Abstract

Globally, the architecture, engineering, construction, and operations (AECO) industry faces rapid urbanization and environmental urgency. However, developing economies often lack the strategic capacity to utilize BIM for sustainable development. This study addresses this gap by developing a strategic, evidence-based BIM adoption framework tailored to the Mongolian context. Originating in the health sector, the ADAPTE process is a systematic method that enables the cost-effective adaptation of existing high-quality guidelines to new target contexts. The research applies a framework adaptation methodology, based on the adaptation phase of the ADAPTE process, to recontextualize benchmark international strategies for the specific environment of Mongolia. In the result, our work proposes a national BIM adoption framework which follows a three-phase implementation timeline (2027, 2030, and 2035) as per ISO 19650 maturity stages. Additionally, it has a three-point action plan of policy/legal systems, common resources, and promotion in the sphere of industry, people, and technology. The result offers a practical framework for Mongolia to advance the adaptation of BIM practices, positioning digital transformation as a catalyst for sustainable development. Furthermore, the methodological framework developed in this work serves as a scalable blueprint for other developing economies to systematically craft their own context-specific strategies.

1. Introduction

The architecture, engineering, construction, operations (AECO), and infrastructure industry globally is at a critical juncture, facing the dual pressures of rapid urbanization and urgent environmental crisis. The construction sector continues to be one of the primary consumers of the world resources, consuming about 42% of all the energy used in the world, 30% of all raw materials, and 25% of the freshwater abstractions across the globe [1]. In addition, it produces a large percentage of waste streams and carbon emissions in the world [2,3,4,5,6], accounting for approximately 25% of solid waste generation [7] and 37% of energy use and process-related carbon emissions associated with building operations and material production [8]. This undeniable environmental effect has triggered a quest by the industry across the board to find revolutionary solutions that can drive development into a more sustainable and efficient pathway [9]. Building information modeling (BIM), in this regard, has been a key enabling factor as it has emerged as an entire process that fundamentally alters the project delivery and asset management practice [10,11]. The BIM-induced sustainability value is based on the rich nature of the data that allows it to support strong collaboration, comprehensive energy simulation, life-cycle assessment (LCA), and the reduction of construction waste, thus offering a digital basis of sustainable development [12,13,14,15,16,17,18].

Regardless of the highly reported benefits of BIM, there exists a significant gap in BIM usage between developing and developed countries [19]. It is well known that empirical studies reveal the massive adoption of BIM at a large scale in economies, like the UK, Singapore, and the US, and that it has not been just a market push effect. Instead, it was hastened through clear, top-down, government-leading strategic roadmaps and policy tools [20,21,22,23]. These national strategies provided the guide while creating the necessary market demand, necessary standards, and a supportive collaborative atmosphere where implementation occurs. Many developing countries, on the contrary, have exhibited fragmented and slow adoption [19]. A policy vacuum is repeatedly noted as the main obstacle, and it triggers a wave of related problems: the lack of national standards, perceived high costs, significant professional skills gaps, interoperability concerns, and the lack of knowledge among clients [24,25,26,27].

The Mongolian construction industry is a rapidly growing sector but is facing serious economic and environmental problems, which demonstrates this particular policy gap [28]. The country does not have the official national framework that would govern the implementation of digital technologies in a way that would ensure the principle of sustainable development. This policy gap presents a significant challenge to the advancement of structural modernization within the industry. New studies are increasingly showing that default, one-size-fits-all roadmaps are inefficient; instead, strategies need to be carefully crafted to incorporate the unique regulatory, economic, and industrial landscape of the country being adopted [19,29]. Although academic research has already suggested such nation-specific frameworks for countries like Pakistan [30], Egypt [25], Nigeria [24], India [26], and Zambia [31], there is no systemic, evidence-based roadmap for the Mongolian case. It requires the industry to be approached in a way that may go beyond listing the challenges, and there is a need to systematize the international strategies that have been in place and adapt them to the local realities.

In this respect, the present study aims at building a strategic, context-specific approach to national BIM adoption in Mongolia, where digital transformation becomes the driver of sustainable development. Instead of reinventing the wheel, which is to develop a strategic framework from zero, the research uses the ADAPTE process, which is a methodology initially developed to adapt clinical guidelines [32,33]. The protocols of this process, which are called modules, were recontextualized for the scope of our research, then applied by systematically adapting the established strategies of the four benchmark case countries: the UK, Germany, Singapore, and South Korea. The benchmark cases were identified through an analysis of 38 framework sources and practices related to BIM adoption. By recontextualizing the ADAPTE process, we developed a creative methodological framework to generate a roadmap and detailed action plans that are not only aspirational but also systematically calibrated to the specific regulatory and economic realities identified in the authors’ preceding diagnostic study [28]. Key findings of the diagnostic study are covered in Section 2 of this work. That foundational research employed a hybrid SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) and PESTLE (political, economic, social, technological, legal, environmental) analysis to systematically identify and categorize the specific institutional and technical friction points characterizing the Mongolian construction industry. Methodologically, PESTLE is a macro-environmental scanning tool to assess dynamic external variables beyond industrial control, and SWOT is a strategic tool to integrate these findings by matching internal capabilities with external realities [28,34,35]. The present framework has been empirically grounded by the close combination of the SWOT and PESTLE analyses in our earlier empirical work and, consequently, the strategic roadmap will be based on set, evidence-based environmental conditions rather than theoretical assumptions. In this current work, we expand on the past work to build a fully comprehensive strategic framework for Mongolia to assist in BIM adoption. In the literature review, we argue and evaluate how the previous findings of the hybrid SWOT and PESTLE analysis actually connect to the global picture of converging factors among developing economies in relation to BIM readiness and highlight how the context is linked to BIM adoption practices.

Addressing the critical policy vacuum explored in this current work and the multidimensional barriers identified in the Mongolian construction sector via the previous study, this study aims to develop a comprehensive strategic framework.

To achieve this, the research addresses the following three key questions:

- RQ1: How can the ADAPTE mechanism, originally a clinical guideline methodology, be systematized to filter and transpose mature international BIM standards (the UK, Singapore, South Korea, and Germany) into the specific regulatory and economic context of a developing economy?

- RQ2: Based on the integrated SWOT and PESTLE diagnostic evidence of Mongolia’s construction sector, what specific framework architecture is required to bridge the gap between the identified potentials and the existing institutional stagnation?

- RQ3: How can maturity stages be operationalized into a phased strategic roadmap and detailed, multi-pillar action plans (industry, people, and technology) to drive sustainable digital transformation?

The strategic framework development is supported by the structure of the rest of this paper. Part 2 is a critical literature review on national BIM strategies and their connection to sustainable development, reflecting that there is a policy vacuum in developing economies. Section 3 outlines the methodology used; in particular, how the ADAPTE process is utilized to screen and adapt international best practices. Section 4 provides a comparative analysis of the global BIM roadmap that has been applied to identify benchmark strategies. Section 5 provides the proposed strategic framework for Mongolia, and Section 6 provides a detailed action plan for implementation. Lastly, Section 7 presents the strategic implications of sustainable development and Section 8 provides the conclusions.

2. BIM Adoption and the Need for a National Policy Framework

The synergy of BIM and sustainable construction are part of the main theme in current research in AECO. BIM is considered one of the cornerstone technologies in green building, which offers the digital platform required to conduct sophisticated sustainability analyses [12,15,36]. Its functions enhance the integration and evaluation of the three dimensions of sustainability, namely, environmental, economic, and social [37,38]. BIM can be used in practice to support a life-cycle assessment (LCA) [11,39] and the optimization of energy and water savings through simulation [4,16,18], accurate quantification to reduce construction and demolition (C&D) waste [17], and the simplification of the complex documentation to support green building standards like LEED or BREEAM [40,41]. This development transforms sustainability from a checklist-based compliance tool into a holistic, performance-oriented design process [14,41]. Therefore, enabling a higher rate of BIM adoption in developing countries through strategic frameworks will provide a boost to sustainable development in many emerging economies.

