1. Introduction

Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) offers significant advantages for rice monitoring, particularly in tropical regions, such as the Philippines, where cloud cover limits optical observations. The predominance of clouds poses a major challenge for rice monitoring, especially during the monsoon season when the majority of rice is grown [

1,

2]. The backscatter coefficient has been shown to be a reliable indicator for monitoring rice fields as its temporal response is distinct for rice and varies over time in relation to the different growth stages of the crop, e.g., [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. This unique temporal backscatter signature enables the distinction of rice from other non-rice land covers.

To date, most studies using SAR have concentrated on monitoring entire rice-growing regions, generating information on total rice production, yield estimates, and areas at risk from extreme weather conditions [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. However, ecosystem-specific information remains limited. Currently, the information provided to stakeholders typically represent aggregated rice areas without distinguishing between different rice ecosystems due to the absence of appropriate classification methodologies. Rice is cultivated in different ecosystems, which vary in water availability, cultural management practices, productivity, and susceptibility to climatic variability. For instance, irrigated rice ecosystems are bunded rice fields with controlled irrigation and have generally higher production, whereas rainfed rice ecosystems are also bunded but rely solely on rainfall and are exposed to water stress and climatic fluctuation [

9,

10,

11]. Rainfed rice, particularly important in South and Southeast Asia, accounts for 20% of total rice production [

10]. These ecosystems differ substantially in productivity; for example, in the Philippines, average yields in 2023 were 4.51 tons per hectare for irrigated rice and 3.34 tons per hectare for rainfed rice [

11]. Given these differences in hydrological and crop management, developing methods to accurately discriminate between rice ecosystems is essential for effective monitoring and agricultural decision-making.

Previous studies using optical remote sensing have attempted to map irrigated and rainfed ecosystems in Asia at regional scales [

12,

13]. These studies successfully identified irrigated and rainfed rice areas in South and Southeast Asia based on the flooding and transplanting stages, using vegetation and water indices such as NDVI, EVI, and LSWI. However, they also highlighted key limitations in accurately detecting small or fragmented rainfed fields, which are common in these areas and particularly affected by variable rainfall and planting schedules. Other studies have used phenology-based approaches in optical [

14,

15,

16] and SAR data [

17,

18,

19], as well as data fusion methods integrating SAR and GIS information [

20,

21], to discriminate between irrigated and rainfed rice. Phenology-based and temporal vegetation indices have proven to be useful tools for distinguishing rice ecosystems; however, persistent cloud cover during the monsoon season hinders accurate delineation. The use of multi-temporal and different polarization SAR images has improved the detection of rainfed rice, particularly under waterlogged conditions [

22]. Rainfed single-cropping systems (unfavorable rainfed rice) are also easier to detect due to their distinct multi-temporal backscatter trends [

23]. Nonetheless, only subtle differences are often observed between the backscatter time-series of irrigated and favorable rainfed rice [

22], making different ecosystems discrimination more challenging than rice/non-rice classification. These limitations underscore the need for more advanced approaches that can better capture ecosystem-level variability. Advancements in rice phenology monitoring have further strengthened this direction, demonstrating that multi-temporal observations from SAR sensors can reliably detect crop development phases even under persistent cloud cover. Studies have shown that SAR backscatter is strongly linked to structural changes in rice plants, enabling stage-by-stage monitoring and providing greater temporal continuity than optical-based approaches, e.g., [

3,

4,

5,

17,

18,

19,

23]. These developments highlight the increasing potential of SAR for operational, phenology-driven monitoring, particularly in regions where cloud-free optical data are limited.

One promising approach to address these limitations is the use of polarimetric SAR data, which provides additional information on scattering mechanisms and surface–canopy interactions. Polarimetric parameters, which are derived from SAR backscatter, allow the characterization of how radar signals interact with rice fields at different rice stages and in canopy-water condition. Originally, polarimetric decomposition was developed for fully polarimetric sensors such as RADARSAT-2 and ALOS PALSAR; however, the availability of these sensors is limited in most areas. Currently, with systems such as Sentinel-1, it is now possible to obtain polarimetric information using dual-polarization (dual-pol) data, though with some limitations. Dual-pol data provides a less comprehensive scattering mechanism which creates strong interpretational challenges. For instance, it is unable to fully determine certain parameters [

24,

25]. Dual-pol SAR systems, including Sentinel-1 (C-band) and TerraSAR-X (X-band), allow the extraction of parameters such as entropy (H), anisotropy (A), and alpha (α), which describe the complexity and dominance of scattering types—surface, volume, or double-bounce [

25,

26].

Previous research has demonstrated the potential of multi-temporal SAR polarimetry for monitoring irrigated rice. Both dual-pol [

26,

27,

28,

29] and fully polarimetric [

30,

31,

32] data have shown significant correlations between decomposition parameters and rice growth stages, as well as biophysical variables such as biomass, vegetation water content (VWC), and plant height. The relationship between the radar scattering mechanisms and crop growth stages arises from canopy structure changes, plant geometry and water content. During early growth stages, surface scattering dominates due to standing water beneath sparse vegetation, whereas volume scattering becomes prominent during reproductive stages as the canopy becomes denser. Water management may influence these stage-dependent scattering transitions. In irrigated systems, continuous water control produces more stable and predictable scattering behavior. Thus, it is assumed that distinct scattering responses observed across growth stages and irrigation regimes can serve as reliable indicators for discriminating rice ecosystems and monitoring phenological development. The correlation between scattering mechanisms and growth stages establishes the theoretical basis for using polarimetric parameters to differentiate ecosystems. However, despite this substantial progress in irrigated rice monitoring, limited research has focused on rainfed systems where dynamic hydrological conditions may generate unique scattering behaviors that can enhance ecosystem distinction.

Rainfed rice areas are vulnerable to delayed rainy season, dry spells and extreme climate conditions, which result in low and less stable yields [

33,

34]. These areas can be further categorized into favorable (rainfed lowland) and unfavorable rainfed systems. The favorable rainfed rice is defined as a rainfed ecosystem that can cultivate whole-year-round or for at least two cropping seasons per year [

34]. It has considerable potential for yield improvement when supported by appropriate monitoring and management interventions. Discriminating these systems through SAR polarimetry can, therefore, provide valuable insights for targeted interventions, risk reduction, and climate adaptation strategies. With the different SAR sensors’ (Sentinel-1B and ALOS PALSAR-2) penetration ability and response, the polarimetric parameters may offer different perceptions for characterizing irrigated and favorable rainfed rice ecosystems.

In this study, dual-polarization decomposition parameters were used to discriminate irrigated and favorable rainfed rice ecosystems. The study sites were located in selected municipalities within the province of Iloilo, Philippines, one of the country’s major rice-producing areas that includes both irrigated and rainfed ecosystems. Multi-temporal analyses of dual-pol Sentinel-1B (S1B) and ALOS PALSAR-2 (ALOS2) data were conducted to evaluate the polarimetric responses of these ecosystems across different rice growth stages. The decomposition parameters were analyzed to capture the dominant scattering mechanisms by which these scattering behaviors differ in magnitude and timing between irrigated and favorable rainfed rice ecosystems due to variations in water management, flooding duration, and canopy structure, providing a robust basis for ecosystem discrimination. Specifically, the study objectives were to (i) identify the temporal backscatter and polarimetric behavior of irrigated and favorable rainfed rice, (ii) determine discriminating parameters between the two ecosystems, and (iii) evaluate their potential for classification and monitoring. By extending polarimetric SAR analysis to favorable rainfed rice, this work contributes to more comprehensive ecosystem monitoring, supporting yield improvement strategies and climate-smart agricultural planning.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Data

