Abstract

Coastal port cities depend on global seafood flows, yet their food security is increasingly exposed to price volatility and supply disruptions. This study examines Busan citizens’ perceptions of seafood-related food security and seafood supply chain stability, and derives actionable municipal policy priorities for a trade-dependent port city. Anchored in the FAO four-dimensional framework—availability, access, utilization, and stability—we developed 20 seafood-related attributes and surveyed adult residents in Busan (n = 297). The measurement structure was assessed through reliability checks and exploratory factor analysis, and Importance–Performance Analysis (IPA) was used to map attribute-level priorities and identify the largest importance–performance gaps. Overall, respondents regard seafood food security as highly important but only moderately satisfactory. Availability and utilization perform relatively well, indicating perceived strengths in basic supply conditions and safe consumption, whereas access and stability show lower performance relative to importance, reflecting concerns about affordability, uneven physical access for vulnerable groups, price volatility, and exposure to external shocks. Notably, several stability-related attributes emerge as “Concentrate Here” priorities, highlighting the need for strengthened risk management, early warning communication, and resilience-oriented logistics planning at the city level. By integrating the FAO framework with attribute-level IPA, this study demonstrates how citizen perception data can translate macro food security debates into locally implementable priorities for building sustainable food systems in coastal cities.

1. Introduction

The global food system faces growing structural uncertainty as climate change, pandemics, geopolitical conflicts, and increasingly complex logistics interact, intensifying price volatility and supply instability. Against this backdrop, the policy agenda has shifted from short-term supply sufficiency toward the broader challenge of sustaining food systems that remain affordable, accessible, and resilient under repeated shocks. These developments have renewed interest in food security across a wider range of nutrient sources, including seafood [1]. Climate change negatively affects marine fishery resources and harvests, heightening risks for countries dependent on capture fisheries [2]. Food self-sufficiency should not be viewed as a binary choice between self-reliance and openness; rather, it represents a continuum in which countries calibrate domestic production and trade according to their specific conditions [3]. From this perspective, seafood food security is not merely a production issue but a system-level outcome shaped by the interaction of trade exposure, domestic distribution capacity, and local access conditions.

Seafood prices have exhibited structural upward pressure and heightened volatility due to rising production and logistics costs, shifts in demand for substitute goods, and increases in aquaculture feed prices [4]. Price dynamics are therefore increasingly interpreted as signals of supply chain fragility and risk transmission, especially in coastal cities where distribution and processing are concentrated. At the same time, despite growth in capture fisheries and aquaculture, the share of global marine fishery resources within biologically sustainable levels declined from 90% in 1974 to 62.3% in 2021 [5], illustrating deepening long-term vulnerabilities. Empirical studies show that fish production supports both economic growth and food security [6], positioning the fisheries sector as a strategic industry rather than merely a primary commodity producer [7]. Seafood thus lies at the intersection of two pressures—ecological and climatic constraints on supply and expanding demand driven by population growth, rising incomes, and heightened attention to nutrition—conditions that amplify the importance of stability and access in food security.

In Korea, where grain self-sufficiency is low and import dependence is high, seafood comprises a substantial share of national dietary intake, making seafood food security vital for both national and regional strategies. Busan—Korea’s largest center for seafood production, distribution, and processing—is directly exposed to fluctuations in global seafood trade, exchange rates, freight costs, and sanitary, environmental, and trade regulations. This exposure makes Busan an informative setting for examining how global shocks translate into perceived local vulnerabilities and policy needs. Yet domestic research has focused largely on grain-oriented food security, fisheries production, and seafood trade structures, with few studies systematically reconstructing seafood food security through the FAO’s four-dimensional framework—availability, access, utilization, and stability—or quantitatively analyzing urban citizens’ perceptions of supply chain stability. Moreover, the “stability” dimension—often discussed at the macro level—has rarely been operationalized into attribute-level priorities that local governments can act upon.

Because the ultimate beneficiaries of seafood food security policies are citizens, understanding which factors consumers deem important and where they perceive risk is fundamental for local governments and for strategic planning in seafood distribution, processing, and foodservice industries. Motivated by this perspective, the present study empirically examines Busan citizens’ perceptions of seafood food security and supply chain stability. Specifically, it measures importance and performance across seafood-related attributes using the FAO framework and applies IPA to identify priority areas for improvement. By linking seafood food security to supply chain stability within a sustainable food systems perspective, this study provides an evidence base for setting policy priorities—clarifying where current strengths (e.g., availability/utilization) coexist with persistent weaknesses (notably access and stability) that require targeted intervention. The Busan case offers implications for other coastal cities and fisheries hubs seeking to design regionally grounded strategies for resilient, sustainable food systems.

2. Theoretical Background and Literature Review

2.1. Conceptualizing Food Security

Food security is commonly defined as a condition in which “all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food” [8]. The concept has evolved from a narrow focus on caloric sufficiency to a broader framework that includes accessibility, nutrition, and sustainability. The FAO formalized food security into four dimensions—availability, access, utilization, and stability—providing a standard analytical lens for examining food systems at multiple scales [1,9]. Recent research using this framework highlights the need for policy, socioeconomic, and behavioral responses to intertwined supply, demand, and nutritional challenges [10,11].

According to the FAO, availability concerns the supply of adequate, high-quality food through domestic production and imports, determined by production, stocks, and net trade. Access refers to households’ and individuals’ capability to obtain food physically and economically, influenced by prices, incomes, and expenditure patterns. Utilization captures dietary quality, safe drinking water, sanitation, and health conditions that together shape nutritional outcomes. Stability evaluates whether availability and access can be maintained over time in the face of economic, climatic, or seasonal shocks [9]. Indices such as the Global Food Security Index (GFSI) are widely used to benchmark countries across these dimensions, including affordability, availability, quality and safety, and sustainability and adaptation [12].

Debates on food self-sufficiency underscore that an excessive emphasis on self-reliance can, paradoxically, weaken food security. Prior research summarizes several key risks, including heightened exposure to domestic production shocks in systems that rely little on trade, efficiency losses and long-run price increases under heavy market intervention, reduced incentives for export-oriented agriculture and constrained farm incomes (especially in developing countries), and ecological pressures where full self-sufficiency is unrealistic due to land, water, or climate constraints [3]. These arguments suggest that self-sufficiency and trade should not be treated as a binary choice but rather as elements in a context-specific policy mix calibrated to each country’s resources, trade structure, and vulnerabilities.

Although food security research has traditionally focused on grains, recent studies emphasize both the contribution and vulnerability of seafood within food systems [2,7,10,13,14]. Seafood is recognized as a nutrient-efficient and relatively less resource-intensive alternative to meat and as an important source of protein and omega-3 fatty acids [10]. In some countries and regions, fish and aquatic foods constitute a primary source of household nutrition [3,15,16], so reduced access can directly translate into nutritional imbalances and widened health disparities. At the same time, seafood is embedded in complex marine ecosystems and global value chains, spanning production, processing, logistics, trade, and retail [17]. Climate-driven shifts in fishing grounds, marine pollution, strengthened fisheries governance, high import dependence, and port or logistics bottlenecks pose multiple risks to seafood accessibility [6,14,18]. In highly import-dependent countries, external shocks such as international price volatility, exchange rate fluctuations, freight surges, and trade disputes make supply chain stability a central determinant of seafood food security.

Integrating general food security theory with the specific characteristics of seafood thus reveals seafood food security as a multidimensional policy domain that goes beyond a single commodity to encompass nutritional security, marine and fisheries policy, and trade and supply chain governance [6]. On this basis, the present study applies the FAO’s four-dimensional framework to the seafood sector and analyzes citizens’ perceptions of seafood food security and supply chain stability in an urban context.

