Highlights

What are the main findings?

- A novel multi-technique data fusion methodology (UAV-LiDAR, TLS, MMS, and Spherical Photogrammetry) was developed and validated, enabling the complete 3D documentation of geologically complex scenes with high occlusion levels, such as narrow gorges and vertical walls.

- A high-resolution 3D model and point cloud (1–10 cm average density) were success- fully generated for the Caminito del Rey (Málaga, Spain), covering the entire study area (over 20 billion points) and overcoming significant GNSS coverage limitations and operational risk.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- The proposed methodology establishes a robust and efficient geomatic workflow for detailed risk mapping in inaccessible and dangerous environments, enabling the creation of centimeter-precision digital assets for critical infrastructure management.

- The high-precision 3D model and other geomatic products (orthophotos and DTMs) provide the essential geometric foundation for implementing more reliable 3D rockfall simulations and conducting effective rockfall susceptibility and risk analysis, which is crucial for public and infrastructure safety.

Abstract

The use of digital photogrammetry and laser data acquisition systems, along with the ability to mount these sensors on unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), has revolutionized rockfall assessment. While these techniques have facilitated numerous studies across diverse scenarios, complex environments like narrow gorges necessitate the integration of various geomatic techniques to achieve complete and accurate spatial products. To address the critical gap in the literature regarding standardized multi-sensor integration in narrow gorges, this study presents a novel methodology for the cohesive integration of data from these techniques, leveraging their respective strengths to generate reliable products for rockfalls risk assessment. To validate the methodology, we applied this approach to a challenging rockfall susceptibility study at the Caminito del Rey in Málaga, Spain. The site presented significant complexities, including vertical walls hundreds of meters high with abundant overhangs, and canyons as narrow as 10 m, severely limiting single-technique approaches. The successful integration of these diverse datasets yielded a comprehensive, very high-resolution point cloud (1–10 cm density), among other products, covering the entire study area, making it ideal for detailed rockfall assessment and simulation. The approach has demonstrated that data fusion from multiple techniques supposes an advantage because one supports the other both in data coverage and in processing. Although processing the extensive acquired information presented a significant challenge, a successful balance between data volume and processing capacity was achieved, ensuring the outputs met the specific requirements for these studies.

1. Introduction

Mass movements are geological processes defined as the downslope movement of rock, debris, or soil under the direct influence of gravity, and are a major geohazard worldwide [1]. Rockfalls are a common type of landslide in mountainous areas worldwide [1]. They are considered among the most dangerous phenomena due to their speed, size, and the distances they can travel, directly affecting populations and infrastructure. Rockfalls can involve single or multiple blocks, from small volumes to hundreds of cubic meters. Their main triggers include earthquakes, freeze–thaw cycles, temperature changes, intense or prolonged rainfall, and root penetration. Human causes involve undermining of rock slopes, mining activities, leaking pipelines, ineffective drainage, and vibrations caused by blasting or traffic [2]. Evidence of previous rockfalls often serves as a good indicator of their presence in an area [2].

The availability of high-precision and high-spatial-resolution terrain models has transformed how we study rockfalls. These models not only allow us to identify areas most susceptible to this type of landslide but also facilitate multitemporal studies by comparing point clouds, digital terrain models (DTMs), and 3D models. For these comparisons, various distance metrics are employed, such as the difference between DTMs (DEM of Difference—DoD), the cloud-to-cloud distance (C2C), the cloud-to-cloud distance considering the surface normal (Multiscale Model to Model Cloud Comparison—M3C2), and the cloud-to-mesh or cloud-to-model distance (C2M) [3]. These products are also crucial for rockfall simulations using 2D, 2.5D, and 3D models [4].

In recent years, the development and application of various geomatic techniques have been instrumental in the efficient production of these models. These include Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) technologies, both airborne (Airborne Laser Scanning—ALS) and terrestrial (Terrestrial Laser Scanning—TLS), and photogrammetry, encompassing traditional aerial photogrammetry based on stereoscopic pairs and near-object photogrammetry (better known as Close Range Photogrammetry—CRP). These techniques can be applied individually or in combination, leveraging their respective benefits to improve data capture and processing efficiency, ensuring that their fusion enhances the quality of the resulting products.

The implementation of multiple techniques and multitemporal studies necessitates a common coordinate reference framework, typically based on a global reference system. In this regard, the widespread use of Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) instrumentation and improvements in satellite positioning networks, with real-time differential corrections (Real Time Kinematic—RTK), have enabled centimeter-level accuracy in absolute positioning. Furthermore, in photogrammetry, the advancement of computer vision algorithms like Structure from Motion (SFM) and Multi-View Stereo (MVS), integrated into various software applications (e.g., Agisoft Metashape), has democratized these techniques [5], making them accessible even to non-professional users. More recently, mobile mapping systems (MMS) [6] based on Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM)—including Visual-SLAM and LiDAR-SLAM—are enhancing data capture efficiency by achieving complete object coverage in real time and minimizing subsequent recording tasks. While they may not yet match the precision of techniques like TLS or traditional photogrammetry, their evolution is continuous. For highly complex areas, new sensors like 360-degrees cameras are also being incorporated to further optimize capture efficiency and processing [7], employing spherical photogrammetry (SP) [8] based on fisheye images or spherical images [7]. The development of methodologies for seamlessly integrating and fusing data from multi-sensor and multi-platform systems, such as the combination of aerial and terrestrial data, has become a central research topic in recent years [9,10]. This fusion is essential not only to enhance the geometric completeness of the final product but also to improve accuracy through complementary measurements. However, achieving a truly cohesive and standardized data fusion workflow, especially in environments with extreme geometric complexity and signal constraints, remains a significant challenge, which this study aims to address.

