Abstract

In this study, the effects of nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC) on the performance of cementitious composites have been explored. The composite mixtures contained cement that was replaced by 40% slag to prepare a high-performance composite, along with fine aggregate and NFC. The air content reduced drastically in the presence of NFC; hence, air entraining admixture (AEA) was added to maintain the criteria of CSA A23.1. In total, eight mixtures were tested with varying dosages of NFC of 0.25%, 0.5%, and 0.75%, where four mixtures contained AEA. Different properties such as fresh (slump flow, air content), mechanical (compressive strength, tensile strength, flexural strength), and durability (rapid chloride penetration, rapid chloride migration, bulk resistivity, resistance against freeze–thaw) have been investigated to evaluate the effectiveness of NFC with high-volume slag after 7 and 28 days. The microstructure of the composites and the distribution of the nanofibers within the paste are also studied by using SEM images. The results revealed that NFC improved the specimen’s splitting strength, flexural strength, and durability. Splitting tensile strength increased by up to 50% at 0.75% NFC, while flexural strength improved by 162% at 0.5% dosage. A negative impact on the compressive, flexural, and durability properties was observed for the 0.75% dosage of NFC due to fiber agglomeration, whereas the 0.5% dosage exhibited the best overall performance. The optimum NFC dosage is found to be 0.25–0.5% which yields a high-strength and durable composite. This research will provide an understanding of the effect of air concentration and NFC on cementitious composites.

1. Introduction

Concrete possesses a set of well-defined specifications and mechanical properties that determine its suitability for various construction applications. As concrete is the most common infrastructure material, it is imperative to pay attention to the durability and rapid strength gain in addition to the mechanical properties. The incorporation of nanomaterials into cementitious composites uncovered novel possibilities to improve the performance of concrete in terms of strength, durability, and sustainability. The use of nanomaterials can speed up early-age development and accelerate the hydration and microstructural densification of high-performance cementitious composites [1,2,3]. Nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC), processed from renewably managed forests, is a type of nanomaterial that can refine and reinforce the cement matrix on a nanoscale.

NFC helps to a balance between fresh, mechanical, and durability properties along with excellent dimensional stability and coherence with the substrate concrete [1]. Because of the bridging effect of NFC in the cement matrix, it adds reinforcement and minimizes crack propagation, thus improving the mechanical characteristics [4]. Kolour et al. (2018) [5] reported that while higher dosages reduced strength, a small amount of NFC (0.5%) boosted the compressive strength up to 28%. The results suggest that NFC is capable of being considered as a plant-based innovative natural internal curing agent for cementitious composites.

The load bearing ability of concrete can be significantly improved by the inclusion of NFC. When higher loads are imposed, NFC reduces crack propagation through the bridging effect [6]. Onuaguluchi et al. (2014) [7] found that the addition of NFC to cement paste enhanced the flexural strength due to the increased degree of hydration and the hydrophilicity of NFC. The greatest flexural strength of 6.5 MPa was achieved with 0.1% NFC as percent mass of cement while the reference composite without NFC reached a flexural strength of 3.1 MPa. Aziz et al. (2021) [6] found that the compressive strength of the concrete specimens increased with the increase in the proportion of NFC. The authors concluded that a 0.25 wt% and 0.75 wt% NFC is optimum for concrete based on several destructive and non-destructive tests. El-Feky et al. (2019) [8] found that, in comparison to the control mix, NFC at 0.04% by cement weight improved the tensile and flexural strengths by about 40% and 30%, respectively, while the maximum improvement in the compressive strength was only about 11%. In addition to that, 0.25% and 0.75% NFC provided maximum resilience to chloride ion permeation, attributed to the pore interconnection and dense microstructure formation [6].

The use of a high-volume of supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) like slag in concrete is a sustainable alternative for cement, which takes part in improving the durability of concrete. High-performance cementitious composites with a high volume of slag have long-term durability properties [9,10]. Previous studies have shown that slag improves the workability, reduces the heat of hydration, enhances the resistance to chemical attack, and increases the long-term strength of concrete despite having weak early-stage properties [11,12,13]. However, the use of high volume SCMs results in a slower setting time and strength development [2,14]. NFC can speed up the kinetics of cement hydration, and thus can counteract that delay caused by SCMs and make the mix set faster [15]. This corresponds to NFC’s internal curative action and improved hydration, which facilitates to refine the high-volume slag matrix [1]. The internal curing mechanism of NFC with high-volume slag was substantiated by Sadoon et al. (2024) [1]; composites gradually dropped by up to 16% after 14 days till 90 days, demonstrating slag’s catalyzed pozzolanic reactivity in the matrix, which usually begins after 28 to 56 days.

Due to the climatic, environmental, and construction challenges, proper air content enhances durability by reducing shrinkage, cracking, and vulnerability to sulfate and chloride attacks caused by saline water exposure. In cold regions, adequate air content ensures the formation of a well-distributed network of microscopic air voids, which provide the space for water to expand when it freezes, thereby reducing internal stresses and preventing cracking. During freezing, the concrete undergoes volume expansion and the air voids help to accommodate this expansion and reduce the internal ice pressure. The pore microstructure of the cement paste is a primary factor affecting the resistance to scaling. Scaling is the main cause of destruction on concrete roads and bridges. It is a result of frost and defrosting agents. Scaling causes the top layer of the concrete to break into thin layers. Therefore, the air content is important for the durability of the cementitious composite [16]. Recent studies indicate that NFC may interact with entrained air voids, influencing transport properties and potentially introducing durability trade-offs, particularly under chloride exposure and freeze–thaw conditions [1,3]. NFC has been proven to enhance the microstructure and pore connectivity, which leads to a higher resistance to water and chloride ion penetration [1,3]. This hinders the critical saturation level required for the freeze–thaw damage. Thus, NFC-modified composites are reported to have minor mass loss (<30 g/m2) and low visual damage (rating 0–1), attributed to the adequate air content, meeting CSA A23.1 (2019) [17] requirements for freeze–thaw resistance [3].

