Highlights

- We innovatively construct a three concentric Gaussian PSF degradation model to ac-curately represent the non-ideal energy distribution of the ghosts of hyperspectral images, enabling high-fidelity simulation and correction while preserving spectral calibration accuracy.

- A novel simulated annealing algorithm is proposed to iteratively correct the ghosts across multiple spectral bands, achieving significant ghost energy suppression with accurate spectral precision.

Abstract

In hyperspectral images, ghost image residuals exceeding a certain threshold not only reduce the recognition accuracy of the imaging detection system but also decrease the target identification rate. Ghost image residuals affect both the recognition accuracy of the detection system and the accuracy of spectral calibration, thereby influencing qualitative and quantitative inversion. Conventional ghost image residual correction methods can significantly affect both the relative and absolute calibration accuracy of hyperspectral images. To minimize the impact on spectral calibration accuracy during ghost image residual correction, we propose a ghost image degradation model and an iterative optimization algorithm. In the proposed approach, a ghost image residual degradation model is constructed based on the point spread function (PSF) of ghost image residuals and their energy distribution characteristics. Using the proportion of ghost image residuals and the accuracy of hyperspectral image calibration as constraints, we iteratively optimized typical regional target ghost image residuals across different spectral channels, achieving automated correction of ghost image residuals in various spectral bands. The experimental results show that the energy proportion of ghost image residuals at different wavelengths decreased from 4.6% to 0.3%, the variations in spectral curves before and after correction were less than 0.8%, and the change in absolute radiometric calibration accuracy was below 0.06%.

1. Introduction

Recently, imaging spectrometers have been widely used in various fields, including remote sensing, biomedicine, chemical detection, mineral exploration, environmental monitoring, missile interception, explosion analysis, and combustion diagnostics [1,2,3,4,5]. Ghost image residuals widely exist in optical systems, mainly caused by factors such as light reflection, refraction, and scattering. In other words, abnormal path light rays converge on the CCD target surface, affecting the recognition accuracy and decreasing the target recognition rate of detection imaging systems when ghost image residuals exceed a certain threshold [6,7,8]. In hyperspectral images, ghost image residuals affect not only the recognition accuracy of the detection system but also the spectral calibration accuracy, thereby affecting qualitative and quantitative inversion of material properties [9,10,11,12]. Therefore, it is highly significant to correct ghost image residuals of hyperspectral images. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory in the United States simulated stray light and ghost image residual energy distributions by testing its EMIT system [13,14,15], reducing its energy to 1–5 DN values, and achieving the residual signal of approximately 0.0005 μW·nm·cm−2·Sr−1, which is three orders of magnitude lower than the water reflectance signal. Shanghai Institute of Technical Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, conducted stray light analysis on the Medium Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MERSI) carried on Fengyun-3D, modeling different surfaces using the bidirectional scatter distribution function (BSDF) for ray tracing on the end-to-end link light. We propose a simulated ghost image degradation model combined with an iterative optimization algorithm. The model was constructed by leveraging the point spread function (PSF) of ghost image residuals and their energy distribution characteristics. Using the proportion of ghost image residuals and hyperspectral calibration accuracy as constraints, the proposed method iteratively optimizes the regional target residuals across different hyperspectral channels, enabling automatic correction of ghost image residuals across spectral bands. This ghost image residual correction model offers significant value for correcting dispersion-type hyperspectral ghost image residuals.

2. Methods

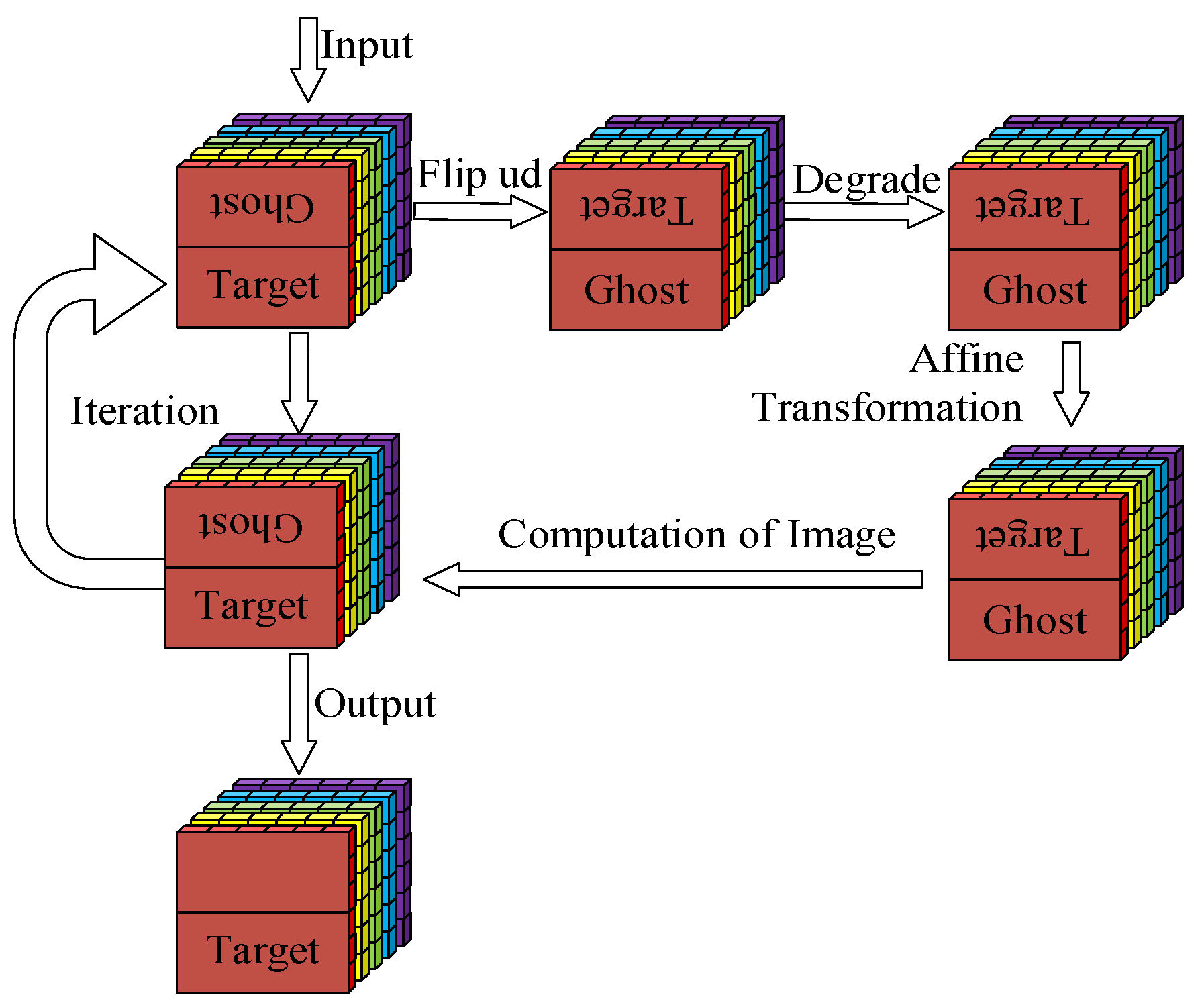

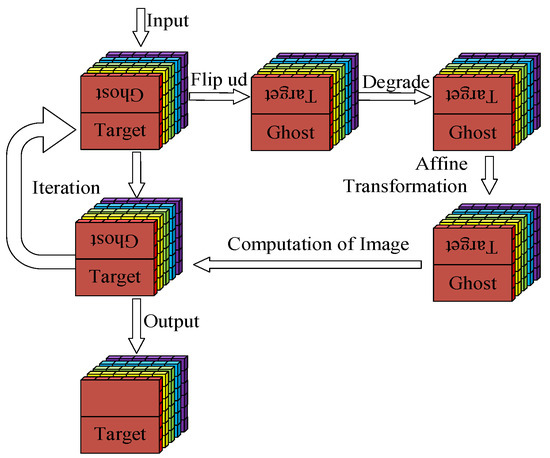

The core goal of ghost image residual correction in hyperspectral images is to reduce the proportion of ghost image residuals while ensuring the hyperspectral image features remain unchanged, thereby diminishing the impact on spectral calibration accuracy during the ghost image residual correction in hyperspectral images. The schematic diagram of the ghost image residual correction in hyperspectral images is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic Diagram of Ghost Image Residual Correction in Hyperspectral Images.

