Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Addresses key challenges in aerial perspective RGB-to-infrared translation (distribution inconsistency, small-target blurring, background interference) via a Brownian bridge diffusion-based framework.

- Innovates in three aspects: parabolic function-optimized diffusion coefficient/variance scheduling, Laplacian of Gaussian (LOG) loss (fusing high/medium/low-frequency features), and two core modules (MEM for spectral-modal fusion, IGM for wavelet-based guidance).

What are the implications of the main findings?

- Achieves state-of-the-art performance: PSNR 15.06, SSIM 49.47 (1.5%/1.2% higher than BBDM-VQ4), FID 36.83 (25.6% lower than BBDM-VQ4), LPIPS 2.0% lower than BBDM-VQ4.

- Provides high-fidelity infrared data support for aerial applications like nighttime reconnaissance and harsh-environment monitoring.

Abstract

Infrared images have garnered significant interest due to their superior performance, driving extensive research on visible-to-infrared image translation. However, existing cross-domain generation methods lack specialization for infrared image generation under aerial perspective, leading to distribution inconsistencies between synthetic and real infrared images and failing to mitigate challenges like small-target blurring and background interference under aerial views. To address these issues, we propose an RGB-to-infrared image generation method based on the Brownian bridge diffusion model for aerial perspective. Technically, we optimize the diffusion coefficient and variance scheduling of the Brownian bridge by introducing a parabolic function, design a Laplacian of Gaussian (LOG) loss that fuses high-, medium-, and low-frequency features, and construct two core modules: a modality enhancement module that integrates spectral involution and cross-modal fusion, and an information guidance module based on wavelet decomposition. Experimental results demonstrate state-of-the-art performance: the method achieves a PSNR of 15.06 and an SSIM of 49.47, which are 1.5% and 1.2% higher than the suboptimal baseline BBDM-VQ4, respectively; its FID is reduced to 36.83, representing a 25.6% decrease compared to BBDM-VQ4, and its LPIPS is 2.0% lower than that of BBDM-VQ4. This approach effectively eliminates distribution biases induced by small-target blurring and background interference under aerial perspective while ensuring the semantic consistency of generated infrared images.

1. Introduction

The integration of technological advancements and computer vision breakthroughs has significantly enhanced infrared-based target detection methodologies for aerial platforms [1,2,3], with current systems demonstrating operational maturity. Compared to visible-light detection approaches, infrared detection technologies exhibit distinct advantages in all-weather adaptability, maintaining functionality during nighttime operations and under low-visibility meteorological conditions such as fog, rainfall, and snowstorms. These systems also display robust environmental interference resistance by penetrating common atmospheric particulates like smoke and dust, while effectively distinguishing foreground targets from complex background information in challenging terrains [4]. Driven by iterative improvements in neural network architectures, infrared target detection has achieved critical advancements including reliable small-target identification in cluttered environments and efficient real-time processing on embedded hardware platforms. These innovations collectively address historical limitations in aerial infrared monitoring applications through enhanced scene adaptability and computational optimization.

However, the image acquisition technology of infrared targets under aerial perspective still has faced persistent technical constraints at present. The primary challenge stems from the specialized hardware requirements for infrared imaging, resulting in significantly limited dataset availability compared to mainstream RGB data repositories [5]. Furthermore, inherent limitations in infrared sensor technology—including thermal noise interference and detector sensitivity constraints—frequently produce images with suboptimal contrast ratios, reduced spatial resolution, and poorly defined object boundaries, ultimately degrading overall image fidelity [6]. These quality limitations substantially restrict practical applications in computer vision systems, particularly for complex scene interpretation tasks requiring high-precision inputs [7]. Compounding these issues is the scarcity of accurately annotated infrared datasets, which critically undermines model generalizability and robustness, thereby constraining downstream task performance across infrared-based machine learning frameworks [8].

The generation of infrared images through deep learning has become a crucial approach for enriching infrared image libraries. This methodology effectively utilizes two key data resources: abundant visible images containing extensive information, along with accurately captured paired infrared images, to achieve visible-to-infrared translation [9]. Before the emergence of deep learning techniques, conventional methods relying on physical modeling dominated infrared image generation [10,11,12]. These traditional approaches, initially developed in the early 2000s, were constrained by high computational complexity and limited capability in handling complex practical scenarios [5]. The field experienced transformative progress with advancements in deep learning. In 2016, Gatys et al. [13] introduced a novel training method using convolutional neural networks for image generation, establishing a foundational framework for infrared synthesis. The subsequent rise of Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN) in 2017 further accelerated developments. Isola et al. [14] developed the Pix2Pix framework, which employs adversarial training between generators and discriminators to produce high-quality target images, subsequently becoming widely adopted for visible-to-infrared conversion. During the same period, Zhu et al. [15] implemented CycleGAN with cyclic consistency loss to enable image generation using unpaired datasets. To enhance the generation level, researchers have explored the effective integration of multi-modal conditions into the network. Multimodal conditional guidance can be uniformly encoded as one-dimensional features, which can be cascaded with features in the network [16,17]. For visual guidance that is spatially aligned with the target image, the conditions can be directly encoded as 2D features, thereby providing accurate spatial guidance for generation or editing. To address the difficulty in training Gans, Huang et al. [18] proposed a well-performing regularized relativistic GAN loss. This method utilizes mathematical analysis to prove the guarantee of local convergence of the proposed model, effectively solving the problem of non-convergence that may occur during training. Based on the problems such as different category sets and asymmetric information representation in real-world scenarios, Wu et al. [19] proposed a novel model that uses steganography to suppress false features in generated images, which can enhance the semantic consistency of translated images without additional post-processing or supervision. Despite these improvements, challenges persist in current methodologies. Enhanced adversarial loss functions and structural optimizations, while improving transformation performance, remain susceptible to mode collapse during training processes [20,21,22]. Additionally, distributional discrepancies between generated and authentic infrared images persist despite advancements in visual quality [23,24]. Furthermore, the existing models have limited specialization in infrared images from an aerial perspective. Infrared images typically contain small targets, chaotic backgrounds, and complex environmental conditions.

Recent advancements have demonstrated that diffusion models exhibit competitive performance compared to GAN-based approaches in image generation tasks. The development of diffusion models has undergone rapid progress since their inception in 2015, when Bacciu et al. [25] first introduced diffusion probabilistic models (DPM). Subsequent research since 2021 has seen conditional diffusion methods [26,27,28,29] effectively applied to image-to-image translation. This approach conceptualizes image conversion as conditional generation, where target images emerge progressively through iterative diffusion processes. During the reverse diffusion phase, feature encodings from source images are integrated into the U-Net architecture to guide target synthesis. This methodology successfully addresses the persistent issue of GAN pattern collapse while simultaneously enhancing both detail preservation and distribution consistency in generated outputs. However, current conditional diffusion frameworks present two critical limitations: (1) Restricted generalization capabilities that confine applicability to scenarios requiring high input-output similarity, and (2) Performance instability in tasks demanding substantial variability, where cross-modal conditions necessitate intricate attention-based entanglement mechanisms. These constraints compromise model robustness and operational stability [30]. Li et al. [30] developed Brownian Bridge Diffusion Model (BBDM). This innovative framework establishes direct Brownian bridge mappings between input and output domains, enabling precise control over generation trajectories. Through this mechanism, BBDM achieves significant improvements in both detail quality and image consistency compared to conventional diffusion approaches. However, BBDM often fails to account for the unique characteristics of aerial perspective, resulting in distribution discrepancies between synthetic and real infrared images. Although DR-AVIT [31] has achieved good results for images based on the aerial perspective, its images are relatively clear and no unfavorable lighting conditions such as dark light and fog occur. Meanwhile, Ran et al. [32] adopted an adaptive diffusion model architecture and utilized multi-stage knowledge learning to achieve infrared transition from the full range to the target wavelength. However, due to the lack of detailed text data and segmentation mask maps in the dataset, the above-mentioned scheme idea cannot solve the existing problems.

To address the challenges posed by the characteristics of aerial perspective infrared imagery and existing distributional discrepancies, while enhancing both the detail quality and consistency of generated images, we propose the integration of Brownian bridge modeling into the visible-to-infrared image generation framework. The following methodological improvements have been implemented:

- Theoretical innovation: By optimizing the diffusion coefficient and variance process of the Brownian Bridge model, a new mathematical formula has been proposed, which can alleviate the distribution difference between the generated infrared images and the real images from the aerial perspective and enhance the model’s ability to rep-resent complex physical scenes.