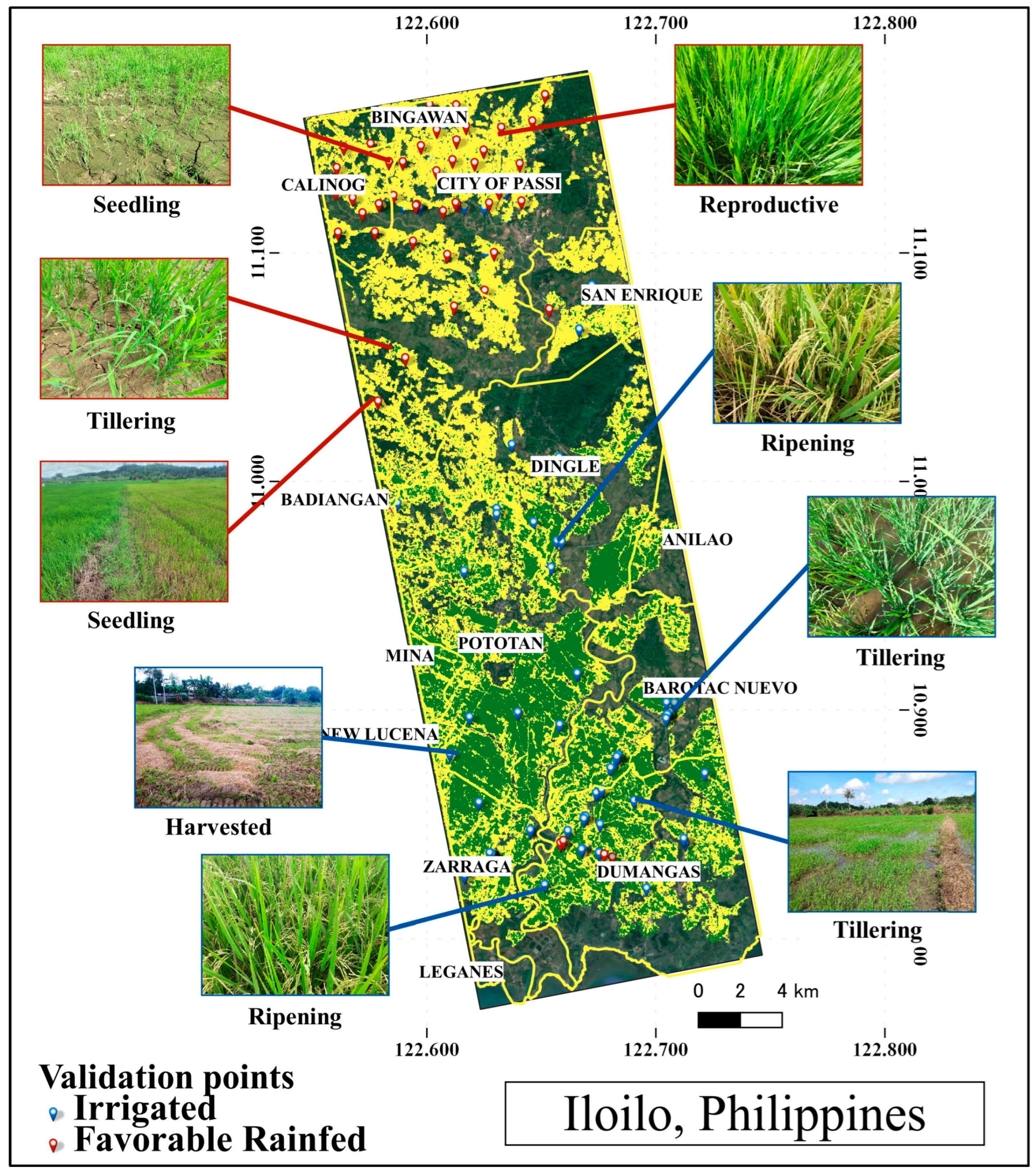

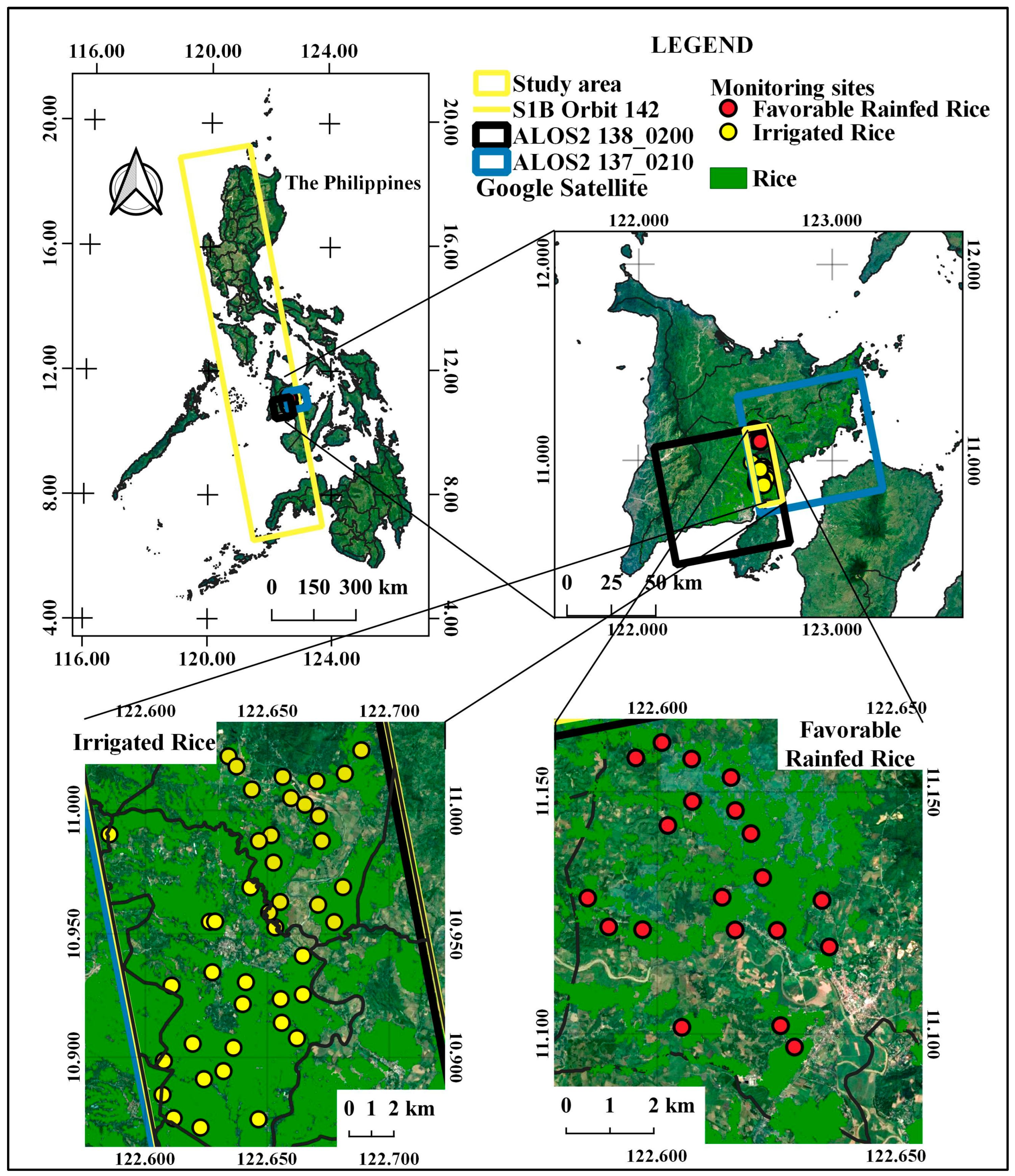

The study sites were located within the irrigated and favorable rainfed rice ecosystems in the province of Iloilo, Philippines (

Figure 1). The province is situated in the center of the Philippine archipelago (World Geodetic System 1984: EPSG: 4326, 10.69694° N, 122.56444° E) and is known as the rice granary of the region with rice as its major crop production [

33]. The province has a Type 3 climate based on Philippine Modified Coronas’ Climate Classification, characterized by seasons that are not very pronounced, relatively dry from November to April, and wet during the rest of the year, providing favorable conditions for rice production, including in rainfed ecosystems.

A total of sixty (60) monitoring fields were selected across three municipalities, Passi City, Dingle, and Pototan, comprising 40 and 20 rice fields in irrigated rice and favorable rainfed rice ecosystems, respectively (

Table 1). The sites were selected based on the availability of ground-truth data and multi-temporal ALOS2 acquisition to cover the two planting semesters in the area. The Philippine Department of Agriculture defined these planting semesters based on the planting dates: Semester 1 covers planting dates from September 16 to March 15, while Semester 2 spans from March 16 to September 15 [

35]. The monitoring fields were part of the project Philippine Rice Information System (PRiSM), the first operational rice monitoring system in Southeast Asia that utilizes remote sensing, climatic and soil data, and information and communication technology (ICT). Field data collection for these sites began in 2018 [

6]. The ground-truth data collected, such as rice stages and farmers’ management practices, served as a reference for interpreting and validating the observed remote sensing trends.

The study covered two planting semesters in the province from 2019 Semester 2 to 2020 Semester 1. The acquired SAR images were selected to ensure coverage of the different rice phases and stages. The analysis in this study was conducted based on these defined stages and phases.

The daily weather data, such as precipitation (mm/day) of the province, were downloaded from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Langley Research Center (LaRC) Prediction of Worldwide Energy Resource (POWER) Project funded through the NASA Earth Science/Applied Science Program. The precipitation data were used to monitor the rice ecosystems, with particular attention to rainfed areas that depend primarily on rainfall for irrigation.

