Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Instrumental Artifact Correction: the study identified and corrected a significant instrumental artifact in the DARA observations.

- TSI Composite Reliability: the corrected DARA observations were successfully incorporated into the long-term TSI composite time series.

What are the implication of the main findings?

- Improved Long-Term Climate Records: the study ensures that data from the DARA radiometer can be accurately integrated into the long-term Total Solar Irradiance (TSI) climate data record.

- Validation of New Radiometers: the high consistency of the corrected DARA data with the well-established PMOD/WRC composite provides strong validation and confidence in the processing of the observations.

Abstract

Since the late 1970s, satellite missions have monitored Total Solar Irradiance (TSI), providing a long-term record of solar variability. The Digital Absolute Radiometer (DARA), onboard the Chinese Fengyun-3E (FY3E) spacecraft since 4 July 2021, contributes to extending this record. In this study, we evaluate the DARA observations in both World Radiometric Reference (WRR) and International System of Units (SI) scales. We compare these records with those from other instruments on different spacecraft (i.e., VIRGO/PMO6, TSIS-1/TIM) and with the co-located Solar Irradiance Absolute Radiometer (SIAR) on FY3E. A key finding is the identification and correction of an instrumental artifact: an issue in the thermal aperture model, linked to annual satellite maneuvers, repetitively introduced an artificial step of 0.15 ± 0.05 Wm−2 into the TSI measurements. A statistical analysis of the measurements in the SI scale shows that the mean value of the DARA TSI observations is approximately 1359.58 Wm−2 (6-hourly rate), which is lower than the ones recorded by VIRGO/PMO6 (1.82 Wm−2), TSIS-1/TIM (2.90 Wm−2), and SIAR (2.54 Wm−2). We estimate a degradation of ∼49 ppm over 46 months due to the exposure of the instrument to the (Extreme) Ultraviolet (UV/EUV) radiations. Finally, the corrected DARA observations are incorporated into the long-term TSI composite time series. Comparison with the PMOD/WRC composite shows only marginal differences (less than 0.015 Wm−2), confirming the consistency and reliability of including the new TSI product (i.e., JTSIM-DARAv1).

1. Introduction

Total Solar Irradiance (TSI) stands as a critical parameter for comprehending and predicting Earth’s climate system, exerting a pivotal role in establishing the planet’s energy balance of incoming and outgoing electromagnetic radiation. TSI is defined as the radiant solar energy flux per unit area across its entire spectrum at the mean Sun–Earth distance of 1 AU (the astronomical unit). The reliable and continuous monitoring of TSI’s absolute value is indispensable for understanding, reconstructing, and forecasting Earth’s climate. Accurately measuring TSI, however, has proven challenging, requiring radiometers aboard spacecraft that have been providing continuous observations since the late 1970s. Recent missions such as the Solar Radiation and Climate Experiment (SORCE) with the Total Irradiance Monitor (TIM) [1] and the PICARD mission equipped with the SOlar Variability Picard (SOVAP) and PREcision MOnitor Sensor (PREMOS), two absolute radiometers [2], have successfully recorded high-precision TSI values. The Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) for the Variability of Solar Irradiance and Gravity Oscillations (VIRGO) launched in 1995, continues to operate after more than 29 years in space with its VIRGO instrument, which includes the PMO6 [3] and DIARAD [4] radiometers. The SORCE mission provided 17 years of continuous total and spectral solar irradiance data [5], encompassing two successive solar minima (2008–2009 and 2019–2020). Currently, the most accurate TSI measurement is realized with the Total and Spectral Solar Irradiance Sensor 1 (TSIS-1) experiment, which has an uncertainty of ∼100 ppm. Extensive analyses of TSI data from overlapping missions since the end of the 1970s [1,2,6,7,8,9,10,11] have significantly advanced our understanding of solar irradiance variability and its implications for Earth’s climate.

In the 1980s, the Changchun Institute of Optics, Fine Mechanics, and Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CIOMP/CAS), in Changchun (China) initiated the development of TSI radiometers to fulfill the climate monitoring requirements of the China Meteorological Administration (CMA), which demanded absolute accuracy and precision of 0.1 Wm−2 and long-term stability of 0.01 Wm−2/decade [12,13]. Therefore, to further advance the TSI monitoring capabilities, the Joint Total Solar Irradiance Monitor (JTSIM) is based on a new generation of radiometers for long-term TSI monitoring in space. The JTSIM, developed and built by CIOMP/CAS, is embedded into the Chinese Fengyun-3E spacecraft. The Fengyun program, supported by the National Satellite Meteorological Center (NSMC) of China, aims to develop a series of Chinese meteorological spacecraft. The JTSIM comprises the Digital Absolute Radiometer (DARA) from PMOD/WRC and the Solar Irradiance Absolute Radiometer (SIAR) from CIOMP/CAS. These two radiometers are mounted on the same pointing system to measure TSI accurately.