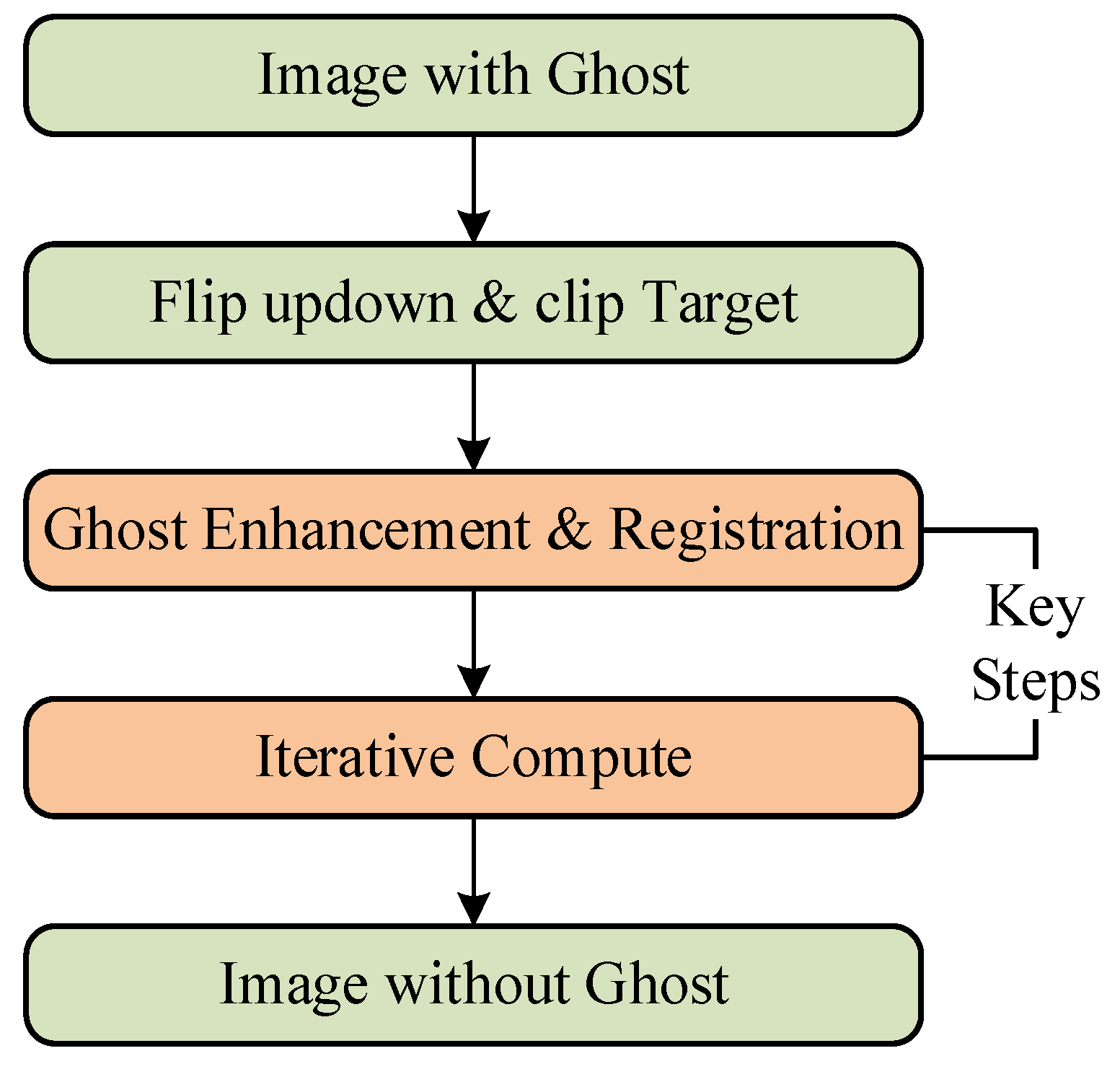

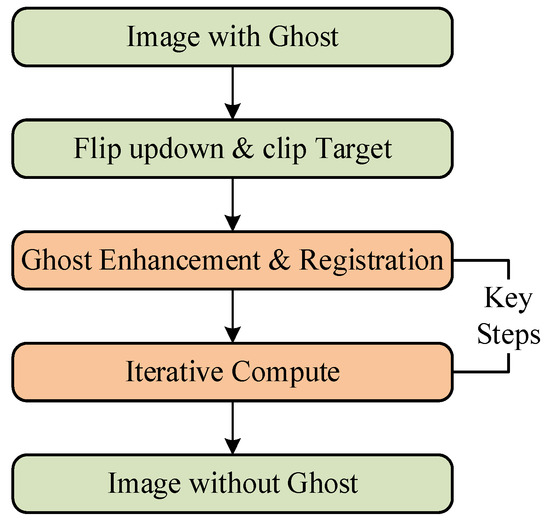

Based on the schematic diagram, we propose a workflow of ghost image residual correction in hyperspectral images, as illustrated in Figure 2. The key steps are ghost image residual enhancement, ghost image residual registration, and ghost image residual removal. The goal of enhancement and registration is to ensure spatial registration between target images and ghost image residuals, while iterative optimization aims to reduce the proportion of ghost image residuals to meet the requirements of image utilization.

Figure 2.

Workflow of Ghost Image Residual Correction in Hyperspectral Images.

The ghost image residual registration in hyperspectral images primarily aims to align the spatial dimensions of target images with those of ghost image residuals. However, due to the significantly low energy of ghost image residuals in hyperspectral images compared to that of the sky background, their contrast ratio is closest to that of the sky background, posing substantial challenges to structural registration. To address this difficulty, signal enhancement is executed before ghost image residual registration. The ghost image feature enhancement is primarily achieved through the use of a different contrast-limited adaptive histogram equalization (CLAHE) algorithm in varying scales of local regions [16,17,18] to improve the registration accuracy of hyperspectral images. The improved CLAHE algorithm is presented in Equation (1).

Here, denotes the CLAHE-enhanced result of coordinates (x, y) at scale k, and wk(x,y) represents the corresponding weight of the enhancement at scale k. With the enhancement of the ghost image residual features, some noise in the sky background image are also synchronously enhanced. To suppress the noise and achieve the registration between ghost image residuals and target images, the SURF registration was performed on hyperspectral images of the same channel in different-scale local regions to accurately achieve registration between ghost image residuals and target images [19,20].

The energy distribution registration of the target image with ghost image residual primarily relies on the fitting of the ghost image residual point spread function (PSF) [21,22,23]. Based on the PSF energy distribution of ghost image residuals in a single channel provided by optical simulation analyses, the ideally fitted two-dimensional Gaussian function is used as the optimization process of ghost image residual degradation. Since the energy distribution of actual ghost image residuals after a single reflection on the CCD does not conform to the ideal Bessel function, three concentric Gaussian distribution functions are selected to simulate the ghost image residual energy distribution, and the equation is listed below:

where PSF2D(x,y) represents the two-dimensional ghost image residual energy distribution function; Ak denotes the coefficients of Gaussian distribution functions; x0 and y0 represent the central positions along the x-axis and y-axis, respectively; and σxk and σyk correspond to the standard deviations along the x and y directions, respectively. When x = x0, Equation (2) is equivalent to the one-dimensional PSF energy distribution function in the y direction, and the coefficients Aₖ should meet the normalization condition .

In order to minimize the sum of the squared errors between the simulated ghost image residual energy distribution and the simulation data, the parameter estimation equation is as follows:

where is the one-dimensional simulated energy distribution in the x direction. When y ≠ y0, is the one-dimensional PSF data in the x-direction; Similarly, when y = y0, is the one-dimensional PSF data in the y-direction. Equation (3) is used to evaluate the degree between the fitted results and data, so the goal of the optimization process is to obtain the minimum value of L(θ). θ is defined below:

The control optimization results require adding boundary conditions Ak > 0, σxk > 0, σyk > 0, as well as controlling the primary and secondary orders of three concentric Gaussian distributions and adding constraint conditions σx1 < σx2 < σx3. The final PSF2D(x,y) obtained is the peak normalized distribution function. At this point, the double integral of PSF2D(x,y) is not 1 and cannot be used as a degradation function or for image convolution. Therefore, the following conditions should also be satisfied:

where Hλ is the final degradation function and γ is the scaling factor of PSF2D (x,y). The final correction result can be obtained by calculating the degradation function in all bands and convolving it with real images, and then using the ghost image iteration algorithm to perform spatial dimension operations on the image. The pseudo code of the ghost image iteration algorithm is shown in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1. Pseudo Code for Ghost Image Residual Correction Iteration Algorithm in Hyperspectral Images |

| Ghost Image Removal via Iterative Optimization |

| Description: Minimizing ghost image representation in images based on simulated annealing algorithm |

| Input: rate of temperature drop γ, Image with Ghost I0 |

| Output: Image I of Removed Ghost |

| Initialization: set I = I0 |

| set Iterative Counter k = 0 |

| set Original Temperature T0 |

| set Minimum Temperature Tmin |

| Iteration: |

| end while |

According to the simulated degradation algorithm [24,25], ghost image residuals and target images are iterated. Firstly, the degradation function Hλ and the ghost image residual energy coefficient αk of hyperspectral images are used to eliminate the ghost image continuously in the previous iteration output, as shown in Equation (6).

Inew = I(k) − α(k) · (Hλ × I(k))

In the equation, I(k) is the output image of the kth iteration, and I(0) is the original image.

The optimization of the ghost image residual correction in hyperspectral images is achieved through the convolution of Hλ and I(k) and the linear constraint of α(k). Degradation from the input image to the ghost image is implemented. The ghost image energy coefficient αk is jointly updated by the ghost image energy coefficient αk−1 from the previous iteration and the random error term δk−1. The random error term δk−1 is a sample in the uniformly distributed set U(−ε(k), ε(k)), and the set interval is determined by the iteration round k, as shown in Equations (7) and (8), where p is the convergence speed of the random error term, and the larger the p, the faster the convergence speed of the random error term interval.

For Inew that undergoes ghost removal one time, the evaluation function E(k) is used to evaluate its DN value dispersion in the sky region. The general equation for the evaluation function is shown in Equation (9):

where Ιghost(k) (x,y) represents the ghost image region in the kth step image processing and μsky represents the mean of the sky region without ghost images. Comparing the calculation results of the evaluation function before and after ghost image removal, Inew after ghost image removal is evaluated, as shown in Equation (10).

When the evaluation function Enew of Inew is smaller than that of the previous iteration, it indicates that the ghost image removal effect is significant this time, and the result is the output Inew of this iteration. On the contrary, the probability is accepted, and Inew and Ik are output when accepted and rejected, respectively. In addition to the above iterative steps, the temperature coefficient T(k) is used to constrain the overall iterative process of the algorithm. The equation of the temperature coefficient calculation and its relationship with the maximum iteration step kmax are shown in Equations (11) and (12).

In the equations, T0 is the initial temperature, γ is the cooling rate, and Tmin is the lowest temperature. When T(k) < Tmin, the iteration stops and outputs I(k).

The ghost image residual degradation algorithm mainly iteratively removes the ghost image residual elements to gradually reduce the impact of ghost image residuals on the target image details.

