Highlights

What are the main findings?

- A satellite retrieval model incorporating bio-optical and physical properties was developed to estimate vertical profiles of oceanic PON.

- The model-retrieved PON profiles exhibited good performance, outperforming those derived from the -based regression approach.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- This study establishes the first satellite-based framework for retrieving the vertical distribution of oceanic PON, providing a practical approach for large-scale monitoring of marine nitrogen.

- It strengthens our capacity to investigate marine nitrogen dynamics and their role in global biogeochemical cycles.

Abstract

Accurate satellite retrieval of oceanic particulate organic nitrogen (PON) vertical profile is essential for understanding global biogeochemical processes; however, no dedicated retrieval models currently exist. This study developed a novel PON profile retrieval model using the eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) algorithm, based on a comprehensive global dataset that includes in situ PON measurements, MODIS-Aqua bio-optical data, and 3D reanalysis physical data. The XGBoost-retrieved PON profiles were compared with those derived from Copernicus particulate backscattering coefficient () profiles and were further used to estimate the euphotic-zone PON stocks through an optimally performing regression model. The results showed that the proposed model significantly outperformed models constructed without physical inputs, achieving of 0.83, RMSE of 1.49 and MAPE of 18.07%. Compared to the -based profiles, the XGBoost-retrieved profiles exhibited higher accuracy. The model also provided reliable estimates of euphotic-zone PON stocks, with of 0.76, RMSE of 200.31 mg and MAPE of 15.09%. These findings demonstrate the potential of the proposed retrieval model for investigating oceanic nitrogen dynamics and biogeochemical cycles.

1. Introduction

Particulate organic nitrogen (PON), operationally defined as organic nitrogen retained on filters with nominal pore sizes ranging from 0.2 to 0.7 µm, encompasses a broad spectrum of biological and detrital particles, including large viruses, bacteria, phytoplankton, zooplankton, and biogenic debris [1,2,3]. PON concentrations exhibit pronounced spatial and temporal variability across the global ocean, primarily driven by phytoplankton production and degradation, vertical mixing, and horizontal advection associated with dynamic oceanographic processes [4]. As a key component of the marine nitrogen cycle, PON interacts with dissolved nitrogen pools, contributing to phenomena such as eutrophication and ocean acidification [5]. PON commonly co-occurs with particulate organic carbon (POC) as part of marine organic matter [6]. Given that nitrogen frequently acts as a limiting nutrient in marine environments, PON plays a critical role in regulating primary production and modulating the biological carbon pump [7].

Accordingly, characterizing the spatiotemporal distribution and variability of oceanic PON is essential for understanding nitrogen dynamics, evaluating ecosystem function, and predicting biogeochemical responses to environmental change [8]. Traditionally, oceanic PON concentrations are determined through in situ sampling followed by laboratory analysis [9], using methods such as carbon-hydrogen-nitrogen elemental analysis [10] or chemical oxidation techniques [11]. However, the high cost and low spatiotemporal resolution of ship-based observations hinder a comprehensive assessment of PON variability across the global ocean [12,13]. The growing availability of satellite ocean color data provides a powerful tool for synoptic, long-term monitoring of global oceanic biogeochemical variables at high spatiotemporal resolution. It has been widely used to retrieve global surface chlorophyll-a (Chl-a) and POC concentrations from satellite-derived water-leaving radiance and reflectance [14,15,16,17,18].

Recently, there has been growing interest in extending satellite-based retrieval methods to PON. For example, Fumenia, Petrenko [19] identified a strong relationship between PON concentrations and the backscattering coefficient of particulate matter () in the oligotrophic waters of the western tropical South Pacific, demonstrating the feasibility of estimating PON from bio-optical parameters. Wang, Liu [20] developed polynomial regression models using various bio-optical properties and spectral band indices, showing the potential of satellite-based PON estimation. Zhang, Liu [21] developed Gaussian Process Regression PON retrieval models for five popular ocean color satellite missions. By incorporating a broader set of input features, their approach achieved improved model performance compared to simple polynomial regression models. Additionally, Fumenia, Loisel [3] investigated the variability of relationships between PON and inherent optical properties (IOPs), such as and phytoplankton absorption coefficient (), using in situ near-surface data from diverse optical regimes, including open-ocean pelagic waters, Arctic seas, and European coastal zones.

Although significant progress has been made, existing studies have largely focused on the retrieval of surface-layer PON concentrations. However, photosynthetic activity and associated nitrogen cycling extend throughout the euphotic zone [1]. This indicates that surface PON concentrations alone are insufficient to capture subsurface processes. These processes include nutrient remineralization, particle sinking, and depth-dependent nutrient availability, all of which strongly influence particulate nitrogen cycling, export fluxes, and marine ecosystem functioning [8,22]. Furthermore, large compilations of particulate organic matter from global cruises have demonstrated substantial spatial and depth-dependent variability in particle organic carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus ratios [12,23], underscoring the significance of observing the vertical distribution of PON. There is thus a pressing need for reliable, satellite-based models capable of retrieving the vertical distribution of oceanic PON concentrations.

The primary objective of this study is to develop an accurate and applicable satellite-based model for retrieving global oceanic PON profiles. To achieve this, a comprehensive matchup dataset was constructed, which consists of in situ PON profile measurements, ocean color remote sensing products from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS), and 3D physical reanalysis data. Using these multi-source inputs, a PON profile retrieval model was developed based on the eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) method. The model enables the estimation of both the vertical distribution of PON concentrations and the euphotic-zone PON stocks across the global ocean, thereby improving the monitoring of PON dynamics and advancing our understanding of nitrogen cycling under climate change and anthropogenic pressures.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. In Situ Oceanic PON Data

The global in situ PON profiles used in this study were obtained from two publicly accessible data repositories: the SeaWiFS Bio-optical Archive and Storage System (SeaBASS, https://seabass.gsfc.nasa.gov/) and the Dryad Digital Repository (https://datadryad.org/) provided by Martiny, Vrugt [23]. The combined dataset comprises 5909 vertical profiles and 36,969 individual PON measurements. A profile is defined as measurements collected at two or more depths at the same geographic location.

The SeaBASS dataset aggregates measurements from numerous field campaigns conducted worldwide and is sorted and provided by the NASA Ocean Biology Processing Group [24]. The Dryad dataset includes PON observations from 70 globally distributed research cruises and time-series programs, providing broad spatial coverage across diverse oceanic regimes.

2.2. Ocean Color Satellite Data

MODIS-Aqua Level-3 Daily Standard Mapped Image products (4 km spatial resolution) were used as the primary ocean color inputs for PON profile retrieval. These data were obtained from the NASA Ocean Biology Processing Group (http://oceancolor.gsfc.nasa.gov/). The products include apparent optical properties (AOPs), such as remote sensing reflectance (Rrs) and the diffuse attenuation coefficient of downwelling irradiance at 490 nm (Kd(490)); IOPs, including total absorption coefficient (a), , absorption coefficient of detritus and gelbstoff (), total backscattering coefficient (bb), bbp and spectral slope of particulate backscattering (); and biological properties, including POC and Chl-a concentrations.

