Highlights

What are the main findings?

- DEM–PCA with L8 + RF produced the top performance (OA ≈ 79%, κ ≈ 0.71), with statistically significant gains over other feature sets (Friedman/post hoc).

- Gains were class-dependent: the most confounded PEUs improved the most, while several auxiliaries added little; prioritizing DEM derivatives and first PCs is recommended.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- Discriminating vegetation sub-classes in heterogeneous rangelands is difficult with multispectral data alone. Classifying the landscape into homogeneous PEUs enables more reliable biodiversity assessment, systematic landscape management, and operational monitoring.

- Selecting auxiliaries can be costly and time-consuming. Our results indicate that DEM-derived terrain variables and PCA components should be prioritized with L8 + RF to improve PEU mapping accuracy, helping researchers concentrate efforts towards the area that yields the greatest gains and enabling more efficient, transferable workflows.

Abstract

Mapping Plant Ecological Units (PEUs) support sustainable rangeland management. Yet, distinguishing them from multispectral imagery remains challenging due to high intra-class variability and spectral overlap. This study evaluates the contribution of auxiliary data layers to improve PEU classification from Landsat-8 OLI imagery in semi-arid rangelands of northeastern Iran. A random forest (RF) classifier was trained using field samples and multiple feature combinations, including spectral indices, topographic variables (DEM, slope, aspect), and principal component analysis (PCA) components. Classification performance was assessed using overall accuracy (OA), kappa coefficient, and non-parametric Friedman and post hoc tests to determine significant differences among scenarios. The results show that auxiliary features consistently enhanced classification performance as opposed to spectral bands alone. Integrating DEM and PCA layers yielded the highest accuracy (OA = 79.3%, κ = 0.71), with statistically significant improvement (p < 0.05). The findings demonstrate that incorporating topographic and transformed spectral information can effectively reduce class confusion and improve the separability of PEUs in complex rangeland environments. The proposed workflow provides a transferable approach for ecological unit mapping in other semi-arid regions facing similar environmental and management challenges.

1. Introduction

Satellite images form the basis of land cover and vegetation mapping and monitoring, owing to periodic and accurate data [1,2]. Land-cover mapping derived from remote sensing (RS) and satellite imagery supports the monitoring and management of natural resources, vegetation, and landscapes, and provides a basis for assessing and quantifying ecosystem services [3,4,5,6,7]. Plant Ecological Units (PEUs) are defined as the potential vegetation communities occurring at a landscape or site that differ from other vegetated land covers in their potential to generate determined types and quantities of vegetation [8]. Therefore, PEUs provide a standard reference for monitoring and land management [9]. Even though the notion of PEUs in natural resource and land cover assessment and monitoring is commonly accepted [10], the application and importance of PEUs still need to be better understood. The identification of PEUs remains challenging in the landscape [11], despite five decades of application of satellite image processing for monitoring and mapping land cover and vegetation. In general, PEUs have a complex spatial structure and quite similar spectral behavior, which results in reduced separability and classification inter-class [12]. Thus, these heterogeneous plant communities are challenging to classify using remote sensing satellite images [13]. Processing and classifying optical RS imagery for trustworthy and accurate PEU mapping in heterogeneous landscapes are challenging when relying solely on reflectance data, largely due to the spectral similarity among PEUs [14]. This difficulty is exacerbated in arid rangelands, where soil background often dominates the canopy reflectance signal [15].

In the literature, numerous methods have been presented to overcome the difficulty of distinguishing land cover features with overlapping spectral characteristics. Particularly, the incorporation of auxiliary geospatial data in addition to satellite reflectance imagery has been recommended to facilitate distinguishing land cover features from satellite data [6,16,17,18,19]. However, PEUs behave spectrally alike and due to low inter-class separability, form complex spatial structures within the heterogeneous and semi-arid region landscape [13]. The production of reliable and accurate PEU maps in heterogeneous landscapes is typically based on the classification of raw satellite imagery. Therefore, the choice of input data and auxiliary data to enhance the precision of PEUs classification is still a controversial topic [20]. Many types of auxiliary geospatial data can be potentially fused to improve and enhance the sub-land cover classification and mapping performance. Usual data sources include (1) topographic data such as digital elevation models (DEMs), and (2) vegetation indices, owing to their potential to target specific land cover and vegetation classes. Also, (3) linear transformation techniques such as principal component analysis (PCA) and tasseled cap transformation (TCT) proved to be efficient auxiliary data sources in increasing and enhancing land cover and vegetation mapping accuracy [21,22].

While the use of complementary auxiliary data has been well-established in increasing the classification accuracy of entire satellite images, the process of detecting and classifying vegetation types is more complex. Since PEUs are a sub-class of grassland vegetation, they are very similar in their spectral reflectance, which is an intricate classification task, especially when Landsat OLI-8 data are used for mapping. So far, the impact of complementary auxiliary datasets on the accuracy of PEU classification for rangeland monitoring and assessment has not been quantitatively assessed, particularly in arid landscapes. To address this gap, we investigate how such auxiliary datasets influence PEU classification performance. A heterogeneous landscape with four dominant and clearly distinguishable PEUs was selected as the study area. The focus is placed on enhancing mapping and classification accuracy by incorporating geospatial auxiliary data derived either from the reflectance bands of the original imagery or from independently produced sources. Accordingly, the main objective is to improve PEU mapping through combinations of the following complementary auxiliary data types, namely (1) spectral vegetation indices, (2) linear transformation methods, and (3) topographic factors derived from DEM data, while assessing their respective strengths and limitations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Region

