Quantitative Assessment of Satellite-Observed Atmospheric CO2 Concentrations over Oceanic Regions

Highlights

- The column-averaged atmospheric XCO2 can serve as a proxy for atmospheric XCO2 in the ocean boundary layer, with associated uncertainties.

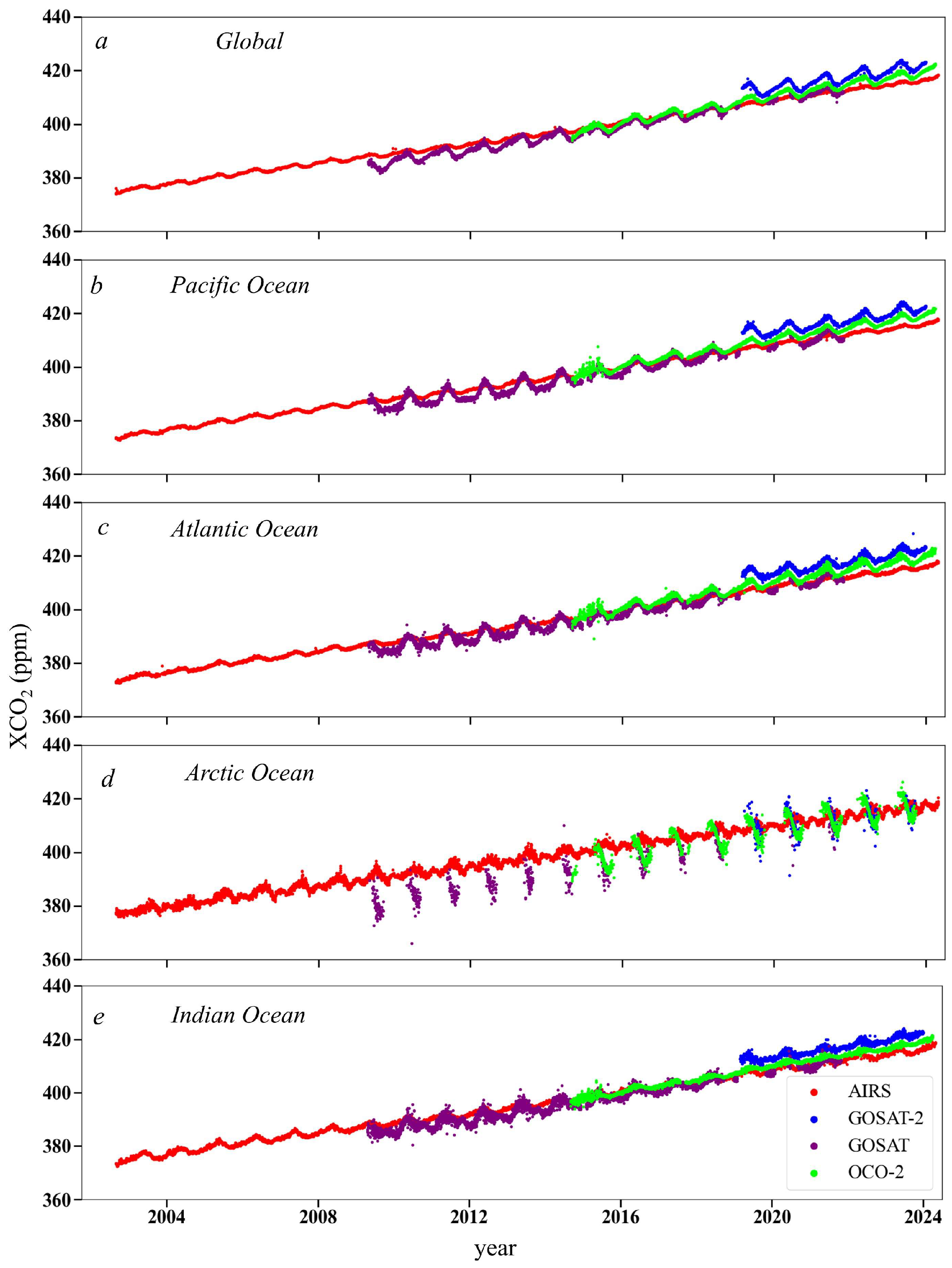

- Based on the longest data record from AIRS, the atmospheric XCO2 has been increasing at a rate of 1.87–1.97 ppm year−1 over global oceans in the past two decades.

