1. Introduction

The accelerating wave of scientific and technological innovation has made technological competition the central arena of great-power rivalry. Major economies are rapidly intensifying their science-and-technology strategies to secure first-mover advantages in this new round of global competition. China’s 20th CPC Congress proclaimed that the nation must be “guided by strategic demands, concentrate resources on original and frontier breakthroughs, and resolutely win the battle over critical core technologies.” In this context, mastering critical core technologies has become pivotal to China’s high-quality economic development, the attainment of the strategic high ground in international science-and-technology competition, and the realisation of technological self-reliance. Yet persistent technology sanctions and technology blockades continue to constrain China’s innovation trajectory, creating technological chokepoints. Therefore, faster advances in these areas are crucial for strengthening indigenous innovation and for mitigating exposure to external uncertainty, which in turn supports the country’s long-term strategic interests.

At the same time, a new technological revolution driven by digital technologies is profoundly reshaping global socio-economic development, signalling the advent of a digital–intelligence era. In order to capitalise on the opportunities presented by this transition, the Chinese government has issued a series of policy documents aimed at advancing digital–intelligence development. These include the Special Action Plan for Empowering SMEs through Digitalisation (2025–2027), the 14th Five-Year Plan for Intelligent Manufacturing, and the Guiding Opinions on Deepening Smart-City Development and Advancing City-wide Digital Transformation. The implementation of these initiatives has strengthened technological support and institutional safeguards for corporate innovation, thereby spurring breakthrough innovations. This, in turn, has become an increasingly important driver of socio-economic progress. In this context, it is crucial to explore how digital–intelligence policy can effectively expedite breakthroughs in firms’ key core technologies. Such an inquiry is not only an urgent practical concern for China’s current science and technology agenda but also a strategic imperative in the face of intensifying international competition and the pursuit of high-quality growth.

Digital–intelligence can be broadly defined as the convergence of digital and intelligent technologies. Leveraging advanced tools such as artificial intelligence (AI) and cloud computing, this convergence addresses the economy’s growing needs for effective information processing, analysis, and management [

1]. A large body of research has already evaluated the economic impacts of both digitalisation and AI at macroeconomic and firm levels. Digital–intelligence transformation can enhance firm performance [

2]. As a core component of digital–intelligence transformation, digital transformation is widely regarded as a key driver of firms’ innovation capability [

3]. Digital–intelligence transformation is a complex process [

4], and artificial intelligence, as the second pillar of digital intelligence, appears to exert a more nuanced influence on economic development. On one hand, investing capital in AI clearly promotes product innovation and supports firm growth [

5]. On the other hand, productivity gains driven by AI often entail substantial lags and may not be fully realised in the short term [

6]. Overall, digital–intelligence technologies offer multiple advantages for firms. For example, real-time conversion of digital information can substantially enhance corporate performance [

7]. Moreover, policy shocks such as the establishment of AI pilot zones can accelerate R&D investment and information sharing; these changes markedly improve both the quantity and quality of green innovation [

1].

Breakthroughs in key core technologies essentially represent radical innovations, which are crucial for sustainable development in both advanced and emerging economies [

8,

9]. At the technological frontier, such radical innovations are transformative: they can profoundly reshape consumer behaviour [

10] and materially strengthen a firm’s position in global competition [

11]. The existing literature identifies determinants of radical innovation from two main angles: external environment and internal resources. In terms of external drivers, embeddedness in the innovation ecosystem and technological spillovers are often cited as the most influential factors [

12,

13]. Government policies likewise provide an important impetus for radical innovation [

14]. On the internal side, factors such as financial constraints [

15] and absorptive capacity [

16] are widely recognised as pivotal firm-level determinants of radical innovation. Meanwhile, greater top-management frame flexibility helps incumbents broaden their cognitive lenses and competitive boundary scanning, facilitating the adoption of nonincremental innovations that extend beyond established technological trajectories [

17]. As digital–intelligence initiatives deepen, firms can deploy intelligent technologies more broadly across production domains, thereby expanding the scope of breakthrough innovation [

18].

As digital–intelligence technologies increasingly permeate economic and social activities, the transition toward digital–intelligent convergence has become a pivotal engine of corporate innovation and high-quality growth; however, whether this transformation genuinely enables firms to achieve breakthroughs in key core technologies remains an unresolved empirical question. This paper defines digital–intelligent policy synergy as a composite policy effect that arises when digitalisation-oriented policies and intelligence-oriented policies are jointly advanced within the same region, generating complementarities through consistency in policy objectives and the mutual reinforcement of policy instruments and implementation resources. Given the interactive and integrative nature of digital–intelligent technologies, a data-based digital–intelligent transformation can promote the restructuring and coordinated allocation of key production factors—capital, technology, and labour—thereby laying a foundation for policy synergy [