2.1. The Policy Vacuum: Critical Synthesis of BIM Strategies in Developing Economies

BIM adoption in the world, however, presents two approaches in the global narrative. Top-down initiatives that are government-led have been overwhelmingly seen to be successful in developed economies [19,22]. A more successful example is the 2011 Construction Strategy by the UK Government prohibiting all centrally procured public projects from using the less-advanced BIM Level 2 after 2016, which was essentially a marketplace consolidation, standardization, and industry-wide capability creation initiative [20,21]. On the same note, the multi-year roadmaps Singapore put in place and its Construction and Real Estate Network (CORENET) e-submission system directly incorporated BIM in the regulatory approval process and, as such, digital adoption has become a national productivity and policy matter [22,23]. There have been several successful top-down adoptions, and the US is no exception, with agencies such as the General Services Administration (GSA) and the US Army Corps of Engineers developing their own BIM roadmaps and standards many decades ago to improve asset delivery and life-cycle management [20,21,24]. Such scenarios indicate that national policy frameworks are a vital catalyst towards breaking initial market inertia and harmonizing industry players.

In striking opposition, the literature on developing nations exposes a field characterized by fragmented, bottom-up adoption, which is usually crippled by a drastic policy vacuum [19,27]. Research conducted in a variety of developing countries, such as Nigeria [24], Egypt [25], India [26], Pakistan [27,30], Kazakhstan [42], Malaysia [36,43], Ethiopia [38], and Indonesia [44], synthesized in Table 1, all find a similar set of related barriers.

Table 1.

Key barriers to BIM adoption in developing countries.

As Table 1 demonstrates, strategic and institutional barriers are repeatedly identified in the literature, supporting the argument that they represent a critical category in BIM implementation challenges. The lack of a national policy framework is not just one barrier among the others; it is the source of the others. Published in 2024, Olugboyega’s research proposed and tested the hypothesis that specific strategies can significantly reduce BIM adoption barriers, particularly preliminary ones [47]. This study was conducted in the South African context among BIM practitioners. One of the hypotheses was that these strategies would assist in BIM barrier reduction and promote the adoption process. Using structural equation modeling, all proposed hypotheses were supported, confirming that essential strategies, namely training, capacity-building, and maturity-based approaches, accelerate barrier reduction and promote adoption [47]. Interpreting these findings in reverse suggests and supports the stated problem that the absence of a national BIM adoption policy acts as a root barrier, amplifying other obstacles. Implementing policy-driven strategies, like those aligned with BIM maturity frameworks, would therefore help lower both preliminary and sustained barriers. Another aspect of the lack of policy frameworks is that the absence of government requirements discourages client demand; coupled with high expenditures during its inception, this discourages firms from investing. Even in the absence of mass investment and demand, academic institutions are not pressured to create newer curricula, and this continues to worsen the problem of the shortage of skills [25,26,30]. This forms an endless cycle of low adoption that cannot be overcome by individual companies, especially the small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that are, in reality, the dominant industry players in countries like Nigeria and Malaysia [36,51,54].

Thus, a distinct consensus in the literature forms: the adoption of technology is not only a technical issue but also a convoluted socio-technical issue that must have a holistic comprehensive and top-down methodological approach [19,55]. And yet, the literature too is cautious to the extreme in warning against a one-size-fits-all approach [19,29]. The roadmaps of the highly developed, centralized economies such as Singapore cannot be directly applied to developing countries which might have varying economic capacities, industry structure, regulatory maturity, and technological infrastructure [19,29]. This has inspired more recent and more topical volleys of work on the creation of context-specific national models, as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Examples of proposed national BIM frameworks/roadmaps for developing economies.

The tendency presented in Table 2 shows a coherent pattern: the specific priorities have only slight differences, whereas the basic requirements of a national roadmap in a developing country are still strikingly similar. The role of the government in the areas of standardization, the development of awareness, and support is at the center of all the discovered priorities [19,25,30,38]. The aggregate effect of this body of work is the necessity of a national strategic framework and the definition of its key elements to address the policy vacuum.

2.2. Construction Sector of Mongolia

The construction sector is significantly influenced by BIM as it advances digital transformation. To contextualize the scale of transformation needed in Mongolia, it is necessary to define the sector’s current economic and physical volume. In the Mongolian Statistical Yearbook 2024, it is reported that the construction sector has followed a continual upward path, with total production climbing from MNT 5.44 trillion in 2020 to MNT 9.16 trillion (approximately USD 2.7 billion) in 2024 [56]. The expansion of the physical asset base has occurred concurrently with this economic growth. Between 2020 and 2024, the national housing stock (measured in floor area) increased by 31.8%, rising from 18.3 to 24.1 million square meters [56]. This notable augmentation in constructed assets is congruent with broader demographic trends; during the same four-year interval, the urban proportion of the population rose from 68.0% to 70.3% [56], thereby reinforcing a construction footprint that is increasingly concentrated in metropolitan areas.

Publicly accessible data for building inventory at the national level for Mongolia is not available, and official statistics often only report construction activity and capital formation rather than counts and types of buildings in the national stock. Thus, in order to provide the readers sufficient context, the capital city of Ulaanbaatar is utilized herein to illustrate the prevailing circumstances of the constructed environment in Mongolia. This emphasis is driven by the capital’s demographic concentration. In the year of 2024, the total population of Mongolia stood at around 3.545 million individuals, with Ulaanbaatar containing approximately 1.768 million residents [56], which constituted nearly half of the nation’s inhabitants. As a result, Ulaanbaatar epitomizes the most significant concentration of economic activity and the constructed environment, functioning as a robust predictive indicator for the national building stock.

To illustrate the composition of this representative stock, we draw on findings from a building inventory study. A study conducted by Tumurbaatar et al. [57] documented 32,550 constructions in the capital region. The dataset illuminates both the material composition of the physical stock and the prevailing deficiencies in information management. Notably, the preponderance of the inventory, comprising 17,883 buildings, or 54.94%, is categorized as having an ‘unknown’ structural type. Among the identified structural typologies, timber constructions constitute the predominant category, accounting for 22.86% (7444 buildings). This is succeeded by more engineered systems: reinforced concrete (RC) comprises 8.97% (2924 buildings), masonry constitutes 5.79% (1887 buildings), and precast structures represent 5.13% (1673 buildings). Other structural categories, which include RC with shear walls and steel frameworks, hold a marginal proportion of the stock, ranging from 0.48% to 0.89%. Concerning vertical density, the research highlights that the physical environment is largely low-rise. The data indicates that 27,454 buildings are situated within the 1–3 story range, representing the overwhelming majority of the stock. On the opposite side, high-rise structures are quite uncommon, with only 306 buildings cataloged as having 16 stories or more [57]. This prevalence of structurally undefined assets underscores the critical urgency for a digital framework to standardize information management and assure asset quality. Furthermore, as the sector pivots toward increasingly complex engineered systems, a strategic framework for BIM adoption would serve as the essential strategic mechanism to connect this information gap and enable the systematic modernization of the national building stock.

2.3. The Diagnosis: Status of Mongolia in the Context of BIM Adoption

Previously, Table 1 and Table 2 provided results regarding the extensive literature review on BIM adoption challenges and the existing national BIM frameworks in developing countries. From each case, it was evident that the formulation of an effective roadmap still demands evidence that is sensitive to specific local conditions. Moreover, the literature consistently emphasized a policy vacuum as one of the key barriers in developing economies, suggesting that the absence of coordinated national strategies has been a crucial factor for hindering success. Mongolia is an example of such global policy vacuums. Being a fast-growing post-transition economy marked by high urbanization, it is confronted by the double challenge of modernizing its building industry to accommodate housing and infrastructure needs as well as applying high pressure on limited resources and severe climatic conditions [28]. In order to get out of generalized assumptions, one must analyze the particular structural and institutional reality of the AECO industry in Mongolia.

The authors, Erdene et al. (2025), in a previous study conducted a comprehensive diagnostics process that employed a hybrid SWOT and PESTLE analysis to rigorously map the readiness profile of the Mongolian construction industry (see Table 3) [28]. This diagnosis was a search for the points of friction within the systems that slow down digital transformation in the construction industry of Mongolia, not simply catalog the inventory of challenges. What became apparent in the analysis is a clear and severe asymmetry of the local market: a separation between the potential of the bottom-up and institutional stagnation of the top-down.

Table 3.

A hybrid SWOT and PESTLE analysis of BIM adoption in Mongolia [28].