- Algorithmic Innovation: A modality enhancement module combining spectral involution and cross-modal fusion is designed to reduce spectral discrepancies, while a joint optimization strategy integrating forward Gaussian loss and backward information guidance effectively suppresses background noise and improves target feature consistency.

- Practical Significance: Experimental results demonstrate that our method outperforms state-of-the-art approaches in infrared image generation, providing high-fidelity infrared data support for nighttime reconnaissance, harsh-environment monitoring, and other applications.

2. Related Work

2.1. Generative Modeling of Infrared Images

The synthesis of infrared imagery from visible light inputs constitutes a critical research direction in computer vision, enabling cross-modal perception across military reconnaissance, surveillance systems, and autonomous navigation. Initial methodologies in the early 2000s relied on physics-based approaches [33,34], where infrared generation was simulated through thermal radiation theory and optical transmission models. Jing et al. [35] advanced this paradigm in 2003 by developing a hybrid model combining geometric target representations with multispectral background textures, achieving predictable object synthesis. However, these physics-driven methods demanded precise parameter calibration and proved inadequate for complex scene modeling. Subsequent efforts in the 2010s attempted to enhance physical modeling through empirical infrared data integration [11]. Bae et al. [36] pioneered a wavelength-specific temperature estimation framework that combined background-target thermal profiles to synthesize multi-band radiation images. Despite these innovations, fundamental limitations persisted due to infrared data scarcity and insufficient physical priors for robust modeling. The deep learning revolution post-2015 transformed infrared synthesis methodologies. Gatys et al. [13] demonstrated neural style transfer’s potential for cross-spectral image generation, while Isola et al. [14] established the Pix2Pix framework as a GAN-based benchmark for paired visible-infrared translation. Concurrently, Zhu et al. [15] addressed unpaired data challenges through CycleGAN’s cyclic consistency constraints. Li et al.’s [37] D-LinkNet generator replacement in Pix2Pix, enhancing texture preservation through improved feature interdependency learning. State-of-the-art implementations like Lee et al.’s [6] edge-guided multidomain architecture achieved style-adaptive infrared generation with enhanced detail preservation through optimized style vector selection. To explore how to incorporate more visual information into the Tokenizer, Shi et al. [38] proposed a new framework called “Visual Gaussian Quantization” (VGQ), which significantly enhanced the structural modeling capability by integrating two-dimensional Gaussian functions into the traditional visual codebook quantization framework. A novel generative adversarial network based on cross-attention is proposed for the challenging task of generating character images. Tang et al. [39] proposed a novel generative adversarial network based on cross-attention for the task of generating character images to address the challenging task of generating character images. Nevertheless, Current methodologies exhibit inherent limitations in maintaining distributional consistency during image generation, while simultaneously demonstrating inadequate robustness against the characteristic challenges of aerial perspective infrared imagery, particularly small target dimensions, substantial background interference, and complex environmental conditions under aerial perspective.

2.2. Diffusion Model-Based Image Generation

Diffusion models draw inspiration from physical diffusion processes, progressively transforming data distributions into Gaussian noise through forward perturbation and subsequently reconstructing the original data via reverse denoising. This framework conceptually mirrors thermodynamic entropy transitions between ordered and disordered states.

The foundational work by Bacciu et al. [25] established DPM through dual Markov chain processes: forward noise addition and learned reverse generation. Subsequent developments by Ho et al. [40] in 2020 yielded denoising diffusion probabilistic models (DDPM), which optimized training through variational lower bounds and achieved unprecedented image quality by iteratively predicting and removing per-step noise. DDPM’s ability to preserve both fine details and global structures positioned diffusion models as viable alternatives to GANs.

Parallel advancements by Song et al. [41] introduced denoising diffusion implicit models (DDIM), which accelerated generation through non-Markovian sampling strategies. This innovation reduced required sampling steps from thousands to dozens while maintaining output fidelity. Further progress emerged with conditional diffusion models (CDM) by Batzolis et al. [26], enabling controlled image synthesis through conditional inputs. Rombach et al. [42] later enhanced computational efficiency through latent space operations in their latent diffusion models (LDM).

A critical advancement in diffusion model was achieved through Li et al.’s [30] BBDM, which enforces constrained trajectories between predefined source and target domains during generation. This framework uniquely maintains strict cross-modal alignment throughout the diffusion process, enhancing both microstructural fidelity and inter-domain mapping precision. By anchoring the diffusion pathway between fixed endpoints, BBDM effectively mitigates training instabilities caused by domain discrepancies while preventing mode collapse—a persistent limitation in GAN-based approaches. These capabilities enable robust generalization across diverse image translation scenarios, establishing BBDM as a versatile foundation for quality-driven synthesis tasks.

In 2024, Kim et al. [43] proposed the Unpaired Neural Schrodinger Bridge (UNSB), which enables the Schrodinger Bridge to convert between two arbitrary distributions. It can combine advanced discriminators and regularization to learn information between unpaired data. However, the above-mentioned model does not rely on paired data at all. In contrast, BBDM can ingeniously utilize the spatial alignment information in paired data through a bridging mechanism, thereby significantly outperforming UNSB, which is completely unpaired, in terms of generation quality and spatial consistency. In 2025, Ran et al. [32] introduced DiffV2IR to achieve semantic perception transformation. Through this novel image translation framework, unified visual language understanding was achieved, and the generation information of infrared images was enhanced by using the data of text language and binary mask maps. However, the existing datasets lack the above-mentioned data, and thus the above-mentioned methods cannot be used to enhance the corresponding aerial infrared image generation capability. Therefore, this paper ultimately adopts BBDM as our basic model.

2.3. Brown Bridge

The integration of Brownian bridge processes into diffusion models represents a significant advancement in generative modeling research. As a specialized stochastic process, the Brownian bridge formally characterizes random trajectories constrained between fixed initial and terminal states—a fundamental property that enables precise regulation of generation pathways. Incorporating this mechanism into diffusion frameworks enhances controllable synthesis, particularly for image-to-image translation tasks requiring strict cross-modal alignment.

This section systematically elaborates the theoretical foundations of Brownian bridge diffusion modeling, proceeding from its mathematical formulation to implementation architecture. By establishing these core principles, we lay the groundwork for subsequent technical discussions and empirical validations presented in later chapters.

2.3.1. Fundamental Concepts of Brownian Bridge

Brownian bridge is a conditional stochastic process with a fixed start and end point and intermediate paths obeying Brownian motion. Mathematically, Brownian bridge can be defined as:

is the standard Brownian motion and is the time endpoint. The Brownian bridge satisfies the following boundary conditions:

In the image generation task, the start and end points of the Brownian bridge can correspond to the input image and the target image, respectively, and the intermediate path describes the generation process from the input to the target.

2.3.2. Foundations of Diffusion Model

The forward diffusion process can be expressed as:

where is the noise image at step , is the noise variance, and represents the Gaussian distribution.

The backward diffusion process progressively denoises the noise distribution by learning it:

where and are the mean and variance of the neural network prediction.

2.3.3. Brownian Bridge-Based Diffusion Model

In BBDM, the forward diffusion process is modified:

where and are the mean and variance calculated from the properties of the Brownian bridge. Specifically:

Specifically in the actual diffusion process of the model, the intermediate process by can be expressed by the diffusion coefficient , and , that is, . Among them, can be arranged by time , and its formula is as follows:

where denotes the diffusion coefficient at time step , and are the minimum and maximum values of the diffusion coefficient, respectively, and is the total number of time steps.

The inverse generation process progressively denoises the noise distribution by learning it:

where and are the mean and variance of the neural network prediction.

The training objective of BBDM is to minimize the KL scatter between the inverse process and the true distribution:

By optimizing this objective, BBDM is able to learn the mapping relationship from the input image to the target image.

In the sampling process, BBDM starts from the noisy image and gradually denoises the target image. The specific steps are as follows

- Initialize to a noisy image.

- For , perform the following steps: Calculate the mean and variance

- Sampling from a Gaussian distribution : ∼

- Finalize the target image.

3. Methods

3.1. Basic Architecture

To address the challenges of small target dimensions, and environmental complexity in visible-to-infrared image translation under aerial perspective, we propose a refined Brownian bridge diffusion framework that systematically enhances generation quality and distributional fidelity.