3. Results

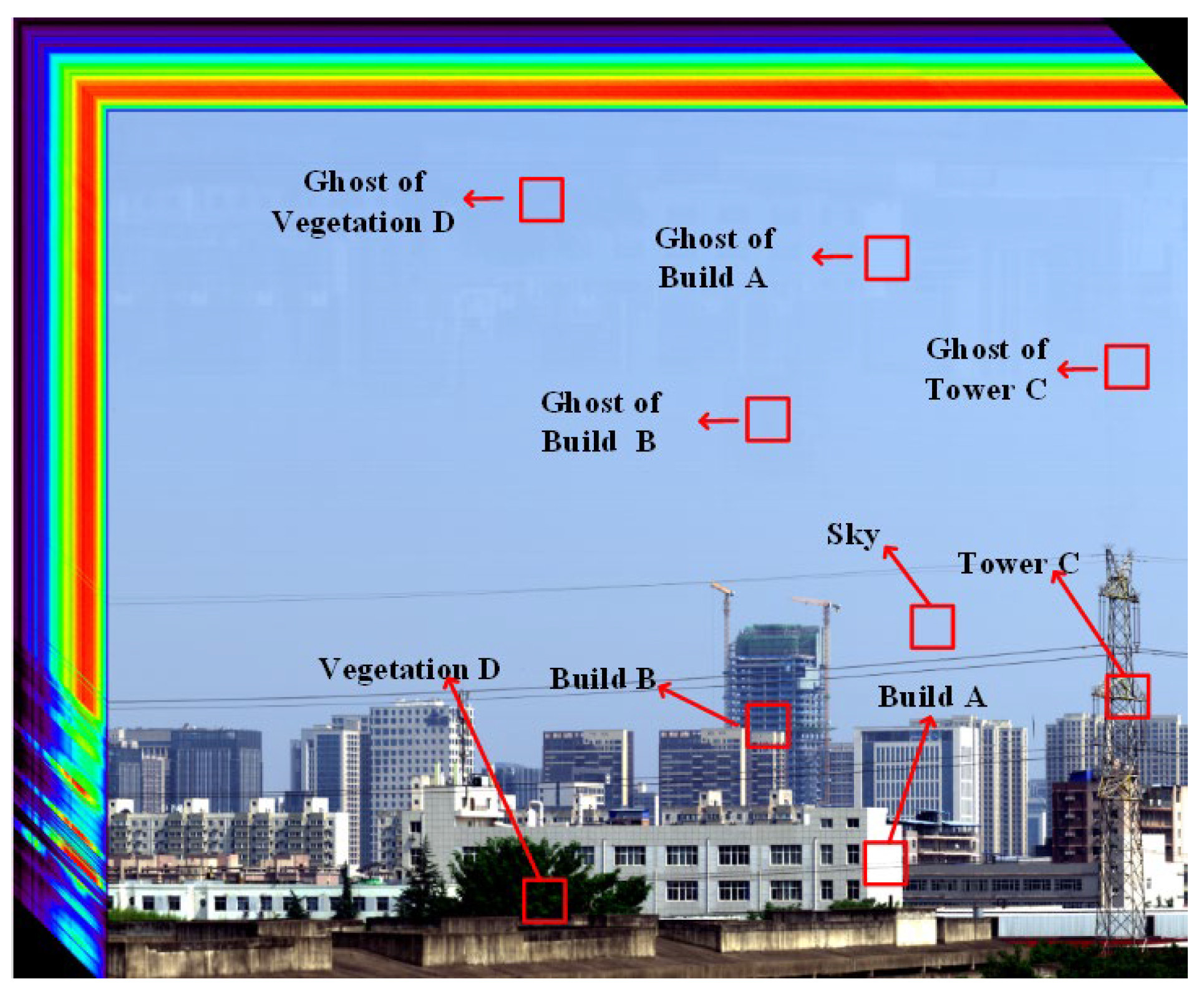

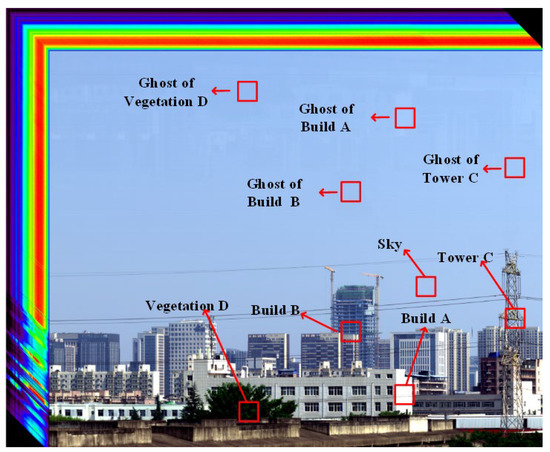

The ghost image residual hyperspectral data cube has a wavelength range of 430–850 nm, a total of 72 spectral channels, and an image spatial pixel resolution of 2000 pixels. The number of image splicing frames is 2500. The ghost image residual hyperspectral data cube is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Ghost Image Residual Hyperspectral Data Cube and Typical Target Distribution.

To analyze the impacts of ghost image residuals on targets and image quality, Building A, Building B, Tower C, and Vegetation D were selected as typical targets, and the spectral curve changes for the targets and the spectral curve of ghost image residuals were used as objects for evaluating ghost image residual correction performance.

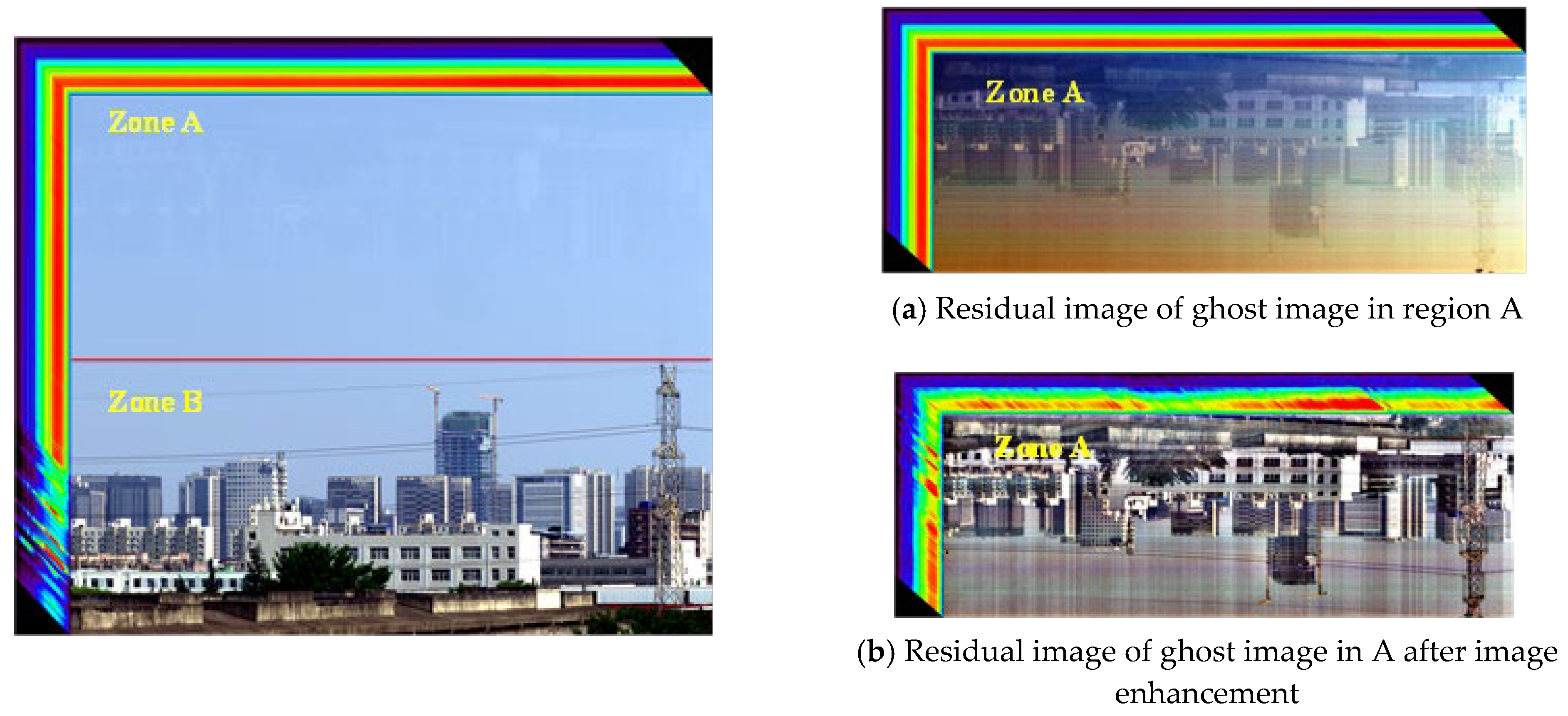

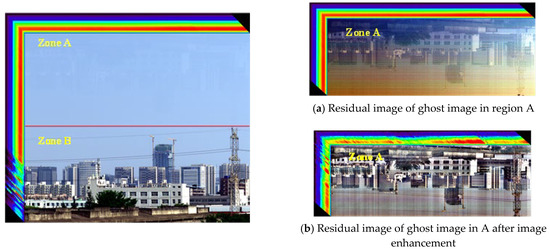

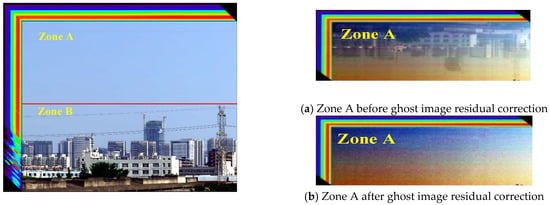

When ghost image residual images are registered with target images, the extraction of image feature points is particularly important. However, the proportion of ghost image residual energy in the sky background image is very small, and it is impossible to extract sufficient feature points for registration, so the accuracy requirements of image registration will not be met. The multi-scale CLAHE algorithm was used to enhance the target zone (Zone B) and ghost image residual zone (Zone A) of the hyperspectral image. The enhanced images are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Regional Enhancement Effect of Residual Image of the Hyperspectral Ghost Image.

Zone A is the ghost image residual zone of the hyperspectral image, while Zone B is the hyperspectral target image zone. Figure 4a,b are enhanced effect diagrams of the ghost image residual zone, and the ghost image residual in the hyperspectral image, respectively. Comparing Figure 4a,b reveals that the enhanced ghost image residual image has clear and visible contour details, as well as prominent image features. However, at the same time, the noise in the sky area is also enhanced, limiting the accuracy of image matching to some degree. In order to solve this problem, four registration algorithms with good anti-noise performance, namely, RIFT, AKAZE, SIFT, and SURF, were selected for use in comparative experiments in the matching process between ghost image residual images and target images.

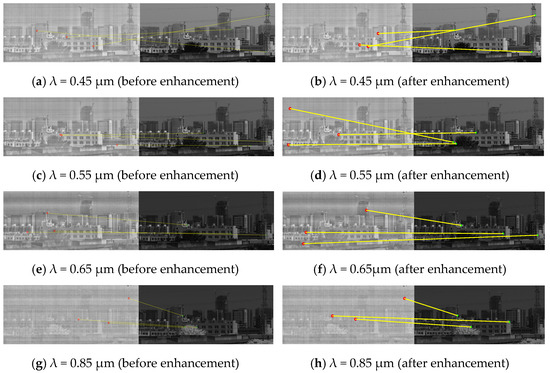

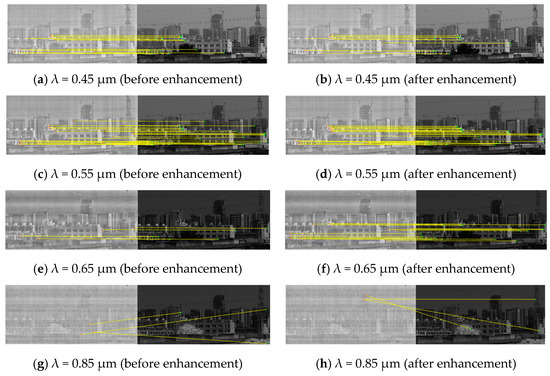

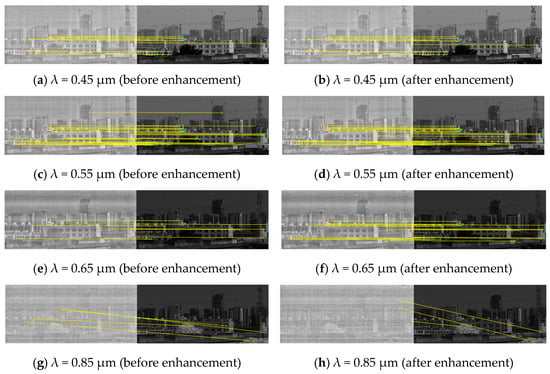

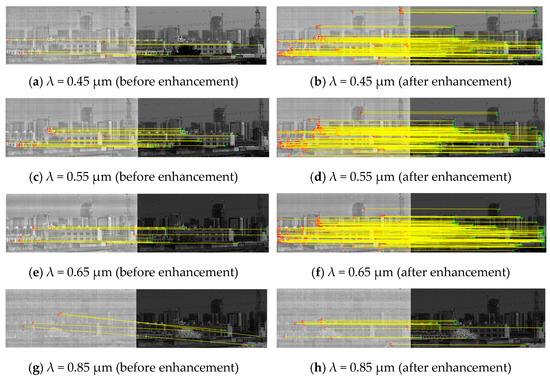

In order to address the impact of noise in the sky region, four image registration algorithms with good anti-noise performance, namely, RIFT [26], AKAZE, SIFT [27], and SURF [28], were selected for registration experiments before and after ghost image residual enhancement. The experimental results are shown in Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, demonstrating the feature point extraction and matching performance of different algorithms with wavelengths of 450 nm, 550 nm, 650 nm, and 850 nm, respectively.

Figure 5.

Comparison of Feature Point Extraction and Matching before and after Ghost Image Residual Enhancement using the RIFT Algorithm.

Figure 6.

