Highlights

What are the main findings?

- We propose a weakly supervised method for oriented SAR ship detection that generates optimized pseudo-labels to guide the training process.

- The method uses only HBB labels to train an OBB detector, achieving performance and efficiency comparable to fully supervised methods.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- The method effectively solves the problem of scarce OBB annotations, providing a practical solution for SAR ship oriented detection.

- The algorithm balances performance and efficiency, making it suitable for real-world applications on resource-limited platforms.

Abstract

In recent years, data-driven deep learning has yielded fruitful results in synthetic aperture radar (SAR) ship detection; weakly supervised learning methods based on horizontal bounding boxes (HBBs) train oriented bounding box (OBB) detectors using HBB labels, effectively addressing scarce OBB annotation data and advancing SAR ship OBB detection. However, current methods for oriented SAR ship detection still suffer from issues such as insufficient quantity and quality of pseudo-labels, low inference efficiency, large model parameters, and limited global information capture, making it difficult to balance detection performance and efficiency. To tackle these, we propose the weakly supervised oriented SAR ship detection algorithm based on optimized pseudo-label generation and guidance. The method introduces pseudo-labels into a single-stage detector via a two-stage training process: the first stage coarsely learns target angles and scales using horizontal bounding box weak supervision and angle self-supervision, while the second stage refines angle and scale learning guided by pseudo-labels, improving performance and reducing missed detections. To generate high-quality pseudo-labels in large quantities, we propose three optimization strategies: Adaptive Kernel Growth Pseudo-Label Generation Strategy (AKG-PLGS), Pseudo-Label Selection Strategy based on PCA angle estimation and horizontal bounding box constraints (PCA-HBB-PLSS), and Long-Edge Scanning Refinement Strategy (LES-RS). Additionally, we designed a backbone and neck network incorporating window attention and adaptive feature fusion, effectively enhancing global information capture and multiscale feature integration while reducing model parameters. Experiments on SSDD and HRSID show that our algorithm achieves an mAP50 of 85.389% and 82.508%, respectively, with significantly reduced model parameters and computational consumption.

1. Introduction

Synthetic aperture radar (SAR) is essential for traffic management, environmental monitoring, and maritime target detection due to its all-weather, all-time active sensing capabilities [1,2,3,4,5,6]. SAR ship detection is critical for navigation safety, fishery management, and emergency rescue, making it a key topic of remote sensing research [7]. Early methods relied mainly on traditional approaches such as Constant False Alarm Rate (CFAR) [8], Superpixel-Level detection [9,10], and handcrafted feature detection [11], but struggled with complex backgrounds and limited generalization. Currently, data-driven deep learning has advanced SAR ship detection, with horizontal bounding box (HBB) localization performance near saturation [12,13,14,15], but oriented bounding box (OBB) methods for precise localization are limited by scarce annotated datasets [16,17,18]. Creating large-scale SAR ship OBB datasets is resource-heavy [19,20], so weakly supervised learning—training OBB detectors with HBB labels—has become vital to overcome data constraints, cutting dataset costs and enabling high-precision OBB detection.

Yue et al. [21] (2024) first introduced a weakly supervised method for SAR ship OBB detection, which employs HBB-based loss functions to constrain the position and scale of OBBs. The approach further generates pseudo-labels from HBB chips through threshold segmentation and rotating calipers, facilitating a coarse-to-fine training strategy. It achieves performance comparable to fully supervised methods on HRSID but has limitations:

- Pseudo-label generation and selection lack adaptability to individual targets, resulting in fewer, lower-quality pseudo-labels and limited detection performance.

- The two-stage architecture and single-stage training have low efficiency and large parameters, failing to meet cost control requirements in dataset construction.

- The CNN-based backbone and neck cause redundant parameters and insufficient global information, restricting performance.

In pseudo-label generation and selection, accurate estimation of target angle and scale is essential for obtaining high-quality supervision. While Principal Component Analysis (PCA) has demonstrated effectiveness in estimating SAR target orientations [22] and shows promise for angle-based screening, it can be further complemented by leveraging geometric properties of HBBs. Specifically, the diagonal angle, diagonal length, and central cut-line length of an HBB are intrinsically related to the orientation and scale of the corresponding OBB. Therefore, an HBB-based quality assessment method can effectively enhance the reliability of pseudo-labels in terms of angle and scale estimation. In generating OBB pseudo-labels for SAR ships, the kernel size of morphological closing constitutes a key factor in eliminating target internal voids and increasing high-quality pseudo-labels. Assigning optimal kernel sizes to different target types can further enhance performance. Moreover, for certain defocused SAR targets exhibiting an excessively long short side, designing targeted refinement strategies represents another crucial approach to improving pseudo-label quality.

In terms of model architecture and training methods, single-stage detection architectures exhibit higher computational efficiency and a smaller parameter scale than two-stage architectures [23]. Most existing weakly supervised OBB detection methods for optical remote sensing images are based on single-stage architectures and have achieved high detection performance on optical datasets [24,25,26]. These approaches typically employ HBB-based weakly supervised loss to constrain OBB position and scale, along with self-supervised loss derived from image rotation and flipping to learn object angles. Replacing the two-stage architecture in Yue et al.’s method with a single-stage detector, while incorporating angle self-supervision, is expected to improve computational efficiency, reduce model parameters, and enhance OBB angle estimation, thereby leading to better detection performance. Additionally, the difficulty in generating high-quality pseudo-labels for specific targets can lead to increased missed detections under pure pseudo-label supervision. To address this, Yue et al. introduced a coarse-to-fine paradigm in a two-stage framework. Inspired by their work, we adapt this concept into a two-stage training regime for single-stage detectors, beginning with coarse scale and angle learning from HBBs and self-supervision, and culminating in refinement with high-quality pseudo-labels.

In terms of model backbone and neck structures, existing convolutional neural network (CNN)-based detection models have achieved a balance between parameter scale, computational efficiency, and detection performance through structural improvements and adjustments [27,28,29]. YOLO-series models, with their excellent detection performance and efficiency, are widely used in fully supervised synthetic aperture radar (SAR) ship detection [30,31,32]. Current studies often use Transformer [33] and its variants [34,35,36,37] to address the insufficient global information acquisition of convolutional structures. Among these, methods that replace the backbone with a Transformer variant—due to their high computational efficiency—are widely applied in fully supervised SAR ship detection [38,39]. Thus, improving the backbone and neck structures of Yue et al.’s model by adopting existing YOLO-series architectures and Transformer variants has potential to reduce parameter scale, enhance computational efficiency, and improve global information acquisition.

Based on the above analysis, we proposed a weakly supervised SAR ship oriented-detection algorithm based on pseudo-label generation optimization and guidance. This algorithm employed a two-stage training method that integrated pseudo-labels into the training of a single-stage detection model to reduce parameter scale and enhance detection performance and efficiency. In the first stage, the model used HBB weak supervision and angle self-supervision to achieve coarse learning of target angles and scales. In the second stage, we utilized the proposed pseudo-label optimization strategies—including Adaptive Kernel Growth for Pseudo-Label Generation (AKG-PLGS), a Pseudo-Label Selection Strategy based on PCA and HBB constraints (PCA-HBB-PLSS), and a Long-Edge Scanning Refinement Strategy (LES-RS)—to obtain high-quality pseudo-labels for model fine-tuning, which improved detection accuracy and reduced missed detections. Additionally, to reduce the backbone’s parameter scale and computational cost while enhancing semantic acquisition, we integrated a windowed attention mechanism with select YOLOv8 backbone layers via parallel structures and adaptive fusion. The feature fusion capability of the neck was also boosted through top-down adaptive integration. A series of experiments on the HRSID and SSDD datasets verified the effectiveness of our proposed method, which achieved detection performance comparable to mainstream fully supervised algorithms on the HRSID dataset. Our main contributions are as follows:

- We proposed a weakly supervised learning algorithm based on pseudo-label generation optimization and guidance for SAR ship oriented detection, which introduces pseudo-labels into single-stage detection models via a two-stage training method. This approach reduces computational cost and miss rate while improving detection accuracy.

- We designed three novel strategies for pseudo-label generation and optimization—AKG-PLGS, PCA-HBB-PLSS, and LES-RS—to enhance both the quality and quantity of pseudo-labels. These strategies effectively guide the fine-tuning process in the second training stage, leading to superior detection performance.

- We introduced a hybrid architecture that augments the backbone with window-based attention to overcome the locality constraint of pure convolution, thereby enhancing global context capture; it refines the neck with an adaptive top-down fusion mechanism to mitigate feature conflicts and ensure semantic consistency across scales.

