Abstract

It is necessary to advance traditional village sustainability by exploring the cultural dynamics integrated into contemporary heritage conservation. Jiangnan is located in a typical culturally integrated region of China that encompasses diverse traditional village heritage with variable spatial forms, influenced by a plurality of unique vernacular morphologies. To address the paucity of samples from culturally integrated regions, the simplistic digital quantitative indices, and the problem of non-specific cultural qualitative analyses, this research established a cultural spatial morphology form clue (CSMFC) at three cultural dimensions: Chinese family clan culture; natural ecological culture; vernacular feng shui culture. We constructed an index system and village morphology database comprising five types of traditional villages in Jiangnan. This research proposed a situational research method (SRM) based on metamodern theory to oscillate between quantitative metrics and the qualitative cultural context of 500 villages. The results demonstrate that village spatial morphology exhibits stepwise digital differentiation aligned with cultural boundaries, dynamically revealing the evolving relationship between village culture and spatial morphology. The implementation of an SRM can accurately map cultural distinctions, enhancing the scientific rigor and efficiency of traditional village cultural research and sustainable heritage conservation.

1. Introduction

Chinese traditional village space represents a unique vernacular cultural heritage within the historical context of human inhabitation. It presents clear regional variations and localized cultural characteristics [1]. Traditional village culture supports sustainable conservation in the current environment, with village spatial morphology playing a central role. Against this backdrop of conservation practice, Chinese traditional villages are undergoing a significant transformation. The rapid development of rural areas has resulted in dull and inappropriate patterns of village spatial organization [2]. This phenomenon has led numerous villages to experience an imbalance between development and protection, resulting in the continuous decay of internal cultural and spiritual vitality. The village morphology research methodology for macro-model construction is evolving, and the spatial structure and ecological aspects of village morphology have attained a theoretical maturity in technological application [3]. However, relying on a digital analytical framework remains insufficient in addressing the core challenge of heritage conservation: How to sustain the continuity of village culture in the face of rapid change? In promoting sustainable development of local village cultures, it is imperative to conduct comprehensive research that transcends the division of humanities and digital perspectives. Our proposed methodology is influenced by metamodern theory, which transcends, at once, the professed certainty of modernism and the deconstructive tendencies of postmodernism, balancing between digitization and humanities, outcomes and processes, and anchoring and emergence [4]. With a broad vision, this methodology identifies the unique cultural heritage of traditional villages, revealing sustainable pathways for cultural heritage regeneration.

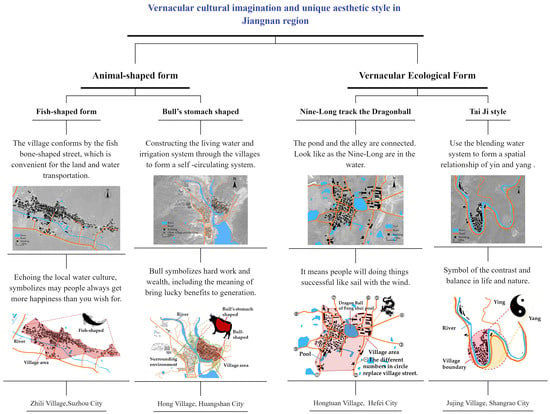

Jiangnan, located in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River, China, is a rapidly developing urban–rural area marked by geographic variability and cultural integration. Historically, population migration, north–south cultural integration, and the distinctive climate of villages have contributed to the spatial variety of traditional villages in the Jiangnan region [5]. It provides a typical case for investigating village morphology in a multicultural context, with all built before the Ming and Qing dynasties. Additionally, Jiangnan traditional villages present the spatial characteristics of a tangible environment, incorporating the wisdom of vernacular culture [6]. The local development of feng shui culture in traditional practical construction not only satisfied spatial layout principles but also effected a vernacular cultural imagination and distinctive spatial style (Figure 1). It is, we argue, essential to systematically explore the relationship between the spatial forms of culture and their digital quantitative characteristics, aiming to uncover the sustainable development potential of village space in cultural heritage preservation.

Figure 1.

Village samples demonstrating vernacular cultural imagination and unique spatial style in the Jiangnan region.

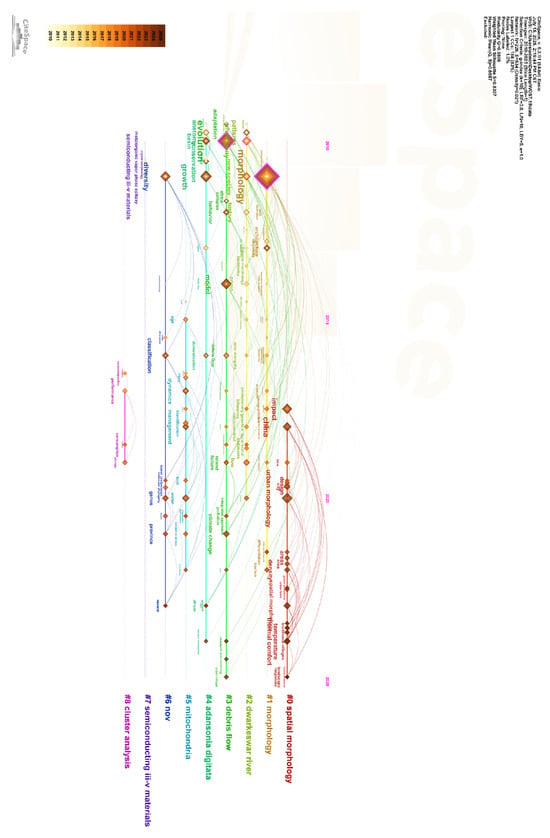

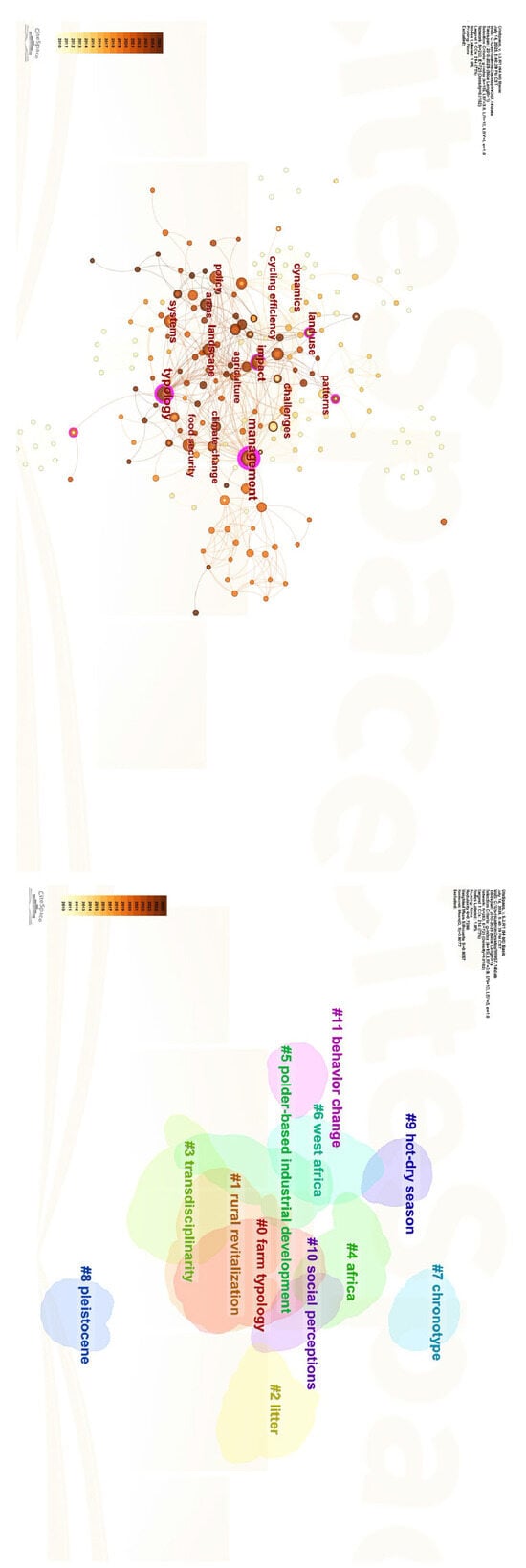

Currently, research on the spatial morphology of traditional villages has shifted towards systematic and digitalization approaches [7]. Scholars have conducted macro-analyses of building structures, historical folklore, cultural geography, and genetic maps from villages [8,9,10,11], processed from local resource integration to digital construction [12]. Bibliographic analysis reveals four distinct stages in the evolution of traditional village spatial morphology research (see Appendix A). Prior to 2000, research focused on descriptive studies of village forms based on field investigations, involving extensive surveys and data collection across various village types. From 2000 to 2012, theories concerning village spatial morphology from Eastern and Western perspectives converged, prompting scholars to focus on quantitative analyses of village spatial morphology prototypes. Since 2012, GIS and BIM technologies have been utilized to assist in identifying village spatial morphology, with exploration of its classification forms [13]. Analyses have been conducted from various perspectives, such as topography, climate, and functionality [14]. Since 2020, the field has entered a stage of diversified exploration, employing methods such as three-dimensional digitization, spatial quantitative analysis, and spatial gene maps to advance towards interdisciplinary integration [15]. Concurrently, contemporary village applications are being re-examined from multiple perspectives, including social structure, vernacular culture, and spatial habitat [16].