Within the context of rockfall studies, several existing works stand out for their use of one or more geomatic techniques. Initial studies primarily relied on TLS [11,12,13,14,15,16]. Notably, Lato et al. [17] used a vehicle-mounted mobile LiDAR device to reduce data capture time. For airborne LiDAR (ALS), works such as Lan et al. [18] are significant. Recent years have seen a surge in photogrammetry-based studies, often employing cameras mounted on UAVs [19,20,21,22,23]. Finally, it is worth highlighting works that combine data from different techniques, such as TLS and ALS [24], TLS, ALS, and mobile LiDAR [25], TLS and helicopter aerial photogrammetry [26], ALS and UAV photogrammetry [27], TLS and UAV photogrammetry [28], and the combination of UAV LiDAR and UAV photogrammetry [29]. Recent studies have intensified efforts to create standardized fusion pipelines for complex terrain [30,31] or focus on the integration of mobile and static terrestrial methods for infrastructure inspection [32]. However, most of these studies primarily compare data obtained with different techniques or propose their independent application at different times, thus not achieving a true, cohesive multi-technique data fusion, particularly one that rigorously integrates and standardizes the processing across all types (aerial and terrestrial, static and mobile, conventional and spherical photogrammetry) simultaneously. This limitation hinders a comprehensive understanding of rockfall phenomena and the optimization of geomatic workflows.

When selecting an appropriate technique, certain aspects related to the study area and equipment availability must be considered. These aspects impact all project phases, from data capture to product acquisition and comparison. For data capture, the complexity of the study area is crucial. Ground-based techniques like terrestrial photogrammetry and TLS systems may face limitations in accessing certain areas (due to accessibility or equipment safety) and in achieving complete object coverage, often showing gaps due to occlusions. Consequently, techniques employing aerial platforms for data capture have become widely used, largely thanks to the development and widespread adoption of UAVs [33]. UAVs allow data capture from elevated viewpoints, facilitating access to complex and unsafe areas, minimizing occlusions, and enabling the production of high-resolution models. These devices can be equipped with GNSS-RTK positioning systems for preliminary georeferencing, which can then be refined with ground control points (GCPs).

The limitations observed in the literature are particularly pronounced in complex environments like narrow gorges and deep canyons, where the use of a single geomatic technique is often not viable. Multiple factors support this assertion: the presence of rockwall occlusions and overhangs that block line-of-sight for static sensors (TLS), dense vegetation that impedes ground capture, limited spatial volume affecting UAV maneuverability and safety, and severe signal degradation that weakens GNSS observations and differential corrections. All these factors—including the extreme topography, safety restrictions, airspace limitations, and severe GNSS signal degradation—collectively rendered any geomatics project based on a single technique unfeasible for achieving the required centimetric resolution and complete coverage. This set of limitations conclusively demonstrated the necessity of developing and applying a robust multi-technique approach based on the cohesive fusion of complementary datasets to overcome the limitations of each individual sensor.

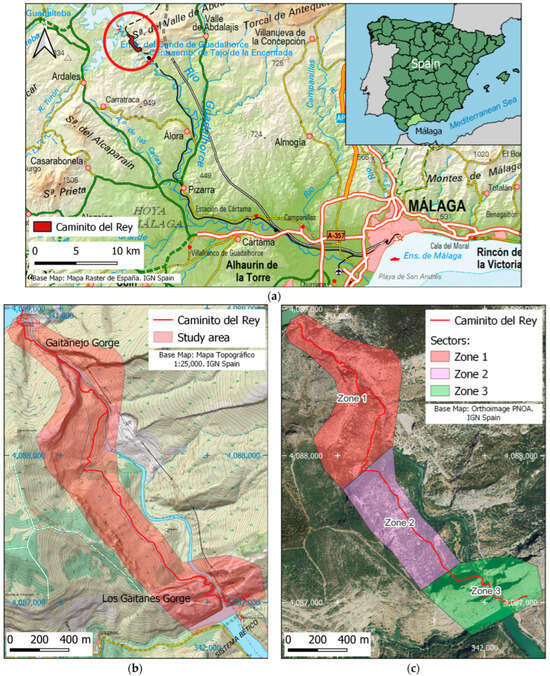

1.1. Case Study

The Caminito del Rey is a hiking trail embedded in the Gaitanes Gorge (Málaga, Spain) (Figure 1a), a rocky canyon featuring a series of footbridges at varying heights (up to 100 m) over the Guadalhorce River. It is located between the Malaga municipalities of Ardales, Antequera, and Álora (Figure 1a) within the Los Gaitanes Gorge natural area. It is a linear route of approximately 3 km (Figure 1b,c), with 1.5 km of walkways anchored to the rock faces in the gorge areas. The walkways are divided into two sections: near the northern access (Gaitanejos) and before the southern exit (Gaitanes). The gorge is a deep canyon with walls reaching up to 300 m high and barely 10 m wide. The area surrounding the Caminito del Rey is home to a large colony of birds of prey and griffon vultures and was declared a natural area in 1989. The trail was renovated between 2014 and 2015 and is managed by the Málaga Provincial Council through a joint venture of three companies. The area experiences constant rockfalls, evidenced by damage to the old footbridge, built between 1901 and 1905, and recent incidents affecting the new infrastructure. Examples of these recent events include a one-day closure in January 2018 due to various rockfalls [34], a week-long closure in October 2018 due to heavy rains, a February 2022 rockfall that cut off the south exit and forced visitors to turn around, and a December 2022 rockfall in the north that destroyed a large section of the footbridge [35] (Figure 1d). These rockfalls endanger the safety of visitors, workers, and infrastructure, prompting the Caminito del Rey management to propose a safety plan that includes a rockfall susceptibility study. In this context, a geomatics study was proposed to obtain a high-resolution 3D model, allowing for rockfall simulations and route classification by susceptibility. This document describes the geomatics study conducted in 2023 along the entire length of the Caminito del Rey and its surroundings.

Figure 1.

Location of the Caminito del Rey: (a) Provincial and local context; (b) Study area and walkway; (c) Study area divided by sectors; (d) View of the Gaitanejo Gorge illustrating the source area of a major rockfall event (December 2022); (e) View of the Los Gaitanes Gorge showing the visitors’ walkway anchored to the vertical wall.

