Abstract

Green Public Procurement (GPP) serves as a crucial tool on the demand side for fostering an economic shift towards sustainability. This study empirically examines the inhibitory effect of GPP on corporate ESG greenwashing and its underlying mechanisms, based on ESG rating data of A-share listed companies in China and GPP contract announcements between 2015 and 2020. The findings indicate that GPP significantly mitigates corporate ESG greenwashing, and this conclusion is robust across various sensitivity tests. Mechanism analysis shows that GPP operates through three primary channels: alleviating financing constraints, promoting green innovation, and enhancing corporate green reputation. Further heterogeneity analysis demonstrates that the ESG greenwashing mitigation effect of GPP is more pronounced in firms operating in highly competitive industries, with high analyst attention, and at the mature stage. This study highlights the potential role of GPP in guiding enterprises toward genuine sustainable practices. Additionally, it provides valuable policy recommendations for developing countries aiming to strengthen environmental governance and refine green procurement frameworks.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the world has been grappling with a host of environmental emergencies, including the acceleration of climate change, a dramatic loss of biodiversity, and escalating pollution. Against this backdrop, China announced “dual-carbon” goals in September 2020 and introduced the “Guidelines for Sustainability Reporting by Listed Companies” in May 2024, signaling an increasingly stringent regulatory environment for ESG. However, as disclosure requirements tighten, the disconnect between corporate rhetoric and actual practices has become increasingly evident. Some companies continue to adopt deceptive means known as ESG greenwashing [1]. ESG greenwashing refers to the selective and exaggerated disclosure of ESG information by enterprises to build a favorable green image [2,3]. Such behavior not only weakens consumers’ trust in the authenticity of environmentally friendly products but also fundamentally undermines enterprises’ capacity for sustainable development [4,5,6,7].

The existing literature primarily explores the governance effects of environmental protection tax [8], green finance development [9,10], and media or public oversight [11,12] on corporate ESG greenwashing from the perspectives of regulatory pressure and resource constraints. These studies emphasize the role of compliance costs and external supervision but often operate under an implicit assumption: corporate green behavior is largely driven by external pressure and passive adaptation. However, such research overlooks policy tools that reshape firms’ intrinsic incentives by creating market demand. As a significant demand-side policy, GPP leverages price mechanisms to prioritize the procurement of goods and services that meet ecological standards [13], thereby incentivizing firms to engage in substantive green investments and reducing their motivation for ESG greenwashing. Data indicates that in 2023, energy-efficient and environmentally friendly products accounted for 83.9% and 84.9% of total government procurement in their respective categories in China, reflecting the substantial implementation of this policy. Although studies have shown that GPP promotes corporate green innovation [14] and guides sustainable consumption [15], the pathways and theoretical mechanisms through which it governs ESG greenwashing remain underexplored. This gap limits both academic understanding and policymakers’ ability to leverage market-based incentive policies to enhance the quality of ESG disclosures. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the following questions: Can GPP serve as an effective market demand signal to curb corporate ESG greenwashing? What are the underlying mechanisms? Under what conditions is this effect more pronounced? These questions urgently require empirical evidence to be tested.

To address these issues, our research examines A-share listed companies in China from 2015 to 2020. We employ text analysis to identify green procurement programs in the China Government Procurement Network and construct ESG greenwashing evaluation indices using third-party ESG rating data. Our findings show that GPP plays a notable inhibit role in curbing corporate ESG greenwashing. This conclusion holds up even after multiple internal validity tests. Mechanism analysis further indicates that GPP reduces ESG greenwashing by alleviating financing constraints, promoting corporate green innovation and enhancing corporate green reputation. Additionally, our heterogeneity analysis highlights that this inhibitory effect of GPP is more intense in fiercely competitive industries, with high analyst attention, and in mature firms.

Compared with the existing literature, this study makes the following marginal contributions:

Firstly, from a theoretical perspective, it constructs an analytical framework to examine how GPP influences corporate environmental strategy. GPP raises the cost of non-green production through the market mechanism and incentivizes enterprises to take the initiative to adopt environmental protection measures, which provides a reference value for government policy intervention to solve the problem of insufficient market incentives.

Secondly, in terms of the research perspective, this study enriches the literature on the environmental effects of GPP. Some studies have discussed the impact of environmental regulation [16,17] and environmental and energy policy uncertainty [18,19] on corporate greenwashing. However, these studies focus on broader regulatory or environmental policy rather than GPP specifically. By focusing on strategic information disclosure, this study empirically examines how GPP shapes firm-level environmental behavior, offering important implications for optimizing GPP policies and improving environmental governance systems.