While the existing studies report performance boosts of cementitious composites from NFC incorporation, there is a lack of comprehensive studies aiming to study its effects on both the mechanical and durability properties in high-volume slag composites. These gaps led this research to aim to study the change in the properties of cementitious composites with varying dosages of NFC. As NFC is a new material being introduced in cementitious composites, its effects on different fresh, mechanical, and durability properties have been explored by several researchers. It was identified during previous studies conducted at Lakehead University that the addition of nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC) reduced the air content of the cementitious composite to less than 1%. The air content decreased from 5% to 0.5% with just a small addition of NFC to the mixture. According to CSA A23.1 (2019) [17], the air content of residential structures should be in the range of 3 to 8%. Thus, this study explores different fresh, mechanical, and durability properties of cementitious composites incorporating NFC with and without air entraining admixture. Eight different mixtures have been prepared and tested, four with added air and four without. Understanding these properties is essential for engineers and builders to tailor concrete mixes to meet specific project requirements, ensuring the longevity and resilience of the constructed structures.

2. Research Program

2.1. Materials

The primary binder material used in this study was general use (GU) cement. A total of 40% of the cement was replaced by ground granulated blast furnace slag of Grade 100 for all the mixtures. Both the binders complied with CSA A3001 (2018) [18]. Table 1 presents the chemical and physical properties of these binders.

Table 1.

Chemical and physical properties of cement and slag.

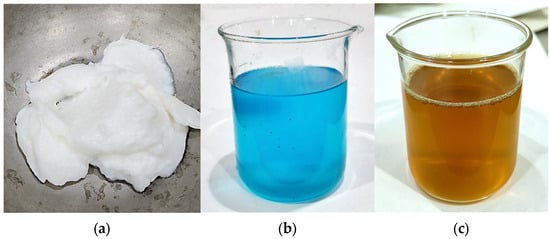

Nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC) made from wood pulp, in the form of a pre-dispersed paste manufactured by Performance Biofilaments, Vancouver, BC, Canada, was employed at three different dosages, 0.25%, 0.5%, and 0.75%, by mass of the binder content. The pulp fibers were separated into single fibers, and a single fiber was broken down into macrofibrils and then into nanofibrils. The reference mixtures did not have any NFC added. The NFC had a solid content of 5% (wet basis), aspect ratio of 1250, tensile strength of 115 MPa, specific gravity of 1.5, and modulus of elasticity of 12 GPa. Locally available sand was used as a fine aggregate. The sand had a fineness modulus of 2.24, absorption of 1.52%, and specific gravity of 2.67 according to ASTM C136 (2019) [19] and ASTM C128 (2022) [20]. A superplasticizer, namely Sika ViscoCrete 2100 (Sika Corporation, Lyndhurst, NY, USA), was used to improve the flowability of the mixtures. An air entraining admixture, namely Sika AEA-14 (Sika Corporation), was also added to maintain the air content within 3 to 8% following the guidelines of CSA A23.1 (2019) [17]. Figure 1 shows the NFC, superplasticizer, and air entrainer.

Figure 1.

(a) Nanofibrillated cellulose, (b) superplasticizer, (c) air entrainer.

2.2. Mix Proportion

A total of eight mixtures were cast in two batches with varied combinations of NFC and air entrainer as presented in Table 2. Four of the mixtures were prepared with 4–6% air entraining admixture (AEA). Previous studies explored the mechanical and durability properties of cementitious composites with up to 0.5% dosage of NFC and reported that NFC is more effective at lower dosages [1,3]. Thus, the amount of NFC was varied by 0.25%, 0.5%, and 0.75% by mass of the binder content in this study. Each batch contained a mixture without NFC, which acted as the control mixture. Slag replaced cement at a 40% level consistently throughout the mixtures in a weighted manner, meeting HVSCM-2 standards for high SCM concretes as per CSA A23.1 [17]. The sand-to-cement ratio of 2:1 and the water-to-binder (w/b) ratio of 0.3 were kept constant in all the mixtures. The mix proportion, including the choice of slag content, sand, and w/b ratio, was adopted following the previous studies [3,10]. A high range superplasticizer classified as Type F under ASTM C494 (2019) [21] and air entraining admixture (AEA) was incorporated into the mixtures.

Table 2.

Mix design for 1m3 composite.

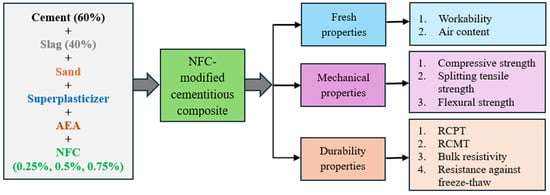

The dry ingredients—cement, slag, and sand—were first mixed together. The admixtures and NFC were added to the water, making up the wet ingredients. This step ensured the better dispersion of NFC into the mixture. Next, the wet ingredients were added to the mixer and mixed until homogeneity was achieved. The specimens were covered with a polythene sheet for 24 h and then demolded. After demolding, the specimens were placed in curing tanks where relative humidity and temperature were maintained at 95% and 22 ± 2 °C, respectively. The samples were kept in the curing tanks until tests were conducted on days 7 and 28. A detailed research program is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Details of the research program.

2.3. Testing Methods

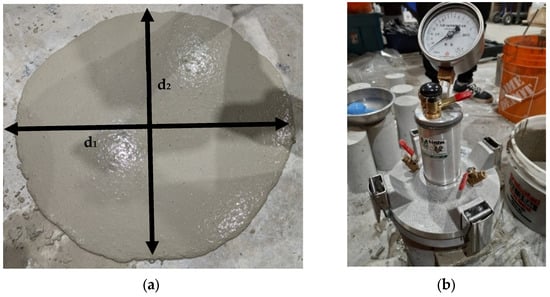

2.3.1. Fresh Properties

For fresh properties, the slump flow test is conducted following ASTM C1611 (2021) [22] to determine the flowability of the mixtures. The freshly mixed concrete was placed in the mold in the upright position. The concrete was poured into the mold and was not tamped or vibrated. Then, the mold was raised, and the measurements were taken when the concrete stopped spreading. Two diameters are measured in orthogonal directions, and their average is taken as the slump flow as shown in Figure 3a. Fresh air content is measured following ASTM C231 (2024) [23] using a Type B air content meter (Figure 3b). Additionally, the volume of permeable pore space or air void in the hardened concrete was calculated based on ASTM C642 (2021) [24].

Figure 3.

(a) Slump flow test, (b) air content meter.

