Abstract

Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) initiatives have gained increasing attention in the hotel industry, yet the consumer-level psychological processes through which such activities relate to booking intentions remain incompletely understood. This study aims to examine how hotel ESG activities are associated with consumers’ booking intentions by focusing on the mediating roles of corporate image and consumer trust, as well as the moderating role of environmental awareness. Survey data were collected from consumers with recent hotel stay experiences in China and analyzed using a dual-method approach, combining partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) and fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA). The results show that social and governance activities are positively associated with corporate image, whereas environmental and social activities are positively associated with consumer trust. Corporate image and consumer trust are, in turn, associated with higher booking intentions, while environmental awareness strengthens only the relationship between environmental activities and corporate image. In addition, the fsQCA results reveal multiple configurational pathways through which different combinations of ESG activities and consumer psychological responses are associated with high booking intention. Overall, the findings suggest that hotel ESG initiatives relate to booking intentions through differentiated psychological mechanisms and multiple pathways.

1. Introduction

With the escalating global awareness of issues such as air pollution, water contamination, and waste disposal, achieving environmental sustainability has become a fundamental requirement for corporate operations (Skogen et al., 2018 [1]; Kang & Jung, 2020 [2]). As one of the world’s largest economic sectors, accounting for nearly 10% of global GDP, the tourism industry plays a pivotal role in driving global economic growth while simultaneously facing increasing pressure to adopt sustainable activities (dos Santos et al., 2020 [3]). However, despite its substantial contribution to employment and income generation, the industry exerts considerable environmental pressure, with the hotel sector emerging as one of its largest contributors. In 2016, the hotel industry accounted for around 21% of total carbon emissions from the tourism sector, a figure projected to rise to 25% by 2035 if current growth trends persist (Bianco et al., 2023 [4]). These escalating environmental challenges have driven hotels to adopt environmentally responsible management strategies, including reducing resource-intensive and ecologically harmful activities such as excessive consumption of water, energy, and single-use products, as well as the discharge of pollutants into air, water, and soil (Han et al., 2011 [5]; Casado-Díaz et al., 2020 [6]).

ESG activities have evolved from being a foundational component of sustainable management to becoming a critical framework for evaluating firms’ long-term sustainability and responsible management in the contemporary business environment (Shin et al., 2025 [7]). Since the United Nations formally institutionalized Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in 1999, the integration of sustainability into corporate strategies has accelerated, emphasizing the balance between profitability and social accountability. Reflecting the global institutionalization of sustainability, the United Nations Global Compact (UNGC) introduced the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) framework in 2004, providing a structured analytical perspective that evaluates corporate responsibility across three assessable dimensions: environmental, social, and governance. Subsequently, the United Nations formally introduced the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015, further strengthening the global sustainability agenda through 17 internationally recognized goals designed to foster synergy between economic development, environmental protection, and social well-being. The hospitality industry has long faced criticism for its significant environmental impact arising from excessive resource consumption and waste generation (Lee et al., 2025 [8]). In this context, the integration of ESG principles into corporate strategy has emerged as a key pathway for hotels to mitigate environmental pressures, enhance social legitimacy, and strengthen governance transparency, ultimately contributing to sustainable organizational development. Accordingly, many hotels have begun implementing ESG-driven activities, such as the adoption of renewable energy sources, green procurement, and the development of sustainable facilities, in alignment with the global sustainability agenda (Velaoras et al., 2025 [9]).

Sustainability has increasingly been acknowledged as an essential pillar of effective hotel management (Yarimoglu & Gunay, 2020 [10]). Recent studies indicate that approximately 79% of travelers express a desire to engage in more sustainable forms of travel (Shin et al., 2025 [7]). This tendency has become more pronounced in the post-COVID-19 era, as the pandemic has led consumers to re-evaluate their consumption patterns and priorities. However, positive attitudes toward sustainable travel do not always translate directly into actual booking behaviors. In the hotel context, although some travelers express a preference for sustainable hotels, their final choices may still be influenced by multiple factors, such as price, service convenience, and comfort (Kim et al., 2024 [11]). This phenomenon suggests that consumer support for sustainable hotels is context-dependent and requires further explanation through more nuanced psychological mechanisms.

Nevertheless, certain environmentally friendly activities may be perceived by consumers as compromises in service quality or guest comfort, for instance, encouraging guests to reuse towels or reducing the provision of disposable in-room amenities (Casado-Díaz et al., 2020 [6]). Although prior studies suggest that hotel sustainability activities do not always translate directly into consumers’ accommodation decisions and that their effects on booking behavior may vary across contexts (Rahman et al., 2023 [12]), amid increasing external environmental uncertainty, sustainability has evolved into an unavoidable strategic consideration for hotel firms in maintaining competitiveness (Fang & Zaman, 2025 [13]). Consequently, how to advance sustainability objectives while simultaneously addressing consumers’ perceived experiences and behavioral responses has become a critical managerial issue for hotel firms.

Existing research on ESG in the hotel industry has largely emphasized macro-level outcomes, such as financial performance (Ding & Tseng, 2023 [14]), investment indicators (Yu et al., 2025 [15]), and operational efficiency (Chung et al., 2024 [16]). At the consumer level, prior studies have also examined hotel sustainability activities from perspectives such as corporate social responsibility (CSR) (Zhang et al., 2019 [17]), green management (Wu et al., 2024 [18]), and environmentally friendly activities (Mugiarti et al., 2022 [19]), focusing on their effects on consumer attitudes, corporate image, and behavioral intentions. However, compared with the extensive discussion of environmental activities, how the social and governance dimensions are perceived by consumers and incorporated into booking decisions in hotel contexts remains insufficiently examined. Most existing studies treat sustainability or ESG activities as an aggregated concept, providing limited insight into the differentiated roles of the environmental, social, and governance dimensions in shaping consumer cognition and psychological responses. However, in hospitality settings, certain green measures may diminish service quality or comfort, leading to ambivalent consumer responses (Casado-Díaz et al., 2020 [6]). Against this backdrop, the present study focuses on the differentiated pathways through which the three ESG dimensions operate in the hotel industry and systematically examines how they influence booking intentions through corporate image and consumer trust. By adopting a multi-method analytical approach, this study seeks to refine our understanding of the psychological mechanisms linking hotel ESG activities to consumer behavior and provide more targeted empirical insights for hotels striving to balance sustainability objectives with consumer experience.

