Abstract

Debates relating to the sustainability of the environment have emerged as a major goal of the global agenda in recent years. As a result, this research examines the impact of outward foreign direct investment (OFDI) on carbon dioxide emissions (CO2) in Turkey from 1985 to 2022, using the autoregressive distributed lag model (ARDL) and frequency domain causality analysis (FDCA). In addition, economic growth (GDP) and trade in services (TROP) were used as control variables because they capture two big ways the economy interacts with environment. The empirical results are as follows: (i) The bounds test confirms a long-run association among the variables. (ii) The ARDL result confirms that in the long and short run, OFDI and GDP increase CO2 in Turkey, while TROP contributes to the quality of the environment. (iii) The FDCA demonstrates that OFDI Granger causes CO2 in the short and medium term, while TROP Granger causes CO2 in the short, medium, and long-term. Based on these results, policies are recommended for implementation.

1. Introduction

The concept of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) has continued to increase in momentum and importance. This is because of the concrete idea of achieving present developmental goals without jeopardizing the chances of future generations. One of the goals is geared towards tackling the issue of climate change, caused by rising greenhouse gases (GHGs). One of the GHGs that harms the environment the most is carbon dioxide emissions (CO2). The burning of fossil fuels, industrial activities, and deforestation are the main sources of CO2 [1]. If CO2 can contribute to the degradation of the environment, the factors that drive or reduce it need to be investigated.

To achieve environmental quality (EQ), diverse factors come into play, such as environmental policies [2], the level of urbanization [3,4], population size [5], clean energy consumption [6,7], financial development [8,9], and technological innovation [10], among other factors. More specifically, it has been established that foreign direct investment (FDI) can improve the quality of the environment [11,12]. Ref. [13] stated that globally, FDI flows have significantly expanded, particularly in the past 20 years. FDI can come in the form of inflows or outflows. FDI inflows (IFDI) are investments coming into a country, while OFDI refers to investments going into other economies. This research focuses on OFDI because of the gap in existing studies regarding this topic.

The combination of ownership, location, and internalization benefits offered by a nation’s firms may vary across the country’s path of economic progress, according to the most recent advances in economic theory clarifying the OFDI positions of nations [14,15]. If it is acknowledged that a nation’s businesses’ inclination to invest overseas depends on their capacity to obtain and use assets that generate money domestically, then the frequency of foreign engagement will increase with this capacity [15]. As a result, the inclination to invest overseas can be hypothesized as a function of such endowments [15]. Ref. [16] exclaimed that in the home country, OFDI could result in reverse technology transfer and advance domestic technology. Ref. [17] further opined that OFDI could promote green innovation. Ref. [18] suggested that, through spillover effects, supporting viable businesses to participate in ODFI initiatives could effectively encourage efforts to reduce pollution. However, in contrast, OFDI can contribute to the degradation of the environment through the scale effect.

OFDI in various developed economies has been investigated, but it has been neglected emerging economies, such as Turkey. According to [19], Turkey’s location at the meeting point of three continents—Africa, Europe, and Asia—represents a very special circumstance that contributes to the development of several advantages for the home country. For example, Turkey’s geographical, organizational, and political closeness to Europe enabled it to join the Customs Union (CU) while pursuing full EU membership status. In a similar vein, Turkey maintains cultural connections with the recently independent Central Asian nations. It has a sizable diaspora that resides in the EU and other countries. Turkish OFDI stock is expanding quickly in these areas. Turkey can serve as an excellent example of the current factors influencing OFDI, which can contribute to EQ or degrade the environment of the home country. In December 2024, Turkey’s direct investment abroad increased by USD 834 million, and its foreign portfolio investment rose by USD 4.4 billion. In January 2025, Turkey’s FDI grew by USD 1.4 billion, up from USD 2 billion the month before [20]. Turkey is also a trillion–dollar economy [21], which makes it a significant player in the global economy.

It is important to state that the service sector is a significant part of FDI. Ref. [22] opined that, in addition to being potential sources of exports, related jobs, and household income, services are important for achieving the SDGs because many of them depend on improving the performance of a number of particular service sectors in nations that are developing. Reaching the SDGs is mostly a service-oriented mission. Increasing the capability and efficiency of a variety of service activities, such as transportation, distribution, logistics, ICT, vocational training, medical services, and so on, will be necessary to eradicate poverty and hunger, improve health and educational outcomes, or lessen regional disparities.

