Abstract

The rapid expansion of artificial intelligence (AI) and digitalization in contemporary education has intensified global debates on sustainable education, frequently framed around efficiency, personalization, and technological innovation. At the same time, these developments have accelerated processes of technologization and commodification, raising concerns about the erosion of educational values and human-centered purposes. This tension calls for a critical reassessment of what sustainability should mean in AI-mediated educational contexts. The objective of this study is to examine under what conditions AI contributes to sustainable education as a value-based and human-centered project, and under what conditions it undermines it. Methodologically, the article adopts a qualitative, value-critical analysis of contemporary scholarly literature and policy-oriented debates, employing the distinction between sustainable education, sustainability in education, and education for sustainable development as a heuristic entry point within a broader theoretical dialogue. The analysis demonstrates that AI does not exert a uniform or inherently progressive influence on education. While AI can enhance access, personalization, and instructional support in ethically grounded and well-governed contexts, it may also intensify educational inequalities, reinforce the commodification of knowledge, weaken academic integrity, and marginalize the formative and human dimensions of education under market-driven and weakly regulated conditions. These dynamics are particularly visible in culturally and religiously grounded educational contexts, where AI reshapes epistemic authority and educational meaning. The study concludes that achieving sustainable education in the digital age depends not on AI adoption per se, but on subordinating AI and digitalization to coherent normative, ethical, and governance frameworks that prioritize educational purpose, social justice, and human dignity.

1. Introduction

The rapid expansion of artificial intelligence (AI) and digitalization has become one of the most influential transformations shaping contemporary education worldwide. Digital technologies increasingly mediate teaching, learning, assessment, and institutional governance, while AI-driven systems are being integrated into classrooms, online platforms, and educational management structures. Within global policy agendas—particularly those linked to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals—education is widely framed as a key driver of sustainable development, with Sustainable Development Goal 4 emphasizing inclusive, equitable, and quality education for all [1,2,3,4,5]. In this context, AI is often presented as a technological catalyst capable of modernizing education systems and aligning them with sustainability objectives [2,6].

Despite this optimistic framing, the growing reliance on AI and digitalization raises fundamental questions about what “sustainability” should mean in educational contexts. Technological innovation is frequently equated with progress, efficiency, and improvement, yet such assumptions risk obscuring the normative and human dimensions of education [7,8]. Education is not merely a technical system to be optimized, but a value-laden social institution concerned with human development, equity, and ethical responsibility. As AI-driven technologies increasingly shape educational practices and policies, a central research problem emerges: whether AI adoption genuinely supports sustainable education as a value-based and human-centered project, or whether it accelerates processes of technologization and commodification under market-driven logics [9,10,11,12].

A useful entry point for conceptual clarification in this debate is offered by Alam, who distinguishes analytically between sustainable education, sustainability in education, and education for sustainable development [13,14]. Whereas sustainability in education often emphasizes institutional durability, efficiency, and system continuity, sustainable education is framed as a value-based and human-centered project oriented toward social justice, equity, and long-term ethical aims. Education for sustainable development, by contrast, typically focuses on curricular and pedagogical alignment with sustainability-related goals. Alam argues that failing to maintain these distinctions has generated conceptual ambiguity in educational research and policy, allowing technologization to be treated as a proxy for sustainability rather than as a means that must itself be critically evaluated [13,14]. At the same time, concerns about instrumentalism and the reduction of education to measurable outputs are also central to broader educational theory, which warns that measurement-driven reform can displace democratic, ethical, and formative purposes [7,8].

Within the existing research field, a substantial body of literature highlights the enabling potential of AI in education. Empirical studies and systematic reviews suggest that AI-powered learning systems can enhance personalization, adaptive feedback, learner engagement, and institutional efficiency when implemented under favorable conditions [1,15,16,17]. From this perspective, AI is frequently presented as a tool capable of improving educational quality and supporting sustainability goals, particularly in well-resourced contexts with strong governance structures [2,15,18]. These studies often emphasize AI’s capacity to optimize learning processes, reduce administrative burdens, and expand access to educational opportunities [19,20].

In contrast, a growing body of critical scholarship challenges the assumption that AI-driven education is inherently sustainable. Analyses of digital transformation and internationalization in higher education demonstrate how technological expansion is often embedded within market-oriented governance frameworks that prioritize competitiveness, efficiency, and profitability [9,10,12,14]. From this perspective, AI may reinforce the commodification of education by transforming learning processes, institutional practices, and student data into economic assets [11]. This line of research underscores a fundamental controversy: whether AI functions as an instrument for educational empowerment or as a mechanism that sustains market-driven models at the expense of educational values, relational pedagogy, and meaningful learning [7,14,21].

Educational equity and ethics constitute central points of contention in debates on AI and sustainable education. Research indicates that students from low-income, rural, and marginalized backgrounds often benefit less from AI-based educational technologies due to disparities in digital infrastructure, access to devices, and institutional capacity [16,22,23,24]. Rather than functioning as equalizers, AI systems may reproduce or intensify existing inequalities [18,25]. Ethical concerns further complicate this landscape, including issues related to data privacy, surveillance, algorithmic bias, transparency, and academic integrity [19,20,26,27,28,29,30]. These challenges raise serious questions about whether education mediated by AI can remain aligned with the ethical foundations of sustainability.

The tensions surrounding AI and sustainable education become particularly visible in culturally and religiously grounded educational contexts, where education is closely linked to value formation, epistemic authority, and moral development. Studies in Islamic and value-based educational settings suggest that AI integration may commodify knowledge, weaken traditional forms of scholarly authority, and reshape the meaning and purpose of education itself [3,28,31,32]. These contexts reveal that sustainability cannot be assessed solely through technical performance indicators, but must be evaluated in relation to cultural coherence, ethical commitments, and the human purposes of learning. Such perspectives remain underrepresented in mainstream AI-in-education research, despite their analytical significance.

It should be clarified at the outset that references to culturally and religiously grounded educational contexts in this study do not aim to introduce exceptional or context-bound cases. Rather, such contexts are analytically employed as sensitivity amplifiers, in which questions of educational purpose, epistemic authority, moral formation, and governance are articulated with greater normative clarity. By examining AI-mediated education in settings characterized by high value density, the study seeks to render visible conditional mechanisms that may remain less explicit in more technocratically framed educational environments.

To avoid treating such contexts as analytically exceptional or marginal, this study approaches culturally and religiously grounded educational settings as illustrative cases within a broader conditional framework. These contexts are not introduced as separate empirical domains, but as normatively dense environments in which tensions related to educational purpose, epistemic authority, governance, and commodification become more explicit. In this sense, references to Islamic and value-based educational contexts function as analytical amplifiers that help clarify the boundary conditions under which AI aligns with—or undermines—sustainable education as a value-based project.

Against this background, the present study examines sustainable education in the age of artificial intelligence and digitalization through a value-critical analytical approach that uses Alam’s distinctions as a heuristic entry point and places them in dialogue with human-centered educational theory, critical educational technology scholarship, and AI governance and policy frameworks [3,4,5,7,8,9,10,11,13,14,21,33,34,35]. The main aim is to assess whether—and under what conditions—AI can support sustainable education as a human-centered and value-based project rather than reducing education to a technologically optimized and commodified service. Accordingly, this study addresses the following research question:

Under what conditions does artificial intelligence contribute to sustainable education as a value-based and human-centered project, and under what conditions does it undermine it?

