A Comprehensive Review on Hyperspectral Image Lossless Compression Algorithms

Highlights

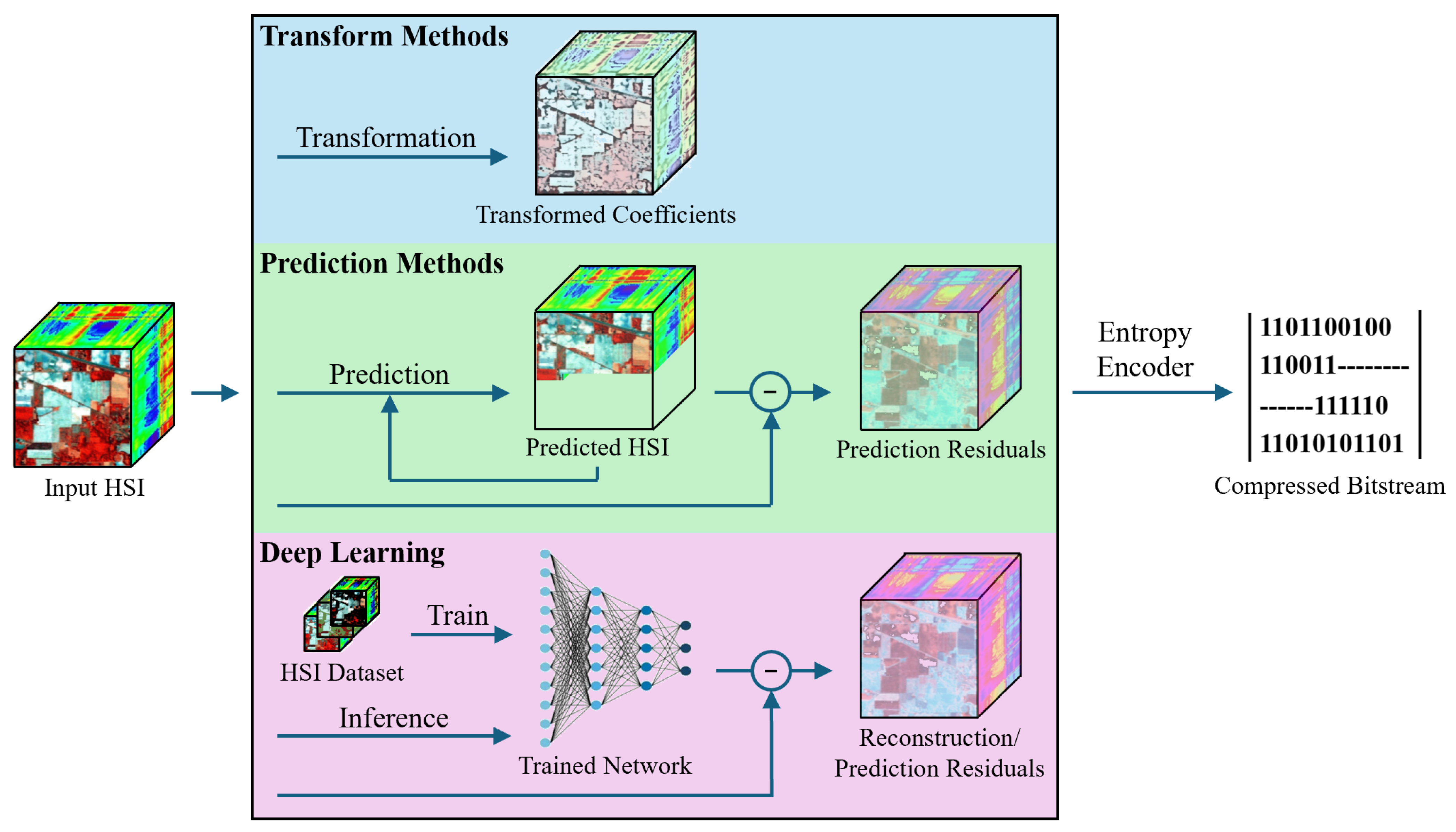

- The review provides a focused and systematic analysis of lossless hyperspectral image compression, categorizing existing algorithms into transform-based, prediction-based, and deep learning-based methods.

- It uniquely emphasizes the second stage of the compression pipeline—scanning and encoding order optimization—an aspect often overlooked in previous reviews but crucial for improving compression efficiency.

- By distinguishing the principles and performance characteristics of different algorithm classes, the review offers a comprehensive framework that helps researchers and practitioners select suitable lossless compression schemes for diverse remote-sensing applications.

- The analysis highlights future research directions, including the integration of deep learning with reversible transforms and the exploration of adaptive scanning strategies to enhance compression ratio and computational efficiency.

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Unique Characteristics of Hyperspectral Images

- High Dimensionality: Unlike RGB images that contain only three channels, HSIs consist of dozens to thousands of spectral bands, with each pixel representing a full, high-resolution spectrum. This high dimensionality results in extremely large data volumes, often reaching gigabytes per scene. Consequently, the goal of compression shifts from simple storage reduction to enabling practical data transmission and archiving. This demand necessitates highly efficient algorithms capable of exploiting all forms of data redundancy.

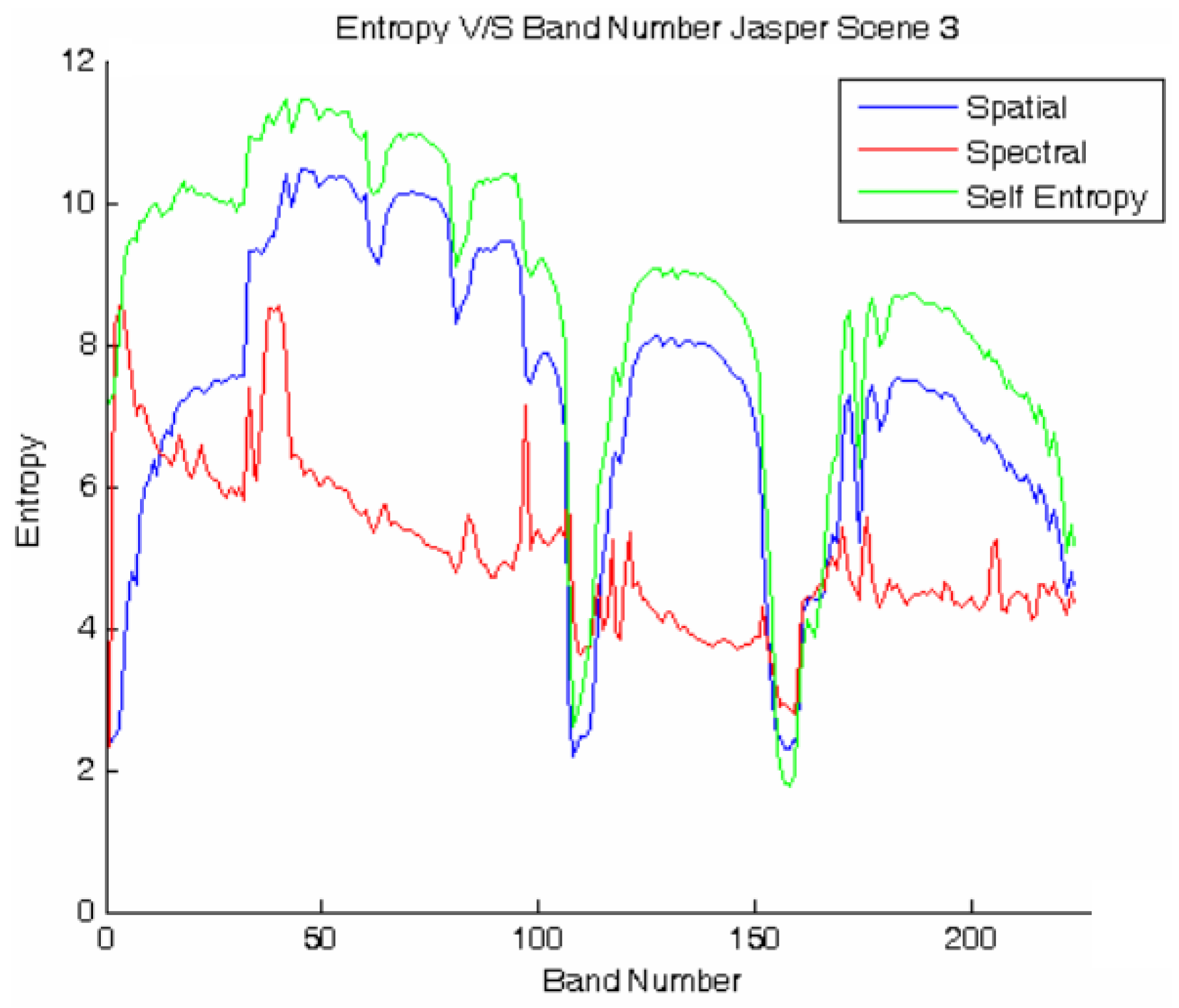

- Strong Spectral Correlation: A defining feature of HSIs is the strong correlation between adjacent spectral bands. Furthermore, the spectral correlation is often stronger than the spatial correlation within a single band. Therefore, algorithms that effectively leverage spectral correlation typically achieve superior compression performance compared with approaches that treat bands independently. This is a fundamental distinction from traditional 2D image compression, where the emphasis lies primarily on spatial redundancy.

- Spatial-Spectral Heterogeneity: Although spectral correlation is generally strong, its degree can vary significantly across different spatial regions and spectral ranges. For instance, homogeneous regions exhibit high correlation, whereas areas with sharp edges or material boundaries exhibit weaker correlation. This spatial-spectral heterogeneity complicates algorithm design, as a one-fits-all algorithm may be suboptimal. Effective methods must therefore adaptively balance the use of spatial and spectral context.

- Sensor-Specific Noise: Hyperspectral sensors are prone to various noise sources and artifacts, including thermal noise, shot noise and striping. In lossless compression, all information must be perfectly preserved. Because noise introduces randomness that is inherently uncorrelated with both spatial and spectral neighbors, it reduces the predictability of pixel values, which directly limits the compression ratios. Compression algorithms must be robust in the presence of noises without suffering substantial performance degradation.

