Abstract

Cassava plants’ response to waterlogging must be monitored in an accurate and timely manner to mitigate the adverse effects of waterlogging stress. Under waterlogging conditions, root hypoxia reduces water uptake and stomatal closure limits transpiration, which often results in increased leaf temperature due to reduced evaporative cooling. However, how this relationship changes in cassava leaves under waterlogged conditions remains poorly understood. This study hypothesized that more negative ΔT values reflect enhanced transpirational cooling, which is a key determinant of superior physiological performance under waterlogging stress among cassava genotypes. Two cassava cultivars were subjected to twelve days of waterlogging. Results revealed a significant decrease in photosynthetic rate (p < 0.001), stomatal conductance (p < 0.001), and transpiration rate (p < 0.001), as well as an increase in leaf temperature (p < 0.001) and ΔT (p < 0.001), reflecting impaired stomatal regulation and reduced evaporative cooling. Strong negative correlations between ΔT and photosynthetic parameters (Pn (p < 0.001, r = −0.91), gs (p < 0.001, r = −0.91), and E (p < 0.001, r = −0.87)) were observed, presenting ΔT as a reliable, nondestructive indicator of cassava’s physiological responses under hypoxic conditions. Findings indicate that maintaining cooler canopies may contribute to waterlogging-tolerant cassava genotypes, and that ΔT can act as a screening parameter for waterlogging-tolerant genotypes. However, further studies with contrasting genotypes and additional parameters are recommended for validation.

1. Introduction

Understanding cassava’s physiological responses to waterlogging is essential for sustaining and improving food production in regions facing rapid population growth [1] and increasing climatic stress. In sub-Saharan Africa, the population is projected to increase by >120%. Within this region, cassava (Manihot esculenta) is the second-most important source of calories, providing ~30% of the daily dietary energy per person. Because of its starchy roots, cassava is widely used for starch extraction, animal feed, and feedstock production in China and other Southeast Asian countries [2]. Cassava is typically grown as an upland crop with a long maturation period of 8–12 months, which often overlaps with the rainy season. However, in West and Central Africa, it is preferred for inland valleys during the dry season, where it benefits from residual soil moisture [3]. Inland valleys, “as described by Andriesse et al. (1994), comprise the upper reaches of river systems, including valley bottoms, their hydromorphic fringes, and adjacent upland slopes [4]”. Because these valleys offer better water availability throughout the growing season compared to the surrounding uplands, they hold strong potential for intensified and sustainable land use [5].

Climate change is exerting a serious toll on human life, largely due to human activities [6]. To date, global mean surface temperature (GMST) has risen by ~1 °C and, if current warming trends persist, is projected to increase by 1.5 °C by 2050 and by 2 °C by the end of the 21st century [7]. These changes are expected to intensify the frequency of extreme climatic events (floods, drought, hailstorms, salinity, and heat stress) [6] and that will pose serious constraints to food production.

Among these stresses, waterlogging stress poses a particular threat. Once soils become saturated with water, root and microbial activity rapidly deplete oxygen in the rhizosphere [8]. Under anaerobic conditions, plants undergo various survival responses, including changes in physiology, anatomy, and morphology to adapt to the anoxic environment [9,10]. Waterlogging alters plant–water relations and carbon fixation at the physiological level. Leaf water content, which depends on root uptake capacity and leaf transpiration, is affected by such stress. “The work of Setter, T. et al. (2009) [11] indicated that waterlogging leads to a reduction in plant water content mainly due to the inhibition of root water uptake resulting from oxygen deprivation”. A reduction in leaf water content frequently influences physiological and metabolic processes within the leaf [12]. Leaf water deficits primarily influence the stomatal aperture, leading to reduced transpiration and gas exchange. Consequently, reduction in photosynthesis and transpiration rates associated with decreased leaf water content have been documented across several crop species, such as sorghum [13], maize [14], olives [15], and hibiscus [16].

Our previous study showed an 82.6% reduction in net photosynthetic rate (Pn) under waterlogging. This decline was attributed to a 96.7% decrease in stomatal conductance (gs) and a 21% reduction in transpiration rate (E). In the same study on three-month-old cassava plants, Pn, gs, and E deceased progressively with increasing waterlogging duration. In contrast, the SPAD value showed no significant change compared with the control across all observation periods, while Fv/Fm declined significantly three days after treatment but later recovered. This is likely due to increased energy dissipation rather than chlorophyll degradation, as SPAD values remained stable [17]. Overall, cassava exhibited a functional stay-green phenotype under waterlogging, which was characterized by stable SPAD values, maintained photosynthetic nitrogen use efficiency, and coordinated stomatal and non-stomatal regulation of photosynthesis [17].

Therefore, precise and timely monitoring of plant responses to waterlogging is essential to alleviate its detrimental impacts, particularly on cassava production [13]. “Blum A. J. et al. (1992) assessed canopy temperature in wheat and identified a strong correlation between canopy temperature and leaf water content [18]”. Leaf temperature is strongly associated with plant water status, as it is regulated by water loss through transpiration [19]. Under water deficit conditions, alterations in leaf water content and transpiration are often indirectly manifested through variations in leaf temperature [20]. Although a correlation exits between leaf water content and temperature, leaf temperature is additionally influenced by both transpiration rate and ambient air temperature [21]. Hence, the temperature differential between the leaf temperature and the surrounding air (ΔT) may serve as a more precise indicator of leaf water status than leaf temperature alone [22]. Elevated transpiration rates coupled with reduced stomatal conductance contribute to lower leaf temperatures [19], thereby resulting in a greater ΔT [23]. Thus, ΔT has been extensively employed as a tool for monitoring leaf gas exchange and water status. Wang, Zhang [13] further demonstrated that waterlogging reduces leaf relative water content (RWC), free water content, and leaf gas exchange parameters, while also inducing anatomical modifications, all of which are associated changes in leaf temperatures and ΔT. These results indicate that ΔT may serve as a reliable indicator of plant water status and photosynthetic adjustments under waterlogging. “According to Pineda M.M. et al. (2020) [24], the increases in leaf temperatures may be due to stomatal closure”. Stomatal closure is a non-specific plant defense response to both abiotic and biotic stresses. Elevated temperature may also arise from reduced evaporative cooling or vegetation loss [25]. In such cases, temperature increases are closely linked to limited transpiration caused by stomatal closure. Consequently, abiotic stressors such as drought, soil salinity, or extreme ambient temperatures are known to increase canopy temperature [24]. This is particularly important under natural conditions, where these stressors are difficult to quantify or control.

Moreover, leaf temperature measurement has been suggested as a cost-effective, indirect criterion for selecting plant genotypes with resistance to drought [19] and heat stress. However, its application to cassava, particularly under waterlogging conditions, remains unknown. Leaf temperature is indirectly associated with stomatal conductance and carbon exchange [26], and photosynthetic activity is influenced by elevated leaf temperature, either alone or in conjunction with drought, as a result of reduced stomatal conductance [27]. Furthermore, under suboptimal soil water conditions, higher ΔT and crop yield have been linked to increased stomatal conductance and enhanced water-use efficiency [28].