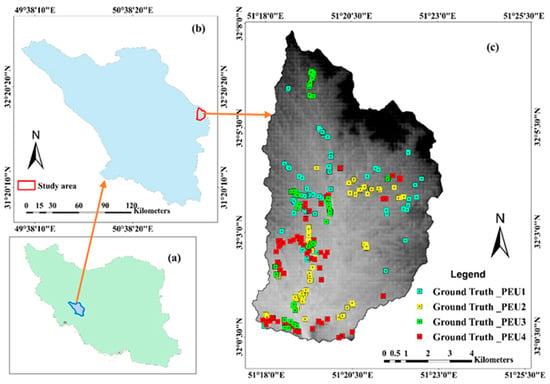

The study area is located in southwestern Iran (Figure 1). This landscape covers an area of 7736 ha with an average elevation of 2697 m a.s.l., expanding from 32°03′56″ to 32°04′05″N and 51°18′53″ to 51°19′12″E. Its climate is characterized by dry summers and cold, temperate winters; the average 50-year rainfall in this region is about 200 mm. Thanks to appropriate management strategies, harvesting intensity is low, and despite the low rainfall (200 mm annually), this region has good conditions for plant growth, with shrubs and perennial grasses forming the dominant vegetation type [23].

Figure 1.

The position of the region: (a) on the Iran border; (b) on the province border; (c) study area border (Marjan). A set of recorded points from PEU were divided into two groups: training data (60%) for classifying PEU and testing data (40%) for evaluating of PEU classified maps [23].

2.2. Field Measurements of PEUs

Four PEU types were identified in the region: PEU1 (As ve; Astragalus verus Olivier), PEU2 (Br to; Bromus tomentellus Boiss.), PEU3 ii; Scariola orientalis Soják), and PEU4 (As ve–Br to; Astragalus verus–Bromus tomentellus). Vegetation cover was quantified using a physiognomic–floristic classification approach to determine the dominant types of each PEU. Each PEU was sampled with three replicate plots, and within each plot, vegetation cover percentage was estimated along three 100 m transects. Sampling points were distributed as evenly as possible across the study area (Figure 1).

Alongside each transect, 30 quadrats were located, which were made of 360 sampling quadrats in total. The sampling followed a systematic random approach: the first node was selected systematically, while the remaining nodes were randomly distributed along the transect. In each square, the percentage cover of each species was estimated to characterize PEU composition. The attributes of the PEUs are displayed in Table 1 [15].

Table 1.

Selected PEUs and their vegetation characteristics in the region.

2.3. Satellite Data

We first downloaded Landsat OLI-8 (Landsat Operational Land Imager) images acquired on 10 June 2018. Images were downloaded from the USGS (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/ (accessed on 21 March 2021)). This date approaches the peak in the phenological and productivity development of the major PEUs in the region, which are critical for accurately classifying land-cover types. Bands from Landsat 8 that are uninformative to the vegetation analysis (such as cirrus clouds, coastal aerosol, and thermal bands) were removed. All Landsat 8 bands were surface-reflectance-corrected by the USGS.

2.4. Methodology

2.4.1. Image’s Pan-Sharpening

Spatial resolution of Landsat OLI-8 bands varies from 15 m (panchromatic band) to 30 m (multispectral bands). To take advantage of the panchromatic band’s superior spatial resolution and broader spectral sensitivity, the 30 m multispectral bands (bands 2–7) were enhanced to 15 m through pan-sharpening with the panchromatic band (band 8) to improve PAU classification accuracy. This transformation was employed through the IHS (intensity–hue–saturation) algorithm. The IHS algorithm may have more distortion than other algorithms, such as Indusion, discrete wavelet transform (DWT), and the SFIM fusion technique, but it provides good accuracy for multispectral satellite images due to the use of RGB bands [24].

2.4.2. Auxiliary Geospatial Data

In the first step, the pan-sharpened bands (two to eight bands) were stacked into a set of reflection bands. We calculated different auxiliary dataset, such as slope-based vegetation indices (NDVI, Ratio, RVI, EVI, TVI, CTVI, SARVI, TTVI, TSAV, MSAVI2, AVI), distance-based indices (SAVI, TSAVI1, TSAVI2, MSAVI1, PVI, PVI1, PVI2, PVI3, DVI, WDVI), linear transformation methods, such as PCA and tasseled-cap transformation (TCT), and topographic factors of DEM, slope, and aspect to improve PEUs mapping. Then, in the second step, the auxiliary data that had the greatest impact on increasing classification accuracy were extracted, and formulas and descriptions for the indices are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Specifications of auxiliary dataset features used for PEU mapping.

- Vegetation indices of the Modified Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index (MSAVI), as a representative of soil-adjusted vegetation indices.

- Enhanced vegetation index (EVI).

- Proportion vegetation (PV).

- Principal component analysis (PCAs).

- Tasseled-cap transformation (TCT).

- Digital elevation model (DEM).

PCA was applied to extract the first three principal components (PC1, PC2, and PC3) from the reflectance bands. The PCA products were generated using spectral information and explained more than 99% of the information and data variation.

The tasseled-cap three-dimensional transformation was applied to the six bands of OLI-8 data (two to eight, excluding the thermal bands, Cirrus, and coastal bands) to merge spectral data into a few bands of greenness, brightness, and wetness, with little loss of information (Table 2). Greenness is determined by a high reflectance in the near-infrared band and a high absorption in visible bands, which considerably correlates with healthy biomass and leaf index [25]. Brightness is the weighted sum of all reflective bands, representing natural, artificial features, bare or semi-bare soil. Wetness is sensitive to plant and soil moisture [26]. The greenness, brightness, and wetness indices were calculated using equations listed in Table 2.