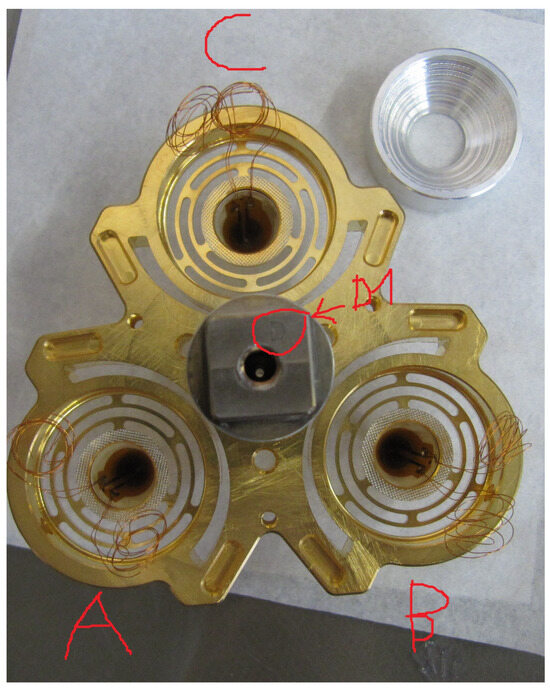

The DARA radiometer features three conical cavities. Each cavity is made of silver (130 μm thick) and coated on the outside with a (5 μm) gold layer to minimize the radiative heat transfer and on the inside with black paint to absorb incident solar radiation. The heat sink is mechanically attached and thermally connected to the front plate of the DARA sensor unit. The whole heat sink structure is machined from one solid piece of aluminum and coated with 5 μm gold (Figure 1). The optical paths are defined by three precision 5 mm tungsten carbide (RGS 50) apertures fixed to the front plate of the instrument and 7.7 mm view-limiting apertures made of aluminum installed in front of the cavities. All three DARA cavities are heated electrically to ∼0.7 K above the temperature of the heat sink by using heater foils glued to the inside of the conical cavities. Approximately 30 mW of heat dissipation is required in each cavity to maintain a 0.7 K temperature rise. The electrical heating in one of the cavities (the reference cavity) is set constant, while in the other two cavities (the measuring and backup cavities) the electrical heating is regulated by individual Proportional–Integral–Derivative (PID) controllers to match the temperature rise of the reference cavity. Whenever the shutter of the measuring or backup cavity is opened, the incident solar radiation heats the cavity, and the PID control loop reduces the electrical heating accordingly to match the temperature rise in the (closed) reference cavity. The difference between electrical power delivered to the measuring cavity in the closed and open shutter states is a measure of the absorbed solar radiation. Solar irradiance is then derived by multiplication of the electrical power by the calibration factor, which is the product of the inverse aperture area and correction factors for optical and thermo-dynamical imperfections. The nominal cavity is operated at a 1 min rate, whereas the backup cavity is operated in sync with the nominal cavity during one orbit every 10 days to track the degradation of the nominal cavity but remains closed otherwise. Cavity B is assigned for nominal, C for backup, and A for reference, respectively. Cavity assignment can be changed freely, e.g., to use the reference channel for degradation tracking of the backup channel. Previous studies [13,14] have already assessed the radiometer’s characteristics at the component level (e.g., shunt resistor, readout electronics), the cavity design and properties (e.g., reflectivity, radiative loss, aperture size, various correction factors), the pre-flight calibration of the first light, and the data reduction from raw observations to Level 1. The SIAR works on a similar concept. It employs an electrically calibrated differential heat-flux transducer with a cavity for efficient radiation absorption [13,15]. The solar radiation is absorbed by the black-coated cavity, and the induced different heat flux between the primary and reference cavity is measured. The electrically calibrated differential heat-flux is used to compute the solar irradiance [13,14]. Figure A1 (Appendix A) shows the DARA and SIAR instruments mounted on the JTSIM platform.

Figure 1.

The DARA heat sink assembly, showing the conical cavities (designated by the letters A, B, and C) connected to their respective heat links (labyrinth structures). The sun sensor will be installed in the central position (D1). Note that this photo was taken before the internal black coating was applied to the cavities.

In this study, we focus on the irradiance measurements and the time–frequency analysis of the TSI time series from the first light (18th of August 2021) to the 4th of April 2025. The observed solar features are compared with other TSI products recorded by other active missions (i.e., VIRGO/SOHO or TSIS-1/TIM). The DARA TSI measurement is expressed in the World Radiometric Reference (WRR) scale, which is a conventional scale established by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) in 1977 and maintained by the Physikalisch-Meteorologisches Observatorium Davos—World Radiation Center (PMOD/WRC) in Switzerland. The DARA TSI readings are offset by −4.63 ± 4.90 Wm−2 (k = 2) if the WRR-to-SI ratio from [16] is applied. We use this conversion to the International System of Units (SI) in order to compare all the instruments with the same scale. Moreover, we include the new product into the so-called TSI composite time series, incorporating all the observations available recorded by successive space instruments spanning four decades. As all satellite observations are limited in time, creating composites is a key aspect to the investigation of TSI fluctuations over several decades. Merging all these observations is a difficult exercise with both a scientific and a statistical challenge [17]. Various algorithms have produced the TSI composite time series either without [18,19,20] or with modeling the stochastic noise properties [17,21]. A comprehensive discussion of the robustness of these various methodologies is out of the scope of the presented work. Readers can refer to [17,21,22,23]. Here, we statistically compare the characteristics of TSI composite time series built using either the new DARA product or the SIAR observations against other available datasets.

The next section provides a short summary of the past and currently active radiometers onboard spacecrafts together with the released TSI datasets. Section 3 focuses on the new TSI products at various data rates (i.e., minute, 6-hourly, and daily) and the comparison with TSI observations recorded by some currently active radiometers. We perform a time–frequency statistical analysis in order to understand the various noise backgrounds (i.e., solar noise, instrumental artifacts) influencing the data. We also discuss the influence of the degradation of the radiometer due to long exposure to UV/EUV light. The last section, Section 4, provides the integration of the DARA TSI product (daily rate) within the TSI composite time series.

2. Description of the TSI Missions over the Past 45 Years

Table 1 displays the instruments and the processing centers providing the observations relative to the various missions past and present. The data processing, including corrections for all a priori known influences such as the distance from the sun (normalized to 1 AU), radial velocity of the sun, and thermal, optical, and electrical corrections, is usually implemented by each processing center, leading to Level 1 data. Most of these instruments observe on a daily basis, with occasional interruptions. Usually, one to three of them operate simultaneously, although some days are devoid of observations. Note that PMODv21a (also called PMO6v8) is the latest VIRGO/SOHO dataset released in March 2021 by PMOD using software described in [24]. PREMOS (v1) is the released version described in [2]. The Earth Radiation Budget Experiment (ERBE)/ERBS and HF/NIMBUS-7 Earth radiation budget (ERB) datasets are retrieved from the PMOD archive, with the corrections made by C. Fröhlich, which are explained in [25]. Note that refs. [18,26] provide information on the datasets from the Active Cavity Radiometer Irradiance Monitor (ACRIM) instrument series. This includes data from ACRIM I on the Solar Maximum Mission (SMM), ACRIM II on the Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite (UARS), and ACRIM III on the ACRIMSAT mission. We have not included the previous test missions using a similar radiometer to the FY3E/JTSIM/SIAR onboard FY3A/B/C satellites. For a comprehensive overview, the reader can refer to [12]. The Compact Lightweight Absolute radiometer (CLARA) on the NorSat-1 Norwegian satellite is described in [27].

Table 1.

Overview of various available TSI datasets including the start and end dates for each mission and the latest version released by the various centers. * means that the SIAR dataset used in this study ends in November 2024. The DARA dataset ends in April 2025. active means that the instrument is still operating.

3. Data Analysis

This section focuses mostly on the time–frequency analysis of the observations recorded by the DARA and some comparisons with other TSI products at different rates (i.e., daily, 6-hourly). The second subsection provides the analysis of the degradation of the observations recorded by the nominal cavity due to the long exposure to UV/EUV.