2. Related Works

2.1. Fully Supervised HBB Detection

HBB detection models are divided into single-stage and two-stage detectors. Two-stage detectors like R-CNN [40], Faster-RCNN [41], and Cascade-RCNN [42] have large model sizes and low inference efficiency due to their complex structures. In contrast, single-stage detectors such as CornerNet [43], ExtremeNet [44], CenterNet [45], FCOS [46], and YOLO [47] are simpler and more efficient. YOLO, in particular, has led to many improved algorithms for SAR ship detection due to its frequent updates and open-source ecosystem. Among these, YOLOv8 [48] stands out with its C2f module that integrates rich gradient-flow information, significantly enhancing feature extraction ability and detection performance. Therefore, the backbone structure of YOLOv8 serves as a reference for the CNN part of our backbone network improvement.

The models mentioned above are predominantly based on convolutional neural networks (CNNs), which are inherently limited in capturing global contextual information. To address this, recent studies have incorporated Transformer architectures. These improvements fall into two main categories: (1) integrating a Transformer encoder–decoder into the model’s neck for feature fusion, as seen in DETR [49], DINO [50], and DAB-DETR [51]; and (2) employing a Transformer encoder or its variants as the model backbone, exemplified by ViT-FRCNN [52], Swin-Transformer [35], PVT [34], and FPT [53]. Among these, Swin-Transformer has gained wide adoption by maintaining global modeling capability while reducing computational costs through the incorporation of visual priors. The more recent Swin-TransformerV2 [54] further enhances training stability and feature extraction by introducing residual post-normalization and a cosine attention mechanism. It also diminishes reliance on large-scale annotated datasets via an improved position encoding method. Therefore, Swin-TransformerV2 serves as a valuable reference for improving our backbone to better balance semantic information acquisition with computational efficiency.

Following the prevailing practice in fully supervised detection, we adopt the FPN [55] design paradigm to construct a compatible neck structure for our backbone.

2.2. Fully Supervised OBB Detection

Current fully supervised OBB detection models have similar structural explorations to the fully supervised HBB detection models. For example, Oriented R-CNN [56] and FCOSR [57] have explored improvements in two-stage and single-stage OBB detection, while ARS-DETR [58], O2DETR [59], and PVT-SAR [39] have explored the application of Transformer in OBB detection.

However, OBB detection research focuses more on the boundary discontinuity problem caused by angle periodicity. This issue manifests as significant angle deviations between the model’s predicted box and the ground-truth label when detecting boundary angle targets. The methods to alleviate this problem can be divided into three main categories: (1) transforming angle prediction from a regression problem to a classification problem, such as in CSL [60], DCL [61], and GFL [62]; (2) jointly optimizing the angle and position information of labels through specific loss functions, such as in GWD [63], KLD [64], and KFIoU [65]; and (3) using other encoding methods without explicit angle representation to describe labels, such as in PSC [66], ACM [67], and EPE [68]. Among these, the second and third categories have shown better performance in alleviating boundary discontinuity problems.

Based on these solutions, we will use the PSC angle encoding method in the angle prediction part of SAR ship targets and combine it with existing joint optimization methods to introduce high-quality pseudo-labels into the model training process. This will achieve joint constraints on target angles and scales and alleviate the boundary discontinuity problem in OBB prediction.

2.3. OBB Detection Based on HBB Weak Supervision

Current weakly supervised OBB detection methods using HBB annotations are broadly categorized into self-supervised weak supervision (SSWS) and pseudo-label-based weak supervision (PLWS). SSWS approaches, such as H2RBox, H2RBox-v2, AFWS [69], and EIE-Det, leverage image transformations to construct self-supervised tasks for orientation estimation, while employing weakly supervised losses derived from HBB-OBB mappings to regulate object scale. Although computationally efficient, these single-stage methods often provide insufficient supervision for orientation and scale, limiting their detection accuracy. In contrast, PLWS methods—including WSODet [70] and the approach by Yue et al.—first coarsely learn scale under HBB supervision, and then generate OBB pseudo-labels via traditional or deep learning techniques to refine both orientation and scale. While Yue et al. demonstrated that traditional pseudo-label strategies can achieve strong performance in SAR ship detection, most PLWS methods rely heavily on two-stage detectors, leading to inefficient inference, parameter redundancy, and strong dependence on pseudo-label quality for orientation learning.

Based on the above current situation, we propose the integration of pseudo-label-based supervision into SSWS methods to enhance performance while maintaining efficiency. We will also optimize pseudo-label generation and selection strategies based on the characteristics of SAR ship targets, such as their point distribution and aspect ratios, to obtain high-quality pseudo-labels and improve detection performance.

3. Proposed Methods

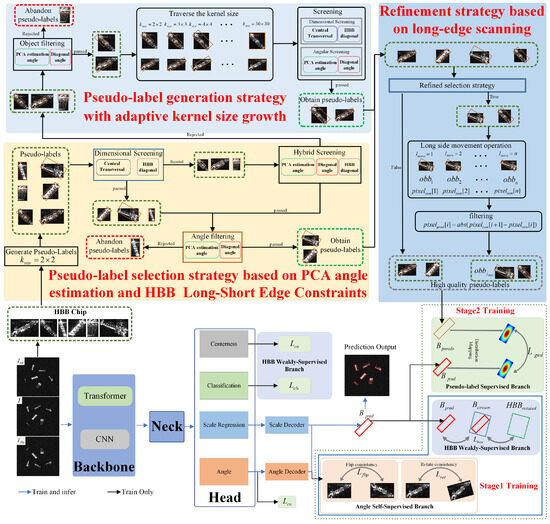

This section introduces the proposed method shown in Figure 1. The method employs the two-stage training method to incorporate pseudo-labels into the training of a single-stage detection model, reducing computational consumption and missed-detection rate while improving detection accuracy. The first stage uses the angle self-supervised branch and the HBB weakly supervised branch for coarse learning of target angles and scales. The second stage adds the pseudo-label supervised branch to refine these aspects by comparing high-quality pseudo-labels with predicted OBBs. In the second stage, pseudo-labels are obtained from HBB chips using PCA-HBB-PLSS and AKG-PLGS, and then refined using LES-RS to provide high-quality pseudo-labels for fine-grained training.

Figure 1.

The overall architecture of our method. the morphological closing kernel size. , , , and denote the pseudo-label, predicted OBB, rotated HBB, and OBB circumscribed rectangle. and are the loss functions for Centerness and Classification. is angle encoding loss. is weak-supervised scale loss. and are the loss functions for the self-supervised branch, and is pseudo-label loss.

During model inference, the backbone and neck networks first extract image features, followed by the generation of predictions by the head network. The Classification and Centerness determine target locations, while the Angle combined with the Angle Decoder provides the OBB angle information. The Scale Regression combined with the Scale Decoder provides the OBB’s length and width information. By integrating the prediction results of the above-mentioned components, OBB detection of targets can be achieved.

3.1. Pseudo-Label Generation and Selection Strategies

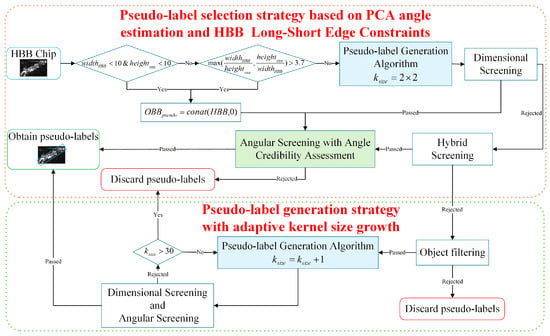

Yue et al. generated OBB pseudo-labels from HBB chips using OTSU [71] and morphological closing, but their strict and singular selection strategy limited the quantity and quality of pseudo-labels. To address these limitations, we propose two strategies: PCA-HBB-PLSS, which selects high-quality pseudo-labels using PCA angle estimation and HBB constraints; and AKG-PLGS, which increases pseudo-label quantity by assigning appropriate kernel sizes for SAR ship targets. As illustrated in Figure 2, HBB chips are processed sequentially through these two modules. The pseudo-label generation algorithm shown in Algorithm 1 takes the HBB chip and kernel size as inputs. It first extracts the hole-free target mask and contour , and then calculates the minimum bounding rectangle to generate pseudo-labels . The following sections first introduce the PCA angle estimation method, which is used in hybrid screening, angular screening with credibility assessment, object filtering, and angular screening. Then, the AKG-PLGS and PCA-HBB-PLSS strategies are detailed.

| Algorithm 1 Pseudo-label Generation Algorithm |

Input:

|

Figure 2.

Flowchart of pseudo-label generation and selection strategies.

