Abstract

Remote sensing images usually contain abundant targets and complex information distributions. Consequently, networks are required to model both global and local information in the super-resolution (SR) reconstruction of remote sensing images. The existing SR reconstruction algorithms generally focus on only local or global features, neglecting effective feedback for reconstruction errors. Therefore, a Global Residual Multi-attention Fusion Back-projection Network (SRBPSwin) is introduced by combining the back-projection mechanism with the Swin Transformer. We incorporate a concatenated Channel and Spatial Attention Block (CSAB) into the Swin Transformer Block (STB) to design a Multi-attention Hybrid Swin Transformer Block (MAHSTB). SRBPSwin develops dense back-projection units to provide bidirectional feedback for reconstruction errors, enhancing the network’s feature extraction capabilities and improving reconstruction performance. SRBPSwin consists of the following four main stages: shallow feature extraction, shallow feature refinement, dense back projection, and image reconstruction. Firstly, for the input low-resolution (LR) image, shallow features are extracted and refined through the shallow feature extraction and shallow feature refinement stages. Secondly, multiple up-projection and down-projection units are designed to alternately process features between high-resolution (HR) and LR spaces, obtaining more accurate and detailed feature representations. Finally, global residual connections are utilized to transfer shallow features during the image reconstruction stage. We propose a perceptual loss function based on the Swin Transformer to enhance the detail of the reconstructed image. Extensive experiments demonstrate the significant reconstruction advantages of SRBPSwin in quantitative evaluation and visual quality.

1. Introduction

Remote sensing technology is a comprehensive method for large-scale Earth observation at the present stage, with wide-ranging applications in various fields, such as military, civilian, and agricultural ones [1]. Remote sensing images, as the data bases for the analysis and application of remote sensing technology, play essential roles in the direction of remote sensing target detection [2], scene recognition [3], target segmentation [4], change detection [5], and other directions. The quality of remote sensing images directly influences analysis outcomes, wherein spatial resolution is a critical parameter for assessing image quality. HR images offer greater clarity and contain richer high-frequency textural information, thereby enhancing the utilization value of HR remote sensing images. However, in reality, satellites are affected by the imaging environment and sensors, resulting in the LR remote sensing images generally acquired [6,7]. In response to the aforementioned practical problem, the most straightforward approach is to upgrade the hardware parameters of the satellite sensor. Nevertheless, this solution is complex and costly. Consequently, adopting software algorithms for post-processing, especially single-image super-resolution reconstruction (SISR) techniques, has emerged as a pragmatic and cost-effective means for reconstructing HR remote sensing images from LR remote sensing images.

SISR is a low-level computer vision task that aims to reconstruct an HR image containing more high-frequency information by utilizing limited information from a single LR image [8]. The popularity of this research direction is attributed to the valuable role played by the resulting HR images in various high-level computer vision applications [9,10,11]. Numerous scholars have conducted extensive research in the field of SISR. Currently, SISR methodologies can be classified into the three following main categories: interpolation-based [12,13], reconstruction-based [14], and learning-based approaches [15,16].

In recent years, with the remarkable success of deep learning (DL) across various domains, it has also found applications in addressing SISR challenges. Since Dong et al. [17] pioneered the introduction of CNN methods to solve the SISR problem, they have far surpassed traditional methods in performance. CNN-based SISR methods have also emerged with various architectures, such as residual learning [18,19] and dense connections [20,21]. The SISR task aims to minimize the reconstruction error between SR images and HR images. Iterative back projection (IBP) [22] ensures the reconstruction quality of SR images by propagating bidirectional reconstruction errors between LR and HR domains. Haris et al. [23] designed the Deep Back-projection Network (DBPN) to implement the IBP process. The DBPN utilizes CNNs to construct iterative up-projection and down-projection units, realizing the back-projection mechanism for reconstruction error correction. Although the CNN-based methods mentioned above achieved remarkable results in reconstructing natural images, the limitations of convolutional kernels prevent CNNs from performing global modeling [24]. Recently, the Vision Transformer (ViT) [25] demonstrated remarkable performance in both high-level [26,27] and low-level vision tasks [28,29], owing to its global feature extraction capabilities. Notably, the emergence of the Swin Transformer [30] as a backbone further enhanced the performance of SISR algorithms [31,32]. However, feature extraction along the channel dimension does not receive the same attention, and local features are neglected, causing difficulty in recovering detail effectively. Furthermore, window-based multi-head self-attention (W-MSA) and shifted window-based multi-head self-attention (SW-MSA) methods are utilized to achieve global information interaction, resulting in substantial computational overhead during training. Consequently, an effective and computationally considered method is expected to be developed for further performance optimization.

Unlike natural images, remote sensing images possess the characteristics of complex spatial structure distribution, multiple targets, and a variety of target scales and shapes. Their complexity poses significant challenges for the SR reconstruction of remote sensing images. Therefore, it is essential that the network not only focuses on global information to ensure consistency in spatial structure distribution, but also captures local details. These two aspects are crucial for restoring the integrity of target forms and shapes across different scales.

Focusing on the above issues, we propose a back-projection network based on the Swin Transformer—SRBPSwin—for adapting the characteristics of remote sensing images and enhancing the performance of SR reconstruction. Unlike the DBPN, which uses CNNs to build projection units, a Multi-attention Hybrid Swin Transformer Block (MAHSTB) is designed to build dense up-projection and down-projection units, providing a back-projection mechanism for feature errors at different resolutions. The MAHSTB employs channel and spatial attention, enabling the STB to model both channel and local information simply yet effectively. Therefore, the images reconstructed by SRBPSwin maintain structural consistency between cross-scale targets, restore large-scale image textures, and reconstruct the details of targets and scenes. Crucially, by implementing back projection, the network more comprehensively exploits feature information across different resolutions, reducing the reconstruction error between SR and HR images. Furthermore, a perceptual loss function is developed, based on transformer feature extraction, to minimize feature-level discrepancies, achieving more accurate super-resolution results.

The main contributions of this article are summarized as follows.

(1) SRBPSwin Networks: We propose a Swin Transformer-based dense back-projection network for the SISR reconstruction of remote sensing images. The developed network provides closed-loop feedback for reconstruction errors across different resolution spaces, enabling the perception and extraction of authentic texture features.