Thirdly, regarding mechanism pathways, it reveals multiple channels through which GPP mitigates corporate ESG greenwashing. Specifically, this study demonstrates that GPP influences firms through financing constraints, green innovation and green reputation. These findings not only deepen our understanding of the policy transmission process but also provide actionable pathways for government and firms to jointly advance green transformation.

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Green Public Procurement and ESG Greenwashing

With the deepening of global commitment to sustainable development, GPP has become an important green fiscal policy tool for environmental governance [20] and is gradually emerging as the focus of public procurement across various countries. According to signaling theory, in markets with information asymmetry, the party possessing informational advantages conveys its developmental status through specific signals [21]. As ESG performance is difficult to observe directly, ESG disclosure serves as a key signal through which companies communicate their environmental commitments to stakeholders. However, due to the lack of effective verification mechanisms, some firms may engage in selective disclosure of ESG information to project a green image that deviates from reality.

From this theoretical perspective, through the market-pulling effect on the demand side, GPP not only stimulates environmental innovation [14], but also effectively guides industries toward green and low-carbon transformation. Studies show that GPP can generate stable market demand for green products [22], which in turn motivates enterprises to engage in production activities [23]. Additionally, because of their strong financial capacity and stable procurement scale, government customers enable GPP to significantly improve firms’ cash flow expectations and provide the market with a clear signal of green development [20,22,23,24]. Since GPP standards are set by the government, independent of commercial interests and subject to strict third-party certification, this enhances the verifiability of corporate environmental signals, thereby encouraging firms to make substantive investments in environmental protection to enhance their authentic ESG performance. Therefore, the filtering function of GPP becomes a continuous driver of corporate green transformation, significantly reducing the likelihood of manipulating ESG data, thereby suppressing corporate ESG greenwashing. Based on the above analysis, we put forward the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1.

Green public procurement can effectively govern corporate ESG greenwashing.

2.2. Green Public Procurement, Financing Constraints and ESG Greenwashing

The role of GPP in alleviating financing constraints is mainly reflected in the following two aspects: On one hand, government customers possess strong purchasing power and low default risk, and the cooperation cycle is generally longer, which provides firms with a source of stable and sustainable cash flow support [24,25]. On the other hand, obtaining GPP orders signals that the enterprise has gained governmental credit endorsement. This endorsement acts as a policy signal to financial institutions, guiding the allocation of financial resources and making them more willing to provide credit support. Enterprises can use such future stable cash flows as collateral to enhance financing capacity and effectively alleviate financing difficulties [26]. Existing research indicates that financial constraints are a key incentive for companies to adopt ESG greenwashing strategies [27,28,29], and ESG greenwashing behavior tends to reduce the financial performance of enterprises [30]. Alleviating financing constraints can effectively address the issue of insufficient funds for production and operation, thereby reducing firms’ motivation to implement ESG greenwashing. Therefore, stable and sufficient financial support reduces the possibility of enterprises of seeking short-term benefits through ESG greenwashing. Consequently, the following hypothesis is proposed in this paper:

Hypothesis 2.

Green public procurement governs corporate ESG greenwashing by alleviating financing constraints.

2.3. Green Public Procurement, Green Innovation and ESG Greenwashing

The influence of GPP on fostering corporate green innovation is most striking in two ways: On one hand, consistent governmental acquisition directives mitigate the ambiguity surrounding the anticipated payoffs from companies’ green innovation endeavors [14], effectively promoting firms’ enthusiasm for green innovation. On the other hand, GPP offers direct policy guidance for corporate research and development (R&D) through the establishment of clear green standards. Government supervision of enterprise suppliers is more stringent than that of enterprise customers [31], requiring suppliers to intensify their efforts in developing environmentally friendly products and technologies to meet strict regulatory standards. This motivates firms to enhance green innovation in order to fulfill their environmental commitments. Furthermore, green innovation effectively reduces the attractiveness of firms’ greenwashing behavior by highlighting competitive advantages that are difficult to replicate [32]. In practice, the government’s green procurement policy prompts enterprises to pay more attention to long-term technological research and the optimization of green production processes, encouraging substantial green innovation and thus effectively governing ESG greenwashing. Based on this, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3.

Green public procurement governs corporate ESG greenwashing by fostering green innovation.