3.1. Time–Frequency Analysis

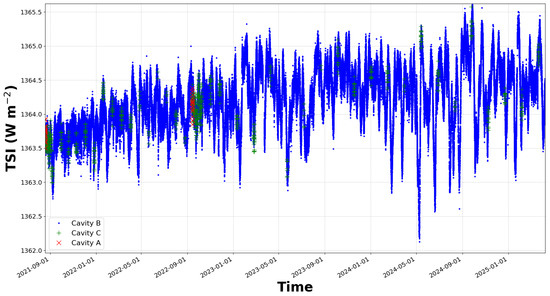

The first light values have been re-evaluated due to continuous refinements in our observation modeling and data filtering since the mission began. These new values, therefore, differ slightly from those in previous publications [14,28] that used older data products. The first light took place on 18 August 2021 (01 h 22 min UTC) for DARA at 1363.76 ± 0.05 Wm−2 for cavity B. Cavity A recorded the first TSI value at 1363.88 ± 0.12 Wm−2 at 13 h 12 min UTC and 1363.71 ± 0.06 Wm−2 on cavity C at 04 h 56 min UTC. All these values are in WRR scale. In the SI scale, the values are equal to 1359.24 Wm−2, 1359.13

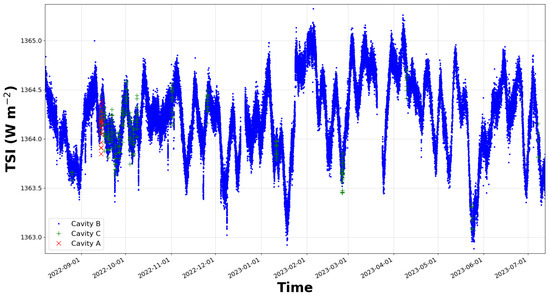

Wm−2, and 1359.08 Wm−2 for cavities A, B and C respectively. Figure 2 shows the recorded TSI observations (WRR scale) for channel B (blue), C (green), and A (red). To ensure data quality and remove potential outliers, the time series is filtered using data from the onboard sun tracker, selecting only those observations where the instrument is properly aligned with the sun. The resulting time series, therefore, shows a high degree of consistency. The clear upward trend since July 2021 corresponds to the rising solar activity in the solar cycle 25, which follows the solar minimum in December 2019 (the end of cycle 24). For further detail, a zoom-in of this figure is available in Appendix A (see Figure A3).

Figure 2.

TSI observations in WRR scale recorded by the DARA from the various cavities: channel B (blue), channel C (green), and A (red). Channel B operates at a 1 min. rate, C at a day rate, and A irregularly as the reference cavity.

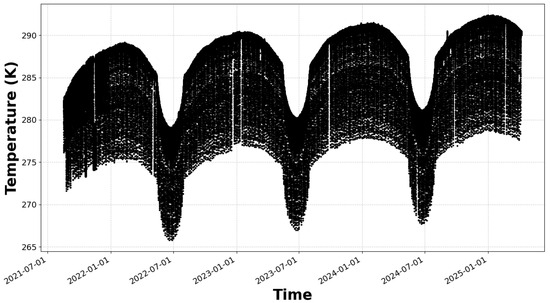

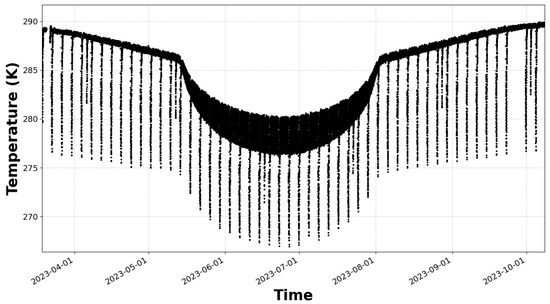

A specific feature of this mission is the rotation of the JTSIM platform every 4 days in order to perform the Deep Space (DS) measurements, which were only used during the commissioning phase in order to evaluate mainly the DS corrections [13,14]. During these measurements, the cavity of the radiometers exchanges radiation with a different thermal background in the open-shutter state, when the cavity radiates to deep space, compared to the closed-shutter state when the cavity’s thermal emission is reflected by the (gold-coated) backside of the shutter. The DS correction is then required to compensate the thermal background effect, which is linked with the geometry of the cavity and the electronics of the instruments [13,27]. The platform movement is hard-coded in the spacecraft software system and can be neither interrupted nor overwritten. During this maneuver, the cavity temperature variations look like a seesaw dropping between 6 K and 14 K over a period between 1 h 30 and 5 h. Figure 3 and Figure A2 (see Appendix A) display the cavity temperature of the nominal cavity B with an emphasis on the large excursions. These variations are artificial due to the DS measurements and the satellite maneuvers. In particular, the temperatures decrease every year from May to August and then increase again. This specific feature results from a series of small maneuvers of the satellite to rotate the spacecraft and the solar panels. Note that a correction must be applied to the data to account for the thermal expansion or contraction of the precision aperture area (i.e., thermal aperture correction). The thermal coefficient of the aperture area is estimated to be 12 ppm per degree Celsius. This aperture-area temperature-correction factor is calculated as a function of the DARA cavity temperature [13].

Figure 3.

Cavity temperature in Kelvin (K) for the nominal cavity ( cavity B). Note that the temperature fluctuates due to the deep space measurements and maneuvers of the satellite.

We have identified an issue in the thermal aperture correction model, which fails to fully account for variations in TSI measurements caused by annual satellite maneuvers between May and end of August every year. These events introduce an artificial step in the data, estimated at approximately 0.15 ± 0.05 Wm−2. The offsets were computed by modeling the data as discrete steps and fitting them using a least-squares algorithm. To correct for this artifact, we apply these adjustments on 30 June each year, coinciding with the middle of the maneuver period. This correction is essential for isolating the true degradation signal driven by long-term UV/EUV exposure. Without it, the underlying degradation cannot be accurately assessed. It is worth emphasizing that both channels (nominal and backup) are affected by these artifacts. In the subsequent sections, these corrections are applied except where explicitly stated otherwise.