Based on the aforementioned arguments, this study uses the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) model and frequency domain causality approach (FDCA) to examine the effects of OFDI, TROP, and economic growth (GDP) on CO2 in Turkey from 1985 to 2022. Because Turkey has a high level of OFDI, which suggests that Turkish businesses are expanding internationally, it is crucial to examine the links between these variables. This inquiry aids in determining whether Turkey is importing greener technologies from overseas markets or exporting its carbon-intensive operations. Additionally, the Turkish economy is heavily reliant on trade services, particularly tourism and transportation, which continue to have a large carbon footprint because of the energy requirements of aviation and hospitality. By analyzing these factors alongside economic progress, stakeholders can determine whether Turkey has reached a tipping point where it can continue to grow without increasing CO2 levels.

Based on the following discussions, the gaps and contributions of this study are as follows: First, the literature on OFDI and EQ is quite scanty, as existing studies have focused on the dynamics of IFDI [23,24]. Second, prior research on FDI has mostly concentrated on how it affects the host country’s environment, neglecting the impact on the home country’s environment, with very few studies having used Turkey as a case study. Third, in addition to the ARDL method employed, because of its application to small-sample-size data [25], this research also used the FDCA of [26]. The FDCA assesses the degree of a particular variation in a time series [27]. Seasonal changes can be eliminated from the small-sample data using the FDCA [28]. Furthermore, the FDCA allows for the detection of causality between factors at short, medium, and long frequencies as well as the distinction of non-linearity and causality stages. Lastly, the outcome of this research has important practical ramifications for comprehending how OFDI affects the environment. The outcome confirms that OFDI and GDP increase CO2, while TROP reduces CO2.

2. Literature Review

Using a single and simultaneous equation model, ref. [29] established that China’s OFDI has enhanced economic scale (scale impact), which has led to an increase in domestic ecological pollution. On the other hand, OFDI’s reverse technology spillover effect has reduced domestic ecological degradation by optimizing the domestic industrial structure (composition impact) and raising the level of domestic technology (technical effect). The implication of this is that OFDI can both drive ecological degradation and contribute to EQ. Using the ARDL approach, ref. [30] confirmed the EKC hypothesis for the MENA region. Additionally, the empirical findings support the “pollution haven” hypothesis, which holds that wealthy countries’ polluting industrial operations relocate to developing nations with laxer environmental laws. Ref. [31] explained that OFDI could spur CO2 emissions.

In BRICS economies, using the FMOLS, DOLS, and PMG methodologies, ref. [32] established that the empirical findings support the EKC hypothesis, suggesting that energy use and OFDI contribute to the long–term expansion of greener technologies to improve the environmental conditions of host nations and validate the existence of an inverted U-shaped association. Ref. [33] opined that regulating the environment (ER) greatly increases OFDI, and these ER-driven OFDI flows are primarily directed toward nations with weaker environmental laws and that are closer geographically and culturally to the home country.

For developing economies, employing the SYS–GMM approach, ref. [34] revealed that domestic institutions support the reverse technology spillover effects of OFDI to increase its efficacy in reducing CO2 through eco-friendly technologies. High levels of human capital, however, have been shown to boost the quality of domestic institutions, which in turn encourages more FDI spillover that enhances EQ. In line with the reverse transfer of knowledge approach, ref. [35] discovered that enterprises’ ecological performance increases following the start of OFDI. Additionally, the study noted that firms experience an additional boost in ecological performance when the OFDI host nations are advanced, have more stringent laws pertaining to the environment, and exhibit higher standards for the future-oriented dimensions of national culture.

In Vietnam, ref. [36] ascertained that OFDI has no association with CO2. Although GDP per capita has a negative long-term correlation, this is consistent with Vietnam’s 2021–2030 National Climate Strategy, which places a strong emphasis on fostering the expansion of GDP through low-carbon industries. In Turkey, using the ARDL approach, ref. [13] found that economic expansion significantly impacts CO2, while FDI has a positive but negligible influence. Furthermore, it is observed that the long- and short-run results are comparable. In newly industrialized economies, ref. [37] revealed that increasing OFDI effectively lowers carbon footprints in Mexico and Turkey, while increased well-being of people lowers pollution in the Philippines. Additionally, trade openness lowers emissions in China and Malaysia. According to panel analysis, OFDI’s moderating effect on human well-being promotes a sustainable ecosystem. Generally, ref. [38] also argued that FDI spurs CO2 emissions in Turkey.

In existing studies, it has been confirmed that economic expansion can drive ecological degradation [39,40,41,42]. This assertion is also true for the Turkish economy [43,44]. Ref. [45], however, found that economic progress drives EQ.

In terms of the TROP and EQ nexus, ref. [46] stated that countries’ trade limitations on services may have a negative impact on the execution of ecological initiatives through the formation of specialized businesses with commercial presences outside those countries. Ref. [47] opined that carbon efficiency is increased via trade in services. Exports saw a larger increase in carbon efficiency as a result of trade in services, whereas imports had the opposite effect. Ref. [22] established that a number of the SDGs rely on how well the services economy performs. In addition, the performance of the service industry can be improved by loosening trade restrictions. Ref. [48] argued that trading as a whole raises CO2, while trading in commodities raises CO2 more than trade in services.

