1. Introduction

Transitioning to sustainable agriculture is complex due to farm system interdependencies, decision-making levels, and farm diversity [

1]. Improved sustainability outcomes is one of the key focus areas of digitalization efforts in the agriculture sector [

2], though significant policy and regulatory hurdles remain [

3]. Farm-level sustainability assessment methods classified as “calculators” [

4] have gained popularity for their accessibility. These tools, which are typically web-, Excel-, or software-based, use simplified models to make sustainability issues more tangible and to support farm-level decision-making [

5]. A wide range of such farm-level tools exist—Chopin et al. (2021) [

6] identified 119 tools with highly diverse characteristics in terms of scope, framing of sustainability, and indicators used. For example, the Cool Farm Tool has been adopted by some stakeholders to support GHG emissions reduction in Canadian agriculture [

7]. The HOLOS model has been used to study the diversity of farm/livestock management practices and their associated GHG emissions [

8]. The Sustainability Monitoring and Assessment RouTine (SMART)-Farm Tool has been used to study the sustainability implications of European agriculture management practices using the Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO)’s Sustainability Assessment of Food and Agriculture Systems (SAFA) framework [

9].

Despite the importance of end-user participation in sustainability assessment, research indicates that farm-level decision support tools often fail in this regard [

10]. A key challenge is the disconnect between users and developers regarding embedded value systems, data assumptions, time constraints, and usability [

5,

11,

12,

13]. The Bellagio Sustainability Assessment and Measurement Principles—commonly referred to as the Bellagio STAMPs [

14]—emphasize the necessity of user involvement in any sustainability assessment.

Participatory design is a specific form of stakeholder engagement activity that focuses on one particular stakeholder group—users. Simply put, ‘

the people destined to use any system should play a critical role in designing it’ [

15]. At its heart, participatory design deals with designing future scenarios and collaborative design processes [

16]. The object of study in participatory design is the tacit knowledge of users in designing technological solutions for work environments. Tacit knowledge is implicit, holistic, and difficult to articulate explicitly. It is ignored in rationalist approaches that assume one best solution to a problem. Participatory design rejects the notion of knowledge being formalized and regulated—one in which the user’s knowledge is considered inferior. It rather uses a constructivist approach to knowledge. Users’ knowledge is based on practices and interactions that are interpretive, and hence, cannot be completely formalized or optimized. Such knowledge is not readily available to designers. As a result, there is a strong ethical foundation to participatory design [

17]. It considers users as legitimate stakeholders in the design process, not just informants. In addition to ethical foundations, there are also pragmatic reasons for the use of participatory design. The pragmatic rationale focuses on the need for mutual learning. Users require knowledge about technological solutions. Designers have this knowledge but require knowledge about the users and their practices to effectively design these solutions. Thus, providing avenues for mutual learning is a crucial element of participatory design. It ensures that the solutions have logical foundations in the practices it is intended to support [

16]. It also ensures that stakeholders have realistic expectations of the project and reduces resistance to new technologies. The political rationale is the commitment to including relevant stakeholders in a decision process—in this case, users. It is inspired from the ideals of participatory democracy, which insist on democratized and decentralized decision-making [

18].

Participatory design is not without its challenges. Intended for traditional workplaces, some of the traditional organizational principles of participatory design cannot be used in modern application contexts. It is also not easy to strictly adhere to participatory design principles when developing consumer products, as opposed to modifying work environments [

16]. The significant differences in the effectiveness of participatory design when facilitated by inexperienced designers is also a barrier for its wider adoption [

19]. Lack of relational expertise to establish new and dynamic connections can also affect participatory design processes [

20,

21]. The emphasis on the tacit knowledge of users can be considered a limitation as it does not support the radical changes that might be needed in addressing a problem. It is argued that participatory design is only suited for evolutionary changes, thus limiting its use in various contexts. It is also argued that participatory design empowers stakeholders functionally but not democratically. They are involved in designing technologies (via prototyping), but only those that deal with specific work situations—as opposed to the work environment or organization at large [

17]. Language can limit the effectiveness of the engagement process when discussing design aspects, while the objectives of users can restrict the range of solutions that are considered [

19].

Participatory design has also been challenged by researchers in ethnography for inaccurate use of ethnographic methods—merely using these methods does not address the problems of understanding the perspective of users [

17]. There are limitations in interpretation, extrapolation, and generalization of the users’ responses [

19]. Finally, there are also practical limitations such as time, resources, and commitment with participatory design (as with most stakeholder engagement processes).

Participatory design was intended for developing technologies for improved work environments, and that remains the major context of application of participatory design research. However, a review of research in the field shows that application of participatory design is diversifying into new areas, including sustainability and environmental management [

22]. Sustainability is seen as a topic that requires complex management of heterogenous interests with multiple levels of application and scale. Participatory design is considered as a suitable approach with well-defined techniques to tackle these problems [

23]. For example, Gaziulusoy and Ryan (2017) [

24] describe the potential for participatory design to help the transition of Australian cities to low-carbon, resilient futures as part of the Visions and Pathways 2040 project. Participatory design can also help in energy transitions by bridging the gap between theoretical drivers for change and the realities of people’s energy use and needs [

23]. Capaccioli et al., (2016) [

25] describe the use of participatory management of renewable energy systems as common-pool resources in small communities.

Participatory design has been used in the development of a sustainability assessment framework for coastal management at a local scale [

17]. Clune and Lockrey (2014) [

26] used a combination of a simplified Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and participatory design to identify strategies for environmental improvements in aged care facilities. Cramer (2011) [

27] has applied participatory design to the fashion industry to improve the longevity of clothes—leading to sustainable behavioral change. Mushtaq and Hall (2009) [

28] identify the changes needed to traditional approaches to participatory design in the global south by studying the successes and failures of participatory implementation of health care technology in India. The benefits of combining ecological and participatory design by architects in improving the sustainability of built environments has also been extensively analyzed [

29,

30,

31].

Agricultural sustainability research and management has also seen a proliferation in the use of participatory design. For example, stakeholder workshops were used parallel to crop growth modeling in the Netherlands to develop a portfolio of climate change adaptation measures [

32]. This approach was found to be especially useful in addressing extreme climate events, pests, and diseases, which are difficult to include in modeling-based impact assessments. Integrated crop–livestock farming models were similarly designed, monitored, and assessed using participatory design in France as a potential approach to sustainable farming [

33]. Andrieu et al. (2012) [

34] used participatory design to validate the design and implementation of a whole-farm model to be applied in assessments of West African farms. A support program for farmers in Australia called FARMSCAPE was formulated and implemented using participatory design. The involvement of stakeholders in FARMSCAPE was found to enhance farm-level decision-making by ensuring respectful science-based engagement with initially skeptical farmers [

35].

