. The clustering procedure was implemented in Python 3.12. Given that dNBR reflects vegetation loss, pixels assigned to the “unchanged” class were considered classification errors. Additionally, the burn severity assessment helped identify the class that contributed most to uncertainty in burned area classification.

2.3.6. Geographical Detector

In this study, the geographical detector (GeoDetector) was employed to quantitatively assess the dominant environmental factors influencing forest wildfire occurrence and hotspot density in Dali Prefecture, and to elucidate the underlying spatial mechanisms [49]. GeoDetector is a spatial statistical framework designed to detect spatial stratified heterogeneity and identify its potential driving forces. Its fundamental assumption is that if an explanatory variable has a significant impact on a dependent variable (here, wildfire hotspot density), then the spatial distribution of should exhibit significant differences among the strata of . By comparing within-stratum and between-stratum variance structures, GeoDetector can effectively quantify the explanatory power of environmental factors on the spatial pattern of wildfires.

In this work, two core modules of GeoDetector were applied. The factor detector was used to evaluate the explanatory power of individual environmental variables for the spatial variation in wildfire hotspot density, while the interaction detector was used to determine whether pairs of factors exhibit enhanced, weakened, or independent effects when acting jointly. Together, these modules allow us not only to rank the relative importance of single factors, but also to diagnose potential synergies and nonlinear interactions among topographic, vegetation, and climatic drivers.

The dependent variable was defined as a continuous wildfire hotspot density surface derived from a Gaussian kernel density estimator (KDE). Confirmed burned and unburned sample locations were used as spatial input points, and a Gaussian kernel with a bandwidth of 0.01° (approximately 1 km) was applied to generate a smoothed density surface at 1 km spatial resolution. The bandwidth was determined based on Silverman’s rule of thumb combined with empirical sensitivity analysis to balance the preservation of local hotspot features against excessive smoothing. The resulting KDE raster captures the local clustering intensity of wildfire occurrences and provides a robust continuous proxy for wildfire activity across the study area.

Eight representative environmental variables were selected as independent factors: elevation, NDVI, TVDI, aspect, cumulative precipitation, slope, soil moisture, and mean temperature The choice of these variables is grounded in established fire-ecology mechanisms. Elevation and slope regulate fuel distribution, topographic exposure, and potential fire spread pathways. Aspect controls incoming solar radiation and microclimatic conditions, thereby affecting fuel dryness. NDVI and TVDI, respectively, characterize vegetation abundance and moisture stress, both of which are directly linked to fuel load and flammability. Temperature and precipitation shape fire weather conditions and fuel moisture dynamics, while soil moisture reflects near-surface hydrological status and influences ignitability and fire persistence. Together, these variables constitute a comprehensive set of potential drivers of wildfire occurrence and intensity.

To meet the requirement of GeoDetector for discretized explanatory variables, all continuous factors were converted into categorical strata using an optimal quantile-based discretization scheme. Specifically, for each variable, candidate numbers of strata in the range of 3 to 15 were tested, and the configuration that maximized the q-statistic for that factor was selected as the optimal stratification. This strategy ensures relatively balanced sample sizes across strata, avoids empty or extremely sparse classes, and enhances the sensitivity and stability of spatial heterogeneity detection.

The explanatory power of each factor was quantified using the q-statistic, defined as:

where represents the strata of factor , and denote the number of samples and the variance within stratum , and and correspond to the total sample size and global variance of the study area. The value of ranges from 0 to 1, with a higher value indicating stronger explanatory power of the factor for the spatial distribution of wildfire hotspot density.

For the interaction detector, the model first calculates the individual q-values of two factors, and , and then computes their joint explanatory power under combined stratification, expressed as . By comparing these values, the interaction type—such as nonlinear weakening, single-factor nonlinear weakening, bi-factor enhancement, independence, or nonlinear enhancement—can be determined according to the criteria summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Geographic detector interaction factor level judgment.

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation of Fusion

Table 3 shows the R2, RMSE, and BIAS metrics for different bands after the fusion of Sentinel-2 and Landsat 8 data. The R2 values for all bands exceed 0.80 in both the pre-fire and post-fire periods, with the R2 value for the blue band in the post-fire period reaching 0.88, and the R2 value for the SWIR2 band being 0.83. The RMSE values remain low in both the pre-fire and post-fire periods, particularly in the post-fire period, where the RMSE value for the blue band is 0.042. The BIAS values for all bands are close to zero, with BIAS values for all bands remaining between −0.002 and −0.005 in both the pre-fire and post-fire periods.

Table 3.

Evaluation of Fusion Results for Sentinel-2 and Landsat 8 Data Across Different Bands.