According to the examined literature, there is a dearth of research on OFDI, particularly for a nation like Turkey, which necessitates further study. Additionally, the research reveals inconsistent results on the relationship between OFDI and CO2. While some research contends that OFDI drives EQ, others contend that OFDI is the primary cause of environmental deterioration. These discrepancies also call for additional research. Finally, this study applied FDCA as an addition to the methods used in previous studies.

3. Theoretical Framework

This research employed the theory of [49,50] to examine the impact of OFDI on CO2, and this can be broken down into the scale, composite, and technique effects. The scale effect of OFDI examines how the home country is affected due to continuous pollution activities [29]. This effect, as expressed by [51], is a pollution-causing factor that quantifies the degree of ecological degradation that results from merely scaling up the economy. Through the return on investment and the introduction of new technologies, OFDI has a reciprocal impact on the home country’s economic expansion and CO2 emissions. The composition effect shows how a nation’s industrial mix at a certain scale of production relates to its performance regarding the environment [52]. Put another way, a nation’s pollution levels will be high if its industrial structure is characterized by pollution-intensive industries, whereas it will be low if its industrial architecture is controlled by clean-intensive industries. The use of environmentally sound technologies leading to a beneficial spillover effect is known as the “technique effect” [51]. Via OFDI, businesses in the investing nation can have access to the resources and innovative technologies of the host nation, eventually facilitating the transfer of these innovations from the host nation to the home nation. Both direct and indirect effects are included in the technique effect. The transfer of cutting-edge ecological technology through cooperation and international exchange of technological advances is known as the “direct technique effect” [53]. In contrast, the “indirect technique effect” occurs when FDI boosts economic expansion, which in turn increases wealth and the demand for cleaner environments, which may lead to the deployment of greener technologies [51].

Other theories that are relevant to the discussions of this research are the “pollution haven hypothesis” and “pollution halo hypothesis.” According to the “pollution haven hypothesis,” wealthy nations frequently relocate their highly polluting businesses or industries to less-developed nations in the context of economic globalization, which has a detrimental effect on the environment of those nations. These developing nations become oases of pollution because they significantly increase their pollutant emissions, despite the fact that the movement of pollution-intensive businesses raises their degree of specialization, growth in production, and income [54]. Nonetheless, ref. [55] proposed the “pollution halo hypothesis,” which holds that the introduction of foreign capital produces more sophisticated management techniques, concepts, and effective technology, all of which have a positive effect on the environment. Up until now, there has not been much agreement on the opposing conclusions of the “pollution haven” and “pollution halo” hypotheses, both of which are supported by facts [29].

In summary, the Turkish economy’s ecological trajectory is determined by the tension between the scale and technology effects. While the rapid expansion of the industrial sector has historically resulted in a pro-cyclical increase in emissions, Turkey’s increasing trade openness acts as an amplifier for the pollution halo effect. By incorporating cleaner technical spillovers from partner countries, Turkey has the potential to overcome the structural emissions inherent in its manufacturing-intensive makeup.

4. Data and Methodology

4.1. Data

The data employed in this research are from 1985 to 2022. The variable used to capture the sustainability of the environment is carbon dioxide emissions (CO2), while the independent variables employed include foreign direct investment, net outflows (percentage of GDP) (OFDI), trade in services (percentage of GDP) (TROP), and GDP (constant 2015 USD) (GDP). It is important to state that TROP and GDP are used as control variables because they play a very crucial role in determining the quality of the environment. All variables were sourced from [21]. The integration of OFDI, TROP, and GDP as CO2 determinants is established in their capacity to shape Turkey’s industrial and environmental landscape. Table 1 shows the overview of the variables.

Table 1.

Overview of the variables.

Furthermore, the model of this study, adopted from the studies of [11,29,56], is presented in Equation (1) and transformed to log form in Equation (2).

The intercept can be denoted as ; represents the independent variables’ coefficients; t is time; and the error term is . Based on the reviewed literature and theoretical foundation, this study hypothesizes that OFDI will contribute to ecological degradation , TROP will drive EQ , and GDP will degrade the environment .

4.2. Methodology

The technique employed is the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) model proposed by [57]. Ref. [27] stated that when the data set is either I(0), I(1), or a combination of I(0) and I(1), the ARDL technique has the advantage of allowing for the joint analysis of short- and long-term linkages; however, it is incompatible with I(2) variables. This method is more advantageous to studies requiring stringent stationarity conditions [58]. In addition, this approach is very suitable for small-sample-size data investigations. The ARDL long- and short-run equation can be seen in Equation (3).