Comparison of Feature Point Extraction and Matching before and after Ghost Image Residual Enhancement using AKAZE Algorithm.

Figure 7.

Comparison of Feature Point Extraction and Matching before and after Ghost Image Residual Enhancement using the SIFT Algorithm.

Figure 8.

Comparison of feature point extraction and matching before and after ghost image residual enhancement using the SURF algorithm.

The RIFT algorithm was used to compare the feature point extraction and matching performance regarding single-wavelength ghost image residual, Zone A, and target image, Zone B, with wavelengths of 450 nm, 550 nm, 650 nm, and 850 nm before and after enhancement, as shown in Figure 5. As shown in the figure, the feature point matching effect remains unchanged, and the accuracy is extremely low before and after ghost image residual enhancement, and the image registration effect is poor.

The AKAZE algorithm was used to compare the feature point extraction and matching performance of the single-wavelength ghost image residual, Zone A, and target image, Zone B, with wavelengths of 450 nm, 550 nm, 650 nm, and 850 nm before and after enhancement, as shown in Figure 6. Obviously, the number of extracted feature points slightly increased after ghost image enhancement, and concurrently, the feature point matching performance improved to some extent. However, there are still some feature points with low matching accuracy, and the image registration effect is still poor.

The SIFT algorithm was used to compare the feature point extraction and matching performance of the single-wavelength ghost image residual, Zone A, and target image, Zone B, with wavelengths of 450 nm, 550 nm, 650 nm, and 850 nm before and after enhancement, as shown in Figure 7. As shown in the figure, after ghost image residual enhancement, the number of feature points increases sharply, and the matching accuracy of feature points significantly improves. Compared with the RIFT and AKAZE algorithms, the effect is significantly better.

The SURF algorithm was used to compare the feature point extraction and matching performance of the single-wavelength ghost image residual, Zone A, and target image, Zone B, with wavelengths of 450 nm, 550 nm, 650 nm, and 850 nm before and after enhancement, as shown in Figure 8. As shown in the figure, after ghost image residual enhancement, the number of extracted feature points increased by 2–3 times. At the same time, there are almost no incorrectly matched feature points in each band image. This algorithm performs best among the four algorithms.

The offsets of RIFT, AKAZE, SIFT, and SURF registration algorithms in the same target image region are shown in Table 1. The SURF image registration offset is less than two pixels, meeting the image registration accuracy requirements.

Table 1.

Image Offset after Registration using Different Registration Algorithms.

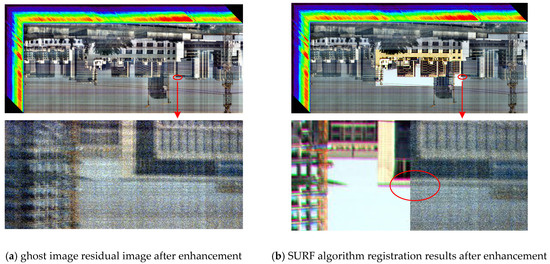

The spatial offset details of the target image and the ghost image residual image processed via the SURF algorithm optimization are shown in Figure 9 [29,30,31,32,33]. As shown in the figure, there is only a spatial dimension offset between the target image and the ghost image residual, and the offset is less than two pixels.

Figure 9.

Effect Diagram of SURF Registration Algorithm after Ghost Image Residual Enhancement.

Based on the results of the above comparative experiments, the SURF algorithm has the best image registration accuracy, and the image offset is less than two pixels after registration, meeting the requirements of image registration accuracy.

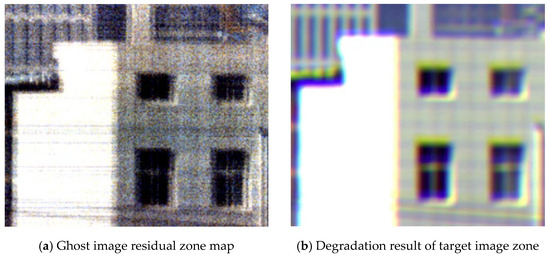

The registered ghost image residual image was subjected to two-dimensional PSF distribution fitting to obtain a degraded image of the ghost image residual. The degradation result is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Comparison of Ghost Image Residual Zone and Target Image Region Degradation.

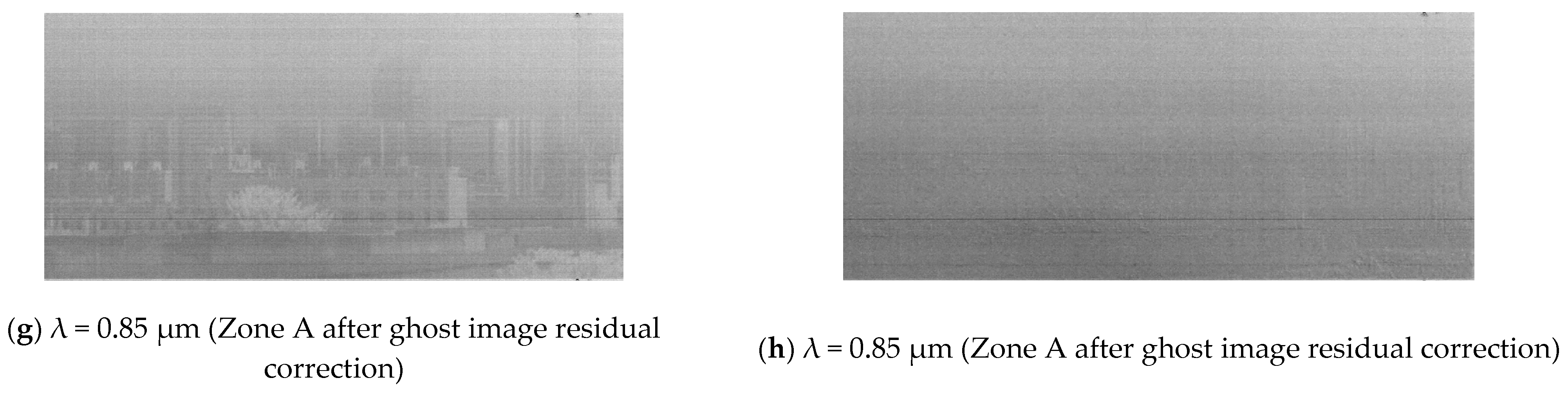

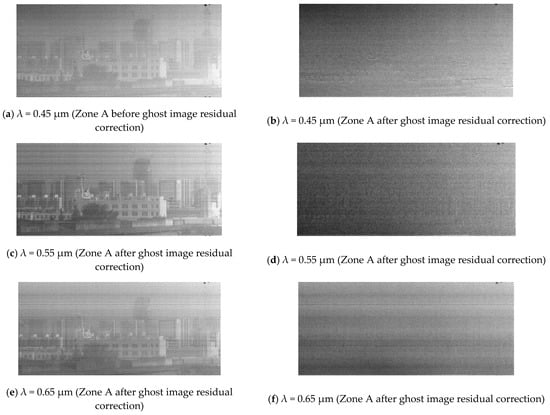

The blurred edges of the building after hyperspectral ghost image residual enhancement are shown in Figure 10a. The target image was fitted with the PSF distribution of ghost image residual, and the fitting result is shown in Figure 10b. As shown in the figure, the degraded target image edge has an energy distribution similar to that of the ghost image residual edge [34,35]. The experimental results indicate that the method of fitting the two-dimensional PSF distribution of the ghost image residual was correct. Through this method, the continuous weakening of the ghost image residual features is used as the constraint, and the target image and the ghost image residual image are repeatedly fitted. The iterative optimization results of the ghost image residual 3D data cube are shown in Figure 11a. As shown in Figure 11c, the ghost image residuals in Zone A are completely eliminated in the sky background. Simultaneously, the optimization and correction of ghost image residuals in a single-channel sky background were analyzed. The ghost image residual images with center wavelengths of 450 nm, 550 nm, 650 nm, and 850 nm after single channel correction were extracted. These ghost image residual images after correction are shown in Figure 12. As shown in the figure, after ghost image residual correction, on the premise of preserving the characteristics of the sky image, the ghost image residual spatial features and spatial contours in the sky background are basically eliminated, achieving the goal of ghost image residual correction.

Figure 11.

Ghost Image Residual 3D Cube Data Correction Results.

Figure 12.

Comparison of Single-channel Zone A Ghost Image Residuals before and after Correction.