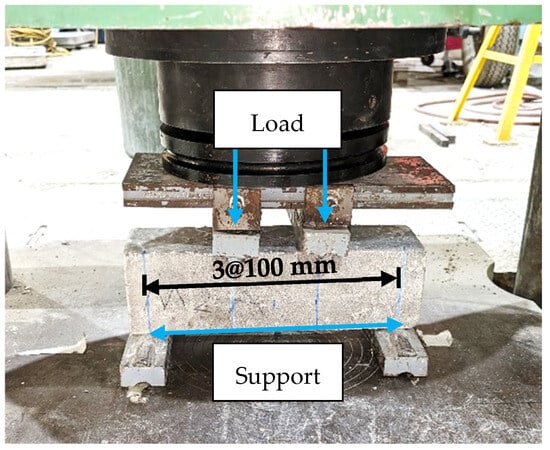

2.3.2. Mechanical Properties

A Universal Testing Machine (UTM) was used for the tensile, compressive, and flexural tests. For the tensile and compression tests, cylindrical specimens of diameter 100 mm and length 200 mm were used following ASTM C496 (2017) [25] and ASTM C39 (2021) [26], respectively. Tests were conducted after 7 days and 28 days of curing. Three cylindrical specimens were tested from each mixture, of which the averages were calculated. A displacement-controlled loading rate of 0.5 mm/s and 0.4 mm/min, respectively, for compressive and splitting tensile strength was applied by a Universal Testing Machine (UTM) over the cylinder until failure. For flexural tests, 100 × 100 × 350 mm prisms were used for third-point loading. The test method that was followed to determine the flexural strength was ASTM C78 (2022) [27]. The applied loading rate was 0.8 MPa/min. The test setup is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Flexural strength test setup.

2.3.3. Durability Properties

The rapid chloride penetration test (RCPT) following ASTM C1202 (2022) [28] and rapid chloride migration test (RCMT) following NT Build 492 (1999) [29] are performed after 28 days of curing to measure the resistance to the penetration of chloride ions. The cylinders were cut into 50 mm thick disks for these tests. Code specifications were followed to prepare the disks for the tests. Silicone gel was applied to the sides of the disks to make them watertight. After that, the samples were vacuum treated for 3 h, saturated under vacuum with room temperature water for 1 h, and then submerged for 18 h before testing.

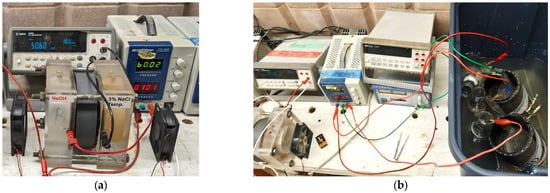

For RCPT, ASTM C1202, the standard test method for the electrical indication of the concrete’s ability to resist chloride ion penetration was followed. For RCPT, one end of the specimen was immersed in a 0.3N sodium hydroxide solution (NaOH) and the other end in a 3% sodium chloride solution (NaCl), representing the anode and cathode, respectively. A voltage of 60 V using a power supplier was passed through the specimens for 6 h and the electrical current passed was recorded and was maintained across the specimen. For RCMT, the specimens were placed inside a rubber sleeve, where the top of the disk was exposed to 300 mL of 0.3N NaOH solution. A large plastic box was used as the catholyte reservoir with 2N NaCl solution and the rubber sleeves containing the specimens were placed inside. The cathode was connected to the negative node and the anode to the positive node of the power supply. The voltage and test duration were set following the code specifications. After the test, the disks were split into two equal pieces, and the chloride ion penetration depth was measured after spraying silver nitrate solution on the surface of the split section. After about 15 min, the white silver chloride precipitation will be clearly visible. Intervals of 10 mm were marked on the specimen and penetration depth was measured from the middle excluding a 10 mm section at the ends. The test setup of RCPT and RCMT is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Test setup of (a) RCPT, (b) RCMT.

Bulk resistivity was measured using a bulk resistivity meter on three samples and their averages were taken. The sponges of the device were saturated with water, and the sample was placed in between them to take data.

The resistance of the composites to rapid freezing and thawing was also tested on molded prisms of dimensions 100 × 100 × 350 mm. For exposed specimens, the combined cyclic regime consisted of 300 F/T cycles. The F/T cycles were executed in compliance with ASTM C666 [30] procedure A, which stipulates alternately decreasing the freezing temperature from +4 to −18 °C and increasing the thawing temperature from −18 to +4 °C. The peak temperature at freezing (−18 °C) and thawing (+4 °C) was maintained for 2 h for each cycle. Reference transverse frequency was measured before starting the freezing and thawing cycles and transverse frequency readings were taken every 3436 cycles. Using the resonance frequency method on the prisms (transverse mode) in accordance with ASTM C215 [31], the relative dynamic modulus of elasticity was measured during the cyclic exposure to assess the frost resistance of the cementitious composites. The following equation was used to obtain the relative dynamic modulus in accordance with ASTM C666:

where REn is the relative dynamic modulus at n cycles of exposure (%), Fn is the fundamental transverse frequency at n cycles (kHz), and F0 is the initial fundamental transverse frequency (kHz).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Workability

The fresh workability of the NFC mixed composites using the slump flow measurement is given in Table 3. When no AEA is added, the slump flow of the mixes is in the range of 750–800 mm. These values indicate high flowability, suitable for self-consolidating applications. The high flowability, even with high binder content and low w/b ratio, can be attributed to the use of the superplasticizer. The slump flow of 0.25% NFC in M2 increases by 5% compared to M1 (800 mm). Further increments in the dosage of NFC reduces the slump flow; M3 and M4 have 5% and 6% less slump flow, respectively, compared to M1. The slight increase in slump flow at 0.25% NFC (M2) is attributed to the ability of NFC to function as a viscosity modifier, which improves paste cohesiveness and particle dispersion [32]. However, further addition of NFC (M3 and M4) causes a gradual fall in slump, due to the high surface area and high water absorption capability of NFC, which decreased the free water content in the mix and eventually hindered the flowability [7,32].

Table 3.

Slump and air content of NFC mixed composites.

The slump flow of all the mixes decreases by 20 to 25% upon the addition of AEA, although the trend is identical for the change in NFC dosage. AEA usually increases the slump flow by lowering the surface tension and creating microbubbles [33]. However, the results indicate that upon the addition of AEA, the flowability is severely compromised by the higher NFC dosage. The combined effect of the entrained air bubbles from AEA and the hydrophilicity of NFC raise the viscosity of the mix and hinder its free flow. M4-A has the lowest flowability of all, at 566 mm; a similar result is also observed by Onuaguluchi et al. (2024) [34]. The results imply that in order to maintain the desired flowability in high-performance concrete, both the NFC dosage and AEA should be carefully optimized.