In extensively studied major crops and cereals, the relationship between leaf temperature changes and photosynthetic performance has been studied. However, this relationship changes remain poorly understood in cassava, particularly regarding anaerobic responses under waterlogging conditions. The objectives of this study were to (1) evaluate changes in leaf gas exchange, photosynthetic performance, and growth parameters in cassava during the early growth stage under waterlogging; (2) determine the relationship between leaf temperature, ΔT, and gas exchange parameters in cassava; and (3) elucidate the effects of waterlogging stress on leaf temperature and test the hypothesis that more negative ΔT values reflect enhanced transpirational cooling, which is a key determinant of superior physiological performance under waterlogging stress among cassava genotypes. Plants exhibiting cooler canopies are able to more effectively regulate stomatal conductance, resulting in lower leaf temperatures to ambient conditions [29]. Timely and precise monitoring of cassava leaf temperature, ΔT, and leaf gas exchange parameters can facilitate the development of strategies to mitigate waterlogging stress. This study aims to establish a novel approach for identifying waterlogging-tolerant genotypes to support future breeding programs. Our findings align with those of similar studies found online, with different crops (Sorghum) [13] and sources of stress (drought) [19] acting to reinforce ΔT utility as a nondestructive indicator of stress (waterlogging) response. The proposal of this index (ΔT) will enable a wide range of future research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Plant Materials

The study was performed in a greenhouse at Kagoshima University, Faculty of Agriculture, Japan. The average daily temperature and humidity values during the experimental period were 28.04 °C and 81.56%, respectively. Two cassava cultivars (Tokunoshima-white and Tokunoshima-yellow) were used; the two cassava cultivars were sourced from cassava grown at Kizuna farm in Tokunoshima, Kagoshima prefecture [30].

2.2. Experimental Design

Cassava stem cuttings (20 cm in length) were obtained from freshly harvested plants and immersed in a Hyponica nutrient solution (Kyowa Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) for 24 h to enhance shoot and root development. The treated cuttings were subsequently planted in small polythene bag containing sawdust as the propagation medium. After a 60-day growth period, six seedlings each per polyethene bag and per cultivar were selected based on their SPAD values and transplanted into small buckets containing a soil mixture of loam and sand in a 4:1 ratio (v/v). The transplanted seedlings were acclimatized for two weeks before the initiation of treatments.

A total of twelve buckets containing uniform cassava seedlings were selected for the experiment. Six buckets per cultivar were maintained under well-watered (WW) conditions by daily irrigation to field capacity with free drainage (control treatment), whereas the remaining six buckets were subjected to waterlogging (WL) by sealing the drainage holes and maintaining a water level of 3–5 cm above the soil surface. The treatments were applied for a period of 12 days. The experiment was arranged in a completely randomized design (CRD) with three replicates per treatment.

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Microclimate Data

The microclimate data, including average daily air temperature and relative humidity, as well as soil temperature and moisture content, were monitored using a sensor (5TE, METER Group Inc., Pullman, WA, USA) equipped with a data logger (RTR-503, T&D Corporation, Matsumoto, Nagano, Japan). The average daily air temperature and relative humidity were used to calculate air vapor pressure deficit (VPDair), using the formula: VPD = es (1 − RH/100). VPDair varied between 1.42 and 3.19 kPa (average 2.39 kPa). The average daily light in the greenhouse was measured at 8:00 am, 12:00 noon, and 4:00 pm using a light sensor (“Quantum sensor meter, apogee instrument” Inc., QMSS; Sun-13231, Logan, UT, USA).

2.3.2. Leaf Gas Exchange Parameters

A portable leaf gas exchange system (“LI-6400XT” Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA) was used for measuring Leaf gas exchange parameters, such as Pn, E, gs, and intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci), and leaf temperatures. Measurements were taken from the central leaflet of the youngest fully expanded leaf on one plant/replicate (n = 1) at 75 days after planting (DAP). Central leaflet of the youngest fully expanded leaf is physiologically an active leaf that minimizes variation due to leaf age. Prior to data collection, leaves were acclimated to a saturating light intensity of 1500 µmol m−2 s−1 and a CO2 concentration of 400 µmol mol−1 inside the cuvette until steady states for Pn and gs were obtained. The block temperature was maintained to 28 °C, with a vapor pressure deficit (VPD) corresponding to an airflow rate of 500 “µmol s−1.” Values of gs and Ci were obtained from the data points collected at 400 “µ mol−1,” (CO2). Photosynthetic water-use efficiency (PWUE) was calculated by dividing Pn by E at this same CO2 concentration, “while ΔT was calculated according to Jones, H.G. (1999) [31], using the following formula: ΔT = Leaf temperature − Air temperature.”

Leaf gas exchange parameters and leaf temperature were measured before treatment (0 DAT), then measured periodically at four-day intervals (4, 8, and 12 DAT) on the same plant leaves from three biological replicates per treatment on a clear day between 8:00 and 11:00 AM.

2.3.3. Chlorophyll Fluorescence (Fv/Fm) Measurement

AquaPen (“AP 100-P”, Photon Systems Instruments, Prumyslova, Drasov, Czech Republic) was used to measure Fv/Fm under dark adaptive conditions on fully developed leaves. Fv/Fm ratio, which is the maximum yield of PSII photochemistry, was obtained by applying actinic light through the instrument’s quantum yield protocol. Chlorophyll fluorescence measurements were carried out concurrently with leaf gas exchange assessments. Three replicates per treatment were used for Fv/Fm data collection. Fv/Fm were collected from three biological replicates per treatment at 0, 4, 8, and 12 DAT on the same plant leaves.

2.3.4. Soil–Plant Analysis Development (SPAD)

A SPAD meter (“SPAD502”; Konica Minolta, Tokyo, Japan) was utilized to record the SPAD values from three plants per treatment on the same day as the leaf gas exchange assessment. SPAD values were recorded at three consecutive positions along the leaf of the youngest fully expanded leaf of each plant. The same leaves used for chlorophyll fluorescence measurements were used for SPAD value measurement. SPAD values were measured at 0, 4, 8, and 12 days after treatment (DAT) on the same plant leaves from three biological replicates per treatment.

2.3.5. Morphological Data

Morphological data, including plant height, number of leaves per plant, and number of branches per plant, were counted. Plant height was measured from the base of the stem to the highest point of a shoot using a tape measure. The number of leaves per plant and branches was counted manually per plant for each treatment. These morphological data were collected at 0, 4, 8, and 12 DAT on the same plant from three biological replicates per treatment.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

All the data were subjected to Q-Q plot, Kolmogorov–Smirnvo, and Shapiro–Wilk tests of normality using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 30.0.0.0 [172]). The results showed normal distribution with few outliers in some data, and as a result, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was chosen. An ANOVA was conducted with IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 30.0.0.0 [172]) using a univariate analysis of variance to determine single and interaction effects of the treatment day interval (treatment duration) (D0–12) and treatment (WW and WL). The mean results of replicates per treatment were compared using “Turkey’s HSD test” at p < 0.05. Pearson’s correlation matrix analysis was conducted to test correlations between parameters using the multi-environment trial analysis package (“Metan”) V1,19.0 in R version 4.4.0. All results are presented as means of three replicates ± standard deviation.

