Abstract

Household bread and bakery product waste constitutes a growing issue in Algeria, with significant economic, environmental, and socio-cultural implications. This research is situated within the framework of sustainable food systems and responds to recent transformations in domestic food practices, driven by increased female labor force participation, time constraints, and the widespread availability of industrial bread, which have reshaped household food management and traditional home bread-making practices. The study aims to (1) review traditional Algerian breads, emphasizing their culinary, nutritional, and cultural significance; (2) examine household behaviors during the month of Ramadan in the city of Constantine, focusing on patterns of consumption, purchasing, waste generation, and strategies for reusing leftovers; and (3) assess the economic implications of these practices using the FUSIONS methodology and explore their contribution to household-level food sustainability. Methodologically, a cross-sectional exploratory survey was conducted among 100 married women, the majority of whom were middle-aged (62%; range: 27–71 years; mean age: 52.0 ± 10.21), well-educated (59% with a university degree), economically active (68%), and living in medium-sized households (63%). The findings reveal pronounced contrasts across bread categories. Industrial breads, particularly baguettes, are characterized by high daily purchase frequencies (4.16 ± 1.31 units/day) and the highest waste rates (12.67%), largely attributable to over-purchasing (92%) and low perceived value associated with subsidized prices, with convenience (100%) remaining the primary factor explaining their dominance. In contrast, traditional breads exhibit minimal waste levels (1.63%) despite frequent purchase (3.85 ± 0.70 loaves/day), reflecting more conscious food management shaped by strong cultural attachment, higher perceived value, and dietary preferences (100%). Modern bakery products, along with confections and pastries, the latter representing of 58% of total household food purchases, comprise a substantial share of food expenditure during Ramadan (2.16 ± 0.46 loaves/day and 12.07 and 7.28 ± 2.50 units/day, respectively), while generating relatively low levels of food waste (5.69%, 4.19%, and 0%, respectively). This suggests that higher prices and symbolic value encourage more careful purchasing behaviors and conscious consumption. Freezing leftovers (63%) emerges as the most commonly adopted waste-reduction strategy. Overall, this work provides original quantitative evidence at the household level on bread and bakery product waste in Algeria. It highlights the key socio-economic, cultural, and behavioral drivers underlying waste generation and proposes actionable recommendations to promote more sustainable food practices, in line with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 12 on responsible consumption and production.

1. Introduction

Conscious food consumption involves making responsible choices that reduce waste, prioritize local and traditional products, and consider economic, social, and environmental dimensions [1,2,3,4].

Household consumption has been identified as a critical leverage point for improving food system sustainability, particularly in the context of global food loss and waste [5,6].

In Mediterranean and North African countries, consumption patterns are strongly shaped by cultural traditions, religious practices, and social norms, which influence both food use and waste generation [7,8].

In Algeria, traditional foods based on durum wheat, breads (Matlouha, Rakhsis, Khobz Eddar, etc.), and fermented cereal products occupy a central place in daily diets and ritual practices, particularly during Ramadan [1,2,3,4].

Algerian cuisine is renowned for its diversity, with traditional breads serving not only as dietary staples but also as cultural markers that reflect regional identity, social cohesion, and religious symbolism [1,9,10,11]. These breads are prepared using knowledge passed down through generations and often made from indigenous cereals such as wheat and barley, offering distinctive flavors, textures, and nutritional qualities [1,4,9,12,13,14].

Women play a key role in household bread-making, influencing purchasing decisions, preparation methods, portion sizes, storage practices, and the valorization of leftovers [15,16]. Research in Mediterranean and North African contexts highlights that women are central to household food security and waste prevention, particularly within traditional food systems [7,8,15,17].

However, socio-economic transformations, including modernization, urbanization, changes in family structure, and the increasing participation of women in the workforce, have contributed to a progressive decline in home-based bread preparation [2,15,18,19,20,21,22].

As a result, industrially produced bakery products, particularly French-style baguettes, now dominate urban markets [2,15,18,19,20,21,22]. While convenient, these products have altered traditional consumption habits and weakened the intergenerational transmission of bread-making knowledge [15]. This shift aligns with broader nutrition transitions in developing countries, where traditional foods are increasingly replaced by standardized industrial products [19,21,22].

Bread is highly perishable and, globally, one of the main contributors to household food waste [5,7,23]. In Algeria, waste is exacerbated by subsidized prices, overbuying, and inadequate storage, leading to significant economic losses and environmental impacts [3,24,25,26]. Studies in Mediterranean countries show that bread waste is influenced by cultural norms, freshness expectations, and daily purchasing routines [7,8,27]. Despite its cultural centrality, empirical research on Algerian household bread waste remains limited, particularly during culturally and religiously significant periods such as Ramadan [3,26,28,29].

Ramadan presents a unique context for examining household consumption and waste. During this period, meal preparation becomes more elaborate, portion sizes increase, and food sharing intensifies, potentially leading to higher bread consumption and waste [26,28,29,30]. Religious occasions can amplify both the symbolic abundance of food and unintended waste [7,8,26,30].

This study offers a novel, integrated analysis of cultural, behavioral, and economic dimensions of bread consumption and waste at the household level during Ramadan in Constantine, northeastern Algeria. Its objectives are to: (1) review Algerian traditional breads and their culinary, nutritional, and cultural significance; (2) examine household behaviors related to Bread and bakery products purchasing, consumption, and waste during Ramadan; and (3) assess the economic implications of bread waste using the FUSIONS methodology [31]. The research is guided by three questions: (1) How do Ramadan-related cultural practices influence household bread consumption and waste in Algeria? (2) Which socio-demographic and economic factors drive household bread waste during Ramadan? (3) How can household behaviors inform strategies to promote conscious consumption and reduce bread waste?

This study contributes by providing quantitative household-level evidence on bread and bakery products consumption and waste in Constantine; demonstrating how Ramadan practices, together with women’s household management and preferences, shape consumption patterns and waste behavior; and highlighting key socio-cultural and behavioral drivers of household bread and bakery products waste, while offering practical recommendations to promote conscious consumption and minimize waste.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Traditional Breads in Algeria

2.1.1. History and Religious Aspects of Bread Making

Bread, a global staple, varies in form, composition, taste, preparation methods, countries of origin, and names, shaped by regional culture. In the Mediterranean Basin, wheat is often the main cereal used in bread production, while barley or a blend of both is also common [12,32,33].

Archaeological findings indicate that bread production appeared in Ancient Egypt as early as 10,000 BCE [34]. Frescoes in pharaohs’ tombs show the stages of bread making, including baking in conical Bedja molds (2686–2160 BCE), which were preheated, filled with dough, and surrounded with hot embers. Bread was also baked on heated stone slabs [13,35].

Different countries have distinct styles of bread preparation, whether unleavened or leavened. Natural leavening sponge is produced from residues in dough containers, dough saved from previous batches, or baker’s yeast from flour, water, and leaven. Sourdough fermentation is often preferred for its flavor and sensory advantages [13,32,33,36,37].

Historically, a dish called “Tharid” was prepared by soaking units of flatbread in a meat stock before the Islamic expansion into North Africa; bread is eaten either as a standalone meal or as an accompaniment [12,36,38].

Bread holds symbolic value in religious rituals: it represents life’s necessities in Islam and is a powerful symbol in Christianity, as expressed in “Give us this day our daily bread” [39]. Bread commands great respect—it is never thrown away, uneaten bits are picked up, and passersby place any found bread in a visible spot [12,40].

2.1.2. Breads Symbolism in Ramadan

In Algeria, bread holds a central and symbolic place in the daily diet; it is considered indispensable at every meal and even regarded as sacred [25,41]. Several studies confirm that bread and other bakery products are the most widely consumed food group in North Africa [7]. Bread retains both symbolic and nutritional importance, particularly during Ramadan, when consumption rises significantly due to religious and communal customs [6,26].

During the holy month of Ramadan, the evening fast is traditionally broken at sunset with dates and water, following the Sunnah. After performing the Maghrib prayer, families gather for Iftar, the main evening meal, where bread plays a pivotal role. It is typically served alongside traditional dishes such as Chorba Frik (a hearty soup made from crushed green wheat), Hmiss (a salad of grilled peppers, tomatoes, and garlic), and stews like Tadjine Kefta (meatballs simmered in a spiced tomato-based sauce), Tadjine Zitoun (chicken or lamb with olives and preserved lemon, traditionally cooked in an earthenware pot), and Chebah Essofra (a sweet specialty from Constantine made with finely ground almonds and red meat). These meals typically combine cereal-based foods, vegetables, and animal protein, reflecting customary dietary patterns during Ramadan and providing energy-dense foods after prolonged fasting hours [28].