It is important to clarify that this study does not seek to provide a systematic literature review, bibliometric analysis, or empirical evaluation of specific AI applications in educational settings. Instead, it adopts a qualitative, conceptual, and value-critical analytical approach aimed at examining the normative assumptions, ethical tensions, and governance conditions that shape contemporary debates on AI, digitalization, and sustainable education. The focus of the analysis is therefore interpretive and theoretical rather than empirical or intervention-based.

This article is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews the relevant literature and theoretical background on sustainable education and AI-driven digitalization. Section 3 outlines the conceptual framework and analytical approach guiding the study. Section 4 explains the research design and analytical procedure. Section 5 presents the main analytical results, and Section 6 discusses their theoretical and policy implications. The article concludes by summarizing the findings and outlining directions for future research.

2. Related Literature and Theoretical Background

2.1. Conceptualizing Sustainable Education in an Era of Technologization

Recent scholarship increasingly emphasizes the importance of conceptually differentiating between sustainable education, sustainability in education, and education for sustainable development, particularly in the context of accelerating digitalization and the growing integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into educational systems. One influential and systematic articulation of these distinctions is offered by Alam [13,14], who argues that sustainable education cannot be reduced to institutional efficiency, technological optimization, or market-oriented performance indicators. Instead, it should be understood as a value-based and human-centered educational orientation concerned with long-term intellectual, ethical, and social flourishing.

At the same time, these distinctions resonate with, and are reinforced by, broader strands of educational theory and critical pedagogy that question the dominance of instrumental rationality in contemporary education. Human-centered educational theorists, most notably Biesta, have similarly criticized the reduction of education to measurable outputs, skills acquisition, and efficiency-driven reform, emphasizing instead education’s formative, ethical, and democratic purposes [8]. From this perspective, sustainability is not achieved through optimization alone, but through sustained attention to educational meaning, subject formation, and social responsibility.

Within this broader theoretical landscape, AI and digital technologies are not inherently incompatible with sustainable education. Rather, their educational significance depends on how they are embedded within ethical, social, and pedagogical frameworks. Alam [13] cautions that processes of technologization often generate conceptual slippage, whereby sustainability is conflated with innovation, scalability, or international competitiveness. Similar concerns are articulated in critical educational technology scholarship, which warns that technological adoption may obscure normative educational aims if driven primarily by managerial or market logics [7,8]. Together, these perspectives provide a foundational lens for evaluating AI-driven educational reforms in relation to sustainable education understood as a normative project [3,6].

2.2. Artificial Intelligence and Sustainability in Education: Enabling Potentials

A substantial body of literature highlights the potential of AI to support sustainability-related goals in education, particularly with respect to access, personalization, and learning efficiency. Numerous studies associate AI-driven educational technologies with improvements in adaptive learning, real-time feedback, and data-informed curriculum design, often aligning these developments with the objectives of SDG 4 (Quality Education) [1,2,3,4,15,22].

Empirical, systematic, and bibliometric analyses suggest that AI-based platforms can enhance learner engagement, facilitate self-directed learning, and accommodate diverse educational needs, especially in higher education contexts [2,16,17]. In technologically advanced and well-resourced settings, AI adoption has been linked to improved academic performance, reduced learning anxiety, and enhanced communication skills [18,19]. These findings underpin an optimistic narrative in which AI functions as a catalyst for innovation and educational sustainability, a view prominently reflected in international policy discourse [4,5,6].

However, even within this enabling literature, scholars consistently emphasize that such outcomes are highly context-dependent. Positive effects are contingent upon adequate infrastructure, institutional capacity, teacher training, and pedagogical integration [15,20,25]. This conditionality challenges technologically deterministic assumptions that AI adoption alone guarantees sustainable educational outcomes and underscores the importance of governance, regulation, and ethical oversight [5,36].

2.3. Critical Perspectives: Commodification, Market Logic, and Educational Governance

Alongside optimistic accounts, a growing critical literature interrogates the structural and political-economic implications of AI integration in education, particularly its role in reinforcing market logics and the commodification of knowledge. Alam [14] situates these developments within broader processes of internationalization and digital transformation, arguing that education is increasingly treated as an economic commodity governed by efficiency, scalability, and competitive performance.

This concern is echoed and extended in critical analyses of platform capitalism and datafication in education. Scholars such as Williamson highlight how AI-driven platforms reconfigure educational governance by transforming student data into strategic and commercial assets, thereby reshaping institutional accountability and epistemic authority [11,35]. From this perspective, AI functions not as a neutral tool but as a socio-technical system embedded within corporate interests, policy networks, and governance asymmetries [12,37,38].

Without robust regulatory and ethical frameworks, AI deployment risks subordinating educational aims to economic imperatives, exacerbating power imbalances, and undermining the normative foundations of sustainable education [9,10,39]. These critiques complement Alam’s conceptual distinctions by situating sustainability debates within concrete structures of governance, marketization, and political economy.

2.4. Ethical Challenges and Educational Equity

Ethical concerns constitute one of the most prominent themes in the literature on AI in education. Issues related to data privacy, algorithmic bias, transparency, accountability, and academic integrity recur across diverse institutional and geographical contexts [18,23,27,28,29,36,40]. Numerous studies demonstrate that AI systems may reproduce or amplify existing social inequalities through biased datasets, opaque decision-making processes, and uneven access to digital resources [17,25].

The digital divide emerges as a critical structural barrier to equitable AI adoption. Empirical research indicates that learners from low-income, rural, or marginalized backgrounds often experience reduced access to AI-based educational technologies due to infrastructural limitations and insufficient digital literacy [19,22,24]. These disparities suggest that AI may exacerbate educational inequality unless equity-oriented design principles and governance mechanisms are deliberately embedded in educational policy and practice [3,25,34].

Academic integrity represents a further ethical tension. The proliferation of generative AI tools has raised concerns regarding plagiarism, authorship, and the erosion of critical thinking skills [3,18,29]. While AI can support learning processes, unregulated or instrumental use risks transforming education into a transactional activity focused on outputs rather than intellectual and moral formation, echoing broader critiques of measurement-driven education [8,21].

2.5. Cultural and Value-Based Dimensions of AI in Education

An increasingly salient yet underexplored strand of the literature examines the interaction between AI and culturally or religiously grounded educational contexts. Studies focusing on Islamic and other value-based educational traditions highlight how AI challenges established epistemic authorities, pedagogical relationships, and the moral meaning of knowledge [28,31,32].

In such contexts, AI functions not merely as a technological innovation but as an epistemological intervention that reshapes how knowledge is produced, transmitted, and legitimized. Concerns regarding the commodification of sacred knowledge, the displacement of teacher authority, and tensions between efficiency-driven AI systems and contemplative educational traditions underscore the need for context-sensitive and value-critical approaches to AI integration [3,6]. Despite their analytical significance, these perspectives remain marginal within mainstream AI-in-education research.

From an analytical standpoint, such value-based educational contexts are particularly relevant because they foreground dimensions that remain implicit in many mainstream discussions of AI in education—namely educational purpose, moral responsibility, epistemic legitimacy, and governance of knowledge. As such, they align directly with the analytical dimensions developed in this study and provide a theoretically grounded basis for examining how AI-mediated education interacts with sustainability under conditions of heightened normative sensitivity.