In addition, consumers’ perceptions and evaluations of hotel firms’ ESG activities may vary depending on individual differences. Understanding whether and how such differences influence the effectiveness of sustainability communication strategies is essential for hotels seeking to strengthen their corporate image and competitive advantage (Fang et al., 2025 [13]). Among individual traits, environmental awareness, referring to one’s awareness of ecological issues and willingness to engage in their mitigation (Dunlap et al., 2002 [20]), has been widely acknowledged as a key psychological driver of environmentally responsible behavior (Laroche et al., 2002 [21]; Jeong & Jang, 2011 [22]; Guo et al., 2019 [23]). Prior research further indicates that consumers with higher levels of environmental awareness are more attentive to firms’ environmental and social responsibility performance and may adjust their evaluations and behavioral responses accordingly. Accordingly, environmental awareness may serve as a moderating factor in the relationship between hotels’ ESG activities and consumers’ cognitive responses, influencing how consumers interpret and respond to hotels’ ESG activities. Nevertheless, empirical evidence on how environmental awareness moderates the relationship between hotels’ ESG engagement and consumers’ perceptions of corporate image and trust formation in hotel contexts remains limited.

Building on the preceding theoretical discussion, this study aims to address the following core research questions (RQs): RQ1: How do the environmental, social, and governance dimensions of hotel firms’ ESG activities influence corporate image, consumer trust, and ultimately booking intentions? RQ2: What mediating effects do corporate image and consumer trust exert in linking ESG engagement to booking intentions? RQ3: Does consumers’ environmental awareness moderate the relationships among ESG activities, corporate image, and consumer trust?

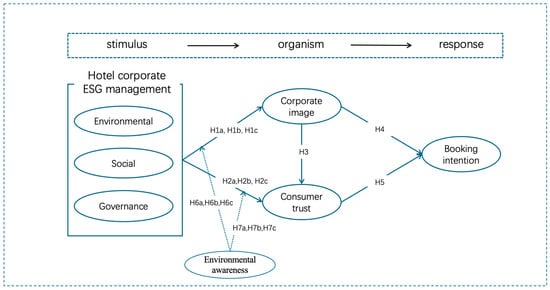

To investigate these research questions, this study employed the Stimulus–Organism–Response (S–O–R) framework to structure the relationships among key variables and clarify the explanatory pathways. This framework emphasizes that external cues, as stimuli, influence individuals’ internal cognitive and affective states, as organisms, which are subsequently associated with their behavioral responses (Jacoby, 2002 [24]). In the context of hospitality, hotels’ ESG activities serve as stimuli (S) that may shape consumers’ perceptions of corporate image and trust as organismic states (O), and are associated with behavioral responses (R), such as booking intentions. From an analytical perspective, this study employed PLS-SEM to examine linear relationships as well as mediating and moderating paths among the focal constructs and further integrates fsQCA to identify multiple configurational pathways that may lead to high booking intentions. Through this complementary analytical approach, the study aims to provide a more fine-grained understanding of the mechanisms and boundary conditions linking the three ESG dimensions, corporate image, consumer trust, and booking intentions within the established theoretical framework. In addition, environmental awareness was incorporated as a moderating variable to examine whether individuals’ ecological value orientations influence how ESG cues are processed and the strength of their effects on corporate image and trust formation.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 outlines the theoretical foundation and formulates the research hypotheses. Section 3 explains the research design, encompassing data collection procedures and analytical methods. Section 4 reports the empirical results, while Section 5 interprets these findings and highlights their theoretical and managerial contributions. Finally, Section 6 summarizes the key conclusions and provides directions for future inquiry.

2. Theoretical Background and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Stimulus–Organism–Response (S–O–R) Theory

Originating in environmental psychology, the Stimulus–Organism–Response (S–O–R) framework (Russell, 1974 [25]) proposes that external environmental cues elicit cognitive and emotional reactions within individuals, thereby guiding their subsequent behavioral intentions or actions. This theoretical framework elucidates how environmental cues, particularly information based or symbolic market signals, such as price, brand, store atmosphere, or advertising messages, shape individuals’ cognitive and emotional states and ultimately influence decision making and behavioral responses (Arora, 1982 [26]; Jacoby, 2002 [24]). Due to its explanatory power in linking external cues to internal psychological processes and observable behavior, the S–O–R framework has been extensively applied in psychology, marketing, and education to examine how individuals respond to environmental stimuli under conditions of information asymmetry or decision uncertainty (Pandita et al., 2021 [27]; Hochreiter et al., 2022 [28]).

The S–O–R framework provides a suitable conceptual foundation for this study for three primary reasons. First, in the context of hotel ESG activities, consumers often have limited ability to directly observe or verify firms’ sustainability practices and therefore rely on externally communicated information cues when forming their evaluations. The S–O–R framework, which explains how external stimuli shape internal cognitive states and subsequent behavioral responses, offers an appropriate analytical logic for understanding how ESG related information is perceived by consumers (Asyraff et al., 2023 [29]). Second, the framework allows key psychological mechanisms, such as corporate image and consumer trust, to be examined as intervening processes within a unified structure, thereby clarifying how ESG practices are associated with booking intentions (Kim et al., 2020 [30]; Ngah et al., 2019 [31]). Finally, as a well-established and context adaptable theoretical framework, the S–O–R framework has been widely applied in sustainable consumption research and is suitable for analyzing how hotels’ environmental, social, and governance practices relate to consumer decision making.

