Abstract

This study presents an integrated Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment (LCSA) of the Natural gas-to-methanol (NGTM) and methanol-to-gasoline (MTG) pathways using Aspen HYSYS process modeling, Environmental Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), Social Life Cycle Assessment (SLCA), and Life Cycle Costing (LCC). The results reveal significant variability in sustainability performance across process units. The DME and MTG Reactors Section generates the highest direct greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions at 0.86 million tons CO2-eq, representing 54.9% of total global warming potential, while the Compression Section consumes 2717.5 TJ/year of energy, making it the dominant source of electricity-related indirect emissions. Distillation and Purification withdraws 31,100 Mm3/year of water—approximately 99% of total demand—yet delivers 86.6% of the overall economic surplus despite high operating costs. Social impacts concentrate in the Methanol Reactor Looping and DME and MTG Reactors Sections, with human health burdens of 305.79 and 804.22 DALYs, respectively, due to catalyst handling and high-pressure operations. Sensitivity results show that methanol purity rises from 0.9993 to 0.9994 with increasing methane content, while gasoline output decreases from 3780 to 3520 kg/h as natural gas flow increases. The findings provide process-level evidence to support sustainable development of natural gas-based fuel conversion industries, aligning with Qatar National Vision 2030 objectives for industrial diversification and lower-carbon energy systems.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Methanol and gasoline are two of the most important fuels used in global transportation and industrial applications, each characterized by unique production pathways, performance attributes, and environmental impacts [1]. Methanol (with the chemical formula CH3OH), historically known as “wood alcohol,” evolved from early wood distillation processes to high-pressure catalytic synthesis in the 20th century, marking its large-scale industrial adoption. Today, methanol can be produced from a diverse range of feedstocks—including natural gas, coal, biomass, municipal waste, and captured CO2—positioning it as a flexible and increasingly strategic energy carrier within the context of global decarbonization [2,3].

Methanol’s high octane rating (100–110) and clean-burning characteristics offer advantages for internal combustion engines, although its lower energy density relative to gasoline requires higher volumetric consumption [4]. When produced from renewable resources, methanol can reduce life cycle CO2 emissions by up to 95% and significantly reduce NOx and SOx emissions [5]. In contrast, gasoline remains the world’s dominant transportation fuel due to its high energy density, mature infrastructure, and global availability; however, gasoline combustion accounts for substantial CO2, PM, NOx, and hydrocarbon emissions, contributing heavily to climate change and urban air quality degradation [6,7,8]. Table 1 summarizes key comparative characteristics of methanol and gasoline.

Table 1.

Comparative characteristics of methanol and conventional gasoline as transportation fuels.

Methanol ranks among the top globally traded chemicals due to its role in producing formaldehyde, acetic acid, MTBE, adhesives, paints, resins, plastics, silicones, and other industrial products [9,10]. In addition to its chemical applications, methanol is increasingly used in transportation, marine engines, industrial heating, hydrogen production via steam reforming, and emerging methanol-to-olefin (MTO) pathways [11,12]. Methanol can also serve as a precursor for producing synthetic gasoline via the MTG process, enabling cleaner gasoline with reduced contents of sulfur and aromatics [13,14].

Given the worldwide push toward carbon neutrality—with more than 120 nations announcing net-zero strategies by 2050–2060—methanol’s role as a cleaner alternative fuel continues to expand, especially in markets such as China, Europe, and the Middle East [15,16].

1.2. NGTM and MTG Supply Chains

Natural gas (NG) remains the dominant feedstock for methanol production, particularly in regions such as Qatar, where it is abundantly available. The NGTM pathway involves steam reforming, methanol synthesis, purification, and storage. Methanol can subsequently be converted to gasoline via the MTG process, which produces high-quality hydrocarbons suitable for spark-ignition engines [17,18,19]. This integrated NGTM–MTG chain represents an important route to producing cleaner synthetic gasoline that meets stringent environmental regulations.

Global demand for gasoline remains extremely high—exceeding 4.8 billion liters per day—and gasoline continues to dominate the transportation energy landscape, including passenger vehicles and piston-type aircrafts [20,21,22]. As conventional gasoline production becomes increasingly constrained by environmental regulations, synthetic gasoline derived from methanol offers a potentially lower-emission alternative.

1.3. Environmental, Social, and Economic Implications of Methanol

Environmentally, methanol results in significantly lower CO2, NOx, SOX, and PM emissions relative to gasoline [23]. However, methanol production releases CO2 and may generate environmental risks through potential groundwater contamination, toxicity, and atmospheric reactions that influence methane lifetimes [24,25]. Socially, methanol supports millions of jobs across the chemical industry but poses health hazards due to its toxicity and fire risks [26]. Economically, the methanol market exceeded USD 38 billion in 2023 and is expected to surpass USD 56 billion by 2033, driven by demand for chemicals, fuels, and clean energy applications [27].

Gasoline combustion contributes significantly to GHG emissions and air pollution, while its production generates wastewater, solid waste, and refinery emissions [28]. Occupational risks in gasoline production include exposure to VOCs and catastrophic industrial accidents [29]. Economically, gasoline remains central to global supply chains and significantly influences inflation, energy prices, and transportation costs [30].

1.4. Novelty of the Study, Problem Statement, and Research Structure

This research presents a comprehensive and innovative approach to evaluating the sustainability of the NGTM and MTG supply chains, addressing a critical gap in the existing literature. Although methanol has been widely studied for its combustion performance, fuel properties, and environmental advantages, very few studies offer a holistic sustainability assessment spanning the full NGTM–MTG conversion pathway. The novelty of this study lies in the integrated evaluation of NGTM–MTG sustainability performance using process-based modeling and life cycle sustainability principles. This methodology is strengthened through sensitivity and uncertainty analyses, providing a rigorous evaluation of model robustness and system variability. Furthermore, the research incorporates a Qatar-specific perspective, aligning with the nation’s strengths in NG, decarbonization goals, and long-term sustainability targets under Qatar National Vision 2030. The study also contributes to national capacity building by developing a reproducible model and dataset that can support industrial planning, policymaking, and academic training.

Despite the recognized benefits of methanol—including lower GHG emissions than gasoline, flexible feedstock options, and high-octane performance—its adoption remains constrained by several technical, economic, and safety-related challenges. These include increased emissions of formaldehyde and unburned methanol at high blending ratios, lower energy density that results in higher fuel consumption, corrosiveness that necessitates engine modifications, the high production cost of green methanol relative to fossil-based pathways, limitations in refueling infrastructure, and safety risks associated with methanol’s toxicity and nearly invisible flame. Moreover, the literature lacks an integrated sustainability assessment of the full NGTM–MTG supply chain, highlighting the need for a holistic evaluation that captures life cycle environmental impacts, economic viability, and social implications. Given Qatar’s dependence on NG and its commitment to sustainable energy development, such an assessment is essential to determine whether synthetic methanol and gasoline can provide cleaner and economically competitive alternatives to conventional fuels.

To clarify the contribution beyond prior LCSA applications, this study advances a sustainability assessment of gas-based energy systems through explicit methodological integration, expanded system boundaries, harmonized indicators, and region-specific decision relevance. Aspen HYSYS process simulation is tightly coupled with environmental LCA, SLCA, and LCC at the process section level, enabling the direct propagation of mass, energy, and utility balances into life cycle indicators rather than relying on aggregated or literature-averaged inventories. The system boundary explicitly captures the complete NGTM–MTG conversion chain, resolving sustainability trade-offs across reforming, synthesis, upgrading, compression, purification, and product finishing units at a level of granularity not addressed in earlier NGTM-, MTG-, or LNG-focused studies. A harmonized indicator framework is applied across all process sections to ensure consistent environmental, social, and economic benchmarking and normalized sustainability factor interpretation. The model is parameterized under operating conditions representative of Qatar’s gas-based, export-oriented energy system, allowing the results to directly inform national priorities related to energy diversification, water resource constraints driven by desalination dependence, and industrial decarbonization. Embedded sensitivity analysis further strengthens decision support by identifying technology-specific improvement levers aligned with Qatar National Vision 2030.

The structure of this research is designed to deliver a coherent and comprehensive sustainability evaluation of the NGTM and MTG pathways. Section 1 provides an overview of methanol and gasoline, outlines global and regional contexts, and introduces the study’s novelty, rationale, and research problem. Section 2 presents an extensive literature review covering NGTM and MTG process chains, global market trends, and existing sustainability assessment approaches while identifying critical research gaps. Section 3 details the methodological framework, including the LCSA approach, system boundaries, inventory analysis, Aspen HYSYS modeling, and sensitivity and uncertainty analyses. Section 4 discusses the results of the environmental, economic, and social assessments, offers comparative insights into the sustainability performance of the two pathways, and derives policy implications. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the key findings, addresses study limitations, and proposes future research directions to support the sustainable development of methanol and synthetic gasoline supply chains.

