Response of Vegetation to Extreme Climate in the Yellow River Basin: Spatiotemporal Patterns, Lag Effects, and Scenario Differences

Highlights

- Under three CMIP6 SSP scenarios, the leaf area index (LAI) shows an increasing trend across the Yellow River Basin, with significant scenario-dependent spatial variations in both distribution patterns and responses to extreme climate indices.

- Annual total wet-day precipitation, frost days, growing season length, summer days, and ice days are identified as key extreme climate indices driving LAI variability.

- The relatively long time-lag and cumulative effects of climate extremes in arid/semiarid regions highlight vegetation vulnerability to prolonged climatic stress.

- These findings provide a scientific basis for formulating region-specific ecological conservation and climate adaptation strategies in ecologically vulnerable watersheds.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Multi-Source Data Collection

2.2.2. Consistency of LAI Data from MODIS and GLASS

2.2.3. Spatiotemporal Trends of LAI

2.2.4. PLSR

2.2.5. Time Lag Effect and Cumulative Effect on the Future Vegetation LAI

3. Results

3.1. Consistency of the LAI Data from MODIS and GLASS

3.2. Spatiotemporal Patterns of LAI Trends Under Historical and Future Climate Scenarios

3.3. Key Extreme Climate Drivers of LAI Dynamics

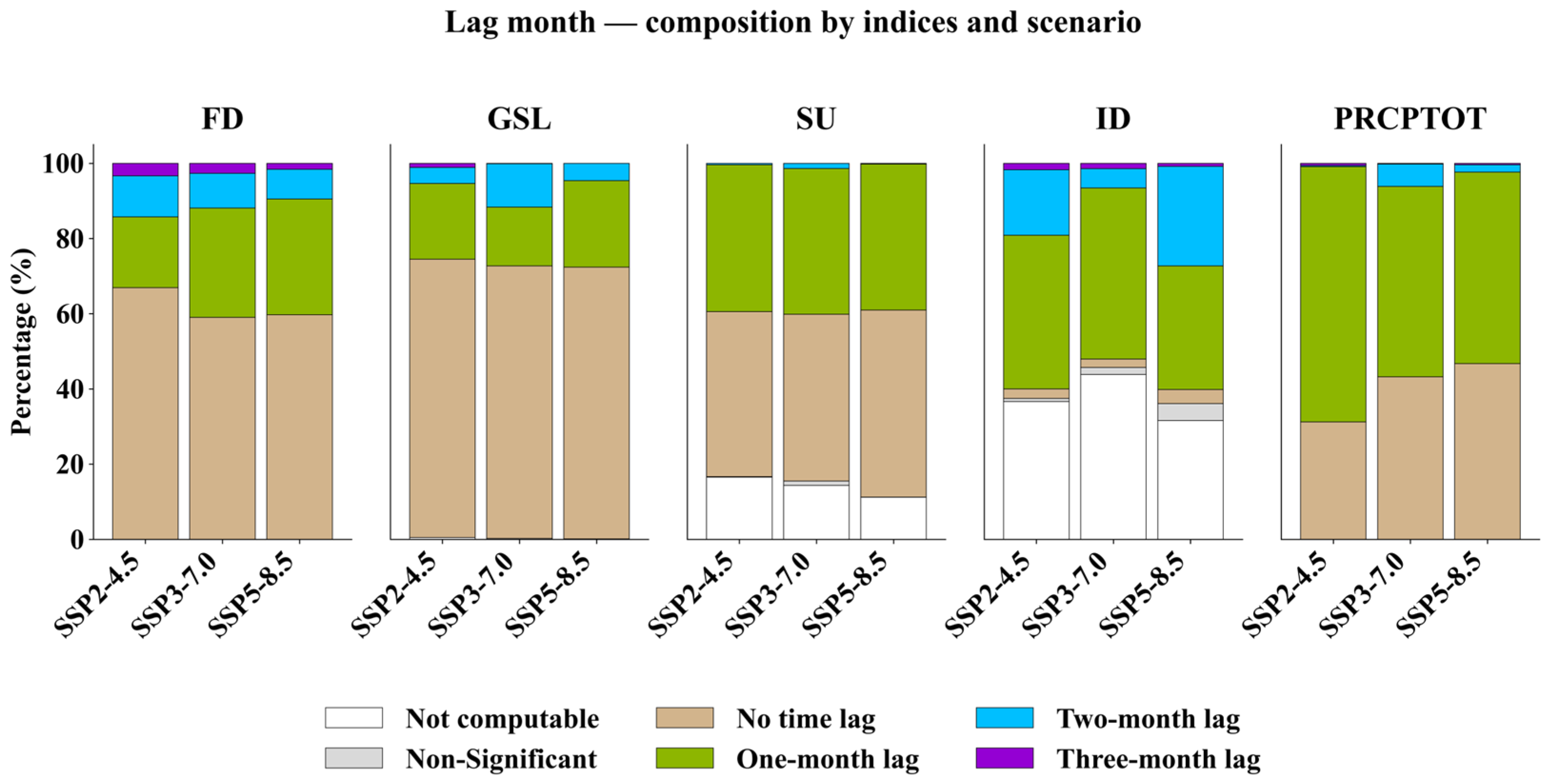

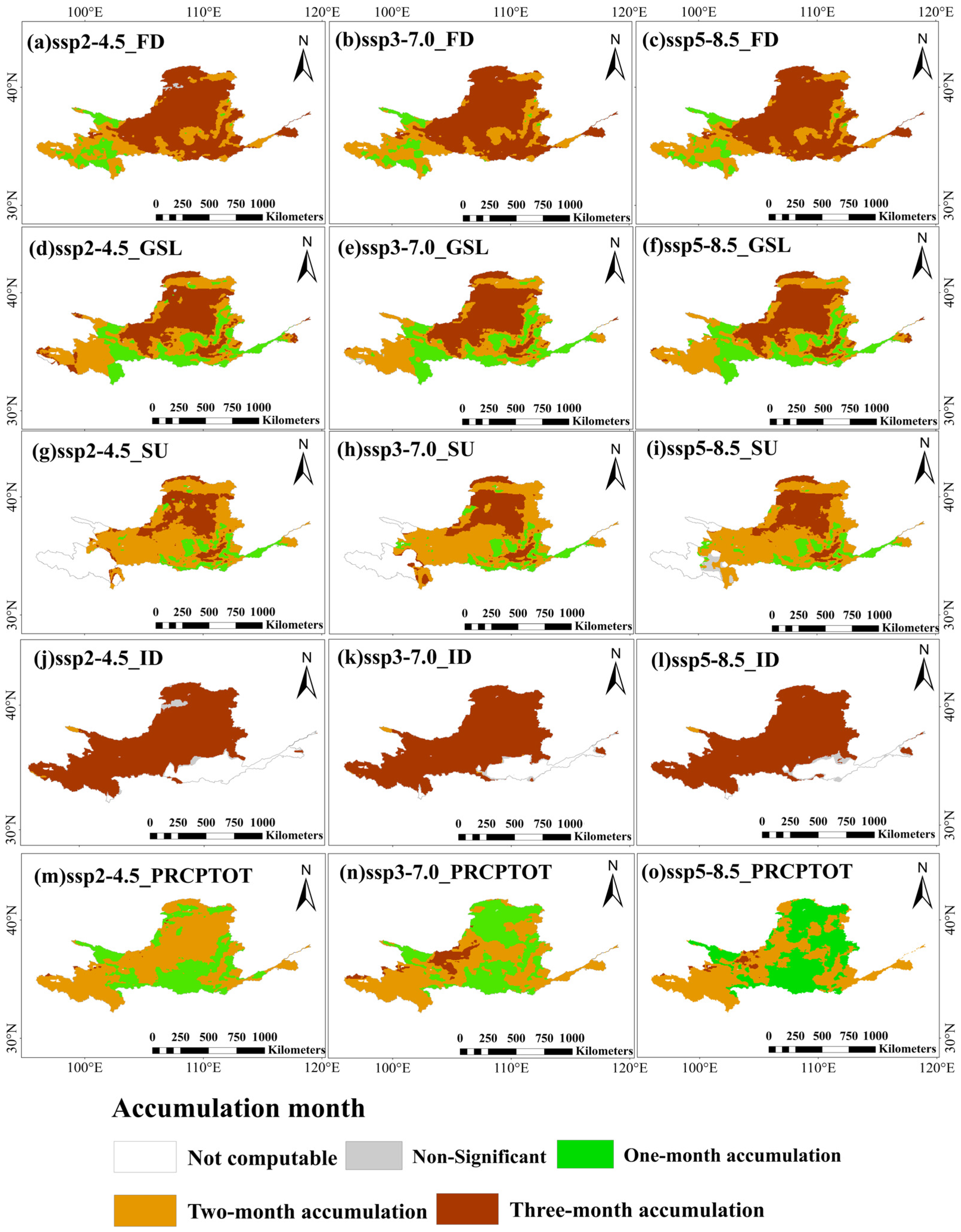

3.4. Time Lag Response of the LAI to the Extreme Indices

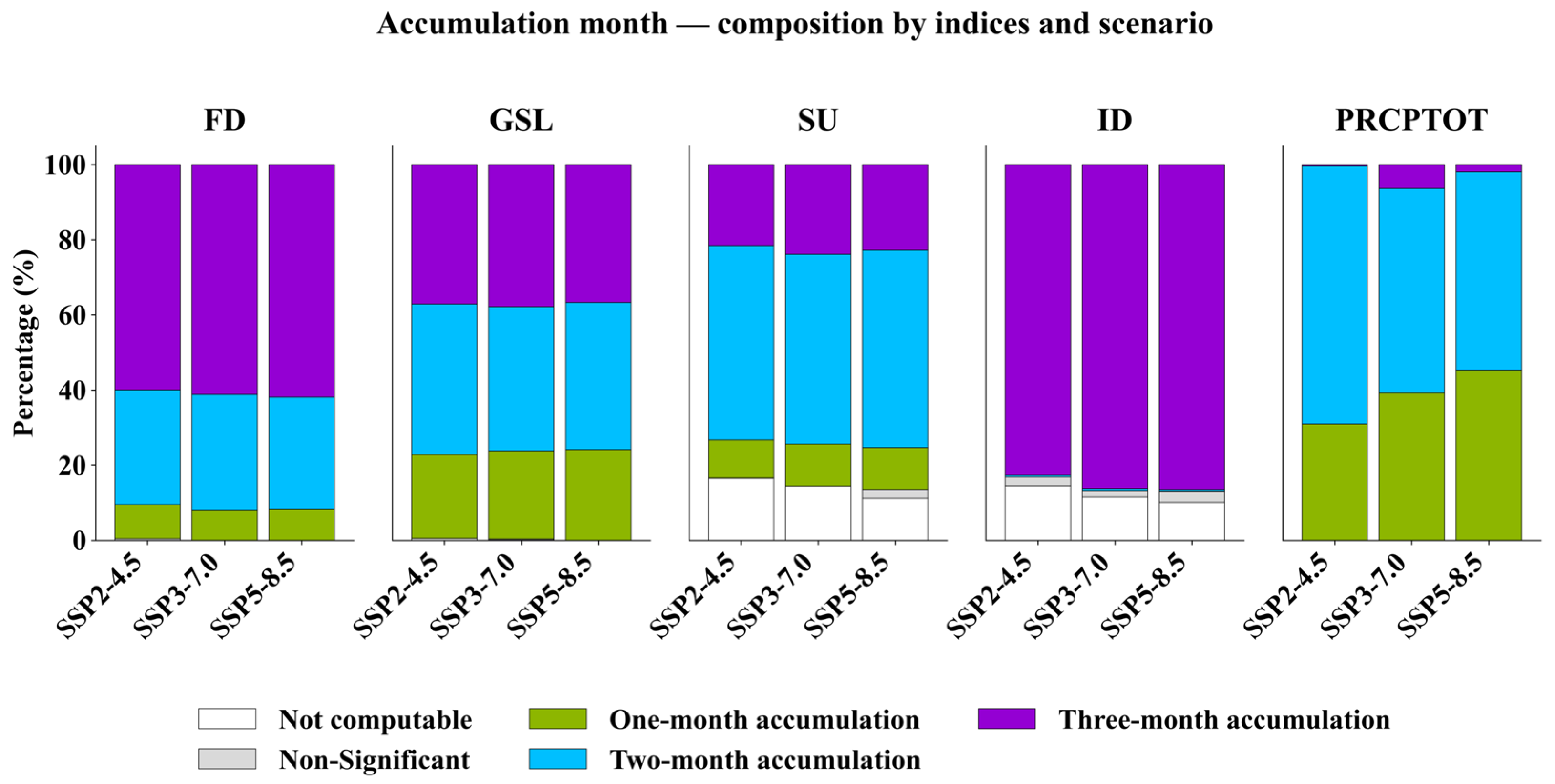

3.5. Time Cumulative Response of the LAI to the Extreme Indices

4. Discussion

4.1. Long-Term LAI Trends

4.2. Vegetation Response to Extreme Climate Indices

4.2.1. Time Lag Response of Vegetation to Extreme Climate

4.2.2. Time Cumulative Response of Vegetation to Extreme Climate

4.3. Limitations and Uncertainties

4.4. Policy Implications

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Under future SSP scenarios, the LAI in the YRB is projected to increase overall, and the proportions of improvement areas (slope > 0) are projected to be 98.55%, 97.24%, and 96.03%, respectively, which is likely due to the fertilization effect of elevated atmospheric CO2 concentrations. However, its spatial distribution is markedly heterogeneous. Vegetation degradation intensifies notably in the mid-stream’s eastern and southern regions under high-emission scenarios like SSP5-8.5.

- (2)

- Based on the PLSR and VIP scores, the LAI is strongly correlated with five extreme climate indices: FD, ID, SU, GSL, and PRCPTOT. Their cumulative and lagged effects highlight the complex vegetation response to extreme climates. PRCPTOT, GSL, and FD significantly influence most parts of the basin, whereas ID and SU have more scenario-specific spatial impacts.

