Abstract

Anaerobic digestion of organic waste offers renewable energy and waste-management benefits, relevant to multiple SDGs. This study evaluates a proposed 50 t/d farm-based biogas plant co-digesting poultry manure (PM) and fruit/vegetable waste (FVW) in South Africa. Five substrate blends (100% PM, 100% FVW, and three PM–FVW mixtures) and three biogas utilization routes (100% electricity via a combined heat and power (CHP) system, 50/50 CHP–biomethane, and 100% biomethane) were modelled in a combined techno-economic analysis (TEA) and life-cycle assessment (LCA) framework. Key metrics included GWP100 per ton of feedstock and the project’s internal rate of return (IRR), debt service coverage ratio (DSCR), and net present value (NPV) over a 20-year project lifespan. Under base-case assumptions, electricity-led pathways yield the highest returns; in the best case, 80% FVW + 20% PM with 100% CHP achieves a project IRR of 10% with a minimum DSCR of 2.4. The LCA shows total GWP100 ranging 118–168 kgCO2-eq/t, minimum for pure FVW, maximum for pure PM, and clearly identifies digestate handling as the dominant emission source. Overall, the CHP-only configuration emerges as the most financeable option at this scale, and emphasis on closed digestate management is recommended to minimize emissions.

1. Introduction

Anaerobic digestion (AD) has become an established waste-to-energy technology, transforming high-moisture organic residues into biogas and nutrient-rich digestate [1,2]. The process is widely applied to divert waste from landfills and generate renewable biogas. In South Africa, where roughly 77% of electricity comes from coal, low-carbon biogas offers large climate benefits [3]. A South African life cycle assessment (LCA) found that coal-fired power’s burdens, climate change, fossil depletion, particulate formation, toxicity, etc., are over 90% higher than those for comparable biomass gasification routes [3]. This underscores the value of replacing coal-derived electricity with biogas-derived power in a coal-heavy grid. In addition to waste valorization and energy recovery, AD enables nutrient recycling: the digestate co-products substitute for synthetic fertilizers (P2O5, K2O, and N), cutting impacts from the manufacture and use of fossil-based chemical fertilizers [4].

Common to farms and fresh produce markets, a key resource is mixed organics like fruit-and-vegetable waste (FVW) and animal manure. These organics are candidate substrates for commercial biogas digesters. For example, a Johannesburg Market study demonstrated that mono-digestion of FVW at 45 t/day with full biomethane upgrading was feasible and profitable (16.9% IRR) while avoiding 12,400 t CO2-eq/year [5]. In practice, blending manures with carbohydrate-rich wastes is known to buffer pH, balance the C/N ratio, and boost methane yield [6]. Studies note that co-digestion dilutes inhibitors and synergistically enhances microbial activity, resulting in higher biogas production [7]. This suggests that combining poultry manure (PM) with market waste (FVW) can improve process stability and energy output [8].

Biogas can be used on-site to produce both heat in the form of hot water and electrical power (CHP). Alternatively, biogas can be upgraded to biomethane for subsequent injection into the gas grid or for transport fuel usage. As part of upgrading, carbon dioxide is produced as a side stream which can be used in producing additional fuels instead of being emitted as a GHG [9,10]. Techno-economic analysis (TEA) and LCA studies show that the optimal route is highly sensitive to the grid’s carbon intensity, electricity price, and system efficiency. For instance, Collet et al. [11] found that power-to-gas (CO2 methanation) becomes more competitive only when electricity is cheap or the plant capacity factor is high. Likewise, the environmental ranking of a combined heat and power (CHP) system vs. upgrading shifts if the local electricity mix or methane slip rate changes. In farm-scale analyses, it is common to assume 35–40% electrical and about 50% thermal efficiency for biogas CHP units, and to use conversion factors (2.1 kWhe per m3 biogas, 10 kWhe per m3 CH4) for baseline energy balances [12,13].

Digestate management commonly dominates acidification (AP) and eutrophication (EP) impacts because storage and spreading cause NH3 volatilisation and N2O emissions [4,14]. Improved practices—covered storage, higher-solids handling, solid–liquid separation or composting—substantially reduce these losses. Crediting digestate for substituting mineral fertilizer (N, P2O5, K2O) further reduces multiple impact categories. For example, using digestate in place of synthetic fertilizer reduces the environmental burden of fertilizer production [15,16]. Current practice in the LCA studies of AD systems uses an attributional approach with system expansion: exported electricity displaces national grid power, biomethane displaces natural gas, and nutrient credits are given for avoided synthetic fertilizers [4]. The CML: Institute of Environmental Sciences (Leiden University) Impact Assessment (baseline) method, 100-year Global Warming Potential (GWP100), AP, EP, Photochemical Ozone Creation Potential (POCP), abiotic depletion, is commonly employed for biogas LCAs to allow consistency and comparability [17].

Despite advances in South African biogas research, particularly feedstock studies on market-waste digestion and energy-system LCAs that quantify coal’s disadvantage, gaps remain for farm-scale AD. Masebinu et al. [5] biogas work on Johannesburg market waste focused on FVW alone, leaving unanswered how co-digestion with poultry manure would alter yields, costs, and emissions. Likewise, South African LCAs have highlighted coal’s disadvantage but rarely modelled farm-based AD with explicit digestate credits in regions such as the Free State. Also, combined techno-economic–environmental analyses that compare biogas use in CHP vs. upgrading under a coal-heavy grid, testing sensitivity to grid carbon factor and operation hours, are scarce, even though these factors often dominate outcomes [11].

Recent literature highlights that certain agricultural and food-related residues can be upcycled into higher-value cellulosic products (e.g., natural cellulose fibres and dissolving pulps) using mechanical, enzymatic or mild chemical routes, and that these material-valorisation pathways can, under favourable conditions, yield greater unit value than energy recovery; however, they typically require clean, homogeneous feedstocks, significant preprocessing (sorting, drying, solvent/water management), and support infrastructure that limits their applicability to mixed, high-moisture urban food and vegetable waste streams. For this reason, while such cascaded-use options are important to recognize in a circular-economy framing and should inform feedstock prioritization, they do not invalidate the present focus on anaerobic digestion for the mixed and moisture-rich feedstocks examined here; AD remains the most practical route where collection, sorting, and feedstock quality are limited. We therefore acknowledge material valorisation as a complementary pathway to be considered in integrated waste-resource planning and refer the reader to recent upcycling reviews for further detail [18].

This study models a hypothetical farm-scale mesophilic wet AD plant in Bloemfontein, Free State, South Africa, processing 50 t/day that operates at a 30-day retention time. Five feed scenarios are defined: PM100 (100% poultry manure), FVW100, PM20-FVW80, PM50-FVW50, and PM70-FVW30. Three energy-use cases are compared: 100% electricity via CHP (100% E); 50% electricity via CHP + 50% biomethane (50/50); and 100% biomethane upgrading (100% B), with CO2 venting. The scenario definitions and system boundary are described under the methodology section. The TEA in a 20-year cash-flow model, reporting capital expenditure (CAPEX), operating expenses (OPEX), net present value (NPV), internal rate of return (IRR), debt service coverage ratio (DSCR), etc., and an LCA, attributional, CML-IA midpoints, for each case were modelled. Key assumptions are chosen to match regional engineering data and literature norms. Digestate nutrient substitution (N, P2O5, K2O) is explicitly included to capture avoided fertilizer impacts [4]. The study benchmark assumptions, e.g., 40% electrical efficiency, against published values and drawing on comparative studies [11,13,17].

This study makes four main contributions. First, it presents the first farm-scale TEA–LCA of PM–FVW co-digestion in South Africa, reporting decision-relevant indicators (NPV, IRR, DSCR, and CML-IA midpoint impacts). Second, it explicitly quantifies the trade-off between CHP and upgrading pathways under a coal-dominated electricity grid, including sensitivity to grid carbon intensity and plant capacity factor. Third, it incorporates digestate nutrient credits for phosphorus, potassium, and nitrogen to reflect the substitution of synthetic fertilizers. Finally, the results are contextualized within South Africa’s bioenergy landscape, where biomass-based pathways consistently outperform coal-fired electricity on a life-cycle basis. Collectively, these contributions provide rigorous, locally relevant evidence to support farmers, investors, and policymakers in the siting and design of anaerobic digestion projects in the Free State and comparable regions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area, Functional Unit, and Scenarios

The hypothetical facility is a greenfield anaerobic digestion plant on a farm in Bloemfontein, Free State, South Africa. The functional unit (FU) for the LCA is 1 ton of as-received substrate delivered to the reception unit. The plant is sized for 50 t/day (wet basis) at 30 days hydraulic retention time (mesophilic wet AD). Transport to the site is assumed: one-way 20 km by rigid truck for both poultry manure and FVW. Five digestion scenarios are considered: PM100 being 100% poultry manure monodigestion, FVW100 being 100% fruit-and-vegetable waste monodigestion, PM20–FVW80 being co-digestion of 20% PM and 80% FVW, PM50–FVW50 being co-digestion of 50% PM and 50% FVW, PM70–FVW30 being co-digestion of 70% PM and 30% FVW. The % values are on a wet mass basis.

