Abstract

COVID-19 significantly disrupted the progress of the SDGs globally, including in Saudi Arabia. This study explores the progression of SDGs in Saudi Arabia during and after COVID-19, focusing on four dimensions: financial, socioeconomic, health, and environmental. A qualitative approach was employed, involving 19 semi-structured interviews conducted in two rounds (during and post COVID-19). Thematic analysis, conducted using NVivo 14.0, identified four main themes and 16 subthemes, which align with the SDG dimensions. The study revealed significant disruptions across four SDG dimensions during the pandemic. These included economic downturns, increased poverty, strained healthcare systems, and environmental changes. Guided by systems theory as an analytical lens, the study findings indicate that while COVID-19 caused disruptions across SDGs, it also acted as a catalyst for transformational shifts across interconnected SDG domains. The post-pandemic period has shown recovery, including economic growth, enhanced gender equality, improved mental health services, and a renewed focus on sustainability. Six cross-thematic themes emerged: (1) economic recovery and employment, (2) gender equity and education, (3) mental health and healthcare, (4) poverty reduction and food security, (5) environmental sustainability, and (6) digital transformation resilience. Based on these insights, the study provides recommendations for Saudi policymakers to align SDG progress with Saudi Vision 2030 in line with pragmatic sustainability.

1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has generated an extraordinary health circumstance, which hampered the socioeconomic growth in many nations by impeding the process of attaining the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) initiated by the United Nations (UN) [1]. This paper examines the influence of COVID-19 on the progress of SDGs and their evolution and recovery trajectory in the post-COVID-19 period. Socioeconomic empowerment is the process of liberating citizens from cycles of poverty, assigning social roles, developing a sense of autonomy and self-confidence, and giving them the resources: employment, education, health services, etc. These are the main objectives of the United Nations’ SDGs. According to Shulla et al. [2], COVID-19 was a worldwide phenomenon that has dramatically altered the SDGs’ core focus and attracted our attention towards novel experiences and uncertainties that had not been anticipated. During the COVID-19 pandemic, lockdowns had a profound influence on mobility and migration, leading to substantial human and economic consequences. COVID-19 caused a mammoth economic crisis, with a lopsided influence on the developing economies [2]. Further, the COVID-19-induced global crisis hindered the progress of the SDGs in both developed and developing nations, necessitating the formulation of long-term resilience solutions [3].

The COVID-19 pandemic has increased economic and socioeconomic uncertainties [4,5]. As per the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the pandemic’s uncertainty was highest in advanced and emerging market countries, and, while rising, remained relatively modest in low-income nations [3]. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, numerous governments implemented various levels of lockdown and social distancing regulations to prevent the virus from spreading. These restrictions had a significant economic influence. The longer these restrictions remained in place, the more detrimental consequences they had on the economy, SDGs, and employment [6]. Nonetheless, the post-COVID-19 period has created new opportunities for accelerating the achievement of the SDGs, with nations such as Saudi Arabia initiating recovery plans and reforms for the affected sectors [7,8]. COVID-19 exposed systemic vulnerabilities in development progress, necessitating a broader evaluation of how national policies, institutional capacity, and resilience influenced SDGs outcomes over time. In the case of Saudi Arabia, the response mechanisms implemented during the pandemic—such as financial stimulus, social protection, healthcare investments, and environmental safeguards—played a critical role in mitigating the impact on development indicators. After the COVID-19 pandemic, the Saudi government introduced new digital and social policy initiatives, including the expansion of online education, increased investment in health security, and the advancement of sustainable economic diversification to revive momentum towards the SDGs [9,10,11,12]. This approach reflects a pragmatic sustainability orientation, where feasible national policy actions in response to crises (such as COVID-19) can support SDG progress in Saudi Arabia in line with Vision 2030.

Given the multidimensional nature of COVID-19’s disruptions, this study focuses on four critical dimensions that collectively represent the breadth of its developmental influence: financial, socioeconomic, health, and environmental effects. These dimensions align with the comprehensive framework of the SDGs, directing attention to areas of significant influence throughout both the crisis and recovery [13]. It examines both the COVID-19 period and the post-pandemic period to assess how SDGs trajectories shifted over time in response to these influences. To analyze and compare the impact during and after COVID-19, the study adopted a qualitative approach based on expert interviews conducted with policymakers, practitioners, and development professionals in Saudi Arabia.

Prior research on crisis management and disaster response suggests that a systems approach is needed to better understand and improve disaster response systems. The World Health Organization (WHO) and several international experts have advocated for the use of systems thinking approaches in designing plans to address complex social and health concerns [14], including the current fight against COVID-19. Accordingly, this research utilizes systems theory as the theoretical framework. This research focuses on the comparative effects of the COVID-19 period and the post-COVID-19 period on selected SDGs, examining how progress was disrupted and how recovery efforts have reshaped development trajectories. We considered the following SDGs for this purpose: SDG 1 (zero poverty), SDG 2 (no hunger), SDG 3 (decent health and welfare), SDG 4 (education of superior quality), SDG 5 (equality of gender), SDG 6 (access to safe drinking water and sanitation), SDG 8 (decent work and economic progress), SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure), SDG 10 (lessen inequalities), and SDG 13 (combat climate change). Our selection of these SDGs is based on Saudi Arabia’s goals, aligning with Vision 2030. Saudi Arabia, cognizant of the critical nature of continuous development, strives to address poverty, disparity, global climate change, harmony, justice, health, education, social security, and employment opportunities while also acknowledging the interrelated nature of these issues to ensure their inclusion in the country’s national strategy [15,16,17].

The choice to focus on Saudi Arabia is motivated by several reasons. To begin, Saudi Arabia has suffered due to COVID-19 like the rest of the world. Saudi Arabia reported 841,469 COVID-19 cases and 9646 deaths as of 13 April 2024 [18]. Saudi Arabia reported more than 5000 cases per day during the pandemic’s peak in June 2020 [19]. Saudi Arabia imposed restrictions on the Umrah pilgrimage on 27 February 2022, for the first time in eight decades of pilgrimages to holy sites [20]. The COVID-19 preventive public policy measures aimed at halting the virus’s spread had a detrimental effect on the Saudi economy [21]. The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in significant health and economic repercussions, while strategic initiatives and a focus on digital transformation and sustainability-oriented policy adjustments have characterized the subsequent recovery [22]. However, most studies assessing the ramifications of COVID-19 have focused predominantly on developed nations, with minimal emphasis given to the recovery dynamics in emerging and developing countries, such as Saudi Arabia [23,24,25]. Second, Saudi Arabia is the Gulf Cooperation Council’s (GCC) biggest and most populous country. Additionally, it has one of the largest stock markets in the GCC and the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region in relation to listed firms and market capitalization [26]. Saudi Arabia also made concerted efforts to implement policies and initiatives to mitigate the COVID-19 impact [27,28,29]. Post COVID-19, these initiatives evolved into a long-term national framework aligned with Saudi Vision 2030, featuring programs aimed at digitalizing the education system [30,31,32], social protection measures, developing green infrastructure, and improving digital government capabilities [33]. Given Saudi Arabia’s central role in the GCC as an economic entity, these disruptions during the COVID-19 era, along with their subsequent impacts throughout the recovery phase, affected the SDGs.

Accordingly, the study is guided by research questions:

RQ1: How has COVID-19 influenced SDGs in Saudi Arabia across financial, socioeconomic, health, and environmental dimensions?

RQ2: How has the trajectory of SDGs progress shifted in the post-COVID-19 period compared to the pandemic period under the influence of these four dimensions?

