Abstract

The Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development was adopted by the United Nations (UN) to guide action towards sustainable development for humanity at every scale, as “Leave no one behind” is the central, transformative promise of the agenda. The 17 global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide ambitious political targets for every UN member state to shape the future univocally. However, the sustainability challenges faced at regional and subnational levels, e.g., community levels, are substantially diverse and the strategies for achieving the SDGs also vary across communities based on their context, agency and resources. We developed a pluralistic framework to guide policy action and grass-root transformation at every scale, aligning with the global SDGs, by systematically reviewing 79 sustainability transformation projects reported in the published literature. We analyzed what these diverse scale projects had in common regarding sustainability strategies, collaborations among societal actors and how new narratives were transferred into guided action. The framework comprises five consequent phases for the implementation of SDGs and SDG targets through problem formulation to project evaluation and four enabling factors comprising context, temporality, disciplines and stakeholders that crucially facilitate the implementation of SDGs and SDG targets. Our framework pursues the “leave no scale behind” aspiration, focusing on multi-stakeholder processes and inter- and transdisciplinary methods to strengthen collaboration among a diverse set of actors, joint learning, and coherent implementation across all relevant areas of society.

1. Introduction

In 2015, 193 United Nations (UN) member states adopted the Resolution “Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” (A/RES/70/1) at the United Nations Sustainable Development Summit in New York [1]. As a plan of action, Agenda 2030 aims to steer the world into a sustainable future and to stimulate action in areas critically important for humanity and the planet over a period of 15 years [1,2]. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations are part of the Agenda 2030 and guide the way to peace and prosperity for people and the planet. Consisting of 17 overarching goals and 169 subsidiary targets, the SDGs provide an orientation for sustainability transformation for societies [1,2].

The “Leave no one behind” (LNOB) principle of Agenda 2030 outlines a crucial orientation for SDG operationalization and implementation. Article 4 of the agenda declaration emphasizes a collective journey and pledges that no one will be left behind in the process of achieving the SDGs [2]. The article recognizes the dignity of each human as fundamental and urges to ensure that goals and targets are met for all nations and peoples and also for all segments of society [1,2]. LNOB is thus the central guiding principle of the UN Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework (UNSDCF), which leads the planning and implementation of Agenda 2030 by 193 member states [2]. Free, active and meaningful participation of all stakeholders, particularly the most marginalized, are warranted by the LNOB principle and UNSDCF [2].

Contrasting to the ambition that SDGs, LNOB and the UNSDCF outline, there is no universal pathway to successfully achieve sustainability transformation where no one is “left behind”. Cultures and contexts among the UN member states greatly differ in their perceptions of the challenges and their understandings of a sustainable future shaped by a diverse multitude of institutions, ideas and values [3]. Moreover, every culture faces different challenges regarding sustainable development, demanding diverse solution approaches and implementation pathways [4]. The implementation pathways are particularly challenged as they demand coherence among several policy levels and among the societal, economic, and environmental pillars [5]. For example, 187 member states have published “Voluntary National Reviews” (VNRs) to report their progress and challenges in SDG implementation [6]. A total of 44 member states presented VNRs in 2022, whereby Togo and Uruguay, for example, presented VNRs for the fourth time, and the European Union as a supranational union with 27 member states announced a VNR in 2023 for the first time [6]. Screening these VNRs reveals significant differences in the progress regarding the SDGs and their implementation pathways across the member states [7]. In 2022, “low-income countries” (LICs), “lower-middle income countries” (LMICs) and “small island developing states” (SIDSs) in particular showed a reversal in their progress of achieving the socio-economic goals, as a result of the recent onset of multiple crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in the Ukraine [8,9]. Dependency on international trade systems, remittances and tourism left the LICs, LMICs and SIDSs especially vulnerable to those crises. However, these groups of countries showed progress in achieving SDG 12 (responsible consumption and production) and SDG 13 (climate action) despite their persisting environmental challenges [7]. “High-income countries” (HICs) embedded in strong social democracies, by contrast, proved to be more resilient towards recent crises and continued to show strong performance in socio-economic goals. The major challenges for HICs remain in SDGs related to climate and biodiversity as well as in promoting sustainability in the food sector [7].

The examination of VNRs and of Voluntary Subnational Reviews (VSRs, bottom-up subnational reports that provide comprehensive and in-depth analysis of the corresponding national environments for SDG localization) portrays a serious lack of coordination in SDG implementation progress between the national and subnational scales, e.g., regions, cities, municipalities and communities [10]. For example, the Italian VSR report outlines the strong differences in implementation success at subnational scales within the nation [11]. In Italy’s VSR 2022, SDG indicators were adopted for the municipality, provincial and regional levels to make SDG targets measurable at the subnational level [11]. This report also exhibits discrepancies among the measures taken by the regional and local governments. This lack of coordination is incurred from the diverse local circumstances and priorities, which substantially differ from regional, national and global conditions [11].

The very structure of the 2030 Agenda and its 17 SDGs and LNOB principle aims to enable local authorities to build local strategic plans that do not only hold together the holistic vision of the agenda, but also guarantee the implementation of a multi-level and multi-actor governance model [10]. For example, Agenda 2030 recognizes subsidiary decision-makers as autonomous leaders with the capacity to defend the voice of citizens before national authorities [12]. Agenda 2030 also recognizes local governments as the catalysts of change and also as best-placed to link the global goals with local communities [13]. A roadmap for localizing the SDGs is emphasized to support cities and regions to deliver on Agenda 2030; it is subdivided into five parts, namely awareness-raising, advocacy, implementation, monitoring and evaluation [14]. However, there is no framework available to date for enabling the achievement of sustainability at varying scales of society which also aligns with the ambitious global SDGs. The outlined roadmap is not a prescription for the plans and processes for the implementation of SDGs at relevant decision-making scales [12]. Moreover, existing frameworks dealing with the implementation of the SDGs have several shortfalls often with regard to either their applicability on subsidiary decision-making scales or appropriate stakeholder involvement [15,16]. There is also a lack of clear models for organizing the processes for transformations that are designed as modular building blocks for SDG achievement and for a major change in the organization of societal, political and economic activities [17]. A successful framework for translation of the achievement pathways for SDGs across scales should differ among countries, regions, municipalities and communities as they must be coherent with the history, customs and government capacity at those scales, but also should align with the global ambition of achieving the goals of Agenda 2030 [17].

Here we fill this gap and develop a universal pluralistic framework—“Leave no scale behind”, which outlines a step-by-step guide for achieving the SDGs at any decision-making scale aligning with the global ambition of Agenda 2030. A systematic literature review was conducted by consolidating published peer-reviewed literature that reported projects focusing on the local, regional and national implementation of the SDGs. Guiding questions were: (i) Which consequent steps align the SDG implementation strategies at any scale with the global ambition, while leaving enough flexibility for the advertency of local realities?; (ii) What are the enabling factors to inform and guide decision-makers in steering their respective communities towards a sustainable future while bridging the global scale of the sustainability concept with the subsidiary scales of governance?; (iii) Which factors may hinder the progress of sustainability transformation through the interaction of power, institutions and interests nested across scales? We learned from approved policy concepts and implementation strategies at various scales and communities to draw on generalized conclusions that we incorporate in our framework.