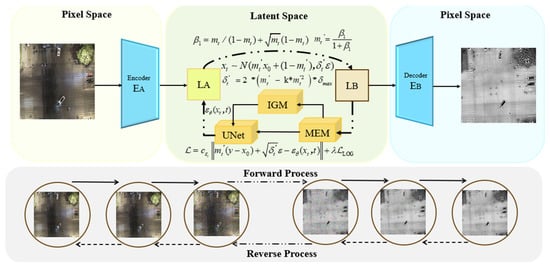

As shown in Figure 1, the DroneVehicle aerial photography paired dataset is first used as the input, which contains visible light (400–700 nm, texture information) and infrared (7.5–13.5 μm, thermal radiation information) images. First, conduct basic pretreatment: Normalize the pixel values to [0, 1] to eliminate luminance differences, unify the image size to adapt the model input, and then input the Latent Space through the Encoder in Figure 1. Compress the high-dimensional pixel data (256 × 256 × 3) into a low-dimensional latent vector (embedding dimension 3) through VQGAN encoding. The codebook 8192 not only reduces the computational complexity but also avoids the loss of details in traditional downsampling, providing efficient and complete basic features for subsequent feature extraction.

Figure 1.

Basic architecture of visible to infrared image generation based on Brownian diffusion bridge.

Secondly, during the forward diffusion process, noise is gradually injected into the image according to the designed Brownian bridge diffusion coefficient (parabolic function, divided into three stages: rapid increase → slow increase → linear convergence) and variance (k = 0.6, with the peak shifting to the right to expand the exploration space), simulating the feature evolution from visible light to infrared.

During the reverse process, features are input into the MEM to address the issues of small targets being submerged by the background and large spectral differences. Cross-modal correlation feature extraction is carried out, and the input latent features are processed in parallel along dual paths. The spectral matching path is used to unfold to retain 3 × 3 neighborhood information, and dynamic convolution is used to verify and enhance the edges of small targets to solve the edge blurring caused by background interference. The cross-modal fusion path introduces learnable infrared priors, and the gated generator screens positive correlation features to resolve the visible light-infrared spectral differences. It then undergoes element multiplication to precisely enhance the effective channels, residual connection, retain the background structure, can learn Alpha, adapt to uneven target distribution, three-level fusion, and output cross-modal aligned enhanced features.

The features output by MEM are subjected to learning frequency splitting by the wavelet decomposition module of IGM in Figure 1, and are adaptively split into high, medium and low frequency features to adapt to the dynamic frequency shift in aerial photography. The high-frequency edges of the target are respectively strengthened, the infrared mid-frequency thermal radiation is optimized, and the background low-frequency noise is suppressed. Through cross-frequency attention enhancement, frequency dependence is established to avoid frequency imbalance. Finally, dynamic fusion is achieved through the weight distribution network to adapt to the UNet input dimension.

Finally, in Figure 1, the LOG loss (fusing high, medium and low frequency Gaussian factors) optimizes the feature frequency alignment through gradient feedback, and is mapped back to the Pixel Space from the Latent Space by the Decoder to generate an infrared image.

The framework demonstrates superior performance in preserving structural details and thermal radiation accuracy under operational aerial perspective constraints, establishing a robust solution for cross-modal image translation under aerial perspective.

3.2. Diffusion Coefficient Equation Design

Due to the limitations of the linear scheduling of the original diffusion coefficient, it cannot meet the conversion of visible light to infrared images from the perspective of unmanned aerial vehicles. In order to enhance the intrinsic generative power of the Brownian bridge-based diffusion model, we modify the above linear diffusion process by, first, setting up:

Equation (11) defines the parameter , which serves as the quantitative indicator of the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in the original diffusion process. Specifically, is formulated as the ratio of to , where this ratio inherently encodes the dynamic balance between signal and noise intensities during the diffusion process. When approaches 0, tends to 0, indicating a dominant noise component in the system at the corresponding time step; conversely, as approaches 1, approaches infinity, reflecting a state where the signal overwhelms the noise. This mathematical formulation effectively quantifies the SNR variation over the diffusion timeline, as it directly mirrors the relative strength of the useful signal (related to the target image information) against the interfering noise (introduced during the forward diffusion perturbation). Such a definition of as the SNR lays the foundation for analyzing the noise-suppression and signal-preservation capabilities of the original diffusion model, and also provides a critical reference for our subsequent optimization of the SNR curve by introducing a parabolic function to better adapt to the visible-to-infrared image translation task.

In order to adapt to the task of generating visible to infrared images and improve the intrinsic generating ability of the network, this paper improves the signal-to-noise ratio by introducing a parabolic function after the signal-to-noise ratio. The function increases and then decreases in value with the increase of , making to :

When the design is completed, we apply the normalization principle to convert parameter into parameter . The specific equation is presented as follows:

At the end of the design, we use the normalization idea to reduce to , with the equation shown below:

At the same time, resetting = 0.999 ensures that the final stage of the diffusion process is close to 1. This allows the diffusion process to proceed sufficiently to avoid stopping prematurely.

Algorithm 1 shows the pseudo-code of the Optimized Diffusion Coefficient Scheduling method. It can be seen from the pseudo-code that this method dynamically manages the evolution of the signal-to-noise ratio through the parabolic function, enabling the diffusion process to generate infrared images Achieve a more refined balance between breaking the visible light domain features and establishing the infrared domain features.

| Algorithm 1. Optimized Diffusion Coefficient Scheduling Algorithm. |

|

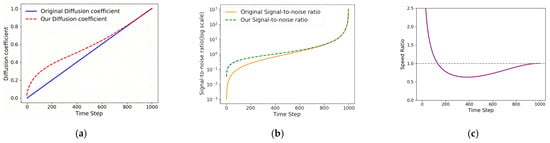

Figure 2 provides a visual comparative analysis of the baseline and proposed diffusion processes through three key aspects. As illustrated in Figure 2a, the comparative trajectories of diffusion coefficients between the baseline and our optimized parabolic formulation reveal three distinct operational phases. In the initial diffusion stage, the proposed coefficient demonstrates a steeper ascent curve, rapidly increasing to approximately 0.4. This accelerated progression enhances model convergence efficiency while strengthening the network’s capacity to prioritize global structural learning. During the intermediate phase, the coefficient growth rate moderates to align with baseline noise injection patterns, enabling gradual refinement of textural details without compromising local feature extraction. In the terminal phase, the coefficient progression converges linearly with the baseline scheme, effectively suppressing abrupt noise variations at later stages to mitigate high-frequency artifact overfitting. This triphasic modulation balances rapid structural learning, detail preservation, and stable convergence through parabolic trajectory optimization.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the visualization of the diffusion process with the original process after adding the parabolic function. (a) diffusion coefficients (b) signal-to-noise ratio (c) Speed Ratio.

Figure 2b illustrates the variation in signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) with time. It can be seen that SNR over time for the baseline diffusion process and the proposed diffusion process shows three characteristic stages. During the initial phase, the enhanced SNR under our formulation accelerates information propagation through intensified diffusion dynamics, enabling rapid global structural alignment between visible and infrared domains. This elevated SNR simultaneously suppresses early-stage noise interference, thereby improving initial image fidelity. In the intermediate phase, while maintaining SNR superiority over the baseline, the growth rate decelerates to facilitate progressive spectral adaptation. This moderated progression enables incremental refinement of domain-specific features while preserving critical thermal radiation patterns through sustained noise suppression. The terminal phase exhibits SNR trajectory convergence with the baseline due to parabolic modulation constraints, ensuring stable process termination without overfitting high-frequency artifacts. This phased SNR optimization achieves balanced performance across structural preservation, spectral adaptation, and distributional stability throughout the diffusion timeline.

As demonstrated in Figure 2c, the derivative comparison of diffusion coefficient progression between the baseline and proposed methods reveals a triphasic modulation mechanism, which is quantified by the Speed Ratio (the relative acceleration factor of the diffusion process). The baseline exhibits a constant derivative value, corresponding to a Speed Ratio of 1.0 throughout the diffusion timeline. In contrast, our optimized formulation achieves dynamic rate control, as reflected in the varying Speed Ratio.

During the initial phase (Time Step ~200), the derivative magnitude becomes multiple times higher than the baseline, with the Speed Ratio reaching up to 2.5. This accelerates noise injection to enhance generation robustness through rapid feature embedding. The intermediate phase (Time Step 200–800) shows moderated derivative values, maintaining a Speed Ratio consistently below 1 (around 0.5). This balances noise integration with information preservation for structural completeness. In the terminal phase (approaching Time Step 1000), the derivative progressively converges to baseline levels, as the Speed Ratio returns to approximately 1.0, ensuring consistent learning stability for dominant features across both methods.