2.2. Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) Imagery

A total of 37 SAR images were selected for this study, 28 S1B and 9 ALOS2 acquisitions (

Table 2). The images covered two planting semesters within the study area. The SAR images from the 2019 Semester 2 to 2020 Semester 1 were downloaded from Copernicus Sentinel Open Access Hub for S1B and ALOS2 images were ordered from Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) G-Portal through the 3rd Research Announcement on Earth Observations (EO-RA 3) by Earth Observation Research Center (EORC).

S1B, part of the Sentinel-1 constellation developed by the European Space Agency [

36], is a C-band SAR sensor operating at a 5.6 cm wavelength with a 12-day revisit cycle. Two types of S1B datasets were utilized: GRD Level-1 products for backscatter analysis and SLC Level-1 products for polarimetric decomposition. In contrast, ALOS2, the successor mission of JAXA’s ALOS program, is an L-band SAR sensor operating at a 23.9 cm wavelength with a 14-day revisit period, although image acquisitions over the study area were less frequent. CEOS Level-1.1 datasets were obtained for ALOS2 and used for both backscatter values and polarimetric decomposition processing. Both S1B and ALOS2 provided dual-polarization data, VH–VV and HH–HV, respectively, used in the analysis.

2.3. Image Processing

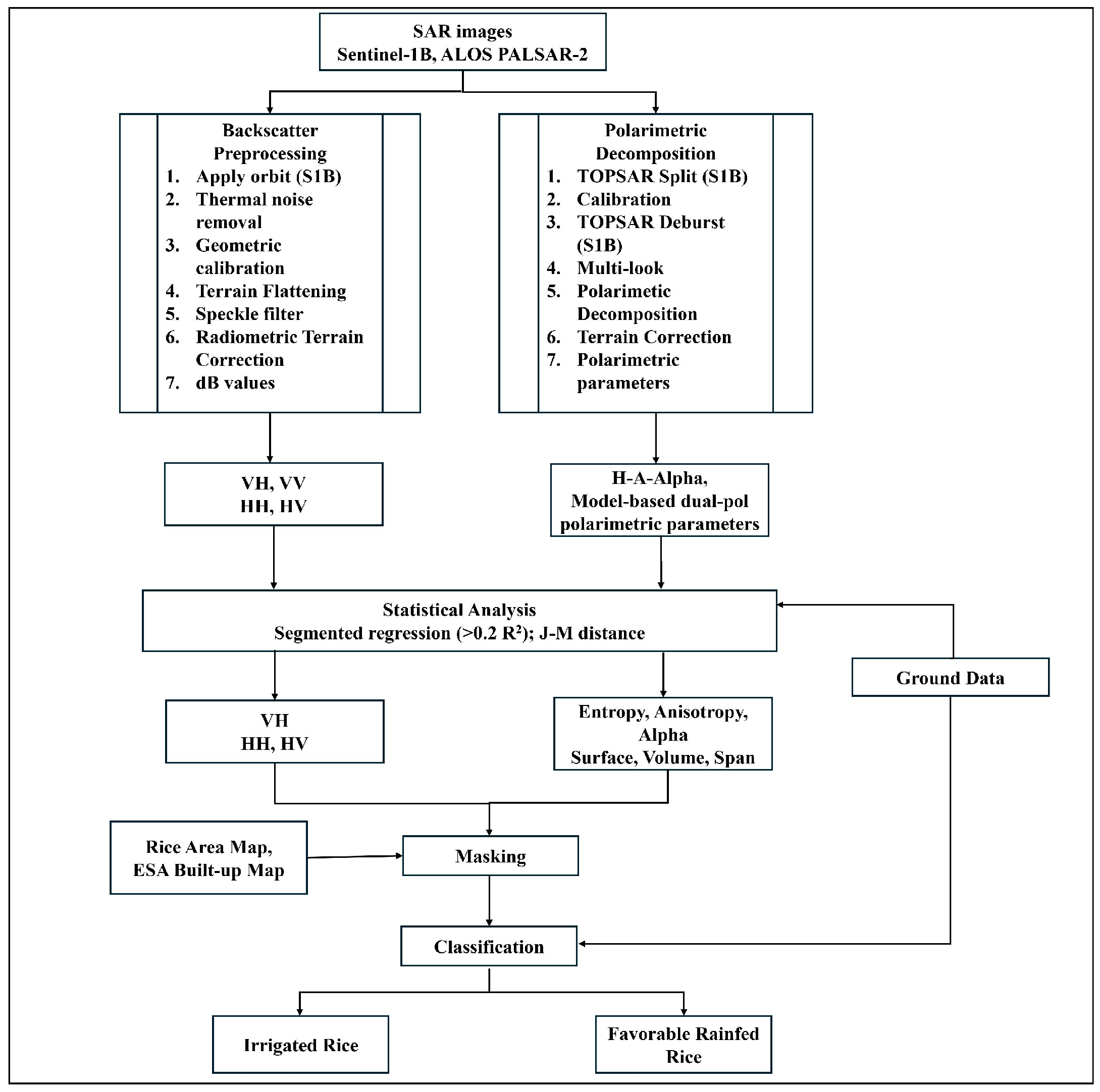

The processing chain of S1B and ALOS2 was carried out in SNAP 11.0 software as shown in

Figure 2. The images were preprocessed to generate multi-temporal backscatter in dB values and polarimetric parameters.

To obtain the backscatter in dB values, several preprocessing steps with specific parameters were performed. First, geometric calibration was conducted to generate sigma (σ°), beta (β°), and gamma nought (γ°), with β° subsequently used for terrain flattening. Terrain flattening, based on the algorithm of David Small [

37], was applied to minimize radiometric variability caused by topography while preserving that associated with land cover. This step was important given the varied terrain of the province, where rainfed rice fields are often located in valleys. Speckle filtering was then applied using the Refined Lee filter, which preserves edges, linear features, point targets, and texture information [

38]. Radiometric and terrain correction were subsequently performed using the Range-Doppler Terrain Correction method, with SRTM 1Sec HGT (Auto Download) used as the digital elevation model (DEM), bilinear interpolation for resampling, and UTM Zone 51N as the map projection. This step ensured consistency and comparability across sensors with differing imaging geometries [

37].

For Sentinel-1B data, additional preprocessing included orbit file application to improve geolocation accuracy using precise satellite ephemeris data and thermal noise removal using look-up tables (LUTs) embedded in the Sentinel-1 level 1 products. Finally, γ°, the output from the terrain-flattening process, was used in this study, as it enables more accurate comparisons of backscatter properties across surfaces with varying slopes [

37].

On the other hand, since the polarimetric decomposition was originally developed for full polarization data, several methods were modified to extract the polarimetric parameters from dual-pol SAR images. In this study, two polarimetric decomposition approaches were employed: the H-A-α decomposition and the model-based dual-pol decomposition. The preprocessing chain of both S1B and ALOS2 shown in

Figure 2 included importing of the SAR images, calibration, multi-look, polarimetric speckle filter application, polarimetric decomposition, terrain correction, and extraction of different polarimetric parameters. Additional steps specific to S1B included orbit file application, TOPSAR split, and debursting. The orbit file application provided accurate satellite positioning, while TOPSAR split was used to select the area of interest from the three subswaths (IW1, IW2, IW3). Debursting was then applied to merge all bursts into seamless images. The Refined Lee filter with 5 × 5 window size was applied to remove the speck to reduce speckle while preserving textural information. Multi-look (azimuth looks: 1 and range looks: 4) was performed before performing polarimetric decomposition to acquire reduced speckle noise and ground range square pixel. Finally, terrain correction was last to be performed to convert the image into a UTM Zone 51N map coordinate system.

The H-A-α decomposition is a modified Cloude–Pottier method [

39,

40] adapted for dual-pol SAR which derives three parameters through eigenvalue–eigenvector analysis of the coherency matrix. The parameters qualitatively describe the scattering process and give insight into scattering mechanisms [

24,

25,

40]. Entropy (H) quantifies the randomness of scattering. Values range from 0 to 1, where 0 represents the single scattering mechanism and 1 represents all scattering mechanisms and completely random scattering [

24,

40]. Anisotropy (A) measures the relative importance of secondary scattering mechanisms. Values also range from 0 to 1, where low values (~0) indicate that secondary scattering mechanisms contribute nearly equal strength, while high values (~1) suggest that one secondary scattering mechanism strongly dominates over the other [

24,

39,

40]. Alpha (α) defines the dominant scattering type. It represents the average scattering mechanisms of the target, allowing the dominant scattering type to be identified [

24,

25]. Although dual-pol decomposition has limitations in separating scattering mechanisms compared to quad-pol systems, it has proven effective in vegetation monitoring such as forests [

39] and winter wheat [

41]. This creates an opportunity to use polarimetry in places where full polarimetric data are unavailable.