1.2. Evaluation Metrics

1.3. Notations

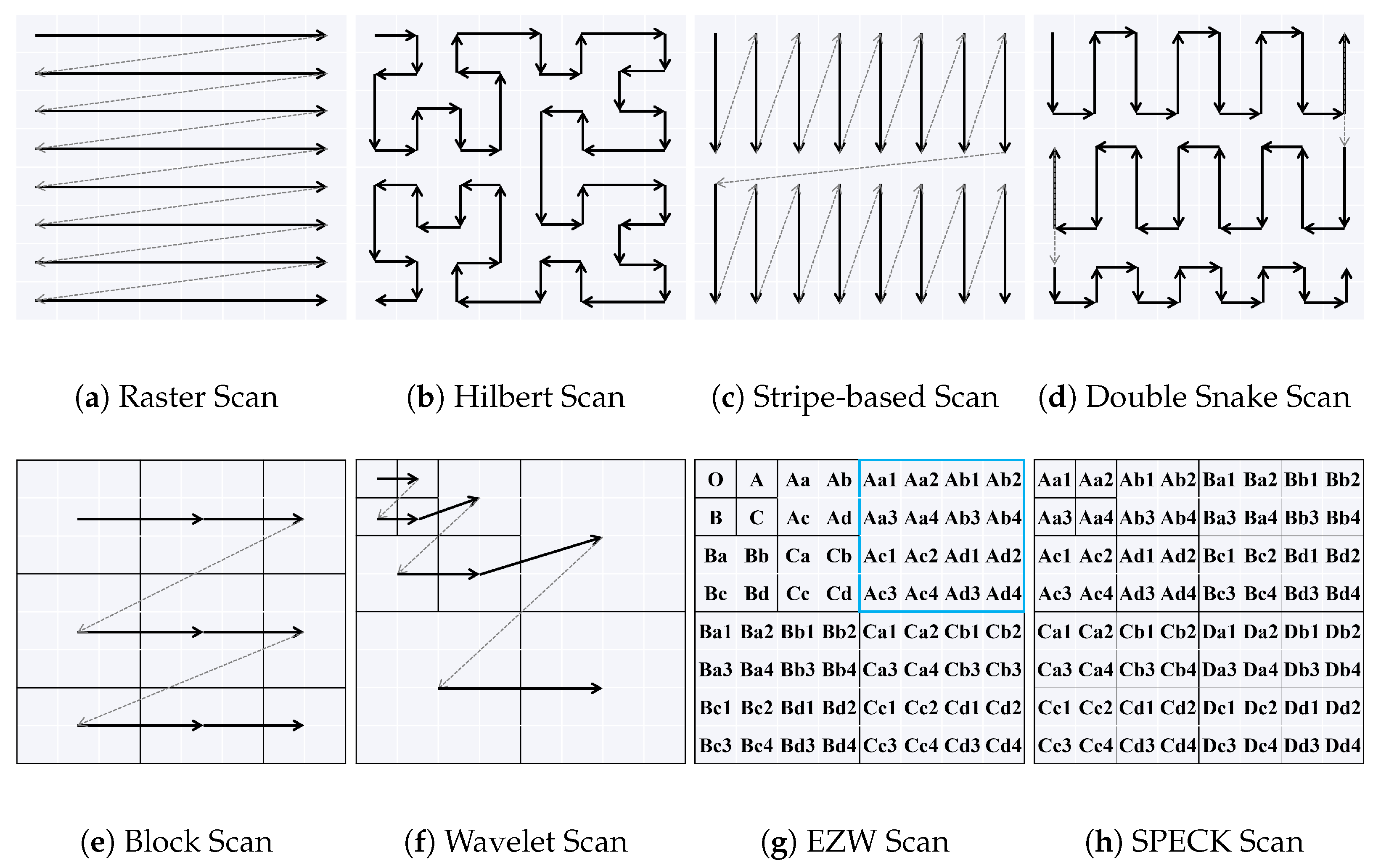

2. Scanning and Encoding Patterns

2.1. Scanning Patterns

2.1.1. 2D Scanning Patterns

Raster Scan

Hilbert Scan

Stripe-Based Scan

Double Snake Scan

Block Scan

2.1.2. 3D Scanning Patterns

3D Extensions of 2D Patterns

Wavelet Scan

- Embedded Zerotrees of Wavelet Transforms: This method [20,21] is also named as Embedded Zerotree Wavelet (EZW). The scanning order of EZW is shown in Figure 3g, where the indexes represent the hierarchical structure. All coefficients, except those in the highest and lowest decomposition levels, have four direct descendants. For example, coefficients Aa, Ab, Ac, and Ad are the direct descendants of coefficient A, while Aa1, Aa2, Aa3, and Aa4 are the direct descendants of Aa. By inheritance, all coefficients within the blue box are descendants of A. If a coefficient and all its descendants (both direct and indirect) are insignificant, they are encoded into a single output, reducing the file size.

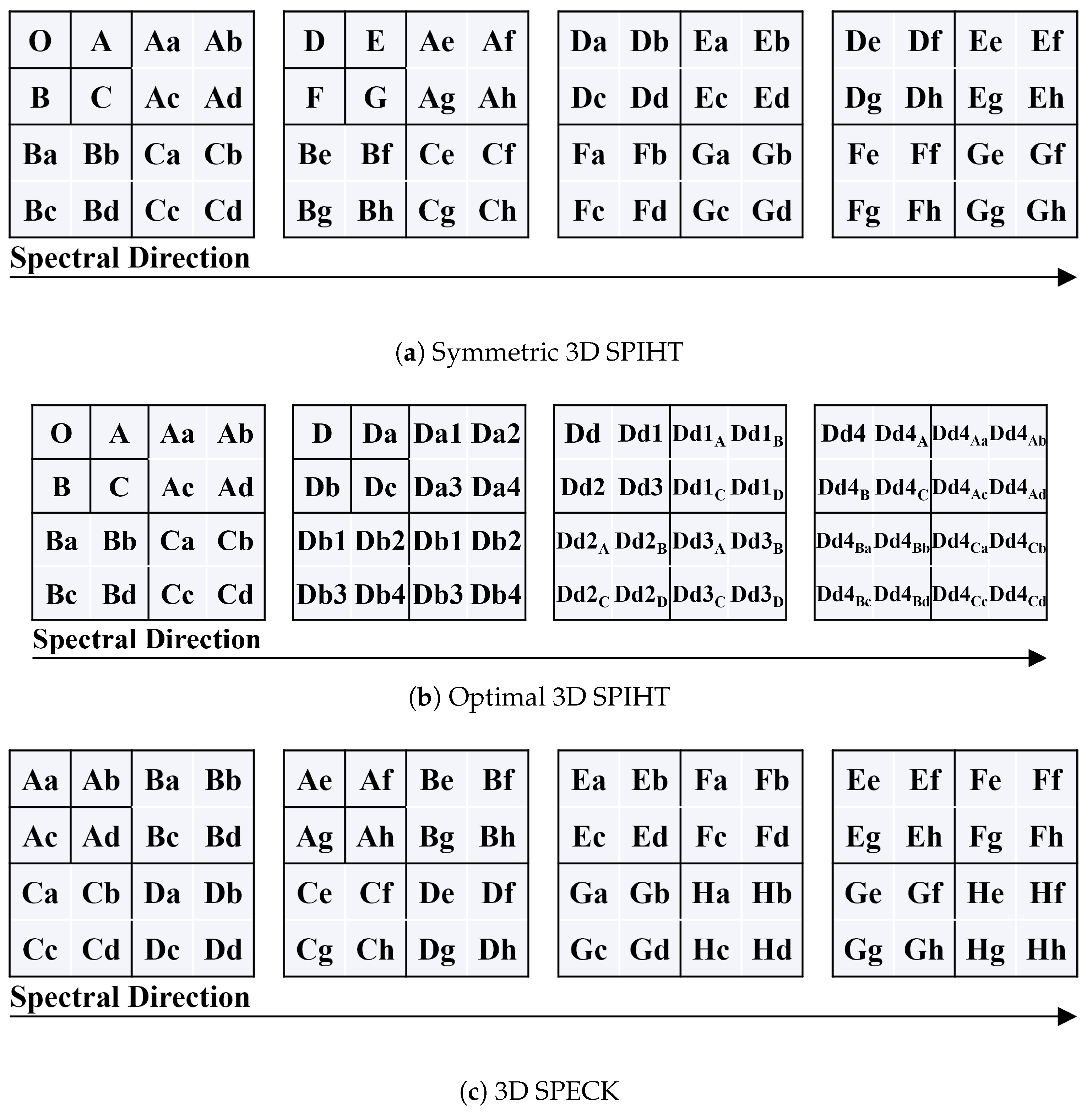

- Set Partitioning in Hierarchical Trees: SPIHT [22] is an improved version of EZW. One drawback of EZW is that it requires five outputs if a coefficient is significant but all its descendants are insignificant. SPIHT addresses this by separating the encoding of the coefficient from its descendants. As a result, the same example can be encoded with only two outputs instead of five. The extension of EZW and SPIHT from 2D to 3D can follow similar scanning orders, where the encoding pattern is applied separately to each bit-plane and spectral band. Alternatively, a more systematic extension can be implemented by increasing the number of direct descendants for each coefficient from four to eight (or from three to seven for low-frequency coefficients) [24], as shown in Figure 4a, which illustrates a 2-level 3D DWT. However, this structure is broad and shallow, lacking optimization of wavelet coefficients’ inter-dependencies. An optimized hierarchical structure is proposed in [25], capping the number of direct descendants at four, as shown in Figure 4b. Besides modifying the scanning order, a variation of SPIHT, known as 3D-Wavelet Block Tree Coding (3D-WBTC) [26], classifies each block into three types and encodes them using different rules.

- Set Partitioning Embedded Block: The aforementioned scanning orders utilize the spatial and spectral consistency of wavelet coefficients, where coefficients derived from the same set of pixels tend to have similar magnitudes. In contrast, SPECK [23] leverages sub-band consistency, where coefficients within the same sub-band exhibit similar magnitudes. This leads to a different hierarchical structure, as depicted in Figure 3h. If all coefficients with identical initial indices, such as “Ba” to “Bh”, are insignificant, they can be encoded as a single output. The 3D extension of SPECK is done by grouping wavelet coefficients into 3D cubes instead of 2D blocks, as illustrated in Figure 4c. It is noteworthy that the concept of 3D SPECK can be applied to non-wavelet coefficients as well, such as the k2-raster coding method in [27]. Besides, SPECK can be further enhanced by ZM-SPECK [28], which reduces the memory requirements while encoding.

2.2. Encoding Methods

2.2.1. Pixel-Based Encoding

Straight Coding

Huffman Coding

Run Length Coding

Golomb Coding

- Golomb Coding It is an optimal prefix code when the input follows a Laplace distribution. It encodes a non-negative integer pixel value into a codeword consisting of two parts: a prefix and a suffix. The prefix contains the unary code of , and the suffix represents the truncated binary form of , with a bit length of . Here, and represent the floor and ceiling operations respectively, is the remainder when p is divided by M. The most widely used implementation of M can be determined from the mean absolute error of previously encoded data. Other adaptions of M include geometrical distribution [36], correlation-based adaptation [37] and deep learning-based estimation [38].

- Golomb-Rice Coding This variation is a simplified variant of standard Golomb coding, where M is restricted to a power of 2, i.e., for some non-negative integer . The value of M is computed by rounding down the sample mean of previously encoded data to the nearest power of 2. This constraint significantly improves computational efficiency, making Golomb-Rice coding popular in many compression algorithms [39].

- Exponential-Golomb coding This encodes a pixel value p into a codeword composed of two parts: a prefix and a suffix. The prefix contains the unary code of , and the suffix holds the truncated binary form of , with a bit length of . It is worth noting that exponential-Golomb coding is quite similar to the Huffman encoding used for DC coefficients in JPEG. A similar encoder named integer square root is described in [40], where the square root value of p is recorded in 4-bits binary form, and the residual is encoded as unary.

Context-Based Extensions

2.2.2. Bit-Based Encoding

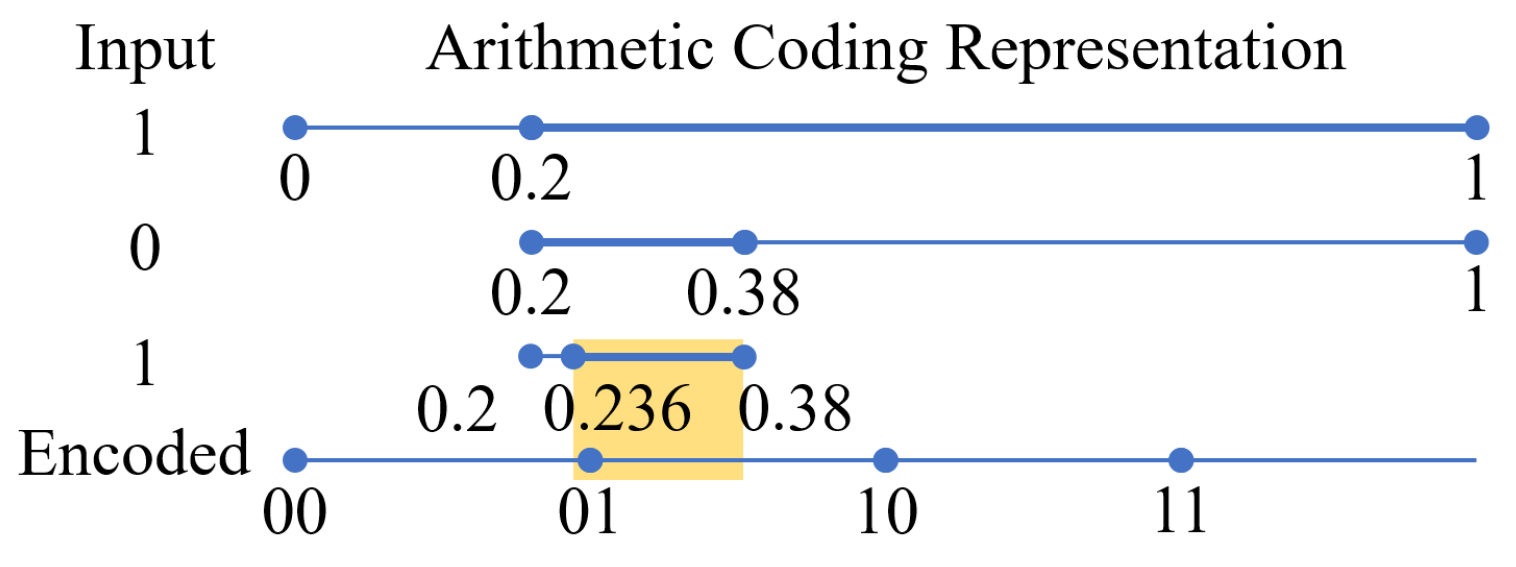

Arithmetic Coding

- If , then and ;

- If , then , ;

- If and , then , .