2.2. Seafood Consumption and Food Security

Seafood is among the most widely traded food commodities worldwide: about 40% of global production enters international trade, with the trade value reaching USD 164 billion in 2018—roughly 4.5 times the 1990 level [19]. Seafood exports account for around 11% of global agricultural exports (excluding forestry products) and about 1% of total merchandise exports [20]. Within this context, research on seafood and food security can be broadly grouped into three strands: (1) nutrition and health, (2) fisheries, aquaculture, and resource management, and (3) distribution, consumption, and policy.

From a nutrition and health perspective, fish and seafood are highlighted as key contributors to public health through the provision of protein and essential fatty acids [16,17]. Empirical studies indicate that seafood consumption helps prevent chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, obesity, and metabolic syndrome, positioning stable access to seafood as a public health concern rather than merely a matter of preference [21,22]. In this view, seafood food security is a core component of nutritional security, and growth in fish production can improve dietary quality and health by expanding access to protein, minerals, and vitamins [23].

Research on fisheries, aquaculture, and resource management focuses on sustainable resource use and long-term supply capacity [13]. Overfishing and illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing, rising sea temperatures and shifting fishing grounds due to climate change, and environmental impacts from aquaculture are identified as key determinants of resource status and production [2,18,19,24]. These climate-driven changes can propagate beyond production to the market level by increasing variability in catch and aquaculture yields, disrupting harvesting schedules through extreme events, and heightening uncertainty in distribution and port operations. As a result, climate change can amplify supply instability and price volatility, reinforcing concerns about the medium- to long-term stability of seafood access. Prior studies stress that resource recovery, total allowable catch (TAC) systems, marine protected areas, and environmentally friendly aquaculture technologies are prerequisites for securing seafood food security under growing global demand [11]. The fisheries and aquaculture sectors also contribute indirectly to food security by providing employment and income in addition to supplying fish to markets.

From the standpoint of distribution, consumption, and policy, studies examine seafood markets through prices, distribution structures, and consumer perceptions of safety, freshness, and origin. Demand for eco-friendly and sustainable seafood is found to depend on consumer knowledge, perceptions, and purchasing behavior [25], with increased sustainability awareness, education, and willingness to pay premiums cited as major drivers [7,23]. Using an ordered probit model for Korean households, stronger price sensitivity is associated with a lower frequency of live fish consumption, whereas higher performance with safety is associated with a higher frequency, suggesting that perceptions of price and safety significantly shape purchasing behavior [26]. These findings imply that analyses of seafood food security must incorporate not only supply volumes and price levels but also risk perceptions, trust, and the information and distribution environment that frame consumer decisions.

Seafood price formation and volatility are influenced not only by traditional supply–demand factors such as production and transport costs but also by broader agricultural market conditions, including prices of substitutes like meat and feed, biofuel demand, and grain prices [4]. Fuel prices can further affect seafood affordability by raising transportation costs and, critically, the energy costs of cold-chain operations (refrigerated transport and storage). Because seafood is highly perishable, fuel- or energy-driven cost increases may translate into higher consumer prices and greater price volatility, especially when logistics disruptions constrain timely distribution. Seafood prices can also reflect the requirements of long-term storage and cold-chain management. Because seafood is highly perishable, extended storage often requires continuous refrigeration/freezing and strict temperature control, increasing energy and facility operating costs. Longer storage also raises inventory holding costs (handling, monitoring, insurance, and capital costs), while quality deterioration or shrinkage during storage can further translate into higher unit prices. Although long-term cold storage can buffer seasonal supply fluctuations, it may increase consumer price burdens unless cold-chain efficiency improves. With limited scope to increase capture production, aquaculture faces rising feed costs and supply constraints, amplifying price levels and volatility. In countries with high import shares, external shocks—exchange rate changes, international price swings, freight surges, and trade disputes—significantly affect domestic markets and consumer choices [3]. Under such conditions, trade measures targeting sustainable fishery products may expand markets for sustainably harvested or farmed seafood, offering policy tools to promote sustainable production and consumption [27]. Overall, these studies show that seafood food security is shaped by complex governance arrangements involving international trade, supply chains, and sustainability norms, rather than by supply volumes alone.

In Korea, per capita seafood consumption increased modestly from 58.5 kg in 2014 to 60.9 kg in 2023, an average annual growth rate of about 0.4%. Over the same period, seafood self-sufficiency rose from 72.8% to 77.0%, with recovery after a temporary decline between 2018 and 2020 [28]. These trends suggest that while consumption has been broadly maintained or slightly expanded and domestic production capacity has strengthened to some degree, structural constraints remain in mitigating supply chain risks associated with import dependence and fluctuations in global seafood markets.

2.3. Importance–Performance Analysis (IPA)

IPA evaluates the importance and performance associated with specific attributes of a good or service to identify priority areas for improvement [29]. By plotting mean importance and performance scores for each attribute on a two-dimensional grid and classifying them into four quadrants, IPA provides a simple and intuitive tool for allocating limited resources efficiently. Owing to this simplicity and visual clarity, it has been widely applied in service marketing, tourism, and public service evaluation, and has been adapted into related frameworks such as importance–performance, importance–urgency, and importance–feasibility analyses for strategic [30].

IPA, however, is not without limitations. It is susceptible to response bias—where unfamiliar attributes are rated as unimportant—and importance inflation, where respondents rate most items as highly important, leading to uniformly high importance scores and relatively lower performance scores [31,32].

In the standard IPA layout, performance is plotted on the horizontal (X) axis and importance on the vertical (Y) axis, and attributes are grouped into four quadrants with distinct strategic meanings [33]. Quadrant I (Concentrate Here) contains attributes with high importance but low performance, indicating areas that require focused improvement. Quadrant II (Keep up the Good Work) consists of attributes with high importance and high performance, representing strengths to be maintained. Quadrant III (Lower Priority) includes attributes with low importance and low performance, for which large investments are not warranted. Quadrant IV (Possible Overkill) encompasses attributes with low importance but high performance, where potential over-allocation of resources should be examined. Because IPA reflects respondents’ subjective evaluations, it is well suited for incorporating citizen and consumer perspectives into food security analysis.

In the context of food security, IPA can be used to identify perceived weaknesses and policy priorities in food systems. For seafood—where complex supply chains and multiple attributes such as safety and freshness, price and affordability, origin and traceability, and sustainability must be considered—IPA is particularly useful for detecting discrepancies between the perceived importance of individual factors and performance with their current performance.

The present study applies IPA to measure Busan citizens’ perceptions of seafood food security and, in particular, to analyze how attributes related to supply chain stability are evaluated in terms of importance and performance. Survey items were developed with reference to the FAO’s four food security components (availability, access, utilization, stability) and to seafood-specific attributes (safety and freshness, price and affordability, origin and traceability, sustainability, and supply chain and logistics stability). Respondents evaluated each attribute along two dimensions: “How important is this attribute for ensuring seafood food security for Busan citizens?” and “To what extent is this attribute currently being fulfilled in Busan?” Based on the mean importance– performance coordinates of each attribute on the IPA grid, the study:

- Identify which attributes related to seafood food security citizens perceive as most important and which they consider relatively less important.

- Determine which attributes—such as supply chain stability, price stability, and safety and reliability—fall within each quadrant and thereby distinguish priority areas requiring improvement from areas perceived as current strengths.

- Present policy implications that local governments and policymakers may use in designing seafood food security and supply chain policies based on these findings.

2.4. Distinctiveness of This Study

Compared with existing studies on seafood and food security, this study offers several distinctive contributions to the literature on sustainable food systems and policy prioritization.