3.2. Training/Validation Samples and Features

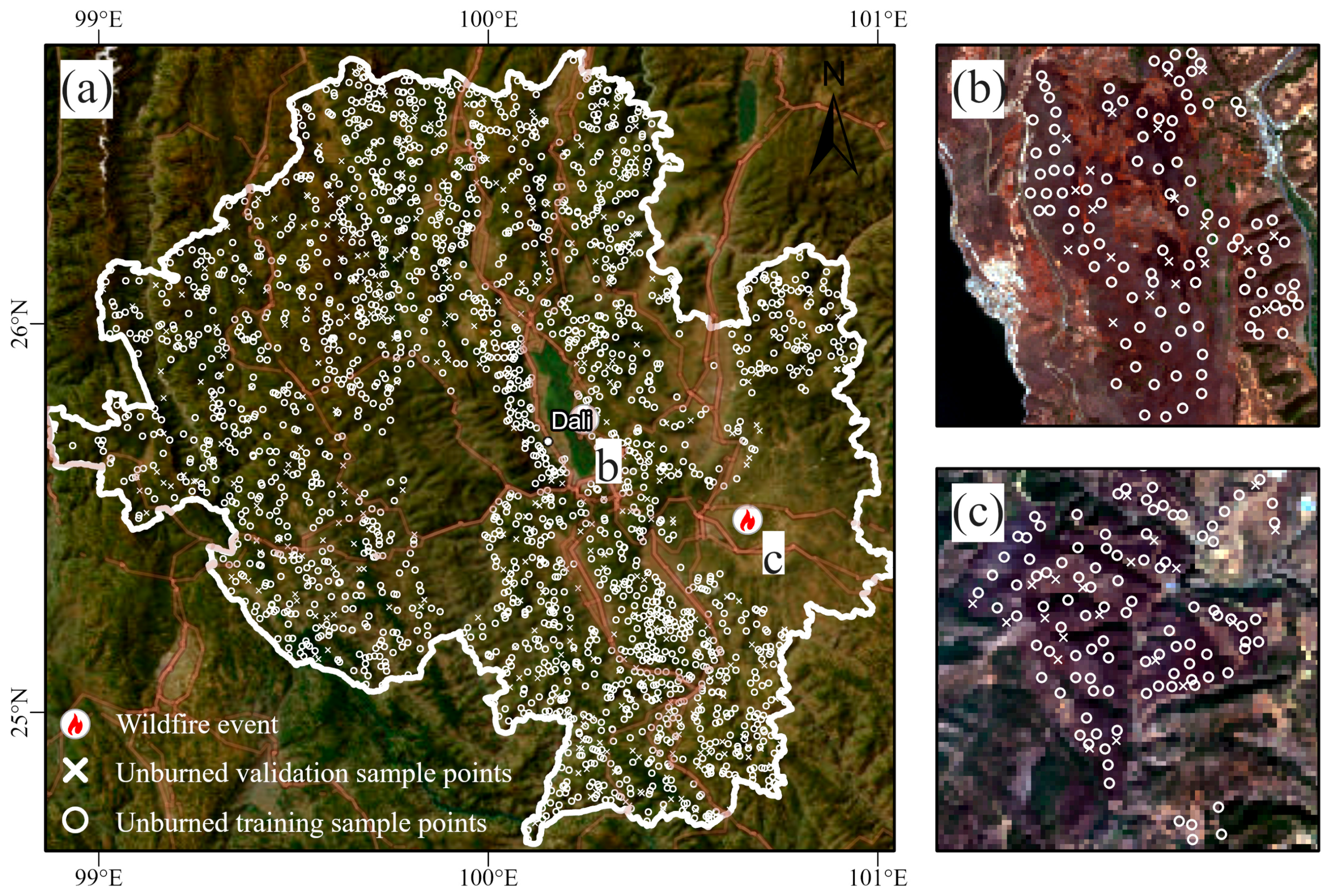

In this study, a training and validation dataset of forest burned and unburned areas was constructed for Dali Prefecture (Figure 5). The burned samples were derived from actual wildfire events in Haidong Town of Dali City and the Qinghua Cave Forest Farm in Xiangyun County, ensuring strong representativeness. Unburned forest samples were obtained through stratified random sampling across all counties in Dali Prefecture to guarantee spatially balanced coverage. Specifically, the burned dataset consisted of 200 training samples and 40 validation samples (Figure 5b,c), while the unburned dataset included 2400 training samples and 480 validation samples (corresponding to Figure 5a). The use of a relatively limited but representative sample size aimed to evaluate whether the classification model could, under constrained training data conditions, effectively capture the spectral differences between burned and unburned areas and thereby achieve accurate burned-pixel identification across a broader regional extent.

Figure 5.

Distribution of training and validation samples for forest burned and unburned areas in Dali Prefecture. (a) Unburned forest samples, and (b,c) burned forest sample areas. A high-resolution version of this figure is available in the online edition of the article.

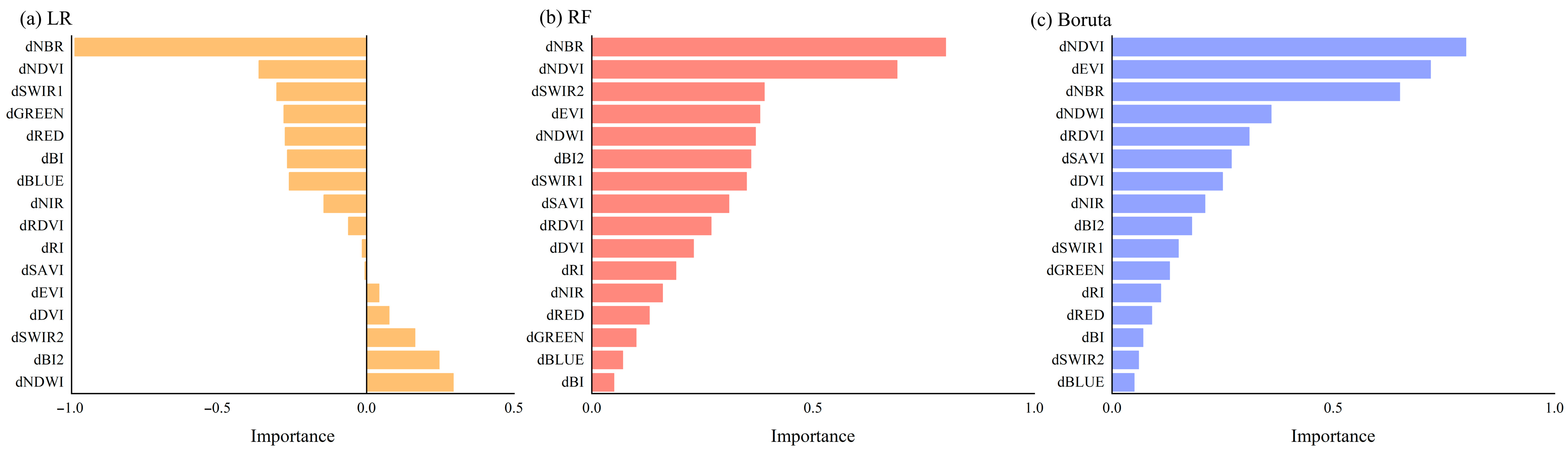

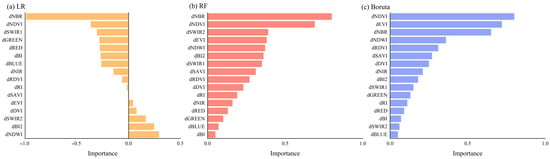

After establishing the training and validation samples, we further normalized all input features to ensure that the three feature selection models could be evaluated on a consistent scale. As shown in Figure 6, features with an absolute importance value greater than 0.5 were considered the most influential. Based on the combined results of the three feature selection methods—LR, RF, and Boruta—dNBR, dNDVI, and dEVI were consistently identified as the most critical variables. These spectral difference features exhibited strong discriminatory ability in separating burned from unburned forest areas. Specifically, dNBR (difference Normalized Burn Ratio), dNDVI (difference Normalized Difference Vegetation Index), and dEVI (difference Enhanced Vegetation Index) effectively captured the key spectral changes in vegetation condition before and after wildfire events, making them robust and reliable indicators for burned area identification.

Figure 6.

Assessment of key optical variables for burned forest mapping using LR, RF, and Boruta. (a) Logistic Regression (LR); (b) Random Forest (RF); and (c) Boruta.