A keyword clustering map of words pertaining to village spatial morphology research over the past decade was obtained through CiteSpace6.3. R1 software analysis. The studies in question focus on spatial morphology, impact, conservation, and urban morphology, among other spatial material aspects (see Appendix B). Scholars such as Amos Rapoport [17], Marcel Vellinga [18], and Paul Oliver [19] have pointed out the relationship between residential space and culture, but these studies are still limited in exploring the relevance of the cultural dimension with the village’s spatial environment; hence, a number of the viewpoints expressed are purely theoretical. The scope of this research field has expanded from static spatial analysis to include dynamic holistic spatial studies. Research precision has improved across the integrated dimensions of the natural environment, family society, and vernacular culture [20].

However, the classification of village spatial morphologies presents challenges in the context of cultural research. Previous division standards were based on tangible forms, but culture is an intangible factor [21], which is restricted by elements such as the local environment, social worship, vernacular consciousness, etc. The methodology employed for culture-led village morphology analysis requires further exploration in sustainable heritage conservation. Generally, the research on traditional village forms is extensive, focusing on historical processes and social environments that shape village morphology [22]. These studies include few analyses of intangible morphological elements, the logical mathematical relationships between the different levels of traditional villages, and the interactions between spatial morphology and culture [23].

In this paper, we aim to address limitations in cultural research on village spatial morphology from a metamodern perspective, focusing on the cultural integration region of Jiangnan as a typical case. A cultural spatial morphology form clue (CSMFC) is constructed by analyzing the cultural context to determine the contemporary activation and utilization of villages. In this research, we propose a situational research method (SRM), combining traditional village spatial culture and digitalization to explore the dynamic relationships and characteristics of village forms. The main contributions of this study are as follows:

- (1)

- We expand the village samples across the Jiangnan cultural belt while integrating regional diversity and cultural contexts, proposing a CSMFC framework that classifies spatial morphologies for heritage conservation, enabling sustainable preservation.

- (2)

- Based on metamodern theory, we propose a situational research method (SRM) integrating digital quantification and cultural morphology to transcend the humanities–quantitative classification binary in heritage conservation.

- (3)

- Adopting a comparative perspective, we clarify key indices and attributes of local heritage and establish a Jiangnan cultural village heritage database to promote precise conservation methods.

2. Theoretical Framework

The village morphological quantitative analysis methods of Pu Xincheng have been increasingly applied recently [24]. Scholars have applied Pu’s methodology to advance spatial heritage in traditional villages across different regions. However, it remains insufficient for capturing the complicated morphology and cultural intricacy of the villages [25]. Cultural and other human factors demand high-quality data, spatial relationships, and vernacular information. Nevertheless, the existing research is limited to provincial-scale samples, and comparative studies led by cultural integration areas are lacking [26]. It is necessary to expand the sample size and further explore its scientific validity in areas characterized by typical cultural heritage [27]. As a manifestation of social culture, the question arises as to whether we further integrate digital quantification and cultural qualitative research to address the issue of cultural erosion in village sustainable development, which remains a challenge in current research [28].

The metamodern shift is a viable response to the key methodological and conceptual challenges in current heritage research. Metamodern theory has been used by scholars in the past to characterize artistic, cultural, and religious movements [29]. It offers a new dimension in our understanding of space, place, and geographical processes as dynamic, multi-layered realities. Simultaneously, it establishes a contemporary research framework for village heritage sustainability that is adaptive, contextual, and reflective, integrating rational insights with humanistic perspectives. The village possesses a multi-layered nature, comprising and influenced by its natural and human attributes. A defining characteristic of metamodern theory is oscillatory, i.e., sublationing binary choices between opposites and instead dynamically and consciously oscillating between them. The meaning and materiality of the village are inseparable. Storm points out that humans create and understand meaning through the material world, employing flexible, pragmatic, and diverse methodological combinations to address complex issues [4]. This offers a fresh perspective for current cultural studies of village spatial forms.

First, the anchoring dimension frames village spatial culture as a stable structure anchored by multiple elements, such as the organization of architecture, spatial layouts, and physical cultural symbols. Second, anchoring processes and the dynamic generation of village spaces need focus on the evolution of village forms amid cultural transformation [30]. A dual-dimensional analysis of spatial anchoring and cultural processes integrates historical stability with the dynamic cultural evolution of village forms [31]. Third, the theory emphasizes that subject–object and matter–spirit form a dynamic network of relationships. In this sense, village space integrates material carriers with cultural meaning, where cultural practices and spatial forms co-constitute with one another [32]. Based on this, our research situates village spatial forms within their cultural context, forming a situational research methodology (SRM) that speculates upon the mutual construction of spatial forms and culture. This approach thus requires a thorough consideration of the dynamic relationship between culture and spatial forms.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Area

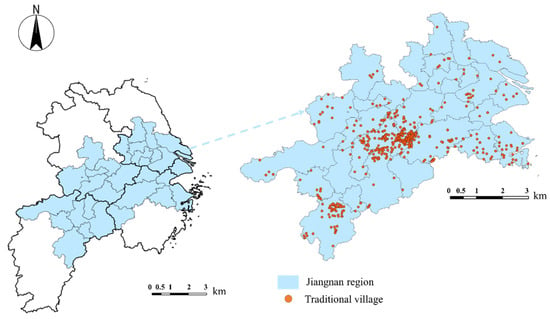

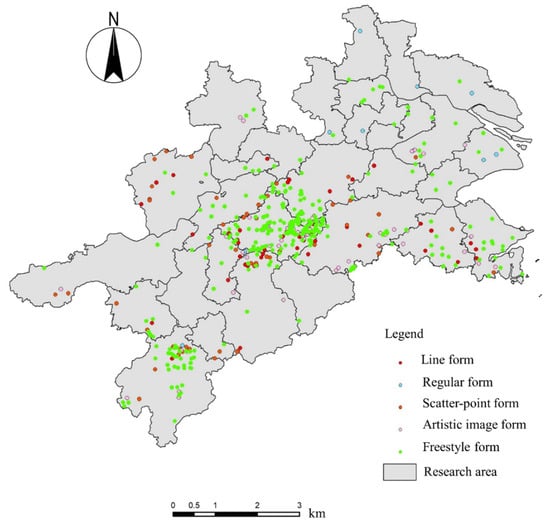

This study selected traditional villages in the cultural integration area of Jiangnan as its research object, including the area south of Jiangsu province, northeast of Jiang xi province, northeast of Zhejiang province, and south of Anhui province, Shanghai city. There are 500 samples in total (Figure 2). The research sample comprises nationally designated traditional villages in China, which were formed during the Ming and Qing dynasties. These villages preserve well-maintained architectural heritage and cultural characteristics such as clan traditions, folk customs, and artisanal skills. Their street and alley layouts, water system structures, and stable natural ecological patterns reflect Jiangnan cultural characteristics [33].

Figure 2.

The research area of the Jiangnan region.

3.2. Data Resources

Data resources from official websites [34,35] and statistical books [36,37,38], high-resolution satellite images, on-site investigations, unmanned aerial photographs (UAVs), village records, local cultural legends, etc. (Table 1). The on-site mapping of village spatial data is at a 1:1 scale (with an error margin of less than 0.5 cm).

Table 1.

The cultural elements and data resources of traditional village spaces.

Table 1.

The cultural elements and data resources of traditional village spaces.

| Cultural Elements | Spatial Data Type | Data Sources | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Text | Official website [29,30] and official statistical book [36,37,38] | |

| Village history and culture | Text | ||

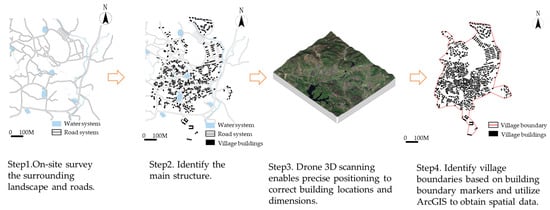

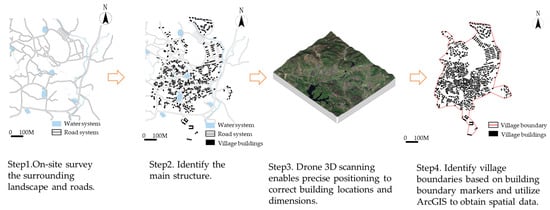

| Village image | Int | Google map and drone tilt photography for spatial acquisition of traditional villages by unmanned aerial photographs (UAVs) | The data acquisition process is shown in Figure 3. |

| Village spatial outline | Int | ArcGIS10.2 draw | |

| Natural geographical | Float | ArcGIS Terrain Geomorphology Map Overlay | |

| Village space units | Int | On-site research and ArcGIS10.2 draw | |

| Village size | Int | ArcGIS measurement | |

| Create feng shui culture | Text | Local records, on-site surveys and field interview information | |

| Other qualitative description | Text | ||

Figure 3.

The village data acquisition process.