The model-based dual-pol decomposition, which is based on the Stokes vector formalism, decomposes dual-pol data into separate scattering mechanisms which can yield quantitative estimates of scattering powers and associated polarimetric parameters [

24,

42]. There are seven parameters generated from the method in SNAP: alpha (α), delta (δ), ratio, rho (ρ), span, surface scattering, and volume scattering. These parameters provide a physically interpretable framework for analyzing and quantifying scattering mechanisms. Alpha is similar to the H-A-α decomposition alpha. Surface scattering refers to the radar backscatter generated when the signal reflects once from a relatively smooth surface, such as bare soil or water, before returning to the sensor. Commonly modeled as Bragg scattering, it is most prominent over flat, moist, or water-covered surfaces. In contrast, volume scattering refers to the radar backscatter produced when the radar signal penetrates and interacts with a medium containing randomly oriented particles, such as rice tillers, leaves and panicles [

43]. The span parameter is defined as the total backscatter and sum of all polarimetric intensities. It represents the combined scattering mechanisms of surface, double-bounce and volume scattering [

39,

42]. Although constrained by reduced polarimetric information compared to quad-pol systems, it remains effective for vegetation and crop monitoring, particularly in operational applications using S1B or ALOS2.

For further analysis, all the preprocessed data of backscatter and polarimetric images were stacked together using the co-register tool.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The backscatter (γ°) and polarimetric parameters were extracted from the monitoring fields to determine which parameters to use in the classification analysis. All S1B data were smoothed using the Savitzky–Golay smoothing method with five weighting coefficient parameters. The five weighting coefficient parameters provide enough observations to define a smooth backscatter smoothness and effectively filter out high-frequency noise without flattening key phenological transitions. This filter enhances the signal-to-noise ratio by fitting a low-degree polynomial to successive subsets of data, effectively reducing random fluctuations while preserving the temporal pattern of the signal [

44,

45,

46]. It was applied only to the S1B dataset, which had regular 12-day acquisitions from 2019 to 2020, to ensure a clearer representation of rice phenological transitions. In contrast, ALOS2, despite having a nominal 14-day revisit period, did not provide regular acquisitions over the study area, making temporal smoothing less applicable.

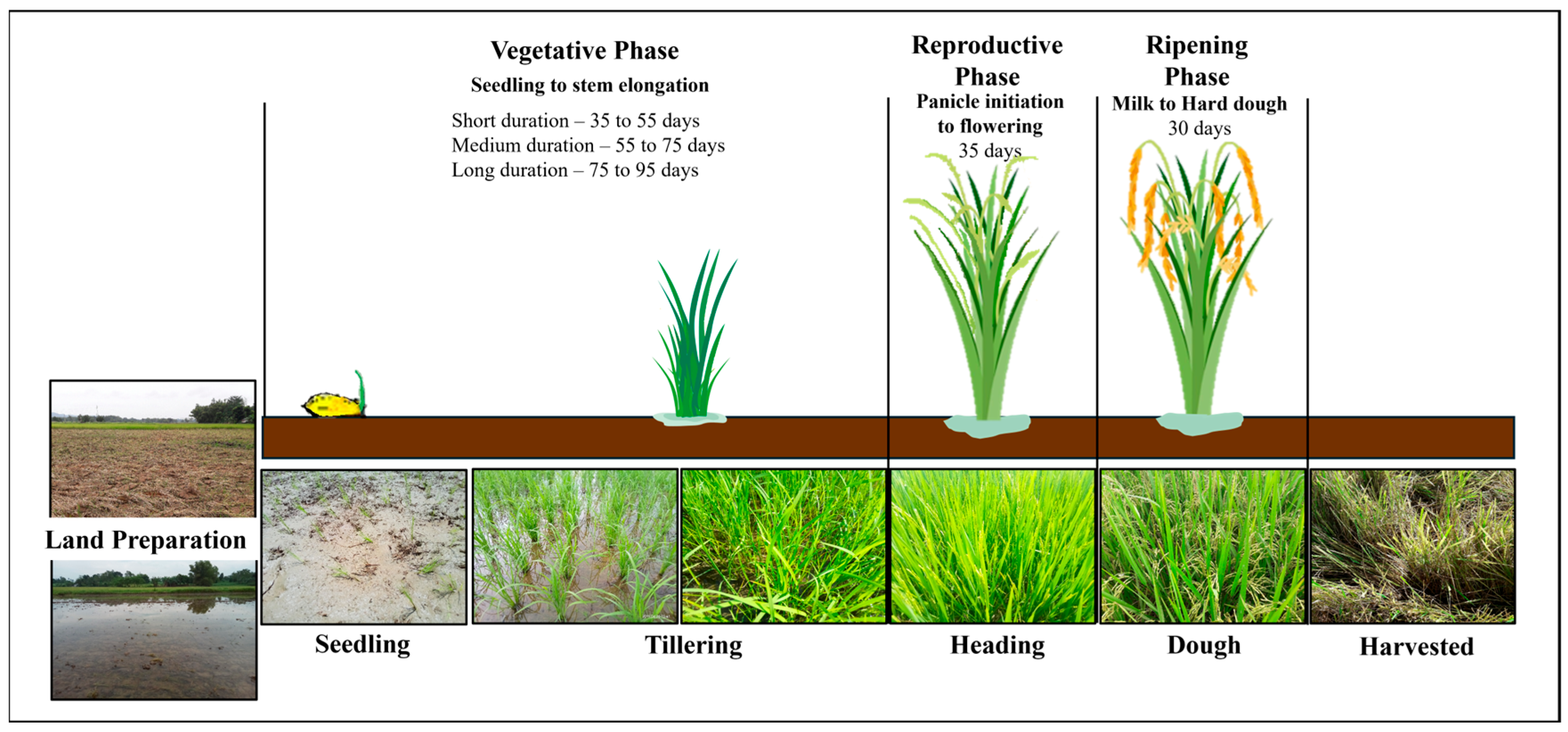

In this study, features of SAR images in six rice growth stages: land preparation, seedling, tillering, reproduction, ripening, and harvesting, were determined and used in the statistical analysis (

Figure 3). According to the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) [

47], rice growth consists of ten stages: germination, seedling, tillering, stem elongation, panicle initiation, booting, heading and flowering, milky grain, soft dough grain, and hard dough grain, which are grouped into three main phases: vegetative (germination to panicle initiation), reproductive (panicle initiation to flowering), and ripening (flowering to hard dough grain). Using the establishment and harvest dates, the corresponding rice stages and phases were identified for each image acquisition. The SAR data values corresponding to each growth stage were then matched with the acquisition dates of S1B and ALOS2 (

Table 2).

Segmented regression was performed on the extracted backscatter values for each sensor (S1B and ALOS2), polarization (VH, VV, HH, and HV), polarimetric parameters (entropy, anisotropy, alpha (α), delta (δ), ratio, rho (ρ), span, surface scattering, and volume scattering), and rice ecosystem (irrigated and favorable rainfed rice). Segmented regression, also known as piecewise linear regression, fits multiple linear segments instead of a single line by identifying breakpoints where the relationship between variables changes [

48]. This method can help detect breakpoints corresponding to changes in rice phenology within each ecosystem. It also provides insights into linear trends and phenology-specific behavior of SAR signals, particularly the variations in backscatter and polarimetric parameter values. These variations are expected to differ between irrigated and favorable rainfed rice ecosystems due to differences in plant and field conditions, particularly in terms of water availability and management. The hypothesis is that segmented regression can effectively capture phenological transitions and reveal differences in scattering behavior between the two ecosystems, reflecting their contrasting hydrological regimes and crop development dynamics. The results of the segmented regression were subsequently used to define the criteria for classification.

The Jeffries–Matusita (J-M) distance was used to evaluate the separability between irrigated and favorable rainfed rice classes. This statistical measure quantifies the degree of dissimilarity or separability between probability distributions, providing an indication of how well the classes can be distinguished based on their feature values. The J-M distance ranges from 0, representing complete overlap or no separability, to 2, indicating perfect class separation. This metric is particularly useful for assessing the discriminative capability of selected features and evaluating the effectiveness of feature selection or dimensionality reduction in improving class separability [

49,

50]. Parameters with R

2 values greater than 0.2 from the segmented regression analysis were included in the J–M distance computation. The results were then used to identify the most relevant backscatter and polarimetric parameters for the classification.