3. Results

3.1. Growth Environments, Average Daily Temperature, Daily Percentage of Relative Humidity, Soil Temperature, Daily Soil Moisture Content, and Average Daily Light Intensity

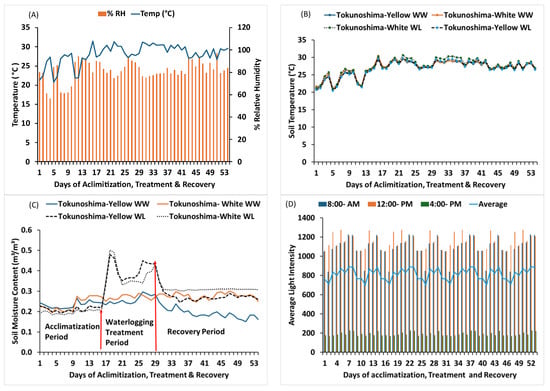

The temperature and relative humidity ranged from 20 °C to 31.5 °C and 56.0–97.0%, with an average of 28.0 °C and 81.6%, respectively, during the experimental period (Figure 1A). The average soil temperature for Tokunoshima-yellow cultivar buckets under WW and WL conditions was 20.7–30.0 °C and 20.5–29.8 °C, with averages of 26.8 °C and 26.8 °C, respectively. Meanwhile, the average soil temperature for Tokunoshima-white cultivar buckets under WW and WL conditions was 20.8–30.4 °C and 21–30.6 °C, with averages of 27.1 °C and 27.4 °C, respectively. The percentage difference between the WW and WL treatment buckets was 1.3% for the Tokunoshima-white cultivar and −0.01% for the Tokunoshima-yellow cultivar (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Average temperature and average relative humidity: (A) soil temperature, (B) soil moisture content, (C) and average light intensity (D) during experimental duration.

The average soil moisture content for the Tokunoshima-yellow cultivar under WW and WL conditions was 0.15–0.30 and 0.19–0.30 m3/m3, with averages of 0.22 and 0.26 m3/m3, respectively. The average soil moisture content for the Tokunoshima-white cultivar under WW and WL conditions was 0.15–0.30 and 0.19–0.30 m3/m3, with averages of 0.22 and 0.29 m3/m3, respectively. The percentage differences between the WW and WL buckets were 24.14% for the Tokunoshima-yellow cultivar and 10.34% for the Tokunoshima-white cultivar (Figure 1C). The average light intensity ranged from 840.5 to 1227.5 at 8:00 am, 1053.5 to 1274.5 at 12:00 noon, and 700.2 to 889.8 as the daily average (Figure 1D).

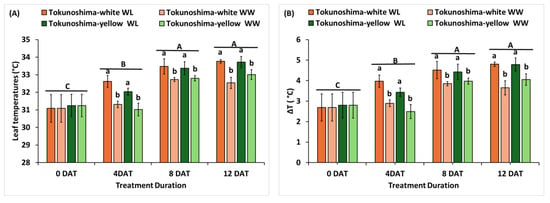

3.2. Effect of Waterlogging Treatment on Leaf Temperature and ΔT

The effects of waterlogging on leaf temperature and ΔT are presented in Figure 2A,B. The waterlogging treatment and waterlogging duration significantly affected leaf temperature and ΔT (p < 0.001); the interaction of treatment and waterlogging duration also significantly affected leaf temperature and ΔT (p < 0.01) (Table 1). Meanwhile, no significant difference was observed between the two cassava cultivars (Table 1). The leaf temperature of the two cassava cultivars increased immediately under waterlogging treatment at 4, 8, and 12 DAT compared to the WW condition (Figure 2A). The same trend was observed for ΔT in the two cassava cultivars (Figure 2B). The average leaf temperature increased by 27.2%, 14.7%, and 24.0% in the Tokunoshima-white cultivar and by 27.5%, 10.2%, and 15.3% in the Tokunoshima-yellow cultivar under WL conditions at 4, 8, and 12 DAT, respectively (Figure 2A). The average ΔT value increased by 3.2%, 1.7%, and 2.1% in the Tokunoshima-yellow cultivar and by 4.0%, 2.2%, and 3.6% in the Tokunoshima-white cultivar at 4, 8, and 12 DAT compared to WW conditions (Figure 2B). Additionally, the effects of leaf temperature and ΔT on cassava cultivars increased under WL conditions with the duration of treatment (Figure 2A,B).

Figure 2.

Effects of waterlogging durations on the leaf temperature (A) and difference in leaf and air temperatures (B) of two cassava cultivars. Uppercase letters above bars indicate significant differences between waterlogging durations, while those in lower case indicate differences among the waterlogging treatment. Bars are mean ± SD.

Table 1.

ANOVA results of the effect of waterlogging duration on morphological traits (plant height, number of branches, and number of leaves), photosynthetic traits (SPAD and Fv/Fm), and leaf gas exchange parameters (Pn, gs, E, Ci, and PWUE) of cassava cultivars at the early growth stage.

3.3. Effect of Waterlogging on Photosynthetic Traits (Pn, E, gs, and PWUE)

The immediate effects of waterlogging on the photosynthetic traits, Pn, E, gs, Ci, and PWUE, of the two cassava cultivars at the early growth stage are presented in Figure 3A–E. The Pn values of the two waterlogged cultivars displayed significant differences between treatment durations (p < 0.001), treatment (p < 0.001), and the interaction between treatment duration (TrtD), and waterlogging (p < 0.001) (Table 1). However, the two cultivars did not differ between treatments (Table 1, Figure 3A). The Pn values of waterlogged Tokunoshima-white and Tokunoshima-yellow cultivars decreased by 75.1% and 60%, respectively, compared to WW cultivars at 4 DAT. The Tokunoshima-yellow cultivar exhibited the largest reduction in Pn values by 99.9% at 12 DAT compared with the Tokunoshima-white cultivar (99.2%) (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Effects of various waterlogging durations on photosynthetic rate (A), transpiration rate (B), stomatal conductance (C), intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci) (D) and PWUE (E) at early growth stage of cassava cultivars. Uppercase letters above bars indicate significant differences between waterlogging durations, while those in lower case indicate differences among the waterlogging treatments. Bars are mean ± SD.

Similarly, the E values of the waterlogged cultivars displayed significant differences between TrtD (p < 0.001), waterlogging treatment (p < 0.001), and the interaction between duration and waterlogging treatment (p < 0.001) (Table 1). However, the cultivars did not differ among treatments (Table 1, Figure 3B). The E values of the waterlogged Tokunoshima-white and Tokunoshima-yellow cultivars decreased by 76% and 71%, respectively, compared to WW cultivars at 4 DAT. The Tokunoshima-white cultivar exhibited the largest reduction in E values by 96.8% at 12 DAT compared with the Tokunoshima-yellow cultivar (94.7%) (Figure 3B).

Additionally, the gs values of the waterlogged cultivars exhibited significant differences between TrtD (p < 0.001), waterlogging treatment (p < 0.001), and the interaction between duration and waterlogging treatment (p < 0.001) (Table 1). However, the cultivars did not differ among the treatments (Table 1, Figure 3C). The gs values of the waterlogged Tokunoshima-white and Tokunoshima-yellow cultivars decreased by 82% and 82.8%, respectively, compared to WW cultivars at 4 DAT. The Tokunoshima-white cultivar exhibited the largest reduction in gs values by 97.8% at 12 DAT compared with the Tokunoshima-yellow cultivar (96.2%) (Figure 3C).

