Highlights

What are the main findings?

- We propose a novel Multi-Attention Fusion Generative Adversarial Network (MAF-GAN) that integrates oriented convolution, multi-dimensional attention mechanisms, and dynamic feature fusion to significantly enhance the reconstruction of directional structures and fine textures in remote sensing imagery.

- Extensive experiments demonstrate that MAF-GAN achieves state-of-the-art performance on the GF7-SR4×-MSD dataset, with a PSNR of 27.14 dB and SSIM of 0.7206, outperforming existing mainstream models while maintaining a favorable balance between reconstruction quality and inference efficiency.

What are the implication of the main findings?

- The proposed model provides a reliable and efficient technical pathway for generating high-resolution remote sensing images with clearer spatial structures and more natural spectral characteristics, supporting high-precision applications such as urban planning and environmental monitoring.

- The introduced modular design, including oriented convolution, multi-attention fusion, and a composite loss function, offers a flexible and extensible framework that can inspire future research in specialized super-resolution tasks for remote sensing and other geospatial image processing domains.

Abstract

Existing Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) frequently yield remote sensing images with blurred fine details, distorted textures, and compromised spatial structures when applied to super-resolution (SR) tasks, so this study proposes a Multi-Attention Fusion Generative Adversarial Network (MAF-GAN) to address these limitations: the generator of MAF-GAN is built on a U-Net backbone, which incorporates Oriented Convolutions (OrientedConv) to enhance the extraction of directional features and textures, while a novel co-calibration mechanism—incorporating channel, spatial, gating, and spectral attention—is embedded in the encoding path and skip connections, supplemented by an adaptive weighting strategy to enable effective multi-scale feature fusion, and a composite loss function is further designed to integrate adversarial loss, perceptual loss, hybrid pixel loss, total variation loss, and feature consistency loss for optimizing model performance; extensive experiments on the GF7-SR4×-MSD dataset demonstrate that MAF-GAN achieves state-of-the-art performance, delivering a Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) of 27.14 dB, Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) of 0.7206, Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS) of 0.1017, and Spectral Angle Mapper (SAM) of 1.0871, which significantly outperforms mainstream models including SRGAN, ESRGAN, SwinIR, HAT, and ESatSR as well as exceeds traditional interpolation methods (e.g., Bicubic) by a substantial margin, and notably, MAF-GAN maintains an excellent balance between reconstruction quality and inference efficiency to further reinforce its advantages over competing methods; additionally, ablation studies validate the individual contribution of each proposed component to the model’s overall performance, and this method generates super-resolution remote sensing images with more natural visual perception, clearer spatial structures, and superior spectral fidelity, thus offering a reliable technical solution for high-precision remote sensing applications.

1. Introduction

High-resolution (HR) remote sensing imagery, capable of vividly capturing fine details, structural features, and spatial distributions of surface objects, has become an indispensable data source for applications including urban planning, resource surveying, environmental monitoring, disaster assessment, and national defense security [1]. However, the timely acquisition of large volumes of high-quality HR imagery remains constrained by inherent limitations in satellite sensor technology, imaging physics, high operational costs, and atmospheric interference [2]. Against this backdrop, image super-resolution (SR) technology [3] has emerged as a promising computational solution. It aims to reconstruct an HR image from a single low-resolution (LR) input, thereby mitigating hardware-related constraints and demonstrating significant research value and practical application potential [4].

The value of HR remote sensing imagery extends beyond mere visual enhancement; it critically enables advanced analytical tasks. For instance, scene classification models that rely on discriminative spatial patterns [5], object detection frameworks requiring precise geometric boundaries [6], and change detection methods demanding consistent spatial-spectral fidelity [7] all fundamentally depend on high-quality input imagery. Super-resolution technology thus serves not merely as a visual enhancement tool, but as a foundational preprocessing step that amplifies the efficacy and reliability of the entire remote sensing analytical pipeline [8].

The evolution of SR methodology has progressed through several distinct phases. Early approaches primarily relied on interpolation techniques (e.g., bicubic interpolation [9]) or reconstruction-based frameworks [10]. Though conceptually simple, these methods exhibited limited reconstruction capability, often producing overly smooth images with blurred edges and lost fine details [11]. The advent of deep learning [12] brought revolutionary breakthroughs to image SR. The pioneering work of Dong et al. [13] with the Super-Resolution Convolutional Neural Network (SRCNN) established the first end-to-end learning paradigm for mapping LR to HR images. Subsequent developments focused on deepening network architectures, as seen in VDSR [14] and EDSR [15], which significantly improved reconstruction accuracy by expanding receptive fields and enhancing feature representation capacity.

A fundamental limitation of these early deep learning methods was their predominant focus on minimizing pixel-level reconstruction errors (e.g., Mean Squared Error). Consequently, while achieving high Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) [16], the reconstructed images often lacked high-frequency texture details, leading to poor perceptual quality—a phenomenon widely recognized as the “perception-distortion trade-off” [17].

To address this limitation, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [18] were introduced into the SR domain, marking a significant paradigm shift toward perception-driven reconstruction. The seminal work of SRGAN [19] demonstrated that adversarial training, combined with a VGG-based perceptual loss [20], could generate images with significantly enhanced visual realism and texture detail. This foundation was substantially advanced by ESRGAN [21], which incorporated more complex network architectures (Residual-in-Residual Dense Blocks, RRDB) and a relativistic discriminator to produce sharper edges and more detailed textures. Subsequent research has branched along two main directions: perception-driven optimization for real-world scenarios, as exemplified by Real-ESRGAN’s explicit modeling of practical degradations [22], and architectural innovation through the integration of transformer architectures. This architectural pursuit was notably advanced by Liang et al. with SwinIR [23], which effectively restores global structural consistency. More recently, Chen et al. proposed HAT [24], which further enhances the transformer’s capacity through a hybrid attention module, setting a new state-of-the-art on several SR benchmarks. In parallel, to address computational demands for practical deployment, efficient CNN-based architectures remain an active area of exploration. For instance, Wang et al. introduced ESatSR [25], a model specifically designed for remote sensing imagery that leverages a state space model to achieve a favorable balance between reconstruction quality and inference speed.

Despite these impressive achievements in general-purpose SR, their application to remote sensing imagery remains challenging due to the domain-specific characteristics of geospatial data: (1) the high complexity and directional nature of anthropogenic and natural structures [26]; (2) extreme multi-scale texture variations [27]; and (3) the critical importance of spectral fidelity for subsequent analytical tasks [28]. Furthermore, the large scene size and complex global dependencies in remote sensing imagery impose additional demands on computational efficiency and long-range modeling capabilities [29].