- The uncertainties induced from the column-averaged atmospheric XCO2 should be finely evaluated in the estimates of air–sea CO2 fluxes.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

2.1.1. Satellite Data

2.1.2. Field Data

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Data Preprocessing and Matchup Criteria

2.2.2. Atmospheric XCO2 Growth Rates over Different Ocean Basins

2.2.3. Statistics Metrics

3. Results

3.1. Validation Based on Mooring Data

3.2. Validation Based on Cruise Data

3.3. Atmospheric XCO2 Growth Rates

4. Discussion

4.1. Differences Between Satellite and In Situ XCO2 Data

4.2. Differences Among Satellite-Derived Atmospheric XCO2

4.3. Implications on Air–Sea CO2 Fluxes from Satellites

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Friedlingstein, P.; O’Sullivan, M.; Jones, M.W.; Andrew, R.M.; Gregor, L.; Hauck, J.; Le Quéré, C.; Luijkx, I.T.; Olsen, A.; Peters, G.P.; et al. Global Carbon Budget 2022. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2022, 14, 4811–4900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, A.J.; Schuster, U.; Shutler, J.D.; Holding, T.; Ashton, I.G.C.; Landschützer, P.; Woolf, D.K.; Goddijn-Murphy, L. Revised Estimates of Ocean-Atmosphere CO2 Flux Are Consistent with Ocean Carbon Inventory. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, N.; Bakker, D.C.E.; DeVries, T.; Gregor, L.; Hauck, J.; Landschützer, P.; McKinley, G.A.; Müller, J.D. Trends and Variability in the Ocean Carbon Sink. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohrenz, S.E.; Cai, W.-J.; Chakraborty, S.; Huang, W.-J.; Guo, X.; He, R.; Xue, Z.; Fennel, K.; Howden, S.; Tian, H. Satellite Estimation of Coastal pCO2 and Air-Sea Flux of Carbon Dioxide in the Northern Gulf of Mexico. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 207, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustogi, P.; Landschützer, P.; Brune, S.; Baehr, J. The Impact of Seasonality on the Annual Air-Sea Carbon Flux and Its Interannual Variability. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2023, 6, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunsen, F.; Nissen, C.; Hauck, J. The Impact of Recent Climate Change on the Global Ocean Carbon Sink. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2024, 51, e2023GL107030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanninkhof, R. Relationship between Wind Speed and Gas Exchange over the Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. 1992, 97, 7373–7382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Cai, W.; He, X.; Zhai, W.; Pan, D.; Dai, M.; Yu, P. A Mechanistic Semi-analytical Method for Remotely Sensing Sea Surface pCO2 in River-dominated Coastal Oceans: A Case Study from the East China Sea. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2015, 120, 2331–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Hu, C.; Cai, W.-J.; Yang, B. Estimating Surface pCO2 in the Northern Gulf of Mexico: Which Remote Sensing Model to Use? Cont. Shelf Res. 2017, 151, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Hu, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, F.; Shi, Z.; Hu, B.; Du, Z.; Liu, R. Estimating Spatial and Temporal Variation in Ocean Surface pCO2 in the Gulf of Mexico Using Remote Sensing and Machine Learning Techniques. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 745, 140965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Lu, W.; Yu, S.; Li, S.; Meng, L.; Geng, X.; Yan, X.-H. Remote Sensing Estimations of the Seawater Partial Pressure of CO2 Using Sea Surface Roughness Derived from Synthetic Aperture Radar. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 4204913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Hu, C.; Barnes, B.B.; Wanninkhof, R.; Cai, W.-J.; Barbero, L.; Pierrot, D. A Machine Learning Approach to Estimate Surface Ocean pCO2 from Satellite Measurements. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 228, 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, R.F.; Price, B.A. Nitrous Oxide Solubility in Water and Seawater. Mar. Chem. 1980, 8, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Cai, W.; Wang, Y.; Lohrenz, S.E.; Murrell, M.C. The Carbon Dioxide System on the Mississippi River-dominated Continental Shelf in the Northern Gulf of Mexico: 1. Distribution and Air-sea CO2 Flux. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2015, 120, 1429–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, S.; Strong, K.; Wunch, D.; Mendonca, J.; Sweeney, C.; Baier, B.; Biraud, S.C.; Laughner, J.L.; Toon, G.C.; Connor, B.J. Retrieval of Atmospheric CO2 Vertical Profiles from Ground-Based near-Infrared Spectra. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2021, 14, 3087–3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Feng, G.; Xiang, R.; Xu, Y.; Qin, Y.; Li, S. Spatio-Temporal Validation of AIRS CO2 Observations Using GAW, HIPPO and TCCON. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuze, A.; Suto, H.; Nakajima, M.; Hamazaki, T. Thermal and near Infrared Sensor for Carbon Observation Fourier-Transform Spectrometer on the Greenhouse Gases Observing Satellite for Greenhouse Gases Monitoring. Appl. Opt. 2009, 48, 6716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuze, A.; Suto, H.; Shiomi, K.; Kawakami, S.; Tanaka, M.; Ueda, Y.; Deguchi, A.; Yoshida, J.; Yamamoto, Y.; Kataoka, F.; et al. Update on GOSAT TANSO-FTS Performance, Operations, and Data Products after More than 6 Years in Space. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2016, 9, 2445–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisp, D.; Pollock, H.R.; Rosenberg, R.; Chapsky, L.; Lee, R.A.M.; Oyafuso, F.A.; Frankenberg, C.; O’Dell, C.W.; Bruegge, C.J.; Doran, G.B.; et al. The On-Orbit Performance of the Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2(OCO-2) Instrument and Its Radiometrically Calibrated Products. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2017, 10, 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Pan, X.; Xiong, X.; Sun, T.; Xue, L.; Zhang, H.; Fang, J.; Fang, J.; Zhang, G.; Xu, H.; et al. Integration of Surface-Based and Space-Based Atmospheric CO2 Measurements for Improving Carbon Flux Estimates Using a New Developed 3-GAS Inversion Model. Atmos. Res. 2024, 307, 107477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Wang, B.; Chen, H.; Zhu, L.; Zheng, X.; Chen, S.X. A New Global Carbon Flux Estimation Methodology by Assimilation of Both in Situ and Satellite CO2 Observations. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2024, 7, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunch, D.; Wennberg, P.O.; Osterman, G.; Fisher, B.; Naylor, B.; Roehl, C.M.; O’Dell, C.; Mandrake, L.; Viatte, C.; Kiel, M.; et al. Comparisons of the Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 (OCO-2) XCO2 Measurements with TCCON. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2017, 10, 2209–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.L.; Yue, T.X.; Wilson, J.P.; Zhao, N.; Zhao, Y.P.; Du, Z.P.; Liu, Y. A Comparison of Satellite Observations with the XCO2 Surface Obtained by Fusing TCCON Measurements and GEOS-Chem Model Outputs. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 601–602, 1575–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunch, D.; Toon, G.C.; Blavier, J.-F.L.; Washenfelder, R.A.; Notholt, J.; Connor, B.J.; Griffith, D.W.T.; Sherlock, V.; Wennberg, P.O. The Total Carbon Column Observing Network. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 2011, 369, 2087–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laughner, J.L.; Toon, G.C.; Mendonca, J.; Petri, C.; Roche, S.; Wunch, D.; Blavier, J.-F.; Griffith, D.W.T.; Heikkinen, P.; Keeling, R.F.; et al. The Total Carbon Column Observing Network’s GGG2020 Data Version. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 16, 2197–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Chen, B.; Measho, S. Spatio-Temporal Consistency Evaluation of XCO2 Retrievals from GOSAT and OCO-2 Based on TCCON and Model Data for Joint Utilization in Carbon Cycle Research. Atmosphere 2019, 10, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, Y.; Someya, Y.; Ohyama, H.; Morino, I.; Matsunaga, T.; Deutscher, N.M.; Griffith, D.W.T.; Hase, F.; Iraci, L.T.; Kivi, R.; et al. Quality Evaluation of the Column-Averaged Dry Air Mole Fractions of Carbon Dioxide and Methane Observed by GOSAT and GOSAT-2. SOLA 2023, 19, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, A.; Gong, W.; Han, G.; Xiang, C. Comparison of Satellite-Observed XCO2 from GOSAT, OCO-2, and Ground-Based TCCON. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Chen, B.; Zhang, H.; Dilawar, A.; Guo, M.; Liu, C.; Liu, S.; Gemechu, T.M.; Zhang, X. Global Evaluation and Intercomparison of XCO2 Retrievals from GOSAT, OCO-2, and TANSAT with TCCON. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, S. Comparison of Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide Concentrations Based on GOSAT, OCO-2 Observations and Ground-Based TCCON Data. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Bai, Y.; He, X.; Huang, H.; Zhu, Q.; Gong, F. Comparisons of OCO-2 Satellite Derived XCO2 with in Situ and Modeled Data over Global Ocean. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2021, 40, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.; Tanimoto, H.; Sugita, T.; Machida, T.; Nakaoka, S.; Patra, P.K.; Laughner, J.; Crisp, D. New Approach to Evaluate Satellite-Derived XCO2 over Oceans by Integrating Ship and Aircraft Observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21, 8255–8271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curbelo-Hernández, D.; González-Dávila, M.; González, A.G.; González-Santana, D.; Santana-Casiano, J.M. CO2 Fluxes in the Northeast Atlantic Ocean Based on Measurements from a Surface Ocean Observation Platform. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 775, 145804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jersild, A.; Landschützer, P. A Spatially Explicit Uncertainty Analysis of the Air-Sea CO2 Flux From Observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2024, 51, e2023GL106636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; He, R.; Fennel, K.; Cai, W.-J.; Lohrenz, S.; Huang, W.-J.; Tian, H.; Ren, W.; Zang, Z. Modeling pCO2 Variability in the Gulf of Mexico. Biogeosciences 2016, 13, 4359–4377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.; Guerlet, S.; Butz, A.; Houweling, S.; Hasekamp, O.; Aben, I.; Krummel, P.; Steele, P.; Langenfelds, R.; Torn, M.; et al. Global CO2 Fluxes Estimated from GOSAT Retrievals of Total Column CO2. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013, 13, 8695–8717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Wang, H.; Chen, J.M.; Ju, W.; Tian, X.; Feng, S.; Li, G.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, S.; Lu, X.; et al. Regional CO2 Fluxes from 2010 to 2015 Inferred from GOSAT XCO2 Retrievals Using a New Version of the Global Carbon Assimilation System. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21, 1963–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Tian, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, M.; Wang, T.; Ding, J.; Piao, S. A Global Surface CO2 Flux Dataset (2015–2022) Inferred from OCO-2 Retrievals Using the GONGGA Inversion System. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 16, 2857–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Song, Z.; Bai, Y.; Guo, X.; He, X.; Zhai, W.; Zhao, H.; Dai, M. Satellite-Estimated Air-Sea CO2 Fluxes in the Bohai Sea, Yellow Sea, and East China Sea: Patterns and Variations during 2003–2019. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 904, 166804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Liu, M.; Tao, M.; Zhou, W.; Lu, X.; Xiong, Y.; Li, F.; Wang, Q. The Role of Satellite Remote Sensing in Mitigating and Adapting to Global Climate Change. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 904, 166820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, Y.; Kikuchi, N.; Morino, I.; Uchino, O.; Oshchepkov, S.; Bril, A.; Saeki, T.; Schutgens, N.; Toon, G.C.; Wunch, D.; et al. Improvement of the Retrieval Algorithm for GOSAT SWIR XCO2 and XCH4 and Their Validation Using TCCON Data. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2013, 6, 1533–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, N.; O’Dell, C.W.; Taylor, T.E.; Logan, T.L.; Byrne, B.; Kiel, M.; Kivi, R.; Heikkinen, P.; Merrelli, A.; Payne, V.H.; et al. The Importance of Digital Elevation Model Accuracy in XCO2 Retrievals: Improving the Orbiting Carbon Observatory 2 Atmospheric Carbon Observations from Space Version 11 Retrieval Product. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2024, 17, 1375–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.; Barnet, C.D. CLIMCAPS Observing Capability for Temperature, Moisture, and Trace Gases from AIRS/AMSU and CrIS/ATMS. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2020, 13, 4437–4459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Cai, W.-J.; Hu, X.; Sabine, C.; Jones, S.; Sutton, A.J.; Jiang, L.-Q.; Reimer, J.J. Sea Surface Carbon Dioxide at the Georgia Time Series Site (2006–2007): Air–Sea Flux and Controlling Processes. Prog. Oceanogr. 2016, 140, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, A.J.; Wanninkhof, R.; Sabine, C.L.; Feely, R.A.; Cronin, M.F.; Weller, R.A. Variability and Trends in Surface Seawater pCO2 and CO2 Flux in the Pacific Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017, 44, 5627–5636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, A.J.; Feely, R.A.; Maenner-Jones, S.; Musielwicz, S.; Osborne, J.; Dietrich, C.; Monacci, N.; Cross, J.; Bott, R.; Kozyr, A.; et al. Autonomous Seawater pCO2 and pH Time Series from 40 Surface Buoys and the Emergence of Anthropogenic Trends. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2019, 11, 421–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, A.J.; Sabine, C.L.; Maenner-Jones, S.; Lawrence-Slavas, N.; Meinig, C.; Feely, R.A.; Mathis, J.T.; Musielewicz, S.; Bott, R.; McLain, P.D.; et al. A High-Frequency Atmospheric and Seawater pCO2 Data Set from 14 Open-Ocean Sites Using a Moored Autonomous System. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2014, 6, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeil, B.; Olsen, A.; Bakker, D.C.E.; Hankin, S.; Koyuk, H.; Kozyr, A.; Malczyk, J.; Manke, A.; Metzl, N.; Sabine, C.L.; et al. A Uniform, Quality Controlled Surface Ocean CO2 Atlas (SOCAT). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2013, 5, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, D.C.E.; Pfeil, B.; Landa, C.S.; Metzl, N.; O’Brien, K.M.; Olsen, A.; Smith, K.; Cosca, C.; Harasawa, S.; Jones, S.D.; et al. A Multi-Decade Record of High-Quality fCO2 Data in Version 3 of the Surface Ocean CO2 Atlas (SOCAT). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2016, 8, 383–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fay, A.R.; Munro, D.R.; McKinley, G.A.; Pierrot, D.; Sutherland, S.C.; Sweeney, C.; Wanninkhof, R. Updated Climatological Mean ΔfCO2 and Net Sea–Air CO2 Flux over the Global Open Ocean Regions. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 16, 2123–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierrot, D.; Neill, C.; Sullivan, K.; Castle, R.; Wanninkhof, R.; Lüger, H.; Johannessen, T.; Olsen, A.; Feely, R.A.; Cosca, C.E. Recommendations for Autonomous Underway pCO2 Measuring Systems and Data-Reduction Routines. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2009, 56, 512–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhou, X.; Cheng, T.; Tao, Z.; Gu, X.; Wang, N.; Zhang, H.; Lv, T. The Influence of Validation Colocation on XCO2 Satellite–Terrestrial Joint Observations. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iturbide, M.; Gutiérrez, J.M.; Alves, L.M.; Bedia, J.; Cerezo-Mota, R.; Cimadevilla, E.; Cofiño, A.S.; Di Luca, A.; Faria, S.H.; Gorodetskaya, I.V.; et al. An Update of IPCC Climate Reference Regions for Subcontinental Analysis of Climate Model Data: Definition and Aggregated Datasets. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2020, 12, 2959–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchwitz, M.; Reuter, M.; Schneising, O.; Noël, S.; Gier, B.; Bovensmann, H.; Burrows, J.P.; Boesch, H.; Anand, J.; Parker, R.J.; et al. Computation and Analysis of Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide Annual Mean Growth Rates from Satellite Observations during 2003–2016. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 17355–17370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butz, A.; Guerlet, S.; Hasekamp, O.; Schepers, D.; Galli, A.; Aben, I.; Frankenberg, C.; Hartmann, J.