The National Environmental Sustainability and Technology Tool (NESTT) is an online, life cycle-based sustainability assessment and decision support tool designed to help Canadian egg farmers measure and manage the sustainability impacts of egg production [

36]. Developed by the University of British Columbia’s Food Systems PRISM Lab in collaboration with Egg Farmers of Canada (EFC) and the software solutions provider MIREGO, NESTT aims to drive industry-wide sustainability improvements. While voluntary, its success depends on broad adoption, avoiding the limited uptake seen with other farm-level sustainability tools [

3]. Engaging farmers in the development process enhances ownership and usability [

13], ensuring NESTT supports decision-making rather than dictating outcomes [

37]. This participatory approach fosters mutual learning between developers and farmers, integrating practical farm knowledge into tool design while providing farmers with insights into its methodology.

Given NESTT’s role as a web-based decision support tool for farmers, a participatory design approach was deemed ideal for its development. This study outlines the methods and outcomes of this approach, with the primary goal of aligning NESTT’s design with the real-world needs of Canadian egg farmers. Additional objectives include the following:

Establishing dialog and mutual learning about the sustainability assessment processes being adopted within the Canadian egg industry.

Supporting NESTT’s widespread adoption by fostering farmer ownership and engagement.

Demonstrating that participatory approaches can be integrated into structured, top-down sustainability assessments. While quantitative farm-level assessment methods can support monitoring and benchmarking, they often lack user participation [

38]. NESTT’s development process exemplifies how a structured sustainability assessment tool can incorporate end-user input.

3. Results

3.1. Exploration

The exploration phase was mostly observational, with the primary focus on ensuring that all members of the design team had a basic understanding of egg farming in Canada. The design team were able to observe the differences in management practices and day-to-day operations for different housing systems and farms of different sizes. The exploratory visits were also useful in gaining insights into how and what types of data are collected and how readily available they are to farmers. Based on these farm visits and through consulting the sustainability-related literature relevant to the Canadian egg industry, several priority considerations were identified as being the key focus areas to address in NESTT. These were hen productivity, feed use, water use, energy use, mortality, manure management, and spent hen management.

The provincial egg board members—who are farmers themselves—voiced their approval for the development of a farm-level sustainability tool focused on these seven focus areas during the workshop held in December 2019. Given the intense scrutiny on the livestock sector, they agreed that it would be beneficial for the Canadian egg industry to be proactive in developing a tool like NESTT and pursue lowering the environmental footprint of their products. The members requested the design team to study the possibility of integrating the assessment component of NESTT with other on-farm programs to ease the burden on producers for data collection. As a result, a gaps analysis was undertaken comparing the data requirements for NESTT, the Egg Farmers of Canada Animal Care program, and the ‘Start Clean—Stay Clean’ program. Although there was some overlap between the programs in three of the seven priority focus areas, aspects such as energy use were not covered at all in the other programs. It was hence decided that it was best for NESTT to be a standalone program in the short-term, especially given that the other two programs were already mandatory for all Canadian egg farms.

The board members also raised the issue of most farmers not being able to furnish energy use data and suggested adding features in NESTT for farmers to use default, substitute data when required. Members were also requested to provide their opinions on the planned participatory design activities during this workshop. The members recommended identifying a pool of interested farmers to contribute to the design and development of NESTT and to not contact farmers randomly. The members also recommended organizing regular workshops such as the one we were in whenever they were gathered in the same locations to conduct group-based engagement activities (this was, however, ultimately not possible due to the COVID-19 pandemic).

3.2. Pre-Launch Discovery

A total of 70 farmers were sent email invitations to respond to the survey and 54 farmers responded to the survey (77% response rate), of which 38 farmers completed the survey. From the 16 incomplete surveys, 4 were included in the data analysis. Overall, 42 survey responses (60% of invitations sent) were included in the analysis. This represents about 4% of all egg farmers in Canada.

3.2.1. Representative Information

Farmers from Ontario accounted for approximately 25% of the survey responses included in the analysis. British Columbia (18%), Manitoba (18%), and Alberta (15%) were the other well represented provinces. The rest of the responses were made up of farmers from Quebec, Saskatchewan, Nova Scotia, and the Northwest Territories. Atlantic provinces other than Nova Scotia were not represented in the survey but New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland and Labrador together account for only 2% of egg farms in Canada. Only one survey respondent indicated having farms in multiple provinces.

