Abstract

This study examined land-use/land-cover (LULC) change in the Manas River Basin from 2000 to 2020 due to rapid socioeconomic development. It aims to provide a scientific basis for protecting the ecological security of the river basin and achieving sustainable development of the land. The LULC data of 2000, 2010, and 2020 were utilized to establish the LULC transition matrix and calculate the LULC dynamics to analyze the dynamic evolution of LULC in the basin from 2000 to 2020. The PLUS model was constructed to explore the driving mechanism of the conversion between various land types in the basin. The key findings include the following. (1) From 2000 to 2010, grassland experienced the most significant reduction (3222.08 km2), whereas farmland expanded the most (3126.77 km2). (2) The most rapid expansion occurred in farmland (6.24%) and built-up areas (2.25%) in the 2000–2010 and 2010–2020 periods, respectively. Conversely, forest land showed the most rapid decrease, with −6.07% from 2000 to 2010, and −0.86% from 2010 to 2020. (3) The degree of influence of each driving factor on different LULC types (contribution degree) obtained by constructing the PLUS model shows that, during the twenty years, population was the predominant factor affecting farmland changes and built-up areas, with contribution degrees of 0.17 and 0.26, respectively. Temperature was the primary influencer of forest-land changes, with a contribution degree of 0.17, and elevation significantly impacted grassland changes, with a contribution degree of 0.21. This study provides crucial insights into the interaction between LULC dynamics and environmental and demographic factors in the Manas River Basin.

1. Introduction

With the evolution of natural processes such as global warming [1], the expansion and intensification of the scope and intensity of human activities [2], and the improvement of the degree of exploitation of water and land resources, the LULC pattern has undergone great changes [3]. Desert oases [4], glaciers [5], and other natural areas with strong response to environmental changes and fragile ecological resources have changed rapidly and obviously; they have been increasingly damaged, the ecological environment degradation is prominent, and the stability and resilience are poor [6], thus seriously hindering the sustainable development of the river basin. How to improve LULC efficiency, maintain the ecological security of the basin, and meet the needs of the continuous development of the ecological environment and LULC in the future LULC planning of the Manas River Basin are important issues for the future LULC development of the Manas River Basin.

Numerous scholars have researched LULC change and its influencing factors at different spatial scales, established explanatory models, and generated meaningful insights [7,8,9,10]. A growing awareness of population increases and environmental issues occurred in the 1990s. It was recognized that these problems resulted primarily from social development, indicating that LULC change was the principal contributor to global environmental challenges [11,12,13]. In the 21st century, research on LULC change has become increasingly nuanced. Many in-depth investigations of LULC dynamics have revealed that LULC change profoundly impacts hydrological cycles [14,15]. Researchers have analyzed the influence of LUCC on carbon cycling [16,17], ecosystem service evaluation [18], global biodiversity [19], and land degradation [20]. Different LULC models and indicators have diverse scale effects, with regional LULC change affecting environmental factors at different spatial scales [21]. The evolution of LULC models has reached a critical phase in the comprehensive analysis of LULC change mechanisms and processes and the prediction of future development trends [22]. This approach has become instrumental in global LULC change research.

The largest oasis agricultural area in Xinjiang and China’s fourth-largest irrigated farming region [23]. The area has seen a dramatic increase in the local population and cultivated land area from 1949 to 2010, highlighting the economic growth. The region’s local population increased from 70,000 in 1949 to 1.1 million in 2010, an increase of 14.7 times, and the cultivated land area grew from 18,000 ha to 354,000 ha in the same period, an 18.6-times increase. The gross domestic product was CNY 34.552 billion, and the per capita GDP was CNY 31,411 in 2010 [24]. However, with the rapid economic and social development and the rapid increase in agricultural activities in the Manas River Basin from 2000 to 2020, the environment of the Manas River Basin has been adversely affected. In the past two decades, artificial oases encroached on the desert, and urban areas encroached on undeveloped land. The shift in LULC patterns in the watershed caused soil salinization [25], grassland degradation [26], climate change [27], and other environmental issues, posing significant threats to the basin’s ecosystems and sustainable development [28].

At present, most of the studies on the Manas River Basin focus on hydrometeorological changes and water resources management in the basin [29,30]. In terms of LULC change, Du et al. conducted a qualitative analysis of the current status of LULC change and its impact on landscape pattern change in the Manas River Basin from 1980 to 2020 based on ArcGIS and Fragstats software [24]. Li et al. analyzed the driving mechanism of LULC change in the Manas River Basin using grey correlation degree [31]. However, there is still a lack of quantitative analysis of the driving mechanism of LULC change in the basin. At the same time, in recent years, with the rapid economic and social development and the rapid advancement of urbanization, the fragile ecological environment of the river basin itself has further deteriorated. Therefore, it is very important to study the temporal and spatial evolution of land use in the Manas River Basin and quantitatively analyze the driving mechanism of land-use change to protect the ecological environment in the arid region and optimize the allocation of land resources.

We examine LULC change in the Manas River Basin from 2000 to 2020, using an LULC transfer matrix to track transitions between different LULC categories. We calculate the dynamic degree of LULC change and determine the factors affecting it. Advanced tools like the patch-generating land-use simulation (PLUS) model are used to quantify the contributions of various driving factors. The primary objective is to analyze the dynamic evolution of land use in the basin from 2000 to 2020, control the transformation between various land-use types, and to explore the driving mechanism of the conversion between various land-use types in the basin and give it quantitative analysis. It aims to provide theoretical basis and suggestions for ecological security and sustainable land development in the basin.

