Sustainability Assessment of Bioethanol from Food Industry Lignocellulosic Wastes: A Life Cycle Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Search and Data Harmonization Approach

3. Feedstock Characteristics and Conversion Pathways

3.1. Food Industry Lignocellulosic Wastes

3.1.1. Oil-Processing Residues

3.1.2. Sugar-Processing Residues

3.1.3. Brewing Residues

3.1.4. Fruit and Starch Processing Residues

3.2. Conversion Pathways

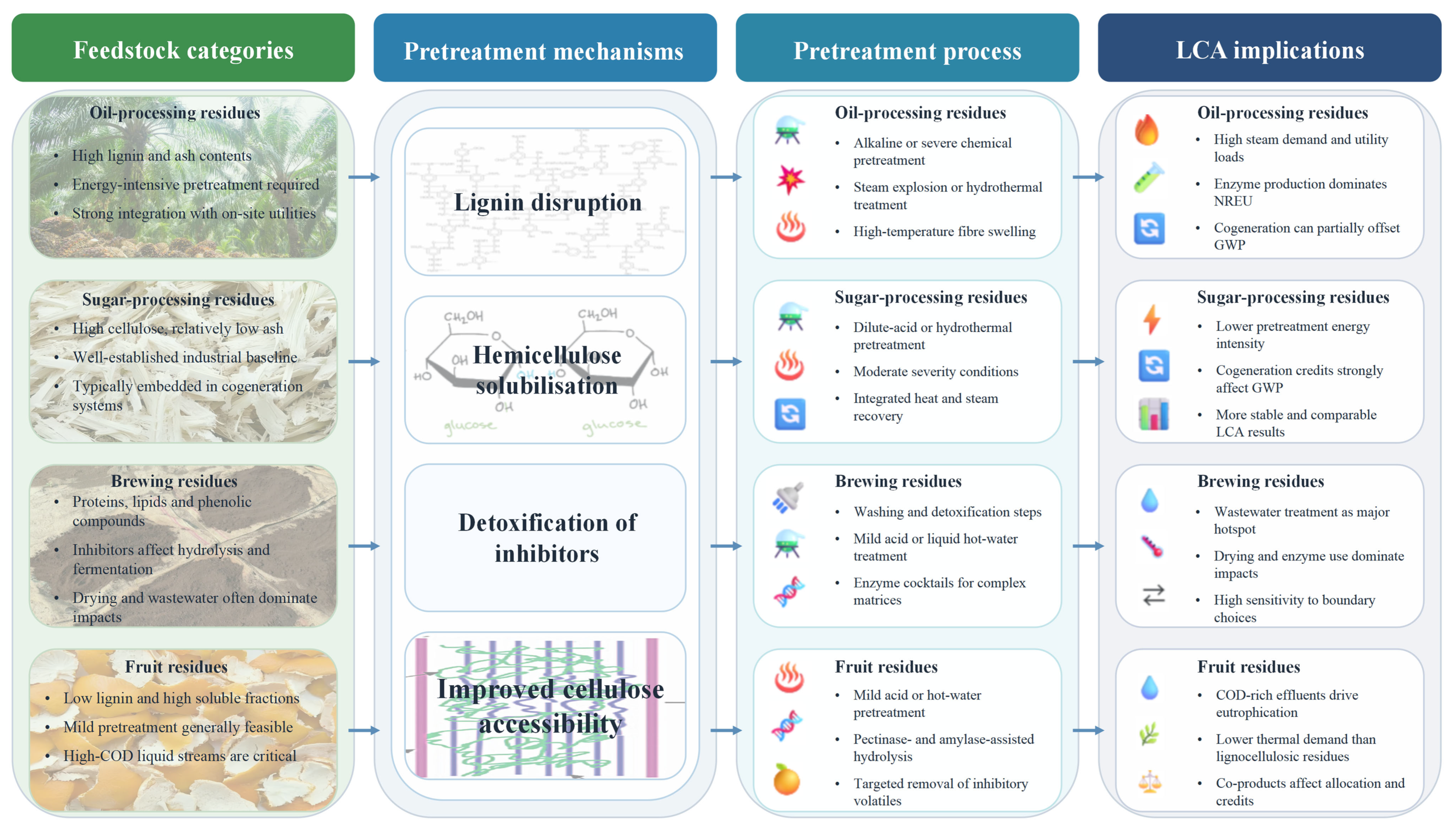

3.2.1. Pretreatment Strategies and Feedstock–Pathway Matching

3.2.2. Hydrolysis and Fermentation Architectures

3.2.3. Energy Systems, Scale and Integration with Existing Plants

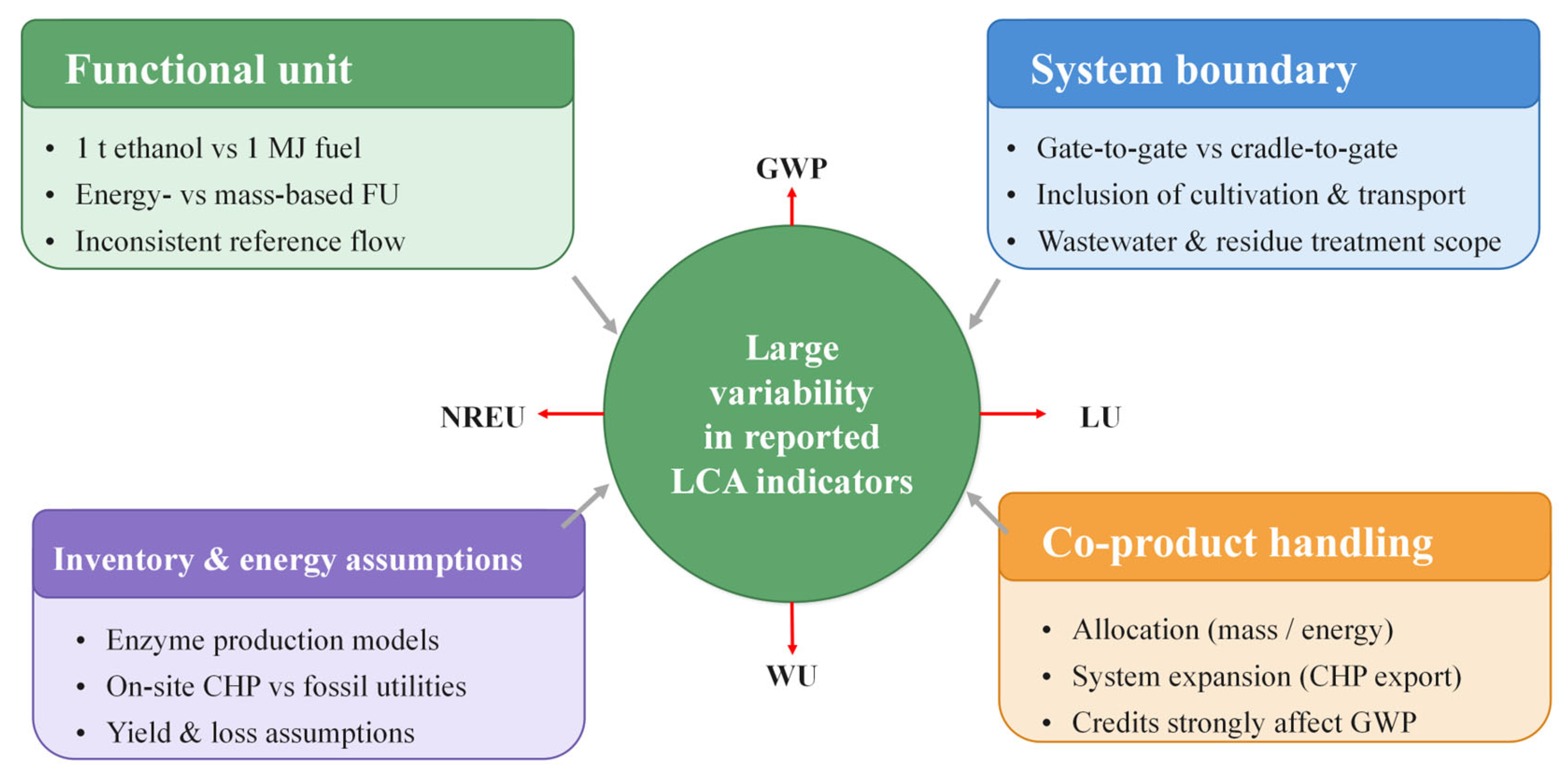

4. Methodological Drivers of Variability in Waste-Derived Ethanol LCA

4.1. Functional Units and System Boundaries

4.2. Co-Product Structures and Allocation Approaches

4.3. Inventory Modelling: Energy Systems, Enzymes, Wastewater and Logistics

4.4. LCIA Method Selection and Indicator Coverage

5. Comparative Environmental Performance Across Food Industry Waste Ethanol Systems

5.1. Greenhouse Gas Performance Across Waste-Derived Ethanol Systems

5.2. Energy Performance and Non-Renewable Energy Demand

5.3. Water and Land Implications: Variability and Reporting Gaps

6. Comparative Insights and Future Directions for Waste-Derived Ethanol LCA

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 1G | first-generation ethanol |