3.1.1. PCA Angle Estimation

The imaging mechanism of SAR inherently results in SAR targets predominantly comprising scattering points with significant amplitude values. For SAR ships, the direction of maximum variance in scattering point distribution approximates the ship’s orientation. PCA can identify this direction by projecting data to maximize variance along the first principal component. Therefore, we implement the angle estimation of SAR ships using Algorithm 2. In steps 1 and 2, the algorithm constructs a two-dimensional scatter dataset containing the target’s mask by mean segmentation, where each sample represents the coordinates of a pixel. Steps 3, 4, and 5 utilize PCA to obtain the vector representation of the target’s orientation. Finally, in steps 6 and 7, is converted into an angle estimate , and the result is returned.

| Algorithm 2 PCA-Based Angle Estimation Algorithm |

Input:

|

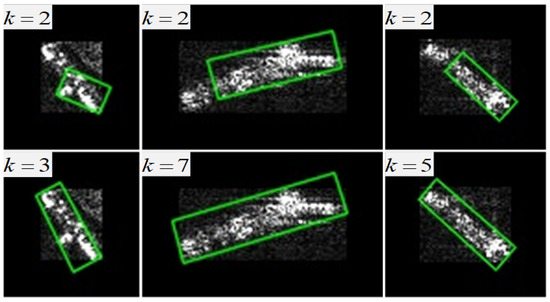

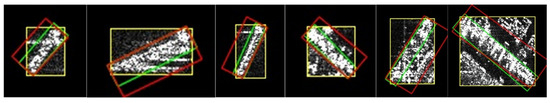

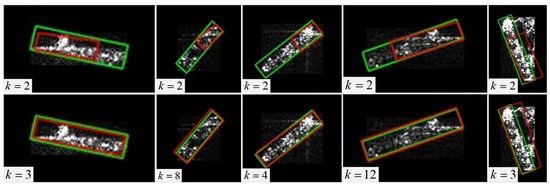

3.1.2. AKG-PLGS

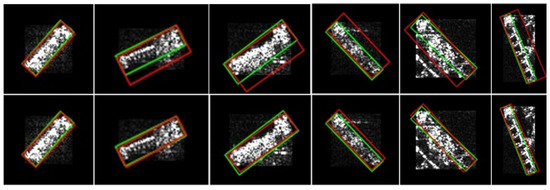

When using Algorithm 1 to generate high-quality pseudo-labels for SAR ship targets, the required varies greatly, as shown in Figure 3. Columns 2 and 3 indicate that increasing the kernel size can improve pseudo-label quality when the angle difference is small but length and width errors are large. Based on this, we propose the Adaptive Kernel Growth-based Pseudo-Label Generation Strategy (AKG-PLGS). It first identifies target chips needing kernel size adjustment through object filtering, and then iteratively selects the optimal kernel size and corresponding pseudo-labels. The selected pseudo-labels must pass both angular and dimensional screening. A larger maximum kernel size enables AKG-PLGS to generate appropriate kernels for targets of various sizes, though at the cost of increased computational time. Conversely, a smaller maximum kernel size improves computational efficiency but is only suitable for a limited range of target sizes. To balance efficiency and pseudo-label coverage, the maximum kernel size in AKG-PLGS is empirically set to 30.

Figure 3.

Pseudo-label generation results under different kernel sizes. k represents the kernel size. The green rectangles are the generated pseudo-labels.

The object filtering judges whether to adjust the kernel size by comparing the difference between the pseudo-label angle and the chip diagonal angle . To address large angle deviations caused by uneven scattering in SAR ship targets (e.g., Figure 3, column 1), we compare with the estimated target angle and relax the threshold using angle estimation error to increase pseudo-label generation. Considering the opposite angles of the HBB diagonals, we determine the result by comparing the minimum absolute difference among , , , and with the threshold. An excessively large angular threshold degrades pseudo-label quality, whereas an overly small one drastically reduces their quantity. To strike a balance between quality and quantity, we empirically set the threshold between and to and that between and to through iterative manual tuning and validation. The is obtained by Algorithm 2, and the is calculated as

where w and h are the width and height of the horizontal bounding box.

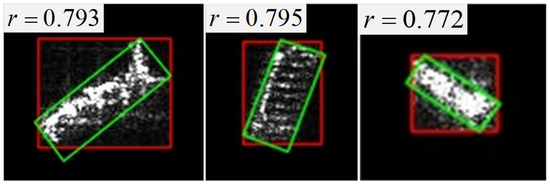

HBB chips rejected by the object filtering are discarded without generating pseudo-labels. AKG-PLGS assigns a suitable kernel size for chips passing the object filtering through iterative search. The search increases kernel size until the generated pseudo-label passes both dimensional and angular screening, at which point the current kernel size is deemed optimal. If the kernel size reaches its upper limit without meeting the criteria, the chip is discarded. Angular screening adopts the same procedure as object filtering but applies stricter criteria, with both angular thresholds and set to . Figure 2 shows this process. Yue et al. restricted the ratio of the OBB’s long side to the HBB’s diagonal for dimensional screening, often rejecting high-quality pseudo-labels for wide-head-and-tail ships (Figure 4). To address this, we introduce a method that assesses the ratio of the pseudo-label’s long side to a central cut-line parallel to the estimated target angle. This method relaxes the dimensional screening threshold while minimizing the impact on angle accuracy. Figure 5 shows schematic diagrams of HBB central cut-lines and their length calculations under different predicted angles. Algorithm 3 provides the detailed process for dimensional screening, where returning True indicates that the dimensional screening criteria are satisfied.

| Algorithm 3 Dimensional Screening Algorithm |

Input:

|

Figure 4.

Pseudo-label generation for wide-head-and-tail ships. The red rectangles are HBB labels, the green rectangles are pseudo-labels, and r is the ratio of the long side of the pseudo-label to the diagonal of the HBB.

Figure 5.

Schematic of HBB central cut-line and length calculation. The black rectangle is the HBB label of the ship, point O is the HBB center, and w and h are the lengths of the long and short sides of HBB, respectively. is the central cut-line. and are the lengths of the and . is the estimation angle of the ship.

3.1.3. PCA-HBB-PLSS

PCA-HBB-PLSS employs dimensional screening, angular screening with angle credibility assessment, and hybrid screening to obtain high-quality pseudo-labels. The dimensional screening is the same as in Algorithm 3. The angular screening with angle credibility assessment enhances the angular screening in PCA-HBB-PLSS by introducing a credibility evaluation mechanism for the PCA angle estimate to mitigate the impact of large errors in for some targets on the quality of the pseudo-labels. Specifically, is considered valid if its difference from the angles of the HBB’s two diagonals is below a specified threshold ; otherwise, it is invalid. When is valid, the output logic is the same as in the angular screening method in the AKG-PLGS. When is invalid, the decision is made by comparing the minimum absolute difference between and the HBB’s diagonal angles with the threshold . A larger threshold admits more pseudo-labels but degrades their angular accuracy; a smaller one yields higher angular precision at the cost of reduced quantity. To balance quality and quantity, we empirically set and to and the discrepancy threshold between and to through manual tuning and validation.

Hybrid screening employs a strategy of moderately relaxing the dimensional error threshold and tightening the angular error constraint to precisely select high-quality pseudo-labels with small angular errors and reasonable dimensional errors. This approach helps to mitigate the problem of high-quality pseudo-labels with only one desirable attribute (angle or scale) being mistakenly filtered out when angular and dimensional screenings are conducted independently. This method includes both dimensional and angular screening, with the angular screening being the same as in AKG-PLGS but with more restrictive thresholds () in the decision logic, and the dimensional screening being identical to in Algorithm 3.

Furthermore, given that the HBB and OBB of extremely small targets are indistinguishable and that the HBB of targets with a large aspect ratio can already provide sufficient localization accuracy, PCA-HBB-PLSS directly assigns a 0-degree angle to the HBB as the pseudo-label for these two types of targets. The retention of these pseudo-labels is subsequently determined through the angular screening.

Figure 2 illustrates the workflow of PCA-HBB-PLSS. The process begins by filtering HBB chips with extreme aspect ratios or minimal dimensions. Initial pseudo-labels undergo dimensional screening and angle credibility-aware angular screening. Chips rejected during angular screening are considered unsuitable for generating high-quality pseudo-labels. Those failing the dimensional screening proceed to a hybrid screening stage for re-evaluation. Chips that do not meet the hybrid screening criteria are forwarded to AKG-PLGS for subsequent processing, whereas those satisfying the criteria proceed to angular screening for final pseudo-label determination.

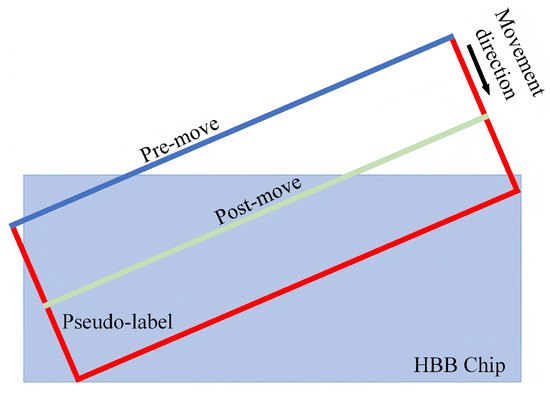

3.2. Refinement Strategy Based on Long-Edge Scanning

In complex nearshore scenarios, defocused SAR ship targets and background interference often introduce numerous extraneous strong scattering points in HBB chips, resulting in pseudo-labels generated by Algorithm 1 exhibiting longer long and short edges than the actual target dimensions. Since existing screening methods primarily focus on the long-edge length without constraining the short edge, the pseudo-labels obtained by PCA-HBB-PLSS and AKG-PLGS often have a short-edge length that exceeds the true value, as shown in Figure 6. Given that the proposed generation and selection strategies yield pseudo-labels with angles closely aligned to the true target orientations, we propose the Long-Edge Short-Edge Rescaling Strategy (LES-RS), which adaptively adjusts the short-edge length by shifting the long edge along the short-edge direction to enhance pseudo-label quality. The strategy comprises two components: the Long-edge Scanning Operation (LESO), which refines the short-edge length of pseudo-labels, and the Refined Selection Strategy (RSS), which selects high-quality pseudo-labels for LESO based on the ratio between the long-edge segment length in the HBB chip and the long-edge length of the pseudo-label.

