Highlights

What are the main findings?

- An integrated framework combining RAC-Unet deep learning and XGBoost-SHAP explainable AI was successfully developed, achieving high-precision identification of 34,376 shallow landslides and accurate prediction of their runout distance (R2 = 0.923).

- The SHAP analysis systematically revealed the nonlinear mechanisms and threshold effects of key controlling factors, identifying source area (SA) as the primary factor with a significant scaling effect, followed by the source length/width ratio (SLWR) and source slope (SS).

What are the implication of the main findings?

- The study provides a transformative solution to the “data bottleneck” in land-slide hazard analysis by enabling the automated construction of large-scale, standardized landslide inventories, which is crucial for training robust data-driven models.

- A simplified predictive model requiring only three easily obtainable parameters (SA, SLWR, SS) was constructed (R2 = 0.862), bridging the gap between complex algorithms and practical application for rapid pre-disaster risk assessment and post-disaster emergency response.

Abstract

This study addresses the challenge of predicting runout distance of rainfall-induced shallow landslides by integrating deep learning and explainable machine learning. Using the June 2024 landslide disaster at the Fujian-Guangdong-Jiangxi border as a case study and remote sensing images as the data source, we developed an improved U-Shaped Convolutional Neural Network model (RAC-Unet) combining Deep Residual Structure, Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling, and Convolutional Block Attention Module modules. The model identified 34,376 shallow landslides and built a dynamic parameter database with 8875 samples, which was used for data-driven model training. After comparing models, Extreme Gradient Boosting was chosen as the best (R2 = 0.923), with its performance confirmed by Wilcoxon analysis and good generalization in external validation (R2 = 0.877). SHapley Additive Explanations analysis revealed how factors like the area of the sliding source zone (SA), length/width ratio of the sliding source zone (SLWR), and average slope of the source zone (SS) affect landslide runout, a simplified model using the three parameters SA, SLWR, and SS was constructed (R2 = 0.862). Compared to traditional models, this integrated framework solves the pre-disaster impact range estimation problem, deepens understanding of shallow landslide dynamics, and enables accurate pre- and post-disaster predictions. It provides comprehensive support for disaster risk assessment and emergency response in southeastern hilly areas.

1. Introduction

With the intensification of global climate warming, the frequency and intensity of extreme rainfall events have continued to rise, posing an increasingly severe threat to hilly and mountainous areas. Heavy rainfall can cause rapid saturation of surface soil, significantly weakening its shear strength, thereby triggering regional shallow landslides that are widely distributed and highly sudden [1]. Such disasters often have significant cascading effects, not only causing long-term negative impacts on the ecological environment but also seriously endangering the safety of people’s lives and property, as well as the sustainable socio-economic development of regions [2,3]. In the coastal areas of southeastern China, the terrain is primarily mountainous and hilly. Residual soil layers formed by the weathering of bedrocks such as granite are widely distributed, and under the influence of the high-temperature, high-humidity subtropical monsoon climate, these areas have become one of the high-incidence regions for rainfall-induced shallow landslides globally. The shallow landslides in this region are primarily soil landslides. Historical records show that typical disaster events have occurred in places such as Wuping, Fujian [4], Zixing, Hunan [5,6,7], and Shaoguan, Guangdong [8]. Of particular concern is that in June 2024, the border area of Fujian, Guangdong, and Jiangxi provinces experienced a historically unprecedented extreme rainfall event, which triggered a large-scale outbreak of shallow landslides. This disaster event is one of the larger-scale outbreaks of shallow landslides in China in recent decades, resulting in heavy casualties and direct economic losses amounting to 15.7878 billion RMB [9]. Against this background, the development of accurate and efficient methods for landslide hazard risk assessment and early warning has become particularly urgent.

Machine learning models have been widely applied in landslide susceptibility prediction, by analyzing historical landslide data and environmental factors such as slope, precipitation, and soil type, machine learning can identify potential landslide risk areas [10,11,12]. Common machine learning algorithms include Random Forest, Extreme Gradient Boosting, and K-Nearest Neighbors, which are capable of handling complex nonlinear relationships and generating landslide susceptibility maps. Accurate identification of potential landslide areas is the foundation for the precise prediction of landslide runout distance. In the risk assessment chain of landslide disasters, the runout distance is one of the key parameters that determine the impact range and the extent of damage. Accurately predicting the landslide runout distance can not only be used for quickly delineating the disaster boundary after the event, optimization of rescue routes, and engineering repair layout, but also serves as the core scientific issue and decision-making basis for pre-disaster risk prediction, quantifying the risk of disaster-bearing bodies, and transitioning disaster management from “passive response” to “active prevention and control.” Currently, the models used for landslide runout distance assessment are mainly divided into three types: empirical statistical models, physically driven models, and machine learning models. Empirical statistical models establish simple relationships based on historical data [13,14], which, although convenient, are strongly limited by regional constraints and lack a physical mechanism explanation [15]. Physically driven models, based on mechanical principles and the law of energy conservation, can provide a mechanistic explanation of the runout process [16,17,18], but they require a large number of parameters and complex calculations, making them difficult to apply for rapid assessment of large-scale, heterogeneous group landslides. Machine learning models, capable of capturing complex nonlinear relationships between multiple factors, have demonstrated tremendous potential in terms of prediction accuracy and generalization ability [19,20,21], offering new pathways to overcome the limitations of traditional models.

However, a fundamental challenge to successfully applying machine learning models to regional group shallow landslide runout distance assessment is the need for a sufficiently large and accurately labeled landslide sample database with geometric and kinematic characteristics. The quantity and quality of the samples directly determine the performance ceiling and reliability of data-driven models [22]. Traditional manual field surveys and visual interpretation methods are inefficient, costly, and highly subjective when dealing with widely distributed, large-scale group landslides, making it difficult to systematically construct large-scale, standardized sample datasets [23]. This data bottleneck severely restricts the development and application of high-performance machine learning models for shallow landslide runout distance estimation.

In recent years, the combination of deep learning technology and high-resolution remote sensing imagery has provided a revolutionary solution to overcome the aforementioned sample bottleneck. In particular, semantic segmentation models (such as U-Net [24] and its variants) are capable of automatically identifying and extracting landslide boundaries at the pixel level, thereby quickly and in bulk obtaining key geometric parameters such as the spatial location and planar shape of landslides [25,26]. This enables us to efficiently construct a standardized sample database covering the entire disaster area, containing tens of thousands of landslides, thus laying a solid data foundation for training complex machine learning models that require large amounts of data.

Although deep learning has solved the problems of “sample quantity” and “acquisition efficiency,” machine learning models applied to runout distance prediction still face the “black box” dilemma [27]. Their decision-making process lacks transparency and is unable to provide physical mechanism explanations, which reduces the credibility of the results in disaster prevention and mitigation practices. The emergence of explainable machine learning methods (such as SHAP [28]) provides tools to address this issue. It can quantify the contribution of each feature and reveal its nonlinear mechanisms while maintaining high model performance. This has been preliminarily applied in fields such as landslide susceptibility assessment [8,29]. However, how to systematically integrate the sample automatic generation capability of deep learning with the mechanistic analysis capability of explainable machine learning, and construct a complete framework from “sample recognition” to “distance assessment” to “mechanistic explanation,” remains a frontier direction to explore in current research on rainfall-induced shallow landslide runout distance.

Therefore, this study takes the group of shallow landslides triggered by extreme rainfall in the border area of Fujian, Guangdong, and Jiangxi provinces in June 2024 as a case study, aiming to construct an integrated research framework that deeply combines deep learning and explainable machine learning. Specifically, this study first uses an improved RAC-Unet deep learning model to achieve precise and rapid automatic identification of shallow landslides in the study area, and selects unobstructed samples to construct a standardized database of landslide dynamic parameters. Then, the study trains and optimizes the best machine learning model to build a rainfall-triggered shallow landslide runout distance assessment model. Furthermore, the SHAP tool is introduced to deeply analyze the mechanisms and threshold effects of key influencing factors, such as area of the sliding source zone (SA), length/width ratio of the sliding source zone (SLWR), average slope of the source zone (SS), and height difference in the source zone (SH). Finally, a simplified prediction model is developed based on physically meaningful factors. The results of this study will provide an innovative methodology and efficient technical tools for regional geological disaster risk assessment, covering the processes from “recognition” to “evaluation” and “understanding.”