2.3. Ocean Physics Data

To characterize vertical variations in physical conditions, the monthly Global Ocean Physics Reanalysis dataset (GLORYS12V1, 2001–2022, https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00021) was used, which was obtained from the Copernicus Marine Data Store. This high-resolution (1/12°, ~8 km) dataset provides physical variables including temperature, salinity, and mixed layer depth (), generated by the Copernicus Marine Environment Monitoring Service using the real-time global forecasting system.

GLORYS12V1 assimilates a broad suite of observations, including along-track altimeter data (sea level anomaly), satellite sea surface temperature, sea ice concentration, and in situ temperature and salinity profiles, through a reduced-order Kalman filter to provide a dynamically consistent reconstruction of ocean state. The dataset covers depths from 0.49 m to 5727.92 m. For this study, the 25 vertical layers within the upper 1062.44 m were used. The vertical resolution varies with depth, ranging from 1.05 m to 3.10 m in the upper 21.6 m, 3.61 m to 36.35 m between 25.21 m and 222.48 m, and 52.09 m to 160.10 m between 266.04 m and 1062.44 m.

2.4. Matchups of In Situ, Satellite and Reanalysis Data

The global in situ PON dataset was first matched with MODIS-Aqua ocean color products. For each in situ measurement, the nearest satellite pixel was identified, and a 3 × 3 pixel grid centered on that location was extracted within ±1 day temporal window. A matchup was retained when more than 50% of the pixels contained valid observations; the mean value of all valid pixels was then used as the satellite counterpart [14]. To ensure meaningful vertical information, additional filters were applied: (1) profiles consisting of only a single sampling depth were removed, and (2) only profiles for which at least 70% of the samples fell within the euphotic zone were retained.

The PON–satellite matchups were subsequently matched with oceanic physical properties from the GLORYS12V1 reanalysis. Before matching, GLORYS12V1 fields were spatially resampled to 4 km MODIS-Aqua Level-3 grid. The matching procedure depended on the variable type: for 2D variables (e.g., ), the same 3 × 3 spatial window as above were applied. For 3D variables (e.g., Temperature and Salinity), the depth of each in situ measurement was used to extract values from the nearest vertical level of GLORYS12V1. Temporal matching followed a monthly window to ensure consistency.

2.5. Feature Selection

Satellite-derived bio-optical variables primarily represent surface PON concentrations, limiting their ability to capture PON variability throughout the euphotic zone. To overcome this, physical oceanographic parameters were also included in model development. In total, four categories of candidate predictors were considered: (1) AOPs and their derivatives, consisting of , band indices including blue-to-green band ratio (BG), color index (CI), maximum band ratio (MBR), normalized difference nitrogen index (NDNI), and (490), (2) IOPs, including a, , , , , and , (3) biological properties, including Chl-a and POC concentrations, and (4) physical properties, including temperature, salinity, and the depth of the euphotic layer ().

As the primary zone of photosynthetic activity, plays a critical role in shaping the vertical distribution of PON concentrations. In this study, was estimated using satellite-derived IOPs following Lee, Weidemann [25]. To avoid uncertainties associated with imperfect atmospheric correction, 412 nm AOPs and IOPs were excluded [26].

A recursive feature elimination (RFE) strategy coupled with XGBoost was used to identify an initial subset of bio-optical predictors. Features with a correlation coefficient > 0.7 with PON were ranked by their importance in the XGBoost model. XGBoost PON models were then constructed repeatedly by adding incremental features in order of decreasing importance. For each model, the RMSE of 10-fold cross-validation was calculated. The optimal number of features was determined using the minimal Akaike’s Information Criterion with small-sample correction (AICc, Equation (1)) [27]:

where n is the sample number, k is the number of candidate features, and MSE is the root mean square error of the 10-fold cross-validation of XGBoost models.

Second, to reduce redundancy among physical variables and to improve model efficiency and generalizability, principal component analysis (PCA) was applied. The procedure included: (1) From the GLORYS12V1 monthly dataset (2000–2020), 10,000 valid samples were randomly selected for each month; (2) For each sample, physical parameters across 25 vertical layers within the 0–155 m were extracted; (3) PCA was then applied to derive the variance-covariance matrix and reduce the 25-dimensional space to a smaller set of principle components (typically 3–5), preserving ≥ 99.9% cumulative variance. The resulting principal components of temperature and salinity, together with and , were added as physical predictors.

2.6. Model Development, Validation and Interpretability

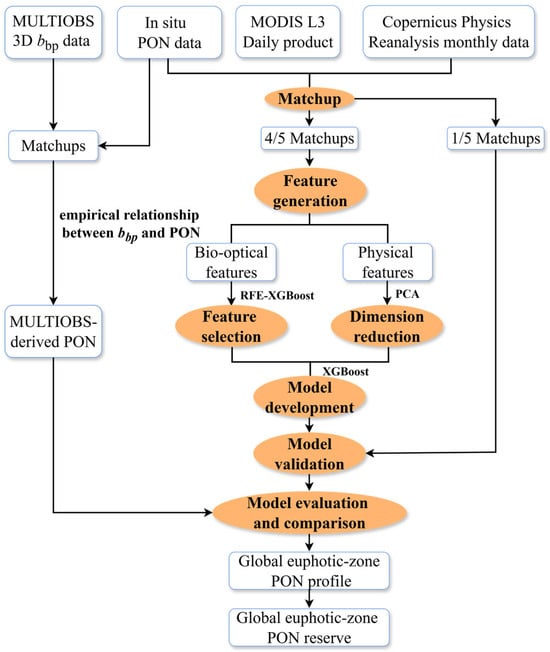

The matchup dataset was randomly divided into calibration (80%) and validation (20%) subsets. The model was trained based on the XGBoost method using both the REF-XGBoost selected bio-optical features and the physical predictors. The latter includes PCA-reduced temperature and salinity, satellite-derived Zeu, and the reanalysis-based Zm. The validation dataset was used for independent performance assessment of the model. The overall framework for developing the PON profile retrieval model is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overall framework of global oceanic PON profile model development, evaluation and application.

XGBoost, a tree-based ensemble learning algorithm, has shown strong capability in retrieving oceanic biogeochemical properties from satellite observations [14,28]. It employs a boosting framework in which a sequence of weak learners is combined into a single strong learner through additive optimization. During training, XGBoost minimizes a predefined objective function through gradient descent while incorporating regularization terms to reduce overfitting and improve generalizability. Training proceeds until a stopping criterion is met, and final predictions are produced as a weighted sum of outputs from all individual learners.

To interpret the contributions of each feature in the XGBoost-based PON profile model, the SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) method [29] was employed. Based on cooperative game theory and Shapley values, SHAP quantifies both the magnitude and direction of the influence derived from each input feature on model predictions. Specifically, for each individual prediction, the model output is decomposed into contributions (Shapley values) assigned to every input feature.