1.2. Limitations of the Study Area

The study area presented significant challenges for implementing a geomatics project, especially given the objective of obtaining a high-density, high-precision 3D model. The first challenge arose from the large area to be covered (approximately 106 ha) (Figure 1b) and its accessibility, exclusively via the Caminito del Rey route itself, with a single entrance and exit on foot. The route is visited from Tuesday to Sunday by numerous tourists (more than 300,000 visitors in 2024), leaving Mondays solely for maintenance work. This posed a significant challenge for data capture, as work could not be conducted with visitors present due to the narrowness of certain walkway sections. Due to the size of the study area and the characteristics of the layout, the study area is divided into three sectors (Figure 1c): the first in the northern footbridge area (access to Caminito del Rey) in the Gaitanejo Gorge; the second in the Hoyo Valley; and the last in the southern footbridge area (exit from Caminito del Rey) in the Los Gaitanes Gorge. Regarding ground capture techniques, they were limited to a narrow strip of land near the route due to the area’s topography and, in many cases, had to be carried out exclusively from the walkway. This limitation made image capture extremely difficult, as complete coverage of the surrounding terrain is impossible from the walkway, and occlusions caused by the walkway itself (beneath it), the terrain, or existing vegetation are common (Figure 1e). Furthermore, the presence of large vertical walls hampered GNSS observations because maintaining correct satellite geometry was difficult in many areas (zone 1 and zone 3 in Figure 1c). This also caused the multipath effect due to signal bounce, affecting the positional quality of measurements. The lack of data coverage also prevented the reception of differential corrections via the internet.

Regarding aerial capture techniques, the difficulties increased considerably. First, due to the terrain’s topography, with its large slopes, vertical walls, and canyons only a few meters apart (zone 1 and zone 3 in Figure 1c); second, due to the presence of protected birds, which limited the use of these devices in certain areas. In gorge areas, the wind is often very strong, making work with UAVs difficult. Additionally, the terrain can cause the device to lose visibility even at short distances, and power lines are present in the northern area (zone 1). Higher altitude flights were also ruled out due to the proximity of the approach area to Malaga Airport. All these factors—including the extreme topography, safety restrictions, airspace limitations, and severe GNSS signal degradation—collectively rendered any geomatics project based on a single technique unfeasible for achieving the required centimetric resolution and complete coverage. This set of limitations conclusively demonstrated the necessity of developing and applying a robust multi-technique approach based on the cohesive fusion of complementary datasets to overcome the limitations of each individual sensor.

1.3. Objectives

The primary objective of this study is to develop and apply a novel, multi-technique methodology for the cohesive, centimetric-level fusion of heterogeneous geomatic datasets (UAV LiDAR/Photogrammetry, TLS, MMS, and SP) to achieve complete 3D documentation of complex scenes characterized by narrow gorges. This resulting documentation, specifically a 3D surface with centimeter-level resolution, is crucial for assessing rock stability and enabling geologists and engineers to determine rockfall risk areas and inform the implementation of stabilization, mitigation, and security measures.

A secondary objective is to validate the robustness and applicability of this proposed methodology by applying it to the extremely complex Caminito del Rey site, which serves as a significant, real-world benchmark for similar environments globally.

2. Methodology

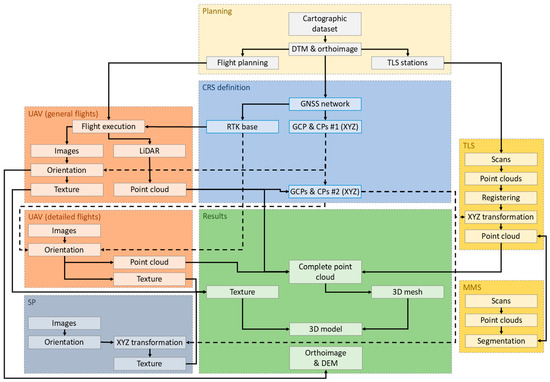

Considering the previously described objectives, the methodology proposed in this study employs a variety of instruments and capture methods, both aerial and ground-based, to obtain a complete coverage of the scene and a high resolution for the 3D model. With these premises in mind, the methodology proposed is summarized in Figure 2. In this approach, the considered geomatic methods integrate UAV LiDAR, UAV photogrammetry (both vertical and oblique at several flight levels), TLS, MMS and SP.

Figure 2.

Methodology proposed in this study.

2.1. Planning and Coordinate Reference System Definition

Initially, a preliminary analysis of the study area is performed using official cartographic sources (e.g., web services provided by the IGN of Spain) and field knowledge. The purpose is to plan data collection and select the techniques to be implemented for capturing detailed data in each zone (Figure 1c). In addition, flight planning and TLS stations can be initially planned from this initial data.

Secondly, the definition of an accurate and stable framework to reference all the information obtained with the different geomatic techniques (photogrammetry and LiDAR) for its subsequent data fusion in a correct and unambiguous way. In this context, a set of well-distributed topographic bases and targets must be selected and materialized, with a sufficient density to guarantee this objective. The coordinates of these points are obtained with a GNSS receiver by performing RTK observations, which achieves accuracies of about 1–2 cm. In cases where the accuracy demanded by the project must be higher, we suggest the definition of a GNSS network performing extended GNSS observations at each point, post-processing data and network adjustment incorporating precise ephemeris, atmospheric corrections, etc. The targets for the georeferencing include both GCPs for this task and checkpoints (CPs) to validating the accuracy of processing and products (GCPs and CPs #1 in Figure 2). The GNSS network obtained allows the implementation of GNSS-RTK bases to support the execution of UAV flights in those cases where this configuration is possible. In complex areas, the use of GNSS is sometimes not possible, requiring the implementation of other surveying techniques. Therefore, the UAV photogrammetric block can be used to determine a set of well-distributed GCPs used to georeferencing the merged TLS point cloud. This georeferencing is developed using a rigid 3D transformation [36]. The overall positional accuracy of this georeferencing and fusion process is finally validated using the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) computed at the Checkpoints (CPs).