Figure 6.

Pseudo-labels generated under defocused and complex background conditions. The green rectangle represents the OBB label, the red rectangle is the generated pseudo-label, and the yellow rectangle is the HBB chip boundary.

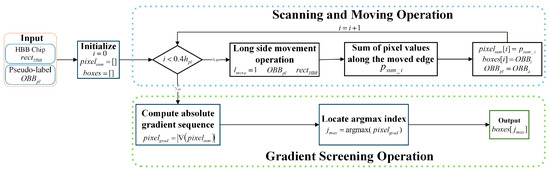

The LESO includes the Scanning and Moving Operation (SMO) and the Gradient Screening Operation (GSO). The SMO iterates the long edge of a pseudo-label within a preset offset distance, generating a candidate box list and a corresponding sequence of edge pixel sums. In the SMO, the Long-Side Movement Operation translates the long edge with the shorter segment length inside the HBB chip along the short-edge direction while keeping the opposite long edge fixed, as illustrated in Figure 7. To optimize the short-edge length, the GSO selects the optimal pseudo-label based on the maximum absolute gradient of the pixel sums covered by the moved edges. Figure 8 illustrates the LESO workflow: the input pseudo-label and HBB chip are processed by the SMO to produce a candidate pseudo-label list and a pixel sum sequence , where denotes the pseudo-label’s short-edge length. The GSO then identifies the refined pseudo-label using the maximum gradient index . The calculation of is as follows:

where and are the i-th elements of and , respectively, and denotes the absolute value function.

Figure 7.

Schematic of the Long-Side Movement Operation.

Figure 8.

Flowchart of Long-edge Scanning Operation.

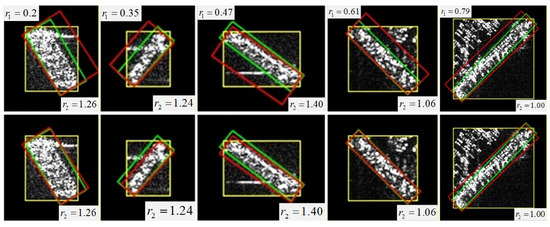

Figure 9 shows the pseudo-label visualization results before and after the LESO. It reveals that pseudo-labels of SAR ship targets affected by defocusing often have one long edge with a small effective length proportion in the HBB chip. When the chip’s aspect ratio is close to 1, some targets still need the LESO to improve pseudo-label quality. Therefore, the RSS calculates the minimum ratio of the segment length of the two long edges within the chip to the long-edge length and compares it with a threshold to determine whether to refine the pseudo-labels. For chips with an aspect ratio close to 1, the threshold for can be increased to optimize selection performance. Specifically, LESO is needed when . When , the threshold for can be relaxed to 0.88 to prevent mis-screening. Otherwise, the LESO is not required.

Figure 9.

Comparison of pseudo-label results before and after LESO. The green rectangle is the OBB label, the red rectangle is the pseudo-label, and the yellow rectangle is the HBB label. is the ratio of the smaller segment length of the pseudo-label’s long sides within the HBB label to the pseudo-label’s long side. is the ratio of the HBB’s long side to its short side. The 1st and 2nd rows show the pseudo-label visualization results before and after the LESO.

3.3. Structural Improvements

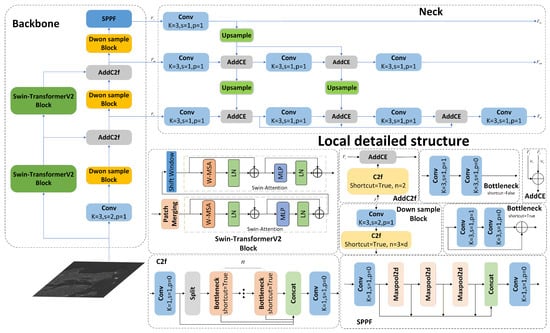

To enhance detection performance and computational efficiency, we improved the backbone and neck structures of Yue et al.’s method. We integrated Swin-TransformerV2 with a few convolutional layers in a parallel structure, reducing the model’s parameter scale and improving its computational efficiency and global information acquisition capability. We also used a top-down adaptive feature fusion method to enhance the semantic information of high-resolution features, improving the neck structure’s feature fusion capability and boosting detection performance. The backbone and neck structures of our method are illustrated in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Backbone and neck structure.

3.3.1. Parallel Backbone Based on Swin-TransformerV2 and CNN

We combine CNN and Vision Transformer via a parallel structure, allowing the backbone to capture both local details and global semantics. To achieve model lightweighting, we restrict each branch of the parallel backbone to only a handful of primitive blocks and perform branch fusion through a compact, low-parameter feature re-weighting operator. The CNN branch uses the rich gradient-flow c2f structure from YOLOv8 to boost convergence speed and quality. The Transformer branch employs Swin-TransformerV2 with window attention and cyclic shifts for efficient global information capture. We use hierarchical fusion to stabilize training and weighted summation with learnable parameters and for adaptive feature fusion, as shown in the AddCE module in Figure 10. The formula is as follows:

where , , and are the features from Swin-TransformerV2, CNN, and their fusion, respectively. and are the learnable weights for CNN and Swin-TransformerV2 features; their values are updated in an end-to-end manner via back-propagation, guided by the gradients of the overall training loss with respect to the entire set of network parameters.

Figure 10 shows the backbone network structure we used, which integrates Swin-TransformerV2 with a few YOLOv8 backbone layers, reducing the model’s parameter scale and enhancing its computational efficiency and global information acquisition capability. The output , , and are feature maps of different resolutions. The convolutional branch includes Conv, Down sample block, Addc2f, and SPPF modules. The Conv uses a convolutional layer and SiLU activation. The c2f combines multiple convolutions and residual connections, with concatenated outputs passed through a Conv module to accelerate convergence. The Down sample block reduces feature size with a convolutional layer (kernel size 2, stride 2) and a c2f module. The Addc2f aligns feature dimensions and performs adaptive fusion. SPPF fuses features from different receptive fields to provide local and global information.

The Transformer branch consists of two Swin-TransformerV2 blocks. As depicted in Figure 10, Layer Normalization (LN) is placed after each residual unit to stabilize activation outputs and training. Patch Merging resizes the input feature map using scale flattening and maps each pixel to a common feature space via a linear layer. W-MSA performs multi-head attention within windows, using scaled cosine attention to mitigate the impact of strong background scatterers in complex scenes. The attention formula is

where is the query vector of the j-th pixel, and is the key vector of the i-th pixel. is a learnable scaling parameter (), and is a bias term determined by a meta-learning network G based on logarithmic relative position coordinates. The specific calculation formulas are

where and are the relative position coordinates and their logarithmic representations between the j-th and i-th pixels in the window, respectively. is the sign function. The network G consists of two linear layers and a ReLU activation function, taking the logarithmic representation of relative position coordinates as input to reduce the range of input values and enhance multiscale target detection. Shift Window denotes the cyclic shift operation of the window, enabling interaction between pixels of different windows to improve global information perception. MLP represents the multilayer perceptron.

3.3.2. Unidirectional Semantic Pyramid

We designed a Unidirectional Semantic Pyramid (USP) that employs a top-down pathway for hierarchically integrating multiscale features. This architecture enhances the semantic richness of high-resolution features through a data-adaptive weighting mechanism, thereby improving the robustness of the neck network.

Figure 10 illustrates the USP structure, comprising three top-down paths, lateral connections, and residual connections. The first path uses a 3 × 3 convolution to match channel numbers of multiscale features from the backbone, and then performs resolution matching and feature fusion using interpolation and weighted summation. The second path processes features similarly but uses 3 × 3 convolution to suppress aliasing during lateral feature transfer. The third path combines multiscale features from the first two paths through weighted summation for semantic enhancement. , , and are backbone features; , , and are USP outputs. All features undergo a 3 × 3 convolution before output to reduce aliasing effects from upsampling.