Given that topography affects the spatial distribution of numerous PEUs, a 15 m resolution DEM was included as an additional predictor in the classification. The DEM data was extracted from the SRTM (Shuttle Radar Topographic Mission), and 30 m DEM was then merely rescaled to 15 × 15 m to be used together with reflectance-pan-sharpened multispectral Landsat-8 OLI data. For this, the bilinear interpolation method was used. Bilinear interpolation uses the value of the four nearest input cell centers to determine the output cell value using a weighted average. Then, the output cell size (resolution) was determined to be 15 m in both X and Y dimensions. Details of the auxiliary dataset used to increase the PEU maps’ accuracy are presented in Table 2.

2.4.3. Sampling PEUs

After the field survey and the introduction of four dominant PEU groups in the area, a total of 300 geographic (X,Y) locations were recorded using a handheld GPS for four PEUs (Figure 1c). The sampling points were distributed into two groups: “training points” to be classified (60%) and “test points” to validate the classification results (40%) [27]. The train–test split is a common machine learning strategy in which the available dataset is partitioned into two subsets: a training set used to fit the model and a test set used to evaluate its performance on independent data. This procedure reduces overfitting and allows the assessment of the model’s ability to generalize to real-world conditions. Typical splits include 70:30 or 60:40 between training and testing. In this study, a 60:40 ratio was adopted to better accommodate the heterogeneous rangeland conditions, following the recommendations in [24].

2.4.4. PEU Mapping Using Reflectance Bands and Auxiliary Data

We first classified pan-sharpened reflectance bands of Landsat OLI-8 images based on training sample sites (points). Then, to reveal the effects of auxiliary data on enhancing the accuracy of PEU mapping, each auxiliary band was added to the classification multispectral bands separately, and the images were reclassified using the same field-gathered training data used in the previous phase to avoid sampling effects. It should be noted that the joint effects of auxiliary data in increasing classification accuracy were also tested, which were added as joint auxiliary data if the overall accuracy of the maps increased, such as DEM auxiliary data along with PCA (PC1, PC2, and PC3), which is referred to in the text as DEM-PCA.

Random forest (RF) was selected for PEU classification after an initial comparison with several alternative algorithms (maximum likelihood, minimum distance, neural networks, and RF) [23]. RF, originally proposed by Breiman [28], is an ensemble machine learning method that constructs a large number of decision trees (typically 500–1000) and aggregates their outputs. Each tree is trained on a bootstrap sample of the data using a randomly selected subset of predictor variables, and the final class assignment is obtained by majority vote across all trees [29,30].

The increase in PEU map accuracy was evaluated at the end of each classification process using the confusion matrix, followed by estimated OA (overall accuracy), OK (overall kappa), UA (user’s accuracy), and PA (producer’s accuracy). The users’ and producers’ accuracies of each PEU class were measured to determine the best classification accuracy after applying different auxiliary data. The equations used to calculate the OA (1), OK (2), UA (3), and PA (4) are given as follows:

where n is the total number of all classifications; i,j, is an element, located at the ith row and jth column of the confusion matrix; UAi represents UA of class i; PAj represents UA of class j.

2.4.5. Statistical Analysis of Adding Values of Multiple Auxiliary Data

To display the efficiency of the added values of auxiliary data on the PEU mapping accuracy of the reflectance bands, in addition to the customary values of the OA and OK index, we used the Friedman test with the post hoc comparison of means following Demsar [31]. This test measures different PEUs in terms of UA, PA, and KIA (kappa index of agreement) values, which were regarded as repeated measures over multiple datasets used for classification.

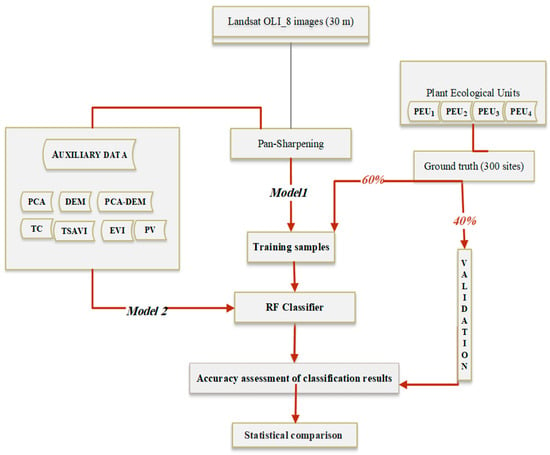

Figure 2 illustrates the methodology applied in this study to evaluate the results of different auxiliary datasets on PEUs’ mapping accuracy. First, the 30 m bands (two to seven) were pan-sharpened using the 15 m panchromatic band (band 8) of the OLI-8 sensor. Then, the complementary auxiliary layers of MSAVI, EVI, PV, PCAs, TCT derived from reflectance bands, and DEM were used to develop collection datasets to enhance the PEU mapping accuracy. The samples collected were divided into training points (60%) for classification and test points (40%) for accuracy assessment. Following that, the resulting map from the classification of reflectance bands, as well as reflectance bands that complemented with each auxiliary data, were validated using test points. Finally, a statistical analysis was conducted to evaluate the contribution of each auxiliary data source to the classification beyond the reflectance bands.

Figure 2.

The framework of mapping PEUs using reflectance bands of Landsat-8 OLI data and auxiliary data to enhance mapping accuracy.