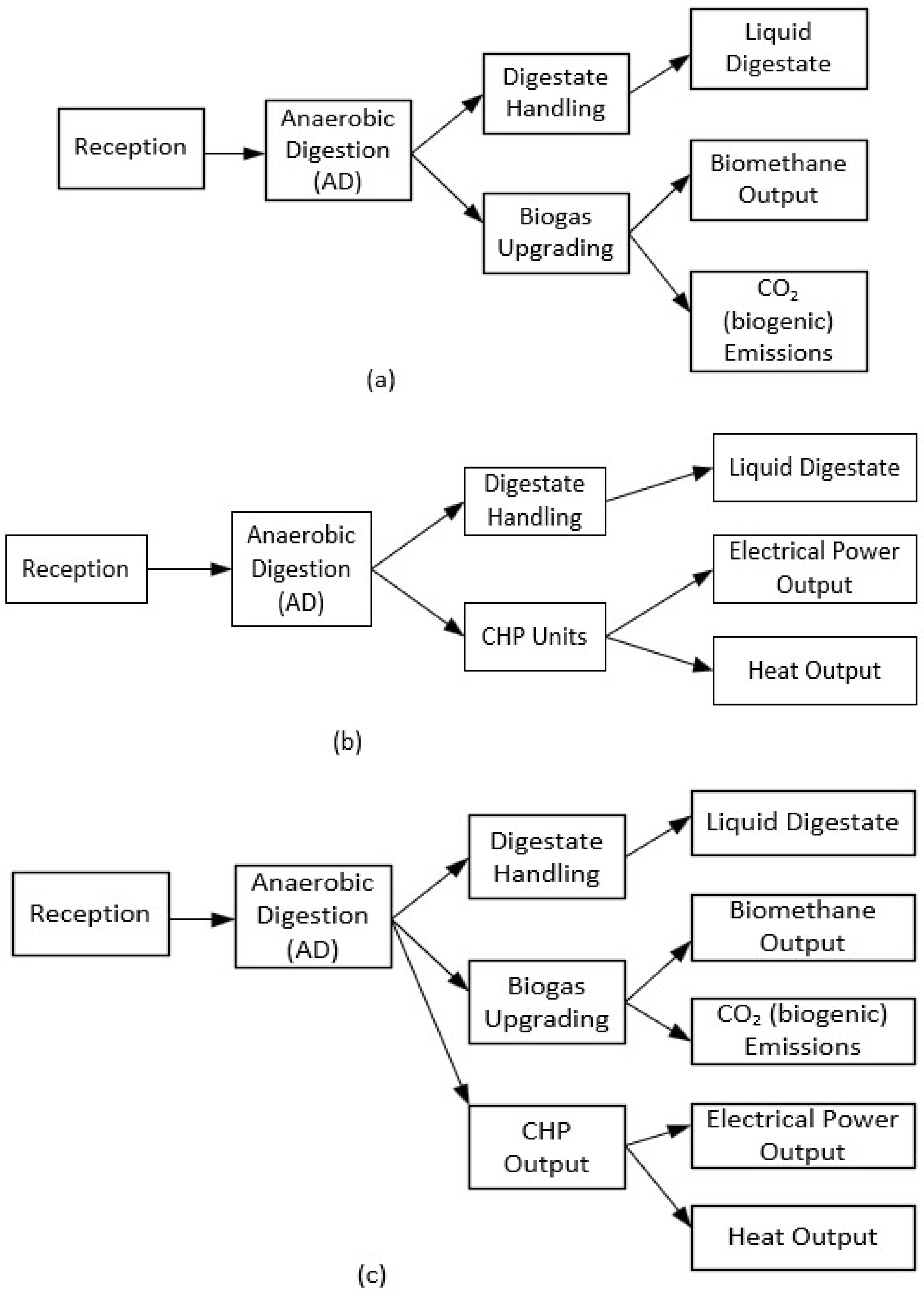

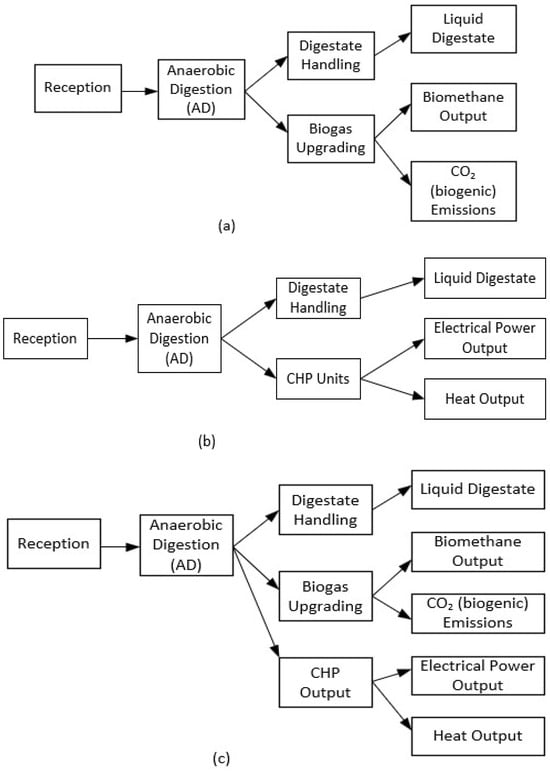

Three energy utilization pathways were evaluated: (a) 100% biogas burned in CHP (with on-site heat use); (b) 50% CHP + 50% upgraded to biomethane; and (c) 100% upgrading to biomethane (with biogenic CO2 vented). The system flow for each case is given in Figure 1. Electricity and biomethane outputs are normalized per FU for comparison, because South Africa’s grid is coal-dominated (77% coal), substituting grid power with biogas electricity/biomethane yields substantial carbon savings [3].

Figure 1.

Modelled AD process chains: (a) biogas upgrading; (b) CHP; (c) hybrid.

2.2. System Boundary and Modelling Framework

The LCA is cradle-to-gate with credits. It includes feedstock reception (weighing, shredding), anaerobic digestion (mixing, heat to maintain 37 °C), energy conversion (either CHP or upgrading as per scenario, with CO2 venting in upgrading cases), and digestate handling (dewatering, storage, land application). Imported materials (water, electricity) and fuel use are in the foreground system. All co-products are credited by system expansion: exported electricity displaces South African grid power; biomethane displaces fossil natural gas (on a 1:1 energy basis); and digestate credits are given for avoided synthetic fertilizer (P2O5, K2O, and N content). This substitution approach is standard in LCA studies for AD systems [4]. The CML-IA baseline impact method is used (midpoint categories: GWP100, acidification, eutrophication, photochemical ozone creation, abiotic fossil depletion) for consistency with prior studies [17].

Figure 1 illustrates the three assessed process chains and the associated system boundaries. The analysis includes feedstock collection (limited to a 20 km transport radius), anaerobic digestion, biogas handling, energy conversion or upgrading, digestate storage, and land application. Processes excluded from the system boundary include CO2 valorisation and sulfur recovery from biogas, as these options are site-specific, technologically immature at farm and community scale in the South African context, and would introduce additional capital and market assumptions that could obscure comparison between pathways. Their exclusion, therefore, represents a conservative assumption for upgrading pathways. Transport logistics beyond 20 km were excluded to reflect typical catchment distances for farm-scale digesters and to avoid overstating transport-related impacts; longer-distance logistics are discussed qualitatively as a limitation.

Parasitic electricity consumption was explicitly accounted for and differs by pathway: CHP configurations include auxiliary loads for mixing, pumping, and gas handling, while upgrading configurations additionally include electricity demand for gas compression and separation. These loads are reflected in the net electricity or biomethane outputs reported. Thermal energy from CHP was assumed to be partially utilized for digester heating and on-site processes, with any surplus heat considered unrecovered due to the absence of guaranteed local heat demand; thus, no credit was applied for excess heat export. This assumption is conservative and avoids overestimating the performance of CHP systems while improving the reproducibility of techno-economic and environmental results.

2.3. Techno-Economic Analysis

2.3.1. Framework and Financial Parameters

The TEA is a 20-year real-discounted cash flow model (Excel-based), customized per scenario. It estimates total CAPEX, OPEX, revenues, Levelized Cost of Energy, and financial metrics (NPV, Project IRR, Equity IRR, payback period, debt-service coverage ratio). Key financial assumptions are: 10% real discount rate, 27% corporate tax, 60:40 debt equity, 8% real interest on debt (15-year term), and 15% cost of equity. Baseline prices are ZAR 1600/MWh for electricity, ZAR 6/Nm3 for biomethane, and ZAR 100/ton for digestate (wet) [12,19].

2.3.2. Capacity and Energy Balances

The plant capacity is 50,000 kg/day on as-received feed (wet basis). For the wet, mesophilic CSTR system, the digester working volume is dictated by the hydraulic retention time (HRT) and daily slurry feed rate. At a design throughput of 50 t d−1 (assuming slurry density is 1 kg L−1) and an HRT of 30 days, the resulting working volume is approximately 1500 m3. The digester volume aligns with some previous studies. Maluta et al. [20] analyzed the hydrodynamics and scale-up of an industrial stirred anaerobic digester with a reference volume of 1500 m3, describing this geometry as representative of typical agricultural and waste-based biogas plants operating under wet conditions. Ahlberg-Eliasson et al. [21] report full-scale mesophilic digesters treating cattle and poultry manure with active volumes of 1000–1300 m3 and HRTs of 22–30 days, confirming that such reactor sizes are standard practice rather than exceptional.

Energy demands in each section of the plant per ton of substrate processed (from engineering data) are reception/shredding 21.4 kWhe/t, digester mixing 2.16 kWhe/t, upgrading (when used) 20.9 kWhe/t, and digestate handling 17.96 kWhe/t. For CHP, electrical efficiency of 40% and thermal efficiency of 50% are assumed (industry-typical values for biogas engines) [12,13,19,22]. Using this data, the model calculates net exported electricity (after on-site loads and digester heating). For the PM100 case, the baseline yields 200 kWhe exported per ton of substrate, which validates our balance against literature values (2.1 kWhe per m3 biogas, 10 kWhe per m3 CH4). Assuming the raw biogas is 60% CH4 and 40% CO2 (v/v) and a 2% CH4 slip in upgrading, the expected outputs per 1 t of as-received substrate are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Expected per-ton outputs by blend scenario (as-received substrate).

2.3.3. CAPEX and OPEX Structure

Capital costs are grouped into in-plant equipment (ISBL: digesters, CHP engine or upgrader, shredders, pumps, etc.), off-site works (OSBL: civil works, power interconnection, utilities), and indirects (engineering, contingency). In the base cost model, OSBL is 40% of ISBL; contingency is 10% of (ISBL + OSBL); and EPCM is 12% of the total installed cost. This breakdown is consistent with standard biogas project costing in recent studies [19].

Operating costs include fixed labour and maintenance, and variable costs for utilities, consumables (e.g., chemicals, adsorbents), and feedstock or transport fees. Feedstock for FVW is modelled as a negative cost (gate fee) of −ZAR 500/t (municipal tipping credit), while poultry manure incurs a haulage cost of ZAR 120/t. The gate-fee credit represents avoided municipal landfill disposal charges and potential incentives for diversion. This value is consistent with published South African municipal landfill gate fees reported at approximately ZAR 500–ZAR 692 t−1 (2021–2025) for the eThekwini Municipality [23]. Sensitivity cases were run for gate fees, in addition to the baseline –ZAR 500/t for FVW. The gate fee for the FVW varied from −ZAR 400/t to −ZAR 700/t. Also, assumptions for labour (ZAR 1.5 M/yr.), maintenance (3% of ISBL/yr.), utilities (ZAR 0.9 M/yr.), chemicals (ZAR 0.5 M/yr.), and insurance/taxes (1% of TIC/yr.) were made [24,25,26,27]. Revenue streams in the cash flow are from electricity sales (in CHP routes), biomethane sales (in upgrading routes), and digestate sales (linked to LCA credits).

Potential revenues from recovered CO2 (associated with biogas upgrading) and sulfur-containing by-products from H2S removal were excluded from the base-case techno-economic analysis. This exclusion reflects a deliberate conservative modelling choice, as monetization of these streams depends on site-specific assumptions regarding gas purity, compression or conditioning requirements, storage, logistics, and secure offtake agreements, which are difficult to generalize. Importantly, omitting these revenues biases results against upgrading (biomethane) pathways and therefore represents a lower-bound estimate of their economic performance relative to CHP-based electricity production.

2.3.4. Economic Modelling Equations for the TEA

Economic modelling equations were used to implement the TEA in Office 365 MS Excel for the AD plant. All costs taken from earlier years were first updated to the study year (2025) using the Chemical Engineering Plant Cost Index (CEPCI). The adjustment formula is given by Equation (1), which ensures all costs are in consistent-year dollars.

where is the cost in the reference year (2023);

- is the CEPCI value for the reference year (2023);

- is the CEPCI value for the study year (2025).

The NPV was calculated by discounting all future cash flows back to time zero using Equation (2). A positive NPV indicates the project is profitable over its lifetime.

where is the initial investment (CAPEX);

- is the net cash flow in the year (OPEX and revenues);

- is the discount rate;

- is the project lifetime.

The IRR is the discount rate that makes the NPV equal zero. It is defined by solving Equation (3). In other words, IRR satisfies the condition that the present value of all cash flows equals zero. A project is typically considered attractive if exceeds the hurdle rate (required return).

The payback period is the time required to recover the initial investment (CAPEX) from cash flows, in its simplest form (constant annual cash flow). Payback ignores the time value of money but provides a quick measure of liquidity risk. The payback period is obtained by Equation (4).

The DSCR measures the ability to cover debt payments. This is defined by Equation (5). A DSCR ≥1 means sufficient cash flow to meet debt.

where “cash flow available” typically equals net operating cash flow (before debt payments);

“Debt service” refers to the principal plus interest due in a given year;

The NPV and IRR are standard discounted cash flow metrics, payback is a simple investment recovery time, and DSCR is a financing ratio for loan feasibility.

2.3.5. Sensitivity Analysis Framework

A sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the robustness of the techno-economic results to uncertainty in key market and financial parameters. A one-at-a-time approach was applied, in which individual parameters were varied independently around their base-case values while all other inputs were held constant. The analysis focused on NPV, with implications for IRR and DSCR interpreted accordingly. The selected parameters, electricity tariff, biomethane selling price, and discount rate, represent the principal sources of economic uncertainty for anaerobic digestion projects under South African conditions and were evaluated consistently across all feedstock mixing ratios and utilization pathways (CHP, hybrid, and biomethane).

Sensitivity results were visualized using tornado diagrams, showing the resulting change in NPV (ΔNPV) relative to the base case for each parameter. This approach enables comparison of the relative importance of revenue and financing assumptions under conditions of energy price volatility. Parameters producing negligible changes in NPV were omitted from the plots for clarity. Uncertainties related to methane slip during upgrading and digestate nutrient composition were addressed separately within the life cycle assessment and digestate management scenarios, as these factors primarily affect environmental performance rather than project cash flows.

2.4. Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA)

2.4.1. Goal and Scope

The LCA objective is to quantify midpoint environmental impacts for each scenario and identify hotspots (e.g., the effect of digestate). The study is ISO-compliant and attributional. The OpenLCA 2.5.0 software package was used for the LCA. Impacts are reported per FU (1 t substrate) for comparability. Midpoints calculated include GWP100, AP, EP, POCP, and fossil depletion (CML-IA baseline).

2.4.2. Foreground System and Functional Unit

The FU is 1 t (as-received) feedstock delivered to reception. Foreground processes (with their inputs and outputs) are modelled as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

LCA foreground processes with inputs and outputs.

2.4.3. Background Data and Substitution Credits

Background inventories (electricity mix, fuel combustion, fertilizer production, trucking) are drawn from standard LCA databases (e.g., Agri-footprint, BioEnergieDat, Ecoinvent, PSILCA, etc.). For displaced grid electricity, the South African mix data was used. The biomethane energy credit is based on energy equivalence to natural gas. Digestate substitution credits use measured P and K content (converted to P2O5, K2O); nitrogen credits are included where reliable data exists. Following common practice, the assumption of direct substitution by nutrient content was made [4,15,16].