In hospitality and tourism research, psychological and behavioral theories have garnered increasing attention from scholars and practitioners (Stergiou & Airey, 2018 [32]; Thirumoorthy& Wong, 2015 [33]). The S–O–R framework has been widely adopted in studies on sustainable hospitality to explain how responsibility related practices influence consumer responses through cognitive and affective evaluations. In such contexts, consumers often have limited ability to directly observe or fully verify firms’ actual sustainability practices and therefore rely primarily on observable information cues communicated by firms. This characteristic renders hotels’ sustainability and ESG practices inherently information asymmetric, such that consumers form overall evaluations and trust judgments by interpreting responsibility related signals (Connelly et al., 2011 [34]). For instance, prior research has shown that green hotels’ corporate social responsibility practices and environmentally friendly initiatives significantly shape consumers’ perceptions of corporate image and credibility, which subsequently elicit positive emotional and behavioral responses (Su & Swanson, 2019 [35]; Fatma & Khan, 2024 [36]; Liu et al., 2025 [37]). Collectively, these studies suggest that in hospitality service settings, consumers do not respond to responsible practices per se, but rather to their subjective interpretations of responsibility related information cues, which in turn influence trust formation and decision making.

Moreover, attributes such as guest well-being, energy efficiency, and green landscapes have been shown to foster favorable guest reactions (Balaji et al., 2019 [38]). From a consumer perspective, such sustainability related attributes tend to influence responses by shaping perceptions of corporate responsibility and credibility. Consistent with prior extensions of the S–O–R framework in hospitality research, organizational factors such as employee hospitality behavior, corporate reputation, and corporate social responsibility can be viewed as important antecedents of consumers’ service experiences. Building on this application-oriented framework, the present study conceptualizes hotel ESG activities as external stimuli (S), corporate image and consumer trust as organismic states (O), and booking intentions as the behavioral response (R). This provides a structured approach to examining how ESG practices influence consumers’ booking-related intentions.

2.2. ESG Management and Sustainable Development Goals in the Hotel Industry

Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) management has emerged as a critical strategic approach for achieving corporate sustainability. Unlike traditional management practices that primarily emphasize financial performance and profitability, ESG management focuses on mitigating the long-term environmental and social consequences of business operations while enhancing governance effectiveness and transparency (Galbreath, 2010 [39]). By reducing ecological and social externalities and strengthening responsible governance practices, ESG management supports firms’ sustainable development. Over time, ESG considerations have evolved beyond their original financial context to become an important influence on both managerial decision making and consumer behavior (Lee & Rhee, 2023 [40]). From a consumer perspective, ESG practices function as salient informational cues that signal firms’ responsibility orientation and underlying values, thereby shaping overall evaluations. This role is particularly pronounced in the hospitality industry, where services are experiential and difficult to assess prior to consumption. Accordingly, consumers tend to rely on hotels’ disclosed ESG initiatives when forming judgments (Fatma & Khan, 2024 [36]; Liu et al., 2025 [37]). Consistent with prior research, ESG initiatives not only enhance hotels’ operational efficiency and reputation (Liu et al., 2025 [37]) but also stimulate consumer trust and other favorable responses (Yu et al., 2024 [41]).

In hotel booking contexts characterized by information asymmetry, consumers often have limited ability to fully evaluate hotels’ operational quality and sustainability practices prior to consumption (Fatma & Khan, 2024 [36]). When such asymmetry exists, firms may reduce uncertainty by conveying costly and credible signals to external stakeholders (Connelly et al., 2011 [34]). In this regard, hotels’ disclosed ESG practices can be viewed as important informational signals that communicate firms’ responsibility orientation, managerial quality, and long-term commitment to consumers (Liu et al., 2025 [37]). Compared with conventional marketing communications, ESG-related initiatives typically involve sustained investments and institutional arrangements, making them more likely to be perceived as credible cues (Lee & Rhee, 2023 [40]). Although consumers cannot directly observe firms’ internal governance structures, they may infer governance quality from externally disclosed cues, such as transparency and responsibility commitments (Koh et al., 2022 [42]). Prior research indicates that hotel ESG practices significantly shape consumers’ perceptions of corporate image and credibility, thereby influencing trust formation and behavioral responses (Lee & Rhee, 2023 [40]). Accordingly, ESG practices can be expected to relate to consumers’ booking intentions through cognitive evaluations, particularly corporate image and consumer trust.

2.3. Corporate Image and Consumer Trust

2.3.1. Corporate Image

Corporate image refers to the set of associations stored in consumers’ memories that reflect their overall perceptions, evaluations, and attitudes toward a company (Keller, 1993 [43]). A favorable corporate image functions as a strategic intangible asset, shaping consumers’ preferences, loyalty, and trust toward the brand (Nyadzayo et al., 2016 [44]; Molinillo et al., 2017 [45]). Within hospitality contexts, corporate image is widely acknowledged as a major factor guiding consumers’ decision-making during the booking process (Mohammad et al., 2024 [46]). When customers perceive a hotel positively, they tend to form favorable judgments and demonstrate a stronger purchase intention, underscoring the decisive role of corporate image in hotel selection (Ryu et al., 2019 [47]).