3. Results

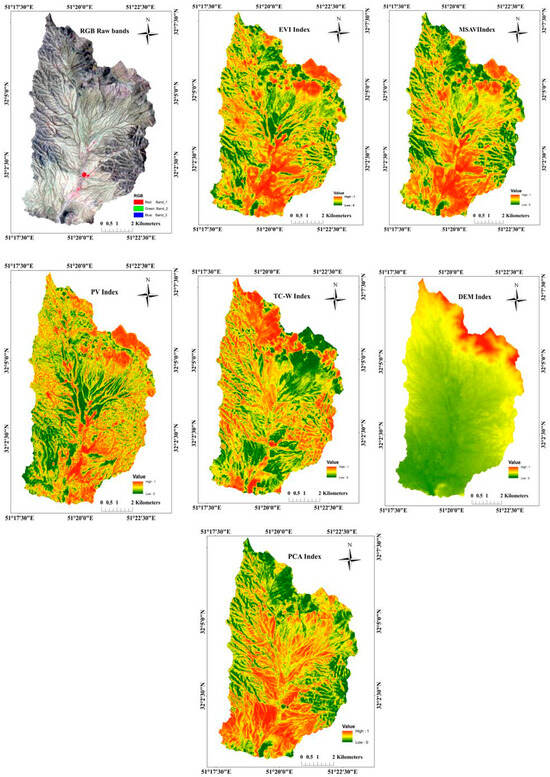

3.1. Reflectance Bands and Auxiliary Data Used for Classification

Figure 3 shows the pan-sharpened bands (two to seven bands) as a false-color (RGB) map along with the auxiliary datasets used to enhance the accuracy of PEU mapping. These data include EVI, MSAVI, PV, TASSCAP-wetness (TC-W), and PCAs, which were all derived from Landsat 8-OLI data and scaled to a 15 × 15 m DEM.

Figure 3.

Auxiliary dataset used to enhance PEU classification accuracy.

3.2. Impact of Auxiliary Data on PEU Classification Accuracy

Table 3 presents the confusion-matrix results used to evaluate PEU classification accuracy, obtained by comparing the test points with the classification maps derived from the reflectance bands and auxiliary data. The table reports UA, PA, and KIA for each PEU, as well as the overall accuracy (OA) and overall kappa (OK) for each classification. The results show that since pan-sharpened reflectance bands were applied, PEU1 had the highest PA (78%), UA (88%), and KIA (71%). However, PEU3 had the lowest PA (56%), UA (56%), and KIA (40%). The OK was 52 and the OA 65%. Adding the auxiliary data to the reflectance bands led to an enhancement in classification accuracy. The auxiliary data effect showed that PCAs-DEM returned the highest OK (71%) and OA (79%). PEU1 had the highest PA (87%), UA (90%), and KIA (82%), and PEU4 had the lowest PA (69%), UA (74%), and KIA (58%), while PCA-DEM auxiliary data together with reflectance bands were used for classification. PEU1 had the highest PA, UA, and KIA in almost all auxiliary data, but in contrast, PEU4 had the lowest PA, UA, and KIA.

Table 3.

Error matrix result table. Summary of the best PEU classification accuracy by different auxiliary data.

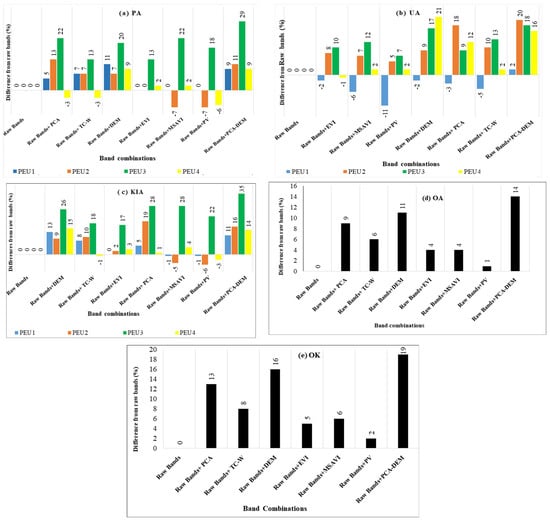

The effects of different auxiliary datasets on the OLI-8 image bands, and their contribution to improving PEU classification accuracy, are summarized in Figure 4. As shown in Figure 4a, most PEU classification maps benefit from auxiliary data by up to 29%, although some combinations lead to accuracy losses of up to 7%. PEU3 gains markedly from all auxiliary datasets in terms of PA, whereas MSAVI and PV reduce the PA of PEU2 by about 7%. Similarly, PV, TS-W, and PCA decrease the PA of PEU4 by up to 6%. PEU1 is largely neutral to some auxiliary datasets but still benefits from most of them, with PA increases of up to 11%. Overall, the identification of PEU2, PEU3, and PEU4 generally improves when auxiliary data are added to the reflectance bands, particularly with respect to PA.

Figure 4.

Effects of different auxiliary data on PEU classification accuracy: (a) PA, (b) UA, (c) KIA, (d) OA, and (e) OK.

As shown in Figure 4b, all PEUs except PEU1 benefit substantially from the auxiliary data, with UA gains of up to 21%. PEU3 and PEU2 show consistent improvements across all auxiliary datasets. In contrast, most auxiliary data reduce the UA of PEU1 by up to 11%, except for PCAs-DEM, which increases its UA by 2%. PEU4 is only slightly negatively affected by EVI, with a 1% decrease in UA.

As indicated in Figure 4c, most PEU classifications improve their KIA by up to 35% when auxiliary data are included, although some combinations lead to decreases of up to 6%. PEU3 benefits markedly from all auxiliary datasets. In contrast, MSAVI and PV reduce the KIA of PEU1 by about 1% and of PEU2 by up to 6%, while PEU4 is negatively affected by PV and TC-W by up to 3%. A side-by-side comparison between the pan-sharpened reflectance bands and the auxiliary datasets shows that the latter increased OA by 1–14% (Figure 4d) and OK by 2–19% (Figure 4e). Among all PEU classification maps, the PCAs-DEM combination yields the highest overall accuracy (+14%) and OK (+19%).

