Abstract

Digital transformation (DT) has become a strategic imperative for sustaining competitiveness in global supply chains. This study situates DT within the frameworks of Dynamic Capabilities Theory (DCT) and Structural Contingency Theory (SCT) to explain how leadership, culture, and institutional contexts shape adoption pathways in Brazil and Germany. Using a sequential mixed-methods approach, it combines a tertiary literature review with expert elicitation and Interpretive Structural Modelling (ISM), supported by DEMATEL and MICMAC analyses, to uncover hierarchical relationships among barriers and foundational technologies—Big Data Analytics (BDA), the Internet of Things (IoT), and cloud computing. The results reveal distinct causal structures: in Germany, workforce deficits and economic-risk perceptions act as root barriers that constrain managerial and cultural adaptation; in Brazil, executive sponsorship drives workforce capability and analytics development, activating subsequent IoT and cloud adoption. Across both contexts, BDA consistently emerges as the foundational enabler, indicating a layered sequence of capability accumulation. The findings demonstrate that effective digital transformation depends on leadership-enabled alignment between organisational structure and environmental contingencies. This study contributes a comparative framework linking DCT’s dynamic routines with SCT’s structural fit, providing theoretical, methodological, and policy insights for context-sensitive digitalisation strategies.

1. Introduction

Digital transformation (DT) in supply chains involves deploying interconnected technologies that integrate data, processes, and decisions across partners [1,2,3]. In industrialised economies such as Germany, DT initiatives are integral to Industry 4.0 (I4.0) policy frameworks, emphasising cyber-physical systems and smart manufacturing [4,5]. In emerging contexts, such as Brazil, adoption occurs amid infrastructural constraints and institutional volatility [6,7]. Understanding why trajectories differ requires analysis beyond technology readiness—leadership, organisational culture, and strategic fit [8,9,10].

DT combines three core technological layers: Big Data Analytics (BDA) provides the sensing capability to detect environmental shifts [11]; the Internet of Things (IoT) extends the seizing phase through connected sensing and actuation [12]; and cloud computing facilitates reconfiguration by scaling and integrating processes [13]. However, successful integration depends on human and structural factors—training, managerial vision, and cultural openness [9,14].

Recent global studies show adoption gaps. For instance, German manufacturers across automotive, machine engineering, and electrical engineering sectors report Industry 4.0 benefits, including competitiveness gains (cited by 80–90% of companies), financial improvements (70–80%), and enhanced overall equipment effectiveness (approximately 70%) [15]. In contrast, Brazilian manufacturing companies report partial digitalisation, with most Industry 4.0 implementations remaining at the pilot stage rather than achieving full-scale deployment [16]. These contrasts highlight the importance of investigating how structural contingencies and dynamic capabilities intersect to shape national adoption pathways [17,18].

Germany represents a coordinated market economy (CME), supported by institutional complementarities across education, labour markets, R&D networks, and corporate governance [19,20]. Brazil, in contrast, faces regulatory uncertainty, infrastructural gaps, and limited public incentives for digital and sustainability-related innovation, forcing firms to rely more on managerial agency than on institutional coordination [21]. This contrast operates as a natural experiment to examine how Dynamic Capabilities Theory’s (DCT) sensing–seizing–reconfiguring sequence varies under different structural conditions, as predicted via Structural Contingency Theory (SCT) [8,22] and mediated by national and corporate cultures and agency. It enables the assessment of whether capability-building pathways differ when institutional coordination is strong (Germany) versus when executive sponsorship substitutes for institutional support (Brazil), revealing the boundary conditions under which dynamic capabilities translate into performance outcomes [23].

This study addresses two research questions (RQs):

- Which barriers and foundational technologies most influence DT adoption across distinct national contexts?

- How do these elements interrelate to generate capability-building pathways?

To answer the RQs, this study integrates DCT—which explains the micro-foundations of capability evolution [22,23,24]—with SCT, which posits that organisational performance arises from the fit between structure and environment [8,10]. Leadership and culture are incorporated as mediators of this fit [9,10]. Methodologically, this study combines a tertiary literature review [25,26], an expert-based Interpretive Structure Modelling (ISM)/Decision-Making Trial and Evaluation (DEMATEL) model, and a Cross-Impact Matrix Multiplication Applied to Classification (MICMAC) [27,28].

Researchers have employed various Multicriteria Decision Model (MCDM) methods to study DT barriers. Mukherjee et al. [29] investigate organisational barriers to Industry 5.0 adoption in developing country contexts through a literature review, expert elicitation, and the application of the DEMATEL method. Kumar et al. [30] applied the SWARA-WASPAS method to prioritise barriers to implementing I4.0 in Indian manufacturing, suggesting the extension of this analysis to other sectors and countries. Luthra and Mangla [31] apply Explanatory Factor Analysis and the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) to analyse the main challenges to Industry 4.0 initiatives that impede supply chain sustainability in emerging economies from the perspective of the Indian manufacturing industry. Although research on digital transformation is expanding, studies employing a cross-country analytical approach remain relatively rare. Raj et al. [32] examined the barriers to technology adoption in manufacturing across developed and developing countries. Moreover, Szabo et al. [33] investigate the dynamics of digital transformation across companies in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), aiming to identify key drivers and challenges in the adoption of digital technologies.

This study advances the literature on barriers to technology and sustainability-oriented innovation in three ways. First, it addresses methodological fragmentation: Prior research employs heterogeneous barrier frameworks but fails to integrate hierarchical barrier structures with the sequential adoption of enabling technologies. Second, it strengthens theoretical applications by jointly employing DCT and Structural Contingency Theory (SCT), clarifying how leadership and organisational culture mediate technology deployment and sustainability outcomes. Third, it offers context-sensitive comparisons by contrasting coordinated and emerging market economies, overcoming the dominant binary classification of “developed vs. developing” countries and illuminating how structural, cultural, and institutional conditions shape technology adoption trajectories.

The contribution of this study is fourfold and offers the following:

- (i)

- A meta-theory integrating DCT and SCT via agency, leadership, and culture, explicitly addressing the inherent tensions between managerial agency (emphasised in DCT) and structural constraints (central to SCT) and demonstrating how leadership and culture mediate these tensions in digital transformation contexts.

- (ii)

- A methodological template for ISM-MICMAC modelling replicable in different settings.

- (iii)

- Policy guidance with respect to overcoming barriers in different contexts.

- (iv)

- A comparative mapping of barrier–technology relationships in Germany and Brazil, guiding practitioners with context-specific directions for sequencing technology adoption.

This study is structured as follows. After this Introduction, Section 2 describes the Materials and Methods. Section 3 presents the results, discussing the theoretical background of our research; outlining a meta-theory linking DCT, SCT, leadership, and organisational culture; and reviewing the DEMATEL-ISM-MICMAC analysis. Section 4 presents the findings, culminating in six research propositions and a meta-theory for DT, along with implications for practice and policy, limitations, and avenues for future research. Section 5 concludes this study.

2. Materials and Methods

This study expanded the exploratory work of Piovesan et al. [34], who investigated aspects related to barriers and base technologies. We present a new theoretical and conceptual approach that draws on a meta-theory combining DCT, SCT, organisational culture, and agency theories. Additionally, this study employs a multicriteria analysis method. ISM analysis is conducted because it offers a structured, hierarchical examination of the barriers and foundational technologies associated with digital transformation. Finally, previous research is expanded upon by offering a novel framework for I4.0 adoption and further exploring the barriers to DT.

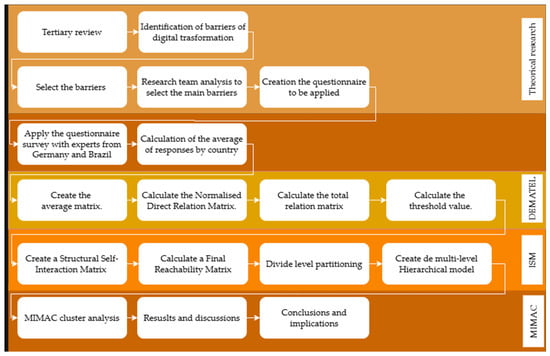

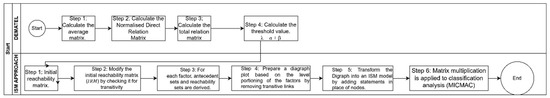

This study applies sequential methods research in four phases: (i) an exploratory tertiary analysis of the barriers to I4.0; (ii) a questionnaire for the quantitative analysis; (iii) an application of the questionnaire; (iv) a multicriteria analysis of barriers. The methodology’s phases are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Stages of the methodology.