Digestate nutrient credits were applied using a direct substitution approach based on plant-available nutrient fractions rather than total nutrient content. Phosphorus and potassium were assumed to be largely plant-available following land application, while nitrogen availability was treated more conservatively to account for volatilisation and handling losses. Blend-specific nutrient concentrations were used where measured, and uncertainty associated with spatial variability and digestate quality was represented through bounded availability ranges applied uniformly across scenarios. Potential reductions in nutrient credit resulting from post-treatment practices such as dewatering or composting were explored through sensitivity and scenario analysis by applying reduced nitrogen availability factors, while phosphorus and potassium credits were largely preserved. The use of direct substitution is justified in the South African context, where digestate is commonly applied to nearby agricultural land to offset purchased mineral fertilizers, making avoided fertilizer production and application an appropriate and transparent representation of environmental benefit within an attributional life-cycle assessment framework.

2.4.4. Key Parameters and Emission Factors

Other key inputs to the LCA calculations include: 20 km truck transport costs (one trip) for feedstock; CHP electrical/thermal efficiency of 40/50%, respectively; and biogenic CO2 emissions treated as climate-neutral in combustion [22]. For upgrading, an assumption of typical methane slip rates (1–2%) from vendor data is included, and sensitivity is considered. Digestate stage emissions are modelled using literature ranges (storage, handling and transfer, and separated-solid management): NH3 volatilization, N2O emissions, and small CH4 leaks depend on C and N content as well as digestate handling systems. These parameters are particularly influential for AP and EP [28,29]. The AP is an LCA midpoint indicator that expresses how emitted substances can form acids in the atmosphere and deposit to soils and waters, lowering pH and harming ecosystems. The EP is an LCA midpoint indicator for nutrient enrichment of aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, which can trigger algal blooms and oxygen depletion. Typical sources of AP are coal, industrial boilers, fertilizers, and livestock, while those of EP are wastewater effluents, food and organic waste leachate, fertilizers, and manure/digestate.

Emissions from digestate storage and land application were calculated using standard IPCC Tier 1 emission factors for organic fertilizers. In the model, 25% of the applied digestate nitrogen is assumed to volatilize as ammonia (NH3–N), 1% of applied nitrogen is emitted as direct nitrous oxide (N2O–N), and 1% of the volatilized NH3–N is emitted as indirect N2O–N [30,31]. These emission factors were applied to the measured nitrogen content of the digestate to compute total NH3 and N2O emissions on a mass basis. A stepwise worked example of these calculations is provided in Appendix D, illustrating how the emission totals are obtained for a representative digestate scenario.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Techno-Economic Analysis

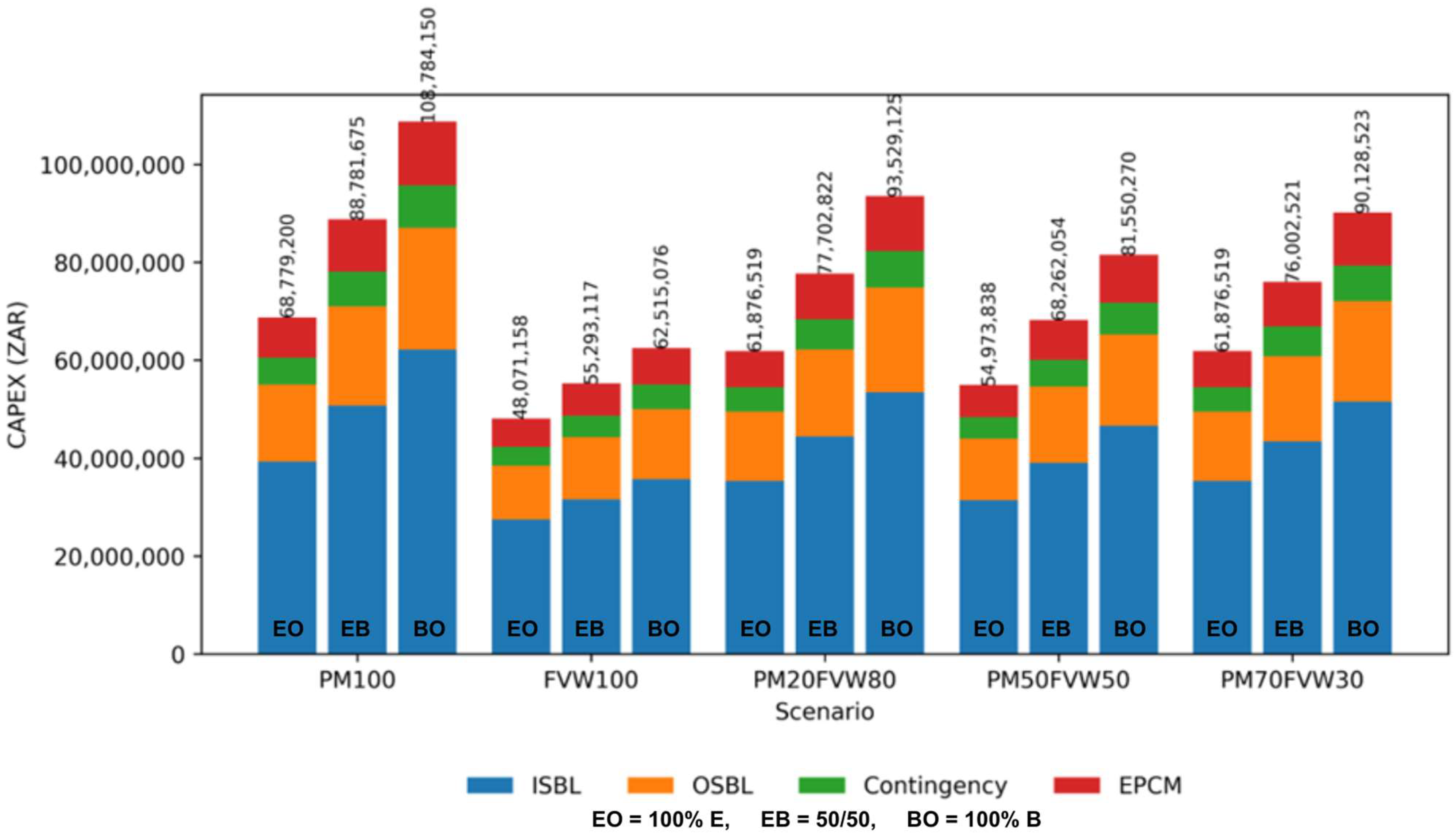

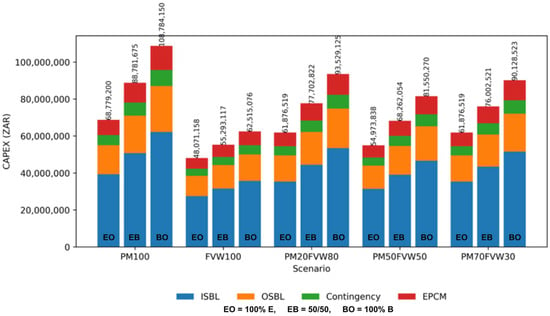

The CAPEX breakdown by scenario and energy split is provided in Figure 2. This shows stable cost shares set by our rules (OSBL = 40% of ISBL; Contingency = 10% of ISBL + OSBL; EPCM = 12% of TIC), so variation is dominated by ISBL modules (digesters, and when selected upgrades) rather than by routing per se. Across routes within a blend, moving from 100% electricity to 100% biomethane raises TIC by 30–58% (hybrid sits almost exactly mid-way), consistent with the added upgrader, gas cleaning, and compression trains (e.g., PM70–FVW30: 100% E (61.9 M ZAR), 50/50 (76.00 M ZAR), and 100% B (90.1 M ZAR); The difference between the 100% E and 100% B is 28.3 M ZAR). Across blends, minimum TIC occurs at FVW100-E (48.1 M ZAR) and maximum at PM100-B (108.8 M ZAR), a 126% span that tracks methane throughput and thus upgrader size. This is consistent with Table A1 methane capacities (FVW100 lowest, PM100 highest), which sets equipment sizing. For the base composition (PM70–FVW30, 100% B), TIC = 90.13 M ZAR with shares ISBL 57.1%, OSBL 22.9%, Cont. 8.0%, EPCM 12.0%; normalized to 75.7 Nm3 h−1 CH4 this gives 1.19 M ZAR (Nm3 h−1)−1, used for specific-CAPEX reporting.

Figure 2.

CAPEX breakdown by scenario and energy split (ISBL, OSBL, contingency, EPCM).

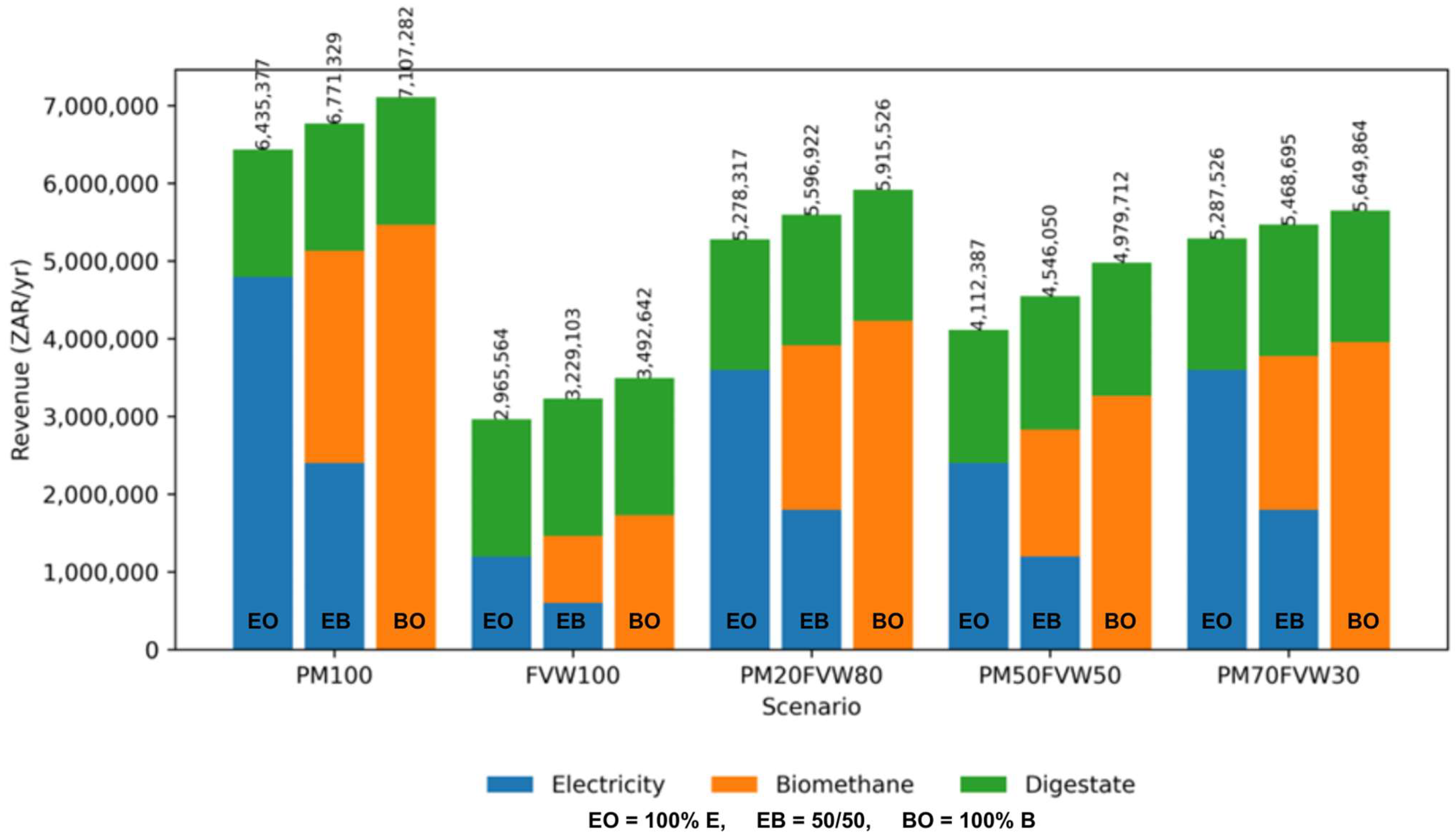

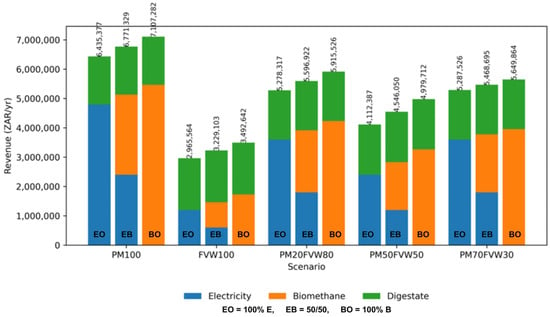

The revenue stacked by scenario is shown in Figure 3. This stacks product revenues by route. Within each blend, 100% biomethane is greater than 50/50, and 50/50 is also greater than 100% electricity because the biomethane sales price exceeds the electricity tariff. The uplift from electricity to biomethane is 7–22% across blends (largest at PM50–FVW50). Across blends, totals scale with methane output (PM-rich mixes highest, FVW100 lowest). Digestate revenue is invariant to routing within a blend (same mass produced) and contributes a material 20–30% of the top line, providing a stabilizing second stream. Bars include product revenues only (electricity, biomethane, digestate). The gate-fee (500 ZAR t−1) is treated as a negative OPEX, in the stacks, but included in cash-flow/NPV analyses. Annual O&M (ex-feedstock) totals 7.54 M ZAR yr−1, equivalent to 317 ZAR GJ−1 (1141 ZAR MWh_th−1).