Range Coding

Asymmetric Numeral Systems

3. Transform Methods

3.1. Discrete Cosine Transform

3.2. Karhunen–Loeve Transform

3.3. Discrete Wavelet Transform

3.3.1. Wavelet Filters

3.3.2. Wavelet Packet Transform

3.3.3. Multiwavelet Transform

3.3.4. Regression Wavelet Transform

3.3.5. Dyadic Wavelet Transform

3.4. JPEG2000-Based Methods

3.5. Simple Modification from 2D Compression Methods

3.5.1. Spectral Decorrelation

3.5.2. 3D to 2D Image Conversion

3.6. Irreversible Transforms with Residual Encoding

3.7. Vector Quantization

3.7.1. VQ Parameters

3.7.2. VQ Techniques

3.8. Modification Add-Ons: Clustering

4. Prediction Methods

4.1. Lookup Table

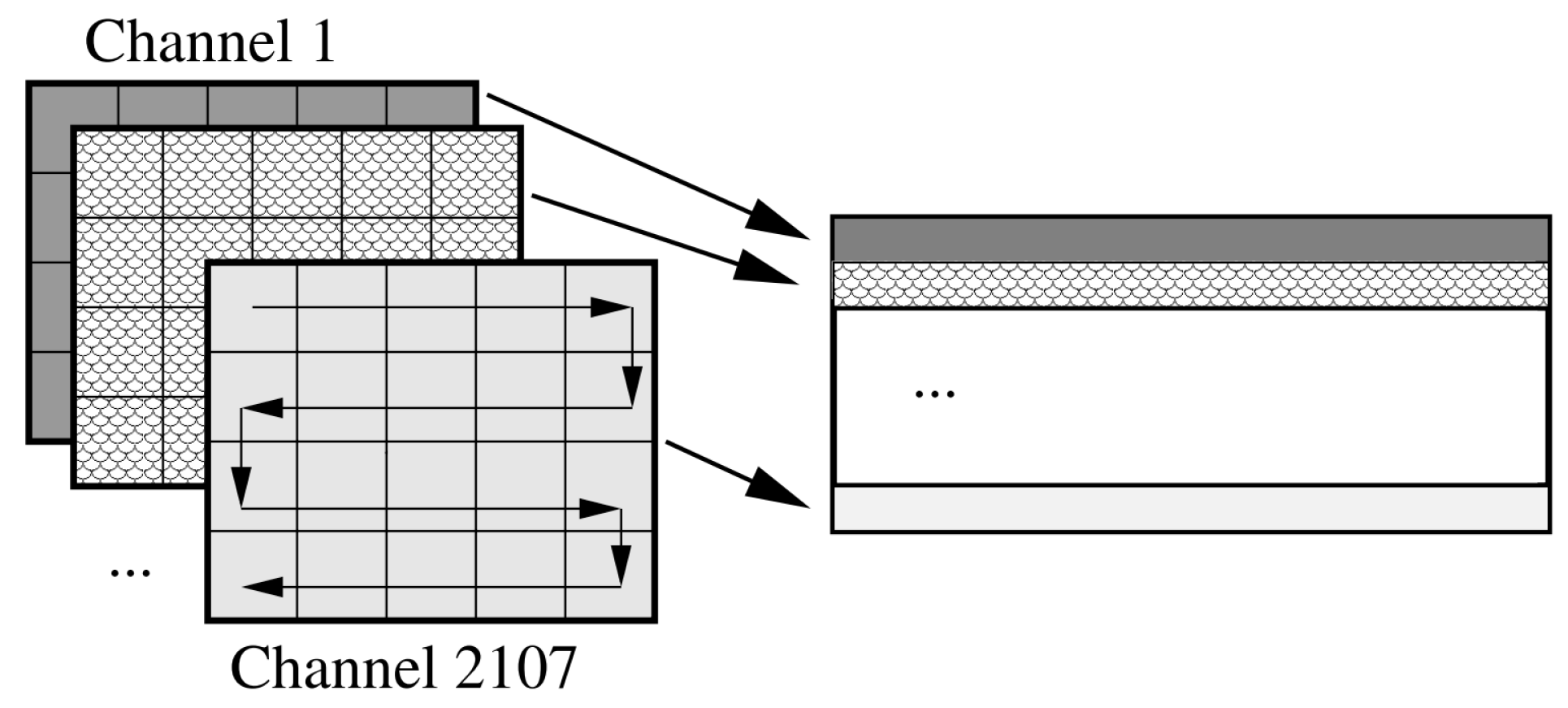

4.1.1. Locally Averaged Interband Scaling

4.1.2. LUT with Outliers

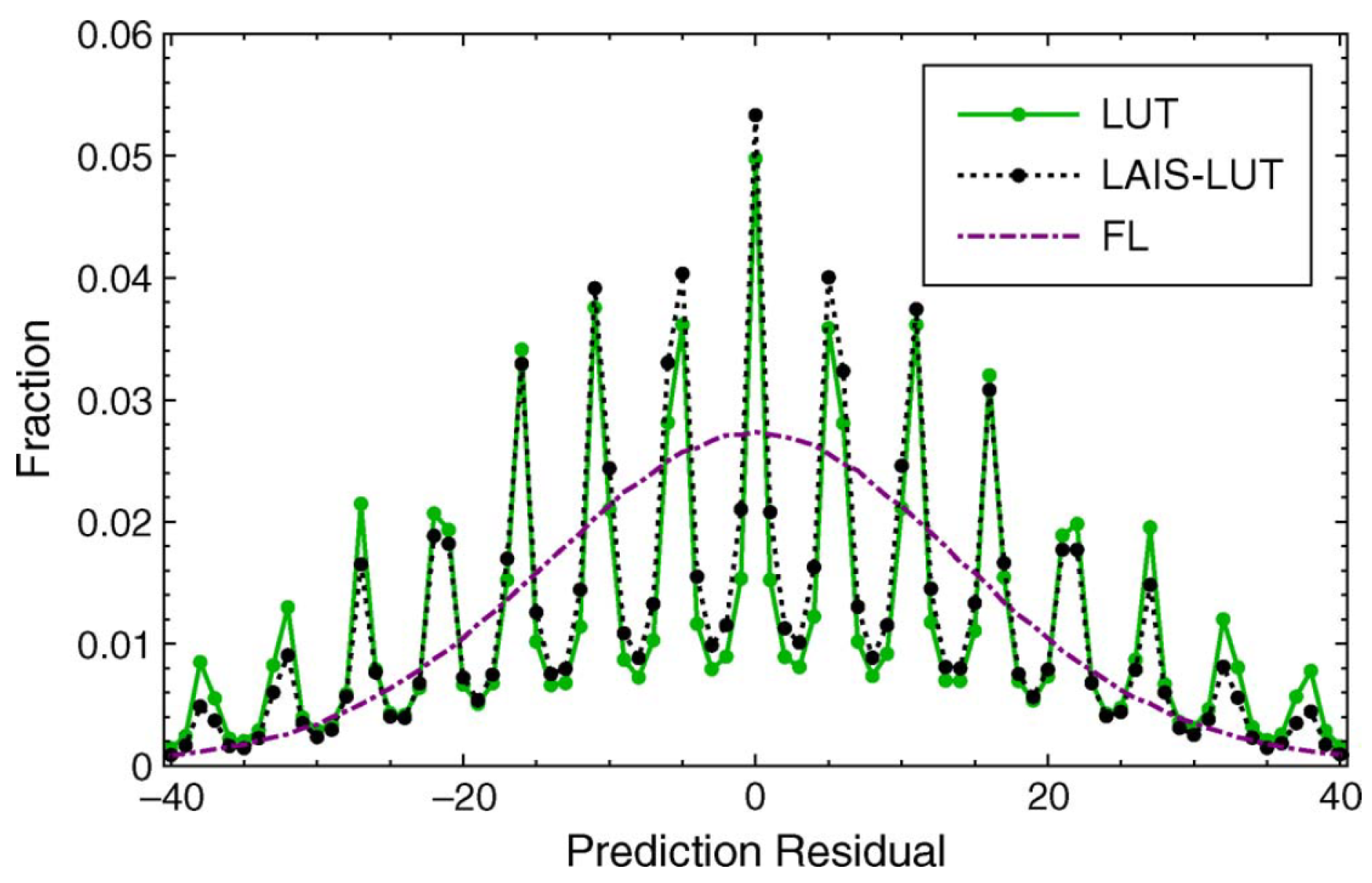

4.1.3. Prediction Residuals of LUT

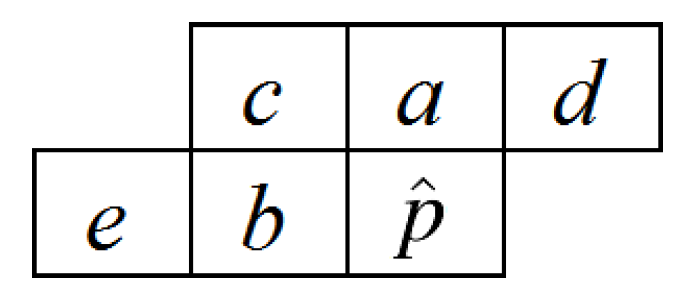

4.2. Spatial Predictors

4.2.1. Median Edge Detector

4.2.2. Gradient Adjusted Predictor

4.3. Differential Predictor

4.3.1. Scaling Factor of DP

4.3.2. Higher Order DP

4.4. Linear Predictor

4.4.1. Weight Vector of LP

4.4.2. Lenghth of Weight Vector

4.5. Hybrid Methods

4.5.1. Pre-Processing with Spectral Decorrelation

4.5.2. Pre-Processing with Spatial Decorrelation

4.5.3. Cascading Different Predictors

4.5.4. Cascading Bias Cancellation to Predictors

4.5.5. Band Adaptive Selection

4.5.6. Block Adaptive Selection

4.5.7. Kalman Filtering

4.6. CCSDS

4.7. CALIC

4.7.1. 2D CALIC

4.7.2. 3D-CALIC

4.7.3. Multiband CALIC

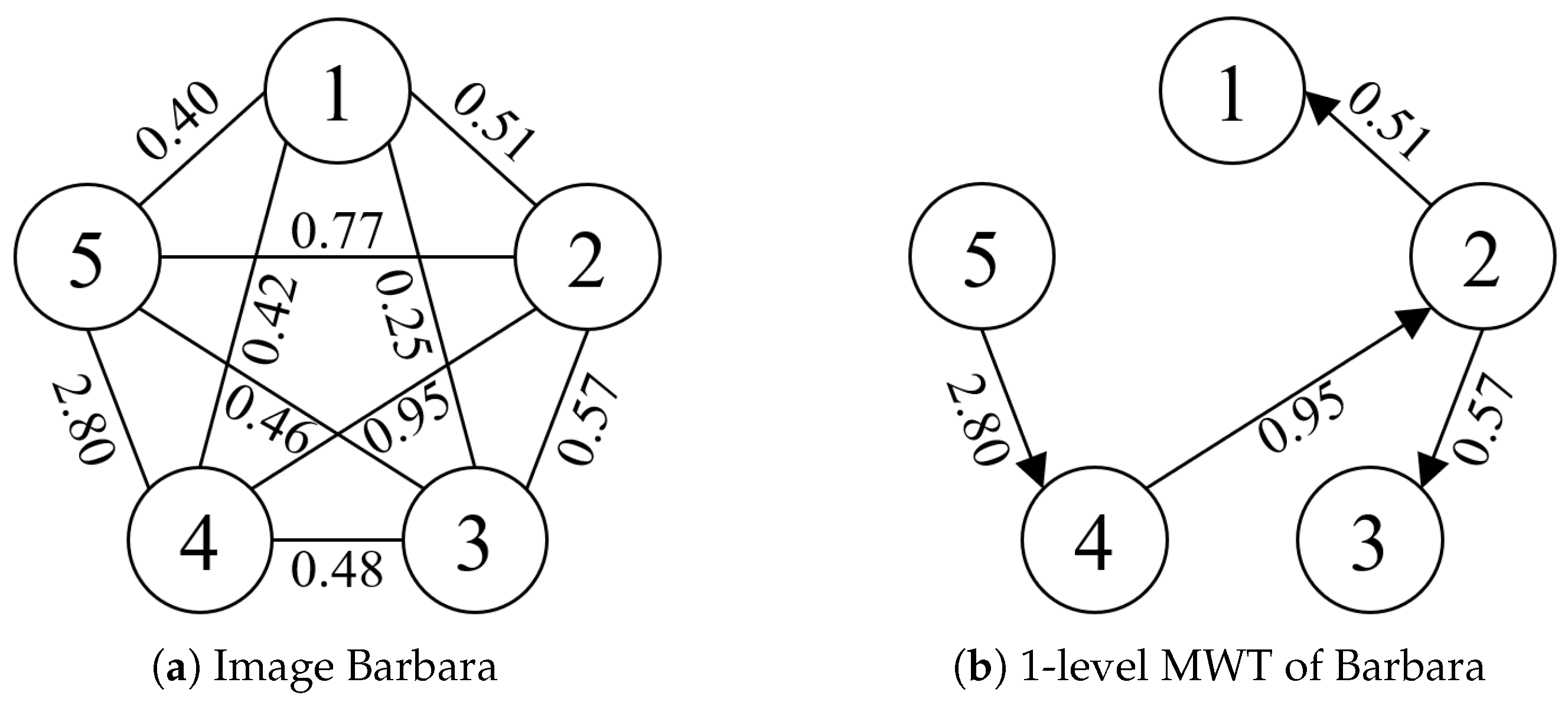

4.8. Modification Add-Ons: Band Reordering

5. Deep Learning

5.1. Deep Learning as Irreversible Transforms

5.2. Deep Learning as Prediction Methods

5.3. Challenges in Strictly Lossless Compression

- Entropy Modeling and Residual Encoding: The prediction or reconstruction residuals generated by deep networks often deviate significantly from the smooth, Laplacian-like distributions that traditional entropy coders are optimized for. These residuals can be sparse, multi-modal, or exhibit irregular patterns. Consequently, the bit savings from the compact latent representation can be offset by the cost of encoding the residuals, reducing the overall performance.

- Computational and Memory Overhead: The computational and memory footprint of deep models is typically orders of magnitude higher than that of traditional algorithms like CCSDS-123. The requirements for powerful GPUs/CPUs and large RAM buffers are incompatible with the low-power, radiation-hardened hardware used in spaceborne or aerial platforms, making real-time, onboard inference infeasible for most current architectures.

- Limited Generalizability: A model trained on one type of HSI often generalizes poorly to data from different sources or with different characteristics, due to changes in the underlying data distribution. Furthermore, deep networks may overfit to the specific statistical properties of their training set, learning to exploit redundancies that do not generalize across scenes. As a result, when encountering a new type of scene, prediction accuracy declines, yielding larger residuals and ultimately reducing the compression ratio.

6. Algorithm Performance and Comparative Assessment

6.1. Quantitative Comparisons

6.2. Comparative Analysis of Algorithm Categories

- Transform methods decorrelate HSI by projecting it into a different domain. The main strength lies in exploiting global redundancies while enabling useful features such as progressive transmission and multi-resolution analysis, which are advantageous for data browsing and scalable streaming. However, the computational cost and large memory footprint make them less suitable for real-time, on-board compression. Overall, for use cases requiring broad compatibility and convenient decoding, transform-based approaches, particularly JPEG2000 with 3D-to-2D conversion, offer a practical and effective solution.

- Prediction methods estimate each pixel from its neighbors and encode the resulting prediction residuals. They typically achieve high compression efficiency with low complexity, due to the ability to capture local spatial and spectral correlations with minimal memory usage. The main drawbacks are limited parallelization due to sequential processing and a vulnerability to error propagation. Despite these constraints, prediction-based approaches, especially the CCSDS-123 standard, remain highly suitable for resource-constrained platforms such as satellite on-board systems, where low computational demand and strong overall performance are essential.

- Deep learning methods replace manually designed transforms and predictors with data-driven deep networks. Their key advantage is the capacity to learn complex nonlinear spatial-spectral dependencies, enabling flexible and potentially superior compression. The primary challenges include high training costs, limited interpretability, and the lack of standardized frameworks. Nevertheless, deep learning-based prediction currently shows the greatest promise for future advances, particularly in scenarios with severe storage constraints where a model can be tailored to a specific hyperspectral dataset to achieve near-optimal performance in controlled, ground-based processing environments.

7. Conclusions

- The trade-offs between compression efficiency and computational complexity, which limit practical deployment in real-time or resource-constrained scenarios.

- The lack of standardized and universal datasets that are consistently tested across different methods, hindering fair comparisons and reproducibility.

- Robust performance across diverse scenes, varying noise conditions, and heterogeneous acquisition scenarios continues to be a major challenge.

- The limited adaptability of existing entropy coders to the highly correlated and complex distributions inherent in hyperspectral data.

- The prevalence of traditional methods that are largely based on permutations or incremental modifications of existing techniques, restricting significant innovation.

- The insufficient exploration and development of learning-based methods that strictly adhere to lossless requirements, leaving their potential untapped.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yuen, P.W.; Richardson, M. An introduction to hyperspectral imaging and its application for security, surveillance and target acquisition. Imaging Sci. J. 2010, 58, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, N.; Parbhakar-Fox, A.; Moltzen, J.; Feig, S.; Goemann, K.; Huntington, J. Applications of hyperspectral mineralogy for geoenvironmental characterisation. Miner. Eng. 2017, 107, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willoughby, C.T.; Folkman, M.A.; Figueroa, M.A. Application of hyperspectral-imaging spectrometer systems to industrial inspection. In Proceedings of the Three-Dimensional and Unconventional Imaging for Industrial Inspection and Metrology. International Society for Optics and Photonics, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 19 January 1996; Volume 2599, pp. 264–272. [Google Scholar]

- Park, B.; Lu, R. Hyperspectral Imaging Technology in Food and Agriculture; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Obermeier, W.A.; Lehnert, L.W.; Pohl, M.J.; Gianonni, S.M.; Silva, B.; Seibert, R.; Bendix, J. Grassland ecosystem services in a changing environment: The potential of hyperspectral monitoring. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 232, 111273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 15444-1; Information Technology—JPEG 2000 Image Coding System—Part 1: Core Coding System. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000.

- Fei, B. Chapter 3.6—Hyperspectral imaging in medical applications. In Hyperspectral Imaging; Amigo, J.M., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, Data Handling in Science and Technology; 2019; Volume 32, pp. 523–565. [Google Scholar]