- (3)

- Across all three future scenarios, vegetation responses in the YRB exhibited strong regional heterogeneity in terms of both lag and cumulative effects. PRCPTOT exerted a critical influence on vegetation responses, with rapid adjustments (0–1 month lag) dominating in regions with balanced hydro-climatic conditions, while longer cumulative periods were concentrated in transition zones and the source region, underscoring the essential role of precipitation as a water-supply factor in regulating LAI dynamics.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Meteorological Organization (WMO). State of the Global Climate 2024; WMO-No.1368: 2025; WMO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q.; Gao, L.; Meng, Q.; Zhu, M. Climate Warming Will Exacerbate Unequal Exposure to Compound Flood-Heatwave Extremes. Earth’s Future 2024, 12, e2024EF005179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, S.; Bai, Y.; Shi, S.; Cao, D. Spatiotemporal variations of water productivity for cropland and driving factors over China during 2001–2015. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 262, 107328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, Q.; Wang, J.; Wang, F.; Qiu, S.; Ai, M.; Zhao, J. Effects of land use/cover change on carbon storage between 2000 and 2040 in the Yellow River Basin, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 151, 110345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zailaa, J.; Scoffoni, C.; Brodersen, C.R. Stomatal closure as a driver of minimum leaf conductance declines at high temperature and vapor pressure deficit in Quercus. Plant Physiol. 2025, 197, kiae551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulva, I.; Välbe, M.; Merilo, E. Plants lacking OST1 show conditional stomatal closure and wildtype-like growth sensitivity at high VPD. Physiol. Plant. 2023, 175, e14030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, M.S.; Tang, H.; Aas, K.S.; Stordal, F.; Fisher, R.A.; Bjerke, J.W.; Holm, J.A.; Parmentier, F.J.W. Integration of a frost mortality scheme into the demographic vegetation model FATES. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2023, 15, e2022MS003333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suonan, J.; Lü, W.; Classen, A.T.; Wang, W.; La, B.; Lu, X.; Songzha, C.; Chen, C.; Miao, Q.; Sun, F. Alpine plants exhibited deep supercooling upon exposed to episodic frost events during the growing season on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Plant Ecol. 2024, 17, rtae034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuzwieser, J.; Papadopoulou, E.; Rennenberg, H. Interaction of flooding with carbon metabolism of forest trees. Plant Biol. 2004, 6, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, O.; Perata, P.; Voesenek, L.A. Flooding and low oxygen responses in plants. Funct. Plant Biol. 2017, 44, iii–vi. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamungkas, S.S.T.; Farid, N. Drought stress: Responses and mechanism in plants. Rev. Agric. Sci. 2022, 10, 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhang, J.; Han, J.; Bai, Y.; Xun, L.; Zhang, S.; Cao, D.; Wang, J. The ratio of transpiration to evapotranspiration dominates ecosystem water use efficiency response to drought. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2025, 363, 110423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, S.; Wang, J.; Zeng, R.; Zhang, S.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, J. Evapotranspiration Partitioning for Croplands Based on Eddy Covariance Measurements and Machine Learning Models. Agronomy 2025, 15, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Yu, M.; Xia, Y.; Sun, S.; Zhou, B. Impacts of Compound Hot–Dry Events on Vegetation Productivity over Northern East Asia. Forests 2024, 15, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Gou, X.; Wang, X.; Yang, M.; Qie, L.; Pang, G.; Wei, S.; Zhang, F.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; et al. Relationship between extreme climate and vegetation in arid and semi-arid mountains in China: A case study of the Qilian Mountains. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2024, 348, 109938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fensholt, R.; Langanke, T.; Rasmussen, K.; Reenberg, A.; Prince, S.D.; Tucker, C.; Scholes, R.J.; Le, Q.B.; Bondeau, A.; Eastman, R.; et al. Greenness in semi-arid areas across the globe 1981–2007—An Earth Observing Satellite based analysis of trends and drivers. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 121, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W. The Response of NDVI to Drought at Different Temporal Scales in the Yellow River Basin from 2003 to 2020. Water 2024, 16, 2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buermann, W.; Dong, J.; Zeng, X.; Myneni, R.B.; Dickinson, R.E. Evaluation of the Utility of Satellite-Based Vegetation Leaf Area Index Data for Climate Simulations. J. Clim. 2001, 14, 3536–3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Duan, T.; Chen, J.; Li, A. Continuous Leaf Area Index (LAI) Observation in Forests: Validation, Application, and Improvement of LAI-NOS. Forests 2024, 15, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Li, M.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zha, J.; Zhao, W.; Duanmu, Z.; Chen, J.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, Y.; et al. Spatiotemporally consistent global dataset of the GIMMS leaf area index (GIMMS LAI4g) from 1982 to 2020. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2023, 15, 4877–4899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, J.A.; Medvigy, D.M.; Smith, B.; Dukes, J.S.; Beier, C.; Mishurov, M.; Xu, X.; Lichstein, J.W.; Allen, C.D.; Larsen, K.S.; et al. Exploring the impacts of unprecedented climate extremes on forest ecosystems: Hypotheses to guide modeling and experimental studies. Biogeosciences 2023, 20, 2117–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; McDowell, N.G.; Fisher, R.A.; Wei, L.; Sevanto, S.; Christoffersen, B.O.; Weng, E.; Middleton, R.S. Increasing impacts of extreme droughts on vegetation productivity under climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2019, 9, 948–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Jiao, K.; Wu, S. Investigating the spatially heterogeneous relationships between climate factors and NDVI in China during 1982 to 2013. J. Geogr. Sci. 2019, 29, 1597–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, X.; Feng, H.; Wang, H.; Hao, C. The Spatiotemporal Evolution of Vegetation in the Henan Section of the Yellow River Basin and Mining Areas Based on the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S. Vegetation greening and its response to a warmer and wetter climate in the yellow river basin from 2000 to 2020. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Xie, Z.; Huang, X.; Cui, M.; Wang, W.; Li, Q. Vegetation Dynamics and Its Trends Associated with Extreme Climate Events in the Yellow River Basin, China. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, G.; Meng, Z.; Fu, Y. Drought and water-use efficiency are dominant environmental factors affecting greenness in the Yellow River Basin, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 834, 155479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, Q.; Singh, V.P. Temporal Dynamics of Fractional Vegetation Cover in the Yellow River Basin: A Comprehensive Analysis. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xue, H.; Dong, G.; Liu, X.; Lian, Y. Spatiotemporal Variation in Extreme Climate in the Yellow River Basin and its Impacts on Vegetation Coverage. Forests 2024, 15, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wei, L.; Zheng, Z.; Du, J. Vegetation cover change and its response to climate extremes in the Yellow River Basin. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 905, 167366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, T.; Liu, J.; He, P.X.; Shi, M.J.; Chi, Y.; Liu, C.; Hou, Y.T.; Wei, F.L.; Liu, D.H. Time Lag and Cumulative Effects of Extreme Climate on Coastal Vegetation in China. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wang, H.; Zhai, H.L.; Zhang, X.C.; Shakir, M.; Ma, J.Y.; Sun, W. Identifying thresholds of time-lag and accumulative effects of extreme precipitation on major vegetation types at global scale. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2024, 358, 110239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gu, T.; He, S.; Cheng, F.; Wang, J.; Ye, H.; Zhang, Y.; Su, H.; Li, Q. Extreme drought along the tropic of cancer (Yunnan section) and its impact on vegetation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyring, V.; Bony, S.; Meehl, G.A.; Senior, C.A.; Stevens, B.; Stouffer, R.J.; Taylor, K.E. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 2016, 9, 1937–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi, K.; van Vuuren, D.P.; Kriegler, E.; Edmonds, J.; O’Neill, B.C.; Fujimori, S.; Bauer, N.; Calvin, K.; Dellink, R.; Fricko, O.; et al. The Shared Socioeconomic Pathways and their energy, land use, and greenhouse gas emissions implications: An overview. Glob. Environ. Change-Hum. Policy Dimens. 2017, 42, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, B.C.; Kriegler, E.; Ebi, K.L.; Kemp-Benedict, E.; Riahi, K.; Rothman, D.S.; van Ruijven, B.J.; van Vuuren, D.P.; Birkmann, J.; Kok, K.; et al. The roads ahead: Narratives for shared socioeconomic pathways describing world futures in the 21st century. Glob. Environ. Change 2017, 42, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Han, M. Analysis of spatial and temporal characteristics and evolution of green total factor productivity in agriculture in the lower Yellow River basin. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1474813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, H.; Peng, J.; Zhu, Y.; Li, L.; Pan, B.; Huang, Q.; Li, J.; Zhang, Q. Research on geological and surfacial processes and major disaster effects in the Yellow River Basin. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2022, 65, 234–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Gao, G.; Ran, L.; Li, D.; Lu, X.; Fu, B. Extreme streamflow and sediment load changes in the Yellow River Basin: Impacts of climate change and human activities. J. Hydrol. 2023, 619, 129372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Cui, H.; Ren, L.; Yan, D.; Yang, X.; Yuan, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, M.; Xu, C.-Y. Will China’s Yellow River basin suffer more serious combined dry and wet abrupt alternation in the future? J. Hydrol. 2023, 624, 129871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, C.; Liang, C.; Zhao, L.; Jiang, S.; Niu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, L. Vegetation dynamics and its response to climate change in the Yellow River Basin, China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 892747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lin, Z.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Han, P.; Wang, B.; Wang, Z.; Wen, Z.; Shi, H.; Zhang, Z. Discriminating the impacts of vegetation greening and climate change on the changes in evapotranspiration and transpiration fraction over the Yellow River Basin. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 904, 166926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, T.; Guan, X.; Huang, J.; Shen, X.; Huang, X.; Zhang, G.; Han, D.; Fu, L.; Nie, J. The turning of ecological change in the Yellow River Basin. Hydrol. Process. 2023, 37, e15055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myneni, R.; Knyazikhin, Y.; Park, T. MOD15A2H MODIS/Terra Leaf Area Index/FPAR 8-Day L4 Global 500m SIN Grid V006; NASA EOSDIS Land Processes DAAC: Sioux Falls, SD, USA, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Pedelty, J.; Devadiga, S.; Masuoka, E.; Brown, M.; Pinzon, J.; Tucker, C.; Vermote, E.; Prince, S.; Nagol, J.; Justice, C.; et al. Generating a Long-term Land Data Record from the AVHRR and MODIS Instruments. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Barcelona, Spain, 23–28 July 2007; pp. 1021–1025. [Google Scholar]