2. Methods

2.1. Literature Database

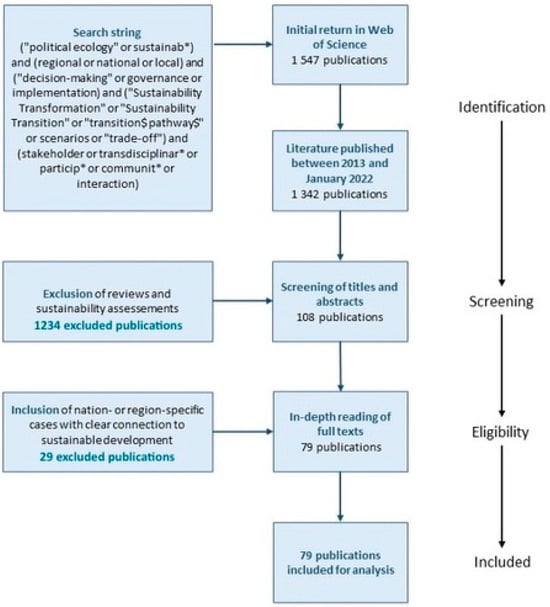

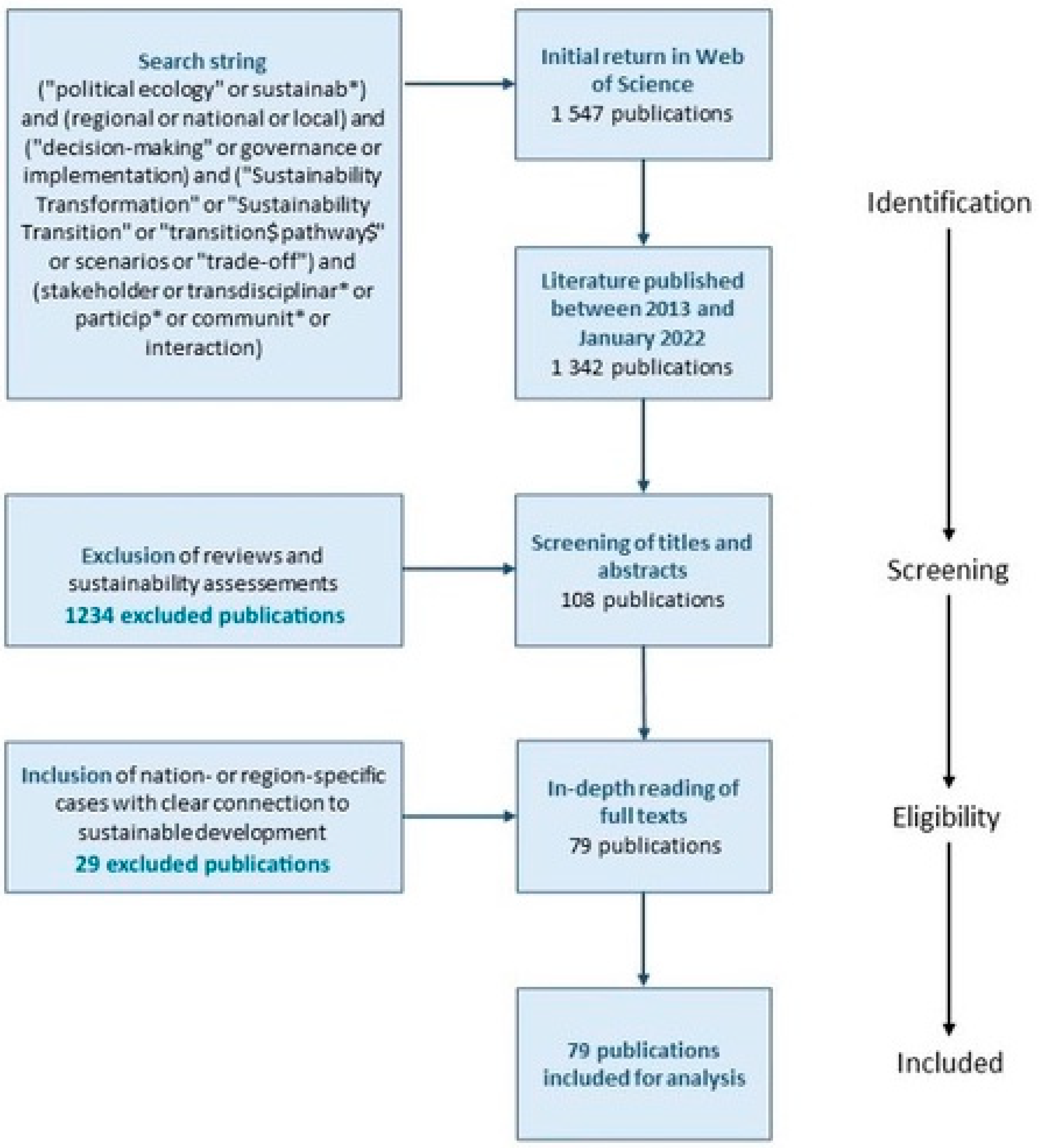

A systematic literature review was conducted applying the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis” (PRISMA) framework (for more details, see Moher et al. [18] and Figure A1 in the Appendix A). In a first step, through an iterative process, we defined a set of a priori key words and search strings to obtain a preliminary literature database. The definition of a priori key words and search strings aligned with the five parts of the roadmap for localizing SDGs—awareness-raising, advocacy, implementation, monitoring and evaluation.

The search keywords were of three groups: (1) the first group covered the overarching topic of SDGs (“political ecology” or sustainab*), (2) the second group addressed the scale of decision-making ((regional or national or local) and (“decision-making” or governance or implementation)), and (3) the final group included processes for triggering sustainability transformation (“Sustainability Transformation” or “Sustainability Transition” or “transition$ pathway$” or scenarios or “trade-off”) (Figure A1 in the Appendix A). Moreover, participation and justice aspects were also addressed in the initial search strings with the keyword set (stakeholder or transdisciplinar* or particip* or communit* or interaction) (Figure A1). These keyword sets were then combined in a final search string that was first applied in the electronic scientific literature data source “Web of Science” (webofknowledge.com) in the month of April 2022. By restricting our search to only peer-reviewed journal articles, we obtained a total of 1547 potentially relevant articles at this stage.

At the United Nations Rio + 20 summit in Brazil 2012, governments agreed to create SDGs as a refinement and follow-up to the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) [19]. In 2013, Griggs and colleagues argued for the integration of planetary stability into this new set of goals and also to integrate social, economic and environmental dimensions for providing guidance for long-term human prosperity [20]. Hence, as discussions about the 2030 Agenda and SDGs have already started among scientific communities between 2012 and 2013 despite their formal adoption in 2015, we included all articles published between January 2013 and January 2022. Defining this search time period reduced the number of articles to 1342.

At the third stage, we screened the titles and abstracts of the preliminarily identified articles based on a set of inclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria were two-fold: (1) the article presents a nation, region, community or any scale-specific case and (2) there is a clear connection to sustainable development and the SDGs. After the first round of screening, a selection of 108 articles was made for further in-depth examination. During in-depth reading, another 29 articles about sustainability assessment were excluded as these were rather focused and restricted to the analysis of the present condition without aiming for long-term sustainability transformation. Finally, a set of 79 articles was selected for the in-depth analysis and construction of the framework (see Table A1 in the Appendix A).

2.2. Framework Construction

We subsequently constructed a framework comprising three core elements: (1) Phases to guide step-by-step implementation of SDGs and SDG targets at any scale, (2) Enabling factors to support and facilitate the implementation of SDGs and SDG targets, and (3) Hindering factors that may hamper and slow the progress towards sustainability transformation. We first analyzed the methods parts of the articles in our final literature database in-depth to construct the phases (Table A1). The individual methodological steps followed by the authors of the reviewed articles were then clustered and aggregated to represent the phases applied in all articles for targeted sustainability transformation (an overview of the literature database is available in the Appendix A). The clustering and aggregation reduced the complexity of the methodological approaches followed by the researchers in the articles and enabled a homogenization of the phases in the framework by retracing the diverse applied methods. Finally, we arrived at five phases that represent the step-by-step methods, procedures and strategies applied by the research projects reported by the articles for SDG and target implementation at diverse scales (Figure 1). Note that the succession of these clustered methods does not imply that these methods were necessarily carried out in this order by the authors of the reviewed articles. Also, our framework does not prioritize the phases based on the frequency of articles applying a specific method or aggregated phase. We regard all phases and methodological steps as equally crucial for successful implementation of the SDGs and SDG targets.

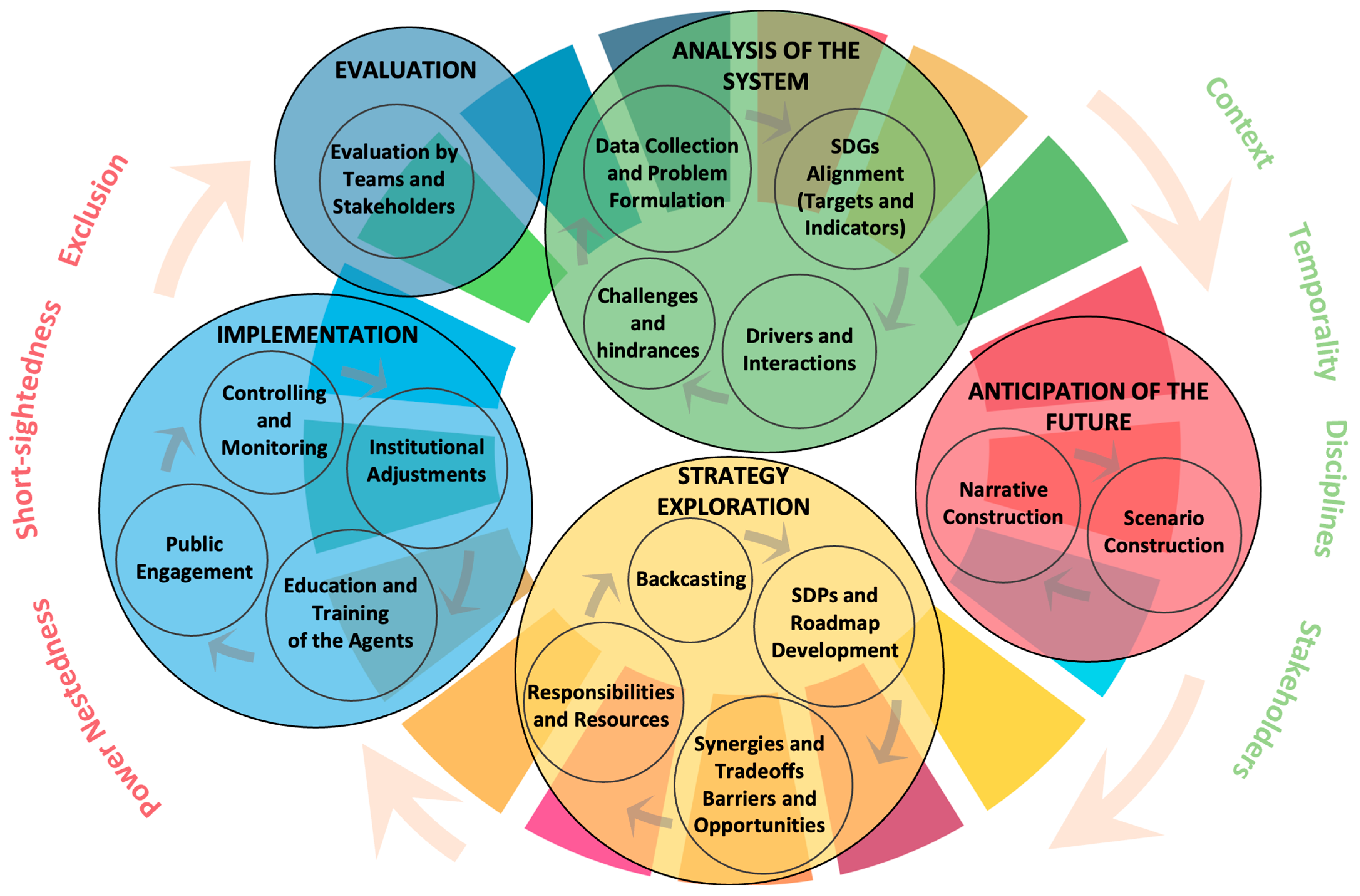

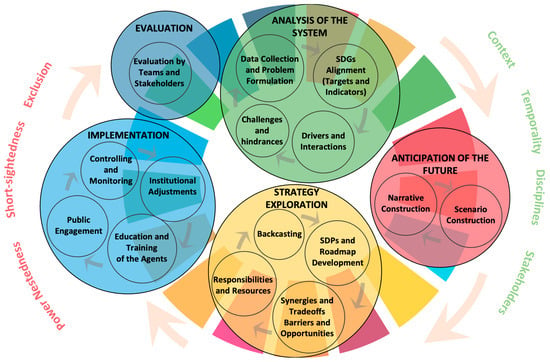

Figure 1.

The “Leave no scale behind” framework comprising: (1) Five consequent phases for the implementation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and SDG targets at any scale, which are represented by the circles (big circles represent the major clustered phases while the small circles within the big circles represent the sub-phases constituting the major phases). The direction of arrows indicates the direction of phases conduction; (2) Four enabling factors supporting and facilitating the implementation of SDGs and SDG targets, represented by the green text on the right; (3) Three hindering factors challenging the implementation of SDGs and SDG targets, represented by the red text on the left.