This phased modulation strategy, guided by the precise tuning of the Speed Ratio, synergizes accelerated initialization, detail-aware refinement, and stable convergence. It effectively prevents overfitting on fine details while maintaining distributional coherence.

3.3. Diffusion Model Variance Design

The original equation for the variance process of the Brownian bridge-based diffusion model is shown below:

where is the variance at moment and is the maximum variance value.

We argue that the inherent cross-domain differences between visible and infrared image distributions require adaptive variance scheduling in a Brownian bridge-based diffusion model. Conventional fixed variance curves have proven to be insufficient to address the spectral differences arising from visible inputs under different scene characteristics and illumination conditions.

To address this limitation, we propose a conditional variance modulation mechanism in which the variance scheduling can be dynamically adapted to the characteristics of a particular input domain. According to our improved diffusion coefficient formula, front end of the variance function is redefined as a learnable variable, and the improved formula is as follows:

The quadratic coefficient k requires task-specific calibration as it governs the weighting of second-order terms in variance scheduling. Adjusting k dynamically alters the temporal evolution of variance during the diffusion process.

When k > 1, the variance peak shifts leftward along the diffusion timeline with reduced magnitude, over-constraining the model’s exploration capacity. This configuration induces infinite variance during the process, thereby destabilizing the optimization trajectory. Conversely, when k < 1, the variance peak shifts rightward with amplified magnitude, expanding the feasible solution space for cross-domain feature learning while maintaining stable optimization.

Table 1 presents the comparative performance indicators (PSNR, SSIM, LPIPS, FID) of different parameter configurations based on the BBDM-VQ4 model when k < 1. BBDM-VQ4 is an efficient cross-domain image transformation method that integrates the diffusion model and the improved vector quantization technology (VQ4). This method uses pre-trained VQGAN to convert pixel-level images into low-dimensional latent vectors. In the configuration, the embedding dimension is set to 3 and the codebook is 8192. By replacing the continuous latent vectors with discrete codebooks, parameter scale compression is achieved. The Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) and Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) quantify pixel-level and structural fidelity between generated and reference images, where higher values indicate greater similarity. The Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS) metric, derived from deep neural networks, evaluates perceptual similarity with lower values denoting closer perceptual alignment. The Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) measures the statistical distributional proximity between generated and real images, where reduced values reflect enhanced distributional realism.

Table 1.

Data comparison of PSNR, SSIM, LPIPS, and FID when k is less than 1.

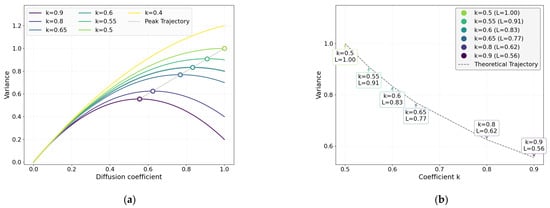

As depicted in Figure 3a, comparative variance curves under varying k values reveal systematic modulation effects. Progressive reduction in k from 1 induces quadratic term attenuation in the scheduling formula, resulting in amplified overall variance magnitude with delayed decay during terminal diffusion phases. This variance amplification manifests as a progressive rightward migration of the variance peak, intensifying noise injection dynamics to broaden the model’s exploration space for visible-to-infrared feature transformation.

Figure 3.

Comparison of variance processes of diffusion models. L represents the normalization coefficient of the variance peak (with the peak at k = 0.5 as the benchmark, L = 1.00); is the set maximum variance value, with a value of 1.0. (a) Comparison of full range variance curves. (b) Plot of peak position versus k.

Empirical observations from Algorithm 1 demonstrate non-monotonic performance trends: moderate k reduction (0.6 < k < 1) enhances distributional alignment with real infrared signatures (FID decline) by relaxing trajectory constraints, while excessive attenuation (k < 0.6) destabilizes optimization pathways, causing FID degradation due to suboptimal noise scheduling. Concurrently, delayed variance decay under low k values leads to incomplete denoising, progressively diminishing pixel-level fidelity (PSNR/SSIM reduction) and perceptual quality (LPIPS increase). The analysis suggests that variance scheduling plays a critical role in mediating the trade-off between distributional fidelity (FID) and perceptual generation quality (PSNR/SSIM/LPIPS). The adaptive quadratic term modulation appears to contribute to balancing exploration capacity and convergence precision through regulated noise injection dynamics during the diffusion process.

Experimental results indicate that the FID metric achieves optimal distribution alignment at k = 0.6, with sharp performance degradation observed when k deviates slightly to 0.55 or 0.65—a pronounced non-monotonic trend. While the variance curves in Figure 3a exhibit minimal visual divergence across k ∈ [0.5, 1], subtle parameter perturbations (±0.05 from k = 0.6) critically destabilize the model’s equilibrium during intermediate diffusion phases, significantly degrading infrared feature transformation capabilities despite negligible differences in curve morphology.

This sensitivity stems from the dual role of variance scheduling: constraining noise to facilitate distribution alignment (as seen at k = 0.6) versus enabling spectral adaptation. Deviations disrupt this delicate balance: lower k delays denoising, blurring thermal patterns, while higher k over-constrains feature exploration. Thus, precise calibration of the quadratic term is critical for harmonizing noise dynamics with cross-modal learning objectives in diffusion frameworks.

Figure 3b demonstrates peak position sensitivity to k-values: at k = 0.55, the peak reaches 0.91 (beyond operational limits), causing excessive mid-phase noise (flattened curve) that distorts infrared distributions. At k = 0.65, a reduced peak (0.77) with shallow slope inadequately suppresses visible-light features. The optimal k = 0.6 (peak = 0.83) achieves steep noise transitions, balancing local feature suppression and global distribution alignment for cross-modal translation. Algorithm 1 shows k = 0.9 marginally reduces reconstruction metrics (SSIM↓ 1.03%, PSNR↓ 0.09%, LPIPS↓ 0.59%) while moderately improving consistency (FID↑ 2.73%), suggesting controlled variance relaxation prioritizes domain alignment over pixel fidelity.

From the pseudo-code of variance scheduling optimization in Algorithm 2, it can be seen that the introduction of the adjustable parameter k enables the adaptive control of the aberration curve, allowing the model to flexibly adjust its “exploration ability” during the diffusion process according to the complexity of different scenarios, aiming to better capture the complex distribution relationship between visible light and infrared images.

| Algorithm 2. Adaptive Variance Scheduling Forward Diffusion Step. |

|

3.4. Laplace of Gaussian Loss

The Brownian bridge-based diffusion model integrates real noise from the forward process with the network’s predicted noise during the backward process to establish a quantitative comparison framework. This framework operates through two synergistic mechanisms. First, it dynamically evaluates the deviation between physical noise generation and learned noise prediction across diffusion stages. Second, the quantified deviation is directly formulated as a loss function, enabling gradient-based optimization of the noise-prediction network through backpropagation. By unifying process analysis and parameter updating within this architecture, the model achieves coordinated optimization of stochastic trajectory modeling. The expression is shown in Equation (16):

is a coefficient related to time , is a source domain image, is a target domain image, indicating the diffusion coefficient at time step , is the variance at moment , is Gaussian noise, and is the network prediction noise.

During practical training, we observe that background interference, environmental complexity, and small target dimensions under aerial perspective conditions impede the diffusion model’s capacity to extract effective contour, textural, and background distribution information from visible images. To address these limitations caused by background interference and small target dimensions, we propose integrating the Laplace of Gaussian Loss LOG into the loss formulation. It is worth noting that relying solely on the Brownian bridge-based diffusion loss which focuses on global noise deviation optimization can only maintain the overall distribution consistency of frequency features, but fails to accurately optimize local details of different frequency bands—for instance, it cannot effectively distinguish the high-frequency edges of small targets from high-frequency background noise, nor can it refine the medium-frequency thermal radiation details of targets. This is why the frequency feature dual-loss design is necessary: the dual loss diffusion loss + LOG loss not only constrains the global frequency distribution of generated infrared images through the diffusion loss to avoid large-scale deviations from real infrared characteristics, but also enables targeted optimization of high-, medium-, and low-frequency features via LOG loss, thereby precisely resolving the issues of frequency band confusion caused by background interference and frequency feature loss of small targets. This augmentation enhances the network’s capacity to prioritize the extraction of critical features and the synthesis of background thermal radiation distributions, object thermal boundaries, and infrared textural patterns through gradient backpropagation.