Figure 3.

Revenue composition by scenario (stacked bars) for 100% E, 50/50, and 100% B.

When the FVW gate fee was varied between −400 and −700 ZAR/t, the IRR ranges were 5.1% to 16.5%, 3.8% to 14.4%, and 2.7% to 12.7% for 100% E, 50/50, and 100% B, respectively, for FVW100. For PM70FVW30, the IRR ranges were 6.8% to 15.5%, 4.2% to 12.2%, and 2.0% to 9.7% for 100% E, 50/50, and 100% B, respectively. The gate fee of −400 ZAR/t resulted in the least IRR across all the scenarios. These results indicate that project bankability is moderately sensitive to tipping fees, underscoring the importance of securing waste credits.

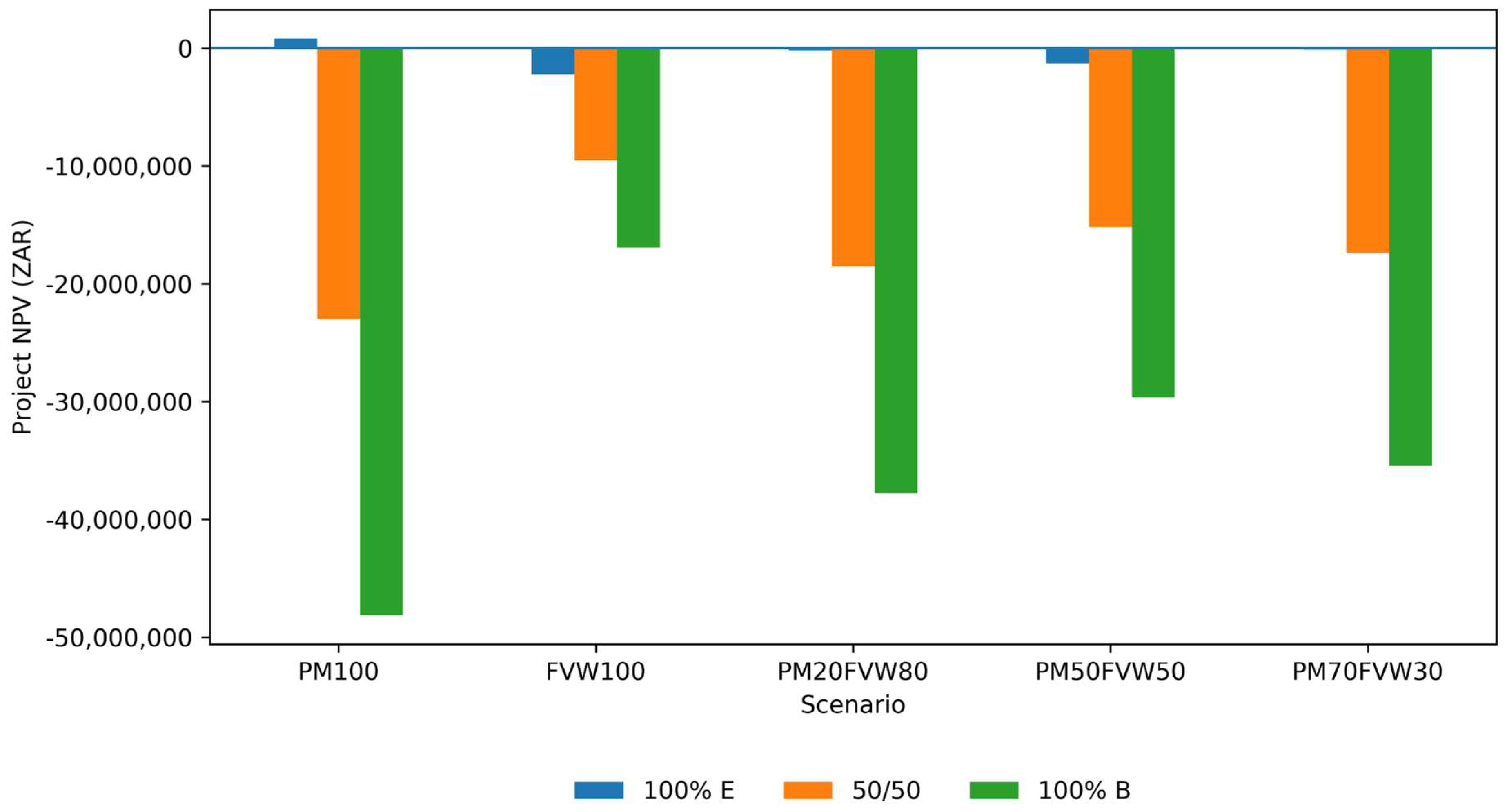

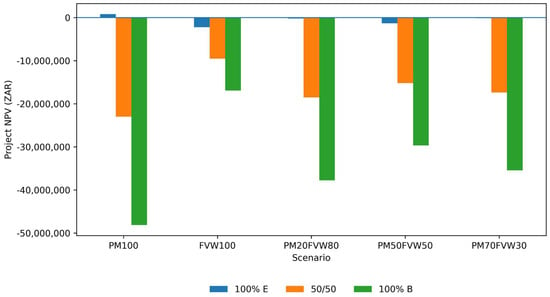

Figure 4 reports the project NPV, discounted at r = 10%, over a 20-year life. At base prices, 100% biomethane (100% B) options are most negative (−30 to −48 M ZAR across blends), 50/50 routes are intermediate (−10 to −25 M ZAR), and several 100% electricity (100% E) variants lie near breakeven (some slightly negative/positive). This ordering is consistent with Figure 3: biomethane raises revenue, but the added upgrader, gas cleaning, and compression CAPEX/OPEX more than offset that uplift at baseline prices.

Figure 4.

Project NPV by scenario (clustered bars: 100% E, 50/50, 100% B).

Considering the bankability KPIs (Table 3). The same pattern holds for IRR and DSCR. Across blends: 100% E: Project IRR 9.46–10.13%, Equity IRR 28–29.7%, Year-1 DSCR 3.39–3.50, min DSCR 2.39–2.46. 50/50: Project IRR 6.85–7.94%, Equity IRR 23.5–25.5%, Year-1 DSCR 3.01–3.18, min DSCR 2.12–2.23. 100% B: Project IRR 4.35–6.69%, Equity IRR 18.9–23.2%, Year-1 DSCR 2.61–2.98, min DSCR 1.84–2.11.

Table 3.

Consolidated financial and bankability KPIs by AD scenario × biogas utilization routing.

The 100% E shows the strongest DSCR headroom and highest IRR; 50/50 is intermediate; 100% B has the thinnest DSCR headroom (min DSCR = 1.84–2.11), with some blends dipping below 2.0. The pair of Figure 4 and Table 3 conveys a consistent message: at baseline tariffs/prices, CHP-only is the most bankable configuration, while gas-led routes would require a higher biomethane price/guaranteed offtake, or CAPEX support, to cross NPV ≥ 0.

The financial analysis shows that electricity-led configurations (100% E) consistently outperform biomethane-oriented ones (100% B) in terms of returns and bankability. Within each energy utilization route, blends rich in FVW outperform PM-rich blends, reflecting the lower pretreatment demands and slightly higher energy yields of FVW mixtures. For example, the PM20FVW80 and PM70FVW30 scenarios under 100% E gave the highest project IRRs (10%) and minimum DSCRs (2.44) at 50 t/day, whereas all 100% B routes yield much lower IRRs (4–7%) and DSCRs (1.84–1.96). These 100% E DSCRs (Year-1 = 2.6–3.5) comfortably exceed typical lending thresholds (1.3–1.5), whereas the 100% B cases fall short under baseline assumptions. Thus, CHP-only operation is the most “bankable” base case, while 100% biomethane requires either higher gas prices or lower CAPEX (via larger scale) to be financially viable. These trends match prior South African TEA conducted by Masebinu et al. [5], a Johannesburg case achieved an IRR of 17% for 100% biomethane but required FIT subsidies for a viable CHP route. In Bloemfontein’s coal-heavy grid (0.99 kgCO2/kWh) and high liquid-fuel prices, hybrid (50/50) and biomethane-intensive schemes are expected to yield higher IRR than pure CHP, unless preferential electricity tariffs are available.

Robin and Ehimen [32] report that a small household-scale biogas project in Malawi (with co-digestion of cow dung and maize residue) achieved an IRR of only about 6% (and a payback of 5.3 years) for a large reactor, indicating marginal profitability. In general, biogas projects typically require higher IRRs (often on the order of 10–15%) to be attractive to investors and to exceed the cost of capital. Similarly, lenders usually demand DSCR values above unity (often >1.2) to consider a project bankable. If the calculated DSCR is below 1, the project may not generate enough cash flow to cover debt obligations without subsidies or equity injections. In other words, IRR must exceed the investor’s required return, and DSCR must exceed 1 (or a higher threshold) for the project to be financially sustainable. These criteria are consistent with the findings of other literature on renewable energy projects [33]. In this study, if the computed IRR is relatively low or the DSCR is near unity, this would suggest limited bankability under current assumptions. Achieving higher IRR and DSCR could require improving process efficiency, securing feedstock at lower cost, increasing revenues (e.g., via co-products or incentives), or extending the operational life. Overall, our TEA metrics should be contextualized by noting that many (especially small-scale) biogas projects struggle to reach conventional profitability benchmarks without supportive policies or revenue enhancements [32,33].

