From Retrieval to Fate: UAV-Based Hyperspectral Remote Sensing of Soil Nitrogen and Its Leaching Risks in a Wheat-Maize Rotation System

Highlights

- Crop hyperspectral data can be utilized to retrieve topsoil nitrate nitrogen content.

- Hyperspectral retrieval of soil nitrogen serves as an indirect indicator of nitrogen leaching.

- In long-term stable farmland systems, we can utilize crop canopy spectral infor-mation as a proxy to achieve temporally and spatially continuous monitoring of soil nitrogen through the development of retrieval models.

- In long-term stable wheat-maize rotation systems, the remote sensing retrieval results of soil nitrate nitrogen during the maize jointing stage can be used to estimate the leaching of nitrate nitrogen to deep soil layers during the period from the rainy sea-son to the filling stage.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

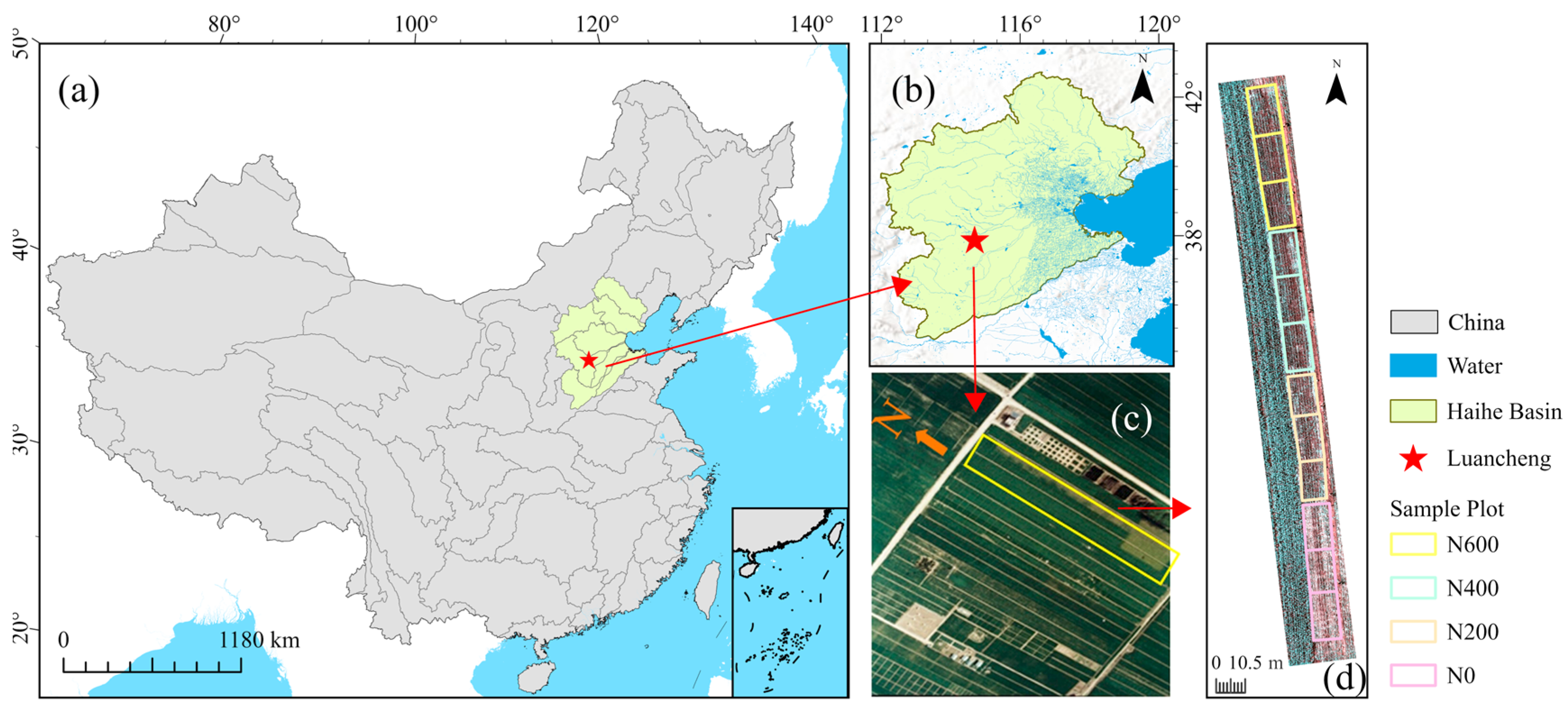

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Experimental Design and Sampling Methodology