2.2. UAV Flights

Taking into account the characteristics of scenes considered in this study that include narrow gorges, this methodology implies several UAV flights capturing data both from vertical and oblique point views to cover the entire topographic surface. In this sense, the presence of narrow spaces, reduced even to several meters between adjacent rockwalls, the irregular terrain surface and other issues will determine the type of UAV to be used the configuration of the flight and the sensors for acquiring data. In this concern, UAVs of higher size and payload, integrating both LiDAR and image sensors, are suitable for flights at higher altitudes (general flights in Figure 2) obtaining vertical images and point clouds from above (LiDAR sensor), while mini-UAVs have lower size and payload but they usually only integrate image sensors. These aircrafts are more adequate to flight between rockwalls due to their maneuverability taking vertical and oblique images (detailed flights in Figure 2). The first type allows flights executed following a planned route using GNSS-RTK for accurate aircraft positioning, while mini-UAVs’ flights are executed manually. The use of planning flights improves data acquisition efficiency and ensures photogrammetric quality by controlling distances sensor-object (scale) and overlaps [37]. Thus, in this approach general flights provide images and point clouds (LiDAR sensors). Images are oriented using SfM algorithm by considering the positions of the sensor at the capture obtained from GNSS-RTK and Inertial Navigation System (INS) data and supported by GCPs obtained from the GNSS network. Point clouds and oriented images are validated by using independent CPs measured with the same system. Oriented images can provide a texture of the scene that will compose the final texture to be included in the 3D model. Considering LiDAR sensors available in the market and the distance to the object with flights at about 60 m, the density of points is about 10 cm. Finally, the oriented images enable the generation of a general orthoimage and a Digital Elevation Model (DEM) of the study area. On the other hand, detailed flights are conducted to survey vertical rockwalls, areas with occlusions from vertical viewpoints or areas with a special interest to be surveyed at a higher resolution. Due to the difficulties of these areas these flights are usually executed manually, although some medium-size aircrafts allow the use of GNSS-RTK positioning to develop a previously planned trajectory. In this sense, the satellite coverage is commonly poor or null in these scenes, hindering the use of GNSS-RTK both to positioning and to support orientation of images. In these cases, or when the selected UAV does not integrate positioning systems, the use of GCPs is fundamental to georeference photogrammetric blocks. These GCPs and CPs are obtained from a second-order dataset (GCPs and CPs #2 in Figure 2) comprising previous targets (GCPs and CPs #1 in Figure 2) and additional well-defined points obtained from the general flight. Once the images are processed using SfM and MVS algorithms and georeferenced, the results include a texture and a point cloud of the scene. Additionally, all photogrammetric block (using and not using GNSS-RTK) can be processed together, without using second-order GCPs.

2.3. Terrestrial Laser Scanning and Mobile Mapping

TLS is used to obtain point clouds from accessible locations that complement those obtained from aerial LiDAR. The idea is to use these point clouds to define the geometry of the scene, using photogrammetry to provide the texture. The procedure involves the development of several scans from stable locations, ensuring sufficient overlap between adjacent stations. Overlaps between point clouds facilitate registration procedures, such as those employing the Iterative Closest Point (ICP) [38] algorithm. After registering, the merged point cloud is georeferenced by means of a rigid 3D transformation using several GCPs of the second dataset. Although TLS with high distance ranges and accuracy are available, capturing these complex scenes from stable stations often results in gaps and uncovered areas due to occlusions caused by terrain or artificial elements. In these cases, this approach incorporates the use of MMS for two primary goals: to provide a fast capture of the site and second, to ensure comprehensive coverage by changing viewpoints, leveraging the maneuverability of these systems, for example, by mounting them on masts. However, point clouds obtained using MMS can be affected by several issues (e.g., noise, drift, etc.) [39]. Noise can be reduced using statistic techniques and filters. To reduce trajectory drift problems inherent to SLAM-based MMS, our approach includes an iterative adjustment method. This method considers the registration of MMS point cloud segmentations against the highly accurate TLS point clouds, which serve as the geometric reference. This segmentation is refined iteratively until the discrepancies between them are lower than a certain threshold (e.g., about 2 cm) (Figure 2). Once these issues are solved, a selection of MMS points are included in those areas with gaps in TLS point clouds, resulting in a point cloud that complements those obtained from aerial techniques, forming a complete point cloud of the entire scene. This complete point cloud is used to generate a 3D mesh that defines the geometry of the scene, with a triangle mesh at a resolution defined by the project.

2.4. Spherical Photogrammetry

In addition to photogrammetric techniques previously described, our approach includes the application of SP from the ground by using a 360-degree camera mounted on a mast. This technique is used to avoid occlusions caused by the terrain or other artificial elements. The 360-degree camera provides multiple fisheye images obtained from its constituent sensors at each station. These fisheye images can be oriented using SfM algorithm as conventional images. However, these cameras have a fixed geometry, which can be precisely determined through a full camera calibration. This calibration provides the knowledge of the extrinsic parameters, allowing to use of calculated distances between sensors as constraints (scale bars) and facilitating orientation and scaling procedures [7]. In this case, the need for GCPs is minimized, primarily serving for a 3D transformation for georeferencing. After this procedure is finished, all blocks of images (UAV photogrammetry and SP) are merged to obtain a final texture of the scene. This texture is then applied to the 3D mesh to generate the final 3D model (Figure 2).

3. Application and Results

The application of the proposed methodology to the Caminito del Rey area, a highly challenging scenario, confirmed the necessity of the multi-sensor fusion strategy due to the site’s characteristics. The preliminary analysis, based on a DEM and an initial orthoimage (25 cm resolution) from the National Aerial Orthophotography Plan (PNOA) of the Instituto Geográfico Nacional of Spain (IGN) [40], was crucial for planning the complex acquisition works and determining the optimal combination of geomatic techniques for each zone.

3.1. Data Acquisition

Following the preliminary analysis, the first step was to define a precise and stable reference system to enable data fusion from the different capture techniques (photogrammetry and LiDAR). In this context, topographic bases and a series of targets for the georeferencing of partial data were developed, sufficiently distributed to guarantee this objective. The coordinates of the topographic bases were obtained with the GNSS receiver by performing an RTK observation (Figure 3a) based on the Andalusian Positioning Network (RAP), while those relative to the targets (GCPs) were generally measured also with this technique, and were additionally densified in the most complicated areas from the point clouds derived from photogrammetry and TLS, given the difficulties with GNSS-RTK coverage.

Figure 3.

Examples of the techniques used: (a) Control point surveying with GNSS-RTK; (b) vertical flight with a DJI Zenmuse L1 UAV; (c) Wall flight with a DJI Phantom 4 RTK UAV; (d) TLS with a FARO Laser Scanner Focus3D S350; (e) Handheld MMS with a Leica BLK2GO; (f) Photogrammetry with a 360-degree Kandao Obsidian S multi-camera.

The next phase included general UAV flights to obtain point clouds, high-resolution digital models and orthoimages. The system used was the DJI Matrice 300 RTK (Shenzhen, China) UAV (Figure 3b), which features an optical sensor, a LiDAR sensor (DJI Zenmuse L1, Shenzhen, China), and various sensors that enable centimeter-level positioning. Given the characteristics and complexity of the area, different takeoff points and flight heights had to be defined, necessitating a total of 20 flights. This yielded 3677 images and over one billion points. This data formed the foundation of the dense point cloud for the areas of interest, which was then completed and/or densified in the required areas using non-vertical capture techniques, both aerial and ground-based. For aerial capture of vertical walls, a series of manual flights with vertical and oblique perspectives were conducted to capture data in areas not covered by the vertical survey and in areas requiring higher resolution for subsequent detailed analysis. In this phase, the DJI Phantom 4 RTK (Figure 3c) and DJI Mavic Mini (Shenzhen, China) UAVs were used, capturing more than 4800 photographs in 24 flights.