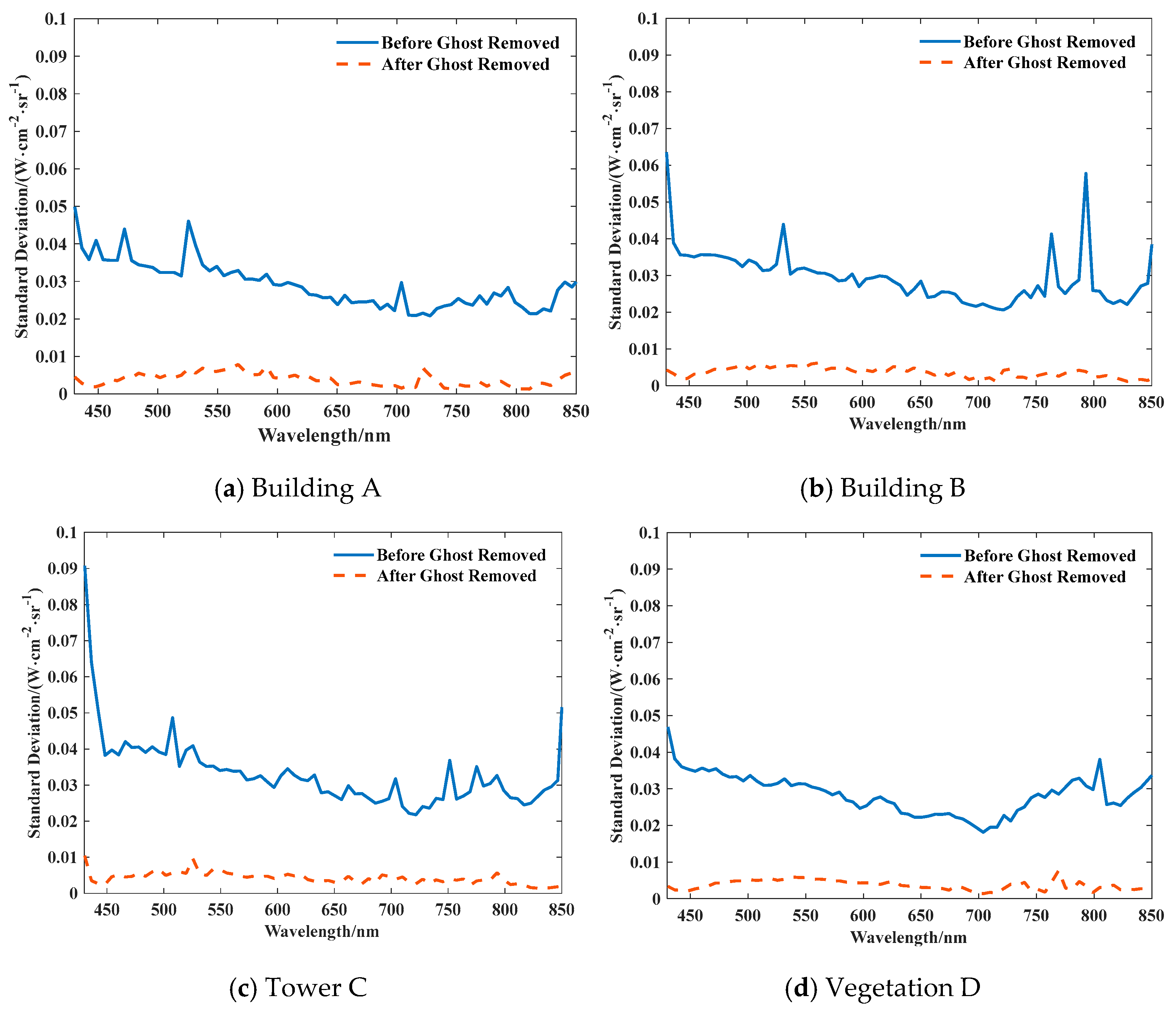

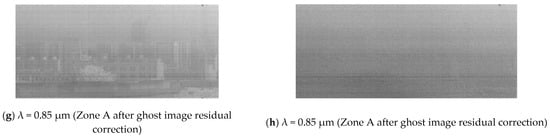

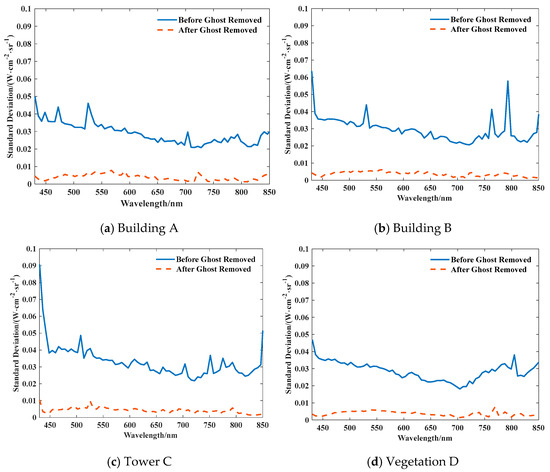

3.1. Standard Deviation and Energy Proportion of the Images of the Ghost Image Residual Before and After Correction

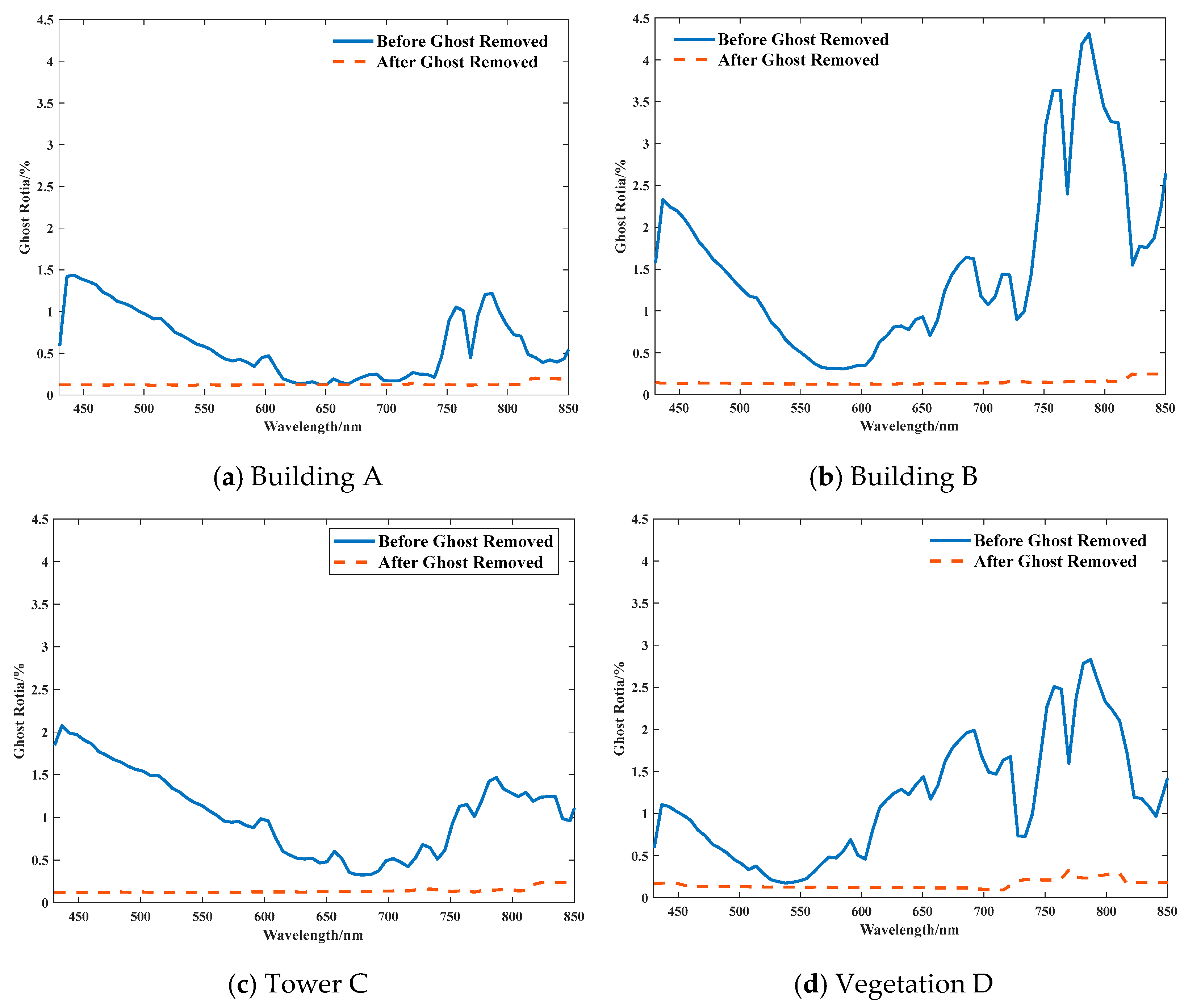

The standard deviation, as a core indicator for measuring the degree of data dispersion, can be used to evaluate the visibility of ghost image features in the sky region. The larger the standard deviation, the more obvious the ghost image residual features. Figure 13 displays the standard deviation of radiance values of the ghost image zones corresponding to typical targets before and after the removal of the ghost image residuals. As shown in the figure, the standard deviation of ghost image residual in the typical target area decreased by about 75% before and after correction. The proportion of ghost image residual energy is indicated in Figure 14. The energy proportion before and after ghost image residual correction at different wavelengths shows that the proportion of ghost image residual energy decreased from 4.6% to 0.3% after ghost image residual correction.

Figure 13.

Typical Target Ghost Image Residual Standard Deviation before and after Ghost Image Residual Correction.

Figure 14.

Energy Proportion of Ghost Image Residuals in the Target Image before and after Correction.