3.3. Methods

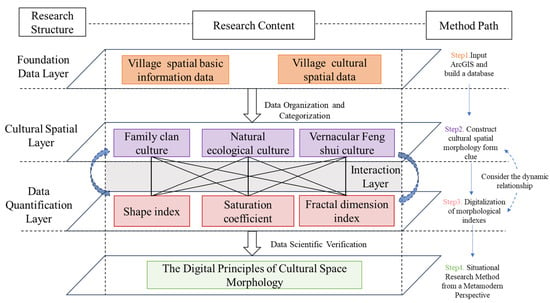

In this research, we establish a CSMFC and utilize the SRM to analyze the dynamic relationship between village cultural spatial morphology and digital quantification, which consists of four steps (Figure 4). First, we collect spatial information for 500 villages and build a database. Subsequently, we use ArcGIS10.2 to model 500 village spatial forms and construct a CSMFC based on morphology research. Third, we digitalize the morphological indices of village spatial forms. Finally, we summarize digital principles of cultural space morphology via SRM from a metamodern perspective. This process comprehensively considers the dynamic relationship between culture and spatial forms.

Figure 4.

The research process.

3.3.1. Cultural Spatial Morphology Form Clue (CSMFC)

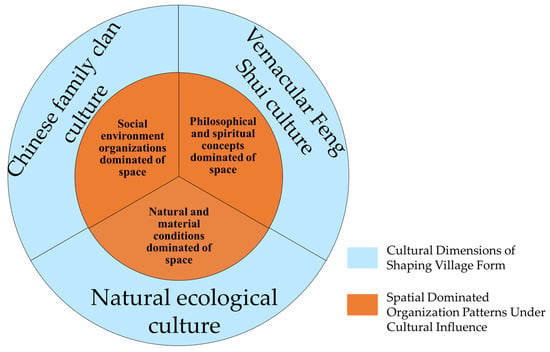

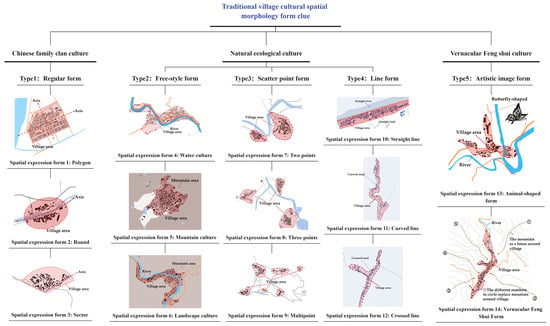

Architect and scholar Aldo Rossi developed a third typology by classifying architectural space types [39]. He argued that architecture and space should not be considered in isolation but should be comprehensively integrated into urban organization, historical civilization, and cultural context. Therefore, in this study, the essence of spatial morphology classification is not merely categorization but an exploration of the cultural logic underlying each form. For Chinese traditional villages, spatial morphology, with the Jiangnan region being a typical example, is shaped by collective spatial planning during agricultural civilization of villages [40]. The spatial morphology of traditional Chinese villages reflects certain cultural influences and is driven by three dimensions: Chinese family clan culture, natural ecological culture, and vernacular feng shui culture [41,42,43] (Figure 5). Under the influence of Chinese family clan culture, spatial organization is dominated by social environment organizations, forming regular layouts with hierarchical order through axial alignment. Under the influence of ecological culture, spatial organization is dominated by natural and material conditions, giving flexible and organic forms. Under the influence of feng shui culture, spatial organization is dominated by philosophical and spiritual concepts, integrating spiritual symbols and cultural motifs to generate pictographic spatial forms. Therefore, we established a cultural spatial morphology form clue (CSMFC) from three cultural dimensions, constructing an index system and database for five morphological types, and summarized the spatial expression form and morphological indices (see Figure 6, Table 2).

Figure 5.

Three dimensions of the traditional village spatial form.

Figure 6.

Traditional village cultural spatial morphology form clue image.

Table 2.

Traditional village cultural spatial morphology form clue.

3.3.2. Digitalization of Morphological Indices

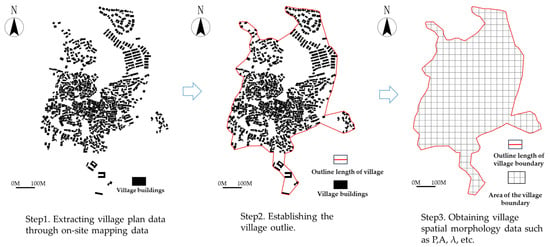

In this research, we extracted spatial information about the village using field surveying and drone aerial photography data. Using ArchiCAD, the village’s buildings, waterways, and roads were mapped at a 1:1 scale based on the original village plan data, resulting in a comprehensive spatial diagram of the village. Based on this, village spatial outlines were established using the corner vertices of the outermost buildings at the village edge as reference points rather than using line segment vertices to obtain an accurate and consistent village spatial morphology outline (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

The process of obtaining a village spatial morphology outline: a sample of the Xinye village.

According to the research on the quantification of village morphology by scholar Pu Xincheng, the quantitative indices for villages are the shape index S, saturation coefficient (ϴ), and the fractal dimension index (S2) [24]. Among these, the shape index (S) represents the complexity of the village’s morphology, the saturation coefficient (ϴ) represents the expansion trend of the village’s morphology, and the fractal dimension index (S2) represents the public spatial fragmentation level of the village.

- (1)

- Shape index: S

S represents morphological complexity. Its calculation formula is

In the formula,

P is the outline length of the village;

λ represents the length and width ratio coefficient;

A represents the area of the village.

S is proportional to the complexity of the village. The larger the numerical value of S, the greater the level of the village boundary, and the more complicated the boundary shape (Table 3).

Table 3.

The shape index of the morphology type.

- (2)

- Saturation coefficient: ϴ

ϴ represents the village external expansion trend. Its calculation formula is

In the formula,

A is the area of the village.

Sr is the area of the outer rectangle.

The ϴ does not exceed 1.

The ϴ has an inverse proportion relationship with the complexity of the village boundary. When the village boundary is more complex, ϴ is smaller, and the expansion trend is reduced. When the village boundary is simpler, ϴ is larger, and the expansion trend is greater [44].

- (3)

- Fractal dimension index: S2

S2 represents the village public spatial fragmentation level. Its calculation formula is

In the formula,

P is the outline length of the village.

A is the area of the village.

The changeable range of S2 is 1.0–2.0.

S2 is to reflect the level of fragmentation of the public space of the village by the relationship between the perimeter and area of the spatial patches. S2 increases with the level of fragmentation in the village public spatial structure, indicating improved spatial tissue efficiency.

3.3.3. The Situational Research Method (SRM)

The situational research method situated the spatial form of villages within their appropriate context, analyzing the relationships among spatial form patterns from a dynamic perspective [45]. In this study, the situational research method guided by metamodern theory anchors concrete cultural semiosis within the spatial framework of village culture. It aims to integrate quantitative spatial metrics with qualitative cultural analysis through comparative analysis, contextualizing numerical data within cultural clues to examine its dynamic relationships. To ensure the accuracy of the methodology, principal component analysis (PCA), K-means clustering, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were employed to validate the scientific rigor of each classification. Subsequently, ArcGIS spatial overlay analysis integrates the relevant cultural characteristics into a quantitative comparison (Figure 8). By overlaying 500 village morphological layers across shared geography, statistical methods are able to extract culturally driven spatial digital relationships.

Figure 8.

The part model example comparing situational research.

4. Results

4.1. The Comparative Data Validation of Research

To validate the accuracy and operational feasibility of the research framework, principal component analysis (PCA), K-means clustering, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were conducted using SPSS 27.0.1 software. Five spatial forms shaped by cultural influences, namely, regular form, freestyle form, scatter-point form, line form, and artistic image form, were uniformly coded. Quantitative influence factors, including outline length of the village (P), area of the village (A), shape index (S), fractal dimension index (S2), and saturation coefficient (ϴ), were standardized.

4.1.1. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

The study data (see Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6) were suitable for PCA (KMO = 0.625; Bartlett’s test, Sig. < 0.001). All variables showed strong loadings (communalities ≥ 0.80). Two principal components explained 88.726% of the total variance, capturing the village spatial characteristics and providing a sound statistical basis for cultural type clustering analysis, which effectively supports the structured differentiation of five cultural types.

Table 4.

The result of the KMO and Bartlett’s test.

Table 5.

The result of communalities.

Table 6.

The result of total variance explained.

4.1.2. K-Means Clustering

The results show highly significant between-cluster differences, minimal within-cluster variation, and adequate sample sizes (Table 7 and Table 8), indicating that the clustering successfully captured the core distinctions among the five groups along the underlying factors. The cluster structure is thus stable and reliable, supporting the hypothesis that the cultural classification reflects meaningful differentiation.

Table 7.

The significance of variables in cluster differentiation.

Table 8.

The result of the final cluster center.

4.1.3. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)

Due to the small sample size (n = 10 for regular form samples), Welch’s ANOVA was employed as a robust test to account for potential violations of the homogeneity of variances assumption (Table 9). The results revealed highly significant mean differences between the two factor groups (p < 0.001), providing empirical support for the statistical distinction between the five cultural types.