Firms that actively implement ESG-driven practices can enhance their reputation and strengthen their corporate image by signaling positive values to external stakeholders through investments in environmental protection, social responsibility, and governance transparency (Lew et al., 2024 [48]). From a consumer decision-making perspective, ESG-related initiatives not only reflect firms’ commitment to environmental and social responsibility, but also convey governance quality and long-term strategic orientation, thereby shaping consumers’ overall evaluations under conditions of information incompleteness (Yu et al., 2024 [41]). According to Lee and Rhee (2023 [40]), a company’s environmental (E), social (S), and governance (G) activities each exert significant and positive effects on its corporate image. Specifically, environmental and social practices contribute to the formation of a responsible corporate image, whereas governance-related initiatives enhance consumers’ perceptions of firms’ professionalism and ethical standards by improving transparency and credibility (Lee & Rhee, 2023 [40]). Accordingly, ESG management enables hotel firms to signal moral commitment and managerial capability to consumers, which is associated with more favorable corporate image perceptions.

Guided by the above theoretical framework, this study developed the following hypotheses:

H1.

Hotels’ environmental (H1a), social (H1b), and governance (H1c) initiatives positively influence their corporate image.

2.3.2. Consumer Trust

Trust refers to a positive belief in the reliability, integrity, and dependability of an individual or organization (Everard et al., 2005 [49]). In the service context, consumer trust toward service providers reduces perceived risk and uncertainty, thereby fostering long-term relationships (Gefen, 2000 [50]). Within the hotel booking process, trust plays a critical role, as consumers often display cautious behavior; a lack of trust can become a major barrier to reservation decisions (Ladhari & Michaud, 2015 [51]). In the online booking environment, consumers’ trust in both third-party platforms and hotels themselves has been found to significantly enhance booking intentions (Kim et al., 2017 [52]). Consequently, cultivating consumer trust serves as an effective marketing strategy for hotels to strengthen customer engagement and encourage booking behaviors (Kim et al., 2009 [53]).

Empirical evidence suggests that corporate ESG activities can substantially strengthen consumers’ trust in firms (Bae et al., 2023 [54]; Koh et al., 2022 [42]). Bae et al. (2023 [54]) emphasize that firms’ investments in environmental protection, social responsibility, and governance practices convey signals of moral responsibility and reliable managerial capability to consumers, thereby enhancing trust evaluations. In the hospitality context, proactive environmental initiatives, social contributions, and sound and transparent governance practices help reduce consumers’ perceived uncertainty regarding service outcomes and strengthen their trust in hotels. Furthermore, prior studies indicate that corporate image also acts as a crucial antecedent to trust. When consumers perceive a hotel as having a strong and reputable image, they are more likely to view it as trustworthy and reliable (Lien et al., 2015 [55]). Accordingly, ESG practices may not only be directly associated with consumer trust but may also foster trust indirectly by enhancing corporate image as a key cognitive evaluation.

Guided by the above theoretical framework, this study developed the following hypotheses:

H2.

Hotels’ environmental (H2a), social (H2b), and governance (H2c) initiatives positively influence consumer trust.

H3.

A favorable corporate image enhances consumer trust.

2.4. Consumer Booking Intention

As noted by Dodds et al. (1991 [56]), purchase intention represents the degree to which an individual is inclined to buy a particular product or service. In the hospitality context, booking intention reflects the consumers’ propensity or willingness to reserve a hotel room (Lien et al., 2015 [55]). Within the framework of corporate ESG activities, consumers’ booking intention captures the extent to which sustainability considerations are incorporated into their accommodation decisions, thereby supporting environmentally responsible hospitality practices (Fang et al., 2025 [13]).

Building on this perspective, prior research has shown that a favorable corporate image is associated with both consumer trust and subsequent purchase behaviors (Górska-Warsewicz & Kulykovets, 2020 [57]). Trust, in turn, serves as a critical psychological help to reduce consumers’ perceived risk and uncertainty in the decision-making process, which in turn facilitates their willingness to engage in transactions (Kim et al., 2017 [52]; Ling et al., 2023 [58]). In the hotel booking setting, higher levels of trust in a hotel are therefore associated with a greater likelihood of making a reservation (Kim et al., 2017 [52]).

Guided by the above theoretical framework, this study developed the following hypotheses:

H4.

A positive corporate image strengthens consumers’ booking intentions.

H5.

Higher levels of consumer trust lead to stronger booking intentions.

2.5. The Moderating Role of Environmental Awareness

Environmental awareness is defined as individuals’ recognition of ecological problems, their support for remedial efforts, and their readiness to engage in behaviors that help mitigate environmental harm (Dunlap & Jones, 2002 [20]). As a form of self-cognition, environmental awareness influences how individuals attend to and interpret firms’ environmental practices, thereby shaping their consumption-related evaluations and decisions (Guo et al., 2019 [23]).

Previous research suggests that consumers exhibiting higher environmental awareness demonstrate stronger tendencies toward resource-efficient and eco-friendly consumption than those with lower environmental awareness (Jeong & Jang, 2011 [22]) and are more willing to engage in actual pro-environmental behaviors (Laroche et al., 2002 [21]). In corporate responsibility contexts, higher environmental awareness leads consumers to pay greater attention to firms’ environmental and sustainability-related signals, thereby strengthening trust in environmentally responsible firms and support for such firms (Ahmadet al., 2022 [59]). Beyond shaping general consumption tendencies, environmental awareness also functions as an important boundary condition, moderating the effects of firms’ sustainability practices on consumers’ cognitive evaluations. Empirical evidence indicates that environmental awareness significantly moderates the relationship between corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities and corporate image (Sharabati et al., 2023 [60]).

Drawing from the existing literature, this research proposes that environmental awareness moderates the relationships between hotels’ ESG activities and consumer responses. Specifically, the positive effects of hotels’ ESG activities on corporate image, consumer trust, and booking intentions are stronger among consumers with higher environmental awareness and weaker among those with lower environmental awareness.

H6.