In the next step, we analyzed the results and discussion parts of the articles to identify and evaluate the enabling and hindering factors that supported and facilitated the applied methods in leading to the desired outcome of sustainability transformation (see Appendix A). This also led to the identification of factors that may potentially hinder the progress of sustainability transformation projects. This process was conducted in four subsequent steps: (1) First, the fields of interest in the form of the SDGs covered by the articles were identified. In case allocation to specific SDGs was not done by the authors, we established connection to the specific SDGs by assessing the sustainability aspects that were explicitly addressed by the articles. Delicate interactions and interconnectedness across SDGs were ignored at this stage as we regarded holistic sustainability transformation regarding all SDGs as equally important. If the articles only addressed SDGs holistically that was also identified. (2) Second, we identified the spatial/geographic and temporal extent covered by the articles. The information about the spatial/geographic extent and also the country and continent the articles represent was then combined with the SDGs of interest to identify the context at a particular scale. The temporal extent covered by the articles indicated the temporality of the projects both in terms of the goal (year) for achieving SDGs and also whether they were short- or long-term projects. (3) Third, the disciplines of the authors and research and also knowledge and expertise available at the scale that were involved during the planning and realization of the research projects were identified to formulate the discipline base. (4) Finally, we analyzed the participatory aspects and involved stakeholders particularly in the project planning and decision-making phases. Potential conflicts of interests among the stakeholders and institutions were also identified. We regard the participatory aspects and processes as central to our framework leading to cross-scale collaboration for achieving the SDGs.

3. The “Leave No Scale Behind” Framework

The “Leave no scale behind” framework (Figure 1) comprises three core components: (1) Five consequent phases for the implementation of SDGs and SDG targets through problem formulation to project evaluation, (2) Four enabling factors comprising context, temporality, disciplines and stakeholders that crucially facilitate the implementation of SDGs and SDG targets, and (3) Three hindering factors comprising power nestedness, short-sightedness and exclusion that may impede the implementation of SDGs and SDG targets at variable spatial scales. Several constituting findings from the literature review shaped the clustering and aggregation of the phases, enabling factors and hindering factors in the framework (see below for details).

3.1. Phases

3.1.1. Analysis of the Social-Ecological System

Our consolidation of studies suggests that SDGs and SDG targets implementation at any scale starts with an analysis of the targeted socio-ecological system since a thorough understanding of the system in question was recognized as a prerequisite for formulating SDGs and targets [21]. Most researchers and decision makers first made themselves familiar with the local circumstances by collecting data. Data collection took diverse forms. Reviewing the scientific literature and/or policy documents and/or analyzing geographical, meteorological information and/or other scientific data were the most frequently used methods for data collection (40 articles out of 79 (51%)), followed by stakeholder and expert consultation (38 articles (48%)). Consultation also involved speaking to local agents and/or citizens to get individual viewpoints and to understand values, beliefs and concerns of local communities [22]. Engaging stakeholders already in the data collection step helped to evaluate the relevance of the projects and to build up networks. Place-based research, where the study region was visited, was done in 11 articles (14%) to get a picture of local realities and to generate scientific data needed for a more thorough system understanding.

Data collection and subsequent analysis of the collected data led to problem formulation and prioritization (evident in 16 articles (20%)). The problem formulation step was critical for the process of SDGs and SDG target implementation as this allowed for refining and adjusting the overall aims and goals for the projects. This involved framing the needs and urgencies for sustainability transformation [23]. In this sub-phase, system boundaries and the scope of the projects were also clearly defined. Problems were formulated inductively in four studies by including stakeholders. For example, José Luis Camarena and his team started their stakeholder process by letting participants give their opinions about various predefined topics. The collected primary and secondary data gathered from the workshops helped to complement and validate a problem tree [24].

Once the problem is clearly formulated and priority areas are identified, our consolidated literature identified the global SDGs relevant for the projects including the selection of associated targets and indicators. A total of 13 articles explicitly identified specific SDGs or even subsidiary SDG targets the project teams aimed to address. Interactions in the form of co-benefits and tradeoffs between the aligned SDGs and targets, and remaining SDGs, were mapped out in seven articles. A total of 13 articles (16%) included a step for mapping the interactions with overarching SDGs related to gender discrimination (SDG5) and inequalities (SDG10) through a network analysis. The central questions for mapping these interactions were: (1) Who is exposed or affected? (2) Who is especially vulnerable to it? (3) Who benefits? (4) Who has the ability to change the system? (5) What are the power relations in the network? Vulnerable groups of people with little power to influence were then prioritized in the processes.

Socio-ecological systems are not static but dynamic and are exposed to constant changes [21]. Following the SDG alignment sub-phase, 29 articles (37%) identified drivers of change to understand the dynamics of the systems in question. In the “Millennium Ecosystem Assessment” (MA), a “driver” is defined as any factor that changes any aspect of a system and unequivocally influences processes. An indirect driver operates more diffusely, often altering one or more direct drivers [25]. The identification of drivers apprehends which factors, developments and events led to the present state of the system and which of these drivers have the potential to influence the system in the future. In many of the cases, drivers’ identification and prioritization were led or assisted by involved stakeholders. This enabled the stakeholders to understand the complexity of the systems and to reflect about processes and emerging patterns. Real-world systems have a high complexity which makes it almost impossible to cover all drivers. Consequently, key drivers were selected and driving forces were ranked in eleven projects. Eleven articles further analyzed the impacts of drivers over time.

In a final sub-phase, the consolidated studies identified uncertainties and challenges that may possibly hinder the success of SDGs and SDG target implementation. In ten articles, the main challenges were identified, whereas in five articles uncertainties were defined for sorting out contingency plans for the planned projects.

The four sub-phases constituted the local realities of the projects and delivered an in-depth understanding of the social-ecological systems. The realities were visualized either through problem trees or causal loop diagrams. Three studies, e.g., Mangnus et al. [26], chose a descriptive approach for articulating the problem and outlining the system features.

3.1.2. Anticipation of the Future

Our review results suggest that projects aiming to initiate sustainability transformations need to explore potential future developments of the study region in the second phase to be able to actively shape them (Figure 1). In our consolidated literature, examination of possible and aspired futures was either done through scenario construction and assessment (sub-phase 1) or through the creation of future narratives like visions and utopias (sub-phase 2). This phase was conducted in close collaboration with stakeholders as this involved visions for a common future, shared between stakeholders, and provided the basis for joint action.

In more than half of the articles (46 articles), scenario construction was conducted to map out different optional futures. This was done by exploring the possible development of the previously defined key drivers and their interactions in the future. Thereby, the assumed development of relevant drivers and variables and their interactions were merged into local future scenarios. In this sub-phase, many projects used participatory approaches to define relevant and desirable futures, which were conceived by local stakeholders. Some projects utilized predefined scenarios like climate change projections, regional development scenarios, policy scenarios or socio-economic change developments, which were often formulated for a larger scale and needed to be downscaled to the regional or local level of a project. For example, Nilsson et al. [27] and Kamei et al. [28] used a set of predefined “Shared Socioeconomic Pathways” (SSPs) as boundary conditions and extended them by incorporating locally relevant drivers of change leading to the development of local SSPs. Formulated by the “Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change” (IPCC) the SSPs explore socio-economic developments and their impact on climate change projections and are one prominent example of predefined scenarios described on the global scale (see IPCC [29]). A “business as usual” (BAU) scenario helps to demonstrate what the future will look like if no interventions are made and thus might enhance motivation to take action. Predefined scenarios furthermore helped the project teams to explore trends on subordinated scales influencing the regional or local level and provided orientation for downscaling to a relevant decision-level.

The scenario construction process was followed by a scenario assessment, evaluating where potential leverage points lie and if the previously set goals could be reached. Future projections were assessed by 29 articles (37%). Different assessment methods were available, such as construction of indicators (done by eleven articles), key driver interactions (done by eleven articles) and identification of potential leverage points (done by one article). After the assessment, one or several (desirable) futures were constructed for further evaluation and strategy development.

Narrative construction was also a frequently used (21 out of 79 articles) sub-phase, where future visons or utopias were created to obtain a vivid representation of the future. This sub-phase was either executed singularly substituting a scenario construction process or sometimes additionally to the scenario construction process. In some cases, the constructed narrative was the result of a scenario assessment where the most desired or likely future was kept for further investigation. A narrative was sometimes the outcome of a scenario construction process, where stakeholders agreed on a shared vision of the future. Seven research projects incorporated key drivers into the narratives. In nearly all of the 21 articles, narratives were described by the stakeholders that were part of the participatory processes. In some articles, the final narratives were constructed by the researchers involved using and merging participating stakeholders’ visions.

In 18 articles (23%), scenario and narrative construction led to the completion of the projects by summarizing the outcomes of their foresight processes. The results were aimed to support “evidence-based policy-making” [30]. Thus, the stakeholders and decision-makers were left to draw conclusions on their own and transform their theoretical knowledge into action.

3.1.3. Strategy Exploration

A majority of the projects (73%) that constituted our consolidated literature continued to a third phase of strategizing and developing plans about how to reach targeted futures that were developed and assessed in the second phase (Figure 1). This phase comprised four sub-phases starting with backcasting and ending with the allocation of responsibilities and resources for making the developed futures tangible through strategizing and planning.

The first sub-phase, i.e., backcasting, is a process of first imagining that a desirable (sustainable) future vision or normative scenario is accomplished and then looking back at intermediate goals, milestones and pathways that could make the achievement of the desirable future possible. This involves defining and planning activities, setting milestones, and developing strategies that could potentially lead the project towards that desirable future [31]. Most of our reviewed literature carried out this step where strategies to reach future visions were explored and the transdisciplinary teams explored actions and strategies for achieving the future vision (see Table A1 in the Appendix A). However, only ten articles (13%) referred to their applied methodology as “backcasting”. All of these ten projects used a participatory backcasting approach with the relevant stakeholders. A total of 32 (41%) of the reviewed articles proposed explicit measures, policies, actions or strategies for achieving the future. Eight articles set subsidiary targets for shorter future timescales, defining short-, medium- and long-term strategies and short-term priorities. Participants in the research project by Bhave et al. [32], for example, were asked to “sequence the adaptation options based on their priorities in 5-year intervals” [32]. Intermediate goals were also set in the project by Pereverza et al. [33], where the deadline for reaching the overarching goals was 2050 while setting deadlines for specific actions in 2030. Short-term planning of actions facilitated an early implementation of short-term goals and enabled transformations that may already benefit the involved stakeholders in their lifetimes.