In addition, to achieve high-resolution coverage and fill potential gaps in areas of interest left by previous capture methods, point clouds and high-density, high-resolution images were acquired using LiDAR and terrestrial photogrammetric techniques, both mobile and static. Thus, considering LiDAR techniques, the use of two TLS devices with a range of 130 and 350 m was primarily limited to capture from the footbridge, although in parts of Sector 3 it was possible to operate from the railway platform located on the east side of the gorge (Figure 3d). Capture was carried out with high density and avoiding the capture of radiometric data in order to reduce acquisition time. Scanning positions considered the obtaining of large overlaps between adjacent point clouds to ensure a successful relative registration. With the TLS systems, 230 scans were performed, yielding a cloud of almost 3.5 billion points. In the case of the handheld MMS system, its integrated LiDAR capture is limited to 25 m. This limitation and the problems with trajectory drift necessitated capture using small, closed rings, which allowed for subsequent calibration and data readjustment processes. The equipment was mounted on a telescopic mast up to 8 m long to separate the sensor from the footbridge to scan areas above and below it (Figure 3e). With this configuration, 48 scans were performed with a total of about 2.4 billion points.

Finally, the ground-based photogrammetry phase was carried out with a 360-degree multi-camera (Figure 3f) located on the telescopic mast, with the primary objective of capturing images for the model’s texture in uncovered areas by UAV photogrammetry. Stations were distributed with a separation of about 3–5 m to ensure large overlaps and similar perspectives between adjacent images. More than 1200 captures were taken with this device, representing 7200 fisheye images.

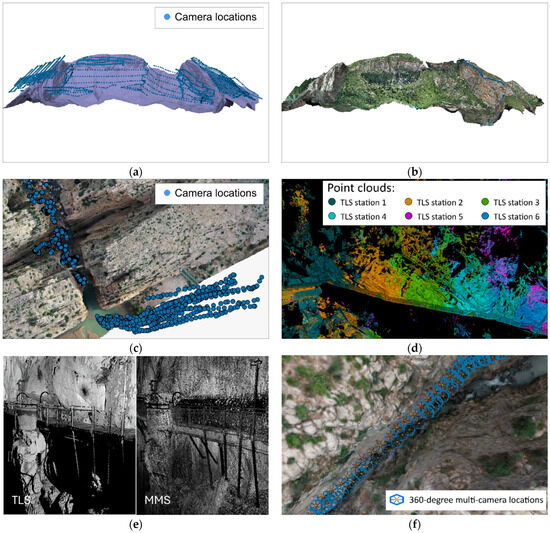

3.2. Data Processing

Data processing pursued three primary objectives: verifying and completing the data capture, generating comprehensive products, and adapting them to the resolution and density requirements. The processing was carried out specifically for each technique, although in the final phases a fusion of the data obtained with each was performed. In the case of the vertical UAV flights (phase 2), photogrammetric orientation was performed using Agisoft Metashape v 2.2.1 software, leveraging GNSS-RTK positioning of the images and the GCPs (targets previously measured in phase 1) (Figure 4a). The LiDAR data were processed in two stages: the first using DJI Terra v 4.2.5 software to define the system’s trajectory and generate the point cloud; the second using BayesMap StripAlign v 2.24 software to adjust strips and reduce noise within the point cloud (Figure 4b). Second-order GCPs were extracted from the point cloud, which were subsequently used for the remaining processes. For the detailed UAV flights (phase 3), processing (Figure 4c) was performed with these second-order points and with the images oriented in phase 2, merging the various image blocks obtained with all the UAVs. The processing of phases 2 and 3 resulted in a point cloud with an average density of 10 cm, a series of DEMs, more specifically digital surface models (DSMs), a set of orthoimages, and a set of second-order GCPs. For the TLS data, the scans were registered and validated using Maptek PointStudio v 2024 software (Figure 4d) with an accuracy of about 1 cm. This process was performed zonally to minimize error propagation, with error correction validated within each zone. Georeferencing was performed in two steps, using a rigid 3D transformation from the points extracted from the scanner and the second-order control points (phase 2), and a global registration between the cloud obtained in phase 2 and the clouds obtained with TLS (using ICP algorithm [38]). MMS was registered against TLS point clouds by segmented each point cloud to mitigate drift errors. This segmentation was iteratively refined until the error fell below a certain threshold (about 2 cm). Figure 4e shows an example of both point clouds from the same viewpoint once that obtained with MMS is registered. Finally, SP data was processed using Agisoft Metashape software by incorporating scale bars derived from the distances between the six sensors of the camera (Figure 4f). The distances between sensors were previously determined through a complete calibration of the camera. These constraints facilitate orientation procedures minimizing the number of GCPs needed to those required to perform a 3D transformation.

Figure 4.

Examples of the processing performed: (a) general UAV image location; (b) LiDAR UAV point cloud; (c) detailed UAV image location; (d) TLS point clouds registration; (e) TLS and MMS point clouds; (f) SP images location after orientation.

Once the point clouds were recorded, they were classified into terrain and non-terrain points, considering terrain as everything other than vegetation (terrain, rocks, canyon walls, and the footbridge). This phase was performed semi-automatically using the classification and manual editing tools of Lastools and Maptek PointStudio software 2025. The result of this phase was the DTMs of the study area, which are free of points related to vegetation. The final point cloud, which would be used to generate the 3D model, was obtained by merging all the previous clouds. To do this, before performing the merging, the normals for each dataset had to be calculated considering their respective origin (TLS points) and trajectories (UAV LiDAR). For data merging, data quality was prioritized over density and extraneous information it contained (RGB, intensity, return, etc.). Therefore, the final, merged point cloud was composed primarily of the point cloud from TLS, which provided the highest precision and detailed coverage of the vertical walls. In areas not covered by TLS (mainly upper areas and the valley floor), points from the UAV LiDAR and MMS were added. Subsequently, high-resolution points from the detailed UAV photogrammetry blocks were integrated to densify specific areas of interest, ensuring homogeneity in terms of density and spacing. Once the data was merged, distance filtering was performed, yielding a cloud that was homogeneous in terms of density and spacing. From the merged point cloud, combined with the photogrammetric orientation of all blocks (vertical and oblique) and considering the proposed sector division, the textured 3D model was generated using Maptek PointStudio (3D models) and Agisoft Metashape (texturing) software. The rigorous georeferencing and multi-sensor fusion methodology was validated using checkpoints (CPs). The positional accuracy of the final 3D model was confirmed to be below the resolution of the demanded products (10 cm of point clouds and DEMs and 5 cm of orthoimages).