3.2. Air Void

The mechanical performance and durability of cementitious composites are significantly influenced by the air void. A decreasing trend in the fresh air content is observed with the increasing dosage of NFC, as presented in Table 3. M1 with no NFC shows the highest air content of all (3.6%). With the increase in NFC dosage from 0.25% to 0.75%, M2, M3, and M4 show, respectively, 22%, 47%, and 72% decreases in air content compared to M1. The 0.75% NFC dosage in M4 results in the fresh air content of 1%, even though 6% air content was considered during the mix design. The pore interconnection as well as the formation of a denser microstructure is responsible for the drop in air content in the presence of NFC [6]. NFC also improves the internal cohesiveness of the cement matrix [4].

The incorporation of AEA into the mix causes a substantial increase in the air content. Mixtures with AEA have a relatively high air content of 8% to 14%. The highest value, 11.5%, is observed for M1-A without any NFC. However, the air content gradually decreases again as the NFC dosage increases. The results indicate that NFC fills up the void induced by AEA and promotes finer pore structures. This trend can be explained by several interacting mechanisms. The hydrophilic properties of NFC cause partial water absorption and alter the bubble dynamics, while its presence enhances the viscosity of the fresh mix, stabilizing the entrained air bubbles and decreasing their mobility. AEA also helps distribute air more evenly and lowers the surface tension. Thus, bubble coalescence, retention, and distribution are influenced by the combined action of NFC and AEA, which ultimately controls the measured air content and helps to refine the pore structure.

The hardened air void or permeable pore spaces in cylindrical samples are determined after 28 days of curing. The results depicted in Table 3, irrespective of AEA usage, exhibit a noticeable rise with the inclusion of NFC. The hardened air void is lowest in control mix M1 (16.0%), whereas it gradually increases in NFC mixed composites, reaching a peak of about 19%. When no AEA is added, M2, M3, and M4 have, respectively, 11%, 16%, and 17% increases in the air void. This phenomenon is explained by the fact that although AEA lowers the surface tension and encourages uniform bubble dispersion, NFC’s increased viscosity and water absorption stabilize air bubbles in the fresh mix. By limiting bubble movement, the thicker paste traps air throughout the hardening process and creates smaller, more evenly spaced voids. NFC increases the viscosity of the cement paste [32]. The addition of NFC in the cement matrix also increases the wettability and adhesion properties of the concrete surface [35]. As a result, the thick paste restricts the movement of air bubbles, which entraps air during the hardening process. This results in small air voids in the hardened state. According to the findings of Sadoon et al. (2024) [1], NFC decreases the total porosity and threshold pore diameter of the composites by 9% and 28%, respectively, compared to the composites without NFC, although the proportion of micro-pores had an increment of about 5%. Barnat-Hunek et al. (2019) [35] observed that 1% of NFC caused a drop in pore size from 135 nm to 28 nm and 32 nm, respectively. The findings perfectly align with the current results.

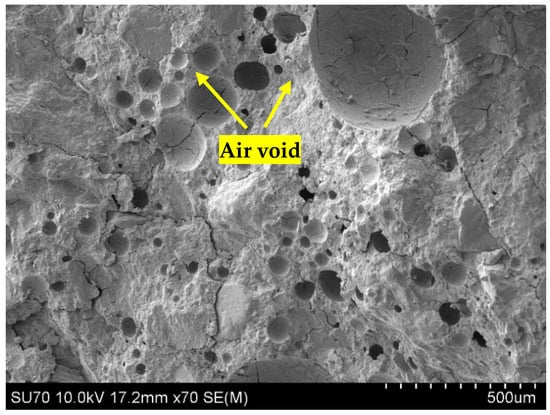

The hardened air void also increased with NFC dosage in mixes containing AEA. M1-A without NFC gives a 13% higher air void than M1. However, the difference in the air void after adding AEA in the NFC mixed composites is much less. M3-A and M4-A have hardened air voids almost similar to their non-AEA counterparts. The results indicate that NFC and AEA have a synergistic effect, where NFC stabilizes the air voids introduced by AEA. NFC has a high surface area and is hydrophilic which facilitates a water-holding capacity [7,32]. For these characteristics, although NFC reduces the fresh air content, it seals in and protects the tiny air voids during the hardening process as can be seen from Figure 6. A network of micro fibrils is created by NFC in the cement matrix, which stops smaller bubbles from combining into bigger ones.

Figure 6.

SEM image of air void in hardened M4-A composite in 500 µm scale.

3.3. Mechanical Properties

3.3.1. Compressive Strength

The compressive strength of the composites after 7 and 28 days is demonstrated in Figure 7. It is evident that the presence of NFC improves the compressive strength with a higher curing age, although the strength decreases eventually with higher percentages of NFC. After 7 days of curing, when no AEA is added, the NFC mixed composites show an 8–18% decrement in strength than the control mix M1 (59.8 MPa). When AEA is added, the compressive strength decreases by 22–36% compared to their counterparts without AEA. The hydroxyl and carboxyl groups in NFC molecules react with calcium ions which can shorten the hydration period and delay the setting time, which explains the comparatively low compressive strength of NFC mixed composites after 7 days [36].

Figure 7.

Compressive strength of different composites.

After 28 days, the compressive strength significantly increases. As reported by Sadoon et al. (2024) [1], NFC has a prolonged hardening rate, which results in lower early-age compressive strength. The improvement in compressive strength with the addition of NFC is also attributed to the internal curing mechanism of NFC, which improves the hydration of the composites [1]. The best result is found for M2 containing 0.25% NFC and no AEA after 28 days, which is 24% higher (77.9 MPa) than the control mix (62.8 MPa). M3 and M4 have, respectively, 16% and 8% lower compressive strength than M1. The agglomeration of NFC and decreased workability of the mortar mix due to the presence of a higher dosage of NFC is responsible for this decrease [4].

The mixtures with AEA have comparatively lower compressive strengths, by 20–36%, compared with mixtures without AEA. Mehta et al. (2014) [14] reported that the cementitious composite’s strength is reduced by 3–6% for every 1% of entrained air, depending on the curing conditions. When AEA is added, the 7 days compressive strength decreases by 22–26% for the NFC mixed composites, compared to their counterparts without AEA. M1-A without NFC shows the highest loss of 36% in 7-day strength (38.3 MPa) due to the addition of AEA. On the other hand, the 28-day strength of M2-A containing 0.25% NFC only reduced by 19% (63.3 MPa). The strength development from 7 days to 28 days is between 17 and 32% for NFC mixed composites. It is reported that high-volume slag can reduce the early-age compressive strength [11,12]. After AEA addition, the 7-day tests yield strengths in the range of 38–43 MPa. Therefore, the composites have good early-age strength as well in the presence of NFC. Thus, it can be identified that the use of NFC can mitigate the problem of strength development faced by incorporating a high volume of slag.