3.3. Classification Accuracy and Mapping of Burned Forest Area

3.3.1. Evaluation of Model Performance

Table 4 summarizes the classification performance of the four classifiers for both burned and unburned forest areas, based on the confusion-matrix-derived accuracy metrics and independent validation samples. Overall, RF exhibited the strongest performance across all indicators, demonstrating a high level of agreement between the predicted burned area map and the reference data. For the burned class, RF achieved an OA of 92.08%, while the OA for the unburned class increased to 94.06%. The UA and PA reached 93.94% and 92.08%, respectively, yielding an F1-Score of 93.00%. These results indicate that RF maintains high stability and reliability even in mountainous regions characterized by complex terrain and diverse vegetation conditions. SVM ranked second among the tested classifiers. Its burned-class OA was 89.09%, and the unburned-class OA was 91.09%, with UA and PA of 90.91% and 89.09%, respectively. Although slightly lower than RF, SVM still showed strong generalization ability and consistent mapping performance, effectively identifying medium- to large-scale burned patches. CART delivered moderate performance. The OA for the burned and unburned classes was 83.17% and 85.15%, respectively, and both UA and PA were around 83%. These results suggest that CART can successfully capture major burned areas, yet is more prone to misclassification in transitional zones such as shadowed regions or heterogeneous mixed pixels. In contrast, KNN exhibited the lowest accuracy. For the burned class, its OA, UA, and PA were 69.31%, 70.71%, and 69.31%, respectively, with an F1-Score of 69.99%. These values are considerably lower than those of the other classifiers, indicating that KNN is more sensitive to spectral noise and less capable of distinguishing burned patches in regions with high spectral variability.

Table 4.

Accuracy assessment of four classifiers for burned and unburned forest areas.

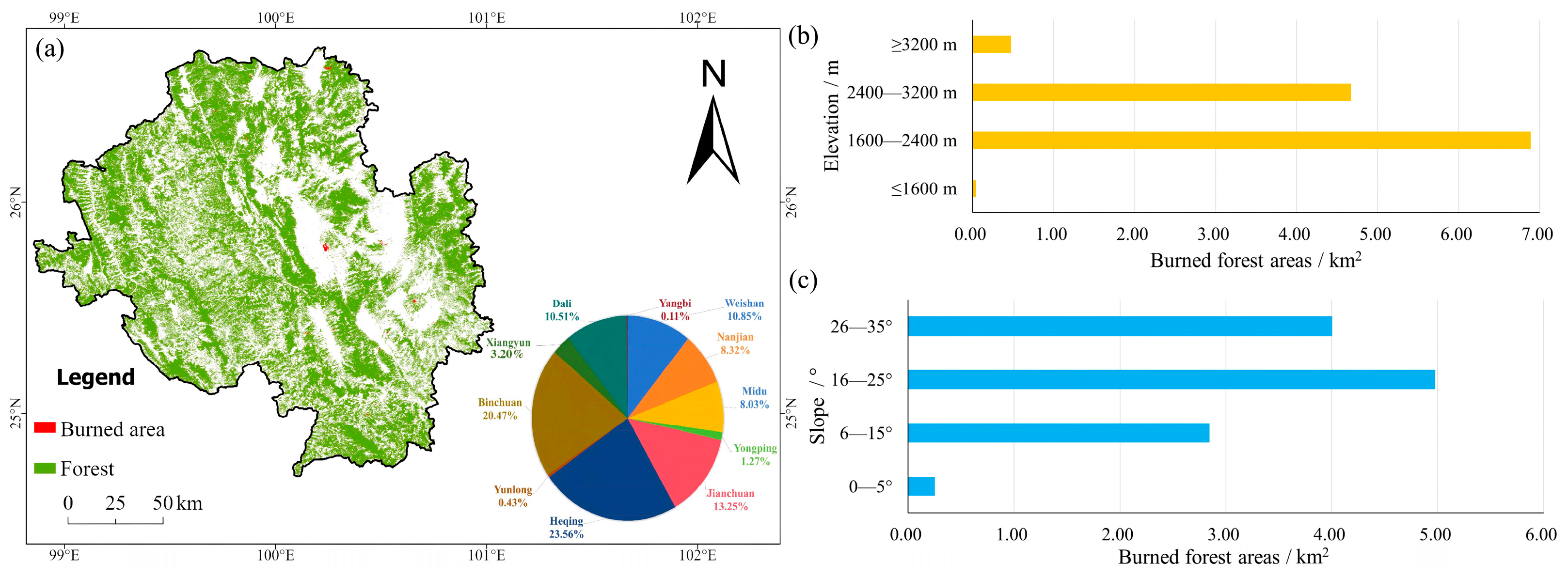

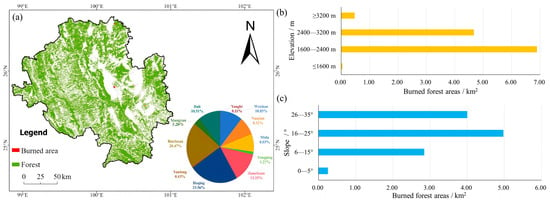

3.3.2. Mapping of Burned Forest Area

Figure 7 presents the forest burned-area mapping results derived from the optimal SNIC+RF model. As shown in Figure 7a, approximately 12.07 km2 of burned forest was identified across Dali Prefecture, exhibiting pronounced spatial heterogeneity at the county level. The majority of burned areas occurred in Heqing (23.56%), Binchuan (20.47%), and Jianchuan (13.25%) counties. Weishan, Dali, and Nanjian counties accounted for moderate proportions (8–11%). In contrast, Midu and Xiangyun showed relatively small burned areas, while Yunlong and Yangbi contributed less than 1%. No notable burned areas were detected in Eryuan County. Figure 7b further indicates clear variations in burned area across elevation classes. Burned areas were highly concentrated in mid-elevation zones, with the 1600–2400 m range exhibiting the largest burned extent (6.89 km2; 57.0%), followed by 2400–3200 m (4.67 km2; 38.7%). Burned areas in the low (≤1600 m) and high (≥3200 m) elevation zones were minimal, accounting for only 0.3% and 3.9%, respectively. Figure 7c shows similarly distinct patterns across slope gradients. Burned areas were mainly distributed within the 16–25° (4.98 km2; 41.3%) and 26–35° (4.00 km2; 33.1%) slope classes. Gentler slopes contributed much less to the total burned area, with 6–15° accounting for 2.84 km2 (23.5%), and 0–5° contributing only 0.25 km2 (2.1%). Overall, the burned areas were more frequently concentrated in terrain with moderate to steep slopes.

Figure 7.