2.4. Green Public Procurement, Green Reputation and ESG Greenwashing

Reputation, as a critical intangible asset, not only enhances customer attractiveness, but also empowers enterprises’ pricing power so as to realize sustainable development [33]. According to signaling theory, government procurement orders act as a credible policy endorsement, sending a powerful signal to the market regarding the excellence of an enterprise’s green products and technologies. Backed by the authority and credibility of the government, this endorsement is directly convertible into market reputation, an outcome that possesses far greater influence than commercial advertising, which can not only significantly strengthen their competitive advantages [34], but also enhance their green reputation. A high level of green reputation indicates that enterprises have professional environmental management capabilities [35]. Studies have shown that the improvement of corporate green reputation will bring about a significant increase in the overall reputation score [36]. High-reputation enterprises are more likely to reduce greenwashing behaviors in order to maintain their green image. However, low-reputation companies are more inclined to engage in symbolic disclosure to quickly meet investor expectations, compensating for their lack of reputation capital [37]. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 4.

Green public procurement governs corporate ESG greenwashing by enhancing green reputation.

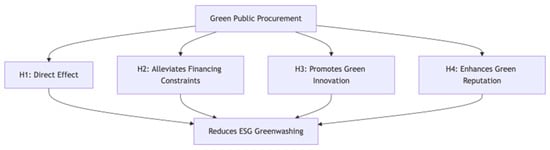

The research framework is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The transmission mechanism of green public procurement in curbing corporate ESG greenwashing.

3. Research Design

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Sources

Following the methodologies of Kou et al. [38] and Wang & Shen [20], we selected A-share listed companies in China from 2015 to 2020 as the research sample. The year 2015 marks the starting point as China Government Procurement website has disclosed the government procurement contract data since 2015. Given the high comparability between Bloomberg and Hexun ESG rating methodologies and evaluation processes, this study used ESG rating data from both institutions to construct ESG greenwashing index. As a Chinese ESG rating agency, the Hexun localized assessment system provides an important reference for sustainable investment and corporate responsibility management. In contrast, Bloomberg’s globally recognized ESG assessment system provides a comparative benchmark from an international perspective. Among them, the Bloomberg ESG ratings data are from Bloomberg ESG Database, the Hexun ESG ratings data are directly collected from its official website, while financial data and company characteristics are derived from the Database of China Stock Market Accounting Research (CSMAR).

Additionally, the original samples were processed as follows: (i) excluding ST, *ST, and PT companies; (ii) eliminating enterprises belonging to the financial industry; (iii) removing samples with missing government procurement contract amounts and key financial indicators; (iv) Winsorizing all continuous variables at the 1% level to minimize the influence of outliers. After the above processing, this paper finally obtains 6490 firm-year observations.

3.2. Definition of Main Variables

3.2.1. Dependent Variable: Greenwash

Referring to Yu et al. [2] and Zhang [9], greenwash is defined using the difference between a firm’s ESG disclosure score relative to a standardized score for its industry and its ESG performance score relative to a standardized score for its industry. A larger difference indicates a higher degree of corporate ESG greenwashing. The correlation diagnostics demonstrate that the ESG scores from the two rating agencies exhibit a significant positive correlation. The specific formula is as follows:

where represents the corporate ESG disclosure score, measured by Bloomberg ESG disclosure rating; denotes the firm ESG performance score, represented by the Hexun ESG rating. and indicate the mean of ESG disclosure and ESG performance score, respectively, of firms within the same industry, while and reflect the standard deviations of ESG disclosure and performance scores within the industry peers.

3.2.2. Core Independent Variable: GPP

The identification of GPP follows the methodologies of Zheng & Wen (2024) [39] and Wang & Shen (2025) [20] using the text analysis method, which can measure the amount of GPP and the number of orders obtained by enterprises more accurately. Specifically, the identification process consists of three steps: First, we collected more than 320,000 government procurement contracts from 2015 to 2020 through Python (version 3.13) crawler technology and matched the supplier names with the information of listed companies and their affiliates. Second, based on the policy documents such as the “Government Procurement List of Environmental Labeling Products”, “Government Procurement List of Energy-Saving Products”, and “Basic Requirements for Government Procurement of Green Buildings and Green Building Materials”, we determined a range of green procurement keyword libraries for computers, servers, printers, etc. Then, we identified the “contract name” and “main subject matter name” in the procurement contracts, from which the government procurement contracts containing any one of the keywords in the keyword libraries were preliminarily screened out. Third, considering that since 2019 China has no longer issued the Government Procurement List of Energy-Saving Products and the Government Procurement List of Environmentally Labeled Products, and instead implements preferential and mandatory procurement based on item catalogs and certification certificates, for the 2019–2020 samples, we manually verified whether the suppliers and purchased products in each government procurement contract held certification issued by the relevant authorities for energy-saving products or environmentally labeled products. Based on this verification, we determined whether each contract qualified as GPP.

