Vertical Characteristics of an Ozone Pollution Episode in Hong Kong Under the Typhoon Mawar—A Case Study

Highlights

- Transportation and accumulation processes of ozone and aerosols were revealed by High-resolution Differential Absorption Lidar.

- An ozone episode was jointly driven by the Western Pacific Subtropical High and the non-landfall Typhoon Mawar.

- This study elucidates a coupled mechanism driving coastal ozone pollution: the synergy among meteorology, local photochemistry, and regional transport.

- It provides key insights for regional air quality management in coastal cities of southeastern China.

- It quantitatively analyzes the vertical distribution characteristics of ozone pollution in the lower troposphere during a specific pollution episode.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

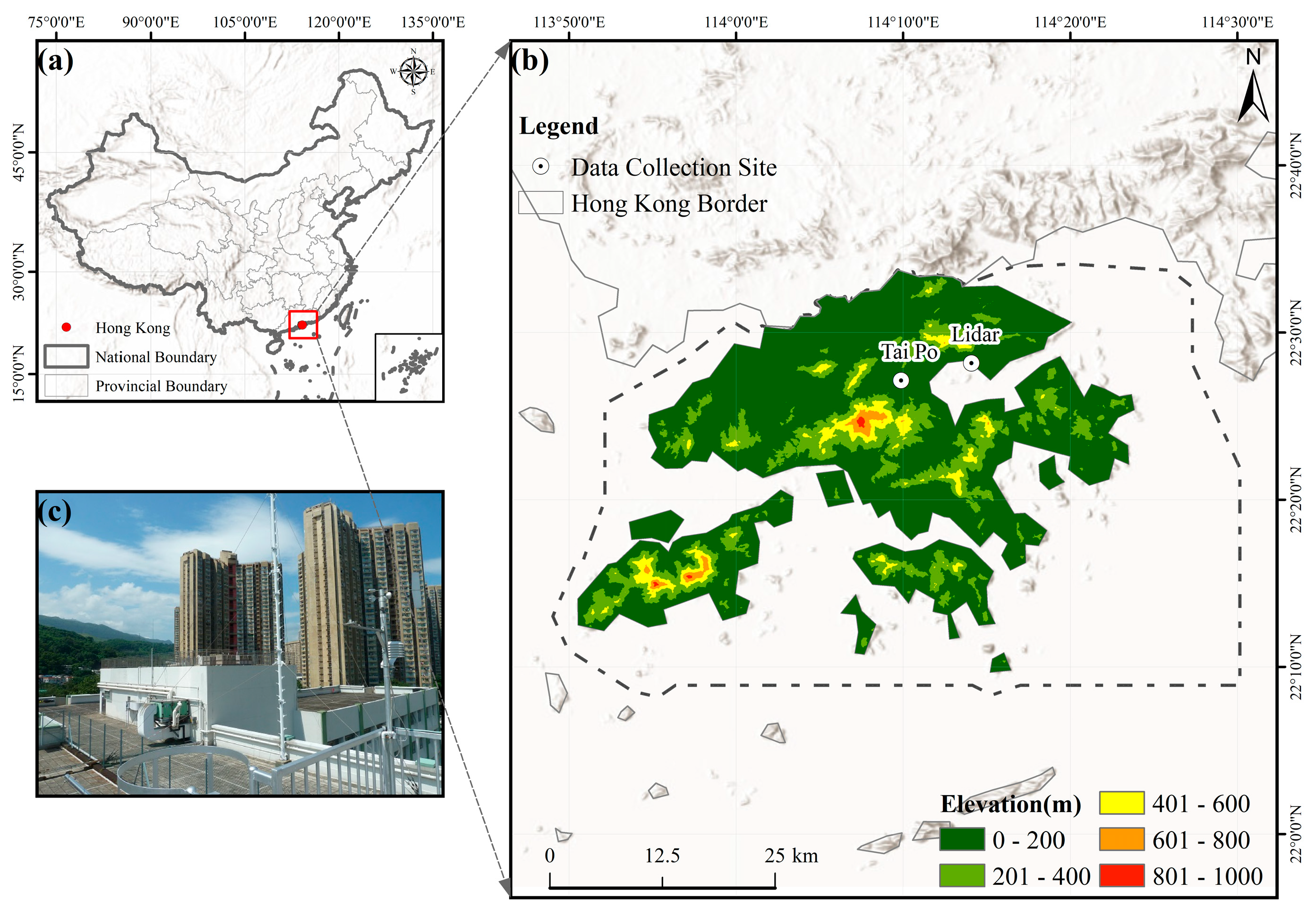

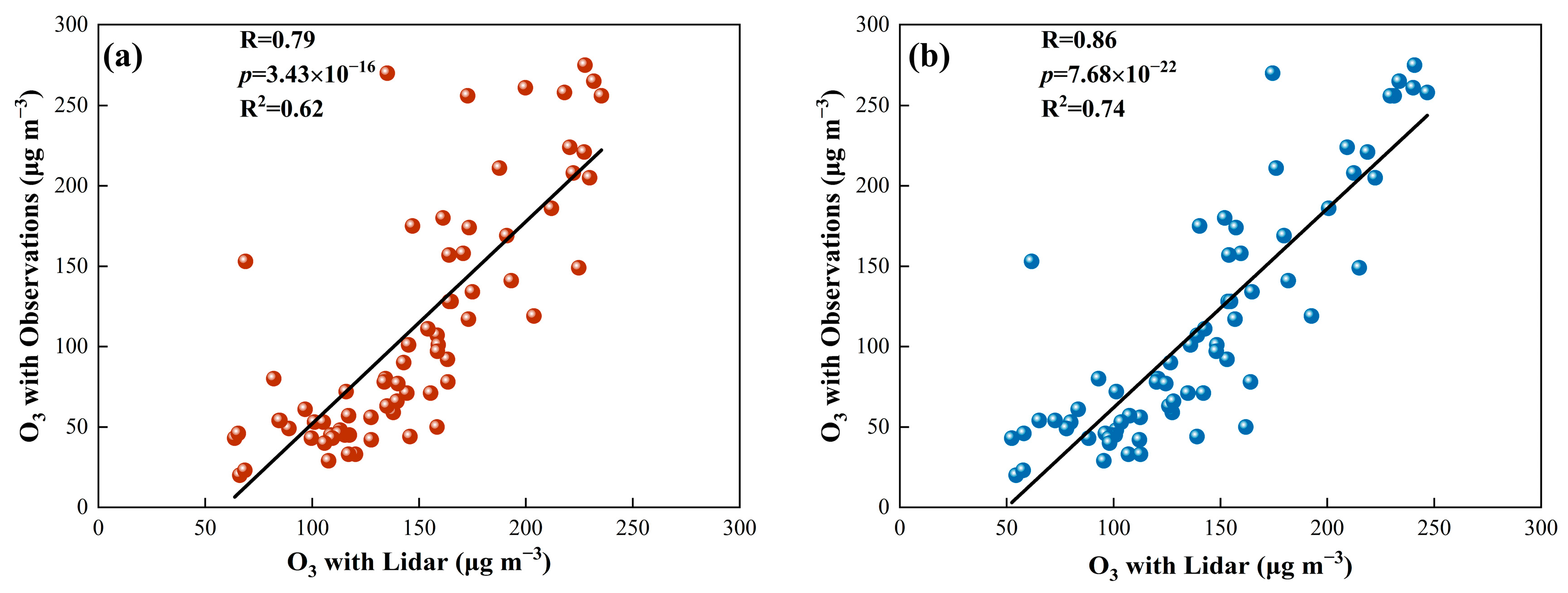

2.1. Lidar System

2.2. Other Supporting Datasets

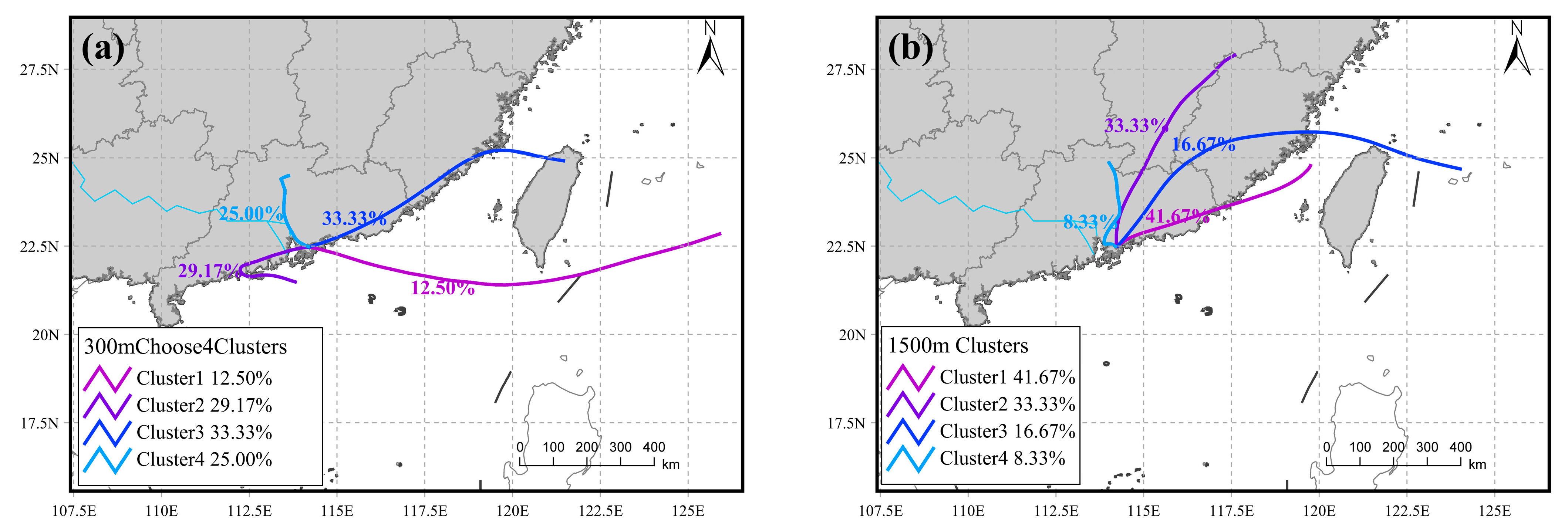

2.3. Backward Trajectory and Cluster Analysis

3. Results

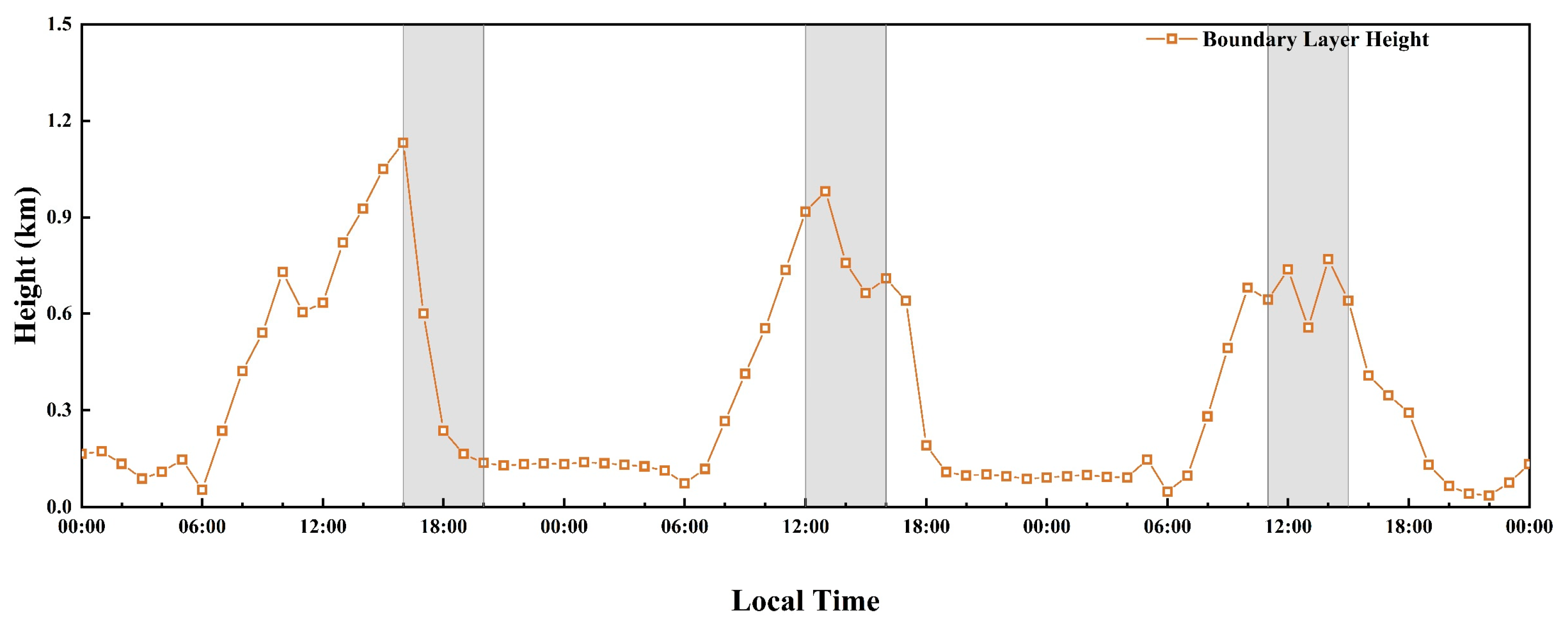

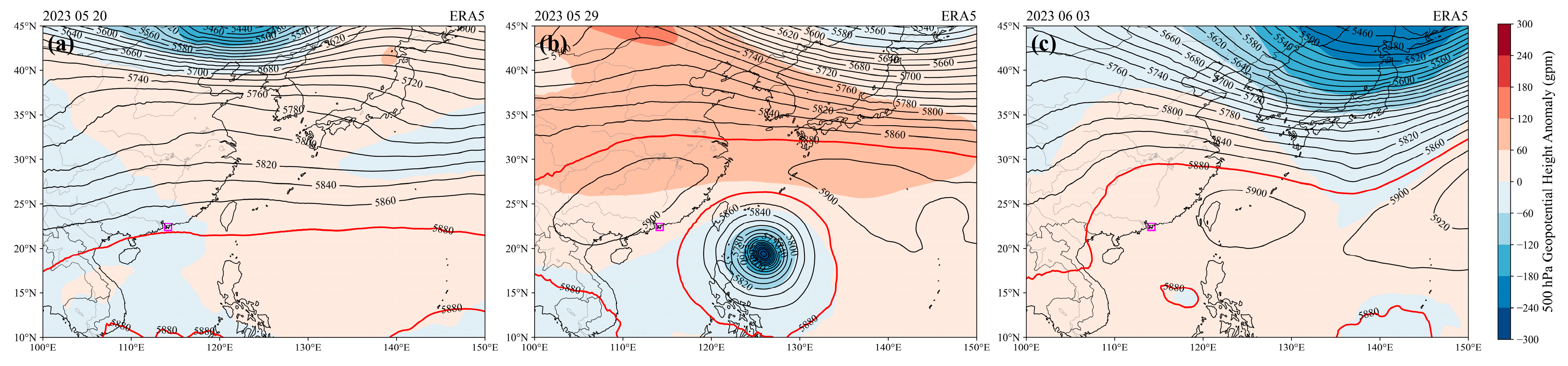