Consequently, directly applying general-purpose models like SRGAN and ESRGAN to remote sensing data often leads to suboptimal performance, including structural distortions, false textures, and spectral distortions [30]. These limitations underscore the need for specialized SR approaches that can comprehensively address the unique challenges of remote sensing imagery. While some domain-specific methods have been proposed, such as MBGPIN [31] which incorporates physical constraints for structure preservation, their feature representation mechanisms often lack the adaptability and comprehensiveness needed for diverse remote sensing scenarios. Meanwhile, the proven effectiveness of multi-attention frameworks in other vision tasks [32]—which enable adaptive feature refinement across channel, spatial, and spectral dimensions—suggests a promising yet under-explored direction for remote sensing SR.

To bridge this gap, this paper proposes a Multi-Attention Fusion Generative Adversarial Network (MAF-GAN) specifically designed for remote sensing image super-resolution. The main contributions of this work are threefold: First, we introduce oriented convolution modules into a U-Net-based generator to explicitly model directional structures prevalent in remote sensing scenes. Second, we devise a coordinated multi-attention fusion mechanism operating across channel, spatial, and spectral dimensions within the skip connections for adaptive feature refinement [33]. Third, we propose a dynamic feature fusion strategy employing learnable weights to optimally blend multi-level features from the encoder and decoder paths. Through comprehensive experimentation, we demonstrate that the proposed MAF-GAN achieves state-of-the-art performance, reconstructing images with superior texture clarity, structural fidelity, and spectral integrity.

2. Methods

2.1. Dataset

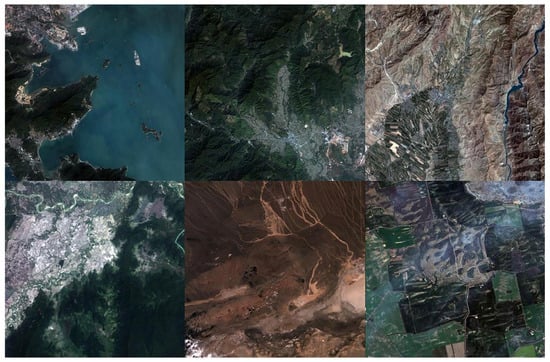

This research introduces the GF7-SR4×-MSD dataset (GaoFen-7 Super-Resolution 4× Multi-Scene Dataset), a specialized benchmark constructed from GaoFen-7 (GF-7) satellite imagery for remote sensing image super-resolution. As China’s premier civilian sub-meter stereo mapping satellite, GF-7 provides high-quality panchromatic imagery at 0.65-m resolution and multispectral imagery at 2.6-m resolution, establishing a solid foundation for high-fidelity SR model development. Examples of the original GF-7 satellite imagery are provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

GF-7 satellite imagery.

The dataset originates from a curated collection of 1471 full-resolution satellite scenes, each measuring 512 × 512 pixels. These scenes were strategically selected to ensure broad coverage of complex geographical environments and land cover categories, including urban areas with intricate infrastructures, dense forests, mountainous terrains, and homogeneous water bodies. This diversity is crucial for training models with strong generalization capabilities.

To formulate the dataset for deep learning-based SR training, we implemented a systematic processing pipeline. Each 512 × 512 scene was first subdivided into multiple 256 × 256 high-resolution (HR) patches. This specific patch size was chosen to maintain sufficient spatial context for capturing structural relationships while remaining computationally manageable for training complex generative models. Subsequently, each HR patch was downscaled by a factor of four using bicubic interpolation to generate its corresponding 64 × 64 low-resolution (LR) counterpart, resulting in a large set of perfectly aligned LR-HR image pairs tailored for 4× super-resolution tasks.

The finalized GF7-SR4×-MSD dataset contains 7296 rigorously validated LR-HR patch pairs. These pairs are partitioned into standardized training, validation, and testing subsets to facilitate rigorous evaluation:

- Training Set: 5832 pairs (80% of the total data) for model parameter learning.

- Validation Set: 1096 pairs (15%) for hyperparameter tuning and model selection.

- Test Set: 368 pairs (5%) for the final, impartial assessment of model performance.

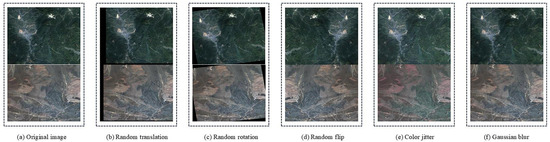

To further bolster the dataset’s robustness and mitigate overfitting, we applied an extensive data augmentation regimen during the training phase. This regimen incorporates both geometric and photometric transformations, including random rotational transformations within a range of ±45 degrees, horizontal and vertical mirroring (flipping), color jittering through controlled adjustments to brightness, contrast, and saturation, as well as the regulated introduction of Gaussian noise and blur simulation to approximate atmospheric and sensor-derived degradations. A schematic overview of this enhancement pipeline is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the enhancement process.

This comprehensive dataset construction and augmentation strategy ensures that models trained on GF7-SR4×-MSD are exposed to a wide spectrum of visual variations, thereby promoting superior generalization to real-world remote sensing scenarios.

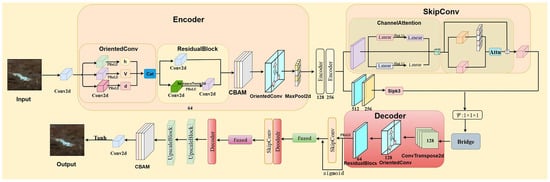

2.2. MAF-GAN Network Architecture

The proposed MAF-GAN model consists of a generator network (G) and a discriminator network (D), which are optimized jointly through adversarial training. This framework learns the complex mapping from low-resolution (LR) to high-resolution (HR) remote sensing imagery, effectively addressing both pixel-level accuracy and perceptual quality—a common limitation in existing super-resolution methods for remote sensing.

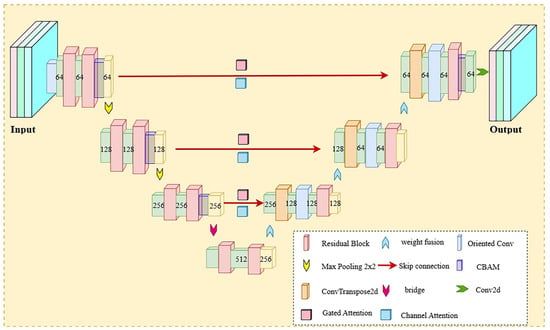

The generator is built upon a deeply customized U-Net [34], referred to as the Enhanced U-Net. This architecture incorporates several strategic enhancements tailored to the characteristics of remote sensing images. As shown in Figure 3, the encoder–decoder framework employs a three-level hierarchical structure to systematically extract, refine, and reconstruct multi-scale features. The encoder pathway progressively transforms input features using directional convolution modules that capture geometrically meaningful patterns, supported by residual blocks to maintain stability during the training of deep networks. A key innovation is the replacement of standard skip connections with an adaptive fusion mechanism. This mechanism dynamically balances the contribution of features from different abstraction levels, allowing selective enhancement of encoder features before they are integrated with corresponding decoder features. This ensures optimal use of multi-scale information throughout the reconstruction process.