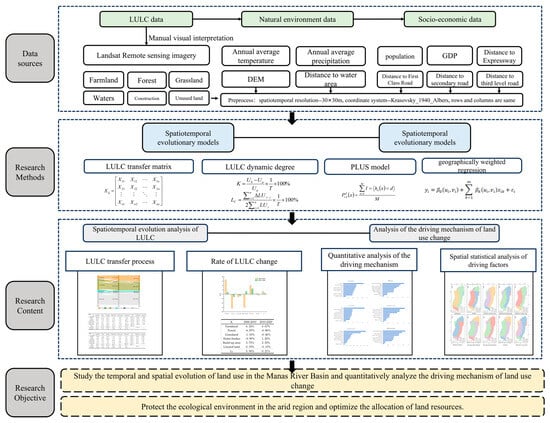

This understanding is critical for developing scientifically informed management policies for ecologically sensitive land and sustainable development strategies for the region. This research is also crucial in understanding LULC change dynamics and their implications on the environment and local community. It provides insights to help policymakers and stakeholders make informed decisions about LULC management in the Manas River Basin. Figure 1 illustrates the research framework of this study, including data sources, research methods, research content, and research objective.

Figure 1.

Research framework of this study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Research Area

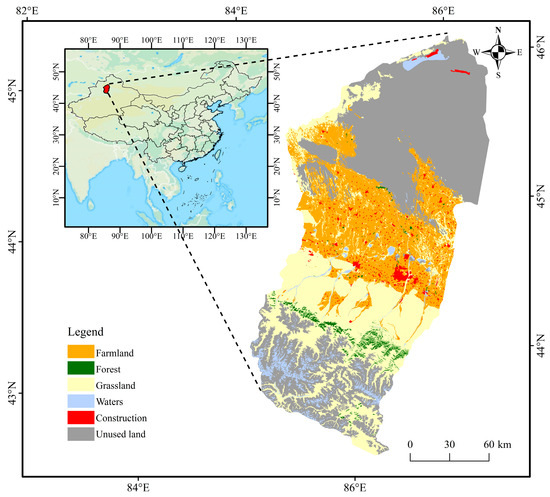

The Manas River Basin is located in the central part of the northern foothills of the Tianshan Mountains in Xinjiang, China, at the southern edge of the Junggar Basin (N43°27′–N45°21′, E85°01′–E86°32′) (Figure 2). The basin has a drainage area of 34,050 km2 and encompasses Shihezi City, Manas County, Shawan County, and surrounding agricultural areas. Due to its significant distance from oceanic influences, the Manas River Basin has an arid and semi-arid continental climate. Most of the precipitation (70%) occurs in summer. The annual precipitation exhibits spatial variability, ranging from 450 to 600 mm in the mountainous regions to less than 200 mm in the plains [28]. The topography of the Manas River Basin is diverse. The area is a mountain–oasis–desert ecosystem. The area has mountainous regions, piedmont slopes, and desert areas from south to north, with distinct ecological and vertical differences [32]. The predominant land-cover types in the Manas River Basin are unused land, arable land, and grassland. A significant transformation in the LULC pattern has occurred in recent years due to intensified human activities. The largest changes include a substantial expansion in arable and construction land and a considerable decline in forested and unused land [33]. This rapid LULC change has caused environmental problems, including the contraction of wetlands, intermittent river flows, and secondary salinization.

Figure 2.

The location of the Manas River Basin.

2.2. Data Sources and Research Methods

2.2.1. Data Sources

We utilized LULC, socioeconomic, and environmental data, as shown in Table 1. The land-use dataset was provided by the Resource and Environmental Science and Data Center of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, which was generated based on Landsat image data and generated by manual visual interpretation with an overall accuracy of 94% [34,35]. The classification system uses a two-level classification system. The first level is divided into 6 categories, which are mainly divided into cultivated land, forest land, grassland, water area, construction land, and unused land according to land resources and their use attributes. The second level is mainly divided into 23 types according to the natural attributes of land resources. Geographical factors include the Euclidian distance to first-, second-, and third-level roads, expressways, and water areas. These factors were derived using ArcGIS software. Climatic factors included annual average temperature and precipitation data from meteorological stations in the Manas River Basin. Ordinary Kriging interpolation of the vector data was performed to obtain a raster layer.

Table 1.

Data sources.

Considering that this study is based on raster data, as well as the extent of the study area and the characteristics of the PLUS model, the spatiotemporal resolution is selected as 30 × 30 m, the coordinate system is Krasovsky_1940_Albers, and all the data are preprocessed in ArcGIS software to ensure that the data have the same number of rows and columns and coordinate system.

2.2.2. Research Method

- LULC Transfer Matrix

The LULC transfer matrix is a fundamental tool in system analysis that quantitatively describes the state transitions in a regional land system. It depicts the conversion of LULC types, enabling the analysis of structural changes in the region [36,37], as shown in Equation (1):

where Xij is the area of conversion from the i-th LULC type to the j-th LULC type, and n represents the LULC type.

- 2.

- LULC Dynamic Degree

We utilized LULC dynamics to quantify the change rate of LULC types in the Manas River Basin. This analysis encompasses a single and comprehensive LULC dynamic degree [38].

The single LULC dynamic degree [39] reflects the rate of change for a specific LULC type during the research period. It is denoted as K and calculated as follows:

where Ub represents the LULC area of a certain type at the end of the study period; Ua represents the LULC area of a certain type at the beginning of the study period; and T represents the study period, which is 10 in this study.

The comprehensive LULC dynamic degree [30] reflects the rate of change in all LULC types in the study area during the research period [40]. It provides an overall perspective on LULC change and is computed as follows:

where ΔLUi-j represents the absolute value of the area of conversion from the i-th LULC type to a non i-th LULC type; ΔLUi represents the LULC area of class i in the initial stage of the study; and T represents the research period, which is 10 in this study.

- 3.

