Multi-Objective Optimization of Monitoring Point Placement in Water Supply Networks Based on Pressure-Driven Analysis and the Virtual Node Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

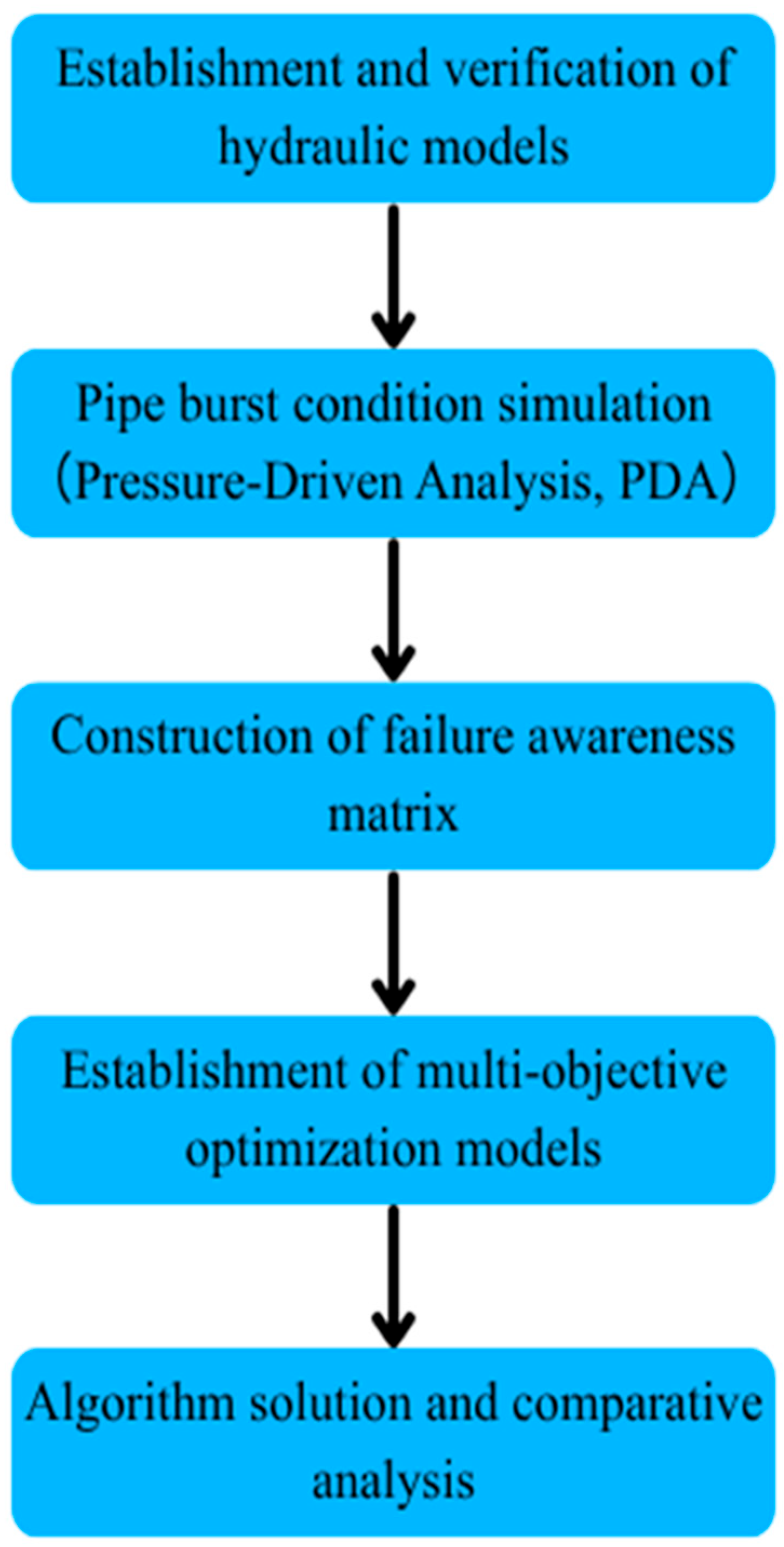

- Hydraulic Model Development and Calibration: A high-fidelity hydraulic model of the water distribution network (WDN) is developed using EPANET 2.2. This stage involves rigorous calibration of nodal water demands, boundary conditions, and steady-state pressure distributions to establish a reliable baseline for subsequent simulation of pipe burst scenarios.