Table 9.

The result of the robust test for equality of means.

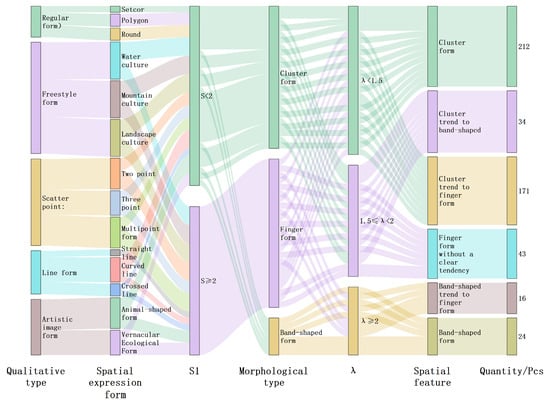

4.2. Morphological Quantification Statistics Analysis

4.2.1. The Level of the Quantitative Form Index

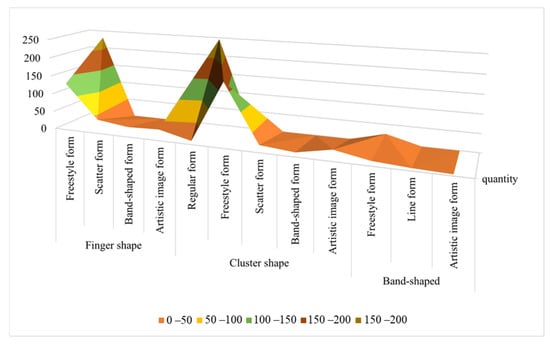

In terms of the level of the quantitative form index, the greatest proportion of Jiangnan traditional villages take the cluster form, while the smallest proportion of villages take the line form. In this study, the S value is proportional to the village shape complexity. The total percentage of cluster form and band-shaped form villages with S < 2 is 51.2%, indicating that the majority of the traditional Jiangnan villages have morphological stability, with a minimum value as low as 0.0038. The finger form villages with S > 2 account for 48.8%, suggesting that nearly half of Jiangnan villages have complex shapes, exhibiting strong morphological variability and flexibility. Among them, there are 53 pcs villages with S > 3, with values up to 11.5 (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

The quantitative form index statistic of traditional village morphology.

The S values of the Jiangnan traditional villages exhibit significant variation, with digital typologies revealing a culturally driven hierarchical structure. The proportion of the digital values of villages reveals the juxtaposition of complexity and stability in village spatial forms, embodying a metamodern philosophy. The form of each village is shaped by cultural influences, co-constructed through simplicity and complexity and stability and flexibility. Stability anchors the collective consciousness that underpins cultural identity, while flexibility anchors the wisdom that adapts to changing external environments. This reveals that village forms are not singular, static patterns.

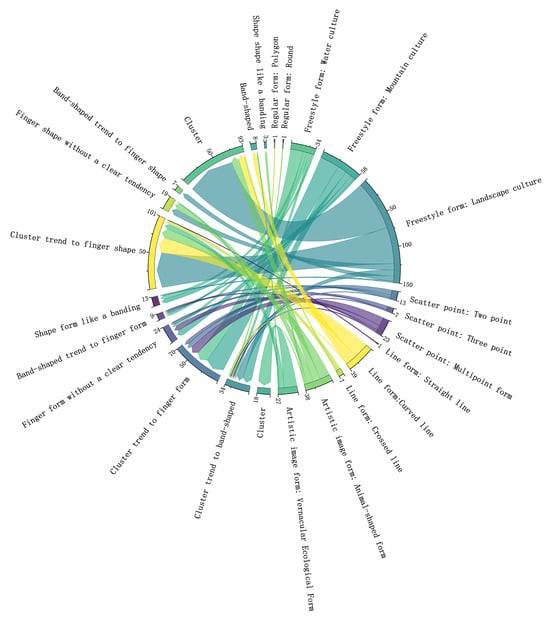

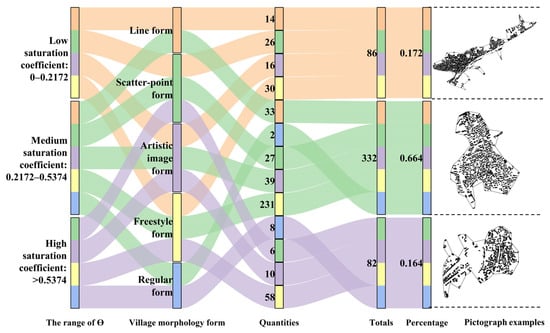

4.2.2. The Level of Cultural Qualitative Form

In terms of village types, with culture as a clue, the freestyle form is the most numerous, totaling 319 pcs and accounting for 63.8%. Within this type, landscape culture villages constitute the largest proportion, with 150 pcs in total. The artistic image form is ranked second, with 65 pcs in total, accounting for 13%. The scatter-point form and line form are ranked third, and the regular form is the least numerous, with 10 pcs. This distribution indicates that the cultural morphology of the Jiangnan traditional villages is most significantly affected by natural ecological culture, followed by vernacular feng shui culture and Chinese family clan culture. It reveals the different shaping mechanisms of cultural logic with respect to spatial forms (Figure 10). Natural ecological culture exerts the most significant influence, as water networks and topography shape the village in response to landscape variations. Vernacular feng shui culture exerts a secondary influence, offering cultural identity and emotional connection via symbolic elements such as feng shui ponds, cardinal directions, and pictographic spaces. Chinese family clan culture anchors social order through axial lines, ancestral halls, and defined boundaries, sustaining communal village stability. The dynamic interplay of these three dimensions is as follows: ecology provides environmental resilience, feng shui invigorates spiritual vitality, and family clan systems sustain social structures. This collectively drives the differentiated evolution of village spatial morphology. This process validates the living transmission and sustainability of Jiangnan culture within a metamodern context.

Figure 10.

The cultural qualitative form relationship statistics of traditional village morphologies.

4.3. Digital Analysis of Cultural Morphology

In this research, the cultural morphology result indicates an obvious relationship to the quantitative form index by comparing it to the digital spatial index. The village type indicates clear digital features that are influenced by different cultural levels (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Digital features of the cultural spatial morphological form of traditional villages.

4.3.1. Comparative Analysis of Village Morphological Complexity

- (1)

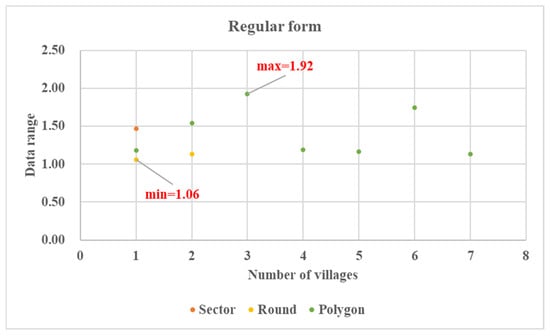

- The S of the regular form

The regular form, at the digital level, is all cluster form, S < 2. The range of S is 1.06–1.92, representing the smallest change range (Figure 12). This indicates that the village spatial morphology is uncomplicated, and the spatial shape is stable. In traditional village construction, the regular form of village space typically adapts to flat terrain, exhibiting an axis relationship influenced by family clan culture. The spatial planning is straightforward and orderly. Shape changes are uniform, which is consistent with the digital quantization S index.

Figure 12.

The shape index digital features of the regular form.

- (2)

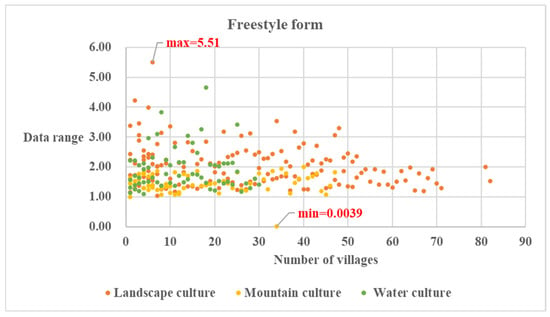

- The S of the freestyle form

In terms of the freestyle form, the range of S is 0.0039–5.51, demonstrating a substantial change range. The most abundant village according to the quantitative indices is the cluster form, with a total of 174 pcs, accounting for 54.5%. Second is the finger form, with a total of 132 pcs, accounting for 41.4%. The least abundant is the band-shaped form, with a total of 13 pcs, accounting for 4.1% (Figure 13). Based on the principle that the smaller the S value, the simpler the village morphology, 58.6% of villages show morphological stability and adaptivity under the influence of traditional nature culture. Water and road systems serve dual purposes for transportation and irrigation, while mountainous terrain provides natural defenses. These elements shape organic village layouts that adapt to the ecological environment, sustaining village communities. However, 41.4% of villages exhibit S >2, indicating that diverse geographical environments drive complex village morphology, reflecting the adaptive responses of villages to nature. Natural landscape elements provide flexible spatial boundaries, with roads, waterways, and building layouts adapting to variations. Consequently, these villages have developed an outward-looking commercial network, demonstrating cultural openness and dynamic adaptation to nature.

Figure 13.

The shape index digital features of the freestyle form.