Figure 3.

Structure of the generators.

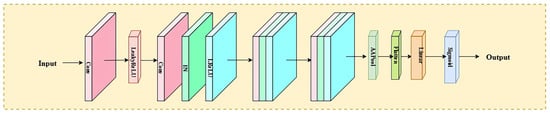

The discriminator is based on an improved PatchGAN architecture (Figure 4), which provides essential adversarial signals by discriminating between generated super-resolution images and real high-resolution references [35]. Its multi-scale discrimination strategy evaluates both local texture authenticity and global structural consistency. This encourages the generator to produce visually convincing results while preserving geometric accuracy—a critical requirement in remote sensing, where structural fidelity directly affects interpretability.

Figure 4.

Structure of the discriminators.

2.2.1. Generator: Enhanced U-Net Design

The Enhanced U-Net generator represents a sophisticated evolution of the classical encoder–decoder architecture, specifically engineered to address the multifaceted challenges of remote sensing image super-resolution. Its overall structure, depicting the hierarchical encoder–decoder pathway with adaptive fusion skip connections, is illustrated in Figure 5. This section provides a comprehensive technical description of the core components and their integrative design principles.

Figure 5.

Structure of the Enhanced U-Net Module.

Core Module Designs

The architecture integrates several specialized modules that collectively enable advanced feature extraction, calibration, and reconstruction:

- Oriented Convolution Module: To directly enhance the model’s capability for reconstructing anisotropic features, we introduce the Oriented Convolution Module. This module moves beyond the isotropic filtering of standard convolutions by decomposing the feature extraction process into three orientation-specific pathways: horizontal (3 × 1 kernel), vertical (1 × 3 kernel), and diagonal (3 × 3 kernel). This targeted approach ensures that fine linear structures are amplified and preserved without being diluted by responses from irrelevant directions. A key innovation is our adaptive channel allocation strategy, which dynamically configures the network’s representational resources. Recognizing that horizontal and vertical edges are predominant in man-made and natural landscapes, we prioritize them by allocating max(1, out_channels//4) channels to each, granting them sufficient capacity. The diagonal branch, serving as a complementary capture for complex contours, utilizes the remainder. Learnable non-linearity via PReLU is incorporated per branch for refined feature transformation. The concatenation of these specialized outputs yields a powerful, direction-enriched feature set that is critical for high-fidelity reconstruction of geometric details.

- Multi-Attention Mechanism: A coordinated attention system refines features through the following components:Channel Attention: An enhanced variant of the Squeeze-and-Excitation network combines global average and max pooling. The resulting features are processed by a two-layer MLP with a reduction ratio of 8, generating channel-wise weights that emphasize semantically important features.Gated Attention: This module enables cross-scale feature interaction via theta (feature transformation) and phi (context extraction) branches. A sigmoid gating mechanism dynamically calibrates spatial relevance, while residual connections help maintain gradient stability.Spectral Attention: Designed specifically for multispectral data, this module captures inter-band correlations essential for color fidelity. Dimensional stability is ensured by setting the internal reduction channel to max(1, channels//reduction).

- Residual Block with Instance Normalization: Each block contains two convolutional layers, each followed by Instance Normalization and PReLU activation. Adaptive shortcut connections (using 1 × 1 convolution when channel dimensions differ, otherwise identity) enable complex transformations while preserving gradient flow.

- Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM): This hybrid attention mechanism sequentially applies channel and spatial attention. The channel sub-module processes both average- and max-pooled features through a shared MLP. The spatial sub-module applies a 7 × 7 convolution to concatenated spatial features.

- Upscale Block with Pixel Shuffle: This block efficiently increases resolution through channel expansion (by 4×) followed by the PixelShuffle operation for 2× upsampling. Subsequent OrientedConv and Residual Block layers refine the upscaled features, preserving directional sensitivity.

Encoder Pathway with Hierarchical Processing

The encoder implements a three-stage hierarchical structure that progressively transforms input features while preserving essential spatial and spectral information. Each stage follows a consistent workflow: OrientedConv modules extract direction-aware features, Residual Blocks enable deep feature learning, and attention mechanisms perform feature calibration tailored to the network depth. Shallow stages (enc1, enc2) employ CBAM for simultaneous channel and spatial refinement, while the deeper stage (enc3) uses Spectral Attention to maintain multispectral characteristics. Each stage concludes with 2× max pooling (using ceil_mode = True to accommodate varying input sizes), systematically expanding the receptive field.

Bridge Section and Feature Transformation

Acting as the critical link between the encoder and decoder, the bridge section employs sequential residual blocks to compress and enhance high-level semantic features. This process transforms 256-channel features through a 512-channel bottleneck before projecting back to 256 channels, producing a distilled yet semantically rich representation. This representation provides a robust foundation for subsequent upsampling operations in the decoder.

Decoder Pathway with Adaptive Fusion

The decoder uses transposed convolutions (kernel = 4, stride = 2, padding = 1) to progressively restore spatial resolution, effectively reversing the encoder’s downsampling. The key innovation here is the adaptive fusion mechanism that replaces simple concatenation. Each skip connection includes a dedicated enhancement module (Residual Block + Channel Attention + Gated Attention), which fine-tunes the encoder features before fusion. A learnable weight map, derived from decoder features via a sigmoid activation, enables dynamic blending: fusion_weight × decoder_features + (1 − fusion_weight) × enhanced_encoder_features. This allows the network to autonomously determine the optimal fusion ratio across different abstraction levels, significantly improving the preservation of multi-scale features and structural integrity during reconstruction.

The complete generator begins with an initial convolution and spectral attention layer, processes features through the Enhanced U-Net core, and ends with sequential upscaling blocks to achieve 4× super-resolution. A global residual connection adds a bicubically upsampled version of the input to the network output, simplifying the learning objective to residual detail reconstruction. The final tanh activation constrains outputs to the range [−1, 1], with clamping applied for numerical stability. Through these carefully designed components and their interactions, the generator successfully bridges the gap between pixel-level accuracy and perceptual quality in remote sensing image super-resolution.

2.2.2. Discriminator: Multi-Scale PatchGAN Design

The discriminator employs a multi-scale architecture [36] based on PatchGAN. Its core design principle is to achieve accurate discrimination of both local texture details and global structural consistency in the generated images through a multi-level feature extraction and fusion mechanism. The network adopts a four-level downsampling structure. Each level consists of a convolutional layer, an instance normalization layer, and a LeakyReLU activation function with a negative slope of 0.2.

Specifically, an input 256 × 256 pixel image is first processed by a 4 × 4 convolution with 64 channels and a stride of 2. This is followed by three successive convolutional layers utilizing 128, 256, and 512 channels, respectively, each with a stride of 2 to progressively compress the spatial dimensions of the feature maps. The resulting feature maps are then compressed to a size of 1 × 1 via adaptive average pooling, and a final fully connected layer with a Sigmoid activation function outputs the authenticity probability.