- Selci, S. The future of hyperspectral imaging. J. Imaging 2019, 5, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dua, Y.; Kumar, V.; Singh, R.S. Comprehensive review of hyperspectral image compression algorithms. Opt. Eng. 2020, 59, 090902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrin, A.; Al Mamun, M. A comprehensive review of deep learning methods for hyperspectral image compression. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advancement in Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Gazipur, Bangladesh, 25–27 April 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Chen, C.; Wan, Y. A survey on hyperspectral remote sensing image compression. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Pasadena, CA, USA, 16–21 July 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 7400–7403. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Bovik, A.C.; Sheikh, H.R.; Simoncelli, E.P. Image quality assessment: From error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2004, 13, 600–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruse, F.A.; Lefkoff, A.B.; Boardman, J.W.; Heidebrecht, K.B.; Shapiro, A.; Barloon, P.; Goetz, A.F. The spectral image processing system (SIPS)—interactive visualization and analysis of imaging spectrometer data. Remote Sens. Environ. 1993, 44, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, V.; Rani, J.S. A band interleaved by line (BIL) architecture of a simple lossless algorithm (SLA) for on-board satellite hyperspectral data compression. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Circuits and Systems, London, UK, 25–28 May 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, V.; Rani, J.S. A band interleaved by pixel (BIP) architecture of a simple lossless algorithm (SLA) for on-board satellite hyperspectral data compression. In Proceedings of the IEEE Interregional NEWCAS Conference, Paris, France, 22–25 June 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 490–494. [Google Scholar]

- Lempel, A.; Ziv, J. Compression of two-dimensional data. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1986, 32, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, N.; Neuhoff, D.; Shende, S. An analysis of some common scanning techniques for lossless image coding. In Proceedings of the Conference Record of the Thirty-First Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems and Computers, Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 2 November–5 November 1997; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 1997; Volume 2, pp. 1446–1450. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, F.; Wang, H.; Yang, L.; Li, C.; Wang, S. Lossless Compression for Hyperspectral Images based on Adaptive Band Selection and Adaptive Predictor Selection. Ksii Trans. Internet Inf. Syst. 2020, 14, 3295–3311. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, L.; Liang, B.; Li, M.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Ding, J. Efficient 3D Hilbert curve encoding and decoding algorithms. Chin. J. Electron. 2022, 31, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, J. Embedded image coding using zerotrees of wavelet coefficients. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 1993, 41, 3445–3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagendran, R.; Ramadass, S.; Thilagavathi, K.; Ravuri, A. Lossless hyperspectral image compression by combining the spectral decorrelation techniques with transform coding methods. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2024, 45, 6226–6248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.J.; Pearlman, W. An embedded wavelet video coder using three-dimensional set partitioning in hierarchical trees (SPIHT). In Proceedings of the DCC ’97. Data Compression Conference, Snowbird, UT, USA, 25–27 March 1997; pp. 251–260. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlman, W.; Islam, A.; Nagaraj, N.; Said, A. Efficient, low-complexity image coding with a set-partitioning embedded block coder. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2004, 14, 1219–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Liu, Z. 3D wavelet video codec and its rate control in ATM network. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Circuits and Systems, Orlando, FL, USA, 30 May–2 June 1999; Volume 4, pp. 447–450. [Google Scholar]

- Bajpai, S. Low Complexity Image Coding Technique for Hyperspectral Image Sensors. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 31233–31258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, S.; Kidwai, N.R.; Singh, H.V.; Singh, A.K. Low memory block tree coding for hyperspectral images. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2019, 78, 27193–27209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, K.; Tzamarias, D.E.O.; Hernández-Cabronero, M.; Blanes, I.; Serra-Sagristà, J. Analysis of Variable-Length Codes for Integer Encoding in Hyperspectral Data Compression with the k 2-Raster Compact Data Structure. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, S.; Kidwai, N.R.; Singh, H.V.; Singh, A.K. A low complexity hyperspectral image compression through 3D set partitioned embedded zero block coding. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 841–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Chen, J.; Ai, Y.; Rahardja, S. An Optimized Quantization Constraints Set for Image Restoration and its GPU Implementation. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2020, 29, 6043–6053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Ko, C.; Rahardja, S.; Lin, X. Bit-plane Golomb coding for sources with Laplacian distributions. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, Hong Kong, China, 6–10 April 2003; Volume 4, p. IV–277. [Google Scholar]

- Anand Swamy, A.; Mamatha, A.; Shylashree, N.; Nath, V. Lossless Compression of Hyperspectral Imagery by Assimilating Decorrelation and Pre-processing with Efficient Displaying Using Multiscale HDR Approach. IETE J. Res. 2022, 69, 6673–6684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Song, Z.; Deng, G.; Ma, Y.; Ma, P. Differential prediction-based lossless compression with very low-complexity for hyperspectral data. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Communication Technology, Jinan, China, 25–28 September 2011; pp. 323–327. [Google Scholar]

- Mamatha, A.; Singh, V. Lossless hyperspectral image compression based on prediction. In Proceedings of the IEEE Recent Advances in Intelligent Computational Systems, hlTrivandrum, India, 19–21 December 2013; pp. 193–198. [Google Scholar]

- Mamatha, A.S.; Singh, V. Lossless hyperspectral image compression using intraband and interband predictors. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communications and Informatics, Delhi, India, 24–27 September 2014; pp. 332–337. [Google Scholar]

- Baizert, P.; Pickering, M.; Ryan, M. Compression of hyperspectral data by spatial/spectral discrete cosine transform. In Proceedings of the Scanning the Present and Resolving the Future. Proceedings. IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 9–13 July 2001; Volume 4, pp. 1859–1861. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, J.J.; Chen, H.H.; Wei, W.Y. Adaptive golomb code for joint geometrically distributed data and its application in image coding. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2012, 23, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, V.; Rani, J.S. An on-board satellite multispectral and hyperspectral compressor (MHyC): An efficient architecture of a simple lossless algorithm. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2025, 72, 2167–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Pan, W.D.; Shen, H. Universal golomb—Rice coding parameter estimation using deep belief networks for hyperspectral image compression. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2018, 11, 3830–3840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CCSDS 123.0.B-2; Low-Complexity Lossless and Near-Lossless Multispectral and Hyperspectral Image Compression. Consultative Committee for Space Data Systems: Hamburg, Germany, 2019.