- Verger, A.; Sánchez-Zapero, J.; Weiss, M.; Descals, A.; Camacho, F.; Lacaze, R.; Baret, F. GEOV2: Improved smoothed and gap filled time series of LAI, FAPAR and FCover 1 km Copernicus Global Land products. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 123, 103479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, K.; Pu, J.; Park, T.; Xu, B.; Zeng, Y.; Yan, G.; Weiss, M.; Knyazikhin, Y.; Myneni, R.B. Performance stability of the MODIS and VIIRS LAI algorithms inferred from analysis of long time series of products. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 260, 112438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Modeling and Assimilation Office. MERRA-2 inst3_2d_gas_Nx: 2D, 3-Hourly, Instantaneous, Single-Level, Assimilation, Aerosol Optical Depth Analysis, Version 5.12.4; NASA: Sioux Falls, SD, USA, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Biavati, G.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Rozum, I. ERA5 Hourly Data on Single Levels from 1940 to Present; CCD: Denver, CO, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Sabater, J. ERA5 Land Hourly Time-Series Data on Single Levels from 1950 to Present; ECEMS: Kyoto, Japan, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, X.; Liang, S. A dataset of 0.05-degree leaf area index in China during 1983–2100 based on deep learning network. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Sabater, J. ERA5-Land Monthly Averaged Data from 1950 to Present; Commission’s Copernicus Climate Change Service: Bologna, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkholz, J.; Müller, C. ISIMIP3 Soil Input Data; ISIMIP: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, S. Trend-preserving bias adjustment and statistical downscaling with ISIMIP3BASD (v1.0). Geosci. Model Dev. 2019, 12, 3055–3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, H.B. Nonparametric tests against trend. Econometrica 1945, 13, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, M.G. Rank Correlation Methods; Charles Griffin & Co. Ltd.: London, UK, 1975; p. 160. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, P.K. Estimates of the Regression Coefficient Based on Kendall’s Tau. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1968, 63, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gocic, M.; Trajkovic, S. Analysis of changes in meteorological variables using Mann-Kendall and Sen’s slope estimator statistical tests in Serbia. Glob. Planet. Change 2013, 100, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, R.; Luan, J.; Yang, J.; Xu, Z.; Xu, L.; Tian, J.; Lv, Z.; Chen, X.; Bai, Y. Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Multiple Drivers of Vegetation Cover in the Jinsha River Basin: A Geodetector-Based Analysis. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, R.; Leblanc, S.G. Parametric (modified least squares) and non-parametric (Theil–Sen) linear regressions for predicting biophysical parameters in the presence of measurement errors. Remote Sens. Environ. 2005, 95, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Motesharrei, S. Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Global NDVI Trends: Correlations with Climate and Human Factors. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 13233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raun, W.; Solie, J.; Martin, K.; Freeman, K.; Stone, M.; Johnson, G.; Mullen, R. Growth stage, development, and spatial variability in corn evaluated using optical sensor readings. J. Plant Nutr. 2005, 28, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Piao, S.; Tang, Z.; Peng, C.; Ji, W. Interannual variability in net primary production and precipitation. Science 2001, 293, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wold, S.; Sjöström, M.; Eriksson, L. PLS-regression: A basic tool of chemometrics. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2001, 58, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geladi, P.; Kowalski, B.R. Partial least-squares regression: A tutorial. Anal. Chim. Acta 1986, 185, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahieu, B.; Qannari, E.M.; Jaillais, B. Extension and significance testing of Variable Importance in Projection (VIP) indices in Partial Least Squares regression and Principal Components Analysis. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2023, 242, 104986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Bao, Y.; Luo, J.; Jin, X.; Xu, X.; Song, X.; Yang, G. Exploring the Best Hyperspectral Features for LAI Estimation Using Partial Least Squares Regression. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 6221–6241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzberger, C.; Guérif, M.; Baret, F.; Werner, W. Comparative analysis of three chemometric techniques for the spectroradiometric assessment of canopy chlorophyll content in winter wheat. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2010, 73, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, K., VII. Note on regression and inheritance in the case of two parents. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. 1895, 58, 240–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Zhao, X.; Liang, S.; Zhou, T.; Huang, K.; Tang, B.; Zhao, W. Time-lag effects of global vegetation responses to climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 2015, 21, 3520–3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, A.; Yu, Q.; Feng, L.; Zhang, A.; Pei, T. Evaluating the cumulative and time-lag effects of drought on grassland vegetation: A case study in the Chinese Loess Plateau. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 261, 110214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Wu, C.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Gonsamo, A. Satellite detection of cumulative and lagged effects of drought on autumn leaf senescence over the Northern Hemisphere. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 2174–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, R.; Guo, E.; Wang, Y.; Yin, S.; Bao, Y.; Sun, Z.; Mandula, N.; Bao, Y. Vegetation dynamics and its response to extreme climate on the inner mongolian plateau during 1982–2020. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhai, H.; Zhang, X.; Dong, X.; Hu, J.; Ma, J.; Sun, W. Time-lag and accumulation responses of vegetation growth to average and extreme precipitation and temperature events in China between 2001 and 2020. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 945, 174084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, R.; Chen, J.M. Retrospective retrieval of long-term consistent global leaf area index (1981–2011) from combined AVHRR and MODIS data. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2012, 117, G04003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Tian, Z.; Wei, H.; Liu, Y.; Yu, Y. Spatiotemporal evolution and driving mechanisms of vegetation in the Yellow River Basin, China during 2000–2020. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 138, 108832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Guo, Y.; Li, S.; Li, W.; Jin, X. Elevated CO2 concentrations contribute to a closer relationship between vegetation growth and water availability in the Northern Hemisphere mid-latitudes. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 084013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.Y.; Yang, Q.H.; Jiang, S.Z.; Zhan, B.; Zhan, C. Detection and Attribution of Vegetation Dynamics in the Yellow River Basin Based on Long-Term Kernel NDVI Data. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Hua, T.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Z.; Pereira, P. Divergent Changes in Vegetation Greenness, Productivity, and Rainfall Use Efficiency Are Characteristic of Ecological Restoration Towards High-Quality Development in the Yellow River Basin, China. Engineering 2024, 34, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, J.; Miao, P.; Tian, X.; Li, X.; Ma, N.; Abrar Faiz, M.