3.3.2. Splitting Tensile Strength

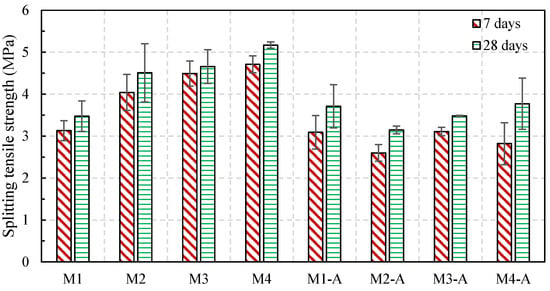

The average splitting tensile strengths of the specimens is provided by Figure 8. It can be observed that NFC increases the tensile strength unlike the compressive strength. A 0.75% dosage of NFC (M3) increased the strength by about 50% in comparison with the mixture without NFC (M1). NFC dosages of 0.25% and 0.5% (M2 and M3) also showed 30% and 34% higher splitting tensile strength, respectively, compared to M1 after 28 days. NFC acts as a nanofiber, whose bridging effect inhibits the spread of cracks at the nanoscale [3]. This enables the composites to sustain a higher tensile load. The linear increase in tensile strength with the addition of NFC can be attributed to the tensile effectiveness of the nanofibers in resisting tension coupled with the splitting strength applying tension to the largest cross-section of the cylinder. The large longitudinal cross-section allows for the NFC to contribute the maximum amount to the tensile strength of the specimen.

Figure 8.

Splitting tensile strength of different composites.

The addition of AEA results in a loss of tensile strength similar to compressive strength, although the result improves with higher dosages of NFC. While the strength of M2, M3, and M4 increased with the addition of NFC, the splitting tensile strength of M2-A, M3-A, and M4-A with both NFC and AEA are up to 16% after both 7 days and 28 days. The tensile strength of M2-A and M3-A after 28 days of curing decreased by 15% and 6%, respectively, compared to the mixtures without AEA. Only M4-A has the highest splitting tensile strength of 3.77 MPa after 28 days, which is almost similar to that of M1-A (3.71 MPa). Zeyad et al. (2023) [37] observed that AEA led to increased porosity and lower mechanical properties due to the poor matrix integrity. AEA increases voids in the composites. By acting as weak spots, these voids decrease the amount of solid cross-sectional areas that can support tensile stress. Cracks often start in the air spaces and spread out under splitting tensile stress, weakening the matrix. However, the nucleation effect of NFC helps to produce more calcium silicate hydrate (CSH) gel, which forms a denser microstructure and can improve the mechanical strength of NFC mixed composites [38].

3.3.3. Flexural Strength

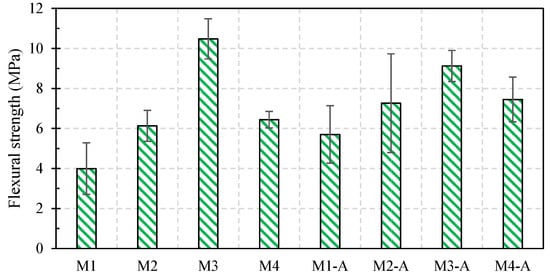

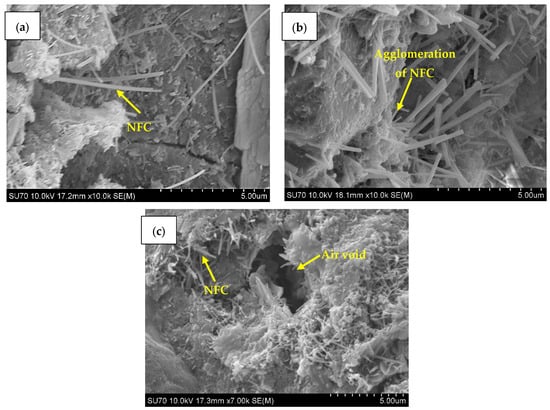

The average 28-day flexural strength of the control and nanofiber-reinforced prism specimens is depicted in Figure 9. It is evident that NFC significantly improves the flexural strength of the composites up to a certain dosage. Although compressive strength decreased at high NFC dosages due to the increased porosity and potential microcracking, tensile strength, as well as flexural strength, continued to improve because NFC acts as a crack-bridging network, enhancing stress transfer and resistance to crack propagation under bending and splitting loads, and the differences in mean strengths exceed the standard deviations, indicating that the observed trends are consistent and meaningful across replicates. The 0.25% and 0.5% NFC dosages increased the flexural strength, respectively, by 54% and 162% compared to M1 without NFC. The improvement in strength with the addition of NFC can be attributed to the improved hydration. The high surface area and hydrophilic nature of NFC promote better bond behavior within the cement matrix [7,32]. The highest flexural strength is observed for 0.5% NFC in M3 (10.48 MPa). However, a higher dosage than this can decrease the flexural strength. Although 0.75% NFC in M4 gives 61% higher flexural strength than the control composite, it is 39% less than M3. A similar trend is also observed by Onuaguluchi et al. (2014) [7]. The authors observed a 106% increase in flexural strength for up to 0.1% NFC, which started to decline for higher dosages than that. This is due to the inhomogeneous dispersion of NFC in the cement matrix from a higher dosage. When a higher dosage of NFC is incorporated, fiber agglomeration adversely affects the flexural strength. This phenomenon is evident from the SEM image in Figure 10. A more homogeneous distribution of NFC is visible in the M3 mix with 0.5% NFC. On the other hand, fiber agglomeration is clearly visible at a 5 µm scale. This results in weaker interfacial transition zones (ITZs) that are created where the cement surrounds the aggregate and the NFC. These ITZs are locations with increased local porosity and in large may contribute to the decreased flexural strengths with the incremental increases in NFC dosages.

Figure 9.

Flexural strength of different composites.

Figure 10.

SEM image of NFC mixed composite in 5 µm scale (a) M3 mix, (b) M4 mix, (c) M4-A mix.