3.4. Two-Stage Training Method

In practical applications, targets with complex characteristics are challenging to annotate with high-quality pseudo-labels, which significantly increases the risk of the model missing detections when trained solely on pseudo-labels. Yue et al. mitigated this issue by employing a two-stage detection model with a coarse-to-fine training strategy based on its two prediction results. Inspired by this, we divide our model’s training process into two stages: the first stage employs HBB weak supervision and angle self-supervision to initially learn the target scale and angle, and the second stage refines this learning with pseudo-label supervision. Specifically, the training is split into two stages: the first 6 epochs apply angle self-supervision and HBB weak supervision for coarse angle and scale learning; later epochs introduce OBB pseudo-labels to refine them. This method integrates pseudo-labels into the training of the single-stage detection model, reducing the parameter scale while enhancing the detection performance and computational efficiency.

The model’s training process is shown in Figure 1. The input image I is first subjected to random rotation and flip transformations to obtain and . These transformed images then pass through the backbone, neck, and head to obtain corresponding outputs and calculate the respective losses. In the first stage of model training, the state space of the predicted angle encoding is first constrained by the unit circle constraint loss . The calculation formula for is as follows:

where represents the i-th element of the encoding vector, and n is the encoding length. The angle encoding and decoding methods are described in Section 3.5. Next, the angle self-supervised branch calculates the self-supervised loss to achieve coarse learning of the target angle. The specific calculation formulas are as follows:

where is a hyperparameter, and and represent the self-supervised losses for flip and rotation transformations, respectively. , , and are the predicted angles for the original image, flipped image, and randomly rotated image, respectively. is the value of the random rotation angle, and is the Snap Loss. Simultaneously, the HBB weakly-supervised branch calculates the weakly-supervised loss to achieve coarse learning of the target position and scale. The calculation formula for is as follows:

where , , and represent the Focal Loss for classification, the Cross-Entropy loss for centerness, and the CircumIoU loss [25], respectively. and are hyperparameters. and constrain the target position, while constrains the target scale. Based on the above, the overall loss for the first stage is as follows:

In the second stage of model training, we first generate high-quality pseudo-labels from HBB chips using our proposed strategies. We then calculate via the pseudo-label supervised branch to refine the model’s learning of target scale and angle using GWD loss [63]. first maps each predicted rotated bounding box and its corresponding ground-truth box into a 2D Gaussian distribution, whose parameters (mean and covariance) are analytically derived from the box’s center coordinates , width , height , and rotation angle . The is then defined as the Wasserstein distance between the two distributions. This distance metric is differentiable and inherently eliminates the boundary discontinuity problem that typically plagues angle-based regression in rotated object detection. The exact formulation is given by

where and represent the covariance matrix and the mean vector of the corresponding 2D Gaussian distribution for the rotated bounding box, respectively. denotes the squared L2 norm, and stands for the trace of a matrix. To mitigate the impact of missing pseudo-labels for some targets on model performance, the second stage retains the loss from the first stage. The total loss for the second stage is

where is a hyperparameter.

To generate high-quality pseudo-labels, we first employ PCA-HBB-PLSS for angle and scale screening of HBB chips. Subsequently, the rejected chips are processed by AKG-PLGS, which performs object filtering and adaptive kernel size assignment. Finally, the outputs from both strategies are refined by LES-RS through long-edge scanning and gradient-based selection to produce the final pseudo-labels for the pseudo-label supervised branch.

Furthermore, in the first stage of training, we assign positive and negative samples based on feature scale and HBB labels. An anchor point is assigned as a positive sample if its corresponding pixel in the original image is within the target’s HBB label and the box size falls within the feature map’s prediction range; otherwise, it is a negative sample. In the second stage, we use the positive samples from the target’s HBB label as positive samples for high-quality pseudo-labels, constraining the scale and angle of prediction OBB.

3.5. Others

This section will introduce other details in Figure 1, including the head structure, angle encoding and decoding methods, and scale decoding methods.

Our head network is based on the FCOS head structure with an added angle prediction branch. The Angle in Figure 1 predicts the pcs encoding vector of the angle to mitigate discontinuity in OBB prediction. The encoding and decoding formulas are

where is the target angle, is the i-th element of the encoding vector, and N is the encoding length with a value of 3.

The scale regression head predicts distances from the anchor point to the left, top, right, and bottom boundaries of the detection box, indirectly predicting the scale (w, h) and center coordinates of the OBB. The formulas are

where are the anchor point coordinates in the original image, and s is the scaling ratio of the feature map resolution relative to the original image resolution.

The centerness predicts the anchor point’s proximity to the target center to suppress low-quality detections. A prediction value closer to 1 indicates a closer feature location to the target center.

4. Results

In this section, we evaluate the detection performance of the proposed method through experiments. We first introduce the datasets and experimental settings, and then describe the evaluation criteria. Subsequently, we conduct comparative experiments on the HRSID and SSDD datasets, contrasting our method with mainstream weakly supervised and fully supervised rotation detection methods to validate its effectiveness.

4.1. Datasets and Settings

Our method aims to train the OBB detector using HBB labels to enhance detection performance and inference efficiency. To validate the effectiveness of our method, the experimental datasets need to contain both OBB and HBB annotations. Accordingly, we select the HRSID and SSDD datasets for our experiments. Both HRSID and SSDD are high-resolution SAR image datasets specifically designed for ship detection, semantic segmentation, and instance segmentation tasks. The HRSID dataset comprises 5604 images of size 800 × 800, with 16,951 ship instances annotated, covering various resolutions, polarization modes, sea conditions, and maritime scenes. The SSDD dataset contains 1160 images with pixel lengths ranging from 500 to 600, annotating 2456 ship targets, encompassing diverse sea conditions, ship types, and sizes. In our experiments, the HRSID dataset is split into a 65% training set and a 35% testing set, while the SSDD dataset follows a 7:3 split ratio. Throughout the experiments, the input image size is uniformly set to 800 × 800. The partitioning of the training and testing sets strictly follows the protocols established in the mainstream literature, ensuring that the reported detection metrics can be compared in a direct and quantitative manner.

All experiments were conducted on two NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPUs using the MMRotate and Ultralytics detection frameworks. For the MMRotate implementation, we employed the AdamW optimizer with an initial learning rate of , with and , trained for 72 epochs with a batch size of 4. The loss weights for the first-stage loss were set to , , and . For the second-stage loss , the term was weighted by . Under the Ultralytics framework, training was performed using the SGD optimizer with an initial learning rate of and a momentum of , for 200 epochs with a batch size of 32.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

The detection performance of OBB detection models is commonly assessed using precision, recall, and mAP50. The precision and recall are calculated as follows:

where TP, FP, and FN represent true positives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively. Precision indicates the proportion of accurate detections among all predictions, while recall measures the proportion of detected targets relative to the total number of targets. These metrics are influenced by the confidence and IoU thresholds. The mAP50, which fixes the IoU threshold at 0.5, is calculated by integrating the precision–recall curve:

where r is the recall and is the precision at different recall levels. The range of mAP50 is 0 to 1, with higher values indicating better detection performance. To eliminate the impact of the confidence threshold, we use mAP50 to evaluate detection performance.

In practical inference, the parameter scale and computational consumption are crucial for cost estimation. Therefore, we focus on the number of parameters and the floating-point operations (GFLOPS) required to process a single image to quantitatively measure the model’s inference cost.

4.3. Experimental Results

To validate the effectiveness of our method, we compared its performance with mainstream weakly supervised methods and fully supervised methods on the HRSID and SSDD datasets. The weakly supervised methods included H2Rbox, H2Rbox-v2, and the Unit Circle Resolver (UCR) [72]. Among them, UCR, as the state-of-the-art weakly supervised detector that reports superior performance, is adopted as the baseline under weak supervision in our comparative experiments. The fully supervised single-stage detection methods based on convolutional structures are YOLOv8, RetinaNet, S2ANet, FOCS, and RTMDet. YOLOv12, a fully supervised single-stage detection method based on attention mechanisms, is also included. The fully supervised two-stage detection methods are Faster-RCNN, Oriented-RCNN, R3Det, ReDet, and ROI-Transformer. The training and testing results of YOLOv8 and YOLOv12 are computed under the Ultralytics framework, whereas those of all other models are obtained within the MMRotate framework. To ensure that numerical discrepancies faithfully reflect inter-model performance differences, all detection performance metrics are uniformly calculated based on the MMRotate framework.

Table 1 shows the detection performance of different methods in the offshore and inshore scenes, and the entire test set of the HRSID. The last two columns indicate the number of model parameters and the computational cost required to infer an 800 × 800 image. The table demonstrates that our method achieves the best detection performance among all compared weakly supervised methods, with the smallest computational and parameter requirements. Compared to the second-best weakly supervised method, our method improves mAP50 by 13.178% in the entire test set of HRSID, 18.357% in inshore scenes, and 7.416% in offshore scenes. It also reduces computational cost by about 30% and parameter scale by about 90%. The performance boost in inshore scenes is attributed to the parallel integration of Swin-TransformerV2 into the CNN, enhancing the model’s interference resistance by providing both global semantics and local details. The improvement in offshore scenes is relatively modest, likely due to the loss of high-quality pseudo-labels for some targets during filtering, reducing the model’s attention to this part of the targets and increasing the miss rate. The compared weakly supervised methods (H2Rbox, H2Rbox-v2, UCR) all use FCOS with a ResNet50 backbone, accounting for 73.188% of parameters and 41.692% of computations. Our method uses a small number of c2f and Swin-TransformerV2 structures in the backbone, achieving lightweighting while maintaining performance. Thus, our approach effectively enhances detection performance and efficiency in SAR ship detection tasks while reducing model size.

