Highlights

What are the main findings?

- We present a machine learning framework to map the spatial distribution of minerals on Mars.

- Our framework utilises the Self-Organising Map and k-means clustering to identify clusters of spectral signatures of minerals.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- Our framework can identify the spatial distribution of minerals on Mars, even in complex spectral environments.

- The SOM model output is interpretable and provides intuitive guidance for mineral exploration.

Abstract

Planetary exploration missions have acquired a growing amount of remote sensing data, offering a reliable basis for studying the geological evolution of planetary bodies such as Mars. In recent years, machine learning models have emerged as powerful tools for remote sensing by providing scalable and adaptive solutions for planetary science. We present a machine learning approach to map the spatial distribution of minerals on Mars, representing a step toward large-scale automated mineral mapping. Although existing CRISM dimensionality reduction methods are useful, the feature space remains high-dimensional, and relying on RGB overlays limits the ability to preserve and detect complex relationships, increasing the risk of missing important spectral patterns. Our framework utilises the Self-Organising Map (SOM) model and k-means clustering to identify clusters of spectral signatures, which may correspond to distinct minerals. It reduces dimensionality to a two-dimensional grid while preserving key high-dimensional patterns and relationships, providing a more reliable and interpretable basis for semi-automated analysis than RGB overlays. Although the clusters can be labelled by referencing a spectral library, our framework does not require labelled data and can operate in an unsupervised manner. The framework retains full spectral dimensionality of input features. The results indicate that our framework can identify the spatial distribution of minerals on Mars, even in complex spectral environments with overlapping features. Moreover, the SOM model output is interpretable rather than a black box, providing intuitive guidance for mineral exploration when applied in a semi-automated workflow.

1. Introduction

Since the start of its mission in 2006, the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) [1] has delivered high-resolution hyperspectral observations of the Martian surface. Hyperspectral sensors capture data across hundreds of spectral bands, which have enabled better mineral identification than multi-spectral techniques [2]. This advancement, combined with the expanding availability of hyperspectral datasets, has led to a growing body of machine learning research focused on hyperspectral remote sensing [3,4]. The CRISM Targeted Empirical Record (TER) product suite, released in 2016, provides atmospherically and photometrically corrected hyperspectral data for targeted regions of Mars. This data offers valuable information on the composition and spatial distribution of surface minerals, thereby contributing to our understanding of the planet’s geological history and past environmental conditions [5,6,7].

The value of hyperspectral data for mineralogical investigation is not unique to Mars, with similar frameworks applied in other planetary contexts. For example, the Moon Mineralogy Mapper is a state of-the-art imaging spectrometer designed to provide high-spectral-resolution data across large areas of the Moon’s surface, with the goal of identifying mineral and rock compositions [8]. A comprehensive understanding of the lunar surface is essential in preparation for future crewed Artemis missions [9] that aim to establish a long-term presence on the Moon [10]. On Earth, terrestrial mineral exploration has exploited hyperspectral data from airborne and satellite sensors, demonstrating the value of such workflows for geological mapping [11]. Furthermore, Thomas et al. [12] highlighted the application of hyperspectral infrared analysis in the study of hydrothermal alteration, underscoring the broad applicability of spectral interpretation methods across planetary surfaces.

The extraction of meaningful spectral–spatial information from hyperspectral data has traditionally relied on expert judgment and manual processes [3,13], which may not be suitable for large-scale mineral mapping due to the risk of error or omission [6]. For targeted CRISM observations, which contain 544 spectral bands, this challenge is compounded by dimensionality. Summary products and RGB overlays have been developed to reduce data into a more manageable form and enable rapid mineral detection [14], particularly when spectral signatures in a region align well with the chosen overlays. However, these approaches still leave a high-dimensional feature space, and because only three dimensions are visualised at a time, higher-order relationships are lost and subtle or overlapping features may be overlooked, leaving the same risks of error or omission unresolved. Challenges such as these are a key reason machine learning and deep learning methods have emerged as valuable tools in remote sensing [2,15], owing to their ability to capture complex, nonlinear relationships in high-dimensional remote sensing data [15]. Deep learning methods, in particular, have enabled automated feature extraction and improved classification performance [3,4]. For example, Shirmard et al. [16] utilised Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and multispectral remote sensing data to classify lithological units, with almost all test samples predicted correctly, a task that can require a large number of participants and resources if performed manually.

Hyperspectral remote sensing on Mars faces many of the same challenges experienced with terrestrial and lunar datasets, including issues such as size, high dimensionality, noise, atmospheric effects [17], and spatial variability of spectral signatures [11]. Additional complications include coarse spatial resolution, spectral ambiguity from overlapping or subdued absorption features, and surface contaminants such as dust cover and complex mixtures [7,13,18,19,20]. However, the absence of extensive validation data is more distinctive in the case of Mars, which makes Mars a valuable test bed for evaluating advanced data-driven methods in sparse and noise-prone environments. The scarcity of labelled data limits the effectiveness of supervised approaches and motivates the exploration of alternative strategies such as transfer learning and unsupervised methods for geospatial analysis. However, these strategies do not always generalise well to the target domain [21] and still benefit from some labelled data for fine-tuning purposes [22]. In this context, unsupervised learning—particularly clustering-based approaches—have become alternatives for hyperspectral data analysis [13].

Self-Organising Maps (SOMs) [23] are unsupervised neural networks that can be used for the clustering of high-dimensional data onto a two-dimensional grid while preserving topological relationships [23,24,25]. SOMs have been applied across a variety of remote sensing and Earth science contexts. SOMs have been used to cluster hyperspectral data from Baffin Island, achieving reliable differentiation of spectral features and outperforming other techniques in the presence of substantial noise [26]. In geoscientific studies, SOMs have shown promise in clustering geochemical data to identify prospective gold deposits in northern Finland [27]. More recently, SOMs have been employed to identify potential landing sites near the lunar South Pole by integrating multi-source remote sensing data, revealing spatial patterns constrained by scientific and engineering considerations [28]. These examples highlight the versatility of SOMs as a tool for unsupervised pattern recognition and feature extraction in remote sensing, geological, and planetary science research.

In this study, we present an unsupervised machine learning framework that applies SOM and k-means clustering to group spectral signatures and map the spatial distribution of minerals on Mars, moving beyond pixel-based classification and conventional RGB overlays. Even when summary products reduce the dimensionality of CRISM spectral data, the feature space remains high-dimensional, and the viewing of only three dimensions at a time cannot reliably capture or preserve complex relationships. Our framework focuses on selected regions of Mars where diagnostically interpretable remote sensing data is available for mineral classification. It retains full dimensionality of the input space, producing topology-preserving clusters that can be partially labelled using the CRISM Type Spectra Library [29] through a post-processing spectral matching step. In this way, clusters are interpretable, can be correlated with known mineral signatures, and allow for the identification of mineral distributions, even in complex spectral environments with overlapping features. Overall, the framework provides a semi-automated, scalable, and interpretable approach for exploring Martian mineralogy in the absence of extensive ground-truth data.

The rest of this paper is organised as follows: Section 2 provides background and related work, while Section 3 describes the methodology, including data processing and modelling. Section 4 presents the results, and Section 5 provides a discussion, which is followed by a conclusion in Section 6.

Target Regions, Identified Minerals, and Image Adjustments

Table 1 and the accompanying map indicate the referenced target regions, the location of specific minerals, and adjustments made to image files:

Table 1.

Target regions and, where applicable, the original [X, Y] pixel coordinates of mineral locations shown in remote sensing and overlay images used in this research. These coordinates correspond to positions prior to any image rotation. For more details, refer to Section 3.1. * The presence of Fe-olivine, Fe-oxides, or other mafic silicate minerals remains speculative and is not confirmed.

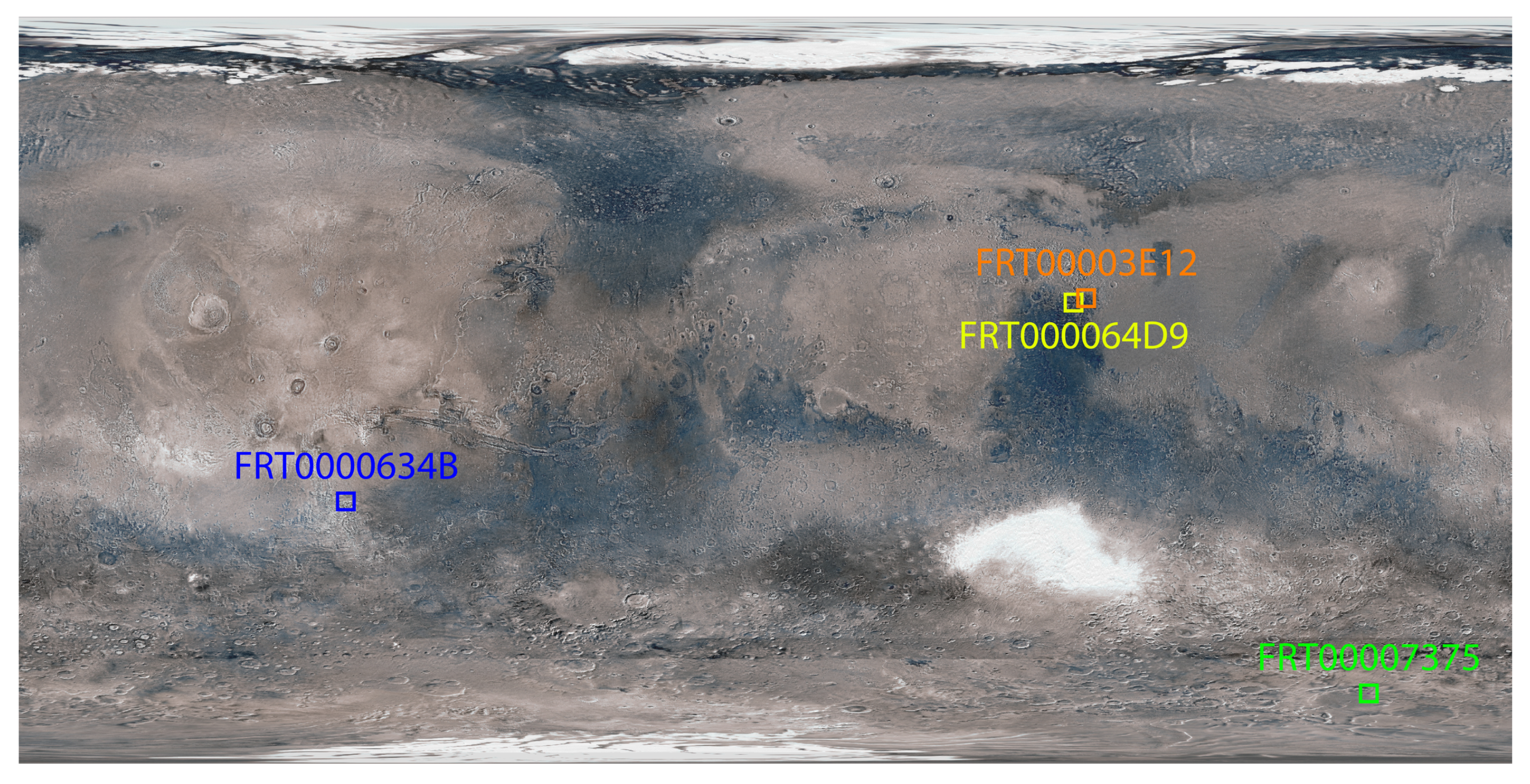

A surface image view of Mars showing the targeted regions is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Global view of Mars showing enlarged and approximate locations of the target regions.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. CRISM

Aboard NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), CRISM [1] is a high-resolution visible-to-near-infrared (VNIR) imaging spectrometer providing up to 544 spectral bands across the 362–3920 nanometre (nm) range, operating in targeted and mapping modes. The mission has produced numerous data records, such as EDRs (Experiment Data Records), TRDRs (Targeted Reduced Data Records), TERs (Targeted Empirical Records), and MTRDRs (Map-Projected Targeted Reduced Data Records), each reflecting different levels of calibration and spatial processing [30]. These datasets have played an important role in the exploration of Martian minerals by enabling the identification of minerals associated with past aqueous activity [30].

2.2. Summary Products for Data Processing

A key challenge is the variability in raw hyperspectral data, which can arise from factors such as atmospheric effects, illumination differences, surface scattering [31], and other environmental or acquisition-related influences. Spectral parameters can be used to overcome some of these difficulties, as it may not be necessary to assess the entire spectrum to identify a mineral, instead focusing on specific spectral features that can be described by a single parameter value [32]. Spectral parameters are widely used in CRISM data products and have proven to be a successful method of collapsing spectral variation into a limited number of dimensions to identify the presence of a mineral on Mars [14]; we refer to the spectral parameters as summary products to remain consistent with Viviano et al. [14]. These summary products offer several advantages over raw hyperspectral bands by (1) emphasising mineralogically meaningful absorption features, (2) reducing dimensionality while preserving domain-relevant information, and (3) improving comparability across regions with differing photometric conditions [33]. Although summary products offer these advantages over raw hyperspectral bands, developing them is inherently time-consuming, requires expert geological knowledge, and is subject to differing expert opinions on optimal formulations [13].

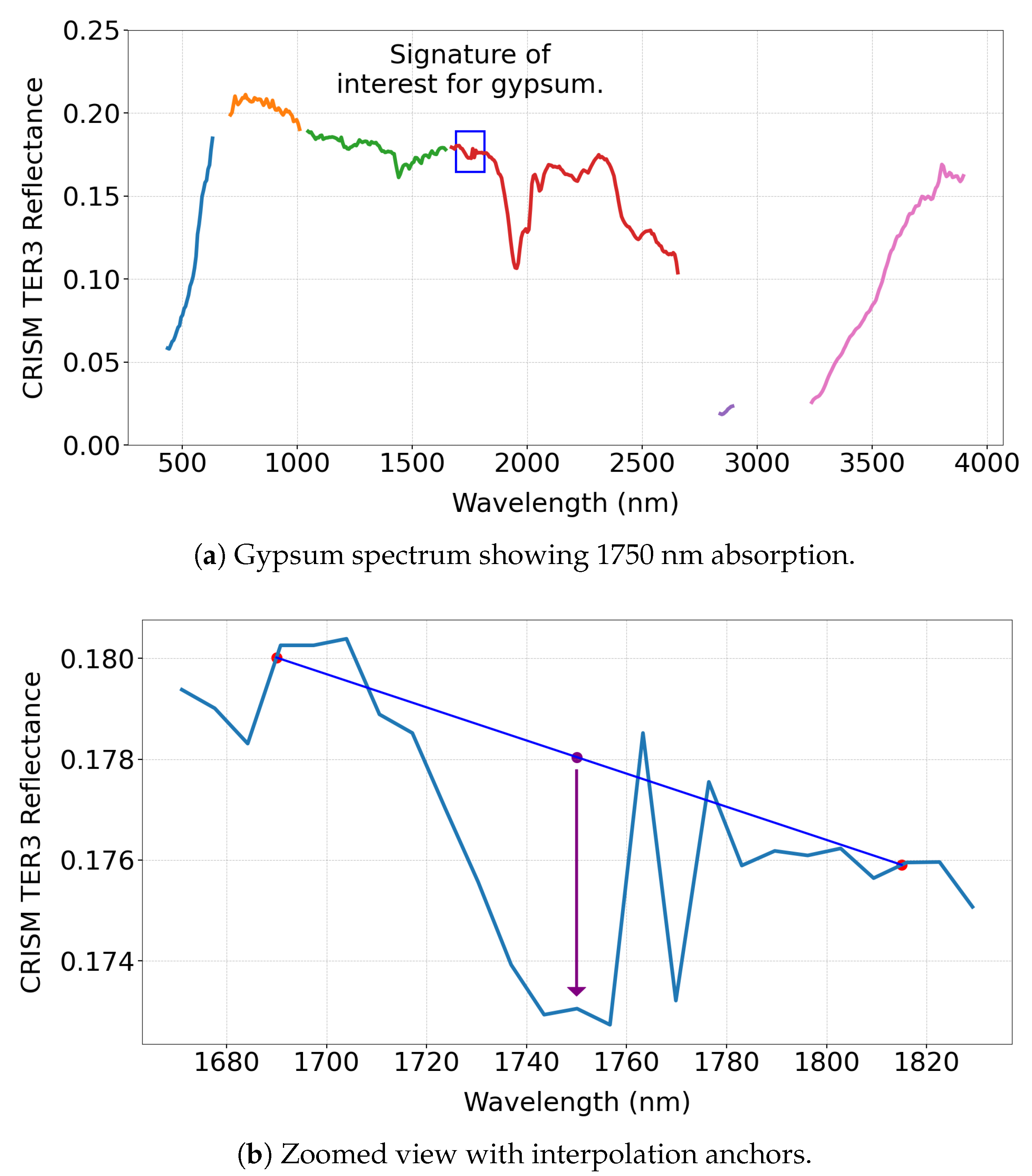

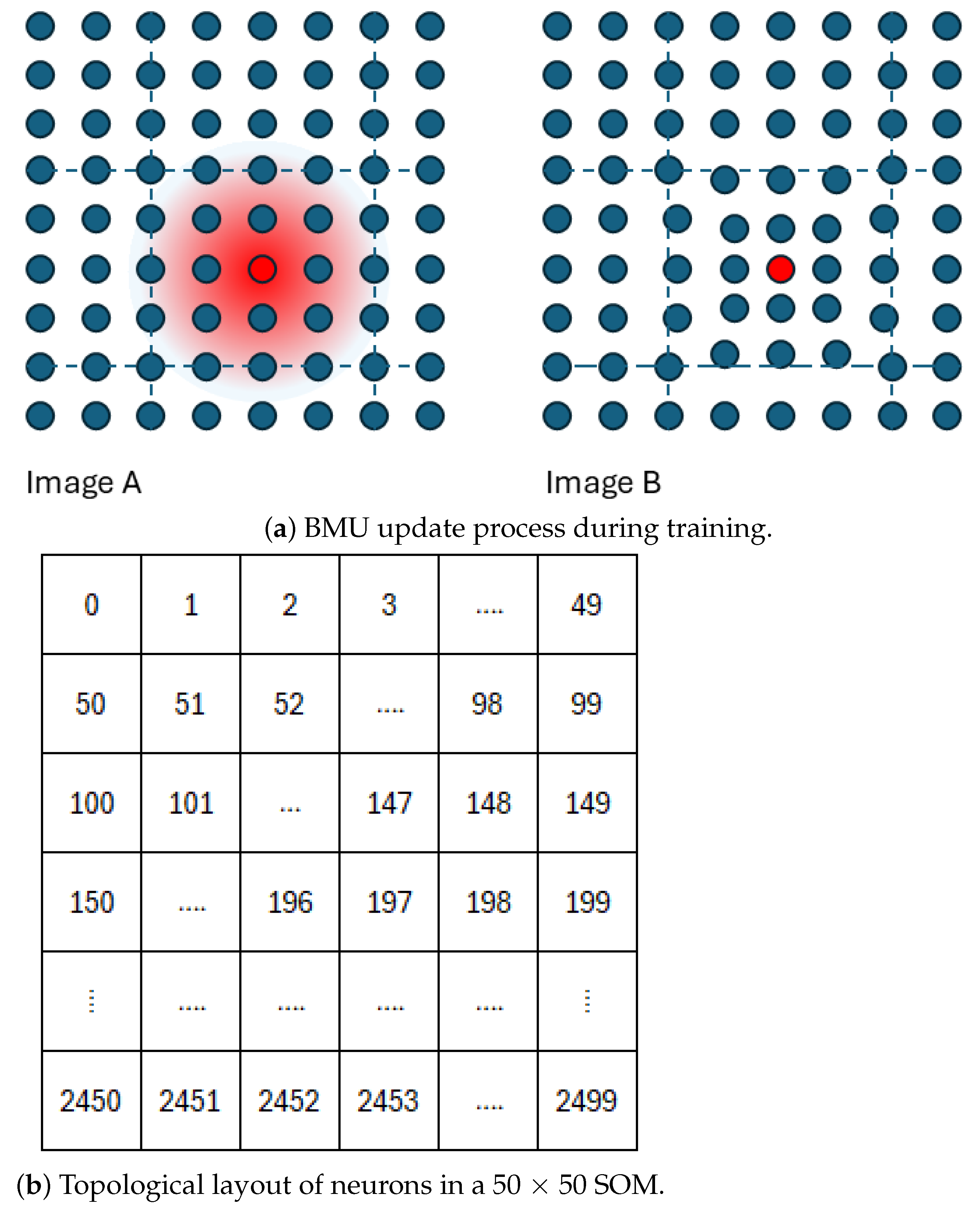

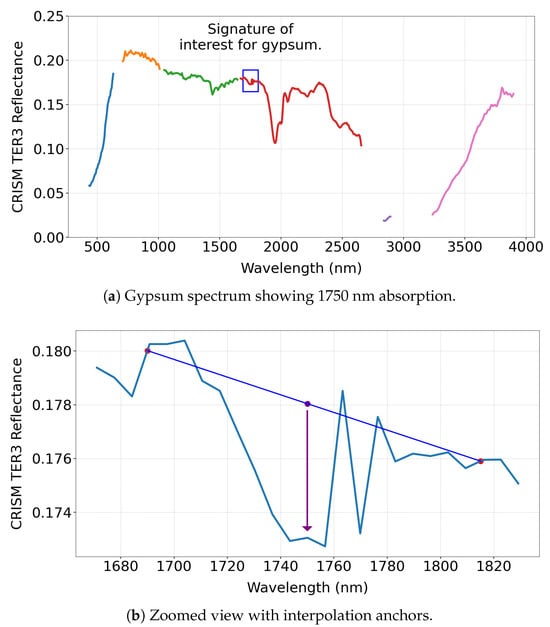

We compute BD1750_2 using hyperspectral data from the MRO CRISM Type Spectra Library as an illustrative example to demonstrate the intent of a summary product. This summary product estimates absorption near 1750 nm as follows:

The a and b parameters are weighting factors with . The value of b is approximately , and the exact ratio depends on the specific selected wavelengths, which is influenced by the kernel width. Figure 2a,b illustrate the absorption feature.

Figure 2.

(a) Gypsum spectrum highlighting the 1750 nm absorption feature. The different coloured lines indicate regions where CRISM measures the spectrum in consistent 6.55 nm increments, with breaks marking interruptions in the regular sampling pattern. (b) Zoomed-in view showing the interpolation anchors used to identify the absorption feature. (c) BD1750_2 values for 31 minerals, with only gypsum and alunite showing strong responses, demonstrating the diagnostic role of this spectral product in mineral detection.

As shown in Figure 2c, the summary product is sensitive primarily to gypsum and alunite among the 31 MRO CRISM Type Spectra Library minerals, consistent with earlier studies [14]. Notably, the absorption features remain clear, even when applied to un-normalised TER-3 data, demonstrating robustness—though normalisation is recommended if a reliable reference pixel can be identified.

2.3. Unsupervised Machine Learning

Dimensionality reduction methods such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [26,34] and Minimum Noise Fraction (MNF) [17] have been used to process hyperspectral data. PCA extracts orthogonal components based on variance, which can inadvertently prioritise noise over subtle but important absorption features. MNF aims to separate signal from noise more explicitly but may still obscure localised mineralogical signatures.