- Patch-Generating Land-Use Simulation (PLUS) Model

The PLUS model is able to accurately simulate landscape patch-level changes for a variety of land-use types [41]. It uses rule-based mining based on the land expansion analysis strategy (LEAS) and a cellular automata (CA) model based on random seeds (CARS). This model enables the analysis of the factors affecting LULC change. We utilized the random forest classification (RFC) algorithm to analyze the impact of the factors on LULC change. This algorithm is robust to multicollinearity and extracts random samples from the dataset. It determines the probability of the k-type LULC type in cell i. The calculation formula is as follows:

where the value of d is 0 or 1, representing transitions to or from an LULC type. Moreover, d is 1 when other LULC types are converted to the k-type LULC types; d is 0 when other LULC types are converted to LULC types other than the k-type; x is a vector consisting of the driving factors; function I is an indicator function of the decision tree set; ∑ is the prediction type of the n-th decision tree of vector x; and M is the total number of decision trees.

- 4.

- Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR)

In the early days, spatial statistical analysis techniques mostly considered the relationship between spatial variables to be fixed from the perspective of global assumptions, and did not change with the change in spatial position [42]. This premise obviously violates the law of heterogeneity or nonstationarity of spatial relations in the real geographical world. Geographically weighted regression is a local linear regression method based on the modeling of spatial-change relationships [43]. It generates a regression model describing local relationships at each point of the study area, which can well explain the local spatial relationships and spatial heterogeneity of variables. Therefore, we trained GWR in ArcGIS and plotted the regression coefficients of independent variables to describe the local association between land-use change and its influencing factors in the watershed.

We analyzed the major trajectories, dynamics, and determinants of LULC change in the Manas River Basin during the first two decades of the 21st century. Our results will support LULC planning and sustainable development in the region.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of LULC Transfer Matrix

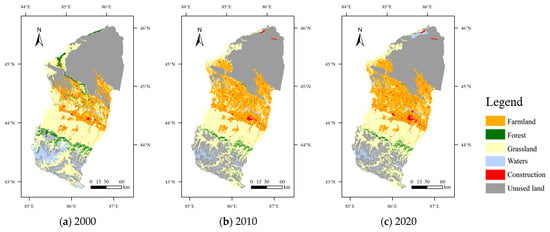

Figure 3a–c represent the land-use types in 2000, 2010, and 2020, respectively. They will provide a more detailed understanding of the spatial extent and patterns of change for LULC transfer analysis.

Figure 3.

LULC map of the Manas River Basin, 2000–2020. (Figure (a): Map of the Manas River basin in 2000, Figure (b): Map of the Manas River basin in 2010, Figure (c): Map of the Manas River basin in 2000).

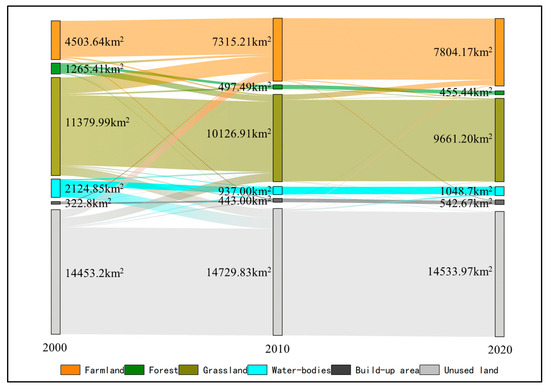

The land-use transfer in the basin from 2000 to 2010 is shown in Figure 4 and Table 2. Grassland experienced the most significant reduction from 2000 to 2010 (3222.08 km2), accounting for 39.64% of the total LULC change area. It was converted primarily to farmland (1870.72 km2) and unused land (1002.72 km2). Unused land showed the second-largest conversion area (2059.00 km2), accounting for 25.33% of the total conversion area. It was mostly converted to grassland (974.40 km2) and farmland (898.75 km2). Built-up areas exhibited the least changes, with only 131.55 km2 undergoing conversion, accounting for 1.62% of the total conversion area.

Figure 4.

LULC transfer matrix (2000, 2010, and 2020).

Table 2.

LULC transfer matrix of Manas River Basin from 2000 to 2010 (unit: km2).

Conversely, farmland exhibited the largest expansion (3126.77 km2), constituting 38.46% of the total conversion area. Most farmland was converted from grassland (1870.72 km2) and unused land (898.75 km2). Grassland had the second-largest expansion (1969.00 km2), equivalent to 24.22% of the total conversion area. The primary sources were unused land (974.40 km2) and forest land (652.18 km2). Water bodies exhibited the lowest degree of conversion (240.46 km2), accounting for 2.96% of the total conversion area.

The land-use transfer in the basin from 2010 to 2020 is shown in Figure 4 and Table 3. From 2010 to 2020, grassland experienced the largest reduction (697.26 km2), accounting for 51.01% of the total conversion area. The land was primarily converted into farmland (596.62 km2). Unused land experienced the second-largest reduction (288.44 km2), representing 21.10% of the total conversion area. The dominant sources were water bodies (177.50 km2). Interestingly, built-up areas experienced the least degree of conversion (20.16 km2), representing 1.47% of the total conversion area.

Table 3.

LULC transfer matrix of Manas River Basin from 2010 to 2020 (unit: km2).

Farmland had the largest land expansion (695.51 km2), accounting for 50.88% of the conversion area. The primary source was grassland (596.62 km2). Grassland experienced the second-largest expansion (232.85 km2), accounting for 17.03% of the total conversion area. The primary source was farmland (110.10 km2). Forest land had the smallest conversion area (35.45 km2), representing 2.59% of the total conversion area.