2. Materials

2.1. Study Area

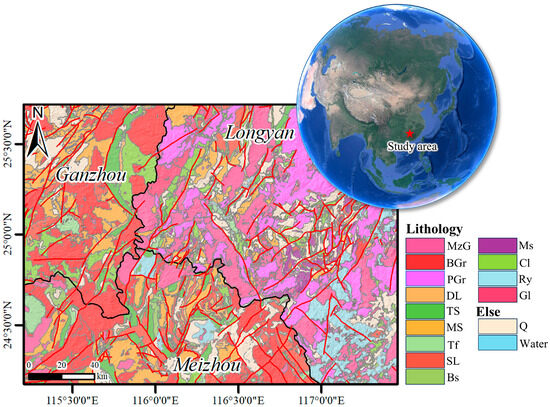

The study area is located at the junction of Jiangxi, Fujian, and Guangdong provinces in southeastern China, with the latitude and longitude range from 115°20′E to 117°25′E, and from 24°20′N to 25°40′N. The geological structure of this area is complex, with the main lithologies being granite, metasandstone, among others (Figure 1). These bedrocks have undergone long-term weathering, resulting in the widespread distribution of residual soil layers. These residual soils have loose structures and well-developed pores, making them highly susceptible to saturation under heavy rainfall conditions, which leads to a sharp decline in shear strength and constitutes an important material basis for landslide disasters [9].

Figure 1.

Study area overview: geographical location at the junction of Jiangxi, Fujian, and Guangdong provinces, lithological map based on data from the Geological Cloud Platform of the China Geological Survey (https://geocloudsso.cgs.gov.cn (accessed on 3 November 2025)). The key lithological units include the following: MzG, monzonitic granite; PGr, potassic granite; BGr, biotite granite; Tf, tuff; Ry, rhyolite; Bs, basalt; MS, metasandstone; Gl, granulite; Ms, mudstone; SL, siliceous limestone; DL, dolomitic limestone; Cl, conglomerate; TS, tuffaceous sandstone; In addition to the core lithology distribution, it also covers the elements of the Quaternary strata, the water system, and the geological structures (faults) indicated by the red lines.

The region has a typical subtropical monsoon climate, significantly controlled by the marine southeastern monsoon, with an average annual precipitation ranging from 1400 to 1700 mm. The rainfall distribution throughout the year is highly uneven, with the rainy season from April to September accounting for more than 70% of the annual precipitation. From April to June, continuous frontal rainfall is dominant, while from July to September, heavy convective rainfall mainly caused by typhoons prevails. This unique climate-geological combination makes the area a high-incidence zone for shallow landslides. Over the past five years, multiple typical rainfall-induced group landslide events have occurred [8,30,31].

2.2. The June 2024 Landslide Event

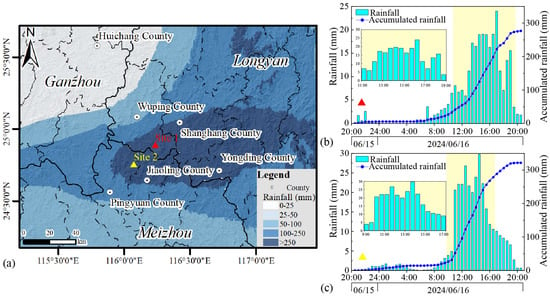

On 16 June 2024, the study area experienced a historically rare extreme rainfall event. According to the global precipitation monitoring dataset (https://gpm.nasa.gov/data (accessed on 3 November 2025)) a rainfall distribution map was created (Figure 2), with the rainfall center concentrated in the mountainous areas of Wuping County in Fujian Province and Jiaoling County in Guangdong Province. The heavy rainfall mainly occurred between 11:00 a.m. and 7:00 p.m. local time, with a total accumulated rainfall exceeding 250 mm. The real-time 24 h rainfall situation in the local areas is shown as Site1 and Site2. This rainfall event exhibited significant spatiotemporal concentration, and its formation mechanism is closely related to the uplift effect caused by the complex terrain: when the warm, moist air mass from the South China Sea is forced to rise due to the mountain topography, the water vapor rapidly cools and condenses, resulting in extreme rainfall on the windward slopes in front of the mountains. This extreme rainfall triggered a large-scale clustered shallow landslide disaster event, causing significant casualties and economic losses. It also provided a valuable natural laboratory for studying the development patterns and runout characteristics of group shallow landslides under extreme rainfall conditions.

Figure 2.

Precipitation in the study area: data from the Global Satellite Mapping of Precipitation (GSMaP) dataset: (a) spatial distribution of cumulative precipitation; (b,c) cumulative precipitation for the locations marked in (a).

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data Sources

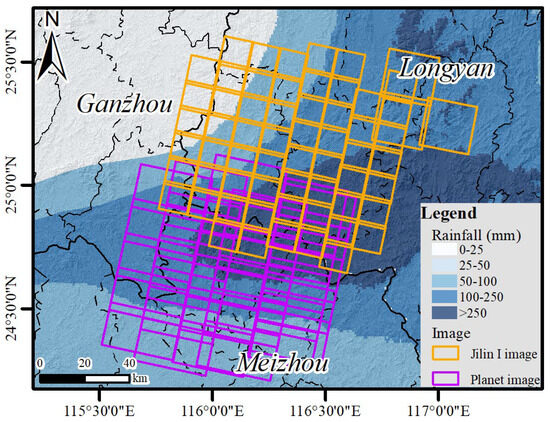

This study adopts a multi-source data collaborative analysis strategy. The data involved mainly includes optical remote sensing imagery for landslide identification, geological environment data, topographic data, and rainfall data that triggered the disaster event. The basic data for landslide identification comes from high-resolution optical satellite imagery. As shown in Figure 3, these specifically include: (1) Jilin-1 satellite data with a spatial resolution of 0.5 m, a total of 62 scenes, and an imaging date of 5 August 2024 (UTC + 8), ensuring that landslide scars are clearly distinguishable; (2) PlanetScope satellite data from Planet Labs, with a spatial resolution of 3 m, a total of 32 scenes, and imaging dates from 4 to 5 August 2024 (UTC + 8). These images together form the initial data source for landslide intelligent interpretation and sample database construction.

Figure 3.

Spatial distribution of remote sensing image scenes used for landslide identification over the study area.

The choice of August 2024 as the observation period is to align with the optical satellite imagery acquisition requirements after the disaster. After the disaster, optical satellite imagery is needed for hazard identification and disaster assessment. However, the region experienced persistent cloud cover in July, and the high reflectivity of the clouds caused the imagery to be heavily obscured by cloud patches and shadows, making the surface textures unclear and unsuitable for precise interpretation, creating a monitoring gap. In contrast, the cloud system in August was intermittently distributed, allowing optical satellites to capture clear surface information, effectively filling the imagery data gap caused by clouds in July and providing valuable support for post-disaster remote sensing analysis.

Geological environment data is used to describe the background conditions for landslide development. The lithology data comes from the 1:200,000 digital geological map published by the China Geological Survey’s Geological Cloud Platform (https://geocloud.cgs.gov.cn/ (accessed on 3 November 2025)). The soil thickness data is sourced from the National Earth System Science Data Center, providing centimeter-level spatial distribution information of surface soil thickness. The normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) is obtained by calculating the near-infrared and red light band reflectance from Sentinel-2 satellite imagery prior to the landslide event, and is used to characterize the vegetation cover conditions before the landslide occurred

Topography is a key factor controlling the initiation and runout of landslides. In this study, we use the 12.5 m resolution digital elevation model (DEM) provided by ALOS PALSAR as the base terrain data (https://www.eorc.jaxa.jp/ALOS/en/aw3d30/index.htm (accessed on 3 November 2025)). Based on this DEM, we use ArcGIS software (version 10.8) to derive a series of terrain factor data, including slope, aspect, terrain ruggedness index, and terrain moisture index. These derived factors together form a key parameter set that describes the terrain characteristics of the landslide runout path.