Traditional clustering algorithms such as PCA, k-means [15,34], Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs) [13,34], and DBSCAN (Density-based clustering) have been applied to hyperspectral datasets [34,35]. However, these methods come with limitations, including the need for hyperparameter tuning and assumptions about the underlying distribution of materials. Spectral unmixing approaches such as Linear Mixing Models (LMMs) [36] offer an alternative by modelling each pixel as a linear mixture of spectra from a predefined set of end members. However, their effectiveness is limited by the linear assumption [37] and reliance on a fixed spectral library, which may not capture the substantial spectral variability experienced in practice [37,38,39]. A SOM model can mitigate some of these limitations via the preservation of topological relationships. For instance, an over-dimensionalised SOM will produce an organised map of similar neurons (refer to Section 2.3.1; a neuron can be thought of as a representative vector in this instance) that can be grouped or visually identified, meaning hyperparameter tuning is not as problematic. Similarly, topology separates high-confidence regions with more distinct mineral signatures from areas with more complex and mixed surface compositions, allowing for the identification of regions where spectral variability is not as problematic.

2.3.1. Self-Organised Map (SOM)

A SOM model projects high-dimensional inputs onto a two-dimensional topological grid while preserving neighbourhood relationships [23,24,25,40]. A SOM can be envisioned as a two-dimensional jigsaw puzzle, where the completed puzzle represents an organised map of the dataset. Each puzzle piece corresponds to a neuron, acting as a reference vector or prototype that summarises a cluster of similar data points. Conceptually, a SOM neuron is akin to the centroid of a k-means cluster; however, unlike k-means, a SOM preserves the topological relationships between neurons, arranging the pieces so that their relative positions reflect the original high-dimensional input structure. In this way, the SOM maintains the integrity of the underlying patterns while providing a coherent, interpretable two-dimensional representation. Therefore, SOM models are valued for their interpretability and have been successfully applied in remote sensing tasks such as cloud type classification [40], land cover classification [41], identifying distinct types of regolith and bedrock [42], and even reconstructing underwater sound speed profiles [43]. Some key advantages of a SOM model in this context include the following:

- 1.

- High-dimensional Input Handling: A SOM model can process high-dimensional data directly, without requiring dimensionality reduction (aside from computational performance considerations). Although SOMs typically use Euclidean distance (which assumes the linearity of the input space), other distance metrics can be adopted.

- 2.

- Topological Preservation: Unlike traditional clustering algorithms, a SOM model preserves the topological structure of the input space. This is particularly useful in hyperspectral analysis and can reveal unique mineral clusters in complex situations.

- 3.

- Robustness to Over-dimensioning: The SOM’s structured output space enables intuitive interpretation, even when the number of neurons exceeds the number of distinct clusters. Over-dimensioning leads to finer topological granularity rather than fragmented or scattered clusters, so coherent patterns can be visually observed.

- 4.

- Representative Abstraction: In large-scale clustering (e.g., 270,000 × 29 summary product vectors into 100 clusters), summarising each group meaningfully can be difficult. Simple averaging of cluster members may blur subtle spectral distinctions. In contrast, SOMs assign each neuron a weight vector that captures the core spectral characteristics of the clustered instances, as well as, to a lesser extent, those of nearby clusters, without the need for post-processing.

These features make SOM models particularly compelling for mineral analysis. They support unsupervised classification in an environment where there is little to no validation data whilst yielding spatially coherent, interpretable groupings that reflect physically meaningful spectral variations.

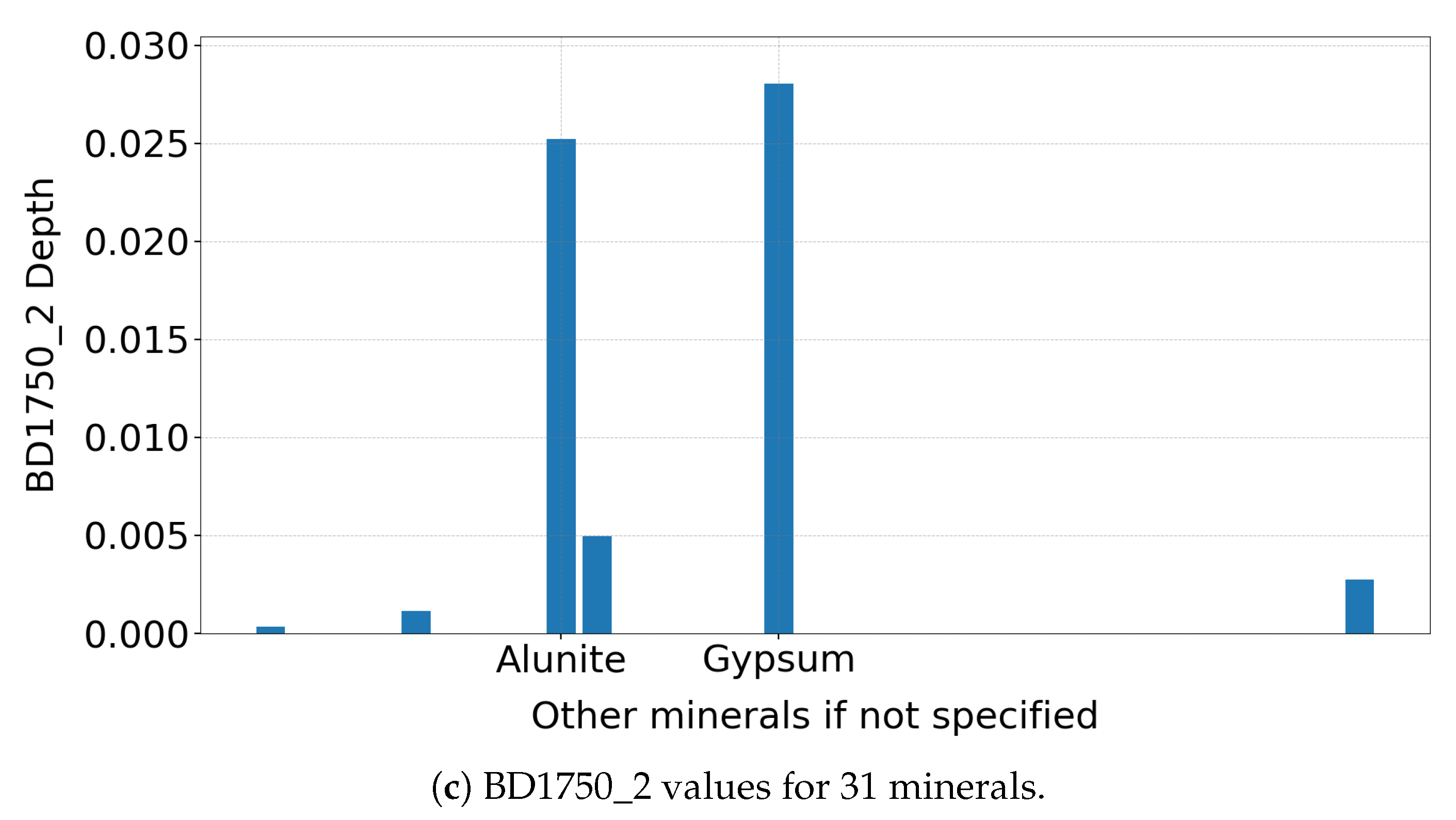

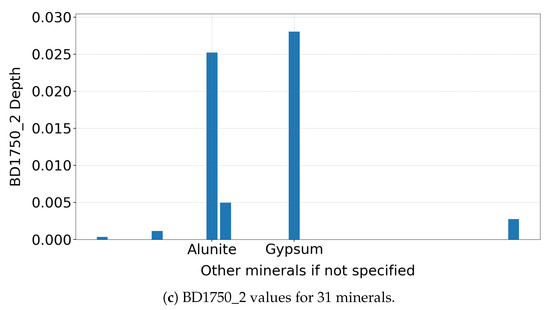

The SOM training (learning/optimisation) process is illustrated in Figure 3a. For a given input instance, the best matching neuron, also known as the Best Matching Unit (BMU), is identified based on the Euclidean distance between the input vector and each neuron’s weight vector. The neurons located within a neighbourhood radius () of the BMU are then updated based on the neurons’ distance from the BMU in the two-dimensional map grid (Figure 3a). The degree of update depends on the current learning rate and the neurons’ distance from the BMU.

Figure 3.

(a) The Best Matching Unit (BMU, red) and its radius of influence (Image A). During training, the weight vectors of neighbouring neurons are updated, with the adjustment strength decreasing with distance from the BMU. Neuron coordinates remain fixed, but their weight vectors move closer together (Image B). (b) The topological arrangement of neurons in a 50 × 50 self-organising map. Together, these panels visualise SOM training and neuron organisation.

Let denote the input vector, and let i and b represent the coordinates of neurons i and the BMU, respectively. The Euclidean distance between the coordinates of neurons i and b is given by

where and are the row and column coordinates of neuron i and and are the row and column coordinates of the BMU.

We use the Gaussian distribution to define the neighbourhood function that captures the strength of the update for neuron i at time t, as given by

We then update the weight vector () of a neuron within the neighbourhood using the following expression:

If the red neuron represents the BMU for the current input (Figure 3a), then the weight vectors of all neurons within the neighbourhood radius () are adjusted toward the input vector, scaled by their respective update factor (). Although the weight vectors of the neurons are updated, their positions on the grid remain fixed; however, the weight vectors shift toward the BMU. We retain the neuron map, including the weight vectors for each neuron, once the SOM model has completed training. We then map each pixel to a specific neuron based on the BMU for that instance.

Figure 3a presents the SOM topology maps visualised as two-dimensional arrays, where each pixel corresponds to a neuron in the model. A key consideration when configuring an SOM model is determining the number of neurons. Although limited research exists on the optimal size, a commonly cited heuristic suggests using approximately neurons, where N is the number of training samples [44].

In the case of an image with 250,000 valid pixels, this equates to around 2500 neurons, prompting our choice of a 50 × 50 grid. Our preliminary tests indicated that a 25 × 25 grid produced similar results, while grids smaller than 10 × 10 led to a loss of detail. As shown in Figure 3b, neuron indexing begins at 0 in the top-left corner and ends at 2499 in the bottom-right corner. Although our study does not refer to specific neuron coordinates, Figure 3b illustrates the standard arrangement.

2.3.2. SOM Competitive Learning

The following example illustrates the competitive learning strategy of the SOM model. In Table 2, the first grid lists numbers sequentially from 1 to 25, while the second shows the total Euclidean distance of each number from all others. While clustering similar numbers, the SOM also seeks to preserve the topological structure indicated by the second grid. Thus, numbers 1 and 25—being most dissimilar to the rest—are projected toward opposite corners; numbers 2–8 and 18–24 are positioned farther away from the centre; and the more similar middle numbers, i.e., 9–17, are grouped more centrally relative to these dominant topological patterns, effectively pushing the more distinct numbers outward.

Table 2.

Left table: Numbers ordered in a 5 × 5 grid from 1 to 25. Right table: Total Euclidean distance of each number from every other number.

If a grid is randomly initialised with numbers 1–25, training with uniformly sampled instances should lead the SOM to cluster similar numbers whilst converging on preservation of these patterns. In Table 3, the first grid shows the random initialisation, while the second shows the ordering after 100,000 training iterations.

Table 3.

Left table: Randomly initialised numbers from 1 to 25. Right table: SOM ordering after 100,000 training iterations.

The SOM successfully clusters similar numbers, with values less than 5 grouped in one corner and those above 20 in the opposite corner. Beyond this neighbourhood clustering, the model preserves the key topological structure—1 and 25 are projected as far apart as possible, occupying opposing corners, while 2–8 and 18–23 are positioned away from the central numbers. The diagonal and midlines form the core region, with extreme values in opposing corners, where the central numbers are located. Even within this central zone, the SOM creates sub-clusters, grouping lower teens in the bottom left and higher teens in the top right while still maintaining the overall topological relationships. In this way, the SOM not only clusters similar numbers but also preserves their relative topological structure—a principle that naturally extends to higher-dimensional datasets, such as spectral summary products.

2.3.3. Biased Instance Selection

For the example in Table 3, we draw new instances uniformly. When instances are biased, the SOM’s ability to cluster and learn topological patterns is reduced. For the following scenario (Table 4), the number 20 is drawn with 75% probability, while the remaining numbers share the remaining probability uniformly. Large topological patterns are still observed, but clustering is hampered as neurons converge toward 20, resulting in lower-order patterns becoming less evident.

Table 4.

Left table: Randomly initialised numbers from 1 to 25. Right table: SOM ordering after 100,000 training iterations with training instances biased toward 20 (drawn with 75% probability). Large-scale topological patterns are preserved, but neuron convergence toward 20 dilutes the ability to observe lower-order topological patterns.

2.3.4. Implications for Mineral Analysis

In mineral mapping, mixed spectra resemble the central numbers—broadly similar or relatively close in Euclidean distance (see the right-hand table of Table 2)—whereas unique spectra are analogous to 1 and 25, differing strongly from all others. As in the 5 × 5 example, the SOM projects these distinct numbers to the map’s corners and edges, since their BMUs consistently differ from the rest, while clustering similar spectra together. This approach allows the SOM to preserve the dataset’s topological relationships while effectively segregating distinct mineral groups, though care must be taken to avoid bias in the training samples.

3. Methodology

3.1. Mars Coordinate System

In this study, we use unprojected TER-3 images, in contrast to other sources that use map-projected MTRDR images, which are geo-referenced to the spherical surface of Mars (Viviano et al. [14]). Map-projected images result in a visually distorted appearance for the same target region; therefore, interpretation must be practised with care, often through comparison with topographic features or by using custom-coloured visualisations that assist in aligning spatial references. Refer to Figure 1 for a global map of Mars identifying the analysed target regions.

The coordinate system we used for Mars is [X,Y], corresponding to row × column indexing as shown in Figure 4. This aligns with the dimensions of an image file when viewed numerically.

Figure 4.

Pixel coordinate system used in this study.

We refer to Figure 1 for known mineral locations referenced in this study—these locations were originally sourced from [14]. We convert the [Y,X] coordinates provided by [14] into our [X,Y] format to ensure consistency and reproducibility. These locations serve as the source of the hyperspectral reference spectra used in the MRO CRISM Type Spectra Library for the specified minerals. In some cases, we rotated the unprojected TER-3 images by 180 degrees to match the orientation presented in [14]. We explicitly noted the rotations in the corresponding image descriptions for transparency and reproducibility, and Table 1 summarises the adjustments.

3.2. SOM Model Inputs

We use summary products derived from specific spectral absorption features [7] to cluster minerals, as these products are designed to highlight key mineral signatures. Although MTRDR image files include such products—and it was initially our intention to use them all—preliminary analysis revealed discrepancies between many MTRDR outputs and the spectral formulas intended to generate them. Consequently, we recalculated 29 summary products from TER-3 files (refer to Section 3.3), following the set used by Viviano et al. [14] (Figure A1), including those required for the RGB overlays, as these products provided greater confidence in representing the intended spectral features. Adjustments and discrepancies relative to CRISM DPIS definitions [33] for these 29 summary products are detailed in Appendix B.

Although this set provides a practical baseline, it is not sufficient for comprehensive mineral discrimination in a machine learning context. The SOM architecture can handle higher-dimensional inputs, which is desirable for reducing collinearity between mineral signatures and capturing more nuanced spectral information. Achieving this requires confidence in the input parameters and, ideally, a standardised automated procedure for generating them, which lies beyond the scope of this study but represents an important avenue for future work.

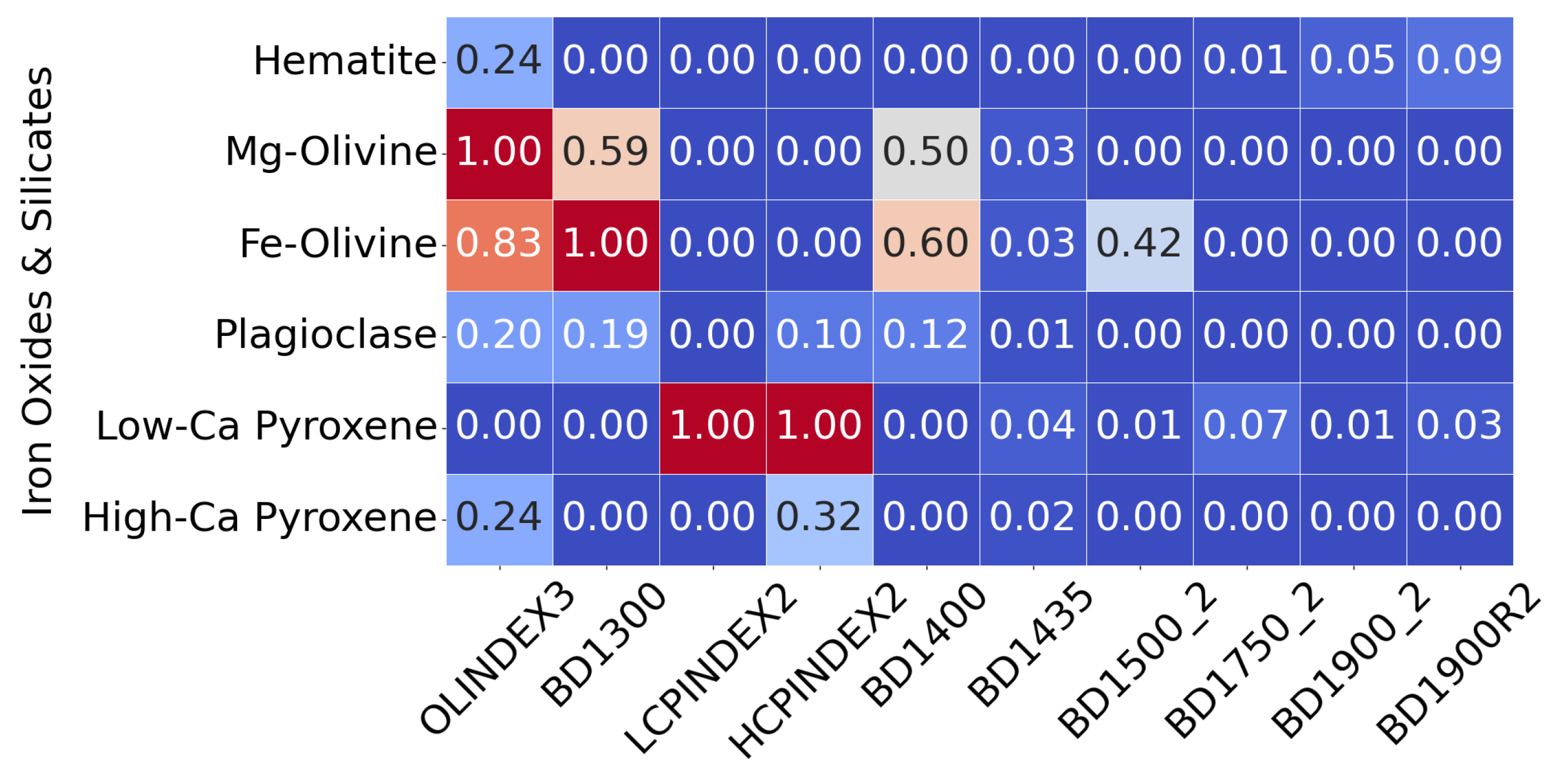

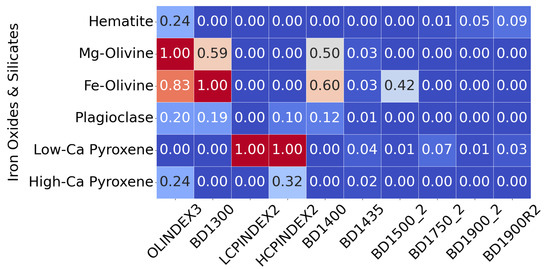

All 29 features were retained without further dimensionality reduction (e.g., PCA or feature selection) to preserve the full input space. This ensures that the SOM remains sensitive to subtle yet potentially important variations in mineral signatures across target regions. Figure 5 illustrates how these summary products were used as input to the SOM model.

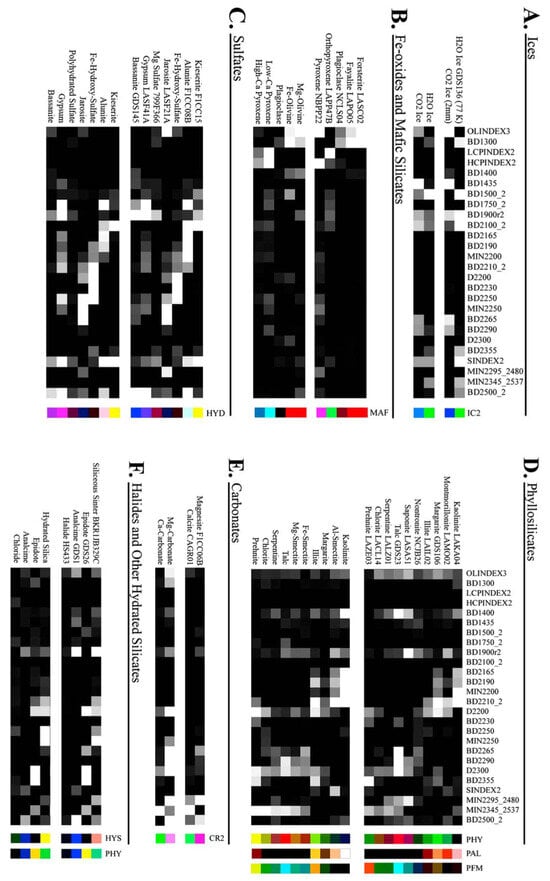

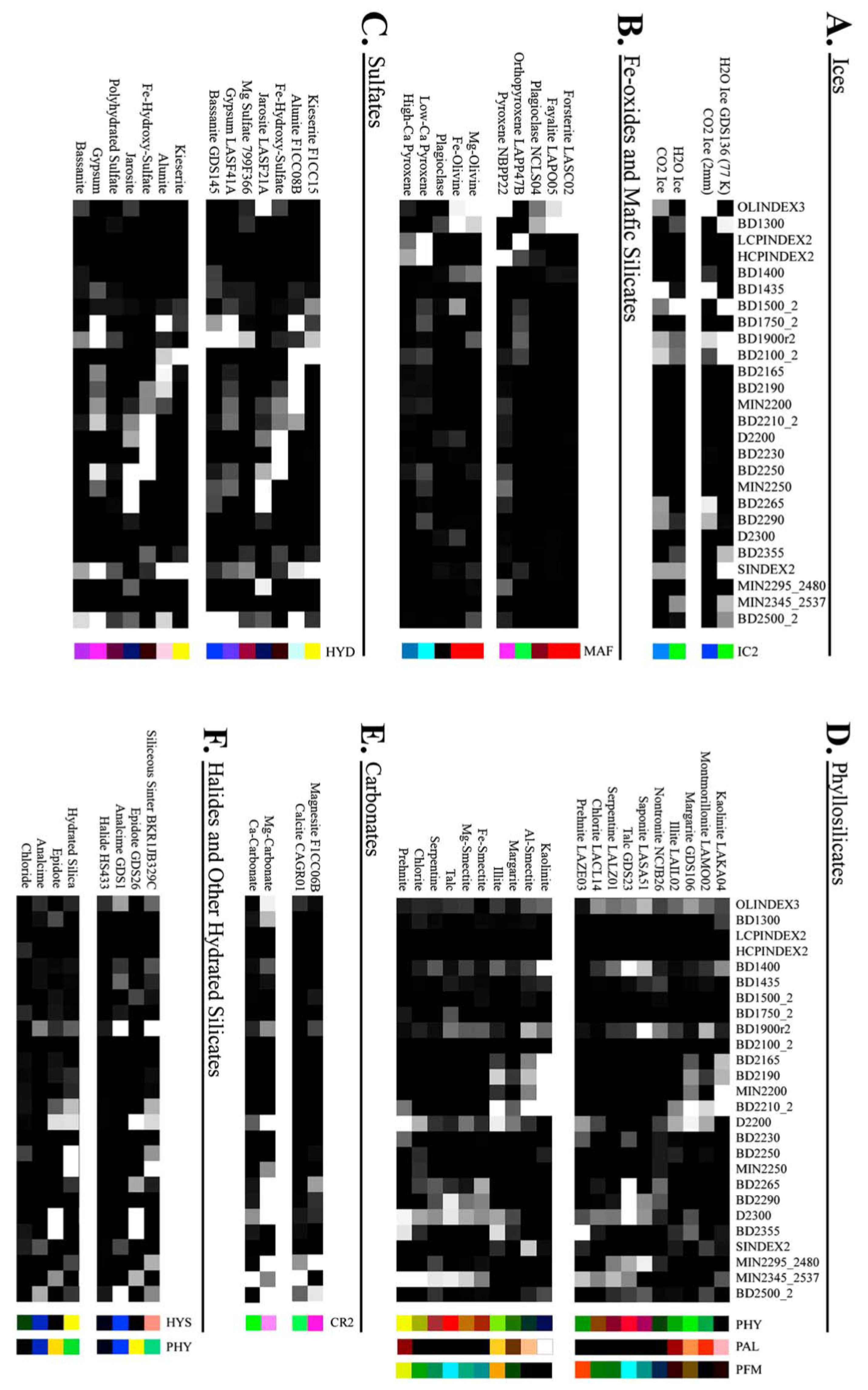

Figure 5.