By incorporating these results into the feature selection process, the classification framework emphasized the parameters that were the most sensitive to ecosystem-specific scattering dynamics and rice phenological variations, thereby improving discrimination between irrigated and favorable rainfed rice areas.

2.5. Rice Ecosystems Classification

The irrigated and favorable rainfed rice within the study site were mapped using the results of the segmented regression analysis. Backscatter values in different polarizations and polarimetric parameters with moderate and high coefficients of determination (R2) were selected and used as classification parameters.

Prior to classification, rice area masks from Semesters 1 and 2 were reviewed and analyzed to isolate the rice fields from other land cover and land use types. These masks derived from combined rice areas were detected by the PRiSM project from 2019 to 2023. However, the PRiSM maps only present the aggregated rice areas, without discrimination between irrigated and rainfed ecosystems, as the project has yet to establish a methodology for the delineation.

With the consideration that the study focused only on favorable rainfed rice, which is planted twice per year, we used the rice mask generated during Semester 1. This choice was made because, from November to April, conditions are relatively dry, and only favorable rainfed rice is typically planted during this period. Using this mask helped eliminate non-rice areas and exclude unfavorable rainfed fields, which are cultivated only once per year. Additional masking was performed using the ESA World Cover roads and urban areas dataset to further refine land cover classification.

From the regression analysis, key parameters were identified and used for classification with the Random Forest classifier in ESA SNAP 11.0. Multiple parameter combinations were tested to evaluate the capability of polarimetric features and backscatter values in distinguishing irrigated and favorable rainfed rice. Six classification combinations were performed to compare the suitability of polarimetric parameters and backscatter to discriminate the irrigated and favorable rainfed rice in the province of Iloilo in the Philippines (

Table 3). The parameters with low coefficient of determination (R

2 < 0.20) in segmented regression in either ecosystem were omitted since there was no difference between the rice stages and different ecosystems. For instance, S1B VV polarization was not included in the analysis since the R

2 in both ecosystems was below 0.2. Furthermore, previous studies also mentioned that VV polarization is less sensitive in rice monitoring compared to VH polarization [

23,

43,

51,

52].

Accuracy assessment was performed using 110 irrigated (60) and rainfed rice (50) field sample points. These validation samples were obtained from the PRiSM rice and non-rice validation datasets collected during planting in Semester 2, as well as from verified rainfed rice fields identified in other projects within the study area. All validation points were independent of the monitoring fields used for model training to minimize potential bias in the accuracy assessment.

3. Results

3.1. Ground Data in Monitoring Fields

The selected rice fields located within the irrigated and favorable rainfed areas of the study site served as monitoring fields. Data on farmers’ practices and management activities were collected from these fields during the 2019 Semester 2 and 2020 Semester 1 cropping periods. As summarized in

Table 4 most farmers cultivated early-maturing inbred rice varieties (<110 days) and employed direct seeding as their establishment method. The two ecosystems exhibited different peak establishment periods: for irrigated rice, planting was concentrated in July and November, whereas for favorable rainfed rice, it occurred in June and October during the 2019 wet season (Semester 2) and the 2020 dry season (Semester 1), respectively.

3.2. Backscatter Data in Monitoring Fields

Backscatter values across all polarizations were extracted from both S1B and ALOS2 to examine the relationship between SAR signatures and rice ecosystem characteristics. The temporal backscatter patterns reflected the combined influence of field conditions and phenological development throughout two cropping seasons. Eight subfigures (

Figure 4) showed the time-series backscatter data from S1B (VV and VH polarizations) and ALOS2 (HH and HV polarizations) over the monitoring fields in irrigated and favorable rainfed rice ecosystems. Each line represented different monitoring fields while the black line indicated the mean backscatter in each satellite acquisition. Collectively, these graphs illustrate temporal variations in radar backscatter in relation to rice phenological stages and precipitation patterns. The irrigated rice ecosystem showed a relatively stable and coherent backscatter trend, suggesting uniform crop growth due to irrigation despite field variation. The temporal backscatters in VH polarization (S1B) and HH and HV polarizations (ALOS2) showed the unique backscatter characteristics of rice, and low backscatter values during establishment, with gradual increases from tillering to the reproductive phase and a decline at maturity to the harvesting stages. VV polarization was less sensitive to the phenological changes in the rice fields. Furthermore, based on the results of the segmented regression analysis in the different polarizations, VV polarization showed a low model fit, 0.03 and 0.02 in irrigated and favorable rainfed rice, respectively (

Appendix A.1). Based on these observations, S1B VH polarization, ALOS2 HH and HV polarizations should be used in the classification of irrigated and favorable rainfed rice. Meanwhile, VV polarization was not included in the classification analysis.

Over the two cropping semesters, the irrigated rice ecosystem reflected strong backscatter from S1B and ALOS2. Overall, the two cropping semesters were noticeable in all the backscattering of S1B and ALOS2 dual-polarizations. A noticeable rainfall influenced the backscatter trend and the peaks and drops in each individual field were aligned with the rainfall events. Favorable rainfed rice fields are bunded and can store irrigation water during rainfall. At the onset of the rainy season, land preparation was started on the favorable rainfed rice monitoring fields to start establishment. The low backscatter values or the drops showed that majority of the favorable rainfed rice were in the seedling to early tillering stage based on the field data (

Figure 4). With this, it may suggest that variations in soil moisture contributed to the backscatter response in favorable rice ecosystems, especially during the early tillering stage and when the crop growth was uneven.

3.3. Polarimetric Parameters in Irrigated and Favorable Rainfed Rice Ecosystems

Two polarimetric decompositions were performed on the dual-pol S1B and ALOS2 data: the H-A-α decomposition and the model-based dual-pol decomposition. Values of key polarimetric parameters derived from these decompositions were extracted from the monitoring fields. The temporal trends of selected key parameters for two cropping semesters are shown in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. These parameters were selected based on the segmented regression results, specifically those with R

2 values greater than 0.2 in either rice ecosystem. The black line represents the average of all monitoring fields within each ecosystem, while the blue vertical bars in the graphs indicate daily precipitation (mm/day) throughout the year. The green and brown shaded bars correspond to the establishment and harvesting periods, respectively.

In H-A-α decomposition, there were three key parameters: entropy (H), anisotropy (A), and alpha (α). The temporal trend of the S1B’s entropy, anisotropy and alpha had two peaks and two dips, which indicate two cropping semesters in both irrigated and favorable rainfed rice ecosystems. Based on the ground data from the monitoring fields, for entropy, the dips were after the start of the semester or establishment period, while the peaks were in the ripening or harvesting period. The polarimetric parameters’ (entropy and alpha) trend was similar to the backscatter trend (

Figure 4). The entropy’s values (

Table 5) in irrigated rice ranged from 0.3 to 0.9 (S1B) and 0.2 to 0.8 (ALOS2), while favorable rainfed rice ranged from 0.4 to 0.9 (S1B) and 0.4 to 0.8 (ALOS2). After the establishment period, low entropy shows that the scattering is dominated by one mechanism, either surface or double-bounce scattering. In contrast to the harvesting period, entropy is at moderate-to-high levels, which shows strong randomness, which has multiple scattering contributions. Low entropy values were seen in the flowering stage in irrigated rice while in the land preparation and flowering stages in favorable rainfed rice. This may suggest that during land preparation, rice fields in irrigated rice ecosystems were covered by irrigation water (sample photo can be seen in

Figure 3) where surface scattering dominates, while during reproductive stages, double-bounce scattering may occur from vertical rice stems and irrigation water.

Anisotropy had different trends with entropy. By definition, it compliments entropy and alpha and is usually interpreted alongside entropy [

25]. The values ranged from 0.3 to 0.9 (S1B) and 0.5 to 0.9 (ALOS2) in irrigated rice and 0.4 to 0.8 (S1B) and 0.5 to 0.9 (ALOS2) in favorable rainfed rice (

Table 5). After the establishment period, the anisotropy in both irrigated and favorable rainfed rice had high values, while it had low values in the harvesting period. In S1B, irrigated and favorable rainfed rice exhibited low values at land preparation, reached a peak at the tillering stage, and then declined in the ripening stage. In comparison with ALOS2, rice fields showed an increasing trend in anisotropy at land preparation, reached a peak at the flowering stage, and then declined during the ripening and harvesting stages. Notably, S1B displayed a wider anisotropy range compared to ALOS2, which may reflect differences in the sensors’ penetration capabilities through rice canopy. In ALOS2, the peak at the flowering stage indicates increased surface structural complexity or canopy density at this stage as the L-band can penetrate deeper and interact with stems and irrigation water. In contrast, in S1B, it was observed in the tillering stage as the C-band cannot penetrate deeper the canopy during late stages; thus, interaction is more evident in tillering stages.