A total of 19 articles (24%) did not name their strategic planning phase as “backcasting” but developed “Sustainable Development Pathways” (SDPs) or roadmaps to reach specific scenarios. This involved a second sub-phase of strategy exploration because projects that developed SDPs already defined subsidiary targets and follow-up strategies and thereby bridged the gap among the present state of the system, subsidiary targets and the desired future. SDPs and roadmaps also illustrated how the aspired sustainable development could evolve and unfold. For example, Vachon et al. used stakeholder preferences to develop interconnected scenarios and to combine these into one “alternative masterplan” [34].

Once actions and possible pathways to reach a desired future were defined, many reviewed projects progressed into a third sub-phase evaluating their strategies applying qualitative and quantitative assessment criteria to identify potential synergies and trade-offs between measures and barriers and opportunities in the SDPs. Consideration of synergies and trade-offs between measures and exploration of barriers and opportunities enabled the project teams to foresee and prepare for potential obstacles arising during the project implementation. In eleven reviewed projects (16%), synergies and trade-offs between measures were evaluated and in 20 projects (30%) barriers and opportunities or potential leverage points were explored. Randers et al. [35] warns that there is an apparent conflict between the three environmental goals (SDGs 13, 14 and 15) and the 14 socio-economic goals. Hence, striving to achieve the socio-economic goals with conventional efforts could reduce the Earth system safe margin represented by the nine planetary boundaries [35,36].

In a final sub-phase, eleven articles (16%) concluded their strategy planning process by defining responsibilities, mapping actors, allocating resources and setting contingency plans. Assigning actors and their responsibilities made the realization of specific measures seamless and induced shared and common responsibilities. Budgeting and allocation of resources were crucial for making the achievement of the goals plausible. Setting the contingency plans outlined what should be done if responsible actors missed the deadlines for achieving the subsidiary targets. This, in turn, prevented the risk of diverting from the intermediate goals due to unforeseen political and economic changes.

3.1.4. Implementation

Conventionally, research and planning projects concerning sustainability transformation regard the implementation phase as out of their scope. We observed a similar trend in our consolidated literature as a majority (42 articles, 53%) of our consolidated articles that primarily represented research and planning projects ended and summarized outcomes in the strategy exploration phase without any implementation plan. For example, Odii et al. [37] justified the project team’s decision not to conduct an implementation of the project outcomes as the results being of general interest to the local community and not to be used for real decision-making. The scenario proposals were also made for the distant future [37]. In addition, since the study site was rural and in a developing country, the education and competence level of the participants were regarded as not suitable for informing policy and decision-makers [37].

Nevertheless, 37 (47%) out of 79 reviewed articles included an implementation phase where strategies and plans agreed upon in the previous phases are put into practice (Figure A1 in the Appendix A). These projects regarded the implementation phase as a crucial step for transferring theoretical project outcomes into actions for real-world implications. This phase was also indicated as a measurement of projects’ contribution to the realization of the Agenda 2030 [38]. Thus, a successful accomplishment of this phase indicated a long-term value of the projects for initiating sustainability transformation [38].

Several implementation sub-phases were conceived in those projects, which were delegated to the societal actors assigned with the implementation and to the involved relevant stakeholders. Out of the 37 articles that outlined an implementation phase, 32 articles summarized project outcomes with the intention to inform policy and decision-makers for institutional reform and adjustments (sub-phase 1). In some cases, reports were written in which policy recommendations and management suggestions for new institutions were given. For example, Hensler et al. [39] suggested forms of organizations and new institutional settings for appointing commissions to analyze and act upon main strategic subjects. A total of 14 projects focused on the education and training of the local agents that were entrusted with the implementation of defined strategies (sub-phase 2). A total of 12 of these projects enhanced knowledge-sharing between stakeholders either already during their participatory processes or at the end to ensure the seamless continuation of the efforts. For example, Coleman et al. [40] launched an online forum for discussion and sharing sources among stakeholders. Engagement with the broader public, which was not a part of the participatory processes, was facilitated by eleven projects as a third sub-phase. For example, in the project conducted by Gonçalves et al. [41], 11 dissemination sessions were held for the local community to raise awareness and to generate behavioral changes, as well as to strengthen public involvement and participation in the future implementation of the plan [41]. While training institutional and economic agents, this project furthermore suggested the creation of a “Commission for Climate Change Monitoring and Adaptation” formed by three main sectoral groups to manage and continuously monitor the adaptation actions [41]. In four projects, controlling and monitoring mechanisms were put into place to control the success of the implementation process as a final sub-phase. Controlling and monitoring were enabled through new institutional settings to evaluate and review the actions of actors responsible for achieving the desired future. For example, Pereverza and her team [33] and Ferguson et al. [42] controlled and monitored further actions by actively taking part in the implementation process. A subset of the research team was part of the scientific network entrusted with implementation actions and follow-up activities.

3.1.5. Project Evaluation

The process of sustainable development and sustainability transformation in our consolidated literature ended with a project evaluation phase (Figure 1). In this phase, the performance of the procedures and methods applied to achieve the set goals are reviewed along with the rate of accomplishment of project goals. Moreover, the actors, i.e., researchers, decision makers and community stakeholders, reflect upon their roles in the project and also on their biases that may confound the results.

In our reviewed literature, evaluation was either carried out by researchers themselves or with consultation of stakeholders who participated in the project. In 12 (15%) out of our 79 reviewed articles, researchers themselves assessed the project outcomes and reflected on the methodology used. The evaluation involved the assessment of the suitability of the applied methods and methodological steps, and identification of the needs for adjustments. Moreover, the suitability of the design of the participatory processes to encourage stakeholder engagement, joint learning and problem ownership, was also assessed. Furthermore, the inclusivity of the projects to make sure that no one has been “left behind” was also evaluated.

In another 12 (15%) projects, relevant stakeholders and participants were involved in the evaluation phase, either by giving them the chance to give their feedback in person at the end of the participatory process or by sending them a feedback-sheet to fill out. Two projects (Hensler et al. [39] and White et al. [43]) adopted a post-evaluation strategy as they regarded the identification of societal impacts in their transdisciplinary research as difficult immediately at the end of the project. They conducted a comprehensive ex-post evaluation 3 years after the projects ended [43]. This gave the project teams the possibility to reflect upon the practices and readjusted plans [39]. Moreover, the ex-post evaluation was crucial for evaluating if the projects succeeded to initiate real-world transformation. For research projects, the project evaluation phase did not only contribute to the learning of the research team in question but also informed the broader scientific community engaged in sustainable development research.

3.2. Enabling Factors

3.2.1. Context

We identified contextualization as the first enabling factor in our consolidated literature for supporting and facilitating the implementation of SDGs and SDG targets at any scale. Contextualization manifests through two stages: (i) Projects’ alignment with relevant global SDGs and Agenda 2030 and (ii) Alignment with the geographic characteristics and priorities, where the projects are conducted.

Alignment with the global SDGs and Agenda 2030 is crucial at the first system analysis phase, since these global goals provide orientation and sometimes guidance for actors implementing projects. For every SDG, there are several targets and indicators (see UN Statistical Commission [44]). The Inter-Agency and Expert Group on SDG Indicators (IAEG-SDGs), established by the UN Statistical Commission, has developed a global indicator framework for the SDGs, which aids stakeholders in planning, conducting, and assessing projects by providing standardized indicators and methodologies see [45,46]. Moreover, the alignment provides the opportunity of extracting evidence-based information about the SDGs and SDG interactions from previously conducted projects. For example, the “International Council for Science” (ICSU) conducted an analysis on the interactions among the global SDGs and published guidelines targeting policy-makers, practitioners and scientists working at the global, regional, national and local levels on implementing or supporting the implementation of the SDGs [47]. Through a framework, they provide the guidance for understanding interlinkages between SDGs and subsidiary targets and enhance simultaneous implementation of several SDGs, making synergies and trade-offs obvious. Comprehending such interactions may help actors to uncover the projects’ unforeseen environmental, economic and social impacts.

