Abstract

As vital components of urban rail transit networks, subway stations are widely scattered across diverse urban districts, whose sustainability performance exerts a notable impact on the overall urban ecological and environmental quality. This study constructs a three-dimensional numerical model to conduct a comparative assessment of the seismic behavior of subway stations adopting different bearing systems at beam-column joints. The seismic responses of two typical structural configurations, a traditional rigid-jointed subway station and another equipped with rubber isolation bearings, are examined under a series of ground motions, with due consideration of amplitude scaling effects and material nonlinearity. A comprehensive evaluation is carried out on key performance parameters, including structural acceleration responses, column rotation angles, damage evolution processes, and internal force distributions. Based on this analysis, the research clarifies the sustainability implications by establishing quantitative correlations between seismic response indices (i.e., deformation extent, damage degree, and internal force magnitudes) and post-earthquake outcomes, such as repair complexity, material requirements, carbon emissions, and socioeconomic effects. The results can advance the integrated theory of seismic-resilient and sustainable design for underground infrastructure, providing evidence-based guidance for the optimization of future subway station construction projects.

1. Introduction

Amidst accelerating global urbanization, urban rail transit has emerged as the backbone of metropolitan transportation networks, owing to its efficiency, high capacity, and low carbon footprint [1,2,3]. Subway stations, serving as critical nodes within these systems, perform essential functions in passenger aggregation and transfer, constituting indispensable components of urban lifeline infrastructure. With continued urban expansion and increasing density of underground development, the proliferation of subway stations has drawn significant engineering and societal attention to their structural safety and long-term operational sustainability [4]. Earthquakes rank among the most devastating natural hazards, and historical seismic events have demonstrated that underground structures, including subway stations, are vulnerable to damage [5,6]. For instance, during the 1995 Kobe Earthquake in Japan, multiple subway stations experienced severe structural cracking, collapse, and water ingress, leading to service suspension for months and substantial socioeconomic losses [7,8]. Similarly, in the 2008 Wenchuan Earthquake in China, various underground transit facilities sustained considerable damage, further underscoring the imperative to enhance the seismic performance of subway stations [9].

Concurrently, with the growing emphasis on sustainable development, the construction sector, a major consumer of energy and source of emissions, faces increasingly stringent requirements for energy conservation and emission reduction [10]. As large-scale, long-lifecycle infrastructure, subway stations embody sustainability considerations throughout their entire life cycle, from design and construction to operation, maintenance, demolition, and material recovery [11,12]. Evaluating their sustainability typically encompasses multiple dimensions, including environmental aspects (e.g., energy consumption, carbon emissions), economic aspects (e.g., construction, operation, and maintenance costs), and social aspects (e.g., service quality, disaster resilience) [13,14,15]. Consequently, in the design and construction of subway stations, merely ensuring structural safety is insufficient. It is essential to achieve an organic integration of seismic performance and sustainability, thereby advancing the dual objectives of disaster resilience and low-carbon environmental stewardship.

Beam–column connections represent critical structural elements in subway stations, responsible for transmitting internal forces (e.g., axial force, bending moment, and shear force) and accommodating deformations under various loads such as seismic action, train vibration, and soil pressure [16]. The type of bearings adopted at these connections directly influences force transfer paths, stiffness distribution, and the seismic response of the entire subway station structure [17,18,19]. Commonly used bearings include fixed, sliding, and rubber types [20], with each exhibiting distinct mechanical behaviors in terms of load-bearing capacity, deformability, and energy dissipation capacity under dynamic and static loading scenarios. These differences significantly affect not only seismic performance, such as lateral displacement, inter-story drift, and damage progression under seismic loading [16,18,19], but also sustainability indicators, including material consumption, construction complexity, operational energy use, maintenance costs, and end-of-life recyclability [4,14,21]. Therefore, investigating the influence of different beam–column connection bearing types on both seismic performance and sustainability, and conducting targeted sustainability assessments within seismic performance constraints, holds considerable practical significance for optimizing station design schemes and enhancing the overall structural safety, durability, and environmental friendliness of subway stations.

In recent years, extensive research has been conducted on the seismic performance and sustainability of subway stations [16,17,18,19,20,22,23]. However, notable gaps remain in integrating these two critical domains. Studies focusing on seismic performance have largely concentrated on the structural response under varying seismic intensities, the optimization of structural configurations, and the mechanical behavior of innovative materials, laying a solid foundation for ensuring seismic safety [24,25,26], but seldom addressing the potential implications for sustainability indicators. Conversely, sustainability assessments in construction engineering have primarily centered on developing evaluation frameworks and applying them to conventional buildings, bridges, and other infrastructure, often neglecting the unique seismic performance requirements of underground subway stations. As a result, existing sustainability evaluations of subway stations frequently overlook seismic constraints, leading to potential misalignment between design optimization and actual seismic safety demands, being a discrepancy the current research aims to resolve. On the other hand, regarding beam–column connection bearings, existing studies have focused mainly on their mechanical properties and influence on the seismic behavior of aboveground structures [20,27,28,29], with limited attention paid to their application in subway stations and associated impacts on station sustainability. Moreover, the prevailing sustainability evaluation methods for subway stations rely on static assessment approaches, failing to capture dynamic variations in sustainability performance under seismic damage scenarios. Hence, there is a pressing need to conduct a seismic-performance-informed sustainability evaluation on subway stations and systematically examine how different bearing types affect sustainability, filling the aforementioned research gaps.

Looking at these challenges, a three-dimensional refined numerical model for the seismic analysis of subway stations with varied bearing configurations at beam–column joints is established in this paper. The seismic performance of two subway station configurations, one with conventional rigid beam–column connections and another incorporating rubber isolation bearings, is thoroughly investigated, considering the influences of ground motion characteristics, amplitudes, and material nonlinearity. Key response indicators, including structural acceleration, column rotation, structural damage, and internal forces at different locations, are systematically analyzed. Subsequently, by correlating three critical metrics (i.e., the degree of structural deformation, the extent of damage, and the level of internal forces) with post-earthquake repair difficulty, potential material consumption, associated changes in carbon emissions, economic losses, and environmental and social impacts, the way seismic performance variations induced by different beam–column connection types affect sustainability is examined. The findings in this study can contribute to enriching the theoretical framework for the seismic and sustainable design of underground structures, providing theoretical support and technical guidance for the optimized design and construction of future subway stations.

2. Numerical Model for Seismic Performance Analysis

2.1. Brief Introduction to a Subway Station with Varied Bearings

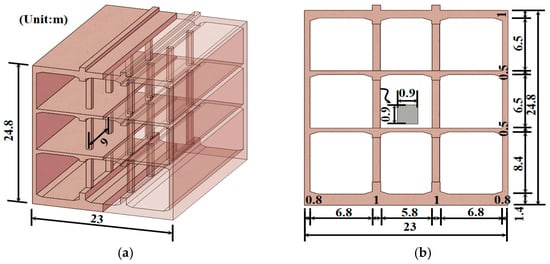

This study is conducted based on a three-story subway station with two different bearings at beam–column joints embedded in a layered soil site. Figure 1 illustrates the structures of the subway station with traditional rigid bearings and corresponding dimensions.

Figure 1.

Configuration of an underground subway station. (a) 3D view of the whole station. (b) 2D view of the cross-section.