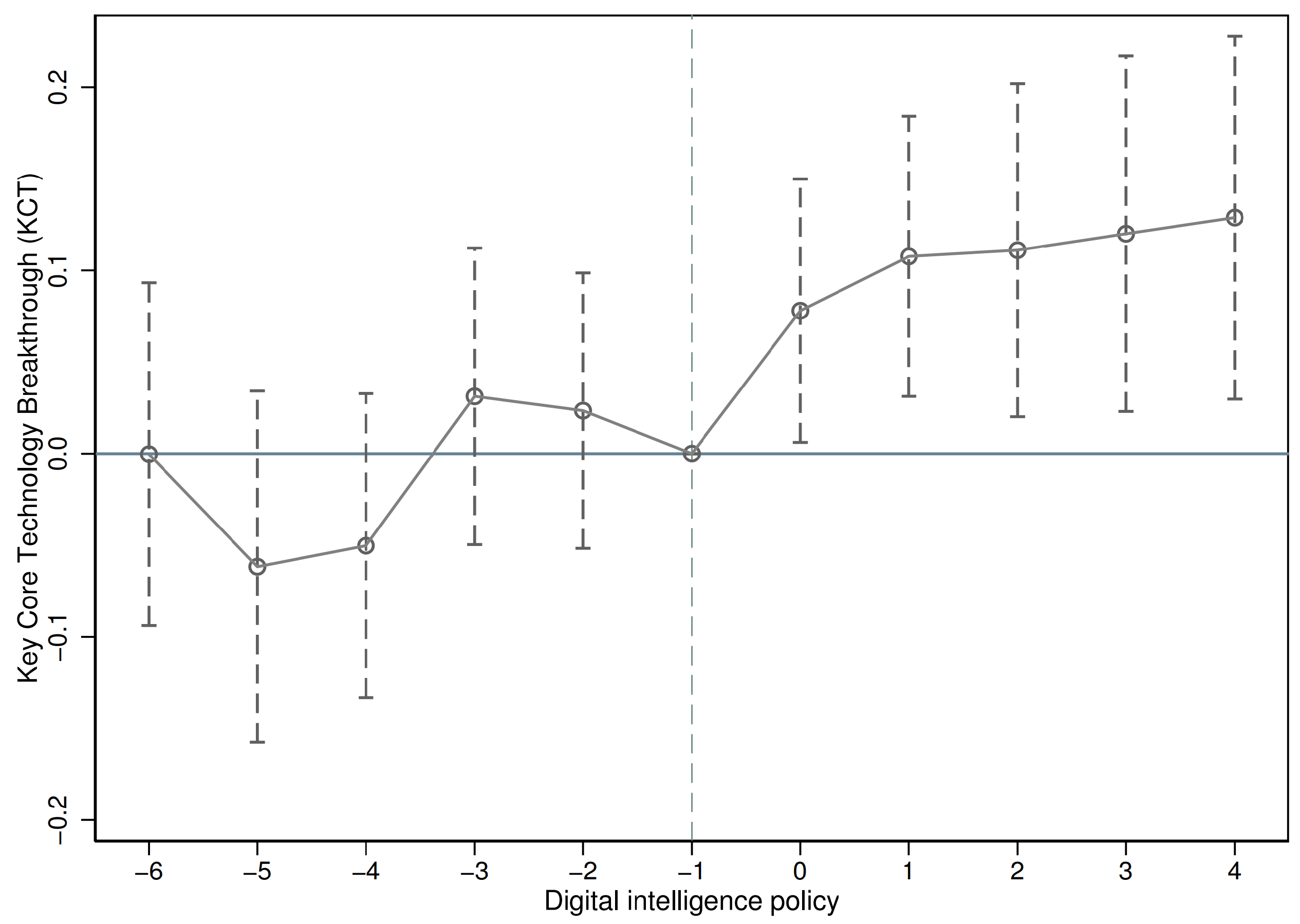

19]. Digital–intelligent policy synergy further emphasises that synergistic gains stem from the joint operation of data as a production factor and intelligent technologies, as well as their coupled influence on the behaviour of economic agents. In this study, we focus on two landmark policy initiatives in China: the National Big Data Comprehensive Pilot Zones (NBD) and the Artificial Intelligence Innovation and Application Pilot Zones (AIP). The NBD primarily focus on establishing institutional arrangements and infrastructure that elevate data into a productive asset, thereby transforming information resources into productive inputs; by contrast, the Artificial Intelligence Innovation and the AIP emphasise algorithmic capability by promoting the deployment of AI in real-world settings and its integration with industrial systems. In other words, the NBD initiative lays the groundwork, whereas the AIP initiative strengthens practical application. In this context, this study employs a difference-in-differences (DID) approach to identify the causal effect of digital–intelligent policy synergy on firms’ breakthroughs in key core technologies and to evaluate the effectiveness of these policy initiatives. Our findings provide theoretical insights into how digitalisation-related policies can, from a technology management perspective, alleviate constraints that impede progress in key core technologies.

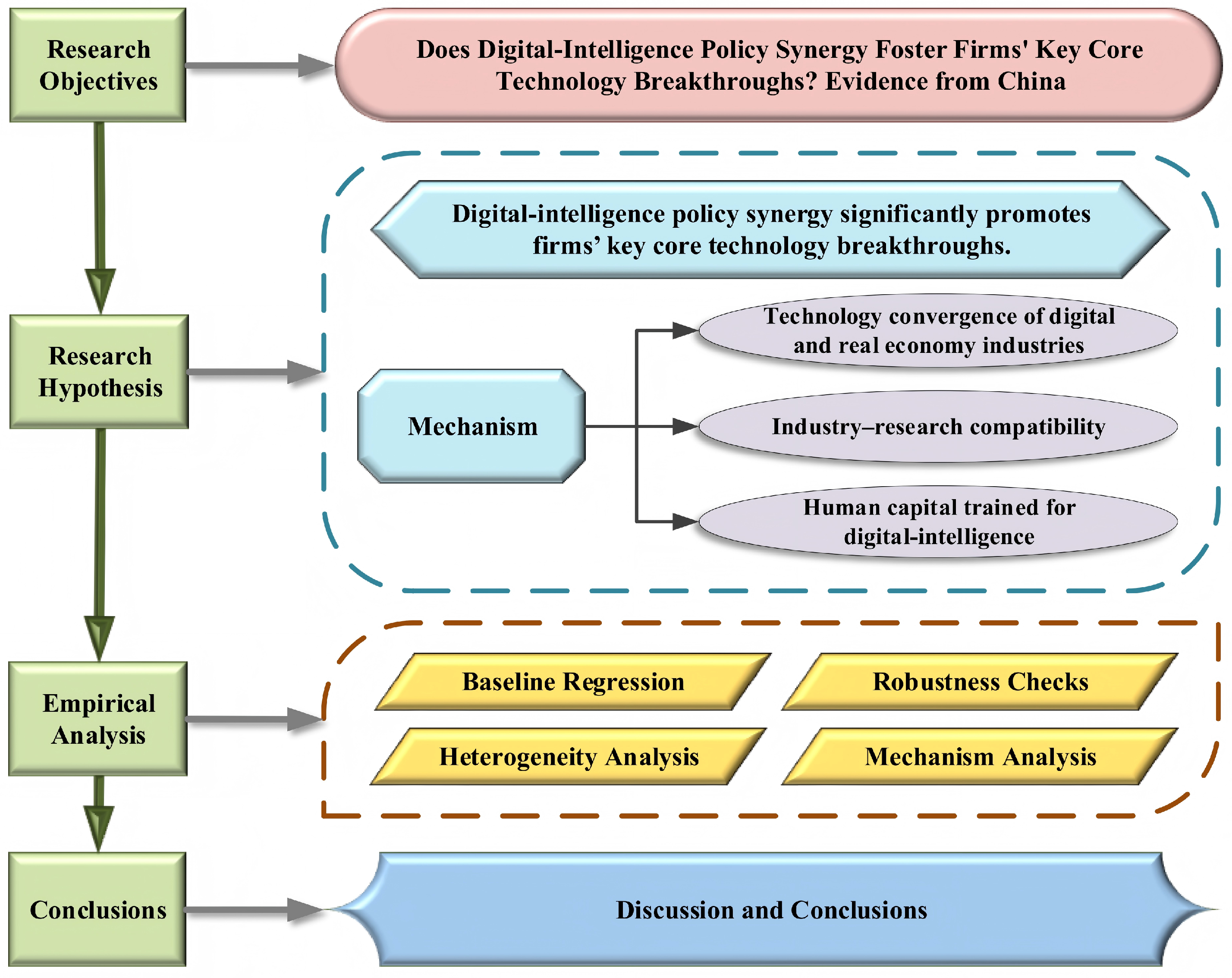

This study makes three key contributions. First, whereas existing research usually examines digitalisation and intelligentisation in isolation when considering firms’ breakthrough innovation, we consider their combined impact. By focusing on the dual dimensions of digital–intelligence synergy, this paper elucidates how the interplay between these two dimensions acts as a critical driver for breakthroughs in core technologies, thereby enriching the literature on policy complementarity and innovation management. Second, empirical work on digital–intelligence remains limited and often relies on composite indices. Exploiting two large-scale pilot policies in China and implementing a DID design, this study quantitatively identifies the synergistic effects of digital–intelligence policies, thereby extending the empirical evidence base. Third, whereas prior studies have concentrated mainly on mechanisms such as knowledge maturity and venture capital, we investigate three internal pathways—technology convergence between the digital economy and the real economy, industry–research compatibility, and optimised human capital trained for digital–intelligence. By combining firm-level publication data with micro-level recruitment data, we capture—in near real time—the reconfiguration of innovation inputs and human capital, enabling a more precise depiction of the dynamic evolution of firms’ key core technology breakthroughs.