2.1.3. Bread Types

- Flatbreads

Flatbread, known in Arabic as khebz or kesra (meaning fragment of something), is a common type of bread in Arab countries [14,36]. In Algeria, women produce several types of flatbreads (Figure A1). The best type of bread was made from durum wheat grown locally and baked with sourdough instead of baker’s yeast. Traditional ovens and utensils are still used for baking bread (Figure A2) today due to their practicality [1,32,37].

Aghroum n’tajin or Aγrum is the general word for breads in the Kabylia [12], also known as Kesra Khamira, Matlouha, Matlouh, Matloua, Makla [14,42]. Aghroum is made entirely from durum wheat flour. It is typically leavened with natural sourdough made from a two-day-fermented dough unit (ir’es-en temtount or Amtun), called also Ukfil [1]. It is shaped into discs that are 2 to 3 cm thick and 25–30 cm in diameter. It is baked first on one side and then on the other, on a special circular clay pot or metal griddle called Tajine, heated using a special fire oven called Tabuna (small stovetop). The bread is light and spongy, with a characteristic tenacity from semolina. To ensure even cooking, small holes should be made in the bread with the tip of a knife to allow gases to escape and prevent blisters from forming. If the outside edges of the bread are not fully cooked, they are placed directly in the fire for a few seconds to ensure complete and even cooking. The base of the Tajine has an uneven relief, often embossed with circular lines on the bottom, which insulates the dough from the hot surface and allows it to rise without burning [2,12,42]. An earthen oven called Taboon, Tannoor, or Tandoor can also be used. It has a dome-shaped, truncated cone design and is made from clay, with an opening at the top or bottom for stoking the fire. Traditionally, dried tree branches, tree trimmings, and wood chips are used as fuel in the Mzab and Saoura communities of the northern Saharan region (Ghardaïa), as well as in earth depressions among Tuareg groups in the southern Hoggar Mountains (Tamanrasset and Illizi provinces) [18,43]. These ovens have a cupola construction, with the base often dug out of the ground. They always have two openings, one at the base to maintain the ember fire and one at the top, which is fairly large, through which the flat loaves are placed into the oven. The loaves are positioned against the wall and must be removed before they fall from the wall into the embers [13,36,44].

Rakhsis is a flatbread made from wheat and/or barley and is less leavened and thinner (0.5 cm) than Mathloua. It is baked on both sides. It has a brown-yellow color, a firm crust, and a smooth surface. It contains oil that provides for a rich flavor and prevents the formation of blisters on its surface, as noted by Kezih et al. (2014) and Abecassis et al. (2012) [2,42]. In Kabylia, a similar bread containing oil is baked, but it is not leavened and is called Aghroum Aquran [45]. Rakhsis is served with both savory and sweet meals and is an essential accompaniment to soups, bell pepper salads, and also butter, milk, and buttermilk [2,44].

Khobz Eddar is a flatbread, which translates to “home breads” [14,46]. It is also known as Khobz Koucha (oven breads) and is shaped into a round form with a diameter of 35 cm and a thickness of 4 to 5 cm. Before baking, the dough is given a decorative touch (Figure A3), with various shapes such as scored patterns and braided shapes, to enhance its texture, flavor, and rise. Khobz Eddar is made from durum or common wheat semolina and differs from Kesra due to the inclusion of other ingredients like fat, eggs, milk, sesame, black seed, or aniseed, as well as the manufacturing process. It is cooked on one side in metal trays inside an oven, whether it is a household oven or a bakery oven. This bread has a crispy crust and a tender, delicious crumb [42,44,47]. It is often served alongside dishes such as Chorba Frick, and instead of using a spoon or fork, the dish is eaten with hand-cut breads [46,48].

Al-maghemoum bread is cooked between two metal pots over a wood flame that surrounds all of its sides [46].

Taguella, also known as Targuia or Taghella, is bread among the Tuareg people [9]. It is baked in hearth ash on the sides of an inverted metal pot heated over the fire [13] or on a metal plate suitable for baking thin sheets of dough placed on the fire [12]. It can also be baked in intensely hot sand covered with hot ashes [43]. The women of Saoura also use this method to cook unleavened Millia breads [1,9,13].

Khobz Al-Maqlah, which is inlaid with a seed or fennel. It is made from a mixture of white flour and durum wheat semolina, fermented for hours, and then fried in a pan with a little olive oil or vegetable oil to roast [46].

- B.

- Pancake-Like Flatbreads

Pancake-like flatbreads are made from fermented dough and have a pliable texture, a unique lightness, and a slightly spongy consistency [43].

Tighrifin is a pancake (word used from Kabylia); it is also known as Tibouâjajin, Baghrir, or Thoudfist in the Chaouïa dialect. It is also referred to as Korsa, Ghrayef or Ghrif in other regions of Algeria [12,42]. Tighrifin is made from semolina or a blend of semolina with common wheat, salt, eggs, sugar, and yeast. The dough is formed by adding water until a liquid suspension is achieved [2,42,47]. It is cooked on only one side on a Tajine Msarah (smooth base) or a platter under a lid. The cooking process involves using a ladle to spread an amount of the suspension in the Tajine. During cooking, many small cavities of one or two millimeters appear on the upper side, which are considered the most important criteria for product quality [42]. Tighrifin is often eaten sweet for breakfast with a mixture of butter and honey or powdered sugar, but it can also be enjoyed with jams and olive oil [12,42].

Bourjeje is a pancake from Kabylia made from flour, eggs, yeast, and salt. It consists of a thin layer of dough and is cooked on both sides. It can be served hot or cold, sweet or savory [43].

Msemmen is the general term used throughout many cities of Algeria for a traditional layered pancake. In Kabylia, it is called Timsemmnin; it is known as Lemsemmen, Soummam, Acebbaḍ, and Timsemdin, which have a square shape [9,10,45]. Msemmen is made from flour and can be cooked on a smooth Tajine or fried in oil. It is often served as an accompaniment to breakfast or afternoon tea. It can also be dried and crumbled to be enjoyed with milk or a hot sauce. In the Auras region (Batna, Khenchela, and Oum el Bouaghi), it is called Msemnettes, while in east of Algeria it is known as Semniyette and Mtawi, and in Beskra it is called Rougag [11,45].

- C.

- Sugar-Filled Cookies

There are various recipes for sugar-filled cookies, such as Chric and Zlabia, and they are made in different ways [2,42]. These cookies are often served with tea, coffee, or a cold drink as part of hospitality. They are also commonly given as gifts during family visits [36].

Chric is a pancake originally from Algeria (Constantine) [10]. It is typically a small ball, about hand-sized or smaller, with a round top and a flat bottom. Chric is made from semolina, sugar, milk, yeast, butter, orange blossom, and egg. It is then decorated with cardamom and sesame seeds [49].

Zlabia, also known as Zalbia, is a very popular sweet in all Arab countries. In Algeria, it is very appreciated in the eastern region.

It is made from fermented semolina dough. It is shaped into a round form or a helical shape resembling a twisted knot, and it comes in different sizes. Zlabia is deep-fried in a frying pan and then covered in sugar syrup with rose water. The texture of Zlabia is chewy, possibly due to the outer layer of crystallized sugar. Zlabia is incredibly popular and can be found in shops and markets, especially during the month of Ramadan. It is often distributed as a vow or charity in mosques due to its high demand during this month [2,9,36].

Tahboult, Mouskoutchou, Meskoutch, Meskouta, or Mchaoucha, Tahboult, also known as Mouskoutchou, Meskoutch, Meskouta, or Mchaoucha, is a light and spongy cake. It is most prepared from Kabyles and Chaouïa and is made with eggs, oil, milk, flour, and yeast. It is often flavored with lemon or orange and is commonly topped with honey or jam. Tahboult is typically enjoyed with tea or milk [9,10,50].

Lesfeng, also known as tih’bulin or Lexfaf, is a leavened, light cake similar to a donut. It hails from Kabyles and is also called Lekhfef, Ftaïr, or Ftayer. Lesfeng is made with semolina and yeast, and then fried in oil until inflated. It is often sprinkled with sugar or dipped in honey, jam, or olive oil. It is typically served hot or warm, usually in the mid-afternoon, accompanied by coffee or milk [9,10,11,45,50]. In Constantine, Lesfeng is commonly sold outdoors and often served with juice.

Tamtunt refers to breads from Kabyles. They can be fried in oil (Tamtunt n zzit), giving them a pancake-like texture similar to Lesfeng. Alternatively, they can be baked in the oven, resulting in a brioche-like appearance as Swiss bread or French buns. Tamtunt is served with honey, jam, or olive oil and is typically accompanied by coffee or a mint herbal beverage [9,10,11].

- D.