Spatial distribution and topographic differentiation of burned forest areas in Dali Prefecture. (a) Burned forest mapping results obtained using the optimal SNIC+RF model, with the pie chart on the right showing the proportion of burned forest area across the 12 counties. (b) Distribution of burned forest areas across different elevation ranges. (c) Distribution of burned forest areas across different slope classes. A high-resolution version of this figure is available in the online edition of the article.

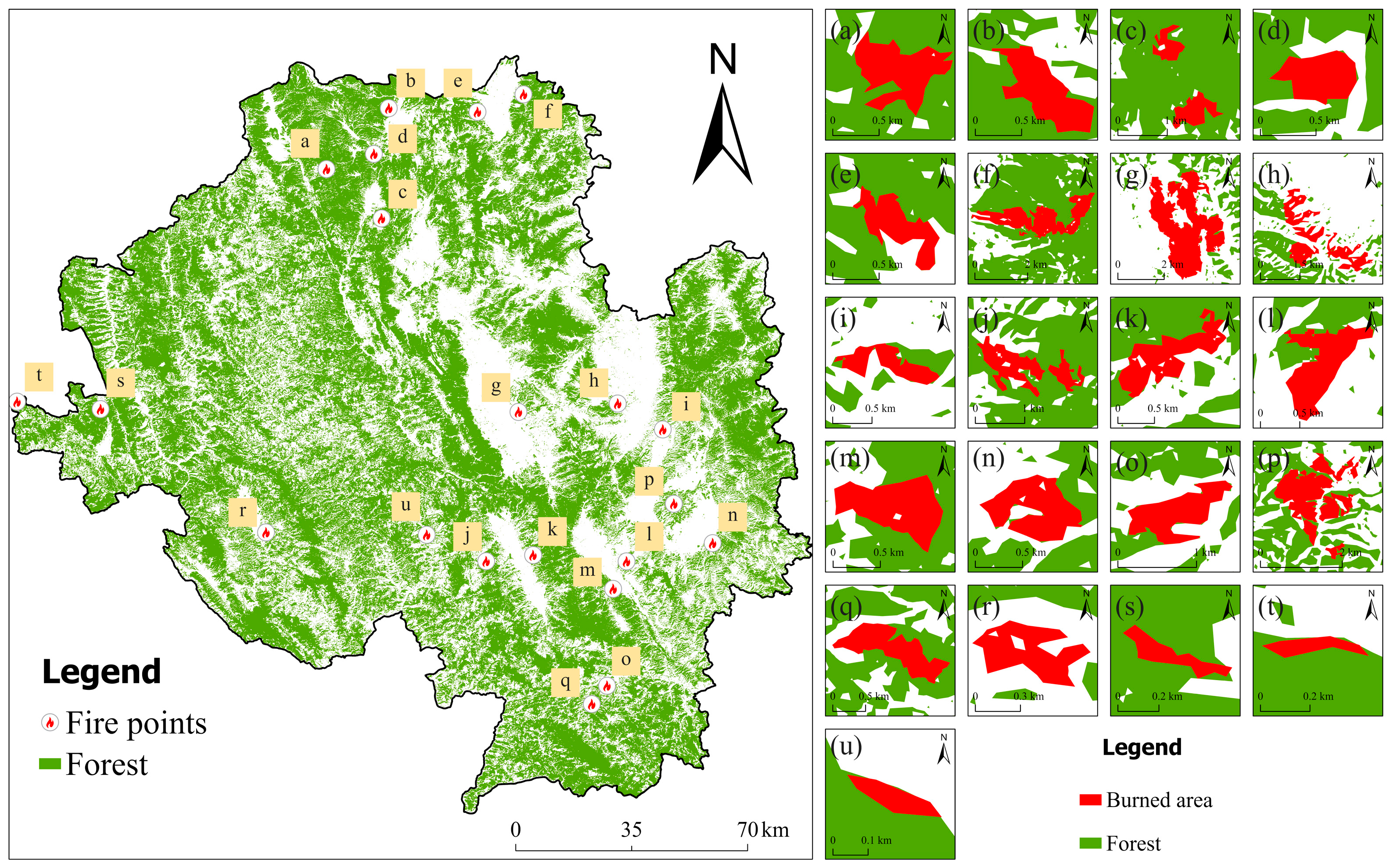

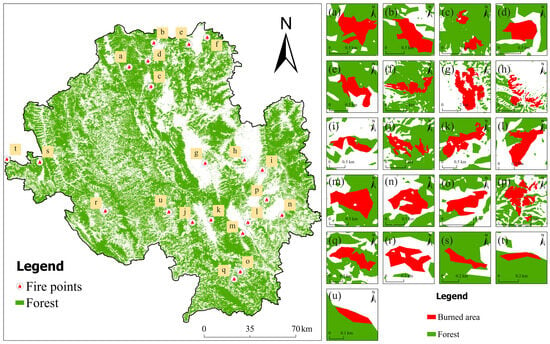

Figure 8 illustrates the burned areas of 21 forest wildfires that occurred during the fire season in Dali Prefecture, derived using the SNIC+RF model. The results clearly demonstrate the model’s applicability and stability across different fire scenarios. At the regional scale, these fire events are widely distributed across the major forested zones of Dali—including the northeastern and central mountainous areas as well as the western and southern margins—indicating that the selected wildfire samples are highly representative. The zoomed-in panels on the right further show that the burned patches vary substantially in both size and morphology. They include large contiguous burned areas, elongated bands following ridges and valleys, and multiple small, fragmented fire spots. With the integration of SNIC segmentation, the classification outputs exhibit markedly improved spatial continuity and boundary clarity. In all sub-figures, the boundaries between burned areas (red) and unburned forest (green) are smooth and coherent, with very few isolated misclassified pixels. Even in regions characterized by rugged terrain, complex forest edges, or strong fragmentation caused by roads and rivers, the burned patches maintain consistent shapes and continuous outlines without apparent breaks or erroneous merging.

Figure 8.

Enlarged burned area maps of 21 forest wildfires in Dali based on the SNIC+RF model. The left panel shows the spatial distribution of the 21 wildfire events, while the right panel presents the corresponding SNIC+RF classification zoom in results. (a–u) display the enlarged burned area maps of the 21 forest wildfires that occurred during the fire season in Dali.