The remainder of the paper is organised as follows.

Section 2 reviews the policy background of digital–intelligence and develops the theoretical framework and research hypotheses.

Section 3 introduces the empirical specification and describes variable construction.

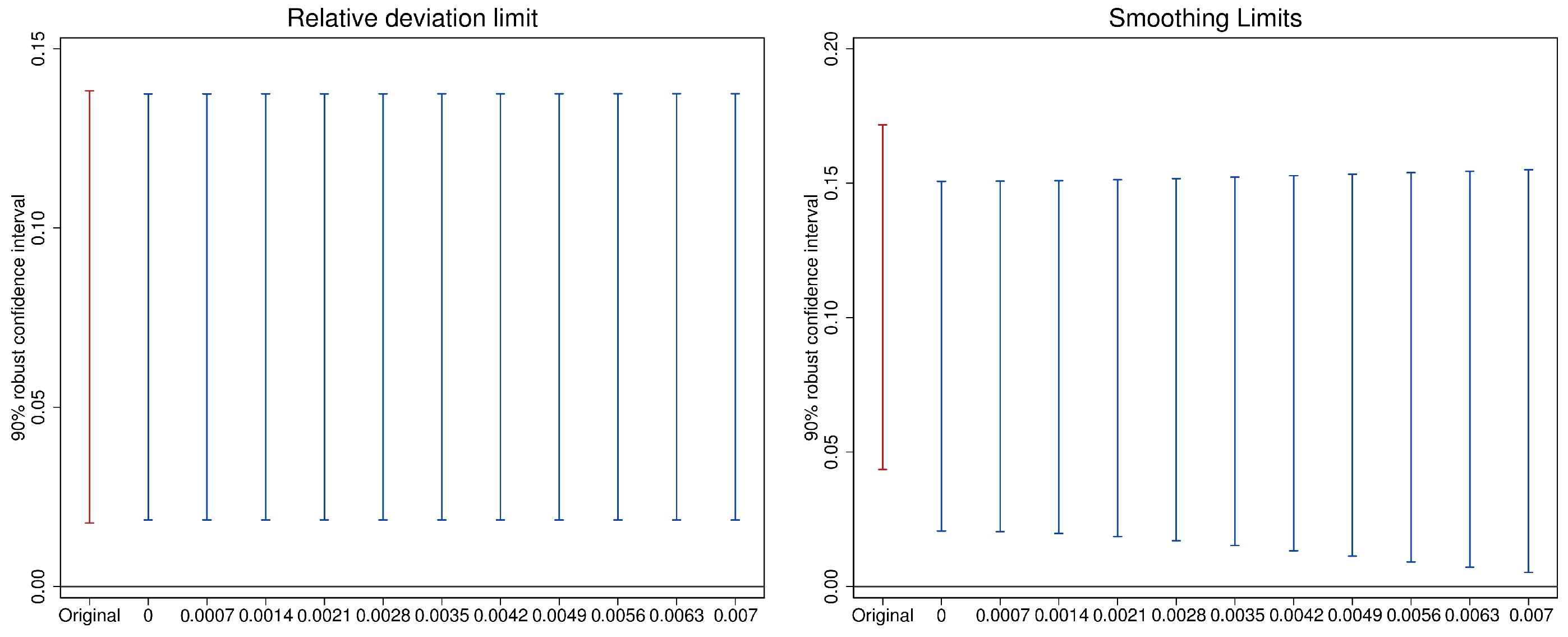

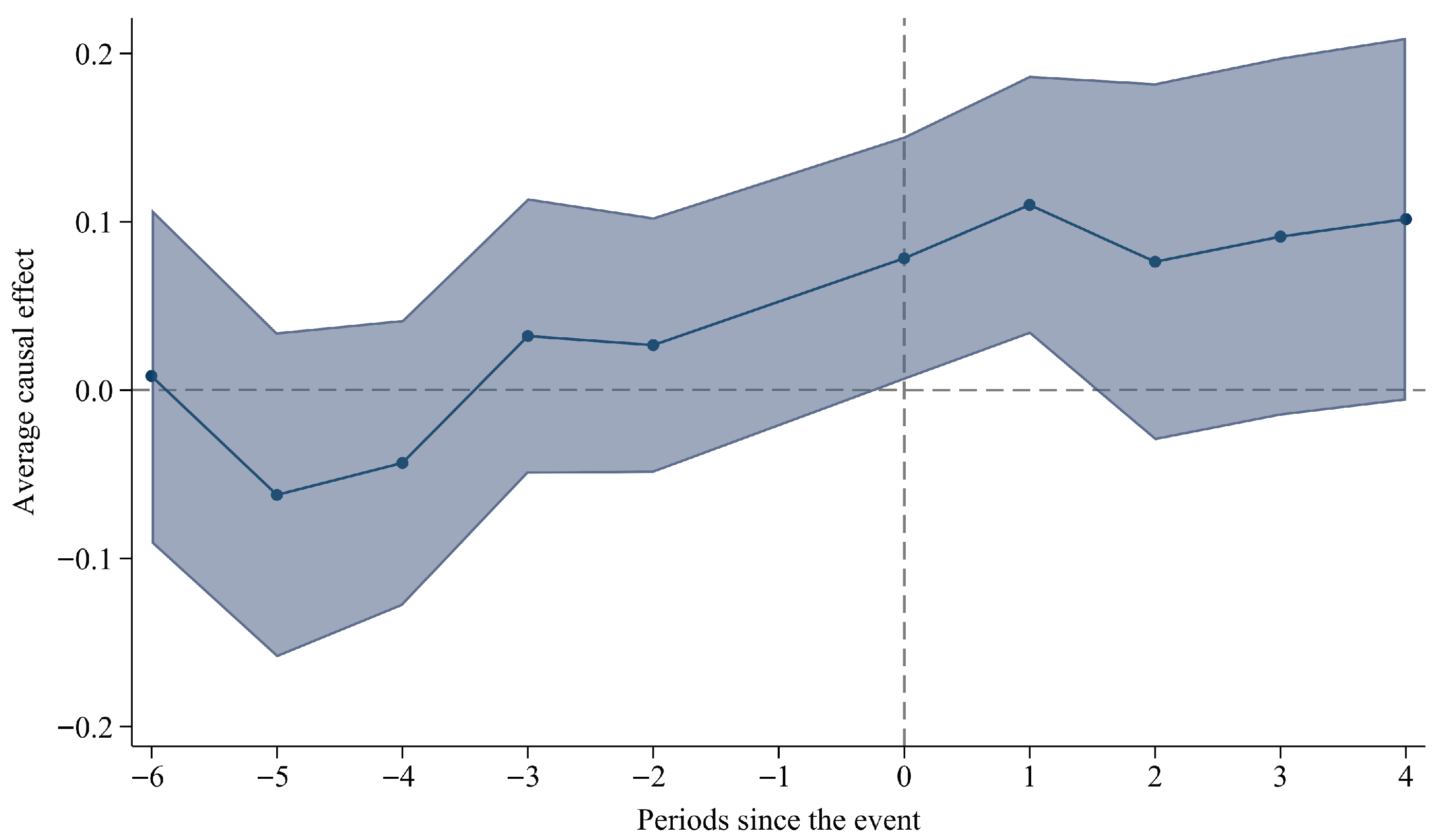

Section 4 reports the main empirical results, including baseline estimates and robustness checks.

Section 5 presents the heterogeneity and mechanism analyses.

Section 6 concludes by summarising the key findings and discussing policy implications. The overall research framework is illustrated in

Figure 1.

2. Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Policy Background

Digital–intelligence is not only a defining feature of the new wave of industrialisation but also a key pathway for cultivating new productive forces. National governments play a decisive role in advancing the digital–intelligence agenda. In the United States, the National Strategic Plan for Advanced Manufacturing and the Industrial Internet Consortium provide strong policy support for the research, development, and application of intelligent manufacturing technologies. Germany, centred on its Industry 4.0 initiative, continues to refine its digital-transformation blueprint and has issued the Digital Strategy 2025. Meanwhile, Japan, guided by the Society 5.0 vision, integrates intelligent manufacturing with cutting-edge technologies such as the Internet of Things and artificial intelligence to comprehensively advance manufacturing digitalisation.

With its relatively well-developed digital–intelligence infrastructure, China regards corporate digital–intelligence transformation as an inevitable response to ongoing technological change. As early as 2015, the State Council issued the Action Plan for Promoting Big Data Development, setting out a top-down, national-level blueprint for the production, circulation, and utilisation of data. Data has emerged as the most dynamic factor of production in the third wave of the scientific-and-technological revolution and as the core strategic resource for building a Digital China. To reinforce the integration of regional data infrastructure, enhance the agglomeration and value-creation capacity of data resources, and narrow regional development gaps, the central government has successively approved the establishment of the NBD. Between 2015 and 2016, two batches comprising nine provinces were designated as pilot zones. By developing core big-data technologies, building data-exchange platforms, and institutionalising data openness and sharing, these pilot zones have dismantled long-standing data barriers and injected fresh momentum into the digital-driven and intelligence-driven upgrading of traditional industries.

In 2017, the New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan designated AI as the core driver of a new round of industrial transformation and systematically outlined the corresponding key tasks and strategic objectives. Subsequently, in March 2019, the State Council issued the Guiding Opinions on Promoting the Deep Integration of Artificial Intelligence and the Real Economy, emphasising the imperative to seize AI-related opportunities and to integrate AI deeply with the real economy in order to strengthen China’s scientific and technological capacity and industrial competitiveness, thereby securing the commanding heights of the global industrial revolution. To accelerate AI innovation and its application, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology approved multiple batches of National AI Innovation and Application Pilot Zones, bringing the total to 11 by the end of 2022. With a focus on industrial planning, infrastructure development, and institutional innovation, these pilot zones have undertaken pioneering initiatives, invigorated corporate innovation, addressed critical core technological chokepoints, and fostered a next-generation AI industrial ecosystem.