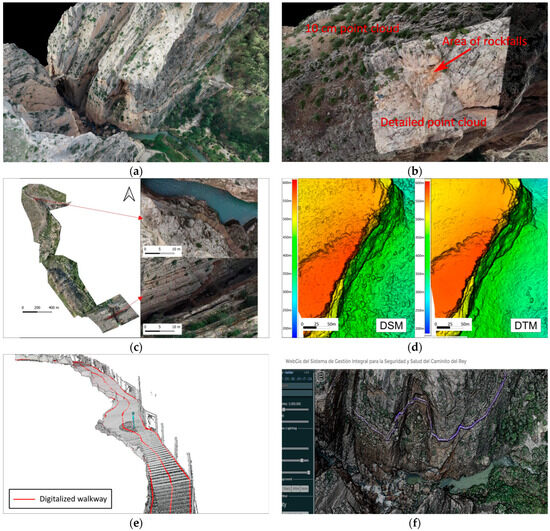

3.3. Products

This study has yielded important results, both in terms of products and methodology. In the first case, the study provided a high-resolution 3D model (Figure 5a) for studying rockfalls susceptibility. From this model, not only can 3D simulation techniques be applied to determine the most susceptible areas, but the centimetric resolution also allows geologists to identify, characterize, and digitalize critical rock discontinuities (e.g., joint sets), which are fundamental inputs for kinematic analysis and risk mitigation mechanisms. In addition, ground-filtered point clouds at 50 cm, distance-filtered point clouds at 10 cm (Figure 5b), and more detailed original point clouds of some areas of interest (Figure 5b) were obtained. In addition, orthoimages with a 5 cm resolution (Figure 5c) and digital elevation models with a 25 cm resolution were obtained, enabling the use of 2.5D rockfalls simulation techniques [4]. These DEMs consider the vegetated surface (VS) and the ground surface (TS) (Figure 5d). Furthermore, the walkway was digitized from the TLS point cloud, considering its edges and axis. The process consisted of selecting the points belonging to the walkway and manually digitizing its edges. The results obtained were a 3D polyline where the outer edge vertices correspond to the railing posts (Figure 5e). Finally, all products were also exported in various formats for management through geographic information systems using WebGIS platforms. Thus, a geoportal (Figure 5f) was developed based on libraries and frameworks such as Geoserver, Cesiumjs, Leaflet, and Potreejs, among others, for data visualization and access. Any non-specialized user can access all the generated products (2D and 3D) and even perform small analyses and annotations.

Figure 5.

Examples of results obtained: (a) Textured 3D model; (b) 10 cm point cloud and detailed point cloud; (c) orthoimages; (d) DSM and DTM; (e) digitalized walkway over the point cloud; (f) geoportal with point cloud and walkway.

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparative Analysis of the Multi-Technique Approach

Regarding methodological aspects, the difficulties of the study area and the project requirements necessitated the use of various data capture techniques, integrating data obtained from each source while always considering their efficiency and accuracy. In defining the coordinate reference system, the difficulties in measuring control points with topographic techniques and GNSS-RTK led to the extraction of a series of second-order points from other techniques. This approach of using high-accuracy LiDAR/Photogrammetry data as secondary control has proven efficient, as it significantly reduced extensive fieldwork and achieved sufficient accuracy (validated via checkpoints) to ensure the correct orientation of the detailed photogrammetric blocks. Determining the geometry by integrating LiDAR data (aerial and terrestrial) has allowed for the creation of a point cloud with high density and geometric accuracy, as well as practically complete coverage of the site, leaving image capture and texturing to photogrammetric techniques (aerial and terrestrial). Processing the blocks in a single project facilitated image orientation, reducing the need for control points. Furthermore, the use of devices such as the 360-degree multi-camera for terrestrial photographic capture has been very interesting, allowing the capture of areas hidden by other techniques and demonstrating great efficiency in image acquisition. The use of extrinsic calibration parameters for fisheye images [7] greatly facilitates photogrammetric orientation tasks. Finally, the use of MMS devices presents great capture efficiency, although range limitations require their use in closed or close areas, and drift problems lead to capture in closed rings. The iterative registration of MMS segments against high-accuracy TLS point clouds was essential for mitigating SLAM-based drift errors, achieving final discrepancies below the 2 cm threshold required for the final product.

4.2. Limitations and Uncertainty Management

Despite the successful implementation of the multi-technique approach, some limitations were identified, primarily related to data volume management and processing capacity. The sheer volume of data acquired (over 20 billion points) presented a significant challenge, requiring substantial computational resources and processing time. While the generated products met the project’s requirements, optimizing the balance between data acquisition density and processing efficiency remains an area for improvement. Specific filtering techniques (e.g., statistical outlier removal, distance filtering) were implemented to manage noise and reduce data volume while preserving centimetric resolution in critical zones. Another limitation observed was the occasional difficulty in maintaining consistent GNSS-RTK coverage in the deepest and narrowest sections of the gorge, despite the robust control network. This occasionally led to a greater reliance on terrestrial techniques and necessitated careful post-processing for optimal georeferencing. The reliance on geometric registration techniques (ICP, iterative MMS adjustment) in these specific zones introduces local uncertainties. Although the final accuracy, validated by checkpoints, was acceptable for the project’s goals, a formal, spatially explicit uncertainty propagation analysis (from input sensor errors to the final 3D model) remains an area for future research to fully quantify the accuracy of the fusion product.