First, this study empirically focuses on urban consumers in Busan, Korea’s largest hub for seafood production, distribution, and consumption. While prior research has often examined food security in low-income countries, rural or fishing communities, or at the national scale, urban, citizen-centered evidence in coastal and marine-oriented cities remains relatively limited. By surveying Busan residents, this study captures how seafood food security and supply chain risks are experienced in everyday urban contexts and provides a basis for extending similar analyses to other coastal cities.

Second, the study proposes an integrated analytical framework that links the FAO’s four food security dimensions—availability, access, utilization, and stability—to seafood value-chain attributes such as safety and freshness, price and affordability, traceability, sustainability, and supply chain stability. Rather than treating these components separately, the study conceptualizes seafood food security as a multidimensional outcome shaped by interactions among nutrition, resources, markets, and logistics. This integration is particularly relevant for sustainable food systems because it clarifies how weaknesses in access and stability can constrain sustainable consumption even when availability and utilization are relatively strong.

Third, methodologically, the study applies IPA to quantitatively structure citizen perceptions and translate them into actionable priorities. Although IPA is widely used in service quality and public-sector evaluation research, its application to food security—and especially to seafood food security at the urban level—has been relatively limited. Mapping perceived importance and performance onto an IPA grid enables the identification of (i) high-priority gaps requiring targeted intervention, (ii) areas where performance should be maintained, and (iii) domains needing gradual improvement, thereby strengthening the policy relevance of consumer-based assessments.

Finally, the findings yield practical implications for local policy design and resource allocation. By identifying attributes with the largest importance–performance gaps—particularly in the stability dimension—the study provides baseline evidence for regionally grounded strategies related to stockholding, distribution infrastructure, price stabilization, safety management, and sustainable consumption. More broadly, the results inform resilience-oriented interventions to mitigate external shocks, including global supply chain disruptions, climate change impacts, and volatility in international seafood trade.

In sum, by examining seafood food security in Busan through the lens of citizen perceptions and supply chain stability, this study addresses geographic and thematic gaps in existing research and offers a foundation for future urban-level and comparative research on sustainable food systems.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Framework

Building on the preceding theoretical discussion, this study empirically examines the structure of Busan citizens’ perceptions of seafood-related food security and their evaluations of seafood supply chain stability. To this end, it develops a conceptual research framework grounded in the FAO’s four dimensions of food security—availability, access, utilization, and stability—while incorporating seafood-specific attributes that are salient to urban consumers, including safety and freshness, price and affordability, country of origin and traceability, sustainability, and supply chain and logistics stability. These attributes represent key considerations for Busan citizens when assessing seafood-related food security. By measuring respondents’ perceived importance and their perceived current level of fulfillment (i.e., performance/satisfaction) for each attribute, the study captures seafood food security perceptions in a multidimensional manner.

The research framework is summarized as follows. First, the FAO food security dimensions and the seafood-specific attributes (safety and freshness, price and affordability, country of origin and traceability, sustainability, and supply chain and logistics stability) constitute sub-dimensions of citizens’ perceptions of “seafood food security.” Second, respondents’ importance and performance (satisfaction) scores for each attribute are plotted on an IPA grid to identify attributes requiring prioritized improvement as well as those that represent strengths to be maintained or further enhanced. Third, based on the IPA results, the study derives policy priorities and strategic directions for municipal-level seafood supply chain management and food security governance in Busan.

Grounded in this research framework, the study poses the following research questions:

RQ1. Which attributes related to seafood food security do Busan citizens perceive as relatively more important?

RQ2. What are the current performance (satisfaction) levels that Busan citizens assign to attributes related to seafood food security?

RQ3. Where do key attributes—such as supply chain stability, price and affordability, and safety and freshness—fall within the IPA quadrants, and which attributes emerge as policy tasks requiring prioritized improvement?

Rather than testing specific hypotheses, this study adopts an exploratory approach to answering these questions. It aims to structurally identify citizens’ perceptions of seafood-related food security in Busan, a major marine and fisheries hub city, and to use these insights to inform future policy design and subsequent research.

3.1.1. Definition of Attributes and Variables

The survey items used to measure perceptions of seafood-related food security and evaluations of seafood supply chain stability in this study were derived by synthesizing the FAO’s four components of food security—availability, access, utilization, and stability [9]—with the variable structures employed in previous studies on seafood, food security, and consumption behavior reviewed in Section 2. Attributes related to availability and access were informed by studies addressing seafood production, distribution, prices, and market access [18,19,25], while attributes related to utilization drew on research analyzing the effects of seafood intake on nutrition and health [16,21,23]. Attributes pertaining to stability were constructed on the basis of studies discussing how external shocks—such as climate change, international price volatility, and import dependence—affect seafood supply, prices, and ultimately food security [4,11]. Building on these theoretical and empirical discussions, the final set of items was refined to reflect the specific context of Busan as a marine and fisheries hub city.

Specifically, the availability (AV) domain captures perceptions of the stability of domestic seafood supply bases and distribution structures. In particular, respondents were asked whether they perceive domestic seafood distribution and logistics systems as functioning smoothly to ensure stable supply (AV02), how they view the impact of climatic and environmental factors—such as climate change, typhoons, and marine pollution—on seafood supply (AV03), and whether they believe that domestic capture fisheries and aquaculture production will be maintained at a certain level in the future (AV04). Item AV03 was originally formulated as a reverse-coded question asking the extent to which climate and environmental factors are perceived as threatening seafood supply. For the purposes of analysis, it was reverse-coded to align the directionality with other items so that higher scores indicate a stronger perception that the seafood supply base will remain relatively stable despite climatic and environmental changes.

The access (AC) domain comprises items measuring the extent to which seafood prices are perceived as a burden on household budgets (AC01, reverse-coded), the spatial and temporal accessibility of retail outlets where fresh and nutritious seafood can be purchased (AC02), the availability of diverse distribution channels in Busan—including traditional markets, large retail stores, and online platforms (AC03)—access to information on country of origin, production and distribution processes, and environmental and safety certifications (AC04), and the degree to which vulnerable groups such as low-income households, older persons, and persons with disabilities can access seafood economically and physically (AC05).

The utilization (UT) domain consists of five items that capture efforts to maintain a balanced diet including seafood (UT01), the extent to which freshness, safety, and hygiene are considered when consuming seafood (UT02), the level of knowledge and practice regarding seafood storage and cooking methods in the household (UT03), the frequency and diversity with which seafood is used at home (UT04), and the extent to which information on the nutritional value and health benefits of seafood is understood and reflected in dietary choices (UT05).

The stability (ST) domain encompasses items capturing citizens’ perceptions of medium- to long-term threats to seafood supply and food security, including climate- and marine-environment changes (ST01), destabilizing effects of international commodity prices, exchange rates, and oil prices on seafood prices (ST02), the perceived consistency and continuity of central and municipal (Busan) seafood-related policies (ST03), households’ perceived ability to secure food (including seafood) under economic and environmental changes (ST04), and risks arising from import dependence and potential international conflicts or supply chain disruptions (ST05). In this study, “stability” is defined as perceived stability of seafood supply and distribution (e.g., exposure to price volatility and disruption risks), rather than an objective market volatility index. The ST items were rated on a Likert scale for both perceived importance and perceived performance, and these item-level ratings were used as inputs to the IPA to identify policy priorities. (Where applicable, items were reverse-coded to ensure consistent directionality.)