- Bread-Based Meals

Traditional breads from Rakhsis, Matlouha, Tighrifin, and Lemsemmen can be used to prepare bread-based meals. These breads can be served as stuffed breads, similar to a sandwich, where they are split in half and filled with different preparations [12,48]. Alternatively, the preparation can be mixed with the dough of the bread before it is cooked. The bread can also be used as a main dish by mixing the bread crumbs with the preparation. Some examples of popular stuffed breads are Aghroum n’ tadount or Aghroum Vousoufer in Kabylia, known as Mhadjeb, or Mahdjouba in Algeria (Biskra); Aghroum Lahwal in Kabylia with various types of herbs; Makhtouma or Mkhalaa, also in Biskra with minced meat, peppers, tomatoes, and vegetables; and Mtabga in Biskra with tomatoes, red peppers, animal fats, and olive oil, known as Kesra Elchahma in the east of Algeria. These breads are typically consumed hot, immediately after they are made. Unleavened bread dough can also be used to prepare these bread meals [9,10,43]. The bread crumbs from Msemmen can be mixed with milk, Lben, and olive oil or butter to prepare Acewwaḍ or Tacewwaṭ in Kabylia, or with sugar and nuts to prepare Mchelwech in Algeria (Constantine) as sweet dishes. The bread crumbs can also be used to prepare the savory dish Chakhchoukha, originally from Biskra, by reducing them to fine crumbs and covering them with a very spicy red sauce (Merga) in which mutton or fat and various vegetables are cooked. In Kabylia, this dish is known as Timegzert [9,10,11,12,13]. Taguella breads are used to prepare a dish by mixing the crumbs with soups made from tomatoes and vegetables, meats, peppers, or broth, sometimes flavored with wild fennel, or served with liquid butter and eaten with spoons [1,13,20].

- E.

- Similarities between Algerian Breads and Those Around the World

Khobz Eddar is similar to Italian Focaccia, Ethiopian Himbasha, and Turkish flatbreads [51]. Khobz Al-Maqlah is similar to Moroccan breads called Batbout. Tighrifin is similar to Baghrir in Morocco and Tunisia; Lahouh in Yemen and southern Saudi Arabia; Injera or Taita, which are spongy breads made from teff, wheat, barley, and sorghum flours; and Lachuchua, which is slightly softer and more flexible and is found in Ethiopia and Eritrea [13,14,42,52]. Bourjeje resembles leavened French crêpes and a Sudanese pancake called Gorraasa. Lemsemmen is similar to the Moroccan Melaoui [48]. Chrik is similar to bread sandwich spreads found around the world, such as Pistolet in Belgium, Massa Sovada in Portugal, and Panfocaccia in Italy. Zlabia is similar to Chebakia in Morocco, Mkharek in Tunisia, wameh (a round-shaped donut) in Middle Eastern countries, Lokma in Turkey, Luqmat Al-Qadi in Iraq, Jordan, Syria, Palestine, Lebanon, Meshabek in Egypt, Zoolbia in Iran, Jalebi in India, Jeri in Nepal, Zilebi in the Maldives, Selroti (made from fermented rice) in India and Nepal, and Luchi in Bangladesh. Lesfeng is similar to the fried breads in the Navajo Nation, and tamtunt n zzit is similar to the Bammy breads in Jamaica [53].

3. A Cross-Sectional Exploratory Survey on Bread and Bakery Product Waste in Households

3.1. Materials and Methods

3.1.1. Survey Design and Data Collection

A cross-sectional exploratory survey was conducted in Constantine, northeastern Algeria, during Ramadan 2024 (12 March–5 April); Constantine is renowned for its bread-making skills and its cuisine is regarded among the finest in the Maghreb [10,44].

A purposive non-probability sampling strategy was employed to recruit 100 adult married women. Exclusion criteria included women who were illiterate or unable to complete the questionnaire independently, ensuring sample homogeneity and response consistency. Participants were selected for their responsibility in household food management, given their central role in meal planning, food purchasing, and consumption practices, in line with the study’s objective. This non-probability sampling approach was considered appropriate given the exploratory nature of the study and time constraints.

Data were collected using the structured, self-administered questionnaire. The questionnaires were distributed to women at local mosques after the Taraweeh, the nightly prayer during Ramadan, a time when respondents were more available and attentive. Brief guidance was provided to minimize biases commonly associated with self-reported household food waste surveys, and to ensure accurate understanding of the questions. All respondents were informed about the purpose of the study and assured of the confidentiality of their responses, and reminded that participation was entirely voluntary.

3.1.2. Questionnaire Description

The study was conducted using an original questionnaire. It developed based on a review of literature on consumer food behavior and household food management [3,4,6,7,8,12,13,16,17,25,26,33,34,36,38,39,40,54,55,56,57,58,59]. It was pilot-tested on 10 respondents for clarity and relevance.

The final questionnaire comprised 38 questions in three sections: socio-demographic information, consumption and purchasing behavior and waste behavior.

To improve recall accuracy, the questionnaire included detailed quantity prompts, clearly defined reference periods (e.g., per day, per week), and explanations of measurement units (e.g., pieces, loaves). Self-reported prices were cross-validated with direct field observations conducted concurrently to minimize potential underestimation of bread waste.

- Socio-demographics information: This section included four questions on age, education level, occupation, and household size. Its purpose was to profile respondents and examine the influence of socio-demographic factors on their food management.

- Consumption and purchasing behaviors of breads and bakery products: This section was structured into five subsections, comprising a total of 21 questions: (A) Bread baguettes: this subsection included six questions exploring the consumption frequency, type, and price of baguettes, as well as the purchase frequency and quantity purchased; (B) Other breads: this part included of six questions related to the consumption of other traditional breads, whether homemade or purchased, covering purchase frequency, quantity consumed, and price; (C) Confections: this subsection contained four questions focusing on the types of confections consumed, their price, purchase frequency, and quantity; (D) Pastries: this section comprised four questions about types of pastries consumed, price, purchase frequency, and quantity; Factors influencing purchase decisions: this subsection consisted of one multiple-choice question, allowing respondents to select all relevant factors influencing their choice of bakery products.

- Waste behavior of breads and bakery products: This section included 13 questions and was divided into three subsections: (A) Breads: this subsection, consisting of five questions, examined whether respondents discard bread, the types, and quantities of bread wasted, comparison with non-Ramadan periods, and causes of waste; (B) Confections and pastries: This subsection included three questions investigating the weekly quantities of confections and pastries wasted, as well as respondents’ perceived level of waste compared to bread; (C) Waste reduction practices: this section included two questions about respondents’ willingness to adopt waste-reduction measures and their methods for managing leftover bread.

3.1.3. Evaluating the Economic Value of Purchases and Waste

- Data Conversion: Categorical frequencies reported by respondents (daily, several times per week, weekly, and less than once per week) were converted into numerical equivalents of 7, 3.5, 1, and 0.5 days per week, respectively. This conversion method is widely employed in studies [16,55] to estimate representative averages and enable more robust cross-household comparisons. To ensure comparability across respondents, reported purchase quantities were standardized by converting weights (kg) into unit equivalents. Conversion coefficients were derived from laboratory-based mass measurements of representative confections products, obtained as commercial samples from a local shop in Constantine, Algeria, using a KERN laboratory electronic balance (model 440-35N, KERN & SOHN GmbH, Balingen, Germany). The measurement protocol followed standardized procedures previously validated in similar studies [5,31,60,61].

Weighted mean calculation: The estimation of both the average purchasing frequency and the average number of units per household was conducted using a weighted mean approach [56]. This method integrates categorical data by factoring in the relative proportion of respondents within each category. Each response category (e.g., purchase frequency or quantity range) was assigned a numerical value representing its corresponding level (e.g., number of purchases per week or number of units purchased). The relative proportion of respondents within each category was used as the weighting coefficient. The weighted mean ( was calculated using the following equation:

where = weighted mean; = number of terms; = weights applied to x values (proportion of respondents in category ); and = data values assigned to that category. Weights were normalized such that ( = 1).

- Quantification of household and national bread and bakery product purchases and waste: Household-level (HH) estimates were derived from reported purchasing and waste frequencies, unit prices, and quantities acquired. These values were standardized to a monthly basis, assuming an average of 4.29 weeks per month. For national-level (N) extrapolations, HH estimates were scaled to the total number of Algerian households (≈8 million) [62,63]. A data FUSIONS approach [31] was used to generate indicative projections. The resulting N values are presented for illustrative purposes only, providing approximate, order-of-magnitude estimates rather than statistically representative national estimates. The calculations were performed as follows:

3.1.4. Statistical Analysis

All collected data were systematically coded and organized in an Excel spreadsheet. Analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics summarized the dataset, with continuous variables expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD) and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages.

The normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Non-normally distributed data were analyzed with non-parametric tests: Kruskal–Wallis tests for group comparisons, followed by pairwise Mann–Whitney U tests with Bonferroni correction. Repeated categorical measures were analyzed using Cochran’s Q tests, with Bonferroni-adjusted McNemar post hoc comparisons. Associations between ordinal or continuous variables were examined using Spearman’s rank correlation. For nominal categorical variables, chi-square tests were conducted, complemented by Cramér’s V to estimate effect sizes. Linear-by-linear association tests were applied to detect trends across ordered categories, and chi-square goodness-of-fit tests evaluated deviations from expected distributions. All statistical tests were two-tailed, with significance set at p < 0.05.