- Pipe Burst Scenario Simulation Based on Pressure Driven Analysis (PDA): To accurately represent hydraulic behavior under pipeline failure conditions, pressure-driven analysis (PDA) is adopted in combination with the Wagner model. The virtual node method (VNM) is employed to simulate pipe burst events at different pipe segments without altering the original network topology.

- Construction of the Fault Awareness Matrix: A binary fault awareness matrix is constructed by evaluating nodal pressure variations against a predefined background noise threshold. This matrix quantitatively characterizes the sensitivity and spatial awareness of each candidate monitoring point and serves as the fundamental input for the subsequent optimization process.

- Construction of a Multi-Objective Optimization Model: A bi-objective optimization model is formulated to address the trade-off between maximizing monitoring coverage (fault detectability) and minimizing the total number of monitoring points (economic cost). Practical engineering constraints, such as minimum spatial separation between monitoring points, are incorporated to ensure the feasibility of the deployment scheme.

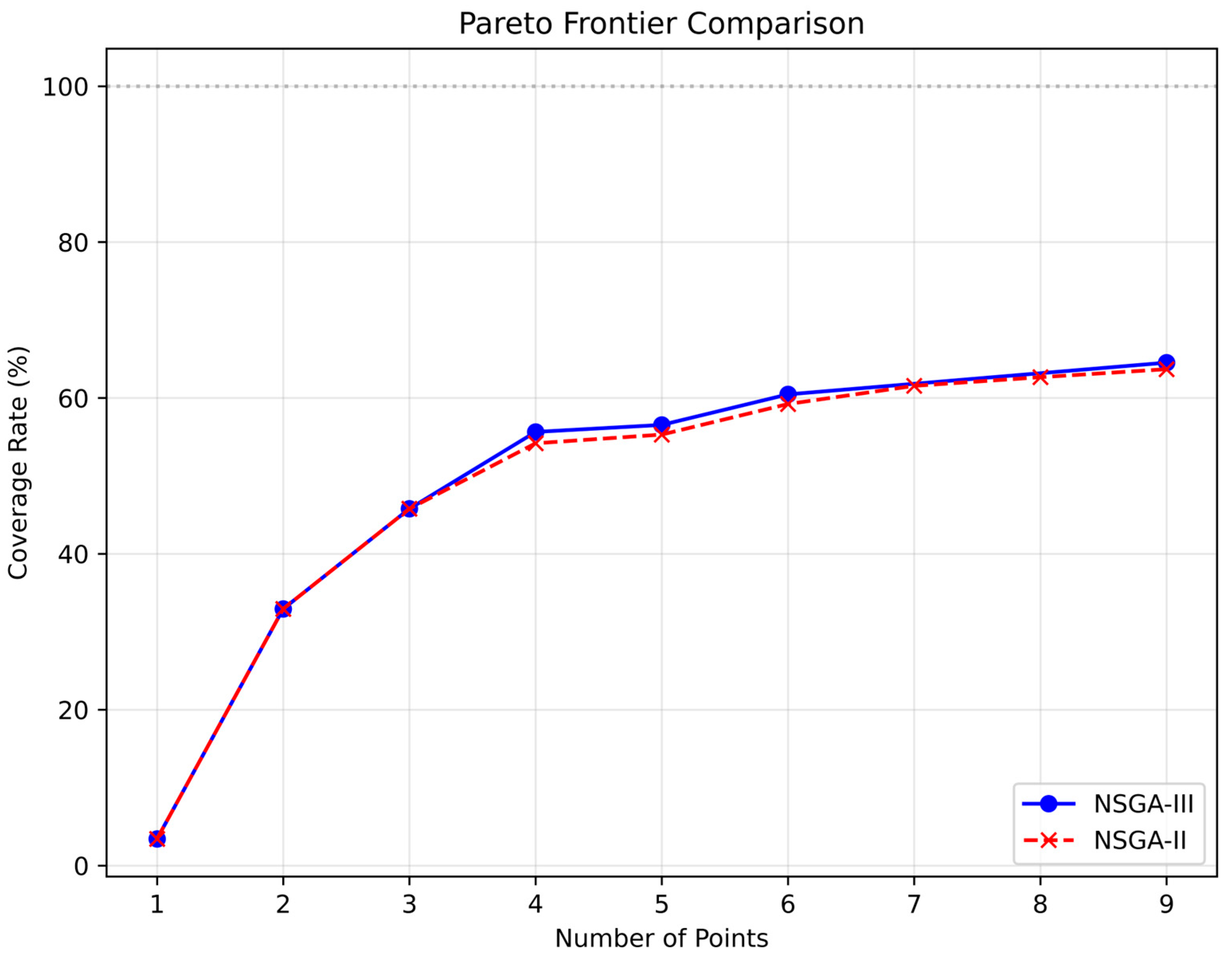

- Algorithm Solution and Performance Comparison: Two advanced multi-objective evolutionary algorithms, NSGA-III and NSGA-II, are employed to solve the optimization problem. Their performance is systematically evaluated using metrics including hypervolume (HV) and spacing (SP), with respect to convergence behavior, solution diversity, and computational efficiency in complex WDN environments.