2. Literature Review

The global transition toward cleaner energy systems has revitalized interest in alternative fuels, synthetic hydrocarbons, and low-carbon chemical pathways. Among these, the NGTM and MTG conversion chains have gained renewed attention for their potential to support energy diversification while contributing to GHG reduction goals. Methanol serves as a versatile chemical platform and intermediate fuel, while MTG technology enables the production of gasoline-range hydrocarbons compatible with existing engine and refinery infrastructure. This section reviews the state of knowledge on NGTM and MTG supply chains, focusing on environmental implications, process technologies, techno-economic feasibility, and integrated sustainability frameworks—including environmental LCAs, SLCAs, and LCCs. Recent literature highlights major technological advancements, persistent challenges, and research gaps that guide the present study.

2.1. NGTM Process Chain

2.1.1. Feedstock Characteristics and Pre-Treatment

NG remains the dominant global feedstock for methanol production due to its high methane content, cleaner combustion profile, and mature supply infrastructure. Raw NG streams commonly contain carbon dioxide (CO2), hydrogen sulfide (H2S), mercaptans, moisture, nitrogen, and heavy hydrocarbons. These impurities reduce catalyst activity and contribute to equipment corrosion; therefore, NGTM facilities rely heavily on acid gas removal systems. Amine-based absorption processes remain industry standard, enabling removal of CO2 and sulfur species to parts-per-million levels required for downstream reforming operations [31].

Recent developments focus on improving energy efficiency in acid gas removal by optimizing solvent circulation rates, regeneration heat, and hybrid solvent blends. Studies show that optimizing pre-treatment steps can reduce total plant energy consumption by 6–10% and significantly decrease the CO2 footprint when integrated with carbon capture units [31,32]. Although cleaner than coal or petroleum-derived feedstocks, the NG supply chain—including extraction, processing, and transportation—can still produce substantial methane leakage, a key challenge for minimizing GHG impacts [33].

2.1.2. Reforming Pathways for Syngas Production

Methanol synthesis requires syngas with an optimal H2/CO ratio of approximately two. Traditional NGTM production relies on Steam Methane Reforming (SMR), an endothermic process operated at 700–1000 °C over nickel catalysts. SMR provides high conversion efficiencies but has considerable energy requirements and direct CO2 emissions. Ataya et al. [34] show that reforming contributes up to 60–70% of total GHG emissions in gas-to-liquid (GTL) plants.

To address these challenges, Autothermal Reforming (ATR) has gained momentum as a more energy-efficient alternative. ATR integrates partial oxidation (exothermic) with steam reforming (endothermic) in a single reactor, resulting in a near-thermoneutral process with lower fuel consumption. The literature indicates that ATR can reduce CO2 emissions by 10–20% compared to traditional SMR while improving the syngas yield and process controllability [35].

Partial Oxidation of Methane (POM) offers an additional pathway, particularly for decentralized or modular systems. POM requires no external heating and generates syngas through the exothermic oxidation of methane with limited oxygen. While its simplicity and lower CAPEX are advantageous, catalyst deactivation and lower H2/CO ratios limit large-scale adoption. Recent advancements in noble metal catalysts (Ru and Rh) have improved selectivity and stability, signaling emerging interest in POM-based NGTM applications [36].

2.1.3. Methanol Synthesis and Purification

Methanol synthesis occurs through catalytic reactions of CO and CO2 with hydrogen over Cu–Zn–Al catalysts at moderate temperature and pressure. Modern synthesis loops incorporate high-efficiency exchangers, quench reactors, and CO2 recycling to maximize yields. An environmental study demonstrates that improving syngas conversion efficiency reduces overall energy demand and improves carbon efficiency by up to 8% [37].

Crude methanol contains water, dissolved gases, and light hydrocarbons. Multistage distillation is used to achieve chemical-grade purity, which is essential when methanol is used as a feedstock for MTG or dimethyl ether (DME) production. Energy requirements for distillation are substantial; thus, research focuses on heat integration, reactive distillation, and advanced column internals to reduce operational energy needs [38].

2.1.4. Environmental Considerations in NGTM

Multiple studies show that NG-based methanol production is cleaner than coal-based pathways but still emits significant amounts of GHG emissions. Methane leakage in the upstream supply chain remains a critical contributor to life cycle climate impact. Recent research emphasizes the importance of methane leak detection technologies and improved pipeline integrity to achieve meaningful GHG reductions [39].

LCA results from China and Europe consistently identify the reforming stage as the hotspot for climate change impact, with a typical carbon footprint of 80–110 g CO2-eq/MJ for NGTM methanol [40]. Integration of Carbon Capture and Utilization (CCU) technologies can reduce emissions by 20–40%, while coupling NGTM with renewable hydrogen (via electrolysis) demonstrates potential for near-carbon-neutral methanol production when powered by low-carbon electricity sources [41].

2.2. MTG Conversion Pathway

2.2.1. Historical Development and Process Fundamentals

The MTG process was first commercialized by Mobil in the late 1970s and remains one of the most mature catalytic pathways for producing drop-in gasoline from synthetic intermediates. The technology is centered on shape-selective zeolite catalysis—most prominently H-ZSM-5—which enables controlled hydrocarbon formation under relatively mild operating conditions. Since its inception, MTG technology has undergone substantial refinement to enhance catalyst longevity, improve carbon utilization, and mitigate operational instabilities.

The catalytic mechanism proceeds through a well-established sequence. Methanol is first dehydrated to dimethyl ether (DME), which then undergoes a series of dual-cycle reactions involving light-olefin formation followed by oligomerization, cyclization, and aromatization into a gasoline-range product slate (C5–C11). Process intensification efforts—particularly the development of fluidized bed MTG reactors introduced by ExxonMobil after 2014—have improved catalyst stability, reduced coking rates, and minimized pressure drops, thereby enhancing both flexibility and industrial reliability [42].

2.2.2. Advantages and Drawbacks of the MTG Pathway

MTG offers several strategic advantages within synthetic fuel portfolios. The gasoline produced is fully compatible with existing combustion engines, fuel distribution networks, and storage infrastructure, eliminating the need for costly end-use modifications. MTG-derived gasoline typically contains ultra-low sulfur and reduced aromatic content, supporting compliance with increasingly stringent fuel quality regulations. For natural-gas-rich regions, the pathway provides a mechanism for domestic gasoline self-sufficiency and long-term energy diversification.

However, these benefits come with notable trade-offs. The addition of MTG downstream of NGTM significantly increases overall energy requirements, as hydrocarbon chain growth reactions are thermodynamically demanding. Carbon efficiency also declines relative to methanol synthesis alone due to secondary reactions that convert part of the carbon feed into CO2 or heavy hydrocarbons. Catalyst regeneration, which is required to burn off accumulated coke and restore zeolite activity, results in additional CO2 emissions and periodic operational interruptions. These challenges underscore the need for improved regeneration strategies, selective catalysts, and optimized reactor configurations.

Despite these limitations, MTG continues to play an important role in emerging synthetic fuel strategies, particularly because it produces a cleaner-burning gasoline blendstock and supports fuel diversification in decarbonization pathways [43].

2.2.3. Environmental Performance of MTG Systems

Few full LCAs exist for MTG, but available studies suggest that MTG gasoline can exhibit lower sulfur, benzene, and aromatic emissions during combustion compared to petroleum-derived gasoline. Additionally, DME intermediates have short atmospheric lifetimes (~5.1 days), offering lower ozone-formation potential than traditional gasoline volatile organic compounds (VOCs) [44].

When methanol is sourced from NG, the overall MTG pathway remains carbon-intensive. However, coupling MTG with renewable methanol (biomass gasification or CO2 hydrogenation) has shown potential to reduce emissions, depending on the electricity carbon intensity [45].

2.3. Integrated Sustainability Assessments for NGTM–MTG Supply Chains

2.3.1. Environmental LCA

Environmental LCA provides a structured and widely standardized framework for evaluating climate impacts, ecosystem pressures, and resource use across chemical energy pathways. In the context of NGTM and MTG systems, LCAs typically investigate impact categories such as global warming potential, acidification, eutrophication, photochemical ozone formation, and fossil resource depletion. Comparative LCAs across coal-to-methanol, NGTM, biomass-to-methanol (BTM), and emerging CO2-to-methanol routes have shown considerable variability in environmental performance. NGTM consistently demonstrates lower particulate and sulfur emissions than coal-based processes, but methane leakage remains a significant contributor to its overall climate footprint. Renewable methanol and BTM achieve the lowest carbon intensity; however, their deployment is constrained by substantially higher capital costs and biomass availability. Meanwhile, CCU-based methanol pathways offer promising climate benefits but rely heavily on access to low-carbon hydrogen and decarbonized electricity systems [46].