The results of the diagnostic process point to the findings that Mongolia has a latent “Technical Readiness” (strength). In the research, a demographic phenomenon, called a youth bulge, was found, and the demographic of the population is estimated to range between 20 and 49 (43.59%) [28]. This consumer demographic is then translated into a workforce which is innately technological and accommodative of digital advancement. Moreover, the BIM authoring tools have been showing increasing expertise in the hands of the private sector prompted by the demand for foreign investment and the strict construction engineering criteria in the mining industry. Educational programs, including the development of more official training facilities in the Mongolian University of Science and Technology, show that the human capital base is undergoing construction, although it should be pointed out that it concentrates on software skills more than on process management [28].

However, this bottom-up momentum is halted by the “Strategic and Institutional Weaknesses.” As the hybrid SWOT and PESTLE analysis revealed (see Table 3), the lack of industry interest is not the major threat to its adoption, but a severe risk of a critical standardization gap and critical legal uncertainty [28]. The existing regulatory framework is still tied to the old processes; an example of this is the 27 categories of construction permits that the Urban Development Agency mandates, which continue to require 2D CAD-based construction drawings to be archived and approved. This regulatory inflexibility makes BIM an optional overhead instead of an added value standard, which creates a discontinuity between the digital models made by the private companies and the dumbed-down 2D drawings, made to comply with the processes of the archaic compliance requirements of the masses.

It is this imbalance that is characterizing the existing policy gap in Mongolia: this is not a gap in capability, but a gap in governance. This is especially important as far as sustainable development is concerned. The diagnostic study also underlines the high level of extremity in the continental climate of Mongolia, according to which the active construction period is restricted to approximately 6 months [28]. Here, BIM is not an option but a necessity in sustainability; the functionalities of thermal simulation and prefabrication allow for the reduction of waste and the maintenance of project viability even in a limited weather range. A missed opportunity of both environmental and economic efficiency, however, lies in the absence of a policy framework that would encourage this sustainable digital workflow.

In turn, a generic roadmap that was brought over from a developed economy would not respond to this particular asymmetry. The Mongolian situation demands an approach that would capitalize on the fact that the technical potential of the workforce is extensive, and that the obstacles to work presented by the legislation are to be confronted on an aggressive level, as was also established in the diagnostic investigation. The particular profile, that is, high potential but low governance, introduced in [28] provides the contextual evidence for one of the key inputs in this study. It outlines the filtration requirements required in the next roadmap development process and will make sure the best practices in the world are not simply applied but are adapted successfully to address the particular gap in Mongolian policies.

2.4. Strategic Framework Development Approach

Section 2.1 outlined by the literature review, which identified a widespread policy vacuum in developing economies, in contrast to the successful top-down directives in developed economies. This was further narrowed down to the Mongolian context in Section 2.3, which utilized contextual diagnostic evidence to identify a critical governance gap where technical potential currently outpaces institutional support. This gap, though, cannot be filled by diagnosis alone; it needs a rigorous process where such findings are turned into policy action. The current literature on the topic has provided fundamental groundwork, as shown in Table 2, to determine the exact barriers and drivers in developing economies. These works have been crucial in stipulating what hinders adoption successfully and offering frameworks based on local diagnostic analyses. The logical follow-up of this scholarly trajectory is to now address how these valuable insights can be systematically operationalized. The methodological difficulty is to relate these barrier-based diagnoses to the strategic components of the developed world, where there are roadmaps of experience without either the wholesale importation of foreign standards or the unnecessary development of completely new systems.

To circumvent this complexity, this study seeks to build on the current body of knowledge by utilizing the ADAPTE process, a systematic tool to adapt guidelines to filter and to modify strategies in a rigorous manner [32,33]. This methodology constructs the framework by progressively aligning the tested strategic components in developed economies like the ones of the UK, US, and Singapore [20,21,22,23,24] to the specific resource constraints established by the contextual diagnostic evidence. With this systematic process of adaptation as the foundation of the roadmap (as elaborated further in Section 3), the current study ensures that the resulting framework does not just remain as a conceptual outline but undergoes implementation in favor of becoming a practical adaptation mechanism in the sustainable development of Mongolia.

3. ADAPTE Process-Based Context-Specific Systematic Adaptation Approach for BIM Implementation Framework Development

The development of a national-level BIM implementation framework or any other guideline-level framework development can have two types of fundamental approaches: developing an entirely new framework from zero; and systematically adopting existing high-quality practices. An international collaboration of researchers specializing in clinical practices formed a team called ADAPTE Collaboration, around the year 2005, to develop a methodology called the “ADAPTE process” for adapting high-quality guidelines [32,33]. They saw the nuance of the two approaches and the need for supporting the systematic adaptation approach. Fevers et al. and the ADAPTE Collaboration team recognized the aforementioned two types of approaches and coined them as “de novo creation” vs. “systematic adaptation” [32]. The downside of de novo creation is that it is expensive, because the development of best practice and rigorous guideline frameworks requires vast amounts of time and human and material resources. Additionally,, it can be redundant, since there may already exist a well-designed practice and, like reinventing the wheel, can result in duplicated effort. For our scenario, starting fresh means ignoring the wealth of knowledge embedded in mature, high-quality international BIM implementation roadmaps. Additionally, the financial and economic constraints faced by many developing countries call for recourse through efficient and sustainable pathways. Thus, systematic adaptation approaches like the ADAPTE process are suitable for developing our case framework model. It will be efficient and robust to leverage existing global knowledge and adapt it based on the target context. The ADAPTE Collaboration defines the guideline adaptation as “the systematic approach to consider the use and/or modification of guidelines produced in one cultural and organizational setting for application in a different context” [33].

In this research, we have utilized a methodological approach based on the core principles of the ADAPTE process. Even though the ADAPTE process was originally formalized in the health sector, the underlying logic of this process is applicable to different domains such as the construction sector. At its core, the ADAPTE process is not about medicine. It is a general and robust process for adapting complex, evidence-based frameworks from one national and organizational setting to another. The fundamental challenge of adapting a technical framework for BIM implementation from the UK or South Korea to Mongolia is structurally identical to adapting a set of recommendations for new contexts based on the ADAPTE process. In both scenarios, the core task is to ensure that the final recommendations “address specific problems relevant to the context of use” and are “suited to the needs, priorities, legislation, policies, and resources in the target setting” [33]. Therefore, the creative application of the ADAPTE process in this construction sector BIM adoption context represents a methodological innovation. It provides a robust, validated, and transparent procedural framework that enhances the defensibility of the research, moving the final output beyond mere improvised compilation. In addition, this sets the stage for a national contextual analysis, where we establish a baseline understanding of Mongolia’s unique BIM adoption landscape. The contextual SWOT and PESTLE analysis, which was conducted in the preliminary study by Erdene et al. [28], was covered in the previous section.

3.1. Recontextualization of the “Adaptation Phase Key Modules” from the ADAPTE Process

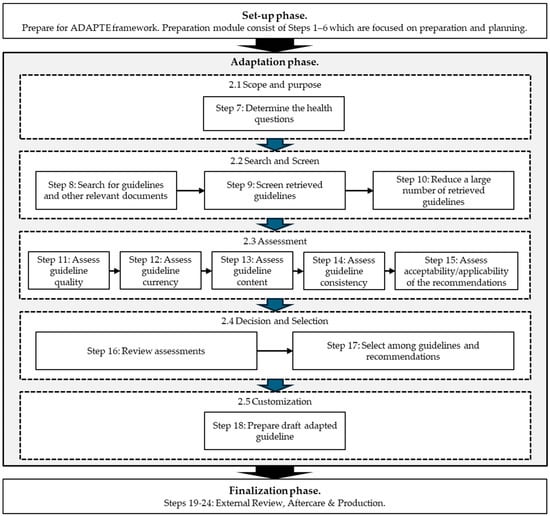

The ADAPTE process consists of three phases: set-up, adaptation, and finalization (see Figure 1). Each phase then divides into specific tasks that have their associated modules. Additionally, modules are further divided into the steps necessary to adapt guideline frameworks. In Figure 1, the ADAPTE process is summarized and visualized by the authors of this research, with a focus on the adaptation phase, and based on the guideline adaptation method proposed by Fevers et al. and the ADAPTE Collaboration teams [32]. Figure 1 is also presented to guide readers in understanding how the methodological framework of this research was derived through the ADAPTE process. In order to utilize the core principles of the ADAPTE process for our context, we have selected the adaptation phase items and recontextualized them to demonstrate that this process can be implemented in different settings, given that the structure of the adaptation process framework is similar (see Figure 2). The set-up and finalization phases from the ADAPTE process can be addressed in future research works. Considering our current research design, these phases would land outside of our research scope in developing the model process. Our focus is on creating a strategic BIM adoption framework for developing countries in a sustainable manner by adapting from existing knowledge bases and best practices, but in consideration of a specific country’s context. In other words, our methodological framework is developed by borrowing the adaptation phase modules of the ADAPTE process and is used to develop the BIM implementation roadmap and detailed action plan framework for Mongolia.