The parameters for the short-run coefficients are represented by , while those of the long-run coefficients are shown as . ECT is the error correction term, which shows the rate at which the economy moves back to equilibrium. Furthermore, this research employed the FDCA proposed by [26]. The FDCA assesses the degree of a particular variation in a time series, whereas the “time-domain” approach tells us where a certain change occurs within a time series [27]. Seasonal changes can be eliminated from the small-sample data thanks to the FDCA [28]. Furthermore, the FDCA allows for the detection of causality between factors at short, medium, and long frequencies as well as the distinction of non-linearity and causality stages [59]. Lastly, using the FDCA will tell us when and how consistently OFDI drives CO2.

5. Analysis and Discussions

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

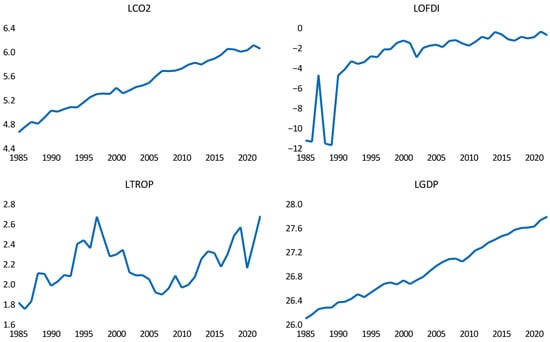

From Table 2, it is evident that the highest mean and median values can be seen in the LGDP variable, with the values 26.93181 and 26.85473, respectively. The next, in terms of high values, is LCO2. This pattern is also observed in the maximum and minimum values. For skewness, LCO2 and LOFDI are skewed negatively at −0.149534 and −2.036834, respectively, while LTROP and LGDP are skewed positively at 0.317885 and 0.164348, respectively. LCO2, LTROP, and LGDP are platykurtic because the kurtosis values are below 3, while LOFDI is leptokurtic because the value is above 3. Aside from LOFDI, which demonstrates a non-normal distribution nature, every other variable displays normal distribution. The trends and patterns of the variables are presented in Figure 1. LCO2 and LGDP evidently moved in an upward trend, while fluctuations are observed in LOFDI and LTROP.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

Figure 1.

Trends and patterns of variables.

5.2. Correlation Matrix

In Table 3, the correlation matrix shows that LOFDI, LTROP, and LGDP are positively correlated with CO2. It is essential to state that these correlations are statistically significant.

Table 3.

Correlation matrix.

5.3. Unit Root Analysis

The results presented in Table 4 are the unit root results of [60,61]. The outcome of both tests shows that LCO2 and LOFDI are stationary at I(0), while LTROP and LGDP are stationary at I(1). This confirmation shows that the proposed methodology, which is ARDL, can be used.

Table 4.

Unit root evaluation.

5.4. Bounds Test

From the bounds test in Table 5, it is evident that there is a long-run association between the investigated variables. The F-stat value (3.966983) is more than the I(0) and I(1) bounds at the 5% and 10% significance levels.

Table 5.

Bound test.

5.5. ARDL Long- and Short-Run Outcomes

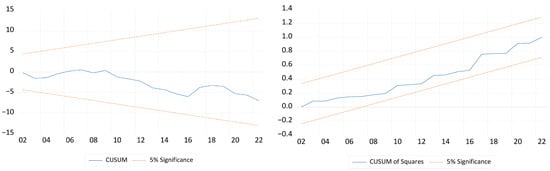

In Table 6, the outcome confirms that LOFDI and LGDP increase LCO2, while LTROP reduces LCO2. Empirically, in the long run, as LOFDI and LGDP increase by 1%, LCO2 rises by 0.02% and 0.69%, respectively. On the other hand, as LTROP increases by 1%, LCO2 is depleted by 0.25%. In the short run, as LOFDI and LGDP increase by 1%, LCO2 increases by 0.007% and 0.48%, respectively. On the contrary, LTROP reduces LCO2 by 0.07%. It is important to note that these dynamics change when the lags are taken into consideration. This can be ascribed to structural change dynamics and the deployment of cleaner technologies, which cannot be sustained. That is why in the long run, these variables move back to their original positions. Furthermore, the ECM confirms a reversal to equilibrium at 0.35%. This is the cointegrating equation in Table 6. To ensure the viability of these results and to justify the rationale of including the variables in this study’s model, the R-squared shows that 81% of LCO2 can be explained by LOFDI, LGDP, and LTROP. Furthermore, the overall model shows normality, confirms the absence of serial correlation, is homoskedastic, and is confirmed stable by the Ramsey RESET test in Table 6 and the CUSUM and CUSUMQ tests in Figure 2.

Table 6.