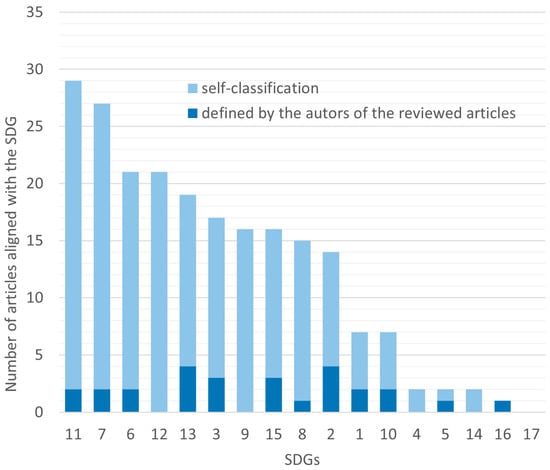

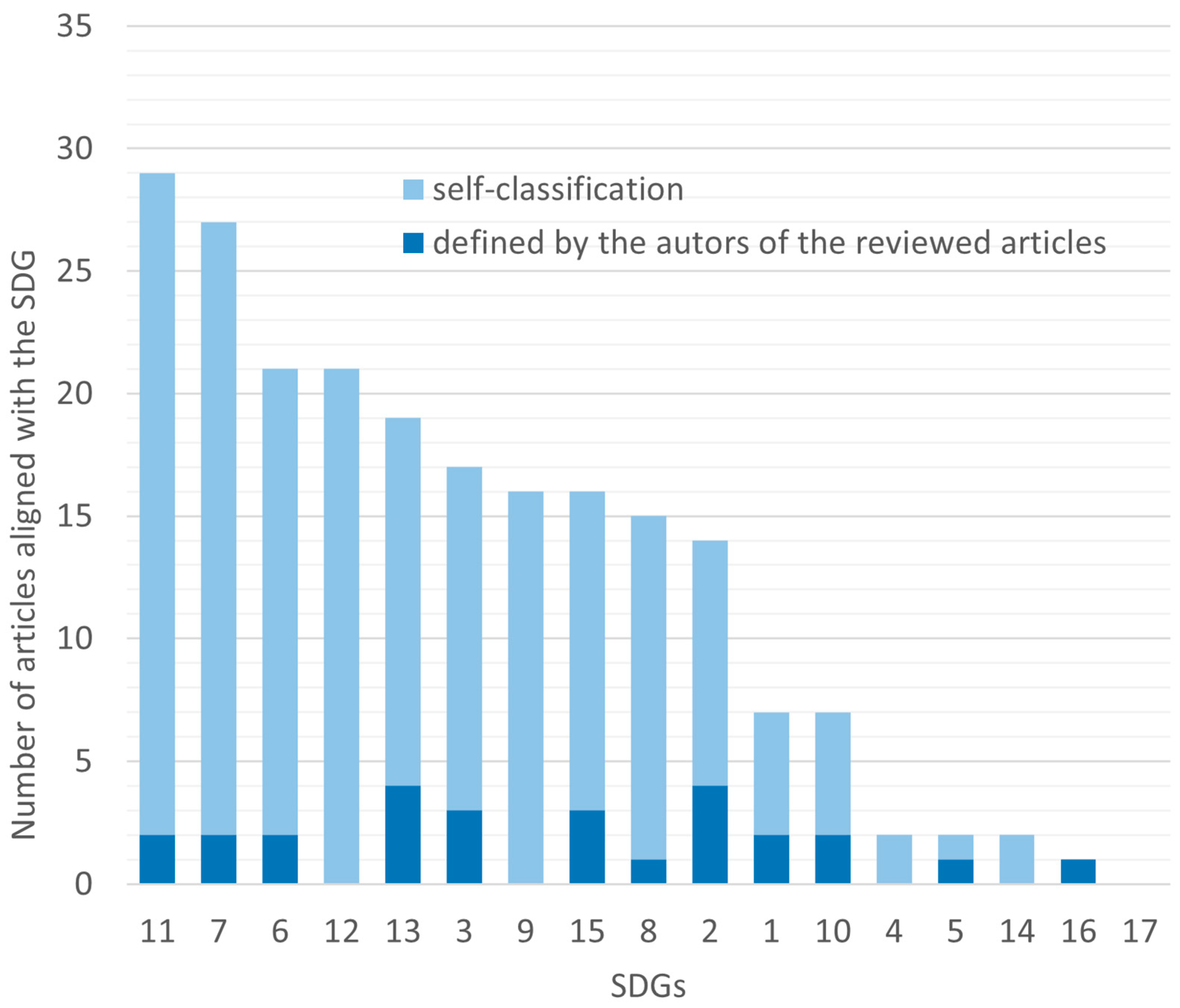

All of our reviewed projects strived to initiate sustainability transformation in their respective scales and fields of interest, contributing to the achievement of global sustainable development and the realization of the Agenda 2030 (Figure A2 in the Appendix A). However, only 21 articles directly referred to the Agenda 2030 and the integrated SDGs. A total of 15 (19%) out of the 79 reviewed articles were published before the Agenda 2030 was adopted in September 2015 and therefore could not refer to it (see Table A1 in Appendix A). SDG 11 (sustainable cities and communities), SDG 7 (affordable and clean energy), SDG 6 (clean water and sanitation) and SDG 12 (responsible consumption and production) were included in more than a quarter of the articles (Figure A2). Hence, a majority of the projects focused on the creation of sustainable urban environments, a resilient use of resources and an economy which meets the demands of a sustainable future. These were followed by SDG 13 (climate action), SDG 3 (good health and well-being), SDG 9 (industry, innovation and infrastructure) and SDG 15 (life on land) (Figure A2). Certain SDGs, such as, SDG 4 (quality education), SDG 5 (gender equality), and SDG 14 (life below water) were only directly addressed by two articles. However, these societal SDGs were often regarded as overarching perspectives. SDG 16 (peace, justice and strong institutions) and SDG 17 (partnerships for the goals) were hardly considered as a priority (for more detailed information see Figure A2). Since these are rather (geo)political process-related goals, they were indirectly considered in most reviewed projects in the form that project implementation is enhanced by policy procedures that include principles of good governance and stakeholder participation, leading to joint action within and beyond local communities [47]. A total of 12 articles (15%) addressed sustainable development as an overarching guidance rather than focusing on specific areas or SDGs.

Concretizing the region of study and aligning with the characteristics and priorities within the boundaries of the study regions were regarded as vital for the project planning phase in our consolidated projects. The culture, system of governance and availability of skills and resources should guide the scope and boundaries of the projects concerning sustainability transformation [48].

A majority of our projects operated on the local (47 projects, 59%) and regional (38 projects, 48%, some incorporated insights from a specific city or municipality of their regions) scale (Figure A3 in the Appendix A). Local projects focused on cities, municipalities, or single communities while regional projects spanned political regions, like districts, provinces and federal states, or geographical regions, like natural protection areas, coastlines or river basins. Ten projects addressed sustainability transformation at a national scale and only few articles envisaged transboundary regions like the Iberian Peninsula [49], the Barents Region [27] or North Africa [50] (see Table A1 in the Appendix A). The reason why a majority of projects focused on the local scale is likely that the contextualization to geographic characteristics and priorities is most effective at local scales, since project teams can most holistically comprehend local challenges and delineate local resources, competences and skills to act upon them [51].

Our analysis of the geographical distribution of the reviewed projects entailed a Europe centric pattern (Figure A3). Such sustainability transformation projects were rare in Central Asia, Russia, and the central part of Northern America (Figure A3). This pattern may be associated with the global distribution of research institutions [52]. Bornmann et al. [52] observed a similar pattern when they spatially visualized countrywide scientific institutions and their performance through a web application (the application can be found here https://www.excellencemapping.net/ (accessed on 15 April 2025)). This indicates that such sustainability transformation projects are often conceived by research institutions for nearby regions. However, other factors such as population density, economic resources available for research, urgency for climate change adaptations, cultural norms, religious beliefs, and openness of local non-scientific and political institutions may also influence the spatial pattern of project regions [53].

3.2.2. Temporality

We identified temporality as the second enabling factor, particularly at the future anticipation phase since at this stage the timeframe of projects goals and objectives, whether short-, medium- or long-term, are set. The temporalities of projects drastically impact the strategies and final agreements among the stakeholders [27,41]. Projects’ temporal scales might also require final adjustments while the pathways and strategies are developed [27,41] since projects teams should evaluate whether the targeted futures are tangible. Project participants’ motivation to take action and capacities to address uncertainties are also shaped by the timeframes set in projects.