3.1.2. Measurement of Importance and Performance

Importance and performance regarding attributes of seafood-related food security were measured using identical item content, with different instructions and in separate blocks. For the importance block, respondents were asked to rate each item (IMP_AV1–AV5, IMP_AC1–AC5, IMP_UT1–UT5, IMP_ST1–ST5) under the instruction: “How important do you think the following aspects are for ensuring seafood-related food security for Busan citizens?” For the performance block, respondents were presented with the instruction: “To what extent do you think the following aspects are currently being fulfilled in Busan?” and were then asked to evaluate the same items (PERF_AV1–AV5, PERF_AC1–AC5, PERF_UT1–UT5, PERF_ST1–ST5) in terms of the current situation.

Both importance and performance were measured on a five-point Likert scale. Importance was rated from “1 = Not at all important” to “5 = Very important,” and performance from “1 = Not at all the case” to “5 = Very much the case,” thereby quantifying respondents’ subjective evaluations for each attribute. By measuring importance and performance in parallel for the same set of attributes, the survey design enables visual identification, through IPA, of the gaps between the relative importance of each attribute and its perceived level of fulfillment.

3.2. Survey Target and Data Collection

The target population of this study consists of adult residents aged 19 years or older living in Busan Metropolitan City. As Korea’s representative marine and fisheries hub city—and as the nation’s center of seafood production, distribution, and consumption—Busan possesses regional characteristics that make it highly suitable for analyzing citizens’ perceptions of seafood food security. In light of these contextual factors, the study sought to empirically assess Busan citizens’ perceptions of seafood food security and their evaluations of seafood supply chain stability.

The sample was constructed using a non-probability (convenience) sampling method, with residents of Busan Metropolitan City serving as the sampling frame. The survey was administered via an online survey platform, and the administrative districts of Busan were referenced to avoid excessive concentration of respondents in specific districts. Residential areas were initially based on the official administrative divisions of Busan; however, for analytical purposes and in view of the sample size, some adjacent districts were combined. Specifically, Seo-gu and Dong-gu were coded as a single category, and Yeongdo-gu and Jung-gu were likewise combined into one category, while the remaining districts and counties were treated as separate units. In the questionnaire, respondents were asked to select the district in which they actually reside, and in the analysis stage, their responses were reclassified according to the above criteria.

To identify respondents’ general characteristics, basic sociodemographic variables such as gender, age, place of residence (district/county level within Busan Metropolitan City), educational attainment, and household income level were collected. These general characteristics are used to describe the composition and profile of the sample and, where necessary, serve as baseline information for exploring differences in perceptions across groups. However, because the primary unit of analysis in this study is the importance and performance scores for attributes related to seafood food security, the general characteristics are used in a limited manner as auxiliary variables to contextualize the IPA results.

The target sample size was set at a level sufficient to conduct IPA and basic descriptive statistical analyses. After excluding questionnaires with poor-quality responses or substantial item non-response, the final valid sample was determined. Detailed statistics on the final sample size and respondents’ general characteristics are presented in Section 4.

Data were collected using a structured self-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire was developed on the basis of the theoretical discussion in Section 2 and the variables and items presented in Section 3.1.1. Prior to the main survey, a small-scale pilot test was conducted to examine item comprehensibility and response time, and the questionnaire was subsequently revised and refined.

The main survey was conducted over a period of approximately two weeks, from 1 September to 12 September 2025. On the initial screen of the questionnaire, respondents were explicitly informed of the study’s purpose, the anonymity and confidentiality of their responses, the estimated time required to complete the survey, and the voluntary nature of participation; only those who agreed to these conditions were allowed to proceed. The online questionnaire was implemented using Google Forms, and the survey link was disseminated through local networks in Busan as well as university and institutional communities to facilitate participation by citizens across a wide range of age groups and occupations.

Completed questionnaires that did not meet the purposes of the study—such as those with identical responses across items, extremely short completion times, or missing answers on key questions—were excluded before determining the final valid sample. For this valid sample, descriptive statistics and IPA were conducted on the importance and performance scores for attributes related to seafood food security, while respondents’ general characteristics were used as basic information for interpreting the results.

3.3. Analytical Methods

3.3.1. Data Cleaning and Preliminary Analysis

Based on the survey data, this study analyzed the importance and performance associated with attributes of seafood-related food security. First, during the data-cleaning stage, responses deemed unreliable—such as those exhibiting excessively repetitive answer patterns, abnormally short completion times, or a large number of missing values on key items—were excluded from the dataset.

For the valid sample, missing values for each item were examined and, where necessary, handled using listwise deletion. Subsequently, basic descriptive statistics—such as means, standard deviations, and minimum and maximum values—were calculated for the importance and performance scores of attributes related to seafood food security (individual items within the AV, AC, UT, and ST domains) in order to assess the distribution of responses. Reverse-coded items (AV03, AC01, ST01, ST02, ST05 and their corresponding performance items) were recoded prior to analysis so that higher values consistently indicate more positive perceptions in the respective domains (higher AV, AC, and ST).

To assess the reliability and validity of the measurement instrument, Cronbach’s alpha (Cronbach’s α) was first calculated for each domain [34], thereby verifying whether the items related to seafood food security functioned as internally consistent scales. In addition, where appropriate, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted to examine the factor structure that emerges from the data and to determine how the attributes reflecting the FAO’s components of food security—AV, AC, UT, and ST—are grouped in practice [34]. However, because the primary unit of analysis in this study is the importance and performance of individual attributes rather than composite indices at the domain level, the results of the reliability and factor analyses were used mainly as reference information to confirm the adequacy of the measurement instrument underpinning the IPA. Accordingly, the subsequent empirical analysis does not rely on factor scores or composite indices by domain; instead, it directly utilizes the importance and performance responses for each of the 20 attribute items.

3.3.2. Procedure for Importance–Performance Analysis (IPA)

To address Research Questions 1–3 (RQ1–RQ3), Importance–Performance Analysis was employed as the core analytical method. IPA is a useful tool for determining where limited resources should be allocated first, as it simultaneously considers respondents’ perceived importance and performance for each attribute.

The analytical procedure was as follows. First, the mean importance and mean performance scores were calculated for each attribute. Second, the grand mean of importance (Mean Importance) and the grand mean of performance (Mean performance) across all attributes were computed and used to draw the cross hairs on the IPA coordinate plane—namely, the horizontal axis (X-axis: performance) and the vertical axis (Y-axis: importance). In other words, the four quadrants were delineated by setting the overall mean performance as the reference value on the X-axis and the overall mean importance as the reference value on the Y-axis. Third, each attribute was plotted on a two-dimensional plane using its mean importance and mean performance scores as coordinates (importance, performance), and the strategic implications of each attribute were interpreted according to the quadrant in which it was located. Drawing on previous studies [29,33], this study interprets the four IPA quadrants as follows.

- Quadrant I (High Importance/Low performance): This quadrant comprises attributes that respondents perceive as highly important but for which current performance is low; it is interpreted as a core vulnerable area where concentrated improvement efforts are required (Concentrate Here);

- Quadrant II (High Importance/High performance): This quadrant includes attributes with both high importance and high performance, which are regarded as key strengths where the current level of performance should be maintained and managed (Keep up the Good Work);

- Quadrant III (Low Importance/Low performance): This quadrant consists of attributes with low importance and low performance, interpreted as a relatively low-priority domain that does not warrant substantial allocation of limited resources (Low Priority);

- Quadrant IV (Low Importance/High performance): This quadrant contains attributes that are rated low in importance but high in performance, and is regarded as a domain where potential over-allocation of resources should be examined (Possible Overkill).

Fourth, by focusing on the quadrants in which individual attributes related to seafood food security—particularly key attributes such as supply chain and logistics stability, price stability, and safety and reliability—are located, the analysis identifies the vulnerability and strength factors of seafood food security as perceived by Busan citizens. On this basis, the study seeks to answer RQ1 (identifying the structure of perceived importance), RQ2 (assessing the level of performance), and RQ3 (deriving priority areas for improvement and policy tasks).