On the other hand, alpha followed the temporal trend of entropy on both irrigated and favorable rainfed rice, with low values observed after the establishment period and higher values during the harvesting period. Although alpha in dual-pol data cannot represent the same level of scattering detail as in quad-pol systems, it still captures the dominant scattering mechanisms, albeit with certain ambiguities due to the absence of full polarimetric channels. Therefore, it is best interpreted in conjunction with entropy [

40,

42]. In this case, low entropy and low alpha values were seen in the seedling to early tillering rice stages, which may reflect that surface scattering was dominant. Furthermore, in the reproductive to ripening stages, high entropy with moderate alpha was recorded, which is likely due to volume scattering.

The study also used the model-based dual-pol decomposition to see the quantitative decomposition of physical scattering contributions (

Figure 6). Unlike the H-A-α decomposition, which provides a qualitative understanding of the scattering type and randomness, the model-based approach enables the partitioning of backscatter into distinct scattering powers [

24,

25,

39,

42]. Based on the regression analysis results, which are discussed in the next subsection, only the key parameters with R

2 greater than 0.2 are presented in

Figure 7. The alpha parameter was excluded, as it duplicated the information already provided by the H–A–α decomposition.

Distinct value ranges in span were observed for irrigated and favorable rainfed rice in both ALOS2 and S1B datasets. For ALOS2, irrigated rice exhibited values ranging from 0.007 to 0.24, while in favorable rainfed rice fields, values ranged from 0.02 to 0.19. Lower span values were recorded after the establishment period in both ecosystems, which means low scattering power and indicates smooth surfaces. This is due to the availability of irrigation water during the early tillering stages, especially in the irrigated rice ecosystem. The monitoring fields were established using a direct-seeded method. In this method, the field was maintained as saturated in the establishment period to prevent the seeds from being damaged. Once the plants reach sufficient height and can tolerate standing water, farmers gradually introduce controlled flooding to suppress weeds and maintain soil moisture [

47]. Sample photos from the monitoring fields can be seen in

Figure 3. Furthermore, as rice plants matured, span values increased, reflecting enhanced interactions between standing water and vegetation. For S1B, the span values ranged from 0.08 to 0.22 in irrigated rice fields, while they ranged from 0.02 to 0.19 in favorable rainfed rice fields (

Table 5). The lower span values observed in ALOS2 suggest that it is more sensitive to water conditions in rice fields compared to S1B. Lower span values typically indicate smoother surfaces with minimal signal flooded water–rice plant interactions, reflecting reduced scattering contributions from flooded fields and rice seedlings.

The surface scattering modeled as specular reflection is dominant in smooth water bodies and bare soils and characterized by low alpha and entropy values [

25,

51]. Results showed that surface scattering is in moderate values (−16 to −22) during the establishment and harvesting periods in both rice ecosystems. However, surface scattering values exhibited more variability with fluctuations in favorable rainfed rice. It showed more irregular trends in each monitoring field. In both ecosystems, the values showed that surface scattering increased in accordance with the rainfall events, especially in the early tillering stage. Rainfall events influenced the water availability in the rice field, especially in favorable rainfed rice, thus affecting the scattering. For instance, during the 2019 Semester 2, low backscatter values in VH polarization were observed in the monitoring fields on 21 June 2019 (DOY 172), which coincided with a period of high rainfall preceding the acquisition, between DOY 165 and 172, the area recorded an average daily precipitation of 10.11 mm/day. A similar pattern was observed in the 2020 Semester 1, where low backscatter values on 31 October 2019 (DOY 304) corresponded to a period of intense rainfall, averaging 22.25 mm/day from DOY 298 to 304. Favorable rainfed rice fields, being bunded, are capable of storing irrigation water during rainfall events. During these periods, most favorable rainfed rice fields were in the seedling to early tillering stages based on field observations. Furthermore, the trend in ALOS2 showed sharper peaks or differences in low and high values.

In comparison with surface scattering, volume scattering is associated with intermediate alpha values and higher entropy or high randomness in scattering. This mechanism arises from randomly oriented dipoles within vegetation canopies [

24,

25,

51]. Same as surface scattering, both irrigated and favorable rainfed rice ecosystems show peaks in scattering following rainfall events, especially in favorable rainfed rice fields.

3.4. Segmented Regression, Rice Phenology and Polarimetric Parameters

Segmented regression was performed to model variations in the key parameters of H-A-α decomposition and model-based dual-pol decomposition across rice growth stages. The segmented regression, also known as piecewise linear regression, was used to identify the phenological breakpoints. It captured distinct transitions in the trends associated with key growth stages, such as tillering and flowering. The approach involved estimating one or more breakpoints where the slope of the linear relationship between stage and polarimetric parameters changed significantly. For both irrigated and rainfed rice, the fitted models identified 1–2 breakpoints. These were typically aligned with major phenological transitions, such as the beginning of tillering or flowering. The results of model performance for segmented regression varied by ecosystems.

In summary, the overall performance was low-to-moderate; in particular, rainfed rice ecosystems had low performance (

Table 6). In H-A-α decomposition, the results in S1B showed better model performance than ALOS2. For instance, in S1B, entropy resulted in 0.39 (R

2) in irrigated rice compared to 0.34 in ALOS2. S1B tends to perform better in modeling surface parameters like entropy, anisotropy, and alpha, with higher R

2 values and more consistent sensitivity to phenological stages. ALOS2 showed stronger performance for certain parameters like span and volume scattering, especially in IR, suggesting that it may be more effective for modeling heterogeneity and scattering in irrigated systems.

Irrigated rice (IR) generally exhibits higher R2 and more distinct breakpoints for some parameters, especially in ALOS2, indicating more predictable and stable surface/structural changes. In contrast, favorable rainfed rice tends to have lower R2 values and less consistent breakpoints, reflecting higher variability and less predictable surface dynamics. This is most likely due to the irregular water availability which made the backscatter signals’ greater variability.

Moreover, there were one to two breakpoints aligning with the key phenological stages, the seedling to tillering and reproductive to ripening stages. Tillering is when the rice plant develops its tillers and increases in density, while reproductive stage is when they develop the panicles for production. Furthermore, these stages are usually where farmers flood the rice field, at tillering for weed control and at the reproductive stage to support panicle and grain development.

Based on the results of the regression, we identified key parameters to use for the classification. Polarimetric parameters with an R2 value greater than 0.2 in either irrigated or favorable rainfed rice were included in the analysis. Accordingly, all parameters from the H–A–α decomposition (entropy, alpha, and anisotropy) were selected, along with five parameters from the model-based dual-pol decomposition (span, alpha, ratio, surface scattering, and volume scattering).

The results of the segmented regression of the selected polarimetric parameters are presented in

Figure 7. The graph showed the relationship between polarimetric parameters and each rice stage/phase in two cropping semesters. The breakpoints were shown with the broken lines. Generally, the breakpoints were shown in between the seedling to tillering and reproductive to ripening phases. The following observations were observed in the polarimetric parameters.

Entropy: For S1B, both rice ecosystems exhibited a single breakpoint during the seedling stage. Their temporal trends were also similar, showing low entropy values at the seedling stage that gradually increased until the harvesting stage. The temporal trend follows the backscattering (dB values) pattern in S1B with low values at the seedling stage and increasing until the harvesting stage (

Figure 4). In contrast, ALOS2 results showed distinct temporal trends and breakpoints between irrigated and favorable rainfed rice. The values in ripening were lower than those of other stages, especially in irrigated rice. This is likely due to the presence of flooded water in the reproductive stages. Farmers flood the rice fields to prevent stress that could affect panicle and grain formation.

Alpha: Results showed that both ecosystems exhibited two breakpoints across the SAR sensors, though they occurred at different phenological stages. In S1B, both irrigated and favorable rainfed rice showed a breakpoint during the seedling stage (ψ = 2.1 and 2.35, respectively) with similar temporal trends: slightly higher values during land preparation (21–24°), lower values during the seedling stage (<20°), and a gradual increase toward ripening. In contrast, the breakpoint in ALOS2 showed in the flowering stages was ψ = 4 and 4.35 for irrigated and favorable rainfed rice, respectively. For irrigated rice, the key change occurred around the tillering to flowering stage, where alpha decreased sharply, followed by an increase. For rainfed rice, the change was more gradual, with noticeable shifts during later growth stages.