ARDL long- and short-run outcomes.

Figure 2.

CUSUM and CUSUMQ.

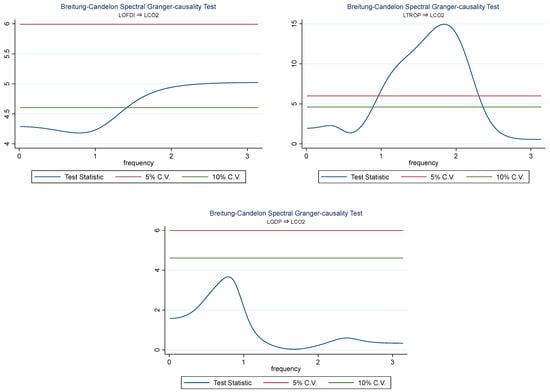

5.6. Frequency Domain Causality Approach (FDCA)

In Figure 3, the FDCA shows that LOFDI Granger causes LCO2 in the short and medium term. Furthermore, the causality between LTROP and LCO2 is significant in the short, medium, and long term. Finally, LGDP is seen not to have a significant association with LCO2.

Figure 3.

Frequency Domain Causality Approach.

5.7. Discussions

Contrary to other findings, this research asserts that OFDI can drive CO2 in Turkey. There are various reasons for this assertion. One of the factors responsible for this is structural economic reallocation. This refers to a scenario where firms in Turkey move standardized and low-energy-intensive activities to host countries, while retaining high-energy-intensive activities, such as complex manufacturing processes. Ref. [31] opined that this positive OFDI–CO2 nexus is driven by numerous legislative obstacles (stringent ecological policies) that the government has put in place to stop the flight of industrial capital. Consequently, high-polluting and high-emission businesses have not been moved out of the country by Turkey’s OFDI. An example of such policies is the adoption of the climate law, which creates the legal framework for a national emissions trading system (ETS) to help Turkey achieve its net-zero emissions goal. Additionally, the legislation establishes institutional arrangements, financing methods, and a structure for governing the climate. It further emphasizes that firms should not feel forced to relocate to countries with lower ecological standards [62]. In addition, the size of the population, the level of overall economic progress, the level of technological advancement, and ecological policies are factors that determine how OFDI impacts the environment. This relationship is supported by the studies of [13,29] and opposed by the studies of [30,36].

The empirical outcome of GDP boosting CO2 has been hypothesized. This is because Turkey still depends on fossil fuels for economic activities. According to [63], a positive GDP–CO2 nexus is driven by the goal to increase output, which requires energy use; nevertheless, the demand for unclean energy greatly exceeds the need for clean energy. Therefore, in the long run, increased utilization of energy in the quest for higher output results in higher CO2. This outcome aligns with the studies of [39,40,41] and contradicts the research of [45].

Lastly, the outcome of an inverse association between TROP and CO2 is expected. This is because services require fewer physical resources, and as a result, their expansion effectively decouples economic progress from CO2. Ref. [47] opined that the export of services could increase a country’s carbon efficiency. In addition, trade in services also aids the flow of clean technologies and management practices. This result is confirmed by the research of [22] and stands in contrast to the research of [48].

In summary, based on the theoretical foundation used in this research, the scale effect and pollution haven hypothesis are confirmed due to the exhibited relationship between OFDI, GDP, and CO2.

6. Conclusions and Policy Recommendation

6.1. Conclusions

Debates relating to the sustainability of the environment have emerged as a major goal of the global agenda in recent years. As a result, this research examines the impact of outward foreign direct investment (OFDI) on carbon dioxide emissions (CO2) in Turkey from 1985 to 2022, using the autoregressive distributed lag model (ARDL) and frequency domain causality analysis (FDCA). In addition, economic growth (GDP) and trade in services (TROP) were used as control variables because they capture two big ways the economy interacts with the environment. OFDI is considered for the Turkish economy because it turns the country’s own firms into global players. The empirical results are as follows: (i) The bounds test confirms a long-run association among the variables. (ii) The ARDL result confirms that in the long and short run, OFDI and GDP increase CO2 in Turkey, while TROP contributes to the quality of the environment. Empirically, in the long run, as OFDI and GDP increase by 1%, CO2 increases by 0.02% and 0.69%, respectively, while TROP decreases CO2 by 0.25%. In the short run, as OFDI and GDP increase by 1%, CO2 increases by 0.007% and 0.48%, respectively, while TROP decreases CO2 by 0.07%. (iii) The FDCA demonstrates that OFDI Granger causes CO2 in the short and medium term, while TROP Granger causes CO2 in the short, medium, and long term.