The area of forest and grassland showed a decreasing trend during the whole study period. However, it is worth mentioning that the area of forest land and grassland transferred to cultivated land from 2010 to 2020 decreased by 228.07 km2 and 1274.1 km2, respectively, compared with 2000 to 2010, effectively curbing the transfer of forest and grassland to cultivated land. Also, the decreasing trend of grassland area gradually slowed down, while the area of forest land was effectively maintained, indicating that the project of returning farmland to forest and grassland in the river basin during this period had great benefits. The water area showed a trend of first decreasing and then increasing throughout the study period. Specifically, the area of water loss to unused land from 2000 to 2010 reached 1257.49 km2, while the area of water loss to unused land from 2010 to 2020 was only 48.66 km2. The arid natural conditions of the basin have led to a large loss of water resources in the basin, but it has gradually been restored under the national water resources protection and other policies.

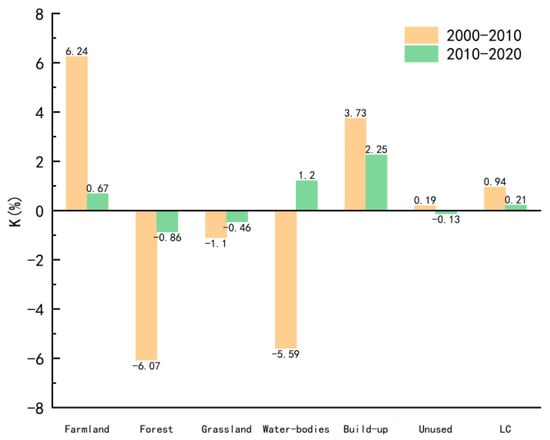

3.2. Analysis of LULC Dynamics

This study analyzed LULC change in the Manas River Basin from 2000 to 2020. The LULC dynamic degrees of the Manas River Basin from 2000 to 2020 are shown in Figure 5 and Table 4. From 2000 to 2010, we observed expansions in farmland, built-up areas, and unused land, and reductions in forest land, grassland, and water bodies. Notably, farmland exhibited the most rapid increase in area, with a single LULC dynamic degree of 6.24%. Forest land experienced the most rapid increase in area, with a single LULC dynamic degree of −6.07%. Water bodies also showed a considerable reduction in area (−5.59%), highlighting a relatively rapid loss during this period. This decade’s comprehensive LULC dynamic degree was 0.94%.

Figure 5.

LULC dynamic degree of the Manas River Basin.

Table 4.

LULC dynamic degree of Manas River Basin.

In the subsequent decade (2010–2020), the trend changed slightly, with increases in farmland, water bodies, and built-up areas, and decreases in forest land, grassland, and unused land. The most accelerated growth was seen in built-up areas, with a dynamic degree of 2.25%. Conversely, forests decreased, but at a slower rate, with a dynamic degree of −0.86%. The comprehensive LULC dynamic degree was 0.21%.

A comparative analysis between the two periods revealed that LULC change was more pronounced from 2000 to 2010 than from 2010 to 2020, with a difference of 0.73% in the comprehensive LULC dynamic degrees. Farmland and built-up areas consistently increased in both periods, although at a lower rate. In contrast, forest land and grassland continued to decrease gradually. The dynamic degrees of these land types differed significantly. The growth rate dropped from 6.24% to 0.67%, and the decline in forest areas decreased from −6.07% to −0.86%. Notably, the water areas’ dynamic degree shifted from a decrease of −5.59% in the first decade to an increase of 1.20% in the second. This change can be likely attributed to environmental initiatives, such as converting farmland back to forest and other ecological conservation measures.

3.3. Analysis of Driving Forces of LULC Change

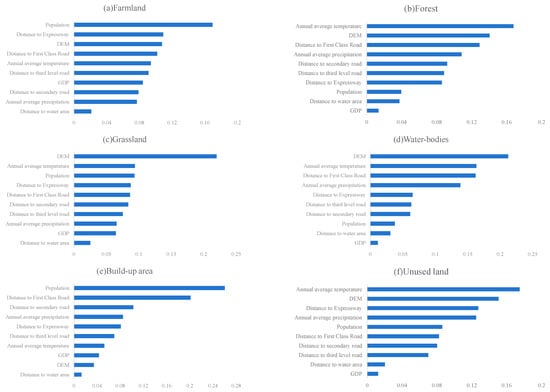

3.3.1. Quantitative Analysis of the Driving Mechanism of Each LULC Type

The PLUS model can explore the driving factors of land expansion and landscape change, and use the random forest classification algorithm to explore the impact of each driving factor on different LULC changes, and quantitatively express them in the form of contribution. According to the principle of driver selection and reference to the relevant literature [44,45,46], this paper selects the main socioeconomic and natural environment driving factors that affect LULC change in the basin, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Drivers of LULC change in the Manas River Basin.

Based on the LULC-change data of the Manas River Basin in 2010 and 2020, the PLUS model can extract the expansion part of each LULC type of LULC-change data in these two periods and sample from it; the sampling method is set to random sampling, the sampling rate is set to 0.01, and the number of decision trees is set to 20, and the random forest algorithm is used to mine the expansion of each LULC type one by one [41,47]. At the same time, the processed driving factors were imported into the model, and a total of 10 driving factors were selected in this study, and the number of features was set to 10. The root mean square-error results of cultivated land, forest land, grassland, water area, construction land, and unused land derived from the model are 0.083, 0.038, 0.088, 0.043, 0.048, and 0.061, respectively, indicating that the data are more credible.

After the random forest algorithm in the PLUS model obtains the development probabilities of six LULC types, the driving forces of the expansion of each LULC type can be deeply explored, and the contribution of each driving factor to the expansion of the six LULC types during this period can be derived.