This heat map illustrates how summary products serve as input features. Rather than displaying all 29 products for each pixel, it shows a subset of recalculated summary products for selected minerals from the MRO CRISM Type Spectra Library, highlighting spectral variation across mineral types. Each horizontal row can be thought of as an individual pixel from a TER-3 image file.

3.3. Data Preprocessing

We utilise two CRISM datasets in the TER format, taking the following issues into consideration:

- 1.

- Summary product recalculation: We use Targeted Empirical Record—version 3 (TER-3) files, which enable us to recalculate summary products from the original spectral measurements. TER-3 is a specific CRISM image type [33] that consists of un-projected hyperspectral observations that have been corrected for atmospheric and photometric effects for Mars.

- 2.

- Spectral labelling: We use the MRO CRISM Type Spectra Library to label clusters, which provides reference spectra for each mineral. Specifically, we use the numerator from the library—the source of which is also a pixel in a TER-3 image—where the mineral has been previously verified [29]. These spectra serve as ground-truth references to support the identification of mineral clusters detected by the SOM model. Ideally, each pixel (numerator) would be normalised using a reference pixel (denominator) and the ratio would be used to calculate summary products. Whilst the library provides a denominator for each reference spectrum, we did not adopt this approach due to uncertainty about reliably identifying a reference pixel in each TER-3 image. If done incorrectly, this could complicate comparisons between the summary products calculated from targeted TER-3 image files and library reference spectra. Spectra for each mineral contained within the library are converted into a summary product for direct comparison.

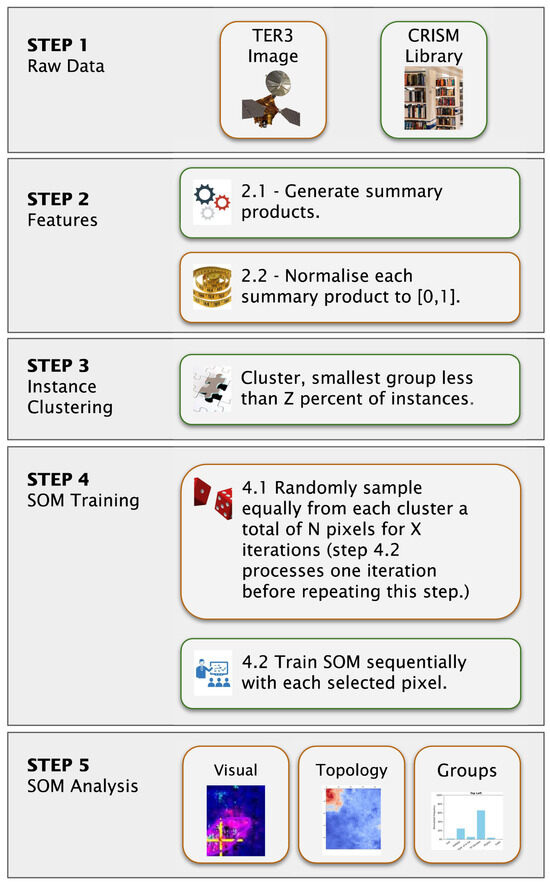

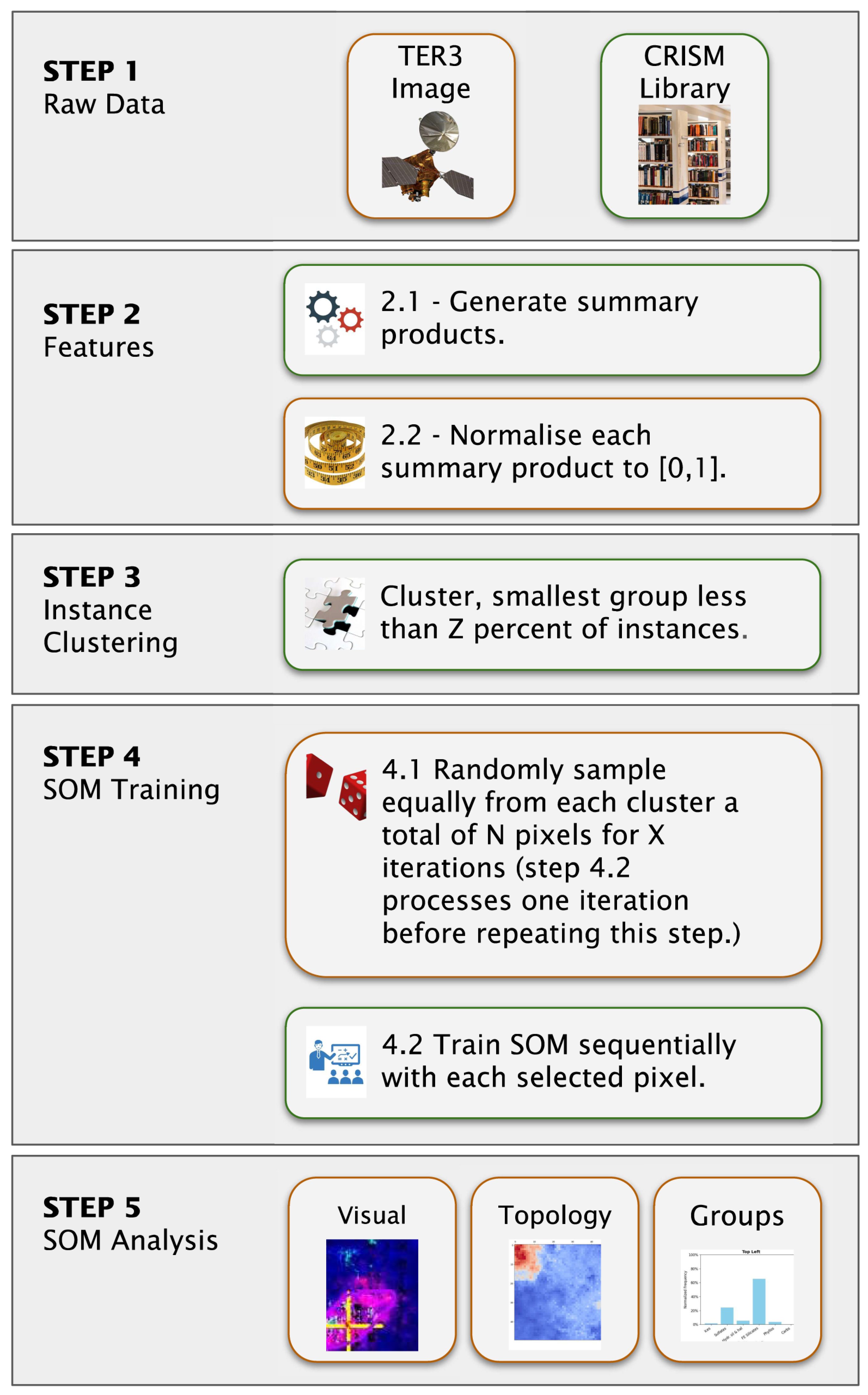

We applied a unified preprocessing pipeline to both datasets to ensure compatibility between the summary products and the reference spectra, consisting of the following steps (Figure 6, Step 2).

- We mask pixels that have a specific value of 65,535 in any frame, as this indicates invalid or missing spectral data. These pixels are excluded from analysis, and summary products are not calculated for them.

- We compute summary products for each pixel from the unmasked pixels.

- We clip any summary product values below zero to zero, although the formula for summary products does not specify a minimum bound. We refer to BD1750_2 in Equation (1), which can yield negative values, as absorption features are inherently positive by definition. This clipping approach is consistent with recommendations in the literature [14].

- We normalise all summary products to a range of [0, 1] to eliminate dimensional disparities and standardise inputs for the model.

Figure 6.

Machine learning framework illustrating the progression from raw inputs to SOM model outputs. In Step 2, we mask out the pixels with a label value of 65,535; therefore, we do not compute summary products for them. Furthermore, we clip negative summary product values to zero before normalisation. Step 4 uniformly samples a total of N pixels from each cluster generated in Step 3, repeating this process X times. Sequential updates in Step 4.2 imply that we train the SOM model one pixel at a time.

Figure 6.

Machine learning framework illustrating the progression from raw inputs to SOM model outputs. In Step 2, we mask out the pixels with a label value of 65,535; therefore, we do not compute summary products for them. Furthermore, we clip negative summary product values to zero before normalisation. Step 4 uniformly samples a total of N pixels from each cluster generated in Step 3, repeating this process X times. Sequential updates in Step 4.2 imply that we train the SOM model one pixel at a time.

Although normalisation of summary products (input features) to the [0, 1] interval promotes consistency, it also overemphasises certain mineral signatures. Ideally, the inputs should be scaled with reference to a global range of summary product values, not local target regions. For example, if the maximum values of BD1750_2 in target regions “A” and “B” were 0.005 and 0.1, respectively, the local scaling would independently scale both maximums to 1, effectively treating them as equivalent. In contrast, global scaling performed across both regions would result in scaled values of 0.05 for region “A” and 1 for region “B”. In this case, global scaling preserves the relative difference in absorption strength, maintaining the weaker BD1750_2 response in region “A” rather than inflating it to match region “B” under local scaling.

The SOM model in our framework produces several outputs: pixels identified by specific neurons corresponding to particular minerals can be visualised with false-colour or RGB overlays; topological maps representing the neuron grid can be adapted to display correlations, analytical metrics such as hit rate. Furthermore, it produces group analyses that reveal mineral associations projected toward the corners of the SOM, providing insight into the model’s topological structure.

3.4. Unsupervised Machine Learning Framework

After processing the data, as shown in our framework (Figure 6), we apply k-means clustering to group pixels based on spectral similarity. Experimentally, we select the number of clusters such that the smallest cluster contains approximately ten percent of valid pixels in an image (Figure 6—Step 3). For each training iteration (repeated “X” times), we randomly and equally sample from each cluster formed in Step 3 to generate a batch of “N” instances for a single SOM training update. This approach ensures that no single spectral group dominates the training set, maintaining diversity across iterations (Figure 6—Step 4). Clustering before sampling mitigates redundancy in the training data, preventing premature neuron convergence and allowing the SOM to learn a more meaningful representation of the spectral space (refer to Section 2.3.2 for a basic example as to why this is important).

We use each instance in a training batch to sequentially train the SOM model. We then integrate the SOM output with the MRO CRISM Type Spectra Library to produce labelled mineral clusters and topology maps. We then provide an analysis of the minerals clustered through the framework (Figure 6—Step 5).

Each neuron in our SOM model is associated with a 29-dimensional weight vector, corresponding to the summary products used as input features. We initialise these weight vectors with random values in a range of [0, 1], which assists with initial learning, as the summary products used as inputs are restricted to this range. Although this random initialisation is typically sufficient for model convergence, more structured initialisation methods could potentially accelerate learning and enhance clustering performance. We employ a competitive learning strategy based on the principles introduced by Kohonen [45] and extended to clustering tasks by Vesanto [24] to get a better organised topological map from the SOM. This involves a two-stage training process designed to first establish a rough global organisation, then refine local cluster distinctions.

- Stage 1—Rough Topological Organisation: In the initial stage, neurons are updated with a high learning rate and a large neighbourhood radius, facilitating a coarse topological structure that guides the model in later stages.

- Stage 2—Refinement: The learning rate progressively decays, and the neighbourhood radius shrinks, enabling the model to fine-tune and converge on subtle distinctions in mineral characteristics.

3.4.1. SOM Implementation

We enforce the initial organisation of the randomly initialised weights by 50 preliminary model training iterations before commencing formal training. We select the initial learning rate as and the radius as for a SOM map. The initial learning rate and radius of updated neuron nodes gradually decrease.

The SOM model undergoes 1000 iterations of formal training to cluster instances (Step 4 of Figure 6). We use 5000 instances in each iteration, randomly but equally sampled from each cluster formed in Step 3 of Figure 6. The number of clusters formed during the pre-training instance clustering process may vary, but typically, around 20 clusters are generated, with the smallest cluster containing about 2000 instances. Over 1000 iterations, each instance in the smallest cluster is expected to be used for training approximately 125 times, or once every ten iterations, ensuring that small clusters are adequately represented and not overlooked by the SOM model during training.

We relied on heuristic estimates [44] to determine the SOM model dimensions (hyperparameters such as length and width) and did not delve into hyperparameter optimisation due to a SOM’s topological organisation, which is tolerant of over-dimensioning by grouping similarly weighted neurons within, effectively forming a cluster of clusters. Our visual inspection of a neuron heat map suggests that a 50 × 50 SOM is likely over-dimensioned, as there are often topological clusters of high correlation among many neurons. Nonetheless, the impact of moderate over-dimensioning appears minimal, as the SOM’s topological structure maintains meaningful organisation by grouping highly correlated neurons into hierarchical clusters. These can be further clustered by external algorithms or interpreted through visual inspection of the neuron heat map. However, there are instances in which a 50 × 50 SOM is required to isolate a particular mineral—notably, Epidote in target region FRT0000CBE5, which was identified in additional analyses not included here. Therefore, under-dimensioning the SOM, where distinct clusters cannot be effectively separated, likely poses a greater risk than over-dimensioning, which primarily results in redundant but topologically organised clusters.

3.4.2. Cluster Labelling

In order to correlate the clusters with known mineral types, we compare the trained neuron weight vectors with processed reference spectra from the CRISM MRO Type Spectra Library. We compute the correlation scores by comparing the 29 normalised summary products of each neuron’s weight vector with the reference spectra. We assigned the neurons with higher correlation scores, indicating greater spectral similarity, tentative mineral labels. This approach enables the partial labelling of unsupervised clusters, enhancing their interpretability without requiring training data.

3.4.3. Threshold for Mineral Confidence Levels

We focused on regions identified by the top five neurons with the highest correlation to the reference spectrum to assess the spatial distribution of a labelled mineral. These neurons generally exhibited strong spectral similarity, particularly in areas where the mineral was previously confirmed to exist. However, simply selecting the top five neurons can yield misleading results in regions where the mineral is not present. Therefore, we excluded neurons with low correlation scores, even if they ranked among the top five for a given mineral. In an attempt to refine and automate this process, we explored an alternative approach.

- Correlation Calculation: We calculate the correlation of all 2500 neurons with each of the 31 mineral reference spectra in the CRISM MRO Type Spectra Library, resulting in 77,500 individual correlation values.

- Global Thresholding: The neurons are considered to have a high correlation with a mineral if their correlation exceeds the 95th percentile of all neurons. The median correlation value was also used as a threshold, with neurons correlating with the median being excluded from further consideration.

- Z-Score Transformation: For each mineral, the correlation values for each neuron were converted to z-scores (for just that mineral). A neuron was deemed to belong to a mineral if the following conditions were met:

- –

- The neuron had a high correlation with the mineral and its z-score exceeded the mean z-score for that mineral across all neurons (indicating a strong and representative correlation).

- –

- Alternatively, if the mineral’s correlation with the neuron was low, the z-score had to exceed 2 to be considered relevant.

- Rationale for the Approach: This method was adapted based on our observations that some minerals appeared to be widely distributed across a target region, while others were highly localised. The approach aimed to capture both scenarios by emphasising stronger correlations for widely distributed minerals and allowing for more flexibility with more isolated minerals.

Despite experimenting with this approach, we found that selecting the top five neurons was generally sufficient for most analyses, as our focus was on regions where the presence of specific minerals had already been reported. This method offered a straightforward yet effective way to associate SOM neuron weight vectors with known mineral signatures, delivering reliable results, without the need for complex thresholding in most cases.

3.4.4. Surface Dynamics and Temporal Variability

CRISM TER-3 images represent a snapshot in time and do not account for the temporal variability of the Martian surface, which may alter surface reflectance properties over time. No adjustments were applied in this study, and CRISM TER-3 data were used as provided. Future work may incorporate temporal correction methods to address surface dynamics such as dust deposition and seasonal ice variation.

4. Results

We present five investigations to demonstrate the ability of our framework, which utilises a SOM model to detect the spatial distribution of minerals on Mars, highlighting its advantages for mineral exploration.

- 1.

- A visual comparison of the SOM model’s ability to detect the spatial distribution of the mineral illite with reference to the distribution identified by Viviano et al. [14];

- 2.

- The SOM model’s ability to detect the specific location of the mineral low-ca pyroxene, as previously identified by Viviano et al. [14];

- 3.

- An application of the SOM model’s topological structure to identify the presence of Mg-carbonate on Mars, as previously identified by Viviano et al. [14];

- 4.

- A qualitative review of the topological organisation of mineral groups within the SOM model’s neuron grid;

- 5.

- Implementation of a semi-automated framework for mapping mineral spatial distributions without reliance on RGB overlays, leveraging the SOM’s ability to project high-dimensional spectral patterns onto a two-dimensional grid while simultaneously clustering pixels.