- (3)

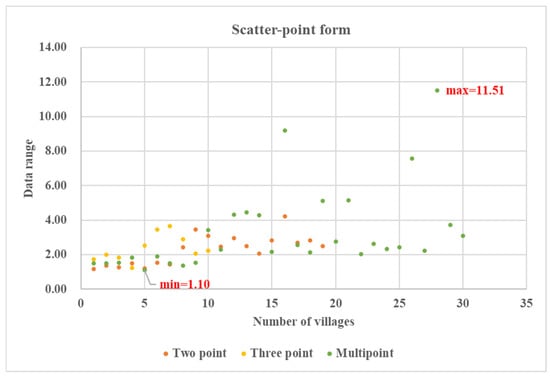

- The S of the Scatter-Point Form

In terms of the scatter-point form, the range of S is 1.10–11.51, the largest range of change. Under the quantitative indices, most villages take the finger form, with a total of 39 pcs, accounting for 66.1%. The rest take the cluster form, with a total of 20 pcs, accounting for 33.9% (Figure 14). This suggests that villages, influenced by the complex topography and clustered settlement culture of the Jiangnan region, are interconnected through a dynamic road network, with a spatial pattern of large-scale dispersion and small-scale clustering. Different clusters maintain consistency in surnames, beliefs, and agricultural practices, representing a distinctive village form shaped by local natural and cultural conditions.

Figure 14.

The shape index digital features of the scatter-point form.

- (4)

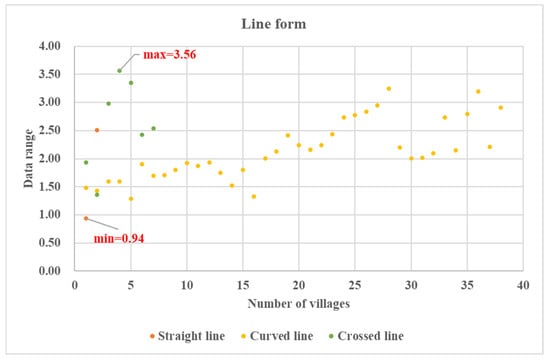

- The S of the line form

For the line form, the range of S is 0.94–3.56, and the variation range is limited. Regarding quantitative indices, the finger form is most represented among villages, with a total of 28 pcs, accounting for 59.6%. Second are cluster form villages, with a total of 12 pcs, accounting for 25.5%. The least represented village type is the band-shaped form, with only 7 pcs, accounting for 17.9%, indicating that line form villages are manifest as complex spatial structures (Figure 15). This morphology is constrained by natural conditions. Villages adopt linear layouts that follow mountain contours or waterways. Their spatial orientation is clear, emphasizing the linear trade and communication axes with internally oriented family structures. This arrangement embodies a natural cultural bond of cohesion within and connection without.

Figure 15.

The shape index digital features of the line form.

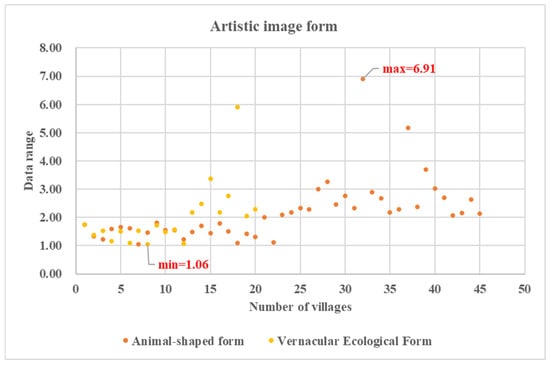

- (5)

- The S of artistic image form

In terms of the artistic image form, the range of S is 1.06–6.91, demonstrating a substantial variation range. Under the quantitative indices, the most represented of village forms is the finger form, with a total of 31 pcs, accounting for 47.7%. Second is villages of the cluster form, with a total of 30 pcs, accounting for 46.2%. The least represented is the band-shaped form, only 4 pcs, accounting for 6.1% (Figure 16). This suggests that the morphology of the artistic image form villages is changeable and flexible. Village boundaries, feng shui ponds, and alleyways are utilized, blending traditional artisans’ esthetics and craftsmanship. Forms such as the Tai Chi, dragon, and phoenix serve as emotional carriers of vernacular feng shui culture, conveying auspicious meanings and forming a quintessential spatial–physical–cultural semiosis [22].

Figure 16.

The shape index digital features of the artistic image form.

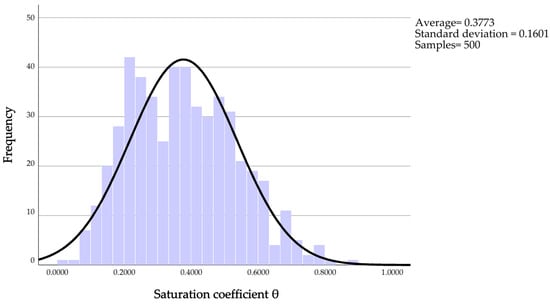

4.3.2. Comparative Analysis of Village Form External Expansion Trend

ϴ represents the external expansion trend of a village. The average ϴ is µ = 0.3773, the standard deviation of ϴ is σ = 0.1601, and the normal distribution curve is obtained (Figure 17). In the standard deviation range, µ − σ = 0.2172; µ + σ = 0.5374. We define 0–0.2172 as a low-saturation coefficient, 0.2172–0.5374 as a medium-saturation coefficient, and >0.5374 as a high-saturation coefficient.

Figure 17.

Normal distribution analysis of saturation coefficient.

The results present the following (Figure 18):

Figure 18.

The ϴ index range of traditional villages.

- (a)

- The ϴ range of the line form village was 0.10–0.53. The changeable range of ϴ was the least, with all villages concentrated in the low-to-medium saturation coefficient, indicating that the external expansion trend was weak, and the morphological form was constrained by the linear environment.

- (b)

- The ϴ range of the scatter-point form villages was 0.03–0.67. The changeable range of ϴ was large, with 89.9% of villages concentrated in the low-to-medium saturation coefficient, indicating that the external expansion trend was weak and significantly constrained by the natural geographic conditions.

- (c)

- The ϴ range of the artistic image form villages was 0.08–0.69. The changeable range of ϴ was substantial, with 75.4% of villages concentrated in the medium-to-high saturation coefficient, indicating that the external expansion trend was strong.

- (d)

- The ϴ range of freestyle form villages was 0.11–0.82. The changeable range of ϴ was the largest, with 90.6% concentrated in the medium-to-high saturation coefficient, exhibiting strong external expansion trends.

- (e)

- The ϴ range of regular form villages was 0.39–0.87. The changeable range of ϴ was small, with 100% concentrated in the medium-to-high saturation coefficient, which is a typical example of external expansion trends.

To sum up, the magnitude of ϴ correlates positively with the external expansion trend of the village. At the three levels of ϴ, the village exhibits distinct expansion trends, with a dynamic interplay between spatial closure and openness cultural influences. At the low-saturation coefficient, freestyle form villages exhibit the highest proportion due to their large overall numbers, followed by scatter-point form villages. Considering the landscape culture of the development of traditional villages in the Jiangnan region [46], scatter-point form villages were affected by the extremely changeable terrain during the construction process [47]. This resulted in villages shaped by varying natural topography, taking the form of multiple small settlements. Roads facilitate cultural connections between these settlements, yet the decline in core settlements limited outward expansion. The line form villages are influenced and restricted by linear roads or water systems. Linked by a central street, the village halls, temples, shops, and plazas form an inwardly oriented network that builds community and privacy. This indicates a blend of cultural wisdom and natural construction, harmonizing with the mountains and waterways.

Among the villages studied, ϴ peaked at 0.87, with 82.8% exhibiting medium-to-high saturation levels, reflecting a cultural focus on harmony with nature via waterways and roads that facilitated transportation and trade, hence defining Jiangnan’s distinctive historical, cultural, and commercial heritage [47]. Furthermore, the complexity of the artistic image and freestyle forms reflects the developmental and expansionary trend of Jiangnan’s flexible business culture. Regular form villages are regular precisely because of their stable structure, and road traffic is straight and flat, which promotes external development. This emphasizes the core of sustainability in village spatial culture from a metamodern perspective, transcending binary opposition and embracing a dialectical cultural logic that maintains a dynamic equilibrium between order and vitality and restraint and expansion.