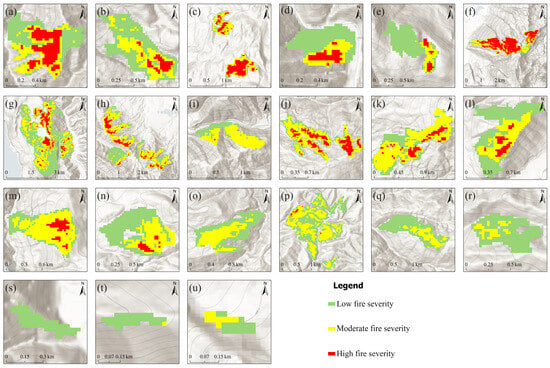

3.4. Mapping of Forest Burn Severity

Figure 9 illustrates the spatial distribution of burn severity for the 21 forest wildfire events in Dali, while Table 5 presents the three severity levels derived from the dNBR-based clustering. According to the classification results, burn severity was divided into low, moderate, and high categories, with corresponding areas of 749.32 ha, 776.70 ha, and 379.29 ha. Overall, moderate-severity burns accounted for the largest proportion of the total burned area, followed by low-severity, whereas high-severity burns covered the smallest area. Across the 21 wildfire sites, the composition of low-, moderate-, and high-severity patches varied substantially. Several fire events were dominated by moderate-severity burns (such as Figure 9i,k,m), while others contained relatively larger proportions of high-severity patches (such as Figure 9a,c,f,j). These differences resulted in diverse spatial configurations of burn severity among the sites, ranging from large, contiguous moderate-severity regions to mosaic-like low-severity patches and localized clusters of high-severity burns.

Figure 9.

Burn severity maps of 21 forest wildfire events in Dali based on dNBR classification. (a–u) present the spatial distribution of three burn severity levels—low (green), moderate (yellow), and high (red)—derived from the dNBR index for each wildfire event.

Table 5.

The dNBR thresholds for fire severity classification.

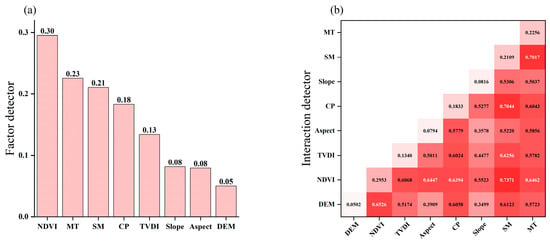

3.5. Factors Influencing Burned Forest Areas

Figure 10 illustrates the explanatory power of eight environmental factors on the spatial variation of wildfire hotspot density in Dali Prefecture, together with their interaction effects. The single-factor detector results (Figure 10a) reveal pronounced differences among variables. NDVI exhibits the highest explanatory power (q = 0.30), indicating that vegetation greenness is the most influential individual driver of hotspot density. This is followed by mean temperature (q = 0.23) and soil moisture (q = 0.21), highlighting the pivotal role of meteorological conditions in regulating regional wild-fire activity. Cumulative precipitation (q = 0.18) and TVDI (q = 0.13) show moderate explanatory strength, whereas topographic factors (slope, aspect, and elevation) have relatively low q-values (<0.10) but remain statistically significant, suggesting that ter-rain exerts a fundamental yet secondary constraint on the spatial configuration of wildfire hotspots. The interaction detector results (Figure 10b) reveal widespread nonlinear enhancement effects, with nearly all bivariate combinations exhibiting markedly higher q-values than their corresponding single-factor contributions. The strongest interactions are observed for NDVI ∩ SM, SM ∩ CP, SM ∩ MT, and NDVI ∩ MT, with q-values ranging from 0.64 to 0.74—far exceeding the explanatory power of any individual factor. Interactions between TVDI and meteorological variables (e.g., TVDI ∩ MT and TVDI ∩ SM) also display substantial enhancement. Although topographic factors show limited individual influence, their interactions with vegetation and meteorological variables fall within the moderate range (approximately 0.40–0.60), indicating that terrain primarily affects hotspot density indirectly by modulating vegetation and hydrothermal conditions.

Figure 10.

Factor and interaction detector results for eight environmental variables influencing wildfire hotspot density in Dali Prefecture. (a) Factor detector results for eight environmental variables influencing wildfire hotspot density; (b) Interaction detector results showing bivariate interaction effects among the eight environmental variables. Abbreviations: Elevation (DEM), Slope, Aspect, NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index), TVDI (Temperature Vegetation Dryness Index), CP (Cumulative Precipitation), MT (Mean Temperature), SM (Soil Moisture).

4. Discussion

4.1. Advantages of Semi-Automatic Training Sample Generation in Burned Area Identification

Compared with traditional approaches that rely on manual sampling or ground-based fire reports, the semi-automatic training sample generation strategy proposed in this study offers substantial advantages for large-scale burned area identification, particularly in scenarios where management authorities require comprehensive, continuous, and spatially detailed information on wildfire damage. In regions such as Dali, where mountainous terrain is highly fragmented and wildfires occur at multiple locations and times, ground patrols, surveillance cameras, and low-altitude UAV platforms can only capture a limited number of representative fire points and cannot provide timely, large-scale coverage of burned area distribution across the entire region [50,51]. Relying solely on these incomplete fire point records for regional burned area interpretation often leads to spatial discontinuities or incomplete identification of fire perimeters. The semi-automatic workflow developed in this study effectively addresses these limitations by enabling systematic identification of candidate burned areas across the whole region. Even without full knowledge of ignition locations, burned extents, or fire progression, the method can extract actual burn scars from multi-temporal satellite imagery, greatly improving the completeness and reliability of regional wildfire event detection. Moreover, by integrating temporal spectral changes, environmental constraints, and forest distribution information, the method effectively suppresses fragmented noise patches that are common in pixel-based classifications, resulting in more coherent, realistic, and reliable burned samples. Although UAV data provide fine spatial detail, their limited flight endurance, small coverage area, and complex image mosaicking procedures constrain their use for large-scale fire mapping [52,53]. Manual interpretation, on the other hand, is labor-intensive and difficult to implement efficiently in rugged mountainous terrain. In contrast, the proposed semi-automatic framework can be fully executed on a cloud platform, offering high efficiency, strong objectivity, and excellent scalability, making it readily applicable to regional and even larger mountainous landscapes [54,55]. Therefore, this method not only significantly improves the efficiency and quality of training sample generation but, more importantly, provides management authorities with comprehensive and accurate fire point information and spatially explicit burned area mapping, thereby delivering robust data support for forest fire prevention, emergency response, and post-fire ecological assessment.