2.2. Theoretical Analysis

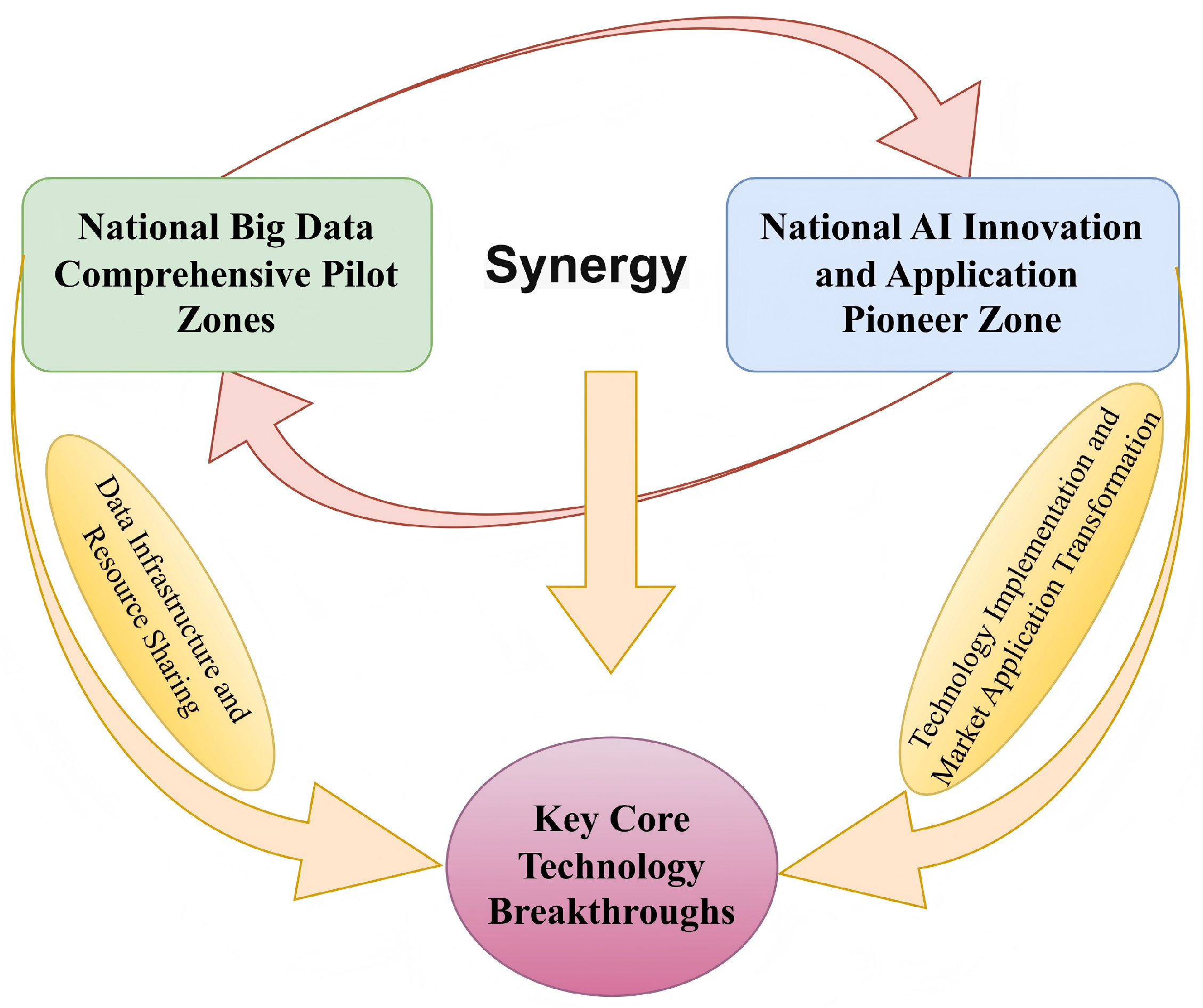

As global technological competition intensifies, achieving breakthroughs in key core technologies has become a strategic yardstick for a nation’s innovation capacity and industrial security. In response, the Chinese government has introduced two major digital–intelligence industrial policies in succession, the NBD and the AIP, whose policy content is highly complementary. The NBD agenda concentrates on institutional arrangements and infrastructure that transform data into a productive asset, whereas the AIP agenda emphasises algorithmic capability and the deployment of AI in real-world settings and its integration with industrial systems. Together, they form a coherent policy package in which data foundations and application-oriented intelligence mutually reinforce one another. In this context, this paper examines whether such digital–intelligence policy synergy catalyses firms’ breakthroughs in key core technologies and clarifies both the direct effects and the combined mechanisms through which these policies operate.

2.2.1. Direct Effects

A defining feature of the digital–intelligence transformation is the pervasive integration of information and data across economic systems [

20]. Data have increasingly been recognised as a core factor of production, alongside capital and labour [

21,

22]. Building on Schumpeter’s theory of innovation—which emphasises that new combinations of production factors generate creative destruction—the digital–intelligence transformation reframes data as a productive input. This reframing creates external conditions that facilitate firms’ breakthroughs in key core technologies while also improving the efficiency and reliability of their innovation processes [

23,

24].

The synergistic effect of digital–intelligence policy on firms’ technological breakthroughs stems from the coordinated efforts of these policies to reduce costs and improve efficiency. These benefits are achieved through both the provision of factor inputs and institutional support. Specifically, the NBD policy prioritises the development of high-performance data centres, cloud-computing platforms, and unified data-governance frameworks. This approach lowers firms’ fixed costs of data acquisition, storage, and processing. Concurrently, the AIP adopts an application-led approach and promotes open scenarios, offering real-world pilot platforms for intelligent algorithms, while combining fiscal subsidies with challenge-based prize incentives to accelerate the translation of R&D into industrial deployment [

25]. By harnessing the resource and institutional externalities generated by this policy synergy, firms can overturn entrenched technological and market paradigms, reduce R&D expenditures and market uncertainty, and thereby accelerate key core technology breakthroughs. The direct-impact pathway is illustrated in

Figure 2. Accordingly, this study proposes the following Research Hypothesis 1:

H1. Digital–intelligence policy synergy significantly promotes firms’ key core technology breakthroughs.

Figure 2.

Direct effect diagram.

Figure 2.

Direct effect diagram.

2.2.2. Mechanisms of Impact

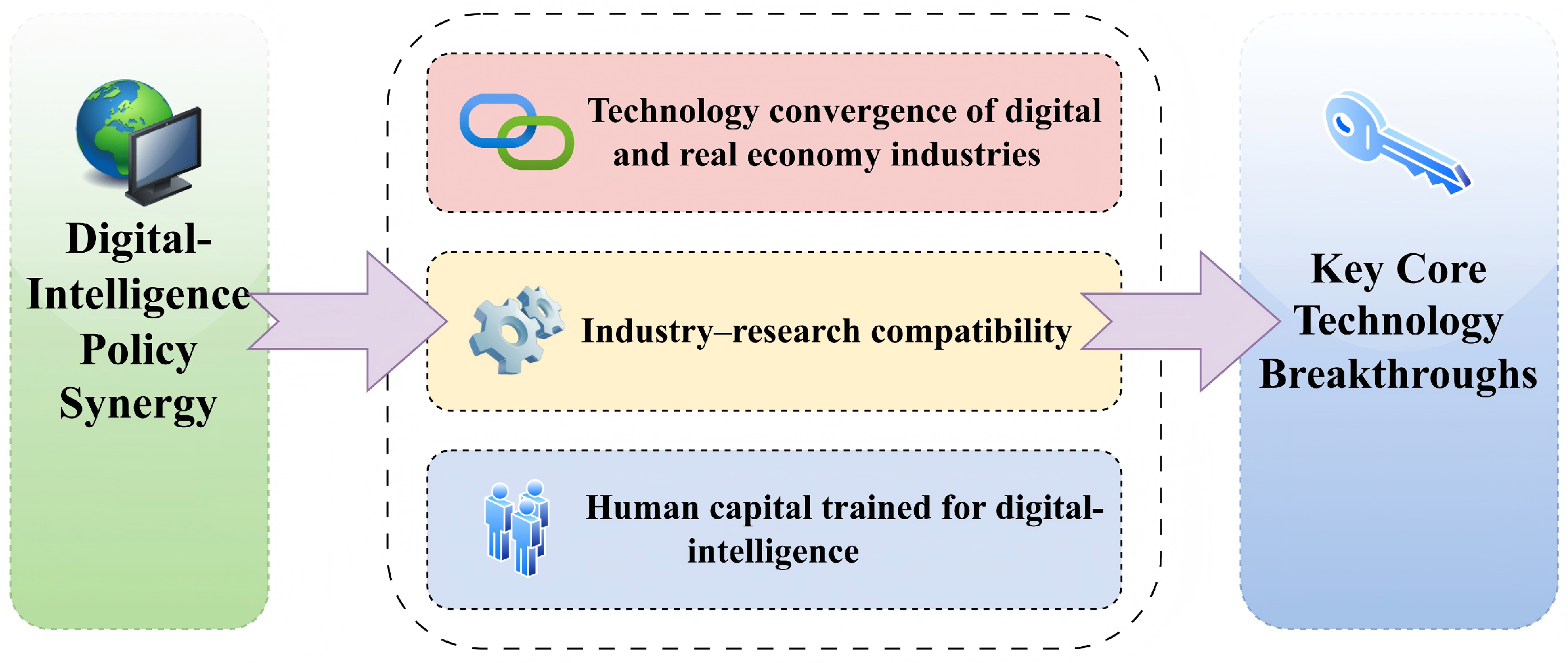

In our framework, the proposed mechanisms are conceptualised as parallel channels through which digital–intelligent policy synergy can affect firms’ key core technology breakthroughs.