Crucially, feature maps from each downsampling stage are preserved. These multi-scale features are upsampled to the original input resolution using bilinear interpolation and then fused through a channel attention-based weighting strategy. This design enables the discriminator to synergistically perceive local textures and global structures, significantly enhancing its ability to assess typical features in remote sensing imagery, such as road edges and building contours.

To improve training stability, spectral normalization is applied to the convolutional layers. Furthermore, the least squares loss is adopted instead of the traditional cross-entropy loss, which effectively mitigates the gradient vanishing problem.

Through this multi-level feature extraction and fusion, the discriminator provides rich gradient signals to guide the generator. To ensure these signals effectively balance different optimization objectives, the model relies on a comprehensive, well-designed loss function system. The specific composition and mechanisms of this multi-component loss function are detailed in the following subsection.

2.3. Composite Loss Function

To address the multifaceted challenges of remote sensing image super-resolution, we adopt a multi-objective joint optimization strategy and construct a composite loss function. This function comprehensively constrains the reconstructed images in terms of pixel accuracy, perceptual quality, spatial smoothness, and internal feature consistency, ensuring an optimal balance across multiple performance dimensions. The total loss function is defined as:

where λadv, λper, λpix, λtv and λfeat are weighting coefficients that balance the contribution of each loss component. The specific definitions, design motivations, and mathematical expressions of each loss term are detailed below:

- Adversarial Loss [37]: This loss term leverages a relativistic discriminator [37] to narrow the distribution gap between super-resolved images and real high-resolution (HR) images. By guiding the generator to produce outputs that are perceptually indistinguishable from genuine remote sensing data, it effectively addresses the over-smoothing issue common in pixel-wise optimization methods. The core goal is to enhance the visual authenticity of textures and details in reconstructed images, making them more consistent with the natural characteristics of remote sensing scenes. Its mathematical expression is:

- Perceptual Loss [38]: Calculated in the feature space of a pre-trained VGG-19 network [38], this loss term focuses on maintaining semantic consistency between generated images and reference HR images. It does not directly compare pixel-level differences but instead aligns high-level feature representations, which is critical for preserving the ecological and geometric characteristics unique to remote sensing imagery (e.g., land cover patterns, terrain structures). The formula is defined as:

- Pixel Loss [39]: As the foundation for ensuring reconstruction accuracy, this loss term combines L1 loss and Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss to enforce pixel-level fidelity between reconstructed and reference images. The L1 component ensures stable gradient propagation during training, while the MSE component emphasizes penalizing large pixel errors, jointly guaranteeing that the reconstructed images closely match the ground truth at the intensity level. Its expression is:

- Total Variation Loss (TVL) [40]: Introduced as a regularization term [40], this loss imposes spatial smoothness constraints on the generated images. It suppresses unrealistic high-frequency artifacts and noise by penalizing sudden intensity transitions between adjacent pixels, which is particularly important for remote sensing applications—unnatural pixel transitions can severely compromise the interpretability of fine-scale features such as road edges and field boundaries. The formula is:

- Feature Consistency Loss [41]: As a pivotal innovation in this work, we propose a novel Feature Consistency Loss to tackle feature degradation in deep super-resolution networks. Conventional loss functions typically neglect the integrity of intermediate feature representations during reconstruction, leading to structural incoherence for geometrically complex elements (e.g., building contours, transportation networks) that are crucial for remote sensing analysis. To address this, Lfeat preserves the stability and discriminative capability of intermediate features through a holistic dual-path alignment strategy.

The initial range for each loss weight was determined through theoretical analysis, followed by fine-tuning using a grid search [42] to obtain the final optimal configuration. The configuration follows the following principles: the perceptual loss (Lper) is given a high weight (0.7) to guarantee the consistency of the reconstructed image in terms of semantic features; the pixel loss (Lpix) is used as the basis of the reconstruction, and the weight is set to 3.0 to ensure the pixel-level accuracy; the adversarial loss (Ladv) is set to a weight of 0.03, which enhances the realism of the texture and at the same time maintains the stability of the training; the total variation loss (Ltv) and feature consistency loss (Lfeat) are set as regular terms with weights of 10−4 and 5 × 10−4, respectively, to slightly constrain spatial smoothing and feature stability and avoid over-smoothing. The final weight combinations (λadv = 0.03, λper = 0.7, λpix = 3.0, λtv = 10−4, λfeat = 5 × 10−4) aim at balancing multiple optimization objectives, and their effectiveness will be further verified in the subsequent ablation experiments.

2.4. Implementation Details

2.4.1. Experimental Setup

All experiments were implemented in PyTorch 2.6 on a workstation with an Intel E5-2650 v4 processor and NVIDIA Quadro P6000 GPUs, using a fixed random seed of 42 for reproducibility. Our proposed MAF-GAN model was trained using the Adam optimizer (β1 = 0.9, β2 = 0.999) with an initial learning rate of 1 × 10−4 for both generator and discriminator, a batch size of 8, and 300 epochs. We employed a step decay scheduler that reduced the learning rate by half every 100 epochs, optimized the model with the composite loss function defined in Equation (1), and initialized all weights using the He method.

For a fair comparison, all baseline and competing models were trained and evaluated on the same GF7-SR4×-MSD dataset. Trainable models were run under their respective recommended settings, while non-trainable methods (Bicubic) were applied directly to the test data. Detailed configurations for all learning-based models are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Training configurations for baseline and competing models.

2.4.2. Evaluation Protocol

All models, including the non-trainable Bicubic interpolation and the externally configured EsatSR, were evaluated on the same dedicated test set of 368 image pairs from GF7-SR4×-MSD. The evaluation metrics included Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), Structural Similarity Index (SSIM), Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS), Spectral Angle Mapper (SAM), and inference time. The same data augmentation strategies as described in Section 2.1 were applied consistently during the training of all learning-based models to ensure a fair comparison. The computational environment (PyTorch 2.6, CUDA 11.8, Python 3.9) remained identical across all experiments to guarantee consistent measurements of inference efficiency.

3. Results

3.1. Comparative Experiments

To objectively evaluate the super-resolution reconstruction performance, this study adopts PSNR and Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) as evaluation metrics. PSNR is calculated based on MSE, reflecting the pixel-level fidelity between the reconstructed image and the real HR image; SSIM evaluates image similarity from three dimensions: brightness, contrast, and structure, which better aligns with the perceptual characteristics of the human visual system. The specific calculation formulas are as follows:

- The PSNR is defined as:

- The MSE is defined as:

- The formula for SSIM is:

Furthermore, to delve deeper into the perceptual and spectral characteristics, we introduce two advanced metrics:

- The LPIPS metric is designed to quantify the perceptual similarity between two images. Unlike PSNR and SSIM, LPIPS utilizes a pre-trained deep neural network to extract features and compute the distance in that high-level feature space, which has been shown to align better with human visual perception. A lower LPIPS value indicates higher perceptual similarity to the reference image.