The current research contributes to the literature on COVID-19 and economic growth. It is among the few qualitative studies that adopt a comparative approach to evaluate the performance of SDGs in Saudi Arabia during the pandemic and in the post-pandemic recovery phase. This supplements current research on Saudi Arabia and other GCC countries in general, as they experience similar economic, social, and cultural characteristics. While earlier studies have primarily focused on short-term disruptions, this research provides an in-depth exploration, utilizing expert insights to understand the progression and recovery pathways of the SDGs. This study draws insights from qualitative interviews to understand national perspectives on SDG challenges and the adaptive responses that shaped the current trajectory. Thirdly, this study utilized systems theory to guide its analysis and presents findings that may have ramifications for Saudi Arabia’s regulators and policymakers. Systems theory is especially applicable in this context, as it emphasizes the interdependence of economic, health, and social subsystems during complex disruptions like pandemics [14]. Overall, the study aligns with the notion of pragmatic sustainability, emphasizing policy-driven and feasible solutions that sustain SDG progress in Saudi Arabia while managing crises (such as COVID-19).

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses the literature review and presents the context and Saudi Arabia’s SDGs in relation to COVID-19, examines the theoretical framework, and reviews pertinent research about the COVID-19 pandemic’s immediate and post-COVID-19 consequences on selected SDGs. Section 3 presents the methodology used in this study. Section 4 presents the research results. Section 5 discusses the research results, implications, limitations, and the scope for future research. Lastly, Section 6 summarizes and concludes.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Saudi Arabia’s SDGs and COVID-19

Saudi Arabia’s economy is still heavily reliant on the oil sector. Nonetheless, an acceleration of reforms that started in 2016 led to advances in economic diversification, specifically in terms of participation of women in the workforce, non-oil revenue mobilization, and growth led by services [15]. In 2020, the Saudi economy suffered a major recession due to the twin blows of COVID-19 and lower oil prices, resulting in significant fiscal and external deficits. To halt the COVID-19 spread, the Saudi government implemented public policy measures like lockdown, border closures, social distancing, travel restrictions, quarantine, etc. [21]. These measures moderately affected some Saudi economic sectors (e.g., agriculture, wholesale-retail trade, public administration, etc.), severely affected some sectors (e.g., automobiles, oil and natural gas, health, social work, etc.), and very severely affected some sectors (e.g., airlines, cultural, sporting, etc.) [34,35,36]. The country has a dual problem of dealing with the pandemic directly and with the indirect effects of the public policy measures [37]. These combined dynamics have a detrimental effect on the Kingdom’s SDGs, as money and other resources required to implement developmental projects have been significantly reduced. Indeed, because these issues are interconnected, the Kingdom’s efforts to realize SDGs (such as poverty eradication, hunger eradication, decent health, educational quality, a decent life, gender equality, affordable and clean energy, safe drinking water and sanitation, adequate employment and economic progress, industrial innovation, and infrastructure, decreasing inequities and supporting sustainable cities and society) have slowed [15].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Saudi Arabia has attempted to eradicate poverty (SDG 1: zero poverty), driven by a sense of moral and humanitarian obligation. As a result, measures have been established to safeguard Saudi families against the direct and indirect effects of numerous economic reforms that may impose further responsibilities on some parts of society [38]. However, some of these initiatives have been hampered due to the paucity of funds and competing demands, especially from the health sector, due to reduced demand for crude oil export and dwindling oil revenues [21]. After the COVID-19 pandemic, targeted social assistance measures have been gradually reinstated, although fiscal constraints continue to impact the scale of these programs [39].

Saudi Arabia aims to achieve food security internally and beyond its borders (SDG 2: no hunger). The country has also allocated a greater percentage of its GDP to its agricultural sector to aid economic development and diversify its agricultural base [38]. However, this attempt to achieve food security has been harmed due to the COVID-19 pandemic and policy initiatives to contain the virus’s spread, most notably lockdown measures that prevented the import of much-needed agricultural inputs [21]. In the post-COVID period, food import logistics and domestic production systems have seen a renewed focus on investment, yet vulnerability to global supply chain shocks remains a concern [40].

Saudi Arabia aims to improve its citizens’ and residents’ health and well-being by initiating several health-related activities on a local and global scale (SDG 3: decent health and welfare). These activities include funding for maternal and childcare programs, vaccines, infant mortality reduction, and life expectancy expansion [38]. However, the COVID-19 pandemic initially diverted financial and health resources away from these health requirements to combat the virus [15]. In the post-COVID-19 period, Saudi Arabia has reinvested in public health resilience by implementing telemedicine, improving pandemic preparedness, and integrating digital health platforms for primary care [41].

Saudi Arabia places a premium on education, allocating the greatest share of the Kingdom’s budget [42] to ensure high-quality education (SDG 4: educational quality). Several governmental measures implemented in the aftermath of COVID-19 have significantly hampered efforts to enhance the quality of education [43]. In reaction to the pandemic, numerous face-to-face school closures have occurred [44], which is a legitimate policy response for COVID-19 containment. However, due to the educational institutions’ closure strategy, COVID-19 may negatively affect academic quality. In the post-pandemic period, hybrid learning strategies and education technology investments have expanded; however, the outcomes remain mixed, particularly for marginalized groups [45].

Saudi Arabia is making efforts to increase the participation of women in the workforce and reduce gender disparity (SDG 5: gender equality). Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 aspires to increase women’s employment, particularly in the health and education sectors [46]. The Saudi government has launched support programs for working women (such as wusool and qurra) [38]. The Saudi government has launched a training program (named daroob) to develop the employability skills of women [38]. Saudi Arabia has also strengthened equality and justice (SDG 10: reduce inequalities). It has championed training programs to improve youth employability. Also, it is training the citizens to respond to common risks via programs like Hafiz and Saned [38]. Post-COVID-19 pandemic, there have been modest but uneven improvements in female labor force participation driven by reforms such as easing guardianship, lifting the driving ban, and labor-market incentives, indicating the need for continued policy support and workplace reforms [47].

Similarly, Saudi Arabia has made attempts to achieve other SDGs. Saudi Arabia, for example, has made enormous expenditures on desalination and sanitation before COVID-19 (SDG 6: access to safe drinking water and sanitation) [38]. Following the COVID-19 pandemic, investments in water-reuse technology, smart metering systems, and integrated water resources management have increased in Saudi Arabia [48]. Attracting international talent is one of the Kingdom’s primary aims in its Vision 2030, as part of a broader strategy to improve the economy and create the environment necessary for people to have excellent jobs in line with SDG 8 (decent job and economic growth) [38]. During COVID-19, the labor market was severely disrupted, which hampered SDG 8. Post-COVID-19, labor market reforms, including the streamlining of immigration procedures, national employment initiatives through Saudization, and hybrid work reforms designed to augment productivity and workforce inclusion, have bolstered employment resilience [49].

Finally, Saudi Arabia has made significant progress toward achieving the Vision 2030 goals, including multiple programs focused on sustaining and operating major infrastructure projects in collaboration with the private sector (SDG 9: Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure) [38]. Prior to COVID-19, Saudi Arabia made substantial investments in infrastructure projects, which were stalled during COVID-19. These efforts are being revitalized in the post-COVID-19 pandemic phase, although their pace varies by sector and level of private sector engagement [50]. Saudi Arabia has formulated a national environment strategy to protect the environment (SDG 13: combat climate change). Under the national environment strategy, the Saudi government requires industries to adopt practices to reduce pollution and harmful impact on the environment. Further, the Saudi government is making efforts to increase the green cover and reduce desertification [38]. The COVID-19 pandemic led to temporary improvements in air quality and reductions in pollutant levels in Saudi Arabia due to decreased industrial activity and reduced traffic. In the post-COVID-19 era, the public and institutions are increasingly prioritizing the preservation of environmental gains and the enhancement of climate resilience through strategic, long-term planning and policy cooperation [51,52].

Saudi Arabia’s job creation and economic growth initiatives, safe drinking water and sanitation, industry creativity, and infrastructure investments have been hampered significantly by COVID-19’s stringent public health policies (like lockdown measures and social isolation policies) implemented to contain the virus’s spread. Alajlan [53] claims that the suspension of Hajj and Umrah pilgrimages has a substantial negative effect on Saudi Arabia’s tourism sector. This has a detrimental effect on the religious tourist sector’s revenue and all other linked services. Due to decreased demand for fuel and other petrochemical products, a major oil price drop resulted in a significant fall in earnings from crude oil exports [54]. Studies demonstrate that the travel ban enacted in response to the pandemic stymied some firms’ expansion ambitions, impacting banks’ loan portfolio growth and reducing enterprises’ capacity to create additional employment possibilities in the Kingdom [21,43].