3.3.3. Interpretation and Derivation of Policy Implications

The IPA results are first presented by describing the overall structure of perceptions of seafood-related food security, focusing on the levels of importance and performance for each attribute and their placement within the four quadrants. Particular attention is then paid to how key attributes—such as supply chain stability, price and affordability, safety and freshness, and access—are combined in vulnerable versus strong areas, thereby identifying the relative priorities of seafood food security as perceived by Busan citizens.

Finally, the findings are reinterpreted from the perspective of local governments and relevant policymakers in order to propose policy priorities and directions for improvement in areas such as strengthening public seafood stockholding and distribution infrastructure, stabilizing prices and supply chains, enhancing safety and hygiene management, and improving information provision and awareness. In doing so, policy implications are derived with reference to the FAO’s components of food security and key arguments in the prior literature discussed in Section 2, while remaining within the interpretive scope of IPA.

4. Results

4.1. General Characteristics of Respondents

The valid sample for this study consists of 297 citizens residing in Busan, and their general characteristics are summarized in Table 1. In terms of gender, 55.2% (n = 164) were male and 44.8% (n = 133) were female. With respect to age, respondents in their 30s (30–39 years) accounted for the largest share at 51.2% (n = 152), followed by those in their 40s (40–49 years) at 23.9% (n = 71), those aged 18–29 years at 13.8% (n = 41), those aged 50–59 years at 7.4% (n = 22), and those aged 60 years or older at 3.7% (n = 11), indicating a relatively high proportion of respondents in their 30s and 40s.

Table 1.

General characteristics of respondents (n = 297).

Regarding educational attainment, 1.0% (n = 3) had completed middle school or less, 14.8% (n = 44) had completed high school, 61.3% (n = 182) were university graduates (including junior colleges), and 22.9% (n = 68) had completed graduate school or higher, meaning that approximately 84% of respondents had at least a university degree. In terms of monthly household income, the 4–6 million KRW bracket was the most common at 31.3% (n = 93), followed by 2–4 million KRW at 24.9% (n = 74), 8 million KRW or more at 21.2% (n = 63), 6–8 million KRW at 19.9% (n = 59), and 2 million KRW or less at 2.7% (n = 8).

With respect to seafood consumption frequency (per week), “1–2 times” accounted for an absolute majority at 70.0% (n = 208), followed by “rarely consume” at 18.9% (n = 56), “3–4 times” at 9.4% (n = 28), and “5 times or more” at 1.7% (n = 5). As for experience purchasing sustainable seafood, 67.0% (n = 199) responded “yes” and 33.0% (n = 98) responded “no,” indicating that approximately two-thirds of respondents had experience purchasing sustainable seafood. Information on occupation and detailed place of residence (district/county within Busan) was also collected; however, these variables are not reported in the table, given that they are not used in subsequent analyses, and only key sociodemographic characteristics and seafood-related behavioral variables are presented.

As shown in Table 1, respondents aged 30–39 account for a relatively large share of the sample. This concentration likely reflects the characteristics of the online, non-probability (convenience) sampling approach and dissemination channels used in the survey. Accordingly, the results should be interpreted with caution regarding demographic representativeness, and the findings may more strongly reflect the perceptions of the 30s age cohort than those of other age groups.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Reliability of Seafood Food Security Attributes

4.2.1. Subsubsection

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the importance and performance scores evaluated by respondents for individual attributes within the availability, access, utilization, and stability domains of seafood-related food security. Each item was measured on a five-point Likert scale (1 = “Not at all the case”/“Not at all important,” 5 = “Very much the case”/“Very important”). The results show that the overall mean importance score across the 20 attributes was 3.50, while the overall mean performance score was 3.20. This indicates that Busan citizens generally perceive the proposed seafood-related attributes as “rather important,” but evaluate the actual level of fulfillment as somewhat lower than their perceived importance.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for importance and performance of seafood food security attributes.

In the AV domain, mean importance scores ranged from 3.11 to 3.95, and mean performance scores from 2.96 to 3.77. Among these, the item capturing the impact of climatic and environmental factors—such as climate change, typhoons, and marine pollution—on seafood supply (AV_03) recorded relatively high scores, with an importance mean of 3.95 and a performance mean of 3.77. This suggests that Busan citizens regard the stability of the domestic seafood supply base under changing climatic and environmental conditions as an important factor and, at the same time, evaluate the current situation relatively positively. Although AV_03 was originally presented in the questionnaire as a reverse-coded item asking about concerns that climate change, typhoons, and marine pollution would destabilize seafood supply, it was recoded during the analysis so that higher scores indicate a perception that the supply base remains more stable despite climatic and environmental changes. By contrast, items related to concentration in specific products or countries of origin and to the government’s stockpiling and adjustment functions (AV_04, AV_05) received relatively lower evaluations, with mean importance and performance scores in the low 3-point range and below 3.0, respectively, compared to other attributes.

In the AC domain, mean importance scores ranged from 2.88 to 3.69 and mean performance scores from 2.70 to 3.45, indicating overall lower levels compared with the availability and utilization domains. Items related to price burden and access to distribution channels (AC_01, AC_02) showed importance and performance means in the low to mid-3 range, whereas items concerning information accessibility (information on origin, distribution, environmental and safety aspects) and access for vulnerable groups (AC_04, AC_05) recorded the lowest values, with importance means of 2.88–2.99 and performance means of 2.70–2.83. This suggests that, while there is a certain level of concern about seafood prices and purchasing environments, issues such as information gaps and accessibility for vulnerable groups are either not perceived as particularly important or are not sufficiently recognized by citizens.

In the UT domain, mean importance scores ranged from 3.24 to 4.15, and mean performance scores from 3.12 to 3.96. In particular, the item asking the extent to which respondents consider freshness, safety, and hygiene when consuming seafood (UT_02) showed the highest scores among all attributes, with an importance mean of 4.15 and a performance mean of 3.96. This indicates that the qualitative aspect of “how” seafood is consumed is perceived by Busan citizens as a highly central factor. By contrast, items related to understanding and using nutritional information on seafood (UT_05) and to household storage and cooking practices (UT_03, UT_04) exhibited importance and performance means in the low to mid-3 range, suggesting that while there is a basic level of interest and practice, these aspects do not command as high a priority as freshness and safety.

In the ST domain, mean importance scores ranged from 3.07 to 4.21, the highest among the four domains. The item on the medium- to long-term impacts of climate change and marine environmental change on seafood supply (ST_01) and the item on price instability arising from international price and exchange rate fluctuations (ST_02) recorded very high importance means of 4.21 and 4.01, respectively, indicating substantial concern and interest among respondents regarding the long-term stability of seafood-related food security. However, performance scores for these same items were only 2.93–2.96, resulting in larger gaps between importance and performance than in other domains. Likewise, items related to import dependence and supply chain risks (ST_03–ST_05) showed mid-3 importance scores but performance scores around 3.0. These patterns suggest that there are domains within perceptions of seafood supply chain and price stability that are viewed as “important but insufficiently addressed,” and they indicate a high likelihood that such attributes will emerge as policy-relevant vulnerable areas in the subsequent IPA.

In sum, among the various attributes related to seafood food security, Busan citizens perceive stability—namely climate and environmental change, international price and exchange rate fluctuations, and supply chain risks—and freshness and safety in the consumption process (UT_02) as core factors, and these attributes exhibit relatively large gaps between importance and performance. By contrast, more structural access issues, such as information accessibility and access for vulnerable groups, are evaluated with relatively low importance and low performance. These descriptive results provide the basis for interpreting where each attribute is located on the IPA grid and, further, for identifying which areas constitute vulnerable factors that should be prioritized in policy terms.