Figure 1.

Visually summarized ADAPTE process with emphasis on the adaptation phase.

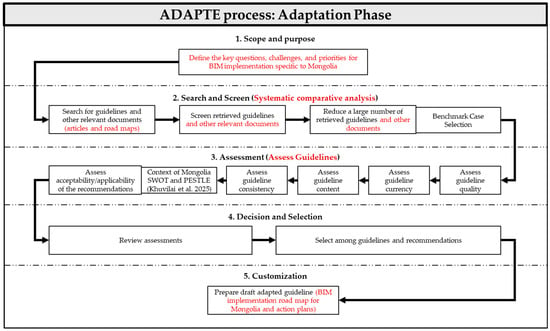

Figure 2.

Methodological framework: recontextualized adaptation phase modules, derived from the ADAPTE process. Modules highlighted in red font have been adapted through recontextualization, extension, and rewording to reflect the specific needs of this study.

The borrowed adaptation phase modules provide the systematic steps for moving from source materials to a context-validated draft (see Figure 2). To drive this adaptation engine, the study utilizes two primary data-driven inputs: the diagnostic evidence established in the authors’ preceding study [28] (serving as the macro-level context validation) and the systematic comparative analysis conducted in this research (serving as source framework practices), which synthesize the academic literature on the developing economy frameworks reviewed in Section 2 and the global BIM strategies comparison detailed in Section 4. The key modules of this phase, as applied in this study, are as follows.

- Define Key Questions (Module 2.1 → 1. Scope and Purpose): This step translates to defining the key questions, challenges, and priorities for BIM implementation specific to Mongolia. Section 2 of this study extensively delves into this part of our research and defines the scope in the narrative.

- Search and Screen Guidelines (Module 2.2 → 2. Systematic Comparative Analysis): This corresponds to the systematic comparative analysis this research conducted on the mature BIM implementation roadmaps (the UK, Germany, Singapore, and South Korea) to identify common, high-quality “source guidelines” and their core components (e.g., phased approaches, three-aspect classifications). This module follows the steps of searching, screening, and reducing redundancy. Around 29 countries’ frameworks were assessed, and 4 benchmark countries were selected during this process.

- Assess Guidelines (Module 2.3→ 3): This is the critical validation step. It involves the following:

- Establish Contextual Profile: SWOT and PESTLE results by Erdene et al. [28] covered in Section 2, which consists of the challenges and opportunities in the Mongolian construction sector.

- Step: Assess Acceptability and Applicability: This is the justifying principle of the entire methodology, where the “matching” occurs (see Section 3.2).

- Decide and Select (Module 2.4 → 4) and Customize (Module 2.5 → 5): Based on the formal assessment, a transparent process of selection (e.g., “borrowing” the phased approach), modification, and customization is undertaken to produce the draft of the adapted guideline [33].

3.2. The Systematic “Matching” and Validation Filter

The primary justification for this methodology is the rigorous application of ADAPTE’s “Step: Assess acceptability and applicability” [33]. This step provides the formal, academically defensible validation filter for the “matching” process.

It provides the transparent mechanism for running each “borrowed” recommendation (e.g., from the UK or German roadmaps) through an explicit filter of local realities. Crucially, the diagnostic evidence from previous research [28] provides the data and context that serves as the primary evidence for conducting this assessment. Where an informal approach relies on researcher judgment, this method uses local data to drive the decision.

The ADAPTE toolkit [33] requires a formal analysis of each recommendation, translated for this research as follows:

- Applicability (Resources): “Are the interventions and/or equipment available in the context of use?”

BIM Translation: Does the Mongolian construction sector have the necessary software, hardware, and internet infrastructure assumed by the source guideline?

- Applicability (Expertise): “Is the necessary expertise (knowledge and skills) available in the context of use?”

BIM Translation: Does the Mongolian workforce (engineers, technicians) possess the training required by this recommendation?

- Applicability (Constraints): “Are there any constraints, organizational barriers, legislation, policies, and/or resources… that would impede the implementation…?”

BIM Translation: Does a recommendation from the UK framework (e.g., on procurement) conflict with existing Mongolian governmental policy or law?

- Acceptability (Values): “Is the recommendation compatible with the culture and values in the setting where it is to be used?”

BIM Translation: Is the proposed collaborative workflow compatible with the established business culture of the Mongolian construction industry?

4. Comparative Analysis of International BIM Roadmaps

4.1. Query and Screening of International Policy and Guideline Practices for BIM Adoption

In Section 2 of this research, we have covered developing economies’ BIM adoption practices and assessed their guidelines. However, those studies were specifically focused on findings reported in the academic articles, presented in a scholarly manner regarding the BIM adoption challenges and the strategies employed by those nations. To carry out the ADAPTE process, we then further moved towards screening and analyzing international BIM policies and guidelines and strategic documents. This stage covered both developing and developed economies. In other words, in this section, we directly engage with global roadmaps and strategic frameworks.

The corpus of analysis contains a wide range of resources: legislative decrees of Spain and Argentina, technical roadmaps from the US and UK, long-term national visions of the Philippines, and detailed implementation guidelines of the jurisdictions of Vietnam, Hong Kong (Special Administrative Region of China), and Australia. Combining these unique strategies, this research provides a background upon which studies regarding BIM roadmap adaptation have the jurisdiction to borrow, alter, and transform digital strategies to suit their particular legal, economic, and cultural settings (see Table 4).

The narrative that is formed and emerges from the analysis of global policy and guideline frameworks is a story of convergence and divergence. Although the globe is becoming unified in technical standards, most significantly the ISO 19650 series [58], the implementation speed, economic incentivization, and legalization of digital property differ greatly in practice. There are extensive insights for retrieval for any entity aiming to conform a BIM roadmap; these environments are both aggressive and mandate-driven, like in Singapore and the UK, and the environments are capacity-building and education-focused, such as in Finland and Latvia.

Table 4.

Global policy and guidelines Analysis.

Table 4.

Global policy and guidelines Analysis.

| Guidelines and Policy Document Title | Jurisdiction | Document Type | Roadmap Phases and Key Temporal Milestones | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AASHTO BIM for Bridges and Structures Roadmap | The US | Roadmap | Year 3 (2018): Project work commencement. Focus on establishing national standards for bridge semantics/geometry. | [59] |

| B/555 Roadmap (Design, Construction, and Ops Data) | The UK | Roadmap/Standards Strategy | 2007–2014: Evolution from BS 1192:2007 to BS 1192-4 (2014). Defined maturity levels (0-3) and “Capital Delivery” phase guidance. | [60] |

| Royal Decree 11400/2019 (BIM Subsidies) | Spain | Legal Decree | 2018–2019: Fiscal cycles for training grants. Execution: 3 months from grant award for training activities. | [61] |

| Roadmap for BIM Implementation | Poland | Strategic Roadmap | 2020–2025: Implementation horizon. Defines “MacroBIM” (investment programming), delivery, and operation phases using a matrix (A1-E4). | [62] |

| Roadmap Standards Final Report | Netherlands | Roadmap/Standards Review | 2022: Snapshot of the “Digital Building File.” Life-cycle phases: initiative, design, realization, and maintenance/asset management. | [63] |

| Recommendations for Using BIM (KBOB) | Switzerland | Best Practice Guide | 2018: Publication. Defines public owner roles across the planning, construction, and operation phases. | [64] |

| Decision 347/QD-BXD (Detailed BIM Instructions) | Vietnam | Technical Regulation | 2021: Issued. Phases: preliminary design, basic design, technical design, construction drawing design. Specific LOD definitions. | [65] |

| Roadmap for Creating the Ideal Digital Ecosystem | Dubai, UAE | Strategic Roadmap | 2020: Mandate (A3.1-2020). Focus on GIS/BIM integration for the building permit ecosystem. | [66] |