(2) Multi-Attention Hybrid Swin Transformer Block (MAHSTB): To address the challenges in super-resolution (SR) reconstruction caused by the abundance and diverse shapes of targets in remote sensing images, we improve the Swin Transformer Block (STB) with Channel and Spatial Attention Blocks (CSABs). This enhancement allows for further refinement of texture features, while maintaining computational cost, to overcome the shortcomings of position insensitivity and ignoring channel and local features when using (S)W-MSA in STB.

(3) Perception Loss Strategy based on Swin Transformer Feature Extraction: Utilizing the superior feature extraction capabilities of the pre-trained Swin Transformer network, we design an improved perceptual loss function. It effectively constrains the training process from the perspective of feature maps and significatively improves the quality of the reconstructed images.

(4) We conduct extensive experiments on various classes from the NWPU-RESISC45 dataset. The obtained experimental results confirm the effectiveness of the proposed method.

The remaining sections of this paper are organized as follows: Section 2 provides a concise overview of related work. Section 3 offers a detailed explanation of the proposed methodology. Section 4 presents experimental results on the NWPU-RESISC45 dataset. A discussion of the experimental results is presented in Section 5. The conclusions and perspectives for future work are provided in Section 6.

2. Related Work

2.1. Back Projection Based on CNNs

SR reconstruction is generally described as an iterative reduction in errors between SR and HR images. Back projection, as described in [22], is an effective method for minimizing reconstruction errors by providing feedback for the reconstruction errors. Haris et al. [23] pioneered the design of the DBPN model, combining back projection with CNNs. By utilizing multiple interconnected up-sample and down-sample layers, the method allows the for alternation of feature maps between HR and LR states. This approach provides a feedback mechanism for projection errors at different resolutions, resulting in superior reconstruction performance.

Building upon DBPN, Liu et al. subsequently designed two additional models: the Back-projection and Residual Network (BPRN) [33] and Attention-based Back-projection Network (ABPN) [34]. The BPRN model enhances the learning of HR features by incorporating convolutions that connect the up-sample features from the DBPN in the form of residual connections to the end. This enhancement enables the network to capture HR characteristics better, ultimately improving the quality of the reconstructed images. On the other hand, the ABPN is based on the BPRN, introducing residual connections in both the up-sample and down-sample layers. Additionally, the ABPN model integrates spatial attention modules after each down-sample layer, enhancing the effectiveness of LR feature propagation to the subsequent up-sample stage.

Although the aforementioned CNN-based back-projection SISR methods have demonstrated promising performance on natural images, the pixel information and structure of remote sensing images are more intricate than natural images. Therefore, the error feedback mechanism provided by back projection can effectively enhance the quality of reconstructed remote sensing images. However, due to the limitations of convolutional kernels, these methods may encounter challenges in capturing global information, thus impacting the quality of the reconstruction results. Consequently, it is imperative to design an SR method based on back projection for remote sensing images. This method should fully utilize pixel and structural information to effectively model global information in remote sensing images.

2.2. Vision Transformer-Based Models

With the remarkable success of transformers in natural language processing [35], they have naturally garnered attention in computer vision. In classic computer vision tasks, such as object detection [27,36], image classification [26,30], and image segmentation [28], methods based on the ViT [26] have achieved performance superiority beyond traditional CNNs in capturing global information and modeling long-range dependencies. In low-level visual tasks, such as image restoration, in order to obtain better visual representation capabilities for ViT, several studies [28,29,37,38,39,40,41] have demonstrated that introducing convolutional operations within the ViT framework can enhance its visual representation capabilities. The emergence of the Swin Transformer [30] has elevated the vast potential of the transformer in computer vision. The Swin Transformer enhances feature extraction in the ViT by utilizing a shift-window mechanism to model distant dependencies. Consequently, Swin Transformer-based methods have promoted development in SISR. Inspired by earlier work in image restoration, Liang et al. [31] utilized the Swin Transformer as a backbone network and incorporated convolutional layers for shallow feature extraction. They introduced SwinIR for SISR, achieving performance surpassing the CNN-based SISR algorithms. Building upon SwinIR, Chen et al. [32] proposed channel attention mechanisms within the Swin Transformer Block by utilizing pixel performance. They also introduced overlapping cross-attention modules to enhance feature interactions between adjacent windows, effectively aggregating cross-window information and achieving superior reconstruction performance compared to SwinIR.

Although STB promotes the extraction of global spatial features, the extraction of channel-wise features needs equal attention. Additionally, the (S)W-MSA can cause insensitivity to pixel positions and neglect local feature details. Consequently, its performance can be further improved.

2.3. Deep Learning-Based SISR for Remote Sensing Images

In remote sensing, HR images are expected to be obtained, leading to the extensive application of SISR. The development of SISR in remote sensing parallels the trends observed in natural image SISR. With rapid advancements in DL, the utilization of CNNs for remote sensing image SR reconstruction has demonstrated performance far surpassing traditional algorithms. This approach has become mainstream in remote sensing image SR reconstruction algorithms.

Lei et al. [42] first introduced a CNN called the Local–Global Combination Network (LGCNet) for remote sensing image super-resolution reconstruction. Liu et al. [43] introduced the saliency-guided remote sensing image super-resolution, which utilizes saliency maps to guide the network in learning more high-resolution saliency maps and provide additional structural priors. Huang et al. [44] proposed the Pyramid Information Distillation Attention Network (PIDAN), which employs the Pyramid Information Distillation Attention Block (PIDAB) to enable the network to perceive a wider range of hierarchical features and further improve the recovery ability of high-frequency information. Zhao et al. [45] proposed the second-order attention generator adversarial attention network (SA-GAN), which leverages a second-order channel attention mechanism in the generator to fully utilize the prior information in LR images. Chen et al. [46] presented the Residual Split-attention Network (RSAN), which utilizes the multipath Residual Split-attention (RSA) mechanism to fuse different channel dimensions to promote feature extraction and ensure that the network focuses more on regions with rich details. Wang et al. [47] proposed the Multiscale Enhancement Network (MEN), incorporating a Multiscale Enhancement Module (MEM), which utilizes a parallel combination of convolutional layers comprising kernels of varying sizes to refine the extraction of multiscale features, thereby enhancing the network’s reconstruction capabilities. Zhang et al. [48] introduced the Dual-resolution Connected Attention Network (DRCAN), which constructs parallel branches—an LR branch and an HR branch—to integrate features at different spatial resolutions in order to enhance the details of reconstructed images. In response to the complex structure, large variation in target scale, and high pixel similarity of remote sensing images, the above-mentioned methods, although utilizing techniques like residual learning and channel attention to enhance the global modeling capacity of CNNs, still fail to effectively overcome the limitations of local feature extraction by convolutional kernels. Therefore, the design of a more effective SISR method for adaptation to remote sensing images remains crucial.