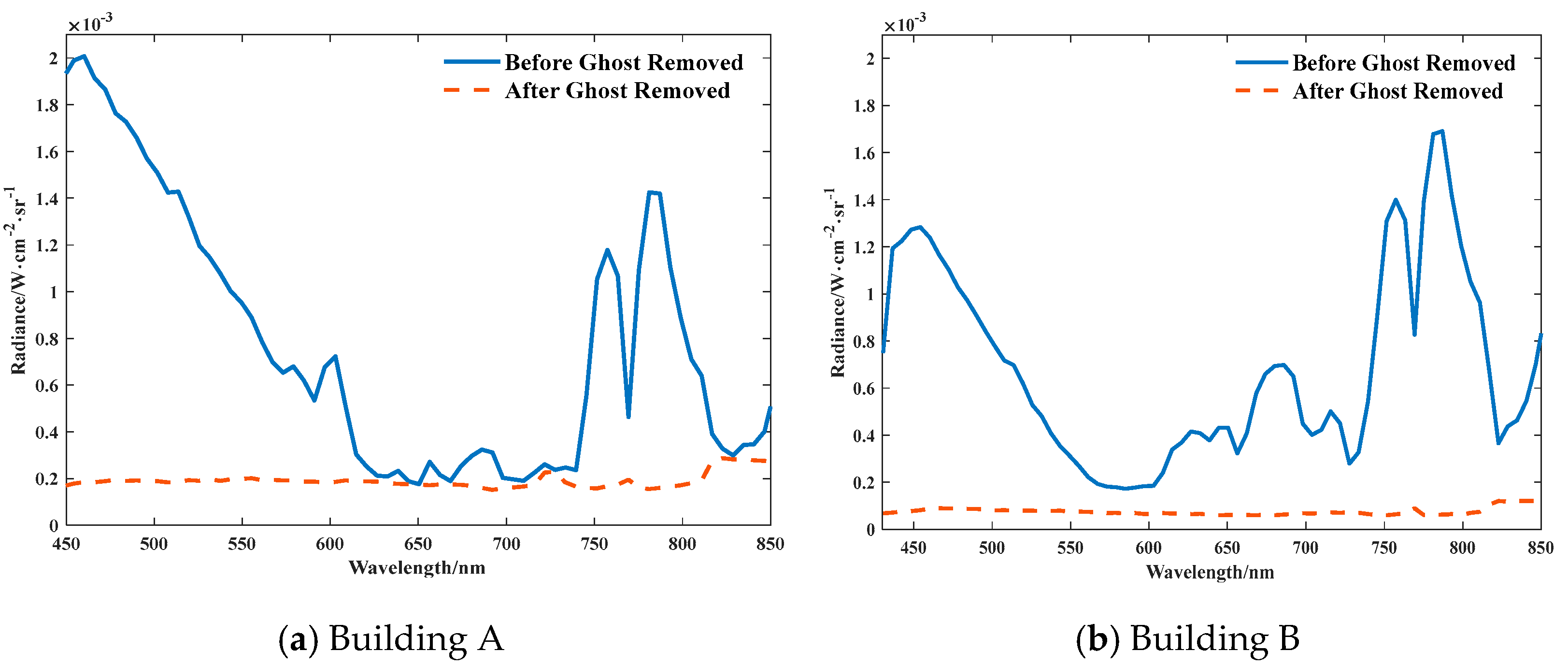

3.2. The Influence of Ghost Image Residuals Before and After Correction on Absolute Radiometric Calibration

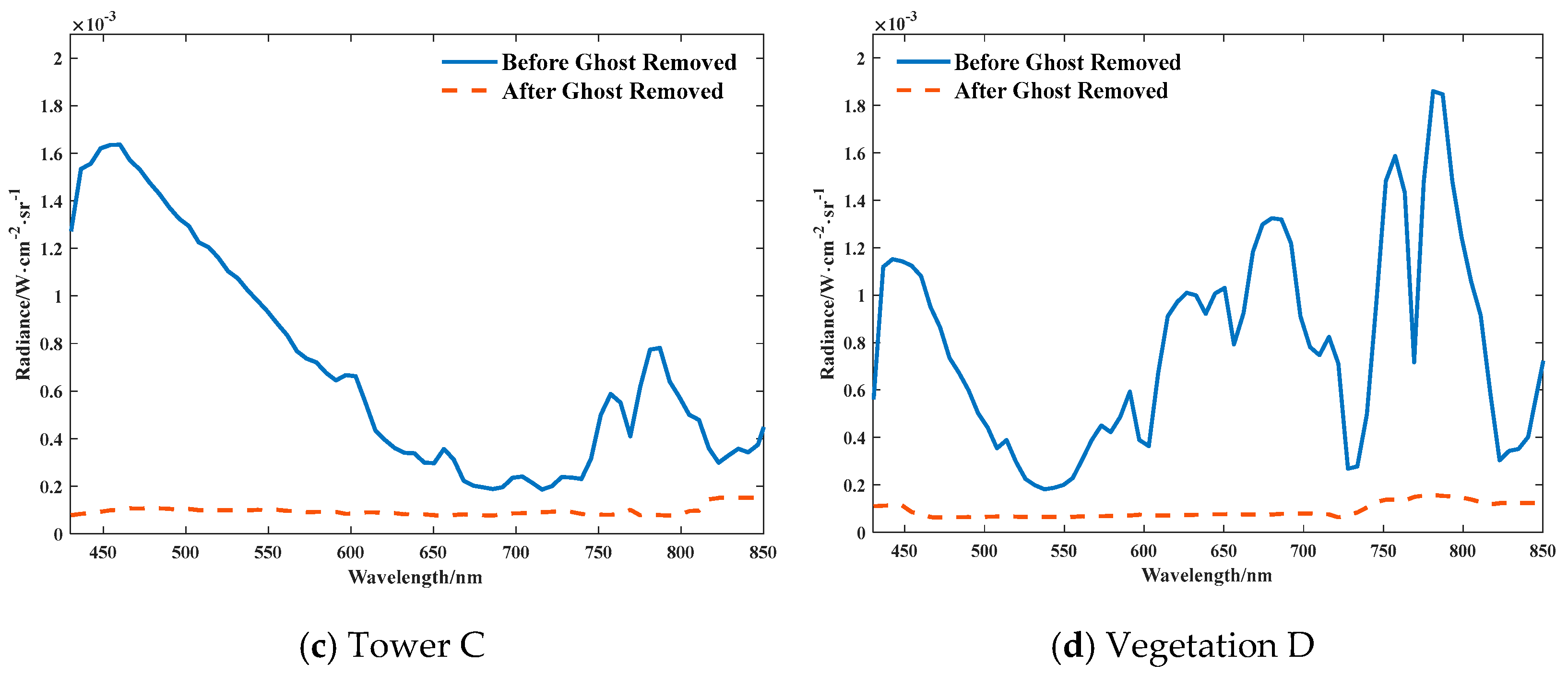

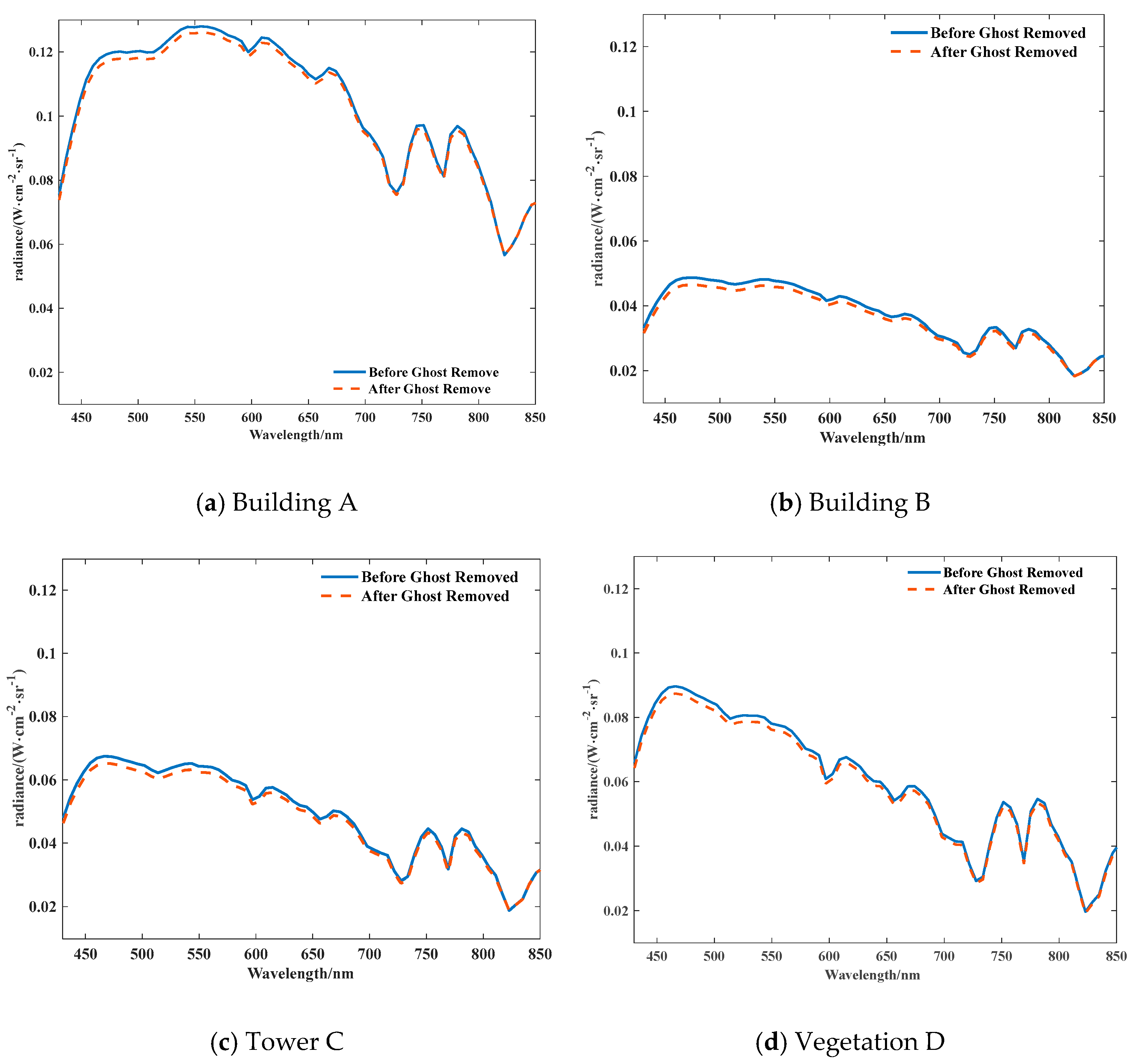

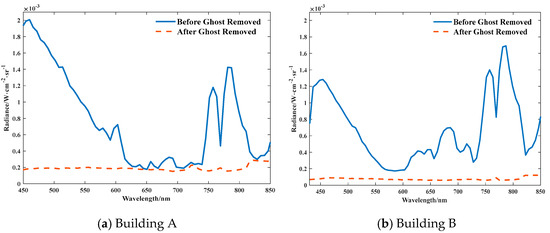

The correction of ghost image residuals has a certain impact on the spectral features of three-dimensional cube images. In order to further analyze the influence of ghost image residual correction on spectral features, the spectral radiance of typical target ghost image residuals given in Buildings A and B, Tower C, and Vegetation D before and after correction was analyzed. The results are shown in Figure 15 and Figure 16. As shown in the figures, the corrected ghost image residual radiance is very small, and the radiance regions of different wavelengths are stable.

Figure 15.

Radiance Residuals of Typical Target Ghost Images before and after Correction in the Sky Background.

Figure 16.

Spectral Curves of Ghost Images Corresponding to Different Typical Targets in the Sky Region.