The rainfall data that triggered this disaster event were obtained from the GSMaP_Gauge product of the Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) mission (https://gpm.nasa.gov/data (accessed on 3 November 2025)). This dataset provides 30 min average rainfall intensity at a spatial resolution of 0.1° × 0.1° for the period from 00:00 on 15 June to 24:00 on 17 June 2024 (UTC + 8). We extracted the total accumulated rainfall of this extreme rainfall event as the triggering rainfall for each landslide location.

3.2. Methodology

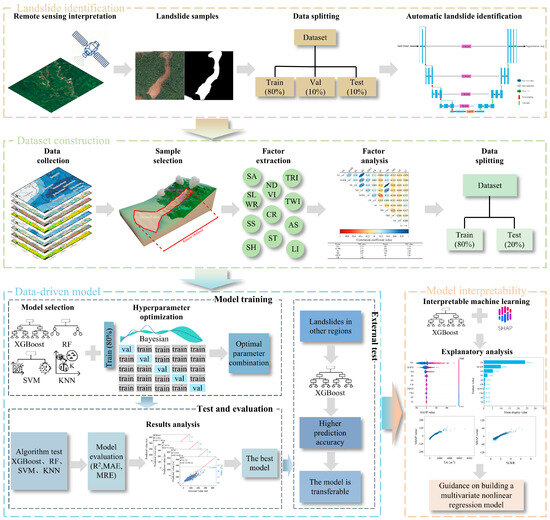

As shown in Figure 4, the core of the methodology in this study is a sequential technical framework that successively accomplishes landslide identification, sample construction, model development, and mechanistic interpretation. Finally, based on this core technical framework, a simplified prediction model is developed using physically meaningful factors. The details of this technical framework are described in this section.

Figure 4.

Flowchart illustrating the integrated research methodology, encompassing landslide identification, sample selection, machine learning modeling, and explainable AI analysis.

3.2.1. Landslide Identification Using the RAC-Unet Deep Learning Model

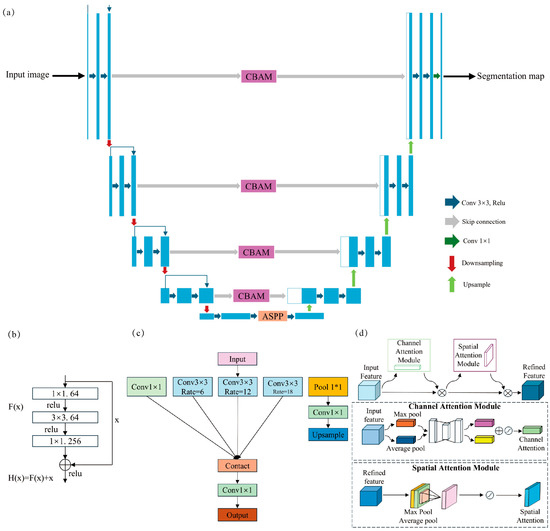

This study developed an improved deep learning semantic segmentation model, RAC-Unet (Figure 5a), for the accurate and rapid interpretation of large-scale group-occurring shallow landslides. This model is based on the classic U-Net architecture [32] and integrates multiple advanced modules to enhance its ability to extract and segment shallow landslide features under complex terrain backgrounds. The model uses ResNet50 [33] as the encoder, replacing the simple convolutional layers in the original U-Net. The deep residual structure of ResNet effectively alleviates the gradient vanishing problem (Figure 5b), enhancing the model’s ability to deeply abstract complex landslide textures and morphological features. After the deepest encoder layer, an Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) module (Figure 5c) is introduced. The ASPP module captures multi-scale contextual information by applying dilated convolutions with different sampling rates [34], enabling the model to perceive both the overall contour and local details of landslides without losing resolution, effectively reducing misclassification and omission caused by differences in landslide scale and blurred boundaries. Furthermore, a Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) is embedded in the skip connections between the encoder and decoder. CBAM sequentially computes attention weights along the channel and spatial dimensions (Figure 5d), allowing the model to adaptively focus on key channels and spatial locations relevant to landslides during feature fusion, effectively suppressing background noise interference [35].

Figure 5.

Detailed Network Architecture of the Proposed Semantic Segmentation Model: (a) Overall Architecture of the RAC-Unet Model; (b) ResNet Module; (c) ASPP Module; (d) CBAM.

The model training was conducted in a hardware environment equipped with a 16 GB VRAM NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4080 GPU. The input image size was 256 × 256 pixels, with a batch size of 16. Binary Cross-Entropy (BCE) was used as the optimization objective function, and the Adam optimizer was employed for parameter iteration, with an initial learning rate of 0.0001. A weight decay of 0.0001 was set to control overfitting, and the model was trained for 200 epochs. A total of 1240 manually labeled samples were constructed through manual visual interpretation from two different optical remote sensing satellites. These samples were randomly divided into training, validation, and test sets in an 8:1:1 ratio. Data augmentation strategies, such as horizontal flipping and vertical flipping, were applied to expand the samples and enhance the model’s generalization ability. As a result, the model achieved high-precision, batch-based interpretation of 34,376 landslides across the entire study area. The model’s performance was evaluated using Precision, Recall, Mean Intersection over Union (MIou), and F1 score. The formulas for these metrics are as follows:

Among them, Precision focuses on measuring the proportion of actual positive samples in the samples predicted as positive by the model, Recall concerns the proportion of actual positive samples correctly predicted by the model, F1-Score comprehensively reflects the classification performance, and MIoU calculates the average intersection over union (IoU) between the predicted regions and the ground truth regions for all categories; TP, FN, FP, and TN represent the number of pixels correctly identified as landslides, the number of pixels that are actual landslides but predicted as non-landslides, the number of pixels that are actual non-landslides but misclassified as landslides, and the number of pixels correctly classified as non-landslides, where k + 1 is the number of classes.

3.2.2. Construction of a Standardized Landslide Runout Database

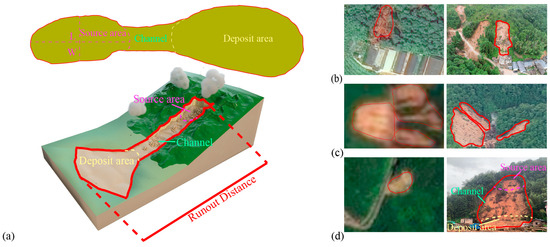

To ensure the learning effect and physical relevance of the subsequent runout distance model, we established strict sample selection criteria. As shown in Figure 6a, the core principle is to select landslide instances that move naturally and have no significant obstacles at the leading edge of their runout path, ensuring that their runout distance accurately reflects the effects of terrain and materials. As shown in Figure 6b, landslides whose runout front is blocked by artificial structures such as buildings and roads, thereby truncating their runout distance, are excluded, as they do not represent natural runout processes. Additionally, landslides occurring on both sides of a valley, where the runout path and deposition range are strongly constrained by the opposing topographical troughs, are considered non-natural runouts and are excluded (Figure 6c). Qualified samples, as shown in Figure 6d, are landslides that, after initiating from the source area, have an unobstructed runout path, without being blocked by valleys, buildings, or steep embankments, and the runout process naturally terminates.

Figure 6.

Criteria for selecting valid landslide samples: (a) Definition of Key Parameters for Landslides and Principles for Selection of Parameters; (b) example of a landslide obstructed by downslope buildings; (c) Examples of landslides constrained by opposing topographical troughs; (d) example of a landslide moving in a natural, unobstructed state.

Based on the results identified by the RAC-Unet model, the samples are selected according to the above principles, and for each selected sample, the landslide source area boundary was manually delineated with high-resolution imagery and DEM data on the ArcGIS platform. Based on this, the landslide morphological and dynamic parameters, including the source area, length/width ratio of the source area, slope of the source area, elevation difference in the source area, and landslide runout distance, were calculated.

In addition, a landslide event triggered by extreme rainfall occurred in Wuping County, Fujian Province, on 27 May 2022. This event is similar to the research case in terms of causation (rainfall trigger), type (shallow landslide), and geological background, but it occurred at a different time. We strictly followed the sample selection criteria described in this section, and from the 867 landslide results interpreted from reference [4], we ultimately selected 84 qualified landslide samples without pre-landslide barriers, forming an external test set for evaluating the model’s generalization performance.