3.1. Background of the Ozone Pollution Episode

3.2. Overview of the Ozone Pollution Episode

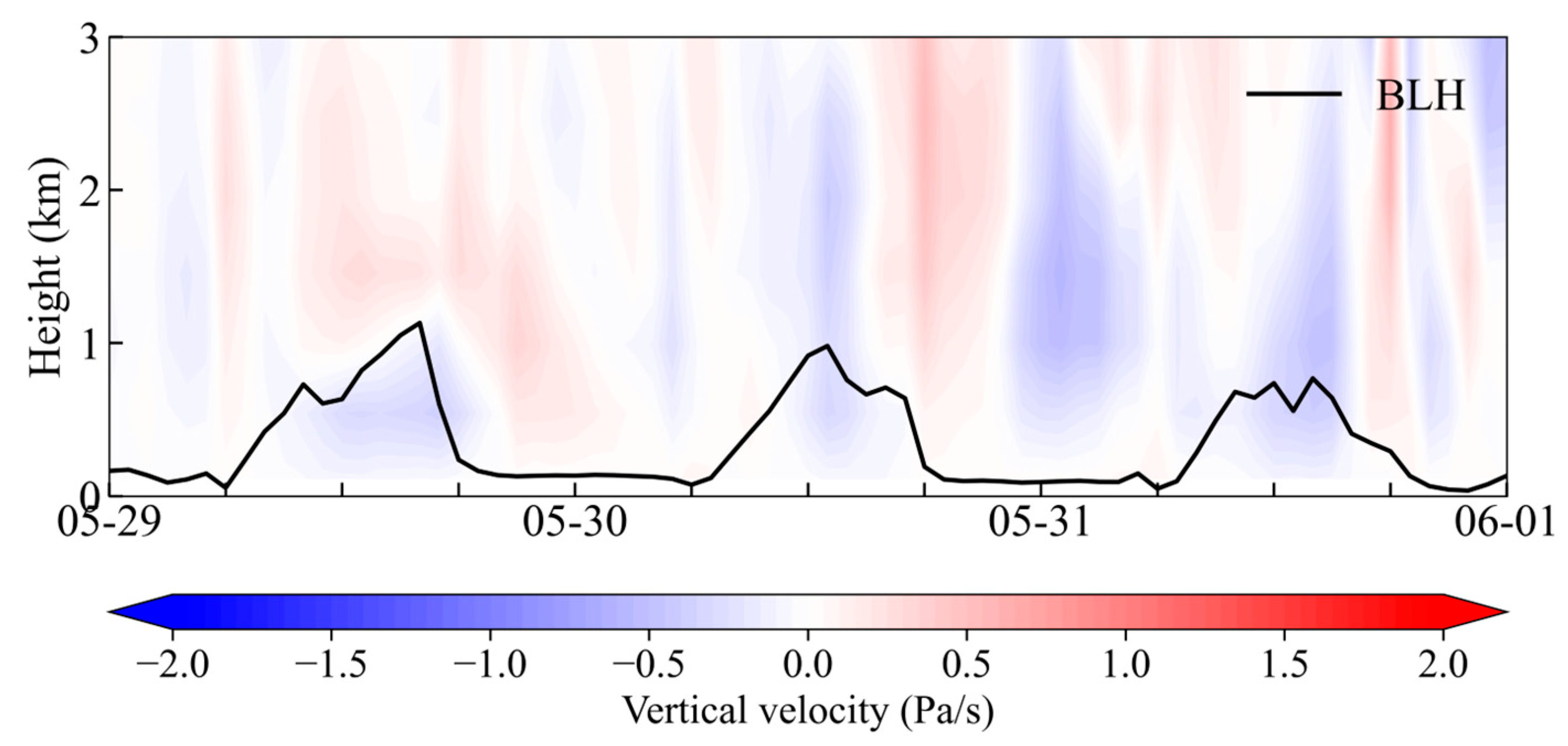

3.3. Lidar Observations of the Pollution Episode

3.3.1. Ozone Observation Results

3.3.2. Aerosol Observation Results

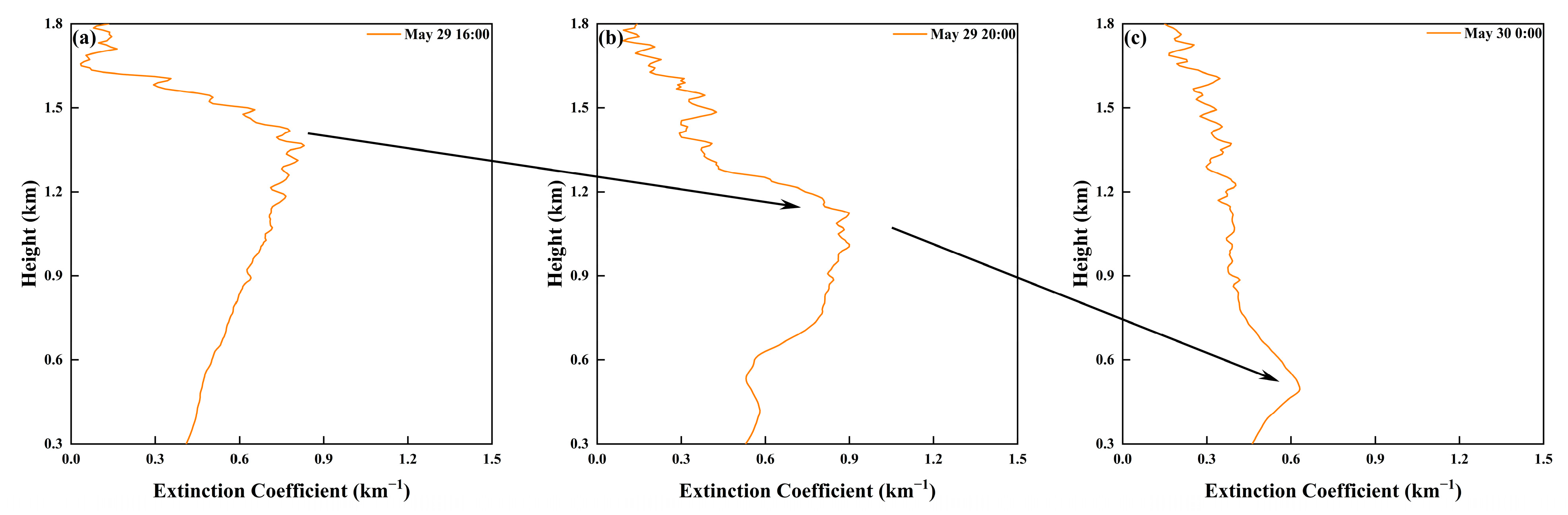

3.4. Vertical Profiles During the Key Periods

4. Discussion