In total, we obtained 6940 firm-year observations. Since a single firm may receive multiple government green procurement contracts within a year, 516 listed companies were matched with GPP contracts. GPP is defined as the natural logarithm of one plus the ratio of the total annual government procurement contracts to operating revenues.

3.2.3. Control Variable

To mitigate the influence of other economic characteristics on corporate ESG greenwashing behavior, we control the following variables of the listed companies: Company Size (Size), Leverage Ratio (Lev), Return on Equity (ROE), Cash Flow Ratio (Cashflow), CEO Duality (Dual), Equity Concentration (Top5), Board Independence (Indep), Board Size (Board), Institutional Shareholding (INST), Years of Firm’s Establishment (FirmAge). Definitions for the specific variables are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variable definitions and descriptions.

3.3. Model Design

To investigate the impact of GPP on corporate ESG greenwashing, we construct the following double fixed-effects model for validation:

where denotes the level of greenwashing of firm in year t, indicates the government green procurement of listed company in year t, and stands for a series of control variables. and represent firm-fixed and year-fixed effects, respectively, while is the random error term.

If Hypothesis 1 is confirmed, the coefficient of would be significantly negative, indicating that GPP would suppress corporate ESG greenwashing.

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 reports the descriptive statistics for the main variables. The Greenwash variable exhibits a wide range, with a maximum value of 4.121 and a minimum value of −4.379, reflecting substantial variation in the ESG greenwashing phenomenon among the sample firms. Additionally, the values for GPP range from 0 and 0.236, suggesting that the proportion of GPP is generally low. The distributions of the remaining variables are generally consistent with prior studies and are at reasonable levels.

Table 2.

Summary statistics.

4.2. Baseline Regression

Table 3 reports the baseline regression results examining the impact of GPP on corporate ESG greenwashing. Column (1) incorporates only the core independent variables, column (2) adds firm-level control variables, and column (3) further incorporates both firm and year fixed effects. The regression results show that the regression coefficients of GPP remain significantly negative at the 1% level, robustly supporting its inhibitory effect on ESG greenwashing. In terms of economic significance, the GPP in Column (3) reduces the greenwash level of the purchased enterprises by 1.093 units on average, approximately 26.5% of its maximum value. It shows that GPP can effectively inhibit corporate ESG greenwashing, thus Hypothesis 1 is verified.

Table 3.

Baseline regression results.

4.3. Endogeneity Analysis

4.3.1. Instrumental Variable Method

To mitigate potential endogeneity concerns arising from reverse causality and omitted variables, this study employs an instrumental variable (IV) approach following the method proposed by Lewbel [36]. In this paper, firms receiving government procurement orders are categorized by industry and province, and the cubic deviation of GPP from its mean is used as an instrumental variable (Lewbel IV). In the first-stage regression, the instrumental variable must satisfy two conditions: the coefficient of Lewbel IV should be statistically significant, and the Cragg–Donald Wald F-statistic should exceed the empirical threshold of 10, ensuring that the instrument is not weak. Next, the predicted values of GPP from the first stage are used as the key independent variable in the second-stage regression. If the core independent variable is significantly negative in the second-stage regression, it would support the validity of instrumental variables and confirm the inhibitory effect of GPP on corporate ESG greenwashing.

The results, presented in Table 4, support the robustness of our findings. Column (1) shows that the coefficient of Lewbel IV is significantly positive at the 5% level and the Cragg–Donald Wald F-statistic substantially exceeds the conventional threshold of 10, indicating that the instrument is strong and relevant. Furthermore, as shown in column (2), the estimated coefficient of GPP remains significantly negative at the 1% level, corroborating the baseline results and affirming the causal inhibitory role of GPP in curbing firms’ ESG greenwashing.

Table 4.

Endogeneity test results.

In addition, we follow the approach of Acemoglu et al. (2001) [40] by including the instrumental variable directly as an additional control variable in the baseline regression model. As shown in column (3) of Table 4, when the Lewbel IV is incorporated into the baseline regression equation, the coefficient of the instrumental variable itself becomes statistically insignificant. This result indicates that the instrumental variable is uncorrelated with the error term in the baseline model and affects corporate greenwashing only through its influence on government green procurement. Therefore, the instrumental variable meets the requirement of the exclusion restriction.