2.6. Synthesis and Research Gap

Synthesizing the existing literature reveals a persistent duality: AI is simultaneously framed as a tool for enhancing educational sustainability and as a mechanism that may undermine it through commodification, inequality, and ethical erosion. While a substantial body of research has examined AI’s technical applications and short-term educational outcomes [1,2,15,16,17,19,20,22], considerably fewer studies have addressed sustainable education as a normative, value-based project in the age of AI [7,8,13,14].

Moreover, there remains a lack of integrative frameworks capable of reconciling AI-driven digitalization with ethical values, social justice, and human dignity across diverse educational contexts [40,41]. Situated within this gap, the present study advances a value-critical analysis of sustainable education that places Alam’s conceptual distinctions in dialogue with human-centered educational theory, critical educational technology scholarship, and international normative policy frameworks. In doing so, it seeks to contribute a theoretically plural and non-reductive perspective on sustainable education in the age of artificial intelligence and digitalization.

In addition to conceptual debates, recent empirical studies provide context-sensitive evidence on how AI adoption interacts with educational equity, academic integrity, and governance capacity across diverse settings. While this article does not aggregate empirical findings as a systematic review, it draws on relevant empirical scholarship to inform and contextualize the analytical framework and key findings developed in this study.

3. Conceptual Framework and Analytical Approach

3.1. Conceptual Foundations of the Study

This study adopts a value-critical conceptual framework to examine sustainable education in the age of artificial intelligence (AI) and digitalization. Rather than presupposing a single theoretical model, the framework is grounded in a dialogical engagement with complementary perspectives drawn from educational theory, ethics of education, and critical educational technology research. Within this plural theoretical landscape, the analytical distinctions proposed by Alam between sustainable education, sustainability in education, and education for sustainable development are employed as a heuristic and comparative reference, rather than as a self-validating or exhaustive framework [13,14]. These distinctions are analytically useful insofar as they illuminate recurring conceptual ambiguities in contemporary educational discourse, particularly the tendency to conflate technological efficiency, institutional resilience, and policy compliance with educational sustainability.

From a comparative perspective, sustainability in education is commonly associated with system-oriented approaches that prioritize institutional continuity, efficiency, and adaptability under conditions of technological and economic change. Such orientations resonate with managerial and policy-driven models of educational reform, yet have been widely criticized for reducing education to measurable outputs and functional performance. Education for sustainable development, by contrast, is typically framed around curricular and pedagogical strategies aimed at fostering awareness of environmental, social, and developmental goals, often emphasizing competencies and learning outcomes aligned with global sustainability agendas. In contrast to both orientations, sustainable education represents a more demanding normative position that situates education as a value-based and human-centered social practice oriented toward long-term intellectual, ethical, and social flourishing.

This normative understanding intersects with, and is reinforced by, broader critiques of instrumentalism and measurement-driven educational reform articulated in human-centered educational theory and critical pedagogy. Scholars such as Biesta have emphasized that education cannot be reduced to efficiency, skills acquisition, or performance indicators without undermining its ethical, democratic, and formative purposes. Similarly, critical educational technology scholarship, particularly the work of Selwyn, challenges techno-solutionist narratives and highlights the social, political, and ideological limits of AI-driven educational innovation. These perspectives converge with Alam’s critique of system-centered sustainability, while extending it by foregrounding lived educational practices, power relations, and the normative implications of technological adoption.

In addition, analyses of datafication and platform governance in education, most notably advanced by Williamson, further complicate sustainability-oriented frameworks by exposing how AI-driven infrastructures reshape educational governance, epistemic authority, and policy decision-making. From this viewpoint, sustainability claims are not merely conceptual distinctions, but are operationalized through data regimes, platform economies, and regulatory arrangements that may entrench commodification and asymmetries of power. Complementing these theoretical critiques, normative policy frameworks developed by international organizations such as UNESCO and the OECD articulate principles of ethical AI, equity, and human-centered digital transformation. While these frameworks share a concern for values and long-term educational goals, they differ in their pragmatic orientation toward governance guidelines, risk mitigation, and institutional implementation.

On this basis, the study adopts sustainable education as its primary analytical lens, while explicitly situating it in dialogue with these wider strands of educational and edtech scholarship. This positioning enables a critical evaluation of AI not merely in terms of functional performance, innovation capacity, or scalability, but in relation to fundamental educational values such as equity, human dignity, epistemic integrity, and social responsibility. By treating conceptual distinctions as analytical tools rather than presupposed truths, the framework avoids circular reasoning and remains open to competing interpretations of sustainability, educational purpose, and governance in AI-mediated education.

3.2. Artificial Intelligence as a Socio-Technical and Normative System

Rather than treating AI as a neutral technological tool, this study conceptualizes AI as a socio-technical system embedded within specific economic, institutional, and cultural contexts. AI-driven educational technologies shape not only instructional practices, but also governance structures, assessment regimes, and forms of epistemic authority. As Alam notes, technological systems introduced within market-driven and internationalized educational models tend to reflect and reinforce prevailing power relations and economic priorities [14]. This insight is consistent with broader critical perspectives in educational technology and AI governance, which emphasize that technological infrastructures are never value-neutral but are shaped by policy agendas, commercial interests, and institutional logics.

From this perspective, AI integration in education entails normative consequences that extend well beyond technical efficiency. Decisions concerning data collection, algorithmic design, platform governance, and institutional adoption implicitly encode values related to control, accountability, transparency, and the commodification of knowledge. The conceptual framework therefore rejects technologically deterministic narratives and instead emphasizes the contextual, political, and value-laden nature of AI-mediated education.

3.3. Analytical Dimensions

To operationalize this conceptual framework, the study analyzes AI and digitalization in education across four interrelated analytical dimensions:

- (1)

- Educational Purpose and Meaning.

This dimension examines how AI reshapes prevailing conceptions of educational purpose, including tensions between education as a process of human formation and education as a system optimized for performance, efficiency, and measurable outputs.

- (2)

- Equity and Social Justice.

This dimension assesses whether AI integration contributes to or undermines educational equity by examining issues related to access, digital divides, and the differential impact of AI systems across social, institutional, and geopolitical contexts.

- (3)

- Ethical and Epistemic Integrity.

Here, the analysis focuses on data ethics, algorithmic bias, academic integrity, and transformations in epistemic authority within AI-mediated learning environments, including questions of authorship, assessment, and the credibility of knowledge production.

- (4)

- Governance and Commodification.

This dimension evaluates the role of market logic, platform capitalism, and institutional governance in shaping AI adoption, critically examining whether AI reinforces the commodification of education or can be subordinated to public-oriented and value-based educational goals.

Together, these dimensions provide an integrated analytical structure through which the sustainability of AI-driven education can be assessed beyond purely technical or instrumental criteria.

3.4. Analytical Approach

Methodologically, the study employs a qualitative critical analysis of contemporary academic literature, policy-oriented discussions, and conceptual debates on AI, digitalization, and sustainable education. Rather than aggregating empirical findings, the analysis synthesizes interdisciplinary insights to identify underlying assumptions, normative tensions, and conceptual gaps that shape current debates.

This analytical approach is explicitly interpretive and normative. It does not seek to measure the effectiveness of specific AI applications, but to evaluate the conditions under which AI aligns with, or undermines, sustainable education as a value-based project. By integrating conceptual analysis with critical interpretation, the study aims to illuminate how AI may be reoriented toward ethical, equitable, and human-centered educational futures.