To address the limitations of CNNs in remote sensing image super-resolution reconstruction, we propose SRBPSwin, a super-resolution reconstruction algorithm based on the Swin Transformer. SRBPSwin effectively perceives global image features and employs up-projection and down-projection layers to transmit reconstruction errors. Additionally, it introduces a CSAB to mitigate the inability of the STB to capture both channel-wise and local features. The SRBPSwin can better utilize remote sensing image features, ultimately improving the quality of the SR reconstruction.

3. Methodology

In this section, firstly, we begin by presenting the overall framework of SRBPSwin. Secondly, we introduce the MAHSTB and the Dense Back-projection Unit. Finally, we introduce the loss function utilized for training.

3.1. Network Architecture

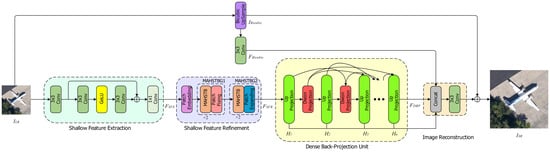

As illustrated in Figure 1, the proposed SRBPSwin consists of the four following stages: shallow feature extraction, shallow feature refinement, dense back-projection, and image reconstruction. The stages of shallow feature refinement and dense back projection comprise multiple MAHSTBGs (MAHSTB cascade post-processing modules). These post-processing modules include Patch Fixing, Patch Expanding, and Patch Shrinking. The architecture of incorporating convolutional layers before and after the Swin Transformer results in a better visual representation [31,32,37,38,39].

Figure 1.

The overall architecture of SRBPSwin. indicates the element-wise sum.

The shallow feature extraction stage comprises a convolutional layer, a residual block, and a convolutional layer. Given an input LR image (where , , and are the height, width, and number of input channels of the LR image, respectively), the shallow feature extraction stage produces feature maps ( represents feature channels). The shallow feature refinement stage comprises a Patch Embedding layer and two MAHSTBGs. The Patch Embedding layer partitions the input LR image into non-overlapping patches, reducing the dimensions of the feature maps by a factor of 4. MAHSTBG1 employs the Patch Fixing operation to maintain the feature maps’ dimensions and the number of feature channels. To prevent the reduction in feature map size caused by Patch Embedding from hindering feature extraction in deeper network layers, the Patch Expanding operation is utilized to up-sample and restore the feature maps to their original dimensions, thereby obtaining the refined shallow feature . The core of SRBPSwin is the Dense Back-projection Unit, composed of a series of Up-projection Swin Units and Down-projection Swin Units. It extracts back-projection features and transfers reconstruction errors; the obtained dense back-projection feature is ( is the scale factor). For the reconstruction stage, obtains through bicubic up-sampling. Then, a convolutional layer is applied to generate . The high-resolution features obtained from the Up-projection Units are concatenated with and . The concatenated features are processed through another convolutional layer and then added to , resulting in an SR image .

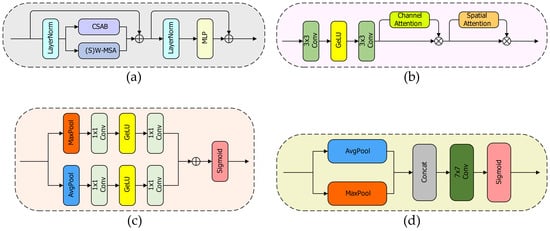

3.2. Multi-Attention Hybrid Swin Transformer Block (MAHSTB)

The structure of MAHSTB is illustrated in Figure 2. The CSAB is inserted in the STB parallel to W-MSA and SW-MSA. We multiply the output of the CSAB by a small constant to prevent conflicts between CSAM and (S)W-MSA during feature representation and optimization. Hence, for a given input feature , the resulting output feature , obtained through MAHSTB, is represented as follows:

where are intermediate features and , , , , and are LayerNorm, CSAB, W-MSA, SW-MSA, and Multi-layer Perceptron operations, respectively.

Figure 2.

(a) Multi-attention Hybrid Swin Transformer Block (MAHSTB). (b) Channel- and Spatial-attention Block (CSAB). (c) Channel attention (CA) block. (d) Spatial attention (SA) block. indicates the element-wise sum. indicates the element-wise product.

For a given input feature of size (where , , are the height, width, and number of input channels of the input feature, respectively), the first step involves partitioning the input feature into ( represents the window size) non-overlapping local windows, each of size , to obtain local window features . Secondly, self-attention is computed within each window. , , and are linearly mapped to , , and , respectively. Ultimately, self-attention within each window is computed as follows:

where is the dimension of and is the relative position encoding. In addition, as in [34], cross-window connections between adjacent non-overlapping windows are achieved by setting the shift size to half the window size during the shift window stage.

CSAB consists of two convolutional layers interconnected by a GELU activation. We controlled the number of channels in two convolutional layers through a compression constant to reduce computational cost [32]. Specifically, for input features with a number of channels , the first convolutional layer reduces the number of channels to , followed by GELU activation, and then the second convolutional layer restores the number of channels to . Lastly, the method described in [49] is introduced to implement channel attention (CA) and spatial attention (SA) to improve the ability of STB to capture both channel and local features.

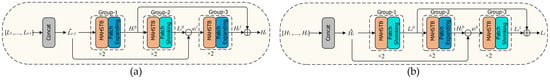

3.3. Dense Back-projection Unit (DBPU)

DBPU is constructed by the interleaved connection of Up-projection Swin Units and Down-projection Swin Units. The structures of the Up-projection Swin Unit (UPSU) and Down-projection Swin Unit (DPSU) are illustrated in the Figure 3. An UPSU consists of three MAHSTBG blocks. Specifically, Group-1 and Group-3 consist of two MAHSTBs and Patch Expanding, while Group-2 consists of two MAHSTBs and Patch Shrinking. The Patch Shrinking operation reduces the sizes of the input features without changing the number of feature channels. Group-1 and Group-3 achieve the up-sampling process, while Group-2 accomplishes the down-sampling process. The Up-projection process is represented as follows:

where and represent the Patch Expanding and Patch Shrinking operations, respectively.