- The SAM is a crucial metric in remote sensing that measures the spectral fidelity of the reconstructed image. It calculates the angle between the spectral vectors of the reconstructed and real HR images in the multispectral space. A smaller SAM value (in radians) signifies better preservation of the original spectral information, which is paramount for subsequent remote sensing applications like classification and material identification.

3.1.1. Objective Metrics and Computational Performance

Table 2 provides a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed MAF-GAN against eight established super-resolution techniques on the GF7-SR4×-MSD dataset. The comparison spans methodological categories from traditional interpolation (Bicubic) and compact CNNs (SRCNN) to contemporary GAN-based architectures (SRGAN, ESRGAN, Real-ESRGAN) and modern Transformer-based methods (SwinIR, HAT), with the addition of the efficient ESatSR model for a more rigorous benchmark. The evaluation incorporates a complete set of metrics, including PSNR, SSIM, LPIPS, SAM, and Inference Time, to offer a holistic assessment of reconstruction performance.

Table 2.

Comparison Experiments of Different Models.

As quantified in Table 2, the proposed MAF-GAN achieved a PSNR of 27.14 dB, an SSIM of 0.7206, an LPIPS of 0.1017, a SAM of 1.0871, and an inference time of 24.51 ms. Among the compared methods, these values represent the highest recorded PSNR and SSIM, and the lowest LPIPS. The inference time of the proposed method was lower than that of SRGAN (36.10 ms), Real-ESRGAN (46.62 ms), SwinIR (42.30 ms), and HAT (86.04 ms), and was comparable to ESRGAN (23.54 ms) and ESatSR (22.65 ms). With 16.93 million parameters, the model’s parameter count was similar to SRGAN (16.70 M) and Real-ESRGAN (16.70 M), lower than ESRGAN (48.60 M) and ESatSR (23.76 M), and higher than SwinIR (11.80 M) and HAT (13.94 M).

3.1.2. Subjective Perception and Visual Assessment

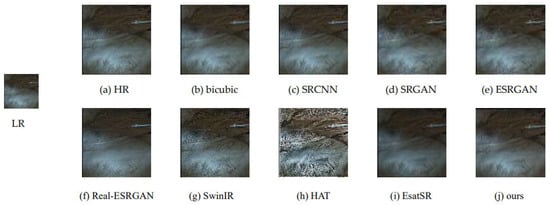

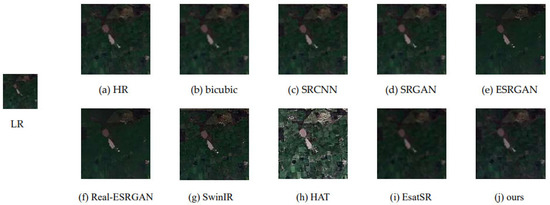

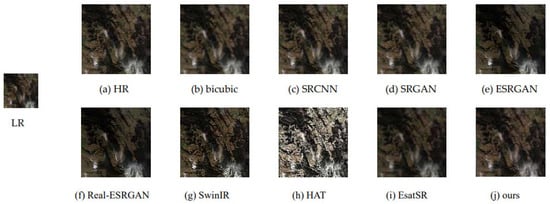

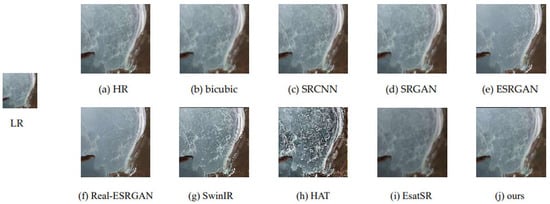

To intuitively evaluate the perceptual quality across diverse landscapes, visual comparisons from four representative remote sensing scenarios are presented: mountainous terrain with cloud cover, agricultural regions with water bodies, mountain gullies, and coastal landscapes. The reconstruction results of all compared methods on these scenes are displayed in Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9.

Figure 6.

Mountainous Terrain with Cloud Cover.

Figure 7.

Agricultural Region with Water Bodies.

Figure 8.

Mountain Gully Scene.

Figure 9.

Coastal Landscape.

Figure 6 presents the visual comparison for a mountainous scene with cloud cover. The high-resolution reference image (a) exhibits well-defined mountain layers, cloud textures, and topographic boundaries. The Bicubic interpolation result (b) appears blurred, with indistinct mountainous features beneath clouds and smoothed terrain contours. The SRCNN result (c) shows marginal improvement but retains soft boundaries for mountain ridges and cloud layers. Results from SRGAN (d) and ESRGAN (e) display enhanced detail but also introduce visible sharpening artifacts, particularly in cloud-obscured areas. The Real-ESRGAN result (f) shows pronounced edge definition but with intensified mountain folds and cloud patterns. The SwinIR result (g) presents a natural appearance but with subtly blurred mountain folds. The HAT result (h) exhibits enhanced textures and structural patterns that differ from the reference. The ESatSR result (i) shows a restoration of cloud and mountain details. The proposed method’s result (j) displays layered mountain topography, cloud textures, and terrain boundaries.

Figure 7 shows the reconstruction results for an agricultural area with water bodies. The reference image (a) features distinct field boundaries, water textures, and object details. The Bicubic result (b) exhibits merged field-water boundaries and blurred details. The SRCNN result (c) offers slight improvement but retains insufficient sharpness. Results from SRGAN (d) and ESRGAN (e) show enhanced detail with sharpening effects in field textures and at water boundaries. The Real-ESRGAN result (f) has defined edges but with intensified field and water textures. The SwinIR result (g) maintains visual naturalness with some blurring in field ridges. The HAT result (h) displays distorted field patterns and object shapes. The ESatSR result (i) shows a restoration of field textures and boundaries. The result from the proposed method (j) presents field-water boundaries, field ridge textures, and object details.

Figure 8 illustrates the performance on a mountain gully scene. The reference image (a) features distinct gully textures and terrain layers. The Bicubic result (b) is characterized by blurred textures and a flattened visual effect. The SRCNN result (c) shows improvement but retains soft textures and edges. Results from SRGAN (d) and ESRGAN (e) display enhanced detail with sharpening noise in mountain textures. The Real-ESRGAN result (f) shows better edge definition but with intensified gully textures. The SwinIR result (g) ensures naturalness but lacks clarity in textures and edges. The HAT result (h) exhibits significant texture distortion and structural patterns. The ESatSR result (i) presents restored mountain gully textures and layers. The result from the proposed method (j) shows gully texture layers and terrain edges.