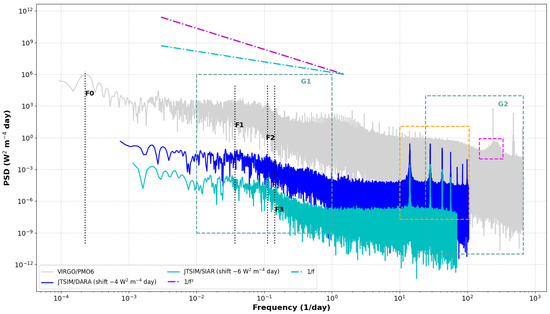

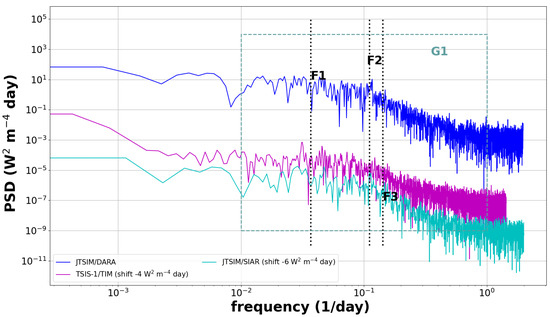

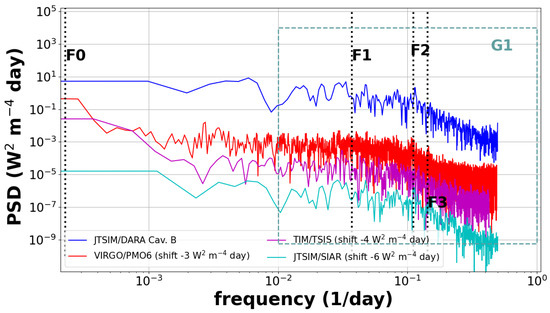

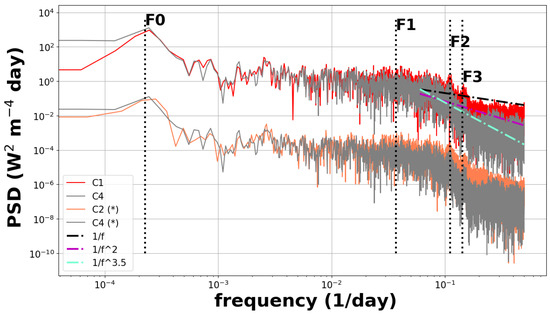

To further study the signals and processes recorded in the DARA observations, we perform a frequency analysis, as displayed in Figure 4. Previous works, e.g., [21,29,30,31], have analysed the Power Spectral Density (PSD) of the solar noise. This noise results from photospheric activity associated with granules varying at different timescales over a few hours (e.g., sunspots) to a decade (e.g., solar cycle), which generate fluctuations in the recorded irradiance values [31].

Figure 4.

Power spectrum analysis of the DARA 1 min rate TSI time series using the Welch’s method (blue) and SIAR (cyan). The gray PSD is the 1 min data rate of the observations recorded by the PMO6 radiometer onboard the SOHO/VIRGO mission. We emphasize the frequency band G1 at [1–100] days, G2 at [1–60] min, and the P-modes (dashed purple box). The orange box underlines the frequencies at 101 min and the subharmonics. The black vertical dotted lines correspond to years (F0), 27 days (F1), 9 days (F2), and 7 days (F3). The dashed line is the power-law model when varying the exponent (shown for context).

Note that in order to address the data gaps occurring during orbital eclipses, we did not apply any interpolation or artificial data gap filling for the minute-rate time series. Instead, we use the Lomb–Scargle periodogram to analyse the observations. The time series with a lower rate (i.e., 6-hourly and daily rate) have a very low number of gaps; therefore, the PSD is computed using Welch’s method with a Hann window, 10% overlap, and detrending to minimize spectral leakage.

In the PSD of the the minute-rate time series, we look at two frequency bands: G1 at [1–100] days and G2 at [1–60] min. The G1 frequency group is generally associated with the solar activity with events varying over days or longer [17,21,30,31]. The vertical dotted lines (black) F0, F1, F2, and F3 are associated with the frequencies at 11.5 years, 27 days, 9 days, and 7 days, respectively. These frequencies correspond to the 11.5 year solar cycle, the solar rotation (27 days), and its third and fourth harmonics (9, 7 days). Below 1 Hz/day, we observe photospheric activity associated with P-modes ( ∼5 min), granulation (ranging from ∼6 to 16 min), meso-granulation (from ∼16 to 166 min), and supergranulation (extending up to 1 day) [29,30]. The DARA and SIAR frequency spectrums display peaks at min and sub harmonics up to the seventh order (i.e., min, min, min, min, min, min). All these frequencies are undoubtably related to the signal from the spacecraft’s own revolution, which is 101 min. The first four harmonics are exactly matching between the PSD of SIAR and DARA. As the SIAR dataset is shorter and contain more gaps, presumably due to a postprocessing filtering, the rate is lower than DARA (i.e., 13 min and 19 min for DARA and SIAR, respectively). Moving to higher frequencies (periods of 5 min and below), this regime is where one would expect to find signals from solar P-modes, which have their dominant periods clustered around 5 min as seen clearly on the VIRGO/PMO6 PSD. Previous works [29,30] demonstrate that in the granulation, the meso-granulation, and super-granulation no activity can be detected in the VIRGO/PMO6 spectrum due to the level of the signal-to-noise ratio. At high frequency, separating the contributions of frequencies arising from the satellite’s orbital motion, different solar rotation modes, and instrumental effects (e.g., cavity temperature variations) remains a significant challenge [31].

In addition, the SIAR, DARA, and VIRGO/PM06 frequency spectra exhibit a similar shape and slope (i.e., decreasing approximately in a power- aw between and ) in the G1 frequency band. As discussed in [21], the slope of the frequency spectrum is linked to colored noise (power-law noise), suggesting that VIRGO/PMO6, SIAR, and DARA observations contain similar stochastic noise processes (i.e., white and power-law noises). The PSDs of the 6-hourly and daily DARA observation rates exhibit similar shapes and are discussed in Appendix A (see Figure A4 and Figure A5).

Table 2 summarizes the statistics derived from observations recorded by DARA, VIRGO/PMO6, TSIS-1/TIM, and SIAR at different sampling rates (minute, 6-hourly, and daily). For reference, the DARA and VIRGO/PMO6 data are presented on the WRR scale prior to their conversion to the SI scale, while the SIAR data are provided directly in the SI scale. The DARA observations have been corrected for UV/EUV degradation. At the 6-hourly sampling rate, the mean value of DARA in the SI scale is lower than that of VIRGO/PMO6 by approximately 1.82 Wm−2 (or 0.13%), is lower than SIAR by about 2.54 Wm−2 (or 0.18%), and is also lower than TSIS-1/TIM by roughly 2.90 Wm−2 (or 0.21%). Comparable differences are observed for the datasets sampled at the minute and daily rates. Similar result can be obtained for the observations in WRR scale between DARA and VIRGO/PMO6.

Table 2.

Statistics —mean (μ) ± uncertainties (σ) in Wm−2—for various active missions estimated for the period 18 August 2021–4 April 2025. (*) means that we use the hourly product for VIRGO/PMO6. The sampling rate of the TSIS-1/TIM observations is only available in 6-hourly and daily products. The table is divided in two sections corresponding to the statistics estimated on the observations converted in WRR or SI scale.