As the preceding discussion demonstrates, the COVID-19 outbreak has a serious effect on the economic interests of the Kingdom, which has negatively affected many sectors of the economy and progress towards the SDGs [15]. Thus, COVID-19 significantly disrupted progress toward achieving several SDGs during the pandemic, although recovery has emerged gradually in the attainment of the SDGs in the post-pandemic period in Saudi Arabia [55].

2.2. Theoretical Framework

This paper adopts systems theory to explore the links between COVID-19 and SDGs. Systems theory is a sociopolitical framework for explaining global economic growth, particularly in capitalist economies. It describes dynamic exchanges and interrelationships among various parts of a system. It also explains interactions between organizations and their environments [56]. A system is developed utilizing the architecture and sequence of relationships that evolve via interfaces between components. Systems theory advocates reducing state structures and policies when a country is not operating appropriately due to sociopolitical reasons [57], such as disruptions caused by COVID-19. The theory recognizes that individuals’ experiences are profoundly shaped by institutional, economic, environmental, and sociopolitical structures. These structures influence how people perceive and respond to sustainability issues. By centering participants’ voices, the study aims to capture the richness and diversity of localized understandings of the SDGs. Their narratives provide important insights into the meaning-making processes central to sustainable development practice and policy formation [58]. Elements such as national policies or community-level engagement play a crucial role in shaping how individuals interpret and act upon sustainability in the wake of global disruption.

COVID-19 affected citizens’ decisions and government interventions in pursuit of the SDGs during the pandemic period. The health crisis created by COVID-19 and the numerous public policy actions and initiatives inflicted psychological, social, and financial challenges all over the world. During the COVID-19 crisis, it became apparent that health issues are inextricably linked to all human development endeavors and are necessary for SDGs [59]. Governments have focused their efforts on digital governance, inclusive education, and healthcare reform to accelerate the SDGs’ progress in the post-COVID-19 era [60]. The global economy, which is linked (as a system), has undertaken structural adjustments during and after the COVID-19 pandemic but faced systemic irreversibility during extraordinary financial hardship and a predisposition for stagnation, resulting in a loss of growth and future uncertainty. Thus, measures implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic (such as lockdowns, business closures, and social distancing) influenced the economy and the attainment of SDGs. On the contrary, education, low corruption, low criminality, sound economic governance, high productivity, innovation, and sound public health contribute to SDGs [61]. Given their interconnections, competent governments are strategically connecting these elements in the post-COVID-19 era to realign national objectives with the SDG targets [11].

The SDGs aim to eradicate poverty, defend the ecology and environment, and ensure that everyone can live in tranquility and affluence [1]. The SDGs, among others, are crucial to the Saudi Vision’s 2030 public health, employment, trade, and economic growth goals. Human health is an intrinsic part of all human endeavors and is necessary for long-term growth [62]. Thus, economies have faced economic, social, and occasionally political challenges due to health impairments caused by COVID-19 [63]. Apart from endangering health systems, COVID-19 resulted in a shortage of employment opportunities, poverty, inequality, and desecration of humankind [64]. As a result, COVID-19 had detrimental financial, socioeconomic, and health effects that impeded the achievement of the SDG objectives. However, these disruptions caused brief halts to economic activity but led to short-lived environmental gains, such as reduced carbon emissions, during the post-pandemic recovery phase [65]. According to the disaster risk modeling framework, economic growth and SDGs are inextricably linked in developing nations which continue to face a shortage of essential healthcare facilities [66]. Apart from wreaking havoc on global health, the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted practically all SDGs as socioeconomic difficulties worsened in most developing nations due to the measures implemented to stop the virus’s spread [67]. It embodies the core ideas of systems theory, which emphasizes how disruptions in one area of a system, in this case, public health, can have repercussions in the social and economic spheres. It embodies the core ideas of systems theory, which emphasizes how disruptions in one area of a system, in this case, public health, can have repercussions in the social and economic spheres, thereby providing a conceptual lens to examine interlinkages across economic, socioeconomic, health, and environmental SDG domains during and after the COVID-19. These disruptions in the post-COVID-19 period have prompted governments to improve sectoral coordination to realign the country’s recovery with the SDGs [68], providing a basis for policy-based pragmatic sustainability responses that support SDG progress during and after crises (such as COVID-19).

2.3. Prior Research on COVID-19 and SDGs

The empirical evidence demonstrating the relationship between government actions or policies and economic and social activities, particularly during times of crisis (economic, health, political, etc.), is wide and spans geographical locations [69,70,71,72]. There has been a direct association between efforts to flatten the COVID-19 curve to limit the virus and sustain the capabilities of the healthcare system and economic growth [6,21]. COVID-19 has presented a danger to the attainment of the SDGs and weakened them [73]. Government policies and initiatives in response to the COVID-19 crisis inevitably led to a global economic downturn. While governments’ measures of lockdown, social isolation, and others to halt the virus spread were necessary, the short-term negative impact was unavoidable [24]. Strict containment measures had a significant direct economic effect on all parts of the economy, especially in the services sector.

The protective measures adopted by various governments and organizations affected both the supply and demand sides. Specifically, containment measures led to lockdowns, transportation restrictions, and the closure of public spaces. These measures resulted in facility closures, service reductions, and supply chain disruptions on the supply side. On the demand side, these protective measures led to reduced movement and mobility, purchasing power, and loss of consumer confidence. In the post-COVID-19 phase, many of these social and economic disruptions have normalized. With the help of the government fiscal stimulus and national recovery programs, nations have witnessed a gradual recovery in public sector expenditures, consumer spending, and supply chain efficiency. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed structural flaws, but it also accelerated policy coherence in the areas of sustainability, health, and the economy [21].

2.3.1. Financial Effects of COVID-19

Numerous experts have conducted historical analyses of the financial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Ludvigson et al. [74] demonstrated that pandemics such as COVID-19 generate significant, multi-period exogenous jolts. Economic activity had been halted due to lockdowns in developed and developing countries, resulting in a downturn in the economy. While COVID-19 triggered a significant contraction in the world’s GDP, the contraction was the largest in developing economies [75,76]. Komarov et al. [77], Das and Beg [78], Tran et al. [79], and Barro et al. [80] demonstrated that the COVID-19 pandemic had a considerable negative influence on the economy in the short term. As per Komarov et al. [77], social distancing measures led to reduced financial activity. To safeguard their health, individuals avoided the consumption and purchase of specific products and services, resulting in direct costs (such as medical and hospital expenses) and indirect costs (including production losses). This loss of economic activity had cascading consequences on sanitation (SDG 6) and infrastructure (SDG 9) investments [79,81].

COVID-19 disrupted supply chains, the demand for the workforce, and employment opportunities, causing prolonged layoffs and increased joblessness [82,83,84,85]. Xu et al. [86] discussed the COVID-19’s effect and associated policies on economic activity. First, households were not compensated, which led them to reduce their consumption and savings. This reduction in savings led to a decrease in investment, ultimately resulting in the depletion of the capital stock. Second, households reduced their desire for imported goods, which negatively impacted global income and, consequently, the country’s exports. Thirdly, supply/demand shocks destabilized international and domestic supply chains. Fourth, shocks and interruptions led to a decrease in output, resulting in a decrease in the utilization of production elements. Due to this, the workforce was impacted by reduced working hours or layoffs and lower wages [87,88]. Due to the system’s interconnected nature, a negative impact on one sub-sector had rippling repercussions on other sub-sectors. During the COVID-19 pandemic, various governments implemented measures to limit the spread of the virus, which curtailed productive financial activities [4,5]. However, such policies had economic and social consequences, such as loss of production or employment of labor [89]. Studies based on data from the United States (US) (Safegraph data) revealed that economic activity in the US fell considerably and rapidly before the implementation of lockdown measures [90]. Coibion et al. [91] used surveys to estimate the macroeconomic intentions of US households. Lockdowns (not COVID-19 infections) were the primary driver of decreased consumption and employment, an inferior inflationary outlook, increased uncertainty, and reduced loan payments.