The data processed in ArcGIS were imported into the PLUS model to analyze the driving forces and their contributions to LULC change in the Manas River Basin from 2000 to 2020. This period exhibited significant differences in LULC, influenced predominantly by three factors for each land type. The contribution of each driver to cultivated land is shown in Figure 6a and Table 6. The primary drivers of change for farmland were population, proximity to expressways, and elevation, contributing 17%, 11%, and 11%, respectively. This finding underscores the complex interactions between demographic dynamics, accessibility, and topography in agricultural land utilization.

Figure 6.

Contribution of driving factors to LULC change in the Manas River Basin.

Table 6.

Contribution of driving factors to LULC change in the Manas River.

The contribution of each driver to forest land is shown in Figure 6b and Table 6. Annual average temperature, elevation, and distance to first-class roads contributed 17%, 14%, and 13%, respectively, to changes in forest. These findings highlight the sensitivity of forest land to climatic variations, topographical factors, and transportation infrastructure.

The contribution of each driver to grassland is shown in Figure 6c and Table 6. Elevation, annual average temperature, and population contributed 22%, 9%, and 9% to changes in grassland. This result suggests the dominant influences of topography and climate. They are compounded by human demographic factors, affecting grassland dynamics.

The contribution of each driver to waters is shown in Figure 6d and Table 6. Elevation, annual average temperature, and distance to first-class roads contributed 21%, 16%, and 16%, respectively, to changes in waters. It indicates the significant impact of topographical and climatic factors and human infrastructure development on aquatic ecosystems.

The contribution of each driver to construction is shown in Figure 6e and Table 6. As the changes in construction indicated, population dynamics and distance to primary and secondary roads contributed 26%, 20%, and 10%, respectively, to urban expansion. This result reflects the critical role of population growth and transportation networks in urban LULC patterns.

The contribution of each driver to unused land is shown in Figure 6f and Table 6. Annual average temperature, elevation, and distance to expressways contributed 17%, 15%, and 13%, respectively, to changes in unused land. These factors underscore the influence of climatic conditions, topography, and accessibility on utilizing unused land.

In summary, these results reveal the multifaceted interaction of demographic, topographical, climatic, and infrastructural factors on LULC change in the Manas River Basin over two decades, which is crucial to inform the region’s land management and sustainable development planning.

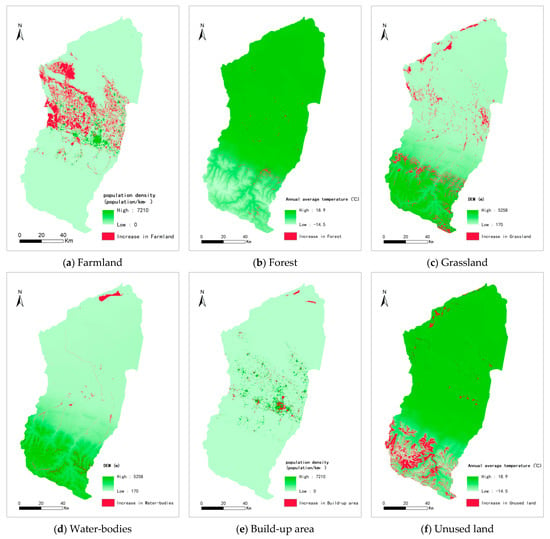

This study employed ArcGIS to overlay the most influential driving factors onto areas of increase for different LULC types to determine the correlation between the expansion and its principal driving forces.

Figure 7a shows numerous small farmland areas scattered around densely populated zones. Larger areas are at a moderate distance from the population centers, indicating an expansion close to these centers. Figure 7b indicates that forest expansion predominantly occurred in regions with elevated temperatures. A notable increase in forested areas occurred in mountainous terrain. In contrast, Figure 7c indicates a basin-wide increase in grassland area. The influence of elevation was negligible, which might be due to the small change and the lack of a trend. Notably, the downstream desert region exhibits no grassland increases. Figure 7d depicts a modest increase in water bodies, similar to the grassland trend with an insignificant elevation effect. The downstream Manas Lake expanded due to anthropogenic interventions during the study period. Figure 7e shows an increase in built-up areas in densely populated regions. These areas are scattered, and minimal expansion occurred in the remote downstream locations. Figure 7f demonstrates that increases in unused land occurred predominantly in the upstream mountainous regions with cooler temperatures. Small areas of increase occurred in other regions of the watershed.

Figure 7.

Increases in different LULC types and the dominant driving factors.

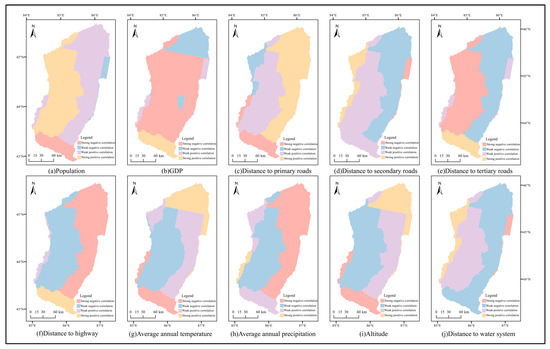

3.3.2. Spatial Statistical Analysis of Driving Factors

The GWR model was used to analyze the spatial statistical analysis of LULC drivers [48]. The results (Table 7) show that the R2 of the established GWR model is 0.983, and the calibration R2 is 0.928, which can better explain the response of spatial land-use change to each driving factor in the Manas River Basin.

Table 7.

GWR model-accuracy verification.

After the coefficient table was exported from the GWR model, the table was processed by ArcGIS to obtain a coefficient plot (Figure 8). It can be found that there are large spatial differences between natural environmental factors and socioeconomic factors on LULC change in the basin.

Figure 8.

Spatial distribution of factor-influence levels.