4.1. Mineral Classification

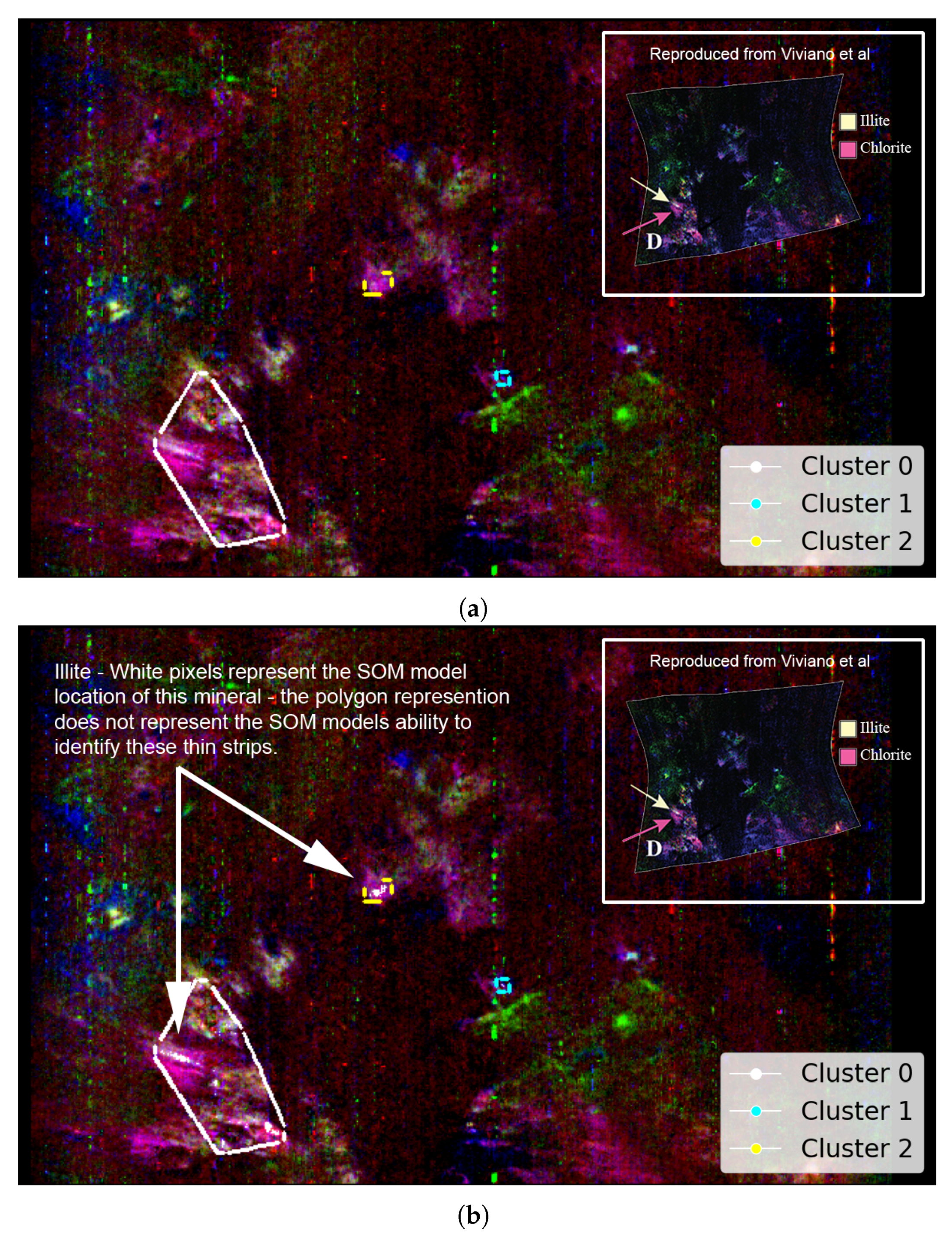

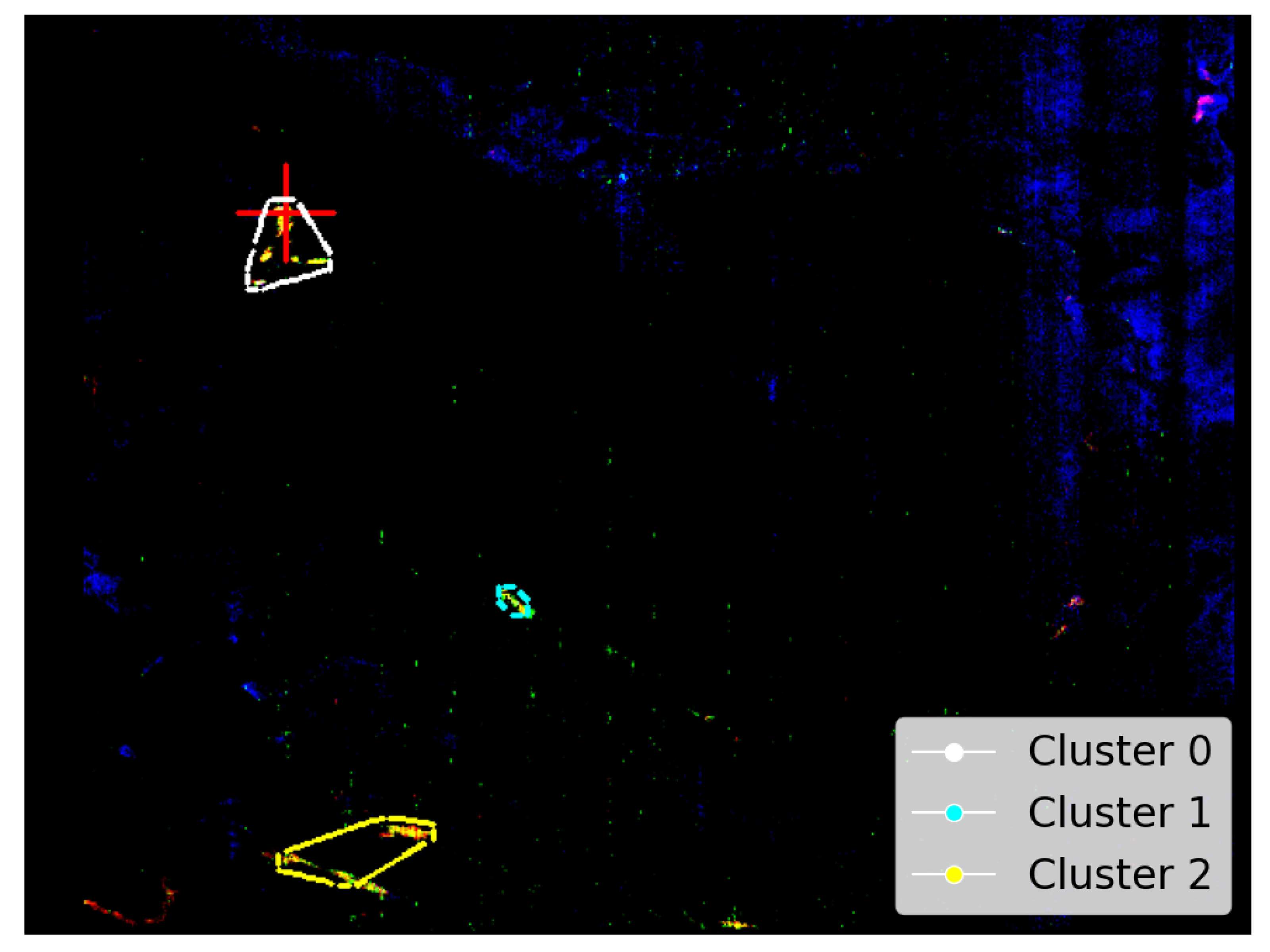

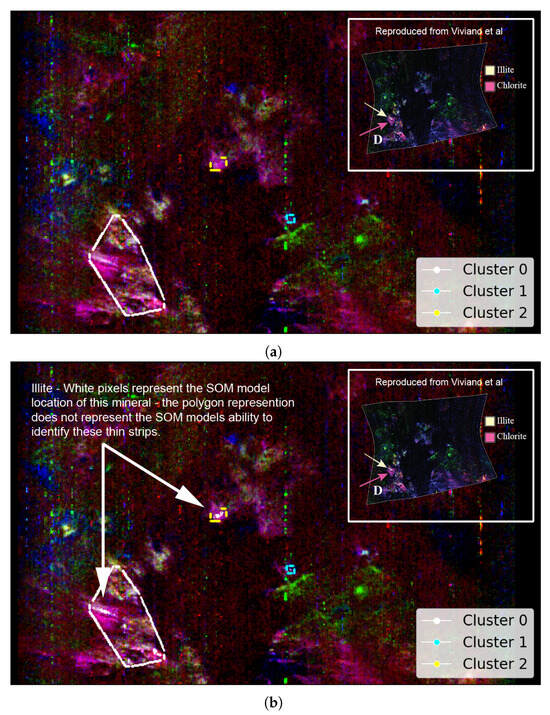

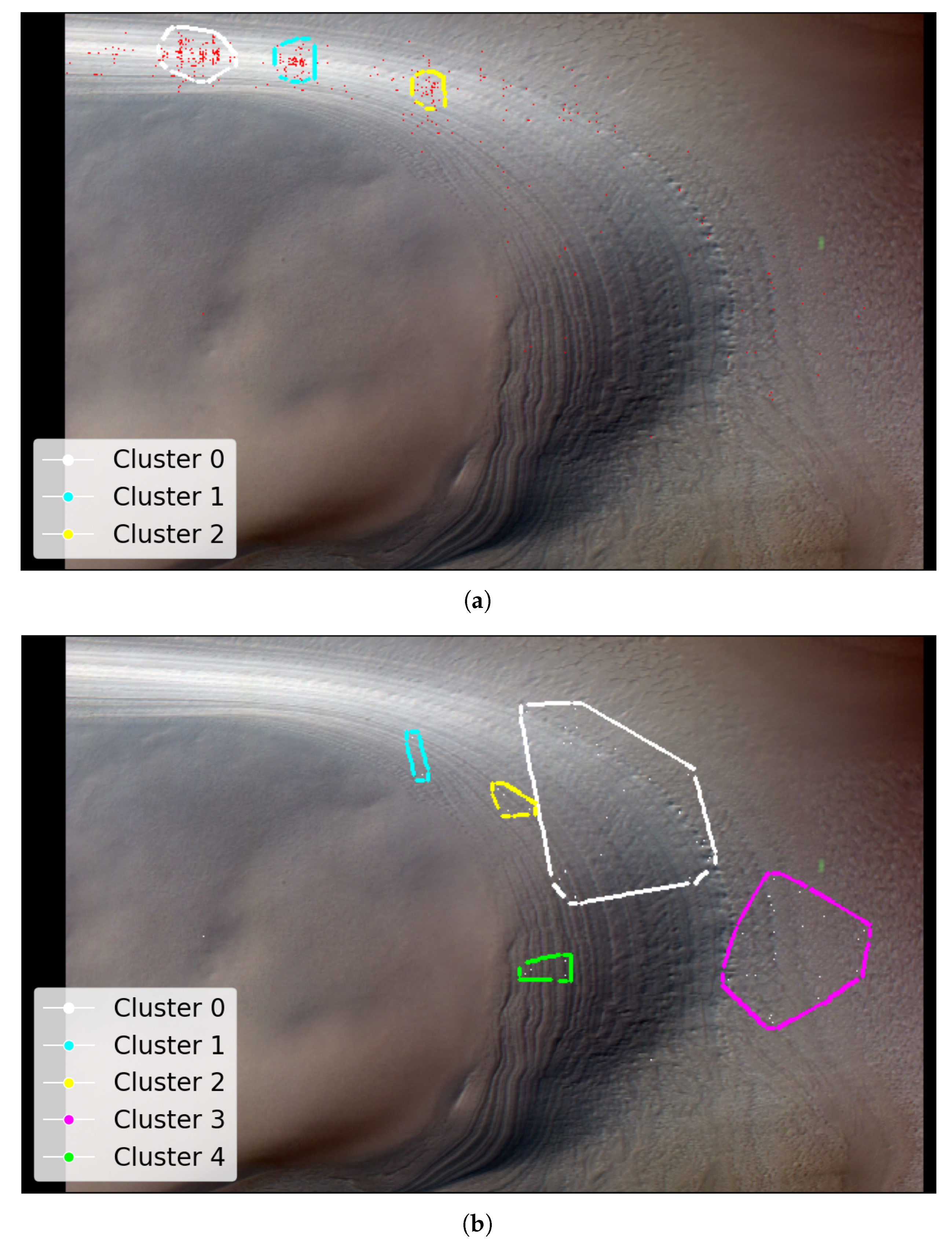

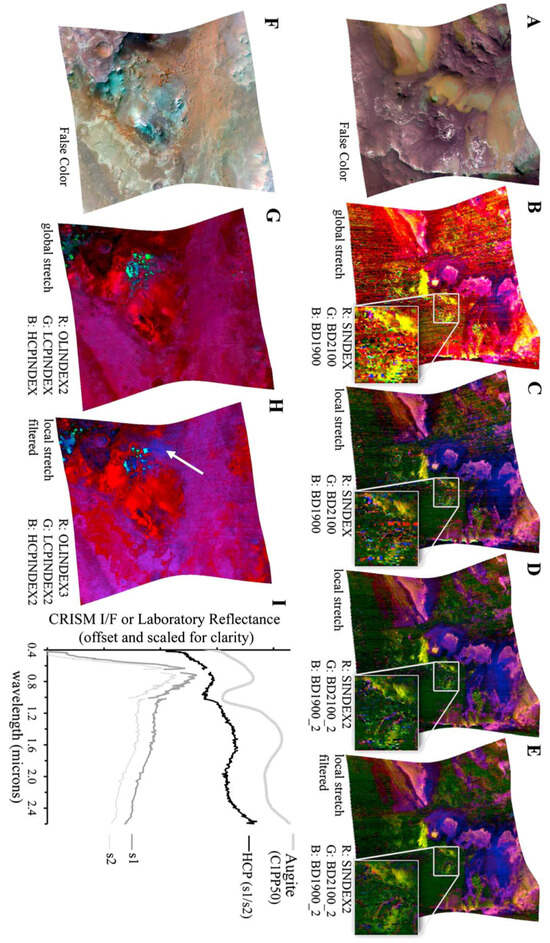

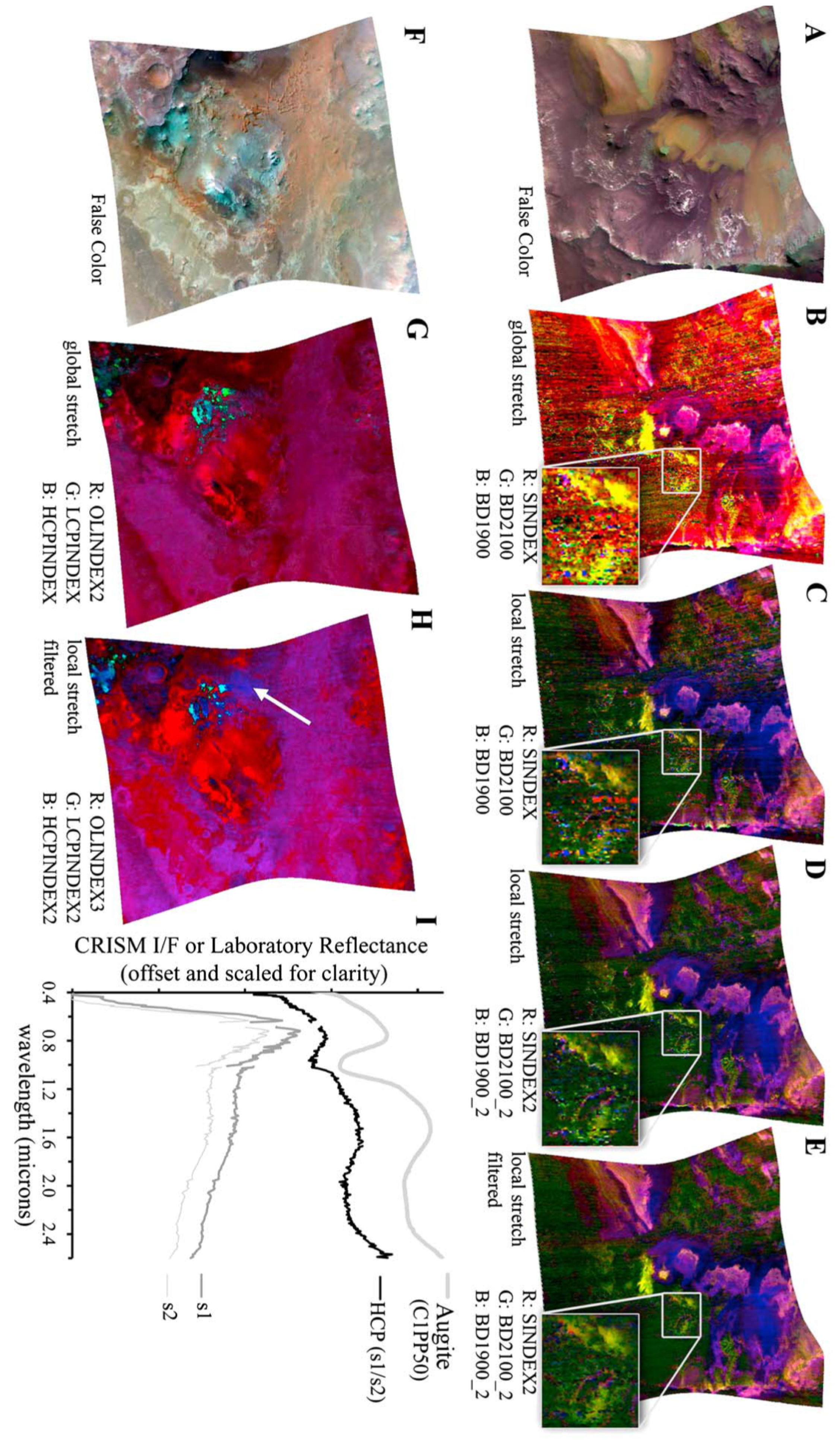

Figure A3 as reproduced from Viviano et al. [14] provides an opportunity to evaluate the SOM model’s ability to identify the spatial distribution of Martian minerals. Figure 7a shows the spatial distribution of the mineral illite as identified by the SOM model, along with our attempt to replicate image D of Figure A3. Although illite is intended to appear as pale yellow, in our overlay (Figure 7a), it appears to render as a colour closer to pale pink (a consequence of local scaling). The overlay reveals a strong alignment between the highlighted pale-pink areas and the clusters identified by the SOM model—particularly clusters 0 and 2.

Figure 7.

Our study uses image data from Viviano et al. [14] as a source of ground truth for comparison with outputs derived from the SOM model. For ease of comparison, we show a snapshot of the referenced image in the top-right corner of the corresponding panel and provide a larger version in Appendix A. We highlight the limitations of these visual comparisons in Section 3.1. Both images are rotated 180 degrees to align with Image D from Figure A3 and have a resolution of 390 × 640 pixels, with the X-axis oriented vertically to match image rows. (a) Unprojected map of FRT0000634B with an overlay based on Image D of Figure A3. Faint pale-pink areas indicate illite, with the clustering box reducing the SOM model’s ability to resolve thin strips of this mineral. (b) Pixel locations of illite identified by the top five neurons most correlated with the processed MRO CRISM Type Spectra Library. Thin white strips demonstrate the SOM model’s capacity to resolve subtle spectral differences within regions of spectrally similar pixels, as indicated by the surrounding pink shading in (a).

Although the polygonal boundary includes broad pale-pink zones—especially within cluster 0—in Figure 7a, the SOM model appears more precise in its identification of illite. Hence, Figure 7b highlights the specific regions where the SOM model detected illite as white pixels. This emphasises the model’s accuracy in pinpointing even thin strips of illite, which is not demonstrated by the broader polygon-based representation.

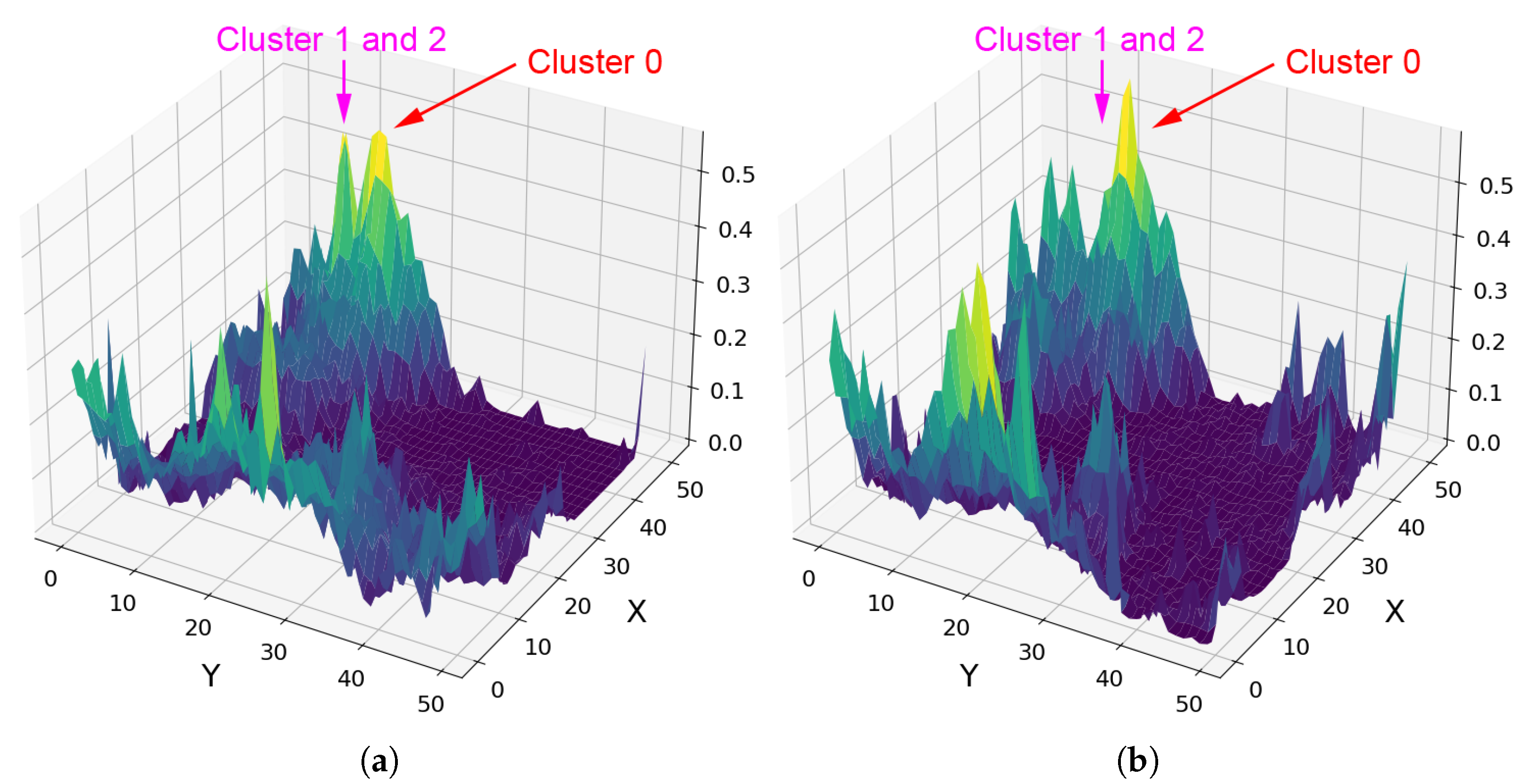

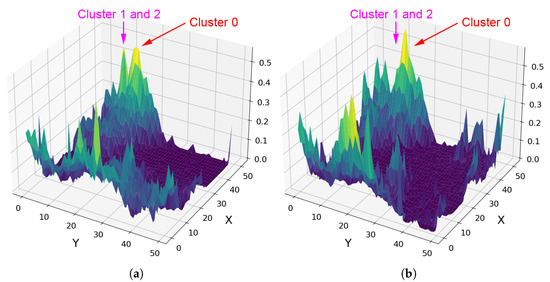

Clusters 1 and 2 in Figure 7 highlight potential illite in areas not previously verified. For all clusters, these pixels originate from the five SOM neurons most associated with illite, which are neurons 2462, 2461, 2463, 2460, and 2454—listed from highest to lowest correlation with the MRO CRISM Type Spectra Library spectrum for illite. Four neurons (2460–2463) form a compact block along the bottom row of the SOM neuron grid. The other neuron, 2454, lies apart from this block. While spectrally similar, it shows weaker and absorptions and belongs to a very similar, albeit a different SOM cluster. This separation is important—it indicates that neuron 2454 is closely related to illite-like spectra (possibly more mixed) but distinct enough for the SOM to preserve it as a separate cluster. Figure 8 illustrates this, with most high- spectra grouped to cluster 0 (containing verified illite; refer to Figure 7), with clusters 1 and 2 (refer to Figure 7) representing spectra with reduced absorption. The existence of both SOM topological clusters demonstrates how the SOM can capture subtle internal variation in high-dimensional data. Achieving a fully automated delineation will likely require more discriminating summary products, as with the current set, neuron 2454 correlates almost identically with neurons 2460 and 2463 when referenced against the illite spectrum from the MRO CRISM Type Spectra Library.

Figure 8.

Reference to clusters shown in Figure 7. The SOM grid contains 2500 neurons. In this rotated 3D orientation, neuron [0, 0] is at the left-hand corner, [50, 50] at the right-hand corner, [50, 0] at the top apex, and [0, 50] at the bottom apex. (a) Neuron weight values for , with both clusters showing a distinct spike—their separation indicates additional high-dimensional differences. (b) Neuron weight values for , where cluster 0 shows elevated absorption, while clusters 1 and 2 are more subdued and not directly visible from this view, leading the SOM to topologically separate them.

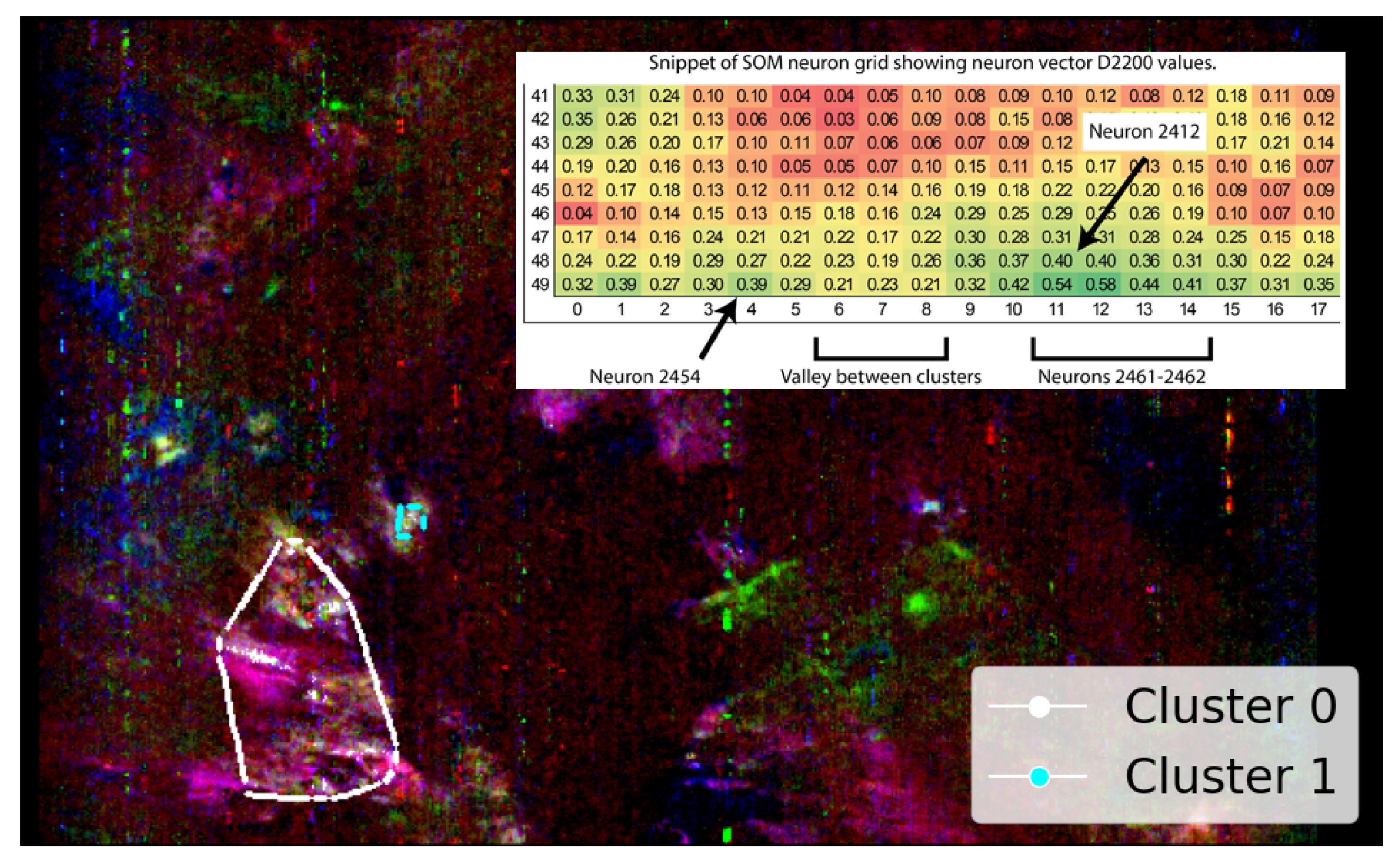

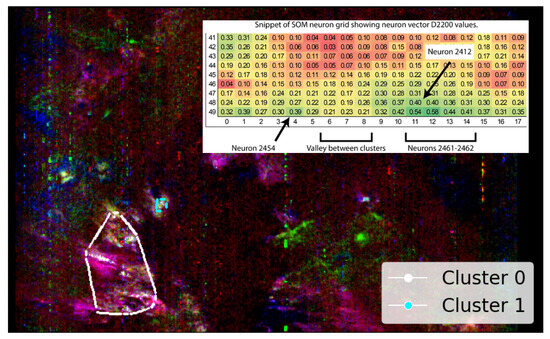

Using SOM output in this semi-automated approach, neurons 2412 and 2461–2464 are identified as best representing the high-quality pixels within the SOM topological cluster containing verified illite. Although neuron 2412 introduces a separate spatial distribution cluster (cluster 1 in Figure 9), it is topologically connected to the main group and, thus, likely represents illite, albeit with slightly more mixed spectra. The topological connection of neuron 2412 is illustrated in Figure 9 by the included snippet, which shows the pixels mapped by these neurons and how the cluster appears on the SOM-derived two-dimensional grid for .