The Ci values of the waterlogged cultivars displayed a significant difference between TrtD (p < 0.05) and the interaction between TrtD and waterlogging treatment (p < 0.01) (Table 1). However, the waterlogging treatment did not have a significant impact on Ci, and the cultivars did not display differences among treatments (Table 1, Figure 3D). The Ci values of the waterlogged Tokunoshima-white and Tokunoshima-yellow cultivars decreased by 13.8% and 47.9%, respectively, compared to WW cultivars at 4 DAT, which corresponded to their largest reduction in Ci values (Figure 3D).

The PWUE values of the waterlogged cultivars displayed a significant difference between TrtD (p < 0.01) and the interaction between TrtD and waterlogging treatment (p < 0.001) (Table 1). However, the waterlogging treatment did not display a significant difference, and the cultivars did not differ among treatments (Table 1, Figure 3E). The PWUE values of waterlogged Tokunoshima-white and Tokunoshima-yellow cultivars increased by 60.1% and 28.1%, respectively, compared to WW cultivars at 4 DAT. The Tokunoshima-yellow cultivar exhibited the largest reduction in PWUE values by 99.1% at 12 DAT compared with the Tokunoshima-white cultivar (71.8%) (Figure 3E).

These results revealed that the effects of WL treatment on the Pn, E, gs, Ci, and PWUE values of two cassava cultivars at the early growth stage increased with the waterlogging duration (Figure 3A–E).

3.4. Effect of WL Treatment on Photosynthetic Traits (SPAD and Fv/Fm)

The immediate effects of WL treatment on Fv/Fm and SPAD values of cassava cultivars at the early growth stage are presented in Figure 4A,B. The Fv/Fm values of the two cultivars were significantly affected by WL treatment (p < 0.001) and TrtD (p < 0.05) (Table 1). Additionally, the interaction between TrtD and waterlogging treatment significantly affected Fv/Fm (p < 0.05) (Table 1). The cultivars did not differ between treatments (Table 1, Figure 4A). The Fv/Fm values of the WL Tokunoshima-white and Tokunoshima-yellow cultivars decreased by 0% and 4.6%, respectively, compared to those of WW cultivars at 4 DAT. The Tokunoshima-white cultivar exhibited the largest reduction in Fv/Fm values by 7.6% at 12 DAT compared with the Tokunoshima-yellow cultivar (3.4%) (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Effects of various waterlogging durations on Fv/Fm (A), SPAD values (B), at early growth stage of cassava cultivars. Uppercase letters above bars indicate significant differences between waterlogging durations, while those in lower case indicate differences among the waterlogging treatments. Bars are mean ± SD.

The SPAD values of the two WL cultivars displayed significant differences between TrtD (p < 0.01), waterlogging treatment (p < 0.05), and cultivars (p < 0.001) (Table 1, Figure 4B). However, the interaction between TrtD and WL treatment did not statistically differ from the WW treatment (Table 1, Figure 4B). The SPAD values of WL Tokunoshima-white and Tokunoshima-yellow cultivars decreased by 2.8% and 10%, respectively, compared to WW cultivars at 4 DAT. The Tokunoshima-yellow cultivar exhibited the largest reduction in SPAD values by 14.4% at 8 DAT compared with the Tokunoshima-white cultivar (10.3%). The effects of WL treatment on Fv/Fm and SPAD values of the two cassava cultivars at the early growth stage increases with the TrtD (Figure 4A,B).

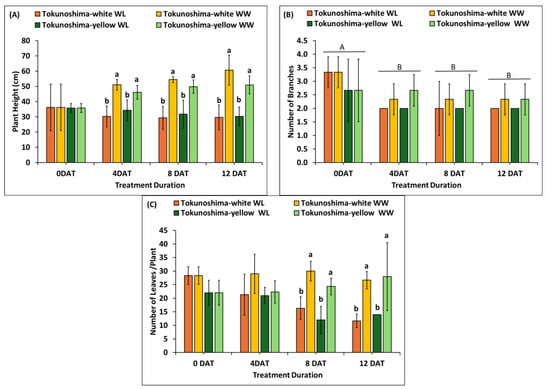

3.5. Effect of WL Treatment on Morphological Traits (Plant Height, Number of Branches, and Number of Leaves)

The immediate effects of various WL treatments on plant height, number of branches, and number of leaves of cassava cultivars at the early growth stage are presented in Figure 5A–C. The plant height of the two cultivars was significantly affected by WL treatment at 4 DAT (p < 0.001), 8 DAT (p < 0.03), and 12 DAT (p < 0.01), respectively (Table 1). However, the TrtD did not significantly affect plant height (Table 1). In contrast, the interaction of TrtD and waterlogging treatment had a significant effect (p < 0.01) (Table 1). The plant heights of WL Tokunoshima-white and Tokunoshima-yellow cultivars decreased by 40.5% and 25.5% at 4 DAT, respectively, compared to WW cultivars. The Tokunoshima-white cultivar exhibited the largest reduction in plant height of 51.1% compared to 40.5% for the Tokunoshima-yellow cultivar at 12 DAT compared to WW conditions (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Effects of various waterlogging durations on plant height (A), number of branches (B), and number of leaves (C) at early growth stage of cassava cultivars. Uppercase letters above bars indicate significant differences between waterlogging durations, while lower case indicate differences among the waterlogging treatments. Bars are mean ± SD.

The number of branches per plant was not significantly affected by WL treatment at all treatment durations or by the interaction between treatment duration and waterlogging treatment (Table 1, Figure 5B). The cultivars did not display any difference between treatments (Table 1, Figure 5B). However, the treatment duration did not have a significant effect (p < 0.05) compared with WW cultivars (Table 1, Figure 5B). The number of branches per plant of WL Tokunoshima-white and Tokunoshima-yellow cultivars decreased by 14.3% and 25% at 4 DAT, respectively, compared to WW cultivars. Tokunoshima-yellow cultivar exhibited the largest reduction in the number of branches by 25% at 4 DAT compared with Tokunoshima-white cultivar with 14.3% compared with WW-treated cultivars (Figure 5B).

Finally, the number of leaves per plant of both cultivars was significantly (p < 0.001) affected by WL treatment at 8 and 12 DAT but was not significant at 4 DAT. However, the effect of treatment duration on the number of leaves per plant was not statistically significant (Table 1). The effect of the interaction of treatment duration and condition had a significant effect (p < 0.01), and cultivars were significantly different (p < 0.05) (Table 1). The number of leaves per plant of WL Tokunoshima-white and Tokunoshima-yellow cultivars decreased by 26.4% and 6%, respectively, compared to those of WW cultivars. The Tokunoshima-white cultivar exhibited the largest reduction in the number of leaves per plant with 56.3% at 12 DAT compared with 50% for the Tokunoshima-yellow cultivar (Figure 5C).

The WL treatment had a nonsignificant effect on the number of branches and leaves at 4 DAT for the two cassava cultivars at the early growth stage; however, it had a significant effect on plant height at 4, 8, and 12 DAT. The damage of WL treatment and treatment duration on plant height and number of leaves increased with the treatment duration (Figure 5A–C).