3.2. Results and Discussion

3.2.1. Socio-Demographics Information

The sample consisted of a total of 100 adult women from Algeria. Regarding age groups, participants in the survey ranged from 27 to 71 years, with a mean age of 52.0 ± 10.21 years (Table 1). Approximately 62% of participants were between 40 and 60 years old, reflecting a predominance of middle-aged women in the sample. Concerning the level of education, 59% of respondents held a university degree, indicating a highly educated sample, 33% had completed secondary education, and 8% had primary education only. In terms of employment status, 68% of respondents were employed, 24% were housewives, and 8% were retired, highlighting the relatively high participation of working women. The distribution of household size revealed that most households were medium-sized (63%; 4–6 members), followed by small (28%; 1–3 members) and large households (9%; 7–10 members).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents (n = 100).

The pattern demonstrates the coexistence of nuclear and extended family structures prevalent in contemporary Algerian society.

The socio-demographic profile of respondents reflects the ongoing socio-economic transition observed across Mediterranean and North African countries, marked by rising female labor force participation, higher educational attainment, and evolving household structures. Comparable patterns have been documented in Tunisia, Morocco, Italy, and Spain, where women continue to serve as primary household food managers while simultaneously facing increasing time constraints due to employment. These structural shifts are increasingly recognized as critical determinants of food purchasing behaviors, the adoption of convenience products, and the generation of household food waste, particularly for perishable staple items such as bread [6,7,16,17,55,64].

3.2.2. Consumption, Purchasing Behavior and Economic Value of Breads and Bakery Products

- ▪

- Bread Baguettes

Baguette is the most popular and widely consumed in the Algerian diet [24]. However, only 19% of respondents maintained their usual French baguette consumption during the fasting month, compared with 81% prior to Ramadan.

The observed decline in baguette consumption during Ramadan reflects a reconfiguration of bread choice rather than reduced cultural importance. Baguettes remain central to meals for their practicality, even as households diversify toward other breads during religious periods. Similar findings have been reported across North African and broader Muslim-majority contexts [3,7,28,29].

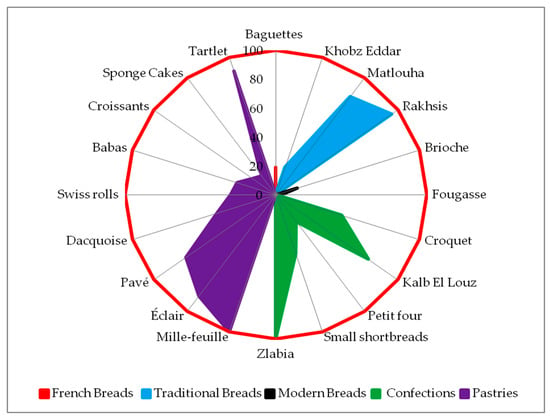

A McNemar test revealed a significant decline in French baguette consumption during Ramadan, χ2(1, N = 100) = 97.01, p < 0.001 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Consumption rates across product categories during Ramadan. Baguettes: French breads; traditional breads: Rakhsis, a thin traditional flatbread, less leavened, made from wheat or barley; Matlouha, a slightly thicker flatbread than Rakhsis; Khobz Eddar, a round bread, often decorated before baking, also known as Khobz Koucha “oven breads” (Figure A1). Modern breads: brioche, soft, slightly sweet bread enriched with butter and eggs; Fougasse, decorative bread similar to Focaccia. Confections: Zlabia, a sweet deep-fried semolina dessert soaked in sugar syrup; Kalb El Louz, a semolina-almond dessert baked and soaked in honey; Croquet, a small crispy confectionery; Petit Four, a small sweet filled confectionery; Small Shortbreads, small sweet buttery confectionery. Pastries: Mille-Feuille, a layered puff pastry with cream; Eclair, a choux pastry filled with cream and glazed; Pavé, a square or rectangular pastry, often layered or creamy; Dacquoise, a light almond meringue biscuit, used in desserts; Swiss Rolls, a rolled sponge cake, filled with cream or jam; Babas, a syrup-soaked cake, sometimes with cream; Croissants, a butter-leavened puff pastry in crescent shape; Sponge Cakes, soft, airy cakes made from eggs and flour; Tartlets, small tarts with cream, fruits, or chocolate [5,12,26,27,30,36].

Survey results revealed clear patterns in bread consumption during Ramadan. Respondents purchased various types of baguettes, which differ in their composition and preparation methods [12,13,14]. Standard baguettes (made from wheat flour) were purchased by 36% of respondents. Improved baguettes (prepared with improved flour and oil) and semolina baguettes (made from semolina and oil) were the most popular, selected by all respondents (100%). Garnished baguettes (standard baguettes topped with sesame or Nigella seeds) were chosen by 44% of respondents, while barley baguettes (made from barley) were purchased by only 3%.

The addition of fats, such as oil, in these breads enhances their sensory appeal by improving crumb softness, extensibility, and flavor, while also prolonging shelf life by slowing starch retrogradation [4,33,65,66].

Results indicated that baguettes were purchased at prices ranging from 10 to 30 Algerian Dinar (DZD), with a mean price of 12.80 ± 4.68 DZD per unit (Table 2).

Table 2.

Household-level purchase and waste values, with national-level extrapolation, for breads and bakery products.

A Cochran’s Q test confirmed significant differences in purchasing frequency among baguette types (Q = 274.646, df = 3, p < 0.001).

Post hoc McNemar tests with Bonferroni correction (α = 0.005) revealed significant differences in purchasing behavior among baguette types. Semolina and improved baguettes were purchased significantly more frequently than standard and barley types (χ2 = 62.016–95.010, df = 1, p < 0.001) and also more frequently than garnished baguettes (χ2 = 54.018, df = 1, p < 0.001). Garnished baguettes, in turn, were purchased significantly more frequently than barley baguettes (χ2 = 39.024, df = 1, p < 0.001), while standard baguettes also differed significantly from barley baguettes (χ2 = 26.256, df = 1, p < 0.001).

These findings highlight a strong consumer preference for enriched and semolina-based baguettes, reflecting both taste adaptation during Ramadan and the high productivity of Algeria’s bakery sector, which produces over 48 million baguettes daily [25].

In terms of frequency and quantity, all respondents purchased baguettes daily (7 days per week), averaging 4.16 ± 1.31 units per day. A significant difference was found between households buying 3–5 baguettes (75%) and those buying more than 5 (25%) (χ2 = 25.00, df = 1, p < 0.001).

These results align with observations from Mediterranean and Middle Eastern countries, where white or refined wheat breads dominate due to convenience, subsidies, and familiarity [7,24,25].

Table 2 presents detailed household-level data on bread purchases, along with national extrapolations, including weekly and monthly quantities and corresponding expenditures.

- ▪

- Other Breads

Algerians ingest bread in its whole form [24]. Survey results revealed a clear shift from industrial to traditional bread consumption during Ramadan. Traditional breads such as Rakhsis (95%) and Matlouha (84%) were overwhelmingly preferred over Khobz Eddar (20%) and modern varieties such as brioche (15%) and Fougasse (4%). This preference pattern was confirmed statistically. Cochran’s Q test confirmed significant differences in consumption frequency (Q = 241.378, p < 0.001). Post hoc McNemar tests with Bonferroni adjustment (α = 0.005) indicated that Rakhsis and Matlouha were consumed significantly more frequently than Khobz Eddar (χ2 = 64.42 and χ2 = 42.22, respectively; p < 0.001), brioche (χ2 = 78.01 and χ2 = 46.71, df = 1; p < 0.001, respectively), and Fougasse (χ2 = 89.01 and χ2 = 78.01, df = 1; p < 0.001, respectively). No significant difference was observed between the two traditional breads (p = 0.027) or between the two modern breads (p = 0.019).

Fluctuations in the quality of subsidized breads, particularly during periods of high demand such as Ramadan, combined with intermittent bakery operations and the presence of numerous informal distribution channels, appear to encourage consumers to diversify their purchases toward other bread types. Consumers increasingly favor traditional breads and other alternatives that provide greater consistency, superior sensory appeal, and recognized cultural value. These purchasing behaviors are further reinforced by taste preferences and entrenched culinary traditions, which guide choices beyond mere availability or price considerations [4,7,24,25,67].

Furthermore, enriched or semolina-based breads gain popularity during festive occasions but are more prone to waste when they are abundant and inexpensive, as documented in Algeria, Tunisia, Morocco, and Egypt [7,24,25].

Traditional breads were also more frequently prepared at home: Rakhsis was prepared by 45% of respondents, Matlouha by 27%, and Khobz Eddar by 10%, while none reported preparing brioche or Fougasse at home—it was exclusively purchased.