On average, composites with AEA have slightly higher flexural strength, unlike compressive and tensile strength. M1-A has 43% higher flexural strength than M1 without AEA. Except for M3-A, the flexural strength of M2-A and M4-A is higher, respectively, 18% and 16%, than their counterparts without AEA. Here, M3-A gives 13% less flexural strength (9.13 MPa) than M3. AEA created air voids in micro-scale (Figure 10c), which serve as defects under pure compression and tension. These defects reduce the strength by concentrating the stress. However, failure under flexural stress entails a combination of compression at the top and tension at the bottom. NFC reinforces/bridges to carry the tension where the crack initiates, whereas air bubbles on the compression side have less of an effect. Thus, the bridging effect of NFC aids in withstanding a greater flexural load before failure. Air voids impede crack propagation, which forces the cracks to take a more intricated path. The failure mode of all the NFC mixed prisms is observed to be brittle (Figure 11), as NFC reinforces the composites in nano-scale unlike macrofibers [3].

Figure 11.

Failure mode of NFC mixed prism.

3.4. Durability Properties

3.4.1. Rapid Chloride Penetration/Migration

Table 4 presents the results depicted from the rapid chloride penetration test (RCPT) and rapid chloride migration test (RCMT). The charges passed through all the mixes from RCPT are between 1000 and 2000 coulombs. According to ASTM C1202 (2022) [28], all the mixes show “low” chloride ion penetrability, regardless of the dosage of NFC. The control mix M1 without NFC has the minimum charge passed of all, M1 has 1092 coulombs, and M1-A has 1077 coulombs. An increase in penetrability can be noted in the composites with NFC compared to M1 and M1-A. A 0.25% dosage of NFC increased the penetrability by 22%, and an increase of 47% and 28% was observed at 0.5% and 0.75% dosages of NFC, respectively. The chloride ion penetrability is higher even though NFC serves as a filler to improve the composite’s mechanical properties. Kilic et al. (2024) [4] detected that the aggregation of NFC creates voids in the cement matrix, which results in a porous network. According to Ahmed et al. (2025) [3], the CSH structure is less compacted by NFC, which causes the matrix to have interconnected microcracks. These microcracks serve as a channel for chloride ions to penetrate. A similar result is also found by Aziz et al. (2021) [6] and Sadoon et al. (2024) [1], where 0.75% NFC showed the highest penetration. However, in this study, the highest charge is passed through M3 with 0.5% NFC. The presence of high-volume slag (40%) can be responsible for this because the voids created by NFC in M4 are filled up by the slag. Although NFC increased the measured charge passed relative to the control, all mixes remained within the low penetrability classification according to ASTM C1202, indicating that the overall durability remains excellent for practical applications.

Table 4.

Durability properties of NFC mixed composites after 28 days.

As expected, the presence of AEA slightly increased the charge passed in RCPT as well as the chloride ion penetration, attributed to the air voids introduced by AEA (Figure 6). The charge passed through M2-A, M3-A, and M4-A is, respectively, 2%, 8%, and 9% higher than their counterparts without AEA. The air bubbles in the samples allow easier penetration of ions inside the matrix. Nonetheless, all composites had low penetrability, and therefore they have good durability and are suitable for outdoor exposure. The composites have strong durability properties due to the low w/b ratio and the high binder content. These factors along with the effects of the NFC improved the matrix maturity of the composites.

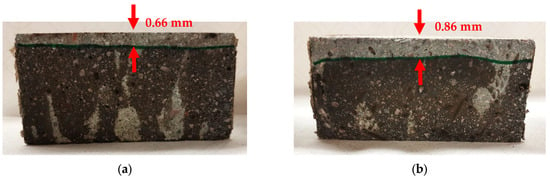

The average migration coefficient represented in 10−12 m2/s in Table 4 depicts the durability of the composites based on the RCMT analysis. Similarly to the RCPT, the composites with air had higher migration coefficients and the incorporation of NFC does not have a significant effect on the migration coefficients for the similar reason that the charge passed was higher. The migration coefficients of the composites range between 0.1 and 0.2 × 10−12 m2/s. M3-A has the highest migration coefficient of 0.18 × 10−12 m2/s, whereas M4 has the lowest at 0.11 × 10−12 m2/s due to the presence of slag. The higher resistance to chloride migration of the composites without air admixture is due to their lower porosity. The average chloride ion penetration depth of the samples ranges between 0.66 and 0.86 mm. Similarly to the charge passed and the migration coefficient, the penetration depth is also the highest for the M2-A mix as shown in Figure 12. The M4 mix gives the lowest penetration depth owing to the compact matrix resulting from NFC and slag.

Figure 12.

Depth of chloride ion penetration represented by whitish precipitate from RCMT (a) M4 mix, (b) M2-A mix.

Although NFC incorporation is commonly associated with microstructural refinement, the RCPT and RCMT results demonstrated a higher charge passed for NFC-modified composites. This behavior may be attributed to NFC–slag interactions that influence pore connectivity, as well as the internal curing effect of NFC, which enhances moisture retention and ionic conductivity during the test. Furthermore, matrix densification may be partially countered by the possible creation of tiny microcracks as a result of NFC-induced shrinking, increasing the observed permeability.

3.4.2. Bulk Resistivity

When assessing the longevity and ion transport resistance of cementitious composites, bulk electrical resistivity is an essential metric. A denser microstructure and reduced permeability are indicated by higher bulk resistivity, which enhances the material’s resistance to corrosion and chloride intrusion. The bulk resistivity of the composites, along with the electrical resistivity after 28 days, is depicted in Table 4. From the result, it is observed that the inclusion of NFC can progressively lower the resistivity of the composites, when no AEA is added. The control mix M1 has the highest resistivity of 50.3 kΩ-cm and M4 has the lowest of 31.3 kΩ-cm. A 0.25%, 0.5%, and 0.75% NFC dosage can reduce the resistivity by 29%, 36%, and 38%, respectively, compared to the control mix without NFC. An identical trend is observed in the case of electrical resistivity as well. M1 has the highest electrical resistivity of 6.69 kΩ. All the NFC mixed composites are in the range of 4 to 5 kΩ. The results suggest that high NFC dosages may cause poor dispersion or aggregation, which could raise ionic conductivity [4,7]. Additionally, because of its hydrophilic nature, NFC can retain more moisture within, which aids in ion transport.