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, Y. Estimating hydrological consequences of vegetation greening. J. Hydrol. 2022, 611, 128018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Yuan, Z.; Yin, J.; Yao, M.; Qin, T.; Lü, X.; Wu, G. Response of vegetation phenology to climate factors in the source region of the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers. J. Plant Ecol. 2024, 17, rtae046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, Y.; Yu, B.; Wu, C.; Zhao, Z. Spatiotemporal evolution of growing-season vegetation coverage and its natural-human drivers in the Yellow River Basin, China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2023, 34, 5849–5862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, S.; Wang, Z.; Liu, T.; Shalamzari, M.J. Effects of climate change on vegetation growth in the Yellow River Basin from 2000 to 2019. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Tian, L.; Zhao, X.; Wu, P. Study on the feedback effect of vegetation restoration on local precipitation in the Loess Plateau. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2021, 51, 1080–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Wang, L.; Schurgers, G.; Ciais, P.; Peñuelas, J.; Brandt, M.; Yang, H.; Huang, K.; Shen, Q. Global increase in the optimal temperature for the productivity of terrestrial ecosystems. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Li, M.; Zheng, Z.; Ma, Z. Regional applicability of seven meteorological drought indices in China. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2017, 60, 745–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, S.L.; Butt, N.; Maron, M.; McAlpine, C.A.; Chapman, S.; Ullmann, A.; Segan, D.B.; Watson, J.E. Conservation implications of ecological responses to extreme weather and climate events. Divers. Distrib. 2019, 25, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelake, R.M.; Wagh, S.G.; Patil, A.M.; Červený, J.; Waghunde, R.R.; Kim, J.-Y. Heat stress and plant–biotic interactions: Advances and perspectives. Plants 2024, 13, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, N.B.; Ottosen, C.-O.; Zhou, R. Exogenous melatonin alters stomatal regulation in tomato seedlings subjected to combined heat and drought stress through mechanisms distinct from ABA signaling. Plants 2023, 12, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, G.; Xue, B.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L. Spatiotemporal variation of evapotranspiration on different land use/cover in the inner Mongolia reach of the Yellow River Basin. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; Fang, X.; Yin, Z.; Hu, R. Warming-induced hydrothermal anomaly over the Earth’s three Poles amplifies concurrent extremes in 2022. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2024, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Cuo, L.; Zhang, Y. On the freeze–thaw cycles of shallow soil and connections with environmental factors over the Tibetan Plateau. Clim. Dyn. 2021, 57, 3183–3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCulloh, K.A.; Augustine, S.P.; Goke, A.; Jordan, R.; Krieg, C.P.; O’Keefe, K.; Smith, D.D. At least it is a dry cold: The global distribution of freeze–thaw and drought stress and the traits that may impart poly-tolerance in conifers. Tree Physiol. 2023, 43, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Z.; Tang, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, J.; Yue, J.; Xia, S. Satellite-Observed Hydrothermal Conditions Control the Effects of Soil and Atmospheric Drought on Peak Vegetation Growth on the Tibetan Plateau. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Wang, P.; Zhan, X.; Han, J.; Guo, M.; Wang, F. Warming and increasing precipitation induced greening on the northern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Catena 2023, 233, 107483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- le Roux, P.C.; Aalto, J.; Luoto, M. Soil moisture’s underestimated role in climate change impact modelling in low-energy systems. Glob. Change Biol. 2013, 19, 2965–2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, K.; Golam Dastogeer, K.; Carrillo, Y.; Nielsen, U.N. Climate change-driven shifts in plant–soil feedbacks: A meta-analysis. Ecol. Process. 2022, 11, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Du, X.; Du, Z.; Sun, M. Alpine grassland greening on the Northern Tibetan Plateau driven by climate change and human activities considering extreme temperature and soil moisture. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 916, 169995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Niu, B.; Zheng, Y.; He, Y.; Cao, Y.; Feng, Y.; Wu, J. Divergent Climate Sensitivities of the Alpine Grasslands to Early Growing Season Precipitation on the Tibetan Plateau. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulmatiski, A.; Yu, K.; Mackay, D.S.; Holdrege, M.C.; Staver, A.C.; Parolari, A.J.; Liu, Y.; Majumder, S.; Trugman, A.T. Forecasting semi-arid biome shifts in the Anthropocene. New Phytol. 2020, 226, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhong, C.; Jin, T.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, Z.; Wu, K. Stronger Impact of Extreme Heat Event on Vegetation Temperature Sensitivity under Future Scenarios with High-Emission Intensity. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, N.; Erika, H.; Christian, K. Critically low soil temperatures for root growth and root morphology in three alpine plant species. Alp. Bot. 2016, 126, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q. Global change hydrology: Terrestrial water cycle and global change. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2020, 63, 459–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naikwade, P.V. Plant responses to drought stress: Morphological, physiological, molecular approaches, and drought resistance. In Plant Metabolites under Environmental Stress; Apple Academic Press: Oakville, ON, Canada, 2023; pp. 149–183. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Lu, Q.; Gao, Q. Study on the volumes of water diverted from the yellow river to the irrigated area in the great bend of the yellow river. Arid Zone Res. 2005, 22, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, C.; Ogaya, R.; Fernández-Martínez, M.; Pugh, T.A.; Peñuelas, J. Increasing climatic sensitivity of global grassland vegetation biomass and species diversity correlates with water availability. New Phytol. 2021, 230, 1761–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Fu, B.J.; Lü, Y.H.; Du, C.J.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Wang, F.F.; Gao, G.Y.; Wu, X. Soil freeze-thaw cycles affect spring phenology by changing phenological sensitivity in the Northern Hemisphere. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 914, 169963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y. Groundwater in the Earth’s critical zone: Relevance to large-scale patterns and processes. Water Resour. Res. 2015, 51, 3052–3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karl, T.R.; Nicholls, N.; Ghazi, A. Clivar/GCOS/WMO workshop on indices and indicators for climate extremes workshop summary. In Weather and Climate Extremes: Changes, Variations and a Perspective from the Insurance Industry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; pp. 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, T.; Folland, C.; Gruza, G.; Hogg, W.; Mokssit, A.; Plummer, N. Report on the Activities of the Working Group on Climate Change Detection and Related Rapporteurs; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