2.2.1. Experimental Design

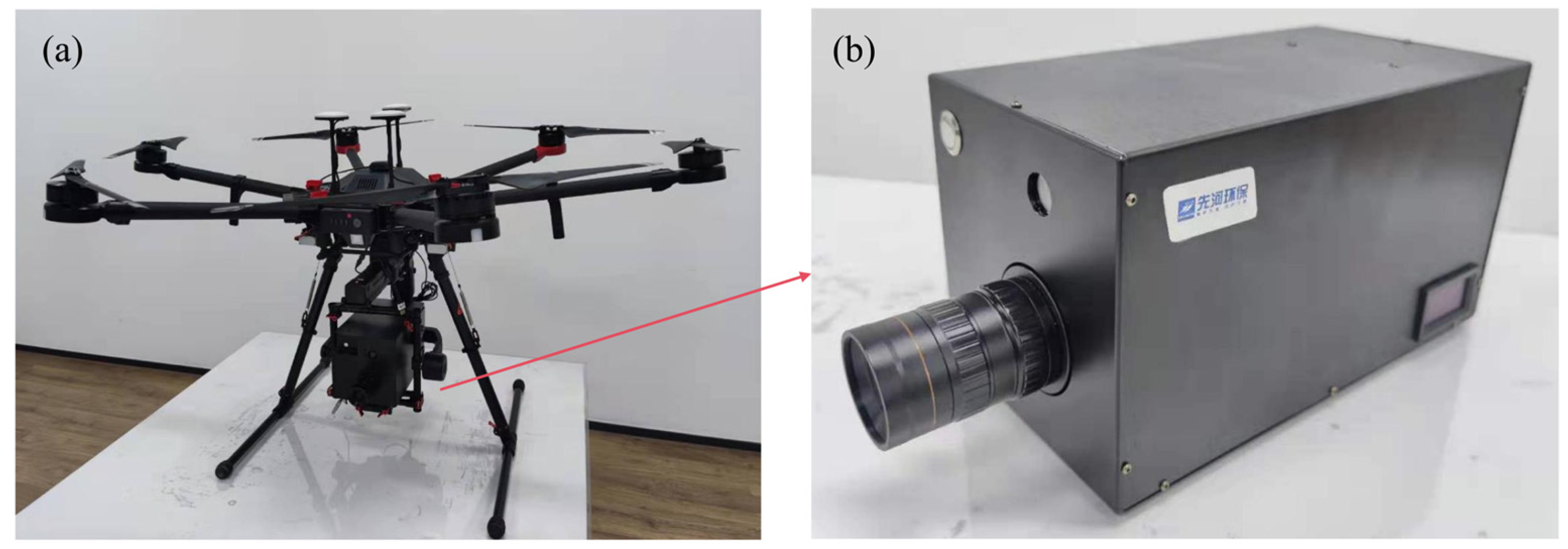

2.2.2. Hyperspectral Data Acquisition and Processing

2.2.3. Plant Characterization and Soil Profile Sampling

2.3. Analytical Items and Methods

2.3.1. Soil Water Content and NO3−-N Content

2.3.2. Soil NO3−-N Accumulation and Leaching

2.4. Data Processing and Analytical Methods

2.4.1. Fundamental Data Processing and Visualization

2.4.2. Hyperspectral Data Extraction, Preprocessing, and Feature Engineering

2.4.3. Partial Least Squares Regression Model

2.4.4. XGBoost and Model Interpretation with SHAP

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Soil NO3−-N Content, Accumulation, and Leaching During the Critical Rainy Season