- Altamimi, A.; Ben Youssef, B. Lossless and Near-Lossless Compression Algorithms for Remotely Sensed Hyperspectral Images. Entropy 2024, 26, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Memon, N. Context-based, adaptive, lossless image coding. IEEE Trans. Commun. 1997, 45, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witten, I.H.; Neal, R.M.; Cleary, J.G. Arithmetic coding for data compression. Commun. Acm 1987, 30, 520–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.N.N. Range encoding: An algorithm for removing redundancy from a digitised message. In Proceedings of the Proc. Institution of Electronic and Radio Engineers International Conference on Video and Data Recording, Southampton, UK, 24–27 July 1979; p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Mielikainen, J. Lossless compression of hyperspectral images using lookup tables. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2006, 13, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielikainen, J.; Toivanen, P. Optimal granule ordering for lossless compression of ultraspectral sounder data. In Proceedings of the Satellite Data Compression, Communication, and Processing IV, San Diego, CA, USA, 5 September 2008; Volume 7084, p. 708404. [Google Scholar]

- Mielikainen, J.; Toivanen, P. Lossless Compression of Ultraspectral Sounder Data Using Linear Prediction With Constant Coefficients. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2009, 6, 495–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielikainen, J.; Toivanen, P. Clustered DPCM for the lossless compression of hyperspectral images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2003, 41, 2943–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielikainen, J.; Huang, B. Lossless Compression of Hyperspectral Images Using Clustered Linear Prediction with Adaptive Prediction Length. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2012, 9, 1118–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda, J.; Tahboub, K.; Gadgil, N.J.; Delp, E.J. The use of asymmetric numeral systems as an accurate replacement for Huffman coding. In Proceedings of the Picture Coding Symposium, Cairns, QLD, Australia, 31 May–3 June 2015; pp. 65–69. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, T.; Sutter, G.; De Vergara, J.E.L. LOCO-ANS: An Optimization of JPEG-LS Using an Efficient and Low-Complexity Coder Based on ANS. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 106606–106626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, Y. A lossless compression of remote sensing images based on ANS entropy coding algorithm. In Proceedings of the MIPPR Remote Sensing Image Processing, Geographic Information Systems, and Other Applications, Wuhan, China, 7 March 2024; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2024; Volume 13088, pp. 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Wu, J.; Jiao, L.; Shi, G. Lossy-to-Lossless Hyperspectral Image Compression Based on Multiplierless Reversible Integer TDLT/KLT. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2009, 6, 587–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penna, B.; Tillo, T.; Magli, E.; Olmo, G. Embedded lossy to lossless compression of hyperspectral images using JPEG 2000. In Proceedings of the Proceedings. IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 29 July 2005; Volume 1, p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Can, E.; Karaca, A.C.; Danışman, M.; Urhan, O.; Güllü, M.K. Compression of hyperspectral images using luminance transform and 3D-DCT. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Valencia, Spain, 22–27 July 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 5073–5076. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X.; Guo, L.; Liu, Z. Lossless Compression of Hyperspectral Imagery Using Integer Principal Component Transform and 3-D Tarp Coder. In Proceedings of the Eighth ACIS International Conference on Software Engineering, Artificial Intelligence, Networking, and Parallel/Distributed Computing, Qingdao, China, 30 July–1 August 2007; Volume 1, pp. 553–558. [Google Scholar]

- Galli, L.; Salzo, S. Lossless hyperspectral compression using KLT. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Anchorage, AK, USA, 20–24 September 2004; Volume 1, p. 316. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X.; Guo, L.; Liu, Z. Reversible Integer Principal Component Transform for Hyperspectral Imagery Lossless Compression. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Control and Automation, Guangzhou, China, 30 May–1 June 2007; pp. 2968–2972. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X.; Pearlman, W.A. Three-dimensional wavelet-based compression of hyperspectral images. In Hyperspectral Data Compression; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; Chapter 10; pp. 273–308. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Fowler, J.E.; Liu, G. Lossy-to-Lossless Compression of Hyperspectral Imagery Using Three-Dimensional TCE and an Integer KLT. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2008, 5, 814–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.j.; Dill, J. Lossless to Lossy Dual-Tree BEZW Compression for Hyperspectral Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2014, 52, 5765–5770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Xiao-ling, Z.; Lan-sun, S.; Yan, C. Hyperspectral image lossless compression using wavelet transforms and trellis coded quantization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Communications and Information Technology, Beijing, China, 12–14 October 2005; Volume 2, pp. 1452–1455. [Google Scholar]

- Calderbank, A.R.; Daubechies, I.; Sweldens, W.; Yeo, B.L. Lossless image compression using integer to integer wavelet transforms. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Image Processing, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 26–29 October 1997; Volume 1, pp. 596–599. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, M.; Kossentni, F. Reversible integer-to-integer wavelet transforms for image compression: Performance evaluation and analysis. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2000, 9, 1010–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Fang, J.; Han, C. The selection of reversible integer-to-integer wavelet transforms for dem multi-scale representation and progressive compression. In Proceedings of the International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Beijing, China, 3–11 July 2008; Volume 37. [Google Scholar]

- Le Gall, D.; Tabatabai, A. Sub-band coding of digital images using symmetric short kernel filters and arithmetic coding techniques. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, New York, NY, USA, 11–14 April 1988; Volume 2, pp. 761–764. [Google Scholar]

- Zandi, A.; Allen, J.D.; Schwartz, E.L.; Boliek, M. CREW: Compression with reversible embedded wavelets. In Proceedings of the Proceedings DCC Data Compression Conference, Snowbird, UT, USA, 28–30 March 1995; pp. 212–221. [Google Scholar]

- Said, A.; Pearlman, W.A. An image multiresolution representation for lossless and lossy compression. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 1996, 5, 1303–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strang, G.; Nguyen, T. Wavelets and Filter Banks; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, F.; Bilgin, A.; Sementilli, P.; Marcelling, M. Lossy and lossless image compression using reversible integer wavelet transforms. In Proceedings of the Proceedings International Conference on Image Processing, Chicago, IL, USA, 7 October 1998; Volume 3, pp. 876–880. [Google Scholar]

- Gormish, M.J.; Schwartz, E.L.; Keith, A.F.; Boliek, M.P.; Zandi, A. Lossless and nearly lossless compression for high-quality images. In Proceedings of the Very High Resolution and Quality Imaging II, San Jose, CA, USA, 4 April 1997; Volume 3025, pp. 62–70. [Google Scholar]

- Calderbank, A.R.; Daubechies, I.; Sweldens, W.; Yeo, B.L. Wavelet transforms that map integers to integers. Appl. Comput. Harmon. Anal. 1998, 5, 332–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.D.; Kossentini, F. Low-complexity reversible integer-to-integer wavelet transforms for image coding. In Proceedings of the IEEE Pacific Rim Conference on Communications, Computers and Signal Processing, Victoria, BC, Canada, 22–24 August 1999; pp. 177–180. [Google Scholar]

- ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 29/WG 1 N1015; Report on Core Experiment CodEff4: Performance Evaluation of Several Rerversible Integer-to-Integer Wavelet Transforms in the JPEG-2000 Verification Model (Version 2.1). ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998.

- Antonini, M.; Barlaud, M.; Mathieu, P.; Daubechies, I. Image coding using wavelet transform. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 1992, 1, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Töreyin, B.U.; Yilmaz, O.; Mert, Y.M. Evaluation of on-board integer wavelet transform based spectral decorrelation schemes for lossless compression of hyperspectral images. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Hyperspectral Image and Signal Processing: Evolution in Remote Sensing, Lausanne, Switzerland, 24–27 June 2014; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Töreyın, B.U.; Yilmaz, O.; Mert, Y.M.; Türk, F. Lossless hyperspectral image compression using wavelet transform based spectral decorrelation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Recent Advances in Space Technologies, Istanbul, Turkey, 16–19 June 2015; pp. 251–254. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y.; Liu, G. Hyperspectral Image Lossless Compression Using the 3D Set Partitioned Embedded Zero Block Coding Alogrithm. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Science and Software Engineering, Wuhan, China, 12–14 December 2008; Volume 2, pp. 955–958. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y.; Liu, G. Hyperspectral image lossy-to-lossless compression using the 3D Embedded Zeroblock Coding alogrithm. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Earth Observation and Remote Sensing Applications, Beijing, China, 30 June–2 July 2008; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y.; Liu, G. Lossy-to-lossless compression of hyperspectral image using the improved AT-3D SPIHT algorithm. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Science and Software Engineering, Wuhan, China, 12–14 December 2008; Volume 2, pp. 963–966. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Rucker, J.T.; Fowler, J.E. Three-dimensional tarp coding for the compression of hyperspectral images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2004, 1, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moazami-Goudarzi, M.; Moradi, M.H.; Abbasabadi, S. High performance method for electrocardiogram compression using two dimensional multiwavelet transform. In Proceedings of the IEEE Workshop on Multimedia Signal Processing, Shanghai, China, 30 October–2 November 2005; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, B.; Sriraja, Y.; Huang, H.L.; Goldberg, M. Lossless multiwavelet compression of ultraspectral sounder data. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 29 July 2006; pp. 3541–3544. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, K.W.; Cheung, C.H.; Po, L.M. A novel multiwavelet-based integer transform for lossless image coding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings International Conference on Image Processing, Kobe, Japan, 24–28 October 1999; Volume 1, pp. 444–447. [Google Scholar]

- Amrani, N.; Serra-Sagristà, J.; Laparra, V.; Marcellin, M.W.; Malo, J. Regression wavelet analysis for lossless coding of remotesensing data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2016, 54, 5616–5627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Cortés, S.; Amrani, N.; Serra-Sagristà, J. Low complexity regression wavelet analysis variants for hyperspectral data lossless compression. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2018, 39, 1971–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Cortés, S.; Amrani, N.; Hernández-Cabronero, M.; Serra-Sagristà, J. Progressive lossy-to-lossless coding of hyperspectral images through regression wavelet analysis. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2018, 39, 2001–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, S. 3D-listless block cube set-partitioning coding for resource constraint hyperspectral image sensors. Signal Image Video Process. 2024, 18, 3163–3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 15444-2; Information Technology—JPEG 2000 Image Coding System—Part 2: Extensions. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000.

- Rucker, J.T.; Fowler, J.E.; Younan, N.H. JPEG2000 coding strategies for hyperspectral data. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 29 July 2005; Volume 1, p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Schelkens, P.; Munteanu, A.; Tzannes, A.; Brislawn, C. JPEG2000. Part 10. Volumetric data encoding. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems, Kos, Greece, 21–24 May 2006; pp. 4–3877. [Google Scholar]

- Skog, K.; Kohout, T.; Kašpárek, T.; Penttilä, A.; Wolfmayr, M.; Praks, J. Lossless hyperspectral image compression in comet interceptor and hera missions with restricted bandwith. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Fowler, J.E.; Younan, N.H.; Liu, G. Evaluation of JP3D for lossy and lossless compression of hyperspectral imagery. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Cape Town, South Africa, 12–17 July 2009; Volume 4, pp. 474–477. [Google Scholar]

- ISO/IEC 15948; Information Technology—Computer Graphics and Image Processing—Portable Network Graphics (PNG): Functional specification. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004.

- ISO/IEC 14495-1; Information Technology—Lossless and Near-Lossless Compression of Continuous-Tone Still Images: Baseline and Extensions. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1994.