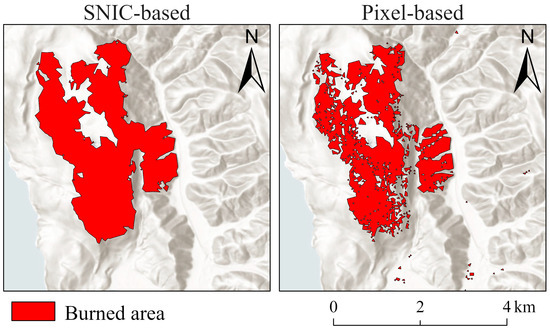

4.2. Effectiveness of SNIC-Based Object-Level Segmentation in Burned Area Identification

As shown in Figure 11, the SNIC-based object-level segmentation markedly improves the reliability of burned area identification compared with the pixel-based approach. In pixel-level classification, large amounts of salt-and-pepper noise occur within and along the edges of burned patches, producing numerous isolated misclassified pixels. This results in fragmented burned patterns that disrupt the spatial continuity of fire scars, blur fire boundaries, and hinder the accurate representation of the actual burned extent [56]. In contrast, the SNIC algorithm aggregates spectrally and spatially similar pixels into coherent objects, effectively reducing noise and producing smoother, more contiguous burned patches that better reflect the true morphology of fire disturbance. The strength of SNIC lies in its ability to suppress artificial pixel-level discreteness while preserving meaningful edge information, thereby avoiding spatial discontinuities introduced by the pixel grid itself. In mountainous regions such as Dali, where terrain is highly variable and vegetation structure is complex, pixel-level noise tends to be amplified, further degrading burned area delineation. The object-based segmentation provided by SNIC effectively mitigates this issue, producing clearer boundaries and more natural patch shapes. Moreover, with an appropriately selected segmentation scale, SNIC avoids over-segmentation while still capturing the irregular geometry of burned areas, thus enhancing both interpretability and visual coherence of the mapping results.

Figure 11.

Comparison between SNIC-based object-level and pixel-based burned area mapping. The left panel shows the SNIC-based object-level classification result, while the right panel presents the pixel-based classification result.

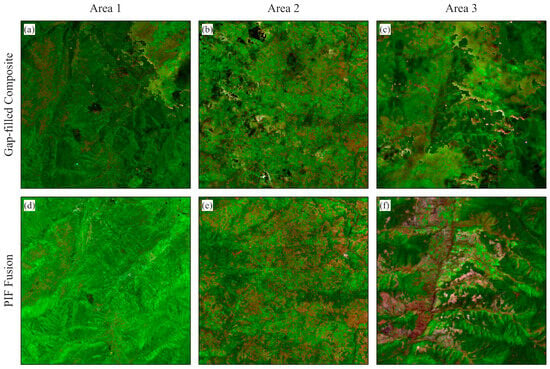

4.3. Significance of Multi-Source Optical Data Fusion for Forest Burned Area Mapping

Forest wildfires are characterised by their abrupt onset, pronounced spatial heterogeneity, and rapid short-term dynamics. These characteristics limit the effectiveness of traditional monitoring strategies that rely solely on a single sensor or on time-series cloud reconstruction approaches. Previous studies have shown that reconstruction algorithms such as HANTS perform well in slowly changing environments [57]; however, for short-lived and high-intensity disturbances such as wildfires, they tend to oversmooth spectral changes, introduce misclassification [58], and weaken the accurate representation of fire progression. Figure 12a–c illustrates the Sentinel-2–dominated gap-filled composites, in which missing or cloud-obscured pixels in Sentinel-2 imagery were supplemented using Landsat 8. Although this approach improves temporal and spatial coverage, noticeable inter-sensor spectral inconsistencies remain, including tonal differences, reflectance discontinuities, and local brightness shifts. These issues blur or fragment key spectral indicators such as dNBR in burned areas, reducing the stability of spectral signals and hindering precise delineation of fire boundaries. In contrast, Figure 12d–f shows the PIFS-based harmonized fusion results. By using spectrally stable ground targets for radiometric calibration, PIFS substantially reduces systematic spectral discrepancies between Landsat 8 and Sentinel-2. The fused imagery exhibits more coherent brightness, tone, and structural consistency, enabling clearer expression of burned features and more continuous fire boundaries. In this study, the high revisit frequency of Sentinel-2 was combined with the stable spectral quality of Landsat 8, and PIFS was applied to enhance the consistency of multi-source datasets. This fusion strategy demonstrates clear advantages over traditional reconstruction methods for wildfire monitoring. The approach enables more accurate and continuous burned area mapping in the cloud-prone mountainous regions of southwest China.

Figure 12.

Comparison of multi-source optical image fusion across three representative areas in Dali Prefecture (Three-band composite: SWIR2, NIR, and RED. (a–c) show Sentinel-2–dominated gap-filled composites, in which missing or cloud-contaminated pixels were supplemented using Landsat 8. (d–f) present the corresponding PIFS-based spectrally harmonized fusion results. A high-resolution version of this figure is available in the online edition of the article.

4.4. Limitations and Future Work

Despite the promising performance of the FS-SNIC-RF framework and the semi-automatic training-sample generation strategy for regional-scale burned-area mapping, several limitations remain and warrant further improvement. First, regarding training data construction, although the semi-automatic sample extraction method substantially improves efficiency and objectivity, a reliable approach for automatically identifying unburned forest samples is still lacking. Simple NDVI-based thresholding cannot fully avoid misclassification, and unburned samples—despite stratified sampling by county—still require manual verification, which restricts full automation and limits scalability to larger regions. Second, in terms of multi-source data fusion, acquiring cloud-free imagery within a short time window is crucial for accurately delineating burned areas. However, the mountainous regions of southwest China experience persistent cloud cover, frequent rainfall, and highly heterogeneous terrain. These conditions often lead to long intervals without usable optical imagery, even when both Landsat 8 and Sentinel-2 are available, and PIFS calibration cannot compensate for the complete absence of valid imagery. This poses significant challenges for continuous fire monitoring during critical periods.

Future research could address these challenges by enhancing the robustness, automation, and intelligence of the workflow. First, deep learning–based spatiotemporal fusion models (e.g., CNN- or Transformer-based architectures [59]) could be explored to improve spectral harmonization and generate high spatiotemporal resolution sequences for near-real-time wildfire monitoring. Second, GAN- and autoencoder-based image enhancement techniques may reduce cloud and smoke interference, thereby improving boundary clarity and increasing the temporal continuity of usable imagery. Additionally, integrating SAR, thermal infrared, and LiDAR data could help overcome the limitations of optical sensors in cloudy, rainy, or nighttime conditions [60]. Finally, from the perspective of intelligent sample construction, incorporating active learning and deep transfer learning has the potential to reduce dependence on manual verification. Implementing uncertainty-based sample quality assessment would further enable automatic identification and updating of low-confidence samples, paving the way for a highly automated and scalable wildfire monitoring system applicable to regional and even broader spatial scales.