3.5. Positioning of the Study

By combining Alam’s conceptual distinctions with a multidimensional and theoretically plural critical analysis of AI in education, this framework positions the study at the intersection of educational theory, ethics, and digital transformation. It contributes to existing scholarship by shifting the analytical focus from technological capability to normative alignment, emphasizing that sustainable education in the digital age depends not on AI adoption per se, but on the ethical, institutional, and value-based frameworks that govern its design, deployment, and use.

4. Materials and Methods

Although this study draws on a broad body of contemporary scholarly literature, it does not adopt a systematic literature review or meta-analytic design. Rather, it employs a qualitative, conceptual, and value-critical analytical approach. The description of databases, search terms, and inclusion parameters serves a scoping and delimiting function, aimed at clarifying the contours of the literature landscape consulted, rather than constituting an analytical protocol in itself. Accordingly, the study’s analytical core lies not in the mechanics of literature retrieval, but in the conceptual examination, deconstruction, and reconstruction of key educational and normative concepts related to artificial intelligence and sustainability.

4.1. Research Design

From a methodological standpoint, this study is situated at a macro-level of depth and scope within the research pyramid, as it addresses conceptual, normative, and governance-related questions rather than empirical or intervention-based problems. In terms of type, it constitutes qualitative theoretical research. With respect to its research approach, the study is grounded in interpretive and critical research paradigms, which are appropriate for examining educational meaning, ethical assumptions, and value-laden dimensions of sustainability in education.

Regarding its purpose, the study is explanatory and normative, aiming to clarify conceptual distinctions and critically assess the conditions under which artificial intelligence (AI) contributes to, or undermines, sustainable education as a value-based and human-centered project. The type of inference employed is primarily abductive and analytical, allowing the study to move iteratively between existing literature, conceptual distinctions, and normative interpretation. In terms of data sources, the research relies on secondary data, consisting of peer-reviewed academic literature and policy-oriented normative documents. The time dimension of the study is cross-sectional and contemporary, focusing on recent developments in AI, digitalization, and sustainable education. Finally, the overall research design is best characterized as a structured qualitative critical analysis, integrating conceptual mapping, thematic analysis, and normative evaluation.

Within this methodological classification, the study adopts a qualitative, conceptual, and critical research design aimed at examining sustainable education in the age of artificial intelligence (AI) and digitalization from a value-based and normative perspective. Rather than producing empirical measurements or experimental outcomes, the research focuses on analyzing underlying concepts, theoretical frameworks, normative assumptions, and ethical tensions that shape contemporary debates on AI-driven education.

This design is particularly appropriate for addressing questions related to educational purpose, social justice, human dignity, and sustainability, which cannot be adequately captured through purely quantitative or intervention-based methodologies. Accordingly, the study is situated within established interpretive and critical traditions of educational research, emphasizing conceptual clarity, theoretical coherence, and normative evaluation.

4.2. Materials and Data Sources

The materials analyzed in this study consist of peer-reviewed academic literature, including conceptual, theoretical, and selected empirical studies published in international journals. The literature search was conducted using Scopus, Web of Science, ERIC, and Google Scholar, with a primary focus on publications from 2015 to 2024, in order to capture recent developments in artificial intelligence, digitalization, and sustainable education.

Key search terms were used in various combinations and included artificial intelligence in education, digitalization of education, sustainable education, education for sustainable development, educational commodification, AI ethics in education, and value-based education. These terms were selected to ensure coverage of technological, ethical, governance-related, and educational dimensions relevant to the analytical framework of the study.

Sources were included if they (a) addressed AI or digital technologies in educational contexts; (b) engaged explicitly with sustainability, ethics, or educational values; and (c) contributed conceptually or analytically to debates on educational purpose, equity, epistemic integrity, or governance. Sources were excluded if they were purely technical, commercially oriented, or lacked relevance to ethical, educational, or sustainability-related dimensions.

In addition to academic literature, the analysis draws on policy-oriented documents and normative frameworks related to sustainable development, educational equity, and digital transformation, including reports issued by international organizations. All materials analyzed are publicly available, ensuring transparency and analytical traceability.

4.3. Analytical Procedure

The analysis was conducted through a structured qualitative critical procedure guided by an explicit analytical framework. This framework is organized around four interrelated analytical dimensions—educational purpose and meaning; equity and social justice; ethical and epistemic integrity; and governance and commodification—which provided the conceptual structure through which the selected literature was systematically examined and interpreted.

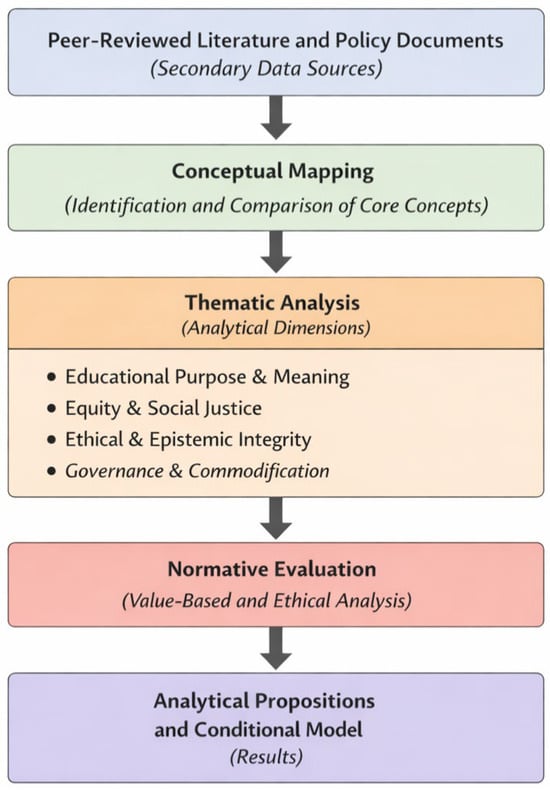

The overall analytical flow followed in the study is illustrated schematically in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Illustrative scoping of the literature landscape informing the conceptual analysis. The figure serves a delimiting and transparency function by outlining the body of literature consulted and does not represent a systematic review or an analytical coding protocol.

The analytical process followed a concept-driven and theoretically guided sequence. First, core concepts central to contemporary debates on AI and sustainable education—such as sustainability, educational purpose, efficiency, equity, and governance—were identified through a critical reading of the literature. Second, these concepts were examined in relation to their normative tensions and implicit value assumptions. Third, recurrent conceptual patterns were clustered into analytically meaningful themes. Finally, these themes were synthesized and reconstructed into a set of analytical propositions that articulate the conditional mechanisms through which AI may either support or undermine sustainable education. Throughout this process, interpretive judgment was exercised reflexively and transparently, in line with established practices in qualitative conceptual and value-critical analysis.

4.3.1. Conceptual Mapping

The first stage of analysis involved conceptual mapping through the systematic identification of key concepts across the selected literature. Core concepts such as sustainable education, sustainability in education, digitalization, commodification, ethical governance, equity, and educational purpose were identified and comparatively examined in order to analyze how they are defined, operationalized, and related to one another across different theoretical, empirical, and policy-oriented contexts. This stage enabled the clarification of conceptual boundaries, as well as the identification of tensions and overlaps among competing interpretations within debates on AI-driven educational transformation.