3.1.1. Profile Dynamics of Soil NO3−–N Content and Accumulation

3.1.2. Nitrogen Budget and Leaching

3.2. Soil NO3−-N Retrieval Model Development and Validation

3.2.1. Spectral Data Processing

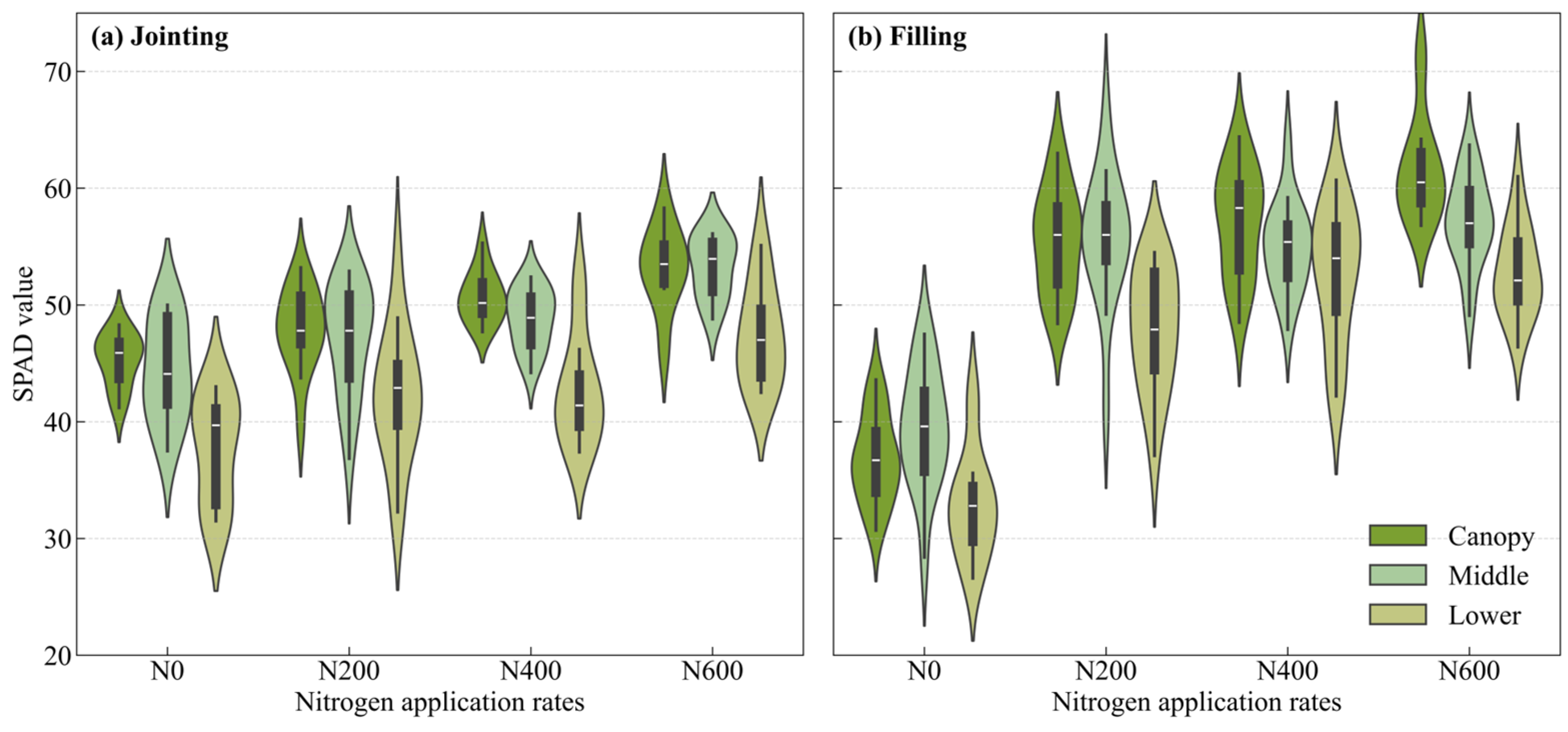

3.2.2. Crop Canopy Dynamics in Response to Soil NO3−-N

3.2.3. Development of Retrieval Models Based on Spectral Information

4. Discussion

4.1. Hyperspectral Soil Nitrogen Inversion Mediated by Vegetation

4.2. Feasibility Assessment: Nutrient Management and Nitrogen Leaching Estimation via Hyperspectral Soil Nitrogen Retrieval