2.1. Tertiary Review

The tertiary review followed the guidelines for systematic literature reviews (SLRs) provided by Thomé et al. [26] in seven steps. The Introduction presents the research planning and the formulation of the problem, which is step one of the SLR. Step two defines the terms and databases used for the searches: Scopus and Web of Science.

Only primary reviews were included in the tertiary review. Thus, according to Thomé et al. [26], the keywords that return literature reviews were used. Therefore, the keywords used were as follows: ((barrier*) AND (“digital transformation” OR “industry 4.0” OR “logisti* 4.0” OR “supply chain* 4.0”) combined with: AND (“research synthesis” OR “systematic review” OR “evidence synthesis” OR “research review” OR “literature review” OR “meta-analysis” OR “meta-synthesis” OR “mixed-method synthesis” OR “narrative reviews” OR “realist synthesis” OR “meta-ethnography” OR “state-of-the-art” OR “rapid review” OR “critical review” OR “expert review” OR “conceptual review”).

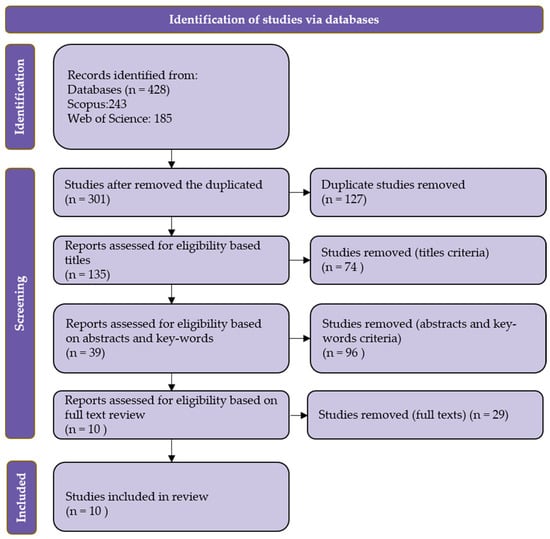

Searches were restricted to titles, abstracts, and keywords and limited to English-language articles and reviews, with no time limitation. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) was used to provide transparency for the search [25]. Figure 2 presents the PRISMA diagram.

Figure 2.

Study obtained from the PRISMA template. Adapted from [25].

In step three—data gathering—the barriers identified in the selected studies were extracted and grouped according to their frequency. The result was a list of 54 barriers. Guidelines from step four of Thomé et al.’s [26] outline refer to the quality evaluation of secondary data. Quality evaluation was ensured by including only peer-reviewed articles and reviews. Steps five and six—data analysis, synthesis, and interpretation—are described in Section 3, Section 4 and Section 5 of this study. Step seven, presenting results, corresponds to this study. Specific searches on seminal DCT, SCT, and agency theories complemented the SLR.

2.2. Data Collection, Classification and Sampling for Multicriteria Analysis

The panel of experts consisted of two phases: (i) a ranking scale of influence to select the main barriers, and (ii) a ranking of the barriers selected by experts in Brazil and Germany. Four digital transformation experts (Table 1)—each with published research on the topic—examined, refined, and confirmed the list of barriers and their underlying categories.

Table 1.

Expert experience in Industry 4.0.

The exercise identified eight barriers for multicriteria analysis. Table 2 summarises the barriers identified through tertiary analysis and selected from expert evaluation.

Table 2.

Barriers to Industry 4.0 Adoption.

These barriers were considered the main ones by the experts. A complete definition of the barriers is provided in Appendix A.

The questionnaire was developed through a multi-stage validation process. From the 54 barriers identified in the literature review, experts refined the list to 8 barriers (Table 2), which, together with three enabling technologies, structured the instrument. In addition to barrier evaluations, the questionnaire captured respondents’ experience with digital transformation, organisational affiliation, and professional background. Content validity was ensured through literature grounding, expert review (four specialists, Table 1), and the adaptation of established DEMATEL linguistic scales (Table 3). A pilot test with specialists (Table 1) confirmed clarity, completion time (~30 min), and consistency, resulting in minor wording adjustments. The survey entries were recorded electronically and scored, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Linguistic scale and corresponding values.

Based on the theory, purposive snowball sampling was adopted [42]. Respondents were selected to prevent the usual biases associated with this sampling method, including homophily (respondents with similar backgrounds), gatekeeping (informal selection based on individual criteria), and network bias (homogeneous groups originating from the same network) [43,44].

Participants from Brazil and Germany who worked in companies and academia were selected. This group consisted of recognised industry and academic experts. All experts consulted have extensive knowledge of digital transformation and technology adoption, with at least 5 years of experience in the field. The academics in the sample have researched topics related to digital transformation. The interviewed professionals work in companies transitioning to Industry 4.0. In total, 16 responses were obtained: 10 from respondents in Brazil (4 industry practitioners, 3 consultants, and 3 respondents affiliated with academic institutions) and 6 from respondents in Germany (4 academics and 2 industry professionals). A relatively small sample size is not uncommon in studies that rely on expert opinions [45,46], and similar sample sizes are frequently reported in the literature [28,29,32,35,47,48].

2.3. Interpretative Structural Modelling (ISM)

ISM is a modelling technique developed by Warfield [27] that has demonstrated wide application flexibility [49]. ISM organises the relationships among different elements of a complex system, creating a hierarchical structure based on their interdependencies, which aids in understanding how one element influences others [27]. Through the ISM approach, a set of distinct but interdependent elements influencing a system can be systematically structured into a comprehensive hierarchical model [50], allowing individuals or groups to develop a map of the complex relationships between elements involved in a complex situation [47]. Its basic idea is to use practical experience and expert knowledge to decompose a complicated system into several subsystems (elements) and build a multilevel structural model. ISM is often used to provide a fundamental understanding of complex systems—utilising practical experience and expert knowledge to decompose complex systems into subsystems (elements) and constructions—and to develop a course of action to solve a problem [47].

DEMATEL is an MCDM used to analyse and model complex cause-and-effect relationships among factors in a system [51]. Given the methodological convergence between DEMATEL and ISM, integrating both approaches can simplify the ISM-specific design process [52]. In this manner, DEMATEL was employed to construct the total relation matrix and the limit, which were subsequently utilised to calculate the structural self-interaction matrix (SSIM). The following steps of DEMATEL were used:

Step 1: Calculate the average matrix.

Step 2: Calculate the Normalised Direct Relation Matrix.

Step 3: Calculate the total relation matrix A.

Step 4: Calculate the threshold value.

The steps for the ISM method were as follows:

Step 1: Identification of variable factors.

Step 2: Initial reachability matrix (IRM).

Step 3: Modify the IRM by checking it for transitivity.

Step 4: For each factor, antecedent sets and reachability sets are derived.

Step 5: Prepare a digraph plot of the factor level portioning, removing transitive links.

Step 6: Transform the digraph into an ISM model by adding statements in place of nodes.

Step 7: Matrix multiplication for classification analysis (MICMAC) was performed to determine the factor dependencies, driver power, and key factors driving the system. Based on the factors of driver and dependence power, the MICMAC approach was adopted.

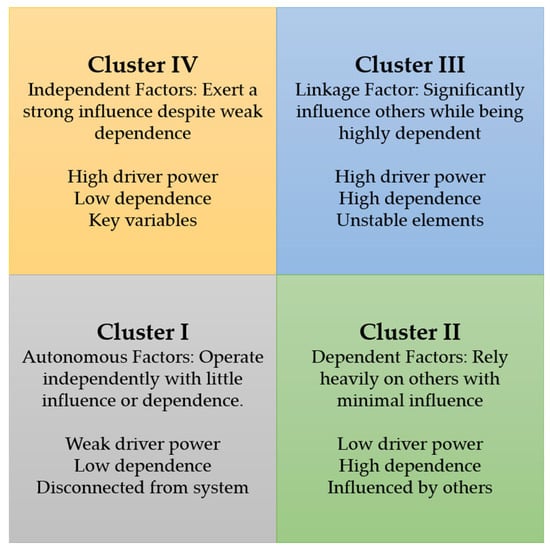

The MICMAC analysis classifies factors into four clusters, presented as follows [28]:

Cluster I: Autonomous Factors—These factors are relatively isolated from the system and have weak or no dependence power, and they also exhibit weak dependence power on other factors.

Cluster II: Dependent Factors—These factors are reliant on other factors and do not act independently.

Cluster III: Linkage Factors—These are unstable connecting factors that are mostly influenced by others.

Cluster IV: Independent Factors—Other factors have a weak influence on these; given the strong key factors, they require maximum attention.