Figure 9.

SOM-driven semi-automated selection of neurons 2412 and 2461–2464, representing the SOM-identified topological cluster containing a pixel verified as illite. White pixels indicate individual pixels clustered by these neurons. The snippet shows the SOM neuron grid with absorption, highlighting a separation between neuron 2454 and the neighbouring cluster of neurons (2461–2464) with more elevated absorption. The snippet is positioned over an otherwise uninformative area of the image as per previous images. This image is rotated 180 degrees to align with Image D from Figure A3 and has a resolution of 390 × 640 pixels, with the x-axis oriented vertically to align with the image rows.

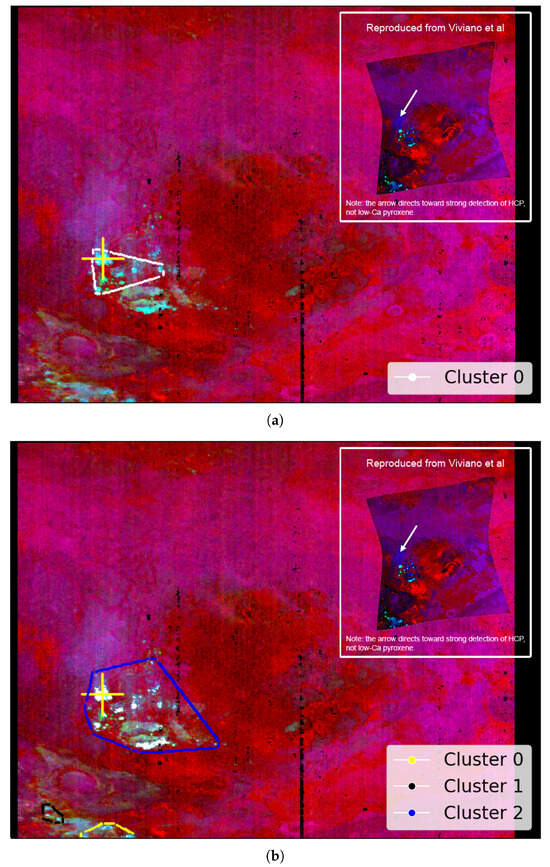

Table 1 in Viviano et al. [14] identifies low-Ca pyroxene as present at the coordinate location [174, 528] within a 9 × 9 pixel area in target region FRT000064D9. This location appears to visually align with the cyan regions in Image H from Figure A2, offering an additional opportunity to evaluate the SOM model’s ability to identify the spatial distribution of a mineral. Although this region is not explicitly labelled in Image H from Figure A2, its association with low-Ca pyroxene is visually supported by the coordinate reference and Martian surface features. We note that Figure A2 is map-projected, while the coordinate reference is not.

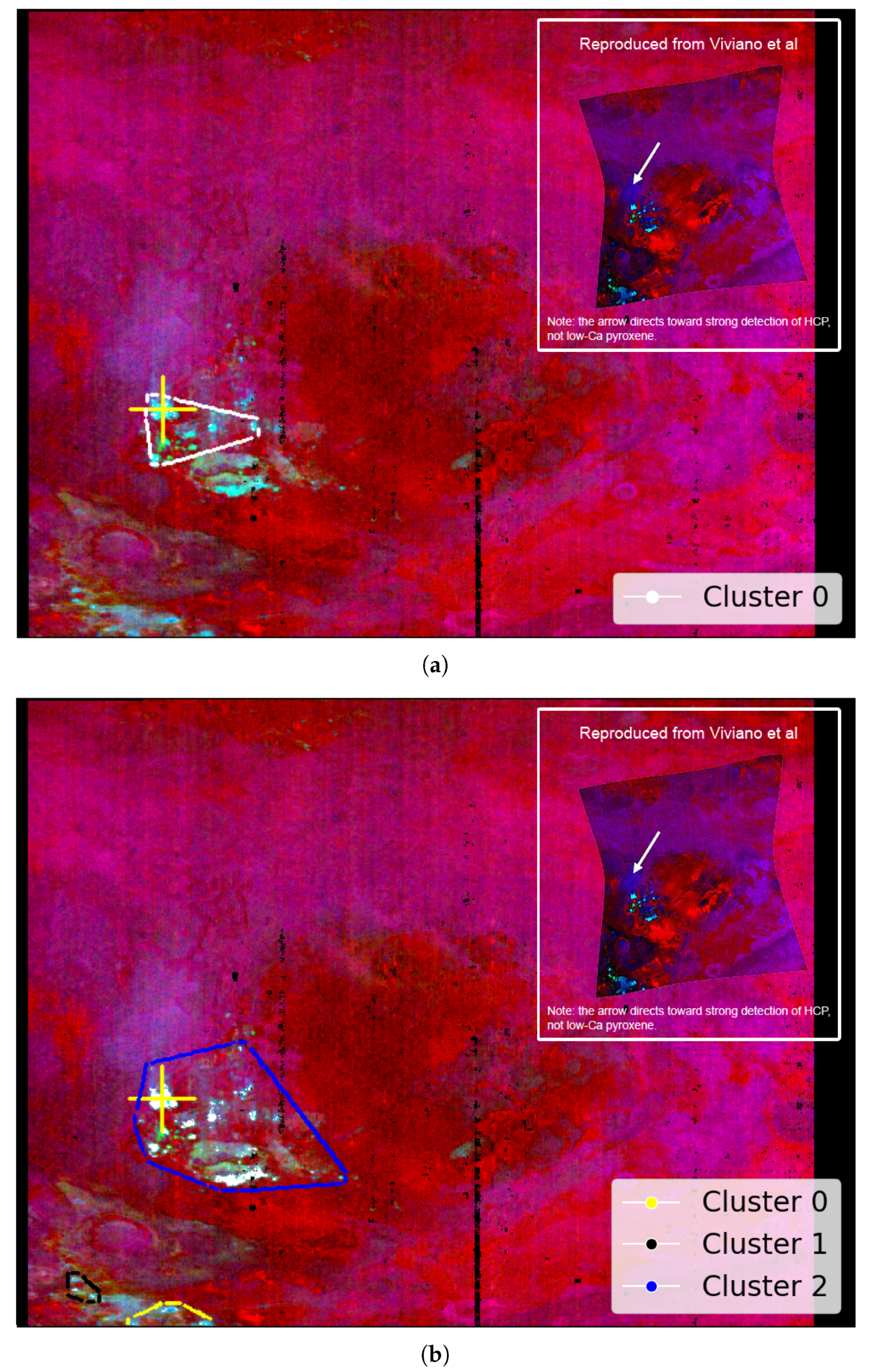

Figure 10a shows the region identified by the SOM model, overlaid with our replication of Image H from Figure A2. The highlighted area corresponds to the top five neurons most strongly correlated with the processed MRO CRISM Type Spectra Library sample for low-Ca pyroxene.

Figure 10.

We use image data from Viviano et al. [14] as a source of ground truth for comparison with outputs derived from the SOM model. For ease of comparison, a snapshot of the referenced image is shown in the top-right corner of the corresponding panel, with a larger version provided in Appendix A. Readers are reminded of the limitations of these visual comparisons, as discussed in Section 3.1. (a) Overlay based on Image H of Figure A2, showing cyan areas of low-Ca pyroxene identified by the top five correlated neurons. The maximum pixel correlation in Cluster 0 is 0.87. (b) Overlay using the top fifty correlated neurons, where white pixels indicate those clustered by the neurons and underlying cyan areas indicate low-Ca pyroxene. Correlation values range from 0.81 to 0.87, with the latter in Cluster 2. Both images are unprojected, rotated 180 degrees to align with Image H from Figure A2, and have a resolution of 480 × 640 pixels, with the x-axis oriented vertically to match image rows.

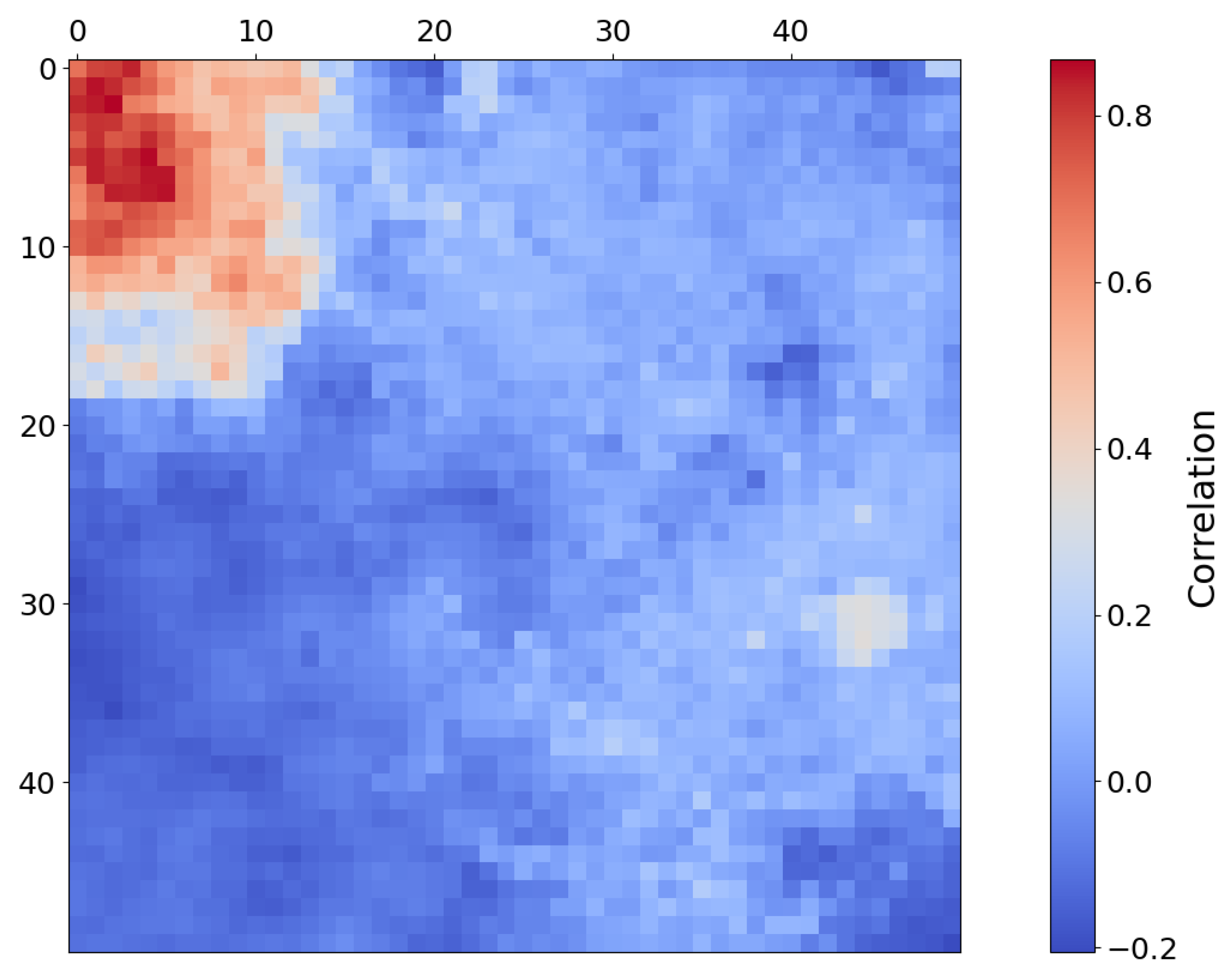

Although the SOM model correctly identifies the target region with the top five neurons, this is likely an example of over-dimensioning the SOM model. Regarding Figure 11, many neurons in the top left-hand corner of the SOM model are correlated with the mineral and, ideally, should be clustered to a smaller number of neurons. Figure 10b shows the identified spatial distribution of the top 50 neurons. Overall, the SOM model appears to effectively capture the spatial distribution of low-Ca pyroxene and topologically organises those pixels within the map.

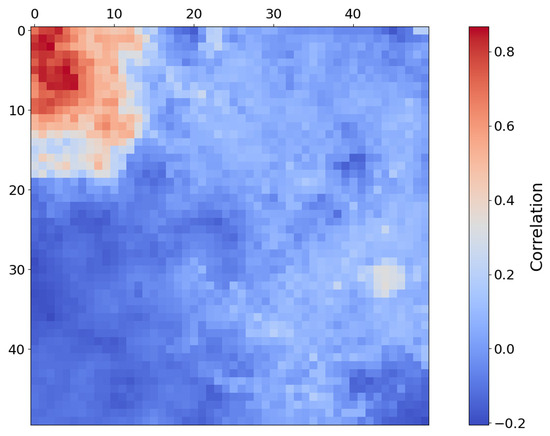

Figure 11.

Heat map of SOM neurons showing correlation with low-Ca pyroxene in region FRT000064D9 based on comparison with the MRO CRISM Type Spectra Library. Each pixel in this image corresponds to a neuron in the SOM model, starting with neuron 0 at the top-left corner [0, 0] and ending with neuron 2499 at the bottom-right corner [50, 50], comprising a total of 2500 neurons.

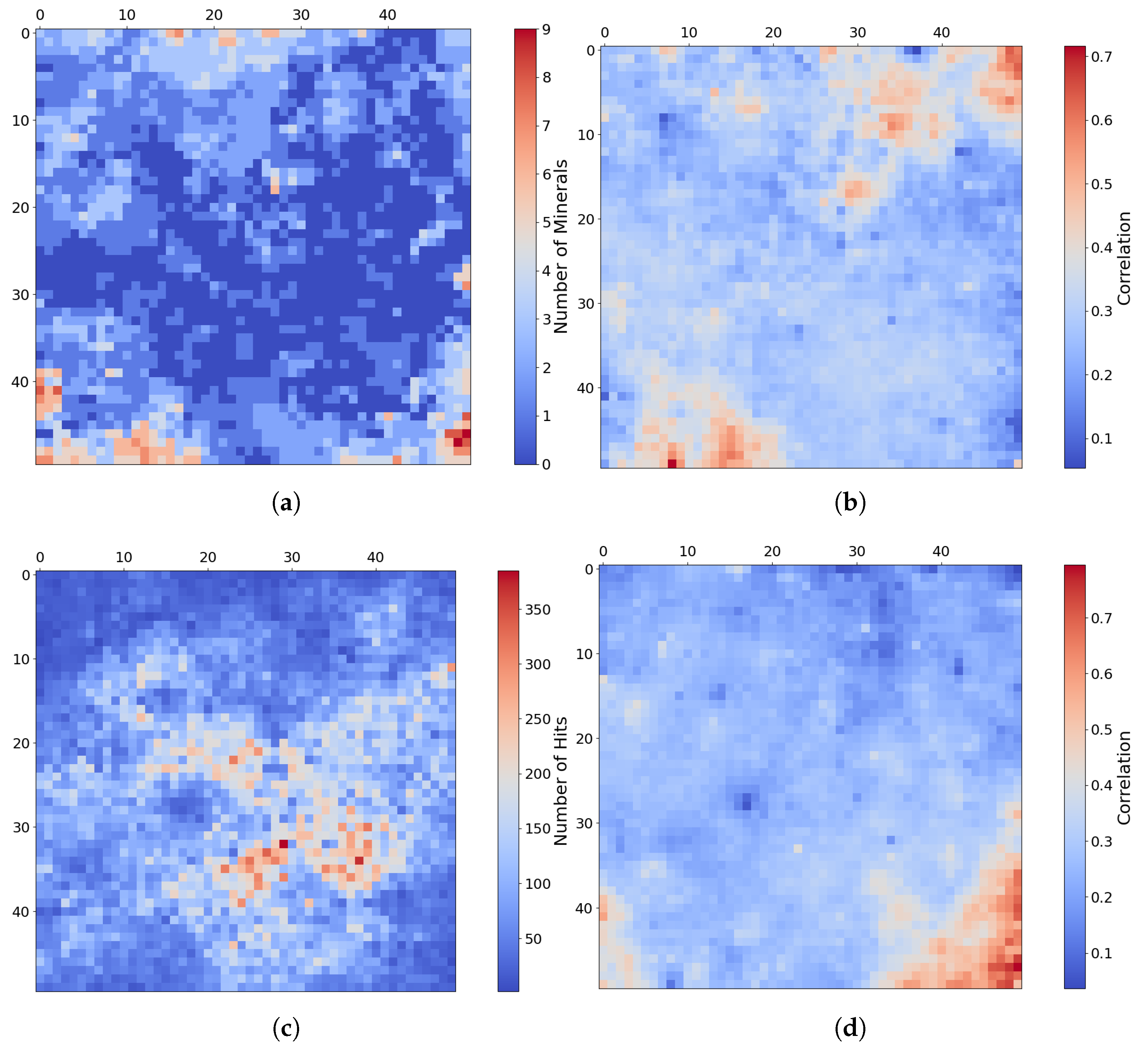

4.2. SOM Model Structure and Mineral Organization

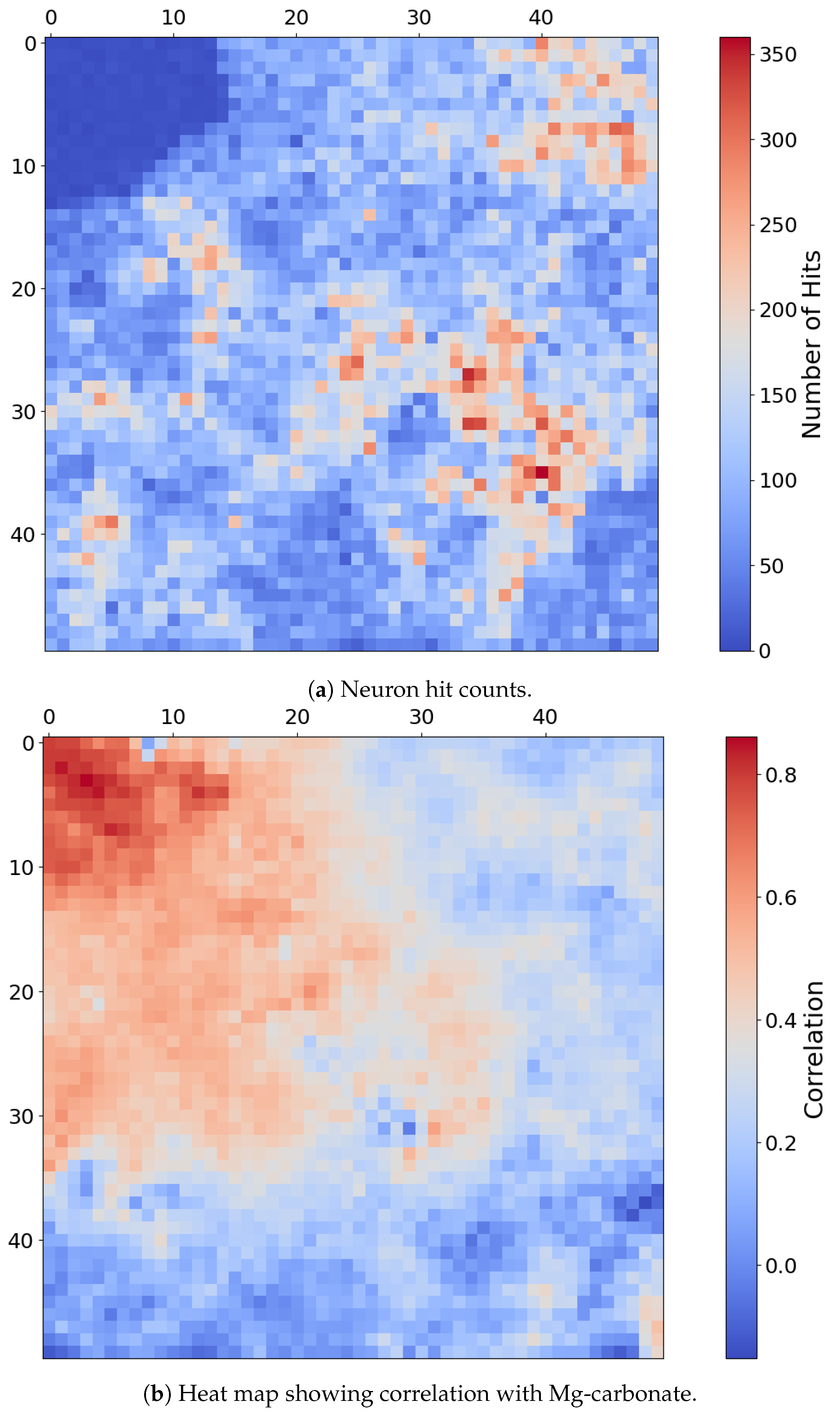

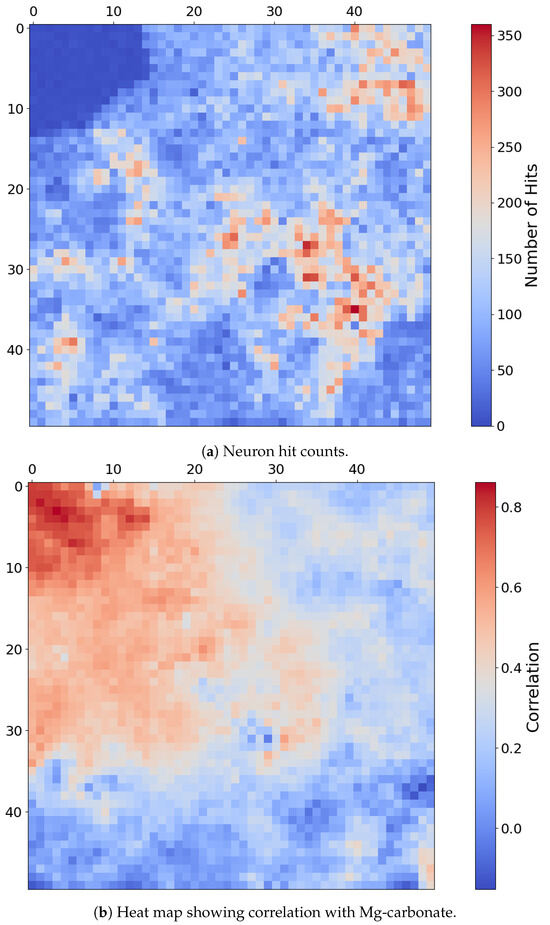

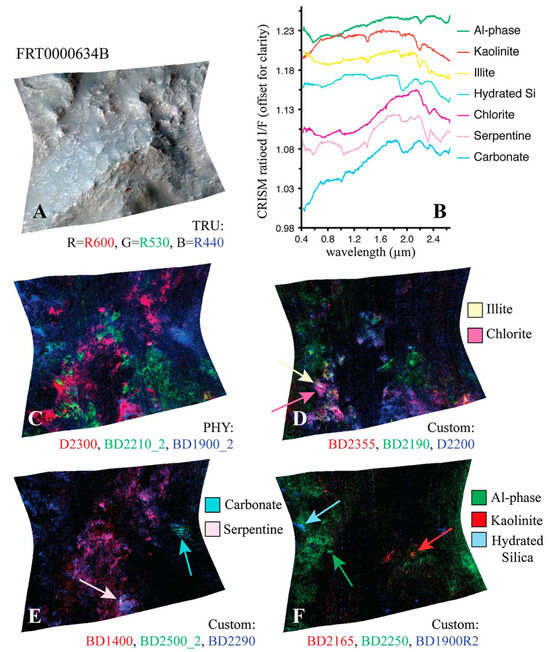

Fe-Olivine appears to be widespread in target region FRT00003E12, with a substantial majority of SOM neurons exhibiting a strong correlation with the mineral. Rather than assessing the correlation of each neuron with a particular mineral, Figure 12a considers the hit rate of each neuron; this reveals a very distinct topological cluster with a relatively low hit rate in the upper-left corner of the SOM.