3.2.3. Predictor Variable Selection

Considering the potential influence of source area morphology, topographic conditions, and external triggering factors on the runout distance of landslides, this study selected eleven influencing factors that have been used in previous research to evaluate landslide runout behavior, including SA, SLWR, SS, SH, Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), Cumulative rainfall (CR), Soil thickness (ST), Terrain Ruggedness Index (TRI), Topographic Wetness Index (TWI), Slope aspect (AS), Lithology (LI). The physical significance of each factor and its impact on runout distance have been supported by numerous studies. The detailed explanations, expected impacts, and related references for these factors are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of initial predictor variables used for predicting landslide runout distance, including their hypothesized influence and supporting references.

3.2.4. Correlation and Collinearity Analysis

This study diagnoses the correlation between variables using Spearman correlation analysis to preliminarily identify potential multicollinearity risks. As a non-parametric statistical method, Spearman correlation analysis does not rely on the assumption of normal distribution for the variables. The core of this method is to measure the monotonic association strength between variables by calculating the Spearman correlation coefficient (Equation (4)). Generally, when the correlation coefficient exceeds 0.8, it indicates a strong correlation between two variables, which may introduce collinearity interference in subsequent models [3].

In the relevant formula, rs denotes the Spearman correlation coefficient, which has a value range of [−1, 1]; n represents the sample size; and di stands for the rank difference in the i sample between the two variables (the rank of variable A minus the rank of variable B).

Based on Spearman correlation analysis, this study further uses the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) to quantify the severity of multicollinearity [45]. The essence of VIF is to measure the variance of a single variable, which is inflated due to collinearity with other variables. It is the core indicator for assessing the impact of multicollinearity. When the VIF value (Equation (5)) ≥ 10, it indicates that the multicollinearity between variables has reached a severe level and will significantly affect the stability of the model results. Based on these two diagnostic results, to build a concise and efficient data-driven model, redundant information must be removed from the initially selected 11 influencing factors.

In the relevant formula, VIFj represents the Variance Inflation Factor of the j independent variable, which measures the extent to which this variable is affected by collinearity with all other independent variables in the model; Rj denotes the coefficient of determination of the j independent variable with other variables.

3.2.5. Landslide Runout Displacement Prediction Model Development and Evaluation

Considering that landslide runout distance estimation is a regression task in supervised learning, this study selected four widely used machine learning algorithms for model comparison: Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN). XGBoost integrates multiple decision trees based on a gradient boosting framework to improve estimation accuracy. RF constructs multiple decision trees and aggregates their outputs to reduce the risk of overfitting. SVM uses a kernel function to map data to a high-dimensional space to find the optimal separating hyperplane. KNN performs regression estimation by selecting the nearest neighbor samples in the feature space based on Euclidean distance.

In the model training, the selected samples are divided into a training set and a testing set in an 8:2 ratio for model performance validation. To fully exploit the potential of each model, the Bayesian optimization algorithm was used to search for the optimal hyperparameter combination, with a total of 500 iterations and a step size of 1. During the training process, five-fold cross-validation was used to assess model performance in real-time to avoid overfitting: the training set was divided into five subsets, with one used as the validation set and the remaining four used for training. The average of the five validation results was taken as the robust estimate of model performance. The parameter selection ranges for each model are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The hyperparameter search space of the four machine learning models.

Model performance evaluation is divided into two levels: internal validation and external validation. Internal validation is conducted on the independent test set, using two metrics: Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Coefficient of Determination (R2), To avoid the limitation of evaluating model performance using a single indicator, Mean Relative Error (MRE) evaluation metric was also introduced to quantify the relative magnitude of the error, to comprehensively assess the model’s fitting accuracy for the training data:

In the formula, , and represent the observed value, the predicted value, and the mean of the observed values of the i sample, respectively. MAE reflects the average absolute deviation between the predicted and actual values, with smaller values indicating higher model accuracy. R2 is used to measure the model’s ability to explain the variability of the dependent variable, with values closer to 1 indicating a better fit. MRE reflects the average level of relative deviation between the predicted values and the actual values. The smaller the value, the higher the model’s prediction accuracy for data of different magnitudes.

To test the generalization performance of the model, we input the corresponding feature data of this external test set into the trained optimal model to directly calculate the predicted landslide runout distance. By calculating the R2 value, MAE value and MRE value between the predicted values and the actual observed values, we systematically evaluated the model’s estimation accuracy and robustness in a new environment.

For the multivariate nonlinear regression model, Sobol sensitivity analysis was performed on the landslide displacement and three variables: SA, SS, and SLWR. Through global variance decomposition, the total-order index Si (representing the total impact of the variables and their interactions) was calculated to quantify the contribution of the three variables to the uncertainty of the landslide displacement across the entire value range. The total-order index Si corresponds to the generalized Sobol total-effect index, and its calculation relies on the global variance decomposition logic of the Sobol method [46]. The specific formula for the generalized index provides the core mathematical support for this quantification process.

In the above formula, Si represents the generalized Sobol index for i ∈ {total, 1, 2}, Y = (Y1,…, Yp)T is the result vector from our simulations, where p is the number of simulated plots, Var(Yj) is the variance of the j plot, and is the Sobol index i of the j plot.

3.2.6. Significance Analysis

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test is a non-parametric statistical method used to assess whether there is a significant difference between two related samples or paired data. Based on the calculation of model evaluation metrics such as MAE, R2, MRE, etc., the Wilcoxon test calculates the signs and ranks of the differences for each pair of samples to obtain a test statistic, determining whether there is a significant difference in the performance of the two models. The null hypothesis typically indicates no difference. If the Z-value exceeds the critical value of ±1.96 and the p-value is less than 0.05, the null hypothesis is rejected, indicating that there is a statistically significant difference in model performance [47,48,49]. Through this test, it can be confirmed that the performance difference between models is real, rather than due to random fluctuations.

In the above formula, W is the signed-rank statistic, di = xi − yi is the difference between each pair of samples, and sgn(di) is the rank of the absolute value of the difference. E(W) is the expected value, n is the number of paired samples, SE(W) is the standard error, Z is the standardized test statistic, and P represents the probability that the null hypothesis is true.

3.2.7. Explainable AI Analysis with SHAP Framework

To gain a deeper understanding of the internal decision-making logic of the “black-box” machine learning model and quantitatively reveal the mechanisms through which various influencing factors affect landslide runout distance, this study applied the SHAP interpretability framework [28] to the optimal model SHAP, based on Shapley values from cooperative game theory, assigns a contribution value to each feature for every sample, allowing for the evaluation of feature importance at a global level. At a local level, SHAP can analyze the nonlinear relationship between individual features and the predicted results, as well as their potential threshold effects through dependence plots. This analysis is a key step in linking model predictions to physical mechanisms.

4. Results

4.1. Landslide Inventory and Runout Sample Dataset

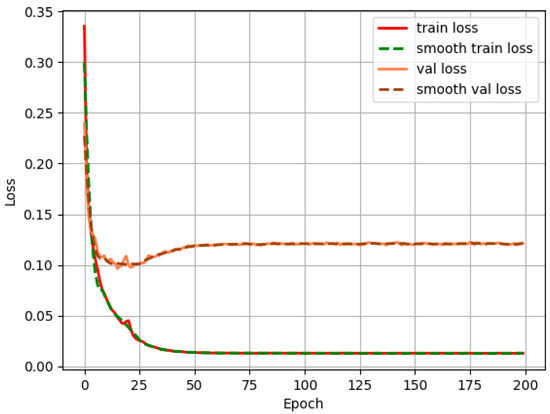

Based on the RAC-Unet model, this study successfully achieved high-precision automated identification of grouped shallow landslides in the study area. During the model training process, dynamic monitoring of the loss curve ensured the stable convergence of the model’s performance, providing crucial support for this high-precision recognition result (Figure 7). As shown in the experimental results in Table 3, the RAC-Unet model, which integrates ResNet50, CBAM, and ASPP modules, outperforms the baseline U-Net model across all evaluation metrics. Its precision, recall, F1 score, and MIoU reach 89.9%, 88.6%, 90.3%, and 88.6%, respectively, indicating that the model exhibits excellent landslide boundary identification ability and overall performance in complex backgrounds.

Figure 7.

RAC-Unet model training curve.

Table 3.