Each step involves several calculations, which are presented in detail in Appendix B.

3. Results

This section is divided into three parts: the theoretical background, the meta-theory that guided the research, and the main findings.

3.1. Theoretical Background

3.1.1. Operations Management (OM) Theories Related to I4.0 Socio-Technical Skills

This study is grounded in DCT and SCT. Inspired by DCT, this study posits that the digital transformation initiated by I4.0 fosters dynamic capabilities [22], enabling competitive advantages. Based on SCT, performance gains would only be obtained when there is a fit among the context, structure, and outcomes [53]. Competitive markets favour established companies and create opportunities for newcomers. In new markets, customer needs, technological opportunities, and competitors’ activities constantly change [54]. To stay competitive, companies must maximise their capabilities and acquire new ones. Firms can innovate through incremental changes (exploitation) or radical new capabilities (exploration) [55]. Allying DCT and SCT premises emphasises the context-dependent nature of innovation.

The DCT is based on the Resource-Based View (RBV), which focuses on how unique resources create a competitive advantage [2,56]. While RBV highlights the importance of valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable resources, it faces criticism for being static in volatile markets [57], for resource immobility [58], for vague constructs [58], and for overlooking external factors [8]. By foregrounding the sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring of assets, DCT counters RBV’s alleged statism in turbulent contexts, mitigates assumptions of resource immobility through orchestration and redeployment, renders constructs more operational via identifiable routines and processes, and embeds external alignment by linking capability development to environmental dynamism and ecosystem interdependencies. Combining DCT and SCT generates a meta-theory that integrates internal and external factors, enhancing strategic positioning in volatile markets.

SCT asserts that performance results from the fit between organisational context (firm size, strategy, people, and technology) and structure, while misfit impairs performance [8,59]. Recent studies address SCT criticisms: structural adjustments to regain fit (SARFIT) help adjust the structure to regain fit [8]; other studies introduce dynamic fit [60], discuss the role of SCT expanded by information, agency, and stakeholders theories [61], and further explore the roles of agency and culture [9,62]. These authors expand on DCT, addressing the criticism that it is a static theory (firms would not change after their context–organisational form matches) [63]. The combination of DCT and SCT addresses various criticisms and provides context-dependent strategies. In this study, it is postulated that a meta-theory that extends the combined elements of DCT and SCT with corporate culture and agency theories provides a powerful lens for new research propositions on the subject. Corporate culture is understood by Schein [10,63] as the shared values a group uses to respond to external challenges and promote internal integration. It operates at both tangible (such as artefacts, norms, procedures, contracts, structure, and processes) and intangible levels (such as espoused values and deeply ingrained basic assumptions). It emphasises the overarching importance of SCT for an organisation’s structure, bringing values and behaviours to the forefront. Corporate culture also opens the avenue for a long-held criticism of SCT: the neglect of managerial agency [63] and the failure to consider that leaders often interpret facts, address them creatively, and guide strategies, rather than being mechanically guided by the fit between structure and organisational form.

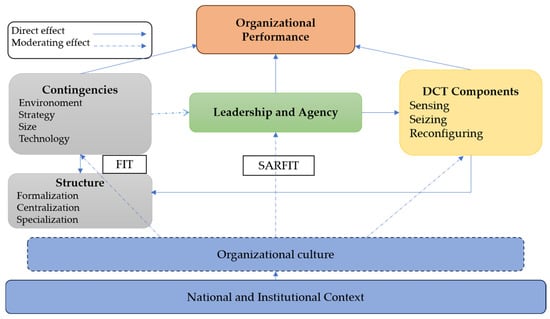

Figure 3 illustrates the complementarities between DCT and SCT.

Figure 3.

The complementarities between DCT and SCT.

According to Figure 3, DT performance would only happen if DC fits the context and organisational form. Performance improvements from DC arise either directly from a context–– structure––performance fit or indirectly through agency (leadership and management). The effects of fit and agency on performance are ingrained in specific national and corporate cultures, rendering innovation context-specific.

While prior research has applied DCT and SCT to organisational transformation, these frameworks are typically used as complementary yet independent lenses. Schilke [64] adopts a contingency view of dynamic capabilities, showing that their performance effects depend on environmental conditions. Likewise, Donaldson’s [8] SARFIT model demonstrates that structural adjustment is triggered by performance feedback, conceptually echoing the reconfiguration logic in DCT. However, existing studies either apply contingency logic to dynamic capabilities or treat structural adaptation primarily as a reactive process. Section 3.1.2 elaborates on the inherent tensions between agency and structure in these theories and demonstrates how leadership and culture operate as mediating mechanisms that translate environmental contingencies (SCTs) into capability development choices (DCTs).

For Teece [65], DC represents the skills, procedures, and structures that allow firms to sense opportunities, create value, and reconfigure resources in response to shifting environments. Overcoming barriers to digital transformation is key to enabling Industry 4.0 technologies to become a DC and foster competitive advantage. Eisenhardt and Martin [23] define DC as resources that facilitate or create market changes. DC allows companies to integrate, reconfigure, and renew resources to stay competitive [24,66]. Companies with DC reshape competition through innovation and business reconfiguration [22]. Digital technologies accelerate DC development, allowing companies to scale operations quickly and easily [67]. The decreasing cost of technologies, data flow, and reduced trade barriers compel companies to face agile competitors [65]. Companies develop dynamic capabilities through the following: (i) sensing or forecasting opportunities and threats; (ii) development involving the codification of insights and analysis beyond internal boundaries; and (iii) transformation through redesigning the internal and external environment [68]. While sensing and development capabilities help create opportunities, they are only fully realised when executed through organisational transformation. Without sufficient change, companies lose their DC [69]. A firm with DC fosters an agile, entrepreneurial mindset and extensive external networking [68].

DT begins with identifying technological possibilities and refining the business model to meet customer needs profitably [18]. Warner and Wäger [67] highlight enablers like cross-functional teams and agile decision-making, but barriers include rigid strategic planning, resistance to change, and hierarchical structures. Companies must also manage path dependence and overcome “lock-in” to established technologies and sunk costs [55,70]. Informal networks help detect new trends and instil digital mindsets, aligning strategic planning with long-term digital visions [67]. Companies need agility, flexibility, and an understanding of limitations to build dynamic capabilities. Redesigning internal structures to regain context-organisational form fit and enhancing workforce digital maturity is essential for effective DT [67].

This perspective becomes particularly relevant in the context of SCM in I4.0, where the integration of enabling technologies—such as BDA, the IoT, and cloud computing—enables unprecedented levels of visibility, adaptability, and collaboration.

Leadership and organisational culture serve as critical mediators in digital transformation. Leadership encompasses the managerial behaviours and cognitive capabilities that enable sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring resources [67,71]. It is operationalised through indicators of top management support, vision articulation, and empowerment mechanisms that facilitate cross-functional collaboration in digital projects.

Organisational culture represents the system of shared values, norms, and learning orientations that condition how employees interpret and respond to technological changes [10,71,72]. Culture is operationalised through Schein’s [10] tangible dimensions: rationality orientation, time horizon, motivation approaches, stability–change balance, production–social emphasis, collaboration patterns, control distribution, resource sourcing, and compensation methods. The theoretical mechanisms through which leadership and culture mediate DCT-SCT tensions are elaborated in Section 3.1.2.

Recent comparative digitalisation research underscores that leadership cognition serves as a central mechanism that translates environmental uncertainty into capability-building decisions [67,71]. National institutional arrangements and cultural logics shape leadership agency and digital transformation trajectories [32,72,73,74]. These empirical insights support the proposition that top management support in Brazil and structured decision-making in Germany represent context-specific expressions of the same underlying cognitive alignment process linking structural contingency and dynamic capability activation. The theoretical foundations underlying these mediating mechanisms are elaborated in the following section.

3.1.2. Theoretical Tensions and Complementarities: Reconciling Agency and Structure in Digital Transformation

While Section 3.1.1 established the complementarity of DCT and SCT, this section elaborates on their theoretical tensions and mediating mechanisms. SCT risks environmental determinism by emphasising context–structure alignment [8], whereas DCT underspecifies how institutional constraints condition the effectiveness of capability [64]. Their integration requires explicit mediating mechanisms operating between macro-structural contingencies and micro-level capability routines.

Leaders mediate the SCT-DCT tension by functioning as “structural interpreters”—diagnosing environmental contingencies while translating them into capability investments [67]. This cognitive mediation explains divergent strategies in similar contexts: a CEO’s risk framing determines whether structural constraints (e.g., labour availability) appear as insurmountable barriers or manageable challenges.