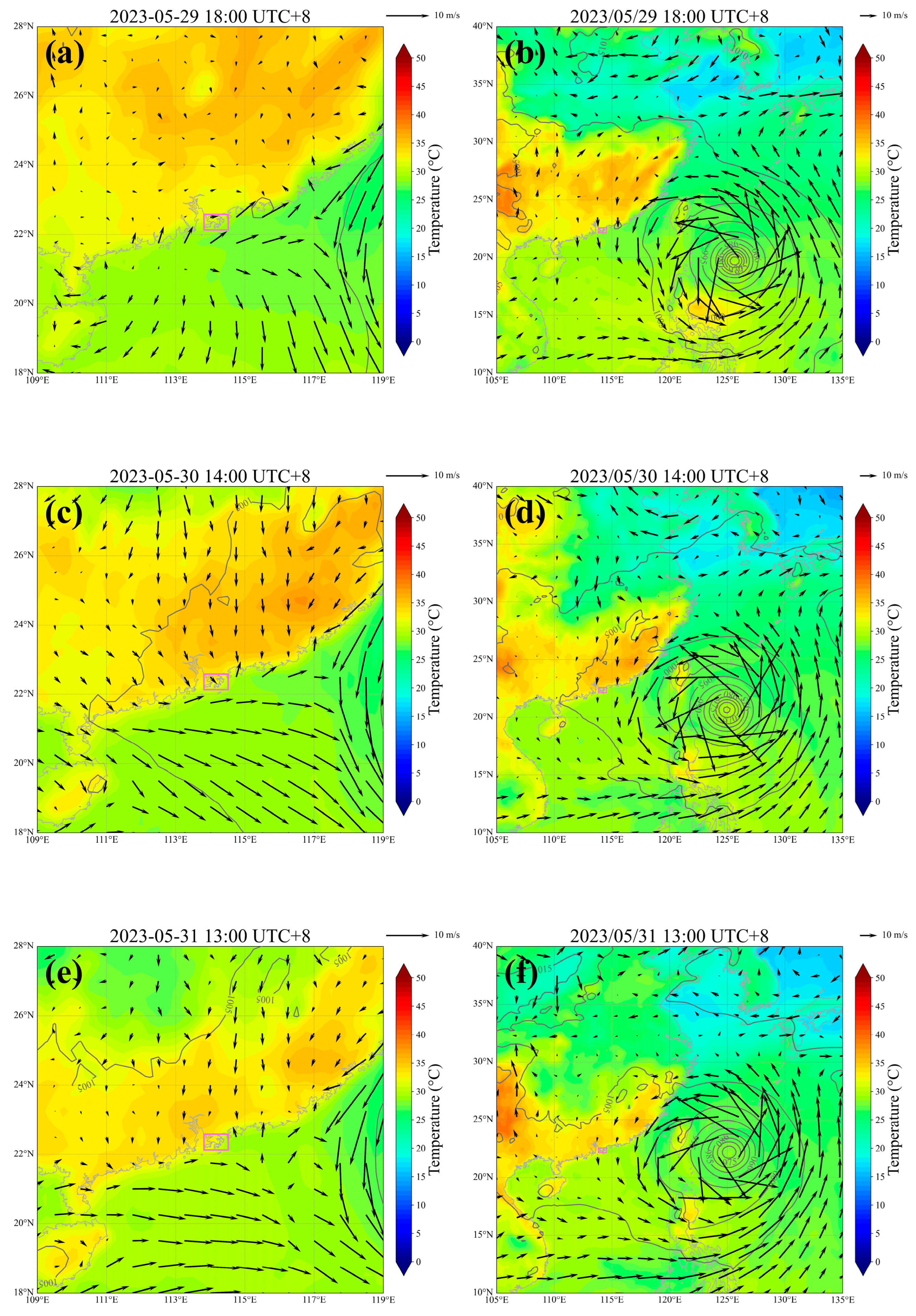

4.1. Synoptic Background Under the Influence of Typhoon Mawar

4.2. Transport Pathways During Key Periods

4.3. Transport Signatures from Lidar

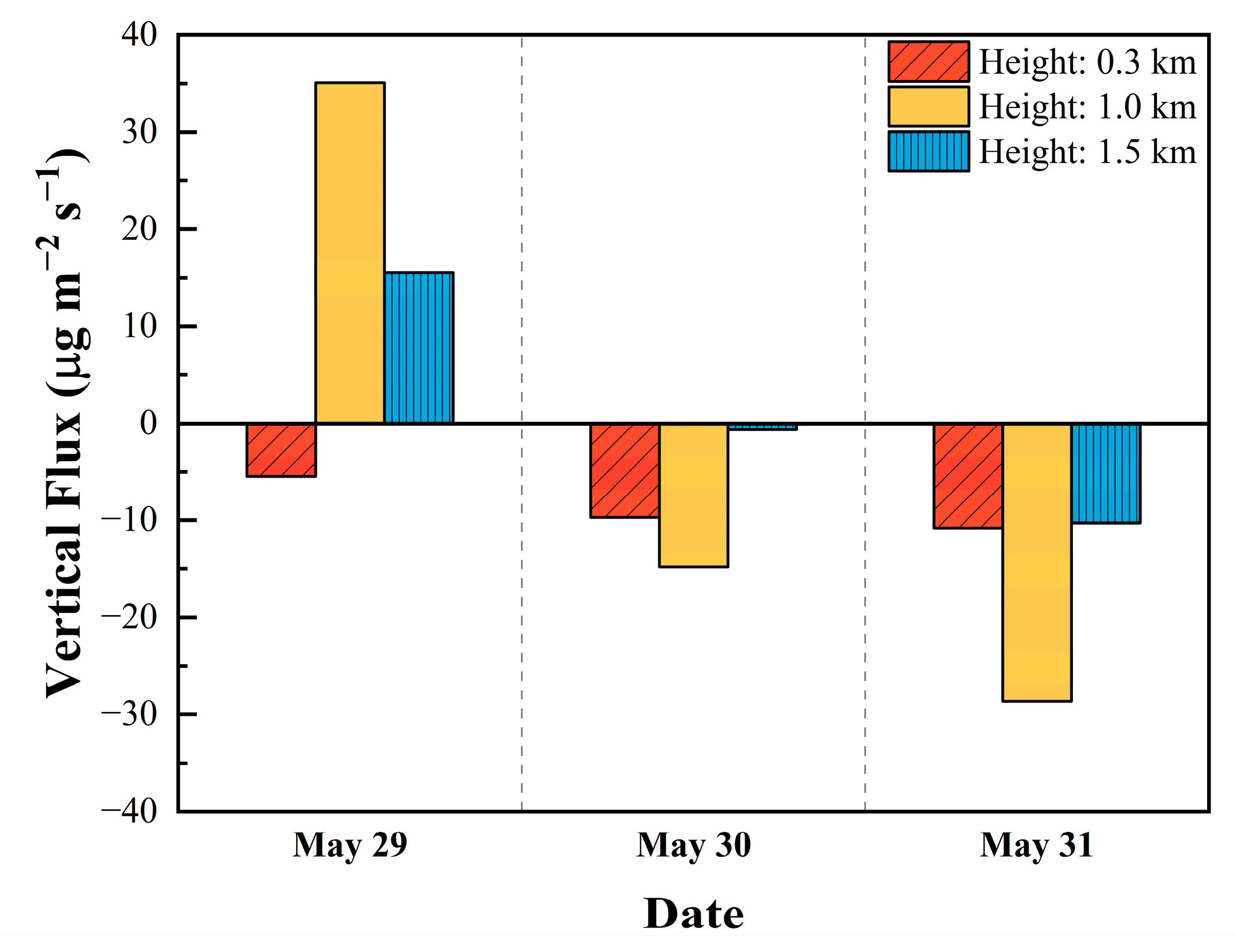

4.4. Vertical Transport Flux Analysis

4.5. Mechanism of This Episode

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VOCs | Volatile Organic Compounds |