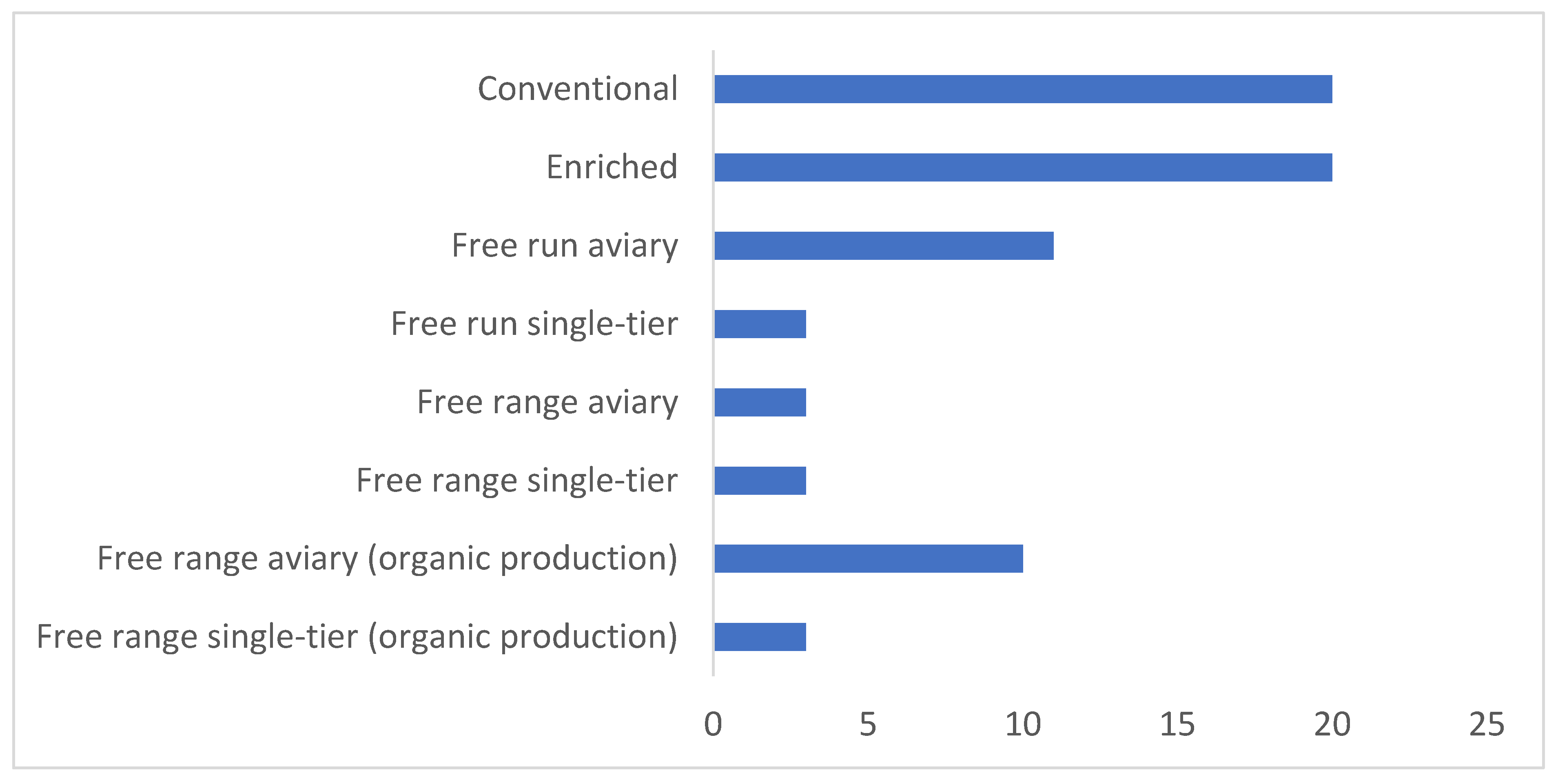

In terms of farm size, farms with 50,000 birds or above made up around 36% of all survey respondents. Farms with 20,000 to 30,000 birds were also well represented (26%). Of the 39 respondents, 20 indicated the presence of more than one housing system type on their farm. Conventional and enriched housing were both used by 20 farms, with free run aviary (11) and free range aviary-organic (10) being the other common housing systems represented (

Figure 2).

Most of the farmers (64%) responding to the survey were below the age of 40. This is consistent with the feedback from the provincial egg boards that younger farmers in Canada were likely to be more receptive to, and interested in, sustainability initiatives such as NESTT.

3.2.2. Previous Experience of Using Online Decision Support Tools

Only 40% of the farmers responding to the survey indicated having prior experience of using online decision support tools. Of the 17 farmers who indicated previous experience with online decision support tools, 11 also indicated that they had used such tools for more than one purpose. General farm management and financial management were the two main reported purposes for which online tools are used by egg farmers. The other main use of online decision support tools for farmers was learning—either information support for farm operations or investments in new technologies.

Use of online tools for assessment of environmental performance/sustainability impacts was listed by only 11% of farmers with previous experience of decision support tools. Most farmers who indicated having used online tools related to environmental/sustainability assessment listed provincial egg board environmental programs such as Alberta’s Producer Environmental Egg Program (PEEP) and Ontario’s Environmental Farm Plan as examples of online decision support tools (although these programs do not conform to the definition of DSTs as considered herein).

The majority of farmers (59%) who had previous experience with online decision support tools used such tools regularly—either at least once a week or once a month. All except one of the farmers using online tools regularly used the tools for either general farm management or financial management. Other reasons for using online decision support tools such as certification, assessment of sustainability impacts, and investment in new technology saw the tools being used less frequently—once every six months or once a year. Over 80% of the farmers with previous experience of using online tools found such tools at least moderately useful, with 41% finding it very useful. Three farmers indicated that they found online decision support tools only slightly useful—all three also indicating infrequent use (once a year).

3.2.3. Sustainability Assessment and NESTT

The majority of farmers (90%) indicated that sustainability was either moderately or very important to their farm management and operations—with a similar proportion of farmers indicating that it will remain similarly important in egg production in the future. While 57% of farmers indicated sustainability as being very important—the highest option available—only 19% of farmers considered sustainability to be a consistent factor in their decision-making. A majority (66%) of farmers said that sustainability was a factor in everyday decision-making frequently, i.e., in about 30–70% of instances.

Using a 10-point scale (1 being not at all important and 10 being very important), farmers were asked to rate various factors based on how they viewed those factors in relation to sustainability. Animal welfare and product quality were the two factors for which ~80% of farmers gave an importance score of 9 or 10. At the other end of the spectrum, only 27% of farmers considered environmental impacts to be a very important aspect of sustainability, with 36% of farmers giving a score of 6 or lower for environmental impacts. Over 75% of the respondents considered efficiency of production an important factor in sustainability while economic factors, social aspects, and stakeholder relations were all considered to be very important by over 50% of farmers (

Figure 3).

Although egg farmers have had limited experience with using online decision support tools—both related to environmental/sustainability assessments and in general—over 80% of respondents indicated that developing an industry-specific, sustainability decision support tool as being either moderately or very important for the Canadian egg industry. Roughly 70% of the farmers also indicated that they wanted a tool that they did not have to use frequently—preferably only once or twice a year.

3.2.4. Decision Support Features of NESTT

In this section of the survey, farmers were asked to rate various decision support methods for inclusion in NESTT. Benchmarking was considered a major decision support feature by respondents, with 71% rating it as a high priority. Most farmers indicated that they would like the inclusion of multiple benchmarks such as national, provincial, and housing system averages against which to compare performance. The only other feature that was considered a high priority by over 50% of the farmers was tracking farm performance over time (

Figure 4).

Knowledge transfer mechanisms were also considered high-priority features to be included in NESTT by over 40% of farmers. Almost 90% of farmers were interested in learning about farm productivity and efficiency in NESTT, while information on finance/economics, environmental impacts, resource use, and animal welfare were all requested by over 60% of farmers.

On the other hand, action plans, monitoring progress towards targets, and single sustainability scores were all considered high priority by less than 25% of the respondents. However, these features were specified as low priority by <20% of farmers, indicating that decision support features such as action plans were considered useful, just not a priority feature in NESTT.