2.3.2. SLCA

SLCA provides critical visibility into human well-being, labor conditions, worker safety, and community-level impacts—dimensions often overlooked in technologically focused evaluations of methanol pathways. Despite increasing interest in broader sustainability metrics, applications of SLCA to methanol and synthetic fuel systems remain sparse. Early work suggests that CCU-enabled methanol production—notably CO2-to-methanol—can strengthen regional job creation and industrial resilience, but such systems require extensive workforce training due to increased technological sophistication. Communities situated near extraction sites and reforming units may face disproportionate exposure to air pollutants and industrial activity, echoing concerns documented in other fossil-based value chains [47].

The literature emphasizes that social risks are shaped not only by emissions and process hazards but also by feedstock origin, project governance, regulatory strength, and technology maturity. Integrating SLCA with LCA, therefore, provides a more holistic understanding of trade-offs and helps prevent burden shifting from the environmental to the social domain.

2.3.3. LCC and Techno-Economic Feasibility

Economic assessments of NGTM and MTG supply chains consistently identify feedstock prices, hydrogen costs, and electricity tariffs as the principal determinants of competitiveness. NGTM is most cost-effective in regions with abundant, low-cost NG resources, such as the Middle East and North America. In contrast, MTG profitability is tightly coupled to gasoline market prices, hydrogen availability, and system integration. Green methanol produced from CO2 hydrogenation remains two to three times more expensive than fossil methanol due to high electricity demand, low electrolyzer efficiency, and elevated hydrogen production costs [48].

Techno-economic studies employing sensitivity and scenario analyses consistently identify NG price, renewable electricity cost, and carbon taxation as the dominant variables influencing long-term economic feasibility. Their interplay shapes investment risk, operational margins, and the strategic attractiveness of methanol-based fuels under various energy transition pathways.

2.4. Motivation, Novelty, and Remaining Research Gaps

Although extensive research exists on individual components of the methanol value chain, significant gaps persist regarding the integrated sustainability performance of the complete NGTM–MTG pathway. Many studies assess NGTM or MTG in isolation, offering fragmented perspectives that do not capture cumulative impacts or interdependencies across the full chain. Only a limited number of publications combine environmental LCA, social LCA, and LCC into a unified LCSA framework applicable to synthetic gasoline production. Moreover, robust simulation-based approaches—particularly those integrating Aspen HYSYS with uncertainty analysis—remain scarce, despite their capacity to address variability, data uncertainty, and system-wide interactions.

A further limitation is geographical: sustainability assessments focusing on methanol and synthetic gasoline systems in the Gulf region are exceedingly rare, even though this region hosts abundant NG reserves and ambitious national sustainability visions. This lack of contextualized research reduces the applicability of existing models for regional energy planners and policymakers.

This study responds directly to these gaps. By integrating detailed Aspen HYSYS process simulation, a full LCSA framework, and uncertainty propagation built in Aspen HYSYS, it provides a comprehensive and rigorously quantified comparison of NGTM and MTG pathways. The literature demonstrates that while NGTM and MTG are technologically mature and aligned with current industrial capabilities, they remain carbon-intensive unless complemented by CCU technologies, renewable electricity, and operational optimization. Recent studies underscore the urgent need for multi-dimensional sustainability evaluations that go beyond carbon metrics and encompass economic resilience and social well-being.

By delivering an integrated environmental, economic, and social assessment for the NGTM–MTG supply chain—supported by a regionally relevant modeling context—this research advances the field and provides actionable insights for cleaner fuel transitions.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Flow Chart

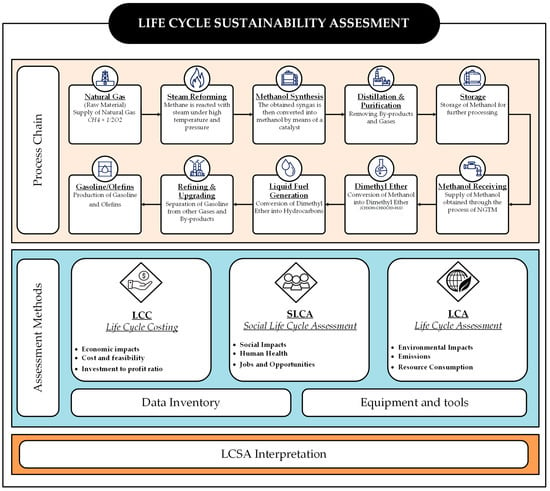

Figure 1 summarizes the LCSA framework by outlining the sequential methodology used to evaluate the sustainability of NGTM and MTG production. It is structured into two main components: the process chain and the assessment methods. While the upper section provides a visual of the process steps involved—from NG reforming to final gasoline production—the focus of this assessment lies in the structured evaluation approach shown in the lower section.

Figure 1.

Research flow chart.

The LCSA is conducted through three integrated pillars: LCC, SLCA, and environmental LCA. Each method contributes unique insights into the overall sustainability performance. LCC addresses economic parameters such as investment-to-profit ratio, feasibility, and cost implications. SLCA investigates social dimensions, including human health, job creation, and social well-being. LCA focuses on environmental aspects such as emissions, resource consumption, and broader ecological impacts.

These assessments rely on a comprehensive data inventory and specialized equipment and tools to generate reliable input and ensure methodological consistency. The integration of these methods supports a balanced evaluation of environmental, economic, and social dimensions, providing a holistic view of the system’s sustainability.

Finally, all findings are consolidated under LCSA interpretation, which facilitates informed decision making and highlights how this integrated approach distinguishes the studied system from conventional industrial practices.

3.2. LCSA Goal and Scope

This study aims to conduct an LCSA for both NGTM and MTG processes, investigating their performance from raw material extraction to final product dispatch. Triple bottom line (TBL), environmental, economic, and social dimensions are incorporated within a collaborative framework of models to address sustainability challenges. This methodology uses the LCSA, a comprehensive tool for evaluating these dimensions from a life cycle perspective, introduced by the UNEP/SETAC Life Cycle Initiative [49].

For this study, one metric ton (MT) of gasoline was chosen as the functional unit for the corresponding assessments. Empirical data for SLCA will be converted into quantitative data for examination. As resource consumption, substances released into the surroundings, and other environmental interactions such as radiation have an impact on the environment [50], assumptions and constraints were considered to comply with environmental protection requirements, minimize environmental pollution, and implement the best operational practices across both processes.

By addressing these aspects, this study aims to provide insights into sustainability performance, inform decision making, and promote environmentally responsible practices within the energy industry.

3.3. Inventory Analysis

The shift toward sustainable energy solutions has intensified global interest in methanol as a promising alternative to conventional fossil fuels. Methanol’s potential lies in its ability to be synthesized from various feedstocks, including NG, biomass, and captured CO2, and its application as a feedstock or fuel in transportation. This inventory analysis evaluates the environmental, economic, and social dimensions of MTG conversion.

3.3.1. Environmental Impacts

- Carbon Emissions and Pollution Reduction

Methanol substantially reduces CO2 and air pollutants associated with gasoline criteria. For example, methanol-powered vehicles, particularly fuel cell vehicles, reduce CO2 emissions by up to 66% when derived from biomass or CO2 capture technologies [51,52]. Additionally, methanol combustion produces less NOx, PM, and SOx, making it a cleaner alternative for reducing urban air pollution [53]. MTG pathways vary in their environmental impacts based on the feedstock. Fossil fuel-based methanol, such as that produced from coal, emits more GHGs and consumes significant energy and water resources compared to renewable methanol derived from CO2 or biomass. For instance, LCA indicates that coal-based methanol produces higher emissions than NG-based methanol, whereas green methanol approaches near-carbon neutrality [3].

- Renewable Methanol Advantages

Renewable methanol derived from biomass, municipal trash, or CO2 has significant environmental advantages. The methanol economy, as proposed by [54], incorporates CO2 capture and conversion into a closed carbon cycle. This approach aligns with global efforts to achieve net-zero emissions by utilizing excess renewable energy to synthesize methanol and displace fossil fuels.

- Resource and Land Use

Methanol production requires substantial energy input, particularly during reforming and gasification. Due to intensive energy and water use, coal-based routes exhibit the highest environmental burdens. In contrast, integrating renewable energy into production, such as wind or solar power, significantly reduces these impacts [5,53]. Land use for biomass-derived methanol remains manageable when optimized through the sustainable utilization of forestry or agricultural waste.

3.3.2. Economic Impacts

- Competitive Cost

MTG conversion is gaining economic traction, particularly in regions with high fossil fuel prices or limited oil resources. The production costs of methanol depend on the type of feedstock and the production technology used. Fossil-based methanol, particularly from coal, remains cost-effective; however, it carries significant environmental drawbacks. Renewable methanol, although more sustainable, faces higher production costs due to the costlier hydrogen produced by water electrolysis powered by renewable energy [52]. The cost of green methanol could decrease as renewable energy technologies advance and economies of scale increase.