| 2G | second-generation ethanol |

| AD | anaerobic digestion |

| ADP | abiotic depletion potential |

| AP | acidification potential |

| BSG | brewer’s spent grain |

| CED | cumulative energy demand |

| CHP | combined heat and power |

| COD | chemical oxygen demand |

| EFB | oil palm empty fruit bunches |

| EP | eutrophication potential |

| ER | energy ratio |

| FEP | freshwater eutrophication potential |

| FU | functional unit |

| GWP | global warming potential |

| HTL | hydrothermal liquefaction |

| HTP | human toxicity potential |

| LCA | life cycle assessment |

| LCIA | life cycle impact assessment |

| LHW | liquid hot water |

| LU | land use |

| MEP | marine eutrophication potential |

| NEV | net energy value |

| NREU | non-renewable energy use |

| ODP | ozone depletion potential |

| OPEFB | oil palm empty fruit bunch |

| POCP | photochemical oxidant creation potential |

| POP | photochemical oxidant formation |

| S:L | solid-to-liquid ratio |

| SCG | spent coffee grounds |

| SHF | separate hydrolysis and fermentation |

| SSCF | simultaneous saccharification and co-fermentation |

| SSF | simultaneous saccharification and fermentation |

| TEA | techno-economic analysis |

| TEP | terrestrial ecotoxicity potential |

| WU | water use |

References

- Lv, C.-L.; Cao, Y.-D.; Feng, Y.; Fan, L.-L.; Zhang, J.-Y.; Song, Y.-H.; Liu, H.; Gao, G.-G. Crosslinked Vinyl-Capped Polyoxometalates to Construct a Three-Dimensional Porous Inorganic–Organic Catalyst to Effectively Suppress Polysulfide Shuttle in Li–S Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2025, e05978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabed, H.; Sahu, J.N.; Suely, A.; Boyce, A.N.; Faruq, G. Bioethanol Production from Renewable Sources: Current Perspectives and Technological Progress. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 71, 475–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, M.M.R.; Seabra, J.E.A.; Lynd, L.R.; Arantes, S.M.; Cunha, M.P.; Guilhoto, J.J.M. Socio-Environmental and Land-Use Impacts of Double-Cropped Maize Ethanol in Brazil. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Wang, R.; Gasser, T.; Ciais, P.; Peñuelas, J.; Balkanski, Y.; Boucher, O.; Janssens, I.A.; Sardans, J.; Clark, J.H.; et al. Delayed Use of Bioenergy Crops Might Threaten Climate and Food Security. Nature 2022, 609, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedr, A.M.; El-Adawy, M.; Ismael, M.A.; Qador, A.; Abdelhafez, A.; Ben-Mansour, R.; Habib, M.A.; Nemitallah, M.A. Recent Fuel-Based Advancements of Internal Combustion Engines: Status and Perspectives. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 5099–5132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeswani, H.K.; Falano, T.; Azapagic, A. Life Cycle Environmental Sustainability of Lignocellulosic Ethanol Produced in Integrated Thermo-Chemical Biorefineries. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefin. 2015, 9, 661–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Lee, U.; Wang, M. Life-Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reduction Potential for Corn Ethanol Refining in the USA. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefin. 2022, 16, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Koelewijn, S.-F.; Van Den Bossche, G.; Van Aelst, J.; Van Den Bosch, S.; Renders, T.; Navare, K.; Nicolaï, T.; Van Aelst, K.; Maesen, M.; et al. A Sustainable Wood Biorefinery for Low–Carbon Footprint Chemicals Production. Science 2020, 367, 1385–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therasme, O.; Volk, T.A.; Eisenbies, M.H.; Amidon, T.E.; Fortier, M.-O. Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Ethanol Produced via Fermentation of Sugars Derived from Shrub Willow (Salix ssp.) Hot Water Extraction in the Northeast United States. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2021, 14, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, L.A.; Dale, B.E.; Bozzetto, S.; Liebman, M.; Souza, G.M.; Haddad, N.; Richard, T.L.; Basso, B.; Brown, R.C.; Hilbert, J.A.; et al. Meeting Global Challenges with Regenerative Agriculture Producing Food and Energy. Nat. Sustain. 2021, 5, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Kumar, S. A Comprehensive Review of Bioethanol Production from Diverse Feedstocks: Current Advancements and Economic Perspectives. Energy 2024, 296, 131130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, J.K.; Saini, R.; Tewari, L. Lignocellulosic Agriculture Wastes as Biomass Feedstocks for Second-Generation Bioethanol Production: Concepts and Recent Developments. 3 Biotech 2015, 5, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, D.J.; Carvalho, A.P.A.D.; Conte-Junior, C.A. Fermentation of Biomass and Residues from Brazilian Agriculture for 2G Bioethanol Production. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 40298–40314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anokye, K.; Mohammed, A.S.; Agyemang, P.; Agya, B.A.; Amuah, E.E.Y.; Sodoke, S. A Systematic Review of the Impacts of Open Burning and Open Dumping of Waste in Ghana: A Way Forward for Sustainable Waste Management. Clean. Waste Syst. 2024, 8, 100152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; Reay, D.; Smith, J. Agricultural Methane Emissions and the Potential Formitigation. Philos. Trans. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2021, 379, 20200451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukiran, M.A.; Abnisa, F.; Syafiie, S.; Wan Daud, W.M.A.; Nasrin, A.B.; Abdul Aziz, A.; Loh, S.K. Experimental and Modelling Study of the Torrefaction of Empty Fruit Bunches as a Potential Fuel for Palm Oil Mill Boilers. Biomass Bioenergy 2020, 136, 105530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James Rubinsin, N.; Daud, W.R.W.; Kamarudin, S.K.; Masdar, M.S.; Rosli, M.I.; Samsatli, S.; Tapia, J.F.; Wan Ab Karim Ghani, W.A.; Lim, K.L. Optimization of Oil Palm Empty Fruit Bunches Value Chain in Peninsular Malaysia. Food Bioprod. Process. 2020, 119, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yafetto, L.; Odamtten, G.T.; Wiafe-Kwagyan, M. Valorization of Agro-Industrial Wastes into Animal Feed through Microbial Fermentation: A Review of the Global and Ghanaian Case. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohar, H.; Beggio, G.; Schiavon, M.; Lavagnolo, M.C. A Systematic Review on the Potential of Agro-Industrial Waste for Pyrolysis: Feedstocks Properties and Their Impact on Biochar and Pyrolysis Gas Composition. Biomass Bioenergy 2025, 200, 108047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Same, N.N.; Yakub, A.O.; Chaulagain, D.; Tangoh, A.F.; Nsafon, B.E.K.; Owolabi, A.B.; Suh, D.; Huh, J.-S. The Future of Clean Energy: Agricultural Residues as a Bioethanol Source and Its Ecological Impacts in Africa. Renew. Energy 2024, 237, 121612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeswani, H.K.; Chilvers, A.; Azapagic, A. Environmental Sustainability of Biofuels: A Review. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2020, 476, 20200351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Styles, D.; Gibbons, J.; Williams, A.P.; Dauber, J.; Stichnothe, H.; Urban, B.; Chadwick, D.R.; Jones, D.L. Consequential Life Cycle Assessment of Biogas, Biofuel and Biomass Energy Options within an Arable Crop Rotation. GCB Bioenergy 2015, 7, 1305–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.; Mohanty, A.K.; Dick, P.; Misra, M. A Review on the Challenges and Choices for Food Waste Valorization: Environmental and Economic Impacts. ACS Environ. Au 2023, 3, 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathura, S.R.; Landázuri, A.C.; Mathura, F.; Andrade Sosa, A.G.; Orejuela-Escobar, L.M. Hemicelluloses from Bioresidues and Their Applications in the Food Industry—Towards an Advanced Bioeconomy and a Sustainable Global Value Chain of Chemicals and Materials. Sustain. Food Technol. 2024, 2, 1183–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvelli, S.; Jia, L.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, J. Review of Advanced Technologies and Circular Pathways for Food Waste Valorization. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 16085–16108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbiah, G.; Jena, A.; Kalidhas, A.M.; Kele, V.; Aadiwal, V.; Awasthi, K.; K, K.P. Sustainable Food Production and Valorization of Food and Agricultural Waste: Recent Advances and Future Prospects. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 5, 2549–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himmel, M.E.; Ding, S.-Y.; Johnson, D.K.; Adney, W.S.; Nimlos, M.R.; Brady, J.W.; Foust, T.D. Biomass Recalcitrance: Engineering Plants and Enzymes for Biofuels Production. Science 2007, 315, 804–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Y.; Hu, F.; Huang, F.; Davison, B.H.; Ragauskas, A.J. Assessing the Molecular Structure Basis for Biomass Recalcitrance during Dilute Acid and Hydrothermal Pretreatments. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2013, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Short, M.D.; Alvarez-Gaitan, J.P.; Guo, X.; Duan, J.; Saint, C.; Chen, G.; Hou, L. Environmental Life Cycle Assessment of Lignocellulosic Ethanol-Blended Fuels: A Case Study. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosier, N.; Wyman, C.; Dale, B.; Elander, R.; Lee, Y.Y.; Holtzapple, M.; Ladisch, M. Features of Promising Technologies for Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2005, 96, 673–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, S.K.; Nasrin, A.B.; Sukiran, M.A.; Bukhari, N.A.; Subramaniam, V. Chapter 22—Oil Palm Biomass Value Chain for Biofuel Development in Malaysia: Part II. In Value-Chain of Biofuels; Yusup, S., Rashidi, N.A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 505–534. [Google Scholar]