2.7. Independent Model Validation Based on MULTIOBS Dataset

To further assess the accuracy of the XGBoost PON profile retrieval model, from the global ocean 3D biogeochemical MULTIOBS dataset (MULTIOBS_GLO_BIO_BGC_3D_REP_015_010; https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00046) were used to generate the profiles of PON concentration. Distributed by the Copernicus Marine Service, MULTIOBS dataset provides weekly global fields of Chl-a, , and POC from 7 January 1998 to 28 December 2022 at a horizontal resolution of 0.25° 0.25°. The dataset includes 36 vertical layers from the surface to 1000 m, with depth resolution varying from 5 m in the upper 70 m to 100 m at 600–1000 m [30].

Model validation was performed by constructing matchups between from MULTIOBS and in situ PON measurements. The spatiotemporal matching followed three steps: (1) extracting a 3 × 3 pixel window around each in situ station, (2) selecting the closest available weekly MULTIOBS record to ensure temporal alignment, and (3) assigning values from the nearest vertical level to ensure depth consistency.

The PON profiles retrieved by the XGBoost model were then compared with those derived from using the empirical relationship between PON concentration and at 555 nm ((555)) proposed by Fumenia, Loisel [3] for oceanic surface waters:

Because MULTIOBS provides at 700 nm ((700)), a wavelength conversion to (555) was applied using the following equation:

where is the spectral slope of (λ), taken from the corresponding MODIS-Aqua Level-3 product.

3. Results

3.1. Matchups of In Situ PON, Satellite Products and Reanalysis Data

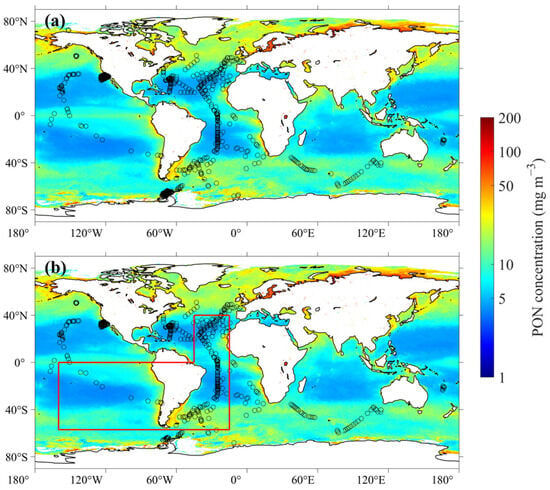

A total of 10,978 valid matchups were obtained between in situ PON data and MODIS-Aqua satellite products after removing outliers. These matchups correspond to 1974 vertical profiles of PON concentrations, of which 1579 profiles were used for model calibration and 395 profiles for model validation. The geographical distributions of the matched dataset are shown in Figure 2. The in situ sampling sites were globally distributed, with a large proportion of them concentrated in the Atlantic Ocean and further extending into the Southern Ocean. Additional sampling sites were located in the coastal waters of the United States, the subtropical gyres of the Pacific Ocean adjacent to the Americas, and southern areas of the Indian Ocean.

Figure 2.

Geographical distributions of matchups of (a) in situ PON measurements, MODIS-Aqua data, and physics reanalysis dataset, and (b) in situ PON measurements and MULTIOBS products. The background map illustrates the global oceanic distribution of surface PON concentrations retrieved by the XGBoost retrieval model. The red frame delineates two regions: the region within 0–57°S and 15–160°W, and the region within 0–40°N and 15–45°W.

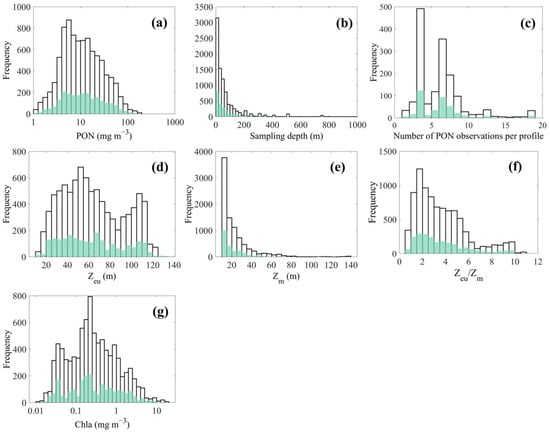

Figure 3a presents the distribution histogram of in situ PON concentrations. The data exhibit a unimodal pattern with a peak occurring below 10 . The full range of PON concentrations spans from 1 to 196.4 , with an average of 17.42 ± 20.11 . This range aligns with values typically observed in global in situ PON datasets [31]. Notably, 72.65% of the data points recorded concentrations below 20 , reflecting the predominance of pelagic waters in the dataset. As shown in Figure 3b, 91.61% of PON concentrations were measured within the depth range of 200 m. Moreover, the majority of individual PON profiles contained fewer than 10 observations (Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

The distribution histogram of (a) matched in situ PON concentrations, (b) PON sampling depths, (c) number of PON observations for each profile, (d) satellite-derived , (e) reanalysis-based , (f) / ratio, and (g) satellite-derived Chl-a concentrations. Black boxes represent the modeling dataset, and green boxes indicate the validation dataset.

Hydrological variables associated with the matched PON profiles, specifically the and , were also examined. ranged from 10.88 to 132.95 m, with an average of 63.70 ± 28.35 m, while ranged from 10.16 to 136.33 m, with an average of 22.29 ± 15.93 m. As shown in Figure 3d, exhibited a bimodal distribution, with peaks centered around 50 m and 105 m, respectively. In contrast, displayed a unimodal distribution that decreased monotonically from a peak near 10 m (Figure 3e). Using the stratification classification criteria described in [1], it was found that 96.32% of the observations had a / ratio greater than 1 (Figure 3f), indicating that most sampled waters were stratified. An analysis of trophic status based on surface Chl-a concentrations (Figure 3g) further revealed that 26.13% of the observations corresponded to oligotrophic conditions (Chl-a ≤ 0.1 mg m−3), 55.61% to mesotrophic conditions (0.1 < Chl-a ≤ 1.0 mg m−3), and 18.25% to eutrophic conditions (Chl-a > 1.0 mg m−3), following the classification scheme also referenced in [1].

3.2. XGBoost PON Profile Retrieval Model Development

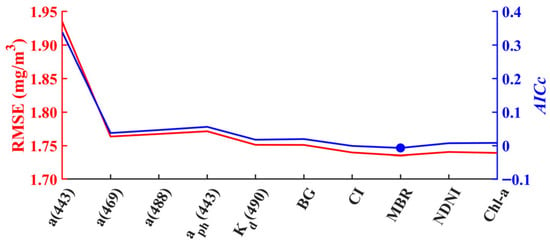

To construct the PON profile retrieval model, eight out of ten features were selected through the RFE-XGBoost method based on their lowest value of Akaike’s Information Criterion with small-sample correction (AICc) and relatively small RMSE. Specifically, the bio-optical features selected including a(443), a(469), a(488), (443), (490), BG, CI and MBR (Figure 4). In addition, temperature and salinity data across 25 vertical layers were dimensionally reduced by PCA to four principal components, with their cumulative variance contributions of 99.95% and 99.93%, respectively.