| Scenario | Number of Components | R2 | Beta Coefficient | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FD | GSL | SU | ID | PRCPTOT | |||

| SSP2-4.5 | 6 | 0.805 | −0.44 | 0.12 | 0.13 | −0.16 | −0.44 |

| SSP3-7.0 | 6 | 0.805 | −0.60 | −0.15 | 0.24 | −0.25 | −0.24 |

| SSP5−8.5 | 6 | 0.824 | −0.67 | 0.12 | 0.09 | −0.15 | −0.36 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, S.; Wang, F.; Lyu, R.; Liu, M.; Nie, N. Response of Vegetation to Extreme Climate in the Yellow River Basin: Spatiotemporal Patterns, Lag Effects, and Scenario Differences. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3967. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243967

Zhou S, Wang F, Lyu R, Liu M, Nie N. Response of Vegetation to Extreme Climate in the Yellow River Basin: Spatiotemporal Patterns, Lag Effects, and Scenario Differences. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):3967. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243967

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Shilun, Feiyang Wang, Ruiting Lyu, Maosheng Liu, and Ning Nie. 2025. "Response of Vegetation to Extreme Climate in the Yellow River Basin: Spatiotemporal Patterns, Lag Effects, and Scenario Differences" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 3967. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243967

APA StyleZhou, S., Wang, F., Lyu, R., Liu, M., & Nie, N. (2025). Response of Vegetation to Extreme Climate in the Yellow River Basin: Spatiotemporal Patterns, Lag Effects, and Scenario Differences. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 3967. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243967