The total loss function after adding LOG is shown in Equation (17):

where is the diffusion coefficient at time step improved in this paper, is the variance at moment improved in this paper, is the hyperparameter, is the LOG, and the expression of is shown in Equation (18):

In the formula, , , are the weighting coefficients, , , are frequency features extracted by different Gaussian factors, which are used to distinguish the difference between the high, medium and low frequency features of the real infrared image and the generated infrared image. The high frequency, mid frequency and low frequency Gaussian factors are shown in Equations (19)–(21):

The -kernel employs a center-weighted (+4) and peripheral-suppressed (−1) configuration to enhance edge detection via local contrast amplification. It remains inactive in uniform regions. The -kernel combines a strong central weight (+5) with alternating neighborhood weights (+2/−1) to prioritize medium-frequency texture synthesis while suppressing high-frequency noise. The -kernel utilizes a symmetric 5 × 5 weighted averaging structure to achieve luminance-consistent smoothing, effectively attenuating high-frequency artifacts while preserving background structural integrity.

Extensive experiments were performed to determine the specific effects of hyperparametric and high-, mid-, and low-frequency features, and a comparison of the laboratory results is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of experimental indicators of different LOG factors.

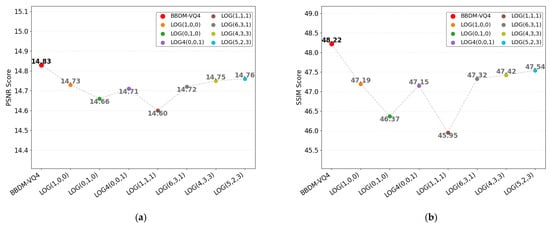

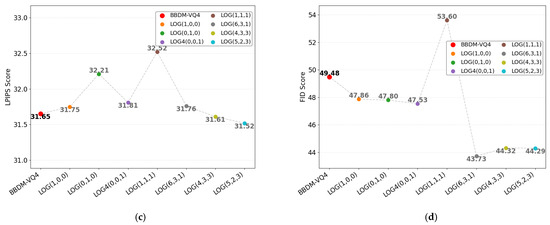

As can be seen from Table 2, LOG(1,0,0), LOG(0,1,0), and LOG(0,0,1) represent the results of training the model using high-frequency, mid-frequency, and low-frequency Gaussian factors as LOG, respectively. LOG(1,1,1) is the training result when the weights of the three factors are the same. LOG(6,3,1), LOG(4,3,3), and LOG(5,2,3) represent the training results when the weights of the hyperparameters are , , , respectively. Figure 4 shows the schematic diagram of the above results.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of LOG results. (a) PNSR (b) SSIM (c) LPIPS (d) FID.

As evidenced in Figure 4, the LOG(0,0,1) configuration achieves superior FID (47.86 vs. baseline 49.48) but exhibits degraded pixel-level metrics (PSNR 47.19, SSIM 31.75, LPIPS 47.86) compared to baseline values (PSNR 47.61, SSIM 32.20, LPIPS 44.97), attributable to its excessive edge enhancement amplifying high-frequency noise. The LOG(0,1,0) method demonstrates comprehensive metric degradation (FID 15.29, PSNR 46.85, SSIM 31.02, LPIPS 48.33) due to medium-frequency overfitting, while LOG(0,0,1)’s over-smoothing causes significant pixel-level metric degradation (PSNR 46.23, SSIM 30.15). The LOG(5,2,3) hybrid configuration optimally balances spectral priorities with high-frequency dominance (FID 14.76, LPIPS 44.29), marginally trading pixel-level metrics (PSNR 47.54, SSIM 31.52 vs. baseline 47.61FID/32.20) for enhanced distributional consistency. This empirically validates the efficacy of high-frequency emphasis with supplementary low-frequency constraints and minimal medium-frequency influence, despite inducing controlled metric-level trade-offs. Therefore, we use the LOG(5,2,3) method as a LOG.

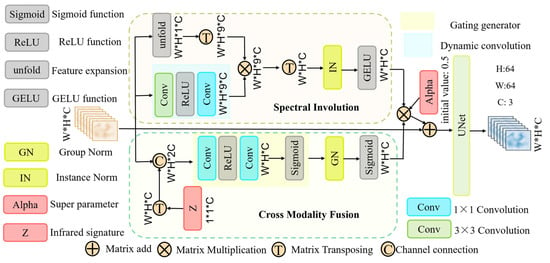

3.5. Modal Enhancement Module

In order to enhance the model’s ability to perceive between visible and infrared, reduce the spectral difference between the two, and achieve cross-modal feature alignment, as well as to strengthen the focus on the target under aerial perspective, this paper proposes the modal enhancement module.

As shown in Figure 5, the Modal Enhancement Module (MEM) adopts a dual-path architecture, focusing on local target enhancement and global modal alignment, respectively, to collaboratively solve the problems of small target blurring and cross-modal feature misalignment in aerial images. The spectral path utilizes dynamic convolution to retain neighborhood information and enhance the edge details of the target. Introduce learnable infrared priors through cross-modal paths to adaptively model the visible light-infrared mapping relationship from the data. The three-level adaptive fusion mechanism enhances the target details while maintaining the integrity of the background structure through feature map weighting and residual connection. The fusion weights are dynamically adjusted by learnable hyperparameters, ultimately achieving the unification of target enhancement, modal alignment, and feature robustness.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of the Modal Enhancement Module (MEM) structure: It demonstrates a dual-path and three-level adaptive fusion architecture including spectral pairing and cross-modal fusion, which is used to solve the problems of blurred features of small targets, visible light-infrared spectral differences, and cross-modal feature misalignment from the aerial perspective.

As shown in Figure 5, the visible image features processed by the VQGAN encoder are input into the spectral involution and cross-modal fusion in the modal enhancement module, respectively, and the spectral involution is targeted to strengthen the small target attention through a dynamically generated 3 × 3 convolution kernel to perform spatial adaptive feature enhancement in the local neighborhood. The expression is shown in Equation (22):

changes the input dimension W∗H∗C to W∗H∗1∗C by the unfold operation and converts the dimension to W∗H∗9∗C by the function, so that each position contains 3 × 3 neighborhood information. is the dynamic convolution kernel, which generates a spatially adaptive 3 × 3 dynamic convolution kernel using . The dynamic kernel generation is formulated as follows (Equation (23)):

is a nonlinear function. 3 × 3 depthwise convolution is applied to each channel independently to extract channel characteristic features, preserve spectral uniqueness, and avoid cross-channel interference. 1 × 1 convolution extends the number of channels up to a factor of 9 to generate the dynamic weights at each position to adapt to the geometric aberrations from an aviation perspective.

The in Equation (22) represents the expanded position dimension. multiplies the generated dynamic convolution kernel with the extended input features element by element to strengthen the edge response of the small target and enhance the structural continuity of the small target. The function is converted to W∗H∗C dimension to enhance the adaptability to multi-scale targets with multi-position weight fusion and realize spatial adaptive feature reorganization. Perform batch normalization with the function to suppress inter-instance differences, and make the model focus on the fine-grained representation of local features by the activation function.

Cross-modal fusion, on the other hand, explicitly establishes the basis of the thermal radiation distribution law by cross-modal interaction of the learnable infrared radiation prior with the visible features, the expression of which is shown in Equation (24):

is the learnable infrared modal a priori feature, which is upgraded to W∗H∗C dimension by function, spliced with the input features, and fed into the gating generator. After 1 × 1 convolution dimensionality reduction projection to the high-dimensional space, the nonlinear activation function filters out the negative interference, retains the cross-modal positive correlation features, captures the cross-modal interaction information, and generates the dynamic gating attention vector, which reduces the difference between the visible and infrared spectra. After that, the 1 × 1 convolution is used to recover the vector to W∗H∗C dimension, and the function performs singular value decomposition of the output vector to quantify the importance of the channels and realize the soft selection of feature channels. Finally, the function is used for normalization to provide stable distribution alignment, capture the correlation information between channels, and filter the low signal-to-noise ratio global features that may be introduced by the through the function, which lays the foundation for the subsequent modeling of the distribution law of thermal radiation.