Anisotropy: It also detected two breakpoints in irrigated and favorable rainfed rice fields, aligning with the major developmental phase in the tillering stage (ψ = 2.71 and 2.62, respectively) and in between the flowering and ripening stages (ψ = 4.43 and 4.95, respectively). Irrigated rice had one breakpoint during the flowering stage (ψ = 4), while favorable rainfed rice had two breakpoints in the seedling and flowering stages (ψ = 2 and 4, respectively).

Surface scattering: The results showed one breakpoint in each ecosystem and sensors in different key rice growth stages. In S1B, breakpoints occurred during the seedling stage for irrigated rice and the tillering stage for favorable rainfed rice. In contrast, ALOS2 exhibited breakpoints in the seedling stage for irrigated rice and the ripening stage for favorable rainfed rice.

Volume scattering: The temporal trends for irrigated and favorable rainfed rice ecosystems in both sensors, S1B and ALOS2, followed the same pattern. Volume scattering in land preparation was slightly higher than the seedling stage and then increased until the ripening and harvest stages. Two breakpoints were seen in both ecosystems in ALOS2 (ψ = 2 and 5), and irrigated rice in S1B (ψ = 2 and 4).

3.5. Separability of Parameters Using Jeffries–Matusita (J-M) Distance

Separability analysis using Jeffries–Matusita (J-M) distance was performed to the selected backscatter polarizations and polarimetric parameters. These variables were selected based on the results of segmented regression, polarizations and polarimetric parameters with >0.2 R

2. As shown in

Figure 8, dashed red and blue lines indicate thresholds for moderate (J-M = 1.0) and excellent (J-M = 1.9) class separability, respectively.

The results revealed distinct differences between the two sensors and different rice ecosystems across the growth stages (

Figure 8). Overall, ALOS2 showed higher separability than Sentinel-1, which reflects the greater sensitivity of the L-band to surface roughness and moisture variations. The seedling stage exhibited the highest separability, particularly in ALOS2 HV polarization (J-M = 1.91, excellent) and volume scattering (J-M = 1.66, moderate), likely due to strong contrasts in water management and surface conditions between irrigated and favorable rainfed rice. Moderate separability was also observed during land preparation, when differences in soil moisture and flooding conditions were noticeable. Irrigated rice fields are typically flooded during land preparation, while favorable rainfed rice fields flood only after rainfall events. In contrast, S1B parameters showed consistently low J-M values (<1.0), indicating poor discrimination, especially in later growth stages where the canopy structures of both ecosystems become similar. Among all parameters, HV backscatter and volume scattering were the most discriminating features, highlighting their potential for distinguishing rice ecosystems during early phenological stages.

3.6. Classification

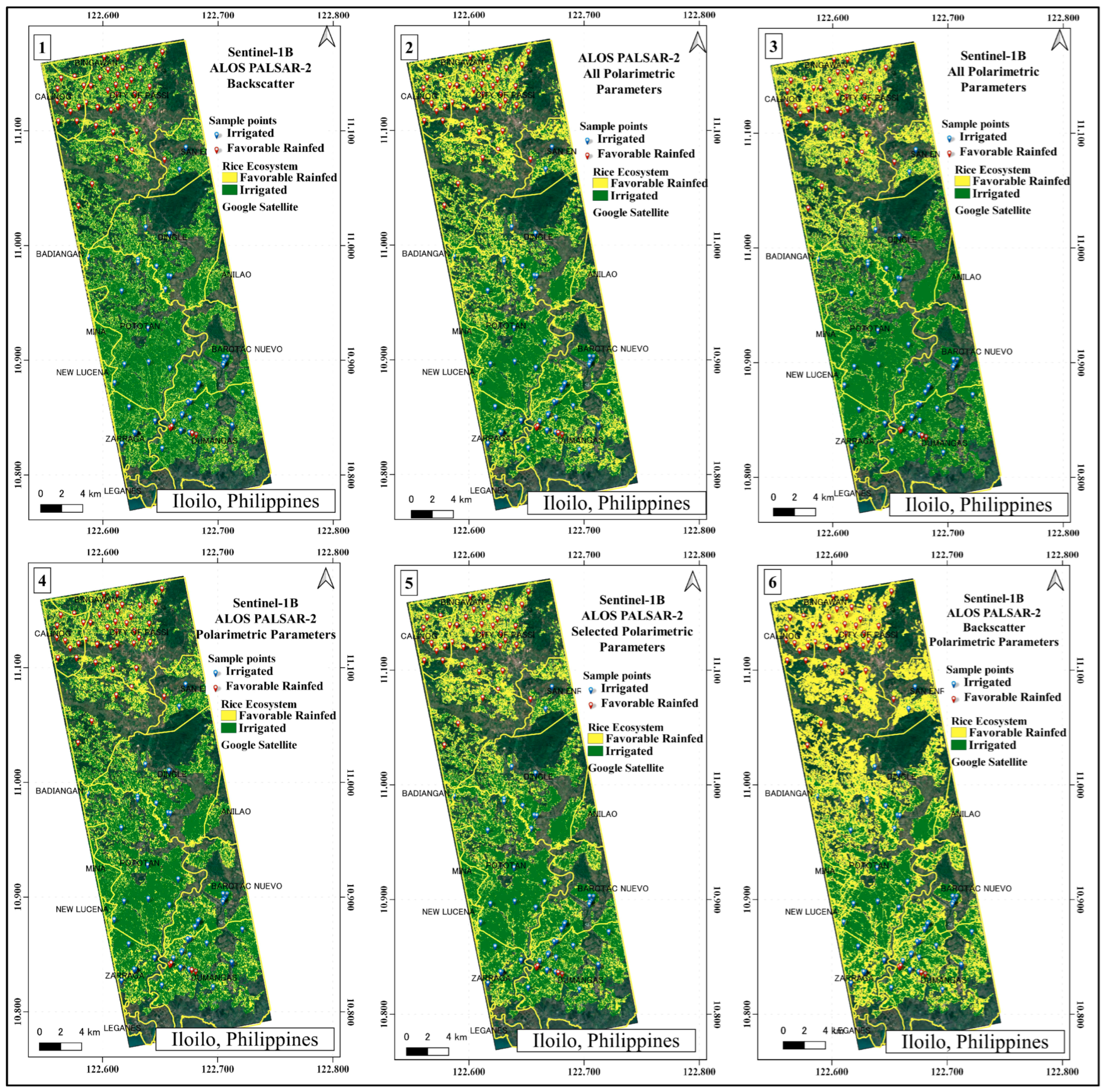

The classification was performed using the Random Forest classifier in ESA SNAP 11.0. Six classification outputs (

Figure 9) were produced from different image combinations, (1) S1B and ALOS2 backscatter, (2) ALOS2 all polarimetric parameters, (3) S1B all polarimetric parameters, (4) S1B and ALOS2 all polarimetric parameters, (5) selected polarimetric parameters of S1B ALOS2, and (6) S1B and ALOS2 polarimetric parameters and backscatter. The descriptions of each combination are listed in

Table 3 and the classification accuracy results are shown in

Table 7.

The results showed that using all the S1B and ALOS2 polarimetric parameters, backscatter from S1B VH polarization, and ALOS2 HH and HV polarizations had the highest accuracy, with 81.81% overall accuracy and 0.6345 kappa coefficient. It had the same overall accuracy as the output from S1B and ALOS2 all polarimetric parameters; however, its kappa coefficient (0.6333 K) is slightly lower than the other one. The lowest accuracy can be seen in the classification using the backscatter of S1B (VH polarization) and ALOS2 (HH and HV polarizations) with 76.67% overall accuracy and 0.3899 Kappa coefficient.

The results indicated that using only polarimetric parameters, input images 2 and 3 detected more rice fields (33.1 ha) than the other input images. Input images 4 (S1B and ALOS2 all polarimetric parameters) and 6 (S1B and ALOS2 polarimetric parameters and backscatter), with the highest accuracy of 81.81%, detected 32.7 ha. However, there was a notable difference between irrigated and favorable rainfed rice. Input image 6 combines all backscatter and polarimetric parameters from both sensors, was able to detect more favorable rainfed rice than the irrigated rice. Although no statistical data were available for the study area at the time of analysis, provincial-level statistics for Iloilo indicate that rainfed rice occupies a larger area than irrigated rice, with 60.3 ha and 46.9 ha, respectively [

11]. As shown in

Figure A2, photos of the validation points are presented to show the field conditions in irrigated and favorable rainfed rice ecosystems.

Moreover, based on the classification results, the use of S1B polarimetric parameters (80.91% accuracy) demonstrated better discrimination between the two ecosystems compared to using backscatter alone (70.00% accuracy). Given the limited spatial coverage of ALOS2 acquisitions, Sentinel-1B serves as a practical and effective alternative for ecosystem classification.