3.2.5. Factors Influencing Effective Use of NESTT

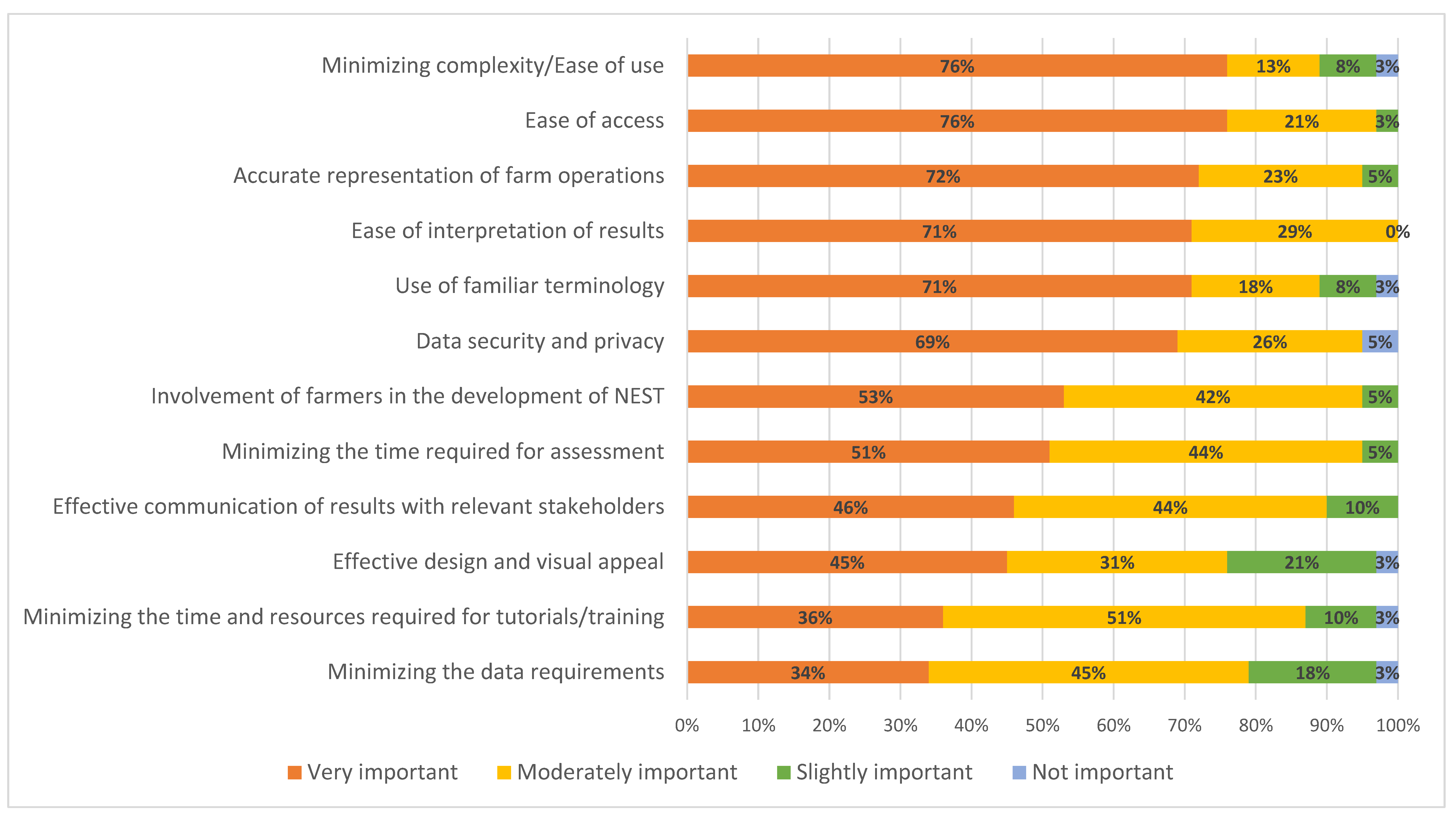

The final section of the survey focused on identifying the factors that farmers considered important to the effectiveness of NESTT. Minimizing complexity/ensuring ease of use and ensuring ease of access were the two factors specified by farmers as being the most important in ensuring the effectiveness of NESTT for its users (

Figure 5). These two factors were rated very important by over 75% of respondents. Additionally, the use of familiar terminology, accurate representation of egg farms, and ensuring ease of interpretation of the results were considered very important to the effectiveness of NESTT by over 70% of farmers. On the other hand, egg farmers responding to the survey did not see minimizing data requirements, minimizing assessment time, and minimizing time required for learning the tool as important for the effectiveness of NESTT. Overall, all of the 12 factors that were listed in the survey were rated as either very important or moderately important to the success of NESTT by the majority of farmers.

3.3. Prototyping

The interviews during the prototyping phase focused on ensuring that the five key pillars of NESTT’s design—user-centeredness, data security, aesthetic appeal, accessibility, and simplicity—were being achieved. These five pillars were identified in the survey (

Figure 5) as being key factors in ensuring acceptance and effective use of NESTT by Canadian egg farmers.

User-centeredness meant enabling accurate representation of egg farm operations to ensure the usability of the tool. One of the key topics addressed during the prototyping phase was the unit of assessment. Based on a majority of farmers indicating in the survey that they would like a tool that is used sparingly (once or twice or year), farmers were asked what was the best way to design assessments in NESTT. Options included assessing environmental performance annually for each barn, assessing performance of the whole farm (if the farm consists of multiple barns), or assessing performance per flock placed. All farmers interviewed in the prototyping phase insisted that assessing performance of each flock was the best representation of farm-level operations.