3.2. Degradation Correction

The degradation of the radiometer is caused by long-term sensitivity changes of the sensor and/or drifts of the electrical characteristics. The degradation is assessed a posteriori based on the relative change of the nominal channel (cavity B) with respect to the occasionally operated back-up channel (cavity C). The change in sensitivity is generally related to the changes in the black coating of the cavity or the loss of glossiness of specular paint. Both effects are thought to be caused by the UV and EUV radiation. The phenomena has been extensively studied over the past three decades, leading to the development of various correction methods [24,32,33]. Each TSI dataset in Table 1 consists of measurements from a continuously operated active channel and at least one backup channel, which allows scientists to assess the degradation by comparing their readings. Recently, ref. [24] introduced a machine learning (ML) algorithm that models degradation as a smooth monotonic decrease without requiring filtering or pre-processing. The method relies on three assumptions: (i) the phenomenon is a function of UV/EUV exposure time to solar radiation; (ii) all channels start with no degradation; and (iii) the degradation curve is monotonically decreasing. This algorithm has been applied to correct observations from the VIRGO/PMO6 radiometer (channel A) and is now used for the DARA nominal cavity (channel B).

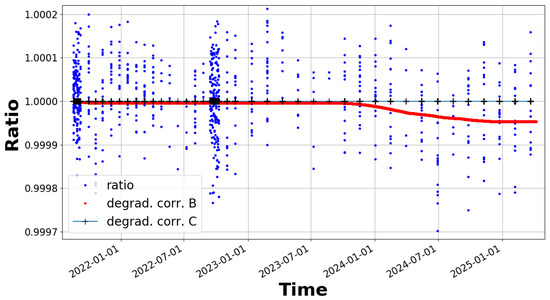

Figure 5 displays the ratio of observations from the nominal channel (B) to the backup channel (C) over time, along with the degradation curve. This figure illustrates that the estimated degradation for channel B, based on the ML correction, follows a smooth monotonic function. Notably, and in contrast to earlier observations from VIRGO/PMO6 and PREMOS/PMO6 [2,24,34], no early increase phenomenon [35] is observed in this ratio. We cannot totally exclude that the early increase phenomenon, which should last less than 10 exposure days ( e.g., 5 exposure days for the VIRGO/PMO6 [24]), could be somehow masked by the instrumental noise. We observe in Figure 5 that the degradation does not really start before mission days 700 (1 January 2024) with a smooth decreasing curve which continues until mission days 1250 (205-02-01) and totaling a degradation of ∼49 ppm. Overall, this correction is relatively small for a period covering 46 months within the scatter of the observations of around ±500 ppm.

Figure 5.

A comparison of degradation between DARA’s nominal channel (cavity B) and backup channel (cavity C) as a function of time (UTC). The blue dots show the ratio of their respective observations (cavity B/cavity C). The degradation curve for cavity B is shown as a red line. The degradation for cavity C is plotted as black crosses, indicating no significant degradation over this period.

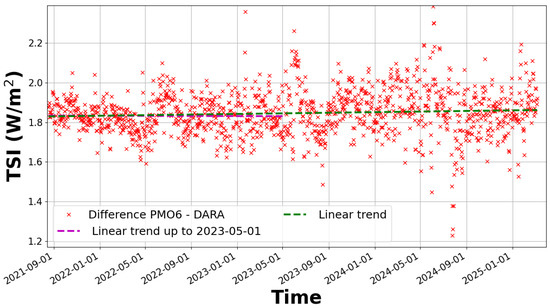

Lastly, Figure 6 illustrates the difference between the daily PMO6v8 product, the degradation-corrected observations from the VIRGO/PMO6 radiometer, and the degradation-corrected DARA TSI time series. To showcase the stability of the instrument relative to the PMO6v8 product, we analyze the linear trends over two distinct intervals. The purple curve stops in early 2023, and its slope is small (∼2 ppm/yr (i.e., below 0.005 Wm−2.yr−1), whereas the green curve fits all the available data until April 2025 with a larger slope of (∼6 ppm/yr). This slight drift between the observations recorded by the two instruments is marginal. The divergence between the two trends corresponds to a drift of less than 0.01 Wm−2yr−1, a marginal difference that confirms the instrument’s high stability over the recording period.

Figure 6.

Difference between the daily PMO6v8 product and the degradation-corrected TSI time series. Two linear trends are displayed: the purple curve stops in early 2023, whereas the green curve fits all the available data until April 2025.

4. TSI Composite Including the JTSIM-DARA Product

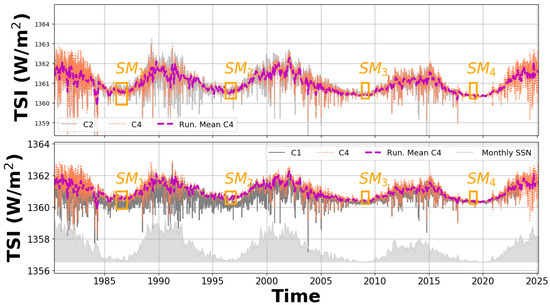

The TSI composite time series, constructed from satellite data since the late 1970s, is analyzed to assess the integration of the DARA daily rate dataset. This study follows a time–frequency analysis similar to the approaches of [17,21]. The algorithm generating the TSI composite time series, developed by [21], is based on the former PMOD/WRC TSI composite [25]. In this work, the previous time series released by [17], [25], and [21] are called, respectively, Composite 1 (C1), Composite 2 (C2), and Composite 3 (C3). The product when including the daily DARA product is called Composite 4 (C4), and with the SIAR product, it is Composite 5 (C5). Composite 6 (C6) is the latest TSI time series published by [36] and updated by [37]. The results are presented in Table 3. A comparative analysis of solar minima reveals discrepancies among the composites, particularly in the difference between Solar Cycles and (). Notably, C1 exhibits a positive difference for this transition, whereas C2, C3, C4, and C5 show negative or null trends, an issue previously discussed by [21] and linked to processing differences in early TSI observations. Despite these variations, C3, C4, and C5 show minimal differences at the solar minima level, with deviations below 0.01 Wm−2, indicating that the inclusion of the DARA or SIAR datasets does not significantly alter the stability of the composite.

Table 3.

Estimation of TSI at solar minimum (Minimum) over the last 45 years from TSI time series (mean and standard deviation ) released by [17] (C1), by [25] (C2), by [21] Composite 3 (C3), and by [36] (C6). The new TSI composite including the daily JTSIM-DARAv1 product and the daily sampling of the SIAR observations is abbreviated to (C4) and (C5). The difference in irradiance between solar minima (SM) from consecutive solar cycles (e.g., ) is also displayed with the uncertainties (bold text).