Equation (25) is a two-path fusion expression for the cross-modal fusion part and the spectral involution part, which multiplies the outputs of the two paths of spectral details and cross-modal weights to realize feature cross-enhancement, and incorporates the original feature information with residual connections to avoid the disappearance of the gradient of the deep network. Meanwhile, the learnable hyperparameter Alpha is utilized to dynamically balance the original information with the new features to adapt to the challenges posed by complex scenes:

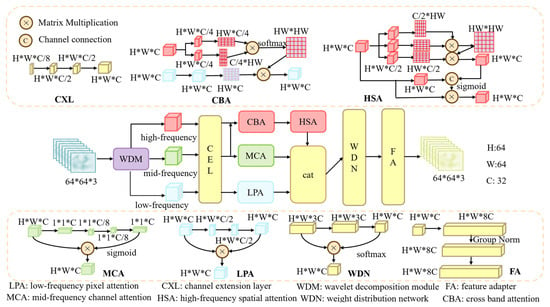

3.6. Information Guidance Module

In the task of converting aerial visible light-infrared images, feature extraction faces three major challenges: background interference causes the target features to be submerged; visible light and infrared images are, respectively, dominated by high-frequency textures and medium and low-frequency thermal radiation, and there exists cross-modal frequency heterogeneity. Existing methods such as wavelet decomposition rely on preset rules and are difficult to adapt to dynamic scenarios, while the attention mechanism lacks cross-frequency correlation modeling. The wavelet attention enhancement network proposed in 2025, which combines wavelet decomposition and attention weighting, is effective in single-modal tasks. However, it has limitations when applied to cross-modal transitions: time-frequency mixed features can disrupt the modal mapping relationship between visible light and infrared, and single-frequency attention is prone to causing high-frequency noise and low-frequency distortion. To this end, the IGM turns to frequency feature extraction, and through learnable frequency splitting, cross-frequency collaborative attention and loss closed-loop design, it specifically optimizes the cross-modal conversion task of aerial photography.

Figure 6 shows the schematic diagram of the information guidance module proposed in this paper. As shown in the figure, the IGM first peels off the high-, medium- and low-frequency components of the image through adaptive frequency decomposition and removes the time-domain information to retain the pure frequency features, thereby clarifying the cross-modal mapping from visible light high-frequency texture to infrared mid-frequency thermal radiation. The module dynamically adjusts the frequency division threshold through learnable convolution and activation layers to adapt to different scenarios. Subsequently, the high-frequency space, mid-frequency channel and low-frequency pixel attention are used in coordination to establish inter-frequency dependence and suppress background interference. Ultimately, this process forms a closed loop with LOG loss, jointly optimizing the modal consistency of frequency characteristics.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of the Information Guidance Module (IGM) structure: It shows the architecture including wavelet decomposition, cross-frequency domain attention enhancement and dynamic weight fusion, which is used to solve the problems of frequency feature imbalance, information loss caused by background interference and cross-modal frequency mapping misalignment in the visible light-infrared conversion of aerial photography.

C in the figure is the module setting channel with a value of 32. The input feature is processed by the wavelet decomposition module, and it is decomposed into three sub-band feature information of the high-frequency , medium-frequency , and low-frequency . As shown in Equation (26):

where and represent the front and back convolution weights, respectively, and the operation is the channel separation function. The wavelet decomposition module simulates multi-band decomposition using the front and back convolutions and the activation function. The first convolution extends the input channels to 24, while the second reduces them to 12 via grouped convolution. activation is applied to each convolution for nonlinearization. The wavelet decomposition module in this paper is learning in nature and can automatically learn the optimal decomposition for the task, and dynamically adjusts the band splitting by optimizing the parameters of the convolution kernel to retain the frequency components that are important for the task.

The decomposed high-frequency , mid-frequency , and low-frequency information is input into the channel expansion layer, which is expanded to 16 channels by the first convolutional layer to achieve nonlinearization through the activation function. And the number of channels is then further extended to 32 using convolution, which maps the frequency band features into a unified high-dimensional space and enhances the characterization capability. Therefore, the subsequent processing can make more effective use of information from different frequencies. The expression is shown in Equation (27):

After , , are extended to the high dimensional space, in order to establish the long range dependence of high frequency and low frequency features, enhance the inter-band synergy, and utilize the contextual information of low frequency to strengthen the generation of high frequency details to mitigate the adverse effects of the scene and enhance the generation consistency, we inputs , into the cross-frequency domain attention mechanism, with the expression as shown in Equation (28):

, , represent detail features of , context features of and global structure features of extracted by convolution, respectively, denotes the number of compressed channels, and is the activation function that performs the normalization operation.

In order to further strengthen the feature information of each frequency band and enhance the features of each frequency band, hybrid spatial attention, channel attention and pixel attention enhancement are performed based on , , , respectively. To address the difficulty in capturing complete object contours or fine textures, local branching is utilized to enhance edges and textures. Global branching is introduced to ensure semantic consistency and complete missing information. The expression is shown in Equation (29):

Among them, function and function are the local and global branching functions, respectively. The local branching captures the local details in pixel neighborhoods with convolutional operations to enhance high-frequency features. The global branch captures cross-region semantic associations by modeling long-range dependencies through the self-attention mechanism. The global features are summed with the local feature pixel values, and a spatial dynamic weight map is generated by the function, which balances the local details with the global structure, and finally the dynamic weight map is multiplied with the input to realize the hybrid attention of adaptive local-global feature co-enhancement.

To enhance structural information-sensitive channel of and suppress redundant or noisy channels, we use the channel attention mechanism to dynamically adjust the weights of different feature channels to enhance the channel responses that are crucial for structural modeling. The expression is shown in Equation (30):

is the average pooling layer, which provides channel-level statistical information through global average pooling so that the weight assignment focuses more on the overall structure rather than the local noise. and denote the descending and ascending convolution operations, respectively, which force the network to learn the nonlinear relationships among channels and filter the channels that are important to the IF structure through the descending (C → C/8) and ascending (C/8 → C) dimensions and the activation function . The result is the generation of channel weights that are multiplied by the output, and the result is generated through average pooling. Finally, is used to generate the channel weights, multiply with g, and output . Finally, the recalibration of the channel weights is realized, and the channels sensitive to structural information are adaptively enhanced to complete the nonlinear importance screening of the feature channels.

To enhance response to task-important pixels, reduce the weight of noise or irrelevant details, and reduce the possibility of over sharpening or distortion, pixel attention is utilized to enhance the global structural consistency through a three-step operation of local feature extraction → channel fusion → pixel-level weighting to strengthen the coherence of low-frequency information. The expression is shown in Equation (31):

and complete extraction of local neighborhood features to enhance local modeling of low-frequency information. restores the channel dimensions and fuses the cross-channel information to enhance the feature expression capability. Finally, function generates a pixel-level attention map, which adaptively adjusts the contribution of each pixel to the low-frequency features and multiplies it with to enhance the low-frequency features.

The weight generation module realizes adaptive feature fusion by dynamically learning the importance weights and residual connections of multi-band features after , and multi-band features are integrated into . The expression is shown in Equation (32). The expression is shown in Equation (32):

Among them, the weight generation module utilizes convolution and to capture the local spatial correlation, extracts cross-frequency band interaction features, enhances the context-awareness ability of weight learning, and reduces the dimensionality to 3 channels by . function generates dynamic weights according to each frequency information situation and multiplies them by to output . The output solves the cross-frequency band feature heterogeneity problem by the feature adapter, and realizes semantic alignment and dimensional adaptation with UNet by dynamically adjusting the feature representations.

4. Results

4.1. Experimental Settings

Models and hyperparameters: The proposed framework integrates a pre-trained VQGAN with a modified Brownian bridge diffusion model. During training, the Brownian bridge process is discretized into 1000 temporal steps, while inference employs 200 steps for computational efficiency. All comparative experiments adhere to standardized training protocols of 100 epochs, executed on identical hardware configurations utilizing vGPU-32GB acceleration and AMD EPYC 7T83 64-core processors to ensure experimental reproducibility.

Assessment: To assess the quality and distributional consistency of the generated infrared images, we use PSNR and SSIM to measure the pixel-level and structural similarity between the generated infrared images and the ground-truth infrared images in the test dataset. Higher values of these two metrics indicate better similarity between the generated infrared images and the corresponding real infrared images. The distance between the distribution of the generated image and the distribution of the real image is evaluated with FID, and lower values indicate better generation consistency.

Dataset and baseline: To demonstrate the ability to convert visible light images to infrared images from an aerial perspective, this paper uses the publicly available dataset DroneVehicle as the dataset for this paper. The infrared images in the DroneVehicle dataset [43] were collected from the FLIR Vue Pro R thermal imaging sensor carried by the DJI Mavic 2 Enterprise Advanced unmanned aerial vehicle. Its infrared band is 7.5–13.5 μm, which can reflect the thermal radiation characteristics of the object. It is suitable for all-weather monitoring tasks. The wavelength range of visible light (RGB) images is 400–700 nm, mainly capturing the reflection characteristics of objects to visible light. There are 17,990 pairs of paired images in the training set, 4498 pairs in the validation set, and 4498 pairs in the test set. The baseline methods include EGG-M [6], EGG-U [6], BBDM-VQ4 [30], BBDM-VQ8 [30], PIX2PIX [14], Cycle GAN [15], StegoGAN [19], DR-AVIT [31], UNSB [43].