4.3. Generalizability and Practical Application

The resulting high-resolution 3D model is directly applicable to improving safety management, as it enables advanced kinematic analysis and numerical rockfall simulations. Beyond the Caminito del Rey, the validated multi-technique methodology holds significant generalizability for similar complex scenarios globally, such as canyon roads, railway slopes, dam faces, and other critical infrastructures in geologically active terrain.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a novel, multi-technique methodological framework for the complete graphical documentation of complex narrow gorges. The proposed methodology successfully integrates heterogeneous geomatic techniques (UAV LiDAR/Photogrammetry, TLS, MMS, and SP) to leverage the complementary advantages of each sensor, thereby overcoming the geometric challenges inherent to these scenes. This integration allows for the generation of high-resolution products, which are fundamental for assessing rock stability. This is possible thanks to the proposal of detailed acquisition techniques based on mini-UAVs, TLS and MMS. The main challenge in this type of studies is the need to efficiently merge all data from different sources into a single reference system, and the proposed methodology achieves this goal rigorously.

The application of the proposed methodology for the modeling of the Caminito del Rey has demonstrated the feasibility of this approach to achieve all goals. In our case, this has proven as a large-scale geomatics project, both due to the size of the area, the challenges encountered (orographic, access, flight limitations, presence of visitors, etc.), and the demanding resolution and precision requirements of the final products. This challenge required the application of numerous geomatics techniques, both aerial and terrestrial, with varying characteristics and precisions for its successful completion. The application of the proposed methodology allowed for the production of homogeneous density products, which facilitate simulations and rockfall susceptibility studies. In this sense, the fusion of data from the different techniques was a fundamental aspect in obtaining these products, considering the potential of each. Thus, the geometry of the 3D model was obtained from point clouds obtained with LiDAR techniques (ALS and TLS), while the texture was created from photogrammetry (UAV and terrestrial). Detailed point clouds have also been used to determine control points, reducing the need for surveying techniques. The final model obtained could be considered the basis for a digital twin of the Caminito del Rey, which could be used for future analyses and interventions.

In the future, work will focus on automating the iterative fusion process developed in this study, particularly for trajectory refinement and drift correction of low-cost MMS devices. Furthermore, a detailed uncertainty propagation analysis from the multi-sensor inputs to the final 3D model will be conducted to fully quantify the accuracy gains provided by the cohesive integration approach.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, All authors; methodology, All authors; software, All authors; validation, All authors; formal analysis, All authors; investigation, All authors; resources, All authors; data cu-ration, All authors; writing—original draft preparation, A.T.M.-C.; writing—review and editing, All authors; visualization, All authors; supervision, All authors; project administration, J.L.P.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Caminito del Rey staff for their support during the data acquisition process, to Sando and Diputación de Málaga for their support and CEACTEMA (University of Jaén) for its resources. During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used Gemini v. 2.5 for the purposes of English style checking. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ALS | Airborne Laser Scanning |

| C2C | Cloud-to-cloud distance |

| C2M | Cloud-to-mesh or cloud-to-model distance |

| CP | Checkpoint |

| CRP | Close Range Photogrammetry |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| DoD | DEM of Difference |

| DSM | Digital Surface Model |

| DTM | Digital Terrain Model |

| GCPs | Ground Control Points |

| GNSS | Global Navigation Satellite Systems |

| ICP | Iterative Closest Point |

| IGN | Instituto Geográfico Nacional (National Geographic Institute of Spain) |

| INS | Inertial Navigation System |

| LiDAR | Light Detection and Ranging |

| M3C2 | Multiscale Model to Model Cloud Comparison |

| MMS | Mobile Mapping Systems |

| MVS | Multi-View Stereo |

| PNOA | Plan Nacional de Ortofotografía Aérea (National Aerial Orthophotography Plan) |

| RAP | Red Andaluza de Posicionamiento (Andalusian Positioning Network) |

| RTK | Real Time Kinematic |

| SFM | Structure from Motion |

| SLAM | Simultaneous Localization and Mapping |

| SP | Spherical Photogrammetry |

| TLS | Terrestrial Laser Scanning |

| TS | Ground Surface |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| VS | Vegetated Surface |

References

- Cruden, D.M.; Varnes, D.J. Landslide Types and Processes. In Landslides and Engineering Practice; Turner, A.K., Schuster, R.L., Eds.; Special Report, 247, 36–75, Transportation Research Board; US National Academy of Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, 1996; Volume 24, pp. 20–47. [Google Scholar]

- Guzzetti, F.; Reichenbach, P. Rockfalls and their hazard. In Tree Rings and Natural Hazards: A State-of-Art, 1st ed.; Stoffel, M., Bollschweiler, M., Butler, D.R., Luckman, B.H., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 129–137. [Google Scholar]