Figure 3.

(a) Up-projection Swin Unit (UPSU). (b) Down-projection Swin Unit (DPSU). indicates the element-wise sum. indicates the element-wise difference.

The UPSU initially takes the LR feature maps, , generated by all previous DPSU outputs, and concatenates them to form as input, establishing a dense connection. These are mapped to the HR space, yielding . Subsequently, is back projected to the LR space, generating . By subtracting from , the LR space back-projection error is obtained. Then, is mapped to the HR space as . Finally, is obtained by summing and , completing the UPSU operation.

The DPSU operation is similar to that of the UPSU. It aims to map input HR feature maps to the LR feature map . The process is illustrated as follows:

The UPSU and DPSU are alternately connected, enabling the feature maps to alternate between HR and LR spaces, providing a feedback mechanism for the projection error in each projection unit and achieving self-correction.

3.4. Loss Function

In order to enhance the textural details of SR images, the developed loss function consists of , a norm loss, and a perceptual loss. Firstly, the fundamental norm loss is defined as follows:

Inspired by [18,34], we utilize the Swin Transformer, pre-trained with ImageNet-22K weights, to construct the perceptual loss function.

where represents the feature maps obtained by the complete Swin-B network.

Finally, the optimization loss function for the entire network is defined as follows:

where is a scalar to adjust the contribution of the perceptual loss.

4. Experimentation

4.1. Datasets

This study utilized the NWPU-RESISC45 [50] remote sensing dataset, comprising 45 classes of remote sensing scene data, with 700 images in each class, and resulting in a total of 31,500 RGB images at spatial resolutions ranging from 0.2 to 30 m, each sized 256 × 256 pixels. We randomly selected 100 images from each class as a training dataset, 10 as a validation dataset, and 10 as a testing dataset. Consequently, the final dataset consisted of 4500 images in the training dataset, 450 in the validation dataset, and 450 in the testing dataset. Meanwhile, to ensure the authenticity of the experimental results, there was no intersection among the training, validation, and testing datasets.

4.2. Experimental Settings

In this study, we focused on the 2 and 4 scale factors. LR images were obtained by down-sampling HR images using bicubic interpolation [51], considering the corresponding HR images as ground truth. Additionally, training images were augmented through random horizontal and vertical flips. The images were converted to the YCbCr color space, and training was performed on the Y channel [52]. The SR results were evaluated by calculating the peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) [53] and structural similarity (SSIM) [54] on the Y channel.

We employed the Adam optimizer [55] for model training, with and . The initial learning rate was set to 10−4, and there were 1000 total training epochs. For the 2 scale factor, the batch size was set to 2, and the number of feature channels C was set to 96. For the 4 scale factor, the batch size was set to 4, and the number of feature channels C was set to 48. The number of up-sample units N was set to 2. The proposed method was implemented utilizing the PyTorch framework version 1.11. All experiments were conducted on an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 GPU.

4.3. Evaluation Index

Given a real HR image, the PSNR value of the SR reconstructed image is obtained as follows:

where and represent the values of the -th pixel in and , respectively, and represents the number of pixels in the image. A higher PSNR value indicates better image quality for the reconstructed image. The SSIM calculation formula is described as follows:

where , , , , are the mean, standard deviation, and covariance of and , respectively, while and are constants.

4.4. Ablation Studies

We designed two sets of ablation experiments on the NWPU-RESISC45 dataset, with a scale factor of 2, to verify the effectiveness of the MAHSTB and perceptual Swin loss.

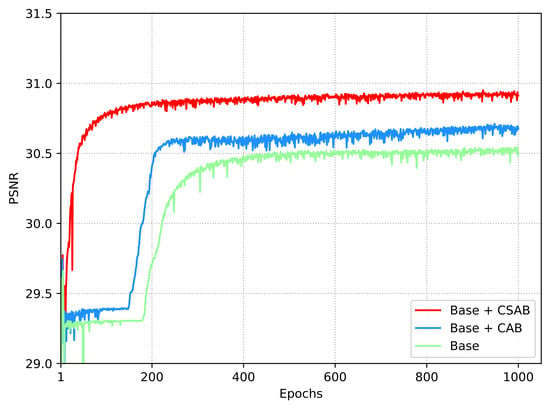

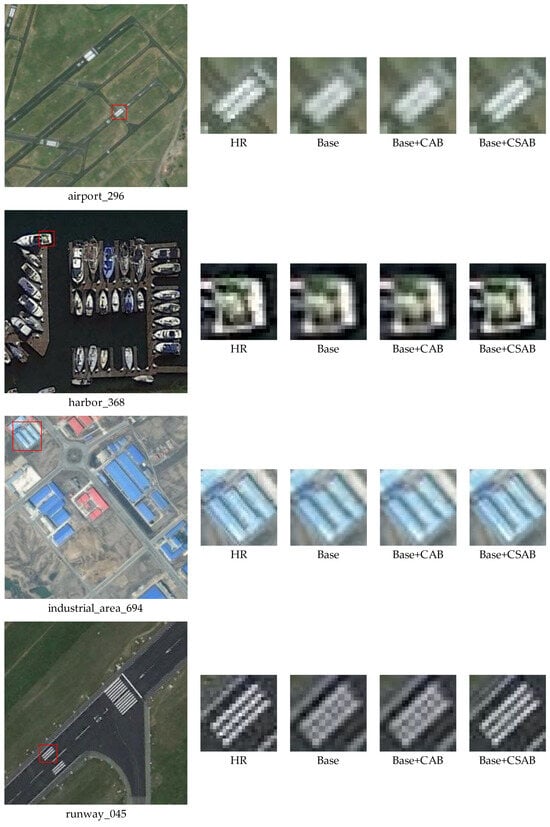

The first set of ablation experiments consisted of three models: Base, Base + CAB, and Base + CSAB(MAHSTB). The Base model is a basic network under only STB. The Base + CAB model replaces CSAB of MAHSTB with CAB. Figure 4 shows the PSNR results of the three models on the validation dataset, showing that the curve of the proposed Base + CSAB model is significantly higher than those of the Base and Base + CAB models. Table 1 presents the quantitative results of experiment 1 on the test dataset, indicating that Base + CSAB achieves the best SR performance. Compared to Base, Base + CAB improves the PSNR by 0.866 dB, indicating that introducing channel attention in parallel at the (S)W-MSA position in the STB enhances the network’s feature representation capability. Furthermore, Base + CSAB increases PSNR by 0.866 dB and 1.165 dB, respectively, compared to Base and Base + CAB. This shows that adding SA after CAB to form CSAB offers a more effective visual representation enhancement in the STB than using CAB only.