- McNeely, J.; Geiger, G. K-Means Based Spatial Aggregation for Hyperspectral Compression. In Proceedings of the Data Compression Conference, Snowbird, UT, USA, 26–28 March 2014; p. 416. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, S.; Rodriguez, L. Fast piecewise linear predictors for lossless compression of hyperspectral imagery. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Anchorage, AK, USA, 20–24 September 2004; Volume 1, p. 312. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, L.; He, M.; Dai, Y. Lossless Compression of Hyperspectral Images Based on 3D Context Prediction. In Proceedings of the IEEE 3rd Conference on Industrial Electronics and Applications, Singapore, 3–5 June 2008; pp. 1845–1848. [Google Scholar]

- Serra-Sagristà, J.; García-Vílchez, F.; Minguillón, J.; Megías, D.; Huang, B.; Ahuja, A. Wavelet lossless compression of ultraspectral sounder data. In Proceedings of the Proceedings. IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 29 July 2005; Volume 1, p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Mielikainen, J.; Kaarna, A. Improved back end for integer PCA and wavelet transforms for lossless compression of multispectral images. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Quebec City, QC, Canada, 11–15 August 2002; Volume 2, pp. 257–260. [Google Scholar]

- Motta, G.; Rizzo, F.; Storer, J. Partitioned vector quantization: Application to lossless compression of hyperspectral images. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, Baltimore, MD, USA, 6–9 July 2003; Volume 3, p. 241. [Google Scholar]

- Linde, Y.; Buzo, A.; Gray, R. An Algorithm for Vector Quantizer Design. IEEE Trans. Commun. 1980, 28, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M.; Arnold, J. The lossless compression of AVIRIS images by vector quantization. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1997, 35, 546–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Gersho, A. Feature predictive vector quantization of multispectral images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1992, 30, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Ahuja, A.; Huang, H.L. Fast precomputed VQ with optimal bit allocation for lossless compression of ultraspectral sounder data. In Proceedings of the Data Compression Conference, Snowbird, UT, USA, 29–31 March 2005; pp. 408–417. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, B. Discrete optimization via marginal analysis. Manag. Sci. 1966, 13, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.; Gray, R. Image compression using non-adaptive spatial vector quantization. In Proceedings of the Asilomar Conference on Circuits Systems and Computers, Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 7–10 November 1982; pp. 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ramamurthi, B.; Gersho, A. Image vector quantization with a perceptually-based cell classifier. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, San Diego, CA, USA, 19–21 March 1984; Volume 9, pp. 698–701. [Google Scholar]

- Mielikäinen, J.; Toivanen, P. Improved vector quantization for lossless compression of AVIRIS images. In Proceedings of the European Signal Processing Conference, Toulouse, France, 3–6 September 2002; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Blanes, I.; Serra-Sagrist, J. Clustered Reversible-KLT for Progressive Lossy-to-Lossless 3d Image Coding. In Proceedings of the Data Compression Conference, Snowbird, UT, USA, 16–18 March 2009; pp. 233–242. [Google Scholar]

- Le, N.T.; Bui, C.V. Optimized multispectral satellite image compression using wavelet transforms. In Proceedings of the Advances in Data Science and Optimization of Complex Systems: Proceedings of the International Conference on Applied Mathematics and Computer Science–ICAMCS 2024; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; Volume 2, p. 110. [Google Scholar]

- Ahanonu, E.; Marcellin, M.; Bilgin, A. Clustering regression wavelet analysis for lossless compression of hyperspectral imagery. In Proceedings of the 2019 Data Compression Conference (DCC), Snowbird, UT, USA, 26–29 March 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Karaca, A.C.; Güllü, M.K. Superpixel Based Recursive Least-squares Method for Lossless Compression of Hyperspectral Images. Multidimens. Syst. Signal Process. 2019, 30, 903–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Hu, H. Lossless Compression for Hyperspectral Images Using Cascaded Prediction. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Communication, Image and Signal Processing, Chengdu, China, 17–19 November 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 265–269. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, B.; Sriraja, Y. Lossless compression of hyperspectral imagery via lookup tables with predictor selection. In Proceedings of the Image and Signal Processing for Remote Sensing XII. International Society for Optics and Photonics, Stockholm, Sweden, 29 September 2006; Volume 6365, p. 63650L. [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo, D.; Ruedin, A. Lossless compression of hyperspectral images: Look-up tables with varying degrees of confidence. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, Dallas, TX, USA, 14–19 March 2010; pp. 1314–1317. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Z.C.; Zhang, X.L. Lossless compression of hyperspectral imasges using improved Locally Averaged Interband Scaling Lookup Tables. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Wavelet Analysis and Pattern Recognition, Guilin, China, 10–13 July 2011; pp. 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Aiazzi, B.; Baronti, S.; Alparone, L. Lossless Compression of Hyperspectral Imagery Via Lookup Tables and Classified Linear Spectral Prediction. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Boston, MA, USA, 7–11 July 2008; Volume 2, pp. 978–981. [Google Scholar]

- Aiazzi, B.; Baronti, S.; Alparone, L. Lossless Compression of Hyperspectral Images Using Multiband Lookup Tables. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2009, 16, 481–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielikainen, J.; Toivanen, P. Lossless Compression of Hyperspectral Images Using a Quantized Index to Lookup Tables. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2008, 5, 474–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiely, A.B.; Klimesh, M.A. Exploiting Calibration-Induced Artifacts in Lossless Compression of Hyperspectral Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2009, 47, 2672–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, M.; Seroussi, G.; Sapiro, G. LOCO-I: A low complexity, context-based, lossless image compression algorithm. In Proceedings of the Data Compression Conference, Snowbird, UT, USA, 31 March–3 April 1996; pp. 140–149. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger, M.; Seroussi, G.; Sapiro, G. The LOCO-I lossless image compression algorithm: Principles and standardization into JPEG-LS. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2000, 9, 1309–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, V.; Rani, J.S. An efficient fpga implementation of a simple lossless algorithm (SLA) for on-board satellite hyperspectral data compression. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Circuits and Systems, Singapore, 19–22 May 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, V.; Rani, J.S. A simple lossless algorithm for on-board satellite hyperspectral data compression. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Guo, K. Lossless compression of hyperspectral images using interband gradient adjusted prediction. In Proceedings of the IEEE 4th International Conference on Software Engineering and Service Science, Beijing, China, 23–25 May 2013; pp. 724–727. [Google Scholar]

- Altamimi, A.; Ben Youssef, B. Leveraging seed generation for efficient hardware acceleration of lossless compression of remotely sensed hyperspectral images. Electronics 2024, 13, 2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 10918-1; Information Technology—Digital Compression and Coding of Continuous-Tone Still Images: Requirements and Guidelines. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1994.

- Slyz, M.; Zhang, L. A block-based inter-band lossless hyperspectral image compressor. In Proceedings of the Data Compression Conference, Snowbird, UT, USA, 29–31 March 2005; pp. 427–436. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Memon, N. Context-based lossless interband compression-extending CALIC. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2000, 9, 994–1001. [Google Scholar]

- Karaca, A.C.; Gullu, M.K. Lossless compression of ultraspectral sounder data using recursive least squares. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Recent Advances in Space Technologies, Istanbul, Turkey, 19–22 June 2017; pp. 109–112. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.C.; Hwang, Y.T. An Efficient Lossless Compression Scheme for Hyperspectral Images Using Two-Stage Prediction. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2010, 7, 558–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, J.; Potvin, S.; Deschenes, J.D.; Genest, J. Lossless compression of hyperspectral data obtained from Fourier-transform infrared imaging spectrometers. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Hyperspectral Image and Signal Processing: Evolution in Remote Sensing, Reykjavik, Iceland, 14–16 June 2010; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Klimesh, M. Low-Complexity Lossless Compression of Hyperspectral Imagery via Adaptive Filtering; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 2005.

- Fernandez i Ubiergo, G. Lossless region-based multispectral image compression. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Image Processing and Its Applications, Lyon, France, 9–11 January 1997; Volume 1, pp. 64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. Least squares approach for predictive coding of 3-D images. In Proceedings of the 3rd IEEE International Conference on Image Processing, Lausanne, Switzerland, 19 September 1996; Volume 2, pp. 875–878. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Shi, Z.; Li, D. Lossless Compression of Hyperspectral Image Based on 3DLMS Prediction. In Proceedings of the International Congress on Image and Signal Processing, Tianjin, China, 17–19 October 2009; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Klimesh, M. Low-complexity adaptive lossless compression of hyperspectral imagery. In Proceedings of the Satellite Data Compression, Communications, and Archiving II. International Society for Optics and Photonics, San Diego, CA, USA, 1 September 2006; Volume 6300, p. 63000N. [Google Scholar]

- Aiazzi, B.; Alba, P.; Alparone, L.; Baronti, S. Lossless compression of multi/hyper-spectral imagery based on a 3-D fuzzy prediction. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1999, 37, 2287–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiazzi, B.; Alparone, L.; Baronti, S. Quality Issues for Compression of Hyperspectral Imagery Through Spectrally Adaptive DPCM. In Satellite Data Compression; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 115–147. [Google Scholar]

- Aiazzi, B.; Baronti, S.; Lastri, C.; Santurri, L.; Alparone, L. Low-complexity lossless/near-lossless compression of hyperspectral imagery through classified linear spectral prediction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings. IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 29 July 2005; Volume 1, pp. 132–135. [Google Scholar]

- Aiazzi, B.; Alparone, L.; Baronti, S.; Lastri, C. Crisp and Fuzzy Adaptive Spectral Predictions for Lossless and Near-Lossless Compression of Hyperspectral Imagery. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2007, 4, 532–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, F.; Carpentieri, B.; Motta, G.; Storer, J. Low-complexity lossless compression of hyperspectral imagery via linear prediction. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2005, 12, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; David Pan, W. Predictive lossless compression of regions of interest in hyperspectral image via Maximum Correntropy Criterion based Least Mean Square learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Image Processing, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 25–28 September 2016; pp. 2182–2186. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, F.; Guo, S. Lossless compression of hyperspectral images using conventional recursive least-squares predictor with adaptive prediction bands. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 2016, 10, 015010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhu, F. Novel lossless compression method for hyperspectral images based on variable forgetting factor recursive least squares. J. Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 20, 663–674. [Google Scholar]

- Karaca, A.C.; Güllü, M.K. Lossless hyperspectral image compression using bimodal conventional recursive least-squares. Remote Sens. Lett. 2018, 9, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhou, L.; Deng, C.; An, J. Lossless compression of hyperspectral imagery using a fast adaptive-length-prediction RLS filter. Remote Sens. Lett. 2019, 10, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, C.; Zhang, R.; Peng, T. Lossless Compression of Hyperspectral Images Based on Searching Optimal Multibands for Prediction. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2009, 6, 339–343. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, G. A Novel Lossless Compression for Hyperspectral Images by Adaptive Classified Arithmetic Coding in Wavelet Domain. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Image Processing, Atlanta, GA, USA, 8–11 October 2006; pp. 2269–2272. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, G. A Novel Lossless Compression for Hyperspectral Images by Context-Based Adaptive Classified Arithmetic Coding in Wavelet Domain. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2007, 4, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Jiang, Z.; Pan, W.D. Efficient lossless compression of multitemporal hyperspectral image data. J. Imaging 2018, 4, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Guo, K. Lossless compression of hyperspectral images using three-stage prediction. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Software Engineering and Service Science, Beijing, China, 23–25 May 2013; pp. 1029–1032. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, S.K.; Adjeroh, D.A. Edge-Based Prediction for Lossless Compression of Hyperspectral Images. In Proceedings of the Data Compression Conference, Snowbird, UT, USA, 27–29 March 2007; pp. 153–162. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, G.; Fan, B.; Li, H. Onboard Lossless Compression of Hyperspectral Imagery Based on Hybrid Prediction. In Proceedings of the Asia-Pacific Conference on Information Processing, Shenzhen, China, 18–19 July 2009; Volume 2, pp. 164–167. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, G. An Efficient Reordering Prediction-Based Lossless Compression Algorithm for Hyperspectral Images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2007, 4, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Babacan, S.D.; Sayood, K. Lossless Hyperspectral-Image Compression Using Context-Based Conditional Average. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2007, 45, 4187–4193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.C.; Hwang, Y.T. Lossless Compression of Hyperspectral Images Using Adaptive Prediction and Backward Search Schemes. J. Inf. Sci. Eng. 2011, 27, 419–435. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.-h.; Shi, Z.-l.; Ma, L. Lossless compression of hyperspectral image based on spatial-spectral hybrid prediction. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Signal Processing, Beijing, China, 26–29 October 2008; pp. 993–997. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, Y.; Zhang, X.-l.; Shen, L.-s. Lossless compression of hyperspectral imagery through 2D/3D hybrid prediction. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Communications and Information Technology, Beijing, China, 12–14 October 2005; Volume 2, pp. 1456–1459. [Google Scholar]