Figure 4.

Variations in the RMSE and AICc with the number of elected features in XGBoost PON modeling for MODIS-Aqua. The features are ranked based on their importance.

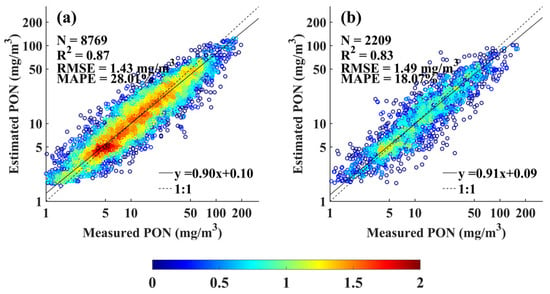

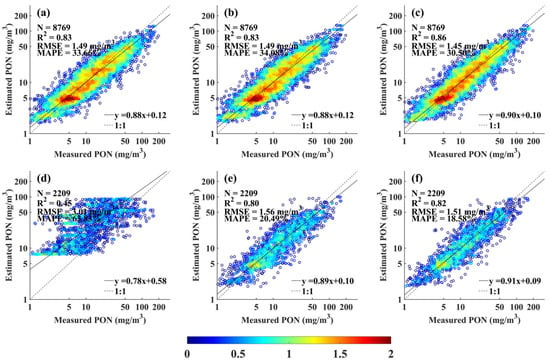

Therefore, the XGBoost PON profile retrieval model was developed based on the following 19 bio-optical and physical features: a(443), a(469), a(488), (443), (490), BG, CI and MBR, Zeu, Zm, PON sampling depth, and four principal components each for salinity and temperature derived through PCA. As shown in Figure 5a, the model exhibited strong performance on the calibration dataset, with of 0.87, RMSE of 1.43 mg m−3, and MAPE of 28.01%. The regression slope was 0.90, indicating good agreement between the observed and estimated PON concentrations, with a slight tendency toward a slight overestimation at lower concentrations and an underestimation at higher concentrations. The model also performed well on the independent validation dataset, achieving of 0.83, RMSE of 1.49 mg m−3, and MAPE of 18.07% (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Comparison of XGBoost-estimated and measured PON concentrations for (a) model calibration, (b) model validation.

3.3. Assessment of the XGBoost PON Model Based on MULTIOBS Products

A total of 10,615 matchups between in situ PON measurements and MULTIOBS products were initially obtained for subsequent validation of the XGBoost-based PON profile retrieval model (Figure 2b). To ensure the effectiveness of Equation (1), model validation using MULTIOBS data was restricted to matched samples located within the region (0–57°S, 15–160°W, and 0–40°N, 15–45°W) outlined by the red box in Figure 2b. This area is primarily distributed across the open waters of the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans and is consistent with the spatial domain examined by Fumenia, Loisel [3]. Within this region, in situ PON concentrations ranged from 1.02 to 57.85 with an average of 7.47 ± 7.62 . Notably, 92.69% of the measurements were below 20, indicating a predominance of pelagic water conditions.

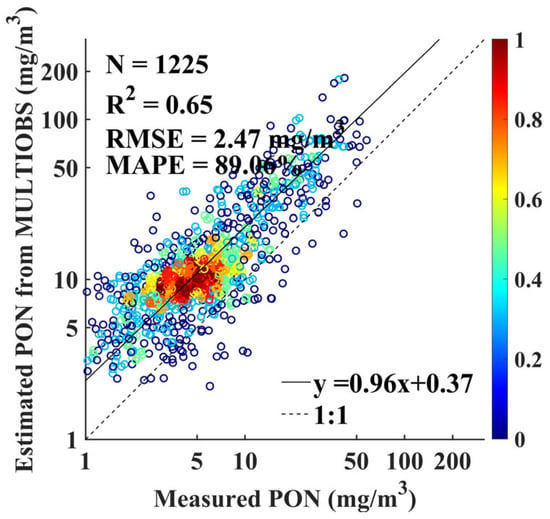

As shown in Figure 6, PON concentrations estimated using the MULTIOBS exhibited a clear tendency toward overestimation relative to in situ measurements, with of 0.65, RMSE of 2.47 mg m−3, MAPE of 89.06%, and slope of 0.96. The MULTIOBS-derived PON profiles based on the empirical relationship exhibit significantly lower accuracy compared to the XGBoost PON profile retrieval model (Figure 5). Moreover, the XGBoost model demonstrated higher accuracy across a wider concentration range and in more diverse oceanographic conditions.

Figure 6.

Comparison of measured and MULTIOBS-estimated PON concentrations.

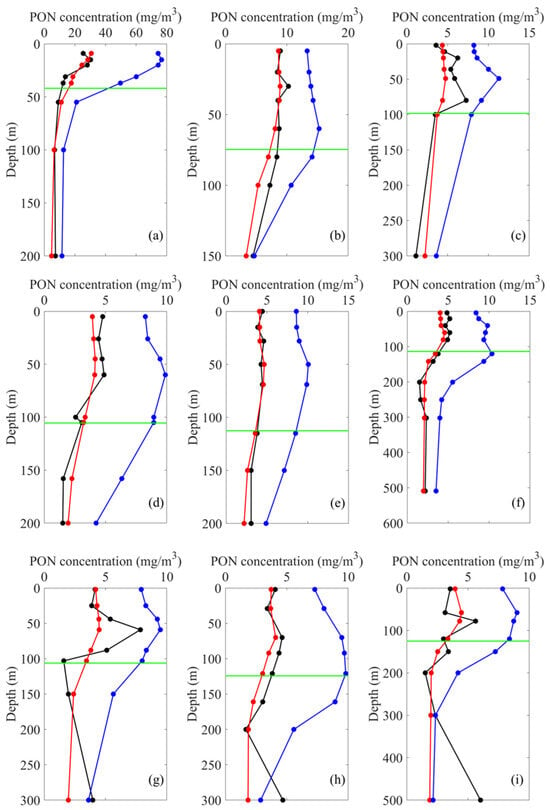

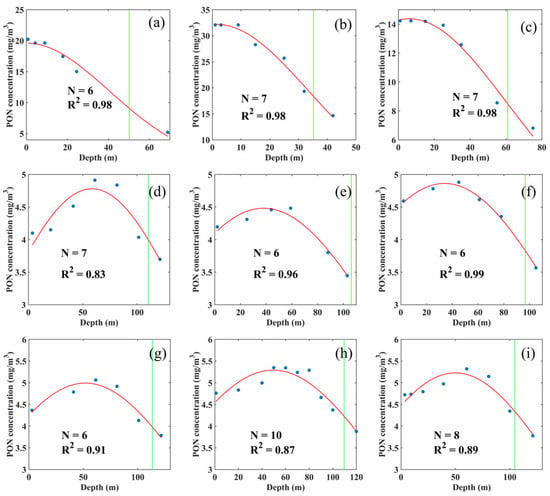

To further assess the performance of the XGboost PON profile retrieval model, vertical PON concentration profiles estimated by both XGBoost and MULTIOBS were compared against in situ observations. As shown in Figure 7, the profiles estimated by the XGBoost model were significantly closer to the in situ observations compared to the MULTIOBS-derived profiles, particularly within the euphotic zone. Below the euphotic zone, the discrepancies among the three PON profiles diminished. This is likely because the MULTIOBS method relies on the empirical relationship between PON and (555) for oceanic surface waters, which tends to constrain its performance in deeper layers. However, although the XGBoost model generally outperformed the MULTIOBS-based estimates, the MULTIOBS approach was better at capturing vertical variability patterns in certain cases, especially in reproducing subsurface PON maxima, as illustrated in Figure 7g.