Figure 9 provides the visual comparison for a coastal scene. The reference image (a) displays clear coastal contours, wave textures, and shoreline details. The Bicubic result (b) shows blurred contours, textures, and details. The SRCNN result (c) provides marginal improvement but lacks sharpness. Results from SRGAN (d) and ESRGAN (e) show enhanced detail with sharpening artifacts in wave textures. The Real-ESRGAN result (f) has defined edges but with enhanced wave textures and contours. The SwinIR result (g) maintains a natural appearance but lacks clarity in contours and textures. The HAT result (h) displays distorted wave patterns. The ESatSR result (i) shows restored coastal contours and wave textures. The result from the proposed method (j) presents coastal contours, wave textures, and shoreline details.

3.2. Ablation Experiments

3.2.1. Model Experiments

To systematically evaluate the contribution of each module to the reconstruction performance, we conducted rigorous ablation studies, with the results shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Model Ablation Experiment.

The Base model (0.92 M parameters, 4.44 GFLOPs) achieves a PSNR of 26.25 dB and an SSIM of 0.6810 with an inference time of 1.90 ms. Progressively integrating the OrientedConv module (0.94 M, 4.68 GFLOPs) improved PSNR to 26.44 dB and SSIM to 0.6895 (inference time: 2.69 ms). The subsequent addition of the attention mechanism (0.93 M, 5.15 GFLOPs) increased PSNR to 26.71 dB and SSIM to 0.6957 (inference time: 3.29 ms). Incorporating the multi-scale feature fusion module (0.98 M, 5.42 GFLOPs) resulted in a PSNR of 26.67 dB and an SSIM of 0.6921, while optimizing inference time to 2.53 ms. The integration of all modules into the Full Model (2.98 M, 16.35 GFLOPs) yielded a PSNR of 26.83 dB and an SSIM of 0.6988 (inference time: 12.05 ms). Finally, the enhanced generator (12.70 M, 23.01 GFLOPs) achieves the best performance with a PSNR of 27.14 dB, an SSIM of 0.7206, and an inference time of 23.50 ms.

3.2.2. Loss Function Experiments

To further validate the effectiveness of the multi-component loss function, this study systematically evaluated the impact of different loss function combinations on super-resolution reconstruction performance, with quantitative results shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Ablation Experiments of Loss Functions.

Experimental Group 1, utilizing only the L1 and MSE-based Pixel Loss, established a baseline performance of 26.82 dB in PSNR and 0.6950 in SSIM. The introduction of Relativistic Adversarial Loss in Group 2 resulted in a PSNR of 26.15 dB and an SSIM of 0.7080. Group 3, which combined Pixel Loss with VGG-based Perceptual Loss, yielded a PSNR of 26.58 dB and an SSIM of 0.7150. Expanding this combination with Total Variation Loss (Group 4) led to a PSNR of 26.55 dB and an SSIM of 0.7165. Finally, the complete loss combination in Group 5—integrating Pixel, Adversarial, Perceptual, Total Variation, and the proposed Feature Consistency Loss—achieved the highest performance, with a PSNR of 27.14 dB and an SSIM of 0.7206.

4. Discussion

4.1. Overall Superiority of MAF-GAN

Experimental results clearly validate that the proposed MAF-GAN offers a robust, effective approach to remote sensing image super-resolution, striking an excellent balance across key performance dimensions. Objective metrics and computational efficiency analyses detailed in Section 3.1.1 and summarized in Table 1 quantitatively confirm the model’s effectiveness. Among all compared methods, our approach achieves the highest PSNR (27.14 dB) and SSIM (0.7206), alongside the lowest LPIPS (0.1017). This concurrent leadership across pixel-level fidelity, structural consistency, and perceptual quality metrics indicates that MAF-GAN successfully alleviates the long-standing perception–distortion trade-off in super-resolution tasks.

A detailed comparison across methodological paradigms further elucidates the source of this advantage. When benchmarked against the Transformer-based HAT, MAF-GAN not only achieves a higher PSNR but also establishes a significant SSIM improvement (+0.0388), while delivering inference speeds over three times faster. This demonstrates that our enhanced convolutional design can match or exceed the representational capacity of computationally intensive self-attention mechanisms for this task. Compared to GAN-based approaches like ESRGAN, our method achieves superior reconstruction quality while using only about one-third of the parameters, highlighting exceptional parameter efficiency and a more stable training paradigm. When compared to the specialized remote sensing model ESatSR, MAF-GAN achieves a superior PSNR and SSIM while maintaining a comparable inference time, demonstrating that our approach not only leverages domain-specific insights but also introduces more effective architectural innovations. Furthermore, despite the strong performance of the transformer-based HAT on generic benchmarks, MAF-GAN surpasses it in both reconstruction accuracy (PSNR) and perceptual quality (SSIM) on our remote sensing dataset, and does so with significantly higher computational efficiency (3.5× faster inference). This indicates that our enhanced convolutional design, tailored for geo-spatial features, can be more effective than general-purpose attention mechanisms for this domain.

This comprehensive performance advantage stems from the model’s key architectural innovations. Oriented convolution modules serve as the core component for capturing directional structures and edge details, directly enhancing the precision of spatial information reconstruction. Additionally, the multi-attention fusion mechanism adaptively refines features across channel-wise and spatial contexts—an essential design choice that enables the generation of perceptually realistic textures while preserving structural coherence in remote sensing imagery.

Quantitative strengths are further supported by subjective visual assessments presented in Section 3.1.2. Across the diverse, challenging scenes illustrated in Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9, MAF-GAN consistently delivers the most visually authentic super-resolved results. It effectively avoids the blurring artifacts typical of interpolation-based methods, the unnatural distortions associated with conventional GANs, and the structural inconsistencies observed in other advanced models. Such consistent high-quality output across varied geographical and thematic content underscores MAF-GAN’s strong generalization capability for complex remote sensing datasets.

Overall, MAF-GAN achieves state-of-the-art performance by synergistically integrating oriented feature extraction, multi-dimensional attention mechanisms, and adaptive feature fusion. Validated through both rigorous objective metrics and subjective visual evaluations, this design provides a powerful, practical framework for high-quality remote sensing image super-resolution, effectively addressing the limitations of current Transformer-based, GAN-based, and lightweight approaches.

4.2. Model Component Analysis

Systematic ablation studies in Section 3.2.1 and Section 3.2.2 offer compelling evidence for the effectiveness of each component within the MAF-GAN framework. The gradual performance improvements observed in these experiments validate our core design decisions and highlight how these components work synergistically to enhance the model’s final performance.

4.2.1. Loss Function Experiments

Model ablation results—detailed in Table 2—show a clear, logical performance improvement trend as key components are gradually integrated. Adding the Oriented Convolution module to the Base model improved PSNR by 0.19 dB, verifying its ability to capture directional features—critical for reconstructing linear structures (e.g., roads, building edges) in remote sensing images. This specialized convolution strategy models geometric patterns more precisely than standard isotropic convolutions.