- Magli, E. Multiband Lossless Compression of Hyperspectral Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2009, 47, 1168–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Cabronero, M.; Kiely, A.B.; Klimesh, M.; Blanes, I.; Ligo, J.; Magli, E.; Serra-Sagrista, J. The CCSDS 123.0-B-2 “Low-Complexity Lossless and Near-Lossless Multispectral and Hyperspectral Image Compression” Standard: A comprehensive review. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2021, 9, 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorhaug, D.; Boyle, S.; Orlandić, M. High-level CCSDS 123.0-B-2 hyperspectral image compressor verification model. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Hyperspectral Imaging and Signal Processing: Evolution in Remote Sensing, Helsinki, Finland, 9–11 December 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Nonnis, A.; Grangetto, M.; Magli, E.; Olmo, G.; Barni, M. Improved low-complexity intraband lossless compression of hyperspectral images by means of Slepian-Wolf coding. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Image Processing 2005, Genova, Italy, 14 September 2005; Volume 1, p. I–829. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Y.; Yan, X.; Wu, J. Hyperspectral image lossless compression using DSC and 2-D CALIC. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer and Communication Technologies in Agriculture Engineering, Chengdu, China, 12–13 June 2010; Volume 3, pp. 460–463. [Google Scholar]

- Slepian, D.; Wolf, J. Noiseless coding of correlated information sources. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1973, 19, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magli, E.; Olmo, G.; Quacchio, E. Optimized onboard lossless and near-lossless compression of hyperspectral data using CALIC. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2004, 1, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afjal, M.I.; Mamun, M.A.; Uddin, M.P. Weighted-Correlation based Band Reordering Heuristics for Lossless Compression of Remote Sensing Hyperspectral Sounder Data. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advancement in Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Gazipur, Bangladesh, 22–24 November 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Afjal, M.I.; Uddin, P.; Mamun, A.; Marjan, A. An efficient lossless compression technique for remote sensing images using segmentation based band reordering heuristics. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2021, 42, 756–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonds, J. Optimum branchings. Math. Decis. Sci. Part 1968, 1, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, S. Band ordering in lossless compression of multispectral images. IEEE Trans. Comput. 1997, 46, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubasova, O.; Toivanen, P. Lossless compression methods for hyperspectral images. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Cambridge, UK, 26 August 2004; Volume 2, pp. 803–806. [Google Scholar]

- Toivanen, P.; Kubasova, O.; Mielikainen, J. Correlation-based band-ordering heuristic for lossless compression of hyperspectral sounder data. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2005, 2, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prim, R.C. Shortest connection networks and some generalizations. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1957, 36, 1389–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Wang, L.; Li, T.; Xie, J. A Method of Reordering Lossless Compression of Hyperspectral Images. Isprs Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, 10, 821–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afjal, M.I.; Al Mamun, M.; Uddin, M.P. Band reordering heuristics for lossless satellite image compression with 3D-CALIC and CCSDS. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2019, 59, 514–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, T.; Fu, Y.; Huang, H. Hyperreconnet: Joint coded aperture optimization and image reconstruction for compressive hyperspectral imaging. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2018, 28, 2257–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haut, J.M.; Gallardo, J.A.; Paoletti, M.E.; Cavallaro, G.; Plaza, J.; Plaza, A.; Riedel, M. Cloud deep networks for hyperspectral image analysis. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2019, 57, 9832–9848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, I.; Kim, M.; Gutierrez, D.; Jeon, D.; Nam, G. High-quality hyperspectral reconstruction using a spectral prior. Acm Trans. Graph. 2017, 36, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrin, A.; Haque, M.R.; Al Mamun, M. Enhancing hyperspectral image compression through stacked autoencoder approach. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Information & Communication Technology, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2–4 May 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1372–1377. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Liu, Z. Multispectral transforms using convolution neural networks for remote sensing multispectral image compression. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, J.; Gross, W.; Michel, A.; Weinmann, M.; Kuester, J. Transformer-based lossy hyperspectral satellite data compression. In Proceedings of the Earth Resources and Environmental Remote Sensing/GIS Applications XVI, Madrid, Spain, 28 October 2025; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2025; Volume 13671, pp. 217–226. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Song, C.; Zhang, P. Hyperspectral image compression sensing network with CNN–Transformer mixture architectures. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 5506305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, M.H.P.; Rasti, B.; Demir, B. HyCoT: A Transformer-Based Autoencoder for Hyperspectral Image Compression. In Proceedings of the 2024 14th Workshop on Hyperspectral Imaging and Signal Processing: Evolution in Remote Sensing (WHISPERS), Helsinki, Finland, 9–11 December 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, C.; Cen, Y.; Zhang, L. Learning-based hyperspectral imagery compression through generative neural networks. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, W.; Peng, Q.; Tu, L. Spectral constrained generative adversarial network for hyperspectral compression. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 23372–23386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Chong, Y.; Pan, S. Hyperspectral image compression via cross-channel contrastive learning. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5513918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byju, A.P.; Fuchs, M.H.P.; Walda, A.; Demir, B. Generative Adversarial Networks for Spatio-Spectral Compression of Hyperspectral Images. In Proceedings of the 2024 14th Workshop on Hyperspectral Imaging and Signal Processing: Evolution in Remote Sensing (WHISPERS), Helsinki, Finland, 9–11 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Qu, L. Bi-residual compression network with conditional diffusion model for hyperspectral image compression. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5521015. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X.; Gu, E.; Zhang, Y.; Li, A. Probability prediction network with checkerboard prior for lossless remote sensing image compression. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 17971–17982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, E.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Jiang, X. Lossless compression framework using lossy prior for high-resolution remote sensing images. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 8590–8601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Wu, J.; Zhao, S.; Wang, L.; Xu, T. Lossless compression for hyperspectral image using deep recurrent neural networks. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 2019, 10, 2619–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valsesia, D.; Bianchi, T.; Magli, E. Hybrid recurrent-attentive neural network for onboard predictive hyperspectral image compression. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Athens, Greece, 7–12 July 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 7898–7902. [Google Scholar]

- Valsesia, D.; Bianchi, T.; Magli, E. Onboard deep lossless and near-lossless predictive coding of hyperspectral images with line-based attention. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5532714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Yan, J.; Zheng, Z. Transformer-based lossless compression of aurora spectral images: A spatial-temporal-spectral joint approach. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Signal Processing, Suzhou, China, 28–31 October 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 418–423. [Google Scholar]

- Valsesia, D.; Bianchi, T.; Magli, E. Onboard hyperspectral image compression with deep line-based predictove architectures. In Proceedings of the 9th International Workshop on On-Board Payload Data Compression, Gran Canaria, Spain, 2–4 October 2024; ESA: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.; Pan, W.D.; Shen, H. LSTM Based Adaptive Filtering for Reduced Prediction Errors of Hyperspectral Images. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Wireless for Space and Extreme Environments, Huntsville, AL, USA, 11–13 December 2018; pp. 158–162. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.; Pan, W.D.; Shen, H. Spatially and Spectrally Concatenated Neural Networks for Efficient Lossless Compression of Hyperspectral Imagery. J. Imaging 2020, 6, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuradha, D.; Sekhar, G.C.; Mishra, A.; Thapar, P.; Baker El-Ebiary, Y.A.; Syamala, M. Efficient compression for remote sensing: Multispectral transform and deep recurrent neural networks for lossless hyper-spectral imagine. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2024, 15, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graña, M.; Veganzons, M.A.; Ayerdi, B. Hyperspectral Remote Sensing Scenes. Available online: https://www.ehu.eus/ccwintco/index.php/Hyperspectral_Remote_Sensing_Scenes (accessed on 3 December 2025).

| x | Horizontal position of the current compressing pixel |

| y | Vertical position of the current compressing pixel |

| z | Band index of the current compressing pixel |

| X | Height of image |

| Y | Width of image |

| Z | Number of bands of image |

| The input image | |

| Pixel value of image at column row band | |

| Predicted pixel value of image at column row band | |

| Mean of | |

| p | Pixel value of |

| Predicted pixel value of | |

| Pixel value of | |

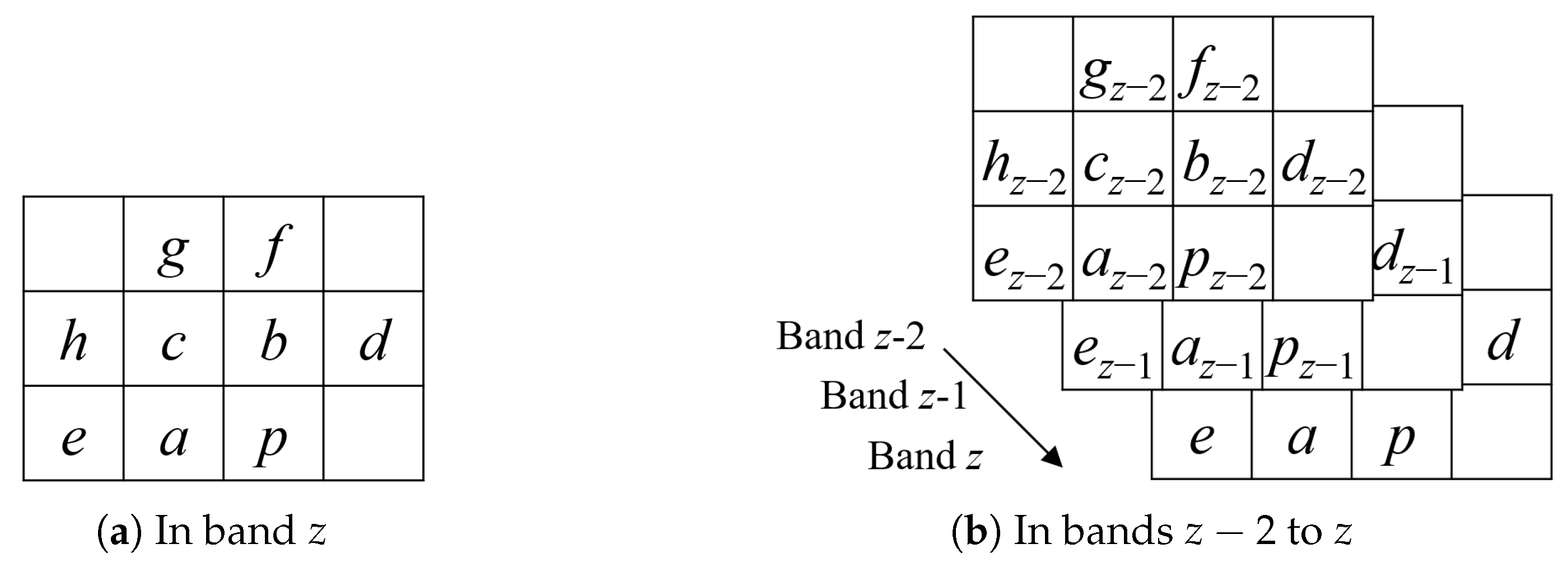

| Neighbours of in band z | |

| Neighbours of in band | |

| A vector storing , i.e., | |

| Difference image between the current band and previous band | |

| Pixel value of difference image at band z position a |

| Method | Underlying Principle | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raster Scan | Sequentially processes pixels from left-to-right, top-to-bottom, band-by-band | Simple, widely used, low complexity | May not exploit local spatial correlation optimally |

| Hilbert Scan | Space-filling curve that improves locality of neighboring pixels | Enhances neighbor correlation, potentially better compression | Computationally more complex; sometimes less effective than Raster |

| Stripe-based Scan | Processes data in stripes, as used in JPEG2000 | Balances complexity and efficiency, good for spatial correlation | Slightly more complex than Raster |