A Cochran’s Q test confirmed significant differences in home preparation (Q = 28.719, p < 0.001). Post hoc McNemar tests with Bonferroni adjustment (α = 0.0167) showed that Rakhsis was prepared significantly more often than Matlouha (χ2 = 6.021, df = 1, p = 0.014) and Khobz Eddar (χ2 = 23.592, df = 1, p < 0.001). Matlouha was also prepared more frequently than Khobz Eddar (χ2 = 8.258, df = 1, p = 0.004).

These findings indicate that traditional breads, particularly Rakhsis and Matlouha, retain strong cultural and symbolic significance during Ramadan. They continue to anchor Iftar meals, reflecting a culinary heritage deeply aligned with religious customs that emphasize sharing and authenticity [3].

Although less frequently consumed and prepared, Khobz Eddar retains symbolic significance. Its limited home preparation likely reflects practical constraints rather than diminished cultural value, as it is a time-consuming, multi-step bread requiring numerous ingredients [4].

In contrast, simpler breads, such as Rakhsis, are preferred when preparation time is limited or in response to climatic conditions, as lighter breads are easier to prepare and consume in warmer temperatures [2].

In North Africa and the Mediterranean, traditional bread in countries such as Morocco, Turkey, Iran, and southern Italy combines nutritional and social value, promoting careful preparation, portion control, and reduced waste, with cultural attachment acting as a key protective factor against food loss [3,7,66,68].

Traditional artisanal breads were priced between 60 and 150 DZD (mean: 85.50 ± 25.26 DZD/unit), whereas modern breads ranged from 30 to 50 DZD (mean: 31.10 ± 4.48 DZD/unit)

Price distributions were non-normal (Kolmogorov–Smirnov, p < 0.05), and Kruskal–Wallis tests revealed significant differences among categories (χ2(2) = 274.608, p < 0.001). Post hoc Mann–Whitney U tests with Bonferroni correction (α = 0.0167) confirmed that traditional breads were significantly more expensive than both modern breads and baguettes (U = 0.000, p < 0.001), while modern breads were also significantly pricier than baguettes (U = 188, p < 0.001).

These results confirm a clear price hierarchy: subsidized baguettes remain the most affordable, modern breads occupy a mid-range, and traditional artisanal breads command premium prices due to their higher production costs and craftsmanship. Their pricing is further shaped by smaller production scales and the use of locally sourced ingredients [8,24].

Spearman’s rank correlation showed no significant association between price and quantity purchased for baguettes (ρ = −0.182, p = 0.700) or modern breads (ρ = 0.032, p = 0.975), but a significant negative correlation for traditional breads (ρ = −0.426, p < 0.001) indicates higher price sensitivity. This pattern reflects value-driven consumption aligned with conscious consumption principles, where consumers reduce purchases of traditional breads as prices rise. Studies in Italy and Spain similarly report an inverse relationship between price and quantity purchased, highlighting the influence of economic valuation and craftsmanship on conscious consumption [24,56,58].

Baguettes and modern breads remain largely unaffected, appearing relatively price-inelastic due to their subsidized prices and their role as staple foods in the household diet [24], making them more prone to waste and highlighting the need for targeted educational interventions.

All respondents reported purchasing traditional breads (Rakhsis, Matlouha, Khobz Eddar) with an average of 3.85 ± 0.70 loaves/day, while modern breads (brioche, Fougasse) averaged 2.16 ± 0.46 loaves/day; with a purchase frequency of several times per week (3.5 days per week).

Detailed weekly and monthly household-level purchase data, along with national extrapolations for traditional and modern breads are presented in Table 2.

- ▪

- Confections and Pastries

In addition to bread, confections and pastries play a central role in Ramadan evenings. Whether traditional or modern in origin, these products have become integral to social gatherings over coffee or tea among family and friends [28,29].

Among confections, Zlabia was unanimously appreciated by respondents (100%), reflecting its strong cultural and symbolic significance during the holy month. Kalb El Louz (a semolina-based dessert enriched with ground almonds, sugar, and orange blossom water, baked, soaked in honey, and cut into rectangular portions) was preferred by 76% of participants.

Other confections included Croquet (appreciated for its crisp texture and golden crust) (46%), Small Shortbreads (known for their rich, buttery crumble) (43%), and Petit Four (consisting of small filled pastries) (23%).

Regarding pastries, the French Mille-feuille was consumed by all respondents (100%), followed by Tartlets (small open pastries commonly filled with chocolate, lemon curd, or strawberry) (90%) and Éclairs (elongated choux pastries filled with cream and topped with a glossy chocolate glaze) (87%).

Other varieties included Pavé (dense chocolate squares sometimes flavored with citrus and almonds) (74%), Dacquoise (a meringue-based layered cake filled with buttercream and nuts) (41%), Swiss Rolls (30%), Babas (27%), Croissants (19%), and Sponge Cakes (16%).

Price analysis showed that confections ranged from 200 to 800 DZD/kg (mean: 581.50 ± 182.11 DZD/kg), whereas pastries averaged 181.75 ± 258.68 DZD/unit (range: 15–1000 DZD).

Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests indicated non-normal distributions for both categories (D = 0.225 and D = 0.210, p < 0.05). Therefore, a Mann–Whitney U test revealed that confections were significantly more expensive than pastries (U = 1082, p < 0.001), reflecting their premium artisanal nature and higher ingredient value [59].

Confections were purchased several times per week (3.5 days per week). Among respondents, 57% reported buying 0.5 kg (9 units), 37% purchased 1 kg (18 units), and 6% adjusted the purchased quantity according to household size, with an average of 4.67 ± 1.25 units per person per day.

By aggregating all responses, the mean number of confection units purchased per household was estimated using a weighted mean formula:

This weighted calculation considers the proportion of households within each purchasing category to produce a representative average. Conversion from weight (kg) to units was based on direct measurements of five representative confection products: Croquet (31.22 ± 2.94 g), Kalb El Louz (132.60 ± 15.92 g), Petit Four (19.70 ± 5.63 g), Shortbreads (27.43 ± 2.50 g), and Zlabia (67.90 ± 6.57 g). Thirty samples of each product were measured following a standardized procedure validated by previous research [5,31,60,61].

Pastries were purchased at an average of 7.28 ± 2.5 units per day. They were also frequently bought: 11% of households reported daily purchases (7 days per week), 77% purchased them several times per week (3.5 days per week), 9% weekly (1 day per week), and 3% less than once per week (0.5 times per week). The overall mean purchasing frequency was determined using a weighted average formula.

Average frequency = (0.11 × 7) + (0.77 × 3.5) + (0.09 × 1) + (0.03 × 0.5) = 3.57 days/week/household

Confections and pastries represented a major component of Ramadan purchases, with all households (100%) reporting increased demand, which is consistent with previous studies showing a 37–50% rise in food expenditures during Ramadan [30].

Price did not significantly influence purchases of confections (r = −0.111, p = 0.272) or pastries (r = −0.046, p = 0.648), underscoring their symbolic and cultural significance over economic rationality as reported by Capone et al. (2016); Hassan and Low (2024) and Secondi et al. (2015) [7,26,69].

The persistent demand for certain breads, particularly traditional or symbolic varieties, reflects dietary preferences shaped by taste, cultural norms, and ritual significance [3,7,8,24]. Despite higher prices or limited preparation time, consumers continue to purchase these breads, prioritizing cultural and symbolic value over cost, which can lead to food waste as an unintended byproduct [3,7,24,58]. At the same time, limited household budgets require families to make deliberate choices, such as buying smaller quantities of traditional breads, combining traditional and modern types, or prioritizing subsidized breads, thereby balancing cultural aspirations with economic realities [3,7,24,58].

For confections and pastries, household purchases indicate conscious consumption, reflecting careful planning to satisfy festive expectations while also reconciling traditional values with financial limitations.

Weekly and monthly household-level purchase data, along with national extrapolations, are presented in Table 2.

3.2.3. Factors Influencing Purchase Decisions

Survey results identified multiple factors influencing bread and bakery purchases during Ramadan. Variety-seeking, dietary preferences, convenience, family habits, and traditions were cited by all respondents (100%). Freshness (89%) and taste/flavor (77%) were also key attributes, whereas price (44%), household size (20%), and portability (12%) were less influential.

A Cochran’s Q test confirmed significant differences among these factors (Q = 550.827, p < 0.001). Post hoc McNemar tests with Bonferroni adjustment (α = 0.005) showed that freshness (χ2 = 37.96, p < 0.001) and taste/flavor (χ2 = 18.62, p < 0.001) were significantly more cited than price, household size and portability (all p < 0.001).

These results confirm that sensory and quality-related attributes, particularly freshness and taste, outweigh economic considerations, which is consistent with previous findings, including studies on gluten-free breads [57,67,70].