The station has a height of 24.8 m and a width of 23 m, with its roof situated at a cover depth of 13 m. In the overall structural layout, the transverse spans from left to right measure 6.8 m, 5.8 m, and 6.8 m, respectively. The sidewalls of the station are 0.8 m thick, and the beams between adjacent spans have a width of 1 m. The floor slabs from the bottom to the top level are 1.4 m, 0.5 m, 0.5 m, and 1 m thick. Columns with a rectangular cross-section (side length 0.85 m) are used to support the beams at different floor levels, spaced at 9 m intervals along the longitudinal direction.

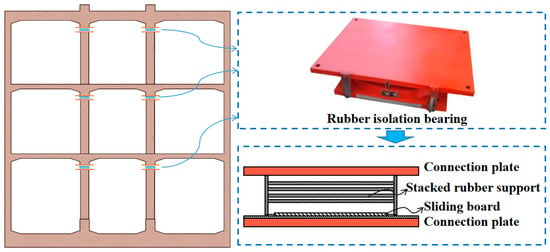

Additionally, rubber isolation bearings and the overall structural configuration of the subway station utilizing these beam–column connections are illustrated in Figure 2. The laminated rubber isolation bearing is primarily composed of an upper connecting plate, a lower connecting plate, laminated rubber layers, and a sliding plate. Among these, the laminated rubber layers control the overall stiffness of the bearing, while the sliding interface between the sliding plate and the lower connecting component constitutes the critical part of the bearing. The sliding plate is typically manufactured from stainless steel. Under vertical loading, the bearing exhibits a certain shear resistance. When the horizontal load induced by an earthquake exceeds this shear resistance, sliding initiates at the sliding interface.

Figure 2.

Subway station with rubber isolation bearings.

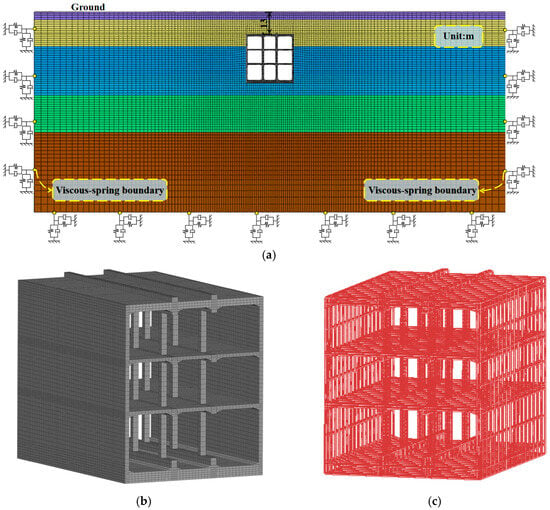

2.2. Three-Dimensional Numerical Model for Seismic Performance Analysis

For the comparative analysis of the seismic response of the subway station with varied bearings at beam–column joints, a finite element numerical model incorporating both the layered soil site and the subway station structure was established using ABAQUS. Figure 3 provides a schematic illustration of the overall numerical model dimensions and mesh discretization. As shown in Figure 3a, the overall width of the model was set to 230 m, following the criterion of being no less than ten times the width of the station. Previous studies have demonstrated that such a dimension in width can effectively mitigate adverse effects caused by truncated boundaries on structural dynamic analysis [18,19]. In addition, the overall model has a height of 90 m and a longitudinal length of 40 m.

Figure 3.

Numerical model for seismic performance analysis. (a) Whole model consisting of the layered soil site. (b) Structures of the three-story subway station. (c) Reinforcement of the subway station.

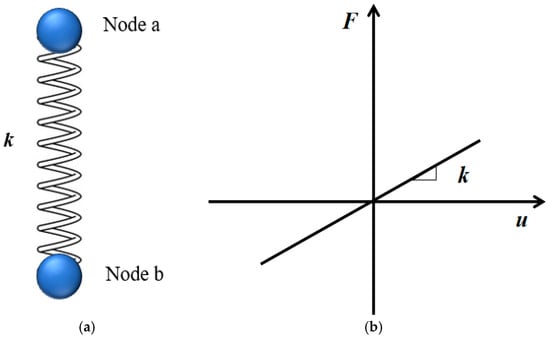

On the other hand, for the subway station using rubber isolation bearings, the total model is almost identical to that shown in Figure 3, except for some special settings that are necessary to include the rubber isolation bearings. In this study, the actual volume of the rubber isolation bearings is ignored, and the bearings are replaced by spring connections in the numerical model. The mechanical effect of the rubber isolation bearing is simulated utilizing a linear restoring force model, illustrated in Figure 4. Then, the effect of rubber isolation bearings can be achieved based on spring stiffness in horizontal and vertical directions, respectively, which can be obtained through the following equations [19]:

in which H is the size of the total rubber layer in terms of thickness, and kh and kv denote the horizontal and vertical spring stiffness, respectively. G denotes the shear modulus of rubber, while E is the elastic modulus of rubber. As is the rubber bearing effective area. In this study, kh and kv are 2450 kN/m and 2830 kN/mm, respectively.

Figure 4.

Simulation of the rubber isolation bearings. (a) Simplified model. (b) Linear restoring force model.

For the mesh of different parts in the model, the soil, along with numerous structural components of the subway station such as the floor slabs, walls, and columns, are modeled using C3D8 elements. Specifically, the soil mesh size is set based on the shear wave velocity as well as the cutoff frequency, as shown in Equation (2).

in which Se denotes the mesh size, vs denotes the shear wave velocity of the soil, and fmax represents the cutoff frequency of the seismic wave.

Furthermore, the reinforcement within the structure is simulated with truss elements and connected to the station structure via an embedded region constraint, which can accurately represent the interaction between concrete and reinforcement, as observed in actual engineering practice. Furthermore, the interface between the outer surface of the structure and the surrounding ground is treated with a tie constraint, meaning that separation or slip at the contact interface is not permitted.

2.3. Material Properties

To adequately account for the influence of material nonlinearity on the seismic response analysis of the subway station, all material types involved in the analysis are simulated using nonlinear constitutive models. Among them, the nonlinear dynamic response of the soil is characterized by the Davidenkov model. The corresponding dynamic viscoelastic constitutive relationship, with regard to the Davidenkov backbone curve, can be expressed by Equation (3). The detailed parameters for describing soil materials using the Davidenkov model can be found in Table 1.

where G denotes the soil shear modulus and is the maximum value. denotes the corresponding soil shear strain. A, B, and denote the controlling parameters regarding the soil materials.

Table 1.

Material properties of different soil layers [19].