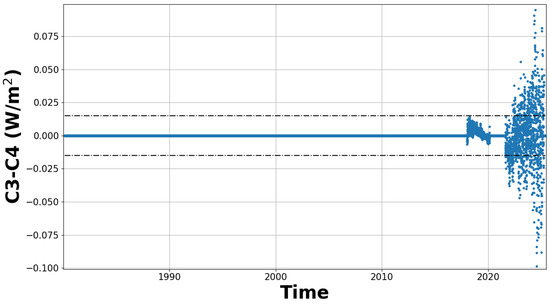

Figure 7 presents the TSI composite time series C3 and C4. The corresponding power spectral density (PSD) in Appendix A—shown in Figure A6—compares the frequency spectra of C1, C2, and C4. The analysis reveals that their power spectra are very similar, indicating that all three series contain comparable stochastic noise with similar amplitude. The difference between C3 and C4 is shown in Figure A7, also in Appendix A. Approximately 90 % of the data points fall within ±0.015 Wm−2, with a mean value of about 0.0001 Wm−2 and an uncertainty of 0.008 Wm−2. The large scatter of points (below ±0.08 Wm−2) arises from incorporating JTSIM-DARA observations into the fusion with TSIS-1/TIM and VIRGO/SOHO data. A slight discrepancy between the two time series is also visible from 2018 to 2020, which stems from the method used to construct the TSI composite when integrating the additional dataset.

Figure 7.

New composite (C4, orange) based on merging 45 years of TSI measurements. For comparison, C2 [25] and C1 [17] are also shown (grey line). A 30-day running mean of C4 is shown as a yellow/purple dashed line. The orange boxes are associated with the solar minima (SM) for each solar cycle described in Table 3. Note that the monthly sunspot number is also included as an empirical scale to provide context for solar activity.

5. Conclusions

This work focuses on a comprehensive analysis of TSI observations recorded by the DARA instrument onboard the FY3E spacecraft. The study encompasses various sampling rates, i.e., minute, 6-hourly, and daily data, and includes comparisons with other active radiometers (i.e., VIRGO/PMO6 and TSIS-1/TIM) together with the SIAR, which is also mounted on the same platform (JTSIM) as the DARA. We have identified an issue in the thermal aperture correction model, which fails to fully account for variations in TSI measurements caused by these satellite maneuvers each year and introducing an artificial step of 0.15 ± 0.05 Wm−2 between May and August every year. We have modeled and corrected the data accordingly. The phenomenon inducing these step changes is still under investigation, and further improvements are expected. This correction is essential for isolating the true degradation signal driven by long-term UV/EUV exposure. Our study of the differences between the observations recorded by VIRGO/PMO6 and DARA shows that there is a marginal slope of ∼6 ppm/yr. Moreover, we only had access to the filtered and degradation-corrected SIAR data for this study; therefore, we cannot conclude on the sensitivity of the SIAR to in-orbit maneuvers. The inter-comparison between instruments reveals that in SI scale, the DARA mean value is below the one estimated for the observations recorded by the VIRGO/PMO6 (1.82 Wm−2 at the 6-hourly rate), TSIS-1/TIM (2.90 Wm−2 at the 6-hourly rate), and SIAR (2.54 Wm−2 at the 6-hourly rate). A similar conclusion can be drawn for the observations in WRR scale between DARA and VIRGO/PMO6. Our study also discusses the evaluation of degradation caused by exposure to UV/EUV radiations in space, employing the algorithm developed by [24]. The results show a degradation of ∼49 ppm which is relatively low for a period covering 46 months since the spacecraft launch.

Finally, the DARA or the SIAR observations have been inserted in the TSI composite time series using the algorithm developed by [21]. The TSI composite gathers all the TSI observations recorded since the late 1970s. A comparison with the TSI composite released regularly by PMOD/WRC [38] showcases only marginal differences (i.e., below 0.015 Wm−2). This result demonstrates the overall consistency and reliability of including the JTSIM-DARAv1 product into the composite. Looking ahead, future releases of the TSI composite time series by the PMOD team will consistently include the JTSIM-DARAv1 product, ensuring a robust and continuous record for the scientific community.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.-P.M., W.F. (Wolfgang Finsterle), P.Z. (Ping Zhu), and M.H.; methodology, J.-P.M., W.F. (Wolfgang Finsterle), P.Z. (Ping Zhu), and M.H.; software, J.-P.M., W.F. (Wolfgang Finsterle), P.Z. (Ping Zhu), and M.H.; validation, all co-authors; formal analysis, J.-P.M., W.F. (Wolfgang Finsterle), P.Z. (Ping Zhu), and M.H.; investigation, J.-P.M., W.F. (Wolfgang Finsterle), P.Z. (Ping Zhu), and M.H.; resources, J.-P.M., W.F. (Wolfgang Finsterle), and M.H.; data curation, J.-P.M., D.W., D.Y., J.Q., and X.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, J.-P.M., W.F. (Wolfgang Finsterle), D.P., S.K., and M.H.; writing—review and editing, J.-P.M., W.F. (Wolfgang Finsterle), and M.H.; visualization, D.P.; supervision, J.-P.M., W.F. (Wolfgang Finsterle), W.F. (Wei Fang), P.Z. (Ping Zhu), and M.H.; project administration, W.F. (Wolfgang Finsterle), W.F. (Wei Fang), and P.Z. (Ping Zhu); funding acquisition, J.-P.M. and W.F. (Wolfgang Finsterle) All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

J.-P. Montillet, W. Finsterle, and M. Haberreiter gratefully acknowledge support from the Karbacher-Funds. J.-P. Montillet also thanks the Swiss Space Office for support via the PRODEX funds supporting the making of the DARA dataset. D. Wu, X. Ye, P. Zhu, D. Yang, W. Fang, J. Qi, and P. Zhang acknowledge the National Nature Science Foundation of China (Grant Number 41974207) and CIOMP International Fund. This research was partially supported by the International Space Science Institute (ISSI) in Bern, through ISSI International Team project No.500 (Towards Determining the Earth Energy Imbalance from Space).