However, a chi-square test showed a strong association between household size and price sensitivity (χ2(2, N = 100) = 28.687, p < 0.001; Cramer’s V = 0.536).

This result indicates that larger households tend to prioritize price more strongly as a result of budget constraints that limit flexibility in bakery product choice. This behavior may reflect conscious consumption, whereby households deliberately balance the desire to fulfill cultural and dietary expectations with practical budget limitations [3,7,8,24].

3.2.4. Waste Behavior and Economic Value of Breads and Bakery Products

- ▪

- Breads

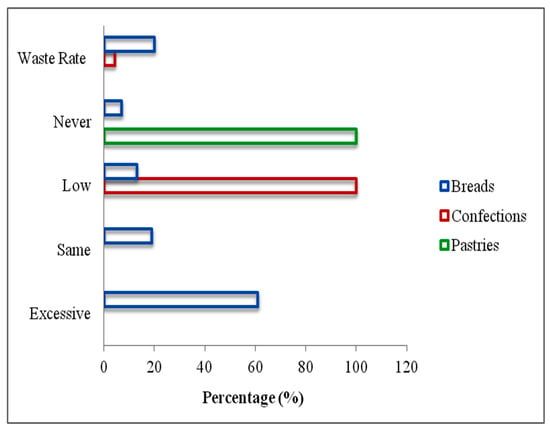

Household data reveal that, on average, households discarded 4.34 ± 2.02 loaves per week, predominantly baguettes (85%; 3.69 units). Modern breads accounted for 10% of total waste (0.43 units), while traditional breads represented about 5% (0.22 units), with notable variations in waste levels according to respondents (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Waste levels and rates of breads, confections, and pastries during Ramadan.

Weekly and monthly household-level waste data, along with national extrapolations, are summarized in Table 2.

The chi-square goodness-of-fit test showed a significant deviation from a uniform distribution (χ2 = 68.720, df = 3, p < 0.001), indicating that bread waste-related perceptions were unevenly distributed.

Baguettes accounted for the largest rate of bread waste (12.67%), reflecting their low perceived value and the tendency toward over-purchasing among households as reported by Capone et al. (2016) and Chenafi and Ghebouli (2024) [7,23]. The higher waste rate of French-style baguettes underscores the need for conscious consumption strategies and proactive measures to reduce waste. In addition, bread waste contributes significantly to environmental impacts through greenhouse gas emissions and the inefficient use of natural resources, including land, water, and energy, across the entire food supply chain. The disposal of wasted bread results in avoidable CO2-equivalent emissions and methane production during decomposition, particularly when landfilled, thereby exacerbating climate change and environmental degradation. Moreover, high levels of bread waste increase the demand for wheat production and imports, intensifying environmental pressures associated with agricultural inputs, long-distance transportation, and global supply chains. These combined impacts highlight the environmental urgency of reducing bread waste, limiting unnecessary wheat imports, and promoting more sustainable consumption patterns and waste-reduction strategies [3,5,6,24,25,26,27,31,37].

In comparison, modern breads showed a moderate loss rate (5.69%), while traditional breads had minimal losses (1.63%).

These findings align with previous studies [7,24], which reported up to 120 million baguettes discarded during Ramadan in Algeria and neighboring Mediterranean Arab countries such as Tunisia, Morocco, and Egypt (approximately 288 million DZD in losses). Other research conducted in Algeria [3] estimated 13 million, likely due to methodological differences between retail- and household-level analyses. The lower waste rate of traditional breads underscores their enduring cultural and economic importance in North African contexts [7,66]. This reflects conscious consumption, as households favor traditional breads for their cultural value, quality, and efficient resource use, while subsidized baguettes, perceived as low-cost, were more readily discarded [56,71].

Globally, conscious consumption remains limited in Algerian households during Ramadan, exacerbated by bread subsidies and cultural consumption patterns, underscoring the need for effective motivations to mitigate bread waste in Algeria.

The main causes of bread waste were:

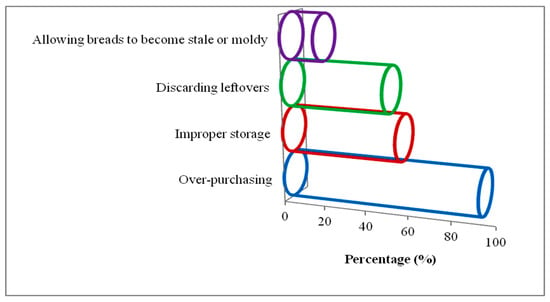

Over-purchasing (Figure 3) was by far the most frequently reported cause (92% of respondents). This behavior was particularly evident during Ramadan, when large quantities of homemade bread and subsidized baguettes lead to uneaten leftovers, as documented in several studies on Algerian and Mediterranean food practices [1,3,4,7,9,26].

Figure 3.

Factors contributing to bread waste during Ramadan.

- Although household size did not show a significant effect (χ2 = 2.52, df = 2, p = 0.284), larger families (≥4 members) tended to report this behavior more frequently. This may result from greater difficulties in meal planning and managing perishable foods, especially during Ramadan. Similar patterns have been observed in other Mediterranean and Arab contexts: Capone et al. (2016) [7] found that household size was a key driver of bread waste across 400 households surveyed in Algeria, Tunisia, and Lebanon, while Chenafi and Ghebouli (2024) [23], in a case study of 120 families in Sétif (Algeria), also linked family size and over-purchasing during Ramadan. Likewise, Hassan and Low (2024) [26] reported comparable results in Malaysia, where impulsive bulk-buying during Ramadan significantly increased food waste at the household level.

- Improper Storage was cited by 54% of respondents as a major cause of bread spoilage. This behavior was significantly associated with age (χ2 = 65.786, df = 5, p < 0.001; Cramér’s V = 0.811), with younger individuals more likely to report this behavior. A linear-by-linear association confirmed that storage habits improved with age (χ2 = 11.06, p = 0.001), suggesting that experience and familiarity with food preservation increase over time. These results align with previous studies showing that younger consumers often lack practical food preservation skills [56,72].

- Discarding Leftover bread was identified by 48% of respondents, and was significantly associated with employment status (χ2 = 8.520, df = 2, p = 0.014; Cramér’s V = 0.292), with employed individuals more likely to discard leftovers, potentially due to time constraints that limit meal planning and opportunities for food reuse. Similar patterns have been observed elsewhere, where busy lifestyles and employment responsibilities limit the time available for meal preparation, encouraging convenience-oriented behaviors such as bulk purchasing and less structured meal planning, which contribute to increased food waste. For example, Jabs et al. (2007) [16] reported that employed mothers in the United States often adopt time-saving strategies that increase food waste, with comparable patterns observed by Parizeau et al. (2015) [55] in Canada and Principato et al. (2015); Secondi et al. (2015) [56,69] in Italy. A broader review Schanes et al. (2018) [6] and Stancu et al. (2016) [71] across multiple European countries confirmed that such time constraints and lifestyle pressures are consistently associated with higher levels of household food waste.

- Allowing Bread to Become Stale or Moldy was reported by 16% of respondents. Bread staling, caused by starch retrogradation, reduces its sensory quality even under humid conditions and often leads to premature disposal [65,66,73]. This rate is lower than that observed in European studies, where approximately 40% of Belgian and Polish consumers discard bread due to firmness [27,74]. This behavior was decreased significantly with higher age (χ2 = 55.102, df = 5, p < 0.001; Cramér’s V = 0.784) and education (χ2 = 29.369, df = 2, p < 0.001; Cramér’s V = 0.542), indicating that older and more educated individuals were therefore less likely to waste bread due to spoilage. Previous studies have shown that both age and education promote sustainability awareness and proactive food management [17,54,56,72]. Moreover, cultural attachment to traditional breads, coupled with their limited household production (homemade breads are typically made in smaller quantities and consumed soon after baking), may help reduce their waste compared with subsidized varieties, which are mass-produced, more abundant, and affordable [7,66].

A Cochran’s Q test confirmed significant differences among the reported causes of bread waste (Q = 109.312, df = 3, p < 0.001). Post hoc McNemar tests with Bonferroni adjustment (α = 0.0083) revealed that over-purchasing occurred significantly more often than any other cause, namely improper storage (χ2 = 25.352, df = 1, p < 0.001), discarding leftovers (χ2 = 35.558, df = 1, p < 0.001), and allowing bread to become stale or moldy (χ2 = 70.312, df = 1, p < 0.001). Additionally, discarding leftovers was significantly more frequent than allowing bread to become stale or moldy (χ2 = 20.021, df = 1, p < 0.001). A correlation was also observed between poor storage practices and bread spoilage (χ2 = 12.116, df = 1, p < 0.001; Φ = 0.348).