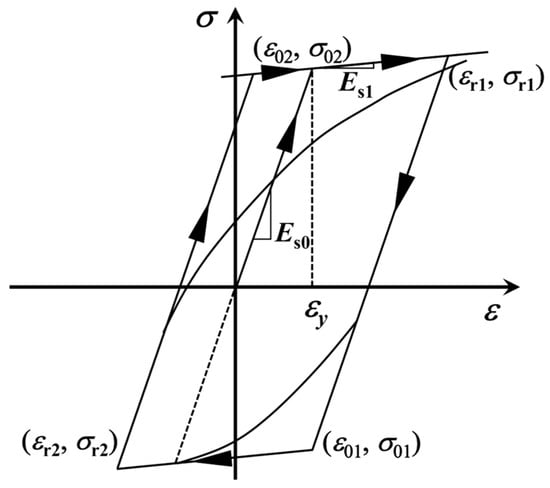

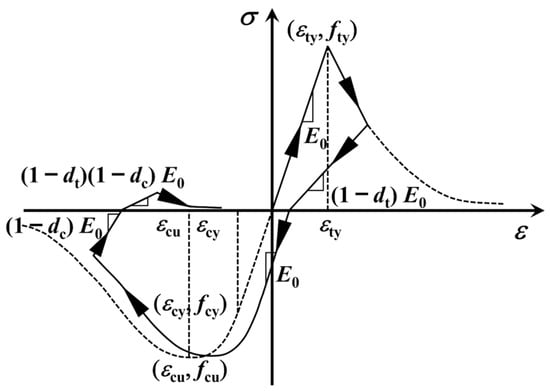

In addition, various concrete components of the subway station, namely beams, floor slabs, walls, and inter-story columns, are made of C30 concrete. The main reinforcement of the station structure uses HRB335 steel bars, while stirrups are made of HPB235 steel bars. Two distinct nonlinear constitutive models are adopted for concrete and steel to simulate the elastoplastic behavior of the subway station structure under seismic loading. Specifically, a hardening model capable of simulating the elastoplastic response under cyclic loading is employed for steel, whereas a damage plasticity model is used for concrete. Schematic diagrams of the corresponding material constitutive models are shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6, and the detailed material parameters are listed in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively.

Figure 5.

Hardening model for steel.

Figure 6.

Damaged plasticity model for concrete.

Table 2.

Material properties of steel [5].

Table 3.

Material properties of concrete [5].

2.4. Boundary Condition

The viscous-spring boundary presented by Deeks and Randolph [30] and Liu et al. [31] is used in the three-dimensional numerical model for seismic response analysis of subway stations to deal with the truncated boundary, so that the accuracy and reliability of the calculation results can be ensured due to its advantages of good accuracy, stability, and easy implementation. Modeling the viscous-spring artificial boundary within a finite element framework requires assigning a discrete set of spring and damper elements, connected in parallel, to the nodes at the model’s boundaries. These elements are oriented along the two tangential axes and the single normal axis. Their respective stiffness and damping coefficients are prescribed by the formulations given in Equation (4).

where and , in which is the medium Poisson’s ratio, while ρ denotes the medium density. and are correction coefficients to calibrate spring stiffness in different directions; R is the distance from the scattering source to the fussed boundary node. In this study, is set to be 1.33 and is set to be 0.67; Ab means the influence area of a node at several model boundaries.

2.5. Seismic Input Method and Waves

The equivalent nodal force method [31,32] was selected as the way to input the seismic waves into the numerical model in this study. Using this method, the seismic wave input can actually be transformed into several groups of nodal forces applied along the truncated boundary. This approach adeptly captures the radiation damping phenomenon and enables a more accurate simulation of seismic wave propagation from an effectively unbounded domain into the finite numerical model. Consequently, for the seismic input to be accurate, the equivalent nodal forces applied at this artificial boundary must reproduce the precise displacement and stress fields that would exist in the original, undisturbed free-field [31]. That is, the input condition satisfies the consistency requirement between the finite model and the semi-infinite space, as shown in Equation (5).

Following the concept of a free-body diagram in classical mechanics, the boundary node is treated as a discrete element separate from the attached spring–dashpot element. The governing force equilibrium equation for this interaction can be written as:

Then, from the motion equation of the spring–dashpot, the governing force equilibrium equation can be converted into the following form:

By substituting Equation (7) into Equation (6), the equivalent nodal force can be gained by:

Finally, the equivalent nodal force regarding seismic input waves can be calculated by substituting Equation (5) into Equation (8):

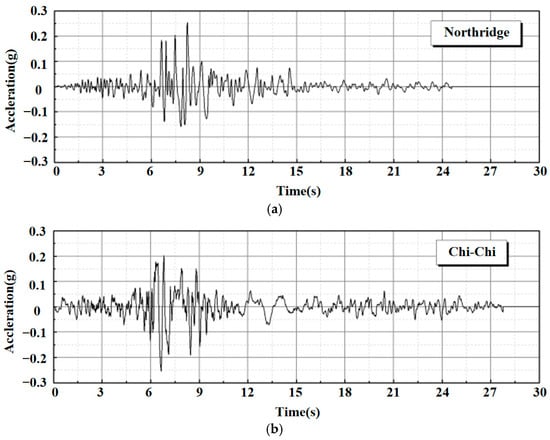

In this study, two different seismic waves with acceleration amplitudes of 0.05 g, 0.15 g, and 0.25 g are selected as the input ground motions. Specifically, the Northridge wave (Mw6.7, PGA 0.753 g, LA Sepulveda VA Hospital Seismic Observatory, 1994 Northridge earthquake) and Chi-Chi wave (Mv7.6, PGA 0.364 g, TCU122 Seismic Observatory, 1999 Chi-Chi earthquake) are used for the seismic analysis of subway stations, whose acceleration time history curves are shown in Figure 7. It is worth noting that the Chi-Chi ground motion was selected because significant underground structural damage was observed during that earthquake, while the Northridge ground motion was chosen because it is widely adopted in seismic response analyses of similar underground structures. In addition, the three input ground motion acceleration amplitudes of 0.05 g, 0.15 g, and 0.25 g used in the analysis correspond to three different seismic intensity levels, namely, frequent earthquakes, design-basis earthquakes, and rare earthquakes, enabling a relatively comprehensive evaluation of the structural damage characteristics and their implications for the sustainability of subway stations under varying seismic intensities.

Figure 7.

Numerical analysis steps. (a) Northridge wave. (b) Chi-Chi wave.

2.6. Numerical Analysis Conducting Steps

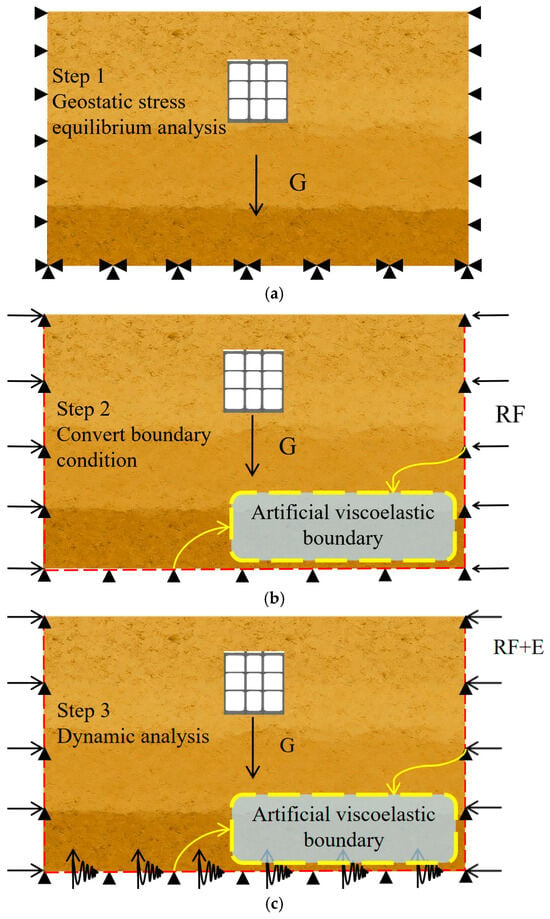

During the numerical analysis, the detailed calculating steps are arranged as shown in Figure 8, and the corresponding work can be concluded as follows.