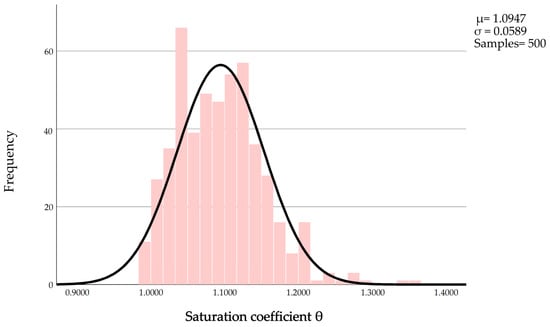

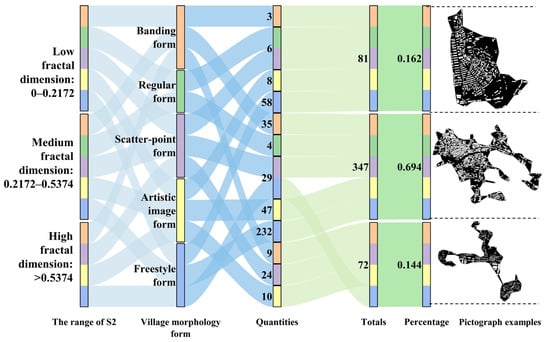

4.3.3. Comparative Analysis of Village Public Spatial Fragmentation

S2 represents the village public spatial fragmentation level. The S2 average is µ = 1.0947, the standard deviation of S2 is σ = 0.0589, and a normal distribution curve is obtained (Figure 19). In the standard deviation range, µ − σ = 1.0358; µ + σ = 1.1536. We define 0 to 1.0358 as a low fractal dimension index, 1.0358–1.1536 is defined as a medium fractal dimension index, and >1.1536 as a high fractal dimension index (Figure 20).

Figure 19.

Normal distribution analysis of the fractal dimension index.

Figure 20.

S2 index range of traditional villages.

The results reveal the following:

- (a)

- The S2 range of the regular form villages was 0.99–1.08. The changeable range of S2 was the least, with villages concentrated in the low and medium fractal dimension indices, indicating that the public village space is stable, and the spatial structure is clear.

- (b)

- The S2 range of the line form villages was 1.00–1.21. The changeable range of S2 was moderate, with 93.6% of villages concentrated in medium and high fractal dimension indices, indicating that the public space of the village is complex, with high spatial tissue efficiency.

- (c)

- The S2 range of the scatter-point form villages was 1.00–1.36. The changeable range of S2 was the highest. Among them, 89.8% of villages are concentrated in the medium and high fractal dimension indices, exhibiting strong spatial tissue efficiency.

- (d)

- The S2 range of the artistic image was 0.99–1.28. The changeable range of S2 was substantial, with 87.7% of villages concentrated in the medium and high fractal dimension indices, indicating high public spatial fragmentation and a flexible spatial structure with strong spatial tissue efficiency.

- (e)

- The S2 range of the freestyle form villages was 0.99–1.26. The changeable range of S2 was large, with 81.8% concentrated in the medium and high fractal dimension indices, indicating that the village public space shows high fragmentation.

In summary, S2 is directly proportional to the fragmentation level of the public space in the village. This indicates that within a specific area, public spaces facilitate more complex building arrangements, resulting in higher spatial efficiency. The three levels of the fractal dimension index reflect the flexibility of village public space. At low fractal dimension values, the freestyle form was most common, followed by artistic image form, but the sample number was limited to 8. This indicates that few villages in the Jiangnan region have inefficient internal organization of public spaces, reflecting a strong focus on effective organization and utilization. These public spaces, comprising squares, theater stages, and markets, serve as central hubs for daily entertainment and foster vernacular cultural cohesion. The number of villages in the medium and high fractal dimension indices was found to be as high as 83.8%. Second to freestyle form villages, the most represented are the artistic image form and the scatter-point form villages. Freestyle form villages prioritize the evolution of their natural environment, leveraging landscape elements such as roads and waterways to connect cultural hubs into a network of public spaces. The artistic image form villages translate their intrinsic spirituality and cultural–physical semiosis as landscape nodes within public spaces, creating a dynamic resonance between the physical environment and the human imagination. Despite their dispersed spatial layout, scatter-point villages demonstrate highly efficient public space organization. Driven by cultural gravity, they connect spaces through streets and alleys, utilizing the natural environment as a series of anchor points for community activities.

As S2 approaches 1.0, village spatial patches simplify geometrically, with a maximum S2 value of only 1.36 in Jiangnan. This indicates that despite variations in public space organization, it maintains stability through the focused use of public spaces, demonstrating the resilience of village public spaces formed by long-term cultural and natural processes. Public spaces serve as the cultural core of Jiangnan’s village morphology, playing a role in uniting clans, coordinating layouts, and guiding spiritual values. Natural ecological culture public spaces, dominated by natural scenery and construction activity, focus on landscape diversity. Chinese family clan culture centers public spaces around ancestral halls, temples, and prayer sites, emphasizing spatial hierarchy. Vernacular feng shui culture influences the integration of pictorial symbols with roads, ponds, and architectural groups in public spaces to instill spiritual significance. The spatial organization effectively balances adaptive order with structured stability, forming the dynamic integration of Jiangnan’s village morphology. Far from contradictory, this juxtaposition manifests a multi-layered cultural expression, reflecting the dynamic balance between existing order and external development in Jiangnan’s rural society.

5. Discussion

Jiangnan traditional villages exhibit characteristics of constructing spatial forms as objects and spirits [40]. They are affected by natural, social, and vernacular cultures, resulting in complex morphological village forms [48,49]. To elucidate the inherent culturally influenced logic of village spatial morphology, in this study, we established the CSMFC, exploring 500 representative traditional villages to validate the rationale for adopting a digital quantification of cultural perspective. This study, employing metamodern theory, used an SRM combining morphological quantification and spatial analysis techniques to facilitate objective and accurate classification of village spatial forms. The results indicate that the CSMFC indicators possess sufficient scientific significance and accuracy for digital quantitative analysis, effectively presenting village spatial morphological characteristics and cultural contexts. The specific manifestations of the digital principles of cultural spatial morphology are as follows (see Table 10):

Table 10.

The digital characteristics of village spatial morphology.

- (1)

- Regular form villages all take the cluster form at the digital level. The S is the most stable, ϴ is smaller, and the S2 is the smallest. These data indicate that this village type exhibits the simplest, most stable spatial morphology, reflecting its inherent cohesion. This stable and cohesive anchoring pattern embodies that Chinese family culture’s moderate and orderly ritual logic has shaped village form.

- (2)

- Freestyle form villages can be divided evenly into finger form and cluster form at the digital level. The S is complex, the ϴ is larger, and the S2 is the largest. This indicates that village spatial morphology is flexible, the external expansion trend is most obvious, and public space fragmentation is relatively high. This further reflects the village’s spatial resilience within natural ecology, deeply embedded with cultural intelligence. Under the influence of a changeable landscape environment, it anchors a dynamic flexibility space within the natural culture context. The highest proportion of finger form villages at the digital level is concentrated in the most complicated landscape conditions. This confirms the metamodern hypothesis of positive coupling between the mathematical complexity of village space and cultural complexity.

- (3)

- In scatter-point form villages, there are no band-shaped form villages at the digital level, which would appear to be the obvious type of spatial morphology, with the largest value of S. This indicates that village spatial morphology is most complex for this village type. ϴ is the second largest, indicating a stronger external expansion trend, while S2 is the largest, indicating low public space fragmentation. This point-dispersed spatial pattern is shaped by cultural bonds and a holistic sense of identity with the natural environment, embodying a resilience that anchors cultural roots within dispersed spaces and generates dynamic spatial forms from fragmentation.

- (4)

- The line form villages have a lower S, which means that the spatial morphology is relatively stable. The range of changeable ϴ is the smallest and the S2 is the third largest. This indicates that, despite fragmented public spaces, cultural cohesion arises through linear space. This form, following terrain-adaptive routes, anchors ecological wisdom in natural rhythms, fostering deep cultural–environmental symbiosis by curbing uncontrolled expansion.

- (5)

- In artistic image form villages, the proportion of finger form villages is the largest, and the S is as high as 6.9, indicating high spatial morphology complexity. The range of changeable ϴ is larger, and S2 is the second largest. Under the influence of feng shui culture, the village space anchors local complexity and unique variability, fostering cultural dynamism within fragmented spatial arrangements.

By expanding the village cultural morphology sample, digital quantification can more accurately reflect the underlying vernacular construction principles influenced by culture. However, this method still exhibits some shortcomings at the digital level, with specific manifestations as follows:

- (1)

- At the digital level, for the line form village, only seven villages were deter-mined to have the band-shaped form. In the village construction of traditional culture, many shapes are curved or cross lined due to natural conditions. These are required to be considered when determining the natural conditions of the village inhabitants.

- (2)

- The quantitative indices for artistic image form villages do reflect the complexity and variability in the space to a certain extent, but they are still limited to the interpretation of cultural artistic shapes. Future work is required to incorporate local legend and feng shui culture details to advance this analysis.

- (3)

- In the scatter-point form villages, the specific number of architecture groups cannot be presented, and further analysis of the settlement culture and form of the local ethic culture needs to be undertaken.