Within the channel of technology convergence between the digital economy and the real economy, the NBD seeks to unlock the productive potential of data by accelerating the integration of big data with traditional sectors, thereby injecting new momentum into the real economy. In parallel, the AIP strengthens the fusion of AI and the real economy by promoting the application and diffusion of intelligent technologies and products across manufacturing, logistics, and service industries. Taken together, these complementary policies have substantially advanced digital–real-economy convergence, broken down information silos, and enabled firms to use real-time data feedback and seamless information exchange to rapidly identify technical chokepoints and implement targeted solutions. Moreover, technological convergence can create new value [

26], while digital convergence increases knowledge diversity [

27], thereby releasing resources for a wider set of innovation activities and accelerating firms’ key core technology breakthroughs. Accordingly, we propose the following Research Hypothesis 2:

H2. Technology convergence of digital and real economy industries mediates the positive effect of digital–intelligence policy synergy on firms’ key core technology breakthroughs.

Through the channel of industry–research compatibility, the NBD has reduced data fragmentation by advancing big-data integration, data openness, and the development of industrial big-data applications. These efforts help firms overcome data-collection chokepoints and deploy closed-loop applications across the R&D process, thereby cutting data-acquisition costs and bringing technological development into closer alignment with industrial demand. In parallel, the AIP strengthens application orientation by prioritising breakthroughs in foundational core technologies—such as AI chips and intelligent software—to build a secure and reliable industrial ecosystem and encourage firms to intensify R&D investment in AI and related domains [

28]. Increased R&D spending enhances firms’ technological capabilities and innovation performance [

29], which further reinforces production–research alignment. Stronger alignment reduces trial-and-error costs, mitigates commercialisation risk, shortens R&D cycles, improves coordination between innovation and industrial chains, and raises production efficiency, thereby jointly accelerating key core technology breakthroughs. Accordingly, we posit the following Research Hypothesis 3:

H3. Industry–research compatibility mediates the positive effect of digital–intelligence policy synergy on firms’ key core technology breakthroughs.

Along the optimised digital–intelligence human-capital channel, the NBD aims to cultivate a new generation of big-data professionals by incentivising firms, universities, and research institutes to jointly establish pilot zones. Big data, in turn, helps reduce information asymmetries, improves the effectiveness of education and training, raises workforce skill levels [

30,

31], and increases the share of highly skilled labour [

32], thereby strengthening the digital–intelligence talent pool. Concurrently, the AIP leverages technological and talent advantages through targeted personnel-support measures: AI has boosted employment rates [

33], expanded the pool of digital–intelligence workers, promoted skill upgrading, and accelerated the accumulation of firm-level human capital for digital–intelligence [

34,

35]. Collectively, these developments improve firms’ internal labour structures. Optimised human capital trained for digital–intelligence therefore facilitates key core technology breakthroughs. First, the agglomeration of talent enhances team quality and collaborative capacity, enabling firms to overcome chokepoints. Second, a higher proportion of digital–intelligence workers often yields flatter organisational hierarchies, thereby boosting the efficiency of R&D in key core technologies. The indirect-impact pathway is illustrated in

Figure 3. Accordingly, we propose the following Research Hypothesis 4:

H4. Optimised human capital trained for digital–intelligence mediates the positive effect of digital–intelligence policy synergy on firms’ key core technology breakthroughs.

Figure 3.

Influence mechanism diagram.

Figure 3.

Influence mechanism diagram.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Conclusions and Policy Implications