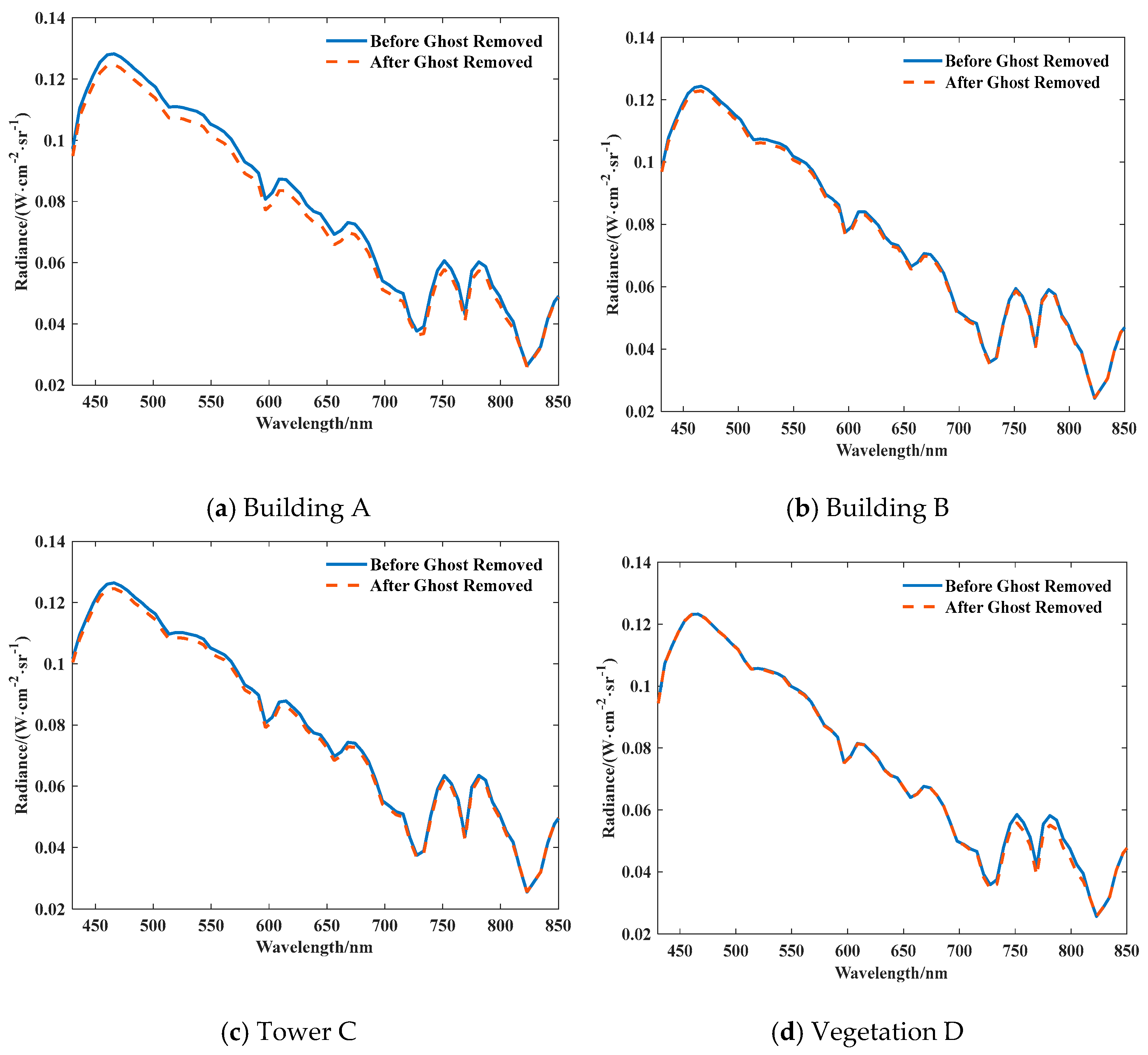

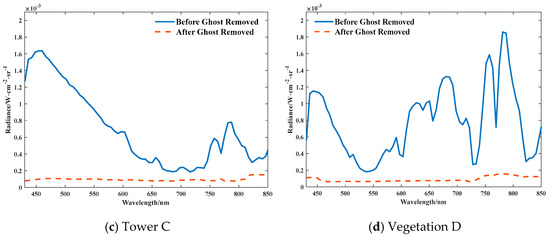

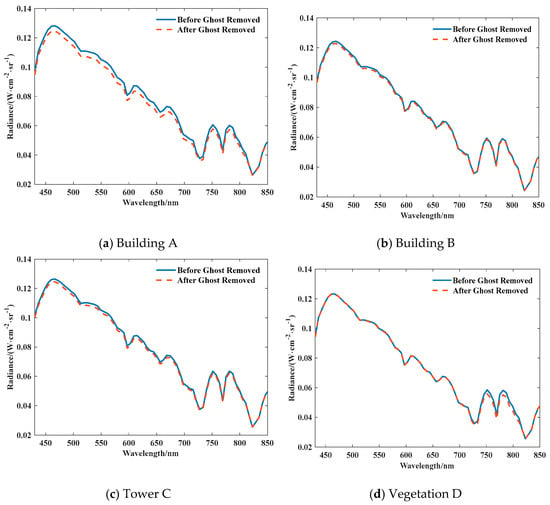

To analyze the influence of ghost image residuals on the spectral curves of typical targets before and after correction, we plotted the spectral radiance curves of a typical target ghost image residual before and after correction, as shown in Figure 17. As revealed in the figure, the spectral curve trends of four typical targets, A–D, did not change. Their spectral radiance ranges from 450 nm to 600 nm, and the amplitude of spectral radiance varies greatly, with the maximum change in amplitude being about 0.005 W·cm−2·Sr−1, accounting for 0.8% of the typical target radiance. The variation range is within the standard deviation range of the target area grayscale value and can be almost ignored.

Figure 17.

Typical Target Spectral Radiance Variation Curves before and after Ghost Image Residual Correction.

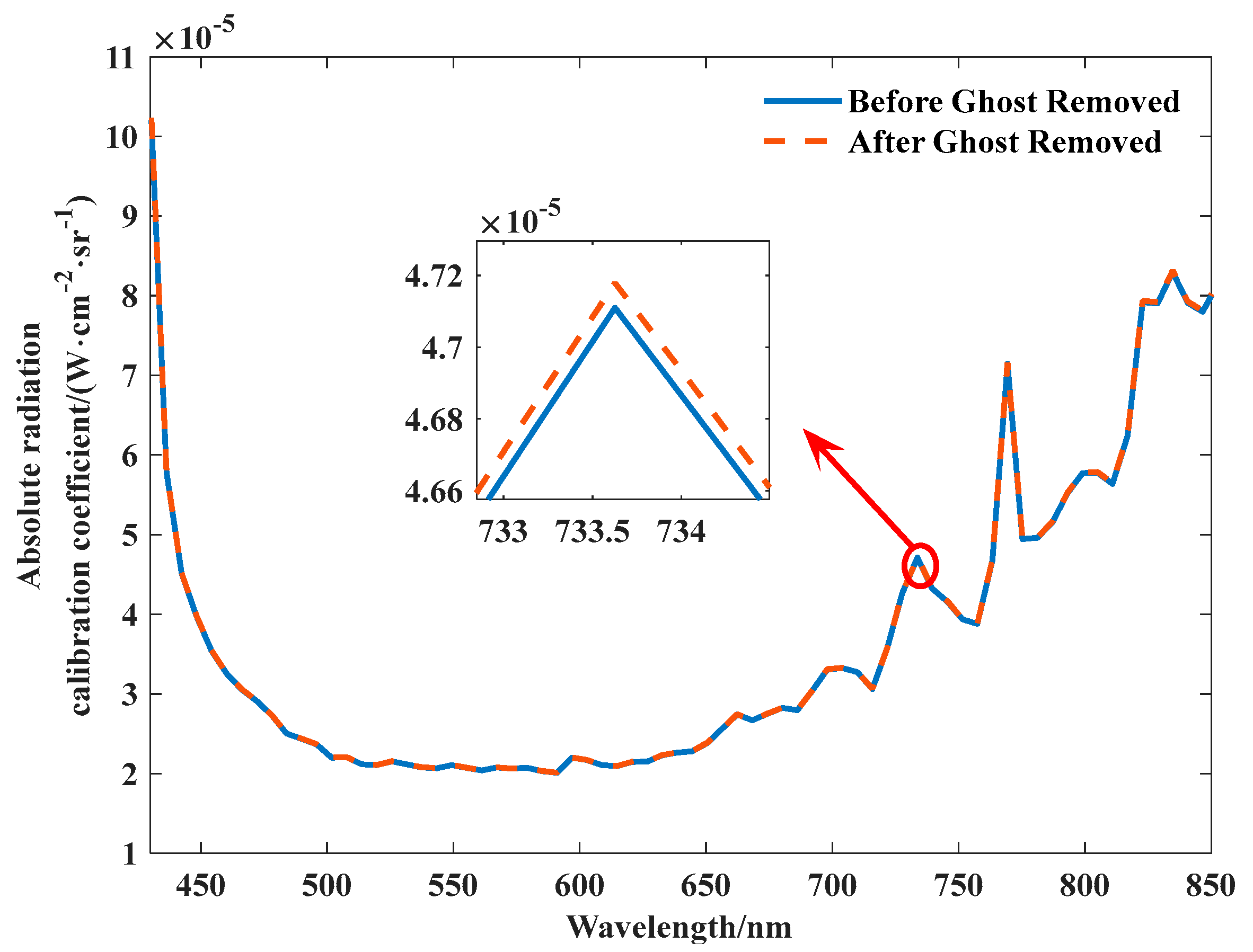

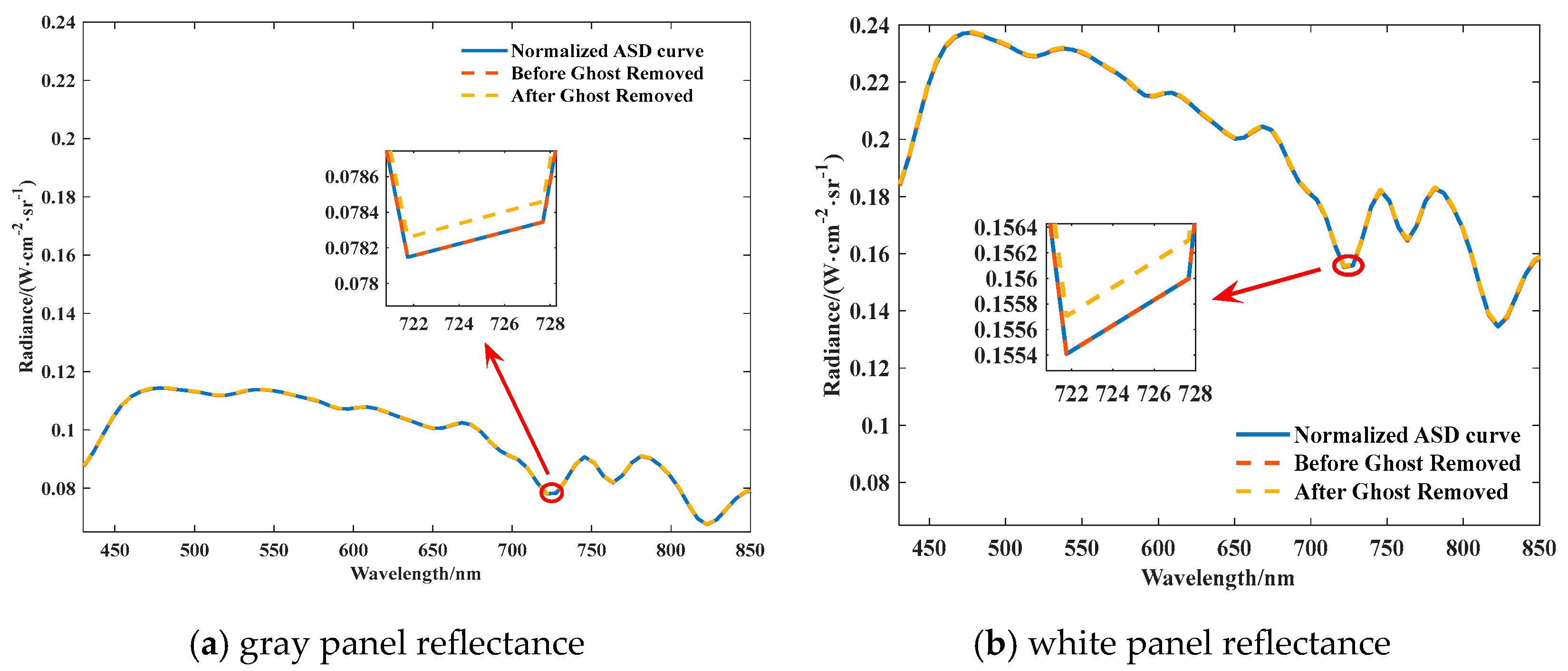

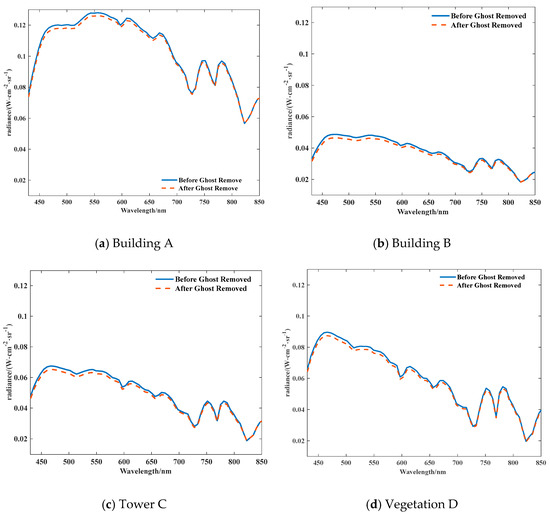

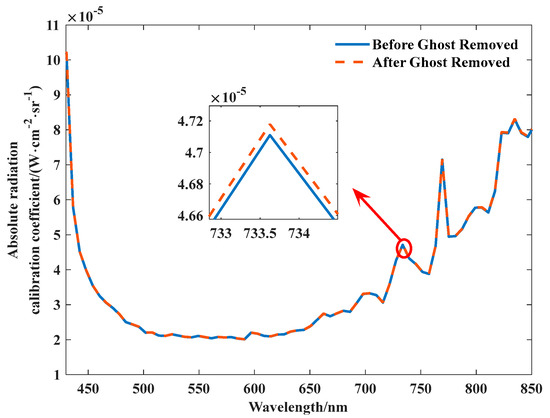

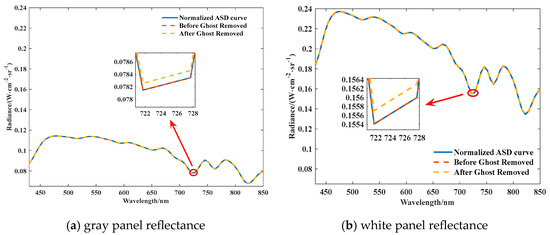

The accuracy of spectral instrument radiance is primarily depends on the radiometric calibration accuracy [36,37,38,39]. Absolute radiometric calibration accuracy correlates with absolute calibration coefficients. Analyzing the absolute calibration coefficients before and after ghost image residual correction, the influence of absolute calibration accuracy is reflected, with the absolute calibration coefficients as shown in Figure 18. Before and after ghost image residual correction, the absolute calibration coefficient curves are basically consistent. At a wavelength of 733.6 nm, the curve difference before and after correction is the largest. The amplitude difference accounts for 0.06% of the typical target radiance, and such an effect can be ignored. Finally, comparing and verifying the accuracy of absolute radiometric calibration through the calculation of ASD data with different reflectivity based on absolute calibration coefficients, we obtained the ASD prediction curves before and after ghost image residual correction under different reflectivity, as shown in Figure 19. Notably, at a wavelength of 721.7 nm, the degree of curve separation is the highest. At this moment, the radiance difference before and after ghost image residual correction is 0.0002 W·cm−2·sr−1, representing 0.25% of total radiance. This finding confirms that the absolute radiometric calibration coefficients before and after ghost image residual correction are almost completely unaffected.