Figure 8.

Numerical analysis steps. (a) Geostatic analysis. (b) Convert boundary condition. (c) Seismic analysis.

Step 1: The analysis commenced with establishing the initial geostatic analysis. Transverse and longitudinal displacements were restrained at the lateral model boundaries, while all degrees of freedom were fixed at the bottom boundary. The gravity load was subsequently applied. Upon reaching equilibrium, the reaction forces at the lateral boundaries were extracted for subsequent seismic input.

Step 2: Following the initial analysis, the lateral and bottom boundaries were transformed into viscous-spring artificial boundaries. Spring-damper elements were assigned to boundary nodes in the normal and tangential directions. The reaction forces obtained from the geostatic analysis were then applied as static equivalents to the corresponding lateral boundary nodes.

Step 3: The seismic excitation was applied in the final step via concentrated time–dependent forces at each node of the artificial boundaries. Based on the target input seismic displacement and velocity time histories, the corresponding equivalent nodal forces were calculated and applied at each time step to propagate the waves into the model.

2.7. Verification of Numerical Model

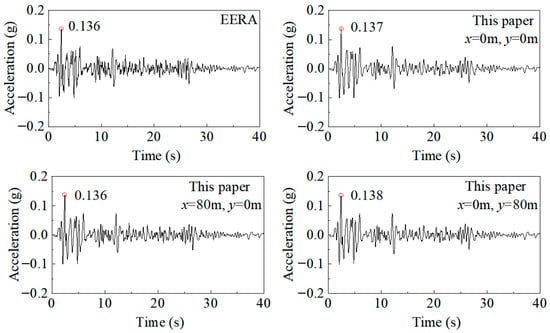

A three-dimensional finite element model is developed to conduct nonlinear seismic response analysis of the free-field site using the numerical method in this paper. The free-field domain is composed of eight horizontal soil layers overlying elastic bedrock, with a total thickness of 80 m. The material parameters for each soil layer and the equivalent linear properties corresponding to each soil type are provided in detail in [33]. The computational domain of the finite element model is defined with a half-width (x-direction) of 100 m, a half-length (y-direction) of 100 m, and a depth (z-direction) of 80 m. It is assumed that the El Centro ground motion, scaled to a peak acceleration of 0.1 g, is vertically incident on the bedrock along the x-direction. Under such conditions, the surface responses of the three-dimensional free-field model should theoretically be identical. Figure 9 presents the surface acceleration time histories recorded at three observation points: x = 0 m, y = 0 m (located at the center of the surface), x = 80 m, y = 0 m (along the x-axis), and x = 0 m, y = 80 m (along the y-axis). As illustrated in Figure 9, the acceleration time-history responses at these three locations obtained from the proposed finite element model are nearly identical. Furthermore, these results show good agreement with those generated by the Earthquake Engineering Risk Assessment (EERA) method, which confirms the reliability and accuracy of the numerical model.

Figure 9.

Comparison of seismic responses of the three-dimensional free field between EERA and this paper.

3. Discussion on Seismic Performance of Subway Stations

3.1. Acceleration at Different Locations of Subway Stations

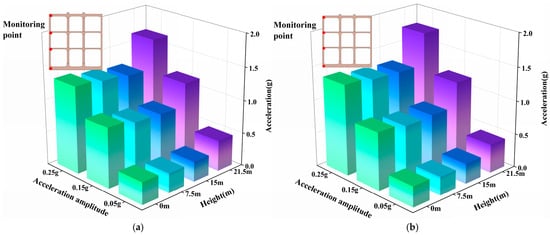

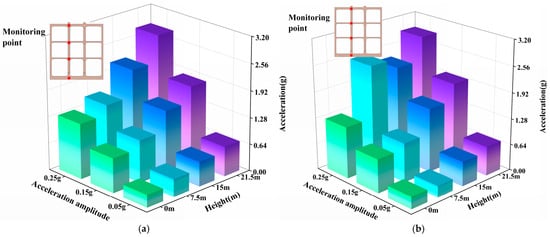

To investigate the influence of column-beam connections on the acceleration response of a multi-story, multi-span subway station under seismic excitation, the sidewalls and center columns were selected as two distinct structural components for analysis. A comparison was made of the peak ground acceleration (PGA) variations along their respective heights when subjected to two seismic waves with different input amplitudes. The variation in peak accelerations along the height of the sidewalls is presented in Figure 10 and Figure 11, while the corresponding variation for the center columns is shown in Figure 12 and Figure 13.

Figure 10.

Comparison between peak accelerations at different locations of side wall in subway stations with different beam–column joints under the Northridge wave. (a) Traditional rigid connections. (b) Rubber isolation bearings.

Figure 11.

Comparison between peak accelerations at different locations of side wall in subway stations with different beam–column joints under the Chi-Chi wave. (a) Traditional rigid connections. (b) Rubber isolation bearings.

Figure 12.

Comparison between peak accelerations at different locations of the central column in subway stations with different beam–column joints under the Northridge wave. (a) Traditional rigid connections. (b) Rubber isolation bearings.

Figure 13.

Comparison between peak accelerations at different locations of the central column in subway stations with different beam–column joints under the Chi-Chi wave. (a) Traditional rigid connections. (b) Rubber isolation bearings.

As shown in Figure 10, under the action of the Northridge wave, when traditional rigid column–beam connections are employed, the peak acceleration of the center column exhibits an increasing trend with height, with the maximum peak acceleration essentially occurring at the roof slab level. Furthermore, as the amplitude of the input wave increases, the peak acceleration of the center column also increases, while the overall distribution pattern of acceleration along the height remains largely unchanged. Therefore, for subway stations using rigid connections, variations in the amplitude of the input ground motion have a relatively minor influence on the overall distribution characteristics of the center column’s acceleration. In general, the acceleration of the center column under the Northridge wave action roughly follows an inverted triangular distribution along the height, which is consistent with the acceleration response pattern observed in the free field. Similar trends have also been reported in other studies on the seismic performance of subway stations. This consistency indicates that the surrounding strata significantly influence the dynamic response characteristics of subway stations under seismic action.

It is noteworthy that when the amplitude of the input wave acceleration reaches a certain level (0.25 g), the peak acceleration at the base slab becomes larger than that at the first-level roof slab. Consequently, the peak acceleration of the center column along the entire height exhibits a trend of first decreasing and then increasing. As seen in Figure 10a,b, even under excitation with a PGA of 0.05 g, a relatively clear nonlinear relationship between peak acceleration and height can be observed. The acceleration along the column height initially decreases within a given story before gradually increasing thereafter. The aforementioned variation is directly related to the frequency content of the input ground motion, which can be confirmed by comparing Figure 10a,b with Figure 12a,b. Simultaneously, the presence of the station structure alters the distribution characteristics of the horizontal stiffness in the horizontally layered site. The corresponding influence generally intensifies with increasing ground motion amplitude, which, to some extent, also modifies the acceleration distribution within the underground structure.