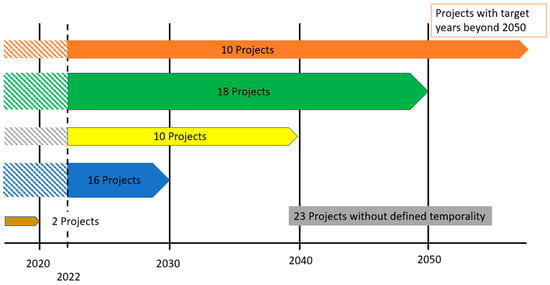

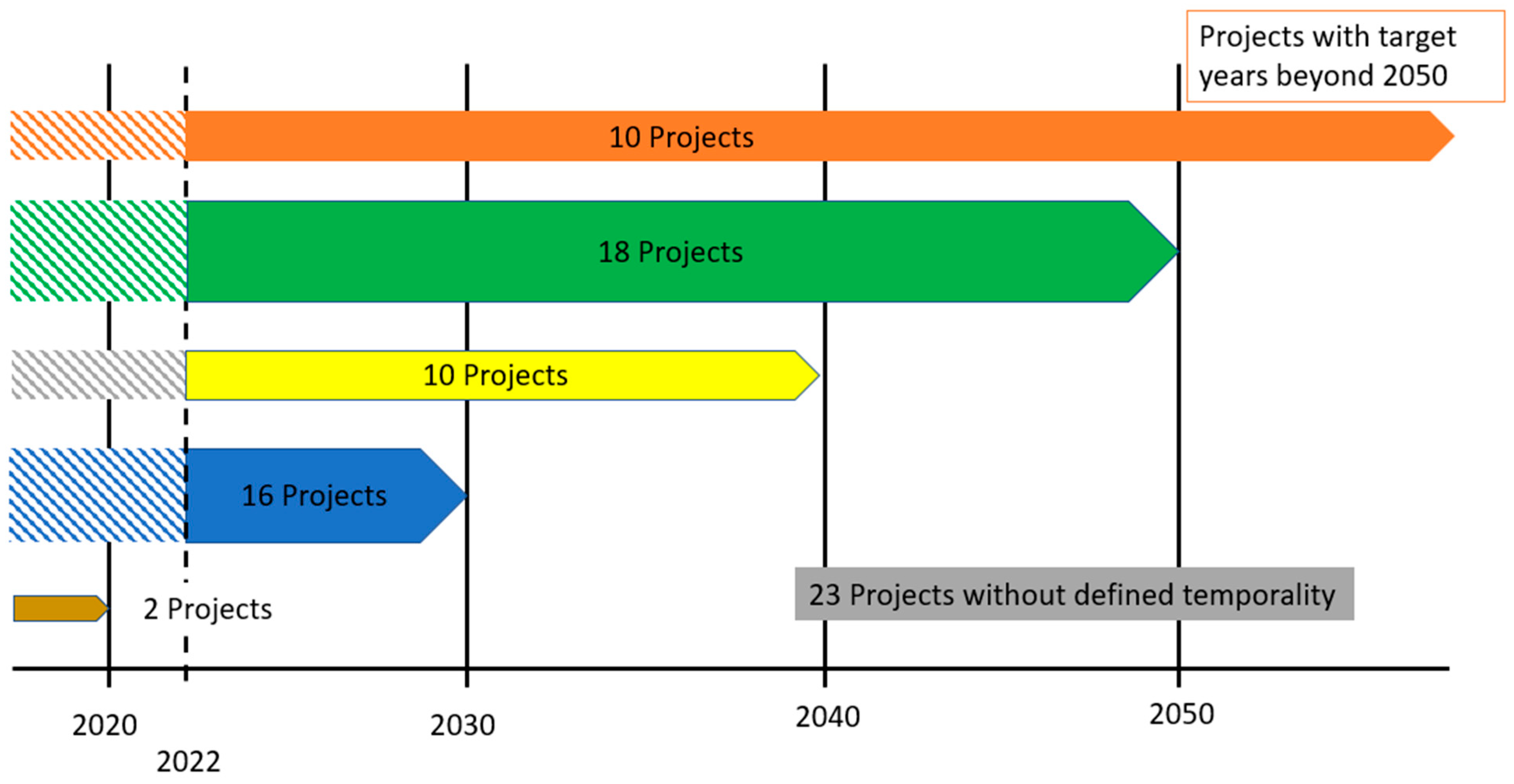

In our reviewed literature, the defined future and the timescale of scenarios and visions ranged from near futures spanning only a couple of years to more distant futures embracing decades (up to 100 years) (Figure A4). A total of 56 (71%) articles explicitly set their temporal scales either by determining a specific year or a time span in years for accomplishing the project goals (Figure A4). A total of 16 (20%) out of these 56 articles set 2030 as a target year, aligning with Agenda 2030. A total of 18 articles set 2050 as the target year aligning with the Paris Agreement. Thus, 2030 and 2050 were regarded as politically relevant target years for sustainable development projects as national and regional agendas often formulate policy goals and objectives for these years. Setting the target years to 2030 and 2050 enables research projects to evaluate their results against the preexisting indicators formulated by political and government institutions. Moreover, this enables research projects to effectively contribute to the fulfillment of the politically set regional, national and global goals [54].

The target years for the accomplishment of the goals in 10 (13%) projects went beyond 2050 (Figure A4). Although long-term visions are important, this often makes the future appear distant and might hinder the willingness of stakeholders to take actions in the present as they hurdle to see benefit from improvements [41]. Moreover, the uncertainties in the long-term projects are high regarding the identification of relevant variables and drivers and also monitoring the project accomplishment [41].

A total of 23 (29%) articles did not define or vaguely defined a temporal timeframe in which future anticipations and strategies should be designed (Figure A4). For example, Nilsson et al. [27] developed their time frame in the vague perspective of one or two generations. Thus, it is crucial that sustainability transformation projects at local and sub-national scales carefully evaluate politically defined time horizons against their own requirements and context fitness. Intermediate targets may enable bridging the path between the present systems and anticipated futures.

3.2.3. Disciplines

Disciplines—backgrounds and knowledge not only on diverse scientific disciplines but also on diverse contexts and social-ecological systems that sustainability transformation projects concern—constitute our third enabling factor identified in this literature review. Background and knowledge of the people involved in project teams who plan and conduct the transformation projects and also actively author scientific articles and project reports thereby directly shape project goals and methods [55].

In the reviewed articles, people directly involved in the preparation and realization of the research projects came from diverse backgrounds and represented multiple knowledge forms (see Table A1 in the Appendix A). In most cases, scientists of acknowledged disciplines took the lead. Their backgrounds included largely the field of natural sciences, but also engineering and technology, and the social and political sciences. Many research teams consisted of scientists belonging to diverse disciplines, thereby forming interdisciplinary and in many cases also international teams as the projects demanded. Interdisciplinary teams with diverse scientific backgrounds do not only comprise a wide array of knowledge and skill sets, but also a diverse set of methods and procedures [56].

Sustainability transformation projects may require pushing the boundaries of interdisciplinarity and becoming transdisciplinary by involving local experts and institutions like local government bodies in the core planning process. In our consolidated literature, 14 (18%) projects included practitioners and experts outside academia, such as representatives from local governmental institutions and local non-governmental organizations, into project planning. The aim was to enhance projects through the inclusion of local field level perspectives and uncover practical aspects that were not detectable by scientific research and literature searches [57]. Moreover, this ensured seamless communications between local actors and scientists to validate the research aims, suggested methods and outputs [58].

A majority of our consolidated projects included researchers either native or affiliated to a research institution based in the region under investigation. However, in 11 (14%) projects, none of the researchers were affiliated to a research institution placed in the project regions. Nevertheless, two of those projects included non-academic local experts and practitioners in the project team for planning and executing the projects. Five of the remaining nine projects were conducted in a country belonging to the Global South. Exclusion of the local experts in scientific projects conducted in the Global South is criticized as “neo-colonial science” [59]. Farid Dahdouh-Guebas et al. [59] investigated “neo-colonial science” through a review of 2798 scientific projects conducted in 48 countries placed in the Global South. Their results show that 70% of the projects in the Global South were conducted by scientists and experts from the industrialized nations in the Global North excluding experts from the local research institutions. Since we identify context and disciplines as two crucial enabling factors for sustainability transformation projects, we stress the importance of engaging and cooperating with local and native scientists and institutions.

3.2.4. Stakeholders

The final enabling factor that was identified through our literature review is the relevant stakeholders. The “Leave no one behind” principle encourages participatory and co-created research approaches. To ensure effective, just, inclusive and transparent sustainability transformation, it is crucial not only to identify and include particularly vulnerable groups of society but also outline and construct mechanisms for stakeholder involvement as a part of project execution [60]. The identification may be performed by using the recommendations by international human rights mechanisms for identifying the ones who “have been left behind” [61]. The mechanisms, on the other hand, should include a platform for the stakeholders to express their concerns, ideas and desires. Early and conscious identification helps to adjust methods and research aims so that they are suited to empower vulnerable groups [61]. Many of our consolidated projects thus advocate for participatory bottom-up processes where stakeholders can take the future into their own hands, while being supported and empowered by the research teams [62].

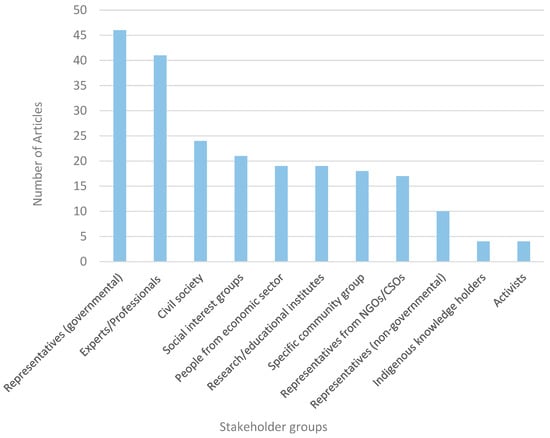

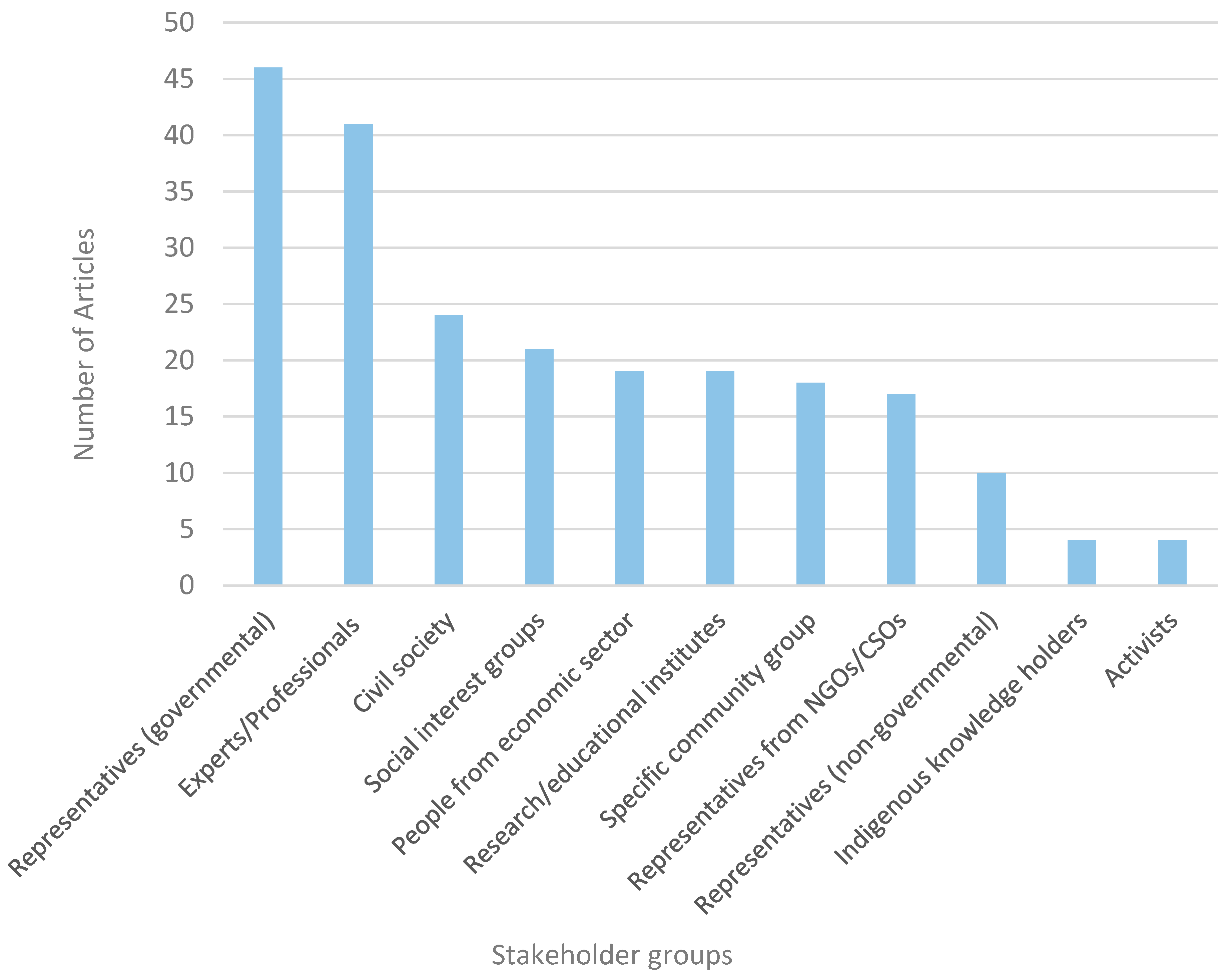

A majority of the reviewed articles (63 articles, 80%) executed a participatory process with local and regional stakeholders (Figure A5 in the Appendix A). The part of society invited to participate was highly dependent on the aim of the research project, but they comprised members of civil society, experts in the field, and officials in the local government and politicians (see Figure A5 in the Appendix A). About 60% of the projects (48 out of 79) included stakeholders belonging to civil society (Figure A5). In 24 (30%) projects, community members and citizens identified through different sampling methods were invited to take part in the participatory processes. Community members of specific demographic groups like women, children and students were selected by 18 (23%) research teams, who were interested in the perceptions and needs of particular civil stakeholders. A total of 10 (13%) articles summoned non-governmental community representatives, while 17 (22%) research teams asked representatives from non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and civil society organizations (CSOs) to join the participatory process (Figure A5). A total of 21 (27%) articles referred to the representatives of social movements and interest groups, but participation of activists (four projects, 5%) and indigenous knowledge holders (four projects, 5%) was rare (Figure A5).