The results of the study on land-use change driven by natural factors show the following: In areas with a high degree of river basin development, such as Shihezi City and Karamay City, the influence of natural environmental factors on them is weak. However, it has a strong impact on the backward areas in the north and south of the basin, such as Hebuxel Mongolian Autonomous County and Hejing County. This may be due to the greater capacity of industrial cities to intervene in the natural environment. On the contrary, economically backward regions cannot rely on too much human intervention to avoid losses caused by temperature, precipitation, etc.

The results of the study on socioeconomic drivers of land-use change are as follows: The impact of the road on the northern and southern areas of the basin is more drastic, and the impact on the central part of the basin, such as Shihezi City and Manas County, is also severe. This may be due to the fact that the basin is facing large-scale industrial development and infrastructure transformation, and the social and economic development is relatively fast, which has a more obvious impact on local land-use change.

4. Discussion

This research utilized remote-sensing data to analyze LULC change in farmland, forest land, grassland, water bodies, built-up areas, and unused land in the Manas River Basin in 2000, 2010, and 2020. We used advanced remote-sensing techniques and ArcGIS for data processing and analysis, revealing significant LULC change over two decades. The dominant LULC types were farmland, forest land, and unused land. These observations are consistent with those of Gan et al. [49]. The area of cultivated land and construction land increased the fastest among all LULC types, which is consistent with the findings of Li et al. in Xinjiang [50]. The comprehensive LULC dynamic degrees from 2000 to 2010 were significantly higher than those from 2010 to 2020. It can be seen that the LULC change from 2000 to 2010 was very drastic, which is significantly related to the national policy of developing the western region implemented in 2000, and Shi et al. also found this in their ecosystem study of the arid region of Northwest China [51].

The areas of woodland, grassland, and water area decreased by 809.97 km2, 1717.49 km2, and 1074.98 km2, respectively, during the study period, and DEM and annual average temperature were the factors that had the greatest impact on these ecological lands. Li et al. identified natural factors (annual mean temperature, DEM, and average annual precipitation) as the main drivers of LULC change [52], which is consistent with our findings. It is undeniable that under the arid natural conditions of the basin, the natural environmental factors have a great impact on these ecological lands and are difficult to control. However, under the national policy of returning farmland to forest and grassland and protecting water resources, the managers of the Manas River Basin have deliberately protected the forest, grasslands, and water resources in the basin. From 2010 to 2020, the decline of forest and grassland area was significantly lower than that in 2000–2010, while the water area was slowly restored from 2010 to 2020. It can be seen that in the process of rapid urbanization, as well as under the requirements of the state to implement special protection of cultivated land and strictly abide by the red line of cultivated land protection, river basin managers must strictly implement the national policy of protecting ecological land. For example, the conversion of ecological space into urban or agricultural space requires strict approval, and illegal conversion within the ecological red line is prohibited. Focus on the restoration of ecological regions such as the Mushroom Lake Reservoir and the Dahaizi Reservoir. The upstream area of the river (mainly distributed in Shawan City) was horizontally compensated for the construction of water conservation forests. Through a combination of strict control, economic incentives, and legal responsibilities, efforts are made to achieve a balance between ecological protection and sustainable development of the river basin.

Our analysis of the driving mechanism of LULC change in the Manas River Basin differs from the prevailing approach, which typically considers that socioeconomic factors have a greater impact on land-use change than natural environmental factors [53]. Instead, we analyzed the driving forces for each LULC type separately, allowing for a separate analysis of each land type, making the study more nuanced. Due to data availability, the spatial resolution of this study is 30 m, and drivers such as politics and education are not considered, which limits the ability to perform a more detailed analysis of the core area of the watershed. At the same time, based on previous studies and combined with the current situation of land use in the Manas River Basin, this paper finally makes the PLUS model more accurate and the results more in line with reality through multiple adjustments of model parameters. However, relying on subjective parameter setting will affect the scientificity of model construction to a certain extent. Therefore, in future studies, more diverse data sources should be explored to address the inherent limitations of the data. At the same time, more effective parameter-setting methods should be further explored to make parameter setting more objective, cautious, and scientific. Such efforts will contribute to the development of a more precise and robust integrated research framework that will provide more scientific guidance and recommendations for the formulation of policies and programs in line with regional development objectives.

5. Conclusions

Grassland had the most significant land reduction (3222.08 km2) from 2000 to 2010. Most grassland was converted to farmland and unused land. Conversely, farmland experienced the most substantial increase (3126.77 km2), with grasslands and unused lands as sources. This trend persisted from 2010 to 2020, but the rate of change was lower. Grassland lost the most area (697.26 km2) due to conversion into farmland. Farmland exhibited the largest expansion (695.51 km2), with most land originating from grassland.

Farmland experienced the most rapid increase from 2000 to 2010, with a single LULC dynamic degree of 6.24%. Forest land had the largest reduction rate, with a single LULC dynamic degree of −6.07%. The comprehensive LULC dynamic degree was 0.94%. From 2010 to 2020, the built-up area increased the fastest, with a single LULC dynamic degree of 2.25%. Forest land had the largest area reduction rate (−0.86%). This decade’s comprehensive LULC dynamic degree was lower than it was in the previous period (0.21%).

Population growth was the dominant factor influencing farmland changes from 2000 to 2020, with a contribution degree of 0.17. Temperature had the largest effect on forest-land change (0.17). Elevation was the dominant factor affecting changes in grassland (0.21). Population growth contributed 0.26 to the transformation of built-up areas. Temperature was the leading factor impacting changes in unused land, with a contribution degree of 0.17.

The response of land-use change to the natural environment and social economy is more obvious in the less developed areas, while the land-use changes brought about by the natural environment can be effectively intervened and artificially controlled in the areas with a higher degree of development.