4.3. Limitations and Uncertainties

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Robertson, G.P.; Vitousek, P.M. Nitrogen in Agriculture: Balancing the Cost of an Essential Resource. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2009, 34, 97–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masclaux-Daubresse, C.; Daniel-Vedele, F.; Dechorgnat, J.; Chardon, F.; Gaufichon, L.; Suzuki, A. Nitrogen Uptake, Assimilation and Remobilization in Plants: Challenges for Sustainable and Productive Agriculture. Ann. Bot. 2010, 105, 1141–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Meter, K.J.; Basu, N.B.; Veenstra, J.J.; Burras, C.L. The Nitrogen Legacy: Emerging Evidence of Nitrogen Accumulation in Anthropogenic Landscapes. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 035014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poffenbarger, H.J.; Sawyer, J.E.; Barker, D.W.; Olk, D.C.; Six, J.; Castellano, M.J. Legacy Effects of Long-Term Nitrogen Fertilizer Application on the Fate of Nitrogen Fertilizer Inputs in Continuous Maize. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 265, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zheng, W.; Wang, S.; Ma, L.; Min, L.; Shen, Y. Variation of Nitrate Sources Affected by Precipitation with Different Intensities in Groundwater in the Piedmont Plain Area of Alluvial-Pluvial Fan. J. Environ. Manage. 2024, 367, 121885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z. Research on Soil Nitrogen in China. Acta Pedol. Sin. 2008, 45, 778–783. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Yang, Q.; Chen, M.; Wang, M.; Zhang, M. An ISE-Based on-Site Soil Nitrate Nitrogen Detection System. SENSORS 2019, 19, 4669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinfield, J.V.; Fagerman, D.; Colic, O. Evaluation of Sensing Technologies for On-the-Go Detection of Macro-Nutrients in Cultivated Soils. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2010, 70, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, K.; Verrelst, J.; Féret, J.-B.; Hank, T.; Wocher, M.; Mauser, W.; Camps-Valls, G. Retrieval of Aboveground Crop Nitrogen Content with a Hybrid Machine Learning Method. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinformation 2020, 92, 102174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Kong, B.; Wang, Q.; Liu, X.; Liu, X. Hyperspectral Remote Sensing Applications in Soil: A Review. In Hyperspectral Remote Sensing; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 269–291. ISBN 978-0-08-102894-0. [Google Scholar]

- Boggs, J.L.; Tsegaye, T.D.; Coleman, T.L.; Reddy, K.C.; Fahsi, A. Relationship between Hyperspectral Reflectance, Soil Nitrate-Nitrogen, Cotton Leaf Chlorophyll, and Cotton Yield: A Step toward Precision Agriculture. J. Sustain. Agric. 2003, 22, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Meyer, S.T.; Xu, X.; Weisser, W.W.; Yu, K. Drone Multispectral Imaging Captures the Effects of Soil Mineral Nitrogen on Canopy Structure and Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Wheat. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 235, 110342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokirov, S.; Abdurahmanov, I.; Mamatkulov, Z.; Abdurahmanov, Z.; Zarifboev, D.; Oymatov, R.; Kovács, Z.; Csabai, J.; Shiping, Y.; Khakberdiev, O. Leveraging Vegetation Indices and Random Forest for Soil Nutrient Monitoring in Winter Wheat. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2025, 53, 3711–3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, W.; Zhu, J.; Wang, H. Estimation of Surface Soil Nutrient Content in Mountainous Citrus Orchards Based on Hyperspectral Data. Agriculture 2024, 14, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, B.; Qin, C.; Ji, W.; Xu, Y.; Huang, Y. High-Resolution Mapping of Soil Organic Matter at the Field Scale Using UAV Hyperspectral Images with a Small Calibration Dataset. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Cui, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, C.; Chen, X. Current Status of Soil and Plant Nutrient Management in China and Improvement Strategies. Chin. Bull. Bot. 2007, 24, 687–694. Available online: https://www.chinbullbotany.com/CN/Y2007/V24/I06/687 (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Cui, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, F. Current Nitrogen Management Status and Measures to Improve the Intensive Wheat–Maize System in China. AMBIO 2010, 39, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Shen, H.; Hu, M.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Dahlgren, R.A. Legacy Nutrient Dynamics at the Watershed Scale: Principles, Modeling, and Implications. In Advances in Agronomy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 149, pp. 237–313. ISBN 978-0-12-815177-8. [Google Scholar]