Figure 7.

Comparison of PON concentration profiles from in situ measurements (black lines), XGBoost estimates (red lines), and MULTIOBS estimates (blue lines). (a–f) correspond to the calibration dataset at the following locations: (a) 46.31°S, 54.44°W; (b) 9.00°S, 136.85°W; (c) 33.50°N, 28.75°W; (d) 31.30°N, 27.70°W; (e) 31.43°N, 33.74°W; (f) 19.66°N, 44.75°W. (g–i) correspond to the validation dataset at the following locations: (g) 31.55°N, 31.33°W; (h) 18.52°S, 25.10°W; (i) 22.96°S, 24.98°W. The green horizontal line represents the base of the euphotic zone.

3.4. Euphotic-Zone PON Stocks Estimation Using the XGBoost Model

The performance of the XGBoost PON profile retrieval model in retrieving oceanic PON reserves within the euphotic layer was further evaluated. To evaluate the effectiveness of the XGBoost model in reproducing the vertical distribution patterns of PON, both in situ and XGBoost-estimated PON profiles that contained more than five valid data points from the surface down to 20 m below the base of the euphotic zone were selected. In total, 174 profiles were drawn from the calibration dataset and 42 from the validation dataset. Four types of regression models, including polynomial, Gaussian, exponential and power-law, were applied to fit the vertical profiles.

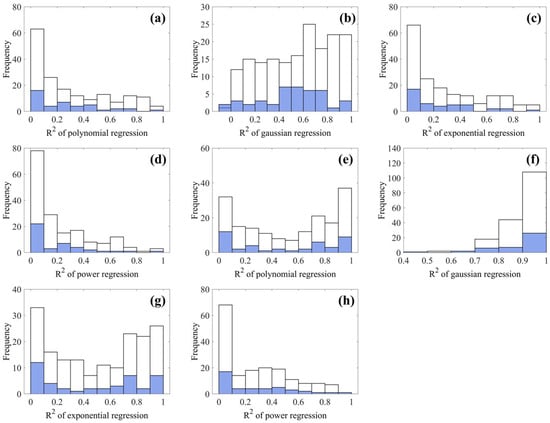

Figure 8 presents the distribution histograms of corresponding , with panels (a–d) representing in situ profiles and panels (e–h) showing XGBoost-estimated profiles. Among the regression models, Gaussian regression consistently provided the highest values of for both in situ and XGBoost-estimated datasets. In contrast, the polynomial, exponential, and power-law models exhibited predominantly lower values of , mostly concentrated below 0.5 (Figure 8a,c,d,h). Although a subset of XGBoost-estimated profiles displayed moderately higher values of under polynomial and exponential models (Figure 8e,g), a large part of remained below 0.4 and performed significantly worse than Gaussian fits (Figure 8f).

Figure 8.

Distribution histograms of values for polynomial, Gaussian, exponential, and power regressions applied to: (a–d) in situ PON profiles and (e–h) XGBoost-estimated profiles. White and blue denotes calibration and validation datasets, respectively.

Although many vertical PON profiles displayed a Gaussian-like structure with a subsurface maximum, this pattern was not universal. Some profiles (Figure 9a–c) showed a monotonic decrease with depth, with only minor variability in the upper ~10 m. Even in profiles exhibiting a Gaussian-like peak (Figure 9d–i), PON concentrations were generally low, with vertical differences typically less than 2 . Nevertheless, these deviations did not compromise the effectiveness of Gaussian regression in estimating PON stock within the euphotic layer.

Figure 9.

Gaussian regression of XGBoost-estimated PON vertical profiles from the surface to 20 m below the base of the euphotic zone at the following locations: (a) 67.51°S, 70.59°W; (b) 53.35°S, 60.23°W; (c) 10.58°N, 64.68°W; (d) 27.54°N, 57.26°W; (e) 31.55°N, 31.33°W; (f) 35.69°N, 25.81°W; (g) 22.67°N, 65.51°W; (h) 30.68°N, 64.71°W; (i) 31.66°N, 64.12°W from the validation dataset. The blue solid dots represent the XGBoost-estimated PON concentrations, the red curves show the Gaussian regression fits to the XGBoost-estimated PON profiles, and the green vertical lines represent the base of the euphotic zone.

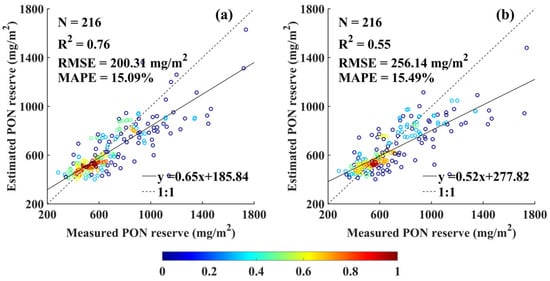

The fitted Gaussian profiles were integrated over the depth of Zeu to estimate euphotic-zone PON stocks from both in situ and XGBoost-derived profiles. The resulting estimates showed good agreement, with of 0.76, RMSE of 200.31 mg and MAPE of 15.09% (Figure 10a). The XGBoost-based estimates tended to slightly overestimate at lower stock ranges and underestimate at higher stock ranges, with the latter discrepancy being more prominent.

Figure 10.

Comparison of euphotic-layer PON stocks estimated from XGBoost-derived profiles: (a) Gaussian regression and (b) individually optimized regression for each profile.

To explore whether regression model selection impacts estimation accuracy, an alternative approach was tested where the best-fit regression model (i.e., the one with the highest ) was selected individually for each profile. Under this flexible model selection strategy, the agreement between in situ and XGBoost-estimated stocks was weaker, with of 0.55, RMSE of 256.14 , and MAPE of 15.49% (Figure 10b). These findings suggest that a consistent Gaussian fitting approach could produce more accurate PON stocks compared to the profile-specific model selection for the matchups in this study.