Consumers’ environmental awareness positively moderates the relationships between hotels’ ESG initiatives and corporate image, such that the positive effects of environmental (H6a), social (H6b), and governance (H6c) initiatives on corporate image become stronger when consumers exhibit higher environmental awareness.

H7.

Consumers’ environmental awareness positively moderates the relationships between hotels’ ESG initiatives and consumer trust, strengthening the impacts of environmental (H7a), social (H7b), and governance (H7c) initiatives on consumer trust.

Figure 1 illustrates the proposed research framework and the hypothesized relationships among the constructs.

Figure 1.

Research framework.

3. Research Method

3.1. Measurement Items

To ensure the reliability and validity of measurement, all constructs were assessed using well-established scales adapted from the prior literature and measured from the perspective of consumers’ perceptions. The items representing the environmental (E), social (S), and governance (G) dimensions were adapted from Lee & Rhee (2023) [40], Bae et al. (2023) [54], and Koh et al. (2022) [42], respectively, capturing consumers’ subjective evaluations of hotels’ ESG practices based on information accessible to them. It is important to clarify that the governance dimension in this study does not refer to hotels’ objective governance structures. Rather, it reflects consumers’ perceived governance-related signals, such as transparency, ethical standards, and responsibility management. Corporate image was measured through four indicators modified from Lien et al. (2015) [55] and Ryu et al. (2019) [47], whereas consumer trust was assessed using four measures drawn from Ladhari & Michaud (2015) [51] and Górska-Warsewicz & Kulykovets (2020) [57]. Booking intention was operationalized using four statements derived from Lien et al. (2015 [55]), Kim et al. (2017) [52], and Ling et al. (2023) [58]. Environmental awareness was gauged using five items adapted from Dunlap & Jones (2002) [20] and Laroche et al. (2002) [21], and Sharabati et al. (2023) [60]. All measurement items were rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Demographic variables, including gender, age, education level, occupation, and income, were included as control variables in the analysis. The full list of measurement items is provided in Appendix A.

As the data collection took place in China, a back-translation approach following the guidelines of Lin et al. (2019) [61] was employed to guarantee semantic and conceptual equivalence between the English and Chinese questionnaires. To enhance contextual validity, a screening question was included at the beginning of the survey, and only respondents with actual stay experience at hotels under the Huazhu Group were retained for the final analysis. This procedure helped reduce potential confounding effects arising from differences in prior hotel experience. This study adopted a single-brand sample design focusing on hotels affiliated with the Huazhu Group. The Huazhu Group was selected because of its substantial market presence in the Chinese hotel industry, broad consumer coverage, and relatively high visibility of ESG-related practices. Employing a single-brand design allowed the study to control for brand heterogeneity across hotel chains, thereby enhancing internal validity and improving the interpretability of consumer-level ESG perceptions within the Chinese hospitality context.

3.2. Sample and Data Collection

To empirically test the proposed research framework, data were collected through an online survey administered via Wenjuanxing (https://www.wjx.cn/), a widely recognized Chinese platform. This platform has been widely adopted by scholars in information systems, marketing, and consumer behavior to collect data from Chinese online consumers. Wenjuanxing allows researchers to recruit participants with specific characteristics using preset screening criteria and to ensure data reliability through technical controls. In this study, the survey link was randomly distributed by the Wenjuanxing system to respondents who met the preset screening requirements. To ensure that participants possessed sufficient contextual awareness and relevant consumption experience, three screening questions were included at the beginning of the questionnaire. Specifically, respondents were required to (1) demonstrate basic familiarity with the concept of ESG-rated hotels, (2) identify and evaluate the relative importance of ESG dimensions (environmental, social, or governance) in hotel operations, and (3) confirm that they had stayed at an ESG-rated hotel under the Huazhu Group within the past three months. Questionnaires that failed to meet any of these screening criteria were excluded from the final sample. In addition, Wenjuanxing’s technical settings were applied to prevent duplicate submissions from the same IP address, thereby further enhancing response validity.

Data collection was conducted over a three-week period from 1 September to 21 September 2025. A pre-screened online sampling approach was employed, whereby only respondents who met the predefined screening criteria were allowed to proceed to the main questionnaire. Potential respondents who failed to meet any screening requirement were automatically terminated by the Wenjuanxing system before entering the formal survey. In total, 540 questionnaires successfully passed the screening stage and were completed. During subsequent data cleaning, responses exhibiting excessively uniform answering patterns, incomplete responses, failure to pass attention-check items, or abnormally short completion times were excluded. As a result, 518 valid questionnaires were retained for further analysis. Following the approach proposed by Armstrong & Overton (1977) [62], nonresponse bias was assessed by comparing the mean scores of major constructs between early and late respondents. The analysis revealed no statistically significant differences, implying that nonresponse bias did not materially affect the study outcomes. Details of the respondents’ demographic characteristics are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of participants (N = 518).

3.3. Data Analysis

This study adopted a dual analytical strategy combining Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) and fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) to examine the proposed framework. As outlined by Hair et al. (2011) [63], structural equation modeling can generally be approached through either the variance-based PLS technique or the covariance-based SEM method. The choice between them depends largely on the research objective. CB-SEM is typically used to confirm established theories and assess model fit, whereas PLS-SEM is more prediction-oriented and suitable for exploratory as well as confirmatory purposes (Hair et al., 2017 [64]). Given the study’s focus on consumers’ perceptions of hotel ESG practices and their associations with corporate image, consumer trust, and booking intention, PLS-SEM was employed to estimate structural relationships and assess predictive capability in a model involving multiple latent constructs. To further capture configurational perspective, fsQCA was applied to identify multiple configurations of ESG dimensions and cognitive variables associated with high booking intention.