2. Methods

2.1. Overall Research Framework

2.2. The Virtual Node Method (VNM)

2.3. The Pressure-Driven Analysis (PDA)

2.4. Failure Perception Matrix for Water Distribution Networks

2.5. Multi-Objective Optimization Formulation

2.6. Multi-Objective Optimization Algorithms

3. Results and Discussion

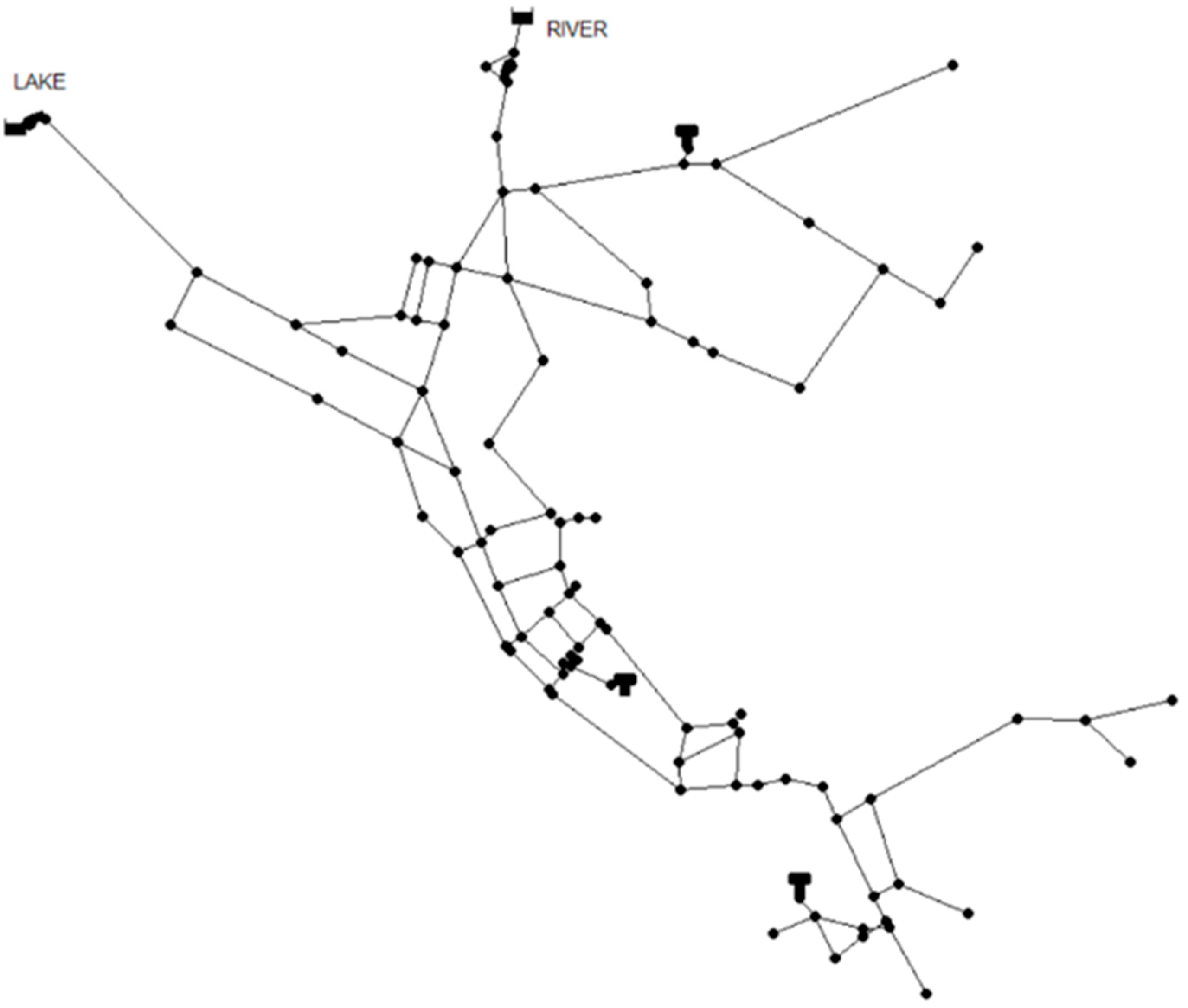

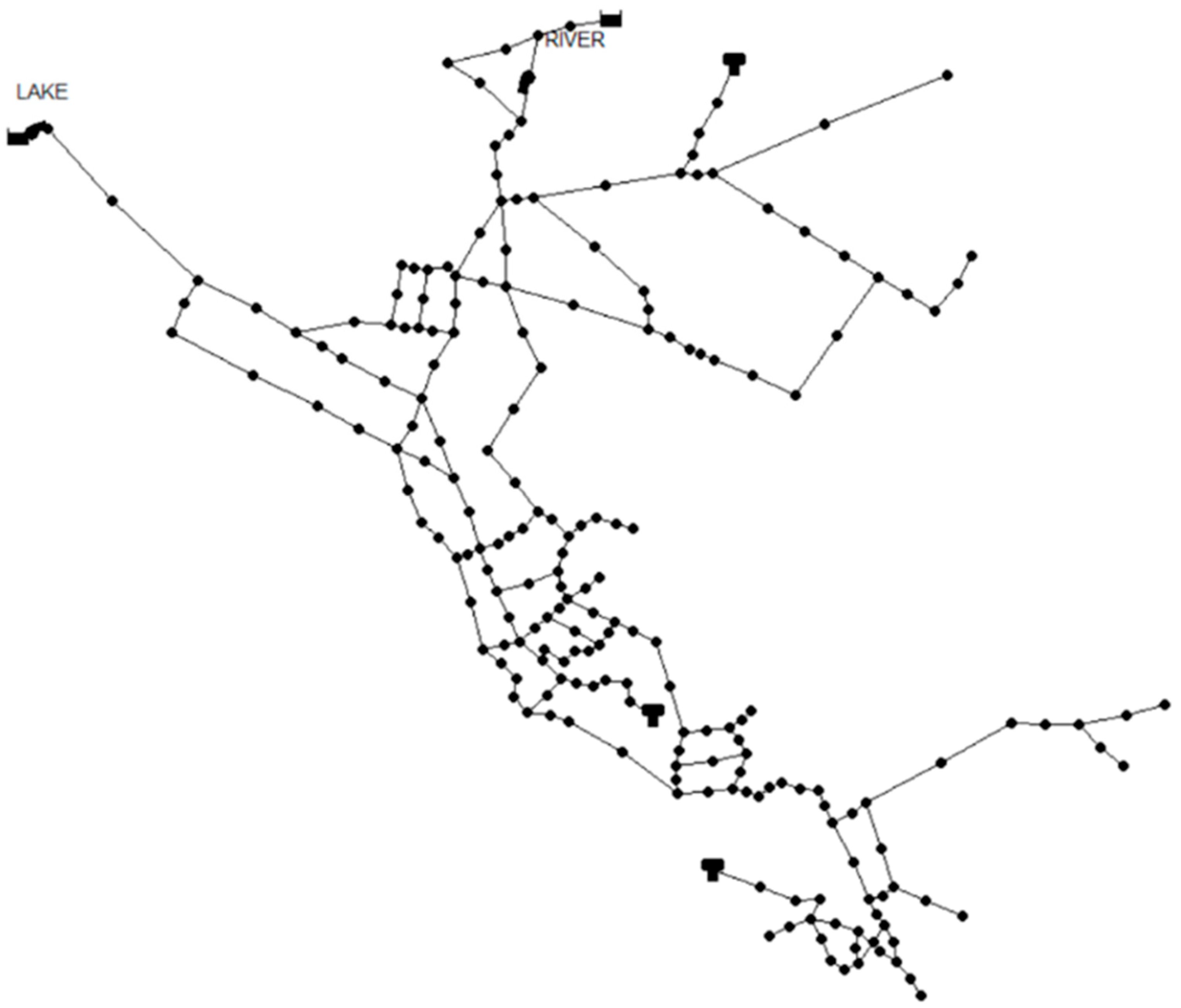

3.1. Research Cases and Experimental Setup

3.2. Optimization Results and Algorithm Performance Evaluation

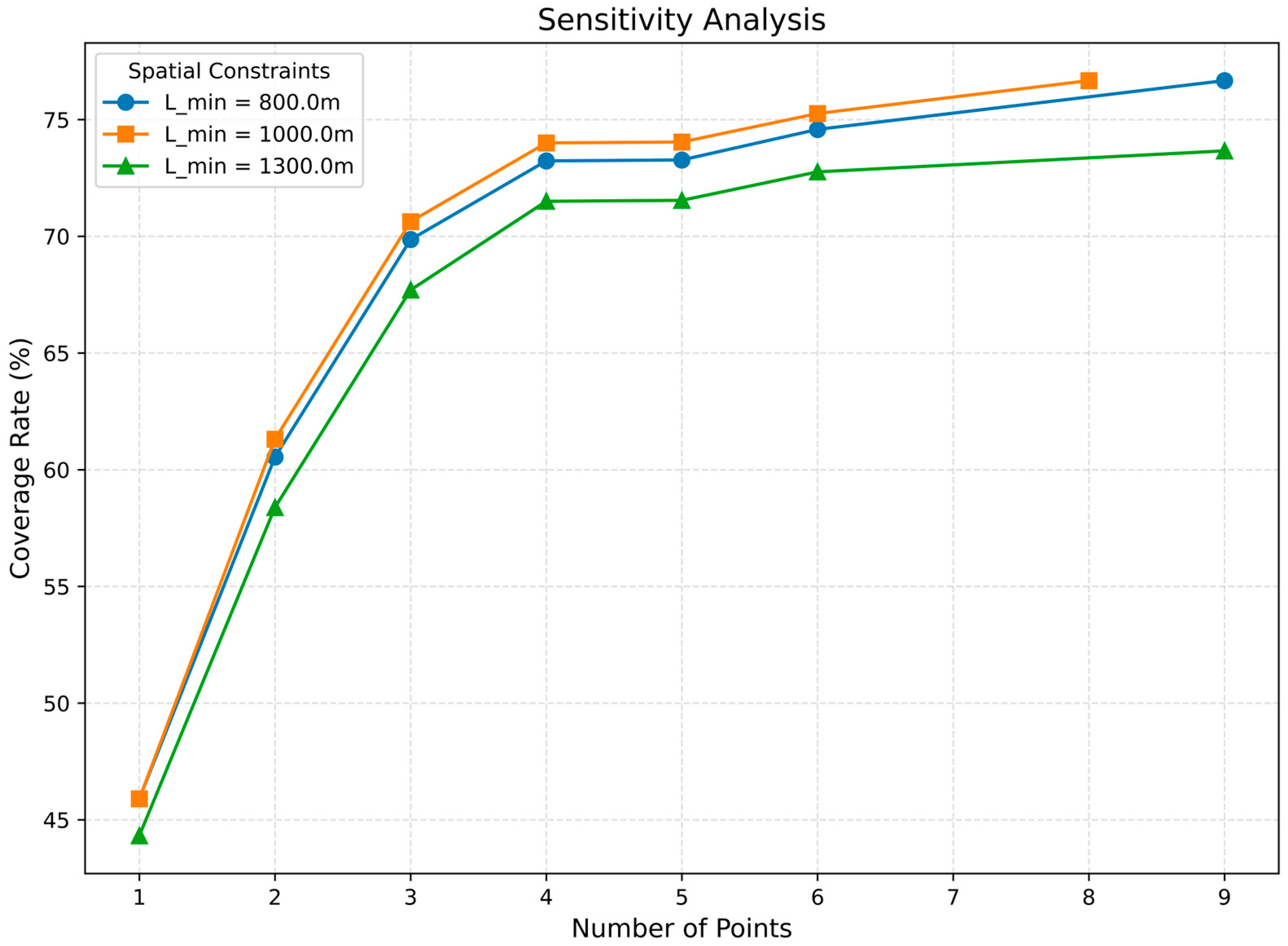

3.3. Sensitivity Analysis of Key Parameters

3.4. Extended Case Study

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, B.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, H.; Tu, J.; Wang, T.; Zhao, M.; Ding, X.; Wu, F.; Liu, W. Research on Multi-Factor Optimization Method for Water Quality Monitoring Point Layout Based on Hydraulic Model. J. Chongqing Univ. 2019, 42, 92–100. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.; Du, K.; Meng, F.; Luo, X.; Zhou, M.; Song, Z. Multi-Objective Optimization of Pressure Monitoring Points for Pipe Burst Detection in Water Supply Networks. China Water Wastewater 2023, 39, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Zhou, H.; Yu, T. Layout of Hydraulic Calibration Monitoring Points Based on Node Similarity in Water Supply Networks. Sci. Technol. Bull. 2023, 39, 52–55+75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. Optimization of Pressure Monitoring Point Layout and Leakage Localization in Water Supply Networks Based on Hydraulic Modeling. Master’s Thesis, Qingdao University of Technology, Qingdao, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. Pipe