Culture operationalises the structure–agency link through learning orientations that either reinforce or challenge institutional norms [10,72]. When embedded cultures constrain experimental adoption (SCT rigidity), leading firms reconfigure culture itself as a dynamic capability by formalising innovation routines within existing risk parameters—illustrating how agency (DCT) reshapes structural constraints iteratively.

These mechanisms operate at three complementary analytical levels that reconcile longstanding theoretical tensions: (i) SCT (macro-level) specifies the contextual and structural conditions that bound organisational possibility sets, addressing prior determinism [8]; (ii) DCT (micro-level) describes capability-building routines and cognitive processes enabling action within those bounds, countering resource immobility [60]; and (iii) leadership and culture (meso level) translate macro-constraints into micro-level capability investments, thereby integrating agency with structural contingency [63]. This tripartite framework situates capability development within institutional contexts while preserving managerial discretion as the explanatory variable for divergent transformation pathways across national and organisational settings.

The following section analyses how SC transformation occurs when strategically aligned with dynamic capabilities.

3.1.3. SCM in I4.0 Era

The Fourth Industrial Revolution represents a change that is not only about smart, connected machines and systems but also encompasses a much broader scope. What makes this revolution distinct from previous ones is the convergence of these technologies and the interplay between the physical, digital, and biological domains [4]. Therefore, implementing the I4.0 vision will involve an evolutionary process that progresses at different rates across individual companies and sectors [5]. In SC, disruptive innovations are accelerating and strengthening operations [75], transforming traditional SCs into digital SCs.

The incorporation of digital technologies is a crucial strategic element for improving responsiveness, strengthening resilience, increasing transparency, and promoting the sustainability of supply chains [74]. Digital transformation in supply chains emerges from dual evolutionary forces. The first involves the maturation and deployment of enabling technologies, including cloud computing, sensors, cyber-physical systems, and the Internet of Things, which transition from research to operational implementation [76]. Simultaneously, rising expectations from supply chain stakeholders (suppliers, customers, and employees) compel organisations to enhance the reliability and responsiveness of their supply chain operations [76]. In the digital SC, each link can interact with all other points in the network, enabling connectivity between areas that previously did not exist.

However, the lack of technical skills makes companies unaware of the potential of these new technologies. The autonomous ability to plan, organise, and act, combined with the company’s and workers’ experience, is crucial for the organisation’s success [77].

In the early stages of transformation, companies tend to focus on individual technologies to improve operations [78]. Given the numerous existing technologies, SC faces challenges such as a lack of standardisation, rendering it difficult to choose the appropriate digital approach [40,79]. As a result, most SC still operate on a linear model, causing information delays and a lack of agility [80]. Thus, the digital transformation towards a digital SC is still in its infancy [3].

A holistic approach to digital transformation in SC, grounded in a digital strategy and operating model, will lead to successful execution, fostering the development of capabilities and enhancing operational performance. Such a reinvented SC is a next-generation SC: smart, connected, and agile, with the customer at the centre. This SC is also the foundation of an innovative business that embraces constant technological change and profits from it [81]. The digitalisation of SC helps manage its complexity. Furthermore, it enhances market responsiveness by improving the flow of products and information, representing a key factor for supply chains to achieve a competitive advantage [81,82]. Consequently, the seamless integration of internal data, along with digital connectivity with suppliers, customers, and partners, is essential [83].

Building on this understanding, the next section explores I4.0 enabling technologies (BDA, the IoT, and cloud computing), examining how their strategic integration enhances visibility, automation, and real-time decision-making. This integration not only supports more agile and efficient operations but also strengthens the SC’s dynamic capabilities—enabling the organisation to spot opportunities, seize innovations, and continuously reconfigure resources.

3.1.4. Enablers of Digital Transformation

I4.0 digital technologies enable data integration [12], allowing information from different sources and locations to drive the production and distribution of goods and services [84]. The convergence of information and communication technologies with other technologies leverages digital transformation, even in traditional sectors such as manufacturing and agriculture [77]. Enabled technologies, such as BDA, cloud computing, and the IoT, are foundational. Table 4 presents the leading base technologies of Industry 4.0 considered by this study’s experts.

Table 4.

Technologies of Industry 4.0.

The experts considered these technologies to be the core digital infrastructure that enables real-time data acquisition, connectivity, and scalable processing capabilities, thereby supporting advanced applications such as cyber-physical systems, predictive analytics, and smart manufacturing. This appraisal is consistent with the extant literature in I4.0 [5,11,40].

3.2. ISM and MICMAC Analysis

For the ISM analysis, the model was structured into four layers, from root causes to direct barriers. The analysis produced two hierarchical models—one for Germany and one for Brazil—each comprising four levels (root, controllable, key, and direct). The root layer corresponds to systemic constraints, while controllable and key layers reflect managerial and technological domains [86]. Following Ni et al. [86], the analysis proceeds from the bottom to the top, including the root layer (level 4), the controllable layer (level 3), the key layer (level 2), and the direct layer (level 1). The ISM diagrams depict the path for DT’s roadmaps in each country.

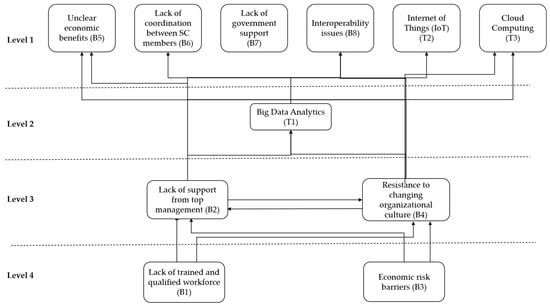

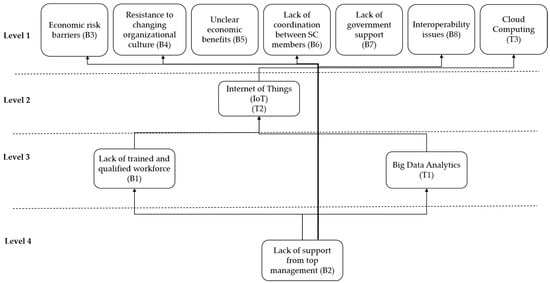

The MICMAC analysis reveals the driving and dependent factors in the cause-and-effect relationships among barriers. Figure 4 refers to the ISM results for Germany.

Figure 4.

Multilevel hierarchical structure model of barriers from Germany.

In Germany, root barriers include a lack of a trained and qualified workforce (B1) and economic and data security risks (B3), which influence the controllable layer (lack of top management support (B2) and resistance to changing organisational culture (B4). These, in turn, affect the adoption of BDA (T1) and other barriers, such as interoperability issues (B8), cloud computing (T3), and unclear economic benefits (B5). The analysis shows a mutual relationship between B2 and B4, where one barrier reinforces the other. Figure 5 refers to the ISM analysis for Brazil.

Figure 5.

Multilevel hierarchical structure model of barriers from Brazil.

Brazil’s model is centred on management support (B2) as the root cause influencing workforce development (B1) and analytics adoption (T1), which, in turn, affects IoT adoption and, subsequently, all other barriers. These results are confirmed by Sarkis et al. [87], who found that a lack of management commitment has a major influence on other barriers to technology adoption.

3.2.1. Germany: Capabilities, Risk, and Structural Integration

In Germany, skilled labour shortages persist across manufacturing sectors [35,37,88]. Although the nation ranks high in digital infrastructure, SMEs often lack data science competence, hindering the integration of analytics [14,82]. The expert panel identified B1 (workforce) and B3 (economic risk) as root drivers with strong influence scores.

Economic-risk perceptions are related to uncertainty in returns on digital investments and cybersecurity concerns [14]. For example, across German enterprises, perceptions of economic risk and unclear payback remain material constraints on digital investment. Chamber surveys highlight the financial burden and process complexity as leading obstacles (with 42% citing the financial outlay as a hurdle in 2024), indicating heightened scrutiny of return on investment before commitment [89]. BITKOM, Germany’s national digital industry association, provides further evidence of persistent barriers, including data protection, limited financial resources, a shortage of skilled workers, and insufficient time for day-to-day business activities. They observed that 64 per cent of the 600 companies responding to the BITCOM survey report that they lack sufficient funds to train employees on digital topics; 62 percent also lack the time for training, which aligns with a cautious approach to scaling the IoT and cloud [88]. Representative SME data points to weaker profit margins in 2022 and call for targeted financial incentives, both of which align with firms delaying or sequencing projects until ROI becomes clearer [90]. At the European level, the EIB Investment Survey reports that firms frequently perceive digital infrastructure as a major obstacle to investment, reinforcing a risk–return calculus in which uncertainty about benefits competes with tangible costs and execution risks [91]. Such perceptions discourage executives from funding training programmes, reinforcing B2 and B4 interdependence.