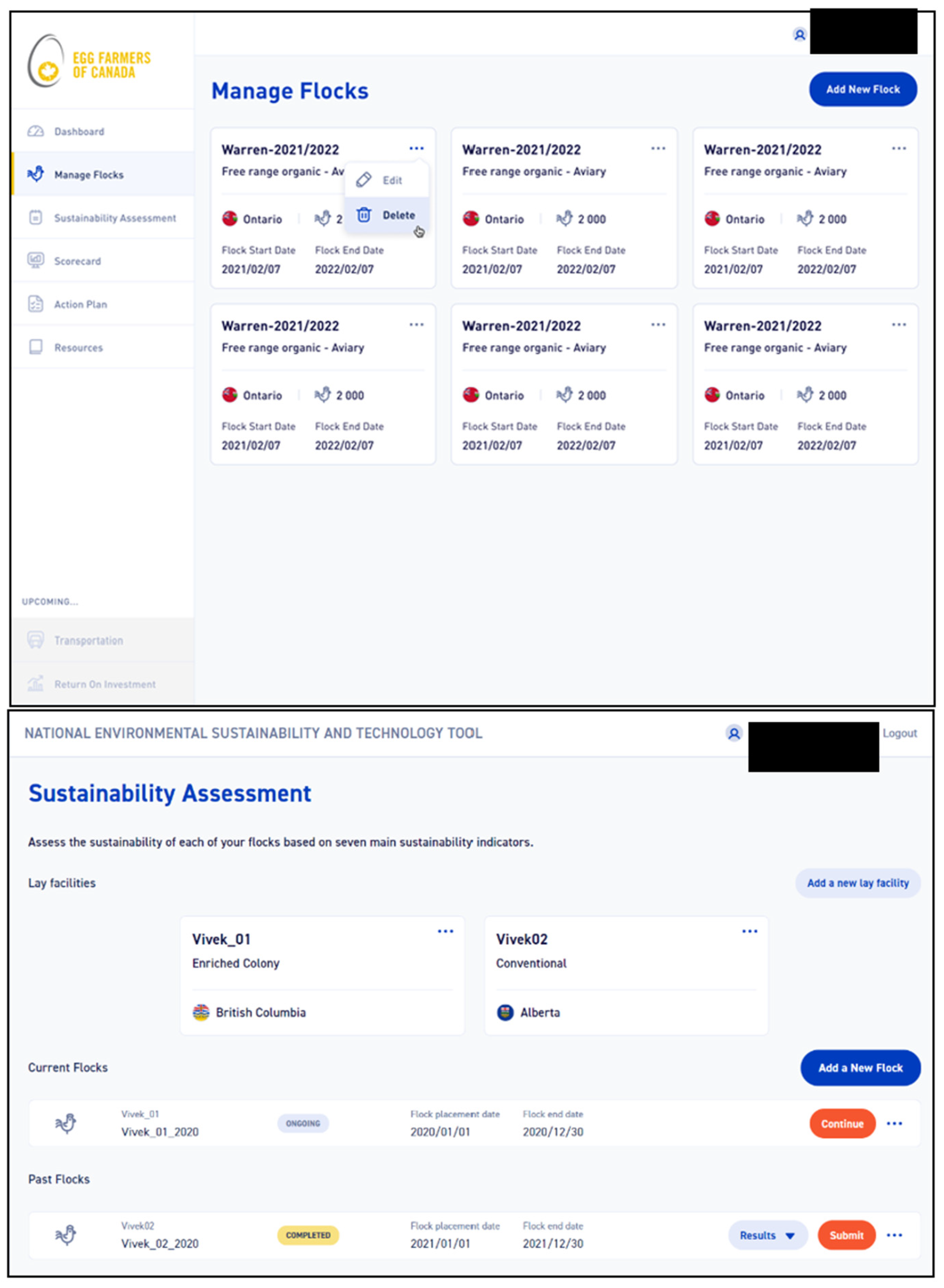

An important feature added to the final version of Lite NESTT based on feedback obtained during the prototyping phase was the inclusion of the ‘lay facility’ (

Figure 6). Farmers highlighted that organizing flocks by the lay facility in which they were housed can help improve data management in NESTT, in addition to helping farmers compare performance improvements achieved over time. Hence, in addition to being able to add and manage multiple flocks, NESTT was upgraded to allow farmers to manage multiple lay facilities and select the lay facility in which each flock was housed.

Farmers specified in the prototyping phase that the questions related to ‘energy use’ were a potential barrier to ease of access. Since this was already flagged by provincial egg board members during the exploration phase, farmers were presented with workaround options for energy-related questions. For example, farmers were presented with the option of entering the cost of their electricity bill (

$) as a potential alternative to entering electricity consumed (kWh). But most farmers insisted that this option would not be useful since most farms were likely to receive a single electricity bill that also included residential consumption. Thus, farmers would have the same problem as before regarding energy data—how much to allocate to each flock. As a result, the final design of Lite NESTT only includes two options: entering actual electricity consumed per flock (if known) or an ‘I don’t know’ option that allows farmers to use a housing system-specific average Canadian value as a default substitute (

Figure 7).

Since data security and data privacy were flagged as important concerns during the survey, farmers were presented with the design team’s solution to data confidentiality during the prototyping phase. The solution involved asking farmers to specifically agree for their data to be anonymized, aggregated, and used by Egg Farmers of Canada and researchers at the first author’s home institution to view their results on NESTT. This solution was accepted by farmers as providing a sufficient guarantee of data confidentiality as long as no economic information was being collected. However, farmers also highlighted during the prototyping phase that submission of data for aggregation cannot be a mandatory requirement to use the tool if there was a desire to achieve widespread uptake of NESTT among producers. Hence, the final version of NESTT enables farmers to experience the full functionality of the tool irrespective of their decision on data sharing.

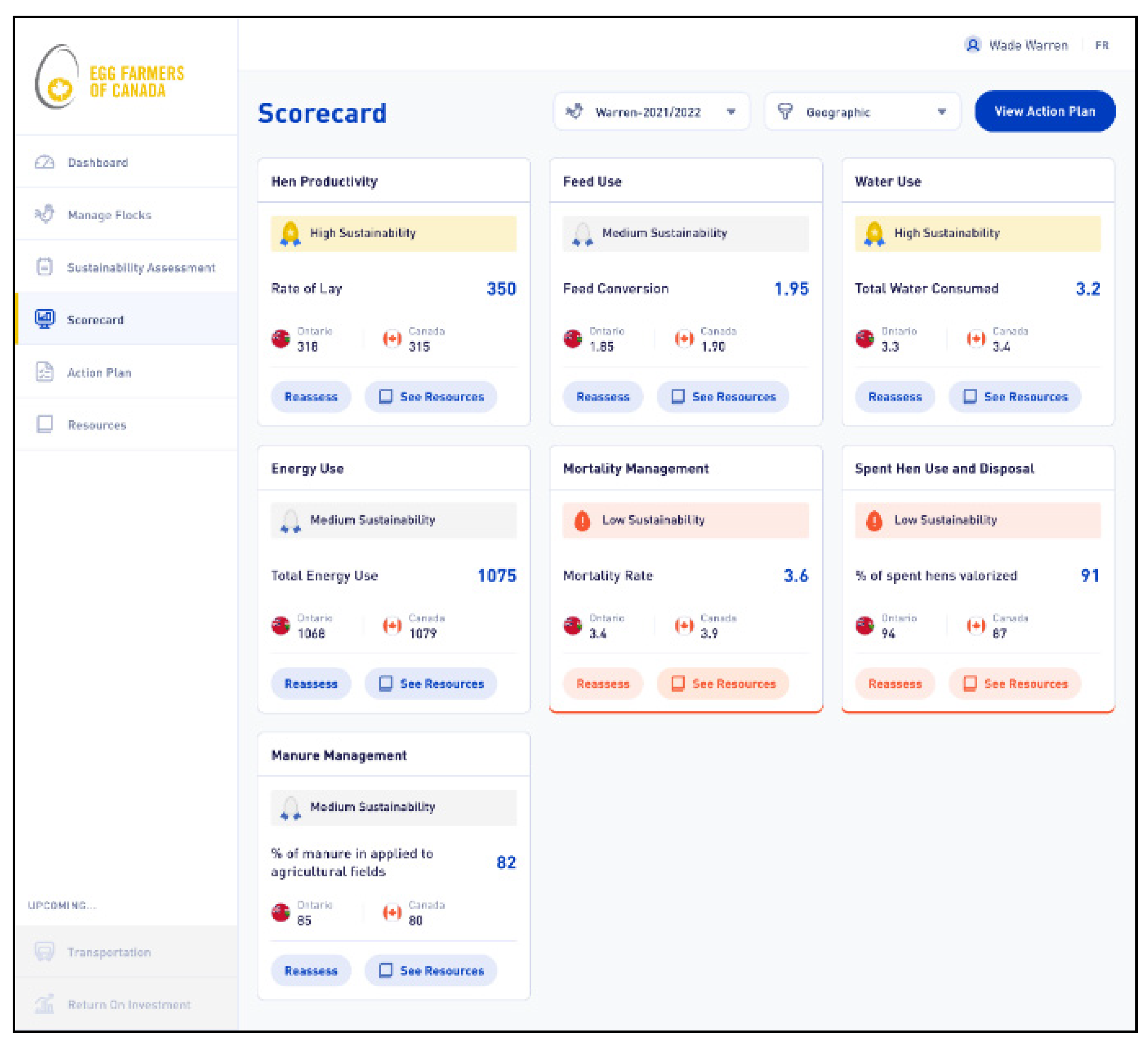

Feedback from farmers also helped to revise the initial designs of various screens in NESTT—especially the scorecard displaying the results of their assessment. Farmers insisted on the need for maximum information sharing without being overwhelmed with a wall of numbers and graphs. There was a more positive response for a list-based design compared to a tile-based design for both the flock management and scorecard pages. Farmers also highlighted that it would be beneficial to present benchmark data in different measurement units in the scorecard. For example, instead of just displaying ‘water use per tonne of eggs’ as initially planned, NESTT presents farmers with water use per bird, water use per day, and water use per tonne of eggs for the flock being assessed. The evolution of the design of the scorecard page is shown in

Figure 8 as an example of how aesthetic appeal and simplicity were improved during the prototyping phase.