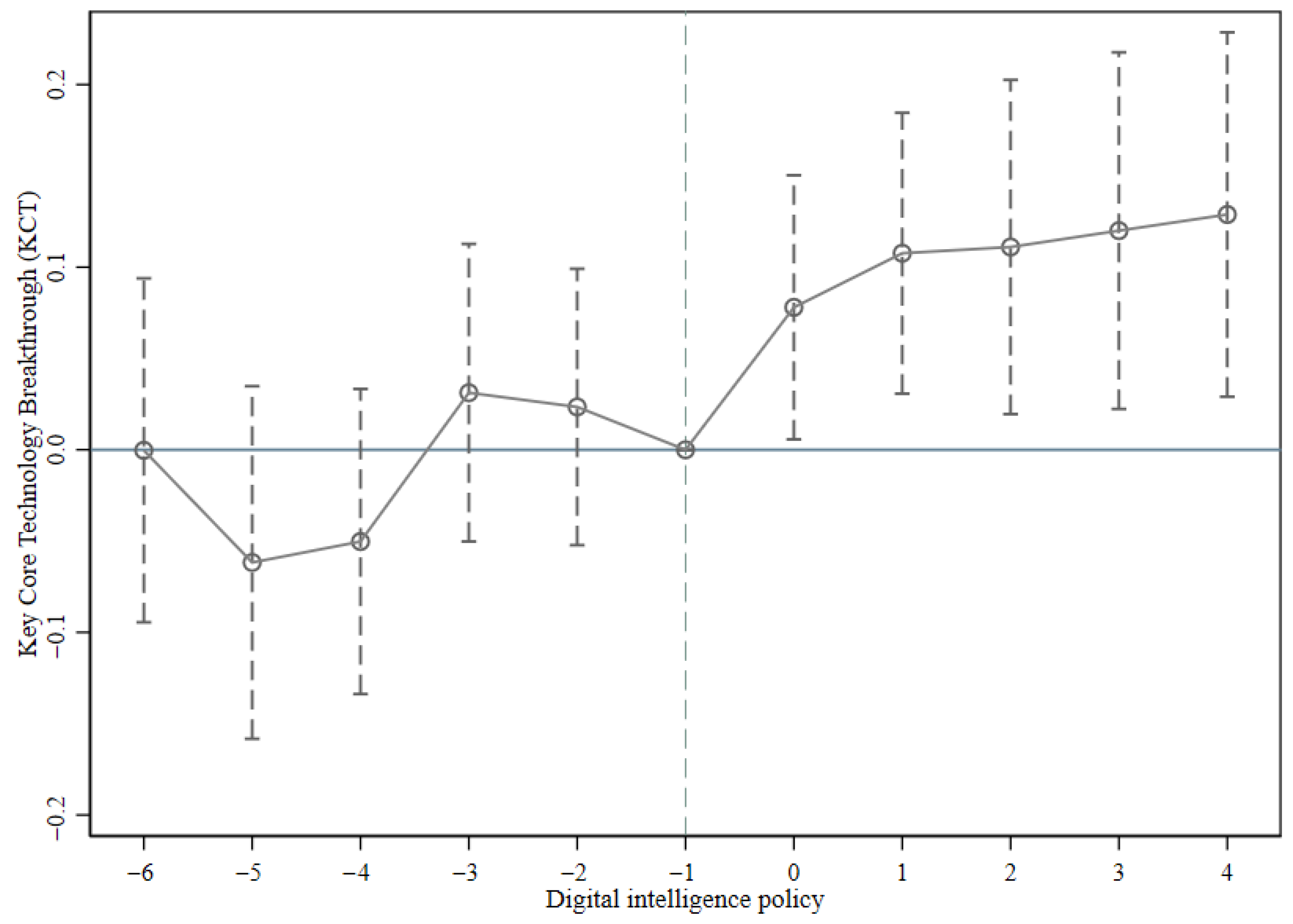

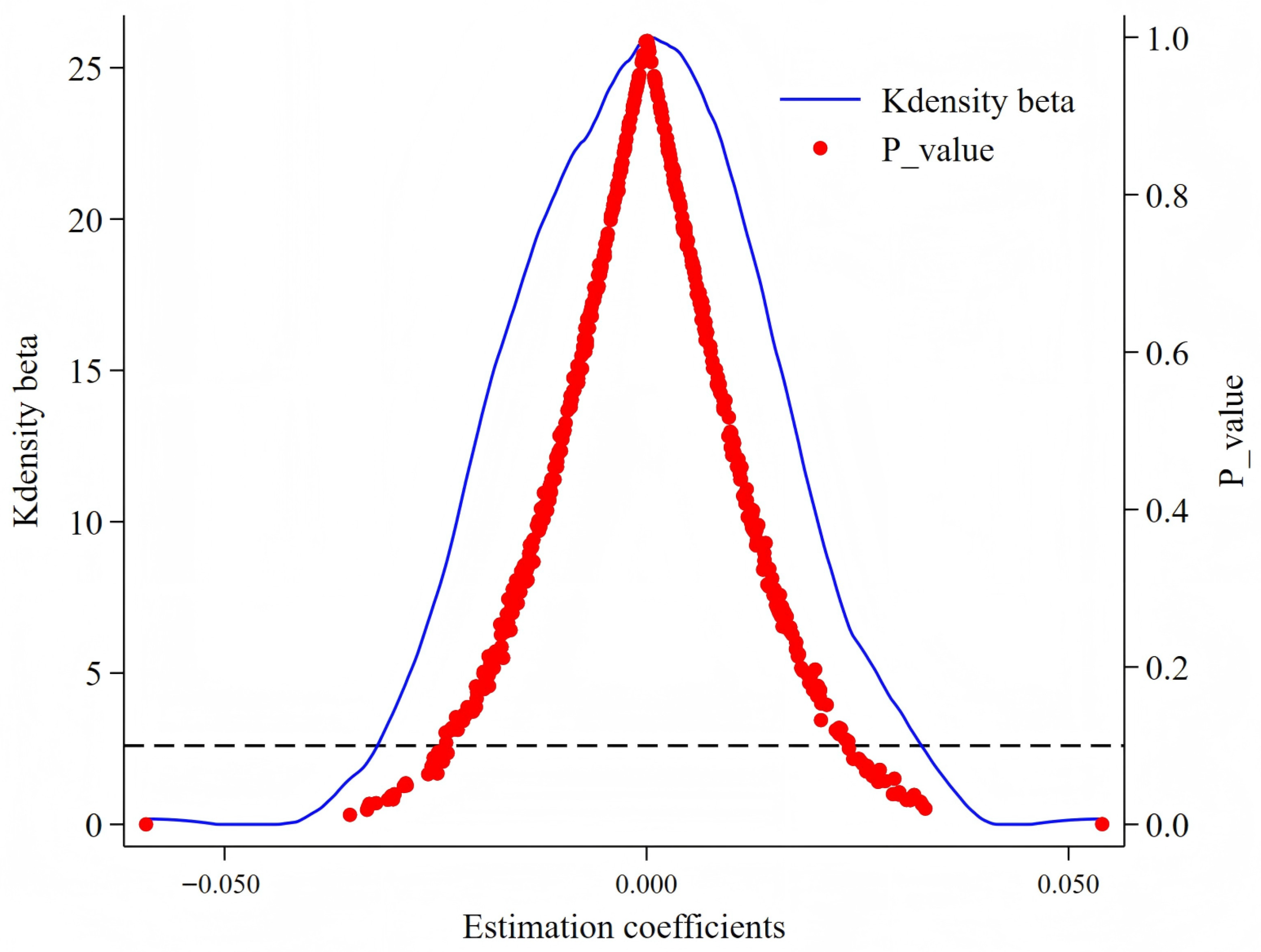

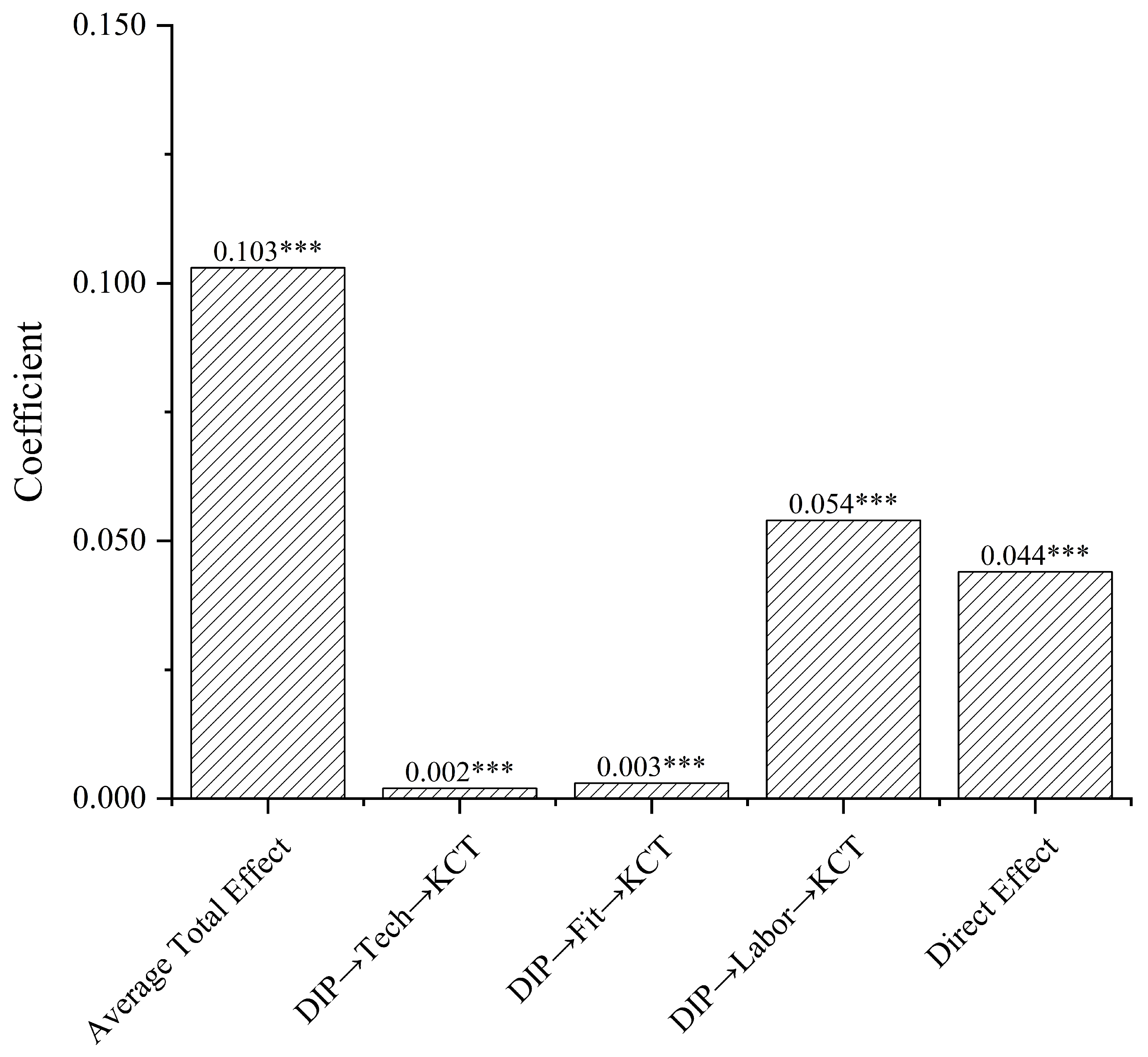

Taking the quasi-natural experiment of NBD and AIP as the setting, this paper employs panel data on A-share listed firms for 2011–2023 to examine how the synergy of digital–intelligence policy affects key core technology breakthroughs. The main findings are as follows. (1) Digital–intelligence policy synergy significantly promotes firms’ key core technology breakthroughs. (2) Mechanism analysis shows that the policies operates chiefly through three channels: technology convergence of digital and real economy industries, industry–research compatibility, and optimised human capital trained for digital–intelligence. (3) Heterogeneity analysis indicates that the policies’ effects are more pronounced for state-owned firms, firms in strategic emerging industries, and firms located in regions with stronger intellectual-property protection.

On this basis, the paper offers the following policy recommendations:

- (1)

Strengthen the coordination framework for digital–intelligence policy. Empirical evidence shows that coherently planned digital–intelligence policy facilitates firms’ breakthroughs in key core technologies. Accordingly, policymakers should prioritise cross-instrument consistency and sequencing so that computing infrastructure, data governance, algorithmic innovation, and complementary fiscal measures are mutually reinforcing. More forward-looking countries may emulate China’s pilot-zone model by initially establishing high-performance computing centres, sector-specific data spaces, and open-algorithm platforms in regions endowed with industrial and talent agglomerations, supplemented by fiscal subsidies and ancillary policy instruments. This phased strategy provides economies at varying development stages with a pathway from localised pilots to nationwide implementation, thereby lowering uncertainty and large-scale investment costs.

- (2)

Establish integration platforms that fuse digital resources with physical technologies. Our results indicate that diffusing digital-industry knowledge into the real economy is the primary channel through which the policy operates. This implies that the policy’s effectiveness hinges on reducing barriers to cross-organisational knowledge recombination and application in manufacturing and other real-economy settings. Policymakers should encourage platform firms and leading manufacturers to co-develop cross-industry data pools and shared R&D facilities while enabling research institutions and user firms to match needs with outputs on a unified platform. Competitive project grants and ex-post subsidies that reward cross-domain collaboration can substantially improve technology-transfer efficiency. This approach offers a scalable template for industrial digitalisation that can be adapted to local industrial structures to accelerate digital–intelligence upgrading.