Burst Localization in Water Supply Networks Based on Model-Driven and Pipe Flow Sensitivity Analysis. Master’s Thesis, Kunming University of Science and Technology, Kunming, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, H. Optimization of Pressure Monitoring Point Layout and Pipe Burst Early Warning in Water Supply Networks Based on Swarm Intelligence Algorithms. Master’s Thesis, Qingdao University of Technology, Qingdao, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Yang, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, K.; Zhou, X. Optimization of Pressure Monitoring Point Layout in Water Networks Using Particle Swarm Improved FCM Clustering Algorithm. China Water Wastewater 2021, 57, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Yu, T.; Shao, Y. Optimal Placement of Pressure Measurement Points for Pipe Burst Monitoring in Water Supply Networks. China Water Wastewater 2020, 36, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diwold, K.; Ruhnke, T.; Middendorf, M. Sensor Placement in Water Networks Using a Population-Based Ant Colony Optimization Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Computational Collective Intelligence: Technologies and Applications, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, 10–12 November 2010; pp. 426–437. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, S.; Cheng, J.; Wu, X.; Fang, X.; Wu, Q. Pressure Sensor Placement in Water Supply Network Based on Graph Neural Network Clustering Method. Water 2022, 14, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Ruiz, I.; Lopez-Estrada, F.-R.; Puig, V.; Valencia-Palomo, G.; Hernandez, H.