Finally, farmers also expressed their desire to obtain a confirmation of assessment that can be shared with their peers or other interested stakeholders. As a result, a certification of completion is now available for download once farmers have completed a flock assessment. Despite interest from farmers to share their results, data accuracy and verification concerns meant that no performance data is displayed on the certificate.

3.4. Post-Launch Discovery

Five farmers were interviewed 3–4 months after the launch of Lite NEST as part of the secondary discovery phase. Interview invitations were sent to 13 farmers who had registered an interest in being interviewed during the survey and had not been previously interviewed during the prototyping phase. Only five interviews involving seven farmers were possible due to the busy schedules of farmers during summer months and farmers also having to deal with an outbreak of avian influenza in the summer of 2022. A total of 257 min of audio was transcribed using the professional transcription service Rev. Using the open coding process described in the methods, 61 concepts in 10 distinct categories were identified. Only one person was responsible for the open coding process and, as a result, no inter-coder reliability concerns were required to be addressed. Examples of the open coding process—from identification of phenomena to definition of categories—is provided in

Figure 9. A full list of categories and their constituent concepts identified as a result of this open coding process is provided in the

Supplementary File Section S3. A discussion of the key findings under each category is provided below.

3.4.1. Farmer Characteristics

These interviews were helpful in defining some characteristics among farmers that might prove useful in identifying effective methods to both further develop and promote NESTT in the future. An overall sense of inertia among the farmers interviewed was evident with respect to sustainability. In a way, this inertial state can be viewed as a positive—farmers were certainly not apathetic towards sustainability. It was clear the farmers interviewed either truly cared about the sustainability of egg production or at least acknowledged its importance to the future of egg farming in Canada. Some farmers viewed sustainability through the lens of personal responsibility towards the global climate crisis while others viewed it more as a ‘requirement’ for the survival of their business. Across the board, it was evident that the key to translating any form of interest in sustainability into action was advancing the ‘bottom-line’/economic argument for sustainability. Finally, the farmers interviewed also appeared to be people of strong convictions—from strong opinions on climate change to opinions on the performance of different housing systems—even if sometimes there was acknowledgement of evidence contradicting those convictions.

3.4.2. Motivations to Use NESTT

Farmers mentioned a variety of reasons as motivations to use NESTT. As mentioned previously, some referred to their personal responsibility in addressing climate change and considered using NESTT as the least they can do. Others highlighted using NESTT to potentially ease some of the difficulty associated with making real changes—one farmer mentioned how their desire to install solar panels remained just an idea for a very long time until they received a marketing cold call. Farmers mentioned using NESTT now with the aim of realizing some market benefits in the future from being early adopters. This motivating factor likely resulted from hearing about the positive experiences of farmers who were early, voluntary adopters of other on-farm programs in the Canadian egg industry. One farmer also mentioned that they were motivated to use NESTT in the hope of finding new, useful information in support of aspects such as effectively transitioning to a new housing system. Finally, one farmer also mentioned that they did not have any personal motivating reasons to use NESTT but were rather interested in it due to their awareness of consumer interest in sustainability and NESTT’s ability to support marginal gains that might improve the bottom-line.

3.4.3. About Their Peers

All of the farmers interviewed also discussed their peers when talking about the use of NESTT. Most mentioned that sustainability was likely not a major concern among other farmers they knew and said that there is very likely a subset of farmers who are never going to be engaged in sustainability-related initiatives unless it was mandatory like the Animal Care or Start Clean—Stay Clean (SC-SC) programs. One farmer mentioned that they would like to see a mandatory, NESTT-based, on-farm sustainability program launched but also specified that such a program will likely face serious opposition from some producers. Once again, the farmers interviewed highlighted the economic rationale—no producer will turn a blind eye to something that will positively impact their bottom-line. One farmer said that if NESTT enables farmers to view sustainability in monetary terms, although some farmers might ‘fake’ their interest in sustainability, this would still be a better outcome than those producers not being engaged in the sustainability discourse at all.

3.4.4. Barriers

With two of the five farmers interviewed not having completed an assessment in Lite NESTT they were asked to expand about the likely barriers for farmers using the tool. In addition to the barriers discussed as part of the survey, they mentioned other—mostly practical—issues faced by farmers. Interviewees expressed that the fear of failure can stop farmers from trying out NESTT voluntarily. One farmer mentioned a simple lack of awareness among producers about NESTT and that it would take some time for words to spread. Both farmers also mentioned that they had very little time to spare for something that is neither a mandatory requirement nor providing any direct monetary benefits. Farmers also mentioned that producers are already having to collect, maintain, and share so much data as part of other on-farm programs that they have very little appetite for more.

3.4.5. Improve Uptake

Alongside highlighting these issues, farmers also provided suggestions that can help NESTT overcome some of these barriers. Farmers suggested that EFC should promote NESTT as a tool for improving profitability to producers instead of a pure sustainability tool. They also suggested making users aware of data requirements before beginning an assessment. Most farmers insisted that finding common ground with both the Animal Care and SC-SC programs will help uptake by sharing the burden of using NESTT with mandatory programs that farmers have already bought into across the industry. As discussed previously, a mandatory on-farm sustainability program involving NESTT was also suggested.

3.4.6. Communications

Since several farmers mentioned a lack of effective communications about Lite NESTT and its launch, more detailed discussions on this topic were initiated during the interviews. Two farmers mentioned that they were not even aware of the tool’s launch until receiving invites for these interviews. Farmers suggested that press releases and articles about NESTT in industry magazines and websites will not be effective in reaching producers. Social media platforms were suggested as a potentially more effective way to reach farmers—especially younger farmers. More than one farmer mentioned that communications from provincial egg boards was likely to be effective due to the trust farmers have in provincial board members. Multiple farmers acknowledged that NESTT was discussed in recent provincial egg board annual general meetings (AGMs). Farmers also said they would encourage in-person communications about NESTT from EFC field inspectors who visit farms in-person and that such conversations can translate to more effective uptake. Most of the farmers interviewed acknowledged that they had not talked to other producers about NESTT but, having used it, were now more willing to champion the tool.