- Van Meter, K.J.; Van Cappellen, P.; Basu, N.B. Legacy Nitrogen May Prevent Achievement of Water Quality Goals in the Gulf of Mexico. Science 2018, 360, 427–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Fei, Y.; Guo, C.; Qian, Y.; Li, Y. Regional Groundwater Contamination Assessment in the North China Plain. J. Jilin Univ. Earth Sci. Ed. 2012, 42, 1456–1461. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Tang, C.; Song, X.; Yuan, R.; Han, Z.; Pan, Y. Factors Contributing to Nitrate Contamination in a Groundwater Recharge Area of the North China Plain. Hydrol. Process. 2016, 30, 2271–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Wang, S.; Tan, K.; Shen, Y.; Yang, L. Rainfall Intensity Affects the Recharge Mechanisms of Groundwater in a Headwater Basin of the North China Plain. Appl. Geochem. 2023, 155, 105742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciampitti, I.A.; Vyn, T.J. Physiological Perspectives of Changes over Time in Maize Yield Dependency on Nitrogen Uptake and Associated Nitrogen Efficiencies: A Review. Field Crops Res. 2012, 133, 48–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.; Ru, S.; Sun, S.; Zhao, O.; Hou, L.; Wang, C.; Wang, L.; Liu, L.; Zhang, G. Impact of Nitrogen Application on Nitrate Nitrogen Leaching in Winter Wheat and Summer Maize Rotation System Based on a Literature Analysis. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2022, 30, 116–125. [Google Scholar]

- XHHSIDAS, V1.0; Hebei Sailhero Environmental Protection High-Tech Co., Ltd.: Shijiazhuang, China, 2023.