-M.; Tran, H.; Kuze, A.; et al. Toward Accurate CO2 and CH4 Observations from GOSAT. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011, 38, L14812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Aan De Brugh, J.; Meijer, Y.; Sierk, B.; Hasekamp, O.; Butz, A.; Landgraf, J. XCO2 Observations Using Satellite Measurements with Moderate Spectral Resolution: Investigation Using GOSAT and OCO-2 Measurements. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2020, 13, 713–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uma, K.N.; Girach, I.A.; Chandra, N.; Patra, P.K.; Kumar, N.V.P.K.; Nair, P.R. CO2 Variability over a Tropical Coastal Station in India: Synergy of Observation and Model. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 957, 177371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, T.; Sutherland, S.C.; Wanninkhof, R.; Sweeney, C.; Feely, R.A.; Chipman, D.W.; Hales, B.; Friederich, G.; Chavez, F.; Sabine, C.; et al. Climatological Mean and Decadal Change in Surface Ocean pCO2, and Net Sea–Air CO2 Flux over the Global Oceans. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2009, 56, 554–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemoto, K.; Midorikawa, T.; Wada, A.; Ogawa, K.; Takatani, S.; Kimoto, H.; Ishii, M.; Inoue, H.Y. Continuous Observations of Atmospheric and Oceanic CO2 Using a Moored Buoy in the East China Sea: Variations during the Passage of Typhoons. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2009, 56, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchwitz, M.; Reuter, M.; Schneising, O.; Boesch, H.; Guerlet, S.; Dils, B.; Aben, I.; Armante, R.; Bergamaschi, P.; Blumenstock, T.; et al. The Greenhouse Gas Climate Change Initiative (GHG-CCI): Comparison and Quality Assessment of near-Surface-Sensitive Satellite-Derived CO2 and CH4 Global Data Sets. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 162, 344–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, T.E.; O’Dell, C.W.; Baker, D.; Bruegge, C.; Chang, A.; Chapsky, L.; Chatterjee, A.; Cheng, C.; Chevallier, F.; Crisp, D.; et al. Evaluating the Consistency between OCO-2 and OCO-3 XCO2 Estimates Derived from the NASA ACOS Version 10 Retrieval Algorithm. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2023, 16, 3173–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, A.F.; Zhang, Z.; Yoshida, Y.; Chatterjee, A.; Poulter, B. Using Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 (OCO-2) Column CO2 Retrievals to Rapidly Detect and Estimate Biospheric Surface Carbon Flux Anomalies. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2023, 23, 1545–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, T.E.; O’Dell, C.W.; Frankenberg, C.; Partain, P.T.; Cronk, H.Q.; Savtchenko, A.; Nelson, R.R.; Rosenthal, E.J.; Chang, A.Y.; Fisher, B.; et al. Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 (OCO-2) Cloud Screening Algorithms: Validation against Collocated MODIS and CALIOP Data. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2016, 9, 973–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Hasekamp, O.; Hu, H.; Landgraf, J.; Butz, A.; Aan De Brugh, J.; Aben, I.; Pollard, D.F.; Griffith, D.W.T.; Feist, D.G.; et al. Carbon Dioxide Retrieval from OCO-2 Satellite Observations Using the RemoTeC Algorithm and Validation with TCCON Measurements. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2018, 11, 3111–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massie, S.T.; Cronk, H.; Merrelli, A.; O’Dell, C.; Schmidt, K.S.; Chen, H.; Baker, D. Analysis of 3D Cloud Effects in OCO-2 XCO2 Retrievals. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2021, 14, 1475–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, T.E.; O’Dell, C.W.; Crisp, D.; Kuze, A.; Lindqvist, H.; Wennberg, P.O.; Chatterjee, A.; Gunson, M.; Eldering, A.; Fisher, B.; et al. An 11-Year Record of XCO2 Estimates Derived from GOSAT Measurements Using the NASA ACOS Version 9 Retrieval Algorithm. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2022, 14, 325–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.; Fetzer, E.J.; Schreier, M.; Manipon, G.; Fishbein, E.F.; Kahn, B.H.; Yue, Q.; Irion, F.W. Cloud-induced Uncertainties in AIRS and ECMWF Temperature and Specific Humidity. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2015, 120, 1880–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, B.; Bösch, H.; McDuffie, J.; Taylor, T.; Fu, D.; Frankenberg, C.; O’Dell, C.; Payne, V.H.; Gunson, M.; Pollock, R.; et al. Quantification of Uncertainties in OCO-2 Measurements of XCO2: Simulations and Linear Error Analysis. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2016, 9, 5227–5238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldering, A.; Wennberg, P.O.; Crisp, D.; Schimel, D.S.; Gunson, M.R.; Chatterjee, A.; Liu, J.; Schwandner, F.M.; Sun, Y.; O’Dell, C.W.; et al. The Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 Early Science Investigations of Regional Carbon Dioxide Fluxes. Science 2017, 358, eaam5745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imasu, R.; Matsunaga, T.; Nakajima, M.; Yoshida, Y.; Shiomi, K.; Morino, I.; Saitoh, N.; Niwa, Y.; Someya, Y.; Oishi, Y.; et al. Greenhouse Gases Observing SATellite 2 (GOSAT-2): Mission Overview. Prog. Earth Planet. Sci. 2023, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevallier, F.; Engelen, R.J.; Peylin, P. The Contribution of AIRS Data to the Estimation of CO2 Sources and Sinks. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005, 32, 2005GL024229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caínzos, V.; Velo, A.; Pérez, F.F.; Hernández-Guerra, A. Anthropogenic Carbon Transport Variability in the Atlantic Ocean Over Three Decades. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2022, 36, e2022GB007475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, T.; Batista, M.; Henley, S.; Machado, E.D.C.; Araujo, M.; Kerr, R. Contrasting Sea-Air CO2 Exchanges in the Western Tropical Atlantic Ocean. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2022, 36, e2022GB007385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natali, S.M.; Holdren, J.P.; Rogers, B.M.; Treharne, R.; Duffy, P.B.; Pomerance, R.; MacDonald, E. Permafrost Carbon Feedbacks Threaten Global Climate Goals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2100163118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, J.; Chakraborty, K.; Valsala, V.; Bhattacharya, T.; Ghoshal, P.K. A review of the Indian Ocean carbon dynamics, acidity, and productivity in a changing environment. Prog. Oceanogr. 2024, 221, 103210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shutler, J.D.; Gruber, N.; Findlay, H.S.; Land, P.E.; Gregor, L.; Holding, T.; Sims, R.P.; Green, H.; Piolle, J.-F.; Chapron, B.; et al. The Increasing Importance of Satellite Observations to Assess the Ocean Carbon Sink and Ocean Acidification. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2024, 250, 104682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, F.; Jones, D.B.A.; O’Dell, C.W.; Nassar, R.; Parazoo, N.C. Combining GOSAT XCO2 Observations over Land and Ocean to Improve Regional CO2 Flux Estimates. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2016, 121, 1896–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, P.K.; Hajima, T.; Saito, R.; Chandra, N.; Yoshida, Y.; Ichii, K.; Kawamiya, M.; Kondo, M.; Ito, A.; Crisp, D. Evaluation of Earth System Model and Atmospheric Inversion Using Total Column CO2 Observations from GOSAT and OCO-2. Prog. Earth Planet. Sci. 2021, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Han, G.; Ma, X.; Gong, W.; Chen, W.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Pei, Z.; Gou, H.; Bu, L. Quantifying CO2 Uptakes Over Oceans Using LIDAR: A Tentative Experiment in Bohai Bay. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2020GL091160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Liu, Y.; Feng, L.; Wang, J.; Yao, L.; Cai, Z.; Zhu, S.; Lu, N.; Lyu, D. The First Global Carbon Dioxide Flux Map Derived from TanSat Measurements. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2021, 38, 1433–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Satellite/Sensor | Bands (μm) | Revisit Period (Day) | Spatial Resolution (km) | Altitude (km) | Period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GOSAT | 1.6, 2.0 | 3 | 10.5 × 10.5 | 666 | 2009.04–2021.10 |