Figure 12.

(a) Number of times each neuron was the BMU, with lower hit counts concentrated in the upper-left quadrant. (b) Heat map of SOM neurons showing correlation with Mg-carbonate based on comparison with the MRO CRISM Type Spectra Library. Neurons correlated with Mg-carbonate cluster in the top-left quadrant, whereas Fe-olivine would otherwise correlate to neurons in the top-right quadrant. Each pixel in these images corresponds to a neuron in the SOM model, numbered from neuron 0 at [0, 0] in the top left to neuron 2499 at [50, 50] in the bottom right, for a total of 2500 neurons.

The only mineral mapped to this distinct region is Mg-carbonate. While Mg-carbonate shares activity in OLINDEX3 and BD1300 with Fe-olivine, it additionally exhibits strong responsiveness to BD2290 and several other summary products to which Fe-olivine does not. This spectral distinction is echoed in the SOM structure, which topologically separates Mg-carbonate into a unique cluster of neurons, mirroring the spectral separation intentionally embedded into our overlay design. As shown in Figure 12b, the SOM clusters Mg-carbonate into the top-left quadrant and away from Fe-olivine, which would otherwise correlate to neurons in the top-right quadrant.

The extended moderate neuron correlation with Mg-carbonate in Figure 12b is likely due to the extensive presence of Fe-olivine in target region FRT00003E12, as Mg-carbonate responds to many of the same summary products as Fe-olivine. Figure 13 presents the CR2 overlay to demonstrate the isolated nature of Mg-carbonate in this region, following the approach suggested by Viviano et al. [14] in Figure A1, which proposes this RGB overlay to distinguishing carbonate minerals. This overlay uses the summary products (MIN2295_2480 and MIN2345_2537) and CINDEX2 as RGB components, highlighting Mg-carbonate in areas clearly distinct from the widespread Fe-olivine. Prior to our study, we were unaware of any previous identification of Mg-carbonate at this location and were guided to its presence via the topological relationships preserved by the SOM model. We found that the mineral had, indeed, been previously reported at this site, and the SOM model correctly delineated its known distribution. Table 1 from Viviano et al. [14] identifies Mg-carbonate as present at the coordinate location [103, 136] within a 5 × 5 pixel area in target region FRT00003E12.

Figure 13.

Unprojected map view of FRT00003E12 using the recommended CR2 overlay, highlighting potentially Mg-carbonate-rich areas. Unlike other images, no individual pixels are marked in this overlay. The yellow regions are a direct result of the overlay and represent isolated and distinct mineral clustering in this area. The SOM-delineated regions were generated by selecting the top 15 neurons—those with a correlation with the reference spectra exceeding 0.8, i.e., the highest correlating neurons located in the top-left corner of the neuron heat map.

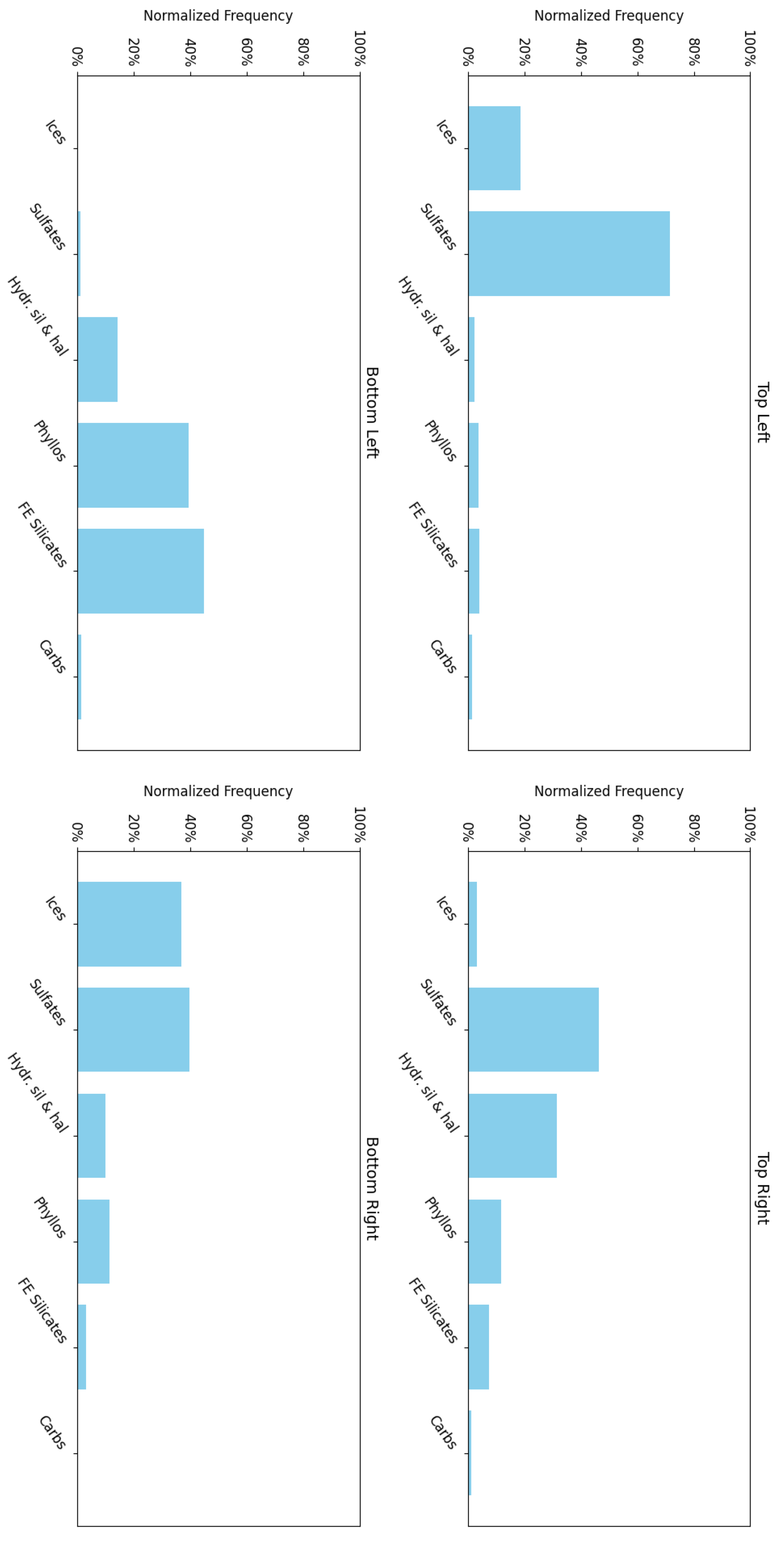

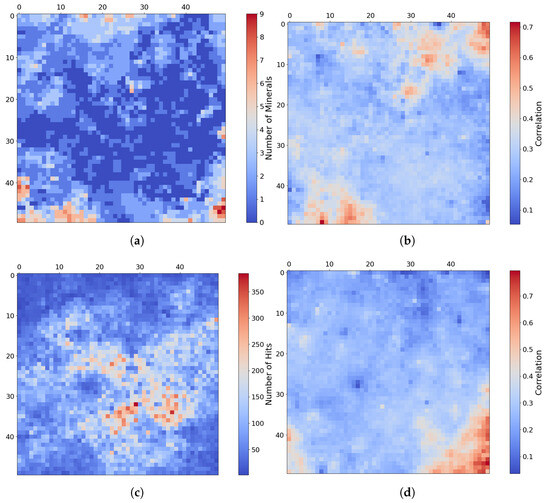

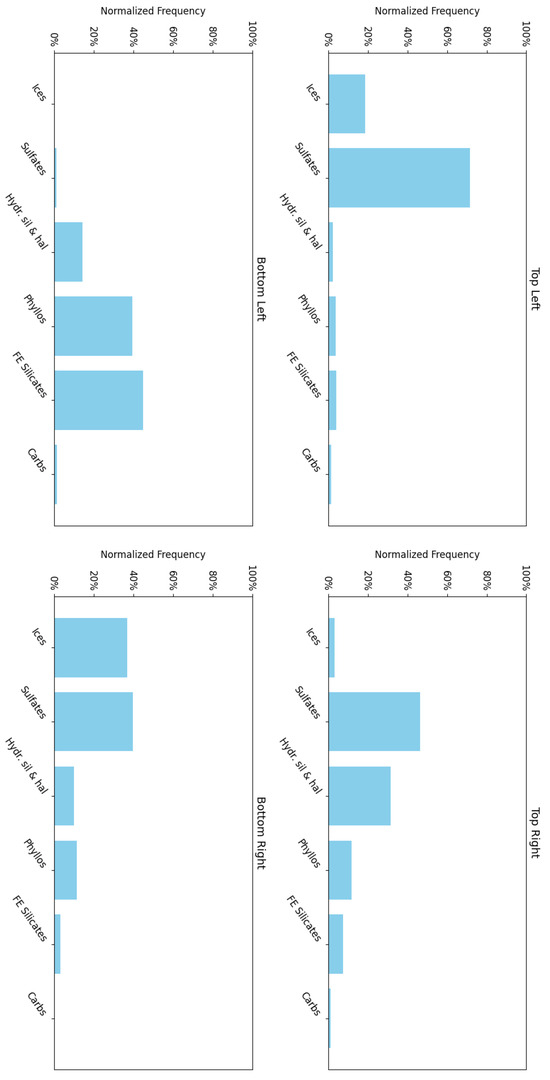

Similar to the pattern identified in the paragrpah “Implications for Mineral Analysis” of Section 2.3.2, Figure 14a shows the inferred distribution of minerals mapped for target region FRT0000634B, where each neuron follows the application of our thresholding criterion based on correlation strength and z-score. A distinct pattern is revealed in which minerals localise around the corners and edges of the SOM model.

Figure 14.

Mineral mapping, correlation, and hit rate for each neuron in target region FRT0000634B. Each pixel in these images corresponds to a neuron in the SOM model, starting with neuron 0 at the top-left corner [0, 0] and ending with neuron 2499 at the bottom-right corner [50, 50], comprising a total of 2500 neurons. (a) The number of minerals mapped to each neuron. Neurons with multiple mapped minerals suggest a high degree of feature correlation among their mineral groups. (b) Neuron correlation with Al-smectite. (c) The number of times each neuron was identified as the BMU. The SOM model appears to cluster uninformative neurons near the centre of the map, where we observe the highest hit counts. (d) Neuron correlation with talc.

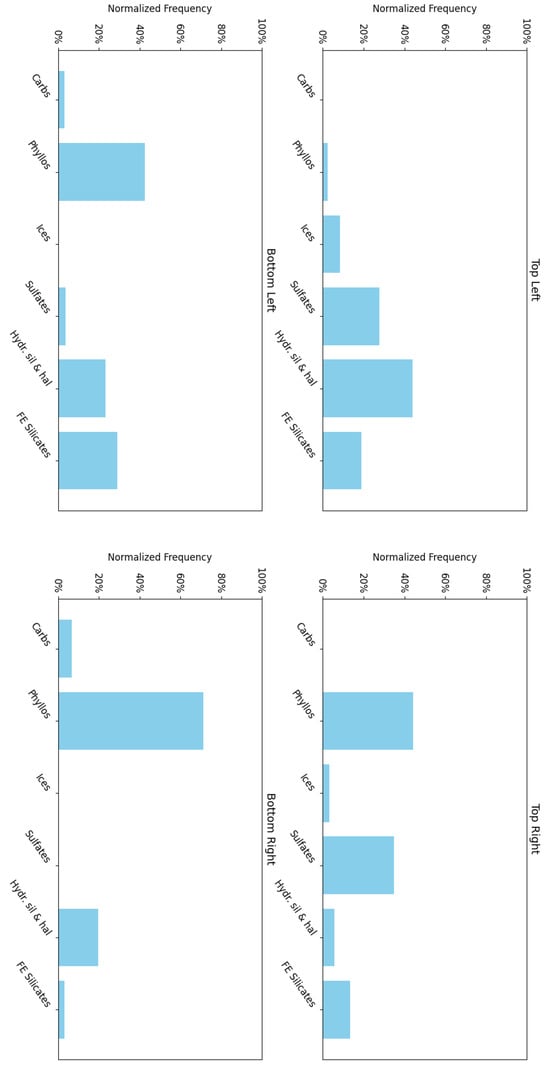

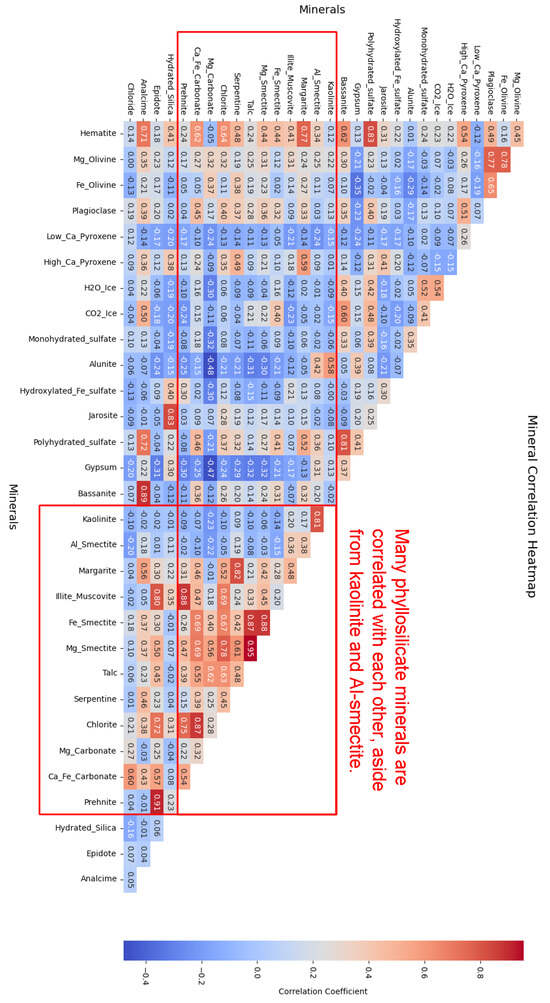

Figure 15 shows the frequency with which each mineral group is associated with neurons in the four corners of the SOM model, revealing a hierarchical pattern in the clustering. Note: ice is not present in this region; however, ice-related summary products are highly correlated with other minerals (e.g., bassanite and others). As a result, neurons representing these minerals or mixed spectra may also appear to be correlated with ices. This reflects the limitations of the utilised summary products, where collinearity persists (see Section 3.2).

- 1.

- The top-left corner of Figure 15 is notably sparse in phyllosilicate minerals, which are primarily mapped to neurons in opposing corners.

- 2.

- Sulfates and ices (the latter represented by only two instances in the MRO CRISM Type Spectra Library) are more prevalent in the upper regions of the SOM model, with ices absent from the bottom corners.

Figure 15.

An analysis of the mineral categories associated with the neurons located at each corner of the SOM model for target area FRT0000634B.

Figure 15.

An analysis of the mineral categories associated with the neurons located at each corner of the SOM model for target area FRT0000634B.

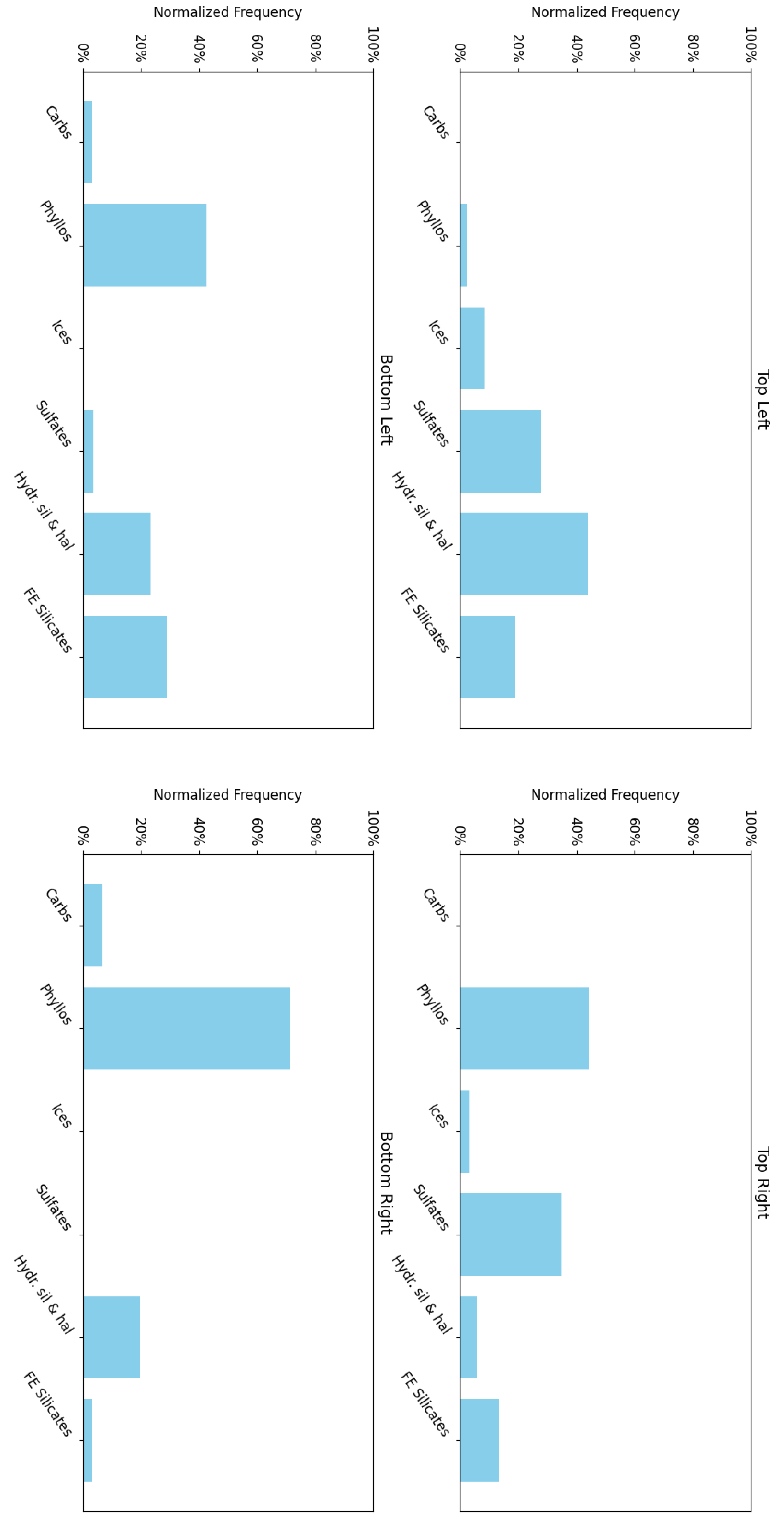

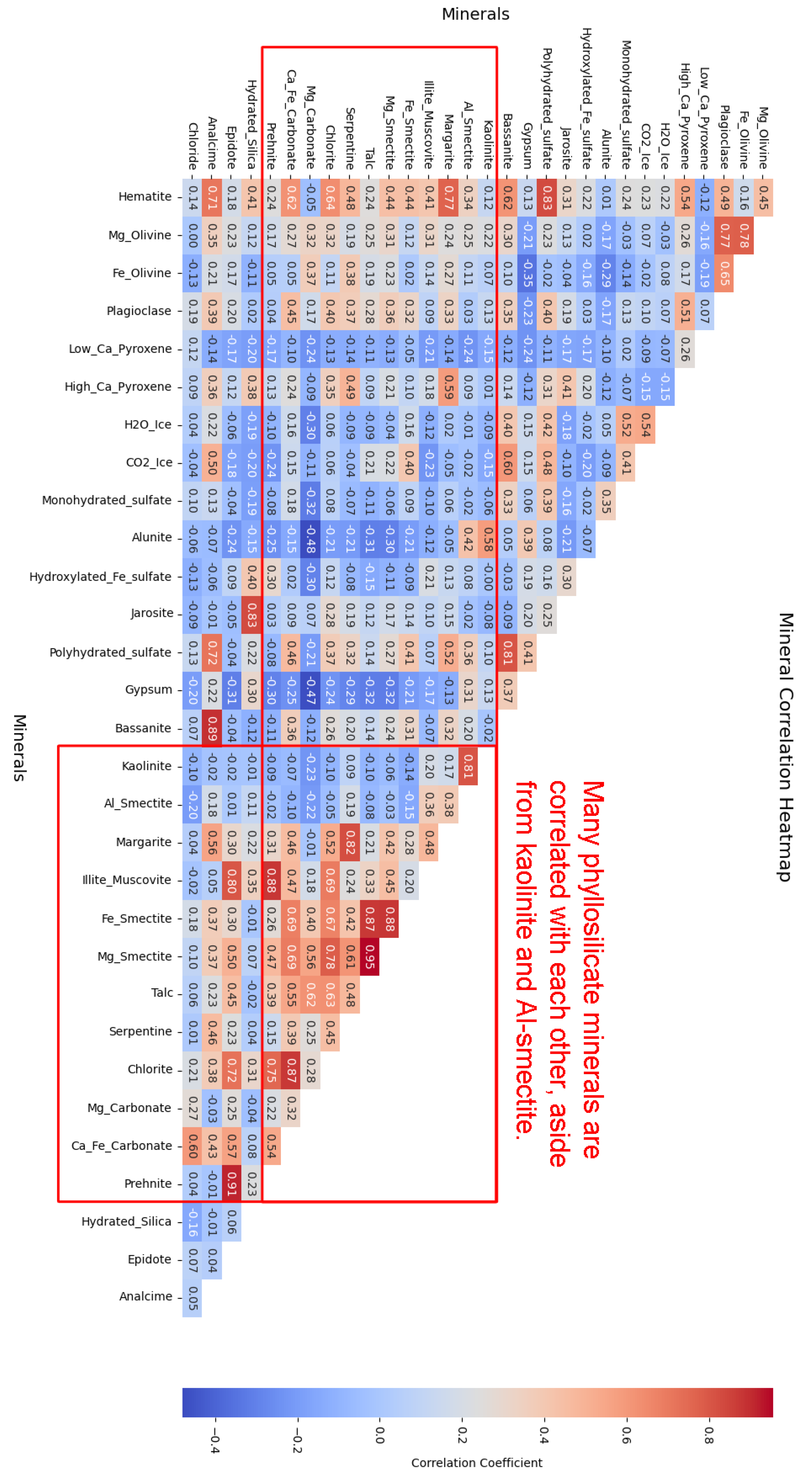

We examine a correlation heat map of the minerals from the processed MRO CRISM Type Spectra Library to better understand the structure and organisation (refer to Figure 16) and note a pattern similar to that of the SOM model:

- 1.