A total of 46 (58%) projects involved regional or local decision-makers comprising officials of local or regional governments, elected representatives from governmental bodies, local councilors, mayors, and public and civil servants (Figure A5). Experts and professionals, who possessed theoretical and practical knowledge of the local environment and in the specific project fields, were summoned and consulted by 41 (52%) research teams. In 19 (24%) research projects, members of external research and educational institutions were asked to bring their knowledge into the research process, for example as technical advisors. Another 19 (24%) projects included people from the economic sector, including representatives from private businesses, industries and entrepreneurs (Figure A5).

3.3. Hindering Factors

3.3.1. Power Nestedness

Although our framework aims at scale-independent sustainability transformation, we believe that political and decision-making power is always nested across scales [63]. Sustainability transformation projects address complex issues and their successes are inherently embedded and dependent on the decisions and strategies adopted across multiple scales [63,64]. The complex interplay of diverse institutions and power vested at multiple scales and its complex nestedness may hinder projects aiming at sustainability transformation at a specific scale [63,64]. For example, decisions and strategies adopted at regional and national levels can have unforeseen and significant adverse impacts on and even contradict sub-national scale projects [65]. This is often evident by decarbonization schemes and projects undertaken at sub-national and city scales that are hindered by the conflicts of interests with fossil-fuel lobby at national and regional scales [65]. Likewise, national decarbonization strategies may adversely affect local coal mining industries, potentially leading to backlash against sustainability initiatives on the ground [66]. Political shifts in national and regional governments may drastically and abruptly affect initiated subnational projects as the newly elected politicians may set different priorities than the ones outlined by sub-national or community sustainability transformation projects [66]. Likewise, the progress at the national and regional levels can be threatened by the cumulative impact of local and sub-national challenges and citizen resistance to transformative policies [66]. The economic years and budgeting at regional and national levels often have a stringent timeline, which may not align with the timeline of sub-national projects, particularly with regards to allocation of resources and duties to local governments [66].

The existing power structure and its nestedness across multiple scales and institutions have created administrative hierarchy, which has, in turn, created dependencies for local and community level sustainability transformation projects from a higher level, e.g., national and regional governments, when it comes to resource mobilization and support [63,64,67]. A majority of our consolidated projects (47 projects, 59%) were operationalized at a local, i.e., community, city or municipality, scale (Figure A3 in the Appendix A). The success of these local and community scale sustainability transformation projects often rely upon national and regional policies and budget [63,64,67]. Moreover, national and regional governments often deny support for local and community scale sustainability transformation projects as they may not scale up to the national and regional level for multi-scale developments. Hence, here we emphasize the notion of “Agency” of the subnational actors at the scale of interest [68,69]. Although the allocation of resources is often shaped by structures and stakeholders at national and regional levels, we focus on the development of capacity of the sub-national, e.g., local and community scale actors for: (1) decision making (actors decide on the priority of problem and which project to undertake through which methods), (2) operationalization (actors implement and operationalize the project on the ground with available resources at hand, e.g., a city implements city-bicycle infrastructure and inhabitants use city bikes), and (3) responsibility (actors take responsibility of the long-term sustainability of the projects, enjoys the benefit and acts at the project failure) [68,69]. Thus, we drift away from “scaling-up” and emphasize rather on “scaling-out”, i.e., how diverse sub-national sustainability transformation projects can learn from each other and implement projects fitting to their local contexts.

3.3.2. Short-Sightedness

Since ours is a scientific and systematic literature review, our scope was limited to analyzing projects and project outcomes that were reported by the published scientific literature. In case of research projects, articles were published shortly after the research was carried out. This gave us little possibility to evaluate if the applied methods worked and if they led to real-world improvements in the long run. Moreover, we could not evaluate the actual contribution of the consolidated projects to the achievement of global SDGs since many of the projects were conducted too recently to make an informed statement about their achievements. Furthermore, we could not include insights from any follow-up evaluation projects that may emerge in the near future. Thus, we insert caution on this short-sightedness that our consolidated literature may present biased narratives that highlight successful strategies, measures and interventions while neglecting possible downsides and failures that may only become apparent long after project completion.

The assessment of the long-term effectiveness of sustainability transformation projects demands long-term monitoring systems. This could be established in several ways: (i) such monitoring systems could be an integral part of the project repositories established in research institutions as suggested above, where the survey teams conduct such monitoring and performance assessment of projects implemented in their regions, (ii) local government entities such as municipalities could establish and conduct such monitoring independently for the projects implemented at their scales, and (iii) each sub-national project can establish such monitoring and performance assessment system at the end of their projects, and hand-over the ownership and responsibility to the communities affected with proper training and skill development.

3.3.3. Exclusion

Only 13 (16%) projects included explicit steps and mechanisms for systematic stakeholder identification, their inclusion and exclusion. For example, Loni Hensler did not only decide which stakeholders to include but actively stated that the participation of specific powerful representatives with opposing interests to the network was restricted [39]. A total of 29 (37%) projects only consulted the stakeholders at the beginning of the projects for system understanding and at the end to give feedback on results. By contrast, nine (11%) conducted an intensive stakeholder engagement during project development and steering of the results. In 41 (52%) projects, scenarios, narratives and pathways that were created by researchers were based on workshop results conducted with stakeholders in participatory setups.

Although marginalized, vulnerable and discriminated stakeholders were represented in our consolidated projects, none of these studies developed mechanisms or frameworks to explicitly identify vulnerable groups in social-ecological systems and there were little implications of the perspectives of these groups in the sustainability transformation processes. We believe that people living in vulnerable situations are at increasing risks of being excluded and thus left behind [70], and also have a lower capacity to prepare for, cope with, and recover from social-ecological risks [71]. Hence, in accordance with Breuer and Spring [72], we urge the strengthening of the role of vulnerable and financially weak groups in critical decision-making processes via the development of an inclusion assessment framework.

4. Concluding Remarks and Outlook

With the “Leave no scale behind” framework, we developed a systematic approach for the implementation of the Agenda 2030 at any scale. The framework aims to direct and support scientists, practitioners and decision makers entrusted with the conversion of the global narrative of sustainable development into real world changes. Our step-by-step approach offers guidance and methodological orientation while leaving enough flexibility to embrace local realities. The methodological processes presented in the framework aim to guide interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary teams including regional and local decision-makers, community leaders and other societal agents interested in steering their communities into a sustainable future in alliance with the Agenda 2030. Thus, our framework complements and expands on the existing frameworks by enabling a translation of the global SDGs into sub-national decision-making scales, ensuring their adherence to global sustainability transformation. In particular, we aim to encourage local agents to initiate processes of sustainability transformation as they are most familiar with the socio-ecological systems and local sustainability challenges. Moreover, they have more direct connections to relevant stakeholders and can play a direct part in realizing project outcomes while contributing to the global SDGs.

Future research should develop mechanism and frameworks for systematically including and evaluation local level sustainability transformation projects and initiatives, realized by local non-scientific stakeholders, which do not immediately seek scientific advice and support. This can be achieved in diverse manners. One possible way is that research institutions such as universities can create repositories of sustainability transformation projects for their regions, where researchers survey and input information about sub-national projects, such as municipal sustainability transformation projects. Our framework can then be modified to, first, guide these projects for their strategic development, and then to monitor and evaluate their performance on a long-term basis. An iterative process can be applied for improving the framework itself based on the learning from such projects.

Sustainability problems tend to be complex social-ecological system problems, where aspects of human behavior are complexly and unpredictably linked with multiple causalities. Moreover, these challenges are non-linear in nature, cross-scale in space and time, and also have an evolutionary character [73]. Thus, the key to understanding sustainability challenges lies in complex system understanding embracing the recognition of what structures contain which latent behaviors, and what conditions release those behaviors—and, where possible, to arrange the structures and conditions to reduce the probability of destructive behaviors and to encourage the possibility of beneficial ones [74,75]. Therefore, setting the scene and understanding the mode of functioning of the social-ecological system in question is a crucial first step in every sustainability transformation project before seeking solutions.

Our analysis of the reviewed articles critically showed that implementation steps were rare and often poorly developed and constructed, particularly in scientific and research-led projects. Hence, scientific articles with a thought-out implementation and follow-up actions were rare. We regard this as a severe flaw in project planning, especially for projects aiming for sustainable development and societal transformation in practice. This flaw is framed as the “research-implementation gap” (RIG), which refers to the challenges of applying scientific knowledge and results in real world societal and institutional transformation [76]. Indeed, the implementation of sustainability projects is certainly challenging since it requires a special skill set to work with multiple stakeholders to co-design, co-produce and co-disseminate knowledge that spans over multiple disciplines and fields of experience [76]. Nevertheless, we argue that these challenges must be embraced for achieving the real-world transformation, particularly by scientists and researchers, since only implementation can lead to the real-world adoption of measures entailed by scientific knowledge and conceptional analyses.

There are several obvious reasons why scientists leave the area of study without carrying out crucial implementation steps such as limited research funds aligned with the short-term projects, a lack of resources needed for implementation, poor political support or simply a lack of long-term commitment of scientists and practitioners. However, measures were suggested to overcome these challenges. For example, Holzer et al. [76] recommended to clearly articulate the mission, objectives and expectations of the projects, to clearly define roles of the involved researchers and partners and to unify long-term observation initiatives with short-term research programs. Moreover, recommendation for the enhancement of knowledge exchange and information accessibility, and incorporating social scientists, administrators and community leaders into decision-making were also made by Holzer et al. [76]. Furthermore, defining different target scales for different projects and people and to initiate a structured, periodic evaluation process might be beneficial for project implementation [76].