-R. Pressure Sensor Placement for Leak Localization in Water Distribution Networks Using Information Theory. Sensors 2022, 22, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Shuai, J.; Shuai, Y.; Hua, L.; Xu, K.; Xie, D.; Mei, Y. Efficient prediction method of triple failure pressure for corroded pipelines under complex loads based on a backpropagation neural network. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 231, 108990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyi, W.; Xiangwei, Z.; Jiaying, W.; Tao, T.; Kunlun, X.; Hexiang, Y.; Shuping, L. Optimal sensor placement for the routine monitoring of urban drainage systems: A re-clustering method. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 335, 117579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Du, K.; Tu, J.; Dong, W. Optimal Placement of Pressure Sensors in Water Distribution System Based on Clustering Analysis of Pressure Sensitive Matrix. Procedia Eng. 2017, 186, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejjari, F.; Sarrate, R.; Blesa, J. Optimal pressure sensor placement in water distribution networks minimizing leak location uncertainty. In Proceedings of the Computing and Control for the Water Industry (CCWI2015)—Sharing the Best Practice in Water Management, Leicester, UK, 2–4 September 2015; pp. 953–962. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, Y.; Lv, M.; Li, S.; Su, Y.; Dong, S. Optimized Sensor Placement of Water Supply Network Based on Multi-Objective White Whale Optimization Algorithm. Water 2023, 15, 2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y. Optimization of Pressure Monitoring Point Placement and Multi-Scenario Leakage Localization Based on Hydraulic Model of Water Supply Networks. Master’s Thesis, Qingdao University of Technology, Qingdao, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Choi, S.