Data Availability Statement

The composite C3 can be obtained from the open archive repository www.astromat.org [38,39,40]. It is also presented on www.pmodwrc.ch/en/?s=TSI+Composite (last accessed on 9 June 2025) for additional information. The TSI composite C1 is available for downloading at http://www.issibern.ch/teams/solarirradiance (last accessed 10 on November 2024). The composite C6 is available at https://www.sidc.be/users/stevend/ (last accessed on 9 June 2025). The data related to the monthly/daily mean sunspot numbers are retrieved from http://www.sidc.be/silso/datafiles (last accessed on 30 May 2025). TIM /SORCE, TCTE/TIM, and >TSIS-1/TIM time series are downloaded from https://lasp.colorado.edu/home/sorce/data/tsi-data (last accessed on 2 June 2025). PREMOS (v1) can be accessed at http://idoc-picard.ias.u-psud.fr/sitools/client-user/Picard/project-index.html (last accessed on 10 November 2024). PMODv21a (also called PMODv8) is available at https://www.pmodwrc.ch/en/research-development/space/soho/ (last accessed on 9 June 2025). The dataset has also been recently added to the open archive repository www.astromat.org (accessed on) [41]. The SIAR data (daily rate) will be available through the Fengyun satellite data center https://satellite.nsmc.org.cn/ (accessed on). For this study, access to the minute-resolution SIAR data was limited, since high-frequency observations from Fengyun-3E (FY-3E) are not routinely distributed due to technical and administrative constraints. Consequently, these data were obtained only through direct collaboration with the satellite operator. The DARA 6-hourly product (JTSIM-DARAv1) is released either via the PMOD website (https://www.pmodwrc.ch/en/research-development/space/fy-3e/ (accessed on) —see link to the ftp server) or via the open archive repository www.astromat.org (accessed on). Note that the product used in this study [42] provides two separate TSI products, one corrected and one uncorrected.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the help of J. Vermeirssen in the development of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A. Additional Figures and Discussions

Figure A1 displays DARA and SIAR fixed on the JTSIM platform. Figure A2 and Figure A3 are a zoom-in of the time series of the cavity temperature (cavity B) and the TSI time series, respectively. Figure A4 and Figure A5 are the PSD of the 6-hourly and daily DARA product.

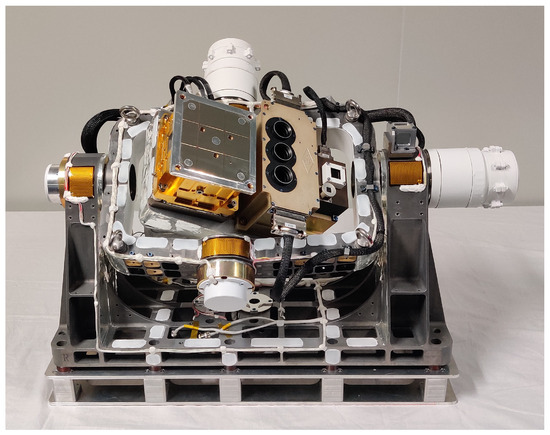

Figure A1.

Both DARA and SIAR are mounted on the JTSIM platform. The two instruments are visually distinct: DARA has a square shape with its three cavities arranged in a star pattern, while SIAR’s three cavities are arranged in a single line.

Figure A2.

Cavity temperature from nominal cavity (cavity B) in Kelvin (K). Zoom on one of the periods (April 2023–October 2023) where the temperature decreased due to the satellite maneuver.

Figure A3.

A zoom-in of the TSI observations recorded by DARA in WRR scale: channel B (blue), channel C (green), and A (red).

Figure A4.

Power spectrum analysis of the DARA 6-hourly rate TSI time series using Welch’s method. We also display the 6-hourly data rate of the observations recorded by the SIAR and TSIS-1/TIM radiometers. We emphasize the frequency band G1 at [1–100] days. The black vertical dotted lines correspond to 27 days (F1), 9 days (F2), and 7 days (F3) (shown for context).

Figure A5.

Power spectrum density of the DARA daily rate TSI time series using the Welch’s method. We also display the daily data rate of the observations recorded by the VIRGO/PMO6, TSIS-1/TIM, and SIAR radiometers. We emphasize the frequency band G1 at [1–100] days. The black vertical dotted lines correspond to 11.5 years (F0), 27 days (F1), 9 days (F2), and 7 days (F3) (shown for context).

Figure A6.

Power spectrum density of TSI C1 [17], C2 [25], together with the new TSI composite including the JTSIM-DARA product C4. The (*) means that the time series are shifted by rescaling the amplitude by −4 W2 m−4 day in the log–log plot. The dashed lines are the various power-law models when varying the exponent, which are only shown for context. The vertical dotted lines (black) mark the frequencies at 27 (F1 ), 9 (F2), and 7 (F3) days (shown for context).

Figure A7.

Difference between the TSI composite C3 [38] and the time series including the JTSIM-DARA product C4. The horizontal dotted lines show the limit at 0.015 Wm−2.