3.4.7. Data Collection Issues

One of the key issues highlighted by farmers from their experience of using Lite NESTT was data collection. All farmers agreed that most of the data asked for from farmers was available but required some effort to be gathered from different places. Farmers said searching for information made the process too long and sometimes forced them to stop and focus on other immediate tasks. Examples of data collection issues highlighted by farmers included needing to contact their feed providers for feed composition data and converting energy, feed, and water data to the required reference scale. On the other hand, farmers agreed that the data requirements were minimal, easy to understand, and likely to take much less time to input in the future once they are familiar with using the tool.

3.4.8. Representation of Farms

There were some important questions raised in the interviews about the representation of non-common farm characteristics. One was NESTT’s ability to recognize outlier farms that had unique production conditions (e.g., using experimental feed inputs) or had experienced random/irregular events (e.g., disease outbreak) during the reporting period. Another aspect highlighted was NESTT not covering other aspects of farm operations such as pullet rearing, feed milling, crops grown in outdoor areas of free-range systems, and even other livestock production on the farm. Finally, some farmers highlighted that flock management is predominantly carried out on a week-by-week basis and hence assessing sustainability impacts only at the end of the flock cycle provides limited value.

3.4.9. Additional Features

The farmers who had used Lite NESTT at least once suggested a wide range of features for addition in future versions of the tool. There was interest in being able to track from where inputs to their farm such as feed are sourced. Farmers felt that both the insights and resources section of Lite NESTT were too generic and not helpful in making immediate changes to their production conditions. Farmers were also interested in seeing environmental impacts such as carbon footprints presented in a simple and easily understandable way. They also wanted to see more benchmarks against which to compare their performance, including other countries such as the USA, other livestock products such as dairy and chickens, and housing systems other than their own. Finally, farmers also suggested enabling communication with other farmers or with sustainability experts in NESTT.

3.4.10. Economics

A common theme across the nine categories discussed so far was the economic rationale. There was enough discussion about economics during the interviews to classify it as a separate category. Farmers interviewed very often referred to profitability, efficient production, and ensuring that consumers continue to buy Canadian eggs in the future when asked to define what sustainability means for the industry. All farmers claimed that economics was the major driver of decisions on egg farms. For example, one farmer claimed that NESTT will have to present farmers with the long-term economic benefits of adopting greener technologies. Farmers also claimed that there is no visible economic or financial benefit to using NESTT, unlike the industry’s Animal Care or SC-SC programs. They suggested creating an incentive program for either using NESTT, or for eggs sold by farmers who have completed regular assessments in NESTT. One farmer suggested creating a marketing label called ‘NESTT eggs’. Another suggested that, if incentivized in some way, early users of NESTT might be more enthusiastic in championing the tool among their peers. Given the potential barriers to any incentive program involving NESTT, farmers suggested that NESTT should at least provide information for farmers on funding opportunities or government programs for sustainability improvements. Given the importance of the economic dimension according to farmers, considerable efforts should be committed going forward into developing an economic assessment model in NESTT, and researching the potential of direct and indirect economic benefits to promote uptake of the tool among farmers.

4. Discussion

While stakeholder involvement is a cornerstone of sustainability assessment methods, it has been largely overlooked in developing farm-level decision support tools (DSTs) [

10]. This study differs from the few existing cases of stakeholder-engaged DST design, particularly in its explicit use of participatory design.

Unlike prior studies that used “stakeholder involvement” [

12] or “a participatory approach” [

13], only Cerf et al. (2012) [

40] explicitly implemented participatory design in farm-level DSTs. However, Cerf et al.’s work focused on isolated production practices, whereas NESTT provides a holistic assessment of environmental performance based on life cycle thinking and assessment. As one of the first publicly documented applications of participatory design in farm sustainability assessment, this study advances the field by demonstrating an inclusive, iterative approach. Participatory design has several advantages to other traditional user-involved development methods. Participatory design considers end users as co-designers and not informants who are consulted but not involved in the decision-making process. Participatory design also ensures that users are involved throughout, and not just in the user-testing phase. This means that end users are collaborators in the development process, and not used just for validating the decisions made by external experts.

A key factor in participatory design is defining users and ensuring diversity. While identifying users was straightforward, the sampling strategy—non-probabilistic and based on recommendations from provincial egg board members—introduced limitations. The survey was sent to 70 farmers identified for their interest in sustainability, likely skewing results toward early adopters rather than representing the broader farming community. These early adopters, often opinion leaders, may facilitate NESTT’s diffusion but also highlight a challenge: bridging the gap between early adopters and the early majority, as described in the Everett Roger’s diffusion of innovation model [

42]. Future research should explore strategies to engage the wider farming population. This is important going forward to reduce self-selection bias as it can lead to a lack of focus on real concerns from the larger farmer population and result in flawed decision-making that hinders the widespread adoption of NESTT. Some potential strategies to engage with farmers at large—including those not interested in sustainability (laggards in the diffusion of innovation model)—are reframing the value proposition (present sustainability concerns as those associated with business concerns such as profitability, cost savings, and risks), acknowledging barriers to adoption and discussing them proactively, leverage trusted advocates and intermediaries to make the case, and adopt more in-person engagement strategies (for example using events such as industry expos where more farmers are likely to attend since the focus is not entirely on a single topic in which they are not very interested).

Despite this limitation, the participating farmers represented various provinces, farm sizes, and housing systems. The sample skewed younger (over 50% were under 40), with higher representation from larger farms (over 60% had 20,000+ birds) and non-conventional housing systems (compared to the national average of 43% in 2021). The answers provided by respondents for questions such as the important aspects of sustainability reinforce this characterization of the sampled farmers representing early adopters as defined in the diffusion of innovation model [

43]. Early adopters are often opinion leaders and trend-setters who seek to obtain competitive advantages by taking judicious risks and do not require much convincing to adopt innovations. There were several provincial egg board members and members of EFC’s young farmer program present in the list of 70 farmers provided by EFC and they are high profile and respected voices (hence potential champions for NESTT) in their respective provinces.

The participatory design approach was effective in refining NESTT. The exploration phase identified seven priority sustainability considerations, which remained unchanged throughout the process. The pre-launch discovery phase leveraged surveys over interviews for broader engagement, aligning with Rowe et al.’s [

43] emphasis on fairness and competency in stakeholder engagement. The prototyping phase focused on five key pillars—user-centeredness, data security, aesthetic appeal, accessibility, and simplicity—ensuring an intuitive tool for farmers with limited experience using digital platforms.

The survey revealed that most farmers had minimal experience with online tools. To avoid overwhelming them, NESTT’s first version was designed for gradual adoption. While farmers prioritized animal welfare and food safety in industry sustainability, these concerns were already addressed by other programs. Lite NESTT, therefore, focused on resource efficiency and productivity. Benchmarking was identified as the most critical feature, shaping the assessment scorecard’s design. Farmers could also track performance and access information on green technologies. Although they requested customized rankings for mitigation options, the complexity of integrating preference data meant this feature was deprioritized. Instead, the five key design pillars discussed earlier guided the prototyping phase.