Subsequent integration of attention mechanisms delivered the most notable individual performance gain, increasing PSNR by 0.46 dB compared to the OrientedConv-enhanced baseline. This substantial improvement underscores the importance of adaptive feature calibration in remote sensing super-resolution: across diverse geographical scenarios, the relevance of different regions and channels varies significantly, and attention mechanisms enable the network to dynamically prioritize semantically important features while suppressing less informative ones.

The multi-scale feature fusion module helped optimize inference speed while preserving competitive performance, cutting processing time from 3.29 ms to 2.53 ms. This efficiency gain demonstrates the module’s ability to enhance feature reuse without adding computational overhead, effectively streamlining information flow across network layers.

When all components were integrated into the Full Model, we observed synergistic effects that exceeded their individual contributions—PSNR improved by 0.58 dB relative to the Base model. This non-linear performance boost confirms the components’ complementary roles: oriented convolutions provide geometrically meaningful features, which are then refined by attention mechanisms and efficiently propagated via the fusion strategy. The complete Enhanced Generator configuration strikes the optimal balance, achieving state-of-the-art performance (27.14 dB PSNR, 0.7206 SSIM) while meeting practical computational requirements.

4.2.2. Loss Function Analysis

Loss function ablation studies—quantified in Table 3—reveal the distinct, complementary roles of each loss component in determining final output quality. Baseline Pixel Loss alone achieves strong pixel-level accuracy (26.82 dB PSNR) but generates perceptually unsatisfactory results with insufficient texture detail—evident from the moderate SSIM value (0.6950).

Introducing Adversarial Loss induces the expected perception-distortion trade-off: PSNR decreases by 0.67 dB, while SSIM improves significantly by 0.013. This pattern confirms that adversarial training effectively promotes high-frequency texture generation and visual realism, though at the cost of strict pixel-wise accuracy. Perceptual Loss then serves as a balancing factor, recovering most of the lost PSNR (reaching 26.58 dB) while further improving structural consistency (SSIM: 0.7150)—demonstrating its role in preserving semantic content and global structural coherence.

Adding Total Variation Loss delivers subtle refinement: PSNR decreases slightly, while SSIM improves marginally. This behavior aligns with its regularization function—suppressing unrealistic high-frequency noise and enhancing spatial smoothness—benefiting perceptual quality without noticeably compromising pixel accuracy.

Most notably, the full loss combination—including our proposed Feature Consistency Loss—achieves optimal performance across all metrics, outperforming even the Pixel Loss baseline by 0.32 dB in PSNR and 0.0256 in SSIM. This result confirms that our composite loss function does not merely balance competing objectives, but actively reconciles the perception-distortion trade-off. The Feature Consistency Loss appears to stabilize intermediate feature representations, ensuring enhanced visual realism does not come at the expense of structural integrity.

In summary, ablation studies confirm that every architectural component and loss term in MAF-GAN fulfills a distinct, essential role. Their careful integration creates synergistic effects that collectively enable the model to achieve state-of-the-art performance in remote sensing image super-resolution.

5. Conclusions

This study develops a Multi-Attention Fusion Generative Adversarial Network (MAF-GAN) tailored for remote sensing image super-resolution. By integrating oriented convolution modules, a hierarchical attention mechanism, and adaptive feature fusion strategies, the model enables effective capture of directional structures and fine-grained details—thereby achieving significant improvements in reconstruction quality.

Comprehensive experimental evaluations show that MAF-GAN outperforms current state-of-the-art approaches across key quantitative metrics, including PSNR and SSIM, while sustaining a desirable balance between performance and computational efficiency. Systematic ablation studies further validate the individual contributions of each proposed module, as well as their synergistic effects—confirming the rationality and effectiveness of the overall architectural design.

Beyond the super-resolution performance demonstrated in this study, the high-quality reconstruction achieved by MAF-GAN holds significant promise for enhancing downstream remote sensing applications. The precisely reconstructed directional structures and well-preserved spectral characteristics could substantially benefit advanced classification models, such as those employing dynamic token selection, by providing more discriminative spatial patterns. Similarly, the clear object boundaries and texture details may improve the accuracy of object detection frameworks that rely on multi-instance analysis. Furthermore, the spatial and spectral consistency maintained in our super-resolved images is crucial for reliable change detection using dual-domain attention mechanisms. Validating the integration of MAF-GAN as a preprocessing module for these advanced analytical tasks represents a compelling direction for future research.

Future research will explore multiple promising directions: first, developing lightweight architectures to support real-time applications on edge devices; second, fusing multi-modal remote sensing data to enhance super-resolution performance under complex scenarios; third, conducting rigorous validation in downstream tasks (e.g., land cover classification, change detection). These initiatives seek to further narrow the gap between advanced super-resolution research and its practical deployment in the remote sensing domain.

In conclusion, this study offers a robust, effective technical approach to high-resolution remote sensing image reconstruction, and holds potential for driving broader progress in remote sensing image processing and analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.W. (Zhaohe Wang); methodology, Z.W. (Zhaohe Wang); software, Z.W. (Zhaohe Wang); validation, Z.W. (Zhaohe Wang) and J.C.; formal analysis, Z.W. (Zhaohe Wang); investigation, Z.W. (Zhaohe Wang); resources, Z.W. (Zhongwu Wang) and H.T.; data curation, J.C. and H.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.W. (Zhaohe Wang); writing—review and editing, Z.W. (Zhaohe Wang), J.C., Z.W. (Zhongwu Wang), H.Z. and H.T.; visualization, Z.W. (Zhaohe Wang); supervision, H.T.; project administration, H.T.; funding acquisition, H.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Civil Aerospace Preresearch Project (D040105) (Center Project No. BH2501).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to restrictions (e.g., their proprietary nature or privacy agreements).

Acknowledgments

No human or animal subjects were involved in this study; thus, no ethical approval was required. During the preparation of this manuscript, the author used ChatGPT-4o (by OpenAI) and DeepSeek-V3 (by DeepSeek Company) solely for the purpose of improving grammatical correctness, spelling, punctuation, and formatting of the text. After using these tools, the author reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the final content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network |

| MAF-GAN | Multi-Attention Fusion Generative Adversarial Network |

| SR | Super-Resolution |

| HR | High-Resolution |

| LR | Low-Resolution |

| PSNR | Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| SSIM | Structural Similarity Index |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| CBAM | Convolutional Block Attention Module |