Furthermore, it is evident that under the same PGA condition, the acceleration response of the center column under the Chi-Chi wave is greater than that under the Northridge wave. This is because the predominant frequency of the Chi-Chi wave is the lowest among the two selected ground motions. Due to the site’s amplification effect at low frequencies and its filtering effect at high frequencies, the Chi-Chi wave possesses the greatest seismic energy, thereby inducing the most significant dynamic response in the station structure.

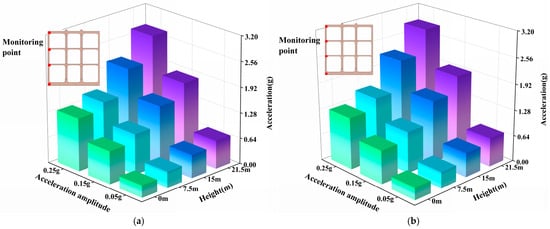

3.2. Column Rotation at Different Stories of Subway Stations

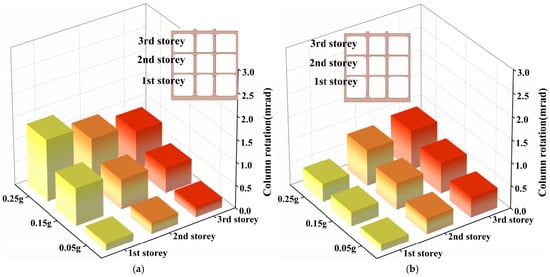

Figure 14 and Figure 15 illustrate the variations in rotation angles of the center columns at different floor levels for subway station models employing traditional rigid beam–column joints and rubber laminated bearings, respectively, under two seismic waves with varying input amplitudes. As depicted in the figures, there is a significant discrepancy in the rotation angles of columns across all levels between the two models with different connection types.

Figure 14.

Comparison between peak column rotation at different stories of subway stations with different beam–column joints under the Northridge wave. (a) Traditional rigid connections. (b) Rubber isolation bearings.

Figure 15.

Comparison between peak column rotation at different stories of subway stations with different beam–column joints under the Chi-Chi wave. (a) Traditional rigid connections. (b) Rubber isolation bearings.

Overall, for the station model with traditional rigid connections, the rotation angle is largest at the first story columns and smallest at the top story columns. This distribution pattern aligns with that of the inter–story drift angles. Given the high deformation compatibility between the slabs and sidewalls during lateral deformation, coupled with the relatively lower lateral stiffness of the columns, the column rotations in rigidly connected stations are primarily forced rotations induced by the horizontal deformations of the sidewalls and slabs. Consequently, their distribution characteristics largely mirror those of the inter-story drift angles.

In contrast, the column rotations in the station structure equipped with isolation bearings exhibit a completely opposite trend: the smallest rotations occur at the first story, while the largest occur at the top story. This disparity leads to a rapid decrease in the ratio of column rotations between the two models as the story level increases, while the ratio increases with the amplitude of the input ground motion acceleration. Furthermore, when the ground motion amplitude does not exceed 0.15 g, the rotation of the top-story columns in the station with traditional rigid connections is smaller than that in the model with isolation bearings. However, under almost all other conditions, the column rotations in the rigid-connection model are greater at every level, and this difference becomes more pronounced with larger input ground motion amplitudes. Generally, a larger rotation angle implies a higher risk of damage to the center columns. Therefore, the comparative analysis in this section demonstrates that the use of isolation bearings can effectively reduce the degree of column damage. This helps ensure that the vertical load-bearing capacity of the columns at each level does not suffer excessive loss, thereby effectively preventing a global progressive collapse disaster triggered by the loss of vertical bearing capacity in the center columns of subway station stories during an earthquake.

3.3. Structural Damage Characteristics of Subway Stations

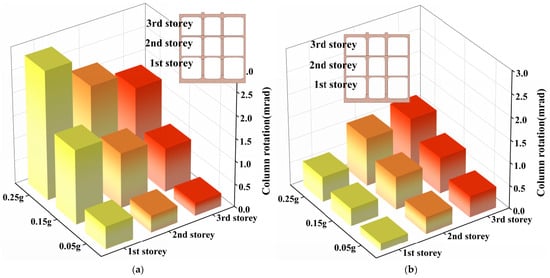

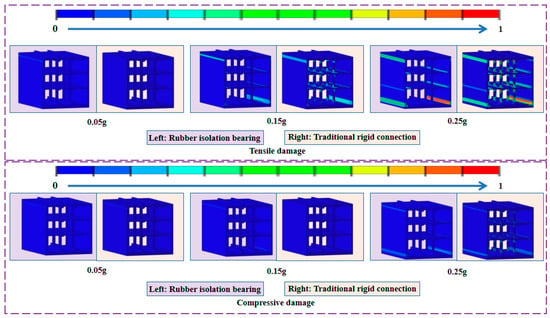

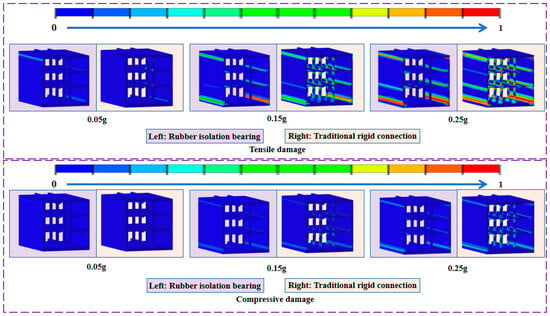

Structural damage characteristics serve as another key indicator reflecting the influence of column–beam connection types on the seismic response patterns of different subway stations. Figure 16 and Figure 17 present a comparative analysis of structural damage between the two station models under the Chi-Chi wave and the Northridge wave, respectively, with varying input amplitudes.

Figure 16.

Comparison between structural damage of subway stations with different beam–column joints under the Northridge wave.

Figure 17.

Comparison between structural damage of subway stations with different beam–column joints under the Chi-Chi wave.

Overall, as the amplitude of the input ground motion increases, both subway models exhibit a marked upward trend in calculated structural damage. The comparison indicates that the structural damage is most severe under the excitation of the Chi-Chi wave. As shown in Figure 17, the compressive damage within the subway station is relatively minor, whereas the tensile damage is more pronounced. When the seismic wave amplitude is less than 0.25 g, the compressive damage in most parts of the station structure generally does not exceed 0.1. Even under the maximum amplitude scenario, the extreme value of compressive damage remains below 0.2. In contrast, once the ground motion amplitude increases to 0.15 g, the tensile damage value at the aforementioned locations exceeds 0.9, reaching the threshold for concrete cracking and failure.

For the subway station employing traditional rigid column–beam connections, damage primarily occurs at the junctions between sidewalls and floor slabs, in the connection zones between columns and beams, and at the upper and lower extremities of the center columns. When the connection type is switched to isolation bearings, structural damage within the center columns and beams nearly disappears entirely, with damage confined mainly to the junctions between sidewalls and slabs. These comparative results demonstrate that the use of isolation bearings can effectively mitigate damage to the columns and beams of a subway station under horizontal seismic action, thereby enhancing the post-earthquake load-bearing performance of the center columns.