-H. Flow analysis using RDDA method with actual usage in water distribution network. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Singh, I.V.; Mishra, B.K.; Rabczuk, T. Modeling and simulation of kinked cracks by virtual node XFEM. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2015, 283, 1425–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molino, N.P.; Bao, Z.; Fedkiw, R. A virtual node algorithm for changing mesh topology during simulation. ACM Trans. Graph. 2004, 23, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Long, Z.; Shao, Y.; Chu, S.; Yu, T. Optimization of Pressure Monitoring Point Layout for Pipe Burst Monitoring in Water Supply Networks. China Water Wastewater 2023, 39, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J.M.; Shamir, U.; Marks, D.H. Water Distribution Reliability: Simulation Methods. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 1988, 114, 276–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zyl, J.E.; Cassa, A.M. Modeling Elastically Deforming Leaks in Water Distribution Pipes. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2014, 140, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Guo, J.; Jin, J. Online Optimization of Pressure Monitoring Points in Water Supply Networks for Pipe Burst Detection. Water Supply Technol. 2023, 17, 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Y. Optimization of Pressure Monitoring Points in Water Supply Networks Based on K-means Clustering. Build. Saf. 2014, 29, 74–77. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Xue, H.; Zhang, W. Optimization of Pressure Monitoring Point Placement in Water Supply Networks for Fault Diagnosis. Civ. Archit. Environ. Eng. 2018, 40, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Z.; Wang, P.; Wang, F.; Huang, S.; Wang, L.; Tian, S.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, J. Optimization and Application of Network Monitoring Point Location Based on Comprehensive Safety Evaluation. China Water Wastewater 2023, 39, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Yang, K.; Chen, J.; Qian, L.; Li, Z.; Wu, J. Multi-Objective Optimization Scheme for Regional Water Resources Based on NSGA-III. People’s Yellow River 2024, 46, 79–84+153. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, R.; Wang, Z.; Long, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Tu, Y.; Li, B. Optimization Model for Water Quality Monitoring Points in Water Supply Networks Based on Risk Assessment. China Water Wastewater 2021, 37, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Chen, Y.; Xu, G. Optimizing Sensor Placement and Quantity for Pipe Burst Detection in a Water Distribution Network. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2020, 146, 04020088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Multi-Objective Optimization of Water Quality Monitoring Point Placement in Water Supply Networks. Master’s Thesis, Lanzhou University of Technology, Lanzhou, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Number of Points | Selected Nodes | Coverage Rate |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 213 | 45.9 |