- Lague, D.; Brodu, N.; Leroux, J. Accurate 3D comparison of complex topography with terrestrial laser scanner: Application to the Rangitikei canyon (NZ). ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2013, 82, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, H.; Martin, C.D.; Lim, C.H. RockFall analyst: A GIS extension for three-dimensional and spatially distributed rockfall hazard modeling. Comput. Geosci. 2007, 33, 262–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, J.; Li, Z.; Lercel, D.; Tissue, K.; Hupy, J.; Carpenter, J. Democratizing photogrammetry: An accuracy perspective. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, 26, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, F.; Chiappini, S.; Gorreja, A.; Balestra, M.; Pierdicca, R. Mobile 3D scan LiDAR: A literature review. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2021, 12, 2387–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-García, J.L.; Gómez-López, J.M.; Mozas-Calvache, A.T.; Delgado-García, J. Analysis of the Photogrammetric Use of 360-Degree Cameras in Complex Heritage-Related Scenes: Case of the Necropolis of Qubbet el-Hawa (Aswan Egypt). Sensors 2024, 24, 2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fangi, G. The multi-image spherical panoramas as a tool for architectural survey. In Proceedings of the 21st CIPA Symposium, Athens, Greece, 1–6 October 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Samadzadegan, F.; Toosi, A.; Dadrass Javan, F. A critical review on multi-sensor and multi-platform remote sensing data fusion approaches: Current status and prospects. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2024, 46, 1327–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Jiang, N.; Li, C.; Li, H. A Landslide Monitoring Method Using Data from Unmanned Aerial Vehicle and Terrestrial Laser Scanning with Insufficient and Inaccurate Ground Control Points. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2024, 16, 4125–4140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abellán, A.; Vilaplana, J.M.; Martínez, J. Application of a long-range Terrestrial Laser Scanner to a detailed rockfall study at Vall de Núria (Eastern Pyrenees, Spain). Eng. Geol. 2006, 88, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, D.; Corominas, J.; Mavrouli, O.; Garcia-Sellés, D. Magnitude–frequency relation for rockfall scars using a Terrestrial Laser Scanner. Eng. Geol. 2012, 145, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeras, M.; Jara, J.A.; Royan, M.J.; Vilaplana, J.M.; Aguasca, A.; Fabregas, X.; Gili, J.A.; Buxó, P. Multi-technique approach to rockfall monitoring in the Montserrat massif (Catalonia, NE Spain). Eng. Geol. 2017, 219, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Y.; Li, H.B.; Yang, X.G.; Jiang, N.; Zhou, J.W. Quantitative assessment of rockfall hazard in post-landslide high rock slope through terrestrial laser scanning. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2021, 80, 7315–7331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birien, T.; Gauthier, F. Assessing the relationship between weather conditions and rockfall using terrestrial laser scanning to improve risk management. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 23, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, G.; Malsam, A.; Oester Mapes, N.; Arpin, B. Forecasting and mitigating rockfall based on lidar monitoring: A case study from Colorado. Transp. Res. Rec. 2023, 2677, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lato, M.; Hutchinson, J.; Diederichs, M.; Ball, D.; Harrap, R. Engineering monitoring of rockfall hazards along transportation corridors: Using mobile terrestrial LiDAR. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2009, 9, 935–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, H.; Martin, C.D.; Zhou, C.; Lim, C.H. Rockfall hazard analysis using LiDAR and spatial modeling. Geomorphology 2010, 118, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notti, D.; Giordan, D.; Cina, A.; Manzino, A.; Maschio, P.; Bendea, I.H. Debris flow and rockslide analysis with advanced photogrammetry techniques based on high-resolution RPAS data. Ponte Formazza case study (NW Alps). Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, F.Z.; Zhao, L.; Deng, N.; Chen, L.; Pan, J.S.; Tang, G.Q. Rockfall feature investigation and kinematic simulation based on nap-of-the-object photogrammetry and GIS spatial modeling. Nat. Hazards 2023, 118, 239–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakar, M.; Ulvi, A.; Yiğit, A.Y.; Alptekin, A. Discontinuity set extraction from 3D point clouds obtained by UAV Photogrammetry in a rockfall site. Surv. Rev. 2023, 55, 416–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirillo, D.; Zappa, M.; Tangari, A.C.; Brozzetti, F.; Ietto, F. Rockfall Analysis from UAV-Based Photogrammetry and 3D Models of a Cliff Area. Drones 2024, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zeng, B.; Zhao, H.; Yuan, J.; Ai, D. Structure plane interpretation of rockfall and early identification of potential hazards based on UAV photogrammetry. Nat. Hazards 2024, 121, 1779–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckmann, T.; Bimböse, M.; Krautblatter, M.; Haas, F.; Becht, M.; Morche, D. From geotechnical analysis to quantification and modelling using LiDAR data: A study on rockfall in the Reintal catchment, Bavarian Alps, Germany. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2012, 37, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lato, M.J.; Diederichs, M.S.; Hutchinson, D.J.; Harrap, R. Evaluating roadside rockmasses for rockfall hazards using LiDAR data: Optimizing data collection and processing protocols. Nat. Hazards 2012, 60, 831–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvini, R.; Francioni, M.; Riccucci, S.; Bonciani, F.; Callegari, I. Photogrammetry and laser scanning for analyzing slope stability and rock fall runout along the Domodossola–Iselle railway, the Italian Alps. Geomorphology 2013, 185, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarro, R.; Riquelme, A.; García-Davalillo, J.C.; Mateos, R.M.; Tomás, R.; Pastor, J.L.; Cano, M.; Herrera, G. Rockfall Simulation Based on UAV Photogrammetry Data Obtained during an Emergency Declaration: Application at a Cultural Heritage Site. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanneschi, C.; Di Camillo, M.; Aiello, E.; Bonciani, F.; Salvini, R. SFM-MVS photogrammetry for rockfall analysis and hazard assessment along the ancient roman via Flaminia road at the Furlo gorge (Italy). ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žabota, B.; Berger, F.; Kobal, M. The Potential of UAV-Acquired Photogrammetric and LiDAR-Point Clouds for Obtaining Rock Dimensions as Input Parameters for Modeling Rockfall Runout Zones. Drones 2023, 7, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Bao, H.; Zhang, J.; Lan, H.; Adriano, B.; Koshimura, S.; Yuan, W. Accurate Digital Reconstruction of High-Steep Rock Slope via Transformer-Based Multi-Sensor Data Fusion. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.-L.; Jiang, N.; Li, H.-B.; Xiao, H.-X.; Chen, X.-Z.; Zhou, J.-W. A High-Precision Modeling and Error Analysis Method for Mountainous and Canyon Areas Based on TLS and UAV Photogrammetry. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 7710–7724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Wang, R.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Xiao, Z.; Lin, J. High-Resolution Terrain Reconstruction of Slot Canyon Using Backpack Mobile Laser Scanning and UAV Photogrammetry. Drones 2022, 6, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhu, L. A review on unmanned aerial vehicle remote sensing: Platforms, sensors, data processing methods, and applications. Drones 2023, 7, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diario Sur. Available online: https://www.diariosur.es/interior/caminito-cierra-sabado-20180106103518-nt.html (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- ABC. Available online: https://sevilla.abc.es/andalucia/malaga/desprendimientos-tiempo-destrozan-tramo-pasarelas-caminito-20221213143802-nts.html (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- DeWitt, B.A.; Wolf, P.R. Elements of Photogrammetry (with Applications in GIS), 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill Higher Education: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-López, J.M.; Pérez-García, J.L.; Mozas-Calvache, A.T.; Delgado-García, J. Mission Flight Planning of RPAS for Photogrammetric Studies in Complex Scenes. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Iterative closest point (ICP). In Computer Vision: A Reference Guide, 1st ed.; Ikeuchi, K., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 718–720. [Google Scholar]

- Elhashash, M.; Albanwan, H.; Qin, R. A review of mobile mapping systems: From sensors to applications. Sensors 2022, 22, 4262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plan Nacional de Ortofotografía Aérea (PNOA). Available online: https://pnoa.ign.es/ (accessed on 29 July 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).