4.3.2. Heckman Estimation

To address potential self-selection bias of data samples, we apply the Heckman two-stage method. In the first stage, we construct a dummy variable that equals 1 if an enterprise secures a GPP contract in a given year, and 0 otherwise. Subsequently, we use a Probit model with the same controls as in the baseline regression model to estimate the probability of obtaining green procurement orders and derive the Inverse Mills Ratio (IMR). In the second stage, we include the IMR as an additional control variable in Equation (1) to correct for selection bias.

The results, presented in column (4) of Table 4, show that the IMR is significantly negative at the 10% level, indicating the presence of sample self-selection in the baseline estimates. However, after considering sample self-selection, the coefficient of GPP remains significantly negative, confirming that GPP remains effective in mitigating corporate ESG greenwashing.

4.4. Test for Robustness

4.4.1. Adjust Sample Period

To ensure the reliability of our findings, we conduct an additional test by restricting the sample period to 2015–2018. This adjustment is made because green attributes of government procurement contracts after 2019 were manually verified, potentially introducing measurement inconsistencies. As shown in column (1) of Table 5, the coefficient of GPP remains significantly negative at the 1% level, reinforcing the robustness of our baseline results.

Table 5.

Results of robustness tests.

4.4.2. Change the Variable Measurement Methods

First, we replace the dependent variable. To address potential limitations in the construction of the original greenwashing measure, we also incorporated data from another authoritative ESG rating agency in China, Huazheng, to remeasure ESG greenwashing. The specific calculation method is shown in Equation (3), Bloomberg ESG disclosure scores and Huazheng ESG performance scores are normalized to a [0, 1] range, and their difference is taken as Greenwash_Huazheng. The regression results, reported in column (2) of Table 5, show that the coefficient of GPP remains significantly negative, further confirming the robustness of our findings.

Next, we substitute the core independent variable with the logarithm of one plus the number of government green procurement contract orders (lnGPPnum). As shown in column (3) of Table 5, the coefficient on lnGPPnum remains statistically significant and negative, which verifies the results remain robust.

4.4.3. Alternative Fixed Effects

To control the possible problem of omitted variables at the city and time level, this paper adopts the joint city-year fixed effects (City/Year). At the same time, considering that firms’ ESG greenwashing behavior may be affected by the environment in which they are located, the joint city-year fixed effect is replaced by the joint province-city fixed effects (Province/City). As reported in columns (4) and (5) of Table 5, the coefficients of GPP remain significantly negative at the 5% and 1% levels, respectively. These results further affirm the robustness of our conclusions.

4.4.4. Lagged Independent Variable

To account for potential lagged effects of government green procurement on corporate ESG greenwashing, the regression analysis is re-conducted using government green procurement scale (L_GPP) lagged by one period. The estimation results are shown in column (6) of Table 5, consistent with the main findings.

5. Further Analysis

5.1. Mechanism Test

To further explore the pathways of GPP on corporate ESG greenwashing, we follow the approach of Chen et al. (2020) [41] to construct the following model for mechanism test:

where Medi,t denotes the mediating variables, which represent financing constraints, green innovation, and green reputation, respectively. All other variables are set to keep the same as Equation (1).

5.1.1. Mechanism: Alleviating Financing Constraints

Theoretically, government green procurement governs corporate ESG greenwashing by alleviating financing constraints. Following Musso and Schiavo (2008) [42], we measure financing constraints using the FC index—a composite indicator comprising seven dimensions: firm size, profitability, liquidity, cash flow generation capacity, solvency, trade credit to total assets ratio, and net tangible assets ratio. The FC index ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating more severe financing constraints. As shown in column (1) of Table 6, the coefficient of FC index is negative and statistically significant at the 1% level, indicating that government green procurement effectively alleviates firms’ financing constraints. These results provide empirical support for Hypothesis 2.

Table 6.

Results of mechanism tests.

5.1.2. Mechanism: Promoting Green Innovation

According to theoretical analysis, government green procurement may also curb ESG greenwashing by stimulating green innovation. Adopting the measure from Wang and Shen (2025) [20], we measure green innovation (GTI) as the natural logarithm of one plus the number of corporate green patent applications. As reported in column (2) of Table 6, the coefficient of GPP is significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating that government green procurement substantially promotes green innovation among firms. This finding provides empirical support for Hypothesis 3.