Our results underscore the need for a balanced approach that supports economic growth while preserving and protecting the fragile ecosystem of this vital area.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.L. and X.H.; methodology, P.L. and X.H.; software, P.L. and N.S.; validation, P.L., N.S. and M.A.F.; investigation, P.L.; resources, P.L., N.S. and X.H.; data curation, P.L.; writing—original draft preparation, P.L.; writing—review and editing, X.H., G.Y. and M.A.F.; supervision, X.H. and G.Y.; project administration, G.Y.; funding acquisition, G.Y. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52269006), Project of Shihezi (2023NY01), Projects of Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (2023TSYCCX0114, 2022BC001, 2022DB023, and 2023AB059), and the “Strategic Priority Research Program” of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. XDB0720301).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article. The data are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sun, S.; Chen, B.; Yan, J.; Van Zwieten, L.; Wang, H.; Dong, J.; Fu, P.; Song, Z. Potential impacts of land use and land cover change (LUCC) and climate change on evapotranspiration and gross primary productivity in the Haihe River Basin, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 476, 143729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Li, M.; Jing, C. Spatial Quantitative Model of Human Activity Disturbance Intensity and Land Use Intensity Based on GF-6 Image, Empirical Study in Southwest Mountainous County, China. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Liu, S.; Guo, L.; Zhang, J.; Feng, C.; Feng, M.; Li, Y. Evolution and Analysis of Water Yield under the Change of Land Use and Climate Change Based on the PLUS-InVEST Model: A Case Study of the Yellow River Basin in Henan Province. Water 2024, 16, 2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Qin, J.; Kayumba, P.M. Historic and Simulated Desert-Oasis Ecotone Changes in the Arid Tarim River Basin, China. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, T.; Kurtz, D. Maritime glacier retreat and terminus area change in Kenai Fjords National Park, Alaska, between 1984 and 2021. J. Glaciol. 2023, 69, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Feng, G.; Ren, J. Spatio-temporal evolution of land use and its eco-environmental effects in the Caohai National Nature Reserve of China. Sci. Rep. (Nat. Publ. Group) 2023, 13, 20150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Liu, B.; Wang, H.; Hu, M. Analysis of the Spatiotemporal Changes in Watershed Landscape Pattern and Its Influencing Factors in Rapidly Urbanizing Areas Using Satellite Data. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liesch, T.; Chen, Z.; Goldscheider, N. Global analysis of land-use changes in karst areas and the implications for water resources. Hydrogeol. J. 2023, 31, 1197–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Liu, J.; Liang, H. Simulation of Land-Use Changes Using the Partitioned ANN-CA Model and Considering the Influence of Land-Use Change Frequency. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathololoumi, S.; Saurette, D.; Gobezie, T.B.; Biswas, A. Land use change detection and quantification of prime agricultural lands in Southern Ontario. Geoderma Reg. 2024, 37, e00775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Guan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, F. Land Use/Cover Change and Its Relationship with Regional Development in Xixian New Area, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Huang, C.; Zhang, L. The Spatio-Temporal Patterns and Driving Forces of Land Use in the Context of Urbanization in China: Evidence from Nanchang City. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sang, C.C.; Olago, D.O.; Nyumba, T.O.; Marchant, R.; Thorn, J.P.R. Assessing the Underlying Drivers of Change over Two Decades of Land Use and Land Cover Dynamics along the Standard Gauge Railway Corridor, Kenya. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, C.E.S.; da Silva, M.V.M.; Rocha, S.M.G.; Silveira, C.d.S. Anthropic Changes in Land Use and Land Cover and Their Impacts on the Hydrological Variables of the São Francisco River Basin, Brazil. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhu, J.; Tian, Y. Impact of Land-Use–Land Cover Changes on the Service Value of Urban Ecosystems: Evidence from Chengdu, China. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2024, 150, 05024028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Luo, P.; Yang, H.; Li, M.; Ni, M.; Li, H.; Huang, Y.; Xie, W.; Wang, L. Land use and cover change accelerated China’s land carbon sinks limits soil carbon. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2024, 7, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Q.; Gao, J.; Yin, Y.; Guo, H. Future carbon storages of ecosystem based on land use change and carbon sequestration practices in a large economic belt. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 90924–90935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, P.; Zhang, S.; Wang, P.; Li, Y.; Huang, L. Evaluation and prediction of land use change impacts on ecosystem service values in Nanjing City from 1995 to 2030. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 18040–18063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Peng, Y.; Ren, Q.; Wu, J. Optimizing global protected areas to address future land use threats to biodiversity. Land Use Policy 2025, 154, 107560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Yang, L.; Chi, G.; Zeng, J. Ecosystem degradation or restoration? The evolving role of land use in China, 2000–2020. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Yan, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liang, L.e.; Xu, Z.; Guo, J.; Yang, R. Landscape pattern change and its correlation with influencing factors in semiarid areas, northwestern China. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 135837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.; Zhang, K.; Cao, L.; Guan, X.; Zhang, H. Driving forces and prediction of urban land use change based on the geodetector and CA-Markov model: A case study of Zhengzhou, China. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2022, 15, 2246–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, T.; Zhang, X.; Xia, F.; Zhang, Z.; Yin, J.; Wu, S. The Process-Mode-Driving Force of Cropland Expansion in Arid Regions of China Based on the Land Use Remote Sensing Monitoring Data. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; He, X.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Gu, X.; Yang, G.; Li, W.; Wu, Y.; Qiu, J. Changes in landscape pattern and ecological service value as land use evolves in the Manas River Basin. Open Geosci. 