- Jönsson, L.J.; Martín, C. Pretreatment of Lignocellulose: Formation of Inhibitory by-Products and Strategies for Minimizing Their Effects. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 199, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caputo, F.; Al-Rudainy, B.; Naidjonoka, P.; Wallberg, O.; Olsson, L.; Novy, V. Understanding the Impact of Steam Pretreatment Severity on Cellulose Ultrastructure, Recalcitrance, and Hydrolyzability of Norway Spruce. Biomass Conv. Biorefin. 2024, 14, 27211–27223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinho, F.; Bertaglia, A.B.B.; Almeida, C.M.V.B.; Giannetti, B.F. Influence of Cellulase Enzyme Production on the Energetic–Environmental Performance of Lignocellulosic Ethanol. Ecol. Model. 2015, 315, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, T.; Gustafson, R.; Bura, R.; Gough, H.L. Integration of Wastewater Treatment into Process Design of Lignocellulosic Biorefineries for Improved Economic Viability. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2020, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obydenkova, S.V.; Kouris, P.D.; Hensen, E.J.M.; Heeres, H.J.; Boot, M.D. Environmental Economics of Lignin Derived Transport Fuels. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 243, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuess, L.T.; Garcia, M.L. Bioenergy from Stillage Anaerobic Digestion to Enhance the Energy Balance Ratio of Ethanol Production. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 162, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraccascia, L.; Yazdanpanah, V.; van Capelleveen, G.; Yazan, D.M. Energy-Based Industrial Symbiosis: A Literature Review for Circular Energy Transition. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 4791–4825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, M.; Quintero, J.; Conejeros, R.; Aroca, G. Life Cycle Assessment of Lignocellulosic Bioethanol: Environmental Impacts and Energy Balance. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 42, 1349–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiloso, E.I.; Heijungs, R.; de Snoo, G.R. LCA of Second Generation Bioethanol: A Review and Some Issues to Be Resolved for Good LCA Practice. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 5295–5308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnansounou, E.; Dauriat, A.; Villegas, J.; Panichelli, L. Life Cycle Assessment of Biofuels: Energy and Greenhouse Gas Balances. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 4919–4930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Duan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Pineda, E.; Yang, Y.; Pelletier, J.-M.; Wada, T.; Kato, H.; Crespo, D.; Qiao, J. Creep and Recovery Behavior of Metallic Glasses in a Global Strain Approach within Transition State Theory. Acta Mech. Sin. 2026, 42, 425311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherubini, F.; Strømman, A.H. Life Cycle Assessment of Bioenergy Systems: State of the Art and Future Challenges. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luk, J.M.; Pourbafrani, M.; Saville, B.A.; MacLean, H.L. Ethanol or Bioelectricity? Life Cycle Assessment of Lignocellulosic Bioenergy Use in Light-Duty Vehicles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 10676–10684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuppaladadiyam, A.K.; Prinsen, P.; Raheem, A.; Luque, R.; Zhao, M. Sustainability Analysis of Microalgae Production Systems: A Review on Resource with Unexploited High-Value Reserves. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 14031–14049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provost-Savard, A.; Majeau-Bettez, G. Substitution Modeling Can Coherently Be Used in Attributional Life Cycle Assessments. J. Ind. Ecol. 2024, 28, 410–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, C. Life Cycle Assessment of Biofuels in the European Renewable Energy Directive: A Combination of Approaches? Greenh. Gas Meas. Manag. 2014, 4, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Lv, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, T.; Tian, W.; Zhou, Q.; Zeng, L.; Wan, M.; Liu, C. A Focal Quotient Gradient System Method for Deep Neural Network Training. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 184, 113704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolah, R.; Karnik, R.; Hamdan, H. A Comprehensive Review on Biofuels from Oil Palm Empty Bunch (EFB): Current Status, Potential, Barriers and Way Forward. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu, M.O.; Atia, K.; Arthur, E.; Asare, P.A.; Obour, P.B.; Danso, E.O.; Frimpong, K.A.; Sanleri, K.A.; Asare-Larbi, S.; Adjei, R.; et al. The Use of Oil Palm Empty Fruit Bunches as a Soil Amendmentto Improve Growth and Yield of Crops. A Meta-Analysis. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 42, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuar, N.I.S.; Zakaria, S.; Kaco, H.; Chia, C.H.; Wang, C.; Abdullah, H.S. Physico-Mechanical, Chemical Composition, Thermal Degradation and Crystallinity of Oil Palm Empty Fruit Bunch, Kenaf and Polypropylene Fibres: A Comparatives Study. Sains Malays. 2018, 47, 839–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayah, N.; Wusko, I.U. Characterization and Analysis of Oil Palm Empty Fruit Bunch (OPEFB) Waste of PT Kharisma Alam Persada South Borneo. Maj. Obat Tradis. 2020, 25, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, A.D.; Valle, V.; Almeida-Naranjo, C.E.; Naranjo, Á.; Cadena, F.; Kreiker, J.; Raggiotti, B. Characterization Dataset of Oil Palm Empty Fruit Bunch (OPEFB) Fibers—Natural Reinforcement/Filler for Materials Development. Data Brief 2022, 45, 108618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isroi; Ishola, M.M.; Millati, R.; Syamsiah, S.; Cahyanto, M.N.; Niklasson, C.; Taherzadeh, M.J. Structural Changes of Oil Palm Empty Fruit Bunch (OPEFB) after Fungal and Phosphoric Acid Pretreatment. Molecules 2012, 17, 14995–15012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosli, N.S.; Harun, S.; Jahim, J.M.; Othaman, R. Chemical and Physical Characterization of Oil Palm Empty Fruit Bunch. Malays. J. Anal. Sci. 2017, 21, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franca, A.S.; Oliveira, L.S. Potential Uses of Spent Coffee Grounds in the Food Industry. Foods 2022, 11, 2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuluaga, R.; Hoyos, C.G.; Velásquez-Cock, J.; Vélez-Acosta, L.; Palacio Valencia, I.; Rodríguez Torres, J.A.; Gañán Rojo, P. Exploring Spent Coffee Grounds: Comprehensive Morphological Analysis and Chemical Characterization for Potential Uses. Molecules 2024, 29, 5866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartolucci, L.; Cordiner, S.; Mele, P.; Mulone, V. Defatted Spent Coffee Grounds Fast Pyrolysis Polygeneration System: Lipid Extraction Effect on Energy Yield and Products Characteristics. Biomass Bioenergy 2023, 179, 106974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khashpakyants, B.; Krasina, I.; Filippova, E. Coffee Sludge as a New Food Ingredient. In BIO Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2021; Volume 34, p. 06012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagett, M.; Teng, K.S.; Sullivan, G.; Zhang, W. Reusing Waste Coffee Grounds as Electrode Materials: Recent Advances and Future Opportunities. Glob. Chall. 2023, 7, 2200093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsigkou, K.; Demissie, B.A.; Hashim, S.; Ghofrani-Isfahani, P.; Thomas, R.; Mapinga, K.F.; Kassahun, S.K.; Angelidaki, I. Coffee Processing Waste: Unlocking Opportunities for Sustainable Development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 210, 115263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Balushi, J.; Al Saadi, S.; Ahanchi, M.; Al Attar, M.; Jafary, T.; Al Hinai, M.; Yeneneh, A.M.; Basha, J.S. A Comprehensive Review on Sustainable Conversion of Spent Coffee Grounds into Energy Resources and Environmental Applications. Biomass 2025, 5, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajala, E.O.; Ighalo, J.O.; Ajala, M.A.; Adeniyi, A.G.; Ayanshola, A.M. Sugarcane Bagasse: A Biomass Sufficiently Applied for Improving Global Energy, Environment and Economic Sustainability. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2021, 8, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiranobe, C.T.; Gomes, A.S.; Paiva, F.F.G.; Tolosa, G.R.; Paim, L.L.; Dognani, G.; Cardim, G.P.; Cardim, H.P.; dos Santos, R.J.; Cabrera, F.C. Sugarcane Bagasse: Challenges and Opportunities for Waste Recycling. Clean Technol. 2024, 6, 662–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Aires, F.I.; Freitas, I.S.; dos Santos, K.M.; da Silva Vieira, R.; Nascimento Dari, D.; Junior, P.G.d.S.; Serafim, L.F.; Menezes Ferreira, A.Á.; Galvão da Silva, C.; da Silva, É.D.L.; et al. Sugarcane Bagasse as a Renewable Energy Resource: A Bibliometric Analysis of Global Research Trends. ACS Sustain. Resour. Manag. 2025, 2, 1551–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Soccol, C.R.; Nigam, P.; Soccol, V.T. Biotechnological Potential of Agro-Industrial Residues. I: Sugarcane Bagasse. Bioresour. Technol. 2000, 74, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezende, C.A.; de Lima, M.A.; Maziero, P.; deAzevedo, E.R.; Garcia, W.; Polikarpov, I. Chemical and Morphological Characterization of Sugarcane Bagasse Submitted to a Delignification Process for Enhanced Enzymatic Digestibility. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2011, 4, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alokika; Anu; Kumar, A.; Kumar, V.; Singh, B. Cellulosic and Hemicellulosic Fractions of Sugarcane Bagasse: Potential, Challenges and Future Perspective. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 169, 564–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeyi, M.J.B.; Olanrewaju, O.A. Bagasse Electricity Potential of Conventional Sugarcane Factories. J. Energy 2023, 2023, 5749122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, F.; Mota, I.F.; da Silva Burgal, J.; Pintado, M.; Costa, P.S. A Review on the Valorization of Lignin from Sugarcane By-Products: From Extraction to Application. Biomass Bioenergy 2022, 166, 106603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barciela, P.; Perez-Vazquez, A.; Fraga-Corral, M.; Prieto, M.A. Utility Aspects of Sugarcane Bagasse as a Feedstock for Bioethanol Production: Leading Role of Steam Explosion as a Pretreatment Technique. Processes 2023, 11, 3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndikumana, S.; Tanane, O.; Aichi, Y.; Latifa, E.F.; Goudali, L. Innovative Applications of Sugarcane Bagasse in the Global Sugarcane Industry. Processes 2025, 13, 3796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milew, K.; Manke, S.; Grimm, S.; Haseneder, R.; Herdegen, V.; Braeuer, A.S. Application, Characterisation and Economic Assessment of Brewers’ Spent Grain and Liquor. J. Inst. Brew. 2022, 128, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeko-Pivač, A.; Tišma, M.; Žnidaršič-Plazl, P.; Kulisic, B.; Sakellaris, G.; Hao, J.; Planinić, M. The Potential of Brewer’s Spent Grain in the Circular Bioeconomy: State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 870744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osei, E.D.; Naik, A.S.; Kinsella, G.; Delaney, T.; Kirwan, S. Potential of Brewer’s Spent Grain Bioactive Fractions as Functional Ingredients for Companion and Farm Animal Foods—A Review. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 101138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackowski, M.; Niedźwiecki, Ł.; Jagiełło, K.; Uchańska, O.; Trusek, A. Brewer’s Spent Grains—Valuable Beer Industry By-Product. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikram, S.; Huang, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Yin, M. Composition and Nutrient Value Proposition of Brewers Spent Grain. J. Food Sci. 2017, 82, 2232–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkin, J.M.; Mainali, K.; Sharma, B.K.; Yadav, M.P.; Ngo, H.; Sarker, M.I. A Review of Chemical and Physical Analysis, Processing, and Repurposing of Brewers’ Spent Grain. Biomass 2025, 5, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussatto, S.I.; Dragone, G.; Roberto, I.C. Brewers’ Spent Grain: Generation, Characteristics and Potential Applications. J. Cereal Sci. 2006, 43, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assandri, D.; Giacomello, G.; Bianco, A.; Zara, G.; Budroni, M.; Pampuro, N. Environmental Sustainability of Brewers’ Spent Grains Composting: Effect of Turning Strategies and Mixtures Composition on Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Agronomy 2025, 15, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyhan, L.; Sahin, A.W.; Schmitz, H.H.; Siegel, J.B.; Arendt, E.K. Brewers’ Spent Grain: An Unprecedented Opportunity to Develop Sustainable Plant-Based Nutrition Ingredients Addressing Global Malnutrition Challenges. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 10543–10564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinola, S.A.; Saba, B.; Christy, A.; Cornish, K.; Ezeji, T.C. Biohydrogen and Biobutanol Production from Spent Coffee and Tea Waste Using Clostridium beijerinckii. Fermentation 2025, 11, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melikoglu, M. Tea Waste Management: A Global Review of Sustainable Resource Recovery and Applications. Clean. Waste Syst. 2025, 12, 100429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indira, D.; Das, B.; Bhawsar, H.; Moumita, S.; Johnson, E.M.; Balasubramanian, P.; Jayabalan, R. Investigation on the Production of Bioethanol from Black Tea Waste Biomass in the Seawater-Based System. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2018, 4, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, D.A.R.; Allam, M.A.; Farag, M.M. Tea Wastes as An Alternative Sustainable Raw Material for Ethanol Production. Egypt. J. Chem. 2020, 63, 2683–2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afdhol, M.K.; Lubis, H.Z.; Siregar, C.P. Bioethanol Production from Tea Waste as a Basic Ingredient in Renewable Energy Sources. J. Earth Energy Eng. 2019, 8, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvaprasad, D.E.J.; Hegde, K.R.; Somasundaram, K.D.; Manickam, L. Recent Advancements in Citrus By-Product Utilization for Sustainable Food Production. Food Biomacromol. 2025, 2, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, P.; Tripathi, G.; Mir, S.S.; Yousuf, O. Current Scenario and Global Perspectives of Citrus Fruit Waste as a Valuable Resource for the Development of Food Packaging Film. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 141, 104190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Herrera, N.; Martínez-Ávila, G.C.G.; Robledo-Jiménez, C.L.; Rojas, R.; Orozco-Zamora, B.S. From Citrus Waste to Valuable Resources: A Biorefinery Approach. Biomass 2024, 4, 784–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Q.; Ren, J.; Jia, X.; Zhang, N.; Fan, G.; Pan, S.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, S. Valorization of Citrus Pomace for Cellulose Extraction and Double-Crosslinked Cellulose Hydrogel Fabrication. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 167, 111442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, P.D.; Mandavgane, S.A.; Kulkarni, B.D. Fruit Peel Waste: Characterization and Its Potential Uses. Curr. Sci. 2017, 113, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolo, M.R.V.; Pereira, T.S.; dos Santos, F.V.; Facure, M.H.M.; dos Santos, F.; Teodoro, K.B.R.; Mercante, L.A.; Correa, D.S. Citrus Wastes as Sustainable Materials for Active and Intelligent Food Packaging: Current Advances. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Orozco, R.; Balderas Hernández, P.; Roa Morales, G.; Ureña Núñez, F.; Orozco Villafuerte, J.; Lugo Lugo, V.; Flores Ramírez, N.; Barrera Díaz, C.E.; Cajero Vázquez, P. Characterization of Lignocellulosic Fruit Waste as an Alternative Feedstock for Bioethanol Production. BioResources 2014, 9, 1873–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekar, C.M.; Carullo, D.; Saitta, F.; Krishnamachari, H.; Bellesia, T.; Nespoli, L.; Caneva, E.; Baschieri, C.; Signorelli, M.; Barbiroli, A.G.; et al. Valorization of Citrus Peel Industrial Wastes for Facile Extraction of Extractives, Pectin, and Cellulose Nanocrystals through Ultrasonication: An in-Depth Investigation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 344, 122539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, B.; Coelho, E.; Gullón, B.; Yáñez, R.; Domingues, L. Potato Peels Waste as a Sustainable Source for Biotechnological Production of Biofuels: Process Optimization. Waste Manag. 2023, 155, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Jiang, Y.; Guo, W.; Niu, K.; Zhang, R.; Hou, S.; Wang, M.; Yi, Y.; Zhu, C.; Jia, C.; et al. An Environmentally Friendly and Productive Process for Bioethanol Production from Potato Waste. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2016, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marulanda-Toro, J.A.; Solarte-Toro, J.C.; Hoyos-Leyva, J.D.; Alonso-Gomez, L. Valorizing Potato Peel Waste Biorefinery Concept. RIVAR 2025, 12, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; McDonald, A.G. Chemical and Thermal Characterization of Potato Peel Waste and Its Fermentation Residue as Potential Resources for Biofuel and Bioproducts Production. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 8421–8429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, R.A.; Al-Bar, O.A.; Soliman, Y.M.A. Biochemical Studies on the Production of Biofuel (Bioethanol) from Potato Peels Wastes by Saccharomyces Cerevisiae: Effects of Fermentation Periods and Nitrogen Source Concentration. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2016, 30, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R. Bioethanol Production from Potato Peel Waste. Int. J. Sci. Res. Eng. Trends 2024, 10, 1959–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, S.K.; Sharma, B.; Sharma, A.; Thakur, B.; Soni, R. Exploring the Potential of Potato Peels for Bioethanol Production through Various Pretreatment Strategies and an In-House-Produced Multi-Enzyme System. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Taher, I.; Fickers, P.; Chniti, S.; Hassouna, M. Optimization of Enzymatic Hydrolysis and Fermentation Conditions for Improved Bioethanol Production from Potato Peel Residues. Biotechnol. Prog. 2017, 33, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Joseph, N.; Hemashini, T.; Leh, C.P. Valorization of Lignocellulosic Biomass: Progress in the Production of Second-Generation Bioethanol. Renew. Energ. 2024, 2, 27533735241284221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stichnothe, H.; Schuchardt, F. Life Cycle Assessment of Two Palm Oil Production Systems. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 3976–3984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stichnothe, H.; Schuchardt, F. Comparison of Different Treatment Options for Palm Oil Production Waste on a Life Cycle Basis. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2010, 15, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasution, M.A.; Wibawa, D.S.; Ahamed, T.; Noguchi, R. Comparative Environmental Impact Evaluation of Palm Oil Mill Effluent Treatment Using a Life Cycle Assessment Approach: A Case Study Based on Composting and a Combination for Biogas Technologies in North Sumatera of Indonesia. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 184, 1028–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, M.; Prawisudha, P.; Prabowo, B.; Budiman, B.A. Integration of Energy-Efficient Empty Fruit Bunch Drying with Gasification/Combined Cycle Systems. Appl. Energy 2015, 139, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhiyanon, T.; Sathitruangsak, P.; Sungworagarn, S.; Fukuda, S.; Tia, S. Ash and Deposit Characteristics from Oil-Palm Empty-Fruit-Bunch (EFB) Firing with Kaolin Additive in a Pilot-Scale Grate-Fired Combustor. Fuel Process. Technol. 2013, 115, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Guest, J.S. BioSTEAM-LCA: An Integrated Modeling Framework for Agile Life Cycle Assessment of Biorefineries under Uncertainty. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 18903–18914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahardika, M.; Zakiyah, A.; Ulfa, S.M.; Ilyas, R.A.; Hassan, M.Z.; Amelia, D.; Knight, V.F.; Norrrahim, M.N.F. Recent Developments in Oil Palm Empty Fruit Bunch (OPEFB) Fiber Composite. J. Nat. Fibers 2024, 21, 2309915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioranelli, A.; Bizzo, W.A. Generation of Surplus Electricity in Sugarcane Mills from Sugarcane Bagasse and Straw: Challenges, Failures and Opportunities. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 186, 113647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Kwon, H.; Wang, M.; O’Connor, D. Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Brazilian Sugar Cane Ethanol Evaluated with the GREET Model Using Data Submitted to RenovaBio. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 11814–11822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, A.M.; Aneke, M.C.; Görgens, J.F. Techno-Economic Comparison of Ethanol and Electricity Coproduction Schemes from Sugarcane Residues at Existing Sugar Mills in Southern Africa. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2014, 7, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensinas, A.V.; Nebra, S.A.; Lozano, M.A.; Serra, L.M. Analysis of Process Steam Demand Reduction and Electricity Generation in Sugar and Ethanol Production from Sugarcane. Energy Convers. Manag. 2007, 48, 2978–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brander, M.; Wylie, C. The Use of Substitution in Attributional Life Cycle Assessment. Greenh. Gas Meas. Manag. 2011, 1, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K.M.; Steffen, E.J.; Arendt, E.K. Brewers’ Spent Grain: A Review with an Emphasis on Food and Health. J. Inst. Brew. 2016, 122, 553–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evaristo, R.B.W.; Costa, A.A.; Nascimento, P.G.B.D.; Ghesti, G.F. Biorefinery Development Based on Brewers’ Spent Grain (BSG) Conversion: A Forecasting Technology Study in the Brazilian Scenario. Biomass 2023, 3, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panusa, A.; Zuorro, A.; Lavecchia, R.; Marrosu, G.; Petrucci, R. Recovery of Natural Antioxidants from Spent Coffee Grounds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 4162–4168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makiso, M.U.; Tola, Y.B.; Ogah, O.; Endale, F.L. Bioactive Compounds in Coffee and Their Role in Lowering the Risk of Major Public Health Consequences: A Review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 734–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Lee, A.; Choe, C.; Lim, H. Comparative Study of Biofuel Production Based on Spent Coffee Grounds Transesterification and Pyrolysis: Process Simulation, Techno-Economic, and Life Cycle Assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 428, 139308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasek, A.M.; Bardadyn, P.; Trojan, Z.; Jelonek, K.; Wysocki, Ł.; Kobiela, T.; Sobiepanek, A. Research on Spent Coffee Grounds: From Oil Extraction to Its Potential Application in Cosmetics. Waste Biomass Valor. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisiga, W.; Chetty, M.; Rathilal, S. Environmental Impact Assessment of Alternative Technologies for Production of Biofuels from Spent Coffee Grounds. Energy Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 4823–4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Yadav, A.; Kumar, S.; Murasingh, S. An Extensive Review Study on Bioresources Recovery from Tea Waste and Its Emerging Applications. Waste Manag. Bull. 2024, 2, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zema, D.A.; Calabrò, P.S.; Folino, A.; Tamburino, V.; Zappia, G.; Zimbone, S.M. Valorisation of Citrus Processing Waste: A Review. Waste Manag. 2018, 80, 252–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suri, S.; Singh, A.; Nema, P.K. Current Applications of Citrus Fruit Processing Waste: A Scientific Outlook. Appl. Food Res. 2022, 2, 100050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourbafrani, M.; Forgács, G.; Horváth, I.S.; Niklasson, C.; Taherzadeh, M.J. Production of Biofuels, Limonene and Pectin from Citrus Wastes. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 4246–4250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, M.R.; Widmer, W.W.; Grohmann, K. Simultaneous Saccharification and Fermentation of Citrus Peel Waste by Saccharomyces cerevisiae to Produce Ethanol. Process Biochem. 2007, 42, 1614–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battista, F.; Remelli, G.; Zanzoni, S.; Bolzonella, D. Valorization of Residual Orange Peels: Limonene Recovery, Volatile Fatty Acids, and Biogas Production. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 6834–6843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, S.; Swami Hulle, N.R. Citrus Pectins: Structural Properties, Extraction Methods, Modifications and Applications in Food Systems—A Review. Appl. Food Res. 2022, 2, 100215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, D.; Ren, S.; Man, Y.; Xiang, Z. Life Cycle Assessment of Hemicellulose Separation and Utilization from Black Liquor of a Hardwood Kraft Pulp Mill. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 8959–8968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratto, D.; Cavalloro, V.; Tumminelli, E.; Soffientini, I.; Martino, E.; Rossi, D.; Collina, S.; Rossi, P. From Waste to Worth: Transforming Winemaking Residues into High-Value Ingredients. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 5, 3956–3974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Joseph, N.; Abiodun, A.K.; Leh, C.P.; Lee, C.K. Time-Resolved Co-Fermentation Dynamics: Optimizing Fermentation Time for Energy-Efficient Lignocellulosic Ethanol Production from Oil Palm Empty Fruit Bunches. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2026, 92, 101922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vescovo, D.; Manetti, C.; Ruggieri, R.; Spizzirri, U.G.; Aiello, F.; Martuscelli, M.; Restuccia, D. The Valorization of Potato Peels as a Functional Ingredient in the Food Industry: A Comprehensive Review. Foods 2025, 14, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadidi, Y.; Frost, H.; Das, S.; Liao, W.; Draths, K.; Saffron, C.M. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment and Technoeconomic Analysis of Biomass-Derived Shikimic Acid Production. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 12218–12229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Z.Y.; Liew, P.Y.; Woon, K.S.; Tan, L.S.; Tamunaidu, P.; Klemes, J.J. Life-Cycle Environmental and Cost Analysis of Palm Biomass-Based Bio-Ethanol Production in Malaysia. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2021, 89, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kami Delivand, M.; Gnansounou, E. Life Cycle Environmental Impacts of a Prospective Palm-Based Biorefinery in Pará State-Brazil. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 150, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huailuek, N.; Silalertruksa, T.; Gheewala, S.H. Life Cycle Assessment and Cost-Benefit Analysis of Palm Biorefinery in Thailand for Different Empty Fruit Bunch (EFB) Management Scenarios. J. Sustain. Energy Environ. 2019, 10, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Srinophakun, T.R.; Suwajittanont, P. Techno-Economic Analysis of Bioethanol Production from Palm Oil Empty Fruit Bunch. Int. J. Technol. 2022, 13, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piarpuzán, D.; Quintero, J.A.; Cardona, C.A. Empty Fruit Bunches from Oil Palm as a Potential Raw Material for Fuel Ethanol Production. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 1130–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markom, M. The Effect of Various Pretreatment Methods on Empty Fruit Bunch for Glucose Production. Malays. J. Anal. Sci. 2016, 20, 1474–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Yu, Y.; Li, X.; Zhao, J.; Qu, Y.; Choo, Y.M.; Loh, S.K. Pretreatment of Empty Fruit Bunch from Oil Palm for Fuel Ethanol Production and Proposed Biorefinery Process. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 135, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangsang, N.; Rattanapan, U.; Thanapimmetha, A.; Srinopphakhun, P.; Liu, C.-G.; Zhao, X.-Q.; Bai, F.-W.; Sakdaronnarong, C. Chemical-Free Fractionation of Palm Empty Fruit Bunch and Palm Fiber by Hot-Compressed Water Technique for Ethanol Production. Energy Rep. 2019, 5, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiros, C.; Christakopoulos, P. Enhanced Ethanol Production from Brewer’s Spent Grain by a Fusarium Oxysporum Consolidated System. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2009, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizal, N.F.A.A.; Ibrahim, M.F.; Zakaria, M.R.; Abd-Aziz, S.; Yee, P.L.; Hassan, M.A. Pre-Treatment of Oil Palm Biomass for Fermentable Sugars Production. Molecules 2018, 23, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derman, E.; Abdulla, R.; Marbawi, H.; Sabullah, M.K. Oil Palm Empty Fruit Bunches as a Promising Feedstock for Bioethanol Production in Malaysia. Renew. Energy 2018, 129, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoyo-Castelazo, E.; Santoyo, E.; Zurita-García, L.; Camacho Luengas, D.A.; Solano-Olivares, K. Life Cycle Assessment of Bioethanol Production from Sugarcane Bagasse Using a Gasification Conversion Process: Bibliometric Analysis, Systematic Literature Review and a Case Study. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 219, 119414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, G.; Shastri, Y. Life-Cycle Assessment-Based Comparison of Different Lignocellulosic Ethanol Production Routes. Biofuels 2022, 13, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcentales-Bastidas, D.; Silva, C.; Ramirez, A.D. The Environmental Profile of Ethanol Derived from Sugarcane in Ecuador: A Life Cycle Assessment Including the Effect of Cogeneration of Electricity in a Sugar Industrial Complex. Energies 2022, 15, 5421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Chamorro, J.A.; Cara, C.; Romero, I.; Ruiz, E.; Romero-García, J.M.; Mussatto, S.I.; Castro, E. Ethanol Production from Brewers’ Spent Grain Pretreated by Dilute Phosphoric Acid. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 5226–5233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.S.; Yohannan, B.K.; Walker, G.M. Bioconversion of Brewer’s Spent Grains to Bioethanol. FEMS Yeast Res. 2008, 8, 1175–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, Y.A.d.; Fernandes, A.R.A.C.; Gurgel, L.V.A.; Baêta, B.E.L. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Early-Stage Technological Layouts for Brewers’ Spent Grain Upcycling: A Sustainable Approach for Adding Value to Waste. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 66, 105904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Li, B.; Xian, X.; Hu, Y.; Lin, X. Efficient Bioethanol Production from Spent Coffee Grounds Using Liquid Hot Water Pretreatment without Detoxification. Fermentation 2024, 10, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-G.; Cho, E.-J.; Maskey, S.; Nguyen, D.-T.; Bae, H.-J. Value-Added Products from Coffee Waste: A Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Biswal, B.K.; Zhang, J.; Balasubramanian, R. Hydrothermal Treatment of Biomass Feedstocks for Sustainable Production of Chemicals, Fuels, and Materials: Progress and Perspectives. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 7193–7294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowpada, S.R.D. Production and Optimization of Ethanol Production from Spent Tea Waste Using Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Int. J. Adv. Res. Ideas Innov. Technol. 2020, 6, 442–446. [Google Scholar]