| NOx | Nitrogen Oxides |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| MDA8 | Maximum Daily 8 h Average |

| OH | Hydroxyl Radical |

| HO2 | Hydroperoxyl Radical |

| STE | Stratosphere–Troposphere Exchange |

| SI | Stratospheric Intrusion |

| SITS | Stratospheric Intrusion to the Surface |

| PRD | Pearl River Delta |

| DIAL | Differential Absorption Lidar |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| AQMS | Air Quality Monitoring Station |

| HKEPD | Hong Kong Environmental Protection Department |

| ECMWF | European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts |

| CMA | China Meteorological Administration |

| NOAA | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

| HYSPLIT | Hybrid Single-Particle Lagrangian Integrated Trajectory |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WPSH | Western Pacific Subtropical High |

| BVOCs | Biogenic Volatile Organic Compounds |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Supplementary Information on Vertical Profile Analysis

References

- Vazquez Santiago, J.; Hata, H.; Martinez-Noriega, E.J.; Inoue, K. Ozone Trends and Their Sensitivity in Global Megacities under the Warming Climate. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, R. Atmospheric Chemistry of VOCs and NOx. Atmos. Environ. 2000, 34, 2063–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vongelis, P.; Koulouris, N.G.; Bakakos, P.; Rovina, N. Air Pollution and Effects of Tropospheric Ozone (O3) on Public Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donzelli, G.; Suarez-Varela, M.M. Tropospheric Ozone: A Critical Review of the Literature on Emissions, Exposure, and Health Effects. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achebak, H.; Garatachea, R.; Pay, M.T.; Jorba, O.; Guevara, M.; Pérez García-Pando, C.; Ballester, J. Geographic Sources of Ozone Air Pollution and Mortality Burden in Europe. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 1732–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Lu, X.; Jacob, D.J.; Cooper, O.R.; Chang, K.; Li, K.; Gao, M.; Liu, Y.; Sheng, B.; Wu, K.; et al. Global Tropospheric Ozone Trends, Attributions, and Radiative Impacts in 1995–2017: An Integrated Analysis Using Aircraft (IAGOS) Observations, Ozonesonde, and Multi-Decadal Chemical Model Simulations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2022, 22, 13753–13782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Liu, P.; Feng, Z.; Chang, M.; Wang, J.; Fang, H.; Wang, L.; Huang, B. Long-Term Trajectory of Ozone Impact on Maize and Soybean Yields in the United States: A 40-Year Spatial-Temporal Analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 344, 123407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarin, J.R.; Jägermeyr, J.; Ainsworth, E.A.; Oliveira, F.A.A.; Asseng, S.; Boote, K.; Elliott, J.; Emberson, L.; Foster, I.; Hoogenboom, G.; et al. Modeling the Effects of Tropospheric Ozone on the Growth and Yield of Global Staple Crops with DSSAT v4.8.0. Geosci. Model Dev. 2024, 17, 2547–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.H.; Gao, W.; Wang, S.; Song, T.; Gong, Z.; Ji, D.; Wang, L.; Liu, Z.; Tang, G.; Huo, Y.; et al. Contrasting Trends of PM2.5 and Surface-Ozone Concentrations in China from 2013 to 2017. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2020, 7, 1331–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Jacob, D.J.; Shen, L.; Lu, X.; De Smedt, I.; Liao, H. Increases in Surface Ozone Pollution in China from 2013 to 2019: Anthropogenic and Meteorological Influences. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2020, 20, 11423–11433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Wu, Q.; Li, B.; Liu, J.; Gong, X.; Zhang, L. Surface Ozone Pollution in China: Trends, Exposure Risks, and Drivers. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1131753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warneck, P. On the Role of OH and HO2 Radicals in the Troposphere. Tellus 1974, 26, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, H. Photochemistry of the Lower Troposphere. Planet. Space Sci. 1972, 20, 919–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archibald, A.T.; Neu, J.L.; Elshorbany, Y.F.; Cooper, O.R.; Young, P.J.; Akiyoshi, H.; Cox, R.A.; Coyle, M.; Derwent, R.G.; Deushi, M.; et al. Tropospheric Ozone Assessment Report: A Critical Review of Changes in the Tropospheric Ozone Burden and Budget from 1850 to 2100. Elem. Sci. Anthr. 2020, 8, 034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, H.; Lu, K.; Ma, X.; Tan, Z.; Long, B.; Chen, X.; Li, C.; Zhai, T.; Li, Y.; et al. Reactive Aldehyde Chemistry Explains the Missing Source of Hydroxyl Radicals. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, X.; Cheng, Y.; Parrish, D.D.; Ni, R.; Tan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Lu, S.; Wu, Y.; Chen, S.; et al. Ozone Pollution Mitigation Strategy Informed by Long-Term Trends of Atmospheric Oxidation Capacity. Nat. Geosci. 2024, 17, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, M.; Ren, X.; Wang, H.; Zeng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, X. Quantitative Relationships between the Production and Loss of OH and HO2 Radicals in Urban Atmosphere. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2004, 49, 1716–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shao, K.; Tang, X.; Li, J. The Study of Urban Photochemical Smog Pollution in China. Acta Sci. Nat. Univ. Pekin. 1998, 34, 392–400. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Lei, W.; Tie, X.; Hess, P. Industrial Emissions Cause Extreme Urban Ozone Diurnal Variability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 6346–6350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Song, X.; Zeng, S. Impact of the Urban Heat Island Effect on Ozone Pollution in Chengdu City, China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2023, 33, 1017–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Shi, H.; Song, X.; Jin, L. Impact of Urban Heat Island Effect on Ozone Pollution in Different Chinese Regions. Urban Clim. 2024, 56, 102037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Ge, M.; Xu, Y.; Du, L.; Zhuang, G.; Wang, D. Advances in Atmospheric Ozone Chemistry. Prog. Chem. 2006, 18, 1565–1574. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, C.; Niu, J.; Su, F.; Yao, D.; Xu, F.; Yan, J.; Shen, X.; Jin, T. Spatiotemporal Patterns and Regional Transport of Ground-Level Ozone in Major Urban Agglomerations in China. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Klein, P.; Xue, M.; Zhang, F.; Doughty, D.C.; Forkel, R.; Joseph, E.; Fuentes, J.D. Impact of the Vertical Mixing Induced by Low-Level Jets on Boundary Layer Ozone Concentration. Atmos. Environ. 2013, 70, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, W.; Du, H.; Tang, X.; Ye, Q.; Wang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Pan, X.; Zhu, L.; et al. Influences of Stratospheric Intrusions to High Summer Surface Ozone over a Heavily Industrialized Region in Northern China. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 094023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemball-Cook, S.; Parrish, D.; Ryerson, T.; Nopmongcol, U.; Johnson, J.; Tai, E.; Yarwood, G. Contributions of Regional Transport and Local Sources to Ozone Exceedances in Houston and Dallas: Comparison of Results from a Photochemical Grid Model to Aircraft and Surface Measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2009, 114, D00F02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Liu, J.; Zhao, T.; Xu, X.; Han, H.; Wang, H.; Shu, Z. Atmospheric Transport Drives Regional Interactions of Ozone Pollution in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 830, 154634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Lam, K.; Xie, M.; Wang, X.; Carmichael, G.; Li, Y.S. Integrated Studies of a Photochemical Smog Episode in Hong Kong and Regional Transport in the Pearl River Delta of China. Tellus B 2006, 58, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yuan, B.; Yang, S.; Peng, Y.; Chen, W.; Xie, Q.; Wu, Y.; Huang, Z.; Zheng, J.; Wang, X.; et al. Quantifying the Contributions of Meteorology, Emissions, and Transport to Ground-Level Ozone in the Pearl River Delta, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 932, 173011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, K.; Wang, X.; Cai, X.; Yan, Y.; Jin, X.; Vrekoussis, M.; Kanakidou, M.; Brasseur, G.P.; Shen, J.; Xiao, T.; et al. Rethinking the Role of Transport and Photochemistry in Regional Ozone Pollution: Insights from Ozone Concentration and Mass Budgets. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2023, 23, 7653–7671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Yan, F.; Xu, J.; Pan, L.; Yin, C.; Gao, W.; Liao, H. Observational Evidence of the Vertical Exchange of Ozone within the Urban Planetary Boundary Layer in Shanghai, China. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Han, X.; Tang, G.; Zhang, J.; Xia, X.; Zhang, M.; Meng, L. Model Analysis of Vertical Exchange of Boundary Layer Ozone and Its Impact on Surface Air Quality over the North China Plain. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 821, 153436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, J.; Qie, X.; Cheng, X.; Yang, M.; Shu, L.; Zang, Z. Stratospheric Influence on Surface Ozone Pollution in China. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.B.; Yuan, B.; Parrish, D.D.; Chen, D.; Song, Y.; Yang, S.; Liu, Z.; Shao, M. Long-Term Trend of Ozone in Southern China Reveals Future Mitigation Strategy for Air Pollution. Atmos. Environ. 2022, 269, 118869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.; Wang, H.; Chen, X.; Li, L.; Lu, X.; Lu, K.; Fan, S. Rapid Increase in Spring Ozone in the Pearl River Delta, China during 2013–2022. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2024, 7, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Guo, H.; Lyu, X.; Cheng, H.; Ling, Z.; Blake, D.R. Long-Term O3–Precursor Relationships in Hong Kong: Field Observation and Model Simulation. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017, 17, 10919–10935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Guo, J.; Wang, Z.; Gu, D.; Ho, K.F.; Chen, Y.; Liao, K.; Cheung, V.T.F.; Leung, K.K.M.; Yu, J.; et al. Investigation of the Multi-Year Trend of Surface Ozone and Ozone–Precursor Relationship in Hong Kong. Atmos. Environ. 2023, 315, 120139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, J.; Cheng, X.; Yang, M.; Wang, H. Positive and Negative Influences of Landfalling Typhoons on Tropospheric Ozone over Southern China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 2021, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browell, E.V.; Carter, A.F.; Shipley, S.T.; Allen, R.J.; Butler, C.F.; Mayo, M.N.; Siviter, J.H.; Hall, W.M. NASA Multipurpose Airborne DIAL System and Measurements of Ozone and Aerosol Profiles. Appl. Opt. 1983, 22, 522–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Liu, D.; Huang, Z.; Wang, B.; Bai, J.; Cheng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, P.; Yang, L.; Su, L. Polarization Properties of Receiving Telescopes in Atmospheric Remote Sensing Polarization Lidars. Appl. Opt. 2017, 56, 6837–6845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, T.; Pei, C.; Chen, D.; Lv, L.; Xiang, Y. Monitoring of Vertical Distribution of Ozone Using Differential Absorption Lidar in Guangzhou. Chin. J. Lasers 2019, 46, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, T.; Fu, Y.; Pei, C.; Lou, S.; Li, X.; Chen, Z.; Liu, W. Accuracy Evaluation of Differential Absorption Lidar for Ozone Detection and Intercomparisons with Other Instruments. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baylon, P.M.; Jaffe, D.A.; Pierce, R.B.; Gustin, M.S. Interannual Variability in Baseline Ozone and Its Relationship to Surface Ozone in the Western U.S. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 2994–3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Protection Department, The Government of the Hong Kong SAR. Homepage. Available online: https://www.epd.gov.hk/epd/english/top.html (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Environmental Protection Department, The Government of the Hong Kong SAR. Air Quality Monitoring Data Portal. Available online: https://cd.epic.epd.gov.hk/EPICDI/air/?lang=zh_cn (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Copernicus Climate Data Store (CDS). Available online: https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Biavati, G.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Rozum, I.; et al. ERA5 Hourly Data on Pressure Levels from 1940 to Present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS). 2023. Available online: https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-era5-pressure-levels?tab=overview (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Biavati, G.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Rozum, I.; et al. ERA5 Hourly Data on Single Levels from 1940 to Present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS). 2023. Available online: https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-era5-single-levels?tab=overview (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Hersbach, H.; Comyn-Platt, E.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Biavati, G.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; et al. ERA5 Post-Processed Daily Statistics on Pressure Levels from 1940 to Present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS). 2023. Available online: https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/derived-era5-pressure-levels-daily-statistics?tab=overview (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- China Meteorological Administration Shanghai Typhoon Institute. Tropical Cyclone Data Center. Available online: https://tcdata.typhoon.org.cn/en/index.html (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Stein, A.F.; Draxler, R.R.; Rolph, G.D.; Stunder, B.J.B.; Cohen, M.D.; Ngan, F. NOAA’s HYSPLIT Atmospheric Transport and Dispersion Modeling System. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2015, 96, 2059–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Li, J.; Lu, X.; Gong, C.; Zhang, L.; Liao, H. Impact of the Western Pacific Subtropical High on Ozone Pollution over Eastern China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21, 2601–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Wang, T.; Louie, P.K.K.; Luk, C.W.Y.; Blake, D.R.; Xu, Z. Increasing External Effects Negate Local Efforts to Control Ozone Air Pollution: A Case Study of Hong Kong and Implications for Other Chinese Cities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 10769–10775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong Kong Observatory. Monthly Weather Summary: May 2023. Available online: https://www.hko.gov.hk/en/wxinfo/pastwx/mws2023/mws202305.htm (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Hong Kong Observatory. Monthly Weather Summary: June 2023. Available online: https://www.hko.gov.hk/en/wxinfo/pastwx/mws2023/mws202306.htm (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Zheng, Y.; Jiang, F.; Feng, S.; Shen, Y.; Liu, H.; Guo, H.; Lyu, X.; Jia, M.; Lou, C. Large-Scale Land–Sea Interactions Extend Ozone Pollution Duration in Coastal Cities along Northern China. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 2024, 18, 100322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Chen, D.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Lang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, X. The Impacts of Ship Emissions on Ozone in Eastern China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 903, 166252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Jiang, F.; Feng, S.; Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Tian, X.; Ying, C.; Jia, M.; Shen, Y.; Lyu, X.; et al. Impact of Marine Shipping Emissions on Ozone Pollution during the Warm Seasons in China. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2024, 129, e2024JD040864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, A.; Fu, C.; Yang, X.; Sun, J.; Petaja, T.; Kerminen, V.M.; Wang, T.; Xie, Y.; Herrmann, E.; Zheng, L.; et al. Intense Atmospheric Pollution Modifies Weather: A Case of Mixed Biomass Burning with Fossil Fuel Combustion Pollution in Eastern China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013, 13, 10545–10554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, S.; Deng, T.; Liu, R.; Chen, J.; He, G.; Leung, J.C.H.; Wang, N.; Liu, S.C. Impact of a Subtropical High and a Typhoon on a Severe Ozone Pollution Episode in the Pearl River Delta, China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2022, 22, 10751–10767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Yang, Y.; O’Connor, E.J.; Lolli, S.; Haywood, J.; Osborne, M.; Cheng, J.C.H.; Guo, J.; Yim, S.H.L. Influence of a Weak Typhoon on the Vertical Distribution of Air Pollution in Hong Kong: A Perspective from a Doppler LiDAR Network. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 276, 116534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Station | Distance (km) 1 | O3 R Value 2 | PM2.5 R Value 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Southern (22.25°N, 114.16°E) | 22.58 | 0.82 | 0.75 |