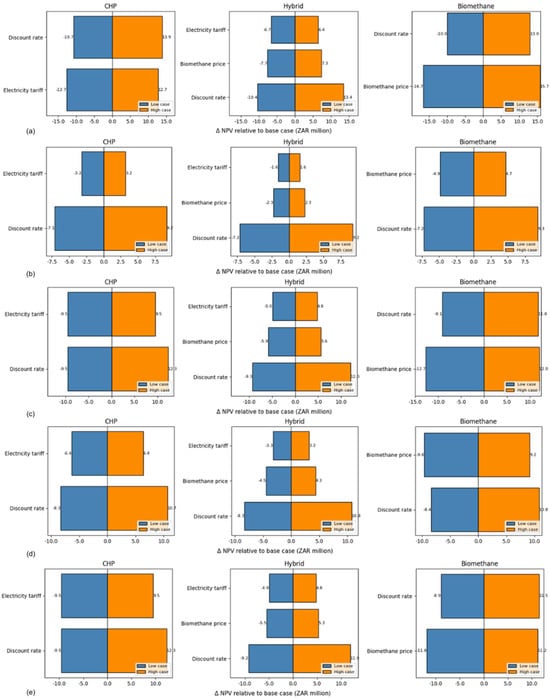

3.2. Sensitivity Analysis of Techno-Economic Performance

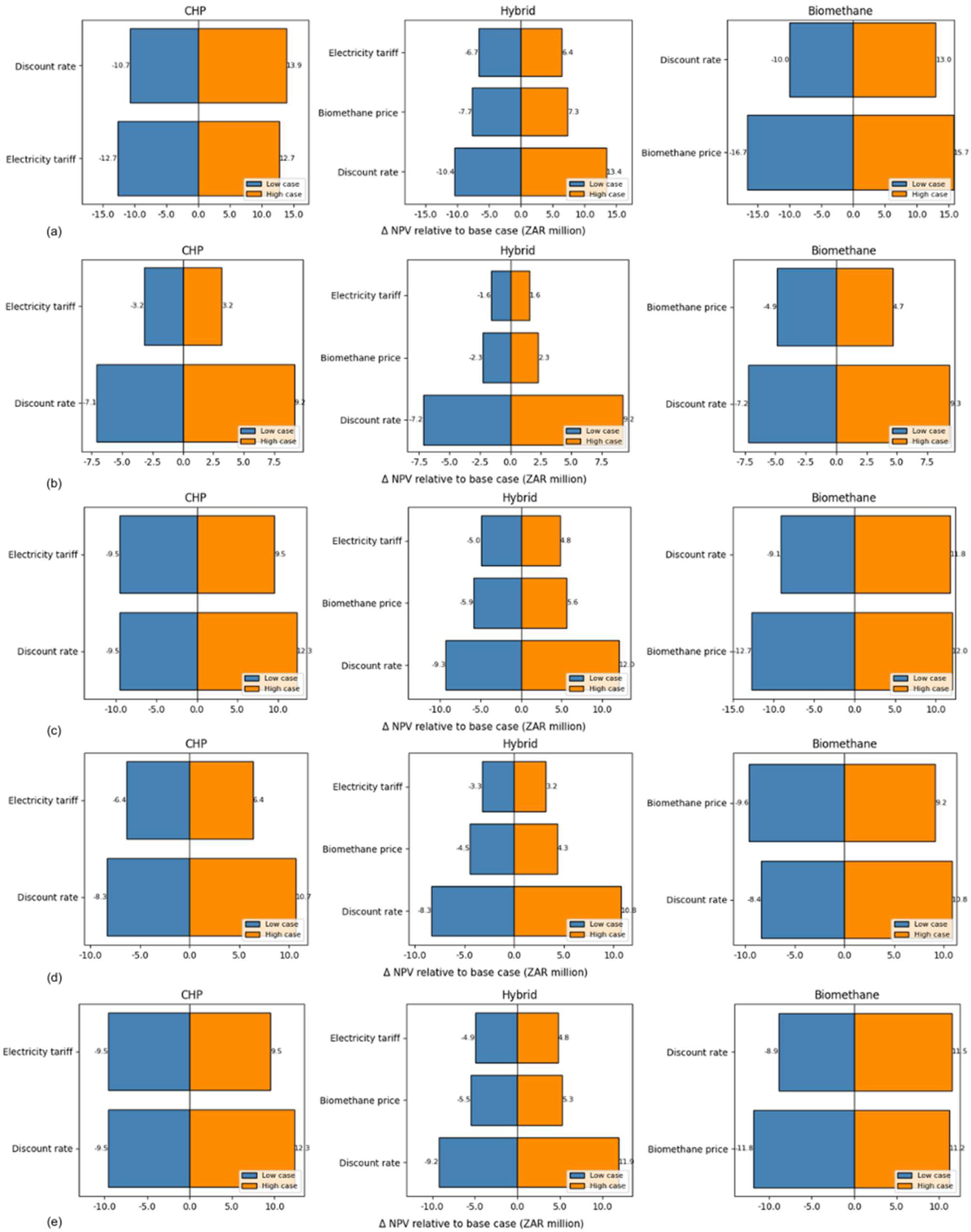

The sensitivity analysis (Figure 5) demonstrates that project NPV is dominated by uncertainty in revenue-related parameters, with the magnitude and source of sensitivity varying systematically by utilization pathway and feedstock mixing ratio. For CHP configurations (100% electricity), NPV is most strongly influenced by electricity tariffs across all blends, reflecting the direct coupling between electrical output and revenue. In contrast, biomethane-oriented pathways show their highest sensitivity to biomethane selling price, particularly for poultry-manure-rich blends (e.g., PM100 and PM70FVW30), where the absolute ΔNPV range is largest. Hybrid (50/50) pathways exhibit intermediate behaviour, with exposure split between electricity and gas prices depending on the underlying feedstock composition. Across all cases, variations in the discount rate produce a consistent but generally secondary impact on NPV, indicating that financing conditions affect absolute project returns without typically altering the relative ranking of pathways under base-case assumptions.

Figure 5.

Tornado diagrams showing the sensitivity of project net present value (NPV) to electricity tariff, biomethane selling price, and discount rate for five feedstock mixing ratios: (a) PM100, (b) FVW100, (c) PM20FVW80, (d) PM50FVW50, and (e) PM70FVW30.

Feedstock composition further moderates economic risk by influencing both revenue potential and sensitivity amplitude. Poultry-manure-dominated mixtures exhibit wider ΔNPV envelopes, indicating higher exposure to market volatility, whereas food-waste-rich scenarios (FVW100 and PM20FVW80) show comparatively narrower sensitivity ranges, suggesting greater economic robustness. Importantly, these results highlight that conclusions regarding the “most bankable” pathway are conditional on prevailing energy price assumptions: under current high electricity tariffs, CHP remains financially attractive, but sustained changes in electricity or biomethane prices could shift competitiveness toward upgrading-focused configurations. Consequently, risk-mitigation measures such as long-term power purchase or gas offtake agreements, conservative financing structures, and policy instruments that stabilize revenue streams are critical for improving bankability and may substantially influence long-term investment decisions beyond base-case techno-economic outcomes.