- Phyllosilicates exhibit high intra-group correlation, except for kaolinite and Al-smectite, which are mostly negatively correlated with their peers.

- 2.

- Both H2O and CO2 ices are correlated with many sulfates, plus a few other minerals for CO2 ice.

Figure 16.

Correlation heatmap of processed MRO Library minerals.

Figure 16.

Correlation heatmap of processed MRO Library minerals.

As phyllosilicates are highly correlated (which is why some neurons are mapped to multiple minerals), neurons activated by these minerals tend to draw in neighbouring neurons, causing the phyllosilicates to cluster together. This clustering occurs throughout the SOM model, except in the top-left corner, where phyllosilicates are sparse (Figure 15). Similarly, the SOM model appears to group ices and sulfates along the top of the map. Refer to Section 2.3.2 for an illustrative example of the patterns preserved by the SOM model’s competitive learning process.

Further examination reveals that kaolinite and Al-smectite are negatively correlated with their group. The SOM model topologically separates spectra correlated with these minerals into the top-right and bottom-left corners of the grid (Figure 14b), away from spectra correlated with other phyllosilicates, such as talc, which cluster in the bottom-right corner (Figure 14d). Without the negatively correlated kaolinite and Al-smectite, the entire upper region of the SOM would likely be free of spectra that correlate with phyllosilicates. This separation highlights the model’s ability to align with inherent patterns in the data. Importantly, when attempting to identify an unknown mineral, such a topological structure may provide clues about the mineral group to which the unknown mineral belongs.

We also examined the frequency with which neurons were activated and noticed an inverse relationship between the neurons that likely represent a mineral (Figure 14a) and those that receive the most hits (Figure 14c). This may indicate that many pixels contain mixed data, making it difficult to reliably identify anything unique. We believe this is an important observation and a key reason for selecting samples from k-means clustered data when training the SOM model as described. By doing so, we can better represent groups (with few instances) that are likely to contain minerals, as opposed to the majority of instances, which appear to be uninformative and potentially redundant.

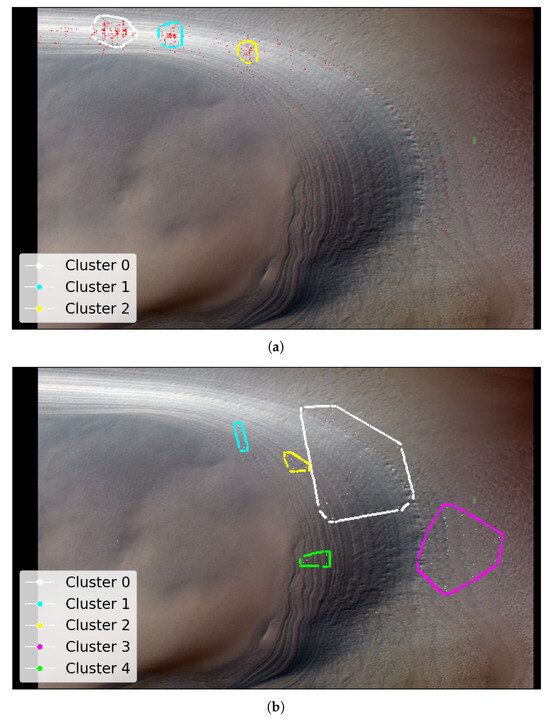

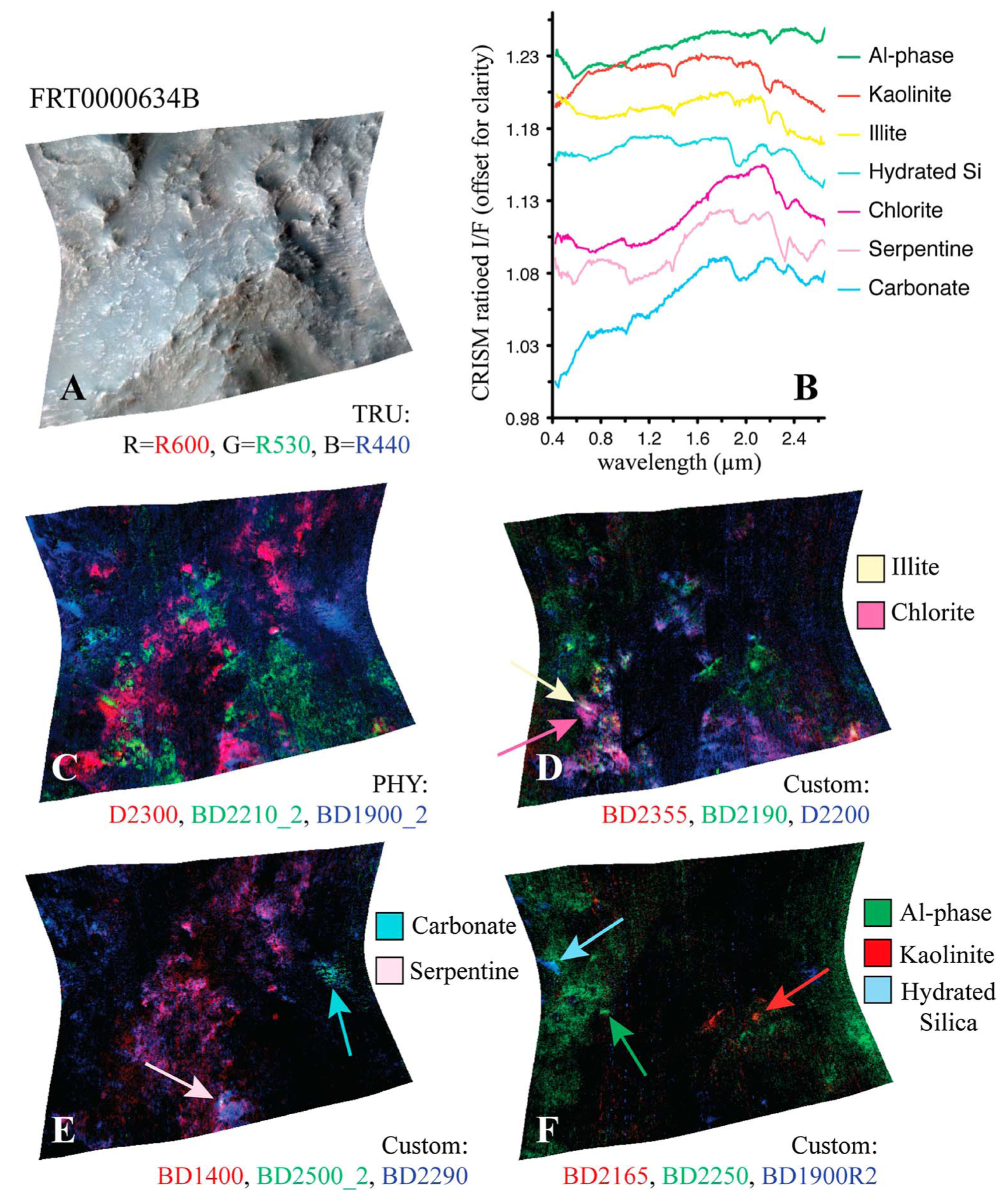

Moving Beyond RGB Overlays and into High-Dimensional Clustering

The SOM compresses high-dimensional hyperspectral data onto a two-dimensional grid, preserving multi-dimensional spectral patterns and revealing clusters of distinct spectra. We illustrate this with an example target region FRT00007375 to demonstrate the SOM’s ability to delineate mineral distributions beyond conventional RGB visualisations, which are inherently limited in capturing patterns within the full high-dimensional input space. This region was selected at random from the TER catalogue, without prior knowledge of its location or mineralogy.

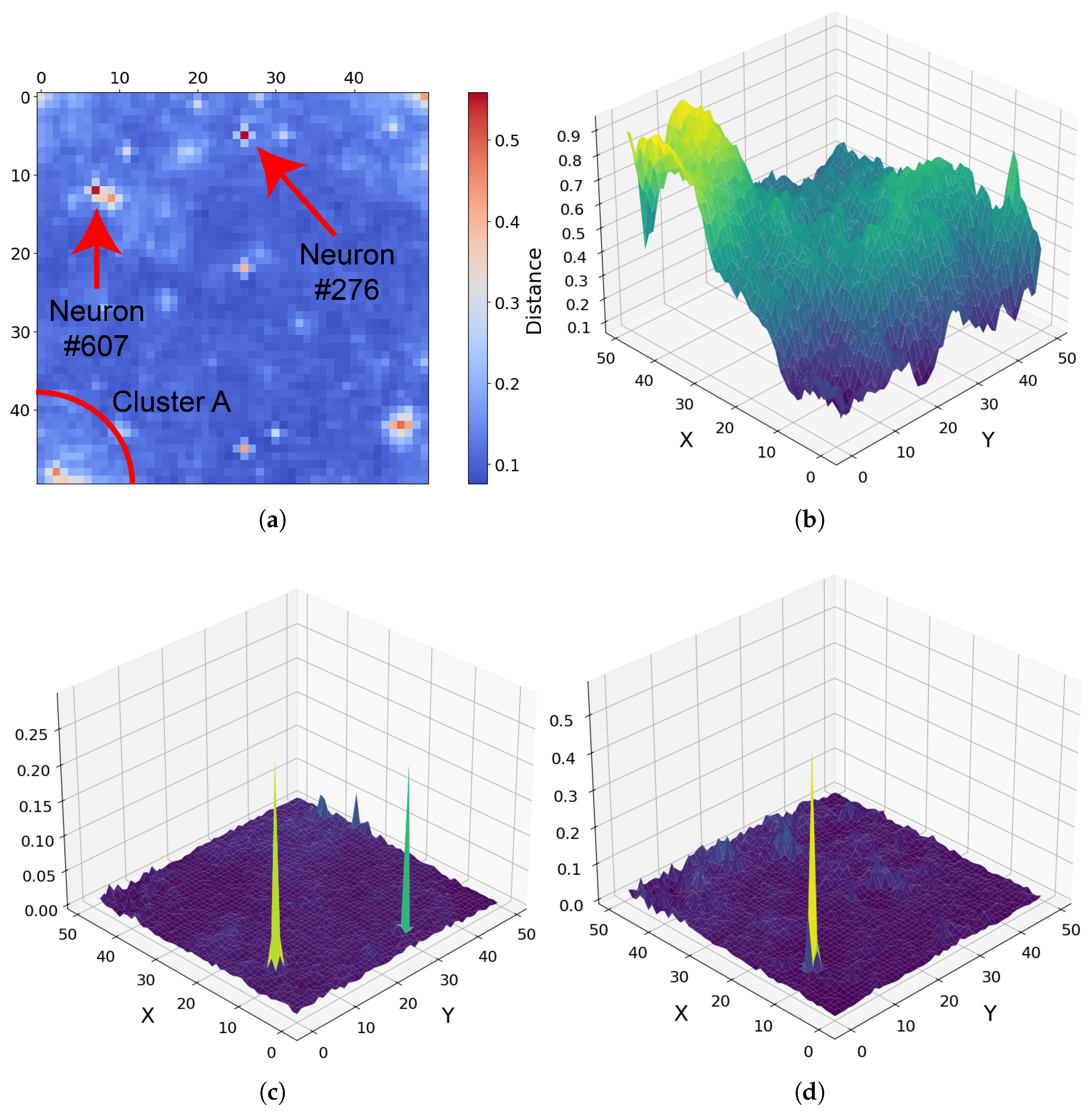

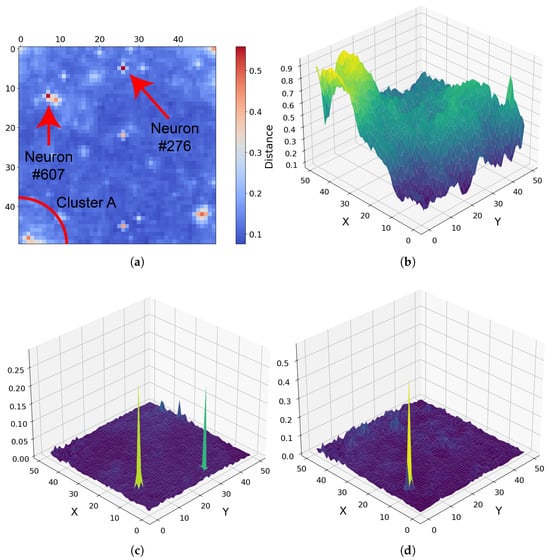

For target region FRT00007375, the U-Matrix derived from the SOM output highlights unique spectral behaviour associated with pixels clustered by neurons 276 and 607, as annotated in Figure 17a. The U-Matrix captures differences between neighbouring neurons, with bright regions marking transitions between distinct spectral groups, allowing areas of unique spectra in the high-dimensional data to be identified at a glance. Although neurons 276 and 607 occupy different locations on the SOM grid, they share strong similarities across most summary products, including a pronounced spike in BD2230 (Figure 17c).

Figure 17.

Orientation note: In panels (b–d), the X-axis corresponds to the vertical axis and the Y-axis to the horizontal axis in panel (a). (a) SOM U-Matrix for target region FRT00007375 with annotated neurons. Each pixel represents a neuron in the 50 × 50 grid, numbered from 0 at the top left [0, 0] to 2499 at the bottom right [50, 50]. (b) R3920 reflectance across the SOM grid. (c) BD2230 reflectance, showing spikes for both neurons 276 and 607. (d) BD2265 reflectance, where only neuron 276 exhibits a strong absorption feature.

Due to the persistent spectral similarities, pixels corresponding to these neurons would appear nearly identical in a standard RGB overlay, as only a single dimension of the 29-feature space captures a meaningful difference. The SOM, however, separates them clearly—neuron 276 exhibits a BD2265 spike, whereas neuron 607 does not. Their positions on the SOM grid illustrate the preservation of high-dimensional patterns—for example, a region in the top right of the SOM (bottom left of Figure 17b) shows low R3920 reflectance, rising toward the grid centre.

These neurons had to be separated but only in locations consistent with other multi-dimensional factors. The underlying pixels are clustered by neurons that retain their similar R3920 values (0.36883 and 0.255), with the neurons positioned along a contour in the two-dimensional neuron grid consistent with these R3920 values. In this way, the SOM preserves both local spectral differences and broader pattern continuity. Although the BD2230 and BD2265 spikes may be artefacts, this example demonstrates the SOM’s ability to capture fine-scale high-dimensional variations while maintaining overall spectral relationships.

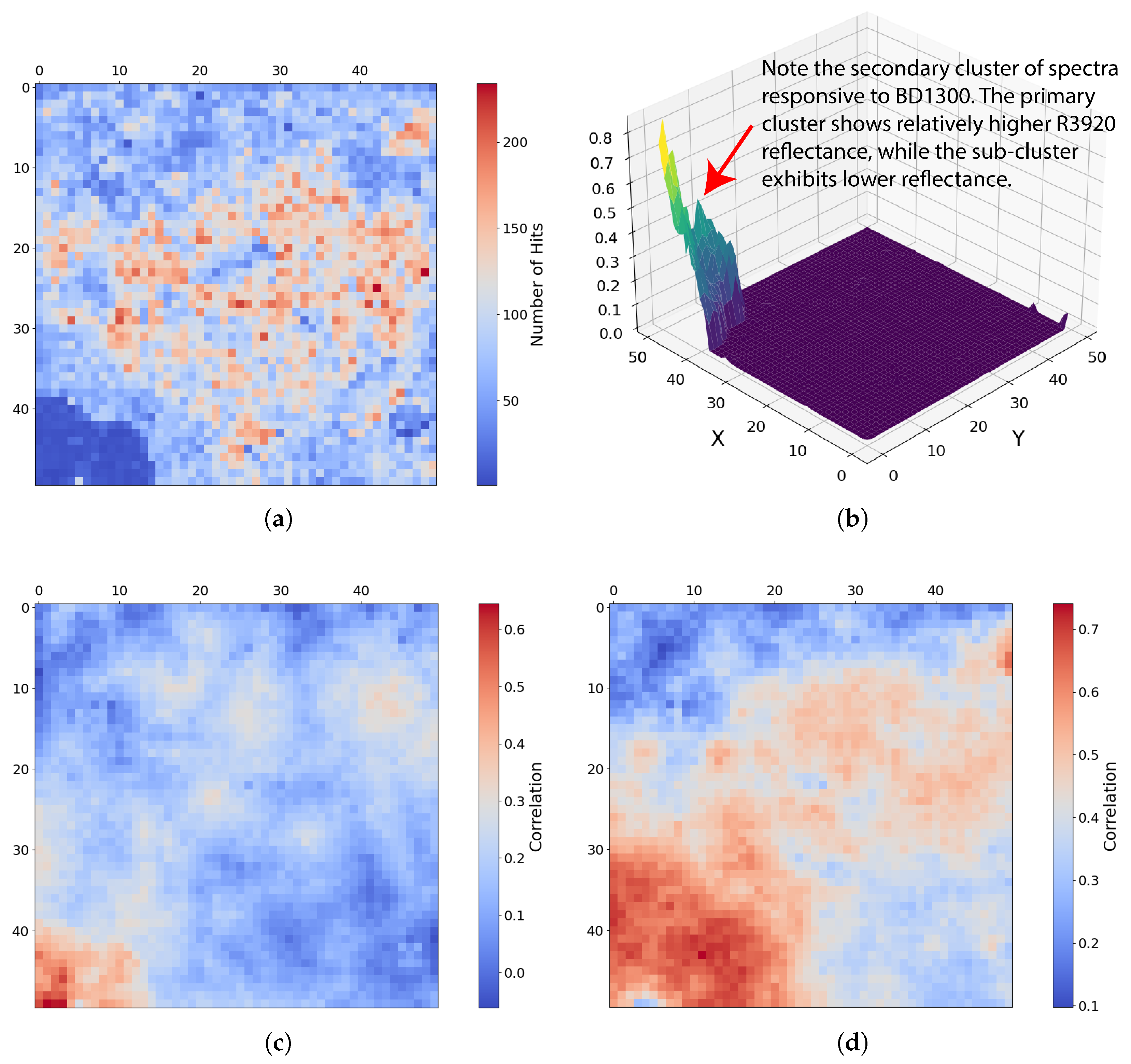

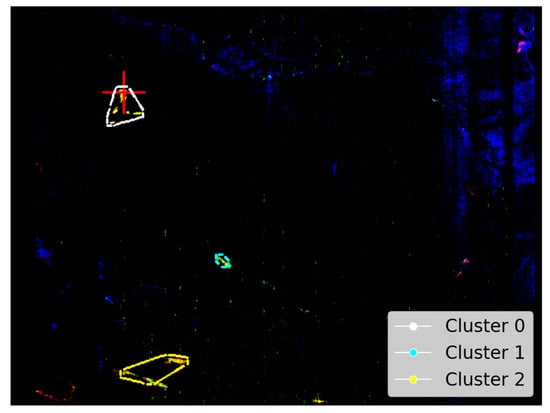

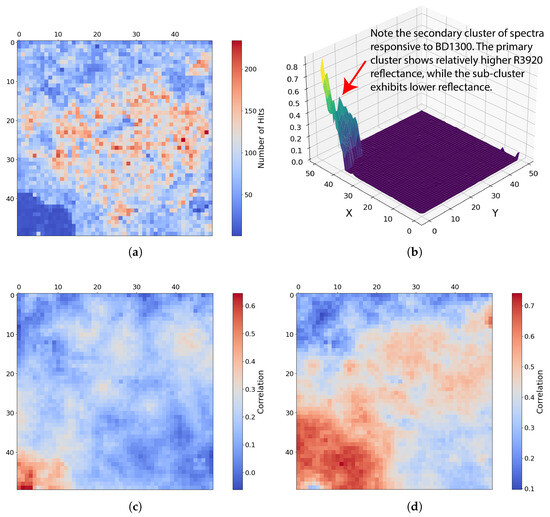

Many of the spectra in this region are broadly similar, with strong associations with summary products linked to bassanite and analcime (persistent OLINDEX3 and BD1900R2 and consistently elevated SINDEX2, among others). Because the SOM employs competitive learning, unique spectra are positioned toward the edges and corners of the map (refer to Section 2.3.2), separating them from common patterns. Consequently, cluster A in Figure 17a stands out. This cluster is more distinct than the U-Matrix alone, which suggests that the SOM allocated many neurons to separate this group (Figure 18a), producing gradual transitions between neighbouring neurons. The bottom-left panel of Figure 19 shows that this cluster captures Fe-silicate and/or phyllosilicate spectra, separated from sulphates, further underscoring its significance.

Figure 18.

SOM outputs for target region FRT00007375. (a) Neuron hit rate, showing how often each neuron was identified as the BMU, with many neurons allocated to unique spectra in the bottom-left corner. (b) Rotated 3D view of the same SOM grid to emphasise BD1300 responses; the dense cluster corresponds to the bottom-left corner of panel (a). (c) Neuron correlation with Fe-olivine, aligning closely with the low-hit-rate cluster in panel (a). (d) Neuron correlation with margarite, showing a more diffuse correlation than for Fe-olivine. Panels (a,c,d) show the SOM 50 × 50 neuron grid.

Figure 19.

Mineral categories associated with the neurons located at each corner of the SOM model for target region FRT00007375. Unlike other corners, sulphate-like spectra are lacking, whereas Fe-silicate and phyllosilicate spectra are more abundant.

Under local scaling, the high-dimensional patterns in the bottom-left corner of the SOM grid (Figure 17a) are characterised by generally high R3920 reflectance, except for a small sub-cluster with much lower values (visible as the dip in the top right of Figure 17b). This zone also exhibits BD1400 absorption, moderate BD1435 absorption, and low BD2235 absorption. Many of these features correspond to margarite (Figure 18d) and serpentine, particularly the elevated R3920 reflectance. The defining characteristic, however, is the presence of spectra with BD1300 absorption, confined strictly to this zone (Figure 18b). Notably, both Mg-olivine and Fe-olivine correlate strongly with neurons in this cluster (Figure 17c), although the distinct dip in R3920 within one sub-cluster warrants further investigation beyond the scope of this work.

In a semi-automated workflow, an analyst would be immediately drawn to the sub-cluster of lower R3920 reflectance in this region, as the U-Matrix in Figure 17a clearly highlights distinct changes in neuron weights slightly left of the bottom-left corner. Meanwhile, other SOM-derived analytics, such as those shown in Figure 18a–c, indicate that these neurons belong to a larger, coherent cluster, illustrating how the combination of topological and spatial analyses enhances the interpretability of high-dimensional spectral data.

Figure 20 shows the pixels most strongly represented by this cluster—specifically, neurons exceeding the 97.5th percentile of BD1300 values. We also highlight the subset associated with strong BD1300 but reduced R3920 reflectance by displaying pixels clustered by neurons 2404, 2405, and 2453–2456. These pixels occupy different locations yet appear consistent with the topography—clusters with higher R3920 reflectance are more concentrated and predominantly located in the fissuresof the northern terraces (relative to the image), whereas pixels with lower R3920 reflectance appear to wrap around the bluff and appear more concentrated in isolated depressions within the terraces. While we do not have the expertise to confirm this, it is plausible that the mineral may have weathered away from the concentrated regions with higher R3920 reflectance over time. Pixel coordinates from the described topological patterns for further investigation including the following:

- Higher R3920 reflectance values (selected at random, aside from trying to select a pixel from each cluster):

- –

- Neuron 2350: [19, 112] (cluster 0), [29, 181] (cluster 1)

- –

- Neuron 2450: [32, 196] (cluster 1), [35, 134] (cluster 0)

- –

- Neuron 2458: [52, 287] (cluster 3), [61, 288] (cluster 3);

- Lower R3920 reflectance values (refer to Figure 20b—no pixels were selectively chosen from clusters as the clusters are drawn solely to highlight the locations of identified pixels, not density):

- –

- Neuron 2453: [100, 439], [227, 380]

- –

- Neuron 2455: [125, 557], [190, 566].