| Philippines Construction Industry Roadmap | Philippines | Industry Roadmap | 2020–2030: Q2 2020: CIAP reform. 2023–2025: Service export focus. “Tatag at Tapat” (Stable and Faithful) vision. | [67] |

| Catalog of Measures for the Use of BIM | Germany | Strategic Study | 2013–2014: Research duration. Proposed phased rollout: pilot projects -> legal clarification -> standardization. | [68] |

| Construction Digitalization Roadmap | Hong Kong, China | Strategic Roadmap | 2021–2026: Targets 100% adoption for >HKD 300 M projects by 2026. 6 digital application areas (smart data, planning, etc.). | [69] |

| National Roadmap for BIM Development | Indonesia | Strategic Roadmap | Phase 1: Adoption/Pilots. Phase 2: Digitalization/Infrastructure. Phase 3: Collaboration/Lean. Phase 4: Integration/CIM. | [70] |

| Roadmap for Digital Transition | Ireland | Strategic Roadmap | 2018–2021: 4-year transition. Q1 2018: Leadership set-up. 2021 Target: 20% cost reduction, 20% faster delivery. | [71] |

| Vision for the Future and Roadmap for BIM | Japan | Strategic Roadmap | 2019: Initiation. Process 1–3: Workflow dev., geometry standardization, building confirmation via BIM. | [72] |

| BIM as an Element of Digitalization | Kazakhstan | Strategic Report | 2017: Standards intro. 2018–2019: State Bank of Info models. 2021: Digitization of regulations. | [73] |

| BIM Guide | South Korea | Implementation Guide | 2010: Early adoption framework. Focus on virtual design, software selection, and data creation standards. | [74] |

| BIM Roadmap (Ceļa Karte) | Latvia | Strategic Roadmap | 2019: Launch. 2025: Public procurement mandate. 2022/2023: Educational curriculum integration. | [75] |

| JKR Strategic Plan 2021–2025 | Malaysia | Agency Plan | 2021–2025: 5-year cycle. Focus on total asset management (PAM) and technical excellence (CREATE). | [76] |

| Singapore BIM Roadmap | Singapore | Strategic Roadmap | 2010–2015: 2013: Arch e-submission (>20 k m2). 2014: Eng e-submission. 2015: All projects >5 k m2. | [77] |

| Strategic Plan for Digital Transformation | Argentina | Strategic Plan | 2019–2023: 4-year plan. Focus on transparency, efficiency (“Obras Claras”), and innovation. | [78] |

| Australian BIM Strategic Framework | Australia | Strategic Policy | 2019: National principles. Objectives: consistency, efficiency, open data standards across states/territories. | [79] |

| Digital Engineering Framework v4.0 | Australia (NSW) | Technical Framework | 2018–2022: Iterative release (v1.0 to v4.0). Life-cycle focus from context to procurement to education. | [80] |

| Victorian Digital Asset Strategy (VDAS) | Australia (VIC) | Strategic Guidance | 2019: Release. Defines 7 life-cycle stages: brief, concept, definition, design, build, handover, and operations. | [81] |

| BIM BR Strategy | Brazil | National Strategy | 2018: Launch. Phase 1 (2021): Arch/Eng Pilots. Phase 2 (2024): 4D/5D. Phase 3 (2028): Full life-cycle O&M. | [82] |

| National BIM Strategy | Costa Rica | National Strategy | 2020: Launch. 2019: Diagnostic. Future: Standardization and pilots modeled on international benchmarks. | [83] |

| BIM Implementation Strategy | Czech Republic | Strategic Concept | 2017: Approval. 2018–2020: Preparation/Pilots. 2022: Obligatory BIM in public contracts. | [84] |

| Handbook for the Introduction of BIM | EU | Strategic Handbook | 2017: Pan-European framework. Sets context for national strategies. Targets 10–20% sector savings by 2025. | [85] |

| Standardization of Information (RASTI) | Finland | National Strategy | 2018–2030: 2023: Commitment. 2025: Mandatory use. 2030: Vision of machine-readability. | [86] |

| Guide of Recommendations for Clients | France | Implementation Guide | 2016: PTNB launch. Focus on the “BIM 2022” horizon and engaging SMEs in the digital transition. | [87] |

4.2. Benchmark Case Selection (South Korea, Singapore, the UK, and Germany)

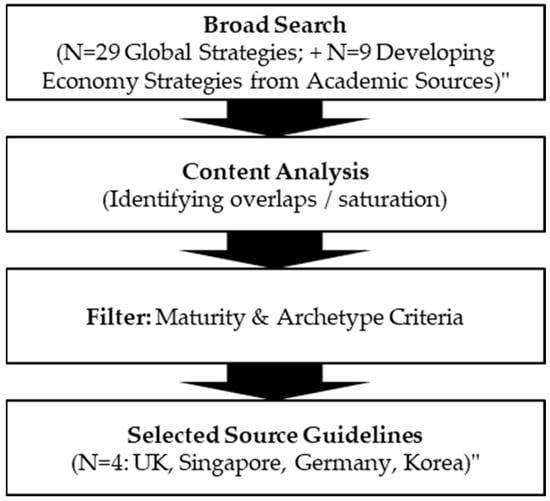

The first phase of the ADAPTE process is the search and screening phase, which is important to ensure the validity of the adapted roadmap. The initial data collection identified 29 global BIM strategic frameworks and 9 developing economy frameworks. The 9 cases are reported in the academic article format, which addresses BIM adoption frameworks, as seen in Section 2. Nevertheless, an indiscriminate collection of the 38 sources could result in redundancy and a loss of strategic focus. As a result, a methodical process for eliminating the sources was applied to the selection of the most appropriate source guidelines that can be adapted to the Mongolian context (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The benchmark case selection funnel.

The initial content analysis of the N = 38 frameworks demonstrated a great level of convergence. Most of the employed strategies had overlapping methodologies, namely, (1) a staged maturity strategy (levels or tiers); (2) the implementation being split into the streams of people, process, and technology; and (3) being based on public procurement mandates. This knowledge saturation meant that the analysis of all the 38 documents would not produce increasing returns and would only diminish. As a strategy to maintain methodological soundness, the research field changed to the quality of the strategic archetype instead of the number of sources.

The selection criteria were narrowed to find high-maturity archetypes in order to support the primary principle of the ADAPTE process, which is the transfer of the evidence from best practices from a mature setting to a target setting. The four benchmark countries were then chosen. They were selected not only because of their developed status, but also because they represent various successful archetypical models that offer the most valuable knowledge base to adopt:

- The UK (The Standardization Archetype): It was chosen as the predecessor of the ISO 19650 standard and the most effective implementation strategy based on top-down governmental requirements. It provides the ultimate plan for policy standardization.

- Singapore (The Integration Archetype): It was chosen because its roadmap integrates with electronic submission systems (CORENET). It offers a model of the digital ecosystem that is required to achieve long-term efficiency by the government.

- South Korea (The Developmental Archetype): This country was chosen for being a successful example of a region that managed to switch between being a fast follower and a global leader. Its roadmap provides certain understandings of the Asian regulatory environment and the government-based infrastructure digitalization associated with Mongolia.

- Germany (The Industry-Led Archetype): The country was chosen due to its high emphasis on technical accuracy and industry-oriented standards (VDI), and it provides a roadmap model that fulfills the various needs of stakeholders regarding technical aspects.

Despite the fact that the four countries are representatives of developed economies who have many more resources than Mongolia, they were chosen specifically because of the maturity of their frameworks. The ADAPTE process is meant to fill this gap between the rich bodies of knowledge and the resource-restricted Mongolian context described in Section 2.3. This does not mean that we have immediately abandoned the previous analysis results of other 34 cases. Specifically, the developing economies case analysis was still utilized as supportive references when building the strategic framework for Mongolian BIM adoption, as discussed in the extensive literature review which revealed that many aspects are similar among developing nations. With tested and rich resources, the four benchmarks are chosen to act as a backbone, instead of averaging all 38 sources. This is to guarantee that the beginning of the adaptation process is of top quality, systematic, and organized, thus maximizing the chances of the roadmap becoming successful once the filter of adaptation has been used.