6.2. Policy Recommendations

First, because OFDI contributes to a country’s long-term sustainable growth, strategic OFDI policies should be formulated. In the wake of the 2025 climate law, Turkey must move beyond broad regulations and adopt frequency-specific policies. Short-term policies include green capital screening, which states that a business must demonstrate that the domestic setup phase will not surpass a certain carbon limit if it wants to move capital abroad. If it does, the money the business pays out will be subject to a temporary environmental tax. In the medium term, the Turkish government may grant a carbon credit refund to businesses that use their international profits to purchase sophisticated green technology and install it in their Turkish facilities. In the long term, the Turkish government should fully classify businesses that can be regarded as green so that they can have access to funding thorough attractive interest rates, grants, or subsidies. Ref. [33] opined that environmental regulation greatly increases OFDI. Ref. [64] stated that businesses reroute their investment capital to green innovation R&D when ecological constraints limit OFDI in highly polluting industries. This boosts competitive advantage, increases profitability, and eventually encourages OFDI. On the other hand, when ecological policies permit OFDI in highly polluting industries, businesses not only immediately minimize the release of pollutants and ameliorate local production operations, but they also use OFDI to obtain advanced green technologies and best practices globally. A positive feedback loop can be created by these newly acquired technologies and experiences, stimulating additional OFDI. Second, although GDP increases CO2 emissions, adopting eco-friendly technologies can help foster economic progress while at the same time contributing to the quality of the environment. This is called decoupling. Economic growth is achieved when Turkey reduces its reliance on expensive fossil fuel imports, allowing the country to save billions of dollars in energy costs. This further creates highly skilled green manufacturing jobs, ensuring that exports remain competitive in markets such as the EU, which now taxes carbon-intensive goods. Simultaneously, it promotes EQ by removing hazardous emissions at their source, which significantly improves human health and protects natural resources. Lastly, the trend of a positive association between TROP and EQ should be maximized by the government and all concerned stakeholders by ensuring that restrictions relating to trade service exports are reduced. In addition, significant investment should be made in digital infrastructure and skills to aid the private sector’s competitiveness.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Suggestions

This research used two control variables in analyzing the main research question. Thus, other studies can include additional control variables such as environmental policy stringency, technological and green innovation, and energy use depending on the country being studied. This means that other countries can be investigated to allow for robust policy formulation. More specifically, non–parametric econometric methods can be used, such as wavelet quantile regression, wavelet quantile correlation, and quantile-on-quantile Granger causality, because of the reliable insights they can yield about the underlying research questions.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written by A.S.A. and supervised by W.M.S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. In addition, the data are publicly available at World Bank Open Data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide Emissions |

| DOLS | Dynamic Ordinary Least Squares |

| EKC | Environmental Kuznets Curve |

| EQ | Environmental Quality |

| FMOLS | Fully Modified Ordinary Least Squares |

| GMM | Generalized Method of Moments |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technology |

| IFDI | Inward Foreign Direct Investment |

| OFDI | Outward Foreign Direct Investment |

| PMG | Pooled Mean Group |

| R&D | Research and Development |

References

- Mehmood, T.; Hassan, M.A.; Li, X.; Ashraf, A.; Rehman, S.; Bilal, M.; Obodo, R.M.; Mustafa, B.; Shaz, M.; Bibi, S. Mechanism behind sources and sinks of major anthropogenic greenhouse gases. In Climate Change Alleviation for Sustainable Progression; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 114–150. [Google Scholar]