5. Conclusions

This study developed the FS-SNIC-ML workflow, which integrates multi-source optical data fusion, semi-automatic sample generation, feature optimisation, and object-based machine learning, providing an accurate, robust, and transferable approach for regional forest burned-area mapping in mountainous environments. The PIFS-based fusion of Sentinel-2 and Landsat 8 enabled the reconstruction of spatially continuous, cloud-free, and gap-free pre- and post-fire imagery under persistent cloud cover and data scarcity, while ensuring spectral consistency and substantially improving the reliability of change detection. The combined SAM–GLCM–PCA–Otsu procedure and county-level stratified sampling ensured representative training data even under limited-sample conditions. dNBR, dNDVI, and dEVI were consistently identified as the most discriminative features, and within the SNIC-supported GEOBIA framework, the RF classifier achieved the best performance, yielding high-accuracy burned-area extraction at the regional scale. GeoDetector results further indicate that wildfire hotspot density is jointly regulated by vegetation conditions, surface moisture, and meteorological factors, among which NDVI, temperature, soil moisture, and their pairwise interactions exhibit the strongest explanatory power with pronounced nonlinear enhancement effects. Overall, the proposed workflow not only enables high-accuracy mapping of forest burned areas but also provides a robust methodological basis for identifying and quantifying the spatial drivers of wildfire occurrence.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.C. and W.K.; methodology, Y.C. and X.Y.; validation, Y.C. and X.Y.; formal analysis, Y.C. and R.W.; investigation, Q.W. and J.Y.; resources, W.K.; data curation, X.Y.; writing—original draft, Y.C. and X.Y.; writing—review and editing, Y.C., R.W. and W.K.; visualization, X.Y.; supervision, W.K.; project administration, W.K.; funding acquisition, W.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by research grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32260391), the Agricultural Joint Foundation of Yunnan Province (2018FG001-059) and the Academician Li Wei Research Station of Yunnan Province (202505AF350082).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely appreciate the technical support and constructive suggestions provided by colleagues and collaborating institutions throughout this study. The authors are also grateful to peers and friends who offered valuable advice during the research. In addition, the authors would like to express their sincere thanks to the editors and anonymous reviewers for their professional guidance and insightful comments during the evaluation and revision of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Optical features used in this study.

Table A1.

Optical features used in this study.

| Features | Formulation | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| dBands | dBlue, dGreen, dNIR, dRed, dSWIR1, dSWIR2, dVV, dVH | / | |

| dNBR | [61] | ||

| dNDVI | [62] | ||

| dDVI | [63] | ||

| dEVI | [64] | ||

| dSAVI | [65] | ||

| dBI | [66] | ||

| dBI2 | [67] | ||

| dRI | [68] | ||

| dRDVI | [69] | ||

| dBAI | [70] | ||

| dNDWI | [71] | ||

Table A2.

Textural metrics used in this study.

Table A2.

Textural metrics used in this study.

| Texture Features | Formulation |

|---|---|

| angular second moment (ASM) | |

| contrast | |

| correlation | |

| entropy | |

| variance | |

| inverse difference moment (IDM) | |

| sum average (SAVG) |

References

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Ding, J.; Shen, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liang, C.; Li, S. Reconstructing Deforestation Patterns in China from 2000 to 2019. Ecol. Model. 2022, 465, 109874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Kou, W.; Ma, X.; Wei, X.; Gong, M.; Yin, X.; Li, J.; Li, J. Estimation of the Value of Forest Ecosystem Services in Pudacuo National Park, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünig, M.; Seidl, R.; Senf, C. Increasing Aridity Causes Larger and More Severe Forest Fires across Europe. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 1648–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Geng, G.; Yan, Z.; Chen, X. Economic Loss Assessment and Spatial–Temporal Distribution Characteristics of Forest Fires: Empirical Evidence from China. Forests 2022, 13, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modica, G.; Silva, J.M.N. Regional-Scale Burned Area Mapping in Mediterranean Regions Based on the Multitemporal Composite Integration of Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 Data. GISci. Remote Sens. 2022, 59, 1678–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, I.; Abrantes, N.; Keizer, J.J.; Vale, C.; Pereira, P. Major and Trace Elements in Soils and Ashes of Eucalypt and Pine Forest Plantations in Portugal Following a Wildfire. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 572, 1363–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, B.; Stephens, S.L. Australia and the United States Have Many Similarities and Differences in Prescribed Fire Management: Learning from Each Other. Fire Ecol. 2025, 21, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Kou, W.; Miao, W.; Yin, X.; Gao, J.; Zhuang, W. Mapping Burned Forest Areas in Western Yunnan, China, Using Multi-Source Optical Imagery Integrated with Simple Non-Iterative Clustering Segmentation and Random Forest Algorithms in Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savitzky, A.; Golay, M.J.E. Smoothing and Differentiation of Data by Simplified Least Squares Procedures. Anal. Chem. 1964, 36, 1627–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, W.; Chen, Y.; Kou, W.; Lai, H.; Sazal, A.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Hu, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, T. The HANTS-Fitted RSEI Constructed in the Vegetation Growing Season Reveals the Spatiotemporal Patterns of Ecological Quality. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 14686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Jia, L.; Menenti, M.; Gorte, B. On the Performance of Remote Sensing Time Series Reconstruction Methods—A Spatial Comparison. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 187, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuvieco, E.; Ventura, G.; Martín, M.P.; Gómez, I. Assessment of Multitemporal Compositing Techniques of MODIS and AVHRR Images for Burned Land Mapping. Remote Sens. Environ. 2005, 94, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hao, S.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chan, K.L. Reconstruction of Daily MODIS 250-m Two-Band Enhanced Vegetation Index Time Series Using Gaussian Process Regression. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 20725–20741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siam, M.R.K.; Staes, B.M.; Lindell, M.K.; Wang, H. Lessons Learned From the 2018 Attica Wildfire: Households’ Expectations of Evacuation Logistics and Evacuation Time Estimate Components. Fire Technol. 2025, 61, 795–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; He, T.; Lyu, Z. Digital Wildfire: The Role of Social Media in Emergency Response during Wildfire Crises. Environ. Hazards 2025, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakkasagi, S.; Goyal, M.K. Are Rapid Onset Drying Events Escalating Forest Fires across India’s Ecoregions? Environ. Res. Lett. 2025, 20, 064004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiede, D.; Sudmanns, M.; Augustin, H.; Baraldi, A. Investigating ESA Sentinel-2 Products’ Systematic Cloud Cover Overestimation in Very High Altitude Areas. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 252, 112163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmeister, F.; Arias-Rodriguez, L.F.; Premier, V.; Marin, C.; Notarnicola, C.; Disse, M.; Chiogna, G. Intercomparison of Sentinel-2 and Modelled Snow Cover Maps in a High-Elevation Alpine Catchment. J. Hydrol. X 2022, 15, 100123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calkin, D.E.; Gebert, K.M.; Jones, J.G.; Neilson, R.P. Forest Service Large Fire Area Burned and Suppression Expenditure Trends, 1970–2002. J. For. 2005, 103, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Li-min, D.; Guo-fan, S.; Lei, T.; Hui, W. Forest Fire Risk Zone Mapping from Satellite Images and GIS for Baihe Forestry Bureau, Jilin, China. J. For. Res. 2005, 16, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Chen, Y.; Xu, B.; Li, W.; Ye, J.; Kou, W.; Xu, W. Post-Fire Forest Ecological Quality Recovery Driven by Topographic Variation in Complex Plateau Regions: A 2006–2020 Landsat RSEI Time-Series Analysis. Forests 2025, 16, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Hu, X.; Qin, X.; Huang, S.; Meng, F. Methodology for Wildland–Urban Interface Mapping in Anning City Using High-Resolution Remote Sensing. Land 2025, 14, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Chen, W.; Wu, Y.; Gao, Z. Monitoring Vegetation Restoration after Wildfires in Typical Boreal Forests Based on Multi-Source Remote Sensing Data. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2024–2024 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Athens, Greece, 7 July 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 581–584. [Google Scholar]