In summary, employing cultural clues and integrating digital quantification carries to refine analyses of traditional village forms not only holds methodological significance but also constitutes a metamodern cognitive pathway, that is, establishes an operational linkage mechanism between cultural meaning and spatial structure. This situational research method (SRM) aims to reveal the underlying spatial mathematical logic behind cultural practices. For instance, feng shui in village site selection, influenced by culture, ritual sequences in layout, and circulation patterns within spatial networks, can be identified and modeled through digital technology [50,51]. According to the digital standard, the conservation of traditional villages can shift from static restoration toward a precise intervention approach that equally emphasizes dynamic anchoring and cultural context [27]. The digitization of village spatial forms enables a shift from vague experiential descriptions to precise identification that is measurable, comparable, and verifiable [52]. Meanwhile, in-depth qualitative field data provide algorithms with a rich cultural context, preventing data from losing meaning. The two elements oscillate and mutually reinforce each other, enabling precise classification and interpretation of village typologies. Moreover, by structurally encoding and digitally translating cultural elements, this approach provides scientific foundations for optimizing village spatial morphology, integrating cultural functions, and facilitating adaptive renewal. This methodology sublates technological determinism and cultural nostalgia, anchoring cultural essence while activating spatial processes to shift heritage preservation from static conservation to dynamic transmission [27]. Specifically, determining the refined management and heritage of village morphology types in the cultural blending area requires combining cultural and digital approaches [53]. The workload for cultural factor indices is substantial, particularly as folk customs and traditional feng shui exhibit abstract and imprecise features of village social culture [54,55]. This needs further refinement and exploration to address the issue of cultural heritage deficiency in contemporary village spatial forms. Although this study identified five types and fourteen spatial expression forms, the CSMFC system can be applied to a broader range of village morphology types and their impact factors. The SRM from a metamodern perspective does not merely reconcile quantitative and qualitative methods but emphasizes cultural heritage sustainability as a dynamic complex of meaning and materiality through a relational, processual, and oscillatory philosophical lens. Within the CSMFC framework, heritage conservation is no longer merely about safeguarding physical spaces but concerns a creative practice that sustains cultural continuity globally. It sublates rigid, binary frameworks and emphasizes the complementary roles of qualitative and quantitative approaches in village spatial studies.

6. Conclusions

The traditional village morphology contains tangible spatial forms and intangible cultural and spiritual spaces. The natural geomorphological environment forms a stable organic system through a dynamic interplay of architecture and local culture [56,57]. The contemporary village has gone beyond a singular, static, or purely traditional entity into a metamodern spatial concept characterized by oscillation, contradiction, layered realities, and creative synthesis. It is traditional and modern, local and global, intangible and tangible, with its meaning continuously re-anchored through the ongoing interplay of spatial materiality and cultural–physical semiosis. Its developmental trajectory demands a humble yet pragmatic approach, deploying diverse tools and methods to navigate the tensions between sustainable conservation and revitalization.

The study of the cultural context of village morphology provides a comparative perspective on rural cultural evolution and related sociological research [58,59]. This study serves as a research framework and methodology for exploring traditional village spatial morphologies under the cultural context. The significance of village spatial morphology lies not only in analyzing spatial principles but also in discovering and understanding the unique cultural context that underlies its logical structure and growth. The sustainable heritage conservation of traditional villages should be grounded in the dynamic systems of living culture. These three cultural dimensions of village-driven spatial organizational patterns could be operationalized as assessment indicators in local heritage policies [60]. Chinese family clan culture needs to optimize clan organizations of public spaces and road systems. Natural ecological culture can integrate environmental resilience boundaries to enhance ecological sustainability. Vernacular feng shui villages require safeguarding the integrity of folk–spiritual–physical–cultural semiosis to emphasize local vitality. Crucially, conservation strategies should support the contemporary adaptation of spatial cultural heritage, rather than confining efforts to the static preservation of forms [61].

Owing to the influence of multicultural humanistic influence and local imagination, the spatial form of Jiangnan traditional villages exhibits distinct local attributes [62,63,64]. The natural structure incorporates external space conditions into Jiangnan traditional villages’ layout, harmonizing vernacular sociocultural elements [65]. Through continuous adaptation and expansion, a stable tangible environmental structure has taken shape, embodying a unique cultural context. In heritage sustainable conservation research, scholars should focus on latent vitality and contingent events to gain profound insights into their impacts and developmental trends. The traditional village demands balanced digital technological innovation and deep on-site investigation. In particular, it is imperative for cultural heritage studies to explore the connections between spatial morphology and potential, incidental cultural events [66]. Therefore, viewed through a metamodern lens, traditional villages are actively emerging as a frontier for complex cultural production and social experimentation. Its dynamic, oscillating form represents a localized, vibrant response to the homogenizing trends of contemporary development. This study has employed an iterative methodological oscillation between quantitative and qualitative methods, creating a continuous process of integration and cyclical interaction. In exploring the sustainability of village cultural heritage within contextual frameworks, maintaining a clear oscillatory process while anchored is essential. Therefore, future research activities should include the following: (1) the combination of village vernacular cultural characteristics data, such as ethnic customs, architectural styles, and construct art, to further refine the situational research method; and (2) the incorporation of data on population, land use, topography, and other factors to explore the multidimensional dynamic oscillation processes within village spatial morphology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L. and Y.Z.; methodology, X.L. and Y.L.; software, M.S. and Y.Z.; validation, X.L., Y.Z. and A.Z.; formal analysis, M.S. and W.F.; investigation, X.L. and Y.Z.; resources, X.L. and Y.Z.; data curation, Y.Z., Y.L. and A.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, X.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.L.; visualization, M.S. and Y.Z.; supervision, A.Z.; project administration, X.L.; funding acquisition, X.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was supported by the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Grant number: ZR2022QE296); the project name is Spatial Pedigree Construction of Traditional Village and Its Influence Mechanism in Jiaodong Peninsula Based on ArcGIS. “The APC was funded Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation”.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their gratitude to Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation. And the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Construction of the People’s Republic of China for their help with the information about traditional villages. Additionally, the School of Architecture, Yantai University, offered assistance with technical analysis software and mapping instrumentations. Special thanks to the reviewers and editor for very useful comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

The timeline analysis of the spatial morphology of traditional villages. “#” represent the key word in this figure.

Appendix B

Figure A2.

The research hotspot graph analysis of the spatial morphology of traditional villages. “#” represent the key word in this figure.

References

- Nie, Z.; Chen, C.; Pan, W.; Dong, T. Exploring the Dynamic Cultural Driving Factors Underlying the Regional Spatial Pattern of Chinese Traditional Villages. Buildings 2023, 13, 3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Q.; Aimar, F. How Are Historical Villages Changed? A Systematic Literature Review on European and Chinese Cultural Heritage Preservation Practices in Rural Areas. Land 2022, 11, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thinh, N.K.; Kamalipour, H.; Gao, Y. Mapping the Emerging Forms of Informality: A Comparative Morphogenesis of Villages-in-the-City in Vietnam. Habitat Int. 2023, 138, 102864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlovič, R.; Matlovičová, K. The Metamodern Shift in Geographical Thought: Oscillatory Ontology and Epistemology, Post-Disciplinary and Post-Paradigmatic. Folia Geogr. 2025, 67, 22–69. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Bi, S.; Qin, L.; Yu, K. Research on the Regenerative Design and Practice of the Residential Architecture Atlases in Jiangnan during the Ming and Qing Dynasties: A Case Study of the Mingyue Bay Village in Suzhou. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 24, 3381–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, C. The Spatial Pedigree in Traditional Villages under the Perspective of Urban Regeneration—Taking 728 Villages in Jiangnan Region, China as Cases. Land 2022, 11, 1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Chen, J.; Liu, L.; Guo, L. A Review: How Deep Learning Technology Impacts the Evaluation of Traditional Village Landscapes. Buildings 2023, 13, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wei, X.; Yan, X.; Sohaib, O. A Study on Sustainable Design of Traditional Tujia Village Architecture in Southwest Hubei, China. Buildings 2024, 14, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Lv, Q. Multi-Dimensional Hollowing Characteristics of Traditional Villages and Its Influence Mechanism Based on the Micro-Scale: A Case Study of Dongcun Village in Suzhou, China. Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xie, W.; Li, H. The Spatial Evolution Process, Characteristics and Driving Factors of Traditional Villages from the Perspective of the Cultural Ecosystem: A Case Study of Chengkan Village. Habitat Int. 2020, 104, 102250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, Y. Analysis of Spatial Genes and Research on Influencing Mechanisms of Oasis Rural Settlements on the Northern Slope of Tianshan Mountains. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2024, 3, 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Zhou, S.; Tang, X.; Zhu, W.; Zhou, P.; Xiao, G. Mountainous Village Relocation Planning with 3D GIS Virtual Imaging Space Model and Neural Network. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2023, 22, 2392–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Dai, Y.; Zan, P.; Zhang, S.; Sun, X.; Zhou, J. Research and Evaluation of the Mountain Settlement Space Based on the Theory of “Flânuer” in the Digital Age—Taking Yangchan Village in Huangshan City, Anhui Province, as an Example. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 23, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, H.; An, Y. Spatial Morphology and Geographic Adaptability of Traditional Villages in the Hehuang Region, China. Buildings 2025, 15, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.; Wang, J.; Li, L.; Chen, D. Extraction and Analysis of the Spatial Morphology of a Heritage Village Based on Digital Technology and Weakly Supervised Point Cloud Segmentation Methods: An Innovative Application in the Case of Xisongbi Village in Jiexiu City, Shanxi Province. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.; Wang, L. Morphological Typology Pedigree of Centripetal Spatial Schema in Traditional Chinese Settlements. Front. Archit. Res. 2024, 13, 1198–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapoport, A. House Form and Culture; Prentice Hall: London, UK, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Vellinga, M. Living Architecture: Re-Imagining Vernacularity in Southeast Asia and Oceania. Fabrications 2020, 30, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, D. Built to Meet Needs: Cultural Issues in Vernacular Architecture—By Oliver, Paul. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. 2010, 16, 165–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Liu, S. Spatial Morphological Characteristics and Evolution of Traditional Villages in the Mountainous Area of Southwest Zhejiang. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, Y. Traditional Village Landscape Identification and Remodeling Strategy: Taking the Radish Village as an Example. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2022, 2022, 2350310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Shao, M.; Yang, H. Observing Meaning through Form and Transcending Images: Decoding the Artistic Intention of Creation Path of Contemporary Space Art in Traditional Jiangnan Villagesa. Des. Res. 2024, 15, 144–148. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Xu, W.; Xiao, Y.; Shi, J.; Hu, X.; Yan, B. Temporal and Spatial Patterns of Traditional Village Distribution Evolution in Xiangxi, China: Identifying Multidimensional Influential Factors and Conservation Significance. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, X.; Zhu, Z.; Dong, Y.; Lao, Y. Research on the Method of Generating Border Forms of Rural Settlements. Archit. Cult. 2024, 4, 80–83. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, W.; Xiao, D.; Zhao, Y.; Tao, J.; Zhuo, X.L. Study on the Cultural Landscape Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Traditional Villages and Dwellings in Central Yunnan Region. Archit. J. 2023, A1, 194–200. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Xia, X.; Wu, S. Genetic Characteristics Evaluation and Planning Design of Traditional Village Cultural Landscape: Taking Dongmen Fishing Village in Xiangshan, Zhejiang Province as an Example. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 24, 4572–4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; Xu, Q.; Yu, X. Mixed-Method Study of the Etiquette and Custom Cultural Activity Space and Its Construction Wisdom in Bubeibu Traditional Village, Yuxian County, China. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 23, 2100–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Z.; Li, N.; Pan, W.; Yang, Y.; Chen, W.; Hong, C. Quantitative Research on the Form of Traditional Villages Based on the Space Gene—A Case Study of Shibadong Village in Western Hunan, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storm, J.A.J. Metamodernism. The Future of Theory; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Severynova, M.; Kharchenko, P.; Chibalashvili, A.; Bezuhla, R.; Putiatytska, O. Transformations of the Contemporary Art Practices in the Context of Metamodern Sensibility. Open Cult. Stud. 2025, 9, 20250053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lvov, A.A. The Practices of Historicism in Metamodern Condition. Vestn. Saint Petersbg. Univ. Philos. Confl. Stud. 2024, 40, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaiduk, N.; Tarapatov, M. Theoretical Background to Metamodernism as the New Form of Modern Culture. Natl. Acad. Manag. Staff Cult. ARTS Her. 2022, 1, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Ye, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Wu, W. Space Gene Quantification and Mapping of Traditional Settlements in Jiangnan Water Town: Evidence from Yubei Village in the Nanxi River Basin. Buildings 2025, 15, 2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traditional Chinese Village Digital Museum. Available online: http://www.dmctv.cn/ (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Research Center for the Protection and Development of Chinese Traditional Villages Chinese Traditional Village. Available online: http://www.chuantongcunluo.com/index.php/Home/Gjml/gjml/id/24.html (accessed on 7 June 2022).