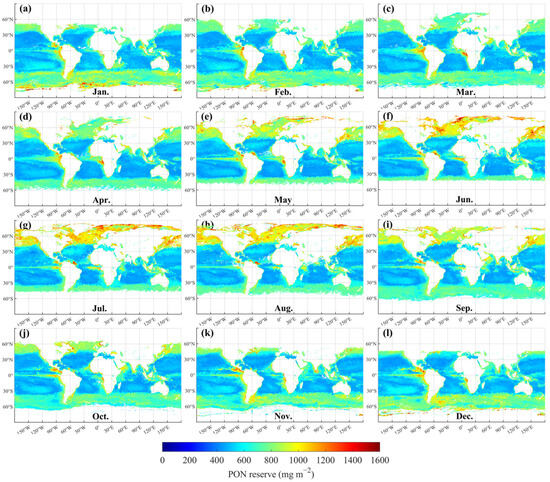

However, at the global scale, selecting the best-fit regression model for each location is a more appropriate approach for estimating PON stock. As shown in Figure 11, the global distributions of monthly PON stocks within the euphotic zone from January to December 2020 were derived by integrating PON profiles using optimal regression selected from linear, Gaussian, exponential and power-law models. PON stocks were relatively high in the subpolar gyres of the northern hemisphere and the Antarctic Circumpolar Current in the southern hemisphere. In contrast, consistently low PON stocks were observed in the subtropical gyres of both hemispheres. Elevated PON stocks also appeared in equatorial waters, forming a narrow band of high concentrations, although this pattern was intermittently disrupted in the equatorial Indian Ocean. The global distribution of PON stocks further reveals significant seasonal variability. For example, in the North Atlantic and North Pacific between 30°N and 60°N, PON stocks increased steadily from March to August before declining in the subsequent months (Figure 11c–h).

Figure 11.

Global monthly PON stocks within the euphotic zone in 2020: (a) January; (b) February; (c) March; (d) April; (e) May; (f) June; (g) July; (h) August; (i) September; (j) October; (k) November; (l) December.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Contribution of Physical Properties in PON Profile Modeling

This study demonstrates that vertical profiles of PON concentration in the global ocean can be effectively retrieved using a combination of bio-optical and physical features as model inputs. The inclusion of physical features was motivated by their fundamental role in shaping phytoplankton primary production. As phytoplankton community structure and primary productivity are largely regulated by variations in water column stratification and the bioavailability of key macronutrients (e.g., nitrogen, phosphorus, and silicate), both of which are modulated by ocean warming, acidification, alterations in circulation patterns, and sea level rise [32,33].

Although individual correlations between the principal components of temperature and salinity and PON concentrations were weak (R < 0.2 in most cases), numerous studies have demonstrated that the combined effects of temperature and salinity influence the spatiotemporal variability of ocean productivity by modulating stratification, nutrient fluxes, and phytoplankton community dynamics. For example, temperature can directly influence phytoplankton growth rates [34] and indirectly affect nutrient supply [35]. Salinity can alter phytoplankton physiology and serve as a proxy for trophic conditions, especially in estuarine and coastal environments where freshwater inflow leads to low salinity and high nutrient concentrations [36]. Furthermore, Zeu and Zm were selected as input features, because their combination could be used as a robust indicator of the stratification condition [1].

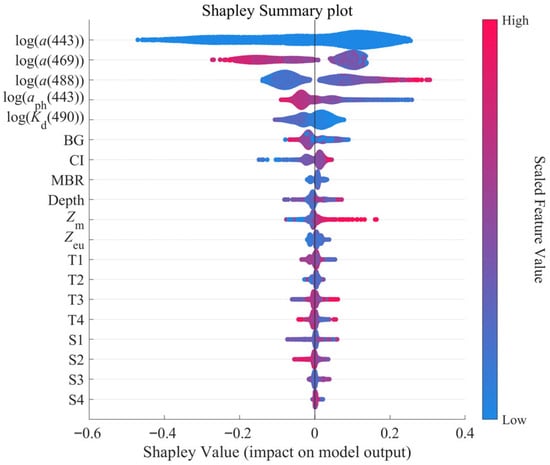

Due to the generally weak correlations between individual physical parameters and PON concentrations, the physical parameters were added to the model manually after identifying an optimal set of bio-optical features through RFE-XGBoost. To quantify the contribution of each input feature to the output of the XGBoost PON profile model, the distribution of Shapley values for all features derived from SHAP analysis is shown in Figure 12. It is obvious that all bio-optical features, including a(443), a(469), a(488), (443), (490), BG, CI and MBR, play a more important role in retrieving PON profiles. Their relative contributions are generally consistent with the feature importance rankings obtained through the RFE-XGBoost feature selection process (Figure 4).

Figure 12.

SHAP analysis of the XGBoost PON profile model using the calibration dataset.

In contrast, physical features contributed less to the model output. Principal components derived from temperature and salinity via PCA ranked lowest in contribution, with their Shapley values fluctuating around zero regardless of feature magnitude. This indicates that the effects of temperature and salinity on PON concentrations are nonlinear and complex, making it difficult to classify their influence as uniformly positive or negative. Among all physical features, Zm showed a predominantly positive influence, as most of its high values (red points) corresponded to positive SHAP values. In comparison, the effects of depth and Zeu were less clear, which may reflect the complex and indirect role of hydrodynamic conditions in regulating biological processes and PON distribution.

However, the relatively small contribution of physical features to the model output does not imply that they are irrelevant. To demonstrate the importance of incorporating physical properties, a bio-optical model was developed only using bio-optical properties and the depth of PON measurements. As shown in Figure 13a, the model demonstrated satisfactory performance on the calibration dataset, with of 0.83, RMSE of 1.49 mg m−3, MAPE of 33.66%, and slope of 0.88. But its performance on the validation dataset was significantly degraded, with of 0.45, RMSE of 3.01 mg m−3, MAPE of 63.83%, and slope of 0.78 (Figure 13d).

Figure 13.

Comparison between XGBoost-estimated and measured PON concentrations for the calibration (a–c) and validation (d–f) datasets. (a,d) show results from the model without physical properties; (b,e) from the model using RFE-XGBoost–selected bio-optical and physical properties; and (c,f) from the model using single-depth salinity and temperature.

The necessity of manually incorporating physical properties was also assessed. The RFE-XGBoost feature selection was performed using both bio-optical and physical variables. The resulting model, which included only one physical feature (Zeu), achieved reasonable performance (R2= 0.83/0.80, RMSE = 1.49/1.56 mg m−3, MAPE = 34.08%/20.49% for calibration/validation; Figure 13b,e). Zeu was selected due to its strong link to euphotic light penetration. However, this model slightly underperformed compared to the final model that forcibly integrated physical features (Figure 5b), underscoring the value of incorporating physical variables through a complementary, knowledge-informed approach. Moreover, the advantage of constructing the model using PCA-reduced temperature and salinity profiles was also confirmed, as it achieved higher accuracy than the model developed using temperature and salinity at a single depth (Figure 13c,f).