In the post-COVID-19 era, fiscal stimulus, trade normalization, and the acceleration of digital economic innovations helped restore global GDP trends [92,93]. Stimulus programs helped facilitate the resumption of market activities and supply chains, which in turn boosted investor confidence and reduced inflationary pressures [94]. Governments moved resources toward long-term SDG planning, infrastructure projects restarted, and economies reopened [95]. Economic activities and employment improved, targeted fiscal measures restored investments in many sectors, and global output began to recover [96]. Many disruptions lessened as trade networks stabilized and digital-led industries led the labor market recovery [97]. Structural changes in business models and labor practices helped to stabilize business operations and gradually restore jobs, enabling a gradual transition back to meeting SDGs [98].

2.3.2. Socioeconomic Effects of COVID-19

The negative socioeconomic influence of COVID-19 and resulting physical isolation and lockdown policies have been examined on gender equality (SDG 5), job markets (SDG 8), racial equality (SDG 10), educational quality (SDG 4), poverty (SDG 1), and hunger (SDG 2) [99,100,101,102,103,104,105]. During COVID-19, companies adopted work-from-home practices to prevent economic disruption due to physical separation and lockdown strategies [99,100,106,107]. Adams-Prassl et al. [100] US-UK study discovered that employees who could not work from home faced a greater risk of losing their employment. Forsythe et al. [103] and Adams-Prassl et al. [101] reported work hours and job losses because of COVID-19. Dreger and Gros [108] reported that lockdown measures and social distancing policies contributed to the increase in the US unemployment rate. According to Forsythe et al. [103], COVID-19 unsettled the economy, exacerbated unemployment and underemployment, thereby putting SDG 8 at risk. Research has shown that COVID-19 had an unequal impact on men and women. Women were excessively and adversely affected by COVID-19 [101]. The education and healthcare sectors primarily employ women [109]. However, the shutdown of educational institutions and daycare centers due to COVID-19 increased the need for childcare [110]. This affected working women/single mothers, as they had to spend more time and resources on childcare than males [111], which negatively influenced SDG 5 (gender equality). Similarly, a worldwide recession due to COVID-19 hindered the accomplishment of SDG 10 (reduced inequalities), as it disproportionately affected the most susceptible cohorts (such as women, low-wage employees, the unorganized sector, small and medium businesses, etc.) [2].

There were widespread school closures across countries in response to COVID-19, which reduced educational quality (SDG 4) [104]. But despite these challenges, COVID-19 created new opportunities for education systems, particularly in integrating technology into learning (such as digital learning) [6,21]. As per Mukhtar et al. [112], digital learning encouraged student-centeredness during COVID-19 and empowered students to become self-directed learners. However, digital education proved ineffective for practical learning and clinical studies. Moreover, digital education was constrained by access and bandwidth issues and the diminished attention span of students during virtual classes [113]. SDG 4 (educational quality) is linked to SDG 1 (zero poverty) and SDG 2 (zero hunger); the goal to eliminate poverty and hunger by 2030 [105]. However, COVID-19 threatened these goals, as did some restrictive government policies (e.g., lockdowns), which impacted the importation of vital agricultural inputs and, in some cases, food items. According to the OECD, food insecurity worsened across Africa during COVID-19. Thus, COVID-19 deteriorated food supply (SDG 2) in many developing and least-developed countries [114].

In the post-COVID-19 period, governments and international organizations have implemented reforms to advance the SDGs. The job market and employment opportunities have been revitalized due to economic recovery strategies, including employment preservation programs, targeted support, and workforce re-skilling [115]. The digital learning infrastructure has been enhanced, especially in under-resourced environments, hence contributing to the attainment of SDG 4 [113]. Gender-sensitive measures, including conditional cash transfers, digital access for women, and inclusive job training, have been implemented to restore gender parity and advance SDG 5, SDG 8, and SDG 10 [116,117]. Research indicates that climate-resilient agriculture, supported by policy-driven investments in local food systems, has enhanced food accessibility in nutritionally vulnerable and poor regions, hence aiding the attainment of SDG 1 and SDG 2 [118]. Such actions indicate a systematic effort to transform COVID-19 pandemic-induced vulnerabilities into enduring advantages, enabling the attainment of the SDGs.

2.3.3. Health Effects of COVID-19

Numerous studies have documented the COVID-19 pandemic’s influence on human health and mortality [119,120,121,122]. Research indicated that COVID-19 wreaked havoc on people’s psychological health and welfare [123,124]. As per research conducted in the US, COVID-19 was the cause of a 67% drop in overall outpatient appointments per healthcare provider during the second week of 2020, compared to the same week in preceding years [125]. This had significant health consequences, particularly for persons who suffered from chronic conditions.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been correlated with a rise in depression and unease, especially social loneliness [126,127]. As per Liu et al. [128], physical isolation or lockdown strategies negatively affected psychological welfare because of a shortage of necessary supplies, prejudice or segregation by neighbors or other social groups, economic loss, dullness, and exasperation. According to a Canadian study conducted by Gaind et al. [129], employees who were absent from work for reasons other than COVID-19 and jobless individuals saw a deterioration in their mental health. In their UK study, Hossain [130] showed a significant deterioration in mental health, with much bigger effects on women. Various studies revealed that social isolation and lockdown policies negatively affected public mental health [131,132,133]. During the later stages of COVID-19, health experts discovered that some patients who recovered from COVID-19 suffered from post-acute COVID-19 symptoms that led to long-term complications. These complications included dyspnea, thorax oppression, alimentary intolerance, vision disorder, insomnia, skin lesions, mental distress, depression, lack of concentration, black fungus infection, green fungus infection, etc. [134,135,136]. These various COVID-19 issues negatively influenced SDG 3 (decent health and welfare).

In the post-COVID-19 era, although health systems continue to address extended COVID symptoms and mental health burdens [137], notable healthcare advancements have also been documented. Global vaccination campaigns, which involved people participating in booster programs, led to a significant reduction in hospitalization and mortality rates, allowing healthcare providers to refocus on preventive and routine care [138]. Studies indicate that mental discomfort has progressively diminished when governments gradually eased quarantine measures and resumed social activities [139]. Furthermore, investments in telemedicine and integrated mental healthcare have enhanced access to services [140]. Collectively, these factors contributed to the revitalization of health systems and the progression of SDG 3, suggesting a shift from crisis management to an emphasis on long-term resilience and equitable healthcare delivery.

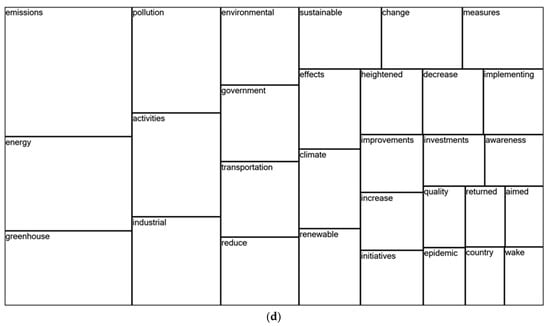

2.3.4. Environmental Effects of COVID-19

Finally, the worldwide standstill and significant slowdown in economic activity caused industries to operate at a minimum. This led to less pollution from industries and a reduction in carbon dioxide emissions [114]. So, the COVID-19-induced slowdown positively influenced the atmosphere [141] (SDG 13). Several studies, particularly in developed economies, backed up this claim. Brodeur et al. [122] and Brodeur et al. [121] examined the effect of work-from-home and safer-at-home practices on air pollution within the US. The study discovered that work-from-home and safer-at-home practices reduced air pollution. According to Cicala et al. [142], decreased vehicle travel and electricity use in the US because of the stay-at-home policy resulted in a decreased accident rate. Hu et al. [141] found that the lockdown policies of China, Korea, Japan, and India substantially improved the air quality index (AQI). Various researchers also corroborated this finding [143,144,145,146,147,148,149], who studied AQI and greenhouse gas emissions in China during COVID-19. So, COVID-19 has a favorable influence on the environment (SDG 13: combat climate change). These improvements, however, are only transitory, as the resumption of economic activities resulted in environmental degradation [114].