4.3.2. Thematic Analysis

In the second stage, the reviewed literature was organized and examined according to the predefined analytical dimensions of the study. Within each dimension, recurring themes, dominant narratives, and critical points of divergence concerning the role of artificial intelligence in education were identified through iterative reading and systematic cross-comparison of sources. Particular attention was given to tensions between enabling and critical perspectives, especially in relation to access, equity, marketization processes, and governance conditions. Themes were derived analytically through their alignment with the study’s conceptual framework rather than generated inductively in isolation, thereby ensuring coherence and transparency in the analytical process. These analytical dimensions and their associated illustrative themes are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Analytical Dimensions and Illustrative Themes Guiding the Study.

4.3.3. Normative Evaluation

In the final stage, the outcomes of conceptual mapping and thematic analysis were subjected to normative evaluation grounded in value-based educational theory and ethical frameworks. This stage critically examined the implications of AI integration for human dignity, epistemic integrity, educational meaning, and social justice. Normative evaluation allowed the synthesis of analytically grounded findings and facilitated the articulation of broader ethical and educational implications, moving beyond descriptive reporting toward critical interpretation.

The findings presented in Section 5 (Results) are organized in accordance with the same analytical dimensions employed throughout the analytical procedure. This alignment ensures a transparent and traceable analytical chain linking literature selection, conceptual framing, thematic synthesis, and normative evaluation. Consequently, the results do not emerge from impressionistic interpretation, but are systematically derived from the predefined analytical framework guiding the study.

4.4. Ethical Considerations

This research does not involve human participants, animals, personal data, or experimental interventions. Consequently, ethical approval from an institutional review board was not required. Nevertheless, the study adheres to established principles of academic integrity, including accurate representation of sources, critical engagement with existing scholarship, and transparency in methodological choices.

4.5. Use of Generative Artificial Intelligence

Generative artificial intelligence tools were used solely for language refinement and editorial assistance, including grammar checking, stylistic improvement, and formatting support. Generative AI was not used to generate original data, analytical arguments, conceptual frameworks, or interpretive conclusions. All intellectual content, analytical judgments, and normative positions presented in this article are the sole responsibility of the authors.

5. Results

This section presents the analytical results of the study by directly answering the central research question: under what conditions does artificial intelligence contribute to sustainable education as a value-based and human-centered project, and under what conditions does it undermine it?

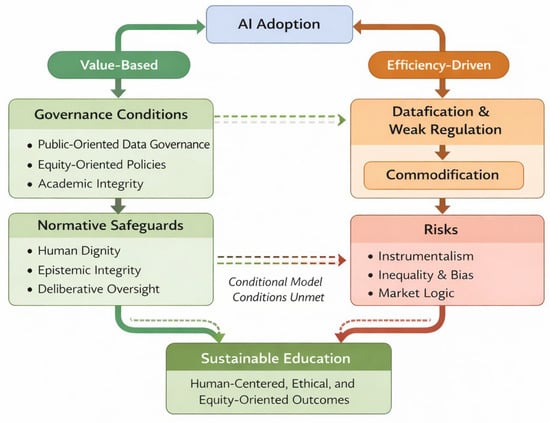

The analysis demonstrates that artificial intelligence does not exert a uniform, inherently positive, or inherently negative influence on educational sustainability. Rather, its effects are conditional and governance-mediated. AI contributes to sustainable education when its adoption is subordinated to explicit educational purposes, ethical constraints, equity-oriented governance, and the protection of epistemic integrity. Conversely, when AI is embedded within efficiency-driven, data-centric, and weakly regulated environments, it tends to reinforce instrumentalism, commodification, and educational inequality.

The overall analytical logic of these results is synthesized in Figure 2, which presents a conditional model of AI and sustainable education.

Figure 2.

Conditional model of AI and sustainable education.

These results are articulated below as analytically derived propositions that synthesize the study’s value-critical examination across four interrelated analytical dimensions: educational purpose and meaning; equity and social justice; ethical and epistemic integrity; and governance and commodification. Together, these propositions form an integrated explanatory account rather than a descriptive restatement of existing scholarship [3,13,14,33].

5.1. Analytical Result 1: The “Efficiency–Sustainability Substitution” Mechanism

A central analytical result is that AI-driven educational reforms frequently operate through an efficiency–sustainability substitution mechanism, whereby “sustainability” is implicitly redefined as operational performance—such as scalability, optimization, and measurable outputs—rather than as a value-based educational project. Under this mechanism, AI is framed as a sustainability instrument primarily because it delivers efficiency gains, even when these gains are not normatively aligned with sustainable education in its human-centered sense [7,8,13,14].

Crucially, this substitution does not require explicit market rhetoric. It often emerges through policy and institutional discourses that equate “modernization,” “innovation,” or “digital transformation” with sustainability. As a result, sustainability claims become increasingly metric-dependent: educational improvement is recognized mainly through what can be measured, automated, and benchmarked. This process risks displacing formative educational purposes related to meaning, subject formation, and democratic responsibility [7,8,21,33].

The analysis indicates that this substitution mechanism is weakened when AI adoption is guided by explicit educational aims and ethical priorities that resist reduction to performance indicators—such as human dignity, social justice, and epistemic integrity—and when educators retain a central role in shaping AI-mediated practices [8,13,33].

This mechanism is consistent with empirical accounts indicating that AI-enabled reforms are frequently operationalized through performance metrics, automated monitoring, and efficiency-oriented implementation in institutional practice, especially where accountability is dashboard-driven or market-aligned [15,18,26].

In these documented settings, sustainability discourse is commonly translated into operational indicators such as completion rates, engagement dashboards, predictive learning analytics, and productivity benchmarks. As a result, educational success is increasingly recognized through what can be measured, automated, and optimized, illustrating how efficiency-oriented AI applications may substitute value-based educational aims without explicit reference to marketization or commercial intent [15,18,26].

5.2. Analytical Result 2: The “Datafication-to-Commodification” Governance Pathway

A second major result identifies a governance pathway through which AI-driven digitalization can shift education from a value-based practice toward a commodified service: datafication → platform governance → market-aligned accountability → commodification [10,11,12,35,36,40].

AI systems intensify the production of educational data, including behavioral traces, performance analytics, and predictive profiling. These data streams reshape institutional decision-making by reconfiguring accountability around dashboards, ranking logics, and comparative metrics. Over time, educational value becomes increasingly expressed through data outputs compatible with market coordination—efficiency, competition, and standardization—thereby converting learning processes and student data into strategic assets [10,11,26,31,38].

The analysis shows that this pathway is not technologically inevitable but institutionally mediated. It is constrained when educational institutions adopt robust public-oriented governance frameworks, including transparent data governance, limits on extractive data practices, accountability mechanisms for algorithmic decision-making, and policies that explicitly subordinate platform logic to educational ethics [5,34,41,42].

Empirical and policy-oriented studies on data governance and academic integrity in AI-mediated education further indicate that datafication practices can reshape institutional accountability and learner behavior in ways that intensify commodification pressures and integrity risks [25,26].

These studies describe how learning analytics dashboards, predictive risk scoring systems, and platform-based accountability mechanisms increasingly mediate institutional decision-making. In doing so, AI-driven data infrastructures reframe learning processes, student behavior, and educational outcomes as governable and comparable data objects, thereby facilitating the transformation of educational activity and learner data into exchangeable and strategically managed asset [25,26].