- Wang, S.; Wei, S.; Liang, H.; Zheng, W.; Li, X.; Hu, C.; Currell, M.J.; Zhou, F.; Min, L. Nitrogen Stock and Leaching Rates in a Thick Vadose Zone below Areas of Long-Term Nitrogen Fertilizer Application in the North China Plain: A Future Groundwater Quality Threat. J. Hydrol. 2019, 576, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jönsson, P.; Tamura, M.; Gu, Z.; Matsushita, B.; Eklundh, L. A Simple Method for Reconstructing a High-Quality NDVI Time-Series Data Set Based on the Savitzky–Golay Filter. Remote Sens. Environ. 2004, 91, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, G.; Rodriguez, D.; O’Leary, G. Measuring and Predicting Canopy Nitrogen Nutrition in Wheat Using a Spectral Index-the Canopy Chlorophyll Content Index (CCCI). FIELD CROPS Res. 2010, 116, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondeaux, G.; Steven, M.; Baret, F. Optimization of Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 55, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J.D.; Balaguer, L.; Manrique, E.; Elvira, S.; Davison, A.W. A Reappraisal of the Use of DMSO for the Extraction and Determination of Chlorophylls a and b in Lichens and Higher Plants. Environ. Exp. Bot. 1992, 32, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, J.; Curran, P.J. The MERIS Terrestrial Chlorophyll Index. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2004, 25, 5403–5413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haboudane, D. Hyperspectral Vegetation Indices and Novel Algorithms for Predicting Green LAI of Crop Canopies: Modeling and Validation in the Context of Precision Agriculture. Remote Sens. Environ. 2004, 90, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geladi, P.; Kowalski, B.R. Partial Least-Squares Regression: A Tutorial. Anal. Chim. Acta 1986, 185, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System.; ACM: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 4768–4777. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555/3295222.3295230 (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Tan, K.; Wang, S.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, B. Geomorphologic and Sedimentary Features Dominate the Nitrogen Accumulation and Leaching in the Deep Vadose Zone from a Catchment Viewpoint. J. Hydrol. 2025, 652, 132682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; Gao, S.; Wang, X.; He, A.; He, P. Effects of Water–Nitrogen Coupling on Root Distribution and Yield of Summer Maize at Different Growth Stages. Plants 2025, 14, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X.; Zhang, Q.; Li, M.; Hou, X.; Shang, Z.; Liu, Z.; He, Y. The Shape of Reactive Nitrogen Losses from Intensive Farmland in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 915, 170014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Z.; She, D.; Pan, Y.; Abulaiti, A.; Hu, L.; Sun, X. Nitrogen Loss Due to Nitrate Reduction in the Soil Profile Depends on the Type of Cropland. GEODERMA Reg. 2025, 42, e00977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, F.; Philpot, W. Derivative Analysis of Hyperspectral Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 1997, 66, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bausch, W.; Duke, H. Remote Sensing of Plant Nitrogen Status in Corn. Trans. ASAE 1996, 39, 1869–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Mao, Z.; Li, X.; Hu, Z.; Duan, F.; Yan, Y. UAV-Based Multispectral Remote Sensing for Precision Agriculture: A Comparison between Different Cameras. ISPRS J. Photogramm. REMOTE Sens. 2018, 146, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.; Merzlyak, M. Remote Sensing of Chlorophyll Concentration in Higher Plant Leaves. Adv. Space Res. 1998, 22, 689–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fageria, N.K.; Baligar, V.C. Enhancing Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Crop Plants. Adv. Agron. 2005, 88, 97–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, S.; Guo, T.; Liu, S.; Lu, J. A Meta-Analysis of Crop Leaf Nitrogen, Phosphorus and Potassium Content Estimation Based on Hyperspectral and Multispectral Remote Sensing Techniques. Field Crops Res. 2025, 329, 109961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feilhauer, H.; Asner, G.P.; Martin, R.E.; Schmidtlein, S. Brightness-Normalized Partial Least Squares Regression for Hyperspectral Data. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2010, 111, 1947–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Feng, M.; Song, L.; Jing, B.; Xie, Y.; Wang, C.; Yang, W.; Xiao, L.; Zhang, M.; Song, X. Study on Hyperspectral Monitoring Model of Soil Total Nitrogen Content Based on Fractional-Order Derivative. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 201, 107307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Liu, S.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y. Estimation of Soil Organic Matter Content Using Selected Spectral Subset of Hyperspectral Data. Geoderma 2022, 409, 115653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Fu, Z.; Zhang, K.; Li, J.; Cao, Q.; Tian, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Cao, W.; Liu, X. Optimizing Rice In-Season Nitrogen Topdressing by Coupling Experimental and Modeling Data with Machine Learning Algorithms. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 209, 107858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, D.; Wang, J.; Chai, X. Quantitative Mapping of Soil Nitrogen Content Using Field Spectrometer and Hyperspectral Remote Sensing. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on Environmental Science and Information Application Technology, Wuhan, China, 4–5 July 2009; Volume 2, pp. 379–382. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Ma, Y.; Ma, S.; Qin, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Chen, L.; Zhu, X. Mapping Soil Available Nitrogen Using Crop-Specific Growth Information and Remote Sensing. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhu, L.; Zhuang, Q.; Chen, D.; Sun, T. Mapping Cropland Soil Nutrients Contents Based on Multi-Spectral Remote Sensing and Machine Learning. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatiadis, S.; Schepers, J.S.; Evangelou, E.; Glampedakis, A.; Glampedakis, M.; Dercas, N.; Tsadilas, C.; Tserlikakis, N.; Tsadila, E. Variable-Rate Application of High Spatial Resolution Can Improve Cotton N-Use Efficiency and Profitability. Precis. Agric. 2020, 21, 695–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, A.; Manjunath, K.R.; Panigrahy, S. Non-Point Source Pollution in Indian Agriculture: Estimation of Nitrogen Losses from Rice Crop Using Remote Sensing and GIS. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinformation 2010, 12, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; De Notaris, C.; Olesen, J.E. Autumn-Based Vegetation Indices for Estimating Nitrate Leaching during Autumn and Winter in Arable Cropping Systems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 290, 106786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewit, C. Resource Use Efficiency in Agriculture. Agric. Syst. 1992, 40, 125–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kho, R. On Crop Production and the Balance of Available Resources. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2000, 80, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, W.; Xu, X.; Hao, T.; Liu, S.; Meng, F.; Zhao, C. Effects of Nitrogen Application Rate on Annual Yield and N-Use Efficiency of Winter Wheat-Summer Maize Rotation under Drip Irrigation. J. Plant Nutr. Fertil. 2022, 28, 1271–1282. [Google Scholar]