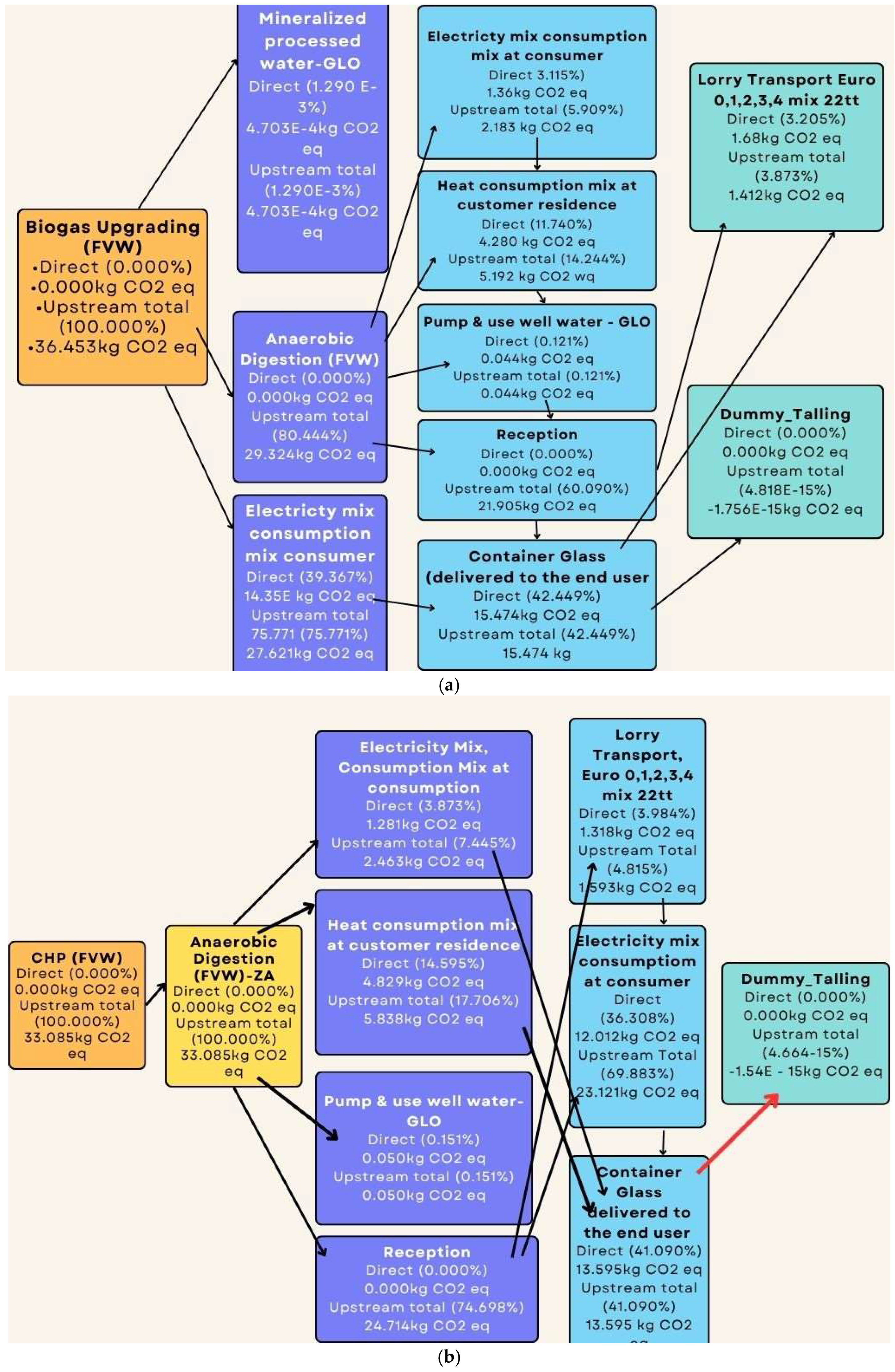

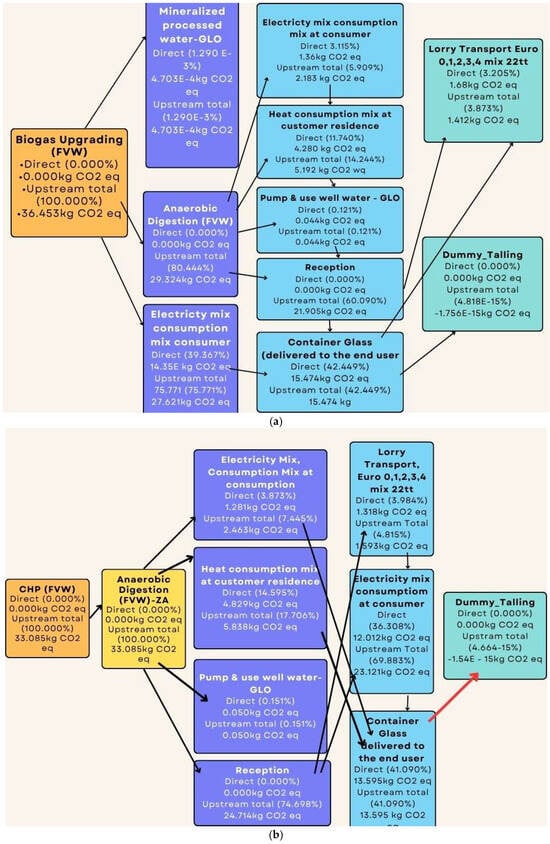

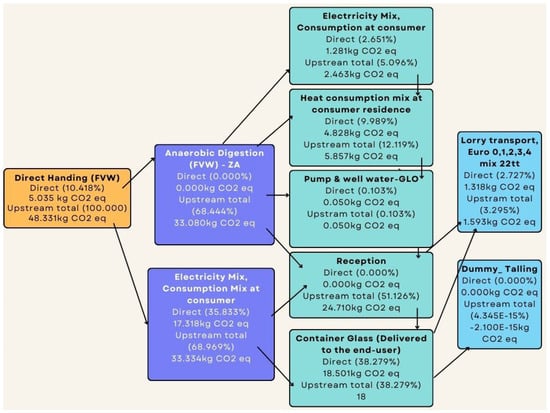

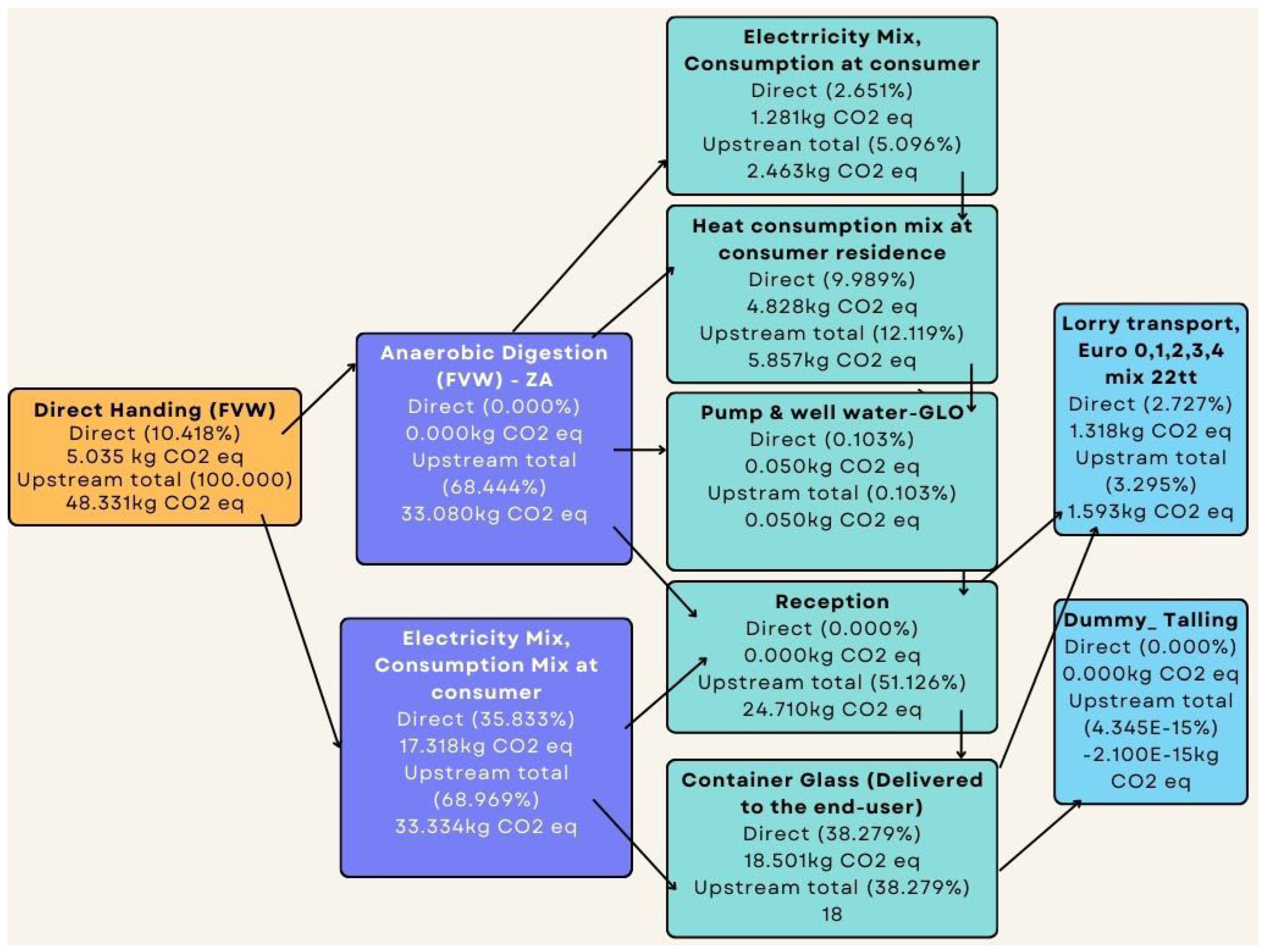

3.3. Life-Cycle Assessment

The process-level greenhouse gas (GHG) Sankey for the foreground modules of the biogas upgrading and CHP is shown in Figure 6. The process-level GHG flow for the digestate handling is shown in Appendix C (Figure A1). The qualitative pattern that emerges is consistent across all five substrate blends: digestate handling concentrates the largest share of GHG-relevant emissions and loss pathways (CH4, N2O, NH3 precursors), while energy modules (CHP or upgrading) contribute smaller, but still non-negligible, direct and indirect burdens through electricity and auxiliary use. This framing sets up the category results in Figure 7 and the multi-category comparison in Figure 8.

Figure 6.

Process-level GHG flow/Sankey (FU = 1 t of substrate as received) for (a) biogas upgrading, (b) CHP.

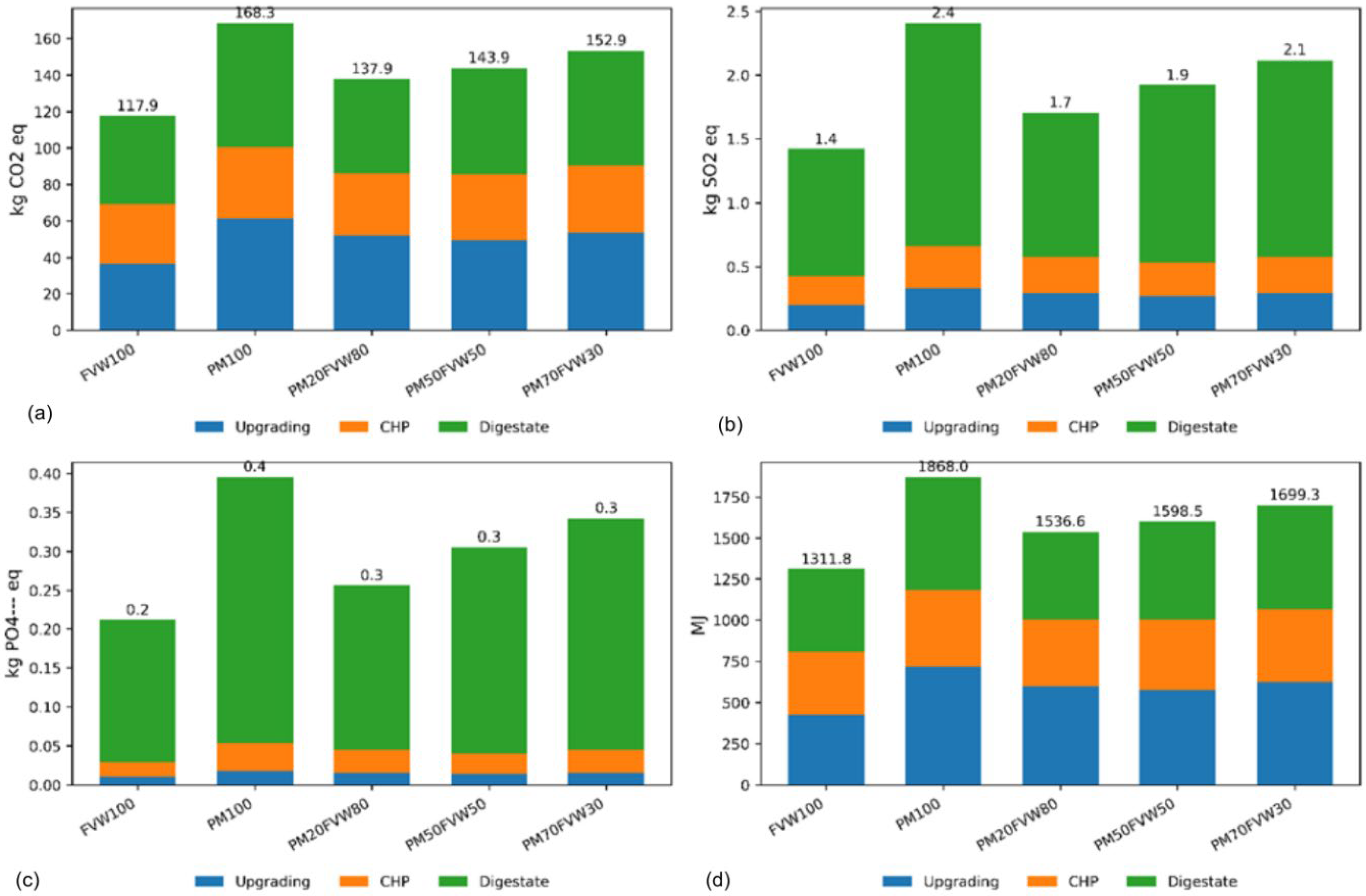

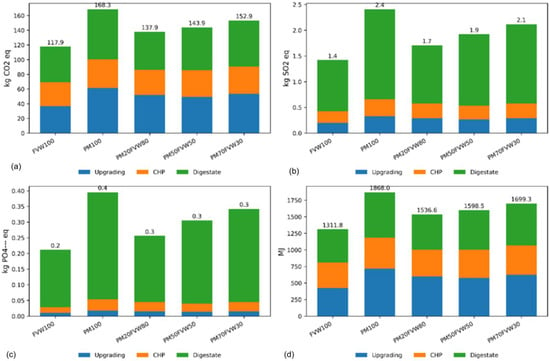

Figure 7.

Process contributions of a FU of 1 t of substrate (as received) per scenario: (a) GWP100, (b) acidification, (c) eutrophication, and (d) abiotic depletion (fossil).

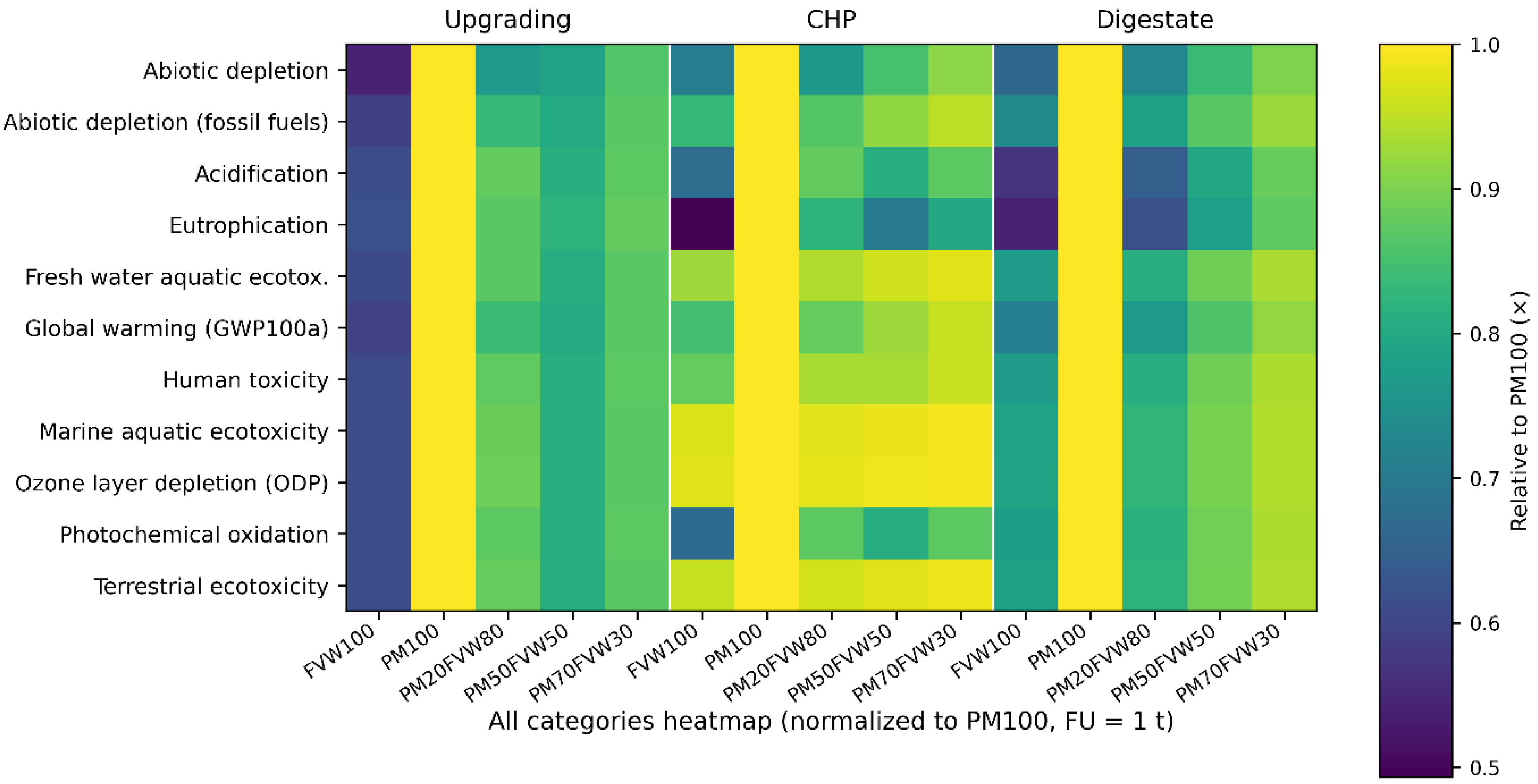

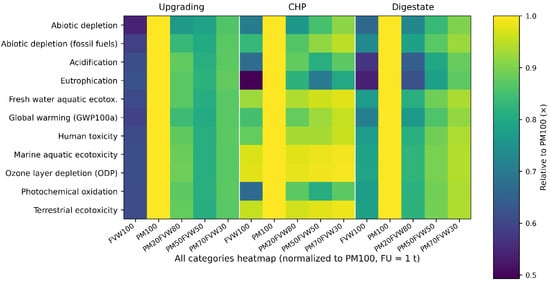

Figure 8.

All-category heatmap normalized to PM100.

Figure 7 reports process contributions to four midpoint categories per FU: (a) GWP100, (b) acidification, (c) eutrophication, and (d) abiotic depletion (fossil). The environmental results are driven overwhelmingly by digestate handling. Total system GWP (per 1 t feed) ranges from 118 to 168 kgCO2-eq, lowest under FVW100 and highest under PM100, with mixed blends in between. In every scenario and energy routing, the digestate module contributes the largest share of GWP, acidification, and eutrophication impacts, due to NH3 volatilization, N2O emissions, and fugitive CH4 from open storage/spreading. Energy modules (CHP or biogas upgrading) add smaller burdens: in climate terms, 100% E (CHP) yields large, avoided emissions by displacing coal power, whereas 100% B shifts credits to transport fuels (Figure 7). Nonetheless, even CH4 outputs from digestate override most credits.