The controllable layer comprises top management support (B2) and cultural resistance (B4). German organisational culture—characterised by discipline, precision, and risk aversion—can slow experimentation [92]. However, structured learning cultures, such as those at Siemens, mitigate this through formalised innovation routines [5].

The key layer includes unclear economic benefits (B5) and interoperability issues (B8). Interoperability challenges stem from vendor-specific standards and legacy systems, particularly among suppliers [51].

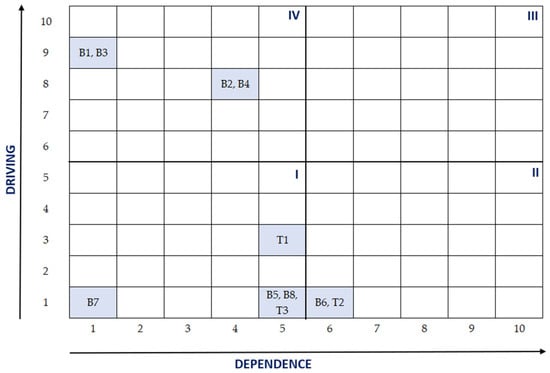

At the direct layer, technological deployment barriers such as limited IoT diffusion (T2) and cloud adoption (T3) appear. Figure 6 depicts the MICMAC of the cause-and-effect relationships among barriers in Germany.

Figure 6.

MICMAC barriers from Germany. Note: I: Autonomous factors; II: dependent factors; III: linkage factors; IV: independent factors.

The MICMAC analysis classified B1–B4 (lack of skilled workers, support from top management, and economic risk perceptions and resistance to change) as independent drivers with high driving power and moderate dependence; T1 (BDA), T3 (cloud computing), B5 (unclear economic benefits), B7 (lack of government support), and B8 (interoperability issues) were autonomous factors, operating independently with little influence or dependence, while B6 (lack of coordination in the SC) and T2 (IoT) were classified as dependent factors, heavily relying on others with minimal direct influence.

Quantitatively, management support showed an average driving score, whereas workforce readiness achieved a high score. The ISM reachability matrix (see Appendix B, Table A2) revealed bidirectional influence between B2 (management support) and B4 (organisational culture resistance), with both variables exhibiting identical structural characteristics—driving power = 8 and dependence power = 4—positioning them as linkage factors in MICMAC. This mutual causation (B2→B4 and B4→B2 both present in the matrix) indicates reciprocal reinforcement—an insight that aligns with the Leadership 4.0 literature [93]. An example is Bosch’s “Factory of the Future” programme. Bosch’s “Factory of the Future” exemplifies the causal chain whereby leadership-sponsored AI training builds workforce capability (B1), institutionalises data-driven routines (T1), and lowers perceived investment risk (B3) by demonstrating tangible operational gains. With risk mitigated and skills in place, the firm accelerated IoT deployment (T2) on the shop floor—validating the model’s sequencing from capability development to technology rollout [94].

3.2.2. Brazil: Managerial Agency and Institutional Challenges

Brazil’s structure diverged sharply. The ISM reachability matrix (see Appendix B, Table A3) identifies top management support (B2) as the dominant root driver, exhibiting the highest driving power (driving power = 9) and lowest dependence (dependence power = 1) in the entire system, shaping both workforce capability (B1) and analytics adoption (T1). The cultural and institutional environment amplifies the importance of leadership agency, as firms often operate under limited public incentives and volatile regulations [22,27,35].

Economic risk (B3) in Brazil relates not only to financial uncertainty but to exchange rate volatility and credit constraints, which reduce the appetite for long-term digital investments. Additionally, organisational culture (B4) tends to emphasise short-term performance over innovation [6].

At the key layer, interoperability (B8) and unclear benefits (B5) reflect fragmented IT infrastructures and weak metrics. Many Brazilian firms lack integrated ERP–MES connections (digital linkage between business planning and shop-floor operations), resulting in isolated analytics pilots. The direct layer includes challenges for IoT (T2) and cloud (T3) deployments.

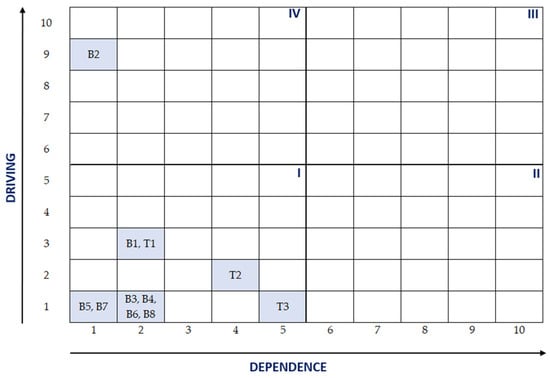

Figure 7 depicts the MICMAC of the cause-and-effect relationships among barriers in Brazil.

Figure 7.

MICMAC barriers from Brazil. Note: I—Autonomous Factors; II: Dependent Factors; III: Linkage Factors; IV: Independent Factors.

MICMAC analyses identified B2 (lack of support from top management) as the dominant independent factor with high driving power and low dependence. B1 (lack of skilled workers) and T1 (BDA) occupy intermediary positions, albeit with low driving scores, whereas other barriers exhibit weak connections. All factors except for B2 are regrouped in the autonomous factor’s quadrant, meaning that they operate independently with little influence on others and are heavily driven by top management support (B2).

Despite the yet incipient adoption of I4.0 in Brazil, there are examples demonstrating the models’ assertion of the strong causal influence of management support (B2) in overcoming the remaining barriers. In the energy sector, Petrobras’ Digital Twin initiative demonstrates partial progress in overcoming these barriers. Executive-level sponsorship facilitated the creation of interdisciplinary analytics teams, enhancing the predictive maintenance of offshore platforms [95,96]. Another case is WEG Industries, a Brazilian electrical manufacturer that developed a central analytics hub in Jaraguá do Sul. Management commitment (B2) drove cross-training programmes (B1) and subsequent IoT implementation (T2), as well as sustainability across factories [97,98]. Conversely, smaller suppliers without leadership support remain at early stages of digitisation [6].

3.2.3. Comparative Synthesis

Comparing both countries, three contrasts emerge:

Root Causality—Germany’s digital bottlenecks stem from skill deficits and economic risk; Brazil’s bottlenecks stem from leadership inertia.

Cultural Mediation—In Germany, resistance stems from procedural rigidity, while in Brazil, it arises from hierarchical decision-making.

Technology Sequencing—Both follow BDA → IoT → cloud trajectories, but with differing triggers (workforce vs. management).

Despite contextual differences, both models highlight leadership and learning as universal levers. When executives champion a data culture, barriers diminish irrespective of the environment.

4. Discussion and Theoretical Propositions

The comparative findings confirm that DCT and SCT alignment jointly explain how firms navigate digital transformation in heterogeneous institutional contexts. In both Germany and Brazil, the success of DT depends not only on technology readiness but also on leadership cognition, workforce learning, and structural adaptability [14,30,52]. However, the causal sequencing of these enablers varies systematically with context.

4.1. Theoretical Propositions

This analysis synthesises findings on digital transformation (DT) across Germany and Brazil, establishing a framework that links Dynamic Capabilities Theory (DCT) and Structural Contingency Theory (SCT). The six resulting propositions highlight that DT success is fundamentally contingent on contexts. The key findings demonstrate that leadership and organisational culture are critical alignment mechanisms (P1), that capability accumulation follows a layered technological progression (P2), that risk perception varies significantly between mature and emerging economies (P3), and that interoperability is a multilevel coordination challenge (P4). Ultimately, the transition to Industry 4.0 requires staged, culturally embedded investments (P5), and progress can be achieved through organisational self-reliance even when institutional support is limited (P6).

4.1.1. Linking DCT and SCT Through Leadership and Culture

The models demonstrate that leadership and organisational culture act as mechanisms of alignment, translating environmental complexity into structural adaptation [52,55,93]. In Germany, the tight coupling between workforce competence (B1) and managerial support (B2) shows that sensing and seizing are mutually reinforcing. Skilled labour allows leaders to recognise digital opportunities, while managerial commitment sustains investment in skill renewal [1,27].

In Brazil, where institutional volatility heightens uncertainty, leadership emerges as the initiating variable. Executives act as interpretive agents, bridging external turbulence and internal action [22,27]. This assertion reinforces the “agency–fit” dimension, which was absent in early SCT formulations [49,58].