Based on the results, polarimetric parameters can improve the results of the classification for irrigated and favorable rainfed rice in Iloilo, Philippines. It can better discriminate the favorable rainfed rice from irrigated rice. However, the accuracy assessment is based only on the sample points within the area. Further accuracy assessment, such as data from the local government, can increase the credibility of the maps.

4. Discussion

Based on field monitoring data, major rice ecosystems in Iloilo Province, Philippines—irrigated and favorable rainfed—practice synchronous planting (

Table 4). Rice farmers establish paddy fields within one month of regular planting schedules, typically 14 days before or after the designated planting period for their irrigation service area or applicable vicinity. This synchrony is clearly reflected in the backscatter patterns derived from Sentinel-1B (S1B) over the monitored irrigated and favorable rainfed rice fields (

Figure 4). Several studies have reported strong correlations between rice growth stages and S1B backscatter, e.g., [

3,

4,

5,

7,

8], which is why it is commonly used for rice monitoring.

In this study, two polarimetric decomposition techniques were used, H-A-α decomposition and model-based dual-pol decomposition, to extract the key parameters from S1B and ALOS2.

The H-A-α decomposition parameters showed clear seasonal dynamics, with entropy and alpha closely following backscatter trends. Entropy was in the lowest after establishment, which indicates dominant surface scattering in the rice fields and was highest at harvest stages, which reflects multiple scattering. The surface scattering dominance at the stage after establishment or between the seedling and tillering stages was due to the farmers practice in the area. Mostly of the farmers established their field using the direct-seeded method. In this establishment method, the rice field during establishment is only saturated to prevent the seeds from decaying, while in the seedling stage to the tillering stage, it was flooded to prevent weed growth. The irrigation water serves as a smooth surface, and since the seedlings are small and thin, it can create surface scattering. In contrast, in the harvesting stage, the farmers harvest the rice manually, thus leaving rice stubble in the area. Multiple scattering can be detected in this stage because of the interaction of water and the rice stubble (sample photo can be seen in

Figure 4) or ratoon. The results indicate that entropy is correlated to the biophysical characteristics of rice, in which they are similar to the results of [

24,

27]. Dave et al. [

27] found significant correlations between Sentinel-1 decomposition parameters and rice biophysical variables, with R

2 values up to 0.76, while Harfenmeister et al. [

24] observed similar phenological sensitivity in wheat and barley using entropy and alpha (R

2 ≈ 0.64–0.76). Low entropy or values near zero in Cloude–Pottier decomposition (H-A-α decomposition) indicates simple scattering such as surface scattering, while values near one show complex scattering such as volume scattering [

53].

Anisotropy displayed an opposite trend from entropy and alpha; the values were higher after establishment and lower during harvest. In both irrigated and favorable rainfed rice, anisotropy ranged from 0.3 to 0.9 (S1B) and from 0.5 to 0.9 (ALOS2), while alpha ranged from 5° to 38°. Alpha angle values showed a similar temporal trend to entropy; low values after establishment and higher values during harvesting. These alpha angle values indicate that surface scattering dominated shortly after establishment, while volume scattering prevailed during harvest. Low entropy and low alpha values indicate that the dominant scattering is surface scattering, which is usually seen in smooth surfaces like permanent water and flooded fields. Low entropy and high alpha angle values indicated double-bounce scattering in urban areas, while high entropy and mid alpha values can be classified as random vegetation scattering, such as agricultural crops [

24,

25].

The model-based dual-pol decomposition quantified the physical scattering contributions in rice fields, complementing the qualitative insights from H-A-α decomposition. In this study, three key parameters (span, surface scattering, and volume scattering) were analyzed.

The span parameter, which represents the total backscatter from surface, double-bounce, and volume scattering, showed lower values after establishment and increased as rice matured. This can reflect the vegetation–water signal interactions. In coordination with this, irrigated rice exhibited higher and more consistent span values than favorable rainfed rice. This result suggests that irrigated rice has more stable water conditions than the favorable rainfed rice. In terms of the difference between the sensors, ALOS2 generally recorded lower span values than S1B. This shows that ALOS2 has a higher sensitivity to water and smoother surfaces under the rice canopy, particularly during early growth stages.

The surface scattering dominated during the establishment in both irrigated and favorable rainfed rice ecosystems. This was also shown by low entropy and low alpha values in H-A-α decomposition. However, surface scattering exhibited greater variability in favorable rainfed rice, which can be attributed to the influence of rainfall events that affected water availability and surface smoothness. Volume scattering, associated with intermediate alpha values and higher entropy, also peaked following rainfall events, particularly in irrigated fields. These findings align with previous studies that observed similar temporal patterns in scattering mechanisms in agricultural settings. For example, [

24] observed that the polarimetric parameters reflected the main phenological changes in plants and were sensitive to meteorological differences, thus supporting the use of polarimetric decomposition for monitoring agricultural systems, especially for water monitoring.

Based on the segmented regression results, S1B (entropy, anisotropy, and alpha) demonstrated better model performance with higher R2 values for parameters. This indicates more consistent sensitivity to phenological stages in both irrigated and favorable rainfed rice ecosystems. Meanwhile, ALOS2 showed stronger performance for parameters such as span and volume scattering, especially in irrigated rice systems. This shows that ALOS2 is effective in modeling heterogeneity and surface scattering.

In terms of ecosystems, irrigated rice exhibited higher R2 values and more distinct breakpoints than the favorable rainfed rice. This shows that the polarimetric parameters in irrigated rice reflect more predictable surface and structural changes. The less consistent breakpoints in the favorable rainfed rice can be due to the irregular water availability that influenced the backscatter variability.

In general, farmers’ management practices, particularly in terms of water management, greatly affect the trends observed in backscatter and polarimetric parameters. These practices are related to rice stages/phases. For instance, in direct-seeded-method rice fields, the backscatter and polarimetric parameters in early tillering are lower than in the establishment period. This is because farmers typically maintain the fields in a saturated condition during establishment to prevent seed damage and subsequently flood them once the rice plants are capable of withstanding inundation [

47]. Moreover, during the reproductive stage, farmers commonly maintain a water depth of 5 to 10 cm to minimize water stress and promote panicle and grain development. This management practice is reflected in the ALOS2 polarimetric parameters, particularly in the observed low entropy and low alpha values, which indicate more dominant surface scattering from the flooded fields.

Based on the results, using all the S1B and ALOS2 polarimetric parameters, backscatter from S1B VH polarization, and ALOS2 HH and HV polarizations can discriminate irrigated and favorable rainfed rice ecosystems. The polarimetric parameters improved the detection of favorable rainfed rice areas using the Random Forest classifier. Moreover, in the absence of L-band (e.g., ALOS2), C-band SAR can be a good alternative for polSAR classification in rice.

Dual-pol polarimetric parameters can improve the results of the classification for irrigated and favorable rainfed rice in Iloilo, Philippines. The study is limited to the available ground data. Further accuracy assessment should be performed with the help of the local government in the province (e.g., actual land area with each municipality).

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated the use of dual-polarization Sentinel-1B and ALOS PALSAR-2 in monitoring irrigated and favorable rainfed rice ecosystems through polarimetric decomposition and backscatter. Although the backscatter signatures of irrigated and favorable rainfed rice ecosystems are quite similar, which complicates their differentiation, incorporating polarimetric Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) parameters enables more effective distinction between these two ecosystems for monitoring purposes.

The H–A–α decomposition revealed clear seasonal dynamics, with entropy and alpha closely tracking phenological stages, while anisotropy exhibited complementary behavior. The model-based dual-pol decomposition further quantified the relative contributions of surface and volume scattering. The polarimetric parameters emphasized the influence of rainfall and water management practices on scattering variability, particularly in favorable rainfed rice. S1B dual-pol polarimetric parameters captured phenological dynamics through entropy, anisotropy, and alpha parameters, whereas ALOS2 polarimetric parameters were more sensitive to water conditions, as reflected in span and volume scattering. Across different ecosystems, irrigated rice exhibited more stable and predictable scattering patterns than favorable rainfed rice. Overall, the combined use of S1B and ALOS2 dual-pol polarimetric parameters enhances the discrimination of irrigated and favorable rainfed rice. It offers valuable insights for rice monitoring in cloud-prone regions in combination with backscatter. In addition, in the absence of fully polarimetric L-band SAR, the use of dual-pol C-band SAR can improve the classification accuracy of favorable rice and irrigated rice.

Future studies should integrate more extensive ground observations and local stakeholder support to further improve accuracy and operational applications.