| Double Snake Scan | Alternating stripe scanning to minimize distance between successive pixels | Reduces prediction distance, improves correlation | More complex implementation |

| Block Scan | Divides image into blocks and applies scanning order within each block | Facilitates local processing, parallelizable | May introduce block boundary artifacts if not handled carefully |

| Run-Length Coding | Encodes consecutive repeating symbols as run-length pairs | Excellent for sparse/ highly repetitive data | Inefficient for highly variable data |

| Wavelet Coding (EZW, SPIHT, SPECK) | Encodes wavelet coefficients in hierarchical or sub-band order | Multi-resolution representation, progressive transmission possible, good compression ratio | Higher computational cost; needs careful bit-plane ordering for lossless mode |

| EZW | Encodes zerotrees of wavelet coefficients | Compact representation of insignificance | Requires multiple outputs for some cases |

| SPIHT | Improves EZW by separating parent/child significance | More efficient than EZW, fewer output symbols | 3D extension increases complexity |

| SPECK | Groups coefficients by sub-band and encodes significance | Efficient sub-band exploitation, memory-efficient variants exist (ZM-SPECK) | May be less efficient when sub-band statistics vary significantly |

| Straight Coding | Directly encodes raw pixel values | Extremely simple, useful for initialization | No compression efficiency gain |

| Huffman Coding | Optimal prefix code based on symbol frequency | Simple, well-studied, fast decoding | Requires frequency table; adaptive mode incurs overhead |

| Golomb Coding | Prefix + suffix coding optimal for Laplacian distributions | Adaptive, near-optimal for prediction residuals | Requires parameter M tuning; mapping required for non-negative integers |

| Golomb-Rice Coding | Restricts M to powers of 2 for efficiency | Very fast, hardware-friendly, used in CCSDS-123 | May be slightly less optimal than general Golomb coding |

| Exponential-Golomb Coding | Uses logarithmic prefix + binary suffix | Compact for small values, used in video coding | Slightly higher complexity than Rice |

| Context-based Extensions | Adjusts coding tables/ parameters per pixel context | Improves coding efficiency by modeling local statistics | Increases encoder complexity and memory usage |

| Arithmetic Coding | Encodes data into a fractional interval based on probabilities | Achieves near-entropy compression, highly efficient | Computationally expensive, requires renormalization |

| Range Coding | Integer-based version of AC | Similar compression to AC, avoids patent issues | Computationally expensive |

| Asymmetric Numeral Systems | Generalizes numeral systems for non-uniform distributions | Comparable ratio to AC, faster, vectorizable | Produces output in reverse order, higher memory usage |

| Names | Low Pass Filter Coefficients | High Pass Filter Coefficients |

|---|---|---|

| S | ||

| 5/3 [65] | ||

| 2/6 [66] | ||

| SPB [67] | ||

| SPC [67] | ||

| 9/7-M [68] | ||

| (2, 4) [69] | ||

| (6, 2) [69] | ||

| 2/10 [70] | ||

| 5/11-C [71] | ||

| 5/11-A [72] | ||

| 6/14 [73] | ||

| 13/7-T [68] | ||

| 13/7-C [73] | ||

| 9/7-F [74] |

| Method | Underlying Principle | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| KLT + DCT [52] | Performs 1D KLT along spectral dimension followed by 2D DCT in spatial domain | Compact energy representation; enables lossy-to-lossless compression | DCT is suboptimal for strictly lossless compression; eigenvector computation overhead from KLT |

| KLT + DWT [60] | Applies 1D spectral KLT followed by 2D DWT in spatial domain | Strong spectral decorrelation combined with multi-resolution spatial representation; typically better than pure DWT | High computational complexity for eigen-decomposition and multilevel wavelet transform |

| DWT [25] | Applies 3D DWT with improved SPECK | Highly effective for spatial and spectral decorrelation | Filter choice and decomposition levels should be tuned per dataset |

| Wavelet Packet Transform [80] | Decomposes not only the low-frequency sub-band but all sub-bands into further wavelet packets, allowing finer frequency partitioning | Provides more complete decorrelation; improves compression ratio for SPIHT/SPECK | Computationally expensive due to additional decompositions |

| Multiwavelet Transform [81] | Employs multiple pairs of scaling and wavelet functions simultaneously | Better compression than scalar DWT; flexible design space | Complex filter construction and implementation |

| Regression Wavelet Transform [85] | Predicts high-frequency wavelet coefficients using regression models based on low-frequency coefficients at each decomposition level | Significantly reduces redundancy in high-frequency sub-bands; improved coding efficiency over ordinary DWT | Requires storage of regression parameters and prediction residuals; model choice impacts performance |

| Dyadic Wavelet Transform [87] | Restricts scale and translation parameters to dyadic (power-of-two) values, minimizing number of coefficients required to represent signal | Extremely compact representation; low computational complexity; efficient at low bit-rates | Less effective for strictly lossless compression; limited adaptability |

| JPEG2000 (Part II: Extensions) [88] | Extends JPEG2000 to 3D images by allowing arbitrary spectral decorrelation | Internationally standardized; supports up to 16,385 spectral bands; progressive bitplane coding; excellent compression efficiency for noiseless data | High computational complexity; transform-based approach is sensitive to noise and can propagate errors |

| DWT + JPEG-LS [76] | Applies 1D spectral DWT followed by 2D JPEG-LS in spatial domain | Simple to implement; computationally efficient; improved coding efficiency over ordinary JPEG-LS | Compression performance lower than full 3D transform approaches; sensitive to filter and decomposition level selection |

| RWT + JPEG2000 [86] | Applies 1D spectral RWT followed by 2D JPEG2000 in spatial domain | Competitive compression results with reduced complexity compared to KLT-based approaches; benefits from regression decorrelation | Less efficient than KLT+DWT combination; residual coding overhead still present |

| 3D-to-2D + JPEG2000 [98] | Rearranges hyperspectral cube into 2D strip image before standard JPEG2000 coding | Allows direct application of mature 2D coders; improved coding efficiency over per-band compression | Ignores intrinsic 3D correlation structure; performance depends on band ordering; less effective for highly nonlinear spectral correlations |

| DCT + Residual Encoding [35] | Applies lossy 3D DCT to obtain compact representation, then encodes residuals for perfect reconstruction | High energy compaction; tunable trade-off between compression ratio and reconstruction fidelity; outperforms vector quantization in some settings | Requires transmitting DCT coefficients and residuals; careful quantization design critical to avoid file-size overhead |

| Vector Quantization [100] | Divides data into vectors, quantizes them by mapping to nearest codebook entries, and stores indexes plus residuals | Very effective for highly correlated data; parameters can be tuned for target performance | Codebook generation can be computationally expensive; overhead for transmitting codebook; sensitive to training set quality |

| Method | Underlying Principle | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lookup Table [44] | Dynamically builds a lookup table during predicting, mapping pixel values in band to their corresponding values in band z | Requires no side information; simple to implement; efficient when strong spectral correlation exists | Suffers from sparsity as bit depth increases, more outliers; residuals have irregular distribution, reduced coding efficiency |

| Lookup Table with LAIS [118] | Enhances LUT by computing local scaling factors between bands; multiple candidates per index and multi-band prediction ( LUTs) | Improves prediction accuracy for outliers and captures subtle scaling effects between bands | Gains diminish as N and M increase; little improvement when LAIS approaches 1; adds computational overhead |

| Median Edge Detector [121] | Classifies pixels into flat or edge regions based on causal neighborhood and applies simple piecewise predictors | Low complexity; well-suited for natural images | Considers only local context; struggles with highly textured or noisy hyperspectral data |

| Simple Lossless Algorithm [124] | Groups neighbors into spatial and spectral categories and predicts using local sums and differences | Exploits both spatial and spectral correlation simultaneously | Neighborhood grouping must be carefully designed; higher complexity compared to MED |

| Gradient Adjusted Predictor [125] | Classifies pixel into edge or flat categories, and applies weighted prediction rules | High prediction accuracy; robust to edges and local variations | More computationally expensive than MED; requires careful threshold tuning for classification |

| Differential Predictor [91] | Predicts current pixel value from the corresponding pixel in the previous spectral band | Simple and efficient; low computational cost | Limited modeling capacity; poor performance for weak spectral correlation |

| Higher-Order Differential Predictor [31] | Uses multiple previous bands and spatial neighbors to improve prediction accuracy | Captures long-range spectral dependencies; improved compression over simple DP | Increased computational cost and memory usage; requires parameter estimation and storage |

| Linear Predictor [145] | Predicts pixel as a weighted linear combination of previous bands and spatial neighbors, with weights adaptively updated | Accurately models linear inter-band correlation; supports adaptive learning; yields high compression performance | Weight estimation and update add computational complexity; sensitive to initialization and learning rate |

| Band-Adaptive Selection [174] | Selects MED for spatially correlated bands and DP for spectrally correlated bands based on inter-band statistics | Computationally efficient; adaptively chooses best predictor per band | Not suitable for scenes with rapid spatial variability or low band-to-band correlation |

| Block-Adaptive Selection [18] | Divides image into blocks and selects predictor type per block using correlation | Improves local adaptability; boosts compression efficiency on heterogeneous scenes | Requires correlation computation per block; incurs side information overhead |

| Three-Level Cascaded Predictor [113] | Applies a multi-stage prediction: local-mean removal → DP → LP refinement. | Significantly reduces residual energy; exploits spatial and spectral redundancy hierarchically. | Multi-stage approach adds computational cost and memory usage |

| CCSDS-123 [161] | Standardized predictor for spaceborne applications; uses local-mean-removed pixel with LP | High compression efficiency; low complexity | Suboptimal for highly nonlinear or nonstationary spectra; requires careful learning rate tuning |

| M-CALIC [166] | Extends CALIC to hyperspectral data by combining inter-band predictors | State-of-the-art prediction-based compression; excellent performance on diverse image statistics | Computationally expensive; memory-intensive; complex to implement in real-time systems |

| Band Reordering + 3D-CALIC [168] | Reorders bands to maximize spectral similarity before applying 3D-CALIC prediction | Ensures stronger spectral correlation and improves residual compressibility | Requires preprocessing step for band ordering; increases latency and overall complexity |

| Kalman Filtering + 3D-CALIC [160] | Fuses DP with 3D-CALIC using Kalman gain for better prediction | Achieves additional compression gain over 3D-CALIC; theoretically optimal fusion | High computational cost; requires per-pixel covariance estimation and storage |

| Method | Underlying Principle | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autoencoder [177] | Learns a nonlinear mapping to compress input data into a low-dimensional latent representation, then reconstructs it. Residuals must be encoded for lossless reconstruction. | Powerful nonlinear dimensionality reduction; effective feature extraction; flexible architectures. | Requires storage of residuals; training can be computationally expensive. |

| Stacked Autoencoder [179] | Uses multiple autoencoders in sequence to iteratively reduce residual error. | Reduced residuals compared to a single autoencoder | Increased network depth leads to higher computational cost and memory consumption. |

| Transformer-based Autoencoder [181] | Uses self-attention mechanisms to capture long-range dependencies in data. | Better modeling of global correlations; competitive compression fidelity. | High computational complexity; requires large training data. |

| Generative Models [188] | Learns underlying probability distribution of HSI data using generative networks. | Compact representation; superior spectral and perceptual quality. | Training instability; complex architecture; slow sampling. |

| Transform with Subimages [190] | Subsamples input to multiple subimages, compresses one subimage conventionally, and predicts others using learned probability distribution. | Effectively reduces redundancy between subimages; improves coding efficiency by exploiting spectral-spatial priors. | More complex architecture and longer training time. |

| Pixel-wise Prediction [192] | Use neural network for pixel-by-pixel prediction. | High prediction accuracy; good generalization ability. | Sequential nature may limit inference speed; computationally heavy for large scenes. |

| Row-wise Prediction [193] | Predicts entire rows based on previous rows and bands, instead of pixel-by-pixel. | Significantly accelerates prediction; reduces context-switching overhead. | May lose fine local adaptivity compared to pixel-wise prediction. |

| LP with Weight Prediction [197] | Predicts linear predictor weights using neural network to gather both spatial and spectral dependencies. | Adapts well to varying spectral statistics; reduces residual entropy. | Training requires large datasets; may overfit if spectral variability is low. |