4.2.2. Reliability Analysis of the Measurement Instrument

To assess the internal consistency of the measurement instrument for attributes related to seafood food security, Cronbach’s α coefficients were calculated for each domain as well as for all items combined. The results show that Cronbach’s α for the 20 importance items was 0.89, and Cronbach’s α for the 20 performance items was 0.91, indicating that the measurement instrument used in this study has an overall acceptable level of reliability (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of reliability analysis for seafood food security items.

By domain, Cronbach’s α for the importance items in the availability (IMP_AV), access (IMP_AC), and utilization (IMP_UT) domains was 0.75, 0.77, and 0.82, respectively, while the corresponding performance items (PERF_AV, PERF_AC, PERF_UT) also ranged from 0.70 to 0.82. These values generally meet the commonly accepted threshold for reliability (0.70 or higher) [34]. In the stability domain, the performance items (PERF_ST) exhibited very high reliability, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.91, whereas the importance items (IMP_ST) showed a relatively lower coefficient of 0.57.

Although this study adopts the FAO’s four components of food security—AV, AC, UT, and ST—as its theoretical analytical framework, the core unit of empirical analysis is the importance and performance of individual attributes as applied in the IPA, rather than composite indices at the domain level. In particular, given the relatively low internal consistency observed for the stability importance items, the analysis for this domain focuses on the position and relative priority of each item on the IPA grid rather than on a single domain score. Accordingly, stability-related implications are derived primarily from the item-level IPA positions and importance–performance gaps rather than from a single composite domain score. Taken together, despite some limitations in certain subdomains, the survey items employed in this study can be regarded as having an overall adequate level of reliability for analyzing Busan citizens’ perceptions of seafood food security and deriving policy implications through IPA.

Consistent with the reliability results reported in Table 3 (Cronbach’s α), we interpret stability primarily at the item level in the IPA (importance–performance positions and gaps), rather than relying on a single aggregated stability score. The relatively low Cronbach’s alpha for the stability importance scale (IMP_ST) likely reflects the multidimensional nature of “stability” as perceived by citizens. The ST items span heterogeneous facets—policy continuity, international price volatility, import- and conflict-related supply risks, and logistics disruptions—which may not co-vary strongly as a single latent construct. This interpretation is consistent with the EFA results, where stability-related items load on different factor clusters (e.g., ST01 versus ST02/ST03/ST05). Given that IPA is conducted and interpreted at the item level, stability-related implications in this study are derived primarily from the quadrant positions and importance–performance gaps of individual ST items rather than from a composite domain score.

4.3. Exploratory Factor Analysis

4.3.1. Assessment of Factorability

Before conducting an EFA on the 20 importance items related to seafood food security (five items each for availability, access, utilization, and stability), the suitability of the data for factor analysis was examined. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was 0.88, exceeding the conventional threshold of 0.80 and thus indicating a “meritorious” level of suitability. The Bartlett’s test of sphericity also yielded a significant result, χ2(190) = 2904.19, p < 0.001, confirming that the correlation matrix differs significantly from an identity matrix. These results suggest that the correlation structure among the variables is sufficiently appropriate for applying factor analysis, as summarized in Table 4 [34].

Table 4.

Factorability of importance items.

4.3.2. Factor Extraction and Rotation Results

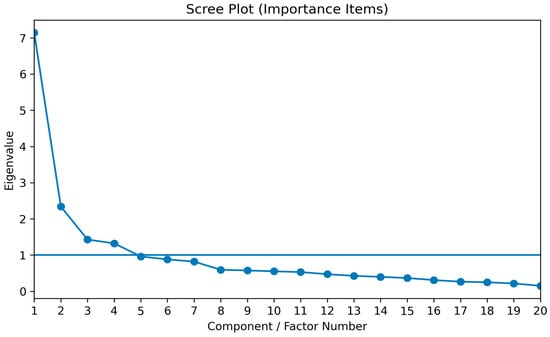

Factor extraction was conducted using principal component analysis based on the correlation matrix, and the number of factors was determined by jointly considering the eigenvalue-greater-than-one criterion and the scree plot. As shown in Figure 1, the scree plot indicates an elbow after the fourth component, supporting the retention of a four-factor solution. This visual evidence complements the eigenvalue-greater-than-one criterion reported below.

Figure 1.

Scree plot of eigenvalues for the importance items (correlation-matrix PCA). The blue line with circles shows the eigenvalues for each component, and the horizontal blue line indicates the Kaiser criterion threshold (eigenvalue = 1).

The eigenvalues of the first four factors were 7.14, 2.34, 1.43, and 1.32, respectively, and these four factors together accounted for approximately 61.2% of the total variance. Accordingly, a four-factor solution was retained as the final model, and Varimax orthogonal rotation was applied to facilitate interpretation.

Table 5 reports the factor extraction results and the explained variance for the importance items. Based on the rotated factor loadings, the primary factor associated with each item was identified and the factors were interpreted as follows. First, Factor 1 showed high loadings for items related to structural and institutional vulnerabilities in seafood supply and distribution, as well as social accessibility—such as excessive dependence on specific countries or products, access to distribution channels and information, access for vulnerable groups, and government supply and policy responses (e.g., ST03, ST04). This factor can therefore be interpreted as “structural and institutional vulnerabilities and social accessibility.” Second, Factor 2 exhibited high loadings for items capturing perceptions of climate change and marine environmental change (ST01), international price and exchange rate fluctuations (ST02), supply chain risks (ST05), and related perceptions (e.g., AV03, AC01), and can thus be understood as an “environmental, price, and supply chain risk perception” factor in relation to seafood food security. Third, Factor 3 was characterized by high loadings on items concerning household-level seafood utilization and dietary habits, including maintaining a balanced diet that incorporates seafood (UT01), household storage and cooking practices, consumption habits, and the use of nutrition and health information (UT03–UT05). Fourth, Factor 4 grouped together items related to seafood supply quantity and quality (AV01), distribution and logistics systems (AV02), access to outlets selling fresh seafood (AC02), and freshness and safety in the consumption process (UT02), and can be interpreted as a “basic supply conditions and physical/quality access” factor.

Table 5.

Factor extraction and explained variance for importance items.

Overall, the exploratory factor analysis indicates that the FAO’s four components of food security—AV, AC, UT, and ST—are reflected in the empirical data as interrelated subdimensions (Table 6). However, rather than mapping neatly in a one-to-one manner onto the theoretical domains of AV, AC, and ST, each factor appears to capture meaningful clusters that naturally arise in citizens’ perceptions, such as supply and distribution structures and institutional vulnerabilities, environmental and price risk perceptions, household utilization and dietary habits, and basic supply and access conditions. In light of this, the factor-analytic results are used primarily as supplementary evidence to support the construct validity of the measurement instrument [34]. In the subsequent IPA, each of the 20 items continues to serve as an individual unit of analysis, and the focus remains on the importance and performance levels and quadrant placement of those items in order to identify vulnerable areas of seafood food security and policy priorities. In other words, the exploratory factor analysis is treated as an auxiliary procedure to examine the theoretical structure of the scale, and no additional statistical models (such as regression analyses) based on factor scores are specified in this study.

Table 6.

Factor structure of seafood food security perceptions (summary).

4.4. IPA Results

Building on the FAO’s four dimensions of food security—AV, AC, UT, and ST—this study measured Busan citizens’ perceived importance and performance for 20 seafood-related attributes using a five-point Likert scale and conducted an IPA. The overall mean importance across all items was approximately 3.50, while the overall mean performance was about 3.20, indicating that respondents view seafood food security in Busan as generally important but perceive performance to be only moderate.