| GOSAT-2 | 1.6, 2.0 | 6 | 9.7 × 9.7 | 613 | 2019.03–2023.12 |

| OCO-2 | 1.6, 2.0 | 16 | 2.25 × 1.29 | 705 | 2014.09–2024.03 |

| AIRS | 15 | 16 | 13.5 × 13.5 | 705 | 2002.08–2024.04 |

| Satellite/Sensor | Time Window (min) | N | R2 | RMSD (ppm) | MAE (ppm) | MAPE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GOSAT | ±30 | 63 | 0.72 | 4.55 | 3.07 | 0.78 |

| ±60 | 276 | 0.65 | 6.10 | 4.24 | 1.08 | |

| GOSAT-2 | ±30 | 59 | 0.35 | 7.71 | 6.50 | 1.67 |

| ±60 | 126 | 0.26 | 6.33 | 5.26 | 1.33 | |

| OCO-2 | ±30 | 630 | 0.49 | 5.65 | 4.10 | 1.00 |

| ±60 | 919 | 0.49 | 5.51 | 4.00 | 0.98 | |

| AIRS | ±30 | 3898 | 0.72 | 6.38 | 4.19 | 1.05 |

| ±60 | 4924 | 0.61 | 7.70 | 4.83 | 1.20 |

| Satellite/Sensor | Time Window (min) | N | R2 | RMSD (ppm) | MAE (ppm) | MAPE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GOSAT | ±30 | 119 | 0.83 | 2.48 | 1.93 | 0.46 |

| ±60 | 321 | 0.87 | 2.74 | 2.17 | 0.52 | |

| GOSAT-2 | ±30 | 48 | 0.83 | 1.01 | 0.98 | 0.24 |

| ±60 | 103 | 0.61 | 1.97 | 1.34 | 0.26 | |

| OCO-2 | ±30 | 1002 | 0.89 | 2.45 | 1.84 | 0.45 |

| ±60 | 1888 | 0.89 | 2.44 | 1.81 | 0.44 | |

| AIRS | ±30 | 64,076 | 0.89 | 4.22 | 3.53 | 0.83 |

| ±60 | 137,223 | 0.88 | 4.31 | 3.37 | 0.85 |

| Ocean Region | Satellite/Sensor | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GOSAT | GOSAT-2 | OCO-2 | AIRS | |

| Global | 2.29 | 2.19 | 2.42 | 1.94 |

| Pacific Ocean | 2.21 | 2.06 | 2.39 | 1.97 |

| Atlantic Ocean | 2.29 | 2.14 | 2.42 | 1.97 |

| Arctic Ocean | 2.57 | 1.70 | 2.60 | 1.87 |

| Indian Ocean | 2.20 | 2.15 | 2.33 | 1.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, X.; Chen, S.; Xi, J.; Wang, Y. Quantitative Assessment of Satellite-Observed Atmospheric CO2 Concentrations over Oceanic Regions. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 4026. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244026

He X, Chen S, Xi J, Wang Y. Quantitative Assessment of Satellite-Observed Atmospheric CO2 Concentrations over Oceanic Regions. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):4026. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244026

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Xinyu, Shuangling Chen, Jingyuan Xi, and Yuntao Wang. 2025. "Quantitative Assessment of Satellite-Observed Atmospheric CO2 Concentrations over Oceanic Regions" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 4026. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244026

APA StyleHe, X., Chen, S., Xi, J., & Wang, Y. (2025). Quantitative Assessment of Satellite-Observed Atmospheric CO2 Concentrations over Oceanic Regions. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 4026. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244026