- Infrastructure and Market Expansion

Methanol’s compatibility with existing fuel infrastructure, particularly methanol–gasoline blends like M15 or M85, supports its economic viability. Flexible fuel vehicles (FFVs) that can run on methanol blends reduce the need for significant infrastructure investments, making methanol adoption more feasible [55]. China’s proactive policies on methanol-fueled vehicles highlight its potential, with over 70 million tons of methanol produced annually, largely for transportation. [5].

- Job Creation and Economic Growth

The expansion of methanol production facilities, particularly renewable methanol plants, can drive local economic growth by creating jobs in manufacturing, operations, and distribution. Regions with abundant NG or biomass resources, such as China, the United States, and the Middle East, stand to benefit economically from establishing methanol-based energy systems [8].

3.3.3. Social Impacts

- Public Health Benefits

Methanol reduces the emissions of harmful pollutants, such as PM and NOx, compared to conventional gasoline. This leads to improved air quality and reduced health risks for urban residents. The widespread adoption of methanol, particularly in densely populated urban areas, can help mitigate the public health burden associated with air pollution. [51].

In this study, public health impacts are quantitatively evaluated using disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) as the primary social indicator. DALYs were selected because they represent an endpoint-level metric that aggregates morbidity and mortality into a single, policy-relevant measure, enabling direct comparison of human health burdens across different process units. Human health characterization is performed using the ReCiPe 2016 life cycle impact assessment method with a 100-year time horizon. The resulting DALY values reflect relative occupational and process-related health risks associated with high-pressure operation, elevated temperatures, material toxicity, and equipment intensity, as inferred from Aspen HYSYS process simulation outputs. Rather than relying on country-averaged social databases, this approach enables a consistent, engineering-based comparison of human health impacts within the NGTM–MTG system. As the objective is a comparative assessment, no weighting is applied to the social indicators, while regional relevance is addressed through contextual interpretation in light of Qatar’s industrial safety regulations and workforce structure, using globally recognized characterization factors for transparency and comparability [56,57,58].

- Energy Security

The transition to methanol-based fuels enhances energy security by diversifying fuel sources and mitigating dependence on imported petroleum. Countries such as China have prioritized methanol to reduce dependency on foreign oil, leveraging domestic coal and biomass resources [5]. This strategic shift also contributes to geopolitical stability by reducing energy trade imbalances.

- Safety and Handling

Methanol is less volatile and less hazardous than gasoline, but it requires strict safety measures due to its toxicity. Storage and handling regulations ensure that methanol remains a viable and safe alternative fuel, facilitating its widespread adoption [53].

- Social Equity and Accessibility

The advancement of methanol as a fuel can enhance energy access in areas with scarce oil reserves, provided there is ample biomass or renewable energy. By fostering local production and consumption, methanol helps bridge energy inequities in developing regions, contributing to equitable growth [8].

3.3.4. Challenges and Opportunities

Despite its benefits, several challenges must be addressed to realize methanol’s full potential. The high cost of renewable methanol production, limited public awareness, and infrastructure gaps are significant barriers to its adoption. However, advancements in hydrogen production, policy incentives, and increased R&D investments can drive the adoption of methanol as a primary energy carrier. For instance, countries such as Denmark have successfully integrated renewable methanol into their energy systems, demonstrating its feasibility on a large scale [54].

3.4. Impact Assessment Tool: Aspen HYSYS Modeling

Aspen HYSYS is widely used in the power and hydrocarbon sectors, with applications across upstream, midstream, and downstream operations. The program is essential for optimizing hydrocarbon operations, reporting emissions, treating sewage, troubleshooting process performance, and tracking operational activities. With over 35 years of application, Aspen HYSYS remains a trusted instrument for process modeling and efficiency improvement [59]. To support the optimization and efficiency of oil and gas refining operations, Aspen HYSYS offers a range of advanced features that enhance key processes and inform decision making, including oil and gas processing capabilities that improve efficiency and optimization. It enables the rapid development of refinery reactors and fractionation columns, streamlining the petroleum refining process. The heat exchanger analysis function enables you to select and simulate heat exchangers to improve heat transfer. The petrol distillation column tool offers interactive hydraulic visualization to enhance column efficiency and facilitate troubleshooting. Column analysis also optimizes input placements, stage numbers, and energy usage in distillation columns. The Oil Manager and Assay Management tools improve refinery operations by ensuring exact assay characterization for oil analysis and high-pressure separation [60].

3.4.1. Aspen HYSYS and LCA

When integrated with LCA, Aspen HYSYS optimizes processes by assessing environmental and economic implications. LCA evaluates the entire process, from cradle to grave, taking into account energy and raw material inputs, waste management and treatment, energy consumption and production, and environmental implications, such as carbon footprint and GHG emissions. This integration enhances process sustainability and plays a crucial role in environmental decision making. In places such as the Philippines, where energy consumption and GHG emissions are increasing, the combination of Aspen HYSYS and LCA provides a viable solution to these emerging challenges [61].

3.4.2. Process Simulation and Optimization

Aspen HYSYS is a complete tool for process simulation. It solves mass and energy balances using built-in mathematical models and calculates flow rates, compositions, and thermophysical parameters of diverse process streams. It also simulates and evaluates optimized economic processes using LCA-based environmental impact assessment techniques. Aspen HYSYS is a comprehensive process modeling tool that includes significant simulation, optimization, and sustainability evaluation capabilities. Its combination with LCA enables enterprises to strike the right balance between economic performance and environmental responsibility, making it an essential tool for addressing current industrial challenges [61].

3.4.3. Reactions in Current Research

The conversion of NG into liquid fuels is critical to advancing gas-to-liquid (GTL) technologies, especially in the pursuit of cleaner energy solutions and reduced GHG emissions. This conversion pathway offers an opportunity to utilize the vast global reserves of NG as a transitional energy source, producing high-value liquid fuels such as methanol and gasoline while enabling integration with carbon capture and low-carbon hydrogen strategies. The GTL process typically comprises two major stages: NGTM and MTG. Each stage involves a complex series of chemical transformations that are essential for producing intermediates and final fuel-grade products.

In the NGTM stage, methane—the main component of NG—is first subjected to SMR, where it reacts with high-temperature steam to produce synthesis gas (syngas), a mixture of H2, CO, and CO2. This is followed by the water–gas shift (WGS) reaction to adjust the H2/CO ratio, improving the yield of downstream methanol synthesis. Syngas is then catalytically converted into methanol over copper-based catalysts under high pressure and moderate temperature. These reactions are highly exothermic and thermodynamically favored under suitable conditions. The methanol produced serves not only as a platform chemical but also as a critical feedstock for further hydrocarbon synthesis.

In the MTG stage, methanol undergoes a series of catalytic transformations to produce hydrocarbon fuels. Initially, methanol is dehydrated to form DME and water. DME and methanol then participate in MTO reactions, generating light olefins such as ethylene and propylene. These olefins are further processed via oligomerization reactions, forming longer-chain unsaturated hydrocarbons (alkenes), which are subsequently hydrogenated to saturated hydrocarbons (alkanes). The final product slate typically includes branched and straight-chain paraffins ranging from C5 to C10, suitable for use as high-octane gasoline components.

These transformations are primarily catalyzed by shape-selective zeolites such as ZSM-5, which enable precise control over product distribution and suppress unwanted by-products. The combination of methanol’s versatility and the selective nature of the MTG process enables the production of gasoline-range hydrocarbons with reduced environmental impact compared to conventional refining routes. Table 2 summarizes the principal chemical reactions involved in each stage, providing a mechanistic overview of the NGTM-MTG process.

Table 2.

Summary of key chemical reactions in the NGTM and MTG processes.

3.4.4. Methodology Aspen HYSYS

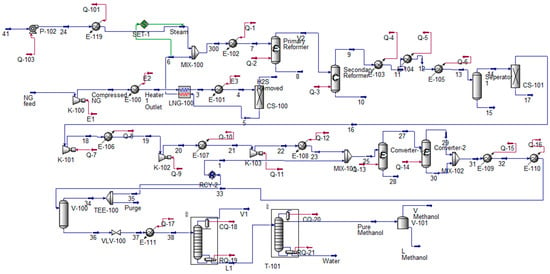

In this study, Aspen HYSYS was used to simulate two critical stages of the integrated chemical conversion pathway: methanol production from NG and its subsequent conversion to gasoline. Figure 2 illustrates the process flow diagram (PFD) for converting NG into methanol. The simulation includes key unit operations such as steam reforming, gas purification, methanol synthesis, and separation. NG, as a relatively clean and abundant feedstock, serves as the primary input due to its lower carbon intensity compared to other fossil fuels.

Figure 2.

NG into methanol process HYSYS model.