- Chintagunta, A.D.; Jacob, S.; Banerjee, R. Integrated Bioethanol and Biomanure Production from Potato Waste. Waste Manag. 2016, 49, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, Y.; Meng, Q. Effect of Steam Explosion of Oil Palm Frond and Empty Fruit Bunch on Nutrient Composition and Ruminal Fermentation Characteristics. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2020, 52, 1223–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrameda, H.J.C.; Requiso, P.J.; Alfafara, C.G.; Nayve, F.R.P., Jr.; Ventura, R.L.G.; Ventura, J.-R.S. Hydrolysate Production from Sugarcane Bagasse Using Steam Explosion and Sequential Steam Explosion-Dilute Acid Pretreatment for Polyhydroxyalkanoate Fermentation. Bioact. Carbohydr. Diet. Fibre 2023, 30, 100376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scapini, T.; dos Santos, M.S.N.; Bonatto, C.; Wancura, J.H.C.; Mulinari, J.; Camargo, A.F.; Klanovicz, N.; Zabot, G.L.; Tres, M.V.; Fongaro, G.; et al. Hydrothermal Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass for Hemicellulose Recovery. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 342, 126033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satari, B.; Karimi, K.; Kumar, R. Cellulose Solvent-Based Pretreatment for Enhanced Second-Generation Biofuel Production: A Review. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2019, 3, 11–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Tye, Y.Y.; Hemashin, T.; Leh, C.P. Feasibility of Use Limited Data to Establish a Relationship between Chemical Composition and the Enzymatic Glucose Yield Using Machine Learning. Biomass Bioenergy 2025, 200, 107956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodeur, G.; Yau, E.; Badal, K.; Collier, J.; Ramachandran, K.B.; Ramakrishnan, S. Chemical and Physicochemical Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass: A Review. Enzym. Res. 2011, 2011, 787532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruah, J.; Nath, B.K.; Sharma, R.; Kumar, S.; Deka, R.C.; Baruah, D.C.; Kalita, E. Recent Trends in the Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass for Value-Added Products. Front. Energy Res. 2018, 6, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, D.; Park, H.; Jang, B.-K.; Ju, Y.; Shin, M.H.; Oh, E.J.; Lee, E.J.; Kim, S.R. Recent Advances in the Biological Valorization of Citrus Peel Waste into Fuels and Chemicals. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 323, 124603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negro, V.; Mancini, G.; Ruggeri, B.; Fino, D. Citrus Waste as Feedstock for Bio-Based Products Recovery: Review on Limonene Case Study and Energy Valorization. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 214, 806–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, Y.L.; Keppler, J.K.; Dinani, S.T.; Chen, W.N.; Boom, R. Brewers’ Spent Grain Proteins: The Extraction Method Determines the Functional Properties. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2024, 94, 103666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, I.; Argenziano, R.; Borselleca, E.; Moccia, F.; Panzella, L.; Pezzella, C. Cascade Disassembling of Spent Coffee Grounds into Phenols, Lignin and Fermentable Sugars En Route to a Green Active Packaging. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 334, 125998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Tao, L.; Wyman, C.E. Strengths, Challenges, and Opportunities for Hydrothermal Pretreatment in Lignocellulosic Biorefineries. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefin. 2018, 12, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modenbach, A.A.; Nokes, S.E. The Use of High-Solids Loadings in Biomass Pretreatment—A Review. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2012, 109, 1430–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.H.; Park, H.M.; Kim, D.H.; Park, Y.-C.; Seo, J.-H.; Kim, K.H. Combination of High Solids Loading Pretreatment and Ethanol Fermentation of Whole Slurry of Pretreated Rice Straw to Obtain High Ethanol Titers and Yields. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 198, 861–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, J.; Marwah, H.; Kumar, C. Synthetic Biology and Metabolic Engineering Paving the Way for Sustainable Next-Gen Biofuels: A Comprehensive Review. Energy Adv. 2025, 4, 1209–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafa, M.S.; Pletschke, B.I.; Malgas, S. Defining the Frontiers of Synergism between Cellulolytic Enzymes for Improved Hydrolysis of Lignocellulosic Feedstocks. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaya, J.; Chan, K.H.; Mills-Lamptey, B.; Chuck, C.J. Developing a Biorefinery from Spent Coffee Grounds Using Subcritical Water and Hydrothermal Carbonisation. Biomass Conv. Biorefin. 2023, 13, 1279–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, A.; Lee, T.S. Converting Sugars to Biofuels: Ethanol and Beyond. Bioengineering 2015, 2, 184–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, Y.; Hemashini, T.; Leh, C.P. Comparative Energy Assessment and Net Energy Return Analysis of Non-Wood Lignocellulosic Bioethanol Systems. Cellulose 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Bereche, R.; Ensinas, A.V.; Modesto, M.; Nebra, S.A. Double-Effect Distillation and Thermal Integration Applied to the Ethanol Production Process. Energy 2015, 82, 512–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Merchán, A.M.; Moreno-Tost, R.; Malpartida-García, I.; García-Sancho, C.; Mérida-Robles, J.M.; Maireles-Torres, P. An Integrated Biorefinery Approach Based on Spent Coffee Grounds Valorization. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 528, 146716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Castrillon, C.; Leon, J.A.; Palacios-Bereche, M.C.; Palacios-Bereche, R.; Nebra, S.A. Improvements in Fermentation and Cogeneration System in the Ethanol Production Process: Hybrid Membrane Fermentation and Heat Integration of the Overall Process through Pinch Analysis. Energy 2018, 156, 468–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Ghosh, A.; Bbosa, D.; Brown, R.; Wright, M.M. Comparative Techno-Economic, Uncertainty and Life Cycle Analysis of Lignocellulosic Biomass Solvent Liquefaction and Sugar Fermentation to Ethanol. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 16515–16524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stichnothe, H.; Azapagic, A. Bioethanol from Waste: Life Cycle Estimation of the Greenhouse Gas Saving Potential. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2009, 53, 624–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonini, D.; Albizzati, P.F.; Astrup, T.F. Environmental Impacts of Food Waste: Learnings and Challenges from a Case Study on UK. Waste Manag. 2018, 76, 744–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, K.; Cruz, D.; Li, J.; Agyei Boakye, A.A.; Park, H.; Tiller, P.; Mittal, A.; Johnson, D.K.; Park, S.; Yao, Y. Life-Cycle Assessment of Sustainable Aviation Fuel Derived from Paper Sludge. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 8379–8390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, A.B.; Muñoz, E. Life Cycle Assessment of Second Generation Ethanol Derived from Banana Agricultural Waste: Environmental Impacts and Energy Balance. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 710–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez-Arredondo, H.I.; Ruiz-Colorado, A.A.; De Oliveira, S. Ethanol Production Process from Banana Fruit and Its Lignocellulosic Residues: Energy Analysis. Energy 2010, 35, 3081–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-García, P. Activated Carbon from Lignocellulosics Precursors: A Review of the Synthesis Methods, Characterization Techniques and Applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 1393–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwamba, B.W.; Brobbey, M.S.; Maritz, R.F.; Leodolff, B.; Peters, S.; Teke, G.M.; Mapholi, Z. Valorising Waste Cooking Oil and Citrus Peel Waste for Sustainable Soap Production: A Techno-Economic and Environmental Life Cycle Assessment Study. Waste Biomass Valor. 2025, 16, 6205–6220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machin Ferrero, L.M.; Wheeler, J.; Mele, F.D. Life Cycle Assessment of the Argentine Lemon and Its Derivatives in a Circular Economy Context. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 29, 672–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konti, A.; Kekos, D.; Mamma, D. Life Cycle Analysis of the Bioethanol Production from Food Waste—A Review. Energies 2020, 13, 5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasri, N.F.; Hanafiah, M.M.; Harun, S.N.; Chong, J.W.; Hassan, F.M. Life Cycle Assessment of Biofuel Production from Sugarcane Bagasse. In E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2024; Volume 599, p. 04002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rewlay-ngoen, C.; Papong, S.; Onbhuddha, R.; Thanomnim, B. Evaluation of the Environmental Performance of Bioethanol from Cassava Pulp Using Life Cycle Assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 284, 124741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhai, Z.; Feng, Y.; Geng, Z. Life Cycle Assessment for Bioethanol Production from Whole Plant Cassava by Integrated Process. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 269, 121902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebner, J.; Babbitt, C.; Winer, M.; Hilton, B.; Williamson, A. Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Impacts of a Novel Process for Converting Food Waste to Ethanol and Co-Products. Appl. Energy 2014, 130, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakelly, N.; Pérez-Cardona, J.R.; Deng, S.; Maani, T.; Li, Z.; Sutherland, J.W. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Bioethanol Production from Different Generations of Biomass and Waste Feedstocks. Procedia CIRP 2023, 116, 630–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogo, Y.; Habibi, S.; MacLean, H.L.; Joshi, S.V. Environmental Implications of Municipal Solid Waste-Derived Ethanol. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muiruri, J.K.; Yeo, J.C.C.; Zhu, Q.; Ye, E.; Loh, X.J.; Li, Z. Poly(Hydroxyalkanoates): Production, Applications and End-of-Life Strategies–Life Cycle Assessment Nexus. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 3387–3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, T.; Rajaeifar, M.A.; Kenny, A.; Hainsworth, C.; del Pino, V.; del Valle Inclán, Y.; Povoa, I.; Mendonça, P.; Brown, L.; Smallbone, A.; et al. Life Cycle Assessment of Microalgae-Derived Biodiesel. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2023, 28, 590–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canabarro, N.I.; Silva-Ortiz, P.; Nogueira, L.A.H.; Cantarella, H.; Maciel-Filho, R.; Souza, G.M. Sustainability Assessment of Ethanol and Biodiesel Production in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Guatemala. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 171, 113019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez Aldama, D.; Grassauer, F.; Zhu, Y.; Ardestani-Jaafari, A.; Pelletier, N. Allocation Methods in Life Cycle Assessments (LCAs) of Agri-Food Co-Products and Food Waste Valorization Systems: Systematic Review and Recommendations. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 421, 138488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midolo, G.; Cutuli, G.; Porto, S.M.C.; Ottolina, G.; Paini, J.; Valenti, F. LCA Analysis for Assessing Environmenstal Sustainability of New Biobased Chemicals by Valorising Citrus Waste. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alengebawy, A.; Ran, Y.; Osman, A.I.; Jin, K.; Samer, M.; Ai, P. Anaerobic Digestion of Agricultural Waste for Biogas Production and Sustainable Bioenergy Recovery: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2024, 22, 2641–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, I.L.M.; Cardoso, T.F.; Souza, N.R.D.; Watanabe, M.D.B.; Carvalho, D.J.; Bonomi, A.; Junqueira, T.L. Electricity Production from Sugarcane Straw Recovered Through Bale System: Assessment of Retrofit Projects. Bioenergy Res. 2019, 12, 865–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larnaudie, V.; Ferrari, M.D.; Lareo, C. Life Cycle Assessment of Ethanol Produced in a Biorefinery from Liquid Hot Water Pretreated Switchgrass. Renew. Energy 2021, 176, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manakas, P.; Balafoutis, A.T.; Kottaridi, C.; Vlysidis, A. Sustainability Assessment of Orange Peel Waste Valorization Pathways from Juice Industries. Biomass Conv. Biorefin. 2025, 15, 6525–6544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; Xiros, C.; Tillman, A.-M. Life Cycle Impacts of Ethanol Production from Spruce Wood Chips under High-Gravity Conditions. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2016, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsangas, M.; Papamichael, I.; Banti, D.; Samaras, P.; Zorpas, A.A. LCA of Municipal Wastewater Treatment. Chemosphere 2023, 341, 139952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, F.; Abebe, G.; Emenike, C.; Martynenko, A. Sustainable Utilization of Apple Pomace: Technological Aspects and Emerging Applications. Food Res. Int. 2025, 220, 117149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijbregts, M.A.J.; Steinmann, Z.J.N.; Elshout, P.M.F.; Stam, G.; Verones, F.; Vieira, M.; Zijp, M.; Hollander, A.; van Zelm, R. ReCiPe2016: A Harmonised Life Cycle Impact Assessment Method at Midpoint and Endpoint Level. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2017, 22, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijbregts, M.A.J.; Hellweg, S.; Frischknecht, R.; Hendriks, H.W.M.; Hungerbühler, K.; Hendriks, A.J. Cumulative Energy Demand As Predictor for the Environmental Burden of Commodity Production. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 2189–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frischknecht, R. Life Cycle Inventory Methodology and Databases. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2010, 15, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulle, C.; Margni, M.; Patouillard, L.; Boulay, A.-M.; Bourgault, G.; De Bruille, V.; Cao, V.; Hauschild, M.; Henderson, A.; Humbert, S.; et al. IMPACT World+: A Globally Regionalized Life Cycle Impact Assessment Method. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2019, 24, 1653–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, A.A.R.; Bardant, T.B.; Muryanto, M.; Triwahyuni, E.; Ishizaki, R.; Dahnum, D.; Putri, A.M.H.; Irawan, Y.; Maryana, R.; Sudiyani, Y.; et al. Influence of Avoided Biomass Decay on a Life Cycle Assessment of Oil Palm Residues-Based Ethanol. Energ. Ecol. Environ. 2024, 9, 344–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Lee, K.T. Parallel Production of Biodiesel and Bioethanol in Palm-Oil-Based Biorefineries: Life Cycle Assessment on the Energy and Greenhouse Gases Emissions. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefin. 2011, 5, 132–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaskan, P.; Pachón, E.R.; Gnansounou, E. Techno-Economic and Life-Cycle Assessments of Biorefineries Based on Palm Empty Fruit Bunches in Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 3655–3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teow, J.W. Comparisons of Life Cycle Assessment of Bioethanol Production from Oil Palm Empty Fruit Bunch And Microalgae in Malaysia. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, Petaling Jaya, Malaysia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kermani, M.; Celebi, A.D.; Wallerand, A.S.; Ensinas, A.V.; Kantor, I.D.; Maréchal, F. Techno-Economic and Environmental Optimization of Palm-Based Biorefineries in the Brazilian Context. In Computer Aided Chemical Engineering; Espuña, A., Graells, M., Puigjaner, L., Eds.; Elsevier: Barcelona, Spain, 2017; Volume 40, pp. 2611–2616. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, R.; Roy, O. Sustainable Energy-Efficient Conversion of Waste Tea Leaves to Reducing Sugar: Optimization and Life-Cycle Environmental Impact Assessment. J. Environ. Eng. Landsc. Manag. 2022, 30, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafyan, R.H.; Mohanarajan, J.; Uppal, M.; Kumar, V.; Narisetty, V.; Maity, S.K.; Sadhukhan, J.; Gadkari, S. Integrated Biorefinery for Bioethanol and Succinic Acid Co-Production from Bread Waste: Techno-Economic Feasibility and Life Cycle Assessment. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 301, 118033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebolledo-Leiva, R.; Estévez, S.; Hernández, D.; Feijoo, G.; Moreira, M.T.; González-García, S. Apple Pomace Integrated Biorefinery for Biofuels Production: A Techno-Economic and Environmental Sustainability Analysis. Resources 2024, 13, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-García, S.; Morales, P.C.; Gullón, B. Estimating the Environmental Impacts of a Brewery Waste–Based Biorefinery: Bio-Ethanol and Xylooligosaccharides Joint Production Case Study. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 123, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourbafrani, M.; McKechnie, J.; MacLean, H.L.; Saville, B.A. Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Impacts of Ethanol, Biomethane and Limonene Production from Citrus Waste. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 015007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd YUSOF, S.J.H.; Roslan, A.M.; Ibrahim, K.N.; Syed ABDULLAH, S.S.; Zakaria, M.R.; Hassan, M.A.; Shirai, Y. Life Cycle Assessment for Bioethanol Production from Oil Palm Frond Juice in an Oil Palm Based Biorefinery. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt Rivera, X.C.; Gallego-Schmid, A.; Najdanovic-Visak, V.; Azapagic, A. Life Cycle Environmental Sustainability of Valorisation Routes for Spent Coffee Grounds: From Waste to Resources. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 157, 104751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narisetty, V.; Nagarajan, S.; Gadkari, S.; Ranade, V.V.; Zhang, J.; Patchigolla, K.; Bhatnagar, A.; Kumar Awasthi, M.; Pandey, A.; Kumar, V. Process Optimization for Recycling of Bread Waste into Bioethanol and Biomethane: A Circular Economy Approach. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 266, 115784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebolledo-Leiva, R.; Estévez, S.; Hernández, D.; Feijoo, G.; Moreira, M.T.; González-García, S. Environmental Insights of Bioethanol Production and Phenolic Compounds Extraction from Apple Pomace-Based Biorefinery. Clean. Circ. Bioecon. 2024, 9, 100125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, J.P.M.; Coleta, J.R.; Arruda, L.C.M.; Silva, G.A.; Kulay, L. Comparative Analysis of Electricity Cogeneration Scenarios in Sugarcane Production by LCA. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2014, 19, 814–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lask, J.; Wagner, M.; Trindade, L.M.; Lewandowski, I. Life Cycle Assessment of Ethanol Production from Miscanthus: A Comparison of Production Pathways at Two European Sites. GCB Bioenergy 2019, 11, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosalvitr, P.; Cuéllar-Franca, R.M.; Smith, R.; Azapagic, A. Environmental and Economic Sustainability Assessment of Biofuels from Valorising Spent Coffee Grounds. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2025, 19, 100347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariana, O.-S.; Alzate, C.; Ariel, C. Comparative Environmental Life Cycle Assessment of Orange Peel Waste in Present Productive Chains. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 322, 128814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffey, J.; Collins, M.N.; Styles, D. Review of Methodological Decisions in Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Biorefinery Systems across Feedstock Categories. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 358, 120813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Muchangos, L.S.; Mejia, C.; Gupta, R.; Sadreghazi, S.; Kajikawa, Y. A Systematic Review of Life Cycle Assessment and Environmental Footprint for the Global Coffee Value Chain. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2025, 111, 107740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouter, A.; Duval-Dachary, S.; Besseau, R. Life Cycle Assessment of Liquid Biofuels: What Does the Scientific Literature Tell Us? A Statistical Environmental Review on Climate Change. Biomass Bioenergy 2024, 190, 107418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muench, S.; Guenther, E. A Systematic Review of Bioenergy Life Cycle Assessments. Appl. Energy 2013, 112, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh-Bandbafha, H.; Aghbashlo, M.; Tabatabaei, M. Life Cycle Assessment of Bioenergy Product Systems: A Critical Review. E-Prime-Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2021, 1, 100015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, E.W.; Chester, M.V.; Vergara, S.E. Attributional and Consequential Life-Cycle Assessment in Biofuels: A Review of Recent Literature in the Context of System Boundaries. Curr. Sustain. Renew. Energy Rep. 2015, 2, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Menna, F.; Davis, J.; Östergren, K.; Unger, N.; Loubiere, M.; Vittuari, M. A Combined Framework for the Life Cycle Assessment and Costing of Food Waste Prevention and Valorization: An Application to School Canteens. Agric. Econ. 2020, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyttä, V.; Roitto, M.; Astaptsev, A.; Saarinen, M.; Tuomisto, H.L. Review and Expert Survey of Allocation Methods Used in Life Cycle Assessment of Milk and Beef. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2022, 27, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenboom, J.-G.; Langer, R.; Traverso, G. Bioplastics for a Circular Economy. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2022, 7, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M.; Iqbal, H.M.N. Recent Advancements in the Life Cycle Analysis of Lignocellulosic Biomass. Curr. Sustain. Renew. Energy Rep. 2020, 7, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feedstock | Food Industry Source/Process | Typical Availability (Scale & Region) | Typical Composition Range (%) | Key Physicochemical Features Relevant to Bioethanol | Current Disposal | Typical Pretreatment in Bioethanol Studies | Representative Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oil palm empty fruit bunches (OPEFB) | Palm oil milling; sterilization and threshing residues (stalks after fruit removal) | ≈80–100 Mt yr−1 globally; ≈21 Mt yr−1 in Malaysia (2018); ≈1.07 t OPEFB per t crude palm oil | Cellulose ≈50–58; hemicellulose ≈21–30; lignin ≈18–24; ash ≈3–5; extractives ≈3–5 | Fibrous residue with high holocellulose and moderate lignin contents; very high moisture content (>60% wet basis), low bulk density and silica-rich fibres that are abrasive and prone to biological degradation during storage | Mainly combusted on site for process steam and power; also used as mulch and soil amendment; open dumping or simple composting still occurs at some mills | Dilute acid, alkaline, hydrothermal/steam explosion, organosolv and biological pretreatments, typically followed by enzymatic hydrolysis and ethanolic fermentation | [49,50,51,52,53,54,55] |