Following the COVID-19 pandemic, research suggests that the environmental benefits achieved during this period were, at most, temporary. Following the resumption of industrial operations and transportation across nearly all global regions, pollution levels returned to or exceeded pre-pandemic levels [150]. However, the COVID-19 pandemic catalyzed enduring changes in behavior and policies globally, including investments in renewable energy, remote work infrastructure, and climate-resilient urban development [151]. The proliferation of green recovery efforts across numerous nations aimed at clean energy transitions demonstrates the application of insights gained from the COVID-19 pandemic to reshape environmental policy in alignment with SDG 13. The environmental alterations induced by COVID-19 were transient; however, they have rekindled concern regarding sustainable environmental governance in the post-COVID-19 period.

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Design

The study employed qualitative analysis to achieve its research goals. This qualitative research explores the evolution of SDGs in Saudi Arabia. It is concerned with the impact on financial, socioeconomic, health, and environmental aspects during, as well as after, the COVID-19 outbreak. It explores the various implications of the COVID-19 pandemic on these aspects. It aims to understand both the short-term disruptions and the long-term implications. Thematic analysis was employed using the six-step process developed by Braun and Clarke [152]. This is the recommended technique for inductive, interpretive research, in which themes emerge from participant narratives and lived experiences [153,154]. The method facilitates in-depth engagement with qualitative data. It also enables researchers to identify patterns that capture the complexity of social phenomena. The use of NVivo 14.0 supported the systematic coding, categorization, and thematic mapping of textual data across interviews [155]. This enhanced the rigor and transparency of the analytical process. Moreover, it allowed for the development of rich, nuanced insights into the evolving landscape of the SDGs.

3.2. Sampling and Participants

A respondent pool of 19 was obtained using the convenience sampling method. This method was also planned to be reinforced with snowball referrals to reach out further, if required. Respondents were picked in consideration of their accessibility, applicability to the topic of research, and their willingness to provide useful insights [153,154,156]. Many individuals held professional roles in key sectors, including policy development, public health, environmental regulation, economic planning, and academic research. Their engagement in these areas helped them gain valuable insight into SDG-associated implementation as well as monitoring attempts in Saudi Arabia. To minimize biases and drawbacks associated with convenience sampling, conscious efforts were made to create diversity. These efforts involved variation along the lines of gender, socio-economic background, institutional rank, and regional coverage. The aim was to include perspectives from both central and peripheral regions, as well as from public and private institutions.

The study sample provided substantial conceptual diversity, which was essential for capturing a broad spectrum of perspectives on SDG progress within the Saudi context. The inclusion of participants from various institutional levels and sectors enabled a multi-dimensional understanding of sustainability efforts. Moreover, the sample size was sufficient to achieve thematic saturation. This is the stage in qualitative analysis when new themes or information cease to emerge in subsequent interviews. Achievement of saturation strengthens the study’s findings by enhancing the research’s depth of insight, as well as the credibility and reliability of the study’s results. This is true regardless of the inherent drawbacks of the non-random sampling design.

3.3. Recruitment Procedure and Selection Criteria

3.3.1. Recruitment Procedure

We recruited the participants for the interviews based on professional contacts and convenience sampling. We reached out to professionals working in government agencies, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), universities, and businesses. Only the participants who satisfied the inclusion criteria and were willing to participate were scheduled for interview sessions. We selected participants from industries such as healthcare, public services, education, digital services, airlines, banking, entertainment, and nonprofit organizations because these sectors were directly affected by COVID-19 disruptions and are closely linked to SDG implementation and Saudi Vision 2030 priorities. This sector-specific selection of participants was performed to obtain in-depth qualitative insights.

3.3.2. Inclusion Criteria

We employed the following inclusion criteria for the participants:

- Professional Role and Expertise

- (a)

- People who work or have worked for the government, NGOs, universities, or businesses that are working on programs connected to sustainability.

- (b)

- SDGs policymakers, researchers from government teams, or those working in national or local level projects/programs that support the Saudi Vision 2030.

- Relevance to Sustainable Development Goals

- (a)

- Respondents with expertise in one or more SDGs, especially those emphasized in Saudi Arabia, such as clean energy, sustainable cities, education, economic growth, climate action, and health.

- (b)

- Respondents working on projects related to COVID-19 to promote sustainable development.

- Experienced Executives During and Post COVID-19

- (a)

- The interviewees who were actively involved in SDGs-related work throughout the COVID-19 era and/or the recovery phase that followed

- Geographical Representation

- (a)

- Individuals from different parts of Saudi Arabia to get a range of opinions.

- Availability and willingness

- (a)

- Availability and willingness to participate, understand the study’s purpose, and be available for a scheduled interview session (in-person or virtual).

3.3.3. Exclusion Criteria

We employed the following exclusion criteria for the participants:

- (a)

- People who were not directly or indirectly involved in sustainable development projects or policy procedures.

- (b)

- Those who were not willing or able to give informed consent or who did not have enough experience linked to the research.

3.4. Data Collection

Interviews were conducted individually with each interviewee in two rounds from 1 October 2024 to 31 May 2025, in a semi-structured manner. In each interview round, 19 interviews were conducted. Round 1 (1 October to 15 December 2024) retrospectively examined the “during-COVID-19” period; Round 2 (15 March to 31 May 2025) investigated the post-COVID-19 phase. Each participant was interviewed once per round, resulting in 19 interviews in the first round and 19 interviews in the second round. Each personal interview lasted between 60 and 90 min per session. This two-round design allowed for probing of emergent themes and ensured the robustness of the process. It also provided opportunities to clarify or expand on previous responses. Interviews were either conducted face-to-face or via secure video conference technology. The format of the interviews depended on the participant’s preference, geographic location, and the simplicity of logistics. This flexibility increased the measure of accessibility without compromising the participant’s schedule or comfort. Both oral and written informed consent were obtained from all participants before the start of the interviews. This also facilitated ethical disclosure and compliance with the institutional review protocols. All the participants were well aware of the research goal. They were made aware of their right to withdraw at any time without any consequences. Participants were informed that their personal information would be held confidentially. All identifying material was deleted or anonymized at the transcription or data analysis stage.

Out of the 19 interviews per round, 16 were audio-recorded with the participants’ consent. This allowed for precise documentation of the discussions. However, 3 participants per round declined to participate in the audio recording due to personal or organizational reasons. Their responses were documented through detailed handwritten notes taken during the sessions. These notes were expanded immediately afterward to ensure completeness and accuracy. All audio recordings were transcribed shortly after the interviews. This timing helped preserve data integrity while the conversations remained fresh in memory. The transcripts were subsequently reviewed and validated with the participants. This step ensured accuracy and provided an opportunity to clarify any ambiguous or context-dependent responses [157]. This process of validation increased the credibility and trustworthiness of the data. Once the data analysis was completed, all the audio files were deleted in adherence to the ethical guidelines. Also, the identifying information was anonymized during transcription to maintain participant confidentiality and to uphold the ethical standards approved by the study’s review board.

The interviews were conducted in two distinct phases, covering the periods during and after COVID-19, which enabled a comparative assessment of progress toward the SDGs over time. It also enabled the capture of evolving stakeholder perspectives. The interview guide contained core questions related to the progression of SDGs during and after COVID-19 across four dimensions: (1) financial, (2) socioeconomic, (3) health, and (4) environmental. These domains were selected due to their central relevance to the progression of SDGs in Saudi Arabia. Although the question structure remained consistent across both rounds, follow-up questions were adapted thoughtfully. This ensured alignment with whether responses referred to the COVID-19 pandemic period or the post-COVID-19 recovery period. This structured yet flexible approach supported a nuanced exploration of temporal changes in SDG-related challenges and opportunities. It offered more profound insight into shifting priorities and evolving policy responses. Furthermore, it provided a strong foundation for answering research questions with contextual precision and analytical depth.