Figure 4.

PSNR curves of our method, based on using CSAB or not. Base refers to the network that uses only STB, while Base + CSAB denotes MAHSTB. The results are compared on the validation dataset with a scale factor of 2 during the overall training phase.

Table 1.

Ablation studies to verify the effectiveness of CSAB with a scale factor of 2 on the testing dataset. Base refers to the network that uses only STB, while Base + CSAB denotes MAHSTB. Red represents the best score.

Figure 5 illustrates the qualitative results of image reconstruction by Base, Base + CAB, and Base + CSAB. For better comparison, we marked the area to be enlarged on the left side of the HR image with a red box and provided local close-ups of the reconstructed area under different methods on the right side. It is observed that Base + CSAB achieves the best visual performance. In “airport_296” and “industrial_area_694”, the reconstructed images show clearer details and sharper edges for the runway ground markings and industrial buildings. In “harbor_368”, the network-reconstructed ship details are more abundant. For “runway_045”, the image texture is more naturally reconstructed by the network. These qualitative results demonstrate that the multi-attention hybrid approach achieved by Base + CSAB enables the STB to utilize the self-attention mechanism for global feature modeling, while also capturing channel and local features, thereby enhancing the quality of the reconstructed images.

Figure 5.

Visual comparison of ablation study to verify the effectiveness of MAHSTB; Base refers to the network that uses only STB, while Base + CSAB denotes MAHSTB. We used a red box to mark the area for enlargement on the left HR image. On the right, we present the corresponding HR image and the results reconstructed by the different methods.

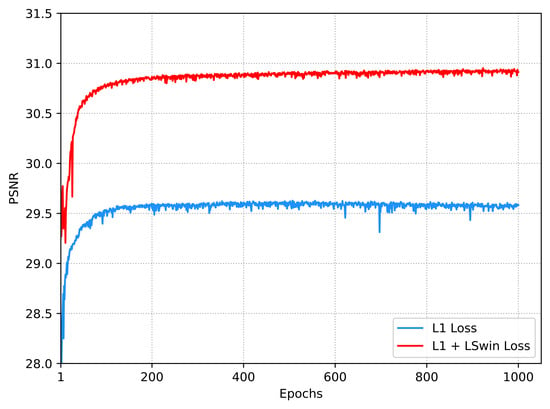

The second set of experiments involved training SRBPSwin using the loss function alone, and a composite loss function (). Figure 6 shows the results of the second set of experiments on the validation dataset. It can be observed that the PSNR curve under is higher than that under . Additionally, Table 2 presents the results of the testing dataset. SRBPSwin trained with achieves a PSNR of 32.917 dB, and SRBPSwin trained with achieves a PSNR of 33.278 dB, showing an improvement of 0.361 dB. This suggests that constructing the perceptual Swin loss function enhances the texture and details in the reconstructed images, utilizing the Swin Transformer with pre-trained weights from ImageNet-22K.

Figure 6.

PSNR curves of our method, based on using or not. The results are compared on the validation dataset with a scale factor of 2 during the overall training phase.

Table 2.

Ablation studies to verify the effectiveness of with a scale factor of 2× on the testing dataset. Red represents the best score.

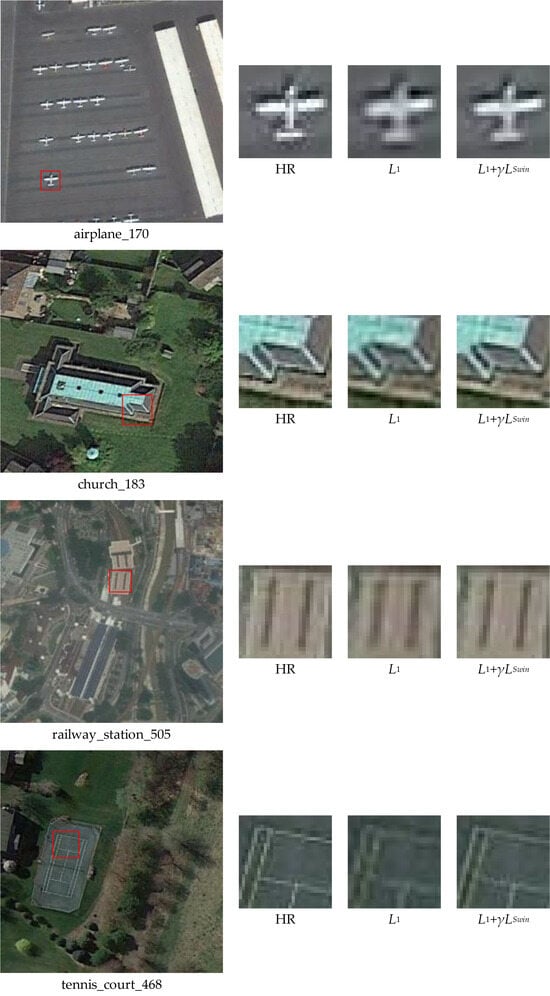

Figure 7 shows the qualitative results of the loss function and the composite loss function. It indicates that the composite loss function achieves the best visual outcomes. Training the network with yields clearer edges for the airplane target in “airplane_170”. In “church_183”, the network recovers abundant details for the textural features of the building. For “railway_station_505”, the reconstructed station texture appears more refined. In “tennis_court_468”, the restored court looks more natural. These qualitative results validate that effectively reduces the feature distance and enhances the SR reconstruction capability of the network.

Figure 7.