Table 1.

Comparison of experimental results on HRSID.

Additionally, Table 1 shows that our method outperforms most fully supervised methods in entire and inshore scenes, only surpassing RetinaNet and Faster-RCNN in offshore scenes. In terms of parameter scale, our method is comparable to the smallest fully supervised method. Our method, an improvement over H2Rbox-v2, uses FCOS as its fully supervised counterpart. Compared to FCOS, our method improves mAP50 by 1.602% in entire scenes and by 5.506% in inshore scenes, but it decreases by 1.803% in offshore scenes. The performance gains are attributed to improvements in the backbone and neck structures and the use of high-quality pseudo-labels during training. However, the lack of high-quality pseudo-labels for some targets leads to insufficient model focus on these targets during training, resulting in a performance drop in offshore scenes. Compared to single-stage detectors YOLOv12 and YOLOv8, our method has higher computational costs during inference, with the head and neck parts accounting for 71.049% and 23.857% of computations, respectively. This is due to the FCOS model’s shared detection head structure, which requires high-dimensional features for multiscale target detection. YOLOv12 and YOLOv8 use multiple detection heads, reducing computational complexity and better utilizing fully supervised label information. Therefore, compared to YOLOv12 and YOLOv8 under full supervision, our method has gaps in both detection performance and inference efficiency.

Table 2 shows the detection performance of different methods in various scenes of the SSDD dataset, with column meanings consistent with Table 1. Our method achieves the best detection performance among all compared weakly supervised methods, improving mAP50 by 3.059% in the entire test set of the SSDD, 6.006% in the inshore scene, and 1.288% in the offshore scene compared to the second-best weakly supervised method. This indicates that our method can enhance the detection performance of weakly supervised models in SAR ship detection tasks, even in small-data-scale scenarios. In addition, the model configurations used in this table are the same as those in the HRSID experiments. The optimization of the model parameter scale and inference computing resources also remains unchanged, and details will not be repeated here.

Table 2.

Comparison of experimental results on SSDD.

As shown in Table 2, our method surpasses only R-RetinaNet across all scenarios (entire, inshore, and offshore), a result that contrasts markedly with the findings in Table 1. This discrepancy is primarily attributed to the limited scale of the SSDD dataset. Our approach integrates self-supervised learning via random rotation and flipping, weakly supervised learning based on HBBs, and pseudo-label-guided learning for angle and scale estimation. The constrained dataset size restricts the acquisition of sufficient multi-angle samples and high-quality pseudo-labels, thereby impairing the model’s capacity to learn discriminative orientation and scale features. Furthermore, the inherent orientation sensitivity of SAR targets diminishes the efficacy of self-supervised augmentation. The limited training samples also increase overfitting risks, while the small test set may fail to reveal such overfitting, contributing to the apparently superior performance of fully supervised models in evaluation metrics.

To verify that the limited scale of the SSDD dataset is the main reason for the lower detection performance under weakly supervised conditions, we mix different proportions of the HRSID training set with the SSDD training set for model training, and evaluate the detection performance on the SSDD test set. The experiment uses SwinV2-CNN as the backbone, USP as the neck structure, and TTM as the training method. Detailed results are shown in Table 3, where an HRSID ratio of 0 indicates using only the SSDD training set, and bold values represent the best results in each column. As shown in Table 3, when the HRSID mixing ratio reaches 30% and 70%, the model’s detection performance improves, indicating that expanding the scale of SSDD helps enhance detection effectiveness and further confirming that dataset size is a critical factor limiting model performance. In addition, comparisons between Table 2 and Table 3 reveal that although incorporating HRSID training data improves performance to a level comparable with most fully supervised methods, a gap remains with the optimal fully supervised approach. This gap is mainly due to distribution differences between the two datasets: SSDD contains multi-polarization and multi-resolution data, while HRSID is single-polarization and single-resolution. Thus, partially integrating HRSID data is insufficient to fully augment the SSDD dataset, thereby limiting further improvements in model performance.

Table 3.

Performance on SSDD with varied training ratios assisted by HRSID.

As shown in Table 1 and Table 2, on HRSID, the mAP50 gap between our method and the best fully supervised approach is 3.659% for inshore and 1.947% for offshore scenes; on SSDD, the corresponding gaps are 19.266% and 6.027%. The detection performance of our method in offshore scenarios is close to that of fully supervised methods. This strong performance in offshore scenarios is attributed to the two-stage training strategy we adopted, which reduces the dependency on rotated bounding box annotations through angle self-supervised learning and HBB weak supervision, while enhancing detection performance via pseudo-label-guided training. Furthermore, since generating pseudo-labels is inherently easier in offshore scenarios than in inshore ones, the guidance provided by pseudo-labels in our method is more effective in offshore settings, thereby resulting in detection performance that is closer to fully supervised methods in such scenarios.

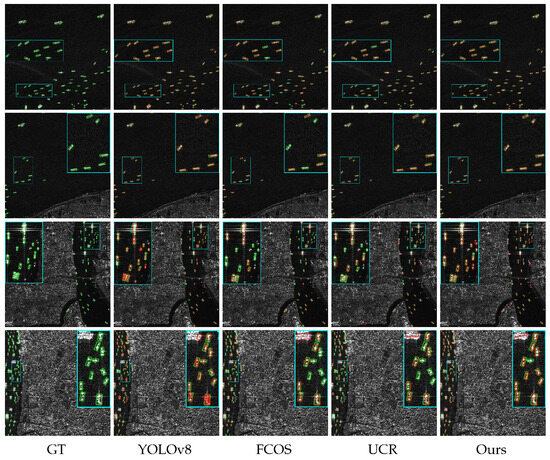

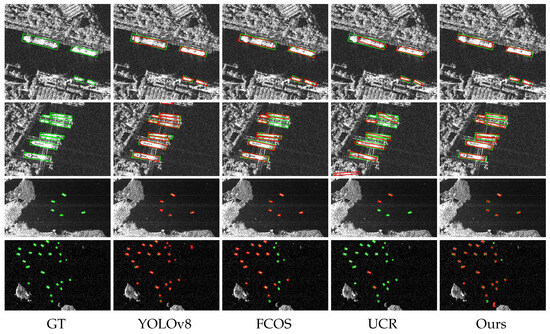

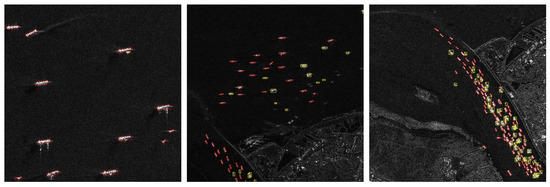

To more intuitively illustrate the performance of our method, Figure 11 and Figure 12 present the detection results of four different methods on the various scenarios of the HRSID and SSDD. FCOS and YOLOv8, as strong fully supervised detectors, provide the structural basis for our approach, with our backbone design inspired by YOLOv8. UCR, a weakly supervised approach, shares the first-stage training loss with our method and thus serves as our direct baseline. As shown in Figure 11, our method achieves a lower miss rate in nearshore and offshore scenes with small, dense ships, matching the precision and false alarm rates of fully supervised detectors while outperforming UCR. In Figure 12, rows 2 and 4 indicate that our method performs only slightly worse than fully supervised YOLOv8 in detecting dense large targets inshore and very small dense targets offshore. Rows 1 and 3 further show that our precision for inshore targets of varying sizes is comparable to YOLOv8 and superior to the other methods. These results confirm that our approach attains detection performance competitive with fully supervised methods.

Figure 11.

Visualization results of four representative methods in typical and complex scenarios of the HRSID. The green rectangle is the OBB label, and the red rectangle is the model detection result. The blue rectangle indicates the locally magnified area.

Figure 12.

Visualization results of four representative methods in typical and complex scenarios of the SSDD. The green rectangle is the OBB label, and the red rectangle is the model detection result.

5. Discussion

This section presents a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed method. We first visualize pseudo-labels to demonstrate the effects of three key strategies: AKG-PLGS, PCA-HBB-PLSS, and LES-RS. Subsequently, systematic ablation studies are conducted to validate the individual contributions of these strategies. Finally, component-wise ablation experiments assess the effectiveness of the proposed backbone, neck network, and pseudo-label supervision method. All experiments are performed on the HRSID dataset to ensure statistical reliability and mitigate potential biases from limited data size.