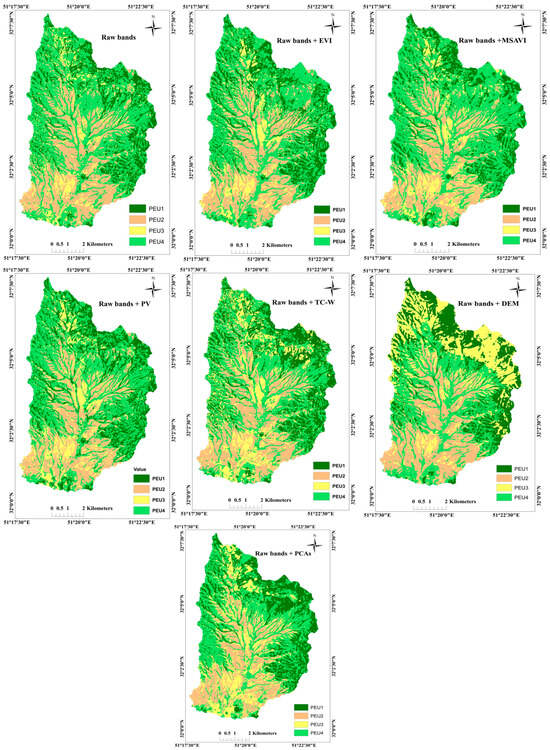

Figure 5 shows the PEU classification maps obtained with the RF classifier using pan-sharpened bands and auxiliary data, including vegetation indices (EVI, MSAVI, PV), image transformation products (TC-W, PCAs), and the DEM-derived topographic factor. Across these maps, the spatial distribution of PEUs is broadly similar: PEU2 is mainly concentrated in the central, flatter parts of the study area, whereas PEU1 and PEU4 occur predominantly on steeper slopes at higher elevations (see DEM in Figure 3). PEU3 is widespread and occurs across almost the entire study area.

Figure 5.

PEU classification maps using reflectance bands and complementary auxiliary datasets (EVI, MSAVI, PV, TC-W, PCAs, and DEM).

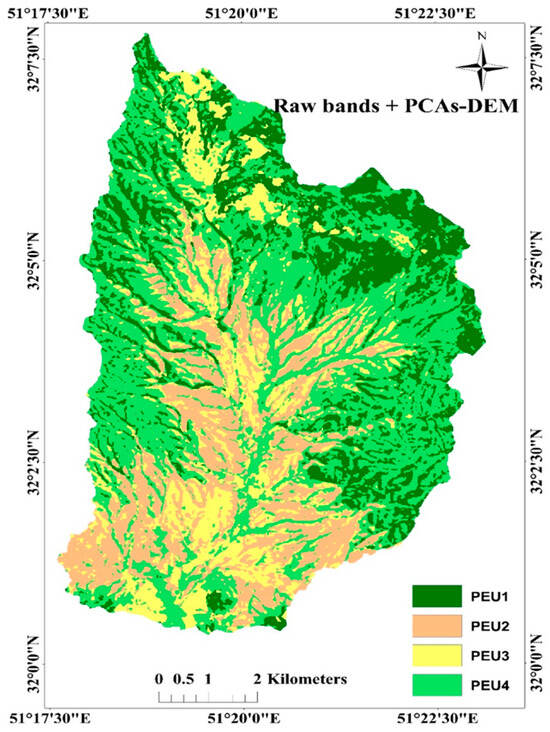

Figure 6 shows the classification map obtained from the reflectance bands combined with PCAs-DEM, which achieved the highest OK (71%) and OA (79%). In this map, PEU4, dominated by shrub–tall grass communities, covers about 44% of the area. In contrast, PEU3, characterized by semi-shrub vegetation, occupies only 16%, while PEU2 (tall grass) and PEU1 (scrubby vegetation) account for 18% and 20% of the area, respectively.

Figure 6.

PEU mapping resulting from pan-sharpened bands and PCAs-DEM as auxiliary data, which revealed the highest OK accuracy (71%) and OA (79%).

3.3. Statistical Comparison

The UA, PA, and KIA for PEU classes were calculated and compared using Friedman’s test with the corresponding post hoc analysis [15,23]. To reveal the benefit of the auxiliary data on PEU classes. The results of the auxiliary data comparison using Friedman’s test indicated that PCAs-DEM and DEM displayed statistically significant effects on PEUs classification (p < 0.05), whereas vegetation indices and TCT did not show a significant added value to the reflectance data for PEU classification (Table 4).

Table 4.

Results of statistically significant comparison (p < 0.05) between the accuracy of PEUs and auxiliary data.

4. Discussion

Although field surveys are highly effective for accurate identification and classification of PEUs, they are limited by personnel, logistical, and budget constraints, which hinder their ability to deliver repeated and simultaneous in situ observations over heterogeneous landscapes. This study examined whether the pan-sharpened Landsat bands alongside auxiliary datasets are adequate to classify PEUs across heterogeneous rangelands. In this study, the PEUs’ classification is based on the premise that each PEU class results from a distinct combination of dominant species and environmental ecological effects applied to distinguish the PEU classes. Four PEU types, namely PEU 1 (As ve (Astragalus verus Olivier)), PEU 2 (Br to (Bromus tomentellus Boiss)), PEU 3 (Sc or (Scariola orientalis Sojak)), and PEU 4 (As ve- Br to (Astragalus verus Olivier_ Bromus tomentellus Boiss), were identified in the region.

We used Landsat OLI 8 images in this study. Owing to their high spatial and temporal resolution, these satellite images have proven useful for land-use and land-cover mapping [32]. However, the PEU classification is more complicated due to the similar spectral behavior of PEUs and the intricate spatial structure of the landscape. Nevertheless, 30 m spatial resolution bands likely lead to complex pixels and consequently low classification map precision, especially at the sub-class land cover, i.e., PEUs. In this method, many of the pixels were assigned to classes that were different from those of the adjacent membership and usually exploit only spectral information. Therefore, the PEUs showed nonhomogeneous coverage, which makes it difficult to separate PEU classes. Thus, to circumvent the problem and reduce the mixed pixel effects, the 30 m resolution bands (bands 2 to 7) were pan-sharpened using the panchromatic band with a 15 m resolution (band 8) and IHS transformation algorithm. A suite of classification algorithms has been explored for vegetation mapping. However, their success and efficiency depend on multiple factors, such as satellite images, the classification system, the characteristics of the study area, and the use of auxiliary datasets [33].