By comparing the causes of bread waste, over-purchasing was identified as the main factor. Over-purchasing, driven by food abundance and the low perceived cost of bread, is the primary driver of bread waste during Ramadan. This result aligns with prior research showing that inexpensive or easily accessible foods tend to be undervalued and discarded more readily [56,75]. Similarly, a regional study across Mediterranean Arab countries (Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt, and Lebanon) reported that 88% of Algerian respondents experienced higher food waste during Ramadan, mainly due to excessive purchasing and abundant meal preparation [7,8].

- ▪

- Confections and Pastries

Households reported no waste for pastries, while confections showed only minimal waste (4.19%), likely reflecting their higher perceived value and price. In contrast, bread is often undervalued and more prone to disposal [56,71,76].

Weekly and monthly household-level waste data, along with national extrapolations, are presented in Table 2.

Survey results revealed a unanimous willingness among all respondents to reduce bread waste through responsible consumption habits. Preparedness to reduce waste was:

- 5.

- Freezing leftover bread: The most commonly adopted strategy was freezing leftover bread, reported by 63% of participants. This finding is consistent with previous studies [71,77], which identified freezing as a practical and effective household-level waste reduction method. Similarly, studies [78,79] demonstrated that refrigeration or freezing preserves bread’s texture and sensory quality, significantly extending its shelf life compared to room-temperature storage.

- 6.

- Planned purchasing: Additionally, 22% of participants reported purchasing only the necessary quantity of bread, reflecting increased awareness of food waste issues during Ramadan. This behavior supports previous findings [68], emphasizing planned purchasing as a key preventive strategy for household food waste. A chi-square test (χ2 = 340.464, df = 12, p < 0.001) revealed a statistically significant association between planned purchasing and age, with a strong effect size (Cramér’s V = 0.753). Although no significant association was found between planned purchasing and household size (χ2 = 1.395, df = 2, p = 0.498), descriptive statistics indicated that smaller households (1–3 members) were more likely to adopt planned purchasing (28.6%) compared to larger ones (4–6 members: 20.6%; 7–10 members: 11.1%).

- 7.

- Reuse of stale bread: Furthermore, 15% of respondents reported reusing stale bread in traditional recipes and encouraging this practice within their households. This observation aligns with the findings of Principato et al. (2015) [56], who noted that leftover reuse is deeply embedded in Arab food cultures. However, its limited adoption in the present study may be attributed to the predominance of employed women (68%) in the sample, as time constraints could hinder such practices. The chi-square analysis (χ2 = 442.157, df = 6, p < 0.001; Cramér’s V = 0.858) confirmed a significant relationship between employment status and bread reuse, indicating that employed women were less likely to engage in this practice.

By comparing bread preservation strategies, freezing was identified as the primary method.

A Cochran’s Q test (Q = 55.260, p < 0.001) revealed significant differences among the three waste-reduction strategies. Post hoc McNemar tests with Bonferroni correction (α = 0.017) showed that freezing was significantly more common than both planned purchasing and reuse (p < 0.001 for both), while no significant difference was observed between planned purchasing and reuse (p = 0.324).

These results reinforce prior findings that freezing represents one of the most accessible and effective strategies to reduce bread waste, particularly in modern lifestyles constrained by time and convenience [71,77].

4. Conclusions

This study examined consumption behaviors and food waste of breads and bakery products during Ramadan in Algeria, based on data collected from 100 adult women.

The results reveal a strong attachment to the cultural and sensory value of traditional breads, confections, and pastries, whereas subsidized baguettes, although central to the diet, are more likely to be wasted due to their low perceived cost and over-purchasing, which remains the primary driver of bread waste.

Notably, households demonstrated a willingness to reduce waste through practices such as freezing leftover bread. Consumer preferences were primarily driven by freshness and taste, and to a lesser extent by price, except for traditional breads, which exhibited greater price sensitivity.

Correlation and statistical analyses confirmed that consumption and waste behaviors were not uniformly distributed but depended on socio-demographic and professional factors, including age, employment status, and household size. The cultural significance of traditional breads acted as a protective factor against waste, whereas subsidized and modern breads remained more vulnerable to disposal.

The main contribution of this research lies in providing quantitative evidence on household-level purchasing, consumption, and food waste in Algeria, illustrating how traditions, cultural norms, and household economics influence food practices. Practically, the study emphasizes the need for targeted educational and behavioral strategies, such as promoting conscious consumption, adopting effective storage methods, and planning purchases, to reduce bread waste and optimize the use of food resources.

Nonetheless, the study has some limitations, including the relatively small sample size; however, it was considered sufficient to generate preliminary insights and assess household bread-wasting behaviors within the studied population. No formal sample size calculation was performed, as the study was exploratory in nature, consistent with established methodological guidance for exploratory and qualitative research [80,81]. In addition, the focus on a specific socio-demographic profile may limit the generalizability of the findings to the wider Algerian population. Future research should employ longitudinal, multi-regional designs with objective measurements, such as waste audits and digital tracking, to more accurately assess household bread waste and its underlying drivers. In conclusion, the findings of this study indicate that bread waste is closely linked to both behavioral and cultural factors. Household strategies such as conscious consumption, careful storage, and improved purchase planning can significantly reduce waste, suggesting that practical interventions and awareness campaigns could be highly effective. At the same time, supporting traditional bread-making practices and encouraging the reuse of leftovers highlight the importance of integrating waste reduction with cultural preservation. This dual approach not only addresses food loss but also reinforces culturally meaningful practices, which may increase household willingness to adopt sustainable behaviors.

In a rapidly changing socio-economic environment, combining the preservation of cultural heritage with waste reduction can enhance food security and contribute to achieving Sustainable Development Goal 12, which promotes responsible consumption and production.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, F.Z.B., L.D., A.B., M.B. and R.B.; Data curation, F.Z.B.; formal analysis and investigation, F.Z.B. and L.D.; data processing, F.Z.B.; Resources and Software, F.Z.B.; Validation, F.Z.B., M.B. and L.D., writing—original draft preparation, F.Z.B.; writing—revision and editing, F.Z.B., A.B., L.D. and M.B.; discussion, F.Z.B. and M.B.; English style editing and language correction, F.Z.B., L.D., M.B., A.B. and R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to Ethics committee review not required for descriptive, non-clinical research under Algerian law (Law n° 18-11, 2 July 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Traditional baked goods in Algeria. Flatbreads: (a) Matlouh; (b) Rakhsis; (c) Khobz Eddar; (d) Taguella; (e) Khobz Al-maqlah. Pancakes: (f) Tighrifin; (g) Timsemdin. Sugar-filled cookies: (h) Chric; (i) Zlabia; (j) Tahboult; (k) Lesfeng; (l) Tamtunt as bread; (m) Tamtunt as cake. Bread-based meals: (n) Aghroum n’ tadount from Matlouh; (o) Aghroum Vousoufer from Rakhsis; (p) Mhadjeb; (q) Msemmen; (r) Aghroum Lahwal; (s) Mkhalaa or Makhtouma; (t) Maghlouga from Tighrifin; (u) Kesra Elchahma or Mtabga; (v) Mchelwech; (w) Chakhchoukha; (x) Timegzert. Source: Authors’ personal collection; Bread-based meals Reprinted from [9,10,44].

Figure A2.

Traditional utensils, and methods for bread baking in Algeria. Types of pot (Tajine): (a) Clay Embosser Tajine; (b) Metal Embosser Tajine; (c) Frying Tajine; (d) Clay Smouth Tajine; (e) Metal Smouth Tajine; (f) Flat Tajine. Methods for baking: (g) Inverted metal pot heated over the fire; (h) Sand covered with hot ashes; (i) Tajine under a lid; (j) Small stovetop “Tabuna”; (k) Earthen oven “Tannoor”; (l) Earthen oven in an earth depression. Source: Authors’ personal collection.

Figure A3.

Different decorative shapes of the Khobz Eddar dough. Source: Authors’ personal collection.

References

- Benveniste, E.; Camps, G.; Morel, J.-P.; Hanoteau, G.; Letourneux, A.; Nouschi, A.; Fery, R.; Demoulin, F.; Chamla, M.-C.; Louis, A.; et al. Alimentation. In Encyclopédie Berbère; Presses Universitaires de France: Paris, France, 1986; pp. 472–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kezih, R.; Bekhouche, F.; Merazka, A. Some traditional Algerian products from durum wheat. Afr. J. Food Sci. 2014, 8, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beddiar, A.; Bendafer, K.; Khirat, H. Bread Consumption: Eating Behavior and Food Waste Status. Master’s Thesis, University 8 Mai 1945 Guelma, Guelma, Algeria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bourekoua, H.; Djeghim, F.; Benatallah, L.; Zidoune, M.N.; Wójtowicz, A.; Łysiak, G.; Różyło, R. Durum wheat bread: Flow diagram and quality characteristics of traditional Algerian bread Khobz Eddar. Acta Agrophysica 2017, 24, 405–417. Available online: http://www.acta-agrophysica.org/pdf-105063-35945 (accessed on 19 May 2024).