- Degirmenci, T.; Acikgoz, F.; Guney, E.; Aydin, M. Decoupling sustainable development from environmental degradation: Insights from environmental policy stringency, renewable energy, economic growth, and load capacity factor in high-income countries. Clean. Technol. Environ. Policy 2025, 27, 2547–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, A.; Zhang, J.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, S. How to recognize and measure the impact of phasing urbanization on eco-environment quality: An empirical case study of 19 urban agglomerations in China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2025, 210, 123845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatti, W.; Majeed, M.T. Information communication technology (ICT), smart urbanization, and environmental quality: Evidence from a panel of developing and developed economies. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 366, 132925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Ajide, K.B.; Ridwan, L.I. Heterogeneous dynamic impacts of nonrenewable energy, resource rents, technology, human capital, and population on environmental quality in Sub-Saharan African countries. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 11817–11851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khoury, R.; Min Du, A.; Nasrallah, N.; Marashdeh, H.; Atayah, O.F. Towards sustainability: Examining financial, economic, and societal determinants of environmental degradation. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2025, 73, 102557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Aghazadeh, S.; Liaquat, M.; Nassani, A.A.; Sunday Eweade, B. Transforming Costa Rica’s environmental quality: The role of renewable energy, rule of law, corruption control, and foreign direct investment in building a sustainable future. Renew. Energy 2025, 239, 121993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horobet, A.; Radulescu, M.; Bouraoui, T.; Mnohoghitnei, I.; Balsalobre-Lorente, D.; Belascu, L. Financial development and environmental degradation: Insights from European countries. Appl. Econ. 2025, 57, 4679–4694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, M.; Fatima, A.; Ullah, M.R.; Huo, W.; Pervaiz, A.; Ghafoor, S. The triple threat: How green technology innovation, green energy production, and financial development impact environmental quality? Nat. Resour. Forum 2025, 49, 160–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabash, M.I.; Farooq, U.; Hassen, M.; El Refae, G.A. Do technological innovation and financial development determine environmental quality? Empirical evidence from Arab countries. Rev. Account. Financ. 2025, 24, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Quoc, D. Reassessing the Impact of Foreign Direct Investment on Environmental Quality in 112 Countries: A Bayesian Quantile Regression Approach. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 2025, 75, 641–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Abbas, A.; Hamid, A.; Keoy, K.H.; Cong, G.; Saleem, F.; Anwar, A. Green production practices for sustainable development: Impact of geopolitical risk, renewable energy, and foreign direct investment on environmental quality. Energy Environ. 2025, 0958305X251319369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seker, F.; Ertugrul, H.M.; Cetin, M. The impact of foreign direct investment on environmental quality: A bounds testing and causality analysis for Turkey. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 52, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, J.H.; Narula, R. The investment development path revisited. In Foreign Direct Investment and Governments; Routledge: London, UK, 1996; pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kyrkilis, D.; Pantelidis, P. Macroeconomic determinants of outward foreign direct investment. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2003, 30, 827–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Cui, C.; Lu, Z. Effect of cultural distance on reverse technology spillover from outward FDI: A bane or a boon? Appl. Econ. Lett. 2018, 25, 693–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Y. The effects of outward foreign direct investment on green technological innovation: A quasi-natural experiment based on Chinese enterprises. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2025, 110, 107666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Ren, Y.; Zhan, X. Outward foreign direct investment and pollution: Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 105, 104355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aybar, S. Determinants of Turkish outward foreign direct investment. Transnatl. Corp. Rev. 2016, 8, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CEIC. Turkey Foreign Direct Investment. 2025. Available online: https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/turkey/foreign-direct-investment (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- World Bank. World Bank Open Data. 2025. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Fiorini, M.; Hoekman, B. Services trade policy and sustainable development. World Dev. 2018, 112, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdouli, M.; Hammami, S. The impact of FDI inflows and environmental quality on economic growth: An empirical study for the MENA countries. J. Knowl. Econ. 2017, 8, 254–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, P.M.; Nguyen, T.D.; Nguyen, M.; Tran, N.T. FDI inflows and carbon emissions: New global evidence. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somoye, O.A. The impact of technological innovation on unemployment in Nigeria: An Autoregressive distributed lag and Frequency Domain Causality approach. SN Bus. Econ. 2024, 4, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitung, J.; Candelon, B. Testing for short- and long-run causality: A frequency-domain approach. J. Econom. 2006, 132, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, T.S. Revisiting the EKC hypothesis in an emerging market: An application of ARDL-based bounds and wavelet coherence approaches. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonanno, P.; Carraro, C.; Galeotti, M. Endogenous induced technical change and the costs of Kyoto. Resour. Energy Econ. 2003, 25, 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Guo, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wu, H.; Ren, S. Does outward foreign direct investment (OFDI) affect the home country’s environmental quality? The case of China. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2020, 52, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardi, W.; Hfaiedh, M.A. Causal Interaction between FDI, Corruption and Environmental Quality in the MENA Region. Economies 2021, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Firdousi, S.F.; Li, C.; Luo, Y. Inward foreign direct investment, outward foreign direct investment, and carbon dioxide emission intensity-threshold regression analysis based on interprovincial panel data. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 46147–46160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S.; Sethi, N. The energy consumption-environmental quality nexus in BRICS countries: The role of outward foreign direct investment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 19714–19730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Tian, J.; Wen, Q. Environmental regulation and outward foreign direct investment: Evidence from China. China Econ. Rev. 2022, 76, 101877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osabuohien-Irabor, O.; Drapkin, I.M. The spillover effects of outward FDI on environmental sustainability in developing countries: Exploring the channels of home country institutions and human capital. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 20597–20627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, W.; Luo, L.; Sun, H.; Zhong, Q. Does going abroad lead to going green? Firm outward foreign direct investment and domestic environmental performance. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2023, 32, 484–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quang, P.T. Vietnam’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment: Alignment with Environmental Policies and Pursuit of Carbon Neutrality Goals. J. Environ. Assmt. Pol. Mgmt. 2025, 27, 2550006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Naqvi, S.A.A.; Shah, S.A.R. The Contribution of Outward Foreign Direct Investment, Human Well-Being, and Technology toward a Sustainable Environment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçak, E.; Şarkgüneşi, A. The impact of foreign direct investment on CO2 emissions in Turkey: New evidence from cointegration and bootstrap causality analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 790–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adebayo, T.S. Transforming environmental quality: Examining the role of green production processes and trade globalization through a Kernel Regularized Quantile Regression approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 501, 145232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destek, M.A.; Ozsoy, F.N. Relationships between economic growth, energy consumption, globalization, urbanization and environmental degradation in Turkey. Int. J. Energy Stat. 2015, 3, 1550017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartal, M.T.; Gokceli, E.; Yildirim, H.H.; Calis, N. A new approach to analyze determinants of environmental quality: Evidence from E7 countries by panel approaches. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2025, 32, 428–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magazzino, C.; Gattone, T.; Madaleno, M. The impact of socio-economic factors on the ecological footprint in Turkey: A comprehensive analysis using machine learning approaches. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 387, 125861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, E. Türkiye’s Sustainability Challenge: An Empirical ARDL Analysis of the Impact of Energy Consumption, Economic Growth, and Agricultural Growth on Carbon Dioxide Emissions. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somoye, O.A. Assessing the link between energy intensity, renewable energy, economic growth, and carbon dioxide emissions: Evidence from Turkey. Environ. Qual. Mgmt 2024, 34, e22220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, T.S. Renewable Energy Consumption and Environmental Sustainability in Canada: Does Political Stability Make a Difference? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 61307–61322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauvage, J.; Timiliotis, C. Trade in services related to the environment. In OECD Trade and Environment Working Papers; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, R.; Shen, C.; Huang, L.; Tang, X. Does trade in services improve carbon efficiency?—Analysis based on international panel data. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 174, 121298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.Z.; Ghimire, S. Environmental Effects of Commodity Trade vs. Service Trade in Developing Countries. Commodities 2022, 1, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, G.; Krueger, A. Environmental Impacts of a North American Free Trade Agreement; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991; p. w3914. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland, B.R.; Taylor, M.S. Trade, Growth, and the Environment. J. Econ. Lit. 2004, 42, 7–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antweiler, W.; Copeland, B.R.; Taylor, M.S. Is free trade good for the environment? Am. Econ. Rev. 2001, 91, 877–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Chen, X.; Huang, B.; Yang, X. Economic and environmental impacts of foreign direct investment in China: A spatial spillover analysis. China Econ. Rev. 2017, 45, 289–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J.; Lai, K. Initiatives and outcomes of green supply chain management implementation by Chinese manufacturers. J. Environ. Manag. 2007, 85, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, J.M. Does trade liberalization harm the environment? A new test. Can. J. Econ. 2002, 35, 819–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarsky, L. Havens, halos and spaghetti: Untangling the evidence about foreign direct investment and the environment. Foreign Direct Invest. Environ. 1999, 13, 47–74. [Google Scholar]