4.3. Key Features of the Four Benchmark BIM Roadmaps

The BIM roadmaps of the UK, Germany, Singapore, and South Korea each exhibit unique approaches tailored to their specific contexts and priorities. While there are common elements, such as government support and the development of standards, differences in focus and strategies exist. The following are the key features of these four countries:

4.3.1. The UK

- Mandate-Driven Approach: The UK is known for its strong government-led approach to BIM adoption. It implemented a BIM mandate for public sector projects, starting with BIM Level 2, and later introduced Digital Built Britain, aiming for the full digitalization of the construction industry.

- Clear BIM Standards: The UK has developed comprehensive BIM standards and guidelines, such as PAS 1192, which provide a structured framework for BIM implementation. These standards emphasize data exchange, collaboration, and common naming conventions.

- Public–Private Collaboration: The UK emphasizes collaboration between the public and private sectors. The BIM task group, consisting of industry experts, played a key role in developing and promoting BIM adoption.

- Education and Skills Development: The UK invests significantly in BIM education and training programs. It supports the development of a skilled workforce through initiatives like BIM apprenticeships and certification programs.

4.3.2. Germany

- Regulation-Driven Approach: Germany focuses on introducing regulations and digitalization in the construction sector to improve efficiency. It introduced DIN SPEC 91400 as a guideline for BIM implementation and emphasizes digital plan review and approval.

- Standardization Efforts: Germany’s approach includes a focus on standardization and guidelines, aligning with DIN standards. DIN SPEC 91391 and DIN SPEC 91400 provide the framework for BIM processes and data exchange.

- Public and Private Collaboration: Collaboration between government and industry is a common theme. Organizations like the German Institute for Standardization (DIN) work with industry stakeholders to develop BIM standards.

- Education and Training: Germany recognizes the importance of BIM education and offers various training programs to build a skilled workforce.

4.3.3. Singapore

- Government-Led and Mandate-Driven: Singapore has a strong government-led initiative with mandatory BIM requirements for public projects. The BCA (Building and Construction Authority) introduced these mandates to drive BIM adoption.

- Smart Built Environment: Singapore places BIM within the broader context of a smart built environment. BIM is seen as integral to enhancing urban living, sustainability, and infrastructure quality.

- Comprehensive BIM Guides: Singapore provides comprehensive BIM guides and educational programs to support adoption. It emphasizes standards like the Singapore BIM Guide and collaborates with industry players.

- International Engagement: Singapore actively participates in international BIM events and collaborations, sharing its experiences and learning from others.

4.3.4. South Korea

- Government-Driven Initiatives: South Korea relies on government-driven initiatives and regulations to promote BIM adoption. The Smart Construction Promotion Act and digital plan review are examples of regulatory efforts.

- BIM Training and Research: South Korea focuses on BIM training and education for professionals. It encourages research and development in BIM-related projects and technologies.

- Industry Collaboration: Collaboration among the government, industry, and academia is a common theme in South Korea. Task forces and associations promote BIM adoption and knowledge sharing.

- Digital Transformation: South Korea’s approach emphasizes the digital transformation of the construction sector, with BIM as a central component.

4.4. Common Approaches

While the specific details of BIM roadmaps in the UK, Germany, Singapore, and South Korea may vary, there are some common approaches and principles that are often shared among countries aiming to promote BIM adoption in the construction industry. The following are common approaches that these countries tend to embrace.

Government Leadership and Mandates: Many countries, including the UK, Singapore, and South Korea, rely on strong government leadership and mandates to drive BIM adoption. Government agencies play a pivotal role in setting standards, requirements, and guidelines for BIM use in public projects. Government mandates often include requirements for BIM Level 2 or higher, emphasizing the use of 3D models, data exchange standards, and collaboration among project stakeholders.

Clear BIM Standards and Guidelines: Establishing comprehensive BIM standards and guidelines is crucial. These documents provide a structured framework for BIM implementation, ensuring consistency and interoperability. Standards cover various aspects of BIM, including data exchange, naming conventions, model development, and information sharing protocols.

Education and Training: Promoting education and training on BIM is a common approach. Countries typically invest in BIM-related education programs, courses, and certifications to build a skilled workforce. Training initiatives target professionals across the construction industry, including architects, engineers, contractors, and project managers.

Digital Plan Review and Approval: The digitization of plan review and approval processes is a common goal. This involves transitioning from paper-based plans to digital BIM models for regulatory approvals. Digital plan review increases efficiency, reduces errors, and enhances collaboration among regulators and project teams.

Collaboration Platforms and Data Exchange: Encouraging the use of collaboration platforms and standardized data exchange methods is a key approach. These platforms enable the real-time sharing of BIM data among project stakeholders. Collaboration platforms facilitate communication, coordination, and decision-making, leading to more efficient project delivery.

Industry Collaboration: Collaboration between the government, industry associations, academia, and professional bodies is essential. Working together, these stakeholders help define BIM standards, share best practices, and promote BIM adoption. Industry associations often play a central role in fostering collaboration and knowledge exchange.

International Engagement: Many countries actively engage in international BIM events, forums, and collaborations. They participate in global BIM discussions and share experiences with other nations. International engagement helps countries stay updated on BIM developments and align their practices with global standards.

Monitoring and Evaluation: Implementing key performance indicators (KPIs) and conducting regular assessments are common practices. These evaluations measure the progress of BIM adoption and identify areas for improvement. Periodic assessments help ensure that BIM practices align with the country’s goals and objectives.

Government Funding and Support: Providing financial incentives, grants, or subsidies to construction firms for BIM adoption is another approach. Government support encourages industries to invest in BIM technologies and training. Funding initiatives may also promote BIM-related research and development.

Digital Transformation and Smart Built Environments: Finally, all countries shown in Section 4.3 incorporated BIM into broader digital transformation and smart built environment strategies. BIM is seen as a cornerstone of improving urban living and infrastructure.

4.5. Target Maturity Stages

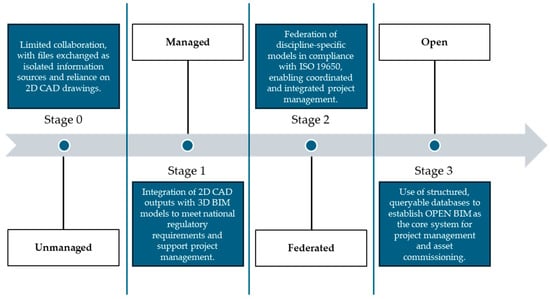

The maturity models used in different countries vary. To establish a common understanding for the maturity model based on international consensus, the roadmap for Mongolia will refer to the ISO 19650 maturity model to define the target level of BIM implementation [58]. ISO 19650 is derived from two British standards, BS 1192 and PAS 1192-1, which focus on providing an effective framework for collaborative efforts among diverse participants in construction processes, ultimately improving all stages of construction.

The maturity model for managing digital information, as depicted in Figure 4, is described in ISO19650-1 [88]. However, the detailed definition for each stage is not provided in ISO19650-1. Therefore, we will refer to the definitions outlined in the UK’s BIM Maturity Model. In the UK’s BIM Maturity Model, the stages of maturity are categorized as levels, but in accordance with ISO19650-1, we will use the term “Stage.” Referring to the UK’s BIM Maturity Model, shown in Figure 4 of this manuscript, each Stage can be defined as follows:

Figure 4.

A framework for information management maturity based on the ISO19650 [58,88,89].

- Stage 0 (Unmanaged): The term ‘Unmanaged’ implies the absence of rules in managing project information shared among project participants. At this stage, national or international construction information management standards are not utilized, and project information is not managed according to any project standards. Typically, 2D drawings and traditional communication and documentation methods are employed, lacking the benefits of digital collaboration and information sharing technologies.

- Stage 1 (Managed): The term ‘Managed’ signifies a level of maturity in which there are established rules and processes for managing project information. At this stage, national or international standards for construction information management are implemented to ensure consistency. Project information is managed according to project-specific standards and a CDE (common data environment) for efficient collaboration. This includes the use of structured data formats, such as CAD, and electronic means of communication and documentation. The biggest difference between Stage 1 and Stage 2 is the utilization of integrated applications for information with federated information models. Therefore, collaboration primarily revolves around managing information within individual disciplines or organizations in Stage 1.