5.3. Analytical Result 3: Normative Friction, Equity, and Epistemic Integrity as Interdependent Conditions

The analysis further demonstrates that sustainable AI adoption in education depends on the interaction of three interdependent conditions: normative friction, governance-based equity, and epistemic integrity. Rather than functioning as isolated variables, these conditions jointly determine whether AI supports or undermines sustainable education.

First, the presence of normative friction—ethical constraints, deliberative safeguards, and institutional oversight—emerges as a constitutive condition of sustainability. Where normative friction is absent, AI adoption tends to proceed along managerial rationalities (“what works,” “what scales”), and sustainability becomes synonymous with continuity and efficiency. Where normative friction is present, AI is more likely to remain an instrument supporting educational purposes rather than restructuring those purposes [3,5,33,34,42].

Second, the results indicate that equity outcomes under AI are best explained as a function of governance capacity rather than technological availability. AI does not generate equity autonomously; it amplifies existing institutional and structural conditions. Well-governed and well-resourced contexts can translate AI adoption into improved access and support, whereas weakly regulated and under-resourced contexts tend to experience intensified inequalities through differential access, uneven oversight, and heightened vulnerability to bias and exclusion [9,15,16,17,18,25]. Under such conditions, AI-mediated systems may reproduce disadvantages in opaque and technically mediated ways [25,27,28,30,43].

Third, the analysis identifies epistemic integrity as a “hidden variable” of sustainability. AI-mediated education affects not only learning efficiency but also the credibility, authorship, and authority structures through which knowledge is produced and validated. Automation of feedback and assessment may reduce spaces for critical reasoning; generative tools introduce ambiguities around authorship and originality; and algorithmic mediation can shift epistemic authority away from educators and scholarly communities toward opaque or commercially governed systems [23,24,29,34,37]. These dynamics threaten sustainable education insofar as sustainability is grounded in long-term intellectual and moral development rather than short-term performance [7,8,33].

The analysis indicates that equity-supportive and epistemically robust outcomes are contingent upon deliberate governance choices, including equity-oriented design, institutional accountability, bias mitigation, and explicit norms of academic integrity [3,18,20,25,29,34].

5.4. Analytical Result 4: Cultural and Value-Based Contexts as Sensitivity Amplifiers

Within the proposed conditional model, culturally and religiously grounded educational contexts are not approached as distinct empirical cases, but as analytically revealing environments that function as sensitivity amplifiers. In such settings, the integration of artificial intelligence engages more directly with questions of educational purpose, epistemic authority, and moral responsibility, thereby making visible conditional dynamics that are structurally present across educational systems but often remain less explicit elsewhere.

Because education in these contexts is understood not merely as a service, but as a value-transmitting and morally charged practice, AI adoption can have disproportionate effects on the perceived authority of educators and the normative status of knowledge itself [3,28,31,32,41]. These effects help explain why universal or “one-size-fits-all” sustainability claims are analytically weak: the same AI system may be experienced as enabling in one context and as corrosive in another, depending on how educational authority, legitimacy, and moral formation are socially organized.

Accordingly, sustainable integration of AI in value-based educational contexts requires explicit alignment between technological use and educational aims, including safeguards against the commodification of knowledge and the displacement of relational and formative pedagogical practices.

5.5. Integrated Result: A Conditional Model of AI and Sustainable Education

Synthesizing these analytical results yields a conditional explanatory model: AI supports sustainable education only when

- (i)

- sustainability is not substituted by efficiency metrics,

- (ii)

- datafication is governed by public-oriented and ethical accountability,

- (iii)

- normative friction constrains instrumental adoption,

- (iv)

- equity is treated as a governance responsibility,

- (v)

- epistemic integrity is actively protected—particularly in value-based contexts where moral formation and authority structures are central [3,13,14,33,42].

Accordingly, the results move beyond the generic claim that AI has “benefits and risks”. The distinctive contribution lies in specifying mechanisms, boundary conditions, and governance pathways through which AI shapes educational sustainability in divergent and context-dependent ways. These integrated analytical results, mechanisms, and boundary conditions are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Analytical results, mechanisms, and boundary conditions of AI-driven education.

6. Discussion

This section advances the analytical results by situating them within broader theoretical, policy, and institutional debates on artificial intelligence (AI), digitalization, and sustainable education. Rather than reiterating the findings, the discussion elevates them into a conditional explanatory account that clarifies how and under what governance conditions AI contributes to—or undermines—the normative aims of sustainable education. In doing so, the section translates value-oriented concepts into operational implications grounded in concrete educational contexts and policy frameworks.

6.1. From Dual Effects to a Conditional Model of AI in Sustainable Education

The findings indicate that AI does not exert a uniform or inherently progressive influence on education. Instead, its effects are context-dependent and governance-mediated, confirming that AI functions as an amplifier of prevailing institutional logics rather than as an autonomous driver of educational transformation. This observation aligns with critical scholarship rejecting technological determinism and emphasizing the role of organizational priorities, regulatory capacity, and normative orientation in shaping educational outcomes.

At a higher level of abstraction, this leads to a conditional model: AI supports sustainable education only when its deployment is embedded within governance arrangements that preserve educational purpose, constrain extractive data practices, and maintain human oversight in pedagogical decision-making. Where such conditions are absent, AI-driven digitalization tends to reinforce instrumental and performance-oriented models that prioritize efficiency and scalability over formative educational goals.

6.2. Distinguishing System Sustainability from Sustainable Education

A central theoretical contribution of this study lies in clarifying the distinction between sustainability in education and sustainable education. Many AI-enabled outcomes documented in contemporary reforms—such as administrative automation, personalized content delivery, and data-driven performance optimization—enhance the operational sustainability of educational systems. However, these outcomes do not necessarily advance sustainable education as a normative project concerned with human development, social responsibility, and long-term epistemic integrity.

This distinction helps explain why AI initiatives may simultaneously improve measurable outputs while generating concerns about depersonalization, commodification, and value erosion. Treating efficiency gains as indicators of sustainability risks collapsing normative educational aims into managerial performance criteria. The discussion therefore reframes sustainability not as a technical achievement, but as a value-dependent educational orientation that must be actively protected through governance and policy design.

6.3. Commodification and the Role of Institutional Governance

The findings indicate that artificial intelligence does not introduce commodification into education ex nihilo; rather, it intensifies and operationalizes pre-existing market logics through distinct technological mechanisms. In higher and transnational education systems, AI accelerates commodification by enabling large-scale data extraction, performance benchmarking, and platform-based competition, thereby aligning educational value with metrics of efficiency, visibility, and market responsiveness.

This dynamic becomes particularly evident when examining specific AI applications. In the case of generative AI systems (e.g., large language models used for writing support, assessment, and feedback), educational practices risk being reconfigured around the automation of cognition itself. Writing, evaluation, and knowledge production increasingly appear as standardized services that can be generated, optimized, and consumed on demand. This transformation reframes learning as a transactional output rather than a formative process, raising ethical concerns related to authorship, originality, and responsibility for knowledge production.

Similarly, adaptive learning systems contribute to commodification through algorithmically generated learning pathways that rely on historical performance data and predictive analytics. While such systems promise personalization, they also introduce risks of algorithmic bias by reproducing existing inequalities embedded in training data. Learners may be silently steered toward predefined educational trajectories, limiting epistemic agency and reinforcing stratified outcomes under the guise of optimization and efficiency.