4.2. Ablation Experiment

The experimental results in Table 3 demonstrate that phased integration of technical modules systematically addresses critical challenges in visible-to-infrared cross-modal generation. Initial optimization of the baseline model through diffusion coefficient reformulation enhanced generation capability, evidenced by PSNR and SSIM improvements of 0.23 and 0.86, respectively, alongside a 1.38 FID reduction. However, the marginal 0.02 LPIPS decrease revealed persistent limitations in semantic feature perception.

Table 3.

Comparison of ablation experiments.

Introducing the LOG induced a substantial 3.49 FID decline, validating high-frequency thermal radiation optimization, though this spectral prioritization caused minor SSIM and PSNR degradation (0.14 and 0.03 reductions), indicating inherent frequency-domain tradeoffs. Subsequent integration of the cross-modal feature alignment module further reduced FID by 1.66 while restoring SSIM and PSNR to 49.14 and 15.04, proving its compensatory effectiveness for low-frequency consistency. Nevertheless, the LPIPS increase to 32.62 highlighted persistent challenges in high-frequency detail stability.

Final incorporation of the information guidance module established bidirectional frequency-domain optimization: forward high-frequency constraints suppressed noise generation, while backward wavelet-based feature reconstruction enhanced spectral coherence. This synergistic mechanism yielded a dramatic 6.22 FID reduction, reversed LPIPS decline by 1.61, and elevated SSIM/PSNR to 49.47/15.06, achieving multidimensional alignment across structural, textural, and distributional dimensions. The progressive optimization trajectory substantiates that coordinated frequency constraints and modal complementarity effectively overcome aerial perspective generation bottlenecks under environmental complexity.

Table 4, which is constructed based on the integrated methodological innovations outlined in this table, differs fundamentally from Table 1. Table 1 only evaluates the performance of baseline BBDM and identifies k = 0.6 as its optimal variance coefficient. Table 4 focuses on verifying the tuning space and optimal value of variance coefficient k for the improved Brownian bridge diffusion framework. Its core goal is to find the k-value that maximizes the performance of the enhanced model and explore how different k-values can be tailored to diverse infrared image generation demands thus addressing the gap that Table 1 lacks parameter guidance for multiple scenarios.

Table 4.

Comparison of different k value indicators. The table shows the models with diffusion coefficient, LOG, MEM and IGM added in the ablation experiment.

From the experimental results in Table 4 the improved framework shows clear multi-dimensional optimal k-values. For the key distributional consistency metric FID the optimal value is at k = 0.7. This k-value is particularly suitable for scenarios prioritizing statistical alignment with real infrared images such as large-scale aerial surveillance tasks that require consistent thermal radiation distribution with real scenes. For pixel-level and structural fidelity metrics including PSNR and SSIM the optimal value shifts to k = 1. Here, the model achieves the highest PSNR and SSIM which is essential for scenarios emphasizing fine-grained reconstruction quality such as aerial infrared imaging of small targets like ground vehicles or architectural details where preserving texture clarity and structural integrity is critical. Even when k deviates slightly from these optimal points such as k = 0.9 or k = 0.8, the model maintains relatively stable performance. This further confirms that k can serve as a functional adjustment item for scenario customization. k values closer to 1 are ideal for low-noise aerial environments such as clear-sky daytime photography where pixel-level detail preservation is paramount. k values around 0.7 excel in complex environments such as hazy or cluttered backgrounds where distributional consistency prevents thermal pattern distortion.

Notably, compared with Table 1, the fluctuation magnitude of key metrics, especially FID and SSIM under varying k-values in Table 4, is significantly attenuated. This reflects two critical advancements of the improved framework. First it reduces dependence on manual k-tuning due to enhanced model robustness. Second it realizes partial internalization of variance regulation through the novel diffusion formulation. However, Table 4 further emphasizes that k remains a valuable tunable hyperparameter. Its ability to adapt to different generation priorities with k = 0.7 for distribution consistency and k = 1 for pixel fidelity fills the gap that Algorithm 1 only provides a one-size-fits-all evaluation of k where Table 1 identifies k = 0.6 as the sole optimal value for the baseline without considering multi-scenario needs.

In summary, the additional value of Table 4 lies in three key aspects that Table 1 does not address. First it identifies dual optimal k-values for the improved framework. k = 0.7 is optimal for FID and distributional consistency while k = 1 is optimal for PSNR SSIM and pixel fidelity. This ensures the model’s adaptability to multi-dimensional performance demands. Second it reveals the scenario-specific utility of different k-values providing clear parameter selection guidelines for real-world aerial infrared tasks. For example, k = 0.7 is suitable for large-scale surveillance and k = 1 is suitable for small-target detail reconstruction. Third it verifies that the improved framework not only enhances overall performance but also retains flexible parameter adjustability addressing the limitation of the baseline model from Table 1 which only has one optimal k and lacks adaptive potential for diverse scenarios.

4.3. Comparison Experiment

As evidenced in Table 5 benchmarking visible-to-infrared image translation methods, our proposed framework achieves state-of-the-art pixel-level reconstruction quality with PSNR (15.06 ± 0.12) and SSIM (49.47 ± 0.40). The notably small standard deviations (0.12 for PSNR and 0.40 for SSIM) indicate robust performance across repeated experiments, outperforming the suboptimal BBDM-VQ4 (14.83 ± 0.15 for PSNR, 48.22 ± 0.48 for SSIM) by 1.5% and 2.6%, respectively, validating the effectiveness of our target-aware optimization strategy for small objects and complex aerial perspective scenarios.

Table 5.

Compare the metrics of visible light and infrared image generation methods. Bold ones are the best, while red ones are suboptimal. The data are in the form of mean ± standard deviation from the results of the three experiments.

The method concurrently demonstrates superior semantic consistency, attaining an LPIPS score of 31.01 ± 0.85 (with a tightly controlled standard deviation reflecting stable perceptual similarity) and an FID of 36.83 ± 1.22. This FID is 25.6% lower than both BBDM-VQ4 (49.48 ± 1.65) and the aerial-specific baseline DR-AVIT (49.47 ± 1.55), and our method exhibits the smallest standard deviations across all four metrics among all compared models. This dual advancement achieved through joint optimization of thermal radiation accuracy and distribution alignment significantly mitigates perceptual artifacts and cross-modal distribution shifts, establishing new benchmarks for semantic-aware infrared image synthesis under environmental complexity, while the consistent low standard deviations underscore its reliability in real-world aerial applications.

Based on Table 6, our method shows significant improvements in PSNR (p = 0.042) and SSIM (p = 0.012) compared to the suboptimal baseline, indicating superior pixel-level reconstruction and structural similarity for small objects in aerial perspective scenarios. The extremely significant FID result (p = 6.54 × 10−5) confirms our method achieves far more consistent infrared distribution with real data, effectively reducing cross-modal shifts. These statistical findings collectively validate that our approach is effective in tackling background interference and target challenges under complex aerial perspective conditions.

Table 6.

The independent sample t-test of the method index results and suboptimal data in this paper.