Ablation study results of the RAC-Unet model and its variants, evaluated using precision, recall, F1 score, and MIoU.

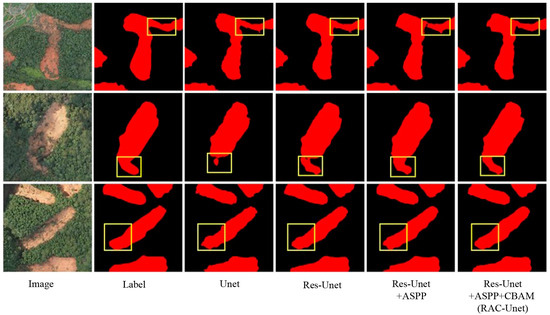

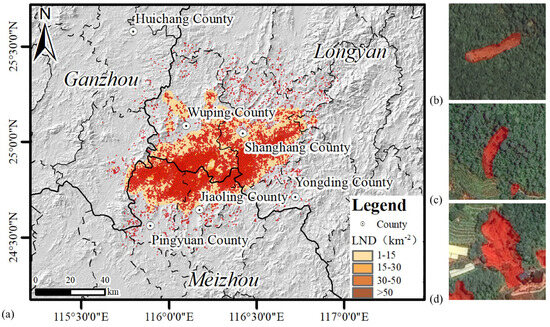

The visual comparison results in Figure 8 further validate the accuracy of the RAC-Unet identification outcomes. Compared to the baseline U-Net model, RAC-Unet effectively improves the continuity and integrity of the landslide boundaries, significantly reducing false positives and missed detections in areas with complex textures. In total, the model successfully identified 34,376 shallow landslides across the entire study area; the landslide number density (LND) and spatial distribution are shown in Figure 9a. Figure 9b–d present part of the interpreted real results, intuitively demonstrating the accuracy and details of the landslide interpretation work, and providing a solid data foundation for subsequent analysis, providing a solid data foundation for subsequent analysis.

Figure 8.

Visual comparison of landslide identification results from different model variants, demonstrating the performance improvement of RAC-Unet.

Figure 9.

RAC-Unet model interpretation results: (a) spatial density distribution; (b–d) partial display of interpretation results.

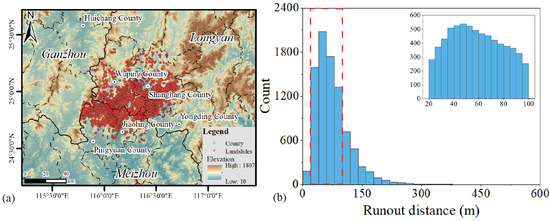

Based on the selection criteria described in Section 3.2.2, visually select the obtained interpretation results to construct a standardized sample database for jump distance analysis. The final 8875 landslide samples all meet the condition of having no significant obstacles at the leading edge of their runout. Their spatial distribution and runout distance statistical characteristics are shown in Figure 10. Statistical analysis indicates that the majority of the landslide runout distances are concentrated in the 20–100 m range, with the maximum runout distance reaching 497.87 m. The establishment of this high-quality sample database provides a fundamental guarantee for the reliable training of the data-driven model.

Figure 10.

Characteristics of the compiled landslide dataset for runout analysis: (a) spatial distribution of the 8875 selected samples; (b) statistical histogram of landslide runout distance, with the red dashed box indicating the zoomed-in area showing where the landslide runout distance is most concentrated.

4.2. Variable Association Test and Redundancy Diagnostic Results

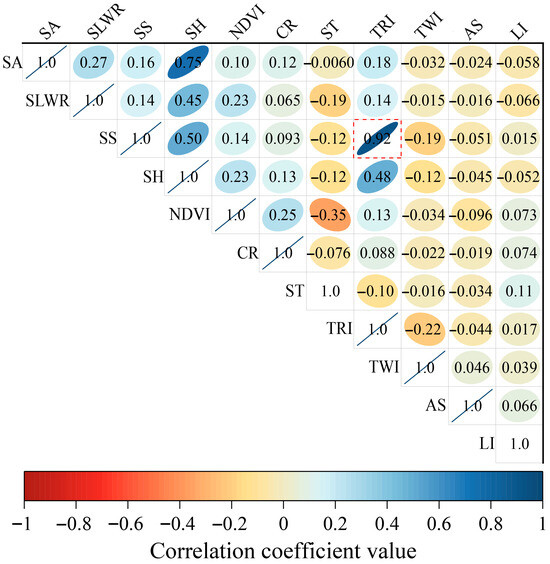

The Spearman correlation analysis heatmap (Figure 11) shows that the correlation coefficient between TRI and SS is 0.92, exceeding the threshold of 0.8, indicating a very strong linear relationship between the two variables. Combined with the VIF analysis results (as shown in Table 4), the VIF values for the core variables are as follows: SS is 4.69, TRI is 4.35, SA is 2.14, SH is 3.07, and the VIF values for SLWR, NDVI, and CR are 1.31, 1.2, and 1.06, respectively. The VIF values for the other variables are all below 2, and none of the VIF values exceed 10, indicating no severe multicollinearity issues overall, with only a strong correlation between TRI and SS. Considering that SS has clear physical mechanisms supporting its influence on landslide movement behavior and contains all the core information relied upon by TRI, the study excludes TRI and retains the remaining 10 influencing factors for subsequent data-driven model training.

Figure 11.

Heatmap of Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients among the initial predictor variables. The red dashed boxes in the figure highlight the pairs of factors that exhibit strong rank correlations.

Table 4.

The VIF analysis results of each factor.

4.3. Optimal Hyperparameter Combination and Model Performance

4.3.1. Hyperparameter Optimization Results

After Bayesian optimization, the hyperparameters corresponding to the optimal performance of each model have been identified. These hyperparameters (such as learning rate, number of iterations, regularization coefficient, etc.) are the key configurations that support the model in achieving the best fitting accuracy and generalization stability for the current task. Their specific values have been systematically organized in Table 5, clearly presenting the optimal parameter combinations for different models. This result provides precise parameter references for subsequent model performance comparison, effect analysis, and experimental replication.

Table 5.

Optimal Hyperparameter Combinations for Each Model.

4.3.2. Performance and Generalization of Runout Assessment Models

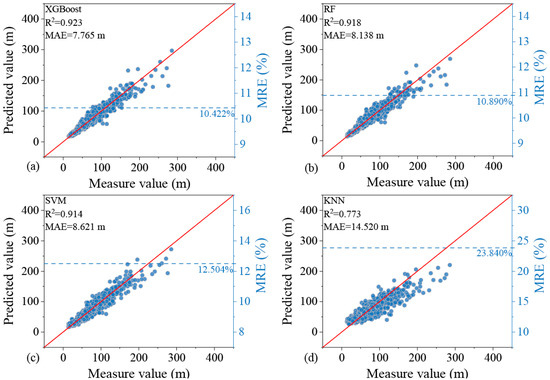

The performance comparison of the four machine learning models on the test set is shown in Figure 12. Among the four models, Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) and Random Forest (RF) performed the best. The R2 of the XGBoost model is 0.923, with a Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of 7.765 m and MRE of 10.422%. The RF model has an R2 of 0.918, MAE of 8.138 m, and MRE of 10.89%. XGBoost outperforms RF in all metrics. Although the Support Vector Machine (SVM) model shows some fitting ability, its MAE is significantly higher than the tree ensemble models. The K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) model’s predictive performance is far inferior to the other three, with the lowest reliability. Therefore, XGBoost was selected as the optimal model for further analysis and interpretation.

Figure 12.

Performance comparison of the four machine learning models on the test set for runout distance prediction: (a) XGBoost, (b) RF, (c) SVM, and (d) KNN.