5.1. Visualization of Three Pseudo-Label Generation Strategies

To identify high-quality OBB pseudo-labels that closely align with ground-truth annotations, we propose the PCA-HBB-PLSS. As illustrated in Figure 13a, the screening strategy effectively filters out pseudo-labels with substantial angle and scale deviations. Figure 13b demonstrates that most selected pseudo-labels align accurately with ground-truth rotated boxes, with only a small number retaining notable errors in short-side length—these residual inaccuracies are subsequently mitigated by the LES-RS module.

Figure 13.

Visualization of pseudo-labels obtained and discarded by PCA-HBB-PLSS. The green rectangles are OBB labels, and the red rectangles are pseudo-labels. (a) Discarded pseudo-labels; (b) obtained pseudo-labels.

Furthermore, to enhance the quantity of high-quality pseudo-labels, we propose the AKG-PLGS. Figure 14 contrasts the OBB pseudo-labels generated by AKG-PLGS with those from a fixed-kernel-size method (Algorithm 1). The first row depicts the pseudo-labels generated by the fixed-kernel-size method, while the second row illustrates the results from AKG-PLGS. Figure 14 indicates that AKG-PLGS can assign appropriate morphological closing operation kernel sizes for different targets, thereby increasing the number of high-quality pseudo-labels. Most generated pseudo-labels closely match the ground-truth labels, although a few targets still exhibit significant short-side length errors.

Figure 14.

Comparison of pseudo-label results generated by fixed-kernel-size method and AKG-PLGS. The green rectangles are OBB labels, and the red rectangles are pseudo-labels. k represents the kernel size used for pseudo-label generation.

To address the significant short-side length errors in some pseudo-labels obtained by the aforementioned strategies, we propose the LES-RS to enhance pseudo-label quality. Figure 15 compares pseudo-labels before and after LES-RS. Rows 1 and 2 show results before and after processing. Column 1 indicates that LES-RS avoids affecting high-quality pseudo-labels. Columns 2 to 5 show that LES-RS reduces short-side lengths, mitigating errors from AKG-PLGS and PCA-HBB-PLSS. The visualization results in columns 4 and 5 show that the short sides of the pseudo-labels obtained by LES-RS exhibit minor differences compared to the true labels’ short sides. The primary causes of this discrepancy are strong background interference and a limited range of movement distance during the scanning process. Strong background interference introduces certain errors in the pseudo-label angles input to LES-RS. These errors significantly impact the pixel scanning and calculations of the scanning edges during the Long-edge Scanning Operation, thereby affecting the final position determination. Although a shorter-distance movement can reduce the occurrence of short-edge length issues during refinement, some targets, influenced by complex backgrounds, require a movement distance greater than the maximum range set during the refinement process. Despite the minor errors in some target results, overall (columns 2 to 5), our method effectively alleviates the problem of significant short-edge length errors in pseudo-labels, which are caused by the selection and generation strategies.

Figure 15.

Visualization of pseudo-labels before and after processing by the LES-RS. The green rectangles are OBB labels, and the red rectangles are pseudo-labels.

Applying AKG-PLGS, PCA-HBB-PLSS, and LES-RS to the HRSID training set yields high-quality pseudo-labels for 68% of targets. Figure 16 shows the visualization of pseudo-labels obtained in different scenarios. Figure 16 indicates that our method performs well in generating pseudo-labels for offshore and sparsely distributed nearshore targets, but shows limitations with densely arranged nearshore targets, particularly small targets and those in complex backgrounds. The fixed angular threshold in our filtering process tends to incorrectly reject high-quality pseudo-labels for small targets, while the mask-based generation approach lacks robustness in complex nearshore environments. Future work will explore dynamic angular thresholds based on target size to improve small-target recall, and more robust mask generation methods to enhance pseudo-label quality in challenging scenarios.

Figure 16.

Visualization of high-quality pseudo-labels obtained by three proposed strategies in different scenarios. The green rectangles are OBB labels, and the red rectangles are pseudo-labels. The red rectangles represent high-quality pseudo-labels, and the yellow rectangles denote HBB labels of targets. Targets enclosed by yellow rectangles cannot obtain corresponding high-quality pseudo-labels through our method.

5.2. Ablation Experiments

To quantitatively validate the effectiveness of different strategic modules in the pseudo-label generation method, we conducted the corresponding ablation experiments. The bold font indicates the best result in each column. During the experiments, the model employed SwinV2-CNN as the backbone structure and USP as the neck structure. The training procedure adopted our proposed two-stage training method. The specific experimental results are presented in Table 4, where Experiment 7 represents the scenario without pseudo-labels under an identical model architecture. Since the two-stage training method requires pseudo-labels as supervisory signals, the ablation experiments do not include cases utilizing LES-RS alone.

Table 4.

Ablation experiments for pseudo-label generation strategies on HRSID.

As shown in Table 4, the comparison between Experiment 7 and other experimental groups demonstrates that our proposed pseudo-label generation method effectively guides the model in learning object scales and orientations to improve detection performance, regardless of whether individual modules or combined modules are employed. The comparison between Experiments 5 and 6 indicates that the pseudo-labels generated by AKG-PLGS yield greater performance improvement in nearshore scenarios compared to PCA-HBB-PLSS, while slightly underperforming the latter in offshore scenarios, suggesting that AKG-PLGS is more suitable for nearshore pseudo-label generation whereas PCA-HBB-PLSS performs better for offshore targets. Experiment 3 achieves a 1.365% higher mAP50 in nearshore scenarios than Experiment 6, and Experiment 2 outperforms Experiment 5 by 0.67%, confirming that LES-RS enhances pseudo-label quality for nearshore targets and consequently improves detection performance. Since AKG-PLGS is more appropriate for nearshore pseudo-label generation and LES-RS significantly improves nearshore pseudo-label quality, the combination of AKG-PLGS and LES-RS should outperform the combination of PCA-HBB-PLSS and LES-RS, as validated by Experiments 2 and 3. Experiment 1 achieves the best detection performance in this ablation study, further verifying the effectiveness of jointly utilizing the three proposed pseudo-label generation optimization methods.

To verify the effectiveness of the backbone structure, neck structure, and two-stage training method in our approach, we conducted ablation studies. Table 5 presents the experimental results. The bold font indicates the best result in each column. SwinV2-CNN and USP denote the backbone and neck structures of our method, respectively, while TTM represents the two-stage training method. Experiment 8 is the baseline method UCR, which employs ResNet50 as the backbone and FPN as the neck structure. Experiment 1 corresponds to our proposed method, featuring SwinV2-CNN as the backbone and USP as the neck structure, and utilizing the two-stage training method.

Table 5.

Ablation experiments for model structure and training method on HRSID.

In Table 5, Experiments 5, 6, 7, and 8 demonstrate that the backbone structure, neck structure, and two-stage training method in our approach effectively enhance the detection performance of UCR. Among these, the SwinV2-CNN backbone structure contributes the most to performance improvement while also significantly reducing the model’s parameter scale and computational cost. Experiments 2–4 and 8 reveal that the proposed backbone and neck structures alone, under angle self-supervision and horizontal box weak supervision, fail to reach their full potential. However, when either of these structures is combined with the two-stage training method, a substantial boost in detection performance is observed. This highlights the effectiveness of the two-stage training method in leveraging high-quality pseudo-labels to fully realize the detection capabilities of our backbone and neck structures. Experiments 1–3 demonstrate that the integration of the two-stage training method with the enhanced backbone and neck architectures achieves the strongest detection performance across the entire HRSID test set, with an mAP50 of 82.50%. Comparisons between Experiments 1 and 3 reveal that the UCR structure enhances detection performance but increases the model’s parameter scale and computational load. Meanwhile, Experiments 1 and 2 show that the SwinV2-CNN backbone structure not only boosts performance but also reduces the model’s parameter count and computational cost.

As indicated by the aforementioned analysis, the backbone structure, neck structure, and two-stage training method in our approach effectively enhance the model’s detection performance. The SwinV2-CNN backbone achieves performance improvement while simultaneously reducing model parameters and computational complexity. The two-stage training method, when combined with either the SwinV2-CNN backbone or the UCR structure, significantly improves the model’s detection performance. The combined effect of all three components achieves the optimal detection performance across all scenarios in the HRSID dataset.