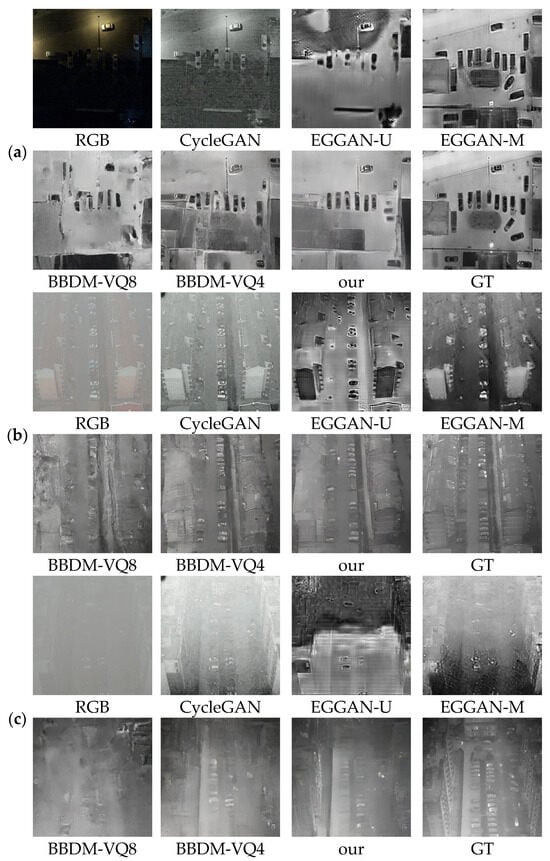

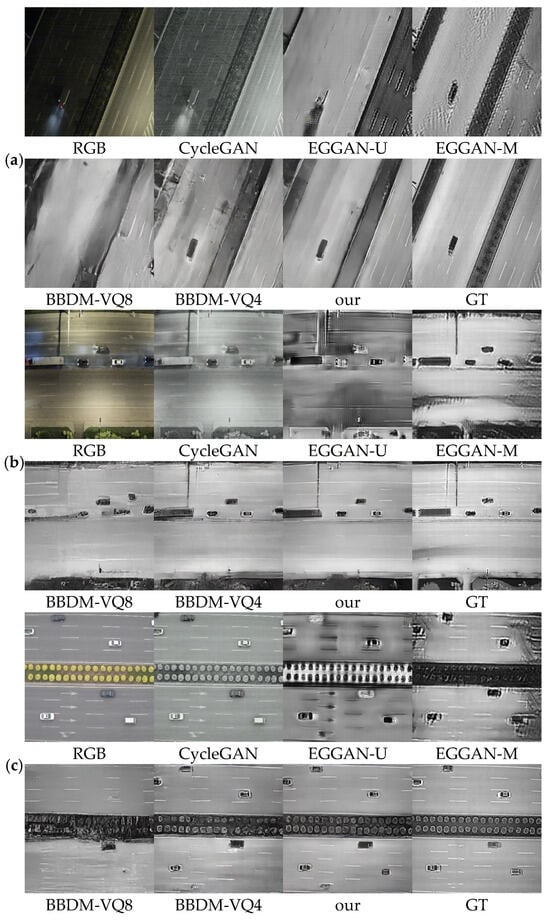

Figure 7 and Figure 8 demonstrate the method’s visual superiority across three illumination conditions (daylight, black light, luminosity) and three adverse scenarios (glimmering light, haze, dense fog). CycleGAN outputs exhibit RGB-like color fidelity but fail to capture thermal radiation characteristics, resulting in perceptually implausible infrared representations. While EGGAN-U and EGGAN-M preserve basic structural patterns, their generated images suffer from coarser object textures (vehicles, buildings) and chromatic distortions compared to ground-truth infrared data.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the visualization of the three bad scenario methods. (a) glimmering light. (b) haze. (c) thick fog.

Figure 8.

Comparison of visualization under three lighting conditions. (a) black light. (b) luminosity. (c) daylight.

Notably, EGGAN-M achieves enhanced structural alignment under glimmering light conditions through multi-domain transformation mechanisms, though at the expense of texture granularity and surface smoothness. Our method surpasses Comparison Algorithm in critical aspects: (1) finer edge preservation in vegetation and architectural details, (2) elimination of gradient discontinuities in terrain surfaces, and (3) thermal consistency matching authentic infrared signatures.

Among them, Figure 7 shows the difference in environmental interference intensity of gradient coverage from low light → haze → thick fog, and Figure 8 shows the difference in light intensity of gradient coverage from low light → normal light → daylight. The two work together to completely cover the data distribution differences in infrared images caused by changes in external conditions under the aerial perspective. This collaborative scenario design ensures that verification is not confined to a single data distribution. Instead, it directly demonstrates the model’s data balance through the stable consistency of the generated results with GT in various scenarios. That is, regardless of how the data distribution shifts due to the environment or lighting, the model can maintain a matching degree with the real infrared features, avoiding performance fluctuations due to data distribution bias.

Quantitative validation reveals our framework’s unique capability to maintain visual-intelligence alignment across all tested conditions, achieving the closest perceptual proximity to real infrared imagery in both normal and degraded environmental scenarios. This performance consistency stems from the joint optimization of spectral fidelity preservation and noise-resistant feature learning in our architectural design.

5. Discussion

Our results should be viewed against prior limitations: GAN-based methods (e.g., Pix2Pix) faced mode collapse, while diffusion models like BBDM-VQ4 struggled with aerial small-target blurring and background interference. Our 25.6% lower FID, plus improved PSNR/SSIM, confirms our innovations—parabolic diffusion coefficient, LOG loss, MEM/IGM—solve these gaps, matching our initial hypothesis. Practically, this work eases aerial infrared data scarcity, supporting UAV tasks like nighttime reconnaissance with high-fidelity synthetic data. Future research will extend the framework to extreme conditions (e.g., heavy smoke) and explore lightweight designs for on-UAV deployment.

6. Conclusions

This paper proposes a framework for generating RGB-to-infrared images from an aerial perspective based on the Brownian Bridge diffusion model, which specifically addresses the key challenges in aerial infrared image generation—such as poor cross-modal feature alignment, insufficient frequency domain optimization, and low consistency between generated images and real infrared data distributions. To tackle these issues, the framework optimizes the diffusion coefficient and variance scheduling strategy to enhance the stability of the generation process, designs a LOG loss function to mitigate modal discrepancy, and integrates a modal enhancement module and an information guidance module to realize precise cross-modal feature mapping and targeted frequency domain optimization. Experimental results validate the effectiveness of the proposed framework: across four key evaluation metrics (PSNR, SSIM, FID, and LPIPS), the method outperforms existing baseline models, with the FID score reduced by 25.6%—a significant improvement that demonstrates outstanding generation quality and strong distribution consistency between generated infrared images and real-world samples.

A core strength of this research lies in its targeted optimization for aerial scenarios: the integrated modules work synergistically to address scenario-specific pain points, and the modified diffusion mechanism balances generation fidelity and efficiency. However, limitations remain: the framework’s performance may degrade in extreme weather conditions (e.g., heavy fog, heavy rain) due to insufficient modeling of complex atmospheric interference, and the inference speed still has room for improvement when applied to real-time aviation tasks. Corresponding improvement options include introducing an atmospheric interference adaptive module to enhance robustness against harsh environments and optimizing the model’s network structure via lightweight design to accelerate inference.

Future research directions can be expanded in two aspects: first, extending the framework to multi-spectral infrared generation to meet more diverse aviation application demands; second, exploring the integration of self-supervised learning to reduce reliance on paired RGB-infrared training data. The research findings not only provide high-quality synthetic infrared data support for critical aviation applications such as night reconnaissance, harsh environment monitoring, and low-visibility navigation but also offer a new technical paradigm for cross-modal image generation in aerial scenarios. By bridging the data gap between RGB and infrared modalities in aviation, this work further promotes the practical application of computer vision technology in aerospace security and environmental monitoring, bearing significant theoretical reference value and practical guiding significance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.W. and W.C.; methodology, X.W. and J.F.; software, Y.D.; validation, Y.D., X.D. and Z.Y.; formal analysis, S.L.; investigation, S.L.; resources, Y.D.; data curation, Z.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, X.W.; writing—review and editing, W.C. and H.J.; visualization, W.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ren, X.; Sun, M.; Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Zhou, H.; Ren, X. An improved mask-RCNN algorithm for UAV TIR video stream target detection. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 106, 102660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Wang, Q.; Luo, Y.; Hou, Y.; Cao, J.; Zheng, W. YOLO-TSL: A lightweight target detection algorithm for UAV infrared images based on Triplet attention and Slim-neck. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2024, 141, 105487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Liu, T.; Cheng, J.H.; Cheng, B.; Cai, Y. AIMED-Net: An enhancing infrared small target detection net in UAVs with multi-Layer feature enhancement for edge computing. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Ren, H.; Ye, X.; Zhu, J.; Zeng, H.; Nan, Y.; Sun, M.; Ren, X.; Huo, H. Object detection from UAV thermal infrared images and videos using YOLO models. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 112, 102912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, A.; Sharma, M.; Mukherjee, P.; Singhal, A.; Lall, B. A comprehensive survey on synthetic infrared image synthesis. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2025, 147, 105745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.G.; Jeon, M.H.; Cho, Y.; Kim, A. Edge-guided multi-domain rgb-to-tir image translation for training vision tasks with challenging labels. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), London, UK, 29 May–32 June 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 8291–8298. [Google Scholar]