| North (22.50°N, 114.13°E) | 4.32 | 0.94 | 0.85 |

| Tap Mun (22.47°N, 114.36°E) | 19.31 | 0.88 | 0.82 |

| Tung Chung (22.29°N, 113.94°E) | 27.18 | 0.81 | 0.74 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, L.; Wang, J.; Xu, Y.; Ma, N.; Song, X.; Qin, J.; Li, B.; Tsui, W.B.C.; Lv, L.; Zhang, T. Vertical Characteristics of an Ozone Pollution Episode in Hong Kong Under the Typhoon Mawar—A Case Study. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3904. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233904

Zhu L, Wang J, Xu Y, Ma N, Song X, Qin J, Li B, Tsui WBC, Lv L, Zhang T. Vertical Characteristics of an Ozone Pollution Episode in Hong Kong Under the Typhoon Mawar—A Case Study. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(23):3904. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233904

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Libin, Jie Wang, Yiwei Xu, Na Ma, Xiaoquan Song, Jie Qin, Beibei Li, Wilson B. C. Tsui, Lihui Lv, and Tianshu Zhang. 2025. "Vertical Characteristics of an Ozone Pollution Episode in Hong Kong Under the Typhoon Mawar—A Case Study" Remote Sensing 17, no. 23: 3904. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233904

APA StyleZhu, L., Wang, J., Xu, Y., Ma, N., Song, X., Qin, J., Li, B., Tsui, W. B. C., Lv, L., & Zhang, T. (2025). Vertical Characteristics of an Ozone Pollution Episode in Hong Kong Under the Typhoon Mawar—A Case Study. Remote Sensing, 17(23), 3904. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233904