In this study, pan-sharpened Landsat OLI-8 images were classified using an RF algorithm. This approach is well-suited to improving PEU classification in highly fragmented, heterogeneous vegetation communities with spectrally similar features [32,34]. Previously, Lu et al. [35] showed that, when relying solely on spectral bands, the maximum likelihood classification (MLC) algorithm can outperform other traditional and some machine learning classifiers for land-cover mapping. However, once auxiliary datasets are incorporated, machine learning methods generally yield superior classification results compared with MLC. RF, in particular, operates through recursive subsetting, partitioning the training data into increasingly homogeneous groups [29]. The relatively high performance of RF in our case indicates substantial intra-class variability, for which this recursive partitioning strategy is especially effective [36,37].

The Roles of Reflectance Bands and Auxiliary Dataset Features

We used two models for PEU classification of arid rangelands. The first model includes only pan-sharpened bands (two to eight reflectance bands) from Landsat OLI-8 images. The overall classification accuracy (65%) and OK (52%) obtained in the first model (Table 3) indicated that the reflectance bands of Landsat OLI_8 images were still the most significant feature in PEUs classification. According to Table 3, PEU1 had the highest KIA (71%), but PEU3 had the lowest KIA (40%).

The second step is based on auxiliary data complementing the reflectance data. While the development of an auxiliary dataset is often time-consuming, it is the most effective way to identify and determine auxiliary datasets to improve the PEU classification accuracy in heterogeneous landscapes. This research introduces an appropriate auxiliary dataset, including topographic data such as DEM, vegetation indices such as MSAVI, EVI, and PV, and linear transformation methods such as PCAs and TC-W, which are effective in enhancing PEU mapping accuracy. The results of the second step showed that combinations of different auxiliary data could enhance OA and OK classification (1–14% and 2–19%, respectively). As opposed to using only reflectance bands, nearly all of the auxiliary data improved classification accuracy. As indicated in Figure 4d,e, among the auxiliary data, vegetation indices such as MSAVI, EVI, and PV have the least positive effect on classification precision. The vegetation indices are normally derived from red and infrared bands. These two bands are already exploited when reflectance data are used. Therefore, less improvement is observed in the classification accuracy when vegetation indices are applied. Meanwhile, vegetation indices (e.g., MASVI and PV) negatively affect the classification accuracy of PEU2 and somewhat PEU4. The role of PEU phenology should also be noted. For instance, the growth season of PEUs with dominant grass species (Br to) starts earlier than that of other PEUs in the study area, while the growth season of PEUs with dominant shrub species (e.g., As ve and Sc or) starts with a significant delay relative to other PEUs. In addition, due to a mild grazing of the study area, PEU2 is more even and uniform than the other PEUs (e.g., PEU1 and PEU3), making it more distinguishable in the images.

In contrast to vegetation indices, the topographic factor (DEM) and linear transformation methods of reflectance bands, i.e., PCA and TC-W, yielded the highest classification accuracy and had the strongest impact on the accurate identification of PEUs. Tasseled-cap transformation (TCT) was derived from bands 2–7 to condense the spectral information into a few components with minimal loss of information. While most vegetation indices only combine the red and near-infrared bands, these bands are also embedded within the tasseled-cap components together with additional spectral information. This likely explains why the TCT produced a larger improvement in classification accuracy than the vegetation indices.

Figure 4a–c illustrates that PEU3 substantially profits from all the auxiliary data. The classification result based on the reflectance data and the combination of DEM-PCAs auxiliary data has enabled us to easily separate PEU3 from other PEUs, with the greatest gain in accuracy compared with reflectance bands (35%). It seems that these two data layers of the auxiliary dataset (DEM-PCAs) reduced the effects of bare soil reflectance, thus presenting purer pixels of this PEU.

Because PEUs are distributed differently across the study area, the DEM-derived topographic variable proved to be a thematic layer that significantly improved classification. PEU3 is typically characterized by a scattered and irregular pattern, with large patches of bare soil and open spaces between PEU patches, ranging from a few square meters to, in some cases, several tens of meters. The presence of these bare areas, and their influence on the reflectance recorded by the sensor, likely reduced the accuracy of the PEU maps. Consequently, the spatial configuration of PEUs appears to play an important role in driving intra-class spectral variability. In addition, the purpose of PCA is to reduce the number of dimensions by gathering the most useful variations. When considering the first three PCAs, more than 99% of spectral information is presented, thereby reducing noise and improving classification accuracies [36]. Likewise, it seems that these data compensate for the effects of bare soil reflectance on the received signals by the sensors of the raw bands and present more pure pixels associated with PEU3.

PEU4 comprises two dominant vegetation types (As ve and Br to) with contrasting life forms and canopy structures, which results in distinct spectral responses and, consequently, lower classification accuracies. The tested vegetation indices were unable to effectively capture or correct these discrepancies, whereas auxiliary data such as DEM and PCA-DEM had a substantial positive impact on the kappa index for PEU4. As noted earlier, PEUs differ in their spatial distribution, making topographic variables particularly valuable for improving classification. As shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6, PEU2 is mainly concentrated in flat plains, whereas PEU1 and PEU3 occur predominantly on steeper slopes, and PEU4 is more evenly distributed across the entire area. Vegetation indices generally had neutral or even negative effects on the classification of PEU1. Given its dense canopy cover and the resulting abundance of pure pixels, additional vegetation indices are not strictly necessary for PEU1. In contrast, the other PEUs (especially PEU2, PEU3, and PEU4) exhibit greater variability in canopy reflectance due to shrubby dominance and compositional heterogeneity. In these cases, the sensor records mixed signals from both soil and vegetation, increasing the proportion of mixed pixels and, ultimately, the classification error rate.