3.5. Method of Analysis

Reflexive thematic analysis was applied to the data using the six-step method proposed by Braun and Clarke [152]. Analysis was conducted as a team activity by the research team over a 60-day period. This involved several cycles of transcript review and multiple coding meetings to ensure consistency and rigor.

- Familiarization with the Data: Three authors independently read all transcripts to develop a deep understanding of the material. This stage involved initial note-taking, the identification of recurrent ideas, and familiarization with the tone, content, and contextual elements of the interviews.

- Generating Initial Codes: Manual, open coding was conducted line-by-line. Researchers assigned gerund-based or concept-driven codes such as “adapting regulations,” “facing funding constraints,” and “reinforcing social equity.” These initial codes were generated inductively from the raw data and were organized using NVivo 14.0 to ensure traceability and systematic coding.

- Searching for Themes: The team grouped related codes and identified preliminary themes. This process involved mapping conceptual linkages and clustering codes based on content overlap or shared meaning.

- Reviewing Themes: The team held multiple “compare and contrast” sessions to refine and validate the themes across all transcripts. This review occurred in two steps:

- o

- Step 1: Verifying the consistency between coded extracts and their assigned themes.

- o

- Step 2: Assessing whether the thematic structure accurately represented the overarching narrative of the full dataset. Misclassified or ambiguous codes were reassigned when necessary.

- Defining and Naming Themes: Themes were honed once identified, becoming distinctly defined and tagged to reveal their character of significance and research applicability [152]. The final product consisted of four core themes and sixteen subthemes, each synthesizing key characteristics of participant perspectives.

- Producing the Report: Finalized themes were supported by narrative synthesis and illustrative quotes chosen for their clarity, depth, and representativeness [158]. The findings were contextualized using existing literature to support triangulation and interpretation [58]. This integration allowed for the construction of a coherent analytical narrative, blending participant insights with theoretical perspectives [159].

The data from the two interview rounds were coded and analyzed both independently and comparatively. Thematic comparisons were made between the “during COVID-19” and “post-COVID-19” periods by tracking shifts in code frequency, content emphasis, and participant sentiment over time. This comparative approach enabled the identification of emerging, regressing, or evolving themes. It provided insights into the dynamic nature of SDG implementation trajectories in the Saudi context. The analysis captured how stakeholder perceptions and sectoral priorities shifted between the two phases of the pandemic.

The resulting themes were as follows:

- Theme 1: Financial Effects During and Post-COVID-19

- Theme 2: Socioeconomic Effects During and Post-COVID-19

- Theme 3: Health Effects During and Post-COVID-19

- Theme 4: Environmental Effects During and Post-COVID-19

3.6. Trustworthiness and Validity

To ensure methodological rigor, the study was informed by the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist [160]. Key concerns included reflexivity, transparency, and triangulation throughout the research undertaking.

- Triangulation: Coding and theme development were conducted collaboratively by multiple researchers. Each transcript was reviewed independently by at least two team members. Discrepancies in coding were discussed and resolved through consensus.

- External Validation: Three external experts—two researchers unaffiliated with the project and one SDGs practitioner—were invited to review the codes and emerging themes. Their feedback helped identify potential analytical blind spots and confirmed the coherence of the theme construction process.

- Member Checking: A preliminary summary of the analysis was shared with three participants (two men and one woman) for validation. All participants affirmed that the identified themes accurately reflected their experiences. No revisions were requested.

- Audit Trail: All coding procedures, team meeting notes, and analytical decisions were systematically documented. NVivo software logs served as a comprehensive and auditable record of code assignment and theme development.

- Reflexivity: Researchers maintained critical awareness of their positionality throughout the study. Regular meetings were held to examine interpretive assumptions. This was especially important when analyzing culturally nuanced narratives or discussing policy-sensitive issues.

4. Results

4.1. Participant Summary

Among the 19 participants in the study, slightly more than half were male (n = 13; 68.42%). All participants were employed in middle- or senior-level positions in public, private, and nonprofit organizations. They represented a broad array of sectors. These included healthcare (n = 7; 36.8%), public service (n = 4; 21.1%), digital services and education (n = 5; 26.3%), and entertainment, finance, or transportation (n = 3; 15.8%). Several participants were affiliated with government or semi-government institutions such as ministries, hospitals, or national centers. Other participants came from universities, airlines, or charitable organizations. Their functional roles varied and included managers, directors, professors, HR executives, IT specialists, and application developers. This distribution reflected a wide range of operational and strategic responsibilities. Participants’ work spanned diverse product and service areas. These included medical equipment, referral systems, environmental services, education, cybersecurity, and social development. Such professional diversity provided sector-specific insights into the progress of the SDGs during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. It also facilitated cross-cutting comparisons across environmental, economic, health, and social dimensions of sustainable development in Saudi Arabia (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Interviewee’s Personal Information.

4.2. Saturation Assessment

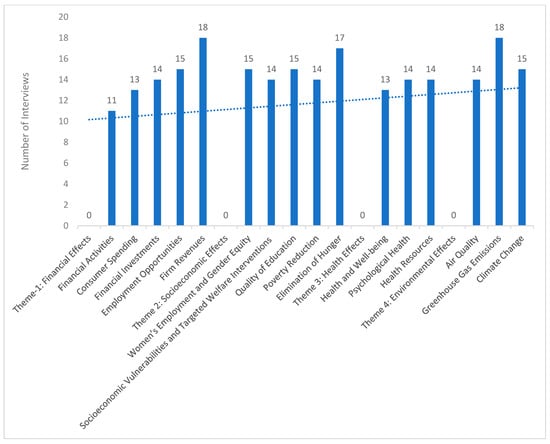

Saturation entails assessing the completeness of coding and thematic analysis, as well as a deep understanding of the data [161,162]. This method applies a stopping criterion to the frequency count method for coding in Table 2 and Figure 1. It involves reviewing an initial 11 interviews to identify new codes and using a predetermined stopping criterion, which is usually the number of consecutive interviews after the initial sample where no new codes are identified in the sample (in general, 2–3 interviewees). Saturation is reached when no new codes are identified. In this study, the stopping criterion was satisfied at 19 interviews, as the last 3 interviews generated no new codes. In prior research, the stopping criterion was based on code repetition, e.g., 3 or 5 instances of a particular code or themes/subthemes being identified [163,164,165,166].

Table 2.

Saturation Grid of Themes and Subthemes Represented in Interviews.

Figure 1.

Saturation Analysis of the Themes/Subthemes.

Figure 2 illustrates the saturation analysis of the individual interviewees’ references to themes or subthemes in the interview scripts for each interview. We stopped further interviews when we reached saturation of codes concerning particular themes/subthemes. As the stopping criteria was satisfied at the 19th interview, the planned use of snowball sampling was not required, since the last 3 interviews generated no new codes or themes, indicating both code and meaning saturation.

Figure 2.

Individual Interviewee References on Themes/Subthemes.

Table 3 provides a detailed description of the theme/subtheme development process based on the generated code. Table 3 also provides some illustrative codes related to the situation during and after COVID-19, as reported by the respondents.

Table 3.

Development of Themes/Subthemes, Code References from Themes/Subthemes.