By dimension, the ST domain recorded the highest mean importance score (≈3.72) but the lowest mean performance score (≈2.97). In contrast, the UT domain received relatively favorable evaluations (importance ≈ 3.60; performance ≈ 3.45). The AV and AC domains showed mean importance and performance scores of ≈3.50 and ≈3.38, and ≈3.17 and ≈3.01, respectively, suggesting comparatively stronger evaluations for the basic supply and use environment but greater concerns about long-term stability and access.

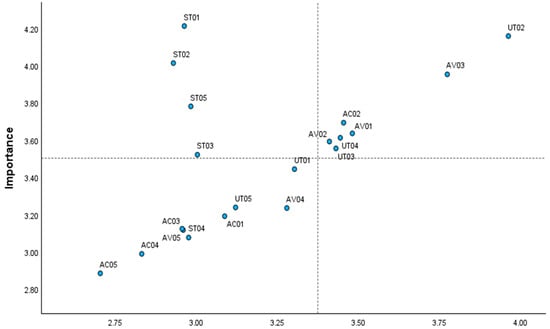

The IPA grid axes were set using the overall means for the 20 attributes (importance = 3.50; performance = 3.20). Figure 2 shows that four stability items (ST01, ST02, ST03, ST05) fall into the “Concentrate Here” quadrant (high importance/low performance). By contrast, several AV and UT items and some AC items (e.g., AV01–AV03, UT02–UT04, AC02) are located in “Keep up the Good Work” (high importance/high performance). The remaining access items, along with some AV and ST items, fall into “Low Priority” (low importance/low performance), while a few items such as AV04 and UT01 are classified as “Possible Overkill” (low importance/high performance). Among stability items, ST04 is distinct in that both its importance and performance are below the overall means, placing it in “Low Priority,” suggesting it is perceived as less urgent than ST01, ST02, ST03, and ST05 or not yet recognized as a salient issue.

Figure 2.

IPA map of seafood-related food security attributes in Busan (n = 297). The x-axis denotes mean perceived performance and the y-axis denotes mean perceived importance (5-point Likert scale). The dotted quadrant lines (crosshairs) indicate the grand means across all attributes (importance = 3.50; performance = 3.20), thereby defining the four IPA quadrants: Keep Up the Good Work, Concentrate Here, Low Priority, and Possible Overkill. Points are coded by domain (AV, AC, UT, ST); notably, four stability items (ST01, ST02, ST03, ST05) appear in Concentrate Here, indicating high concern but comparatively low performance.

Overall, the IPA map indicates a clear domain-level contrast: AV and UT tend to be evaluated relatively favorably, whereas several AC and ST attributes show larger importance–performance gaps. This pattern implies that citizens perceive basic supply conditions and safe consumption environments as comparatively well delivered, but remain concerned about affordability and uneven access for vulnerable groups, as well as instability driven by external shocks and price fluctuations. Accordingly, interpretation focuses on the quadrant positions and gaps of individual attributes, which directly inform the prioritization and sequencing of municipal interventions.

Table 7 presents the eight attributes with the largest importance– performance gaps from the IPA results. The gap value was calculated by subtracting the performance score from the importance score; thus, a larger positive value indicates that citizens regard the attribute as important but perceive actual policy or market performance as insufficient. The top four attributes in terms of gap all belong to the ST dimension—ST01, ST02, ST05, and ST03—with gap values of 1.25, 1.08, 0.79, and 0.52, respectively. Accordingly, this study identifies these four stability-related attributes as core “Concentrate Here” areas in the IPA and proposes ST01 as the first-priority improvement task, followed by ST02, ST05, and ST03 in descending order of priority. This indicates that, when considering seafood-related food security, Busan citizens perceive “supply chain stability”—including mitigation of price and supply volatility, resilience to external shocks, and medium- to long-term management of supply chain risks—as the foremost priority.

Table 7.

Key seafood food security factors in the “Concentrate Here” quadrant.

By contrast, the remaining four items among the top eight attributes—AC02, UT02, and AV02 and AV03—recorded gap values of 0.24, 0.19, and 0.18 (for both AV items), suggesting that these are areas with room for improvement but that they fall within the “Keep up the Good Work” quadrant, where both importance and s performance exceed the overall means. This implies that, although these attributes already exhibit a certain level of policy and market performance, citizens’ expectations are even higher, leading to residual dissatisfaction and a demand for further enhancement. Consequently, while these attributes are of lower priority in the short term compared with the stability (ST) dimension’s core improvement tasks, it remains necessary in the medium to long term to maintain and manage their current levels and gradually narrow the gaps through fine-tuning measures such as strengthening information provision, improving service quality, and expanding support for vulnerable groups.

In sum, the IPA findings based on Busan citizens’ perceptions indicate that policy priorities for enhancing seafood-related food security are clearly concentrated on “securing the long-term stability of the supply chain.” While the relative strengths observed in the dimensions of AV and UT should be maintained, it is necessary to design a policy portfolio that gradually addresses structural vulnerabilities in access and stability. This study presents the overall distribution of the 20 attributes through the IPA matrix in Figure 1 and extracts only the attributes with the largest importance–performance gaps in Table 7, thereby visualizing more clearly the core issues of seafood food security as experienced by Busan citizens and specifying concrete policy priorities. Finally, the IPA employed in this study follows the traditional approach of delineating quadrants using the mean values of importance and performance. Although this method is intuitive and highly practical for policy and managerial applications, it has the methodological limitation that the placement and priority of attributes can be sensitive to how the quadrant cut-off values are defined [35]. Accordingly, the IPA results presented here should be interpreted not as absolute prescriptions for seafood food security policy, but rather as perception-based reference indicators that ought to be given priority consideration in policy design.

4.5. Key Findings

This chapter analyzed Busan citizens’ perceptions of seafood-related food security using survey items derived from the FAO’s four dimensions—AV, AC, UT, and ST—and applying descriptive statistics, reliability and factor analyses, and IPA.

Overall, respondents viewed seafood-related food security as important but evaluated current conditions less favorably. AV and UT recorded relatively higher levels of both importance and performance, indicating comparatively positive assessments of basic supply conditions and consumption environments. In contrast, AC and especially ST showed lower performance relative to importance, suggesting concerns about affordability, physical access, and medium- to long-term stability. Reliability and factor analyses further indicated that the empirical dimensions largely correspond to the theoretical structure.

The IPA results highlight ST as the dimension with the most pronounced need for improvement. Four ST attributes (ST01, ST02, ST03, ST05) fell into the “Concentrate Here” quadrant, exhibiting the largest importance–performance gaps. Prioritization based on gap size identified ST01 as the largest gap item, followed by ST02, ST05, and ST03, indicating that respondents’ primary concerns are not limited to immediate supply volume but extend to price volatility, external shocks, and medium- to long-term supply chain risks.

Several attributes in the AV and UT dimensions, along with selected access items, were positioned in the “Keep up the Good Work” quadrant, indicating relatively strong perceived performance in these areas.

At the same time, items such as AC02, UT02, AV02, and AV03 displayed moderate gaps, implying room for incremental improvements, including enhanced access conditions, improved information and transparency, and continued quality management in distribution and retail environments.

Taken together, the results suggest a dual pattern: Busan exhibits a generally positive baseline in seafood-related food security, while comparatively larger perceived vulnerabilities remain in the stability dimension. This empirical pattern provides a basis for interpreting the policy implications and strategic directions discussed in the next chapter.