Visual comparison of ablation study to verify the effectiveness of . We used a red box to mark the area for enlargement on the left HR image. On the right, we present the corresponding HR image and the results reconstructed using the different loss functions.

4.5. Comparison with Other CNN-Based Methods

We further compare our method with several open-source SR methods, including the SRCNN [17], VDSR [56], SRRESNet [18], EDSR [19], DBPN [23], LGCNET [42] models. All of these methods were trained and tested under the same conditions for a fair comparison.

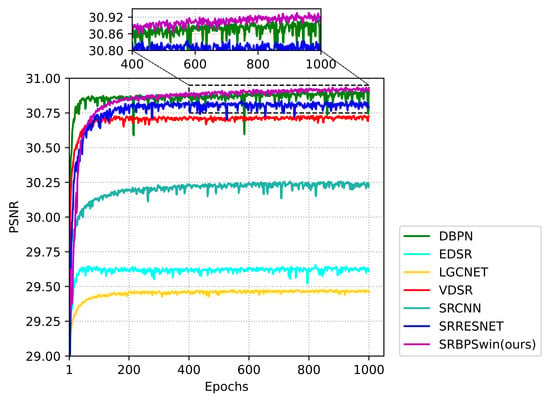

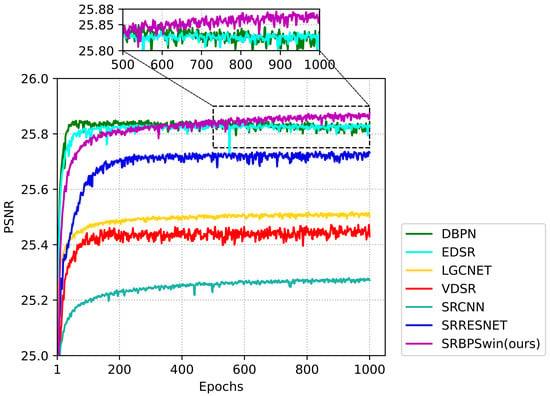

Figure 8 and Figure 9 illustrate the quantitative comparison results of the PSNR curves on the validation dataset for the above methods at 2 and 4 scale factors. It can be observed that, at the 2 scale factor, the proposed SRBPSwin starts to surpass other methods in PSNR after the 400th epoch. Similarly, at the 4 scale factor, SRBPSwin begins to outperform in PSNR after the 500th epoch.

Figure 8.

PSNR comparison for different methods on the validation dataset with a scale factor of 2 during the training phase.

Figure 9.

PSNR comparison for different methods on the validation dataset with a scale factor of 4 during the training phase.

Table 3 and Table 4 present the average quantitative evaluation results at the 2 and 4 scales on the 45 classes of testing datasets for all of the methods above. In these tables, PSNR and SSIM scores ranking first in each class are highlighted in red, while scores ranking second are highlighted in blue. If a method achieves the top ranking in both the PSNR and SSIM scores for a given class, it is considered as having the best reconstruction performance.

Table 3.

Mean PSNR (dB) and SSIM values of each class of our NWPU-RESISC45 testing dataset for each method. The results are evaluated on a scale factor of 2. The best result is highlighted in red, while the second is highlighted in blue.

Table 4.

Mean PSNR (dB) and SSIM values of each class of our NWPU-RESISC45 testing dataset for each method. The results are evaluated on a scale factor of 4. The best result is highlighted in red, while the second is highlighted in blue.

Obviously, at the 2 scale factor, our approach achieved the best PSNR/SSIM results in 42 out of the 45 classes, while the second-best DBPN attained the best PSNR/SSIM in only one class out of the remaining three. At the 4 scale factor, our method achieves the best PSNR/SSIM results in 26 classes, whereas the second-best DBPN achieves the best PSNR/SSIM results in only 10 out of the remaining 19 classes.

Table 5 presents the overall average quantitative evaluation results for each method on the testing dataset at the 2 and 4 scale factors, indicating the superiority of our SRBPSwin model over other methods.

Table 5.

Performance comparison of different methods on our NWPU-RESISC45 testing dataset for scale factors of 2 and 4x. The best result is highlighted in red, while the second is highlighted in blue.

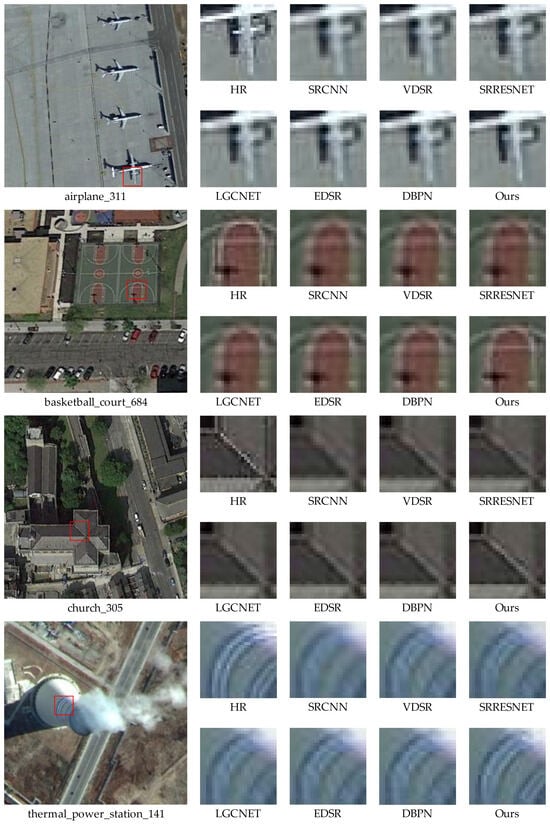

Figure 10 and Figure 11 show several qualitative comparison results of the above methods. For better comparison, we marked the areas with significant differences after reconstruction utilizing different methods with red rectangles in the HR images. Additionally, localized close-ups of these regions, after reconstruction by each method, are provided on the right side.

Figure 10.

Visual comparison of some representative SR methods and our model at the 2 scale factor.

Figure 11.

Visual comparison of some representative SR methods and our model at the 4 scale factor.