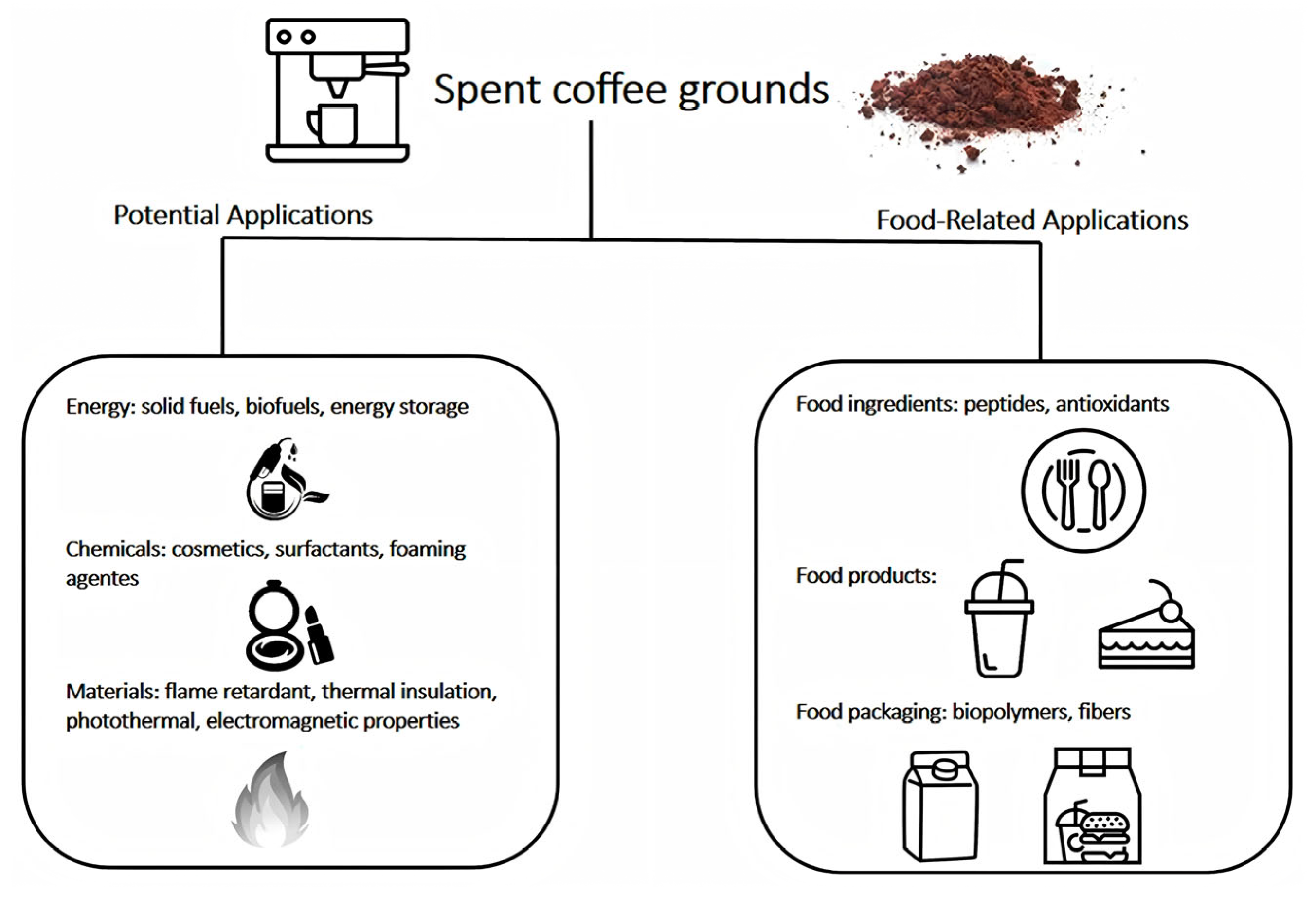

| Spent coffee grounds (SCG) | Instant coffee and brewed coffee production; solid residue after hot water extraction of roasted ground coffee | Global SCG estimated at ≈6–18 Mt yr−1 (wet basis), with ≈6 Mt yr−1 most frequently cited; ≈0.65 t SCG per t green coffee | Cellulose ≈20–30; hemicellulose ≈20–30; lignin ≈10–25; lipids ≈10–20; proteins ≈10–17; ash ≈1–5 | Fine, particulate residue with high oil and protein contents, substantial volatile and phenolic fractions and relatively high energy density; particles tend to be hydrophobic and to agglomerate during handling | Predominantly landfilled or incinerated; minor use as low-grade solid fuel, compost, animal feed additive, adsorbent and filler in construction or polymer composites | Dilute acid or hydrothermal pretreatment, often combined with alkali-assisted delipidation and enzymatic hydrolysis; subsequent dark fermentation or ethanolic fermentation for fuel production | [56,57,58,59,60,61,62] |