- (3)

Reinforce production–research coupling and optimise talent composition. The evidence suggests that close alignment between production and research is essential for achieving key core technology breakthroughs. Governments can use R&D super-deductions, joint-laboratory funding, and training subsidies to guide universities, institutes, and firms in co-developing technology roadmaps, thereby embedding research outputs into production more rapidly. In parallel, a training system that integrates vocational education with on-the-job upskilling should be strengthened to support flexible allocation of scientific and digital–intelligence talent. This integrated academia–industry model provides a practical pathway to improve innovation efficiency and alleviate talent-structure mismatches.

- (4)

Provide differentiated support to expand policy coverage. Heterogeneity analyses indicate that ownership, strategic orientation, and regional institutional conditions materially shape policy effectiveness. Policymakers could (I) provide interest-subsidised loans, tax relief, and equity injections for privately owned firms facing financing constraints; (II) incentivise digital–intelligence upgrading and cross-industry collaboration in technologically less mature sectors; and (III) expand public technical services and strengthen market-based exit mechanisms in regions with weak intellectual-property protection. Layered support tailored to firm type and regional context can help spread policy benefits more evenly across diverse local economies. From a technology-management perspective, these heterogeneous effects underscore the contingency role of governance structure and strategic orientation in shaping firms’ absorptive capacity and the returns to digital–intelligence investments.

- (5)

Promote international co-governance of the digital–intelligence economy. China’s pilot experience underscores that institutional certainty is essential for amplifying digital–intelligence policy effects. Consistent with this, our findings suggest that clearer and more predictable institutional arrangements strengthen firms’ incentives to invest in and coordinate around key core technology innovation. To lower the cost of cross-border R&D and technology exchange, countries should reinforce multilateral or regional governance of data flows, technical standards, investment rules, and intellectual-property rights, promoting mutual recognition of review procedures, interoperability of compliance requirements, and linkage of dispute-settlement mechanisms. A unified and transparent rule set can raise expected returns on cross-border cooperation, thereby spurring global investment in critical core technologies and providing a firmer institutional foundation for high-quality growth of the digital–intelligence economy. From a technology-management perspective, our study links institutional coordination to firms’ alliance governance and knowledge integration, clarifying how external rule environments shape breakthrough-oriented innovation outcomes.