Figure 20.

Unprojected map views of FRT00007375 showing pixels identified by the SOM. (a) Pixels associated with neurons exceeding the 97.5th percentile of BD1300 values, with density-based clusters suggesting concentrated pixels of this spectral feature, along with other high-dimensional patterns, the SOM has clustered with neurons in this region of the SOM model. (b) Delineated clusters highlighting individual pixels from a sub-cluster within the broader bottom-left cluster shown in Figure 18a, characterised by lower R3920 values—this is not intended as a spatial distribution map but to draw attention to the location of these individual pixels. Images are 390 × 640 pixels, with the x-axis oriented vertically to match image rows.

Figure 20.

Unprojected map views of FRT00007375 showing pixels identified by the SOM. (a) Pixels associated with neurons exceeding the 97.5th percentile of BD1300 values, with density-based clusters suggesting concentrated pixels of this spectral feature, along with other high-dimensional patterns, the SOM has clustered with neurons in this region of the SOM model. (b) Delineated clusters highlighting individual pixels from a sub-cluster within the broader bottom-left cluster shown in Figure 18a, characterised by lower R3920 values—this is not intended as a spatial distribution map but to draw attention to the location of these individual pixels. Images are 390 × 640 pixels, with the x-axis oriented vertically to match image rows.

This example illustrates how the SOM’s preservation of high-dimensional relationships within a two-dimensional projection can guide the identification of potential mineral groups and their spatial distribution. While this analysis cannot confirm the presence of specific minerals—requiring detailed mineralogical validation—it demonstrates that, under local scaling, the SOM identified a unique hyperspectral cluster within the target region. Recognising and preserving such clusters provides a powerful tool to guide subsequent mineral exploration.

In contrast, RGB overlays do not necessarily preserve multidimensional relationships unless directly captured by the three chosen components. In this region, for example, an MAF overlay (RGB composite using OLINDEX3, LCPINDEX2, and HCPINDEX2; see Figure A1) designed to visualise Fe-oxides and mafic silicate minerals (Figure 21) provides limited insight and fails to capture sub-patterns such as R3920 variations as presented here. The SOM, in contrast, preserves spectral relationships across the map, clearly delineating clusters of similar spectra and pointing toward areas for targeted investigation.

Figure 21.

Unprojected map view of FRT00007375 showing the MAF overlay, intended to highlight Fe-silicate regions (Figure A1). The overlay provides limited guidance compared to the SOM, which clearly identifies concentrated clusters of spectra potentially corresponding to Fe-oxides and mafic silicates (Figure 20). Image resolution is 390 × 640 pixels, with the x-axis oriented vertically to match image rows.

This capability underscores the potential of unsupervised machine learning to move beyond qualitative, visually driven methods for the mapping of mineral distributions, toward a quantitative, data-driven framework for automated planetary mineral exploration.

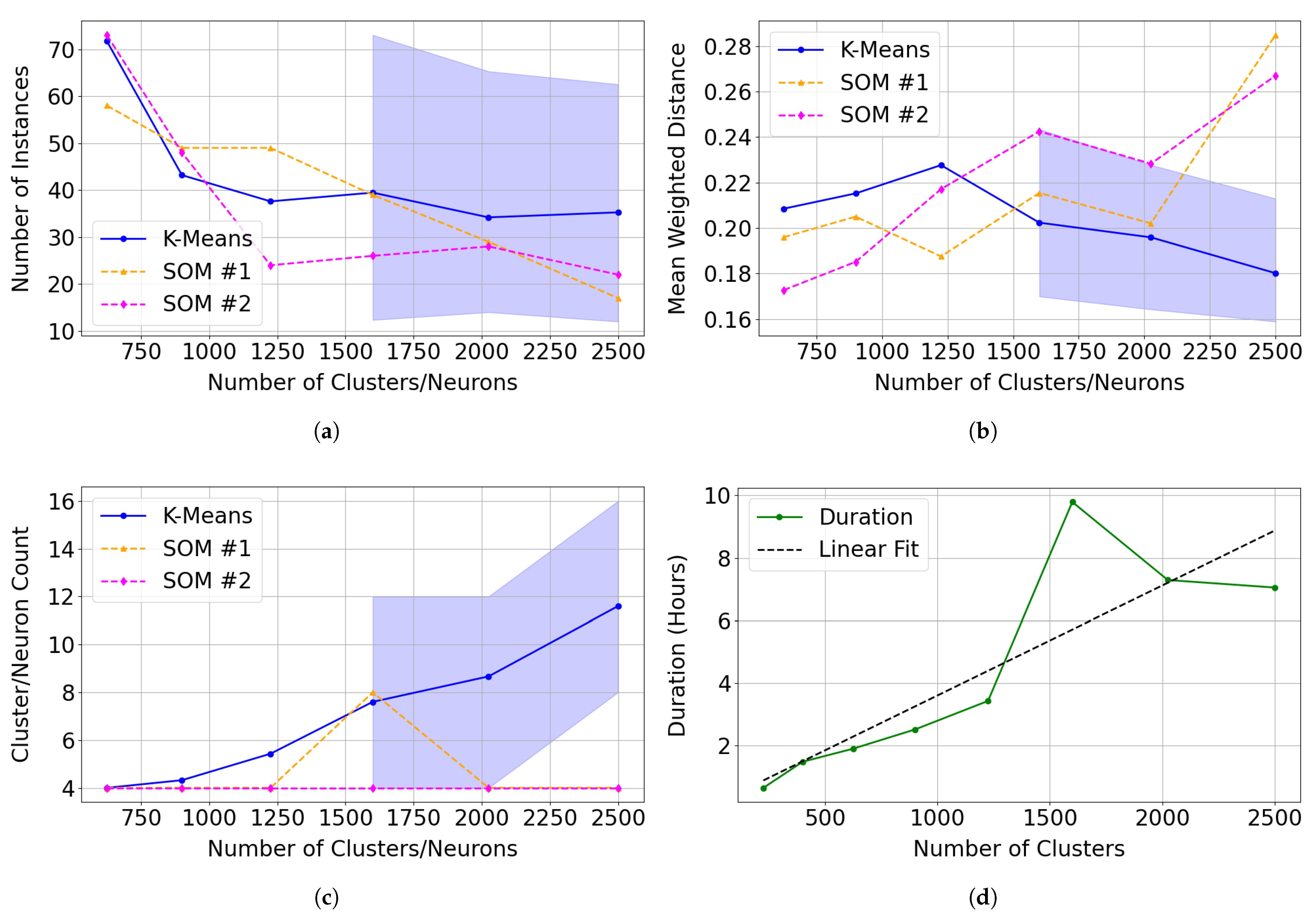

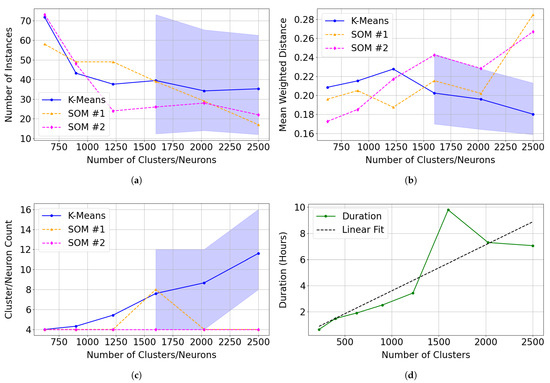

4.3. K-Means Clustering

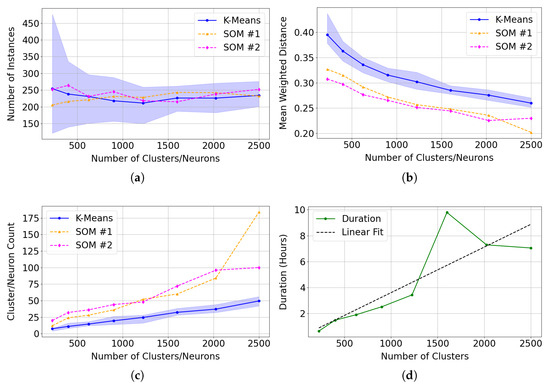

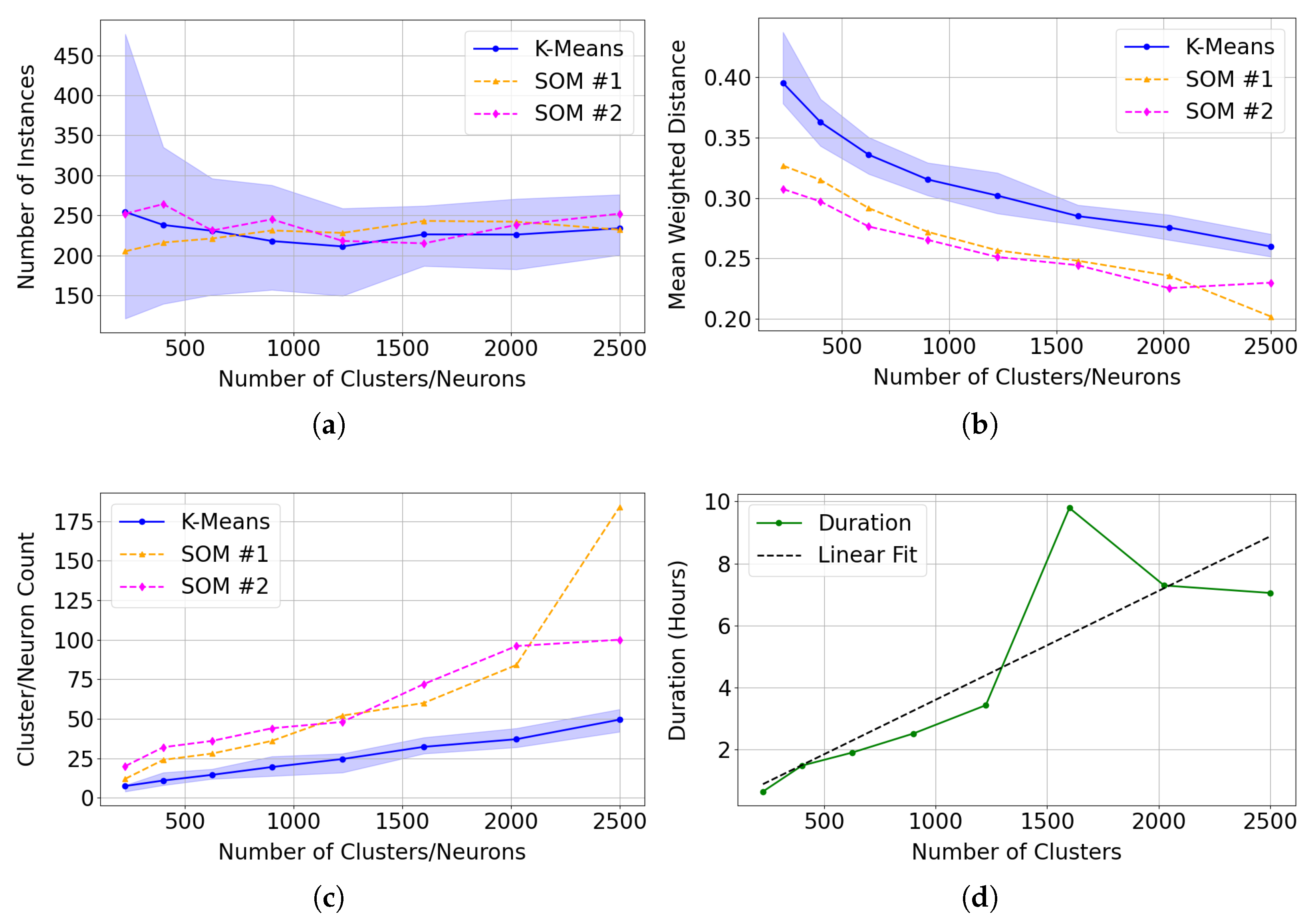

Compared to the SOM model, k-means clustering is significantly more efficient at clustering instances. However, k-means lacks the topological organisation capabilities of a SOM model—a feature that proved useful when identifying Mg-carbonate in target region FRT00003E12 and in capturing unique spectra in target region FRT00007375. In the latter case, the sub-cluster of spectra with lower R3920 reflectance would likely be separated into a distinct cluster under k-means, losing its relationship to the primary cluster. This topological structure enables neighbouring neurons to group similar instances and appears to result in a more focused and specialised clustering. Across various cluster/neuron sizes, the SOM model:

- 1.

- Demonstrates stable clustering of instances identified as Mg-carbonate, with both SOM training iterations appearing to show reduced variation in clustering assignments (notably, the SOM results remain close to the mean and well within the confidence interval generated from 30 independent k-means trials; see Figure 22a);

- 2.

- Generates tighter clusters, as indicated by a mean weighted distance that is consistently and significantly lower than that of k-means (see Figure 22b);

- 3.

- Allocates more neurons to represent distinct and unique instances, capturing greater detail (see Figure 22c).

Figure 22.

Comparison of clustering performance between 30 independent k-means trials and two SOM model series (SOM and SOM ) across varying cluster/neuron counts. We present the mean performance as solid lines, and the shaded confidence interval for k-means represents the 5th and 95th percentiles across the 30 trials. We calculate error metrics using only clusters or neurons with correlation values with the summary products derived from the Mg-carbonate spectrum in the MRO CRISM Type Spectra Library above 0.75. (a) Total number of instances assigned to clusters (K-Means) or neurons (SOM) identified as representing Mg-carbonate. (b) Mean weighted distance, indicating the compactness and cohesion of clusters (K-Means) or neurons (SOM). (c) Total number of clusters (K-Means) or neurons (SOM) matching Mg-carbonate across tested model sizes. (d) The execution time for SOM across tested model sizes.

Figure 22.

Comparison of clustering performance between 30 independent k-means trials and two SOM model series (SOM and SOM ) across varying cluster/neuron counts. We present the mean performance as solid lines, and the shaded confidence interval for k-means represents the 5th and 95th percentiles across the 30 trials. We calculate error metrics using only clusters or neurons with correlation values with the summary products derived from the Mg-carbonate spectrum in the MRO CRISM Type Spectra Library above 0.75. (a) Total number of instances assigned to clusters (K-Means) or neurons (SOM) identified as representing Mg-carbonate. (b) Mean weighted distance, indicating the compactness and cohesion of clusters (K-Means) or neurons (SOM). (c) Total number of clusters (K-Means) or neurons (SOM) matching Mg-carbonate across tested model sizes. (d) The execution time for SOM across tested model sizes.

The execution time (runtime) of the two models is not directly comparable, as the SOM model includes a greater number of hyperparameters, which can significantly affect training time. In this study, we fixed the training at 1000 batches of 5000 sequentially updated instances per batch, an arguably excessive configuration. A key factor contributing to the extended runtime of the SOM is its requirement for sequential updating, which prevents parallel processing. All models were developed and executed using PyCharm Community Edition 2024.3.4 with Python 3.12.4 on a Windows 11 Pro system equipped with a 12th Generation Intel Core i7 processor (12 physical cores, 20 threads) and 32 GB of RAM. Under this architecture, model runtimes did not consistently scale with model size—in some cases, larger SOMs completed faster than smaller ones. This counterintuitive behaviour is likely due to external factors influencing performance during long training periods potentially related to PyCharm’s memory management, CPU cache utilisation, or other system-level resource allocation effects. For the models referred to as SOM in Figure 22, the training times are specified in Table 5 and displayed in Figure 22d.

Table 5.

SOM model execution time (hours and minutes) by number of neurons.

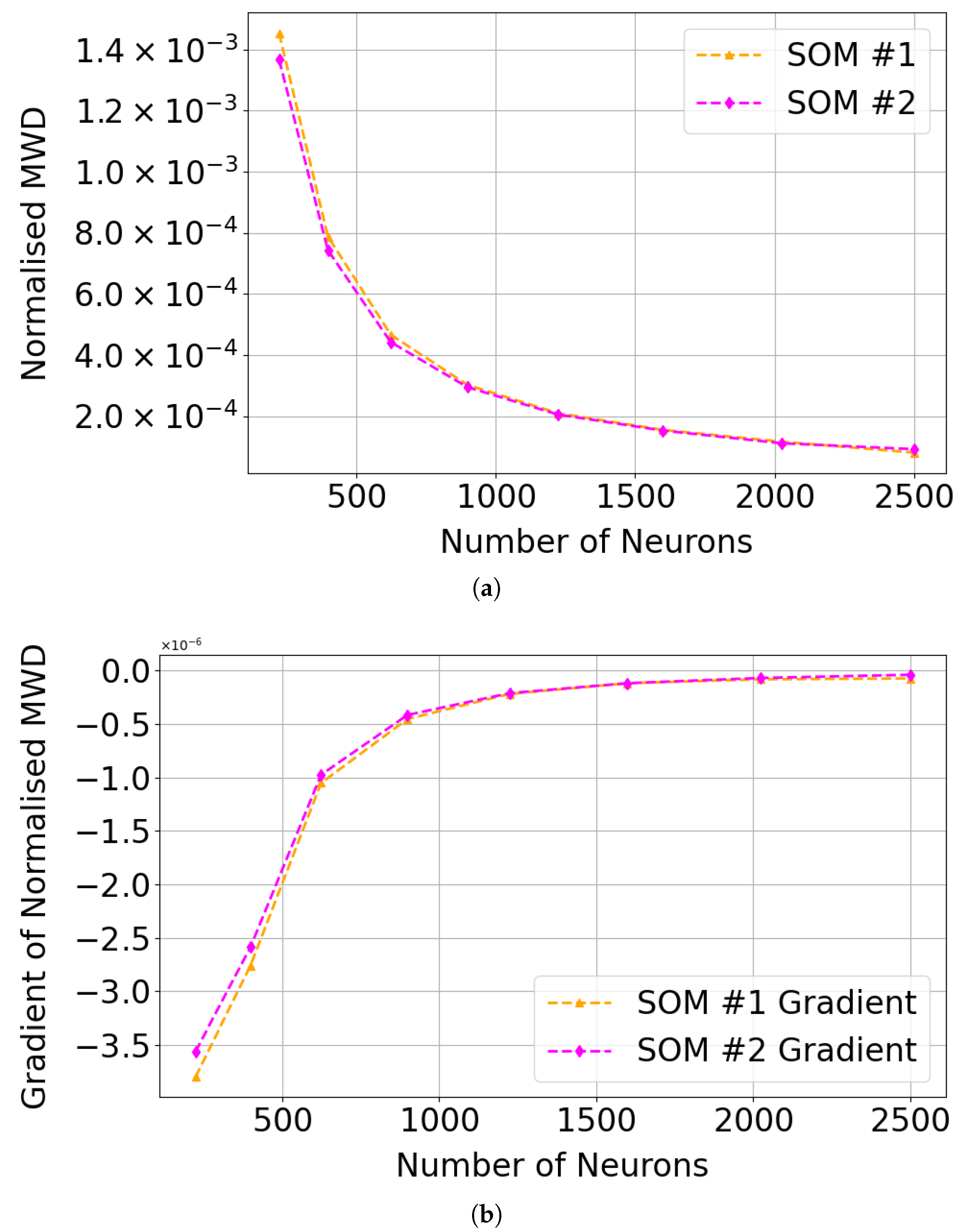

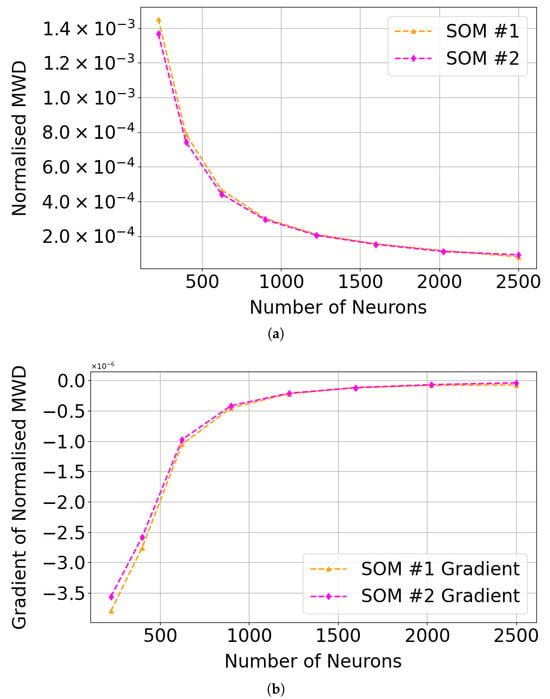

As shown in Figure 23 and Table 6 and Table 7, an SOM size of 30 × 30 (900 neurons) appears sufficient to cluster Mg-carbonate in this region, as the improvement in normalised Mean Weighted Distance (MWD) is minimal beyond this point. We note that the numerical gradient of the normalised MWD flattens beyond this point. The target image contained 460 × 640 pixels, of which 273,001 were valid (i.e., not equal to 65,535 in any layer), out of a total of 307,200. This suggests that the commonly used heuristic of neurons, where N is the number of valid pixels (see Section 3.4.1) may be excessive in this context.

Figure 23.

Performance trends in SOM clustering with larger SOM configurations. (a) Normalised MWD, calculated by dividing MWD by the number of neurons in each SOM configuration. (b) Gradient of the normalised MWD for SOM series #1 and SOM series #2 across larger SOM configurations, indicating that beyond a 30 × 30 SOM size, the incremental improvement in MWD becomes minimal.

Table 6.

Comparison of normalised mean weighted distance (MWD) and its gradient for SOM series #1 across different neuron counts.

Table 7.

Comparison of normalised mean weighted distance (MWD) and its gradient for SOM series #2 across different neuron counts.

In target region FRT00003E12, sufficient occurrences of Mg-carbonate–like spectra enabled the SOM to achieve fine separation across numerous clusters (Figure 12a). Illite in target region FRT0000634B provides a counterexample, where the SOM showed mixed results relative to k-means in clustering spectra correlated with illite. Neither method identified clusters exceeding a 0.70 correlation with the summary products derived from the illite spectrum in the MRO CRISM Type Spectra Library when the number of neurons or clusters was below 625. Beyond this threshold, the SOM consistently produced a four-neuron cluster (with only one exception across model sizes), whereas k-means did not reliably identify clusters until 1600 clusters were generated (Figure 24a–c), so confidence intervals are reported only from that point.

Figure 24.

Comparison of clustering performance between 30 independent k-means trials and two SOM model series (SOM #1 and SOM #2) across varying cluster/neuron counts. Mean performance is shown as solid lines. For k-means, the shaded region represents the 5th and 95th percentiles across the 30 trials. Illite was not reliably clustered by k-means at fewer than 1600 clusters. We calculate error metrics using only clusters or neurons with correlation with the summary products derived from the illite spectrum in the MRO CRISM Type Spectra Library above 0.70. (a) Total number of instances assigned to clusters (K-Means) or neurons (SOM) identified as representing illite. (b) Mean weighted distance, indicating the compactness and cohesion of clusters (K-Means) or neurons (SOM). (c) Total number of clusters (K-Means) or neurons (SOM) matching illite across tested model sizes. (d) The execution time for SOM #1 across tested model sizes.