3.6. Relationships Between Morphological Parameters, Leaf Gas Exchange, and Photosynthetic Parameters

Figure 6 presents the results of Pearson’s correlation matrix analysis of morphological parameters, leaf gas exchange, and photosynthetic parameters of the two cassava cultivars under WW (Figure 6b) and WL (Figure 6a) conditions. The results of the WL treatment revealed highly significant positive correlations between Pn and gs (p < 0.001, r = 0.94), E (p < 0.001, r = 0.98), PWUE (p < 0.001, r = 0.72). However, Pn was highly significantly correlated with leaf temperature (p < 0.001, r = −0.93), ΔT (p < 0.001, r = −0.91) but only significantly correlated with Ci (p < 0.05, r = −0.46). Net photosynthesis also showed non significance correlation with SPAD (r = 0.05) and Fv/Fm (r = 0.38) (Figure 6a).

Figure 6.

Pearson’s correlation matrix of the changes in morphological parameters, leaf gas exchange, and photosynthetic-related parameters of the two cassava cultivars under well-watered (b) and waterlogging (a) treatments. The number of biological replicates used was 3 plants/treatment.

In contrast, under WW treatment, the results revealed significant moderate positive correlation between Pn and gs (p < 0.001, r = 0.77), E (p < 0.001, r = 0.87), but significant weak negative correlated with PWUE (p < 0.05, r = −0.41). In addition, Pn showed significant weak negative correlation with leaf temperature (p < 0.01, r = −0.56) and ΔT (p < 0.01, r = −0.57), but higher significant weak positive correlation with Ci (p < 0.01, r = 0.54). However, Pn was not significantly correlated with SPAD (r = 0.07) and Fv/Fm (r = 0.04) (Figure 6b).

In addition, stomatal conductance was highly significantly negatively correlated with leaf temperature (p < 0.001, r = −0.82) and ΔT (p < 0.001, r = −0.87) as well as transpiration rate with leaf temperature (p < 0.001, r = −0.90 and ΔT (p < 0.001, r = −0.91) under waterlogging treatment (Figure 6a). Contrary to well-watered treatment, stomatal conductance was significantly moderately negatively correlated with leaf temperature (p < 0.001, r = −0.70) and ΔT (p < 0.001, r = −0.76) as well as transpiration rate with leaf temperature (p < 0.001,r = −0.68), and ΔT (p < 0.001, r = −0.72) (Figure 6b).

4. Discussion

When root growth and function are impaired by waterlogging, shoot growth and function are also restricted. In this study, waterlogging effects on morphological parameters, including plant height, number of branches, and number of leaves, were evaluated. At 4 DAT, reductions in the number of branches and leaves were not statistically significant, whereas plant height was significantly affected. With longer waterlogging durations (8 and 12 DAT), significant reductions were observed in plant height and number of leaves (Figure 5A–C). The severity of damage to cassava cultivars during early growth increased with waterlogging duration, which is consistent with findings by [32], who reported that prolonged waterlogging intensified stress effects in maize. These results indicate that 12 days of waterlogging significantly reduced cassava plant height but had no effect on the number of branches. The number of leaves began to decline from 8 DAT onward. The reduction in plant height and leaf number after 12 days of waterlogging can be attributed to decreased cell proliferation and expansion, as well as delayed leaf unfolding, which were shown to be inhibited by water stress [33]. “Similarly, Ledent J. (2002) reported that prolonged drought reduced leaf number and size while enhancing the retention of already expanded leaves [34]”, and Suárez L. and V. Mederos (2011) noted that leaf production and longevity are varietal traits strongly influenced by environmental conditions [35]. In cassava, leaf loss is considered a strategy to conserve water [36,37]. Furthermore, Aina O.O. et al. (2007) demonstrated that plant height is sensitive to water deficit, with reductions of up to 47% under drought in greenhouse and field conditions [38]. These findings highlight the heightened sensitivity of cassava to excess water, reflected primarily in reductions in plant height and leaf number. Therefore, plant height and leaf number, rather than branch number, may serve as reliable parameters for evaluating waterlogging tolerance in cassava during the vegetative growth stage.

To evaluate the photosynthetic ability of cassava plants under waterlogging, chlorophyll content and Fv/Fm were measured. SPAD values, which indicate relative chlorophyll content, were used to assess chlorophyll degradation. Results revealed significant differences in SPAD values among treatment durations (p < 0.01), waterlogging treatment (p < 0.05), and cultivars (p < 0.001) (Table 1, Figure 4B). Changes in soil chemical properties under waterlogging may have influenced SPAD values, potentially explaining the observed responses. Notably, cassava can maintain higher PNUE under nitrogen-deficient conditions induced by waterlogging. This finding is consistent with [39], who reported that cassava can acclimate to nitrogen starvation, which is an adaptation linked to its evolution in environments with inherently low nitrogen availability.

Fv/Fm was used as a reliable indicator of photo-inhibitory impairment in plants under environmental stresses, including waterlogging. “According to Long S. et al. (1994), the Fv/Fm ratio is a key parameter for detecting damage to photosystem II (PSII) and identifying the occurrence of photoinhibition [40]”. In this study, Fv/Fm values exhibited no significant differences between treatments, except at 12 DAT (Figure 4A). The decline in Fv/Fm value at 12 DAT may reflect the sensitivity of the photosynthetic apparatus to waterlogging. Low oxygen concentrations are known to trigger hypoxia-related metabolism, including the induction involved in anaerobic fermentation, sugar utilization, and antioxidant defense [41,42]. The stability of PSII at 0, 4, and 8 DAT suggests that oxidative stress was limited during early waterlogging, which may be attributed to effective ROS scavenging and the absence of chlorophyll degradation, as supported by SPAD data (Figure 4B). Nishizawa A.Y. et al. (2008) reported that ROS scavengers reduce oxidative damage under abiotic stress [43] “while Cao et al. (2022) found that 6 days of waterlogging significantly increased the activities of superoxide dismutase, catalase, and peroxidase in cassava leaves and roots [44]”. Collectively, these findings suggest that cassava may possess mechanisms that allow metabolism adjustment and PSII protection under short-term anaerobic conditions. However, further studies are needed to elucidate the specific mechanisms underlying this tolerance.

Under waterlogging, root hypoxia reduces water uptake, and stomatal closure limits transpiration, which often results in increased leaf temperature due to reduced evaporative cooling [13]. In this study, leaf temperature and ΔT in two cassava cultivars increased under waterlogging at 4, 8, and 12 DAT compared to well-watered plants (Figure 2A,B). In addition, stomatal conductance was significantly negatively correlated with leaf temperature (p < 0.001, r = −0.82) and ΔT (p < 0.001, r = −0.87) as well as transpiration rate with leaf temperature (p < 0.001, r = −0.90 and ΔT (p < 0.001, r = −0.91) under waterlogging treatment (Figure 6a). Increased leaf temperature and ΔT under waterlogging caused physiological stress due to impaired transpiration and stomatal regulation (Figure 3B,C). This result was consistent with Pan, Jiang et al. (2019) who reported that, “leaf temperature was higher in the sensitive genotypes than that in the tolerant genotypes after waterlogging [45]”. The increased leaf temperature (Figure 2A) and decreased stomatal conductance and transpiration rate (Figure 3B,C) under waterlogging suggest that waterlogged plants regulate stomatal aperture to conserve relative water content under stress. A similar finding was reported by Utsumi Y. et al. (2019), “who suggested that the stomatal conductance and transpiration rate in leaves of acetic acid-treated plants decreased due to higher leaf temperatures compared to control plants to maintain relative water content and avoid drought [46] “ Surendar, K.K et al. (2013) “found increases of 2–3 °C in leaf temperature under water deficit relative to control conditions [47]”. Our results are further supported by Siddique, M. et al. (2000), “who demonstrated that water stress substantially decreased leaf water potential, relative water content, and transpiration rate, with a concomitant increase in leaf temperature [48]”. According to Nelson and Bugbee, (2002), “ΔT can reduce the influence of air temperature changes on leaf temperatures based on the monitoring of leaf water status [49].”