The logic of commodification is further reinforced through learning analytics and AI-driven automation within learning management systems. Dashboards, performance indicators, and predictive risk scores increasingly shape institutional decision-making, transforming students into data profiles and educational success into measurable outputs. In these contexts, governance opacity becomes a central ethical issue: pedagogical judgments are partially displaced by automated metrics that are often inaccessible to critical scrutiny by educators and learners alike.

From a governance perspective, these technology-specific mechanisms demonstrate that ethical risks associated with AI—such as data commodification, algorithmic bias, and surveillance-driven assessment—cannot be addressed through technical design alone. They require institutional and regulatory interventions capable of subordinating AI infrastructures to public educational values rather than market imperatives. Policy-oriented approaches emphasizing transparency, accountability, data protection, and value-sensitive design provide essential tools for counteracting the commodifying tendencies embedded in AI-mediated educational systems.

Taken together, this analysis reframes commodification not as an abstract ethical concern, but as a technology-mediated process that unfolds differently across generative AI, adaptive learning systems, and learning analytics. Sustainable education in the age of AI therefore depends on governance frameworks that recognize these distinctions and actively regulate how specific AI applications reshape educational purposes, practices, and power relations.

6.4. Equity, Ethics, and Epistemic Integrity in Concrete Contexts

The discussion of equity and ethics gains analytical depth when situated within concrete educational contexts. Recent global and regional studies show that generative AI tools are deployed across educational levels—from primary schooling to higher education and vocational training—yet their benefits remain unevenly distributed. Disparities in digital infrastructure, institutional capacity, and regulatory oversight mean that AI adoption often reproduces or amplifies existing inequalities rather than alleviating them.

Within this discussion, culturally and religiously grounded educational contexts are not treated as separate cases, but as analytically revealing environments in which issues of governance, epistemic authority, and ethical accountability become structurally visible. Their inclusion thus serves to test the explanatory reach of the proposed conditional model rather than to introduce a new thematic direction.

Importantly, the explanatory validity of the conditional model advanced in this study does not depend on any specific cultural or religious setting. Rather, the inclusion of value-dense educational contexts serves to clarify and stress-test the model’s underlying assumptions, thereby strengthening—rather than constraining—its broader analytical and normative applicability.

Higher education contexts illustrate this tension clearly. AI-driven automation within learning management systems—such as automated grading, feedback generation, and administrative streamlining—can improve accessibility and efficiency, including in public university systems. However, without robust governance, these same tools raise questions about academic integrity, authorship, and the erosion of educators’ epistemic authority. These challenges are particularly salient in value-based and culturally grounded educational settings, where education is inseparable from moral responsibility and the cultivation of judgment.

Accordingly, ethical principles such as fairness, dignity, and integrity acquire practical meaning only when translated into governance requirements: data protection frameworks, algorithmic bias audits, transparent accountability structures, and sustained professional development for educators. The findings thus support approaches that treat ethics not as an external constraint on innovation, but as an internal condition for sustainable educational practice.

6.5. Policy and Practice Implications

At the policy level, the analysis suggests that sustainable education in the digital age cannot be achieved through innovation strategies alone. Educational policies must move beyond a narrow focus on competitiveness and technological adoption toward governance-oriented frameworks that prioritize equity, human-centered pedagogy, and epistemic responsibility. This includes explicit standards for data governance, mechanisms for auditing algorithmic decision-making, and investments aimed at reducing digital divides across institutions and learner populations.

For educational practice, the discussion reinforces the importance of positioning AI as a supportive instrument rather than a substitutive authority. Educators and institutions remain central agents in shaping how AI is integrated into teaching, assessment, and learning design. Sustainable practice requires preserving reflective pedagogy, fostering critical engagement with AI-generated outputs, and maintaining meaningful human relationships at the core of educational processes.

6.6. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

As a qualitative and conceptual inquiry, this study does not provide empirical measurement of AI’s effects across specific institutional or national settings. Future research could extend the proposed conditional model through comparative case studies, policy analyses, or mixed-method investigations examining how value-based AI governance is enacted in practice.

Further work is particularly needed in culturally and religiously grounded educational contexts, where questions of epistemic authority, moral formation, and technological mediation intersect in distinctive ways. Such research would contribute to more context-sensitive and policy-relevant models of sustainable education under conditions of rapid digital transformation.

7. Conclusions

This study has examined sustainable education in the age of artificial intelligence (AI) and digitalization through a value-critical and condition-oriented analytical framework. By conceptually distinguishing between sustainable education, sustainability in education, and education for sustainable development, the article has shown that contemporary debates on AI in education often collapse normative educational aims into metrics of technological efficiency, thereby obscuring the ethical, epistemic, and governance conditions upon which educational sustainability depends.

The analysis demonstrates that AI does not exert a uniform or intrinsic influence on educational systems. Rather, its educational effects are contingent upon specific institutional, regulatory, and value-based contexts. Under conditions characterized by ethical oversight, public-oriented governance, and human-centered pedagogical integration, AI can support access, personalization, and instructional enhancement. Conversely, in contexts shaped by weak regulation, market-driven accountability, and data-centric performance regimes, AI tends to intensify processes of commodification, inequality, and epistemic erosion.

The central contribution of this study lies in reframing AI and digitalization as mediated instruments within sustainable education rather than as self-justifying solutions. Sustainable education in the digital age emerges not from technological adoption per se, but from the subordination of AI to clearly articulated educational purposes grounded in human dignity, social justice, and epistemic integrity. By advancing a conditional and value-oriented analytical model, the study challenges technocratic and instrumental narratives that treat innovation as a sufficient or neutral pathway to sustainability.

At the policy and institutional level, the findings highlight the necessity of governance frameworks that align AI deployment with ethical accountability, equity considerations, and the preservation of meaningful pedagogical relationships. Educational technologies should be designed and regulated to support reflective learning, critical reasoning, and moral formation, rather than reducing education to data-driven optimization and performative efficiency.

Finally, this study underscores the need for continued interdisciplinary research that integrates empirical investigation with normative, cultural, and ethical analysis. Future research that combines context-sensitive empirical evidence with value-critical frameworks will be essential for developing robust models of sustainable education capable of responding to the complex and uneven effects of AI-driven digitalization across diverse educational settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.A.A. and A.O.A.; methodology, F.A.A. and A.O.A.; formal analysis, F.A.A.; investigation, F.A.A. and A.O.A.; writing—original draft preparation, F.A.A.; writing—review and editing, F.A.A. and A.O.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used generative artificial intelligence tools for language refinement and formatting assistance. The authors reviewed, edited, and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