To complement the variable-oriented results derived from PLS-SEM, fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) was further employed to identify multiple configurations of conditions associated with high booking intention. Unlike PLS-SEM, which focuses on the net effects of individual variables under an assumption of symmetry, fsQCA adopts a configurational perspective that examines how different combinations of conditions are associated with a focal outcome (Woodside, 2019 [65]; Ma et al., 2025 [66]). Based on fuzzy-set logic, fsQCA enables the identification of distinct configurational pathways in which the presence or absence of specific conditions is linked to the outcome to occur (Pappas & Woodside, 2021 [67]). Recent studies have increasingly advocated the combined use of PLS-SEM and fsQCA to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of complex consumer phenomena from complementary analytical perspectives (Rasoolimanesh et al., 2021 [68]). Following this approach, the present study integrated PLS-SEM and fsQCA to provide a more nuanced examination of the relationships between hotel ESG practices and consumers’ booking intentions.

3.4. Common Method Bias

Since the dataset was obtained through a self-reported cross-sectional survey, common method bias (CMB) was examined to ensure the robustness of the empirical outcomes. Consistent with Hair et al. (2017) [64] and Kock (2015) [69], two complementary procedures were applied. First, an exploratory factor analysis using Harman’s single-factor technique (Mackenzie et al., 2005 [70]) extracted six factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0, with the first accounting for 28.36% of total variance, well below the 50% cutoff, indicating limited CMB influence. Second, the marker-variable strategy (Lindell & Whitney, 2001 [71]) was performed by adding gender, the variable least correlated with other constructs, into the structural model. The significance and direction of all hypothesized paths remained unchanged. Together, these results suggest that the estimates from PLS-SEM are unlikely to be affected by common method variance.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Assessment

The reliability and validity of the measurement model were assessed through three aspects: internal consistency, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. Internal consistency was examined using Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE). As indicated in Table 2, all constructs yielded alpha and CR values exceeding 0.70 and AVE values greater than 0.50, demonstrating satisfactory reliability (Bagozzi, 1981 [72]). Convergent validity was supported by the standardized factor loadings of individual indicators on their corresponding constructs (Dijkstra & Henseler, 2015 [73]), which ranged from 0.767 to 0.879, well above the 0.70 cutoff. Discriminant validity was further established by comparing the square roots of AVE with inter-construct correlations (Bagozzi, 1981 [72]). As summarized in Table 3, the square roots of AVE for each construct exceeded the respective correlation coefficients, thereby meeting the criterion. Additionally, the heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT; Dijkstra & Henseler, 2015 [73]) was used for verification, and all values were below 0.85 (see Table 4), reinforcing discriminant validity.

Table 2.

Measurement model evaluation results.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity (Fornell–Larcker criterion).

Table 4.

Heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT).

Since ESG activities were conceptualized as a second order formative construct composed of three dimensions, namely environmental (E), social (S), and governance (G), the two step evaluation procedure recommended by Hair et al. (2012) [74] was applied to assess its reliability and validity. First, discriminant validity was examined by assessing the correlations among the first order dimensions. As reported in Table 3 and Table 4, the correlations among the ESG dimensions were relatively low, indicating that each dimension is conceptually distinct and supports the formative nature of the construct. Second, to assess potential multicollinearity among the formative dimensions, variance inflation factor (VIF) values were calculated. The results show that all VIF values were well below the recommended threshold of 10 (Christophersen and Konradt, 2012 [75]), with values of 1.064 for environmental (E), 1.201 for social (S), 1.201 for governance (G), 1.445 for corporate image, 1.330 for consumer trust, 1.330 for booking intentions, and 1.111 for environmental awareness. These results indicate that multicollinearity is not a concern. Taken together, the findings provide robust empirical support for the second order formative measurement model of ESG activities.

4.2. Structural Model Assessment

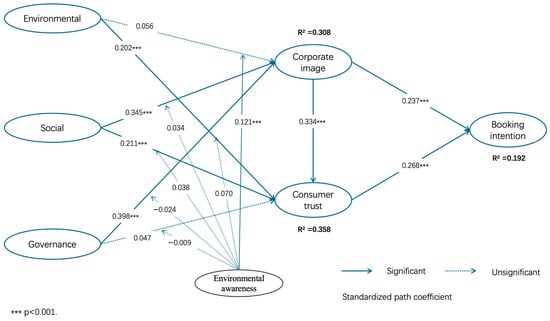

Following the confirmation of the measurement model, the structural relationships were analyzed. To test the significance of the hypothesized paths, a bootstrapping procedure with 5000 subsamples was employed. The corresponding results are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Result of structural model analysis.

As presented in Figure 2, the social (S) dimension (β = 0.345, p < 0.001) and governance (G) dimension (β = 0.398, p < 0.001) exerted significant positive impacts on corporate image, validating H1b and H1c. Conversely, the environmental (E) dimension (β = 0.056, p = 0.105) did not show a meaningful effect, and thus H1a was not supported.

With respect to consumer trust, both environmental (β = 0.202, p < 0.001) and social (β = 0.211, p < 0.001) dimensions displayed positive and significant associations, supporting H2a and H2b. However, the governance dimension (β = 0.047, p = 0.283) did not exhibit a significant relationship, leading to the rejection of H2c.

Moreover, corporate image positively affected consumer trust (β = 0.334, p < 0.001), lending support to H3. Both corporate image (β = 0.237, p < 0.001) and consumer trust (β = 0.268, p < 0.001) were positively linked to booking intention, validating H4 and H5.

Additionally, environmental concern strengthened the relationship between the environmental dimension and corporate image (β = 0.121, p < 0.001). Nevertheless, no significant moderating effects were found for environmental concern in the associations between the social and governance dimensions and corporate image (β = 0.034, β = −0.024, n.s.). Finally, environmental concern failed to moderate the links between the E, S, and G dimensions and consumer trust (β = 0.070, β = 0.038, β = −0.009, all n.s.).