Figure 10 presents the comparison results at the 2 scale factor. From the illustration, it is evident that the reconstruction results of SRBPSwin are the best compared to other methods. The proposed SRBPSwin yields abundant wing features in “airplane_311”. In “basketball_court_684”, more venue details have been reconstructed. In “church_305”, the reconstructed roof edges are clearer. In “thermal power station_141”, the signage on the chimney is reconstructed with more textures. Figure 11 presents the comparison results at the 4 scale factor. The illustration shows that the proposed SRBPSwin exhibits more distinct edges in the airport ground signage in “airport_031”. In “basketball_court134”, the reconstructed field lines are more precise. In “commercialid_area_199”, the reconstructed roof area features are more prominent. In “runway_199”, the correct runway markings are reconstructed.

5. Discussion

In this section, we will further discuss the impact of the proposed SRBPSwin.

- (1)

- Comparison with other methods: The experimental results in Section 4.5 demonstrate that the proposed SRBPSwin method achieves superior SR performance compared with the SRCNN, VDSR, SRRESNET, LGCNET, EDSR, and DBPN models. At a scale factor of 2, our method restored sharp edges and reconstructed rich details. At a scale factor of 4, the reconstructed images maintained their shapes in more naturally, without introducing redundant textures. It confirms that the back-projection mechanism in SRBPSwin effectively provides feedback for reconstruction errors, thereby enhancing the reconstruction performance of the proposed network.

- (2)

- The impacts of the multi-attention hybrid mechanism: Based on the quantitative results of ablation study 1 in Section 4.4, the introduction of CAB improved PSNR by 0.279 dB, compared with STB. After combining CSAB, the PSNR increased by 0.866 dB and 1.165 dB under CAB and STB, respectively, indicating that the multi-attention hybrid mechanism significantly enhanced the network’s SR performance. Additionally, it verifies that the fusion of CSAB improved the ability of both the capture channel and local features of STB. Qualitative results further demonstrate that utilizing CSAB reconstructed local fine textures accurately and achieved sharper edges.

- (3)

- The impacts of the perceptual loss strategy based on the Swin Transformer: Analysis of the quantitative results from ablation study 2 in Section 4.4 indicates that the loss led to a PSNR improvement of 0.361 dB, compared to the loss. This demonstrates that the perceptual loss strategy enhanced the reconstruction performance of the network at the feature map level. Qualitative results further show that images exhibit better detail recovery and appear more natural under the composite loss.

- (4)

- Limits of our method: Firstly, the STB in SRBPSwin incurs significant computational overhead when calculating self-attention, resulting in slower training speeds. Secondly, while the network does not introduce artifacts at large-scale factors, the reconstructed images tend to appear smooth.

6. Conclusions

This study introduces a Swin Transformer-based model, SRBPSwin, based on the Swin Transformer. The main contribution of this research is the design of the Multi-attention Hybrid Swin Transformer Block (MAHSTB) to improve the feature representation of the Swin Transformer Block for high-resolution reconstruction. Furthermore, the MAHSTB is employed to construct dense up-projection and down-projection units, providing a back-projection mechanism for feature errors at different resolutions. The presented method achieves more accurate SR results. Additionally, we incorporate a Swin Transformer with ImageNet-22K pre-trained weights as a perceptual loss function, developing our method to enhance the quality of reconstructed remote sensing images. Extensive experiments and ablation studies validate the effectiveness of our proposed method.

However, the computation of self-attention incurs significant computational overhead, leading to longer training times. Additionally, with increasing scale factor, the reconstructed images become smoother. In future work, we plan to further develop the network to become more lightweight, aiming to accelerate the training process and incorporate multiscale up-sample branches to extract features at various scales, thereby enhancing the network’s reconstruction capabilities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Q.; methodology, J.W.; investigation, S.C.; supervision, M.Z.; visualization, J.S.; data curation, Z.H.; funding acquisition, X.J.; software, Y.Q.; validation, Y.Q.; writing—original draft, Y.Q.; writing—review and editing, Y.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Science and Technology Department of Jilin Province of China under Grant number 20220201146GX, and in part by the Science and Technology project of Jilin Provincial Education Department of China under Grant number JJKH20220689KJ.

Data Availability Statement

The data of experimental images used to support the findings of this research are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, Z.; Yi, J.; Guo, J.; Song, Y.; Lyu, J.; Xu, J.; Yan, W.; Zhao, J.; Cai, Q.; Min, H. A Review of Image Super-Resolution Approaches Based on Deep Learning and Applications in Remote Sensing. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, S.; Hu, M.; Song, Q. Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images Based on Adaptive Multi-Scale Feature Fusion Method. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Liu, W.; Shan, H.; Li, E.; Li, X.; Zhang, L. Remote Sensing Scene Classification Based on Multibranch Fusion Network. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, D.; Liu, M.; Jia, J. CNN and Transformer Fusion for Remote Sensing Image Semantic Segmentation. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; An, R.; Zhao, S.; Jiang, T. A Deep Learning-Based Robust Change Detection Approach for Very High Resolution Remotely Sensed Images with Multiple Features. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Shao, J.; Li, X.; Shen, H. Remote Sensing Image Super-Resolution via Mixed High-Order Attention Network. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 5183–5196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustsson, E.; Timofte, R. NTIRE 2017 Challenge on Single Image Super-Resolution: Dataset and Study. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1122–1131. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Yuan, Q.; Li, J.; Sun, J.; Zhang, X. Scene-Adaptive Remote Sensing Image Super-Resolution Using a Multiscale Attention Network. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 58, 4764–4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musunuri, Y.; Kwon, O.; Kung, S. SRODNet: Object Detection Network Based on Super Resolution for Autonomous Vehicles. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Zhu, Q.; Sun, X.; Lin, W.; Guan, Q. EML-GAN: Generative Adversarial Network-Based End-to-End Multi-Task Learning Architecture for Super-Resolution Reconstruction and Scene Classification of Low-Resolution Remote Sensing Imagery. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Brussels, Belgium, 11–16 July 2021; pp. 5397–5400. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Mavromatis, S.; Zhang, F.; Du, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Liu, R. Single-Image Super-Resolution for Remote Sensing Images Using a Deep Generative Adversarial Network with Local and Global Attention Mechanisms. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 3000224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wu, X. An edge-guided image interpolation algorithm via directional filtering and data fusion. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2006, 15, 2226–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, K.; Siu, W. Robust Soft-Decision Interpolation Using Weighted Least Squares. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2012, 21, 1061–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Gao, X.; Tao, D.; Li, X. Single Image Super-Resolution with Non-Local Means and Steering Kernel Regression. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2012, 21, 4544–4556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Wright, J.; Huang, T.; Ma, Y. Image Super-Resolution Via Sparse Representation. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2010, 19, 2861–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg, T.; Elad, M. A Statistical Prediction Model Based on Sparse Representations for Single Image Super-Resolution. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2014, 23, 2569–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, C.; Loy, C.; He, K.; Tang, X. Image Super-Resolution Using Deep Convolutional Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2016, 38, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledig, C.; Theis, L.; Huszár, F.; Caballero, J.; Cunningham, A.; Acosta, A.; Aitken, A.; Tejani, A.; Totz, J.; Wang, Z.; et al. Photo-Realistic Single Image Super-Resolution Using a Generative Adversarial Network. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, B.; Son, S.; Kim, H.; Nah, S.; Lee, K. Enhanced Deep Residual Networks for Single Image Super-Resolution. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1132–1140. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, R.; Fu, K.; Sun, H.; Sun, X.; Wang, L. Image Superresolution Using Densely Connected Residual Networks. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. Lett. 2018, 25, 1565–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, J.; Ma, X.; Zhang, X.; Pun, M. GCRDN: Global Context-Driven Residual Dense Network for Remote Sensing Image Superresolution. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 4457–4468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irani, M.; Peleg, S. Improving resolution by image registration. CVGIP Graph. Models Image Process. 1991, 53, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haris, M.; Shakhnarovich, G.; Ukita, N. Deep Back-Projection Networks for Single Image Super-Resolution. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 43, 4323–4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wei, D.; Qin, C.; Wang, H.; Pfister, H.; Fu, Y. Context Reasoning Attention Network for Image Super-Resolution. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 4258–4267. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16 × 16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Virtual, 3–7 May 2021; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Q.; Wang, M. Swin-unet: Unet-like pure transformer for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 205–218. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Cun, X.; Bao, J.; Zhou, W.; Liu, J.; Li, H. Uformer: A General U-Shaped Transformer for Image Restoration. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 17662–17672. [Google Scholar]