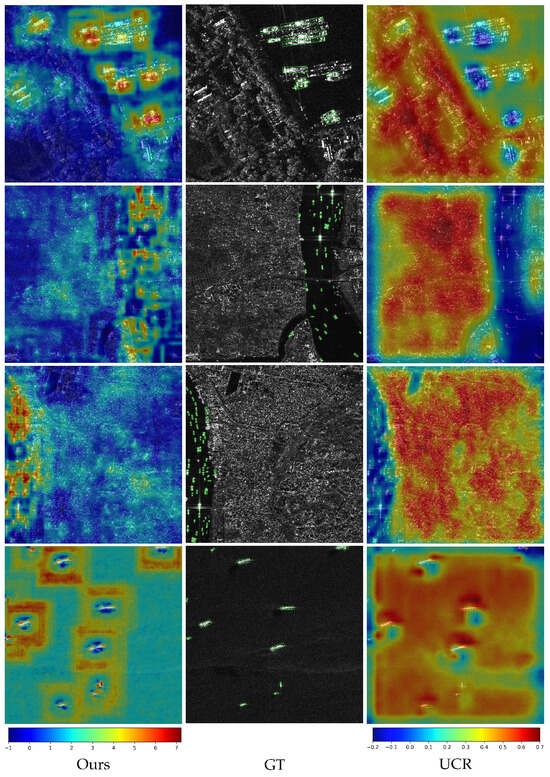

Figure 17 compares the neck network output features of UCR and our model using Grad-CAM. Our model employs a SwinV2 backbone with a USP neck for feature extraction, whereas the UCR features are extracted by a ResNet-50 backbone and an FPN neck, which represents a mainstream architecture for weakly supervised methods. Blue areas indicate less impact on the model’s output, while red areas indicate more impact. This visualization reflects the model’s focus when making detection decisions. As evidenced in the figures, our approach generates detection results across various scenes primarily through concentrated attention on target regions. This characteristic not only well explains the performance improvement of our method but also substantiates the effectiveness of the designed backbone and neck architecture for the detection task.

Figure 17.

Feature visualization results of UCR and our method. The bottom row of the figure displays the color-bar legends for the heat-maps produced by different methods. The green box represents the OBB label of the target. The left color bar corresponds to our approach, with a value range of to , while the right color bar denotes the UCR method, covering to .

6. Conclusions

To address the limitations of current weakly supervised OBB detection methods for SAR ships, including insufficient and low-quality pseudo-label generation, inefficient inference, large model size, and limited global information acquisition, we propose a weakly supervised SAR ship oriented-detection algorithm based on pseudo-label generation optimization and guidance. Our approach introduces a two-stage training strategy that progressively refines detection performance through high-quality pseudo-label supervision. The first stage employs HBB weak supervision for coarse learning, while the second stage leverages our proposed AKG-PLGS, PCA-HBB-PLSS, and LES-RS modules to generate refined pseudo-labels for fine-grained learning. Additionally, we design a compact architecture integrating Swin-TransformerV2 with YOLOv8 layers, reducing model size while enhancing global feature capture. An adaptively fused neck structure further strengthens multiscale feature integration. Experiments on HRSID and SSDD datasets demonstrate that our method substantially improves detection performance with lower model complexity and inference costs, underscoring the critical role of high-quality pseudo-labels in advancing weakly supervised oriented detection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.G., X.H., J.S. and A.H.; Investigation, F.G., X.H., J.W. and J.S.; Methodology, C.F.; Resources, X.H. and J.W.; Software, C.F.; Supervision, J.W., J.S. and A.H.; Validation, C.F.; Visualization, C.F.; Writing—original draft, C.F.; Writing—review and editing, F.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 62371022.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ma, F.; Sun, X.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, Y.; Li, H.C. What catch your attention in SAR images: Saliency detection based on soft-superpixel lacunarity cue. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 61, 5200817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, R.; Xu, H.; Gao, F.; Tang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Hussain, A. Improving DOA estimation of GNSS interference through sparse non-uniform array reconfiguration. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2025, 38, 103384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Gao, F.; He, X.; Wang, J.; Sun, J.; Zhou, H.; Hussain, A. Few-shot class-incremental SAR target recognition via orthogonal distributed features. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2025, 61, 325–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Sun, X.; Ma, F.; Yin, Q. Superpixelwise likelihood ratio test statistic for PolSAR data and its application to built-up area extraction. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 209, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Li, M.; Wang, J.; Sun, J.; Hussain, A.; Zhou, H. General Sparse Adversarial Attack Method for SAR Images based on Key Points. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2025, 61, 14943–14960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Kong, L.; Lang, R.; Sun, J.; Wang, J.; Hussain, A.; Zhou, H. SAR target incremental recognition based on features with strong separability. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5202813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, C.; Devillers, R.; Mouillot, D.; Seguin, R.; Catry, T. Ship Detection with SAR C-Band Satellite Images: A Systematic Review. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 14353–14367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, T.; Zhang, T.; Shao, Z.; Xu, X.; Zhang, W.; Shi, J.; Wei, S.; Zhang, X. CFAR-DP-FW: A CFAR-guided dual-polarization fusion framework for large-scene SAR ship detection. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 7242–7259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Liu, M.; Zhang, M.; Qi, S.; Yang, J. Ship detection based on a superpixel-level CFAR detector for SAR imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2022, 43, 3412–3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, J. PolSAR ship detection based on superpixel-level contrast enhancement. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 4008805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.; Liu, P.; Wang, L. Rotation sliding window of the hog feature in remote sensing images for ship detection. In Proceedings of the 2015 8th International Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Design (ISCID), Hangzhou, China, 12–13 December 2015; Volume 1, pp. 401–404. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Ning, F.; Xi, Y.; Liang, G.; He, Z.; Zhang, Y. MSFA-YOLO: A Multi-Scale SAR Ship Detection Algorithm Based on Fused Attention. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 24554–24568. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, C.; Liu, D.; Xue, F.; Lv, Z.; Wu, X. Faster and Lighter: A Novel Ship Detector for SAR Images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 4002005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Bai, L.; Zhang, Y.; Momi, M.C.; Quan, S.; Ye, Z. ELLK-Net: An Efficient Lightweight Large Kernel Network for SAR Ship Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5221514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, W.; Fang, S. TPNet: A High-Performance and Lightweight Detector for Ship Detection in SAR Imagery. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, M.; Niu, B.; Zhang, J. SAR image generation method for oriented ship detection via generative adversarial networks. Signal Image Video Process. 2024, 18, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Lang, P.; Yin, J.; He, Y.; Yang, J. Data matters: Rethinking the data distribution in semi-supervised oriented sar ship detection. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, R.; Jiang, F. AMR-Net: Arbitrary-Oriented Ship Detection Using Attention Module, Multi-Scale Feature Fusion and Rotation Pseudo-Label. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 68208–68222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Huang, H.; Wang, J.; Sun, J.; Hussain, A.; Zhou, H. A comprehensive framework for out-of-distribution detection and open-set recognition in SAR targets. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 16095–16109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Gao, F.; Sun, J.; Wang, J.; Hussain, A.; Zhou, H. Novel category discovery without forgetting for automatic target recognition. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 4408–4420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Xu, Y.; Liu, P. A weak supervision learning paradigm for oriented ship detection in SAR image. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5207812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, F.; Gao, F.; Liu, T.; Wang, J.; Sun, J.; Zhou, H. Scattering characteristics guided network for isar space target component segmentation. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2025, 22, 4009505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Chen, K.; Shi, Z.; Guo, Y.; Ye, J. Object detection in 20 years: A survey. Proc. IEEE 2023, 111, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, G.; Li, W.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yan, J. H2rbox: Horizontal box annotation is all you need for oriented object detection. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.06742. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Da, F.; Yan, J. H2RBox-v2: Incorporating symmetry for boosting horizontal box supervised oriented object detection. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 59137–59150. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Zhan, Y.; Lin, X.; Yu, B.; Ding, L.; Zhu, J.; Tao, D. Explicit and implicit box equivariance learning for weakly-supervised rotated object detection. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 2024, 9, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, S.; Song, S.; Qin, R.; Tang, Y. Remote sensing object detection in the deep learning era—A review. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Dong, Y.; Shen, L.; Liu, Y.; Pei, Y.; Yang, H.; Zheng, L.; Ma, J. Development and challenges of object detection: A survey. Neurocomputing 2024, 598, 128102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, A.; Vairavasundaram, S. Yolo-based object detection models: A review and its applications. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 83535–83574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Zhang, J.; Xia, Y.; Xiao, H. DBW-YOLO: A high-precision SAR ship detection method for complex environments. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 7029–7039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Leng, X.; Luo, R.; Sun, Z.; Ji, K.; Kuang, G. YOLO-RC: SAR ship detection guided by characteristics of range-compressed domain. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 18834–18851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Shin, Y. An efficient YOLO for ship detection in SAR images via channel shuffled reparameterized convolution blocks and dynamic head. ICT Express 2024, 10, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Xie, E.; Li, X.; Fan, D.P.; Song, K.; Liang, D.; Lu, T.; Luo, P.; Shao, L. Pyramid vision transformer: A versatile backbone for dense prediction without convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 568–578. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, X.; Tian, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Ren, H.; Wei, X.; Xia, H.; Shen, C. Twins: Revisiting the design of spatial attention in vision transformers. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 9355–9366. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Dai, X.; Yang, J.; Xiao, B.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, L.; Gao, J. Multi-scale vision longformer: A new vision transformer for high-resolution image encoding. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 2998–3008. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Z.; Wang, P.; Li, Y.; Ding, B. A new deep neural network based on SwinT-FRM-ShipNet for SAR ship detection in complex near-shore and offshore environments. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]