Figure 18.

Curve of Absolute Radiometric Calibration Coefficients before and after Ghost Image Correction.

Figure 19.

Comparison of ASD (Absolute Spectral Difference) Calculation Data before and after Ghost Image Residual Correction under Gray and White Panel Reflectance.

As shown in the results and analysis, in cases where the impact on the target spectral curve and absolute radiometric calibration coefficient is smaller, the ghost image residual correction algorithm can achieve ghost image correction, thereby achieving its goal.

4. Conclusions

The rich spectral information of hyperspectral data makes any algorithm highly sensitive [40,41,42]. We designed a targeted ghost image residual processing method based on the analysis of ghost image residual characteristics and typical target features. The method achieved effective ghost image residual correction while preserving the spectral features and calibration coefficient integrity of the image. The experimental results show that the energy of most ghost images decreased from 4.5% to approximately 0.3%, and the spectral characteristics of ghost image residuals were effectively suppressed. Variations in the target spectral curve were less than 0.8%, indicating that the target spectral features remained unchanged, while the impact on the absolute calibration coefficient did not exceed 0.06%. These results validate that the proposed algorithm effectively eliminates ghost effects under known one-dimensional PSF distributions while preserving image information, providing a theoretical basis for hyperspectral ghost image correction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L. and M.G.; methodology, X.L.; software, S.Z.; validation, X.L. and S.L.; formal analysis, X.L.; investigation, T.C.; resources, P.W.; writing—original draft preparation, X.L.; writing—review and editing, J.Y.; visualization, T.C.; supervision, S.L.; project administration, B.H.; funding acquisition, X.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the self-deployment project of Xi’an Institute of Optics and Precision Mechanics of CAS (No. E35543Z501), State Key Laboratory of Ultrafast Optical Science and Technology Youth Foundation of Xi’an Institute of Optics and Precision Mechanics, CAS (No. 2025CKZZ-20).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in the study are included in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ewing, J.; Oommen, T.; Jayakumar, P.; Alger, R. Utilizing hyperspectral remote sensing for soil gradation. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, D.; Arora, M.K.; Tiwari, K.C.; Ghosh, J.K. Identification of most useful spectral ranges in improvement of target detection using hyperspectral data. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2019, 22, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Wang, L.; Song, L.; Ma, P.; Liao, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, X. Near-shore remote sensing target recognition based on multi-scale attention reconstructing convolutional network. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1455604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, J.; Gao, M.; Liu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Li, S. The design of an imaging spectrometer based on forearm compensation optical path multiplexing. Opt. Commun. 2025, 583, 131746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, S.; Ortega, S.; Anderssen, K.E.; Nilsen, H.A.; Heia, K. Hyperspectral imaging and deep learning for parasite detection in white fish under industrial conditions. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thome, K.J.; Biggar, S.F.; Gellman, D.L.; Slater, P.N. Absolute-radiometric calibration of Landsat-5 Thematic Mapper and the proposed calibration of the Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 1994 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Pasadena, CA, USA, 8–12 August 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Adomeit, U.; Krieg, J. Shortwave infrared for night vision applications: Illumination levels and sensor performance. In Proceedings of the SPIE Remote Sensing, 2015, Toulouse, France, 21–24 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kohler, D.D.R.; Bissett, W.P.; Steward, R.G.; Davis, C.O. New approach for the radiometric calibration of spectral imaging systems. Opt. Express 2004, 12, 2463–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.Y.; Chen, C.Z.; Zhang, J.W.; Zhang, H. Quantitative Effects of the Spectral Calibration Accuracy of the Imaging Spectrometer on the Vegetation Red Edge. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. In Proceedings of the 35th International Symposium on Remote Sensing of Environment (ISRSE35), Beijing, China, 22–26 April 2013; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2014; Volume 17, p. 012227. [Google Scholar]

- Cunnick, H.; Ramage, J.M.; Magness, D.; Peters, S. Monitoring sub-arctic wetland vegetation using nested scales of spectrometry to inform multiple endmember spectral unmixing of Sentinel-2A imagery. Environ. Res. Ecol. 2025, 4, 035005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Atta, A.; Deng, X.; Tariq, A.; Hussain, S.; Liao, L.; Faisal, M.; Gao, C. Quantitative inversion modeling of surface gold abundance based on remote sensing imagery and geochemical Data: An example from Tasiast-Tijirit gold district, Mauritania. Phys. Chem. Earth 2025, 140, 103991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernousov, A.D.; Agapov, P.D. Deep Learning Ghost Polarimetry of Two-Dimensional Objects with Amplitude Anisotropy. Mosc. Univ. Phys. Bull. 2025, 80, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setty, S.; Nadig, D.S. New ghost image on OPG. Br. Dent. J. 2025, 238, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Ke, F.; Pan, Y.; Gao, S.; Bai, J.; Wang, K. Real-time ghost image characterization for panoramic annular lenses. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 22998–23014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Sun, M.; Yu, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, X. Computational ghost image encryption method based on sparse speckles. Phys. Scr. 2024, 99, 025114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizer, S.M.; Amburn, E.P.; Austin, J.D.; Cromartie, R.; Zuiderveld, K. Adaptive histogram equalization and its variations. Comput. Vis. Graph. Image Process. 1987, 39, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhavi, N.; Srilakshmi, T.; Swetha, M.; Bhavani, C.; Rao, T.R. Constructing and Developing Contrast-Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization Method to Improve PSNR and UIQI Parameters in MRI Images Compared to Median Filtering. Recent Dev. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 546–552. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C.; Wang, H.; Yan, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Y. A Review of Optical Image Enhancement for Extreme Space Environments. Adv. Astronaut. 2025, 8, 171–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendaoui, R.; Abdellaoui, M.; Douik, A. Synthesis of spatio-temporal interest point detectors: Harris 3D, MoSIFT and SURF-MHI. In Proceedings of the 2014 1st International Conference on Advanced Technologies for Signal and Image Processing (ATSIP), Sousse, Tunisia, 17–19 March 2014; pp. 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Chiliaeva, V.; Almansa, A.; Ferrec, Y.; Gaucel, J.M.; Gazzano, O.; Goudail, F.; Krawczyk, R.; Sauer, H. Impact of image registration errors on the quality of hyperspectral images in imaging static Fourier transform spectrometry. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 7012–7029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez, Á.; Argüello, F.; Heras, D. Alignment of Hyperspectral Images Using KAZE Features. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, A.; Fétick, R.J.L.; Neichel, B.; Beltramo-Martin, O.; Fusco, T. Improved prior for adaptive optics point spread function estimation from science images: Application for deconvolution. Astron. Astrophys. 2023, 673, A72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.; Wu, X.; Yang, X.; Huang, Y.; Cai, B.; Cai, D. Astronomical Image Restoration and Point Spread Function Estimation with Deep Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advances in Optical Astronomical Instrumentation 2019, Melbourne, Australia, 8–12 December 2019; Volume 11203, pp. 42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Marion, R.; Michel, R.; Faye, C. Atmospheric correction of hyperspectral data over dark surfaces via simulated annealing. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2006, 44, 1566–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnevali, P.; Coletti, L.; Patarnello, S. Image processing by simulated annealing. Read. Comput. Vision. 1987, 29, 551–561. [Google Scholar]

- Henshaw, C.; O’Shaughnessy, R.; Cadonati, L. Implementation of a generalized precession parameter in the RIFT parameter estimation algorithm. Class. Quantum Gravity 2022, 39, 125003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tareen, S.A.K.; Saleem, Z. comparative analysis of SIFT, SURF, KAZE, AKAZE, ORB and BRISK. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Computing, Mathematics and Engineering Technologies (iCoMET), Sukkur, Pakistan, 3–4 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Huang, D.; Qin, N.; Zhang, Y.; Ni, S. An improved subpixel-level registration method for image-based fault diagnosis of train bodies using SURF features. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2021, 32, 115402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanin, M.I.A.; El-Samie, A.E.F.; Banby, M.G. A real-time approach for automatic defect detection from PCBs based on SURF features and morphological operations. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2019, 78, 34437–34457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhan, L.; Zhao, Y.; Xiong, S.; Lu, X. VGRSS: Datasets and Models for Visual Grounding in Remote Sensing Ship Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote. Sens. 2025, 63, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Xiong, S.; Lu, X. Bilinear Parallel Fourier Transformer for Multimodal Remote Sensing Classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote. Sens. 2025, 63, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Chen, Y.; Yao, R.; Xiong, S.L.; Xiong, S.W.; Lu, X. SSPNet: Spatial-Spectral Perception Network for Mineral Hyperspectral Image Classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote. Sens. 2025, 63, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Chen, Y.; Xiong, S.; Lu, X. Hyperspectral Image Classification via Cascaded Spatial Cross-Attention Network. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2025, 34, 899–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, P. Remote sensing image watermarking based on motion blur degeneration and restoration model. Optik 2021, 248, 168018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Huang, H.; Du, L. Reliability analysis on competitive failure processes under fuzzy degradation data. Appl. Soft Comput. J. 2010, 11, 2964–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Xu, N.; Mao, J.; Sun, L.; Shi, E.; Hu, X.; Chen, L.; Yang, Z.; Si, F.; et al. Preflight spectral calibration of the ozone monitoring suite-nadir on FengYun 3F satellite. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Wu, X. An integrated method to improve the GOES Imager visible radiometric calibration accuracy. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 164, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradburn, J.; Aksoy, M.; Apudo, L.; Vukolov, V.; Ashley, H.; VanAllen, D. ACCURACy: A Novel Calibration Framework for CubeSat Radiometer Constellations. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Qi, C.; Hu, X.; Gu, M.; Zhang, P. Fy-3d Hiras Radiometric Calibration and Accuracy Assessment. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 58, 3965–3976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, L.; Xiong, S.; Lu, X. A Joint Saliency Temporal-Spatial-Spectral Information Network for Hyperspectral Image Change Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote. Sens. 2024, 62, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yao, R.; Xiong, S.; Lu, X. Context-driven and sparse decoding for Remote Sensing Visual Grounding. Inf. Fusion 2025, 123, 103296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Rong, Y.; Xiong, S. Progressive language-aware encoding and decoding for referring expression comprehension. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2025, 68, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).