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

Our measure of firms’ key core technology breakthroughs is constructed primarily using information from policy documents and patent classifications. This strategy is motivated by the broad coverage and high availability of patent data, and by the fact that patent classification systems can, to some extent, map inventive outputs into relatively stable technology domains. As a result, they offer a tractable quantitative basis for large-sample, long-horizon evaluations of technological progress. Nevertheless, we explicitly acknowledge that a patent-classification-based indicator is not a perfect representation of key core technology breakthroughs.

Specifically, this proxy may be subject to several limitations. First, patent classifications inevitably involve noise and blurred technological boundaries: a single invention can span multiple technological trajectories, while classification labels may not fully reflect its technological centrality or disruptive potential, thereby introducing measurement error. Second, patents primarily capture codified and publicly disclosed knowledge and therefore may fail to cover pivotal advances embodied in process improvements, engineering integration, iterative software and algorithm development, or trade secrets. This concern is particularly salient in the context of digital–intelligent convergence, where some consequential innovations may not be patented. Third, patenting propensities differ systematically across industries, firm types, and regions, and policy interventions may also alter firms’ filing and disclosure incentives. Consequently, changes in patent counts or classification distributions are not necessarily equivalent to genuine improvements in underlying technological capability. Fourth, non-trivial lags from application to grant, publication, and subsequent citation, together with possible updates to classifications and quality-related information, can create timing misalignment, making short-run measurement more sensitive to reporting windows and administrative procedures.

Future research may improve measurement validity by introducing novelty indicators that more closely align with the conceptual content of key core technology breakthroughs on top of classification-based identification, and by triangulating patent-based measures with other observable signals of technological progress. Such multi-source validation would allow a more comprehensive characterisation of firms’ key core technology breakthroughs.