Proposition 1.

Leadership cognition and national and corporate cultural openness mediate the alignment between context and structure in DT, thereby determining the activation of dynamic capabilities.

These findings extend Helfat and Peteraf’s [9] notion of managerial cognitive capability: In high-uncertainty contexts, leadership vision substitutes for structural stability. DT success thus depends on how effectively leaders interpret cues and embed them into reconfigurable processes [58,59].

4.1.2. Layered Capability Development

The hierarchical technology trajectory observed—BDA → IoT → cloud—illustrates how capabilities accumulate sequentially. Firms that develop analytics (sensing) first are better equipped to seize and reconfigure through IoT and cloud deployment [79,84].

In Germany, this pattern mirrors incremental innovation logics typical of coordinated market economies, where learning occurs through apprenticeship systems and formalised R&D [66,79]. In Brazil, a similar trajectory emerges through leadership-driven initiatives that compensate for institutional deficits.

Proposition 2.

The sequence of capability accumulation follows a layered progression from data sensing to operational seizing and structural reconfiguration, depending on agency, managerial intent, and institutional support.

Empirical examples reinforce this logic. Bosch’s Factory of the Future (Germany) exemplifies formal sensing structures, while WEG’s central analytics hub (Brazil) represents leadership-initiated sensing in emerging contexts [94,98]. Both demonstrate that analytics capability serves as the foundation for integrating the IoT and cloud.

4.1.3. Risk Perception and Economic Rationality

Economic-risk barriers (B3) surfaced as a root cause in Germany but a secondary issue in Brazil. German firms’ aversion to uncertain ROI reflects the rational calculation logic prevalent in mature economies [5,89]. Brazilian firms, conversely, perceive risk as endemic and normalise uncertainty [6,7,16].

Proposition 3.

Perceived economic risk moderates the pace of DT adoption differently across institutional contexts: rational risk management dominates in mature systems, while adaptive coping prevails in emerging ones.

This proposition aligns with Donaldson’s [8] contingency principle—fit is context-specific. It also resonates with Arndt and Pierce’s [60] argument that DC has evolutionary roots, conditioned by learning and behavioural heuristics.

4.1.4. Interoperability and Ecosystem Coordination

Interoperability (B8) was recurrently cited in both contexts, reflecting the need for ecosystem-level coordination [24,79]. However, its causes differ. In Germany, fragmentation arises from proprietary standards; in Brazil, it originates from infrastructural heterogeneity. The implication is that interoperability is both a technical and institutional construct.

Proposition 4.

Interoperability challenges arise from multilevel misalignments—technical, organisational, and institutional—that require collective governance mechanisms to resolve.

This view echoes Raj et al. [32] and Szabo et al. [33], who note that cross-country Industry 4.0 collaboration depends on regulatory convergence.

4.1.5. Technological Layering and Cultural Alignment

In Brazil, momentum typically originates with executive sponsorship that catalyses workforce upskilling and analytics adoption; in Germany, relief of skill bottlenecks and risk perceptions precedes broader cultural adaptation and managerial commitment. Against this backdrop, both contexts converge on a common sequencing logic for progressing from digitalisation to Industry 4.0.

Proposition 5.

The transition from digitalisation to I4.0 proceeds through incremental capability-building, driven by staged investment in T1–T3 (BDA, the IoT, and cloud) and sustained by a culture conducive to experimentation that results in performance gains. Prioritisation should reflect organisational scale, performance aims, and national cultural context.

This proposition is consistent with the layered, capability-first logic described in the I4.0 literature—where analytics foundations (T1) precede sensor-led operationalisation (T2) and cloud-enabled scaling (T3) [12,81,84]—and with DCT’s emphasis on sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring as cumulative routines [37,56,58,99]. Empirical studies of digital supply networks and Supply Chain 4.0 similarly underline that performance gains arise when technology adoption is sequenced and embedded in cultural enablers (learning, experimentation, and cross-functional teaming) rather than pursued as isolated deployments [76,79,93]. The call for contextual prioritisation by size, goals, and national culture aligns with SCT’s fit logic and with evidence on heterogeneous adoption pathways across countries and sectors.

4.1.6. Institutional Contingencies and Organisational Self-Reliance

Whereas Brazilian firms often compensate for thin or uneven policy support through leadership-led coordination, German firms—despite more mature infrastructures—may likewise advance DT with limited reliance on direct governmental levers when internal alignment is strong. This contrast underscores a shared regularity: progress is achievable under low-support conditions when internal fit and reconfiguration capacity are mobilised.

Proposition 6.

Where government support (B7) is non-influential, progress depends on DC mobilising to reconfigure assets autonomously in low-support institutional settings.

The proposition aligns with SCT’s core claim that performance hinges on an internally achieved fit between context and structure and with cross-country evidence showing that policy variability does not preclude firm-level progress when managerial agency and capability platforms are strong [34,35]. DCT further predicts that organisations can sustain transformation by recombining assets and routines even in resource-constrained or institutionally thin environments [37,58,62]. Studies on interoperability and governance reinforce that, absent external levers, firms that institutionalise leadership, data governance, and integration standards can continue to advance digitalisation autonomously, albeit at different speeds across ecosystems [79,93].

4.1.7. Integration into a Meta-Framework

The synthesis of these six propositions constitutes a meta-theoretical framework that integrates DCT and SCT in three complementary approaches. First, it enriches DCT by specifying previously implicit mechanisms—leadership as the enactment of sensing and seizing and culture as the substrate for reconfiguring—while establishing temporal logic (analytics precede connectivity, which precedes scalability). Second, it reconceptualises SCT by replacing static fit with dynamic fit achieved through managerial action, demonstrating how firms can overcome institutional voids through internal capability development. Third, it uncovers emergent phenomena unexplained by either theory alone: the necessity of ecosystem coordination for technological interoperability, the institutional construction of risk perceptions mediating adoption decisions, and the recursive relationship between organisational structure and culture in transformation processes.

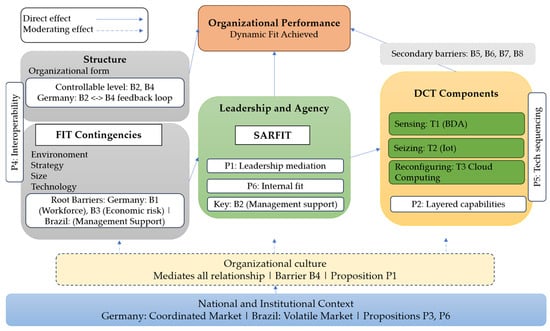

Figure 8 portrays a summary model of the theoretical propositions linking DCT, SCT, and barriers.

Figure 8.

The theoretical propositions in light of SCT and DCT.

This framework illustrates how DCT’s microfoundations (sensing–seizing–reconfiguring) function within SCT’s macro-alignment logic. The fit between context and organisational form directly enhances performance and has an indirect effect mediated by managerial action. Critically, this addresses the dual criticism that contingency theory neglects agency [100] and DCT overlooks contextual boundaries [9,62].

The findings are grounded in a contrastive institutional design between a coordinated market economy (Germany) and a large emerging economy (Brazil), maximising variance in labour–market coordination, investment logic, and risk governance. In coordinated economies, structural contingency dominates, as digital transformation depends on institutionalised skill systems and risk-averse investment norms. Conversely, in emerging economies with higher volatility, transformational leadership, and top management support become the primary drivers of dynamic capability activation in uncertain environments [67,73].

This meta-theory has clear boundaries. It is essential to clarify that the meta-framework’s transferability depends on institutional distance, governance maturity, and cultural dimensions influencing risk perception and decision centralisation. It applies most directly to economies with comparable coordination profiles—such as Japan or South Korea (coordinated) and India or Mexico (emerging)—but requires recalibration in hybrid or transitional contexts [72]. In low-coordination settings, structural mechanisms weaken, while leadership cognition and improvisational learning become more prominent. This fact delineates the model’s explanatory scope and defines necessary contextual adaptations, thereby establishing clear boundaries for this contribution to comparative digital transformation theory.

In addition, multinational corporations (MNCs) operating in both coordinated and emerging markets must navigate competing institutional logics, risk perceptions, and leadership norms when implementing digital transformation initiatives. In coordinated economies such as Germany, MNCs typically encounter structured industrial relations, a high reliance on codified processes, and institutionalised skill regimes that favour incremental capability-building. Successful strategies in this context emphasise collective learning, co-development with works councils, and alignment with vocational education systems [11]. Conversely, in emerging economies such as Brazil, MNCs face fluid institutional frameworks, lower alignment of formal skills, and greater volatility in policy and infrastructure. Here, dynamic capability development depends more strongly on transformational leadership, local empowerment, and adaptive governance structures capable of rapid sensemaking and reconfiguration [67].