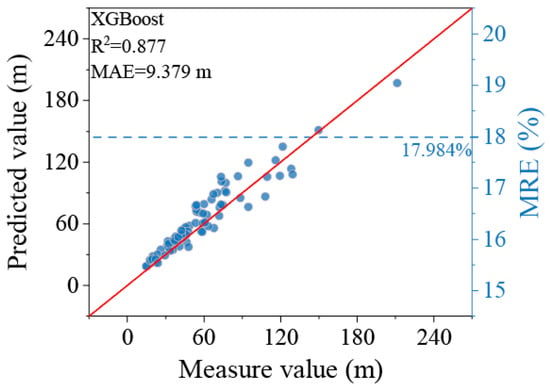

To test the model’s generalization ability, the trained XGBoost model was directly applied to an independent external dataset from the 2022 Wuping landslide event. As shown in Figure 13, the model achieved a performance of R2 = 0.877 and MAE = 9.379 m in this external validation. Although the error slightly increased due to the limited sample size, this result fully demonstrates that the model built in this study can effectively transfer and apply to landslide disasters induced by different rainfall events within the same region, showing good robustness and practical value.

Figure 13.

Scatter plot of the external validation test, applying the trained XGBoost model to the independent 2022 landslide event in Wuping County.

4.3.3. Model Comparison Significance

According to the evaluation criteria in Section 3.2.5 (a Z value exceeding ±1.96 and a p value < 0.05 is considered statistically significant), the performance difference between XGBoost and SVM is statistically significant (p = 2 × 10−8, Z = −5.610127). Interpreting the Z value, it indicates that XGBoost performs significantly better than SVM. The comparison between XGBoost and RF (p = 0.738162, Z = −0.334289) as well as between XGBoost and KNN (p = 0.050838, Z = −1.952849) did not reach statistical significance, and XGBoost did not show any disadvantage. Additionally, the performance difference between RF and SVM meets the significance criteria (p = 0.000076, Z = −3.958305), indicating a statistically significant difference. However, the comparisons between RF and KNN and between KNN and SVM showed no statistical significance (Table 6).

Table 6.

Model significance analysis.

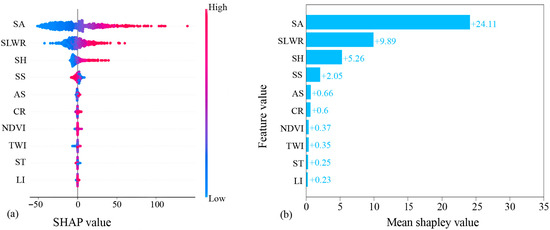

4.4. Influence Mechanisms of Controlling Factors Revealed by Explainable AI

Using the SHAP interpretability analysis framework, this study systematically reveals the impact mechanism of each feature on the XGBoost model’s test results. As shown in Figure 14, the global feature importance ranking clearly indicates SA (SHAP = 24.11), with its contribution far exceeding that of other variables. SLWR (SHAP = 9.89), SH (SHAP = 5.26), and SS (SHAP = 2.05) form the second tier of key influencing factors, while other factors, such as slope aspect and rainfall, show relatively limited contributions.

Figure 14.

Global interpretation of the optimal XGBoost model using SHAP: (a) mean absolute SHAP values for feature importance ranking; (b) summary plot showing the distribution of SHAP values versus feature values for all predictors.

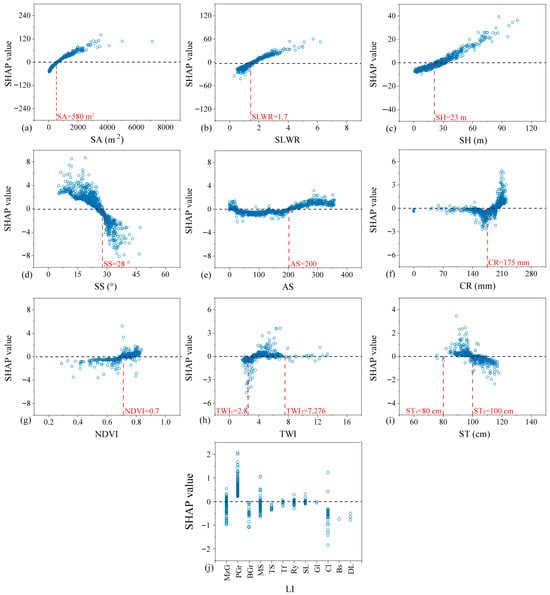

Figure 15 further jointly reveals the nonlinear action patterns and potential physical mechanisms of key factors. SA exhibits a clear positive scaling effect, where its contribution to runout distance sharply increases once the source area exceeds approximately 580 m2, in accordance with the mechanical principle that larger landslide volumes generate greater kinetic energy and move further [33]. SLWR significantly enhances its contribution to runout distance once the ratio exceeds 1.7, reflecting how elongated shapes favor the concentration of energy along the primary sliding direction and reduce lateral dissipation [37]. SH shows a more pronounced positive effect after surpassing 23 m, directly reflecting the control of initial potential energy on runout distance. SS exhibits a complex nonlinear relationship. Within SS less than 28°, runout distance increases with slope, which may be related to the efficiency of converting potential energy to kinetic energy, while overly steep slopes may lead to mechanical disintegration and energy dissipation, which suppresses runout distance.

Figure 15.

SHAP dependence plots illustrating the marginal effect of key predictors on the model output: (a) SA; (b) SLWR; (c) SH; (d) SS; (e) AS; (f) CR; (g) NDVI; (h) TWI; (i) ST; (j) LI.

Additionally, SHAP analysis also quantifies the contributions of other factors: For AS, southward and southwestward slopes are more prone to long-distance runout; CR greater than 175 mm significantly triggers runout. NDVI values above 0.7 exhibit a sliding-triggering effect. In areas with moderate TWI values (2.8–7.276), moisture accumulation remains unsaturated, making long-distance runout more likely to occur, and ST between 80 and 100 cm contributes the most to the development of weak layers. LI in the region is granite, whose weathered residual layer exhibits high porosity and low cohesion, making it susceptible to instability and long-runout under rainfall conditions.

4.5. A Simplified Predictive Model for Practical Application

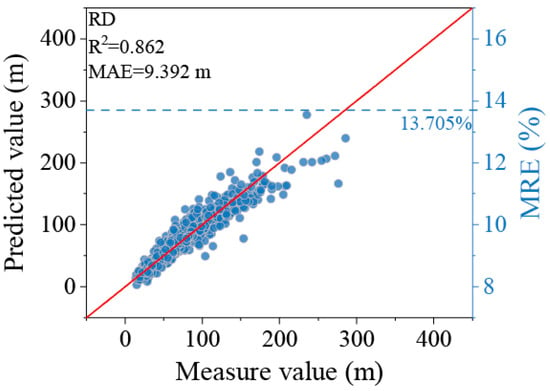

Based on the key influencing factors identified through SHAP analysis and their clear physical meanings, this study further developed a simplified model that combines prediction accuracy with high practicality for rapid response and on-site assessment of geological disasters in the Southeast Hilly Region. Considering that SH is difficult to obtain quickly before a landslide occurs, we ultimately selected the top three most important factors that are easy to measure on-site—SA, SLWR, and SS—as the predictor variables. Through multivariate nonlinear regression analysis, the following landslide runout distance (RD) prediction model was constructed:

The model demonstrates a high goodness-of-fit (R2 = 0.862), indicating that it effectively captures the complex nonlinear relationship between the target variable and the predictor factors. As shown in Figure 16, the predicted values of the model align well with the actual observed values across the entire data range. Despite using only three input parameters, the model still achieves high predictive performance. Its structure is simple, and the parameters have clear physical meanings, making it a powerful and easily interpretable tool for the rapid prediction of landslide runout distance.

Figure 16.

Scatter plot of predicted versus observed runout distance for the simplified multivariate nonlinear regression model.

In the Sobol sensitivity analysis of landslide runout displacement for the multivariate nonlinear regression model, the total-order index results show (Table 7) that SA contributes the most, with a value of 0.6009, making it the primary factor affecting the uncertainty of landslide runout displacement. SLWR follows with an index of 0.3987, making a significant contribution to displacement fluctuation. The SS index is only 0.0002, and its own contribution, as well as its interaction with other variables.

Table 7.

Parameter sensitivity analysis.

5. Discussion

This study successfully developed an integrated analysis framework for predicting landslide travel distances, with the core contribution lying in effectively linking the ability of deep learning to address the sample bottleneck problem and the advantages of explainable machine learning in revealing physical mechanisms. Compared to studies relying on manual visual interpretation or single physical models [13,18], this research is the first to use the RAC-Unet model to automatically generate a reliable shallow landslide sample database containing 8875 samples, laying the foundation for subsequent training of high-performance, high-robustness data-driven models and effectively overcoming the challenges of acquiring and rapidly processing data, which are commonly faced by traditional machine learning methods in this field.