Regarding abiotic depletion (fossil), all modules consume grid electricity and fuels, but in PM-heavy cases, the electricity-intensive upgrading chain (scrubbing, compression) can demand as much or more fossil energy as digestate treatment. CHP is consistently the smallest contributor to fossil depletion. The multi-category heatmap, Figure 8, confirms: FVW100 is the lowest-impact blend overall, and impacts generally increase with PM share (FVW100 < mixed < PM100 in almost every category). Notably, the ordering FVW100 < mixed < PM100 holds across all biogas utilization routes (100% E, 50/50, 100% B), with 100% E cases tending to be lower in GWP and fossil depletion due to grid displacement. There were no measured total-N concentrations for all digestate samples; hence, the higher digestate burdens reported for PM-rich blends are inferred from the known high nitrogen content of poultry manure and the nutrient patterns in Table A2, which are modelled in the LCA as emissions per unit N applied (see Appendix D).

As shown in Figure 7, the digestate storage and handling stage contributes the largest share of life-cycle impacts, particularly GWP, acidification, and eutrophication, due to ammonia and nitrous oxide emissions. Thus, effective mitigation of this hotspot can yield substantial benefits. Table A3 (Appendix E) summarizes these mitigation scenarios as percentage changes relative to the uncovered baseline; Appendix D provides the algebraic calculation and shows how values scale with applied nitrogen (kg N t−1). The results from the numerical calculation (Appendix D) and Table A3 (Appendix E) show that each mitigation measure substantially lowers acidification and eutrophication impacts (by 80–90%) while reducing GWP by roughly 15–30%. These findings are consistent with other studies, e.g., Kamp and Feilberg [31] report 92–95% NH3 and 82–89% N2O reductions under sealed stockpiles, and Quilez et al. [30] find 79–92% NH3 abatement via low-pH digestate. Thus, because the mitigation affects both biogas pathways equally, it can be concluded that the relative LCA ranking of CHP versus upgrading remains essentially the same under these improved scenarios.

These LCA patterns align with prior studies: open-field LCAs of AD systems repeatedly find digestate management to be the dominant hotspot. For example, Tan et al. [34] in their study shows that switching from uncovered to closed digestate storage can cut overall GWP by 90% by capturing fugitive CH4. The results obtained similarly indicate that acidified, tightly covered storage and off-gas treatment would yield the largest LCA benefits. Electricity decarbonization (e.g., on-site PV or green tariffs) for upgrading and auxiliaries is the next-highest lever, especially reducing abiotic-fossil impacts. Other levers include minimizing CH4 slip (tight maintenance, tail-gas oxidation) and favouring higher FVW blends where logistically feasible, since these lower all categories as observed.

Martin-Sanz-Garrido et al. [4] reviewed numerous LCA studies and found that open digestate storage can contribute up to 65% of the project’s total GHG emissions, while ammonia and nitrous emissions from digestate land application can account for nearly all (99%) of the eutrophication potential. Wang et al. [35] similarly reports that uncovered storage (e.g., open tanks at 20 °C) leads to very high methane conversion factors (42%), whereas covered or low-temperature storage can cut methane losses to 1%. This literature consistently notes that fugitive emissions of CH4 and NH3 from digestate handling dominate the life-cycle impacts. Therefore, the results obtained (showing digestate-driven emissions) align with these findings. To mitigate this hotspot, improved digestate management is crucial: strategies such as covering or injecting digestate into soil (instead of surface spreading), solid–liquid separation, and composting/separation have been shown to dramatically reduce emissions [4,35]. The observations underscore that digestate utilization (as a biofertilizer replacing mineral fertilizers) and best-practice storage/application are key to achieving the environmental benefits of biogas. In summary, the dominance of digestate-related emissions in the LCA highlights the importance of integrating treatment (e.g., anaerobic composting) and optimized land-application methods (e.g., injection, timing) to improve the sustainability of biogas systems.

The base-case LCA assumes displacement of the current South African electricity mix, which remains strongly coal-dominated and therefore has a high carbon intensity (approximately 850–950 g CO2 kWh−1). Under current conditions, electricity generation via biogas-based CHP yields substantial greenhouse gas benefits due to the large reductions in emissions per unit of electricity produced. However, multiple open-access power-system modelling studies indicate that deep decarbonization of the South African electricity sector is technically feasible by mid-century, with renewable electricity shares exceeding 90% and coal almost fully phased out by 2050, resulting in projected grid emission factors of approximately 35–50 g CO2 kWh−1 under ambitious transition pathways [36].

The avoided-emissions credit from biogas CHP scales linearly with the emission factor of the grid electricity displaced. Consequently, a reduction in grid carbon intensity from 900 g CO2 kWh−1 today to 200 g CO2 kWh−1 under moderate decarbonization, or to 40 g CO2 kWh−1 under deep decarbonization by 2050, would reduce the climate benefit of CHP electricity by approximately 77–96% per unit of electricity generated. In contrast, the climate performance of biomethane upgrading is comparatively insensitive to electricity grid decarbonization, as its GHG benefit primarily arises from displacing fossil natural gas and capturing methane rather than from avoided grid electricity [37].

Accordingly, while CHP remains the most climate-effective biogas utilization route under current South African grid conditions, future grid decarbonization substantially narrows this advantage. In a long-term low-carbon electricity system, biomethane pathways may deliver GHG mitigation per unit of energy that is comparable to or greater than that of other pathways. This finding highlights that the preferred biogas utilization strategy is time- and context-dependent, reinforcing the need to consider both near-term grid conditions and long-term energy system transitions when evaluating biogas deployment pathways.

3.4. Integrating TEA and LCA

An integrated interpretation of the TEA and LCA results reveals important trade-offs among financial performance, environmental outcomes, and feedstock-related constraints relevant to the sustainable deployment of AD systems. Although the TEA indicates that CHP-based configurations achieve the highest financial performance under current South African electricity price conditions, the LCA shows that upgrading-oriented pathways can offer advantages in specific environmental impact categories, particularly when improved digestate management and future energy system decarbonisation are considered. These findings indicate that pathway preference is context-dependent rather than universally optimal, and that conclusions regarding relative bankability should be interpreted alongside environmental performance, feedstock availability, and longer-term sustainability objectives. The following discussion, therefore, synthesizes TEA and LCA outcomes to inform design choices, deployment strategies, and policy considerations for biogas systems based on poultry manure and food and vegetable waste.

The combined results point to a clear roadmap for a sustainable biogas plant design for Bloemfontein. A digestion scenario prioritizing more FVW and minimal PM is recommended for Bloemfontein. Biogas utilization for CHP only (100% E) is the most financially viable base case (highest IRR/DSCR) and imposes a lower fossil-energy burden on the grid compared to upgrading. Crucially, digestate management (not the energy utilization route) controls the project’s overall environmental footprint. Therefore, the highest-priority design features should include robust digestate controls: covered, acidified storage; rapid solids–liquid separation; and biofilters to trap NH3/CH4. These measures yield large reductions in GWP, acidification, and eutrophication while having minimal TEA downside. In policy terms, this aligns with global guidelines that digestate be handled as a resource (closed storage, proper application), not a waste with open emissions [4,35,38].

From a deployment strategy, a phased approach is advisable. It is recommended to commission with a CHP-dominant or 50/50 routing (as a hedge) and securing biomethane offtake (e.g., fleet fuel or pipeline) upfront; this maximizes early cash flow and bankability. As South Africa’s grid gradually decarbonizes (e.g., on-site renewables or wheeling green power), upgrading can play a larger role economically and environmentally, since lower-carbon electricity will reduce its energy burdens. Throughout, emphasis should be on nutrient recovery: the digestate from PM and mixed blends is rich in K and P (Table A2, in the Appendix B), offering value as biofertilizer if applied properly. For instance, PM20FVW80 yields 305 mg/L P and 779 mg/L K in digestate (vs. 217 mg/L P, 1340 mg/L K for PM100), so matching crop needs can translate these into creditable offsets. Conversely, unmanaged spreading would incur eutrophication penalties.

Overall, these results support policy and design directions for Bloemfontein’s AD plant: prioritize FVW feedstock with minimal PM as co-substrate, pay attention to digestate valorization and closed-loop handling, pursue a balanced energy export strategy (favouring CHP initially), and leverage the high-nutrient digestate through agronomic applications. This approach is consistent with both South African market reality (tight electricity pricing, a coal-heavy grid) and international LCA/TEA experience (gas upgrading can boost profits but only if environmental costs of upgrading are managed).

4. Conclusions

A farm-scale biogas plant can advance multiple Sustainable Development Goals. Among these many SDGs, biogas deployment directly supports SDG 7 (affordable and clean energy), SDG 13 (climate action), and SDG 12 (responsible waste management), by expanding renewable energy supply and reducing GHG emissions. Nutrient-rich digestate can also substitute mineral fertilizers, enhancing sustainable agriculture (SDG 2). From an investor perspective, the modelled financial indicators are encouraging project IRRs up to 10% and robust debt-service cover ratios (DSCR 2–3) in the electricity-driven cases imply creditworthy returns. A Year-1 DSCR around 2.6 for the 100%-CHP route comfortably exceeds typical infrastructure lending thresholds (1.3–1.5). By substituting grid electricity, the plant also reduces fossil fuel demand, helping meet national emission-reduction targets. These co-benefits: clean energy, GHG mitigation, waste valorization, and rural economic activity, align with policymakers’ sustainability agendas. In practice, support mechanisms, such as favourable tariffs or carbon credits, would further improve the project’s bankability. Overall, this biogas project exemplifies a circular-economy approach, delivering clean energy and environmental benefits that strongly align with SDG targets, making it an attractive opportunity for investors and a strategic tool for energy and climate policy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.A.; Methodology, A.S.A.; Software, O.J.O.; Validation, C.R., T.S.M. and I.V.d.M.; Formal analysis, A.S.A. and O.J.O.; Investigation, A.S.A.; Resources, T.S.M. and J.A.V.N.; Data curation, A.S.A., J.A.V.N. and I.V.d.M.; Writing—original draft preparation, A.S.A.; Writing—review and editing, C.R., I.V.d.M. and T.S.M.; Visualization, supervision, T.S.M. and J.A.V.N.; Project administration, C.R.; Funding acquisition, T.S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project is funded by the National Research Foundation of South Africa (NRF grant number: 138093, awarded to TS Matambo), the Department of Science and Innovation (DSI), and the Technological Innovation Centre (Grant number: 2022/FUN252/AA) awarded to TS Matambo.

Data Availability Statement

Available on the University of the Free State’s figshare. 10.38140/ufs.30642539.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the Department of Sustainable Food Systems and Development, University of the Free State, and the Centre for Competence in Environmental Biotechnology, University of South Africa, for their continuous support. The National Research Foundation of South Africa (NRF grant Number: 138093, awarded to TS Matambo), the Department of Science and Innovation (DSI, South Africa), and the Technology Innovation Agency (TIA) for sponsoring the Centre for Competence in Environmental Biotechnology.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

Abbreviations used in this manuscript:

| CHP | Combined Heat and Power |

| DSCR | Debt Service Coverage Ratio |

| FVW | Fruit and Vegetable Waste |

| IRR | Internal Rate of Return |

| NPV | Net Profit Value |

| PM | Poultry Manure |

| TEA | Techno-Economic Analysis |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Feedstock composition and biogas output (per day, 50 t feed).

Table A1.

Feedstock composition and biogas output (per day, 50 t feed).

| Parameter | Unit | PM100 | FVW100 | PM20–FVW80 | PM50–FVW50 | PM70–FVW30 |

| Feedstock mass (as-received) | kg/day | 50,000 | 50,000 | 50,000 | 50,000 | 50,000 |

| Total solids (TS) % (as-received) | % | 25.38 | 12.95 | 15.43 | 19.16 | 21.65 |

| Volatile solids (VS) % of TS | % | 69.35 | 94.07 | 85.34 | 78.18 | 76.26 |

| BMP (methane potential) | Nm3 CH4/kg VS | 0.29 | 0.13 | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.22 |

| VS per day | kg/day | 8801 | 6091 | 6584 | 7490 | 8255 |

| CH4 volume per day | Nm3/day | 2508 | 792 | 1942 | 1498 | 1816 |

| Biogas volume per day | Nm3/day | 4180 | 1320 | 3237 | 2497 | 3027 |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Digestate macronutrient concentrations (mg L−1) for each substrate scenario.

Table A2.