5.1.3. Mechanism: Enhancing Green Reputation

Another channel is the enhancement of firms’ green reputation. Following Ran et al. (2025) [43], which measures corporate green reputation (GR) by taking the natural logarithm of one plus the total number of positive online and newspaper reports on a company per year. Column (4) of Table 6 shows that GPP has a significantly positive coefficient at the 1% level, indicating that government green procurement effectively improves corporate green reputation. Hypothesis 4 is thus confirmed.

5.2. Heterogeneity Test

5.2.1. Degree of Industry Competition

Industry competition may shape the impact of government green procurement on corporate environmental behavior. This paper adopts the Herfindahl index to capture the intensity of industry competition, with lower values indicating greater competition. Based on the median value of the index, enterprises are divided into high-competition group (Herfindahl index is below the median) and low-competition group (Herfindahl index is above the median). Regression results, presented in columns (1) and (2) of Table 7, show that the coefficient of GPP is significantly negative at the 1% level in the high-competition group, whereas it is statistically insignificant and positive in the low-competition group. These findings indicate that government green procurement strongly discourages greenwashing in high-competition industries, while the effect on enterprises in low-competition industries is not obvious.

Table 7.

Heterogeneity analysis.

This difference may be due to the fact that firms in competitive industries must respond quickly to policy incentives by improving real environmental performance rather than resorting to ESG greenwashing, in order to secure and maintain government procurement contracts. In contrast, firms in less competitive industries face weaker market pressure, tend to circumvent the policy pressure at a lower cost.

5.2.2. Analyst Attention

Analyst attention has been shown to incentivize greater corporate engagement in ESG practices [44]. Government procurement participants often attract greater market attention, and such external monitoring can constrain the strategic disclosure of corporate ESG information. In this study, analyst attention is measured as the natural logarithm of one plus the number of analysts following a firm in a given year. Firms are then classified into high- and low-analyst-coverage groups based on the annual sample mean. As shown in Columns (3) and (4) of Table 7, GPP has a significantly negative coefficient in the high-attention group but is insignificant in the low-attention group. This suggests that analyst supervision partially restrains corporate ESG greenwashing.

The rationale is as follows: First, analysts can reduce information asymmetry and constrain managerial opportunism [45]. As external monitors, analysts exert sustained pressure that enhances corporate transparency, reducing the likelihood of ESG greenwashing [46]. Furthermore, environmental regulation often requires substantial investment in pollution control and technological upgrading, which boosts actual ESG performance. Finally, analysts also help convey accurate environmental performance to the market, while low attention can exacerbate information asymmetry and foster ESG greenwashing.

5.2.3. Enterprise Life Cycle

The influence of government green procurement on ESG greenwashing may vary across different stages of the corporate life cycle. Following the methodology of Song&Ma [47] and Zhao&Li [48], we classify firms into three stages—growth, maturity, and decline—using a compositive scoring system based on sales revenue growth rate, retained earnings ratio, capital expenditure ratio, and firm age. As shown in Columns (5)–(7) of Table 7, GPP significantly reduces greenwashing in mature firms, but has no significant effect in the growth or decline stage.

This heterogeneity can be explained as follows: In the growth stage, firms prioritize market expansion over costly environmental reforms. By contrast, mature firms have stronger capital reserves and better governance, which can bear the cost of real environmental. Finally, in the decline stage, some enterprises may obtain government green procurement orders through ESG greenwashing to alleviate the financial pressures.

6. Research Conclusion and Policy Implications

This study empirically examines the impact of government green procurement on corporate ESG greenwashing from a strategic disclosure perspective, using a sample of A-share listed companies in China from 2015 to 2020. The findings indicate that government green procurement significantly curbs corporate ESG greenwashing. Mechanism analysis further reveals that such procurement effectively governs corporate greenwashing through three primary channels: alleviating financing constraints, stimulating green innovation, and enhancing green reputation. Robustness tests consistently confirm the stability of the inhibitory effect. Moreover, the governance effect is particularly pronounced for enterprises in highly competitive industries, with high analyst attention, and at the maturity stage.

Based on these findings, the study proposes the following three policy recommendations:

First, enhancing the effectiveness of government green procurement to curb greenwashing. Given that energy-saving and environmentally friendly products accounted for only 2.75% of total government procurement in 2023 (measuring the share of the procurement policy for energy-saving and environmentally friendly products in overall government procurement), the government should not only expand the scale of green procurement but also set clear targets at all administrative levels and optimize procurement procedures. Moreover, policymakers can stimulate market demand for green products and services by offering financial incentives to companies that actively fulfill environmental responsibilities and surpass energy conservation and emissions reduction targets. Such measures can encourage stronger commitment to green innovation and accelerate the transition toward sustainability.