2022, 14, 1092–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Wang, X.; Xu, S.; Su, T.; Yang, Q.; Sheng, J. Soil Salinity Mapping of Croplands in Arid Areas Based on the Soil-Land Inference Model. Agronomy 2023, 13, 3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Fu, J.; Li, Y.; Li, Z. Attributing vegetation change in an arid and cold watershed with complex ecosystems in northwest China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 138, 108835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yang, G.; Tian, L.; Gu, X.; Li, X.; He, X.; Xue, L.; Li, P.; Xiao, S. Spatiotemporal variation in groundwater level within the Manas River Basin, Northwest China: Relative impacts of natural and human factors. Open Geosci. 2021, 13, 626–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Yin, X.; Zhu, H.; Zheng, X. Geographical Detector-Based Research of Spatiotemporal Evolution and Driving Factors of Oasification and Desertification in Manas River Basin, China. Land 2023, 12, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalfas, D.; Kalogiannidis, S.; Papaevangelou, O.; Chatzitheodoridis, F. Assessing the Connection between Land Use Planning, Water Resources, and Global Climate Change. Water 2024, 16, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorjsuren, B.; Batsaikhan, N.; Yan, D.; Yadamjav, O.; Chonokhuu, S.; Enkhbold, A.; Qin, T.; Weng, B.; Bi, W.; Demberel, O.; et al. Study on Relationship of Land Cover Changes and Ecohydrological Processes of the Tuul River Basin. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, J.; Du, Y.; Hou, X.; Xi, R.; Yang, Y. Assessing landscape fragmentation and its driving factors in arid regions: A case study of the Manas River, China. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 171, 113253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Li, X.; He, X.; Li, X.; Yang, G.; Li, D.; Xu, W.; Qiao, X.; Chen, L.; Lu, S. Multi-Scenario Simulation and Trade-Off Analysis of Ecological Service Value in the Manas River Basin Based on Land Use Optimization in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, N.; Gu, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, H.; Fan, Z. Analysis of Ecological and Economic Benefits of Rural Land Integration in the Manas River Basin Oasis. Land 2021, 10, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Qin, D.; He, X.; Wang, C.; Yang, G.; Li, P.; Liu, B.; Gong, P.; Yang, Y. Spatial and Temporal Changes in Land Use and Landscape Pattern Evolution in the Economic Belt of the Northern Slope of the Tianshan Mountains in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zhan, J.; Yan, H.; Shi, C.; Huang, J. Land Cover Mapping Based on Multisource Spatial Data Mining Approach for Climate Simulation: A Case Study in the Farming-Pastoral Ecotone of North China. Adv. Meteorol. 2013, 2013, 520813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ma, E.; Liao, L.; Wu, M. Land Use Change in a Typical Transect in Northern China and Its Impact on the Ecological Environment. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Gao, X.; Li, R. Research on the spatial temporary evolution of urban expansion in Xining city and its surrounding areas based on Landsat time series data. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Qi, Z.; Yan, H.; Yang, H. Variation Characteristics of Land Use Change Within the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Region During 1985–2022. Land 2024, 13, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Cheng, L.; Wang, Y. Measuring the Spatial Conflict of Resource-Based Cities and Its Coupling Coordination Relationship with Land Use. Land 2022, 11, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Ni, W.; Zhao, K.; He, Z.; Abuarab, M.E.-S.; Elbeltagi, A.; Ahmed, A. Temporal Dynamics of Ecosystem Service Value in Qinghai Province (2000–2018): Trends, Drivers, and Implications. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Guan, Q.; Clarke, K.C.; Liu, S.; Yao, Y. Understanding the drivers of sustainable land expansion using a patch-generating land use simulation (PLUS) model: A case study in Wuhan, China. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2021, 85, 101569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lim, B.; Lee, J. Analysis of Factors Influencing Forest Loss in South Korea: Statistical Models and Machine-Learning Model. Forests 2021, 12, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Luo, P.; Luo, L.; Zha, X.; Nover, D. Spatiotemporal characteristics and influencing factors of carbon emissions from land-use change in Shaanxi Province, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 123480–123496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Y.; Xue, M. Optimization and Simulation of Mountain City Land Use Based on MOP-PLUS Model: A Case Study of Caijia Cluster, Chongqing. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Liu, X.; De, T.; Liu, Z.; Yin, L.; Zheng, W. Forecasting Urban Land Use Change Based on Cellular Automata and the PLUS Model. Land 2022, 11, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hou, Y.; Li, F.; Zheng, B.; Chen, Z.; Zheng, F.; Zhang, X.; Yu, R. Land use change projection and driving factors exploration in Hainan Island based on the PLUS model. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1534508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Guo, W.; Xu, L.; Gao, C. Multi Scenario Simulation of Land Use in Chaohu Lake Basin Based on PLUS Model. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2025, 34, 1207–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G. Comparative Spatial Distribution Simulation of Plateau Mountain Cultivated Land Based on Spatial Multi-Scale Model, Yunnan Central Urban Agglomeration Area, China. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2023, 32, 3063–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.; Halik, Ü.; Shi, L.; Ru, J.; Wei, Z.; Li, J.; Welp, M. Integrating Multi-Source Data to Explore Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Future Scenarios of Arid Urban Agglomerations: A Geodetector–PLUS Modelling Framework for Sustainable Land Use Planning. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, C. Sensitivity assessment and simulation of ecosystem services in response to land use change in arid regions: Empirical evidence from Xinjiang, China. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 171, 113150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Shi, P.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, Y. Multi-Scenario Simulation and Driving Force Analysis of Ecosystem Service Value in Arid Areas Based on PLUS Model: A Case Study of Jiuquan City, China. Land 2023, 12, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Dong, B.; Gao, X.; Wang, P.; Ye, X.K.; Xu, H.; Ren, C. Land use change and driving forces in Shengjin Lake wetland in Anhui province, China. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 2021, 15, 042404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Jin, X.; Wang, F.; Yan, H. Analysis on landscape pattern change and driving force in Manas River Basin. Yangtze River 2016, 47, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.