The PEU classification maps were validated using ground-truth data (test points) and assessed by computing OA and OK (Figure 6). The classification based on pan-sharpened bands combined with PCAs-DEM achieved the highest performance, with an OA of 79% and an OK of 71%. According to the land-use/land-cover (LULC) classification system developed by Anderson et al. [38], nine major classes are typically distinguished from satellite imagery: built-up land (Urban), rangeland, agriculture, forest, wetland, water, tundra, barren land, and perennial snow, each of which can be further subdivided into sub-classes. Most land-cover mapping efforts have focused on these main classes, reporting, for example, OA values of 50–74% in Macintyre [39], 75.1% in Pflugmacher [40], 76% in Feng [19], and 72% in Castillejo–Gonzalez [37]. In contrast, the present study targets rangeland vegetation sub-classes (plant ecological units, PEUs). For such vegetation sub-classes, one expects more similar spectral responses (low inter-class separability) and a more intricate spatial structure, making their discrimination considerably more challenging. Against this background, the OA of 79% obtained here for PEU mapping can be considered highly satisfactory.

5. Conclusions

Accurately delineating PEUs from medium-resolution multispectral imagery remains challenging due to spectral similarity among vegetation types and spatial heterogeneity in semi-arid landscapes. This study demonstrated that augmenting pan-sharpened Landsat OLI-8 bands with carefully selected auxiliary variables substantially enhances PEU classification performance. In particular, the combination of DEM-derived topographic information and PCA components yielded the most consistent gains when used with an RF classifier. These results underscore that feature design matters as much as the base imagery: not all auxiliary layers contribute equally, and some offer little or no benefit. As a practical recommendation, we advocate prioritizing terrain derivatives (elevation, slope, aspect) and low-dimensional spectral transformations (first PCs) before adding additional indices or ancillary layers. This work provides an operational pathway for PEU mapping in semi-arid rangelands and can inform ecological monitoring and management. Future research should assess temporal robustness, adopt spatially explicit validation, compare additional learners and feature-selection strategies, and evaluate transferability to other regions. Together, these steps will further strengthen the reliability and scalability of PEU maps derived from satellite RS.