4.3. Thematic Analysis

This section presents the study’s findings through four major themes. The analysis is guided by systems theory, where financial, socioeconomic, health, and environmental themes are considered interdependent system domains. Each theme is intentionally aligned with key SDGs and the strategic objectives of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030. These themes form the analytical framework used to explore the intersections between development dimensions and national priorities. Specific subthemes support each of the primary themes of the study. These subthemes were defined using scholarly literature and illustrated with direct quotes from participants. Such quotations introduce authentic voices and enrich the qualitative analysis. An interpretive analysis follows each theme. This analysis aims to uncover broader social, economic, and cultural implications that emerge from the data. The thematic structure also reflects how changes in one theme generate ripple effects across others, in line with systems theory. Where applicable, participant perspectives were quantified to identify patterns of agreement, divergence, and the distribution of views across the study sample. Incorporating this quantitative element strengthens the qualitative narrative. It adds depth and clarity to participants’ lived experiences and perceptions. Word clouds and tree maps are used as supportive visualization tools derived from coded interview data and are intended to support the interpretive, system theory-guided thematic analysis. As a result, the findings provide a more nuanced understanding of the SDG phenomenon in Saudi Arabia.

4.3.1. Financial Effects (SDG 8)

Financial effects involve both macroeconomic and microeconomic changes. These include shifts in income, spending, investment, employment, and business sustainability. Such changes are particularly evident following systemic shocks [167]. The visual data presented in Figure 3a,b (word clouds) and Figure 3c,d (tree maps) illustrate key textual patterns derived from the coded interview data concerning the financial impacts of COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia.

Figure 3.

(a) Financial Effects During COVID-19 (Word Cloud). (b) Financial Effects Post-COVID-19 (Word Cloud). (c) Financial Effects During COVID-19 (Tree Map). (d) Financial Effects After COVID-19 (Tree Map).

Financial Activities

A majority of participants (14 out of 19; 74%) reported a sharp contraction in financial activities during the pandemic. They attributed this decline to lockdowns, disrupted transportation systems, and falling oil prices. Respondent 17 remarked, “Almost all fields, such as travel, sales, business, and retail, were badly impacted.” Several participants expressed similar views, emphasizing the widespread disruption across diverse industries. In the post-pandemic period, government interventions were identified as essential to economic revitalization. These included investments in digital infrastructure, fiscal stimulus packages, and regulatory reforms. Participants perceived these actions as critical in reviving sectors such as tourism and aviation. Many linked the gradual recovery to the government’s rapid and targeted policy responses. These responses addressed immediate economic shocks while also aligning with longer-term development goals. Respondent 16 observed, “The financial sector has taken steps to increase its stability and attract investors.” Macroeconomic data support this perception. GDP rebounded from a −4.1% decline in 2020 to over 7.5% by 2022, reflecting a significant national-level recovery.

The findings suggest that strategic, state-led recovery efforts played a crucial role in mitigating economic damage. These efforts also repositioned the economy in alignment with Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 objectives.

Consumer Spending

Eighteen participants (95%) reported a reduction in household income and discretionary spending during the COVID-19 pandemic. This decline was attributed to financial uncertainty and disruptions in the employment sector. Respondent 14 commented, “The COVID-19 pandemic caused economic activity to stagnate, which hurt consumer spending.” As traditional shopping declined, e-commerce emerged as a substitute. Respondent 18 noted, “Social distancing was found to have the greatest influence on post-purchase shopping experience.” Several participants observed a rapid shift toward online platforms. This included both essential and non-essential purchases, highlighting a broader behavioral adaptation. In the post-pandemic period, participants reported an improvement in consumer confidence. This was especially notable in purchases of digital goods, health-related products, and luxury items. These trends reflect growing preferences for convenience, safety, and perceived value. Participants also suggested that necessity and increased digital literacy played a role in the development of these evolving habits.

The findings suggest that pandemic-related constraints drive adaptive consumption behaviors. They also highlight the role of digital transformation in promoting economic resilience and shaping long-term consumer behaviors.

Financial Investments

All 19 participants (100%) reported a decline in financial investments during the COVID-19 pandemic. This downturn was primarily attributed to uncertainty and widespread investor risk aversion. Several major Vision 2030 projects were paused or delayed. Resources were redirected to address immediate public health and emergency response needs. Respondent 17 noted, “The stock market returns dropped as COVID-19 cases increased.” This observation was consistent across responses. Participants described hesitation among investors and a noticeable contraction in capital flows. However, post-pandemic investment patterns were more optimistic. Participants observed increased capital allocations in sectors such as healthcare infrastructure, biotechnology, and renewable energy. Respondent 16 stated, “Saudi Arabia has significantly increased its investments in renewable energy projects.” Many participants linked this shift to strategic initiatives focused on economic diversification and resilience. The post-COVID period was widely regarded as an opportunity for sustainable growth and innovation.

These findings highlight a strategic realignment of capital priorities in response to the crisis. Sustainability now serves as a core pillar in long-term economic diversification and national development planning.

Employment Opportunities

Fifteen participants (79%) reported significant job losses in tourism, hospitality, and retail sectors. These industries were among the most severely impacted by lockdowns, travel restrictions, and reduced consumer demand. Respondent 19 estimated that “up to 1.2 million people could lose their jobs in 2020,” emphasizing the widespread disruption across both formal and informal labor markets. The rapid contraction in employment heightened concerns regarding income stability. This was especially true for low-wage earners and part-time workers, who were more vulnerable to displacement. Following the pandemic, job creation began to recover. Government-led wage subsidies, skills training programs, and increased demand in sectors such as healthcare and information technology played a key role. Respondents noted a growing trend for jobs that offer digital flexibility and essential services. These roles were perceived as more resilient in the face of future disruptions.

These findings illustrate the fragility of informal employment in crisis conditions. They also highlight the growing significance of digital and care-related sectors in shaping post-pandemic labor markets. The pandemic catalyzed the structural transformation of the labor market. It reinforced the need for workforce adaptability, social protection policies, and sustained investment in future-oriented industries.

Firm Revenues

Thirteen participants (68%) reported a sharp decline in firm revenues during the pandemic. This was attributed to reduced consumer demand, disrupted supply chains, and operational restrictions. Respondent 17 noted, “Firms with online platforms fared better than traditional businesses,” highlighting a competitive advantage for those that had already integrated digital tools and e-commerce. Participants observed that brick-and-mortar businesses without digital infrastructure struggled to adapt. Many experienced prolonged closures or permanent shutdowns. Economic recovery was credited mainly to targeted government interventions. These included tax relief, low-interest loans, and the resumption of infrastructure projects that stimulated economic activity and restored business confidence. Participants also reported that public support was extended to small and medium enterprises (SMEs). This assistance helped many firms modernize their operations and improve digital readiness.

The findings underscore the importance of digital transformation and cross-sector collaboration in promoting financial resilience. Digital readiness enabled firms to withstand the crisis better and recover more quickly. Public–private partnerships played a key role in this process, positioning businesses for sustainable recovery and future stability amid systemic shocks.

4.3.2. Socioeconomic Effects (SDGs 1, 2, 4, 5, 10)

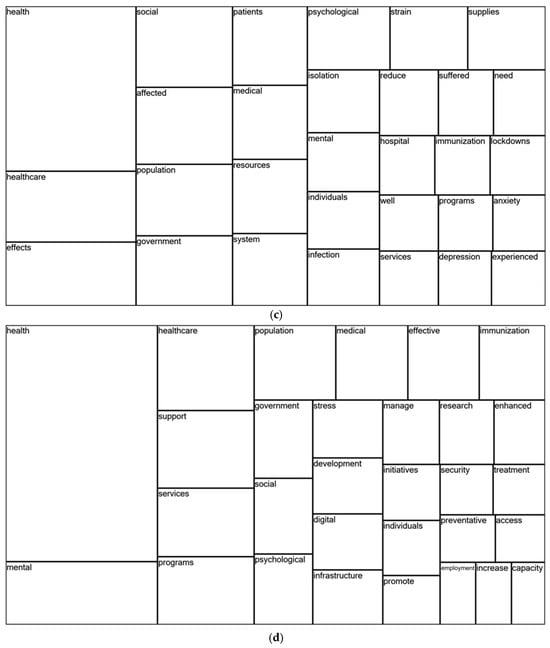

Socioeconomic effects refer to the interaction between social and economic inequalities. These effects are shaped by systemic disruptions impacting employment, education, gender equity, and food security [99,100,101]. Figure 4a,b (word clouds) and Figure 4c,d (tree maps) depict dominant themes derived from interview data regarding socioeconomic changes during and after the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia.