The results of the study confirmed the model’s excellent performance in predicting landslide travel distance (R2 = 0.923). The Wilcoxon signed-rank test showed that the performance difference between the XGBoost and SVM models was the most significant (p = 2 × 10−8, Z = −5.610127), with XGBoost significantly outperforming models such as RF and KNN. The success of this model is attributed not only to its ability to handle complex nonlinear relationships but also to the feature interaction mechanisms revealed by SHAP analysis, which are highly consistent with physical laws. Source area (SA) is the primary control factor, showing a positive scale effect (with a threshold of approximately 580 square meters), consistent with the landslide volume (scale) theory emphasized by Lombardo et al. [36]. When the source area length-to-width ratio (SLWR) exceeds 1.7, the travel distance significantly increases, providing direct support for Li et al.’s [37] morphological control theory (narrow, elongated shapes help concentrate sliding directions and reduce lateral energy dissipation). These findings combine data-driven prediction with clear mechanical principles, greatly enhancing the model’s credibility and scientific value.

Based on the physical mechanism insights extracted from SHAP analysis, this study further derived and constructed a simplified multivariable nonlinear regression model within the innovative integrated framework. The model’s coefficient of determination (R2) reached 0.862, demonstrating its strong engineering practicality and a clear advantage over existing methods. Existing methods generally rely on complex multidimensional parameters, some of which require long-term data collection through specialized equipment and have high computational demands. When the sample size is limited, the prediction accuracy significantly decreases. In contrast, the model supported by this integrated framework requires only three key parameters easily obtainable in engineering fieldwork, without the need for complex computational capabilities. Even in emergency scenarios with insufficient data or limited computational resources, the model can maintain stable, high prediction accuracy, quickly completing pre-disaster risk assessments and post-disaster loss quantification. In comparison, existing methods often face issues such as parameter acquisition delays, difficulties in adapting to computational resources, and large accuracy fluctuations in such scenarios, failing to meet the timeliness and reliability requirements for emergency decision-making. The core value of this model lies not only in transforming complex machine learning results into simple decision-making tools directly applicable to engineering scenarios but also in breaking through the bottleneck of existing methods that cannot balance “parameter thresholds, computational demands, and scenario adaptability”, providing a more efficient and reliable technical path for engineering emergency assessments.

It is worth noting that the study still has limitations: First, sample selection and source area delineation still involve subjective human judgment, which may introduce potential bias. Second, the model is essentially a “phenomenological empirical correlation model,” and the geometric characteristics of the source area in pre-disaster scenarios need to be predicted through susceptibility analysis or expert experience, as it has not yet achieved full physical process simulation. Third, although the model demonstrated good generalization ability in two events in the border area of Fujian, Guangdong, and Jiangxi, its applicability in different climate zones and lithological combinations still requires more external case validation.

Future research can advance in two directions: First, extending upstream to explore the combination of slope unit and susceptibility analysis, developing intelligent methods for automatic source area identification and parameterization, to enhance the model’s capability in actual pre-disaster predictions. Second, extending downstream to continuously train and calibrate the model with landslide event data from different geological and geographical environments, enhancing its generalizability and robustness, ultimately promoting the development of this framework into a dynamic landslide risk assessment platform applicable to different geological environments.

6. Conclusions

This study addresses the core scientific issue of predicting rainfall-induced shallow landslide travel distances by constructing an integrated research framework that combines deep learning with explainable machine learning. Through multi-model collaboration and the incorporation of physical mechanisms, this framework overcomes the shortcomings of traditional methods, which are often “dependent on manually limited samples, single models, lack of physical support, weak interpretability, high data requirements, and implementation difficulties.” Using the major landslide disaster in June 2024 at the border of Fujian, Guangdong, and Jiangxi as a case study, the framework successfully achieved large-scale landslide identification, high-precision travel distance evaluation, and the elucidation of influencing factors in a fully integrated analysis process.

The core contributions of this study are reflected in three aspects: First, the deep learning model RAC-Unet can efficiently and accurately interpret remote sensing imagery, constructing a large-scale standardized landslide sample database containing 8875 samples, which effectively solves the “sample bottleneck” problem of traditional data-driven methods. Second, based on this sample database, the XGBoost model was verified as the optimal algorithm for predicting landslide travel distances (R2 = 0.923), demonstrating high accuracy and good regional generalization ability. Furthermore, through SHAP explainability analysis, three key control factors were identified: source area (SA, with a threshold of approximately 580 square meters, exhibiting a scale effect), source area length-to-width ratio (SLWR, where travel distance significantly increases when it exceeds 1.7), and slope angle (SS) and slope height (SH), which together influence the conversion efficiency of potential energy into kinetic energy. These findings provide data-driven new evidence for classical landslide kinematics theory. Third, based on insights into physical mechanisms, a simplified multivariable nonlinear regression model was constructed (R2 = 0.862). This model achieves accurate prediction of landslide travel distances using only three easily obtainable parameters in engineering scenarios, avoiding the problems of existing methods, such as “complex parameters, high computational requirements, and poor adaptability in emergency scenarios.” It successfully converts complex algorithms into practical engineering tools, significantly enhancing the application value of the research findings in pre-disaster assessments and emergency responses.

In summary, this study not only deepens the understanding of the dynamic mechanisms of rainfall-induced shallow landslides but also constructs a “first identify, then assess, and finally understand” risk management loop for landslides. It provides scientific theoretical support, reliable technical tools, and a research paradigm for responding to geological disasters under extreme climatic conditions.