- FAO. Global Food Losses and Food Waste: Extent, Causes and Prevention; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schanes, K.; Dobernig, K.; Gözet, B. Food waste matters: A systematic review of household food waste practices and policy recommendations. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 978–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capone, R.; Bilali, H.E.; Debs, P.; Bottalico, F.; Cardone, G.; Berjan, S.; Elmenofi, G.A.G.; Abouabdillah, A.; Charbel, L.; Arous, S.A.; et al. Bread and bakery products waste in selected Mediterranean Arab countries. Am. J. Food Nutr. 2016, 4, 40–50. [Google Scholar]

- Nasreddine, L.; Hwalla, N.; Sibai, A.; Hamzé, M.; Parent-Massin, D. Food consumption patterns in an adult urban population in Beirut, Lebanon. Public Health Nutr. 2006, 9, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chibane, H.; Chibane, S. Les Plats Traditionnels de la Région “At Yaɛla” de Bouira. Master’s Thesis, Université Mouloud Mammeri de Tizi-Ouzou, Tizi-Ouzou, Algérie, 2016. Available online: https://dspace.ummto.dz/handle/ummto/4226 (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Slimani, K. Enhancement of Culinary Heritage: Ritual of Collective Festivities and Social and Culinary Differentiation. Master’s Thesis, Université Mouloud Mammeri, Tizi-Ouzou, Algeria, 2017. 144 p. [Google Scholar]

- Aït Ferroukh, F.; Messaoudi, S. Cuisine Kabyle; Edisud: Marseille, France, 2004; 159 p; ISBN 978-2744903922. [Google Scholar]

- Balfet, H. Bread in some regions of the Mediterranean area: A contribution to the study of eating habits. In Gastronomy: The Anthropology of Food Habits; Arnott, M.L., Ed.; Mouton Publishers: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1975; pp. 305–314. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, D. Bread in Africa. In Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures, 2nd ed.; Selin, H., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 963–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqualone, A. Traditional flat breads spread from the Fertile Crescent: Production process and history of baking systems. J. Ethn. Foods 2018, 5, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belahsen, R.; Naciri, K.; Ibrahimi, A.E. Food security and women’s roles in Moroccan Berber (Amazigh) society today. Matern. Child Nutr. 2017, 13, e12562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabs, J.; Devine, C.M.; Bisogni, C.A.; Farrell, T.J.; Jastran, M.; Wethington, E. Trying to find the quickest way: Employed mothers’ constructions of time for food. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2007, 39, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fami, H.S.; Aramyan, L.; Sijtsema, S.J.; Alambaigi, A. Determinants of household food waste behavior in Tehran City: A structural equation model. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 143, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auzias, D.; Labourdette, J.-P. Le Petit Futé Algérie 2011–2012, 5th ed.; Nouvelles Éditions de l’Université: Paris, France, 2011; ISBN 9782746925755. [Google Scholar]

- Popkin, B.M.; Adair, L.S.; Ng, S.W. Global nutrition transition and the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutr. Rev. 2012, 70, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemache, L.; Kehal, F.; Namoune, H.; Chaalal, M.; Gagaoua, M. Couscous: Ethnic making and consumption patterns in the Northeast of Algeria. J. Ethn. Foods 2018, 5, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerasekara, P.C.; Withanachchi, C.R.; Ginigaddara, G.A.S.; Ploeger, A. Nutrition transition and traditional food cultural changes in Sri Lanka during colonization and post-colonization. Foods 2018, 7, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sproesser, G.; Ruby, M.B.; Arbit, N.; Akotia, C.S.; Alvarenga, M.D.S.; Bhangaokar, R.; Furumitsu, I.; Hu, X.; Imada, S.; Kaptan, G.; et al. Understanding traditional and modern eating: The TEP10 framework. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenafi, K.; Ghebouli, A. Reducing food waste in bread consumption as a means to achieve food security: A case study of the State of Sétif. J. Dev. Res. Stud. 2024, 11, 504–516. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchafaa, B. Subsidizing bread in Algeria? Yes, but…. Rev. d’Écon. Stat. Appliquée 2018, 15, 83–89. Available online: https://asjp.cerist.dz/en/article/52333 (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Hocine, M.; Sebbache, L. La ressource alimentaire pain et ses déchets à l’aune de l’intelligence territoriale par « économie sociale et circulaire»: Cas d’El-Harrach dans la banlieue est Algéroise. Rev. Econ. Gest. 2018, 2, 114–123. Available online: https://www.asjp.cerist.dz/en/article/77860 (accessed on 13 June 2024).

- Hassan, S.H.; Low, E.C. Spur of the moment: The unintended consequences of excessive food purchases and food waste during Ramadan. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 2732–2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Boer, J.; Kobel, P.; den Boer, E.; Obersteiner, G. Food waste quantities and composition in Polish households. Waste Manag. Res. 2023, 41, 1318–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidoud, A.; Franco, L.; Terrón, M.P.; Elahcene, O.; Rodríguez, A.B. Food intake assessment before and during Ramadan in northern Algeria students. Nutr. Hosp. 2025, 05683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belfakira, C.; Hindi, Z.; Lafram, A.; Bikri, S.; Benayad, A.; El Bilali, H.; Gjedsted Bügel, S.; Średnicka Tober, D.; Pugliese, P. Household food waste in Morocco: An exploratory survey in the province of Kenitra. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, I.; Chamlal, H.; Jamal, S.E.; Elayachi, M.; Belahsen, R. Food expenditure and food consumption before and during Ramadan in Moroccan households. J. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stenmarck, Å.; Jensen, C.; Quested, T.; Moates, G. Estimates of European Food Waste Levels; FUSIONS Project: Stockholm, Sweden, 2016; Available online: https://www.eu-fusions.org (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Kamal-Eldin, A. Fermented cereal and legume products. In Fermentation: Chemical and Functional Properties of Food Components; Mehta, B.M., Kamal-Eldin, A., Iwanski, R.Z., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012; pp. 223–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvel, R.; Wirtz, R.L. The Taste of Bread; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamang, J.P.; Cotter, P.D.; Endo, A.; Han, N.S.; Kort, R.; Liu, S.Q.; Mayo, B.; Westerik, N.; Hutkins, R. Fermented foods in a global age: East meets West. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 184–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tifraouat, A.; Ouhal, I. Bread-Making Test with Incorporation of “Mech-Degla” Date Flour. Master’s Thesis, Université M’hamed Bougara, Boumerdès, Algeria, 2016. 136 p. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khusaibi, M. Arab traditional foods: Preparation, processing and nutrition. In Traditional Foods: Food Engineering Series; Al-Khusaibi, M., Al-Habsi, N., Rahman, M.S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 9–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingrao, C.; Licciardello, F.; Pecorino, B.; Muratore, G.; Zerbo, A.; Messineo, A. Energy and environmental assessment of a traditional durum-wheat bread. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 1494–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyot, J.-P. Fermented cereal products. In Fermented Foods and Beverages of the World; Tamang, J.P., Kailasapathy, K., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010; pp. 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boni, A.; Pasqualone, A.; Roma, R.; Acciani, C. Traditions, health and environment as breads purchase drivers: A choice experiment on high-quality artisanal Italian breads. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 221, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqualone, A. Italian durum wheat breads. In Bread Consumption and Health; Pedrosa Silva Clerici, M.T., Ed.; Nova Bio-Medical: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 57–79. [Google Scholar]

- Valavanidis, A. Bread, Oldest Man-Made Staple Food in Human Diet. 2018. Available online: http://www.chem-tox-ecotox.org/ScientificReviews (accessed on 27 June 2024).

- Abecassis, J.; Cuq, B.; Boggini, G.; Namoune, H. Other traditional durum-derived products. In Durum Wheat; Sissons, M., Carcea, M., Abecassis, J., Marchylo, B., Eds.; AACC International: St. Paul, MN, USA; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 177–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddadou, M.A. Dictionnaire des Racines Berbères Communes: Suivi d’un Index Français–Berbère des Termes Relevés; Haut Commissariat à l’Amazighité: Alger, Algeria, 2006; 309 p; ISBN 978-9961-789-98-8. [Google Scholar]

- Cheriet, G. Study of the Cake: Different Types, Recipes and Method of Production. Master’s Thesis, Université Mentouri, Constantine, Algeria, 2000. 99 p. [Google Scholar]

- Dallet, J.-M. Dictionnaire Kabyle–Français; Dictionnaire Français–Kabyle: Parler des at Mangellat; SELAF: Paris, France, 1982; 1052 p. [Google Scholar]

- Bourouina, F. Traditional bread returns to the Algerian table in Ramadan. Al-Riyadh 2013. Available online: http://www.alriyadh.com/855637 (accessed on 19 May 2024).

- Dagher, S.M. Traditional Foods in the Near East; Food and Nutrition Bulletin; United Nations University Press: Tokyo, Japan, 1991; 161 p. [Google Scholar]