This study emphasises that MNCs operating in both contexts must build ambidextrous integration mechanisms—balancing structural fit and leadership agency—to manage institutional duality. This adaptation requires transnational digital governance models that accommodate both standardisation and local autonomy. As Raj et al. [32] highlight, contextual barriers, such as risk perception, regulatory uncertainty, and workforce readiness, differ in salience across countries, necessitating tailored digital strategies. MNCs that succeed in integrating the process discipline of their German operations with the adaptive capacity of their Brazilian units can leverage what can be termed institutional complementarity: using stability in one context to underwrite experimentation in another. This practical extension directly follows from our comparative findings, clarifying how the meta-theoretical synthesis of Structural Contingency Theory and Dynamic Capabilities translates into actionable cross-contextual management guidance.

4.2. Implications for Practice and Policy

4.2.1. Managerial Implications

For managers, the findings highlight that digital transformation is primarily a leadership challenge rather than a technical one. In both Germany and Brazil, executive sponsorship catalyses the alignment of resources, culture, and skills. Firms should therefore institutionalise leadership for digitalisation programmes, linking strategic vision with technology governance [93].

Develop Analytics Before the IoT or Cloud: Organisations should first stabilise data pipelines and governance. A mature analytics base (T1) ensures that the IoT (T2) generates actionable insights rather than data overload [12].

Invest in Workforce Reskilling: Formal apprenticeship systems (e.g., Germany’s dual model) and partnerships with technical universities can bridge skill gaps [1,77]. In Brazil, public–private training consortia (e.g., SENAI–industry collaborations) could fulfil a similar role.

Embed Cross-Functional Teams: Leadership should foster collaboration among IT, operations, and supply chain functions to mitigate cultural silos [55,59].

Adopt Risk-Managed Pilot Portfolios: Following DCT’s seizing principle, firms can test digital initiatives in controlled settings to build confidence [58,99].

4.2.2. Policy Implications

For policymakers, this study suggests differentiated interventions.

In Germany, policy should prioritise SME digital enablement through tax incentives and standardisation frameworks to address interoperability [35,66]. The Mittelstand-Digital network exemplifies this approach through Centres of Excellence and digitalisation experts, delivering provider-neutral, free services, including workshops, pilot projects, and technology demonstrations [101,102,103]. These centres directly address the barriers identified in our ISM model: workforce skill gaps (B1) through hands-on training programmes; economic risk perceptions (B3) through tangible ROI demonstration; and interoperability challenges (B8) through standardisation frameworks [101,103]. The programme’s evolution to “Mittelstand Digital” reflects an expanded scope that encompasses resource efficiency and lifelong learning, and it addresses cultural adaptation barriers (B4) [101,102]. Complementary initiatives, such as the “Digital Jetzt” investment grants, mitigate economic risk barriers, accelerating the BDA→IoT→cloud technology sequencing observed in our findings [101]. This model brings together government, universities, and technology providers, yielding measurable productivity gains through capability-first interventions that prioritise skill development and risk mitigation [101,104].

In Brazil, focus should be on executive education and leadership development for digital governance, as managerial capability is the primary bottleneck [17,22].

Leadership oriented toward digital transformation requires a mindset focused on continuous innovation, learning, and decision-making in the face of uncertainty [105]. In this context, technical leadership in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) becomes a strategic driver of competitiveness, enabling complex decision-making and supporting structured digital transformation processes [106]. In Brazil, strengthening this profile is associated with expanding professional training and increasing the inclusion of women in STEM, thereby diversifying competencies and enhancing innovation capacity. Thus, developing STEM-oriented leadership constitutes an institutional strategy necessary for competitiveness and sustainable innovation [106]. Brazil’s policy response operationalises this leadership-centric approach through the “Brazil More Productive” programme, coordinated by the “Ministry of Development, Industry, Trade and Services” (MDIC) in partnership with the “National Industrial Learning Service” (SENAI), “Brazilian Micro and Small Business Support Service” (SEBRAE), “Brazilian Industrial Development Agency” (ABDI), “Financing of Studies and Projects” (FINEP), “Brazilian Industrial Research and Innovation Company” (Embrapii), and the “National Bank of Economic and Social Development” (BNDES), targeting 200,000 companies by 2027 with investments exceeding BRL 2 billion, which corresponds to about USD 370 million at current exchange rates [107,108]. SENAI’s adoption of the Smart Industry Readiness Index (SIRI) directly strengthens top management support (B2) by providing 1200 firms with executive-level readiness assessments and data-driven investment roadmaps [108,109]. The “Smart Factory” modality allocates about USD 30 million to Industry 4.0-enabling technologies—sensors, cloud computing, Big Data, the IoT, and AI—confirming the T1→T2→T3 sequence predicted by the framework [110]. Strategic partnerships with Nokia for Industrial IoT deployment and ServiceNow for AI skill training simultaneously address workforce capability gaps (B1) while strengthening the analytics foundation (T1) [111,112]. This structure focuses resources on leadership empowerment to fill institutional gaps, validating the leadership-driven pathway identified in the ISM model for Brazil.

These national programmes validate our comparative framework’s context-specific predictions. Germany’s Mittelstand-Digital demonstrates measurable productivity gains through distributed capability-building via vocational systems, addressing the root barriers (B1 and B3) identified in the model proposed in this study [101,113]. Conversely, the More Productive Brazil programme structures interventions around practitioners’ empowerment (B2) to drive workforce development and technology adoption, confirming the leadership-centric pathway revealed in the Brazilian model proposed [107,110]. Both programmes demonstrate that effective policy must align with context-specific barrier hierarchies rather than adopting universal solutions.

Both contexts would benefit from cross-national learning platforms, similarly to the EU’s Digital Innovation Hubs, linking academia, government, and industry [114]. Public incentives must be matched with absorptive capacity—training, governance, and data infrastructure—to prevent resource misallocation [14,34].

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

The expert panel approach (n = 16) represents a deliberate methodological choice appropriate for exploratory theory-building in complex systems [23]. However, this sampling strategy constrains statistical generalisability and warrants explicit discussion alongside validation pathways.

First, the purposive sample comprised ten Brazilian respondents (practitioners, consultants, and academics) and six German respondents (academics and professionals). Whilst multidisciplinary composition prevents homogeneity bias, the small sample size precludes parametric statistical inference; ISM/DEMATEL analysis reveals presumed causal hierarchies rather than validated mechanisms. Snowball sampling introduces selection bias, resulting in findings that reflect established expert networks rather than representative populations. The geographic restriction to two contexts limits transferability.

However, the sample size aligns with established expert elicitation practice. Studies employing ISM, DEMATEL, and similar methods typically utilise panels of 6–20 respondents [29,37]. Epistemic value rests on the depth of domain expertise and analytical rigour rather than on sample size alone [115]. The panel demonstrated a mean of six years of experience in digital transformation, with academic researchers providing theoretical grounding and practitioners ensuring operational validity. This composition supports theoretical saturation—the point where additional respondents yield diminishing returns [23].

Future studies should address these limitations through four complementary strategies: (i) large-scale surveys with structural equation modelling to test hypothesised relationships quantitatively [116]; (ii) longitudinal case studies to validate temporal sequencing and causal mechanisms, which capture non-linear dynamics and path dependencies that cross-sectional analysis cannot illuminate [117]; (iii) sectoral replication studies across manufacturing and service sectors to establish whether barriers are sector-contingent or sector-invariant, clarifying the applicability of the framework across industries [33]; and (iv) Bayesian network modelling to enable probabilistic quantification of conditional dependencies among barriers, providing richer representations of structural contingencies and interaction effects than binary ISM matrices [118].

Second, the analysis was confined to two countries. While Germany and Brazil provide instructive contrasts, cross-regional replication (e.g., Asia–Pacific and Africa) could test the model’s robustness under varying institutional conditions [35,94].

Third, this study focused on foundational technologies (BDA, the IoT, and cloud). Emerging enablers, such as blockchain, digital twins, and generative artificial intelligence (AI), warrant inclusion in future research, as they introduce new forms of interoperability and decision autonomy [79,91].

Fourth, longitudinal data could reveal how barriers evolve. Following Martinsuo and Hoverfält [61], a change in programme management capabilities may determine whether early pilots scale sustainably.