The predictive performance of the structural model was assessed through hypothesis testing. Consistent with Falk and Miller (1992) [76], the explanatory capacity of the endogenous constructs was evaluated using path coefficients and the coefficient of determination (R2). An R2 value exceeding 0.10 is generally considered indicative of adequate explanatory power in SEM analyses. In the present study, the R2 values for corporate image (0.308), consumer trust (0.358), and booking intention (0.192) all surpassed this benchmark, suggesting satisfactory explanatory strength. The model’s overall fit was examined using the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), where 0.08 is typically regarded as the upper acceptable limit for PLS-based models (Dijkstra & Henseler, 2015 [73]). The obtained SRMR of 0.044 demonstrated an excellent model fit. Furthermore, Stone–Geisser’s Q2 values for corporate image (0.284), consumer trust (0.245), and booking intention (0.120) were all positive, confirming the predictive relevance of the model (Hair et al., 2017 [64]). A summary of these results is provided in Table 5.

Table 5.

Structural model results.

4.3. Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis

To complement the PLS-SEM results, fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) was conducted to uncover alternative causal pathways that explain high levels of booking intention. While the PLS-SEM findings provide empirical evidence of the linear relationships among constructs and clarify how hotel ESG activities influence consumer booking intentions, consumer decision-making in the hospitality context is inherently multifaceted. Prior research suggests that no single factor can fully determine booking behavior (Casado-Díaz et al., 2020 [6]). Therefore, drawing on the PLS-SEM results, this study adopted fsQCA to investigate the configurational pathways that stimulate high booking intentions and identify multiple, equally effective combinations of antecedents.

4.3.1. Data Calibration

Before conducting the fsQCA, data calibration was carried out as a necessary preparatory step (Ragin, 2008 [77]). This procedure converted each raw variable into a fuzzy membership score between 0 (complete non-membership) and 1 (complete membership), with 0.5 indicating the crossover point of maximum ambiguity (Rihoux, 2006 [78]). The calibration process was implemented using fsQCA 4.0 software. In line with Gligor & Bozkurt (2020) [79], a percentile-based calibration scheme was applied, setting the 75th percentile as the full membership cutoff, the 50th percentile as the crossover, and the 25th percentile as the full non-membership threshold. This approach ensures a data-driven transformation that captures the empirical distributional properties of the sample.

4.3.2. Analysis of Necessary Conditions

After transforming all variables into fuzzy sets, a necessity test was initially performed to evaluate whether any of the six antecedent conditions, environmental (ENV), social (SOC), governance (GOV), corporate image (CI), consumer trust (CT), and environmental awareness (EAW), could be considered indispensable for achieving high consumer booking intention (CBI). Both the presence and negation of each antecedent were examined. Consistency scores, ranging from 0 to 1, reflect the extent to which cases with high CBI also display the corresponding condition (Rihoux, 2006 [78]). According to Ragin (2008) [77], a consistency level above 0.90 is generally recognized as the threshold for necessity. As shown in Table 6, the consistency values of all antecedents ranged between 0.352 and 0.707, below this benchmark, indicating that none of the single factors independently guarantee high booking intention. Consequently, a subsequent configurational analysis was undertaken to identify how combinations of these conditions jointly lead to high CBI outcomes.

Table 6.

Examination of necessary conditions for predicting CBI.

4.3.3. Analysis of Sufficient Conditions

In line with Ragin (2008) [77], the sufficiency analysis began with the development of a truth table in fsQCA 4.0. The table contained 2^k possible configurations, where k represents the number of antecedent conditions, and each row denotes a distinct combination of their presence or absence. Following Fiss (2011) [80], rows not satisfying the minimum frequency criterion were omitted; specifically, for datasets with more than 150 cases, configurations represented by fewer than three observations were excluded. A raw consistency threshold of 0.75, as suggested by Rihoux (2006) [78], was then applied, and only configurations surpassing this benchmark were retained for subsequent interpretation. The fsQCA generated three solution types, complex, parsimonious, and intermediate. The present study focused on the intermediate solution, as it strikes a balance between empirical precision and theoretical interpretability (Ragin, 2008 [77]). The configurational results are summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Main configurations for high CBI.

As shown in Table 7, the fsQCA results identified six distinct configurations, labeled S1 to S6, that are associated with high consumer booking intention (CBI). The overall solution coverage was 0.389 and the solution consistency was 0.842, both of which meet the commonly recommended thresholds in fsQCA research (Ragin, 2008 [77]). These values indicate that the identified configurations account for a meaningful proportion of high booking intention cases while not exhausting all possible pathways, thereby reflecting the diversity and complexity of consumers’ decision processes.

Configuration S1 shows that when environmental (ENV), social (SOC), and governance (GOV) activities are all present as core conditions and consumer trust (CT) is high, high booking intention can be observed even in the absence of environmental awareness (EAW), with a consistency of 0.878 and a raw coverage of 0.116. This configuration reflects an ESG and trust oriented pathway, suggesting that when overall ESG performance is balanced and trust is well established, individual differences in environmental awareness are not necessarily a binding constraint.

Configuration S2 indicates that strong environmental (ENV) and social (SOC) performance as core conditions, together with the presence of consumer trust (CT) and environmental awareness (EAW), can compensate for weaker governance (GOV), with a consistency of 0.853 and a raw coverage of 0.153. This finding illustrates functional substitutability among ESG dimensions, implying that when consumers exhibit strong value orientation and trust, shortcomings in governance do not inevitably impede booking decisions.