It is important to concede that transdisciplinary science and participatory processes enhance implementation [61,62], especially when projects are conducted with local decision-makers, policy departments or local experts, and also when local agents responsible for implementation are educated and trained [61,62]. Discussions between stakeholders during workshops enable knowledge-sharing and strengthen public support for planned implementation actions. Participatory processes help to make communities politically mature as they broaden their horizons and experience that their opinions matter [62]. However, carrying out participatory processes does not necessarily lead to real-world changes, especially if stakeholders are left alone after the end of workshops.

In projects where project participants coincide with responsible agents, stakeholder ownership may be reached. When external actors are summoned for the realization of the projects, outcomes need to be synthesized to educate and inform about the project intentions and the strategies agreed upon in the participatory process. Compiled policy recommendations and management suggestions should be handed to decision-makers. Projects may offer workshops and training to enable political agents to act accordingly. In close collaboration with all involved agents, measures should be incorporated into existing local institutions and requirements for new institutional settings to facilitate networking, knowledge-sharing and implementation actions should be discussed. Moreover, provision of information to the broader public to raise awareness and to enhance public support is crucial. A thorough understanding of the vulnerable groups’ needs and their values, beliefs and viewpoints helps to find relevant solutions and strategies through real-world experimentation, collective learning and continuous adaptation [77].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B.; methodology, A.B.; formal analysis, K.K.; data curation, K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, K.K.; writing—review and editing, A.B. and K.K.; visualization, A.B. and K.K.; supervision, A.B.; project administration, A.B.; funding acquisition, A.B. and K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was partly funded by “Staff Mobility Exchange—Academic Teaching (STA) ERASMUS+” through the Karlstad University International Office, which enabled mobility and exchange between Karlstad University and Leuphana University Lüneburg.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The literature database used in this review is provided in the Appendix A with some overview information.

Acknowledgments

Cormac Walsh provided valuable comments on an earlier draft that helped to substantially improve this manuscript. We are also thankful for the critical comments of the anonymous reviewers that have been addressed in the revised version of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

The systematic steps followed for consolidating sustainability transformation projects reported in the published scientific literature according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) framework developed by Moher et al. [18].

Figure A1.

The systematic steps followed for consolidating sustainability transformation projects reported in the published scientific literature according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) framework developed by Moher et al. [18].

Figure A2.

The distribution of global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) across the consolidated sustainability transformation projects according to how they were addressed and aligned.

Figure A2.

The distribution of global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) across the consolidated sustainability transformation projects according to how they were addressed and aligned.

Figure A3.

Geographic distribution of the consolidated sustainability transformation projects in this review.

Figure A3.

Geographic distribution of the consolidated sustainability transformation projects in this review.

Figure A4.

Temporal scales of the consolidated sustainability transformation projects in this review. Hatched areas indicate that projects were launched in different years.

Figure A4.

Temporal scales of the consolidated sustainability transformation projects in this review. Hatched areas indicate that projects were launched in different years.

Figure A5.

Involved stakeholders and stakeholder-groups across the consolidated sustainability transformation projects.

Figure A5.

Involved stakeholders and stakeholder-groups across the consolidated sustainability transformation projects.

Table A1.

The final literature database included in this literature review with the authors’ disciplines, covering Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), spatial scale and countries where the studies were conducted and their temporal scales. The blue shaded cells under the SDGs column indicate studies where authors identified the SDGs themselves. Detailed reference information is provided at the bottom of this table.

Table A1.

The final literature database included in this literature review with the authors’ disciplines, covering Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), spatial scale and countries where the studies were conducted and their temporal scales. The blue shaded cells under the SDGs column indicate studies where authors identified the SDGs themselves. Detailed reference information is provided at the bottom of this table.

| Authors and Articles | Disciplines of Authors | SDGs Covered | Spatial Scale | Country | Temporal Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acheampong et al., 2020 [38] | Science and Engineering, Forest Science | 1, 2, 15 | Ongwam II Forest Reserve in the Ashanti Region | Ghana | 2030 |

| Riggs et al., 2020 [78] | Tropical Environmental and Sustainability Science, Forest Science, Environment and Development, Conservation Science, Wildlife Conservation, Sustainable Earth Resources | 1, 10, 12, 13, 15 | Keo Seima Wildlife Sanctury + Northern Plains | Cambodia | - |

| Baccar et al., 2021 [79] | Water Science, Agronomy | 2, 6 | Berambadi Watershed | India | - |

| Bandari et al., 2022 [30] | Ecology, Life Science, Environmental Science | 2, 6, 8, 13, 15 | Goulburn-Murray Region | Australia | 2030 |

| Bernardo & D’Alessandro, 2019 [80] | Law, Economics & Management | 7 | Cascina Municipality | Italy | - |

| Bhave et al., 2018 [32] | Economics, Political Science, Sustainable Research, Climate Change Economics and Policy, School of Earth and Environment, Centre for Analysis of Time Series | 6, 11, 12 | Cauvery River Basin in Karnataka (CRBK) | India | 2055 |

| Blanco-Gutiérrez et al., 2020 [81] | Polytechnic, Agricultural Economics, Statistics and Business Management, Institute of Tropical Agriculture, Applied Mathematics, Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation | 2, 8, 15 | Guarayos & Tapajós National Forest | Bolivia & Brazil | - |

| Bonatti et al., 2018 [82] | Agricultural Landscape Research, Food Science and Technology | 2, 3, 5, 10, 13 | 4 villages in the regions Morogoro and Dodoma | Tansania | - |

| Borgström et al., 2021 [83] | Sustainable Development, Environmental Science, Engineering | 11 | Flaten landscape | Sweden | 2050 |

| Boschetti et al., 2015 [84] | Ocean and Atmosphere Flagship, Land and Water Flagship | holistic concept | Several cities | Australia | 2050 |

| Breuer & Spring, 2020 [72] | German Development Institute, Multidisciplinary Research Centre | holistic concept | Cuautla River Basin | Mexiko | 2030 |

| Bruley et al., 2021 [85] | Ecology, Environment & Society, Civil, Environmental and Geomatic Engineering, Spatial and Landscape Development, Planning of Landscape and Urban Systems, Landcare Research | 6, 7, 13, 15 | Two communities in the central French Alps | France | 2040 |

| Camarena et al. 2021 [24] | Management, Finance, International Relations | 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15, 16, 17 | Guaviare | Columbia | 2035 |

| Capitani et al., 2016 [86] | Institute for Tropical Ecosystems, Agricultural Engineering and Land Planning, Forest Biology, Biology, Sustainability Research Institute | 8, 9, 11, 12, 13 | - | Tanzania | 2025 |

| Carmona et al., 2013 [87] | Agricultural Economics, Geography and Environment | 2, 6, 12 | Guadian River Basin | Spain | - |

| Castelli et al., 2017 [88] | Agricultural, Food and Forestry Systems, Institute for Cooperation | 3, 6, 7, 9, 11, 12 | Piraí River Basin area, Santa Cruz de la Sierra | Bolivia | - |

| Cheshmehzangi, 2021 [89] | Architecture & Build Environment | 7, 11, 13 | Songa’O (Fenghua) | China | 10 + years |

| Cheung & Oßenbrügge, 2020 [90] | Institute of Geography, Geography and Planning | 7 | Hamburg | Germany | 2030 + 2050 |

| Coleman et al., 2017 [40] | Plant and Soil Science, Community Development and Applied Economics | 3, 6, 7, 9, 11, 12 | Lake Champlain Basin | Canada | up to 40 years |

| Comer et al., 2015 [91] | Environmental Science and Forestry, Environmental and Life Sciences, Engineering and Public Policy, Natural Resources and Environment | holistic concept | Great Lakes, St. Lawrence River Basin | USA & Canada | 2063 |

| Cost & Lovecraft, 2021 [92] | Education & International Arctic Research, Arctic Policy Studies | holistic concept | Northwest Arctic Borough | USA | 2040 |

| Delafield et al., 2021 [93] | Net-zero energy transition | 7 | Local communities | - | 2030 |

| Dall’O et al., 2013 [94] | Architecture, Built Environment and Construction Engineering, Management and Production Engineering | 7, 9, 11 | Melzo, Lombardy | Italy | 2030 |

| Dassen et al., 2013 [95] | Environmental Assessment | 11 | - | Netherlands | 2040 |

| Eakin et al., 2019 [96] | Sustainability, applied Mathematics and System Research, Sustainability Science | 3, 6, 9, 11 | Mexico City | Mexiko | - |

| Eames et al., 2013 [97] | Low Carbon Research Institute, School of Construction Management and Engineering, Centre for Sustainable Urban and Regional Futures | 11 | Cardiff City Region, Greater Manchester | Great Britain | 2050 |

| Ferguson et al., 2013 [98] | Geography and Environmental Science, Research Institute for Transitions | 6, 11, 12 | Melbourne | Australia | 2020, 2040, 2060 |

| Ferguson et al., 2018 [42] | Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, Anthropology | 3, 6, 7, 9, 11, 12 | Willamette River Basin | USA | 2100 |

| Forni et al., 2018 [99] | Environment Institute, Engineering and Water Science, | 3, 6, 7, 9, 11, 14, 15 | - | Argentina | 2050 |

| Gaudreau & Gibson, 2015 [100] | Environment and Resource Studies | 1, 7, 8, 10, 12, 15 | - | Senegal | - |

| Gil et al., 2019 [101] | Plant Production System, Environmental Assessment, Institute of Sustainable Development, Animal Production Systems | 2, 13 | - | Netherlands | 2050 |

| Girard et al., 2015 [102] | Water and Environmental Engineering, Scientific Computing | 6, 8, 11, 13 | Orb river basin | France | 2030 |

| Givens et al., 2018 [103] | Sociology, Social Work and Anthropology, Water Research Centre, Centre for Environmental Research, Education & Outreach, Civil and Environmental Engineering, College of Law and Waters | 2, 3, 6, 7 | Yakima River Basin | USA | - |

| Goldstein et al., 2021 [104] | non-academic (Decsion Ware Group LLC), consulting company | 7 | - | Costa Rica | 2050 |