Second, implementing differentiated procurement strategies tailored to enterprise characteristics. The heterogeneity analysis indicates that the governance effect of government green procurement on corporate ESG greenwashing is more pronounced in highly competitive industries, firms with high analyst attention, and mature-stage companies. Therefore, mature-stage firms can be prioritized in procurement to serve as benchmarks among suppliers; firms with high analyst attention can be targeted strategically, transforming government procurement recognition into a significant market reputation premium; and for firms in highly competitive industries, procurement quotas should be appropriately increased and policy support strengthened to guide the industry toward a green transformation.

Third, establishing an ESG governance system with coordinated oversight from government, market, and society. At the government level, standardized ESG disclosure and third-party verification systems should be established to improve ESG authenticity from the source. At the market level, efforts should be made to promote the integration of corporate environmental performance into investment decisions within the capital markets and enhance support through green finance, thereby directing capital flows toward high-quality, green, and low-carbon enterprises. At the societal level, it is essential to strengthen environmental labeling certification systems and encourage active public participation in monitoring and reporting environmental pollution incidents.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.L.; methodology, Z.L. and H.Z.; software, Z.L.; validation, Z.L.; formal analysis, Z.L.; investigation, Z.L.; resources, Z.L.; data curation, Z.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.L.; writing—review and editing, Z.L. and H.Z.; visualization, Z.L.; supervision, H.Z.; project administration, H.Z.; funding acquisition, H.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Hunan Provincial Department of Education-funded research project “The Mechanisms and Strategies of Promoting the Modernization of University Governance through Internal Auditing in Higher Education Institutions” (21A0219).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made. available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gao, Y.; Chen, Y. Watchdogs or Enablers? Analyzing the Role of Analysts in ESG Greenwashing in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, E.P.-Y.; Bac Van, L.; Chen, C.H. Greenwashing in environmental, social and governance disclosures. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2020, 52, 101192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Tao, L.; Li, C.B.; Wang, T. A Path Analysis of Greenwashing in a Trust Crisis Among Chinese Energy Companies: The Role of Brand Legitimacy and Brand Loyalty. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, K.; Wan, F. The Harm of Symbolic Actions and Green-Washing: Corporate Actions and Communications on Environmental Performance and Their Financial Implications. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, T.P.; Montgomery, A.W. The Means and End of Greenwash. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 223–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Boiral, O.; Iraldo, F. Internalization of Environmental Practices and Institutional Complexity: Can Stakeholders Pressures Encourage Greenwashing? J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 147, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzetti, M.; Gatti, L.; Seele, P. Firms Talk, Suppliers Walk: Analyzing the Locus of Greenwashing in the Blame Game and Introducing ‘Vicarious Greenwashing’. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 170, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Wang, A.; Du, K. Environmental tax reform and greenwashing: Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Energy Econ. 2023, 124, 106873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. Green financial system regulation shock and greenwashing behaviors: Evidence from Chinese firms. Energy Econ. 2022, 111, 106064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. Does green finance really inhibit extreme hypocritical ESG risk? A greenwashing perspective exploration. Energy Econ. 2023, 121, 106688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, F.; Bernini, F. ESG controversies and the cost of equity capital of European listed companies: The moderating effects of ESG performance and market securities regulation. Int. J. Account. Inf. Manag. 2022, 30, 641–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Sun, Z.; Zhu, W.; Ma, L.; Dong, Y.; Sun, X.; Wu, F. How does multi-agent govern corporate greenwashing? A stakeholder engagement perspective from “common” to “collaborative” governance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Morotomi, T. Impacts of green public procurement on eco-innovation: Evidence from EU countries. Glob. Public Policy Gov. 2022, 2, 154–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, B.; Zipperer, V. Does green public procurement trigger environmental innovations? Res. Policy 2022, 51, 104516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, L.W.; Dickinson, N.M.; Chan, G.Y. Green procurement in the Asian public sector and the Hong Kong private sector. Nat. Resour. Forum 2010, 34, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Liu, X.; Li, B.; Shi, D. Environmental Regulation and Corporate Greening Governance: New Evidence Based on the Distance Between Enterprises and Environmental Protection Bureaus. Sage Open 2025, 15, 21582440251366012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Chen, J.; Liu, B.; Huang, Y.; Shu, M. Will informal environmental regulation become a new incentive to reduce corporate ESG greenwashing? Empirical evidence from public environmental concerns. Appl. Econ. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, B.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Q. Does Environmental Uncertainty Increase the Likelihood of Greenwashing? The Roles of Government Subsidies and Media Attention. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2025, 32, 2616–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Li, H.; Lu, J. How does energy policy uncertainty perception affect corporate greenwashing behaviors? Evidence from China’s energy companies. Energy 2024, 306, 132403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Shen, Z. The impact of green public procurement on corporate ESG performance. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 391, 126394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, B.L.; Certo, S.T.; Ireland, R.D.; Reutzel, C.R. Signaling theory: A review and assessment. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, K. Direct demand-pull and indirect certification effects of public procurement for innovation. Technovation 2021, 101, 102198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Shin, K.; Lee, J.-D. Demand-side policy for emergence and diffusion of eco-innovation: The mediating role of production. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 259, 120839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, J. Government as customer of last resort: The stabilizing effects of government purchases on firms. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2020, 33, 610–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.A.; Li, B. Customer-base concentration, investment, and profitability: The US government as a major customer. Account. Rev. 2020, 95, 101–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giovanni, J.; García-Santana, M.; Jeenas, P.; Moral-Benito, E.; Pijoan-Mas, J. Government Procurement and Access to Credit: Firm Dynamics and Aggregate Implications; Federal Reserve Bank of New York: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Li, W.; Seppanen, V.; Koivumaki, T. Effects of greenwashing on financial performance: Moderation through local environmental regulation and media coverage. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 820–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, F.; Chen, J.; Yang, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, B. Financial constraints and corporate greenwashing strategies in China. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 1770–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. Are firms motivated to greenwash by financial constraints? Evidence from global firms’ data. J. Int. Financ. Manag. Account. 2022, 33, 459–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, C.; Toffel, M.W.; Zhou, Y. Scrutiny, Norms, and Selective Disclosure: A Global Study of Greenwashing. Organ. Sci. 2016, 27, 483–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.; Li, B.; Li, N.; Lou, Y. Major government customers and loan contract terms. Rev. Account. Stud. 2022, 27, 275–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Chen, L.; Zhu, Y.; Maak, T. Social Trust and Corporate Greenwashing: Insights from China’s Pilot Social Credit Systems. J. Bus. Ethics 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Bravo, V.; Caniato, F.; Caridi, M. Sustainability in multiple stages of the food supply chain in Italy: Practices, performance and reputation. Oper. Manag. Res. 2019, 12, 40–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.; Teng, M.; Teng, R. The impact of green public procurement on corporate green innovation: Evidence from machine learning and text analysis. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2024, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S. The driver of green innovation and green image–green core competence. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 81, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, A.K.; Lai, K.H.; Cheng, T. Environmental governance of enterprises and their economic upshot through corporate reputation and customer satisfaction. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2012, 21, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedari, L.K.; Jubb, C.; Moradi-Motlagh, A. Corporate climate-related voluntary disclosures: Does potential greenwash exist among Australian high emitters reports? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 3721–3739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, M.; Zhang, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Shan, Z. The heterogeneous impact of green public procurement on corporate green innovation. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 203, 107441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Wen, J. Green public procurement and corporate environmental performance: An empirical analysis based on data from green procurement contracts. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 96, 103578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Johnson, S.; Robinson, J.A. The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation. Am. Econ. Rev. 2001, 91, 1369–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Fan, Z.; Gu, X.; Zhou, L.-A. Arrival of young talent: The send-down movement and rural education in China. Am. Econ. Rev. 2020, 110, 3393–3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musso, P.; Schiavo, S. The impact of financial constraints on firm survival and growth. J. Evol. Econ. 2008, 18, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, Z.; Ji, P. Environmental protection tax legislation and corporate reputation in China: A legal perspective. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 74, 106790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Guo, X.; Yue, P. Media coverage and corporate ESG performance: Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 91, 103003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.F. Analyst coverage and earnings management. J. Financ. Econ. 2008, 88, 245–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Francoeur, C.; Brammer, S. What drives and curbs brownwashing? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 2518–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.X.; Ma, W.Y. ESG and green innovation: Nonlinear moderation of public attention. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Li, H. Does ESG rating promote corporate green technology innovation: Micro evidence from Chinese listed companies. South China J. Econ. 2024, 2, 116–135. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.