- Stage 2 (Federated): Stage 2 refers to a higher level of BIM maturity, where information models from different disciplines are combined, creating a federated information model that integrates data from various sources. This stage emphasizes the integration and coordination of information across disciplines to enable effective collaboration and eliminate clashes between disciplines. In Stage 2, there is typically an increased level of interoperability between different software applications and a focus on information exchange standards to facilitate efficient coordination. The federated information model allows for a more holistic view of the project, enhancing collaboration and coordination among project stakeholders. Using integrated applications and federated information models enables real-time collaboration, clash detection, and improved communication among all project participants. This stage moves beyond managing information within disciplines and emphasizes the integration of data and models to achieve better project outcomes.

- Stage 3 (Open): Stage 3 represents a future vision for BIM that has not yet been fully defined. However, the UK Government’s Strategic Plan outlines the vision and key measures for this stage. The focus is on achieving a more open and collaborative environment for data sharing and project delivery.

5. Proposed Strategic Framework for BIM Implementation in Mongolia

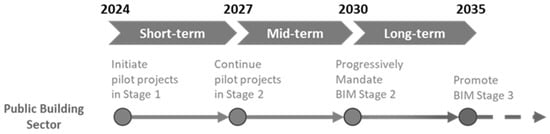

A phased timeline for implementing various BIM stages in the construction industry is visually represented in Figure 5. This approach mirrors the strategy commonly used by developed countries when legislating BIM adoption. A key aspect of this process is the alignment of implementation stages with the evolution of the national legal system, thereby ensuring a methodical and organized transition.

Figure 5.

Maturity stage-based targets for the strategic framework.

The first stage of implementation customarily begins with pilot projects designed to assess the real-world viability of BIM. This exploratory phase is crucial for pinpointing potential challenges and for formulating effective guidelines and best practices. Once the pilot stage is complete, a foundational framework is created to guide the adoption process, detailing key aspects like data standardization, interoperability, and collaborative workflows.

5.1. Strategic Framework Goals by Phase and Action

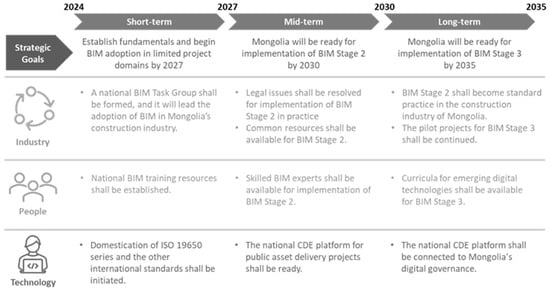

Figure 6 presents the strategic goals associated with each maturity stage outlined in the preceding sections, followed by a concise explanation of each objective.

Figure 6.

Strategic goals by phase and action framework.

Short-term goal (by 2027): To create the fundamental framework for BIM and commence the use of 3D coordination in a limited scope of projects.

- The short-term goal is to introduce BIM into the construction sector, with an initial emphasis on applying it to three-dimensional model-driven coordination. This stage is intended to act as a practical starting platform through which the industry can observe its advantages. In doing so, BIM can be progressively incorporated into established practices and processes.

- To facilitate the uptake of BIM during this stage, it is crucial to establish the necessary groundwork, which includes the development of standardized guidelines and a supportive legal framework. These guidelines will provide a framework for implementing BIM in the most effective and efficient way possible, while the legal documents will ensure compliance with regulations and provide the necessary legal backing for BIM implementation.

- Alongside the preparation of guidelines and regulatory documents, improvements to the legal framework are required. Such reforms should help guarantee that the construction sector has access to professionals trained in BIM. A strong legal framework also plays a central role in enforcing technical standards. As a result, the effective promotion of BIM depends on the presence of a competent and well-qualified workforce.

Mid-term goal (by 2030): The nation will be positioned to advance to BIM Stage 2 maturity.

- The primary mid-term objective is to align Mongolia’s construction sector with international standards by reaching Stage 2 BIM maturity. The stage is marked by an expansion of BIM capabilities beyond simple three-dimensional coordination, creating the basis for more sophisticated implementations.

- Reaching this target depends on construction-related public authorities being adequately prepared to use BIM in advance of regulatory enforcement. Such a proactive strategy will ensure the industry is adequately equipped to adopt the advanced BIM methodologies stipulated by international standards.

- Achieving Stage 2 maturity requires the adoption of ISO 19650 standard systems across all organizations in the construction industry of Mongolia. These standards provide a framework for managing information and collaboration throughout the construction process. By adopting these standards, Mongolia can align its practices with global best practices, allowing for seamless integration and collaboration with international partners.

- The success of this stage relies heavily on strong cooperation with the appropriate government departments. Such collaboration helps ensure that public policies and initiatives are consistent with and supportive of BIM practices. It also plays an important role in making procedures more efficient. Furthermore, this partnership helps to eliminate obstacles that could hinder the effective use of BIM in the construction sector.

- The phase is marked by the large-scale integration of digital systems, such as collaborative data platforms, digital communication networks, and the essential technological resources. These technological instruments are designed to support and streamline information exchange, coordination, and collaborative processes among the diverse stakeholders in the construction sector.

- By achieving Stage 2 maturity and implementing ISO 19650 standards, the construction industry in Mongolia can enhance its international competitiveness, improve project delivery efficiency, and foster collaborative working relationships with international partners.

Long-term goal (by 2035): Readiness to implement BIM Stage 3.

- The overarching future goal involves fully modernizing Mongolia’s building sector through digitalization, marking a major step forward in incorporating advanced technologies. The concluding stage corresponds to approaches adopted in developed countries, where emphasis is placed on broadening the use of information-rich, model-driven construction processes to reach the upper tier of BIM maturity. The central elements of this pathway include digital twin systems, intelligent construction methods, the combination of artificial intelligence (AI) with big data analytics, and applications of augmented reality (AR) and mixed reality (MR). Collectively, these cutting-edge tools represent the leading edge of innovation in the sector and hold substantial promise for improving efficiency, sustainability, and collaboration in projects.

- Once BIM is firmly embedded in the construction sector, attention shifts toward using digital models to improve efficiency and safety throughout the lifespan of a project. Access to this information enables stakeholders to make better decisions and refine day-to-day processes. It also supports a more effective allocation of resources from the design stage through construction and into facility management.

- During this phase, research and development activities will be of critical importance as stakeholders aim to integrate new technologies. By examining cutting-edge technologies, carrying out pilot initiatives, and analyzing their possible outcomes, researchers will play a leading role in shaping the future of Mongolia’s construction field.

- As new digital technologies are adopted and tested during this phase, guidelines and standards will need to be expanded to accommodate these advancements and ensure compliance with the legal system. It is essential to continuously update regulatory frameworks, industry standards, and best practices to support the integration of innovative technologies and maintain a competitive edge in the global construction market.

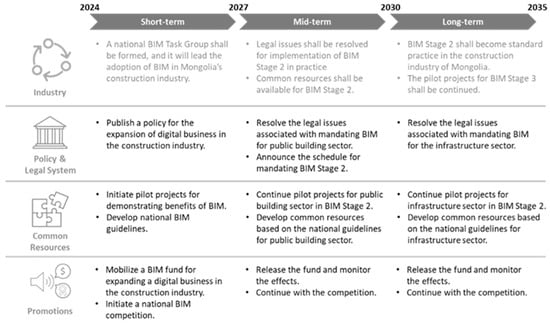

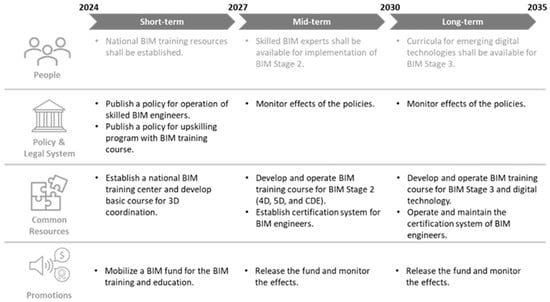

5.2. Outline of Action Items for Each Aspect of the Roadmap Framework

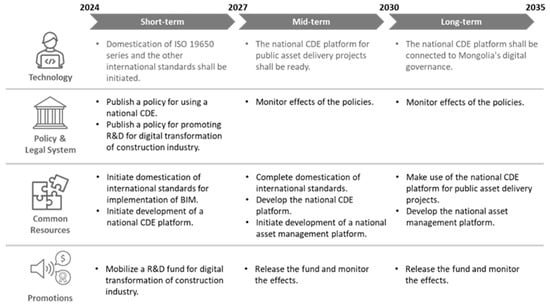

This section presents outlines of action items that will contribute to the implementation of the strategic goals shown in Section 5.1. These action items are categorized into three areas: policy and legal systems, common resources, and promotion. Each category encompasses specific tasks and initiatives that are essential for achieving the strategic goals of BIM implementation in Mongolia. Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9 illustrate the outlines of action items to be executed to achieve the strategic goals.