Figure 4.

(a) Socioeconomic Effects During COVID-19 (Word Cloud). (b) Socioeconomic Effects Post-COVID-19 (Word Cloud). (c) Socioeconomic Effects During COVID-19 (Tree Map). (d) Socioeconomic Effects Post-COVID-19 (Tree Map).

Women’s Employment and Gender Equity

Fourteen participants (70%) emphasized that women were disproportionately affected by the pandemic. This impact was most severe among those engaged in informal sectors, including home-based enterprises, freelance work, and small-scale retail. Respondent 18 stated, “Many Saudi women own small businesses working from home… but their access to resources is limited.” Participants identified barriers such as inadequate internet access, financial constraints, and limited formal business support. In the post-pandemic period, flexible work arrangements and e-learning platforms emerged as key enablers. These developments improved female employability across a range of sectors. Respondent 16 observed, “Online education and training programs have given women the opportunity to improve their employability.” Participants also noted a cultural shift. Remote work gained broader social acceptance for women, particularly in more conservative settings.

The findings indicate a convergence between gender inclusion and the expansion of digital infrastructure. These changes align with Vision 2030’s objectives for gender equity. Enhanced digital access not only expanded opportunities for women but also highlighted the need for inclusive digital policies to support long-term socioeconomic development.

Socioeconomic Vulnerabilities and Targeted Welfare Interventions

Seventeen participants (85%) identified low-income groups and migrant workers as the most severely affected during the pandemic. These populations experienced increased financial insecurity, job instability, and reduced access to healthcare. Participants attributed this vulnerability to their concentration in precarious, low-wage sectors. Respondent 18 explained, “Low-income families faced disproportionate challenges,” citing food insecurity, inability to pay rent, and lack of digital access for education or remote work. In response, the government implemented targeted social protection measures. These included the Citizen Account Program, which provided direct cash transfers to eligible households, and SMEs support grants aimed at preserving jobs and stimulating local economic activity. Additional measures involved food subsidies, deferred utility payments, and community-based assistance programs. These interventions aimed to cushion the socioeconomic impact on vulnerable populations and promote recovery.

The findings suggest a shift toward a more inclusive welfare model, focusing on resilience and the provision of basic needs. However, regional disparities in aid distribution and barriers to accessing support reveal enduring structural inequalities. Addressing these challenges requires more localized, data-informed policy strategies to ensure equitable long-term recovery.

Quality of Education

Thirteen participants (65%) reported that online education faced significant challenges during the pandemic. Access issues included a lack of digital devices, poor internet connectivity, and limited digital literacy. These barriers were especially severe in rural areas and among low-income families. Participants noted that students and educators alike struggled to adapt to digital platforms. Mental health also emerged as a significant obstacle to effective learning. Respondent 16 stated, “Mental health and wellbeing became serious issues,” referring to rising anxiety, social isolation, and decreased motivation among students. Over time, blended learning models—integrating in-person and online instruction—gained acceptance. Participants viewed this approach as more sustainable and inclusive for diverse student needs. Government investments supported this transition. Key initiatives included expanding digital infrastructure, providing teacher training, and increasing access to educational technologies. These reforms were seen as essential for long-term educational resilience.

While concerns about educational equity persist, the pandemic accelerated innovation in digital pedagogy. The crisis initiated structural shifts that may transform access, instructional delivery, and the quality of the learning experience for future generations.

Poverty Reduction

Fifteen participants (75%) reported a significant increase in poverty during the pandemic. Migrant workers, day laborers, and individuals in informal employment were among the most severely affected. These groups often lacked job security, access to healthcare, and eligibility for government assistance. As a result, they remained highly vulnerable to pandemic-related economic shocks. Respondent 19 stated, “Low-income migrant workers are particularly vulnerable,” referencing wage theft, overcrowded living conditions, and the absence of legal protections. Participants emphasized that rising unemployment and living costs intensified economic hardship in already marginalized communities. These compounded effects further deepened poverty and social exclusion. In response, the government implemented several recovery strategies. These included targeted income support, food distribution programs, and labor reforms. Efforts also focused on improving workplace protections and formalizing informal employment relationships.

The COVID-19 crisis magnified pre-existing poverty and social inequality. However, it also accelerated the expansion of social protection frameworks. The pandemic prompted policymakers to reassess how vulnerable populations are supported, both during emergencies and under normal socioeconomic conditions.

Elimination of Hunger

Ten participants (50%) reported experiencing or witnessing food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic. This was largely driven by disrupted supply chains, import delays, and panic buying. Such disruptions placed significant strain on local food availability and affordability. Respondent 18 noted, “Urban and rural households were affected differently by food price surges.” Rural areas often faced product shortages, while urban centers saw inflated prices for basic staples. Vulnerable groups—including low-income families and migrant workers—were disproportionately affected. Many struggled to access affordable, nutritious food during the height of the crisis. In response, the Agricultural Development Fund introduced targeted financing to support local food producers. Additionally, the National Food Security Strategy emphasized self-sufficiency through diversified sourcing and sustainable agricultural investment.

The pandemic brought food systems resilience to the forefront of national policy. It underscored the interconnection between agriculture, health, and equity. The crisis also revealed the urgent need for localized, inclusive strategies that can ensure stable food access during global disruptions.

4.3.3. Health Effects (SDG 3)

Health effects refer to the physical, psychological, and systemic consequences of COVID-19. These impacts affect both population well-being and the functioning of healthcare delivery systems [121,122]. Figure 5a,b (word clouds) and Figure 5c,d (tree maps) visualize participant discourse related to healthcare during and after the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia.

Figure 5.

(a) Health Effects During COVID-19 (Word Cloud). (b) Health Effects Post-COVID-19 (Word Cloud). (c) Health Effects During COVID-19 (Tree Map). (d) Health Effects Post COVID-19 (Tree Map).

Health and Well-Being

Sixteen participants (80%) reported that the healthcare system was overwhelmed during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Hospitals faced acute shortages of beds, medical personnel, and essential supplies. These included ventilators and personal protective equipment. Respondent 17 stated, “The healthcare system was overwhelmed,” underscoring the burden on both public and private health facilities as case numbers surged. Participants also described delays in non-COVID medical treatments and significant gaps in mental health services. Burnout among frontline workers was widely reported as a critical concern. In the post-pandemic period, participants observed significant investments in health system transformation. These included infrastructure upgrades, expansion of digital health services, and enhanced training programs for medical professionals. Improved emergency preparedness protocols and intersectoral coordination were also highlighted as part of the broader health reform strategy.

The findings underscore the importance of resilient and integrated healthcare systems, particularly during times of crisis. Strengthening system capacity, adaptability, and coordination has become essential for national health preparedness and equitable service delivery.

Psychological Health

Eleven participants (55%) identified a rise in mental health issues as a significant concern during the pandemic. They attributed this increase to prolonged isolation, job losses, and uncertainty about the future. Disruptions to daily routines were also noted as contributing factors. Respondent 18 remarked, “Depression, anxiety, and stress became more common,” emphasizing the emotional toll across various population groups. Youth, single parents, and unemployed workers were cited as especially vulnerable. Participants also highlighted the role of stigma and limited mental health awareness as barriers to seeking professional support. In response, several digital and institutional interventions were introduced. Mobile apps provided access to counseling and stress management tools. School-based mental health programs were expanded to support younger populations. Telemedicine platforms also began offering integrated psychological support, improving accessibility across regions.

Mental health has emerged as a visible and urgent public health issue. The findings underscore the need for systemic integration of mental health services into primary healthcare. Sustainable strategies prioritize accessibility, early intervention, and efforts to reduce stigma to balance the psychological health of society.

Health Resources