| Vegetation Index | Formulation | References |

|---|---|---|

| NDVI | (R780 − R550)/(R780 + R550) | Fitzgerald et al. [28] |

| OSAVI | 1.16 × (R800 − R670)/(R800 + R670 + 0.16) | Rondeaux et al. [29] |

| NPQI | (R415 − R435)/(R415 + R435) | Barnes et al. [30] |

| MTCI | (R750 − R710)/(R710 + R680) | Dash et al. [31] |

| MTVI | 1.2 × (1.2 × (R800 − R550) − 2.5 × (R670 − R550)) | Haboudane et al. [32] |

| Farmland Nitrogen Budget (kg/ha) | Nitrogen Fertilizer Application Level | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N0 | N200 | N400 | N600 | |

| N application | 0 | 200 | 400 | 600 |

| Irrigation and deposition | 180 | 180 | 180 | 180 |

| Maize N uptake | −120 | −156 | −177 | −188 |

| Wheat N uptake | −120 | −149 | −175 | −176 |

| Change in 0–50 cm soil Profile NO3−-N accumulation | −18.55 | 9.60 | −71.78 | −21.86 |

| Change in 0–100 cm soil profile NO3−-N Accumulation | −26.89 | 25.01 | −155.45 | 197.35 |

| Estimated NO3−-N Leaching at 50 cm Depth | 78.55 | 214.40 | 474.78 | 613.86 |

| Estimated NO3−-N Leaching at 100 cm Depth | 86.89 | 198.99 | 558.45 | 394.65 |

| Label | Depth | Model | Training Set | Validation Set | RPD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | R2 | RMSE | MAE | ||||

| Model Mode 1 | 10 cm | PLSR | 0.48 | 0.534 | 5.617 | 4.555 | 1.464 |

| XGBoost | / | 0.534 | 5.615 | 4.537 | 1.465 | ||

| 20 cm | PLSR | 0.442 | 0.486 | 9.88 | 8.151 | 1.395 | |

| XGBoost | / | 0.469 | 10.044 | 8.242 | 1.372 | ||

| 30 cm | PLSR | 0.456 | 0.507 | 12.575 | 9.837 | 1.424 | |

| XGBoost | / | 0.445 | 13.339 | 10.314 | 1.342 | ||

| 50 cm | PLSR | 0.416 | 0.48 | 12.503 | 9.605 | 1.386 | |

| XGBoost | / | 0.412 | 13.286 | 9.729 | 1.304 | ||

| Model Mode 2 | 10 cm | PLSR | 0.912 | 0.908 | 2.494 | 1.944 | 3.298 |

| XGBoost | / | 0.911 | 2.448 | 1.886 | 3.36 | ||

| 20 cm | PLSR | 0.899 | 0.893 | 4.515 | 3.477 | 3.052 | |

| XGBoost | / | 0.883 | 4.712 | 3.603 | 2.925 | ||

| 30 cm | PLSR | 0.912 | 0.924 | 4.947 | 3.658 | 3.619 | |

| XGBoost | / | 0.911 | 5.333 | 3.54 | 3.357 | ||

| 50 cm | PLSR | 0.846 | 0.867 | 6.319 | 4.525 | 2.743 | |

| XGBoost | / | 0.847 | 6.771 | 4.08 | 2.56 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Wang, S.; Ma, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Zheng, W.; Hu, C. From Retrieval to Fate: UAV-Based Hyperspectral Remote Sensing of Soil Nitrogen and Its Leaching Risks in a Wheat-Maize Rotation System. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3956. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243956

Zhang Z, Wang S, Ma J, Wang C, Zhang Z, Li X, Zheng W, Hu C. From Retrieval to Fate: UAV-Based Hyperspectral Remote Sensing of Soil Nitrogen and Its Leaching Risks in a Wheat-Maize Rotation System. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):3956. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243956

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zilong, Shiqin Wang, Jingjin Ma, Chunying Wang, Zhixiong Zhang, Xiaoxin Li, Wenbo Zheng, and Chunsheng Hu. 2025. "From Retrieval to Fate: UAV-Based Hyperspectral Remote Sensing of Soil Nitrogen and Its Leaching Risks in a Wheat-Maize Rotation System" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 3956. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243956

APA StyleZhang, Z., Wang, S., Ma, J., Wang, C., Zhang, Z., Li, X., Zheng, W., & Hu, C. (2025). From Retrieval to Fate: UAV-Based Hyperspectral Remote Sensing of Soil Nitrogen and Its Leaching Risks in a Wheat-Maize Rotation System. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 3956. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243956