On the other hand, it is noteworthy that when the input amplitude of the Chi-Chi wave does not exceed 0.15 g, the local damage in components such as sidewalls is greater in the subway station model with isolation bearings compared to the model with traditional rigid connections. This indicates that while the use of isolation bearings effectively reduces damage levels in columns and beams, it may lead to an increase in damage severity for other structural components.

Once the input ground motion amplitude reaches 0.25 g, the structural damage at key locations in the traditional rigid connection model begins to exceed that in the isolation bearing model. The underlying reason for this shift is that as the ground motion intensifies, damage at the traditional rigid column beam connections becomes increasingly severe. When the structural damage at the upper and lower extremities of the center columns across different stories reaches a certain threshold, their contribution to the overall load bearing capacity of the model diminishes progressively. Consequently, this capacity eventually falls below the functional level maintained by the isolation bearings. This leads to a significant redistribution of internal forces within the overall station structure, causing a substantial rise in damage to other components and ultimately surpassing the damage levels observed at corresponding locations in the isolation bearing model.

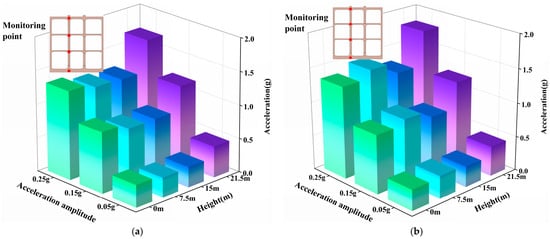

3.4. Internal Forces at Different Locations of Subway Stations

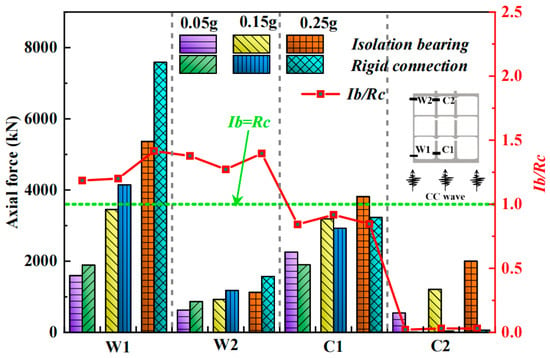

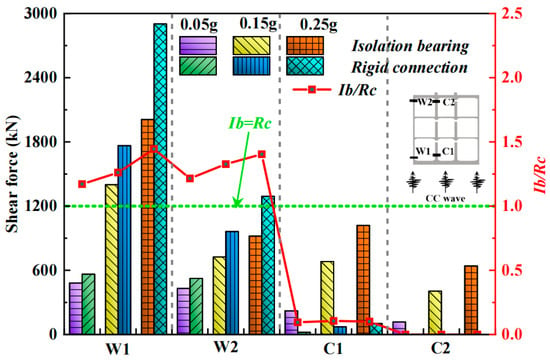

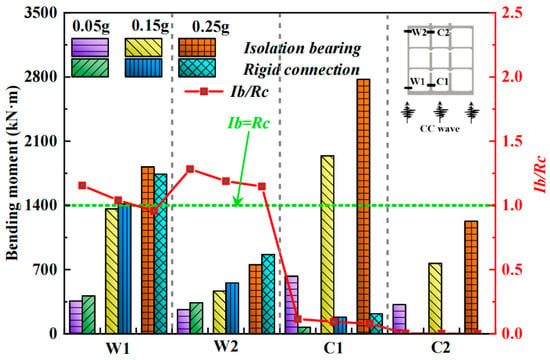

Taking the internal forces at typical locations of the sidewalls and center columns under the Chi-Chi wave excitation as an example, this section further analyzes the influence of beam–column connection types on the seismic response of a multi–story, multi–span subway station in a saturated site. Figure 18, Figure 19 and Figure 20 present a summary of the axial forces, shear forces, and bending moments for various cross–sections corresponding to different acceleration amplitudes.

Figure 18.

Comparison between peak axial forces at different locations of subway stations with different beam–column joints under the Chi-Chi wave.

Figure 19.

Comparison between peak shear forces at different locations of subway stations with different beam–column joints under the Chi-Chi wave.

Figure 20.

Comparison between peak bending moments at different locations of subway stations with different beam–column joints under the Chi-Chi wave.

As shown in Figure 18, for the subway station structure equipped with rubber isolation bearings, compared to the traditional rigid-connection model, the axial forces near the connections between the sidewalls and the base slab increase, while the axial forces in the center columns decrease. Notably, the axial force in the top story center column is reduced to a nearly negligible level. Specifically, as the ground motion amplitude increases, the difference in sidewall axial forces between the two models also grows. Under the 0.05 g scenario, the difference in sidewall axial force between the different models is approximately 20%, which rises to nearly 40% under the 0.25 g scenario. The opposing trends in axial forces for the sidewalls and center columns indicate that altering the beam–column connection type can effectively reduce the forces acting on the center columns, but also leads to a significant increase in the forces sustained by the sidewalls.

Furthermore, with the use of isolation bearings, the center columns no longer undergo strong forced motion due to the allowance for slip at the beam–column interface. Consequently, the shear forces at locations C1 and C2 experience a substantial decrease. As shown in Figure 20, when the ground motion amplitude is relatively small, the bending moments in the isolation bearing model are larger. However, once the ground motion amplitude increases beyond a certain level, the bending moments in the sidewalls of the rigid-connection model become greater, which is consistent with the phased variation observed in the comparative analysis of structural damage. In contrast, the bending moments acting on the center columns in the traditional rigid connection model are significantly larger than those in the isolation bearing model.

In summary, after adopting isolation bearings, the axial forces, shear forces, and bending moments acting on the center columns are all significantly reduced. This effectively helps control damage to the center column structures at each story during seismic events. However, the axial and shear forces at the sidewalls experience a considerable increase, leading to a certain degree of elevation in structural damage to the sidewalls under earthquake action. Considering that the changes in sidewall internal forces do not result in a significant impact on their damage, the cost of using isolation bearings to reduce the forces on the center columns is limited and acceptable.

4. Seismic-Behavior-Based Sustainability Analysis of Subway Stations

Four core seismic response metrics, acceleration, column rotation, structural damage, and structural internal force, are selected to establish quantitative connections to economic, environmental, and social sustainability outcomes, rooted in the measured seismic response disparities between the two subway station structures. Specifically, post-earthquake repair cost and construction waste emission are tied to differences in the scope and severity of structural damage, while casualty risk and traffic function recovery speed are closely associated with acceleration and column rotation distribution characteristics. In addition, the steel and concrete consumption are directly related to the structural internal force.

Compared to the conventional rigid beam–column connection, the station with rubber isolation bearings exhibits minimal change in sidewall acceleration. However, the height-wise distribution patterns of central column acceleration, lateral displacement, and rotation undergo dramatic alterations. In the conventional station, column rotations are largest at the bottom story and smallest at the top story. Conversely, the station with rubber isolation bearings shows the opposite trend. That is, minimum rotations at the bottom story and maximum at the top. Slip at the beam–column interface exceeds 20 mm when the input seismic wave amplitude reaches 0.25 g. Regarding internal force distribution, isolation bearings effectively reduce axial force, shear, and bending moment in the center columns across all stories, while axial and shear forces in the sidewalls increase substantially, approaching 40% under the 0.25 g scenario. In terms of structural damage, the damage in the conventional station is primarily tensile, concentrated at sidewall–slab joints, beam–column joints, and center columns at each level. On the other hand, the isolation station experiences damage only at sidewall–slab joints, significantly mitigating damage to center columns and beams, enhancing the post-earthquake load-bearing capacity of the columns, and reducing overall damage extent and severity. The damage-mitigation effect of the isolation bearings becomes more pronounced with increasing seismic intensity. These seismic performance disparities directly lead to significant differences in the life-cycle sustainability of the two structural systems.

Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 lists the sustainability comparison of subway stations with varied bearing configurations at beam–column joints from economic, environmental, and social perspectives, respectively, based on the seismic performance obtained in Section 3. In terms of economic sustainability, the cost differential between the conventional and isolation stations presents a “short-term versus long-term” trade-off. The conventional station, avoiding the additional cost for purchasing and installing isolation bearings, has a lower initial investment. However, from a life-cycle perspective, its broad damage distribution and high severity result in elevated post-earthquake repair costs. Post-earthquake, the conventional station requires extensive repair of multiple damaged zones, including sidewall-slab joints, column-beam joints, and center columns at each level, covering core load-bearing components. Based on the damage area ratio from seismic analysis, repair costs can reach 35–50% of the total structural cost for scenarios above 0.25 g. Furthermore, damage to core components like center columns substantially prolongs the repair period, during which subway service suspension generates massive operational losses and indirect economic impacts. In contrast, while the isolation station has a higher initial investment and requires moderately enhanced sidewall reinforcement to accommodate increased internal forces, post-earthquake repair is localized to sidewall-slab joints. The repair cost is only 15–20% of that for the conventional station, the repair duration is significantly shortened, and service suspension losses are reduced by over 80%. Moreover, the stable post-earthquake bearing capacity of the center columns in the isolation station eliminates the need for large-scale strengthening or replacement, further reducing life-cycle maintenance costs. Considering a design service life of 30–50 years, the total life-cycle economic cost of the isolation station can be 25–30% lower than that of the conventional station.

Table 4.

Economic sustainability comparison of subway stations with varied bearing configurations.

Table 5.

Environmental sustainability comparison of subway stations with varied bearing configurations.

Table 6.

Social sustainability comparison of subway stations with varied bearing configurations.

From an environmental sustainability perspective, the core difference lies in the material consumption, construction waste generation, and construction disturbance triggered by seismic damage. Large-scale post-earthquake repair of the conventional station consumes substantial amounts of materials, generating 900–1300 tons of construction waste per 10,000 m2 of station area. Waste steel and concrete from damaged components are difficult to recycle efficiently, leading to severe resource waste. The large-scale repair activities also cause dust and noise pollution, causing secondary disturbance to the surrounding soil and atmosphere. Additionally, the production of new materials increases energy consumption and carbon emissions from processes like mining and cement calcination. Under a 0.25 g seismic scenario, the carbon emissions during the repair phase increase by 70–85% compared to the initial construction phase. For the isolation station, due to localized and minor damage, the material required for post-earthquake repair is only 20–25% of that for the conventional station. Construction waste generation drops to 150–300 tons per 10,000 m2, with recyclability exceeding 60%, significantly alleviating environmental pressure. Furthermore, the repair work for a subway station with rubber isolation bearings is small in scale and short in duration, causing negligible disturbance to the surrounding ecological environment. As core components like center columns do not require repeated replacement, resource consumption and environmental load from material production are reduced, demonstrating significantly better ecological friendliness than the conventional station.

Regarding social sustainability, the core differences lie in personnel safety assurance, the maintenance of urban transport functionality, and the enhancement of public trust during earthquakes. Severe damage to core components like center columns and beam–column joints in conventional stations can easily trigger column instability and local collapse under seismic action. The distribution characteristic of maximum column rotation at the bottom story heightens the risk of casualties in that area. Under a 0.25 g seismic scenario, the probability of casualties within the station is three to four times higher than in the isolation station. Concurrently, damage to core components drastically reduces the overall load-bearing capacity of the station structure, necessitating long-term service suspension for repair. This disrupts the integrity of the urban transport network, affecting daily commutes and emergency logistics, thereby exacerbating social instability. By optimizing the damage state of center columns, the isolation station significantly enhances overall structural stability. The distribution of minimum column rotation at the bottom story reduces collapse risk in the densely populated lower areas. Since only localized damage occurs without affecting the core load-bearing function, service can be restored rapidly post-earthquake, ensuring the continuity of the urban transport lifeline and providing critical support for emergency response. Moreover, the stable seismic performance and significant damage mitigation of the isolation station can elevate public trust in urban infrastructure safety and strengthen the city’s overall resilience to seismic disasters, solidifying the safety foundation for sustainable social development.

In summary, by reshaping seismic response distribution patterns and optimizing structural damage characteristics, the station with rubber isolation bearings demonstrates superior sustainability across life-cycle economic cost control, environmental impact reduction, and social safety assurance. The advantages in seismic performance of a subway station with rubber isolation bearings synergize positively with sustainability objectives. Although the conventional subway station has a lower initial investment, its shortcomings of widespread and severe seismic damage lead to escalated life-cycle economic, environmental, and social costs, resulting in weaker sustainability performance. This gap becomes even more pronounced under moderate to strong seismic scenarios.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a numerical model was developed to conduct three-dimensional seismic performance analyses of subway station structures with different beam-column connection types. An analysis was carried out to investigate the influence of beam-column connection types on the seismic performance of subway stations under various ground motion input conditions. Subsequently, based on the post-earthquake column rotations, structural damage, and internal force variations observed in subway station structures with different connection types, a sustainability analysis of the stations was performed from economic, environmental, and social perspectives, taking seismic performance as the foundation. This analysis compared the sustainability differences arising from different beam-column connection types in subway stations. The main conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- By replacing rigid beam–column connections with laminated rubber isolation bearings, the axial forces, shear forces, and bending moments acting on the center columns at each story of a subway station under seismic action can be effectively reduced. However, this leads to a substantial increase in both the axial and shear forces within the sidewalls, with an approximate rise of 40% under the 0.25 g scenario. The use of isolation bearings can effectively mitigate damage to the center columns and beams across all stories of a subway station under seismic action. This significantly enhances the post-earthquake load-bearing performance of the central columns and substantially reduces both the extent and severity of damage to the overall subway station structure. The more severe the structural damage to the subway station under earthquake excitation, the more pronounced the beneficial effect provided by the isolation bearings becomes.

- (2)

- Stations retrofitted with rubber isolation bearings, through a redistribution of seismic demands and an optimized damage pattern, exhibit enhanced sustainability across economic, environmental, and social metrics throughout their service life. This creates a positive synergy between seismic safety and sustainable development objectives. Conversely, the conventional subway station with rigid beam–column connection, despite its lower upfront cost, incurs significantly higher life-cycle costs and exhibits poorer sustainability performance due to its vulnerability to widespread damage during earthquakes, leading to a weakness that becomes increasingly critical with greater seismic intensity. It is recommended that rubber isolation bearings be more widely adopted in the construction of future metro stations to enhance the sustainability of the structure following seismic events.