- Zamir, S.; Arora, A.; Khan, S.; Hayat, M.; Khan, F.; Yang, M. Restormer: Efficient Transformer for High-Resolution Image Restoration. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 5718–5729. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer using Shifted Windows. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 9992–10002. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Cao, J.; Sun, G.; Zhang, K.; Van Gool, L.; Timofte, R. SwinIR: Image Restoration Using Swin Transformer. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW), Montreal, BC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 1833–1844. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Zhou, J.; Qiao, Y.; Dong, C. Activating More Pixels in Image Super-Resolution Transformer. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 22367–22377. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Siu, W.; Chan, Y. Joint Back Projection and Residual Networks for Efficient Image Super-Resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE Asia-Pacific Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference (APSIPA ASC), Honolulu, HI, USA, 12–15 November 2018; pp. 1054–1060. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, C.; Siu, W.; Chan, Y. Image Super-Resolution via Attention Based Back Projection Networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW), Seoul, Korea (South), 27–28 October 2019; pp. 3517–3525. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, X.; Tian, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Ren, H.; Wei, X.; Xia, H.; Shen, C. Twins: Revisiting the design of spatial attention in vision transformers. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Sydney, Australia, 14 December 2021; pp. 9355–9366. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Xiao, B.; Codella, N.; Liu, M.; Dai, X.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, L. CvT: Introducing Convolutions to Vision Transformers. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, T.; Singh, M.; Mintun, E.; Darrell, T.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Early convolutions help transformers see better. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Sydney, Australia, 14 December 2021; pp. 30392–30400. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, K.; Guo, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, A.; Yu, F.; Wu, W. Incorporating Convolution Designs into Visual Transformers. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 559–568. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Guo, T.; Xu, C.; Deng, Y.; Liu, Z.; Ma, S.; Xu, C.; Gao, W. Pre-Trained Image Processing Transformer. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 12294–12305. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Lu, X.; Qian, S.; Lu, J.; Zhang, X.; Jia, J. On Efficient Transformer-Based Image Pre-training for Low-Level Vision. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.10175. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, S.; Shi, Z.; Zou, Z. Super-Resolution for Remote Sensing Images via Local-Global Combined Network. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2017, 14, 1243–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhao, L.; Li, J.; Zhao, H.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Cao, W. Saliency-Guided Remote Sensing Image Super- Resolution. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 5144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Guo, Z.; Wu, L.; He, B.; Li, X.; Lin, Y. Pyramid Information Distillation Attention Network for Super-Resolution Reconstruction of Remote Sensing Images. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 5143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ma, Y.; Chen, F.; Shang, E.; Yao, W.; Zhang, S.; Yang, J. SA-GAN: A Second Order Attention Generator Adversarial Network with Region Aware Strategy for Real Satellite Images Super Resolution Reconstruction. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wu, Y.; Lu, T. Remote Sensing Image Super-Resolution with Residual Split Attention Mechanism. IEEE J. STARS. 2023, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shao, Z.; Lu, T. Remote Sensing Image Super-Resolution via Multiscale Enhancement Network. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, T. Remote sensing image super-resolution via dual-resolution network based on connected attention mechanism. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.; Kweon, I. Cbam: Convolutional Block Attention Module. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, G.; Han, J.; Lu, X. Remote Sensing Image Scene Classification: Benchmark and State of the Art. Proc. IEEE. 2017, 105, 1865–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zuo, W.; Zhang, L. Learning a Single Convolutional Super-Resolution Network for Multiple Degradations. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 3262–3271. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Fang, F.; Mei, K.; Zhang, G. Multi-scale Residual Network for Image Super-Resolution. In Proceedings of the Europe Conference Computing Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 517–532. [Google Scholar]

- Horé, A.; Ziou, D. Image Quality Metrics: PSNR vs. SSIM. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Istanbul, Turkey, 23–26 August 2010; pp. 2366–2369. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Bovik, A.; Sheikh, H.; Simoncelli, E. Image quality assessment: From error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2004, 13, 600–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingma, D.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Lee, J.; Lee, K. Accurate Image Super-Resolution Using Very Deep Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 1646–1654. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).