Fifth, while this study identifies distinct capability-building sequences and proposes six theoretical propositions, it does not systematically test the causal mechanisms explaining why these sequences differ. The DEMATEL-ISM approach maps structural relationships but cannot validate directional hypotheses. Future research should employ complementary methods to deepen the understanding of causality.

Sixth, the tertiary review’s restrictive search protocol yielded 10 systematic reviews, potentially excluding emerging or context-specific barriers from the broader literature. Future research could employ broader searches or primary studies to capture sector-specific obstacles (e.g., cybersecurity risks and ethical AI concerns).

Seventh, this study focused on three foundational technologies—Big Data Analytics, the IoT, and cloud computing. The evolving technological landscape now includes AI and machine learning, blockchain, digital twins, edge computing, and augmented reality [11]. Future research should investigate how these emerging technologies interact with the T1→T2→T3 pathway and whether they require different capability-building sequences or organisational prerequisites.

Future research should address the limitations of this study. In addition, it should expand its methods to validate the internal and external validity of our findings. Firstly, examining dynamic interactions among barriers using Bayesian network models would allow the quantification of feedback loops. Second, investigating the cultural transformation mechanisms that accelerate learning cycles across different contexts and company sizes could enhance the understanding of the relationships between corporate culture and digital transformation. Third, assessments of the impact of policy frameworks such as “Industrie 4.0” in Germany and “A More Productive Brazil” (for SMEs) could shed light on adoption trajectories and their impact. Finally, exploring how multi-tier supplier ecosystems internalise digital standards and certifications could boost innovation management.

5. Conclusions

This comparative study advances understanding of digital transformation in supply chains by demonstrating how barriers, leadership, and foundational technologies interact across institutional contexts. Integrating DCT and SCT through leadership and culture reveals that dynamic capabilities are both enablers and expressions of structural fit. In direct response to the research questions, the cross-country analysis shows that the most influential barriers are the lack of a trained and qualified workforce (B1) and economic risk (B3) in Germany and top management support (B2) in Brazil, with organisational culture (B4) and interoperability (B8) exerting secondary, context-contingent effects. Among foundational technologies, Big Data Analytics (T1) consistently emerges as the initial capability enabler, preceding the IoT (T2) and cloud computing (T3). These elements interrelate through a layered pathway of capability accumulation: in Germany, relieving B1/B3 unlocks managerial commitment and cultural adaptation, enabling T1→T2→T3; in Brazil, executive sponsorship activates workforce development and analytics first, which then propagate connectivity and scalability—together evidencing a dynamic fit between DCT-led capability building and SCT-aligned structural adaptation across distinct institutional environments. Nevertheless, despite the differences, both trajectories converge on a common sequencing logic: analytics first, connectivity second, and scalability third.

This study’s contribution is fourfold. It provides theoretical, methodological, policy, and practical contributions. Theoretically, our findings advance an integrated explanatory framework that reconciles the DCT sequence of sensing–seizing–reconfiguring with SCT’s context–structure fit, showing how capability development realises and renews fit over time. It extends this meta-framework by incorporating leadership and agency, as well as organisational culture, as operative mechanisms that translate environmental signals into structural and technological adaptations. It also offers one of the first structured cross-economy analyses jointly modelling barriers and base technologies, demonstrating how national context conditions lead to the activation of otherwise general mechanisms. Conceptually, this study reframes digital transformation as a layered pathway of capability accumulation—analytics, followed by connectivity and then scalability—suggesting the operationalisation of this sequencing logic.

Methodologically, our study employs ISM with DEMATEL/MICMAC logic to uncover interdependencies and causal hierarchies, providing a rigorous and replicable template for future comparative research. This study presents a comparative mapping of barrier–technology relationships across Germany and Brazil, linking eight barriers (B1–B8) to three foundational technologies (T1–T3) and offering an evidence-based basis for prioritising managerial and policy actions in distinct institutional settings.

It also offers policy-relevant insights on when external levers are peripheral and when standardisation or skills programmes can amplify firm-level readiness. Finally, it distils generalisable mechanisms for other settings. Although national entry points differ (skills/risk roots versus executive sponsorship), leadership-enabled learning and structural alignment consistently mediate movement along the T1→T2→T3 pathway, informing possible transferability beyond the two focal countries.

For practitioners, our findings isolate the most consequential levers—B1 and B3 in Germany and B2 in Brazil—while clarifying the context-dependent roles of B4 and B8, thereby indicating where attention should be directed first. This study provides guidance for technology road mapping—consolidate analytics before expanding the IoT and cloud and synchronise cultural enablers such as learning, experimentation, and cross-functional teaming.

This research advances United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 9—Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure—particularly Targets 9.2 (inclusive industrialisation) and 9.5 (industrial technology upgrading). By revealing how Germany and Brazil navigate distinct barriers through leadership-enabled capability building, this study offers actionable guidance for bridging the digital divide across institutional contexts.

Ultimately, sustainable digital transformation is less about deploying technology and more about orchestrating learning, leadership, and alignment across the organisational ecosystem. Future competitiveness will depend not merely on adopting digital tools but on embedding a sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring culture as part of continuous processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.D.P., A.M.T.T. and R.G.G.C.; methodology, L.D.P., A.M.T.T. and R.G.G.C. and R.S.S.; software, L.D.P., R.G.G.C. and R.S.S.; validation, A.M.T.T. and R.G.G.C.; formal analysis, L.D.P., A.M.T.T., R.G.G.C. and R.S.S.; investigation, L.D.P. and A.M.T.T.; data curation, L.D.P. and A.M.T.T.; writing—original draft preparation, L.D.P., A.M.T.T., R.G.G.C. and R.S.S.; writing—review and editing, L.D.P., A.M.T.T., R.G.G.C. and R.S.S.; visualisation, L.D.P. and A.M.T.T.; supervision, A.M.T.T. and R.G.G.C.; project administration, A.M.T.T.; funding acquisition, A.M.T.T. and R.G.G.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) [307777/2022-7]; [307173/2022-4]; [140672/2021-4]; [405734/2023-9]; [442384/2023-8]. Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) [Finance Code 001]; and the Foundation for Support of Research in the State of Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ) [E26-203.252/2017]; [E211.298/2021]; [E26-201.251/2021]; [E26/204.400/2024]; [E-26/201.363/2021]; [E-26/204.408/2024]; [E-26/210.562/2025].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (Protocol 154-2024 Proposal: SGOC534090 17 December 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DT | Digital Transformation |

| SCM | Supply Chain Management |

| BDA | Big Data Analytics |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| SC | Supply Chain(s) |

| DCT | Dynamic Capabilities Theory |

| SCT | Structural Contingency Theory |

| ISM | Interpretive Structural Modelling |

| DEMATEL | Decision-Making Trial and Evaluation Laboratory |

| MICMAC | Matrice d’Impacts Croisés Multiplication Appliquée à un Classement |

| I4.0 | Industry 4.0 |

| RQ | Research Questions |

| SLR | Systematic Literature Reviews |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| MCDM | Multicriteria Decision Model |

| RBV | Resource-Based View |

| SARFIT | Structural Adjustments to Regain Fit |

| DC | Dynamic Capability |

| CME | Coordinated Market Economy |

| MNC | Multinational corporation |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| STEM | Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics |

| MDIC | Ministry of Development, Industry, Trade and Services |

| SENAI | National Industrial Learning Service |

| SEBRAE | Brazilian Micro and Small Business Support Service |

| ABDI | Brazilian Industrial Development Agency |

| FINEP | Financing of Studies and Projects |

| Embrapii | Brazilian Industrial Research and Innovation Company |

| BNDES | National Bank of Economic and Social Development |

Appendix A. Definitions of Barriers to Industry 4.0 Adoption

Table A1.

Definitions of Barriers to Industry 4.0 Adoption.

Table A1.

Definitions of Barriers to Industry 4.0 Adoption.

| Barriers | Definition |

|---|---|

| Lack of Trained and Skilled Manpower | Workforce upskilling through structured training programs is crucial for maintaining current technical competencies. Effective technology implementation depends on having personnel with specialised capabilities [35,36,37,38]. |

| Lack of support from top management | Executive leadership may hesitate to champion Industry 4.0 initiatives owing to insufficient strategic foresight or capital constraints, resulting in inadequate coordination of organisational change both internally and across external partnerships. Rapid technological transitions demand robust executive sponsorship to enable workforce capability development, learning programs, and inter-departmental collaboration throughout the supply chain [32,37,38,39]. |

| Economic risk | Economic risk concerns arise from uncertain productivity gains, cybersecurity threats, significant transformation costs (including workforce and infrastructure), and doubts about whether financial returns will offset the implementation efforts [36,37,38,40]. |