| CA | Channel Attention |

| GA | Gated Attention |

| SA | Spectral Attention |

| TV Loss | Total Variation Loss |

| FLOPs | Floating Point Operations |

References

- Liang, W.; Liu, Y. CSAN: A Channel–Spatial Attention-Based Network for Meteorological Satellite Image Super-Resolution. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhu, F.; Zhu, B.; Li, P.; Han, Y. A Lightweight Hybrid Neural Network for Remote Sensing Image Super-Resolution Reconstruction. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 157, 111438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, C.; Wang, C.; Lu, B.; Yang, W.; Zhang, X.; Wang, G. NGSTGAN: N-Gram Swin Transformer and Multi-Attention U-Net Discriminator for Efficient Multi-Spectral Remote Sensing Image Super-Resolution. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Su, C. Super Resolution Reconstruction of Mars Thermal Infrared Remote Sensing Images Integrating Multi-Source Data. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, U.; Hoque, M.Z.; Wang, W.; Oussalah, M. Patch-Based Discriminative Learning for Remote Sensing Scene Classification. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Fan, J.; Li, Z.; Xie, Y. Elevating Detection Performance in Optical Remote Sensing Image Object Detection: A Dual Strategy with Spatially Adaptive Angle-Aware Networks and Edge-Aware Skewed Bounding Box Loss Function. Sensors 2024, 24, 5342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Lu, X. The Spectral-Spatial Joint Learning for Change Detection in Multispectral Imagery. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Sun, L.; Chehri, A.; Song, Y. A Review of GAN-Based Super-Resolution Reconstruction for Optical Remote Sensing Images. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Gao, Y.; Chen, L.; Liu, X. Dual-Resolution Local Attention Unfolding Network for Optical Remote Sensing Image Super-Resolution. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Loy, C.C.; He, K.; Tang, X. Image Super-Resolution Using Deep Convolutional Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2016, 38, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, J.K.; Lee, K.M. Accurate Image Super-Resolution Using Very Deep Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 1646–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, B.; Son, S.; Kim, H.; Nah, S.; Lee, K.M. Enhanced Deep Residual Networks for Single Image Super-Resolution. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1132–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh-Thu, Q.; Ghanbari, M. Scope of Validity of PSNR in Image/Video Quality Assessment. Electron. Lett. 2008, 44, 800–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, Y.; Michaeli, T. The Perception-Distortion Tradeoff. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 6228–6237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renuka, P.; Fahimuddin, S.; Shaik, S.A.; Fareed, S.M.; Reddy, C.O.T.K.; Reddy, R.V.V. Advanced Image Generation using Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs): Innovations in Creating High-Quality Synthetic Images with AI. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Control Systems (ICICCS), Erode, India, 19–21 March 2025; pp. 1414–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledig, C.; Theis, L.; Huszár, F.; Caballero, J.; Cunningham, A.; Acosta, A.; Aitken, A.; Tejani, A.; Totz, J.; Wang, Z.; et al. Photo-Realistic Single Image Super-Resolution Using a Generative Adversarial Network. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russakovsky, O.; Deng, J.; Su, H.; Krause, J.; Satheesh, S.; Ma, S.; Huang, Z.; Karpathy, A.; Khosla, A.; Bernstein, M.; et al. ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2015, 115, 211–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yu, K.; Wu, S.; Gu, J.; Liu, Y.; Dong, C.; Qiao, Y.; Loy, C.C. ESRGAN: Enhanced Super-Resolution Generative Adversarial Networks. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2018 Workshops; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Leal-Taixé, L., Roth, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 11133, pp. 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xie, L.; Dong, C.; Shan, Y. Real-ESRGAN: Training Real-World Blind Super-Resolution with Pure Synthetic Data. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW), Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 1905–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Huangfu, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, P. ViT-ISRGAN: A High-Quality Super-Resolution Reconstruction Method for Multispectral Remote Sensing Images. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 3973–3988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Qian, Y.; Zhong, X.; Chen, L.; Yang, G. Research on super-resolution reconstruction of remote sensing images: A comprehensive review. Opt. Eng. 2021, 60, 100901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Wang, Z.; Li, Q.; Jia, X.; Xu, M. Multiattention Generative Adversarial Network for Remote Sensing Image Super-Resolution. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Cao, J.; Sun, G.; Zhang, K.; Van Gool, L.; Timofte, R. SwinIR: Image Restoration Using Swin Transformer. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW), Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 1833–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Zhou, J.; Qiao, Y.; Dong, C. HAT: Hybrid Attention Transformer for Image Restoration. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Yuan, W.; Xie, F.; Lin, B. ESatSR: Enhancing Super-Resolution for Satellite Remote Sensing Images with State Space Model and Spatial Context. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lu, W.; Wang, Z.; Hu, J.; Zhang, Z.; He, L. Multi-Window Fusion Spatial-Frequency Joint Self-Attention for Remote-Sensing Image Super-Resolution. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2015, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; Navab, N., Hornegger, J., Wells, W.M., Frangi, A.F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shao, Z.; Lu, T.; Wu, C.; Wang, J. Remote Sensing Image Super-Resolution via Multiscale Enhancement Network. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktay, O.; Schlemper, J.; Folgoc, L.L.; Lee, M.; Heinrich, M.; Misawa, K.; Mori, K.; McDonagh, S.; Hammerla, N.Y.; Kainz, B.; et al. Attention U-Net: Learning Where to Look for the Pancreas. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.03999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.K.; Krishna, G.; Dubey, S.R.; Chaudhuri, B.B. HybridSN: Exploring 3-D–2-D CNN Feature Hierarchy for Hyperspectral Image Classification. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2020, 17, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, J. A Spectral-Spatial Attention Autoencoder Network for Hyperspectral Unmixing. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2023—2023 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Pasadena, CA, USA, 16–21 July 2023; pp. 7519–7522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Meng, F.; Rodríguez-Patón, A.; Li, P.; Zheng, P.; Wang, X. U-Next: A Novel Convolution Neural Network With an Aggregation U-Net Architecture for Gallstone Segmentation in CT Images. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 166823–166832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Xu, Z.; Yin, Q.; Bao, Z.; Chen, Z.; Wang, S. A Transformer-Unet Generative Adversarial Network for the Super-Resolution Reconstruction of DEMs. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isola, P.; Zhu, J.-Y.; Zhou, T.; Efros, A.A. Image-to-Image Translation with Conditional Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 5967–5976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative Adversarial Nets. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Montreal, QC, Canada, 8–13 December 2014; Volume 2, pp. 2672–2680. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555/2969033.2969125 (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Johnson, J.; Alahi, A.; Li, F. Perceptual Losses for Real-Time Style Transfer and Super-Resolution. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2016, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Leibe, B., Matas, J., Sebe, N., Welling, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland; Volume 9906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, H.; Song, W.; Kim, J. Rethinking Pixel-Wise Loss for Face Super-Resolution. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Electronics, Information, and Communication (ICEIC), Jeju, Republic of Korea, 31 January–3 February 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahendran, A.; Vedaldi, A. Understanding Deep Image Representations by Inverting Them. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 5188–5196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Yan, J.; Zhao, J.; Li, B. Joint Cuts and Matching of Partitions in One Graph. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstra, J.; Bengio, Y. Random Search for Hyper-Parameter Optimization. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2012, 13, 281–305. Available online: http://jmlr.org/papers/v13/bergstra12a.html (accessed on 6 August 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).