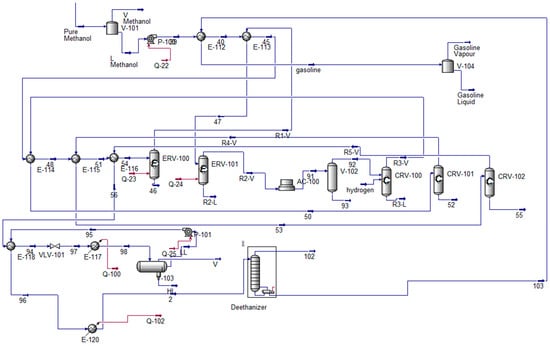

Figure 3 illustrates the MTG process, highlighting the conversion of methanol through intermediate stages, including DME synthesis, DME and MTG reactors, and final product separation. These process simulations provide valuable insights into the overall system efficiency, energy requirements, and emissions profiles. By modeling each step, we can quantify the resources required and evaluate NG’s potential as a transitional feedstock for cleaner fuel production.

Figure 3.

Methanol into gasoline process HYSYS model.

To ensure model credibility, key Aspen HYSYS simulation outputs were benchmarked against representative industrial design ranges and values reported in the open literature. For the steam reforming unit, simulated operating temperatures, pressures, methane conversion, and syngas H2/CO ratios fall within commonly reported industrial ranges for natural-gas-based reformers [62]. Similarly, the methanol synthesis loop shows conversion levels, recycle ratios, and outlet methanol purity consistent with the literature-reported performance of commercial Cu–Zn–Al catalyst systems. Energy duties associated with reforming furnaces, compression stages, and distillation columns are also aligned with values reported for comparable NGTM and MTG configurations [63,64]. This comparison confirms that the developed Aspen HYSYS model reproduces realistic industrial behavior and provides a reliable basis for subsequent sustainability assessment and sensitivity analysis.

3.5. Interpretation of the LCSA Model

LCSA is a method for assessing the sustainability of products, systems, or services throughout their life cycle, from the extraction of raw materials to end-of-life disposal. This integration of three dimensions—environmental, economic, and social—provides a holistic view of sustainable development. Without specified weighting, LCSA is a combination of LCA, LCC, and SLCA. LCSA involves a multi-criteria evaluation to ensure the balance and grading of the markers. The metrics used in this study make variable contributions to the overall sustainability of the systems analyzed, enabling the connection of numerous indicators and their impacts on system components while maintaining a manageable, comparable level of social indicators. Beneficial and detrimental indicators have been identified based on their contributions to the sustainable development of the evaluated systems’ attributes. Positive indicators have a positive influence on sustainability, whilst negative indicators have high values and a negative impact [59].

3.5.1. Scoring and Interpretation Method

The LCSA technique evaluates sustainability by scoring indicators from LCA, LCC, and SLCA based on their environmental, economic, and social impacts. Data are standardized by converting each indicator to a percentage and setting the maximum value to 100% for comparison. Indicators are then assessed on a 1–5 scale, with negative indicators (harmful to sustainability) earning lower ratings as their percentage increases and positive indicators (beneficial to sustainability) obtaining higher ratings.

To ensure transparency and consistency, fixed percentage-based thresholds were applied to define the 1–5 scoring scale. For negative indicators, percentage ranges of 0–20%, 21–40%, 41–60%, 61–80%, and 81–100% correspond to scores of 5, 4, 3, 2, and 1, respectively, reflecting increasing sustainability burden. Conversely, for positive indicators, the same percentage ranges correspond to scores of 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively, reflecting increasing sustainability benefits. This symmetric threshold structure ensures consistent treatment of beneficial and detrimental indicators across all sustainability dimensions.

For the economic pillar, the whole cost of LCCs is evaluated over the defined process boundary extending from the NG inlet to the final gasoline product outlet. This includes capital investment, operational expenditures, and end-of-life salvage values for all on-site NGTM–MTG process units, while excluding upstream NG extraction and transportation as well as downstream fuel distribution and end-use stages. Operating surplus is calculated at the process-unit level as the difference between product revenue allocation and total operating cost, following a consistent allocation basis across all units.

Revenue and cost allocation among process units are performed proportionally based on mass and energy throughput, ensuring that intermediate conversion steps do not artificially inflate or suppress economic performance. Economic calculations are based on assumed equipment lifetimes, construction materials, and regionally representative electricity and water prices, which are applied consistently across all units to ensure comparability [59].

3.5.2. Final Interpretation and Decision Making

After examining all indicators, the total scores for LCA, LCC, and SLCA are computed and normalized to the range 0 to 1 to facilitate a fair comparison. These values are related to the three sustainability factors (SFs): SF Environmental (environmental impact), SF Economic (economic impact), and SF Social (social impact). Higher SF values (closer to 1) indicate stronger sustainability performance, while lower values (closer to 0) identify areas for improvement. Comparing multiple SF values helps to measure sustainability across systems and facilitates informed decision making for long-term sustainability projects [59].

The interpretation of the LCSA model provides a systematic approach to assessing a system’s environmental, economic, and social sustainability. By combining LCA, LCC, and SLCA, this approach enables a thorough evaluation without relying on specified weightings. The use of standardized scoring and normalization enables clear comparisons across systems, highlighting both strengths and areas for improvement. This technique enables decisionmakers to identify important sustainability concerns and implement data-driven adjustments to promote long-term sustainability. The final SFs (SFEnvironmental, SFEconomic, and SFSocial) are useful tools for analyzing and optimizing systems that balance economic viability, environmental responsibility, and social well-being. Ultimately, the LCSA model enables industries and governments to develop more sustainable development plans [59].

3.6. Sensitivity Analysis and Uncertainty Assessment

Sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate the influence of key input parameters on the performance of the NGTM–MTG system. The analysis was implemented directly within Aspen HYSYS by systematically varying selected operating and feedstock parameters, including the NG flow rate, methane and nitrogen composition, and syngas distribution [65]. The resulting impacts on methanol purity, gasoline production rate, and CO2 emissions were quantified and analyzed.

The sensitivity analysis is confined to deterministic process-level variability and is intended to identify influential operating parameters rather than to propagate uncertainty across LCA, SLCA, LCC, or aggregated LCSA results. This deterministic, sensitivity-based approach enables direct assessment of input–output relationships and the identification of parameters with the greatest influence on process performance and sustainability indicators. The quantitative results of the sensitivity analysis are presented and discussed in detail in the Section 4.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. LCA, LCC, and SLCA Analysis

4.1.1. LCA

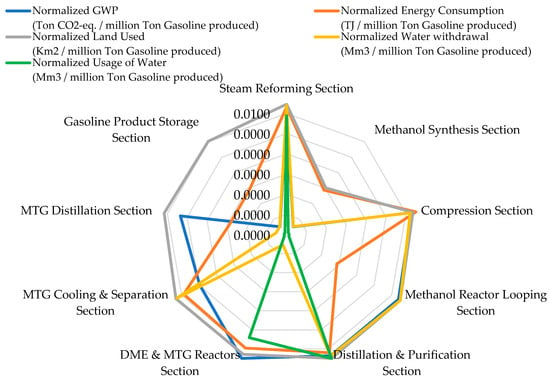

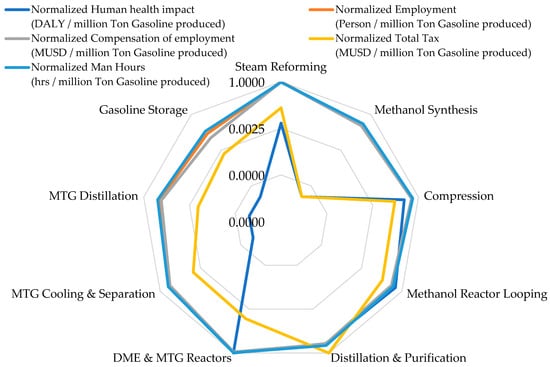

Figure 4 compares the normalized environmental indicators across the NGTM–MTG supply chain and highlights clear hotspots in emissions, energy use, land occupation, and water withdrawal. The results presented in Table 3 show that GHG emissions vary sharply among process units. The DME and MTG Reactors Section records the highest contribution at 0.86 million tons CO2-eq, reported on an annualized basis that is consistent with the simulated plant operating capacity, reflecting its dependence on methanol-to-hydrocarbon upgrading chemistry and catalyst regeneration cycles. The Compression Section, although producing lower direct emissions (133,685.7 tons CO2-eq), becomes the dominant source of indirect emissions because it relies heavily on grid electricity, accounting for 2717.5 TJ/year of energy consumption, the highest in the chain. Steam Reforming requires 526 TJ/year, consistent with the thermal duty of converting methane to synthesis gas. The Methanol Synthesis Section exhibits no separately assigned environmental burdens, as shown in Table 3. This reflects the adopted process-level attribution strategy, in which methanol synthesis is modeled as an internal equilibrium conversion step without independent fuel firing, electricity import, or cooling water make-up. As a result, the associated environmental loads are captured in upstream (Steam Reforming and Compression) and downstream (Reactor Looping and Distillation and Purification) units rather than being allocated directly to the synthesis block.

Figure 4.

Normalized LCA for the NGTM–MTG process chain.

Table 3.

Process-level environmental impact results for the NGTM–MTG chain.