We also observed that the leaf gas exchange parameters of cassava were affected by waterlogging. A significant decrease in Pn, E, and gs was observed at 4 DAT (Figure 3A–C), indicating that the channel for water and CO2 exchange was restricted. According to Ahmed, S. et al. (2002), “the earliest response of plant species to waterlogging is stomatal closure, which limits gas exchange and decreases Pn and E in many plant species [50]”, including tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) [51], cassava [17], sorghum [52], and wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) [53]. This data suggests that the reduced gs is responsible for the decreased Pn and E in the evaluated cassava cultivars during early growth under waterlogging. Bansal and Srivastava (2015), reported that 6 days of waterlogging reduced the chlorophyll content of leaves in pigeon pea [54]. A similar observation was reported in sorghum after 12 days of waterlogging [52]. During photosynthesis, chlorophyll serves as a crucial pigment to absorb light energy [55], demonstrating that SPAD values are highly correlated with the leaf chlorophyll content. At 4 DAT, a significant decrease in SPAD values was observed in cassava cultivars under waterlogging (Figure 4B). However, no significant correlation was found between Pn and SPAD values (Figure 6a,b). Thus, reduced photosynthesis during the early growth of waterlogged cassava cultivars could be attributed to increased leaf temperatures and decreased gs and E. In this study, the effect of waterlogging on gs and E increased with increased treatment duration, resulting in the same trend as Pn (Figure 3A–C). The leaf temperature of WL cassava cultivars was significantly higher than that of WW cultivars at 4, 8, and 12 DAT (Figure 2A). These findings aligned with similar leaf temperature-based study on differential response of growth and photosynthesis in diverse cotton genotypes under hypoxia stress by [45], “who reported that, leaf temperature was higher in the sensitive genotypes than that in the tolerant genotypes after waterlogging”, which means that the tolerant plants could maintain a stable metabolic environment to avoid anoxia stress damage in the roots.

Furthermore, Pearson’s correlation matrix analysis revealed that leaf temperatures and ΔT were negatively correlated with Pn (r = −0.93, p < 0.001; r = −0.91, p < 0.001), gs (r = −0.82, p < 0.001; r = −0.87, p < 0.001), and E (r = −0.90, p < 0.001; r = −0.91, p < 0.001, respectively, under waterlogging treatment compared to Pn (r = −0.56, p < 0.01; r = −0.57, p < 0.01), gs (r = −0.70, p < 0.001; r = −0.76, p < 0.001), and E (r = −0.68, p < 0.001; r = −0.72, p < 0.001, respectively, under well-watered treatment (Figure 6a,b). This result indicates that increased leaf temperatures and ΔT caused by hypoxia conditions in the plant rhizosphere might have created unfavorable conditions for plants under waterlogged treatment compared to well-watered treatment, which resulted in strong a correlation with the WL treatment, because the abnormal leaf temperature and ΔT will disturb the physiological metabolism and subsequently lead to decreased leaf gas exchange parameters (Pn, gs, and E). These results align with Wang, W. et al. (2019), “who reported significant relationships among ΔT, RWC, and gas exchange parameters (E and Pn) [13]”. Additionally, the results aligned with Djanaguiraman, M. et al. (2011) and Luan et al. (2018), “who reported that increased leaf temperature caused by water deficit creates unfavorable conditions for plants; the abnormal leaf temperature will disturb the physiological metabolism, destroy the chloroplast structure, and decrease Pn [56,57]”. Surendar, K.K. et al. (2013) also “found a significant negative correlation between leaf temperature and photosynthetic rate [47]”. Based on our findings, we deduce that ΔT is closely related to leaf water content and gas exchange parameters, representing a real-time response supported by highly significant correlations. Therefore, ΔT was observed as a reliable index for assessing the leaf gas exchange and performance of cassava leaves under waterlogging. However, more studies with diverse cassava genotypes and environment are needed to confirm these findings.

Results on PWUE at 4 DAT under waterlogging (Figure 3E) indicate a strategy to maintain carbon gain while minimizing water loss. PWUE results at 4 DAT suggest that waterlogged cassava plants retained relative water content by regulating stomatal aperture to reduce water loss while sustaining some photosynthetic activity. This finding aligns with [58], who reported that under drought conditions, stomatal closure reduces transpiration (E) and increases PWUE, especially when photosynthesis remains more active than transpiration. This boost in PWUE (Figure 3E) often reflects a strategy to maintain carbon gain while minimizing water loss. Therefore, the statistically significant decrease in Pn, E, and gs of waterlogged cassava cultivars at 4 DAT and the negative correlation between Pn, gs, E, and PWUE and leaf temperature and ΔT (Figure 6a,b) indicate that as leaves become hotter than the air, these physiological functions are still actively responding, although in a stressed or compensatory manner. The strong negative correlation between Pn, E, gs, and PWUE under waterlogging suggests a survival or compensatory mechanism, maintaining carbon gain despite harsh hypoxia conditions. Increased ΔT often correlates with reduced leaf RWC, photosynthetic performance, and transpiration, especially in waterlogging-sensitive cultivars [13]. Thus, ΔT could serve as a useful real-time, nondestructive indicator of plant water and photosynthetic status.

5. Conclusions

Plant responses to waterlogging must be monitored in an accurate and timely manner to mitigate the adverse effects of waterlogging, especially on cassava production. The main objective of this study was to identify the relationship between cassava leaf temperatures and ΔT and leaf gas exchange parameters, as well as to understand the effects of waterlogging on leaf temperature. Key results indicated that waterlogging stress markedly reduced photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance, and transpiration rate in cassava, while increasing leaf temperature and ΔT led to impaired stomatal regulation and reduced evaporative cooling. Strong negative correlations between ΔT and photosynthetic parameters (Pn, E, gs, and PWUE) further suggested that ΔT can serve as a reliable, nondestructive indicator of cassava’s physiological responses under hypoxic conditions. Maintaining cooler canopies may therefore contribute to improved tolerance and survival under waterlogged conditions. ΔT shows promise as an indicator for rapid screening and selection of waterlogging-tolerant cassava genotypes. However, validation across a wider range of cassava cultivars and environments, and integration with additional parameters, such as leaf RWC, free water content, and anatomical traits, is recommended to strengthen its application in breeding programs. In conclusion, ΔT offers a simple and effective tool to guide agronomic practices, breeding, and crop improvement strategies for enhancing cassava resilience under waterlogging stress.