4.2. Underestimation of the Observed Subsurface Maximal PON Concentration

The XGBoost PON profile model exhibited one limitation. As shown in Figure 7, the XGBoost model tends to underestimate the observed subsurface maximum of PON concentrations. This likely contributes to the overall underestimation of PON stocks within the euphotic zone, as indicated by the discrepancies between model-estimated and measured values (Figure 10). A primary factor constraining the model in capturing this subsurface maximum is the limitation of the in situ PON profiles used for model development. As in most cases, the subsurface PON maximum is not well included due to the coarse vertical resolution and limited number of sampling depths (Figure 3), especially when compared to the higher-resolution profiles observed by Biogeochemical Argo (BGC-Argo) floats [30].

The subsurface PON maximum is typically located within the well-documented Deep Chlorophyll Maximum (DCM) layer, which emerges from the complex interactions among light availability, nutrient gradients, and water column stratification. Among these, stratification plays a critical role by creating a two-layer vertical structure: a nutrient-depleted surface layer and a light-limited deeper layer. The interface between these layers often provides optimal conditions for phytoplankton growth, promoting the formation and persistence of the DCM [37]. DCM is widely focused on oceanic biogeochemical studies, especially in oligotrophic water. Therefore, improving the model performance in retrieving the subsurface PON maximum is crucial for a better understanding of oceanic biogeochemical cycles and should be a key focus of future work.

4.3. Future Perspectives on Satellite Retrieval of PON Profiles

To further improve the retrieval accuracy of satellite-derived oceanic PON vertical profiles, several efforts could be considered. First, expanding the availability of in situ PON profile data is essential for improving model performance. Currently, such measurements are relatively concentrated in the Atlantic and eastern Pacific Oceans, whereas data coverage remains sparse in other regions, particularly the South Pacific and Indian Oceans. Future observational campaigns should prioritize these under-sampled regions.

Second, owing to its significantly high temporal and vertical resolutions, as well as its broad spatial coverage across the world, data observed by BGC-Argo has been widely used to retrieve the 3D distributions of key biogeochemical parameters, such as Chl-a concentration, POC concentration and primary Productivity across the global ocean, demonstrating strong performance [30,38,39]. On this basis, future studies could investigate the feasibility of using BGC-Argo observations to retrieve the 3D structure of PON concentrations.

Third, the current model architecture estimates PON concentrations independently at each depth level, potentially limiting its performance in capturing the entire vertical structure. In contrast, several models developed for POC profiles employ a pattern-based approach, where the vertical distribution was retrieved simultaneously based on the vertical structure judged from surface ocean color signal and other physical and biological properties [1,40]. A similar strategy could be tested for PON profile retrieval, whereby the model first classifies the vertical distribution type and subsequently estimates concentrations at specific depths.

Fourth, incorporating additional nutrient parameters—such as nitrate, phosphate, silicate, and dissolved oxygen concentrations—has the potential to improve retrieval accuracy. These variables are important indicators of the nutrient status and biogeochemical dynamics of the water column. Finally, atmospheric correction remains a critical source of uncertainty in satellite remote sensing, especially over optically complex coastal waters. Errors in atmospheric correction can propagate through to the bio-optical inputs of the model, thereby compromising the accuracy of PON profile estimates. The near-infrared iterative atmospheric correction method implemented in SeaDAS has been shown to perform suboptimally in coastal environments [41,42], underscoring the need for more robust atmospheric correction algorithms tailored to coastal and turbid waters in future applications.