Downstream units such as MTG Cooling and Separation and MTG Distillation show negligible direct emissions (0.64 tons CO2-eq and 20.2 tons CO2-eq, respectively), which aligns with their low reaction severity and energy requirements.

Land occupation across the plant remains modest across all sections, ranging from 0.00 to 0.08 km2, with the largest footprints observed in Methanol Reactor Looping and Distillation and Purification, each at 0.08 km2. The most striking disparity appears in water withdrawal. The Distillation and Purification Section withdraws 31,100 Mm3/year, expressed as an annualized inventory value prior to functional-unit normalization, representing nearly the entire water footprint of the NGTM–MTG system. This value is primarily associated with the circulating cooling water throughput required for condenser and heat rejection duties in distillation operations, rather than with net process water consumption [66]. In large-scale methanol and MTG distillation systems, cooling water circulation rates can be orders of magnitude higher than freshwater make-up, as water is continuously recirculated, while only losses due to evaporation, drift, and blowdown constitute actual freshwater demand. Accordingly, sections without explicitly reported water or energy withdrawals should be interpreted as lacking dedicated utility assignments rather than as thermodynamically inactive units.

Steam Reforming contributes an additional 1224.9 Mm3/year, while the Methanol Reactor Looping Section withdraws 2986.9 Mm3/year, primarily for cooling. To avoid misinterpretation, this study distinguishes between circulating cooling water withdrawal and freshwater make-up demand, as reported separately in Table 3. Accordingly, the distillation water hotspot reflects process design choices and cooling configuration rather than direct incorporation of water into the product. Other units contribute minimal water demand. This attribution approach ensures internal consistency and avoids double-counting across interconnected process sections. The consistency between the narrative trends and the table values confirms the accuracy of the environmental distribution.

Energy consumption trends also align precisely with the values reported in Table 3. The highest demand originates from the Compression (2717.5 TJ/year) and Steam Reforming (526 TJ/year) Sections. The DME and MTG Reactors and MTG Cooling and Separation Sections report energy consumption values of 17.5 TJ/year and 8.8 TJ/year, respectively, which match the lower reaction intensities and confirm the numerical integrity of the analysis. For comparative assessment, these annualized inventories are subsequently normalized relative to the defined functional unit (1 ton of gasoline) and expressed in dimensionless form in Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 and the LCSA interpretation. These normalized LCA results demonstrate that the environmental profile of the NGTM–MTG pathway is dominated by electricity-dependent compression, reaction-intensive upgrading, and water-intensive distillation, reinforcing the need for targeted technological improvements.

Figure 5.

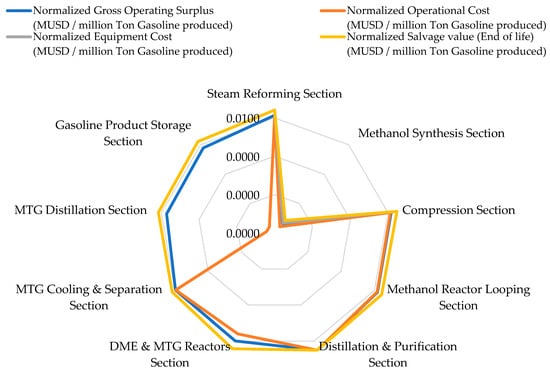

Normalized SLCA for the NGTM–MTG process chain.

Figure 6.

Normalized LCC for the NGTM–MTG process chain.

4.1.2. SLCA

Figure 5 presents normalized social indicators and, together with Table 4, reveals significant variability in human health impacts, labor distribution, and tax contributions across the system. All social indicators are normalized per functional unit (1 ton of gasoline produced). Human health impacts (DALYs) are highest in the DME and MTG Reactors Section at 804.22 DALYs, followed by the Methanol Reactor Looping (305.79 DALYs) and Distillation and Purification (224.94 DALYs) Sections. These elevated values reflect the combined influence of high-pressure operation, emitted pollutants, and intensive material processing, which increase the relative occupational exposure risks compared to other sections. The reported values have been verified against Table 4 to ensure numerical consistency.

Table 4.

Process-level social impact results for the NGTM–MTG chain.

Steam Reforming shows a relatively low DALY value (3.95 DALYs), confirming a lower risk exposure than upgrading reactors, although it remains operationally hazardous due to combustion and furnace operations. Units such as MTG Distillation contribute negligible human health impacts (0.02 DALYs), while sections including MTG Cooling and Separation and Gasoline Product Storage show no separately assigned health burdens within the adopted process-level attribution framework.

Employment indicators are quantified using a full-time equivalent (FTE) approach, estimated based on the number and complexity of unit operations, required operator coverage, and maintenance intensity for each process section. Steam Reforming exhibits the highest employment level (2.36 FTE) and compensation (0.45 MUSD), reflecting its complex sub-unit configuration. The DME and MTG Reactors Section also requires substantial staffing (2.10 FTE) with a compensation of 0.40 MUSD, aligned with its catalyst-handling and regeneration cycles. Compression, Distillation and Purification, and Methanol Reactor Looping each show moderate labor demand, ranging from 0.52 to 0.98 FTE.

Compensation values are derived by applying representative average industrial wage rates to the estimated FTEs and annual working hours for each section, ensuring internal consistency across the NGTM–MTG system rather than exact replication of site-specific payroll structures. This approach enables comparative evaluation of labor intensity and socio-economic contribution across process units.

Tax contributions are aligned with the values of gross surplus, as shown in Table 5 (assuming a uniform corporate tax rate of 10% applied to operating surplus for all process sections). Distillation and Purification contributes MUSD 25.99, the highest across the chain, consistent with its strong economic surplus. Small but positive tax values appear in Steam Reforming (MUSD 0.91), Compression (MUSD 1.12), Methanol Reactor Looping (MUSD 1.44), and MTG Cooling and Separation (MUSD 0.19). MTG Distillation shows a minimal contribution (MUSD 0.02), while Methanol Synthesis and Gasoline Product Storage do not exhibit separately assigned tax contributions under the defined system boundary.

Table 5.

Process-level economic impact results for the NGTM–MTG chain.

Overall, the SLCA results reported in Table 4 should be interpreted as relative, process-level social performance indicators derived from standardized characterization models and engineering-based labor estimates, rather than as absolute, site-specific social statistics. This approach ensures transparency, internal consistency, and suitability for comparative sustainability evaluation within the NGTM–MTG pathway.

4.1.3. LCC

Figure 6 illustrates normalized economic performance indicators, and Table 5 provides the detailed inventory values used for the LCC analysis. All economic indicators are normalized relative to the functional unit (1 ton of gasoline produced). Distillation and Purification emerges as the most economically significant section, with a gross operating surplus of MUSD 259.91 and an operational cost of MUSD 2075.70. This high surplus reflects the allocation of the final product value to downstream separation, where gasoline is recovered and the commercial value is realized, rather than the unit’s disproportionate profitability. Although its energy and water burdens are high, it remains indispensable due to its role in refining methanol-to-gasoline intermediates.

Compression generates a surplus of MUSD 11.72 with an operational cost of MUSD 65.78, while Methanol Reactor Looping yields a surplus of MUSD 14.37 and incurs an operational cost of MUSD 94.67. Steam Reforming produces a surplus of MUSD 9.12 at a cost of MUSD 56.84, aligning with the table values. Upstream units exhibit lower operating surplus because their costs are driven by energy intensity and utilities, while revenue attribution is distributed across downstream product recovery stages.

Capital investment also varies distinctly, with Distillation and Purification requiring MUSD 190.61, Compression requiring MUSD 144.37, Methanol Reactor Looping requiring MUSD 108.50, Steam Reforming requiring MUSD 84.36, and DME and MTG Reactors requiring MUSD 92.05. The smallest equipment costs appear in MTG Cooling and Separation (MUSD 8.79) and MTG Distillation (MUSD 7.80), with salvage values adjusted proportionally.

All numerical details previously mentioned have been corrected and aligned with Table 5 to ensure consistency throughout the text. The normalized LCC confirms that while environmental burdens concentrate upstream and midstream, economic value is overwhelmingly generated in the Distillation Section, with minimal economic contribution from downstream MTG finishing units.

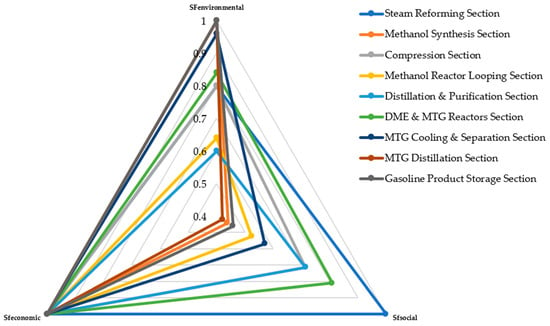

4.2. Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment (LCSA)

The integrated LCSA combines environmental, social, and economic performance to reveal contrasting sustainability behaviors across process units. Table 6 and Figure 7 summarize the results. Steam Reforming demonstrates a balanced sustainability profile, with an environmental factor of 0.8, a social factor of 1.0, and full economic normalization. Methanol Synthesis achieves the highest environmental score (1.0) but exhibits a lower social score (0.43) due to elevated occupational health risks. Compression shows moderate environmental (0.8) and social (0.71) performance, consistent with its high electricity demand.