This study primarily focuses on conducting a sustainability evaluation for subway stations with different beam–column joints based on their seismic performance, with the relevant contents mainly concerning the operation and maintenance phase of the subway stations. The findings in this study are universally applicable to most metro station structures with similar bearing configurations at beam–column joints. However, the adoption of different beam–column joints entails distinct implications for energy consumption, economic benefits, and environmental impact during the construction phase and the demolition phase at the end of the service life. In addition, the influence of ground motion spectral characteristics and geological conditions has not been discussed in detail. A more systematic analysis regarding the sustainability differences arising from various beam–column joints in subway stations, the influence of spectral characteristics of ground motion, and geological conditions is warranted, which will be future work. Such an analysis should encompass all stages from construction to the end-of-life disposal of the stations, in order to comprehensively reveal the sustainability variation patterns associated with different beam–column joints.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft, and funding acquisition, J.L.; formal analysis, investigation, software, and writing—original draft, S.S.; methodology, software, writing—review and editing, and funding acquisition, G.Z.; and resources, validation, and writing—review and editing, W.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported by the Tianjin Natural Science Foundation Project (Grant Nos. 25JCQNJC00290, 25JCQNJC00300), which are gratefully acknowledged.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Song, L.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wu, X. Characteristics of Noise Caused by Trains Passing on Urban Rail Transit Viaducts. Sustainability 2025, 17, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Shi, Z.; Lv, X.; Zhang, G. Optimization of Combined Urban Rail Transit Operation Modes Based on Intelligent Algorithms Under Spatiotemporal Passenger Imbalance. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Chen, Y.; Shangguan, L.; Zhou, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q. Evaluation of Urban Rail Transit System Planning Based on Integrated Empowerment Method and Matter–Element Model. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zou, R. Dynamic evacuation path planning for subway station fire based on IACO. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 86, 108828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Liang, J.; Ba, Z. Effect of fluid–solid coupling on seismic performance of underground structures in water–saturated soil: A case study of a 3–story 3–bay subway station. Soil Dynam. Earthq. Eng. 2024, 178, 108477. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, P.; Chen, Z. Deep learning for nonlinear seismic responses prediction of subway station. Eng. Struct. 2021, 244, 112735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Xu, H.; Liu, T.; Wang, Q. Failure mechanism of subway structure with different central columns based on Daikai Station. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 787, 12123. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, H.; Bobet, A.; Fernández, G.; Ramírez, J. Load Transfer Mechanisms between Underground Structure and Surrounding Ground: Evaluation of the Failure of the Daikai Station. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2005, 131, 1522–1533. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, J.; He, S.; Qiu, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, K.; Wang, J. Characteristics of seismic disasters and aseismic measures of tunnels in Wenchuan earthquake. Environ. Earth Sci. 2017, 76, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, H.K.; Tran, T.H. Evaluate and Analyze the Characteristics of Subway Transfer Station Facilities Based on Universal Design from the Cases of South Korea. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewunruen, S.; Peng, S.; Phil–Ebosie, O. Digital Twin Aided Sustainability and Vulnerability Audit for Subway Stations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loy–Benitez, J.; Li, Q.; Nam, K.; Yoo, C. Sustainable subway indoor air quality monitoring and fault–tolerant ventilation control using a sparse autoencoder–driven sensor self–validation. Sust. Cities Soc. 2020, 52, 101847. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Feng, H.; Xi, X. Monitoring and autonomous control of Beijing Subway HVAC system for energy sustainability. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2017, 39, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, T.; Lu, W.; Wu, L.; Rong, W. Coupling coordination evaluation and driving factor analysis of economic performance and social equity in rail transit station areas. Front. Archit. Res. 2025, 14, 1450–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wu, M.; Yuen, K.F. A novel method to assess urban multimodal transportation system resilience considering passenger demand and infrastructure supply. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 238, 109478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhuang, H.; Wang, W.; Jin, L.; Dong, Z.; Wang, P. Effect of Different Types of Middle Columns on the Seismic Performance of Single–Story Subway Station Structure. Shock Vib. 2021, 2021, 7617782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Ledesma, A.; López–Almansa, F. Novel seismic design solution for underground structures. Case study of a 2–story 3–bay subway station. Soil Dynam. Earthq. Eng. 2022, 153, 107087. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Zhuang, H.; Wang, W.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, G. Seismic performance and effective isolation of a large multilayered underground subway station. Soil Dynam. Earthq. Eng. 2021, 142, 106560. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Xu, C.; Du, X.; Naggar, H.M.E.; Jiang, J. Seismic performance and fragility analysis of underground subway station with rubber bearings. Soil Dynam. Earthq. Eng. 2022, 162, 107511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Zhao, Y.; Dong, H.; Lu, D.; Du, X. Comparative study on the seismic performance of subway stations using reinforced concrete cast–in–place columns and truncated columns. Soil Dynam. Earthq. Eng. 2023, 169, 107862. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Liu, S.; Song, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, H.; Shi, V. Environmental Risk Assessment of Subway Station Construction to Achieve Sustainability Using the Intuitionistic Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process and Set Pair Analysis. Discrete Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2021, 2021, 5541493. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, M.; Yu, L.; Dai, Z.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cao, J. Metro ridership recoverability and the built environment: Exploring station–level non–linear impacts. Transport. Res. Part D–Transport. Environ. 2025, 147, 104852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ma, W.; Chan, A. Exploring the Relationships between the Topological Characteristics of Subway Networks and Service Disruption Impact. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Zhao, W.; Zhao, G.; Wang, S.; Xie, K. Numerical study on seismic performance of a prefabricated subway station considering the influence of construction process. Structures 2024, 69, 107218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, H.; Xu, Z.; Yang, J.; Chen, S.; Zhang, J.; Chen, G. Quasi-static model test and numerical simulation of a single-story double-span underground subway station. Soil Dynam. Earthq. Eng. 2023, 173, 108099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Ding, L.; Du, X.; Xu, C.; Zhuang, H. Generalized response displacement methods for seismic analysis of underground structures with complex cross section. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2023, 22, 979–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; El Naggar, M.H.; Niu, X.; Fang, H.; Xu, C. Seismic performance of subway station fitted with rubber bearings via pushover analysis. Soil Dynam. Earthq. Eng. 2025, 196, 109487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, Z.; Liang, S.; Li, C. Isolation mechanism of a subway station structure with flexible devices at column ends obtained in shaking–table tests. Tunn. Undergr. Sp. Tech. 2020, 98, 103328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Z. Experimental and analytical investigations on compressive behavior of thick rubber bearings for mitigating subway–induced vibration. Eng. Struct. 2022, 270, 114879. [Google Scholar]

- Deeks, A.J.; Randolph, M.F. Axisymmetric time–domain transmitting boundaries. J. Eng. Mech. 1994, 120, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lu, Y. A direct method for analysis of dynamic soil–structure interaction based on interface idea. Dev. Geotech. Eng. 1998, 83, 261–276. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, J. Study on wave motion input and artificial boundary for problem of nonlinear wave motion in layered soil. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2004, 23, 1169–1173. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Liang, J.; Zhang, J.; Ba, Z. Nonlinear seismic response of 3D canyon in deep soft soils. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2017, 39, 1196–1205. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.