- Cardozo, F.; Pereira, G.; Shimabukuro, Y.; Moraes, E. Analysis and Assessment of the Spatial and Temporal Distribution of Burned Areas in the Amazon Forest. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 8002–8025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franquesa, M.; Rodriguez-Montellano, A.M.; Chuvieco, E.; Aguado, I. Reference Data Accuracy Impacts Burned Area Product Validation: The Role of the Expert Analyst. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, P.D.; Mataveli, G.; Arcanjo, J.D.S.; Dutra, D.J.; Medeiros, T.P.D.; Shimabukuro, Y.E.; Pessôa, A.C.M.; De Oliveira, G.; Anderson, L.O. Regional-Scale Assessment of Burn Scar Mapping in Southwestern Amazonia Using Burned Area Products and CBERS/WFI Data Cubes. Fire 2024, 7, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knopp, L.; Wieland, M.; Rättich, M.; Martinis, S. A Deep Learning Approach for Burned Area Segmentation with Sentinel-2 Data. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Nascetti, A.; Ban, Y.; Gong, M. An Implicit Radar Convolutional Burn Index for Burnt Area Mapping with Sentinel-1 C-Band SAR Data. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2019, 158, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulinan, A.S.; Cho, Y.; Park, M.; Park, S. Rapid Wildfire Damage Estimation Using Integrated Object-Based Classification with Auto-Generated Training Samples from Sentinel-2 Imagery on Google Earth Engine. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 126, 103628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Sun, X.; Dong, G.; Li, Y.; Ma, M. Forest Fire Mapping Using Multi-Source Remote Sensing Data: A Case Study in Chongqing. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zheng, Y.; Dalponte, M.; Tong, X. A Novel Fire Index-Based Burned Area Change Detection Approach Using Landsat-8 OLI Data. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 2020, 53, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, E.K.; Colkesen, I.; Kavzoglu, T. A Comparative Assessment of Canonical Correlation Forest, Random Forest, Rotation Forest and Logistic Regression Methods for Landslide Susceptibility Mapping. Geocarto Int. 2020, 35, 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khechba, K.; Belgiu, M.; Laamrani, A.; Stein, A.; Amazirh, A.; Chehbouni, A. The Impact of Spatiotemporal Variability of Environmental Conditions on Wheat Yield Forecasting Using Remote Sensing Data and Machine Learning. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2025, 136, 104367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Li, M.; Lai, H.; Kou, W.; Chen, Y.; Chen, B. Utilizing Multi-Source Data and Cloud Computing Platform to Map Short-Rotation Eucalyptus Plantations Distribution and Stand Age in Hainan Island. Forests 2024, 15, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar, S.; Parida, B.R.; Pandey, A.C. Landsat-8 and Sentinel-2 Based Forest Fire Burn Area Mapping Using Machine Learning Algorithms on GEE Cloud Platform over Uttarakhand, Western Himalaya. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2020, 18, 100324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, G.; Silva, J.M.N.; Di Fazio, S.; Modica, G. Integrated Use of Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 Data and Open-Source Machine Learning Algorithms for Land Cover Mapping in a Mediterranean Region. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 2022, 55, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhijie, X.; Jiang, W.; Ling, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Peng, K.; Song, J.; Sun, J.; Li, X. Monitoring the Annual Dynamics of Mangrove Forests in the Guangxi Beibu Gulf of China from 2000 to 2023 via the SNIC-RF Algorithm Using the GEE Platform. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2025, 18, 2558920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhao, F.; Wang, Y.; Huang, X.; Ye, J. Seasonal Differences in the Spatial Patterns of Wildfire Drivers and Susceptibility in the Southwest Mountains of China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 869, 161782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Long, Q.; Lin, S.; Hu, Z.; Zeng, Y. Carbon Neutralization in Yunnan: Harnessing the Power of Forests to Mitigate Carbon Emissions and Promote Sustainable Development in the Southwest Forest Area of China. Mitig. Adapt. Strat. Glob. Change 2024, 29, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, G.; Wang, K.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y. Forest Fire Risk Prediction Based on Stacking Ensemble Learning for Yunnan Province of China. Fire 2024, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.Q.; He, L.-Y.; Su, W.-H.; Zhang, G.-F.; Wang, H.-C.; Peng, M.-C.; Wu, Z.-L.; Wang, C.-Y. Regeneration, Recovery and Succession of a Pinus Yunnanensis Community Five Years after a Mega-Fire in Central Yunnan, China. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 294, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Li, W.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, M.; Wang, C.; Sha, L.; Liu, Y.; Song, Q.; Fei, X.; Jin, Y.; et al. Responses of the Carbon Storage and Sequestration Potential of Forest Vegetation to Temperature Increases in Yunnan Province, SW China. Forests 2018, 9, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.; Chen, B.; Yin, X.; Wang, G.; Wang, X.; Yun, T.; Lan, G.; Wu, Z.; Yang, C.; Kou, W. Dry Season Temperature and Rainy Season Precipitation Significantly Affect the Spatio-Temporal Pattern of Rubber Plantation Phenology in Yunnan Province. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1283315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]