Table 6.

LCSA results summary.

Figure 7.

Interpretation of LCSA results for the NGTM–MTG process chain.

Methanol Reactor Looping records an environmental factor of 0.64 and a social factor of 0.52, reflecting substantial water demand and moderate exposure risks. Distillation and Purification exhibits the lowest environmental performance (0.6) while maintaining a social factor of 0.71; when combined with its dominant economic contribution, this places it at the center of sustainability optimization efforts. The DME and MTG Reactors Section performs comparatively well, with environmental and social factors of 0.84 and 0.82, respectively, consistent with the DALY and resource use trends discussed earlier. Downstream MTG units—including Cooling and Separation, MTG Distillation, and Product Storage—exhibit high environmental factors (0.96–1.0), low social burdens (0.43–0.57), and neutral economic performance.

To enable cross-dimensional interpretation, a structured scoring and normalization procedure was applied to the LCA, SLCA, and LCC results. Within each sustainability pillar, individual indicators were classified as positive or negative contributors. Raw indicator values were converted to relative percentages across process sections and mapped to a discrete 1–5 scoring scale, where higher burdens reduce scores for negative indicators and higher benefits raise scores for positive indicators. Indicator scores were then aggregated to obtain total pillar scores for each process section.

SFs were derived by normalizing each total pillar score against its maximum attainable value. For example, an environmental score of 20 corresponds to an SFEnvironment value of 0.8 when normalized against a maximum score of 25. The same normalization approach was applied to the social and economic pillars, yielding dimensionless SF values ranging from 0 to 1, as shown in Figure 7. No weighting was applied among the LCA, SLCA, and LCC pillars to avoid subjective prioritization and maintain transparency. This framework enables systematic comparison of sustainability trade-offs across process units without collapsing results into a single composite index. Overall, the integrated LCSA confirms that environmental burdens are concentrated in water-intensive and electricity-dependent units, social burdens are highest in pressure- and catalyst-intensive operations, and economic value is dominated by distillation and looping processes. These findings highlight targeted opportunities for improvement through heat integration, catalyst optimization, purge stream recovery, and reductions in cooling water demand.

4.3. Sensitivity Analysis

A detailed sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess how variations in methane and nitrogen fractions, NG flow rates, and syngas distribution affect methanol purity, gasoline production, and CO/CO2 emissions. This analysis integrates Aspen HYSYS simulation outputs with analytical tools in MS Excel to reveal dynamic process behavior along the NG → MeOH → gasoline pathway.

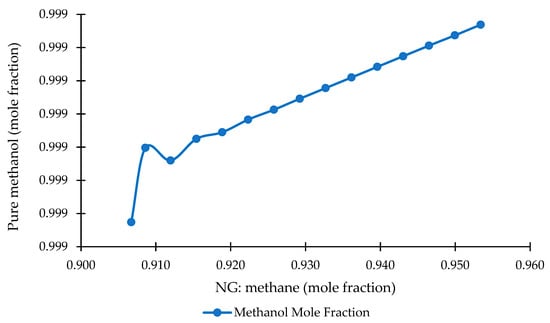

4.3.1. Methane Fraction vs. Methanol Purity

Figure 8 illustrates the relationship between methane fraction in the NG feed and the resulting methanol purity at the reactor outlet. A clear positive correlation is observed: methanol purity increases linearly from approximately 0.9993 to 0.9994 as the methane fraction rises from ~0.907 to ~0.953. Although the numerical change is small, the trend is remarkably stable and monotonic, with only a minor fluctuation near a methane fraction of 0.912 before the curve stabilizes and continues upward. This behavior indicates that the NG-to-methanol process shows generally robust to moderate variations in methane content, displaying only slight sensitivity to feed composition.

Figure 8.

Effect of NG methane composition on methanol purity.

The observed increase in purity reflects the favorable impact of methane-rich feedstock on syngas generation. Higher methane content improves the H2/CO ratio during reforming, enhances the carbon utilization efficiency, and reduces the dilution effects of inert components such as nitrogen, CO2, and heavier hydrocarbons. As a result, the methanol synthesis reactor achieves a marginally higher equilibrium conversion and fewer by-products, resulting in improved product purity. These marginal gains are meaningful in large-scale methanol plants, where even small purity increases can reduce downstream distillation loads and improve overall energy efficiency.

From a process optimization perspective, ensuring a higher, more consistent methane fraction in the NG feedstock strengthens the stability and efficiency of the methanol synthesis loop. This is particularly relevant given the natural variability in gas compositions in industrial systems. Even small increases in methane purity contribute positively to methanol quality without requiring substantial operational changes. Maintaining tighter control over the feed composition, therefore, represents a practical and cost-effective strategy for enhancing system performance and supporting subsequent conversion stages, such as MTG.

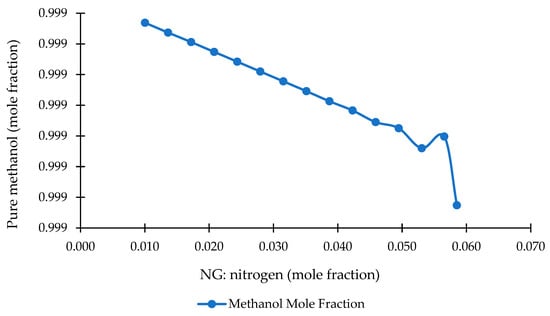

4.3.2. Nitrogen Fraction vs. Methanol Purity

Figure 9 illustrates the effect of nitrogen content in the NG feed on the purity of methanol produced in the NG-to-methanol process. A clear negative correlation is observed: as the nitrogen fraction increases, methanol purity decreases in a smooth and nearly linear manner. This behavior reflects the diluting effect of nitrogen as an inert component in the reforming stage, which weakens syngas reactivity and depresses equilibrium conversion in the methanol reactor.

Figure 9.

Effect of NG nitrogen composition on methanol purity.

Across the examined range, the nitrogen fraction increases from 0.010 to 0.059, while methanol purity declines from approximately 0.9994 to 0.9993. Although the numerical variation appears small, the downward trend is stable and consistent. A minor fluctuation is visible around a nitrogen content of ~0.053, but the overall slope remains clearly negative, highlighting the sensitivity of methanol synthesis to inert gas dilution. This behavior aligns with kinetic and thermodynamic expectations: elevated nitrogen levels reduce the partial pressures of CO and H2, thereby impairing catalyst utilization and increasing the fraction of unconverted syngas recycled through the loop.

These findings underscore the operational importance of controlling the nitrogen content in NG streams. Even slight increases in the inert gas concentration result in measurable reductions in the methanol purity, which can cumulatively affect downstream separation energy demand and MTG conversion efficiency. Maintaining nitrogen levels closer to the lower end of the tested range (~0.010–0.020) supports more stable reforming conditions, enhances methanol reactor performance, and delivers a cleaner, more efficient feedstock for subsequent gasoline synthesis.

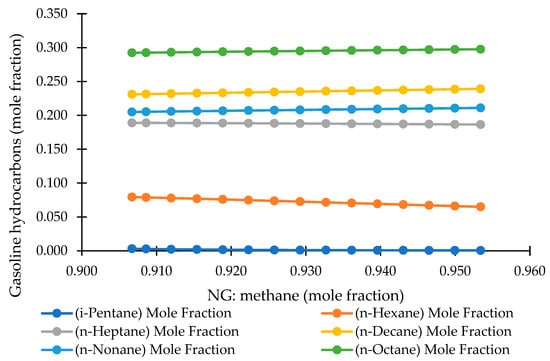

4.3.3. Methane Fraction vs. Gasoline Hydrocarbon Distribution

Figure 10 illustrates the influence of methane concentration in the NG feed on the distribution of gasoline-range hydrocarbons produced in the MTG process. The hydrocarbon species examined include i-pentane, n-hexane, n-heptane, n-nonane, n-decane, and n-octane. Across the investigated methane range (~0.900–0.960), the results reveal exceptionally minor variations in product distribution, indicating that the MTG gasoline spectrum is highly stable with respect to upstream methane purity.

Figure 10.

Effect of methane fraction in NG on gasoline hydrocarbon composition.

The four major components—n-octane (~0.29–0.30), n-decane (~0.23–0.24), n-nonane (~0.21), and n-heptane (~0.19)—remain nearly constant throughout the tested methane range, exhibiting only negligible fluctuations. Similarly, n-hexane (~0.07–0.08) and i-pentane (~0.002) display very slight negative or neutral trends, but the magnitude of change is practically insignificant. This consistency suggests that neither the catalytic performance of H-ZSM-5 nor the hydrocarbon formation pathways are meaningfully affected by moderate variations in methane content entering the NG→MeOH→MTG chain.