Author Contributions

Methodology, A.E. and M.A.; conceptualization, A.E. and M.A.; software, M.A.; validation, A.E.; investigation, M.A.; resources, M.A.; formal analysis, M.A.; data curation, A.E. and M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A. and J.V.; writing—review and editing, A.E., J.V., A.A.N. and E.A.; supervision, A.E.; visualization, M.A. and A.E.; project administration, A.E.; funding acquisition: J.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Shahrekord University. J.V. was funded by the European Union (ERC, FLEXINEL, 101086622). Views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting this study may be provided by the first author upon a reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to the privacy of parts of the data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, C.; Harrison, P.A.; Pan, X.; Li, H.; Sargent, I.; Atkinson, P.M. Scale Sequence Joint Deep Learning (SS-JDL) for land use and land cover classification. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 237, 111593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naegeli de Torres, F.; Richter, R.; Vohland, M. A multisensoral approach for high-resolution land cover and pasture degradation mapping in the humid tropics: A case study of the fragmented landscape of Rio de Janeiro. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf 2019, 78, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Fu, H.; Wu, B.; Clinton, N.; Gong, P. Exploring the Potential Role of Feature Selection in Global Land-Cover Mapping. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2016, 37, 5491–5504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topaloglu, R.H.; Sertel, E.; Musaoglu, N. Assessment of Classification Accuracies of Sentinel-2 and Landsat-8 Data for Land Cover/Use Mapping. In Proceedings of the XXIII ISPRS Congress, Prague, Czech Republic, 2–19 July 2016; Volume 41, pp. 1055–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, B. A SPECLib-based operational classification approach: A preliminary test on China land cover mapping at 30 m. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2018, 71, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurskainen, P.; Adhikari, H.; Siljander, M.; Pellikka, P.K.E.; Hemp, A. Auxiliary datasets improve accuracy of object-based land use/land cover classification in heterogeneous savanna landscapes. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 233, 111354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macintyre, P.D.; van Niekerk, A.; Mucina, L. Efficacy of multi-season Sentinel-2 imagery for compositional vegetation classification. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2020, 85, 101980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, C.A. Using Biophysical Geospatial and Remotely Sensed Data to Classify Ecological Sites and States. Master’s Thesis, Utah State University, Logan, UT, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Spiegal, S.; Bartolome, J.W.; White, M.D. Applying ecological site concepts to adaptive conservation management on an iconic Californian landscape. Rangelands 2016, 38, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.R.; Bestelmeyer, B.T. An Introduction to the Special Issue “Ecological Sites for Landscape Management”. Rangelands 2016, 38, 311–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, P.D.; del Valle, H.F.; Bouza, P.J.; Metternicht, G.I.; Hardtke, L.A. Ecological site classification of semiarid rangelands: Synergistic use of Landsat and Hyperion imagery. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2014, 29, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Galiano, V.; Chica-Olmo, M. Land cover change analysis of a Mediterranean area in Spain using different sources of data: Multi-seasonal Landsat images, land surface temperature, digital terrain models and texture. Appl. Geogr. 2012, 35, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluiter, R.; Pebesma, E.J. Comparing techniques for vegetation classification using multi- and hyperspectral images and ancillary environmental data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2010, 31, 6143–6161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, A.K.; Desai, V.R.; Patel, A.; Potdar, M.B. Post-classification corrections in improving the classification of Land Use/Land Cover of arid region using RS and GIS: The case of Arjuni watershed, Gujarat, India. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2017, 20, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghababaei, M.; Ebrahimi, A.; Naghipour, A.A.; Asadi, E.; Verrelst, J. Monitoring of Plant Ecological Units Cover Dynamics in a Semiarid Landscape from Past to Future Using Multi-Layer Perceptron and Markov Chain Model. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1612. (In Persian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogan, J.; Miller, J.; Stow, D.; Franklin, J.; Levien, L.; Fischer, C. Land-cover change monitoring with classification trees using Landsat TM and ancillary data. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2003, 69, 793–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdogan, M.; Gutman, G. A new methodology to map irrigated areas using multi-temporal MODIS and ancillary data: An application example in the continental US. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 3520–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, J.M.; Knight, J.F.; Gallant, A.L. Influence of multi-source and multitemporal remotely sensed and ancillary data on the accuracy of random forest classification of wetlands in Northern Minnesota. Remote Sens. 2013, 5, 3212–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Yu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Xu, Y.; Li, C.; Gong, P. A multiple dataset approach for 30-m resolution land cover mapping: A case study of continental Africa. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2018, 39, 3926–3938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Gallant, A.L.; Woodcock, C.E.; Pengra, B.P.; Olofsson, T.; Loveland, R.; Jin, S.; Dahal, D.; Yang, L.; Auch, R.F. Optimizing selection of training and auxiliary data for operational land cover classification for the LCMAP initiative. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2016, 122, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Weng, Q. A survey of image classification methods and techniques for improving classification performance. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2007, 28, 823–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatami, R.; Mountrakis, G.; Stehman, S.V. A meta-analysis of remote sensing research on supervised pixel-based land-cover image classification processes: General guidelines for practitioners and future research. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 177, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghababaei, M.; Ebrahimi, A.; Naghipour, A.A.; Asadi, E.; Verrelst, J. Vegetation Types Mapping Using Multi-Temporal Landsat Images in the Google Earth Engine Platform. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.R. Introductory Digital Image Processing: A Remote Sensing Perspective University of South Carolina; Pearson: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-0-13-405816-0. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Wan, B.; Qiu, P.; Su, Y.; Guo, Q.; Wu, X. Artificial Mangrove Species Mapping Using Pléiades-1: An Evaluation of Pixel-Based and Object-Based Classifications with Selected Machine Learning Algorithms. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, M.H.A.; Zhang, L.; Shuai, T.; Tong, Q. Derivation of a tasselled cap transformation based on Landsat 8 at-satellite reflectance. Remote Sens. Lett. 2014, 5, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghababaei, M.; Ebrahimi, A.; Naghipour, A.A.; Asadi, E.; Verrelst, J. Classification of Plant Ecological Units in Heterogeneous Semi-Steppe Rangelands: Performance Assessment of Four Classification Algorithms. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3433. (In Persian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghababaei, M.; Ebrahimi, A.; Naghipour, A.A.; Asadi, E.; Perez-Suay, A.; Morata, M.; Garcia, J.L.; Rivera Caicedo, J.P.; Verrelst, J. Introducing ARTMO’s Machine-Learning Classification Algorithms Toolbox: Application to Plant-Type Detection in a Semi-Steppe Iranian Landscape. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punia, M.; Joshi, P.K.; Porwal, M.C. Decision tree classification of land use land cover for Delhi, India using IRS-P6 AWiFS data. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 5577–5583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demsar, J. Statistical Comparisons of Classifiers over Multiple Data Sets. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2006, 7, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ouzemou, J.E.; Harti, A.; Lhissou, R.; Moujahid, A.; Bouch, N.; Ouazzani, R.; Bachaoui, M.; Ghmari, A. Crop type mapping from pansharpened Landsat 8 NDVI data: A case of a highly fragmented and intensive agricultural system. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2018, 11, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Chen, Y.; Lu, D.; Guiying, L.; Chen, E. Classification of Land Cover, Forest, and Tree Species Classes with ZiYuan-3 Multispectral and Stereo Data. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phiri, D.; Morgenroth, J.; Xu, C.; Hermosilla, T. Effects of pre-processing methods on Landsat OLI-8 land cover classification using OBIA and random forests classifier. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2018, 73, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Li, G.; Moran, E.; Kuang, W. A comparative analysis of approaches for successional vegetation classification in the Brazilian Amazon. Gisci. Remote Sens. 2014, 51, 695–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogan, J.; Franklin, J.; Stow, D.; Miller, J.; Woodcock, C.; Roberts, D. Mapping land-cover modifications over large areas: A comparison of machine learning algorithms. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 2272–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillejo-Gonzalez, I.; Angueira, C.; Garcia-Ferrer, A.; Sanchez de la Orden, M. Combining Object-Based Image Analysis with Topographic Data for Landform Mapping: A Case Study in the Semi-Arid Chaco Ecosystem, Argentina. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; Hardy, E.; Roach, J.; Witmer, R.E. A Land Use and Land Cover Classification System for Use with Remote Sensor Data. Geological Survey Professional; Professional Paper 964; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1976; 28p. [Google Scholar]

- Macintyre, P.D.; Van Niekerk, A.; Dobrowolski, M.P.; Tsakalos, J.L.; Mucina, L. Impact of ecological redundancy on the performance of machine learning classifiers in vegetation mapping. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 6728–6737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pflugmacher, D.; Rabe, A.; Peters, M.; Hostert, P. Mapping pan-European land cover using Landsat spectral-temporal metrics and the European LUCAS survey. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 221, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).