Digestate macronutrient concentrations (mg L−1) for each substrate scenario.

| Samples | Mg (mg/L) | K (mg/L) | Ca (mg/L) | Ca2 (mg/L) | P (mg/L) | S (mg/L) | Fe (mg/L) | Na (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM100 | 159.53 | 1339.90 | 235.48 | 238.59 | 217.48 | 47.78 | 42.89 | 65.20 |

| FVW100 | 125.53 | 732.59 | 325.93 | 325.40 | 30.55 | 29.89 | 5.46 | 101.65 |

| PM20FVW80 | 197.86 | 779.08 | 601.10 | 646.16 | 304.72 | 43.06 | 4.43 | 57.79 |

| PM50FVW50 | 271.01 | 990.27 | 627.55 | 686.92 | 273.04 | 69.32 | 6.92 | 106.42 |

| PM70FVW30 | 308.56 | 1087.04 | 625.68 | 701.95 | 272.68 | 84.42 | 8.43 | 129.23 |

Appendix C

Figure A1.

Process-level GHG flow/Sankey (FU = 1 t of substrate as received) for digestate handling.

Figure A1.

Process-level GHG flow/Sankey (FU = 1 t of substrate as received) for digestate handling.

Appendix D

Worked Example: Digestate Emission Calculations and Mitigation.

Appendix D.1. Functional Unit and Approach

The functional unit (FU) is 1 t of as-received substrate processed by the anaerobic digestion system. Because the total nitrogen (N) concentration of digestate was not directly quantified for all scenarios, digestate emissions are expressed as a function of applied nitrogen per FU, (kg N t−1 feed). This proportional approach avoids arbitrary assumptions while ensuring transparency and reproducibility.

Appendix D.2. Baseline Emission Factors

Digestate emissions were calculated using IPCC Tier 1 emission factors, consistent with anaerobic digestion LCA practice:

- (i)

- NH3 volatilization = 25% of applied N;

- (ii)

- Direct N2O = 1% of applied N (as N2O-N);

- (iii)

- Indirect N2O = 1% of volatilized NH3-N.

Appendix D.3. Baseline Calculations

Ammonia volatilization:

Total N2O emissions:

Using IPCC AR6 GWP100 = 273 kg CO2-eq kg−1 N2O, the digestate-related climate impact becomes:

Appendix D.4. Mitigation Scenarios

Mitigation options were implemented by scaling the calculated baseline emissions using literature-reported efficiencies:

Covered storage (90% NH3 reduction):

Digestate acidification (pH = 6–6.5) (80% NH3, 20% direct N2O reduction):

Soil injection/band spreading (90% NH3 reduction; direct N2O unchanged):

This example shows that digestate mitigation primarily reduces acidification and eutrophication (80–90% via NH3 abatement), while GWP reductions are more moderate (15–30%) due to the dominance of N2O emissions. Because these reductions apply equally across biogas utilization routes, improved digestate management lowers absolute impacts but does not change the relative LCA ranking of CHP versus biomethane pathways.

Appendix E

Table A3.

Effect of digestate management options on impacts: percentage Δ values relative to uncovered storage, expressed per 1 t as-received feed and per unit N applied (see Appendix D).

Table A3.

Effect of digestate management options on impacts: percentage Δ values relative to uncovered storage, expressed per 1 t as-received feed and per unit N applied (see Appendix D).

| Digestate Management Scenario | NH3 Reduction (%) | Direct N2O Reduction (%) | ΔGWP (%) | ΔAP (%) | ΔEP (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (uncovered, surface application) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Reference case used in the main LCA |

| Covered digestate storage | 90% | 0% (indirectly reduced via NH3) | −15 to −20% | −90% | −90% | Strong NH3 abatement; indirect N2O reduced proportionally |

| Digestate acidification (pH = 6–6.5) | 80% | 20% | −25 to −30% | −80% | −80% | Reduces both NH3 volatilization and soil N2O formation |

| Soil injection/band spreading | 90% | 0% (may increase slightly) | −15 to −20% | −90% | −90% | NH3 nearly eliminated; conservative assumption for N2O |

References

- Shonhiwa, C.; Mapantsela, Y.; Makaka, G.; Mukumba, P.; Shambira, N. Biogas Valorisation to Biomethane for Commercialisation in South Africa: A Review. Energies 2023, 16, 5272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunniyi, O.J.; Oni, T.O.; Ikubanni, P.P.; Aliyu, S.J.; Ajisegiri, E.A.; Ibikunle, R.A.; Adekanye, T.A.; Adeleke, A.A.; Ajewole, J.B.; Ogundipe, O.L.; et al. Prospects for Nigerian Electricity Production from Renewable Energy. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Science, Engineering and Business for Sustainable Development Goals (SEB-SDG), Omu-Aran, Nigeria, 5–7 April 2023; Volume 1, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mdhluli, F.T.; Harding, K.G. Comparative life-cycle assessment of maize cobs, maize stover and wheat stalks for the production of electricity through gasification vs traditional coal power electricity in South Africa. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2021, 3, 100046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Sanz-Garrido, C.; Revuelta-Aramburu, M.; Santos-Montes, A.M.; Morales-Polo, C. A Review on Anaerobic Digestate as a Biofertilizer: Characteristics, Production, and Environmental Impacts from a Life Cycle Assessment Perspective. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masebinu, S.; Akinlabi, E.; Muzenda, E.; Aboyade, A.; Mbohwa, C. Experimental and feasibility assessment of biogas production by anaerobic digestion of fruit and vegetable waste from Joburg Market. Waste Manag. 2018, 75, 236–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagos, K.; Zong, J.; Li, D.; Liu, C.; Lu, X. Anaerobic co-digestion process for biogas production: Progress, challenges and perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 76, 1485–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhungana, B.; Lohani, S.P.; Marsolek, M. Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Food Waste with Livestock Manure at Ambient Temperature: A Biogas Based Circular Economy and Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayantokun, A.S.; Matambo, T.S.; Rashama, C.; Van der Merwe, I.; Van Niekerk, J.A. A critical review of food waste and poultry manure anaerobic co-digestion: An eco-friendly valorization for sustainable waste management and biogas production. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1695945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoye-Chine, C.G.; Otun, K.; Shiba, N.; Rashama, C.; Ugwu, S.N.; Onyeaka, H.; Okeke, C.T. Conversion of carbon dioxide into fuels—A review. J. CO2 Util. 2022, 62, 102099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibikunle, R.A.; Ogunniyi, O.J.; Onu, P.; Ade-Omowaye, J.A.; God’sfavour, O.O.; C, N.P.; Great, G.O.; Matthew, O.C. CO2 Generation from Biogas: A Comprehensive Study on Rate Determination, Upgrading Techniques, and Environmental Implications. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Science, Engineering and Business for Driving Sustainable Development Goals (SEB-SDG), Omu-Aran, Nigeria, 2–4 April 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Collet, P.; Flottes, E.; Favre, A.; Raynal, L.; Pierre, H.; Capela, S.; Peregrina, C. Techno-economic and Life Cycle Assessment of methane production via biogas upgrading and power to gas technology. Appl. Energy 2017, 192, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.B.; Jamali, N.S.; Tan, W.E.; Man, H.C.; Abidin, Z.Z. Techno-Economic Assessment of On-Farm Anaerobic Digestion System Using Attached-Biofilm Reactor in the Dairy Industry. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, L.; Sarathy, S.; Santoro, D.; Ho, D.; Ray, M.B.; Xu, C.C. Recent Advances in Energy Recovery from Wastewater Sludge. In Direct Thermochemical Liquefaction for Energy Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 67–100. [Google Scholar]

- Angouria-Tsorochidou, E.; Seghetta, M.; Trémier, A.; Thomsen, M. Life cycle assessment of digestate post-treatment and utilization. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 815, 152764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler-Rodriguez, K.; Josa, I.; Castro, L.; Escalante, H.; Garfí, M. Post-treatment and agricultural reuse of digestate from low-tech digesters: A comparative life cycle assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 894, 164992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alengebawy, A.; Mohamed, B.A.; Jin, K.; Liu, T.; Ghimire, N.; Samer, M.; Ai, P. A comparative life cycle assessment of biofertilizer production towards sustainable utilization of anaerobic digestate. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 33, 875–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiloidhari, M.; Kumari, S. Biogas Upgrading and Life Cycle Assessment of Different Biogas Upgrading Technologies. In Emerging Technologies and Biological Systems for Biogas Upgrading; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 413–445. [Google Scholar]

- Plakantonaki, S.; Kiskira, K.; Zacharopoulos, N.; Belessi, V.; Sfyroera, E.; Priniotakis, G.; Athanasekou, C. Investigating the Routes to Produce Cellulose Fibers from Agro-Waste: An Upcycling Process. ChemEngineering 2024, 8, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, L.; Busadee, N.S. Techno-Economic Analysis of Renewable Gas Production and Electricity Generation from Organic Waste. Master’s Thesis, Mälardalen University, Västerås, Sweden, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Maluta, F.; Alberini, F.; Paglianti, A.; Montante, G. Hydrodynamics and Scale-up of Anaerobic Stirred Digesters. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2023, 105, 289–294. [Google Scholar]

- Ahlberg-Eliasson, K.; Westerholm, M.; Isaksson, S.; Schnürer, A. Anaerobic Digestion of Animal Manure and Influence of Organic Loading Rate and Temperature on Process Performance, Microbiology, and Methane Emission From Digestates. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 9, 730314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillero, L.; Sganzerla, W.G.; Carneiro, T.F.; Solera, R.; Perez, M. Techno-Economic analysis of single-stage and temperature-phase anaerobic co-digestion of sewage sludge, wine vinasse, and poultry manure. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 325, 116419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’orto, A.; Trois, C. Double-Stage Anaerobic Digestion for Biohydrogen Production: A Strategy for Organic Waste Diversion and Emission Reduction in a South African Municipality. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Saxe, C.; van Eeden, J.; Kemp, L.; Steenkamp, A.; Cowper, J. High-capacity coal trucks to reduce costs and emissions at South Africa’s power utility. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2022, 48, 100898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, A.H.; Tao, L. Economic Perspectives of Biogas Production via Anaerobic Digestion. Bioengineering 2020, 7, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, N.; Alvarado-Morales, M.; Tsapekos, P.; Angelidaki, I. Techno-Economic Assessment of Biological Biogas Upgrading Based on Danish Biogas Plants. Energies 2021, 14, 8252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.; Grundl, N.; Tao, L.; Biddy, M.J.; Tan, E.C.D.; Beckham, G.T.; Humbird, D.; Thompson, D.N.; Roni, M.S. Process Design and Economics for the Conversion of Lignocellulosic Biomass to Hydrocarbon Fuels and Coproducts: 2018 Biochemical Design Case Update: Biochemical Deconstruction and Conversion of Biomass to Fuels and Products via Integrated Biorefinery Pathways; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Le Pera, A.; Sellaro, M.; Bencivenni, E. Composting food waste or digestate? Characteristics, statistical and life cycle assessment study based on an Italian composting plant. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 350, 131552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Islas, M.E.; Güereca, L.P.; Sosa-Rodriguez, F.S.; Cobos-Peralta, M.A. Environmental assessment of energy production from anaerobic digestion of pig manure at medium-scale using life cycle assessment. Waste Manag. 2020, 102, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quilez, D.; Balcells, M.; Herrero, E. Reducing Ammonia Emissions from Digested Animal Manure: Effectiveness of Acidification, Open Disc Injection, and Fertigation in Mediterranean Cereal Systems. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamp, J.N.; Feilberg, A. Covering reduces emissions of ammonia, methane, and nitrous oxide from stockpiled broiler litter. Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 248, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, T.; Ehimen, E. Exploring the potential role of decentralised biogas plants in meeting energy needs in sub-Saharan African countries: A techno-economic systems analysis. Sustain. Energy Res. 2024, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonazzi, G.; Iotti, M. Evaluation of Biogas Plants by the Application of an Internal Rate of Return and Debt Service Coverage Approach. Am. J. Environ. Sci. 2015, 11, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.E.; Liew, P.Y.; Tan, L.S.; Woon, K.S.; Rozali, N.E.M.; Ho, W.S.; NorRuwaida, J. Life Cycle Assessment and Techno-Economic Analysis for Anaerobic Digestion as Cow Manure Management System. Energies 2022, 15, 9586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Duan, C.; Wang, X.; Liang, D. Systematic Review on the Life Cycle Assessment of Manure-Based Anaerobic Digestion System. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyewo, A.S.; Aghahosseini, A.; Ram, M.; Lohrmann, A.; Breyer, C. Pathway towards achieving 100% renewable electricity by 2050 for South Africa. Sol. Energy 2019, 191, 549–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeschl, M.; Ward, S.; Owende, P. Environmental impacts of biogas deployment—Part I: Life cycle inventory for evaluation of production process emissions to air. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 24, 168–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhull, P.; Mozhiarasi, V.; Kumar, S.; Rose, P.B.; Lohchab, R.K. Current and prognostic overview of digestate management and processing practices, regulations and standards. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2024, 61, 103345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.