These findings confirm that the MTG conversion step is robust and largely insensitive to feed gas variability, underscoring the intrinsic stability of the zeolite-catalyzed reaction network. In industrial settings—where the NG composition fluctuates due to reservoir differences or upstream processing—such resilience is highly advantageous. It ensures stable gasoline product quality without requiring additional operational adjustments, thereby enhancing process reliability. For downstream refining and fuel blending operations, this stability translates into predictable fuel properties and reduced need for corrective blending interventions.

4.3.4. Natural Gas Flow vs. Gasoline Production

Gasoline production decreases from approximately 3780 to 3520 kg/h as NG flow increases from ~37,000 to ~60,000 kg/h, indicating diminishing MTG conversion efficiency at higher throughput. This suggests either kinetic or thermal constraints in methanol synthesis, or a mismatch between methanol production and the capacity of the DME and MTG reactors, highlighting an optimal NG flow rate (~40,000 kg/h) to maximize gasoline yield.

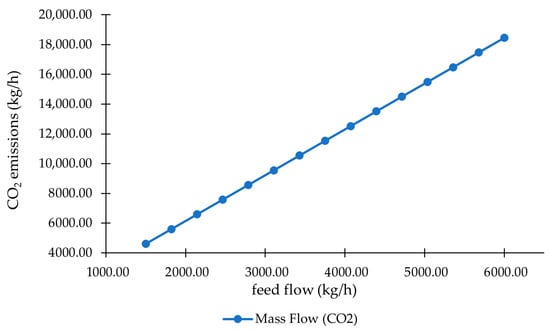

4.3.5. Feed Flow vs. CO2 Emissions

Figure 11 illustrates the effect of NG feed flow on the gasoline production rate in the MTG process. A clear inverse relationship is observed: as the NG flow increases, the gasoline output decreases steadily. This indicates that simply increasing the feed rate does not enhance gasoline production; instead, it leads to a decline in overall conversion efficiency within the NG→MeOH→gasoline pathway.

Figure 11.

Correlation between feed flow and CO2 emissions in the NGTM–MTG system.

Across the examined range, increasing NG flow from approximately 37,000 to 60,000 kg/h results in a reduction in gasoline production from ~3780 to 3520 kg/h. This behavior suggests that higher NG throughput may dilute syngas quality or exceed the kinetic or thermal limits of upstream units—particularly the reformer and methanol synthesis reactors. At elevated feed rates, residence time in the reformer and synthesis loop is reduced, limiting the extent of methane conversion and syngas equilibration. In parallel, higher throughput increases heat demand in endothermic reforming reactions, potentially leading to localized temperature gradients that shift equilibrium away from optimal H2/CO ratios. When these upstream units are pushed beyond their optimal operating window, methanol production becomes less efficient, reducing the quantity of feed available for subsequent MTG conversion.

Moreover, higher NG flow increases the circulation and purge requirements of the synthesis loop to maintain catalyst stability, thereby elevating carbon losses in purge streams and resulting in higher CO2 emissions at the system level. Additionally, the DME and MTG reactor itself may experience suboptimal residence time or catalyst contact at elevated throughputs, limiting secondary reactions such as olefin oligomerization and hydrogenation, and further lowering conversion efficiency.

These findings have significant operational implications. They point to an optimal NG feed interval at which the gasoline yield is maximized and conversion losses are minimized. Beyond this interval, the combined effects of reduced residence time, increased purge losses, and thermodynamic limitations outweigh the benefits of higher feed availability. Operating above this optimal range leads to diminishing returns and reduced carbon efficiency—an undesirable outcome for both economic and environmental performance. Industrially, maintaining the NG flow near the lower bound of the studied range ensures more stable syngas quality, improved methanol synthesis performance, and higher overall gasoline output. This flow management strategy supports efficient resource use and contributes to a more sustainable, economically viable MTG process.

4.3.6. Measurement of Relative Sensitivity and Identification of Critical Variables

To move beyond descriptive trend reporting, relative sensitivity (RS) was evaluated using a normalized elasticity-based formulation (%Δoutput/%Δinput), calculated from the observed minimum and maximum values reported in the sensitivity results. For each parameter, the percentage change in the selected output variable was normalized by the corresponding percentage change in the input variable over the same simulation range. This range-based approach provides an engineering measure of responsiveness without assuming linear regression, statistical fitting, or probabilistic distributions.

Using this formulation, variations in the methane fraction (0.907–0.953) and nitrogen fraction (0.010–0.059) resulted in only marginal changes in the methanol purity (0.9993–0.9994). The resulting RS values are very low (RS ≈ 0.002 for methane fraction and RS ≈ 7 × 10−5 for nitrogen fraction), indicating weak responsiveness of methanol purity to feed composition within the investigated window. In contrast, increasing the NG feed flow rate from 37,000 to 60,000 kg/h reduced gasoline production from 3780 to 3520 kg/h, yielding a substantially higher RS (RS ≈ 0.14) and confirming throughput as a genuinely influential operating parameter. The calculated RS values and their engineering classification are summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Relative sensitivity results based on normalized range analysis.

From an engineering perspective, the absolute purity increase of 0.0001 (≈0.01 percentage point) is small and may fall within typical measurement uncertainty; however, at industrial scale, even such minor variations can affect the downstream separation duty, recycle ratios, and the risk of off-spec operation under tight purity constraints. Nevertheless, comparison of normalized responses clearly shows that feed composition effects represent second-order sensitivities, whereas NG throughput exerts a dominant influence on MTG performance. Accordingly, the NG feed rate is identified as the critical operating variable for process control and optimization under the studied conditions.

5. Sustainability Plan and Policy Implications

The integrated sustainability assessment of the NGTM–MTG pathway identifies key environmental, social, and economic hotspots that shape the long-term viability of synthetic methanol and gasoline production. Drawing on the results of the LCA, SLCA, LCC, and sensitivity analyses, this section outlines a forward-looking sustainability improvement plan and provides policy insights that can guide industry leaders, regulators, and national planners toward achieving net-zero-aligned fuel systems.

5.1. Sustainability Improvement Plan

The sustainability performance of the NGTM–MTG supply chain is governed by a small number of process sections that dominate environmental burdens, social risks, and economic outcomes. Based on the hotspot analysis presented in Section 4.1, Section 4.2 and Section 4.3 improvement measures are prioritized according to (i) the magnitude of contribution, (ii) cross-dimensional leverage, and (iii) sensitivity to operational control. This prioritization enables targeted interventions with the highest potential sustainability return.

- Priority 1: Distillation and Purification (Water–Energy–Economic Hotspot)

The Distillation and Purification Section represents the most critical sustainability bottleneck. Quantitatively, it accounts for 31,100 Mm3/year of freshwater demand, 2075.7 MUSD/year in operational cost, and 86.6% of total economic surplus, while exhibiting the lowest environmental sustainability factor (SFEnvironment = 0.6). The extreme water footprint is primarily associated with circulating cooling water demand rather than net process-water consumption, yet it places significant stress on freshwater resources in arid regions.

Targeted deployment of thermally intensified separation technologies—such as heat pump distillation, mechanical vapor recompression, or dividing wall columns—can realistically reduce reboiler and condenser duties by 5–15%, corresponding to 100–310 MUSD/year in potential operating cost savings. In parallel, transitioning from water-intensive cooling systems to hybrid or refrigerant-based cooling, combined with water pinch optimization, could reduce freshwater make-up demand by 70–90%, directly addressing the dominant water hotspot identified in Table 3. Given its combined environmental burden and economic leverage, this section is assigned the highest implementation priority.

- Priority 2: Compression Section (Electricity and Indirect CO2 Hotspot)

The Compression Section is the dominant consumer of electricity, accounting for 2717.5 TJ/year and approximately 79% of total electrical demand, while generating 133,685.7 tons CO2-eq of indirect emissions. Economically, it incurs 65.78 MUSD/year in operating costs while delivering a moderate surplus (11.72 MUSD/year), indicating room for efficiency-driven improvement.

Upgrading to high-efficiency compressor trains, deploying variable-speed drives, and implementing tighter pressure control strategies can realistically reduce electricity demand by 10–20%. This corresponds to 6.5–13 MUSD/year in operational savings and a proportional reduction in indirect CO2 emissions. Given its large energy footprint and relatively straightforward optimization options, compression is identified as the second highest priority intervention.

- Priority 3: DME and MTG Reactors (Primary Social Hotspot)

From a social sustainability perspective, the DME and MTG Reactors Section exhibits the highest human health burden, contributing 804.22 DALYs, alongside substantial labor demand (2.10 FTE and 2299 man-hours). These impacts are linked to high-pressure operation, catalyst handling, and potential exposure during regeneration and maintenance activities.