References

- Kopp, G.; Lawrence, G.; Rottman, G. The Total Irradiance Monitor (TIM): Science Results. Sol. Phys. 2005, 230, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmutz, W.; Fehlmann, A.; Finsterle, W.; Kopp, G.; Thuillier, G. Total solar irradiance measurements with PREMOS/PICARD. Aip Conf. Proc. 2013, 1531, 624–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, C.; Crommelynck, D.; Wehrli, C.; Anklin, M.; Dewitte, S.; Fichot, A.; Finsterle, W.; Jiménez, A.; Lombaerts, M.; Pap, J.M.; et al. In-flight performance of the VIRGO solar irradiance instruments on SOHO. Sol. Phys. 1997, 175, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewitte, S.; Crommelynck, D.; Joukoff, A. Total solar irradiance observations from DIARAD/VIRGO. J. Geophys. Res. 2004b, 109, A02102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, T.N.; Harder, J.W.; Kopp, G.; Snow, M. Solar-cycle variability results from the solar radiation and climate experiment (SORCE) mission. Sol. Phys. 2022, 297, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmutz, W.; Fehlmann, A.; Hülsen, G.; Meindl, P.; Winkler, R.; Thuillier, G.; Blattner, P.; Buisson, F.; Egorova, T.; Finsterle, W.; et al. The PREMOS/PICARD instrument calibration. Metrologia 2009, 46, S202–S206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopp, G.; Lean, J.L. A new, lower value of total solar irradiance: Evidence and climate significance. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011, 38, L01706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, K.L.; Krivova, N.A.; Solanki, S.K. Solar Cycle Variation in Solar Irradiance. Space Sci. Rev. 2014, 136, 137–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopp, G. Science Highlights and Final Updates from 17 Years of Total Solar Irradiance Measurements from the SOlar Radiation and Climate Experiment/Total Irradiance Monitor (SORCE/TIM). Sol. Phys. 2021, 296, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzistergos, T.; Krivova, N.A.; Yeo, K.L. Long-term changes in solar activity and irradiance. J. Atmos. Sol. Terr. Phys. 2023, 252, 106150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzistergos, T. A Discussion of Implausible Total Solar-Irradiance Variations Since 1700. Sol. Phys. 2024, 299, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Zhang, P.; Qiu, H.; Fang, W.; Ye, X.; Yu, P. Analysis of total solar irradiance observed by FY-3C Solar Irradiance Monitor-II. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2015, 60, 2447–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Ye, X.; Finsterle, W.; Gyro, M.; Gander, M.; Oliva, A.R.; Pfiffner, D.; Zhao, Y.; Fang, W. The Fengyun-3E/Joint Total Solar Irradiance Absolute Radiometer: Instrument Design, Characterization, and Calibration. Sol. Phys. 2021, 296, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Ye, X.; Montillet, J.P.; Finsterle, W.; Yang, D.; Duo, W.; Qi, J.; Fang, W.; Zhang, P. The first light from the joint total solar irradiance measurement experiment onboard the FY3-E meteorological satellite. Earth Space Sci. 2025, 12, e2023EA003064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, W.; Gong, C.; Yu, B. Dual cavity inter-compensating absolute radiometer. Opt. Precis. Eng. 2007, 15, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehlmann, A.; Kopp, G.; Schmutz, W.; Winkler, R.; Finsterle, W.; Fox, N. Fourth World Radiometric Reference to SI radiometric scale comparison and implications for on-orbit measurements of the total solar irradiacne. Metrologia 2012, 49, S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudok de Wit, T.; Kopp, G.; Fröhlich, C.; Schöll, M. Methodology to create a new total solar irradiance record: Making a composite out of multiple data records. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017, 44, 1196–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R. Total solar irradiance trend during solar cycles 21 and 22. Science 1997, 277, 1963–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, C.; Lean, J. Solar radiative output and its variability: Evidence and mechanisms. Astron. Astrophys. Rev. 2004, 12, 273–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekaoui, S.; Dewitte, S. Total solar irradiance measurement and modelling during cycle 23. Sol. Phys. 2008, 247, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montillet, J.; Finsterle, W.; Kermarrec, G.; Sikonja, R.; Haberreiter, M.; Schmutz, W.; Dudok de Wit, T. Data Fusion of Total Solar Irradiance Composite Time Series Using 41 Years of Satellite Measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2022, 127, e2021JD036146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scafetta, N.; Willson, R.C. Comparison of Decadal Trends among Total Solar Irradiance Composites of Satellite Observations. Adv. Astron. 2019, 2019, 1214896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amdur, T.; Huybers, P. A Bayesian Model for Inferring Total Solar Irradiance From Proxies and Direct Observations: Application to the ACRIM Gap. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2023, 128, e2023JD038941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finsterle, W.; Montillet, J.; Schmutz, W.; Sikonja, R.; Kolar, L.; Treven, L. The total solar irradiance during the recent solar minimum period measured by SOHO/VIRGO. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, C. Solar irradiance variability since 1978. Space Sci. Rev. 2006, 125, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R. ACRIM3 and the Total Solar Irradiance database. Astrophys. Space Sci. 2014, 352, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, B.; Andersen, B.; Beattie, A.; Finsterle, W.; Kopp, G.; Pfiffner, D.; Schmutz, W. First TSI results and status report of the CLARA/NorSat-1 solar absolute radiometer. In Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union: Astronomy in Focus; Lago, M.T., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; Volume 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montillet, J.P.; Finsterle, W.; Haberreiter, M.; Schmutz, W.; Pfiffner, D.; Koller, S.; Gyo, M.; Fang, W.; Ye, X.; Yang, D.; et al. Solar Irradiance monitored by DARA/JTSIM: First light observations. In Proceedings of the EGU General Assembly, Vienna, Austria, 23–27 May 2022; Volume EGU22-616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, B.N.; Leifsen, T.; Toutain, T. Solar noise simulations in irradiance. Sol. Phys. 1994, 152, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, C.; Andersen, B.; Appourchaux, T.; Berthomieu, G.; Crommelynck, D.A.; Domingo, V.; Fichot, A.; Finsterle, W.; Gómez, M.F.; Gough, D.; et al. First Results from VIRGO, the Experiment for Helioseismology and Solar Irradiance monitoring on SOHO. Sol. Phys. 1997, 170, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, A.; Solanki, S.; Krivova, N.; Cameron, R.; Yeo, K.; Schmutz, W. The nature of solar brightness variations. Nat. Astron. 2017, 1, 612–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, C. Long-term Behaviour of Space Radiometers. Metrologia 2003, 40, 560–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopp, G. Solar irradiance measurements. Living Rev. Sol. Phys. 2025, 22, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, W.T.; Schmutz, W.; Fehlmann, A.; Finsterle, W.; Walter, B. Assessing the beginning to end-of-mission sensitivity change of the PREcision MOnitor Sensor total solar irradiance radiometer (PREMOS/PICARD). J. Space Weather Space Clim. 2016, 6, A32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remesal Oliva, A. Understanding and Improving the Cavity Absorptance for Space TSI Radiometers. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Zurich, Zürich, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dewitte, S.; Nevens, S. The Total Solar Irradiance Climate Data Record. Astrophys. J. 2016, 830, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewitte, S.; Cornelis, J.; Meftah, M. Centennial Total Solar Irradiance Variation. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montillet, J.; Finsterle, W.; Schmutz, W.; Haberreiter, M.; Dudok de Wit, T.; Kermarrec, G.; Sikonja, R. Composite PMOD Data Fusion—Updated December 2024; [Dataset]; Interdisciplinary Earth Data Alliance (IEDA): Palisades, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montillet, J.; Finsterle, W.; Schmutz, W.; Haberreiter, M.; Dudok de Wit, T.; Kermarrec, G.; Sikonja, R. Composite PMOD Data Fusion; [Dataset]; Interdisciplinary Earth Data Alliance (IEDA): Palisades, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Montillet, J.; Finsterle, W.; Schmutz, W.; Haberreiter, M.; Dudok de Wit, T.; Kermarrec, G.; Sikonja, R. Composite PMOD Data Fusion—Updated April 2023; [Dataset]; Interdisciplinary Earth Data Alliance (IEDA): Palisades, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montillet, J.; Finsterle, W. PMO6v8—Total Solar Irradiance Dataset from VIRGO/PMO6—12/2024; [Dataset]; Interdisciplinary Earth Data Alliance (IEDA): Palisades, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montillet, J.; Finsterle, W. Total Solar Irradiance Recorded by the FY3E/DARA-JTSIM Radiometer—New Version August 2025, Version 1.0. 2025. Available online: https://gkhub.earthobservations.org/records/0fqaw-vcw02 (accessed on 29 October 2025). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).