- Hu, B.; Li, X.; Wang, X. 2017 Survey Report on the Protection of Traditional Villages in China; Social Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- China National Bureau of Statistics. China Rural Statistical Yearbook (2023); China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2023.

- Shi, D.; Qu, Y. China Rural Revitalization Yearbook 2022; Economy & Management Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Angelidou, I. The Three States of the Architectural Fragment as a Collective Archive of Concepts: Tracing an Alternative Genealogy of Aldo Rossi’s Analogous Cities. Getty Res. J. 2022, 16, 137–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, S.; Du, J.; Tian, Z.; Zhang, Y. Investigating the Spatial Distribution Mechanisms of Traditional Villages from the Human Geography Region: A Case Study of Jiangnan, China. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 81, 102649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.; Xie, J.; Wang, H.; Wu, H. Application and Indication of Confucianism in Environmental Planning of Chinese Traditional Dwellings. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2021, 42, 203–209. [Google Scholar]

- Bu, Y.; Lai, P. Research on the Morphological Typology of Traditional Villages in the Fujiang River Basin in the Multicultural Interlaced Area. Archit. J. 2024, A2, 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Fan, W.; Liu, L. Identification and Optimization of Traditional Village Morphology from the Perspective of Material-Cultural Interaction: A Case Study of Miaoxia Village, Chenzhou City, Hunan Province. J. Ecol. Rural Environ. 2025, 41, 86–98. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H.; Yang, C. The Spatial Form of Traditional Villages DSM in Western Liaoning. J. Dalian Polytech. Univ. 2019, 5, 386–390. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Liao, Z.; Wu, Y.; Degefu, D.M. Cultural Sustainability and Vitality of Chinese Vernacular Architecture: A Pedigree for the Spatial Art of Traditional Villages in Jiangnan Region. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yan, Y.; Sun, S.; Xu, X.; Higueras, E. Effect of the Spatial Form of Jiangnan Traditional Villages on Microclimate and Human Comfort. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 87, 104136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. Net Income Per Capita in Rural Wuxi, 1840s–1940s. J. Econ. Soc. Hist. Orient 2014, 57, 291–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Yin, H.; Xin, X.; Ting, Z.; Ning, C.; Li, S.; Yun, Y. A Study on the Spatial Form of Traditional Villages in Jiangnan Region of China from the Perspective of Human Thermal Comfort: A Case Study of Nanjing, Jiangsu Province. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0323252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tian, Z.; Du, J.; Bi, S. Multidimensional Evaluation of Traditional Villages in Jiangnan Region, China: Spatial Pattern, Accessibility and Driving Factors. Buildings 2024, 14, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Xiao, D.; Liu, Y. Spatial Morphology and Influencing Factors of Tunpu Traditional Villages in Anshun: A Comprehensive Study. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 24, 3457–3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Luo, Z.; Huang, K. Characterization of Public Space Forms in Traditional Chinese Villages Based on Spatial Syntax: Zhangli Village as an Example. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 24, 3030–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Chen, C.-P.; Chou, R.-J.; Luo, H.; Hou, J.-S. Exploring the Transformation in the ‘Spirit of Place’ by Considering the Changed and Unchanged Defensive Spaces of Settlements: A Case Study of the Wugoushui Hakka Settlement. Land 2021, 10, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.; Zhang, Y.; Han, W. Architectural Heritage Preservation for Rural Revitalization: Typical Case of Traditional Village Retrofitting in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Tian, L.; Zhou, L.; Jin, C.; Qian, S.; Jim, C.Y.; Lin, D.; Zhao, L.; Minor, J.; Coggins, C.; et al. Local Cultural Beliefs and Practices Promote Conservation of Large Old Trees in an Ethnic Minority Region in Southwestern China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 49, 126584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yan, Y.; Ying, Z.; Zhou, L. Measuring Villagers’ Perceptions of Changes in the Landscape Values of Traditional Villages. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. The Use of Heritage in the Place-Making of a Culture and Leisure Community: Liangzhu Culture Village in Hangzhou, China. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2024, 30, 1423–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Fu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wu, S.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y. Quantitative Research on the Degree of Disorder of Traditional Settlements: A Case Study of Liangjia Village, Jingxing, Hebei Province. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Ryan, C.; Deng, Z.; Gong, J. Creating a Softening Cultural-Landscape to Enhance Tourist Experiencescapes: The Case of Lu Village. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2024, 53, 101245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, K.; Buyandelger, K. Construction of a Type Knowledge Graph Based on the Value Cognitive Turn of Characteristic Villages: An Application in Jixi, Anhui Province, China. Land 2023, 13, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zou, Y.; Yao, S.; Cao, X. Evaluation and Optimization of Cultural Ecosystem Services in Rural Areas from the Perspective of Residents:A Case Study of Sishili River Valley in Zhejiang Province. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2024, 21, 9458–9469. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Li, E.; Xiao, D. Conservation Key Points and Management Strategies of Historic Villages: 10 Cases in the Guangzhou and Foshan Area, Guangdong Province, China. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2022, 21, 1320–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Li, Z.; Xia, S.; Gao, M.; Ye, M.; Shi, T. Research on the Spatial Sequence of Building Facades in Huizhou Regional Traditional Villages. Buildings 2023, 13, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Li, Z. Cultural Ecology Cognition and Heritage Value of Huizhou Traditional Villages. Heliyon 2022, 8, e12627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, J.; Chen, W.; Zeng, J. Spatial Distribution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Traditional Villages in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Li, J.; Ding, W. Geomorphological Change and Rural Settlement Patterns: Study of the Formation Mechanisms of Strip Villages in Jiangsu, China. River Res. Appl. 2023, 39, 1300–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, T.; Ma, L.; Zhou, W.; Dai, L. Traditional Village Digital Archival Conservation: A Case Study from Gaoqian, China. Arch. Rec. J. Arch. Rec. Assoc. 2023, 44, 202–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.