Author Contributions

L.A.: Conceptualization, methodology, data collection, data curation, formal analysis, writing, editing, proofreading, and experiment management. T.N.: Helped with data collection. A.T. and I.S.: Helped with data collection and proofreading. P.S. and R.C.: Proofreading and editing. J.-I.S.: Conceptualization, methodology, experiment administration, supervision, reviewing, editing, and proofreading. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the United Graduate School of Agricultural Sciences, Kagoshima University, Kagoshima City, Agricultural Studies Networks for Food Security (Agri-Net) scholarship program of the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available in Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30362716 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the United Graduate School of Agricultural Sciences, Kagoshima University, Kagoshima, Japan, for providing funding for this study and the Agricultural Studies Networks for Food Security (Agri-Net) scholarship program of the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) for providing a scholarship to the first author that allowed him to undertake this study, as well as Kizuna farm in Tokunoshima, Kagoshima prefecture, Japan, for provision of the experimental materials (Tokunoshima-white and Tokunoshima-yellow cassava cultivars).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Stromquist, N.P. World Development Report 2019: The Changing Nature of Work: By the World Bank; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; 151p, ISBN 978-1-4648-1342-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.L.T.; Gheewala, S.H.; Garivait, S. Full Chain Energy Analysis of Fuel Ethanol from Cassava in Thailand. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 4135–4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carsky, R.; Walker, P.; Hauser, S.; Dashiell, K.; Dixon, A. Response of Selected Crop Associations to Groundwater Table Depth in an Inland Valley. Field Crop. Res. 1993, 34, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriesse, W.; Fresco, L.O.; Dujvenbooden, N.V.; Windeijer, A.P.N. Multiscale Characterization of Inland Valley Agro-Ecosystems in West Africa. Neth. J. Agric. Sci. 1994, 42, 159–179. [Google Scholar]

- Ekanayake, I.J.; Dixon, A.G.O.; Asiedu, R.; Izac, A.-M.N. Improved-Cassava-for-Inland-Valley-Agro-Ecosystems. In Proceedings of the 5th Symposium of the International Society for Tropical Root Crops-African Branch (ISTR-AB), Kampala, Uganda, 22–28 November 1992. [Google Scholar]

- More, S.J.; Ravi, V.; Raju, S. The Quest for high Yielding Drought Tolerant Cassava Variety. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2020, SP6, 433–439. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, P.; Pörtner, H.; Roberts, D.; Skea, J.; Shukla, P.; Pirani, A. Global Warming of 1.5 C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5 C above pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty. In Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Ponnamperuma, F.N. Effects of Flooding on Soils. In Flooding and Plant Growth; Kozlowski, T.T., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1984; pp. 9–45. [Google Scholar]

- Koslowski, T.T.; Pallardy, S.G. Effects of Flooding on Water, Carbohydrate and Mineral Relations. In Flooding and Plant Growth; Koslowski, T.T., Ed.; Academic Press Inc.: Orlando, FL, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Voesenek, L.A.C.J.; Blom, C.W.P.M. Blom, Growth Responses of Rumex Species in Relation to Submergence and Ethylene. Plant Cell Environ. 1989, 12, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setter, T.L.; Waters, I.; Sharma, S.K.; Singh, K.N.; Kulshreshtha, N.; Yaduvanshi, N.P.S.; Ram, P.C.; Singh, B.N.; Rane, J.; McDonald, G.; et al. Review of Wheat Improvement for Waterlogging Tolerance in Australia and India: The Importance of Anaerobiosis and Element Toxicities Associated with Different Soils. Ann. Bot. 2009, 103, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, M.; Popescu, G.C. Diurnal Changes in Leaf Photosynthesis and Relative Water Content of Grapevine. Curr. Trends Nat. Sci. 2014, 3, 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Zhou, Y.; Yue, Z.; Chen, X.; Cao, X.; Ai, X.; Jiang, B.; Xing, Y. The Leaf-Air Temperature Difference Reflects the Variation in Water Status and Photosynthesis of Sorghum under Waterlogged Conditions. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Zhou, G. Relationship of Leaf Water Content with Photosynthesis and Soil Water Content in Summer Maize. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2018, 38, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorio, P.; Sorrentino, G.; D’andria, R. Stomatal Behaviour, Leaf Water Status and Photosynthetic Response in Field-Grown Olive Trees Under Water Deficit. Environ. Exp. Bot. 1999, 42, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egilla, J.N.; Davies, F.T., Jr.; Boutton, T.W. Drought Stress Influences Leaf Water Content, Photosynthesis, and Water-Use Efficiency of Hibiscus Rosa-Sinensis at Three Potassium Concentrations. Photosynthetica 2005, 43, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquilino, L.; Nayatami, K.L.; Tamu, A.; Soe, I.; Sakagami, J.I. Photosynthetic Function Analysis under Rhizosphere Anaerobic Conditions in Early-Stage Cassava. Photosynth. Res. 2025, 163, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, A.; Mayer, J.; Gozlan, G. Infrared Thermal Sensing of Plant Canopies as a Screening Technique for Dehydration Avoidance in Wheat. Field Crop. Res. 1982, 5, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmesh, R.B.; Kiran, B.O.; Somanagouda, B.P.; Ashwathama, V.H. Canopy Temperature in Sorghum under Drought Stress: Influence of Gas-Exchange Parameters. J. Cereal Res. 2022, 14, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopold, A.C.; Sun, W.Q.; Bernal-Lugo, I. The Glassy State in Seeds: Analysis and Function. Seed Sci. Res. 1994, 4, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shen, S.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Lin, S.; Xue, Y. Diurnal Variation in Leaf-air Temperature Difference and Leaf Temperature Difference and the Hybrid Difference in Maize under Different Drought Stress. J. China Agric. Univ. 2014, 19, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhıllon, R.; Rojo, F.; Roach, J.; Upadhyaya, S.; Delwıche, M.A. A Continuous Leaf Monitoring System for Precision Irrigation Management in Orchard Crops. Tarım Makinaları Bilim. Derg. 2014, 10, 267–272. [Google Scholar]