| 2 | 107; 213 | 61.31 |

| 3 | 15; 107; 213 | 70.63 |

| 4 | 107; 131; 141; 213 | 74 |

| 5 | 107; 131; 141; 183; 213 | 74.04 |

| 6 | 107; 131; 141; 183; 206; 213 | 75.26 |

| 8 | 101; 107; 131; 141; 183; 206; 213; 261 | 76.67 |

| Number of Points | Selected Nodes | Coverage Rate |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 131; 145 | 45.03 |

| 3 | 103; 131; 145 | 59.16 |

| 4 | 103; 131; 145; 213 | 73.23 |

| 5 | 103; 131; 145; 183; 213 | 73.27 |

| 6 | 103; 131; 145; 183; 206; 213 | 74.49 |

| 7 | 103; 117; 131; 145; 183; 206; 213 | 75.66 |

| 8 | 61; 103; 117; 131; 145; 183; 206; 213 | 75.66 |

| Number of Points | Selected Nodes | Coverage Rate |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 118 | 3.43 |

| 2 | 18; 118 | 32.94 |

| 3 | 83; 18; 118 | 45.78 |

| 4 | 83; 109; 18; 118 | 55.64 |

| 5 | 83; 109; 18; 118; 33 | 56.54 |

| 6 | 83; 109; 18; 100; 118; 33 | 60.46 |

| 9 | 83; 109; 18; 100; 118; 125; 33; 4; 65 | 64.53 |

| Number of Points | Selected Nodes | Coverage Rate |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 119 | 3.43 |

| 2 | 119; 63 | 32.94 |

| 3 | 83; 119; 63 | 45.78 |

| 4 | 83; 88; 119; 63 | 54.18 |

| 5 | 83; 88; 27; 119; 63 | 55.3 |

| 6 | 83; 88; 100; 27; 119; 63 | 59.22 |

| 7 | 83; 88; 100; 27; 119; 4; 63 | 61.55 |

| 8 | 83; 88; 100; 27; 119; 4; 57; 63 | 62.66 |

| 9 | 83; 88; 100; 27; 119; 4; 41; 57; 63 | 63.69 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, Q.; Chen, A.; Li, Z. Multi-Objective Optimization of Monitoring Point Placement in Water Supply Networks Based on Pressure-Driven Analysis and the Virtual Node Method. Sustainability 2026, 18, 1460. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031460

Li Q, Chen A, Li Z. Multi-Objective Optimization of Monitoring Point Placement in Water Supply Networks Based on Pressure-Driven Analysis and the Virtual Node Method. Sustainability. 2026; 18(3):1460. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031460

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Qingfu, Ao Chen, and Zeyi Li. 2026. "Multi-Objective Optimization of Monitoring Point Placement in Water Supply Networks Based on Pressure-Driven Analysis and the Virtual Node Method" Sustainability 18, no. 3: 1460. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031460

APA StyleLi, Q., Chen, A., & Li, Z. (2026). Multi-Objective Optimization of Monitoring Point Placement in Water Supply Networks Based on Pressure-Driven Analysis and the Virtual Node Method. Sustainability, 18(3), 1460. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031460