Figure 7.

Outline of action items for the industry area.

Figure 8.

Outline of action items for the people area.

Figure 9.

Outline of action items for the technology area.

6. Detailed Action Plan Items for Strategic BIM Implementation

In light of the government’s ability to influence and manage the dissemination of technology through various policy tools like subsidies, mobilization, and innovation directives [90], public authorities are naturally positioned to lead the implementation of BIM adoption strategies. Consequently, the developed strategic framework highlights the pivotal role of the government in advancing the adoption and widespread use of BIM. This was depicted in the action plan as leadership and ownership of the action.

Tables 5, 7 and 9 present the action items and major tasks necessary to achieve the strategic goals outlined in Section 5.1. They provide an overview of the specific actions required to progress towards the defined objectives.

Tables 6, 8 and 10 showcase the timeline for accomplishing the action items. It highlights the targeted timeframes for completion, enabling stakeholders to track progress and ensure timely execution of the identified tasks.

Beyond the comprehensive operational list of detailed action plans presented in Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8, Table 9 and Table 10, the framework prioritizes specific mechanisms designed to mitigate implementation risk and ensure institutional depth. Among the diverse tasks outlined, ‘Action I5: Pilot Projects’ is critically positioned in the short-term phase (2024–2027) to serve as the primary risk assessment mechanism. This design allows the government to evaluate economic feasibility and the cost–benefit ratio on a small scale before enforcing the broader mandates scheduled for 2030.

Table 5.

Action items and major tasks for the industry area.

Table 6.

Schedule of the action plan for the industry area by phase.

Table 7.

Action items and major tasks for the people area.

Table 8.

Schedule of the action plan for the people area by phase.

Table 9.

Action items and major tasks for the technology area.

Table 10.

Schedule of the action plan for the technology area by phase.

Simultaneously, the framework addresses the policy vacuum aspects highlighted in Section 2 by targeting the specific legal bottlenecks identified in Action I2 (remove potential legal issues). As detailed in the timeline, this action is split into an identification phase (by 2026) and a resolution phase (by 2029). This distinction is crucial because Action I2 goes beyond simple technology adoption; it requires a fundamental restructuring of the construction sector’s legislative environment to officially recognize digital models as legal documents, thereby replacing the current requirement for static 2D paper archiving.

7. Discussion: Strategic Implications for Sustainable Development

The strategic framework for BIM adoption in Mongolia proposed in this work represents a paradigm shift in the Mongolian construction industry as it currently stands, transitioning from an uncoordinated, fragmented form of digitalization to a national effort. The implications of this shift are not only restricted to technical efficiency but are directly related to the realization of sustainable development goals.

7.1. Policy, Legal Framework, and Sustainability

The analytical results support that the existence of the policy vacuum [25,27,29,30,31,38,45,46,47,48,49,50,51], especially the absence of a strategic, systematic BIM adoption framework, is the main threat to sustainable construction practices in developing economies. This vacuum left the construction industry of Mongolia operating under a legacy legal framework that is structurally incompatible with digital transformation. Previous assessments of the local context identified that the current governance structure, comprising 12 core legislations and 27 types of construction permits, is strictly framed around 2D-CAD deliverables, legally rendering BIM data invisible to state regulators [28].

Consequently, the adoption of BIM impacts national governance beyond technological implementation, demanding comprehensive legislative reform in the construction sector of Mongolia. State-sponsored sustainability capacities emerge when existing legal gaps are addressed through a structured strategic framework. Having the strategic framework for BIM adoption is one of the features that promotes the implementation of tools that are important in energy simulation, waste reduction, and LCA [4,11,16,18,39]. Without this kind of mandate, sustainability remains a niche effort rather than a routine business operation. The Action item I3 “Progressive Mandating Schedule” serves as a coercive governance tool, as it forces the systematic upgrade of these permit mechanisms to encompass all aspects of the environment, from the beginning to the design and construction phases.

7.2. Socio-Economic and Technical Transformation

The tri-aspect design (industry, people, and technology) of the framework acknowledges the adoption of BIM as a socio-economic and technical challenge rather than a purely technological one. Of particular concern is the people pillar. The national BIM training center (BTC) in the short-term phase (Phase 1) should be established and then people should be hired to mitigate the skills gap plaguing most developing countries by standardizing competencies early in the transition. Mongolia has the chance to avoid the pit of vendor-led training by concentrating on training and aligning it to national standards (ISO19650), which is concentrating on programs that are pre-defined and process management as opposed to software capabilities. This gives the working population a mandate to use BIM not only in visualization, but also in the meaningful analysis of building performance, thus improving the social and economic aspects of sustainability.

As this workforce capacity matures into the mid-to-long term, shifting from manual to model-based coordination is projected to capture the 10–20% cost savings typically observed in mature BIM markets [85]. Applied to Mongolia’s 2024 construction output of MNT 9.16 trillion (approximately USD 2.7 billion) [56], a conservative 10% efficiency gain would translate into approximately MNT 916 billion (approximately USD 270 million) in potential annual capital preservation. With the strategic framework, the wider adoption of BIM in Mongolia could capture this projected value of savings that could mitigate the construction sector’s financial constraints and offset the initial costs of digital adoption, serving as a critical long-term economic target for the industry.

7.3. Towards a Digital Nation and Transformation

The recommendation of establishing a National Common Data Environment (CDE) Platform (Action T4) and an asset management platform (Action T5) is a strategic step toward digital sovereignty. Currently, critical construction and asset data are fragmented across proprietary silos and servers in lots of local jurisdictions, limiting their long-term utility. A national platform is necessary to maintain the rich nature of the data that is created during construction and use them in the long-term management of constructed assets. The paradigm of the smart built environment cannot do without this ability, where data is used to make decisions on how to use energy as well as maintain buildings and distribute their resources in relation to the life-cycle of the building.

Moreover, Mongolia has a comprehensive long-term development policy called Vision 2050 that aims to transform the nation’s knowledge-based economy [91]. The Vision 2050 policy sets out nine fundamental goals and fifty objectives for national development. From those fundamental goals, smart governance and green development are mandated as the pillars for modernizing the nation’s industrial and regulatory structures. Our proposed strategic framework will align the construction sector of Mongolia with the nation’s long-term development objectives in this regard and have supportive effect on it.

7.4. Construction Materials and Supply Chain Sustainability

In the study conducted by Enkhbold and Altanzagas, the empirical evidence of the construction material supplies in Mongolia shows that it is a sector with huge pressures [92]. The “Shortage of materials” can be seen as the most notable critical factor influencing the industry and it has the highest relative importance index (RII) of 0.902, even higher than economic instability [92]. The issue of the shortage of materials is also compounded by the shortage of logistics, which is understandable given that Mongolia is a country with a significant reliance on imports. In this respect, the BIM adoption strategic framework will, at the mature stages, enable BIM to move beyond its role in design coordination and become an essential support for addressing sustainability challenges related to construction materials. The aforementioned vulnerabilities are directly dealt with in the proposed framework pillar of technology (namely, the push towards 4D “scheduling” and 5D “cost”; BIM maturity by 2030).

Another significant finding from the study [92] is that the RII of “Incorrect planning” (0.871) is very high and directly linked to the waste of materials while facing the material shortage crisis environment. The classical 2D estimation process is likely to induce errors, which results in slow last-minute orders of procurements, which the weak logistics system cannot deliver. Projects can predict the material requirements with great accuracy in the weeks or months prior to the project’s start by using BIM-based quantity take-offs and 4D logistical sequencing. This is essential in terms of just-in-time delivery in a limited environment.

Furthermore, by replacing manual estimation with BIM-based quantity take-offs and design validation, the sector can target a reduction in error-induced construction waste comparable to the 4.3–15.2% prevention rate documented in international case studies [93]. Given that the total freight carried by all transport types in Mongolia reached 131.1 million tons in 2024 [56], minimizing material wastage through digital accuracy implies not only lower project costs but a measurable decrease in the embodied carbon footprint of the national logistics chain.

7.5. Infrastructure Resilience and the Climate Imperative