5. Conclusions

This study combined in situ PON measurements, MODIS-Aqua satellite-derived ocean color products and a 3D reanalysis physics dataset to realize the satellite retrieval of vertical PON distributions. An XGBoost algorithm was developed, using a set of bio-optical and physical features, including a(443), a(469), a(488), (443), (490), BG, CI, MBR, Zeu and , as well as the principal components of temperature and salinity profiles. The resulting XGBoost model accurately retrieved global oceanic vertical distributions of PON concentrations within the euphotic zone, outperforming those empirically estimated from the MULTIOBS 3D product. Moreover, monthly euphotic-zone PON stocks in 2020 were retrieved by integrating the retrieved PON profiles based on regression, which reveals distinct seasonal variations across the global ocean. Overall, this study presents a robust and scalable framework for the satellite retrieval of oceanic PON profiles. It demonstrates the potential of ocean color remote sensing to monitor both the vertical structure and total stock of PON within the euphotic zone, thereby contributing to an improved understanding of oceanic biogeochemical processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z. and H.L.; methodology, Y.Z.; software, Y.Z. and C.L.; validation, Y.Z.; formal analysis, Y.Z. and H.L.; resources, H.L., P.Z. and G.X.; data curation, Y.Z., Y.W. and M.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, H.L. and P.Z.; visualization, Y.Z.; supervision, H.L. and P.Z.; project administration, H.L.; funding acquisition, H.L. and P.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported by the Guangdong Major Project of Basic and Applied Basic Research (No. 2023B0303000017), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42371337 and No. 42471387), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (No. 2024A1515011388) the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (No. JCYJ20230808105709020 and JCYJ20240813142621029), the Scientific Foundation for Youth Scholars of Shenzhen University (No. 806-000034080293), and the China Postdoctoral Science 388 Foundation (2024M762121).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to NASA OBPG for providing the ocean color satellite products, to Copernicus Marine Service for sharing the reanalysis physical dataset and the reproduced bio-optical products, and to researchers for sharing the in situ measurements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Duforêt-Gaurier, L.; Loisel, H.; Dessailly, D.; Nordkvist, K.; Alvain, S. Estimates of particulate organic carbon over the euphotic depth from in situ measurements. Application to satellite data over the global ocean. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2010, 57, 351–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharbush, J.J.; Close, H.G.; Van Mooy, B.A.S.; Arnosti, C.; Smittenberg, R.H.; Le Moigne, F.A.C.; Mollenhauer, G.; Scholz-Böttcher, B.; Obreht, I.; Koch, B.P.; et al. Particulate Organic Carbon Deconstructed: Molecular and Chemical Composition of Particulate Organic Carbon in the Ocean. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumenia, A.; Loisel, H.; Reynolds, R.A.; Stramski, D. Relationships between the concentration of particulate organic nitrogen and the inherent optical properties of seawater in oceanic surface waters. Biogeosciences 2025, 22, 2461–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, T.; Deutsch, C. Oceanic nitrogen reservoir regulated by plankton diversity and ocean circulation. Nature 2012, 489, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fennel, K.; Wilkin, J.; Levin, J.; Moisan, J.; O’Reilly, J.; Haidvogel, D. Nitrogen cycling in the Middle Atlantic Bight: Results from a three-dimensional model and implications for the North Atlantic nitrogen budget. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2006, 20, GB3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagnes, D.J.S.; Berges, J.A.; Harrison, P.J.; Taylor, F.J.R. Estimating carbon, nitrogen, protein, and chlorophyll a from volume in marine phytoplankton. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1994, 39, 1044–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, N.; Galloway, J.N. An Earth-system perspective of the global nitrogen cycle. Nature 2008, 451, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, C.M.; Mills, M.M.; Arrigo, K.R.; Berman-Frank, I.; Bopp, L.; Boyd, P.W.; Galbraith, E.D.; Geider, R.J.; Guieu, C.; Jaccard, S.L.; et al. Processes and patterns of oceanic nutrient limitation. Nat. Geosci. 2013, 6, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm-Hansen, O. Determination of particulate organic nitrogen. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1968, 13, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, J.H. Improved analysis for “particulate” organic carbon and nitrogen from seawater1. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1974, 19, 984–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujo-Pay, M.; Raimbault, P. improvement of the wet-oxidation procedure for simultaneous determination of particulate organic nitrogen and phosphorus collected on filters. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1994, 105, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiny, A.C.; Pham, C.T.A.; Primeau, F.W.; Vrugt, J.A.; Moore, J.K.; Levin, S.A.; Lomas, M.W. Strong latitudinal patterns in the elemental ratios of marine plankton and organic matter. Nat. Geosci. 2013, 6, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stramska, M. Particulate organic carbon in the global ocean derived from SeaWiFS ocean color. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2009, 56, 1459–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, Q.; Bai, Y.; Yang, C.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Q.; Hu, S.; Shi, T.; Liao, X.; Wu, G. Improving satellite retrieval of oceanic particulate organic carbon concentrations using machine learning methods. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 256, 112316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, I.D.; Stramski, D.; Reynolds, R.A.; Robinson, D.H. Performance assessment and validation of ocean color sensor-specific algorithms for estimating the concentration of particulate organic carbon in oceanic surface waters from satellite observations. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 286, 113417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, C.; Zhou, X.; Hu, C.; Lee, Z.; Li, L.; Stramski, D. A Color-Index-Based Empirical Algorithm for Determining Particulate Organic Carbon Concentration in the Ocean From Satellite Observations. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2018, 123, 7407–7419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stramski, D.; Joshi, I.; Reynolds, R.A. Ocean color algorithms to estimate the concentration of particulate organic carbon in surface waters of the global ocean in support of a long-term data record from multiple satellite missions. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 269, 112776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Bai, Y.; He, X.; Tao, B.; Pan, D.; Chen, C.-T.A.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Y.; Gong, C. Satellite estimation of particulate organic carbon flux from Changjiang River to the estuary. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 223, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumenia, A.; Petrenko, A.; Loisel, H.; Djaoudi, K.; Deverneil, A.; Moutin, T. Optical proxy for particulate organic nitrogen from BGC-Argo floats. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 21391–21406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Wu, G. Satellite retrieval of oceanic particulate organic nitrogen concentration. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 943867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, F.; Zhu, P.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, G.; Li, Q. Toward Applicable Retrieval Models of Oceanic Particulate Organic Nitrogen Concentrations for Multiple Ocean Color Satellite Missions. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quay, P. Impact of the Elemental Composition of Exported Organic Matter on the Observed Dissolved Nutrient and Trace Element Distributions in the Upper Layer of the Ocean. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2021, 35, e2020GB006902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiny, A.C.; A Vrugt, J.; Lomas, M.W. Concentrations and ratios of particulate organic carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus in the global ocean. Sci. Data 2014, 1, 140048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werdell, P.J.; Bailey, S.W. An improved in-situ bio-optical data set for ocean color algorithm development and satellite data product validation. Remote Sens. Environ. 2005, 98, 122–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Z.; Weidemann, A.; Kindle, J.; Arnone, R.; Carder, K.L.; Davis, C. Euphotic zone depth: Its derivation and implication to ocean-color remote sensing. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2007, 112, C03009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Yu, X.; Lee, Z.; Wang, M.; Jiang, L. Improving low-quality satellite remote sensing reflectance at blue bands over coastal and inland waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 250, 112029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, E.; Speekenbrink, M.; Krause, A. A tutorial on Gaussian process regression: Modelling, exploring, and exploiting functions. J. Math. Psychol. 2018, 85, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Liu, H.; Zhao, W.; Shi, T.; Hu, Z.; Li, Q.; Wu, G. Comparison of Machine Learning Techniques in Inferring Phytoplankton Size Classes. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. In Proceedings of the 31st Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sauzède, R.; Claustre, H.; Uitz, J.; Jamet, C.; Dall’Olmo, G.; D’Ortenzio, F.; Gentili, B.; Poteau, A.; Schmechtig, C. A neural network-based method for merging ocean color and Argo data to extend surface bio-optical properties to depth: Retrieval of the particulate backscattering coefficient. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2016, 121, 2552–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiny, A.C.; Vrugt, J.A.; Primeau, F.W.; Lomas, M.W. Regional variation in the particulate organic carbon to nitrogen ratio in the surface ocean. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2013, 27, 723–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henson, S.A.; Cael, B.B.; Allen, S.R.; Dutkiewicz, S. Future phytoplankton diversity in a changing climate. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shen, F.; Sun, X.; Tan, K. Marine big data-driven ensemble learning for estimating global phytoplankton group composition over two decades (1997–2020). Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 294, 113596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Urrutia, Á.; Morán, X.A.G. Temperature affects the size-structure of phytoplankton communities in the ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2015, 60, 733–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marañón, E.; Cermeño, P.; Latasa, M.; Tadonléké, R.D. Resource supply alone explains the variability of marine phytoplankton size structure. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2015, 60, 1848–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Pan, D.; Cai, W.; He, X.; Wang, D.; Tao, B.; Zhu, Q. Remote sensing of salinity from satellite-derived CDOM in the Changjiang River dominated East China Sea. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2013, 118, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornec, M.; Claustre, H.; Mignot, A.; Guidi, L.; Lacour, L.; Poteau, A.; D’ORtenzio, F.; Gentili, B.; Schmechtig, C. Deep Chlorophyll Maxima in the Global Ocean: Occurrences, Drivers and Characteristics. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2021, 35, e2020GB006759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; He, X.; Bai, Y.; Wang, G.; Li, T.; Wang, D.; Gong, F.; Zhu, Q. Satellite-Estimation of the Global Ocean Primary Productivity via BGC-Argo Measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2025, 130, e2024JC021163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Chen, X.; Bai, Y.; He, X.; Li, T.; Pan, D. Reconstruction of 3-D Ocean Chlorophyll a Structure in the Northern Indian Ocean Using Satellite and BGC-Argo Data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 61, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Sun, Z.; Shen, M.; Tian, L.; Yu, S.; Jiang, X.; Duan, H. Three-dimensional observations of particulate organic carbon in shallow eutrophic lakes from space. Water Res. 2022, 229, 119519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, G. Ocean Colour Atmospheric Correction for Optically Complex Waters under High Solar Zenith Angles: Facilitating Frequent Diurnal Monitoring and Management. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhou, Q.; Li, Q.; Hu, S.; Shi, T.; Wu, G. Determining switching threshold for NIR-SWIR combined atmospheric correction algorithm of ocean color remote sensing. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2019, 153, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).