References

- Nedungadi, P.; Tang, K.-Y.; Raman, R. The Transformative Power of Generative Artificial Intelligence for Achieving the Sustain-able Development Goal of Quality Education. Sustainability 2024, 16, 29779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Ribeiro, P.C.C.; Mazutti, J.; Salvia, A.L.; Marcolin, C.B.; Borsatto, J.M.L.S.; Sharifi, A.; Sierra, J.; Luetz, J.M.; Preto-rius, R.; et al. Using Artificial Intelligence to Implement the UN Sustainable Development Goals at Higher Education Institutions. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2024, 31, 726–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Guidance for Generative AI in Education and Research; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2023; 44p, ISBN 978-92-3-100612-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). OECD Digital Education Outlook 2023: Towards an Effective Digital Education Ecosystem; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-digital-education-outlook-2023_c74f03de-en.html (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Education Policy Outlook 2023: Empowering All Learners to Go Green; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/education-policy-outlook-2023_f5063653-en.html (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- UNESCO. AI and the Future of Education: Disruptions, Dilemmas and Directions; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2025; 165p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selwyn, N. On the Limits of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Education. Nord. Tidsskr. Pedagog. Krit. 2024, 10, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesta, G.J.J. Good Education in an Age of Measurement: Ethics, Politics, Democracy; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, T.P.; Dixon-Román, E. Platform Governance and Education Policy: Power and Politics in Emerging EdTech Ecologies. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 2024, 46, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komljenovic, J.; Birch, K.; Sellar, S.; Bergvik Rensfeldt, A.; Nappert, P.-L.; Noteboom, J.; Parcerisa, L.; Pardo-Guerra, J.P.; Poutanen, S.; Robertson, S.; et al. Digitalised Higher Education: Key Developments, Questions, and Concerns. Discourse: Stud. Cult. Polit. Educ. 2025, 46, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, B.; Bayne, S.; Shay, S. The Datafication of Teaching in Higher Education: Critical Issues and Perspectives. Teach. High. Educ. 2020, 25, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srnicek, N. Platform Capitalism; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016; 120p, ISBN 978-1-5095-0486-2. Available online: https://www.politybooks.com/bookdetail?book_slug=platform-capitalism--9781509504862 (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Alam, G.M. Sustainable Education, Sustainability in Education and Education for Sustainable Development: The Reconciliation of Variables and the Path of Education Research in an Era of Technologization. Sustainability 2025, 17, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, G.M. Sustainable Education and Sustainability in Education: The Reality in the Era of Internationalisation and Commodi-fication in Education—Is Higher Education Different? Sustainability 2023, 15, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okulich-Kazarin, V.; Artyukhov, A.; Skowron, Ł.; Artyukhova, N.; Wołowiec, T. Will AI Become a Threat to Higher Education Sustainability? A Study of Students’ Views. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadden, I.M.; García-Alonso, E.; López Meneses, E. Science Mapping of AI as an Educational Tool Exploring Digital Inequalities: A Sociological Perspective. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2024, 8, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón, J.; Patiño, E.; Marulanda, C. Systematic Review of Artificial Intelligence in Education: Trends, Benefits, and Challenges. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2025, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutambik, I. The Use of AI-Driven Automation to Enhance Student Learning Experiences in the KSA: An Alternative Pathway to Sustainable Education. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakakni, D.; Safa, N. Artificial Intelligence in the L2 Classroom: Implications and Challenges on Ethics and Equity in Higher Ed-ucation: A 21st Century Pandora’s Box. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2023, 4, 100179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artyukhov, A.; Wołowiec, T.; Artyukhova, N.; Bogacki, S.; Vasylieva, T. SDG 4, Academic Integrity and Artificial Intelligence: Clash or Win–Win Cooperation? Sustainability 2024, 16, 8483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selwyn, N. Should Robots Replace Teachers? AI and the Future of Education, 1st ed.; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; 160p, ISBN 978-1-5095-2896-7. Available online: https://research.monash.edu/en/publications/should-robots-replace-teachers-ai-and-the-future-of-education/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Vindigni, G. Data-Driven Disparities: How AI Applications in Education May Perpetuate or Mitigate Inequality. Eur. J. Soc. Manag. Technol. 2025, 1, 4–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utterberg Modén, M.; Ponti, M.; Lundin, J.; Tallvid, M. When Fairness Is an Abstraction: Equity and AI in Swedish Compulsory Education. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2023, 68, 790–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdivieso, T.; González, O. Generative AI Tools in Salvadoran Higher Education: Balancing Equity, Ethics, and Knowledge Management in the Global South. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Schoolnet. Data in Education: Datafication, Educational Data Literacy and Governance Challenges; European Schoolnet: Brussels, Belgium, 2025; Available online: http://www.eun.org/data-in-education (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Espinoza Vidaurre, S.E.; Velásquez Rodríguez, N.C.; Gambetta Quelopana, R.L.; Martinez Valdivia, A.N.; Leo Rossi, E.A.; No-lasco-Mamani, M.A. Perceptions of Artificial Intelligence and Its Impact on Academic Integrity Among University Students in Peru and Chile: An Approach to Sustainable Education. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slimi, Z.; Villarejo Carballido, B. Navigating the Ethical Challenges of Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education: An Analysis of Seven Global AI Ethics Policies. TEM J. 2023, 12, 590–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas Contreras, M.; Portilla Jaimes, J.O. AI Ethics in the Fields of Education and Research: A Systematic Literature Review. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Symposium on Accreditation of Engineering and Computing Education (ICACIT), Bogota, Colombia, 3–4 October 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouta, A.; Torrecilla-Sánchez, E.; Pinto-Llorente, A.M. Design of a Future Scenarios Toolkit for an Ethical Implementation of Artificial Intelligence in Education. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 17051–17071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christophers, B. Rentier Capitalism: Who Owns the Economy, and Who Pays for It? Verso: London, UK, 2022; 512p, ISBN 978-1-78873-975-7. Available online: https://www.versobooks.com/products/871-rentier-capitalism?srsltid=AfmBOoplKhNGuKZNOmigD7O7J-BzFX_qhNDvuhuoFmRH9K2uL_CXhq9C (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Achruh, A.; Rapi, M.; Rusdi, M.; Idris, R. Challenges and Opportunities of Artificial Intelligence Adoption in Islamic Education in Indonesian Higher Education Institutions. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2024, 23, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fikri, M.; Muslim, M.; Yakin, F.A. Kecerdasan Buatan sebagai Simulakra Pendidikan: Analisis Kritis terhadap Krisis Nilai dan Otoritas Keilmuan Pesantren. J. Islam. Educ. Pedagog. 2025, 2, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). OECD AI Policy Observatory: Policies, Data and Analysis for Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence; OECD: Paris, France, 2026; Available online: https://oecd.ai/en/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- European Commission High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence. Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/ethics-guidelines-trustworthy-ai (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Manolev, J.; Sullivan, A.; Slee, R. The Datafication of Discipline: ClassDojo, Surveillance and a Performative Classroom Culture. Learn. Media Technol. 2019, 44, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowski, J. Too Smart: How Digital Capitalism Is Extracting Data, Controlling Our Lives, and Taking Over the World; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-0-262-53858-9. Available online: https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262538589/too-smart/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Floridi, L.; Cowls, J. A Unified Framework of Five Principles for AI in Society. Harv. Data Sci. Rev. 2019, 1, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittelstadt, B.D. Principles Alone Cannot Guarantee Ethical AI. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2019, 1, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, A.; Zowghi, D.; Bano, M. AI Governance: A Systematic Literature Review. AI Ethics 2025, 5, 3265–3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuboff, S. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power; PublicAffairs: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=56791 (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- OECD. OECD AI Principles: Overview; Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development: Paris, France, 2019; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/ai-principles.html (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- UNESCO. Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence; SHS/BIO/REC-AIETHICS/2021; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2021; 21p, Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/artificial-intelligence/recommendation-ethics (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Wieczorek, M. Using Ethical Scenarios to Explore the Future of Artificial Intelligence in Primary and Secondary Education. Learn. Media Technol. 2025, 50, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.