The bulk resistivity increases with the addition of AEA. The resistivity of M1-A is 36% less than M1. However, the presence of NFC with AEA in the composites gives better resistivity. For instance, the resistivity of M2-A, M3-A, and M4-A improved by 10%, 34%, and 32%, respectively, compared to the same composites without air admixture. The air voids introduced by the AEA disrupt continuous pore channels, thus reducing bulk conductivity. This is corroborated by the air content test discussed in Section 3.2, which decreased from 11.5% (M1-A) to 8.1% (M4-A) as a result of the gradual suppression of the impact of AEA, which greatly increased air entrainment. This suggests that NFC may help stabilize the pore structure and limit the formation of large, entrained voids, thus enhancing resistivity even in the presence of AEA. The improved microstructure due to NFC’s filling and water retention abilities may further contribute to this positive durability outcome. However, AEA reduced resistivity in the control mix M1-A with no NFC by 36% compared to M1, possibly due to the decreased interaction between hydration products and a potentially lower matrix density.

Although NFC enhances mechanical properties through crack-bridging and microstructural refinement, the bulk resistivity reduces. According to the SEM images in Figure 10, NFC agglomerates, with more uniform dispersion enhancing the tensile and flexural performance and larger clusters decreasing the compressive strength. The apparent contradiction results from NFC’s simultaneous local matrix densification, moisture retention, and interaction with slag, which enhances pore connectivity and establishes continuous ionic pathways; higher conductivity may also be caused by fine microcracks from shrinkage or fiber–matrix mismatch. These results demonstrate that different microstructural processes in NFC-modified composites control mechanical strength and ionic resistance.

3.4.3. Resistance Against Freeze–Thaw

The relative dynamic modulus of elasticity (REn) after 300 F/T cycles for each composite is listed in Table 4. The REn of the cementitious composite produced without NFC demonstrated strong frost resistance, completing 300 freeze–thaw cycles while maintaining an REn value above the ASTM C666 threshold of 60%. This may be attributed to the incorporation of a high volume of slag which refined the pore structure of the matrix, which accordingly reduced the possibility of critical saturation which eventually led to a frost damage [39,40]. In addition, the composites with NFC, irrespective of the dosage of NFC or the incorporation of AEA, showed very low penetrability (less than 2.5% absorption) and higher REn resulting in excellent resistance to frost damage, due to the microstructural densification, suggesting their suitability for outdoor exposures in cold regions [1]. For instance, in comparison to the control mix without air (M1), the incorporation of NFC with a dosage of 0.25, 0.5, and 0.75% showed an improvement in the dynamic modulus of elasticity by 10%, 6%, and 4%, respectively. Thus, the frost resistance tests showed a high efficiency of nanocellulose in concrete hydrophilization, which directly influences the durability of concrete exposed to water and frost [35]. The observed enhancement in freeze–thaw resistance can be allied with the refined pore structure seen in the SEM images (Figure 10), where NFC incorporation modified pore connectivity and diminished weak spots, thereby limiting water ingress and damage during cyclic freezing and thawing. On the other hand, the outstanding performance for all specimens with air entrainment agent (M1-A–M4-A) compared to their counterpart specimens without air (M1–M4) could be linked to the higher air content (Table 3). As such, the presence of air void systems contributes to the microstructural discontinuity within the matrix, which helps resist frost damage by providing space for the expansion of freezing water and reducing internal stresses. Additionally, the high binder content (≥700 kg/m3) and low water/binder ratio (0.30) further contribute to the composites’ resistance to fluid ingress and freezing-related deterioration, indirectly relating to the effectiveness of the entrained air content in improving durability [2].

4. Conclusions

This work investigates the performance of nano-modified cementitious composites. Several parameters were covered including the NFC, the dosage of NFC, and the effect of the air entrainment agent. Fresh, mechanical, and durability properties were also monitored. In addition, microstructural analysis was also conducted. Thus, the following conclusions can be drawn:

- The inclusion of nanocellulose fiber (NFC) influenced the workability of the mixes significantly. A small dosage of 0.25% NFC (M2) increased slump flow by 5% (to 830 mm), indicating improved viscosity and particle dispersion. However, higher NFC dosages (≥0.5%) reduced flowability by 5–6% due to water absorption and surface area effects, suggesting that 0.25% NFC offers an optimal balance between cohesion and flow.

- The fresh air content dropped from 3.6% (M1) to 1.0% (M4) as NFC dosage increased, showing up to a 72% reduction in entrapped air and improved matrix density. In contrast, air-entrained mixes (M-A series) exhibited 8–12% air content, but NFC addition moderated this rise, stabilizing bubble distribution and promoting finer pores, which enhances the homogeneity and long-term stability.

- After 28 days, the optimum dosage of 0.25% NFC achieved a 24% higher compressive strength (77.9 MPa) than the control (62.8 MPa), attributed to improved hydration and internal curing. Excessive NFC (≥0.5%) caused up to 16% strength loss due to fiber agglomeration and reduced workability. Incorporating AEA lowered the compressive strength by 20–36%, but the combined use of AEA + 0.25% NFC mitigated strength loss to below 19%, confirming the synergistic effects at low NFC levels.

- NFC substantially enhanced the tensile and flexural capacities. Splitting tensile strength increased by up to 50% at 0.75% NFC, while flexural strength improved by 162% at 0.5% NFC (10.48 MPa). These gains result from NFC’s crack-bridging and nano-reinforcing effects which improve load transfer and micro-crack control. Excessive NFC reduced the flexural strength due to fiber clustering and weaker ITZ formation.

- All composites demonstrated low chloride ion penetrability (1000–2000 coulombs) as per ASTM C1202, confirming good durability. The highest penetration occurred at 0.5% NFC, with a 47% increase over the control, yet still within “low” permeability. Bulk resistivity ranged between 31 and 50 kΩ-cm, where the combined NFC + AEA mixes (e.g., M4-A) achieved a 32% improvement over their non-AEA counterparts, indicating denser pore structures and superior resistance to ionic transport.