The iterative development process led to Lite NESTT’s launch (

https://www.eggsustainability.ca/), followed by a post-launch discovery phase that refined future priorities. Despite the small sample size, farmer feedback proved invaluable, leading to two sets of enhancements: immediate improvements for Full NESTT and long-term innovations for NESTT 2.0.

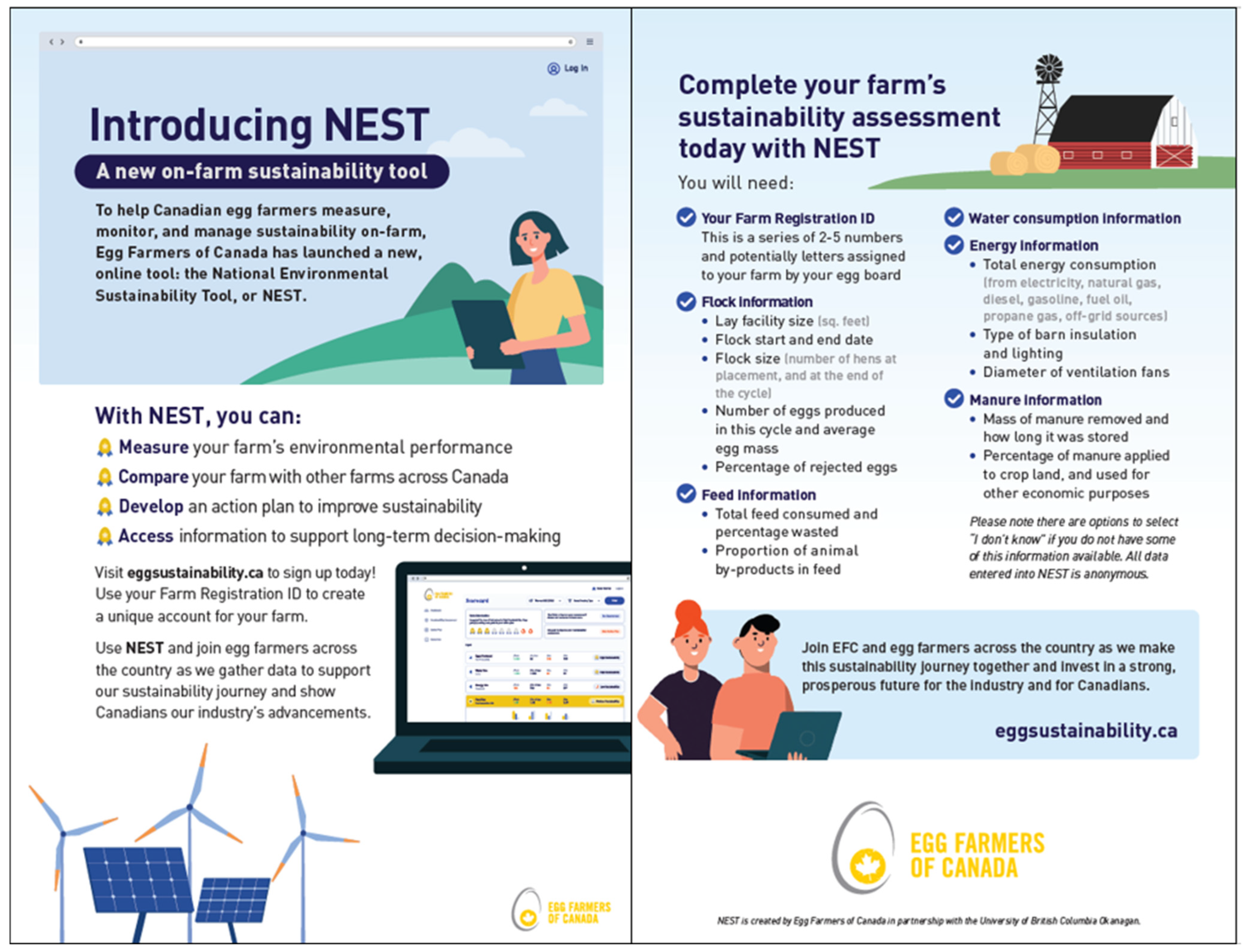

Key new features in Full NESTT include environmental impact calculations (e.g., carbon and energy footprints) and farm-specific green technology assessments. Based on farmer feedback, a data requirements checklist was added to the landing page, and input descriptions now clarify assessment categories. To improve awareness, EFC mailed postcards (

Figure 10) to all registered egg farmers and trained field inspectors to introduce NESTT during their annual farm visits. The resources section was also expanded to include government funding opportunities for green technologies.

Looking forward, NESTT 2.0 will incorporate techno-economic assessments, automated data integration with barn monitoring systems, expanded benchmarking capabilities, and enhanced feed formulation and pullet modules. Long-term strategies, such as linking NESTT with other on-farm programs and potential financial incentives, will require further industry collaboration.

Farmers’ request for more benchmarks will be addressed, potentially incorporating advanced methods like frontier analysis [

13]. Additional enhancements will refine feed formulation and pullet modules for more precise environmental impact estimates.

Strategic planning is required for broader initiatives such as a mandatory on-farm sustainability program, economic incentives for early adopters, and integration with other EFC programs. This post-launch discovery phase marks the first of many user engagements to guide NESTT’s evolution. Findings will inform EFC’s strategy for the next five years, ensuring NESTT supports the industry’s long-term sustainability goals.

5. Conclusions

Stakeholder involvement is crucial in developing sustainability assessment methods, yet is often lacking in farm-level tools. To address this gap, a participatory design approach was used to develop the National Environmental Sustainability and Technology Tool (NESTT), an online, life cycle-based sustainability assessment and decision support tool for Canadian egg farmers. This ensures end users are integral to system development. A four-step process engaged Canadian egg farmers in NESTT’s creation: exploration, pre-launch discovery, prototyping, and post-launch discovery. The first three steps informed Lite NESTT, while the fourth identified improvements for future versions.

The exploration phase included farm visits and consultations with provincial egg board members, identifying seven priority considerations—hen productivity, feed and water use, energy use, mortality, manure management, and spent hens—along with key indicators for Lite NESTT. The pre-launch discovery phase used surveys to gauge farmers’ views on sustainability, desired features, and usability factors. Insights led to Lite NESTT’s focus on resource efficiency, benchmarking, and refining development priorities.

During the prototyping phase, farmers reviewed renderings and mock-ups, resulting in enhancements to user-centeredness, data security, aesthetics, accessibility, and simplicity. Finally, the post-launch discovery phase informed Full NESTT’s development, adding carbon footprint and other life cycle-based indicators, assessment of green technologies, funding information for sustainable technologies, and data input refinements. It also explored long-term strategies, including integration with other farm programs, economic assessments, and financial incentives for adoption.

By embedding participatory design in its development, NESTT ensures practical relevance, usability, and alignment with farmers’ needs. This approach not only enhances farm-level sustainability assessment but also sets a precedent for integrating stakeholder-driven innovation in decision support tools.