- Rauf, A.; Ali, N.; Sadiq, M.N.; Abid, S.; Kayani, S.A.; Hussain, A. Foreign Direct Investment, Technological Innovations, Energy Use, Economic Growth, and Environmental Sustainability Nexus: New Perspectives in BRICS Economies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y.; Smith, R.J. Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. J. Appl. Econ. 2001, 16, 289–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibor–Alfred, C.; Somoye, O.A.; Ozdeser, H. Can government spending improve the quality of life in Nigeria? An ARDL and Spectral Granger Causality approach. SN Bus. Econ. 2025, 5, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rjoub, H.; Odugbesan, J.A.; Adebayo, T.S.; Wong, W.-K. Investigating the Causal Relationships among Carbon Emissions, Economic Growth, and Life Expectancy in Turkey: Evidence from Time and Frequency Domain Causality Techniques. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickey, D.A.; Fuller, W.A. Distribution of the Estimators for Autoregressive Time Series with a Unit Root. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1979, 74, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, P.C.B.; Perron, P. Testing for a unit root in time series regression. Biometrika 1988, 75, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Carbon Action Partnership. Türkiye Adopts Landmark Climate Law, Paving the Way for National ETS. 2025. Available online: https://icapcarbonaction.com/en/news/turkiye-adopts-landmark-climate-law-paving-way-national-ets (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Vitenu-Sackey, P.A.; Acheampong, T. Impact of economic policy uncertainty, energy intensity, technological innovation and R&D on CO2 emissions: Evidence from a panel of 18 developed economies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 87426–87445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, A.; Roh, T.; Su, M. Escaping regulation or embracing innovation? Substantive green Innovation’s role in moderating environmental policy and outward foreign direct investment. Energy 2025, 316, 134547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.