| Sugarcane bagasse (SCB) | Sugar milling; fibrous residue after juice extraction from sugarcane stalks | ≈279–700 Mt yr−1 SCB globally depending on estimation; sugarcane ≈1.6 Gt yr−1 with bagasse ≈30% of cane mass | Cellulose ≈32–50; hemicellulose ≈20–32; lignin ≈17–32; ash ≈1–9; minor extractives | Coarse, fibrous matrix with relatively high lignin and moderate ash contents; high moisture at mill outlet, good handling properties but prone to compaction in bales; ash contains silica and alkali metals that influence combustion and pretreatment | Mainly combusted on site for steam and electricity; surplus sometimes exported as fuel; smaller fractions used for pulp and paper, fibreboards and composite materials | Steam explosion, dilute acid, alkaline and organosolv pretreatments, followed by enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation; widely studied in integrated first- and second-generation ethanol concepts | [63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72] |

| Brewers’ spent grain (BSG) | Brewing; insoluble residue of malted barley and adjuncts after mashing/lautering | ≈30–40 Mt yr−1 BSG globally; ≈20 kg BSG per hL beer; 2020 regional production: Americas ≈12.3 Mt, Asia ≈11.0 Mt, Europe ≈10.0 Mt | Cellulose ≈15–25; non-cellulosic polysaccharides (mainly arabinoxylans) ≈20–30; lignin ≈20–30; proteins ≈15–30; lipids ≈5–10; ash ≈2–5 | Moist, highly biodegradable fibrous residue with high protein and fibre contents; rapidly spoils under ambient conditions; sticky mash-like consistency but a suitable substrate for microbial growth and enzymatic saccharification | Predominantly used fresh or ensiled as cattle feed; also composted or digested anaerobically; emerging higher-value uses in food ingredients, biopolymers and adsorbents | Hydrothermal and dilute acid pretreatments, alkaline fractionation and enzymatic hydrolysis, followed by separate or simultaneous saccharification and fermentation for bioethanol and/or biogas | [73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81] |

| Tea waste | Tea beverage and instant tea production; spent tea leaves and factory tea dust after hot water extraction | Global tea consumption increased ≈2.1-fold between 1995 and 2015; spent tea leaf sludge accounts for ≈90% of total tea waste; total tea waste generation is in the multi-Mt yr−1 range | Cellulose ≈20–35; hemicellulose ≈15–30; water-soluble fraction (including phenolic, tannin and other extractives) ≈25–40; ash ≈3–7 | Heterogeneous fine particles rich in polyphenols, caffeine and other extractives; relatively high ash and mineral contents; exhibits good sorption capacity and a lignocellulosic backbone that can be saccharified if phenolic inhibition is controlled | Typically landfilled or used as low-grade compost; more recently explored as feedstock for adsorbents, biochar, catalyst supports and biofuel production | Acid, alkaline or hydrothermal pretreatments followed by enzymatic hydrolysis and ethanolic fermentation; some studies investigate seawater-based fermentation systems | [82,83,84,85,86] |

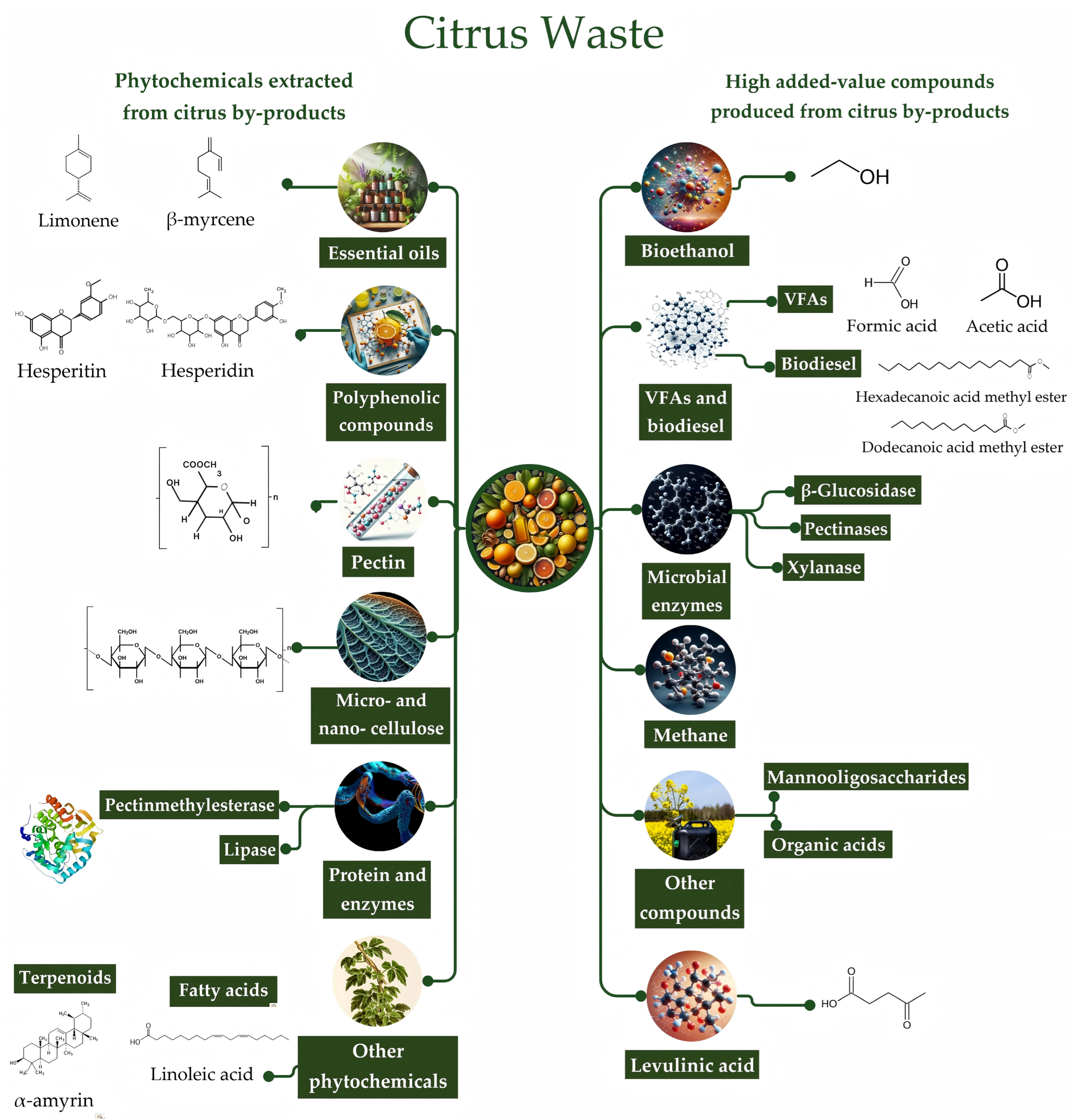

| Citrus processing waste | Citrus juice, marmalade and essential oil production; peel, pulp and rag remaining after juice extraction and oil recovery | Global citrus production ≈124 Mt yr−1; industrial processing generates ≈50% waste, corresponding to tens of Mt yr−1 of peel–pomace, mainly in Brazil, China, the Mediterranean region and US citrus belts | Cellulose ≈8–55; hemicellulose ≈0.3–26; lignin ≈0.5–21.6; rich in pectin and soluble sugars; minor protein and lipid fractions | Residue with high pectin and soluble sugar contents, substantial essential oils (notably limonene) and polyphenols; relatively low lignin compared with many agro-residues; high moisture and rapid spoilage potential | Traditionally used as low-value cattle feed, soil amendment or compost; large fractions still discarded; increasingly examined in integrated biorefineries for pectin, essential oils, bioethanol and biogas | Dilute acid or hydrothermal pretreatment to solubilise hemicellulose and pectin, often coupled with detoxification or limonene removal, followed by enzymatic hydrolysis and ethanolic fermentation; some schemes integrate pectin/essential oil recovery with ethanol production | [87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94] |

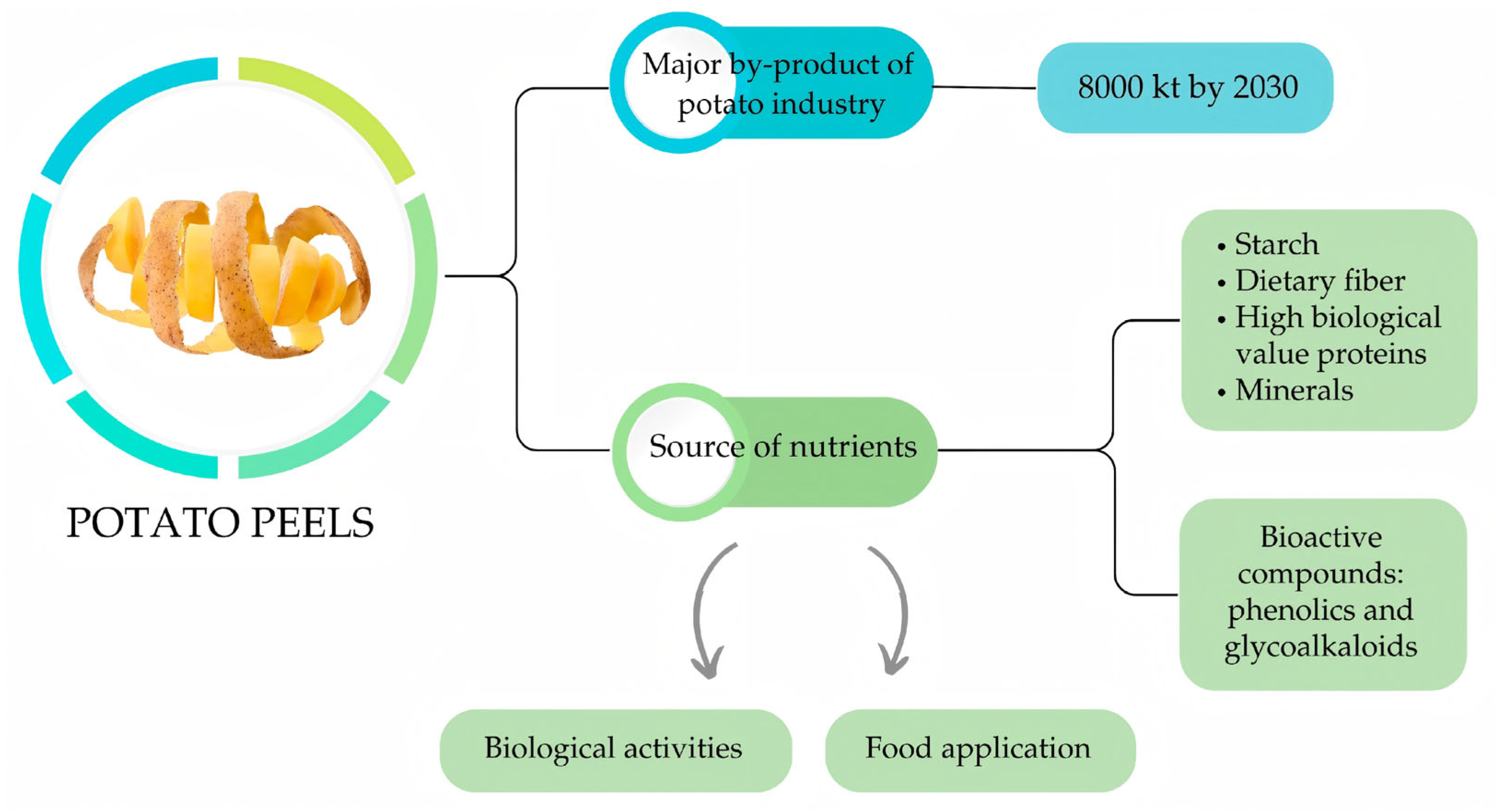

| Potato peel waste (PPW) | Potato processing for chips, fries, mashed and dehydrated products; outer peel and cortical tissues removed during washing, peeling and trimming | Global potato production ≈370 Mt yr−1; industrial peeling generates ≈15–40% of incoming tuber mass as peel and trimmings, corresponding to several Mt yr−1 of PPW, especially in Europe, North America and East Asia | Starchy–lignocellulosic matrix: starch ≈20–40; cellulose ≈10–20; hemicellulose ≈5–15; lignin ≈10–20; proteins ≈8–15; lipids ≈1–5; ash ≈3–8 | High-moisture, rapidly putrescible residue with high loads of starch, soluble sugars and phenolic compounds including glycoalkaloids; thin heterogeneous particles that are well suited to enzymatic saccharification once starch and structural carbohydrates are accessed | Commonly used as low-value animal feed or compost; significant quantities still discharged with solid waste or wastewater; increasingly considered as a biorefinery feedstock for polyphenols, bioethanol and biogas | Thermal, dilute acid, alkaline and thermo-chemical pretreatments, typically combined with amylolytic and cellulolytic enzymatic hydrolysis and yeast-based ethanolic fermentation; recent studies focus on multi-enzyme cocktails and process integration | [95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102] |