Author Contributions

X.Y.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. Y.W.: Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Visualization, Writing—original draft. W.F.: Investigation, Resources, Funding acquisition, Project administration. J.Z.: Investigation, Data curation. Z.X.: Investigation. R.H.: Data curation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was sponsored by the State Key Laboratory of Geohazard Prevention and Geoenvironment Protection Independent Research Project (Grant No. SKLGP2024Z025), and the Opening Fund of the Key Laboratory of Geohazard Prevention of Hilly Mountains, Ministry of Natural Resources (Fujian Key Laboratory of Geohazard Prevention) (Grant No. FJKLGH2024K005).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Bellugi, D.G.; Milledge, D.G.; Cuffey, K.M.; Dietrich, W.E.; Larsen, L.G. Controls on the Size Distributions of Shallow Landslides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2021855118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Ye, P.; Ma, E.; Xu, Q.; Li, W. Threshold Prediction Model for the Occurrence of Shallow Soil Landslides in Red Beds Triggered by Heavy Rainfall. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2024, 83, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Wang, F. Factors Controlling the Formation and Movement of Clustered Shallow Landslides Triggered by the Extreme Rainstorm in July 2023 in Beijing, China. Geomorphology 2025, 478, 109728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Feng, W.; Yi, X.; Liu, K.; Guo, C.; Tang, X.; Wu, Z. Clustered Shallow Landslides Triggered by Heavy Rainfall in May 2022 in Wuping County, Fujian Province, China. Bull. Eng. Geol. Env. 2025, 84, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Feng, W.; Yi, X.; Zhao, Y.; Ding, Z.; Wang, Y. Clustered Shallow Landslides Caused by Extreme Typhoon Rainstorms in Zixing County, Hunan Province, China, from July 26 to 28, 2024. Landslides 2025, 22, 2141–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Wang, F.; Fu, Z.; Feng, Y.; You, Q.; Li, S. Characterizing the Clustered Landslides Triggered by Extreme Rainfall during the 2024 Typhoon Gaemi in Zixing City, Hunan Province, China. Landslides 2025, 22, 2311–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Wang, F.; Ma, H.; You, Q.; Feng, Y. Records of Shallow Landslides Triggered by Extreme Rainfall in July 2024 in Zixing, China. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Zhao, L.; Qin, Y.; Yang, T.; Chen, S. Clustered Landslides Induced by Rainfall in Jiangwan Town, Shaoguan City, Guangdong Province, China. Landslides 2025, 22, 1325–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Zhao, J.; Feng, W.; Guo, C.; Zhao, Y.; Xue, Z.; Li, S. Data-Driven Insights into the Characteristics and Drivers of the June 16, 2024 Clustered Shallow Landslides in Southeastern China. Landslides 2025, 22, 3049–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Semnani, S.J. Important Considerations in Machine Learning-Based Landslide Susceptibility Assessment under Future Climate Conditions. Acta Geotech. 2025, 20, 475–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Spatial Prediction and Mapping of Landslide Susceptibility Using Machine Learning Models. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 8367–8385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Wang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Uddin, M.G.; Xu, Z.; Chang, X.; Zhang, Y. Landslide Susceptibility Assessment Using Information Quantity and Machine Learning Integrated Models: A Case Study of Sichuan Province, Southwestern China. Earth Sci. Inform. 2025, 18, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Hamada, M.; He, C.; Wang, Y.; Zou, Y. An Empirical Model for Landslide Travel Distance Prediction in Wenchuan Earthquake Area. Landslides 2014, 11, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B. Landslides Triggered by the 2018 Mw 7.5 Palu Supershear Earthquake in Indonesia. Eng. Geol. 2021, 294, 106406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattanji, T.; Moriwaki, H. Morphometric Analysis of Relic Landslides Using Detailed Landslide Distribution Maps: Implications for Forecasting Travel Distance of Future Landslides. Geomorphology 2009, 103, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatopoulos, C.A.; Di, B. Analytical and Approximate Expressions Predicting Post-Failure Landslide Displacement Using the Multi-Block Model and Energy Methods. Landslides 2015, 12, 1207–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Wei, W.; Ye, W.; Meng, X.; Wu, W. Predicting Landslide Sliding Distance Based on Energy Dissipation and Mass Point Kinematics. Nat. Hazards 2019, 96, 1367–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zeng, R.; Meng, X.; Zhao, S.; Meng, X.; Yao, Y.; Wang, H.; Guo, W.; Chen, G.; Zhang, Y. Estimating Landslide Sliding Distance Based on an Improved Heim Sled Model. Catena 2021, 204, 105401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.; Peng, J. A Coupled Slope Cutting—A Prolonged Rainfall-Induced Loess Landslide: A 17 October 2011 Case Study. Bull. Eng. Geol. Env. 2014, 73, 997–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.; Su, L.; Bian, C.; Zhao, B.; Geng, X. An AI-Based Method for Estimating the Potential Runout Distance of Post-Seismic Debris Flows. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2024, 15, 608–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.; Geng, X. Travel Distance Estimation of Landslide-Induced Debris Flows by Machine Learning Method in Nepal Himalaya after the Gorkha Earthquake. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2024, 83, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogrizović, M.; Drašković, D.; Bojić, D. Quality Assurance Strategies for Machine Learning Applications in Big Data Analytics: An Overview. J. Big Data 2024, 11, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, N.S.; Sharma, K.V. Comprehensive Review of Remote Sensing Integration with Deep Learning in Landslide Forecasting and Future Directions. Nat. Hazards 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Li, L.; Qiang, Y.; Xu, X.; Liang, S.; Chen, T.; Yang, W.; Zhang, Y. A Method for Landslide Identification and Detection in High-Precision Aerial Imagery: Progressive CBAM-U-Net Model. Earth Sci. Inform. 2024, 17, 5487–5498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şener, A.; Ergen, B. LandslideSegNet: An Effective Deep Learning Network for Landslide Segmentation Using Remote Sensing Imagery. Earth Sci. Inform. 2024, 17, 3963–3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. The Research on Landslide Detection in Remote Sensing Images Based on Improved DeepLabv3+ Method. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giarola, A.; Meisina, C.; Tarolli, P.; Zucca, F.; Galve, J.P.; Bordoni, M. A Data-Driven Method for the Estimation of Shallow Landslide Runout. Catena 2024, 234, 107573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Erion, G.; Chen, H.; DeGrave, A.; Prutkin, J.M.; Nair, B.; Katz, R.; Himmelfarb, J.; Bansal, N.; Lee, S.-I. From Local Explanations to Global Understanding with Explainable AI for Trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2020, 2, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Liu, G.; Zhao, X.; Sun, K.; Chen, Y.; Song, Z.; Xue, K.; Yang, M. Landslide Susceptibility Assessment Based on an Interpretable Coupled FR-RF Model: A Case Study of Longyan City, Fujian Province, Southeast China. China Geol. 2025, 8, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Bai, H.; Lan, B.; Wu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Yan, L.; Ma, X. Spatial–Temporal Distribution and Failure Mechanism of Group-Occurring Landslides in Mibei Village, Longchuan County, Guangdong, China. Landslides 2022, 19, 1957–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, A.; Shan, J.; Chen, H.; Bao, H.; Xia, H.; Li, Z.; Liu, X. Mesoscale Characteristics of Exceptionally Heavy Rainfall during 4–6 May 2023 in Jiangxi, China. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1505.04597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1512.03385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-C.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Rethinking Atrous Convolution for Semantic Image Segmentation. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.05587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.06521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, L.; Tanyas, H.; Huser, R.; Guzzetti, F.; Castro-Camilo, D. Landslide Size Matters: A New Data-Driven, Spatial Prototype. Eng. Geol. 2021, 293, 106288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Lan, H.; Strom, A.; Macciotta, R. Landslide Longitudinal Shape: A New Concept for Complementing Landslide Aspect Ratio. Landslides 2022, 19, 1143–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Zhang, L.M.; Chen, H.X.; Fei, K.; Hong, Y. Topography and Geology Effects on Travel Distances of Natural Terrain Landslides: Evidence from a Large Multi-Temporal Landslide Inventory in Hong Kong. Eng. Geol. 2021, 292, 106266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zou, Q.; Zhou, B.; Jiang, Y.; Cui, J.; Yao, H.; Zhou, W. Estimation of Shallow Landslide Susceptibility Incorporating the Impacts of Vegetation on Slope Stability. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2023, 14, 618–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wu, W.; Yang, W.; Liu, M. Examining the Contribution of Lithology and Precipitation to the Performance of Earthquake-Induced Landslide Hazard Prediction. Front. Earth Sci. 2024, 12, 1431203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, C.; Dorren, L.; Schwarz, M.; Moos, C.; Seijmonsbergen, A.C.; Van Loon, E.E. Predicting the Thickness of Shallow Landslides in Switzerland Using Machine Learning. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2025, 25, 467–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Zhu, C.; Huang, Y.; Sun, J. Impact of Terrain Variation on Landslide Mobility: Insights from DEM Simulations. Comput. Geotech. 2025, 179, 107050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capitani, M.; Ribolini, A.; Bini, M. The Slope Aspect: A Predisposing Factor for Landsliding? Comptes Rendus. Géosci. 2013, 345, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcântara, E.; Baião, C.F.; Guimarães, Y.C.; Mantovani, J.R.; Marengo, J.A. Machine Learning Reveals Lithology and Soil as Critical Parameters in Landslide Susceptibility for Petrópolis (Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil). Nat. Hazards Res. 2025, 5, 539–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H. Assessing Landslide Susceptibility Based on Hybrid Best-First Decision Tree with Ensemble Learning Model. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 147, 109968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, C.; Dorren, L.; Cohen, D.; Seijmonsbergen, A.C.; Van Loon, E.E. Optimisation and Application of a High-Resolution Shallow Landslide Model at Regional Scale. Nat. Hazards 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, C.; Ha, H.; Thong Tran, X.; Ha Vu, T.; Duy Bui, Q. Landslide Susceptibility and Building Exposure Assessment Using Machine Learning Models and Geospatial Analysis Techniques. Adv. Space Res. 2024, 74, 5489–5513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, J.; Yunus, A.P.; Bui, D.T.; Merghadi, A.; Sahana, M.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, C.-W.; Han, Z.; Pham, B.T. Improved Landslide Assessment Using Support Vector Machine with Bagging, Boosting, and Stacking Ensemble Machine Learning Framework in a Mountainous Watershed, Japan. Landslides 2020, 17, 641–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzampoglou, P.; Loukidis, D.; Anastasiades, A.; Tsangaratos, P. Advanced Machine Learning Techniques for Enhanced Landslide Susceptibility Mapping: Integrating Geotechnical Parameters in the Case of Southwestern Cyprus. Earth Sci. Inform. 2024, 18, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).