5. Discussion, Implications, and Limitations

5.1. Discussion

This study sought to identify policy priorities linking seafood supply chain stability and seafood-related food security in Busan, thereby informing pathways toward sustainable food systems at the municipal level. To this end, the four dimensions of food security proposed by the FAO—AV, AC, UT, and ST—were adopted as the theoretical framework, and each dimension was operationalized into specific survey items reflecting seafood-specific attributes. A structured questionnaire survey was conducted accordingly. The validity of the measurement instrument was examined through descriptive statistics, reliability analysis, and factor analysis, and IPA was then applied to compare perceived strengths and weaknesses across individual attributes as evaluated by Busan citizens.

First, respondents generally viewed seafood-related food security as highly important, yet current performance was assessed as falling short of expectations. AV and UT scored above the overall average in both importance and performance, indicating relative strengths in supply conditions and consumption environments. By contrast, AC and ST showed lower performance relative to importance, revealing structural vulnerabilities related to affordability, physical access, and the system’s capacity to respond to external shocks.

Second, the IPA results indicated that all four items in the ST dimension (ST01, ST02, ST03, ST05) were located in the “Concentrate Here” quadrant and exhibited the largest importance–performance gaps. Priority ranking based on gap size identified ST01 as the most urgent area, followed by ST02, ST05, and ST03. These findings suggest that, for Busan citizens, the core challenge lies in managing price and supply volatility and strengthening medium- to long-term seafood supply chain stability rather than increasing supply volume per se.

Third, several attributes outside the stability dimension—AC02, UT02, AV02, and AV03—also presented comparatively large gaps. Although these items predominantly fall within the “Keep up the Good Work” quadrant, the magnitude of their gaps indicates areas where further refinement may be required to better meet citizens’ expectations.

Overall, the findings indicate that while Busan demonstrates relative strengths in AV and UT, clearer policy prioritization is warranted to reinforce seafood supply chain stability and address selected access-related gaps, supporting a more resilient seafood food security system consistent with sustainable food systems objectives.

5.2. Policy Implications

Drawing on the above findings, this study derives policy implications and priorities to strengthen the linkage between seafood supply chain stability and seafood-related food security in Busan, thereby supporting sustainable food systems at the municipal level. As cautioned in [3], an exclusive focus on self-sufficiency may heighten exposure to domestic production shocks, reduce market efficiency, and generate environmental burdens. Accordingly, Busan’s seafood food security strategy should adopt a balanced approach that combines domestic supply measures with stable and responsible engagement with international markets.

First, reinforcing medium- to long-term seafood supply chain stability should be the top policy priority. The concentration of ST attributes in the “Concentrate Here” quadrant indicates strong public concern about price volatility, disruptions in import and distribution channels, and vulnerability to external shocks. In response, Busan—working with the central government and relevant neighboring jurisdictions—should diversify procurement sources, strengthen stockpiling and emergency supply arrangements, and institutionalize risk management tools such as monitoring and early warning mechanisms for key species and major supply routes. To reduce transportation costs while preserving freshness, Busan should enhance cold-chain efficiency and logistics productivity through routing and consolidation (e.g., shared distribution and hub-based operations) and improved digital visibility (e.g., real-time temperature monitoring and traceability) to minimize quality losses and shrinkage. Climate change is also a structural driver of instability: warming seas, shifting fishing grounds, and more frequent extreme events can disrupt production and distribution, increasing supply variability and price volatility. Accordingly, early-warning systems and contingency logistics planning should incorporate climate-related risk signals alongside market and trade shocks. Given the energy intensity of cold-chain logistics, fuel-price shocks should be explicitly incorporated into early-warning signals and contingency logistics planning, as they can rapidly raise transportation and refrigeration costs and amplify price volatility.

Second, policy efforts should prioritize reducing access disparities across income groups and neighborhoods. Although access is perceived as important, sizable gaps for certain items suggest perceived differences in affordability and AV. Improving both economic and physical access—through targeted support for low-income households, strengthened distribution infrastructure in underserved areas, and upgraded digital and logistics networks—can help mitigate these disparities, particularly for vulnerable groups.

Third, the relative strengths identified in AV and UT should be maintained and leveraged to reinforce system-wide resilience. While these areas received generally positive evaluations, attributes with notable gaps point to the need for further improvements in safety-information transparency, traceability, consumer education, and tailored dietary programs. In addition, shelf-life extension can be pursued not only through cold-chain logistics but also via preservation treatments and packaging technologies, including the regulated use of additives/preservatives. Because such measures can affect perceived sensory quality and safety, transparent labeling, inspection, and traceability are essential to maintain consumer trust while reducing losses and improving distribution efficiency. Integrating these efforts with urban public health initiatives—for example, through school and welfare meal programs—may enhance nutritional outcomes while sustaining trust in seafood markets.

Fourth, seafood food security should be advanced through an integrated urban strategy for sustainable food systems. The findings indicate that supply chain stability, access, and utilization are interconnected with fisheries and aquaculture production, seafood processing and distribution, and urban dietary patterns. Consistent with prior work emphasizing integrated approaches to food security, Busan could develop a “seafood-based urban food security strategy” that aligns fisheries and seafood industry development, marine environmental and resource management, and citizen health and welfare policy [36]. Such a strategy can treat self-sufficiency and trade openness as complementary instruments while pursuing multi-layered measures that strengthen regional competitiveness and sustain reliable access to global seafood networks.

Overall, the findings support a Busan-specific implementation pathway. In the short term, municipal actions should prioritize visible stabilization measures addressing citizens’ top concerns in the stability dimension (e.g., routine monitoring and early-warning communication, contingency logistics planning, and targeted buffers against price and access shocks for vulnerable households). In the medium term, Busan can institutionalize these measures through a city-level seafood risk management framework aligned with national procurement and emergency supply arrangements, while strengthening traceability and safety-information transparency and maintaining consumer trust in freshness and safety. This roadmap translates IPA-based priorities into actionable steps for enhancing seafood supply chain stability and seafood-related food security within Busan’s municipal sustainable food system agenda.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

While this study provides theoretical and policy relevance by examining Busan citizens’ perceptions of seafood-related food security and seafood supply chain stability using IPA, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, external validity is constrained by the non-probability (convenience) sampling approach and the sample’s demographic composition (including the relatively high share of respondents in their 30s). Accordingly, the findings should be interpreted with caution in terms of representativeness and generalizability beyond Busan and across age cohorts. Future research may broaden geographic coverage and employ more rigorous sampling designs, including stratified or quota-based recruitment and/or post-stratification weighting.

Second, the study’s methodological scope is limited by the use of IPA, which offers an intuitive comparison of perceived importance and performance but does not identify causal relationships among attributes. Moreover, the exclusive reliance on perceptual measures restricts direct engagement with behavioral indicators (e.g., consumption frequency, expenditure, or purchasing decisions), and mean-based quadrant cut-offs may entail conceptual ambiguity [35]. Future studies could triangulate IPA with complementary approaches (e.g., regression-based models, segmentation analyses, structural modeling, and alternative cut-off specifications) to assess behavioral linkages and heterogeneity across groups [26,35].

Third, the measurement framework necessarily covered a bounded set of items and could not fully incorporate broader seafood-related concerns (e.g., sustainability, IUU fishing, climate change impacts, trade dynamics, and emerging ESG-related trends). In addition, this study did not directly capture shelf-life extension measures (e.g., additives/preservatives or packaging technologies) or consumers’ awareness of related labeling, which may influence perceived safety and trust. Finally, because the study focused on citizens as respondents, it could not fully capture the perspectives of other stakeholders across the seafood value chain. Mixed-method designs and multi-stakeholder surveys may therefore enhance the practical relevance of future governance and management recommendations.

6. Conclusions