- Rajarajan, K.; Ganesamurthy, K.; Raveendran, M.; Jeyakumar, P.; Yuvaraja, A.; Sampath, P.; Prathima, P.T.; Senthilraja, C. Differential Responses of Sorghum Genotypes to Drought Stress Revealed by Physio-Chemical and Transcriptional Analysis. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 2453–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pineda, M.; Barón, M.; Pérez-Bueno, M.-L. Thermal Imaging for Plant Stress Detection and Phenotyping. Remote. Sens. 2020, 13, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, H.G. Use of Thermography for Quantitative Studies of Spatial and Temporal Variation of Stomatal Conductance over Leaf Surfaces. Plant Cell Environ. 1999, 22, 1043–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderegg, J.; Aasen, H.; Perich, G.; Roth, L.; Walter, A.; Hund, A. Temporal Trends in Canopy Temperature and Greenness are Potential Indicators of Late-Season Drought Avoidance and Functional Stay-Green in Wheat. Field Crop. Res. 2021, 274, 108311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, A.; Aher, L.; Hegde, V.; Jangid, K.K.; Rane, J. Cooler Canopy Leverages Sorghum Adaptation to Drought and Heat Stress. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balota, M.; Payne, W.A.; Evett, S.R.; Peters, T.R. Morphological and Physiological Traits Associated with Canopy Temperature Depression in Three Closely Related Wheat Lines. Crop. Sci. 2008, 48, 1897–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginkel, M.V.; Reynolds, M.P.; Trethowan, R.; Hernandez, E. (Eds.) Complementing the Breeder’s Eye with Canopy Temperature Measurements. In International Symposium on Wheat Yield Potential: Challenges to International Wheat Breeding; International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center: El Batán, Mexico, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yabuta, S.; Fukuta, T.; Tamaru, S.; Goto, K. The Productivity of Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) in Kagoshima, Japan, Which Belongs to the Temperate Zone. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, H.G. Use of infrared thermometry for estimation of stomatal conductance as apossible aid to irrigation scheduling. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1999, 95, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Gao, Y.; Qin, A.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, B.; Ning, D.; Ma, S.; Duan, A.; Liu, Z. Effects of waterlogging at different stages and durations on maize growth and grain yields. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 261, 107334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.A.C.; Setter, T.L. Response of cassava leaf area expansion to water deficit: Cell proliferation, cell expansion and delayed development. Ann. Bot. 2004, 94, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledent, J. Deficit Hidrico y Crecimiento de las Plantas: Respuestas al Deficit Hidrico: Comportamiento Morfofisiologico/Modelado Del Crecimiento De Las Plantas; Fundacion PROINPA: Cochabamba, Bolivia; Centro Internacional de la Papa (CIP): Lima, Peru; Proyecto Papa Andina: Lima, Peru, 2002; 79p, Available online: https://agris.fao.org/search/en/providers/122619/records/647248dd53aa8c896304ef1b (accessed on 15 November 2008).

- Suárez, L.; Mederos, V. Apuntes sobre el cultivo de la yuca (Manihot esculenta Crantz). Tendencias actuales. Cultiv. Trop. 2011, 32, 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- León, P.R.; Pérez Macias, M.; Gutiérrez Trocel, M.; Rodríguez Izquierdo, A.; Fuenmayor Campos, F.; Marín Rodriguez, C. Caracterización ecofisiológica de cuatro clones de yuca del banco de germoplasma del INIA-CENIAP. Agron. Trop. 2014, 64, 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Vandegeer, R.; Miller, R.E.; Bain, M.; Gleadow, R.M.; Cavagnaro, T.R. Drought Adversely Affects Tuber Development and Nutritional Quality of the Staple Crop Cassava (Manihot Esculenta Crantz). Funct. Plant Biol. 2012, 40, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aina, O.O.; Dixon, A.G.O.; Akinrinde, E.A. Effect of Soil Moisture Stress on Growth and Yield of Cassava in Nigeria. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2007, 10, 3085–3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, J.; Mosquim, P.; Pelacani, C.; Araújo, W.; DaMatta, F. Photosynthesis Impairment in Cassava Leaves in Response to Nitrogen Deficiency. Plant Soil 2003, 257, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, S.; Humphries, S.; Falkowski, P.G. Photoinhibition of photosynthesis innature. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1994, 45, 633–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blokhina, O.; Virolainen, E.; Fagerstedt, K.V. Antioxidants, Oxidative Damage and Oxygen Deprivation Stress: A Review. Ann. Bot. 2003, 91, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.W.; Huang, L.; Shen, M.; Webster, C.; Burlingame, A.L.; Roberts, J.K. Patterns of Protein Synthesis and Tolerance of Anoxia in Root Tips of Maize Seedlings Acclimated to a Low-Oxygen Environment, and Identification of Proteins by Mass Spectrometry. Plant Physiol. 2000, 122, 295–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishizawa, A.; Yabuta, Y.; Shigeoka, S. Galactinol and raffinose constitute a novel function to protect plants from oxidative damage. Plant Physiol. 2008, 147, 1251–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Cao, M.; Zheng, L.; Li, J.; Mao, Y. Transcriptomic Profiling Suggests Candidate Molecular Responses to Waterlogging in Cassava. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0261086. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, R.; Jiang, W.; Wang, Q.; Xu, L.; Shabala, S.; Zhang, W.Y. Differential Response of Growth and Photosynthesis in Diverse Cotton Genotypes under Hypoxia Stress. Photosynthetica 2019, 57, 772–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utsumi, Y.; Utsumi, C.; Tanaka, M.; Van Ha, C.; Takahashi, S.; Matsui, A.; Matsunaga, T.M.; Matsunaga, S.; Kanno, Y.; Seo, M.; et al. Acetic Acid Treatment Enhances Drought Avoidance in Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz). Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surendar, K.K.; Devi, D.D.; Ravi, I.; Jeyakumar, P.; Velayudham, K. Effect of Water Stress on Leaf Temperature, Transpiration Rate, Stomatal Diffusive Resistance and Yield of Banana. Plant Gene Trait. 2013, 4, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, M.R.B.; Hamid, A.; Islam, M.S. Drought stress effects on water relations of wheat. Bot. Bull. Acad. Sin. 2000, 41, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, J.; Bugbee, B. Analysis of Environmental Effects on Leaf Temperature under Sunlight, High Pressure Sodium and Light Emitting Diodes. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Nawata, E.; Hosokawa, M.; Domae, Y.; Sakuratani, T. Alterations in Photosynthesis and Some Antioxidant Enzymatic Activities of Mungbean Subjected to Waterlogging. Plant Sci. 2002, 163, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Else, M.A.; Tiekstra, A.E.; Croker, S.J.; Davies, W.J.; Jackson, M.B. Stomatal Closure in Flooded Tomato Plants lnvolves Abscisic Acid and a Chemically Unidentified Anti-Transpirant in Xylem Sap. Plant Physiol. 1996, 112, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Jiang, D.; Liu, F.; Dai, T.; Jing, Q.; Cao, W. Changes in Photosynthesis, Chloroplast Ultrastructure, and Antioxidant Metabolism in Leaves of Sorghum under Waterlogging Stress. Photosynthetica 2019, 57, 1076–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Jiang, D.; Liu, F.; Dai, T.; Jing, Q.; Cao, W. Effects of Salt and Waterlogging Stresses and their Combination on Leaf Photosynthesis, Chloroplast ATP Synthesis, and Antioxidant Capacity in Wheat. Plant Sci. 2009, 176, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, R.; Srivastava, J.P. Effect of Waterlogging on Photosynthetic and Biochemical Parameters in Pigeonpea. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2015, 62, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamitsu, Y. Effects of Nitrogen Supply on Growth Characteristics and Leaf Photosynthesis in Sugarcane. Sci Bull. Coll. Agr. Univ. Ryukyus 1999, 46, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Djanaguiraman, M.; Prasad, P.V.V.; Boyle, D.L.; Schapaugh, W.T. High-Temperature Stress and Soybean Leaves: Leaf Anatomy and Photosynthesis. Crop. Sci. 2011, 51, 2125–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, H.; Guo, B.; Pan, Y.; Lv, C.; Shen, H.; Xu, R. Morpho-Anatomical and Physiological Responses to Waterlogging Stress in Different Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) Genotypes. Plant Growth Regul. 2018, 85, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.M.D.; Endres, L.; Ferreira, V.M.; Silva, J.V.; Rolim, E.V.; Filho, H.C.W. Photosynthetic Capacity and Water Use Efficiency in Ricinus communis (L.) under Drought Stress in Semi-Humid and Semi-Arid Areas. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2017, 89, 3015–3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.