- The optimized NFC dosage (≈0.25–0.5%) yields self-consolidating, high-strength, and durable concrete suitable for structural applications exposed to aggressive or freeze–thaw environments. The findings suggest that NFC can be used to enhance the tensile and flexural performance in concrete structures, such as pavements, overlays, or precast elements, where improved crack resistance is critical. This study is limited by the potential variability in NFC dispersion, the absence of long-term durability data, and the focus on short-term laboratory conditions. Future work should explore hybrid nanofiber systems, advanced dispersion methods, and long-term monitoring to further harness NFC’s multifunctional potential in sustainable construction materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.W.; Methodology, S.W. and A.B.; Validation, M.E.-G.; Formal analysis, T.A.; Investigation, T.A.; Resources, A.B.; Data curation, O.A.; Writing—original draft, T.A. and S.W.; Writing—review and editing, M.E.-G., O.A. and A.B.; Supervision, A.E. and A.B.; Project administration, A.B.; Funding acquisition, A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the NSERC (Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada) and United Arab Emirates University (12N265).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sadoon, A.; Hosny, O.M.; Bassuoni, M.T.; Minhas, G.; Ghazy, A. Use of cellulose nanomaterials in cementitious composites reinforced with basalt/polymer pellets for repair of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosny, O.M.; Yasien, A.M.; Bassuoni, M.T.; Gourlay, K.; Ghazy, A. Cementitious Composites with Cellulose Nanomaterials and Basalt Fiber Pellets: Experimental and Statistical Modeling. Fibers 2024, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.; Bediwy, A.; Islam, M.J. Durable and sustainable nano-modified basalt fiber-reinforced composites for elevated temperature applications. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 108, 112865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilic, U.; Soliman, N.; Omran, A.; Ozbulut, O.E. Effects of cellulose nanofibrils on rheological and mechanical properties of 3D printable cement composites. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2024, 152, 105617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolour, H.H.; Ahmed, M.; Alyaseen, E.; Landis, E.N. An Investigation on the Effects of Cellulose Nanofibrils on the Performance of Cement Paste and Concrete. Adv. Civ. Eng. Mater. 2018, 7, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, M.A.; Zubair, M.; Saleem, M. Development and testing of cellulose nanocrystal-based concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2021, 15, e00761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onuaguluchi, O.; Panesar, D.K.; Sain, M. Properties of nanofibre reinforced cement composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 63, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Feky, M.S.; El-Tair, A.M.; Kohail, M.; Serag, M.I. Nano-Fibrillated Cellulose as a Green Alternative to Carbon Nanotubes in Nano Reinforced Cement Composites. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Explor. Eng. 2019, 8, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.; Shaikh, F.U.A. Long-term strength and durability performance of eco-friendly concrete with supplementary cementitious materials. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2023, 8, 255. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, T.; Bediwy, A.; Azzam, A.; Elhadary, R.; El-Salakawy, E.; Bassuoni, M.T. Utilization of Novel Basalt Fiber Pellets from Micro- to Macro-Scale, and from Basic to Applied Fields: A Review on Recent Contributions. Fibers 2024, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosan, A.; Shaikh, F.U.A. Compressive strength development and durability properties of high volume slag and slag-fly ash blended concretes containing nano-CaCO3. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 10, 1310–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Liu, S.; Yu, L.; Xu, L. A Comprehensive Study on the Hardening Features and Performance of Self-Compacting Concrete with High-Volume Fly Ash and Slag. Materials 2021, 14, 4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jozić, D.; Ljubičić, B.; Petrović, A.; Čović, A.; Juradin, S. The Influence of GGBFS as an Additive Replacement on the Kinetics of Cement Hydration and the Mechanical Properties of Cement Mortars. Buildings 2023, 13, 1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P.K.; Monteiro, P.J.M. Concrete: Microstructure, Properties, and Materials, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Long, G.; Li, Y.; Ma, C.; Xie, Y.; Shi, Y. Hydration kinetics of cement incorporating different nanoparticles at elevated temperatures. Thermochim. Acta 2018, 664, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak-Michta, A. Salt Scaling Resistance of Variable w/c Ratio Air-Entrained Concretes Modified with Polycarboxylates as a Proper Consequence of Air Void System. Materials 2022, 15, 5839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CSA A23.1; Concrete Materials and Methods of Concrete Construction. Canadian Standards Association: Mississauga, ON, Canada, 2019.

- CSA A3001; Cementitious Materials for Use in Concrete. Canadian Standards Association: Mississauga, ON, Canada, 2018.

- ASTM C136; Standard Test Method for Sieve Analysis of Fine and Coarse Aggregates. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- ASTM C128; Standard Test Method for Relative Density (Specific Gravity) and Absorption of Fine Aggregate. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- ASTM C494; Standard Specification for Chemical Admixtures for Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- ASTM C1611; Standard Test Method for Slump Flow of Self-Consolidating Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- ASTM C231; Standard Test Method for Air Content of Freshly Mixed Concrete by the Pressure Method. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- ASTM C642; Standard Test Method for Density, Absorption, and Voids in Hardened Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- ASTM C496; Standard Test Method for Splitting Tensile Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- ASTM C39; Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- ASTM C78; Standard Test Method for Flexural Strength of Concrete (Using Simple Beam with Third-Point Loading). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- ASTM C1202; Standard Test Method for Electrical Indication of Concrete’s Ability to Resist Chloride Ion Penetration. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- NT Build 492; Chloride Migration Coefficient from Non-Steady State Migration Experiments. Nordtest: Espoo, Finland, 1999.

- ASTM C666; Standard Test Method for Resistance of Concrete to Rapid Freezing and Thawing. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- ASTM C215; Standard Test Method for Fundamental Transverse, Longitudinal, and Torsional Resonant Frequencies of Concrete Specimens. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- Hisseine, O.A.; Basic, N.; Omran, A.F.; Tagnit-Hamou, A. Feasibility of using cellulose filaments as a viscosity modifying agent in self-consolidating concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2018, 94, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, H.A.; Yuan, Q.; Zuo, S. Air entrainment in fresh concrete and its effects on hardened concrete-a review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 274, 121835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onuaguluchi, O.; Banthia, N. Entrained air and freeze-thaw durability of concrete incorporating nano-fibrillated cellulose (NFC). Cem. Concr. Compos. 2024, 150, 105582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnat-Hunek, D.; Szymańska-Chargot, M.; Jarosz-Hadam, M.; Łagód, G. Effect of cellulose nanofibrils and nanocrystals on physical properties of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 223, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Su, M.; Chen, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Dai, H. Natural Cellulose Nanofibers as Sustainable Enhancers in Construction Cement. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0168422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeyad, A.M.; Amin, M.; Agwa, I.S. Effect of air entraining and pumice on properties of ultra-high performance lightweight concrete. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2023, 24, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, S.C.; Meng, D.; Guo, Q.; Liu, Y. Effect of interface properties between functionalized cellulose nanocrystals and tricalcium silicate on the early hydration mechanism of cement. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 698, 134552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bediwy, A.; Bassuoni, M.T. Resistivity, penetrability and porosity of concrete: A tripartite relationship. J. Test. Eval. 2018, 46, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bediwy, A.G.; Bassuoni, M.T.; El-Salakawy, E.F. Residual Mechanical Properties of BPRCC under Cyclic Environmental Conditions. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2021, 33, 04021290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.