| Feedstock | Food Industry Segment | Country/Region | Product Slate | Main Conversion Route | Pretreatment & Hydrolysis | Fermentation Configuration | Scale | System Boundary in LCA/TEA | Co-Product Handling | FU & Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EFB | Palm oil mill residue | Malaysia | Fuel ethanol + surplus electricity | Biochemical lignocellulosic ethanol | Dilute H2SO4 pretreatment, neutralization with NH3; enzymatic hydrolysis in stirred reactors, ≈90% cellulose to glucose | SHF with Zymomonas mobilis; beer distillation and rectification to fuel ethanol | Conceptual industrial biorefinery | Cradle-to-gate: nursery, plantation, milling, biorefinery, wastewater, cogeneration | Lignin, sludge and biogas to CHP; surplus power exported | FU 1 t bioethanol; ReCiPe Midpoint (H)–GWP, acidification, eutrophication, ecotoxicity | [135] |

| EFB | Palm oil mill residue | Brazil | Fuel ethanol | EFB → dilute acid pretreatment → enzymatic saccharification/fermentation → distillation/dehydration | Dilute acid pretreatment and enzymatic hydrolysis; parameters compiled from literature (no new experiments) | Conventional yeast fermentation; ethanol recovery by distillation | Modelled plant (student project) | well-to-tank + well-to-wheel (comparison) | Co-products and residues treated as in standard palm oil mills | FU 1 kg ethanol; CML-style midpoint indicators | [136] |

| EFB | Palm oil mill residue | Thailand | Ethanol + cogenerated heat & power | Biochemical ethanol integrated in palm biorefinery | Dilute acid pretreatment; enzyme production modelled from literature sources | Conventional yeast fermentation and distillation | Conceptual palm biorefinery scenarios | Cradle-to-gate LCA of several EFB options; one scenario is EFB–ethanol + cogeneration | Electricity and heat from lignin/biogas displace grid power (credit) | FU 1 t EFB; midpoint LCA (GWP, acidification, eutrophication, etc.) | [137] |

| EFB | Palm oil mill residue | Thailand | Fuel ethanol | Biochemical ethanol (TEA + flowsheet) | Hot water, hot compressed water or alkaline H2O2 pretreatment; enzymatic hydrolysis | SSF with yeast | Commercial (10,000 L d−1, 99.5 wt% ethanol) | Gate-to-gate: EFB at plant gate to anhydrous ethanol; separate TEA | Lignin-rich residues assumed to supply process heat | TEA only; primary metrics are energy use and cost per litre | [138] |

| EFB | Palm oil mill residue | Indonesia (conceptual) | Fuel ethanol | Biochemical ethanol | NaOH pretreatment of EFB; washing and neutralization; enzymatic hydrolysis to glucose | Batch fermentation with Saccharomyces cerevisiae; distillation | Lab/pilot | No full LCA; mass and energy balances reported for later LCI use | Lignin residue considered as boiler fuel | Not LCA; reports ethanol yield and energy per kg EFB | [139] |

| EFB | Palm oil mill residue | Malaysia | Fuel ethanol | Biochemical ethanol | Comparison of steam, dilute acid, alkaline and scCO2 pretreatments prior to enzymatic hydrolysis | SSF with yeast suggested, but study focuses on sugar release | Lab | No full LCA; pretreatment energy and chemical use reported | Residues implied as solid fuel | Not LCA; provides yields and energy inputs | [140,141] |

| EFB | Palm oil mill residue | SE Asia | Sugars + ethanol | Biochemical ethanol; multiple routes | Chemical-free fractionation (water/organosolv) of EFB and palm fibre; enzymatic saccharification | Conventional yeast fermentation assumed | Conceptual | No LCA; highlights potential benefits of chemical-free pretreatment | Lignin-rich solids and fibres proposed for energy or materials | No FU; qualitative comparison of options | [142] |

| EFB | Palm oil mill residue | Malaysia/Thailand | Fuel ethanol from oil palm biomass (EFB, trunk) | Biochemical ethanol | Dilute acid/alkaline pretreatment and enzymatic hydrolysis of EFB and trunk; consolidated process design | SSF with yeast at high solids under microaerobic conditions | Lab–pilot | No single LCA; process data used in later palm biomass LCA and TEA | Lignin and residues envisaged for CHP | Not LCA; ethanol yield (g kg−1 dry biomass) and energy balances | [143] |

| EFB | Palm oil mill residue | Malaysia | Sugars + ethanol (conceptual) | Biochemical ethanol with chemical-free pretreatment | Water-based fractionation of EFB and mesocarp fibre (no H2SO4); enzymatic hydrolysis to sugars | Conventional yeast fermentation considered as downstream option | Conceptual | No LCA; focuses on pretreatment severity vs. sugar yield | Cellulose-rich pulp and lignin proposed for materials or energy | No FU; qualitative discussion of reduced chemical load | [144] |

| EFB | Palm oil mill residue | General (review) | Biofuels (bioethanol as key product) | Biochemical & thermochemical routes | Review of alkaline, dilute acid, organosolv, steam explosion and biological pretreatments before enzymatic hydrolysis | SHF/SSF with S. cerevisiae and co-cultures; distillation assumed | Review | No quantitative LCA; compiles yield and energy data | Co-utilization of lignin for heat/power generally assumed | Not applicable; qualitative synthesis of impact data | [145] |

| Sugarcane bagasse | Sugar/ethanol industry residue | Mexico | 2G ethanol (bagasse) | Biochemical lignocellulosic ethanol | Dilute acid or steam explosion pretreatment; enzymatic hydrolysis (several configurations) | Yeast fermentation of hydrolysate; distillation | Modelled industrial plant | Cradle-to-gate LCA integrated with process design | Lignin-rich residue for power; sometimes excess exported | FU 1 MJ or 1 L ethanol; midpoint LCA incl. GWP, acidification, eutrophication, land use | [146] |

| Sugarcane bagasse | Sugar/ethanol industry | India | 2G ethanol | Biochemical ethanol (dilute acid) | Conventional vs. modified dilute acid pretreatment of rice straw and bagasse; enzymatic hydrolysis | SSF with yeast; distillation to fuel-grade ethanol | Modelled industrial plant | Cradle-to-gate LCA + life cycle costing for alternative dilute acid routes | Lignin-rich residues fired in boiler; excess power credited | FU 1 L ethanol; CML midpoint indicators (GWP, AP, EP, etc.) | [147] |

| Sugarcane bagasse | Sugar/ethanol industry | Brazil | 2G ethanol (vs 1G) | Biochemical ethanol (integrated 1G + 2G) | Steam explosion or dilute acid pretreatment; enzymatic hydrolysis integrated into existing sugar–ethanol mills | Fermentation of C6 and partially of C5 sugars; distillation in common plant | Industrial scenarios | Cradle-to-gate comparison of 1G vs. 2G ethanol; focus on GHG and land use | Surplus electricity from bagasse/lignin to grid; vinasse as fertilizer | FU 1 km driven or 1 MJ ethanol; GWP, fossil energy demand, land occupation | [148] |

| Brewer’s spent grain (BSG) | Brewing industry | EU (conceptual plant) | Fuel ethanol from BSG | Biochemical ethanol | H3PO4 pretreatment (varied loadings); enzymatic hydrolysis with multienzyme cocktails | Separate hydrolysis and fermentation with yeast; distillation | Lab/pilot | No LCA; detailed mass and energy balances for LCI | Solid residues considered as fuel or animal feed | Not LCA; ethanol yield (L kg−1 dry BSG) and energy efficiency | [149] |

| BSG | Brewing industry | Europe | Fuel ethanol from BSG | Biochemical ethanol | Steam explosion to disrupt grains; enzymatic hydrolysis | SSF with S. cerevisiae; microaerobic conditions | Lab | No LCA; reports process yields and energy needs | Residual solids proposed for combustion | Not LCA; basis for later environmental assessment | [150] |

| BSG | Brewing industry | Brazil/global (conceptual) | Ethanol + other biorefinery products | Integrated BSG biorefinery | Layouts including dilute acid + enzymatic hydrolysis for ethanol vs. protein/chemicals routes | Conventional yeast fermentation in ethanol-oriented layout | Modelled industrial biorefineries | Cradle-to-gate comparative LCA of alternative BSG layouts | Protein concentrates and combusted residues treated as co-products | FU per kg BSG; midpoint LCA (GWP, respiratory inorganics, eutrophication) | [151] |

| SCG | Coffee shops/soluble coffee industry | China | Fuel ethanol from SCG | Biochemical ethanol with LHW pretreatment | Liquid hot water (180 °C, 20 min, S:L = 1:6); soluble sugars and mannans retained in liquor | Batch fermentation of hydrolysate with S. cerevisiae; ethanol ≈15 g L−1 | Lab | Not LCA; discusses water savings from high solids loading | Solid residue suggested as fuel or material; not quantified | No FU; process yields and qualitative water use assessment | [152] |

| SCG | Coffee industry | UK (conceptual) | Fuel ethanol from oil-free SCG | Biochemical ethanol flowsheet | SCG defatting; acid hydrolysis; neutralization and conditioning of hydrolysate | Yeast fermentation; distillation; plant sized to UK SCG supply | Conceptual industrial design | Process flowsheet with mass/energy balances; used for GHG and cost discussion (not full ISO LCA) | Extracted oil to biodiesel; solid residues as boiler fuel | No fixed FU; scenarios compared per tonne SCG | [153] |

| SCG | Coffee industry | South Africa | Biofuels from SCG (includes ethanol) | Multi-route biorefinery | Route-specific pretreatment; ethanol route uses hydrolysis to sugars and yeast fermentation | Ethanol fermentation modelled alongside pyrolysis, AD and HTL | Modelled industrial plant | Cradle-to-gate LCA for fermentation, pyrolysis, AD and HTL routes | Electricity, biogas and char as co-products; substitution/system expansion | FU 1 MJ fuel energy; GWP, acidification, eutrophication, fossil energy use | [122,154] |

| Tea waste (black tea) | Tea processing | Egypt/Turkey | Fuel ethanol from tea waste | Biochemical ethanol | H2SO4 hydrolysis of dried tea waste; optimization of acid load, time and temperature | Fermentation with S. cerevisiae or E. coli K011; ethanol ≈8–9% (v/v) | Lab | No LCA; environmental benefit discussed qualitatively as waste valorization | Residual solids proposed as animal feed or soil amendment | Not LCA; yields and basic energy considerations | [85] |

| Tea waste (green tea spent) | Tea processing | India | Fuel ethanol | Biochemical ethanol | Acid or enzymatic hydrolysis of spent green tea; optimization of fermentation temperature (~50 °C) | Batch fermentation with S. cerevisiae; max ethanol ≈33% (v/v) | Lab | No LCA; process optimization only | Residual solids suggested for composting | Not LCA; kinetic and yield data only | [155] |