Configuration S3 demonstrated high consistency at 0.920 but relatively limited coverage at 0.059. This pathway suggests that even when consumers display low environmental awareness, the presence of a favorable corporate image (CI) and strong consumer trust (CT) as core conditions may still be associated with high booking intention. This pattern points to a reputational buffering mechanism, whereby positive corporate image and trust can attenuate consumers’ sensitivity to specific ESG dimensions.

Configuration S4 exhibited the highest consistency at 0.939, although its coverage was relatively small at 0.051. The results indicate that when governance (GOV) and environmental awareness (EAW) are present as core conditions, high booking intention may still occur despite weaker social performance (SOC) and lower consumer trust (CT), provided that corporate image (CI) remains positive. This configuration reflects a governance and value alignment pathway, highlighting the role of institutional signals and value congruence in specific contexts.

Configurations S5 and S6 both showed high consistency at 0.844, with S6 exhibiting the highest raw coverage at 0.277. Taken together, these two pathways indicate that when consumer trust (CT) serves as a core condition, strengthened environmental (ENV) and social (SOC) performance is more likely to be associated with high booking intention, particularly in contexts where environmental awareness (EAW) is high. This pattern reflects a value and trust synergy pathway, in which corporate ESG activities resonate with consumers’ personal values, leading to stronger booking responses.

Overall, the fsQCA results complement the linear analysis obtained from PLS-SEM by revealing multiple, distinct yet equivalent configurational pathways associated with high booking intention. These findings underscore that high CBI does not arise from a single factor or a single pathway, but rather from different combinations of ESG activities, corporate image, consumer trust, and individual value orientations across varying contexts.

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Discussion

Grounded in the Stimulus–Organism–Response (S–O–R) framework, this study examined how hotel firms’ environmental, social, and governance (ESG) practices are associated with consumers’ booking intentions through the interconnected mediating roles of corporate image and consumer trust. To capture both symmetric and asymmetric relationships among the study variables, a dual-method analytical approach was adopted. Specifically, partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was first employed to assess the average net effects and symmetric associations, while fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) was subsequently introduced as a complementary approach to explore how different configurations of antecedent conditions jointly relate to high booking intention under conditions of causal asymmetry. Importantly, fsQCA is not intended to validate the PLS-SEM results, but rather to uncover configurational pathways and causal complexity that cannot be fully captured by variance-based techniques.

First, the PLS-SEM results show that the social (S) and governance (G) dimensions of hotel ESG initiatives have significant positive effects on corporate image (H1b, H1c). Consistent with recent hospitality research, social responsibility investments and governance transparency are more readily recognized by consumers and interpreted as signals of firms’ values and managerial competence, thereby exerting a stronger influence on corporate image than environmental practices (Lee & Rhee, 2023 [40]; Wan, 2023 [81]; Kim & Cho, 2024 [82]). In contrast, environmental (E) initiatives do not significantly enhance corporate image (H1a). Although positive image effects of environmental ESG practices have been documented in highly perceptible service contexts such as airlines (Kim & Cho, 2024 [82]), environmental initiatives in hotels are often embedded in backstage operations, limiting their salience in consumers’ core service encounters and rendering their image effects more context dependent. Furthermore, environmental (E) and social (S) activities are positively associated with consumer trust (H2a, H2b), as sustained commitments in these domains signal benevolence and reliability (Bae et al., 2023 [54]; Lee, 2025 [83]). In contrast, governance (G) initiatives do not exhibit a significant direct effect on consumer trust (H2c), likely because governance practices are primarily communicated through institutional or firm-level disclosures and are less directly observable during routine service interactions.

Secondly, the PLS-SEM results indicate that corporate image has a significant positive effect on consumer trust (H3), consistent with prior research suggesting that favorable corporate perceptions enhance consumers’ confidence in a firm’s integrity and competence (Lien et al., 2015 [55]). In the context of hotel ESG practices, this finding suggests that when consumers hold more positive overall evaluations, they are more likely to develop trust judgments based on service encounters and informational cues. In addition, both corporate image and consumer trust are positively associated with consumers’ booking intentions (H4 and H5). This result indicates that within the hotel ESG context, reputational capital and consumer trust function as important psychological mechanisms through which consumers’ positive evaluations may be translated into booking intentions (Górska-Warsewicz & Kulykovets, 2020 [57]; Ling et al., 2023 [58]).

Third, this study further examined the mediating roles of corporate image and consumer trust in the relationship between hotel ESG activities and booking intention. The results suggest that different ESG dimensions are associated with consumer decision-making through differentiated psychological pathways: social (S) and governance (G) practices are more conducive to shaping corporate image, whereas environmental (E) and social (S) efforts are more closely related to consumer trust. This pattern is consistent with prior research indicating that corporate image and consumer trust respectively reflect consumers’ overall evaluations of firms and their reliability-based judgments and thus operate through distinct mediating pathways in ESG-related contexts (Lee & Rhee, 2023 [40]; Kim & Cho, 2024 [82]; Lee, 2025 [83]; Li & Chen, 2025 [84]). In addition, this study examined the moderating role of environmental awareness in the relationships between ESG dimensions and the mediators. The findings show that environmental awareness strengthens the association between environmental (E) activities and corporate image (supporting H6a), while no significant moderating effects were observed for the other ESG–image and ESG–trust relationships. Taken together, these findings indicate that the influence of environmental awareness is clearly dimension-specific, in that it primarily strengthens consumers’ responses to environmental cues while not necessarily exerting an equivalent effect on the evaluation of social or governance-related information, which is consistent with recent evidence on consumers’ selective processing of ESG signals (Abdul Rahim et al., 2025 [85]).

Finally, the fsQCA results identified six sufficient configurational pathways associated with high booking intention, offering additional insights into the causal complexity underlying the relationships between hotel ESG practices and consumers’ psychological responses. The findings indicate that high booking intention does not depend on a single ESG dimension or a uniform psychological mechanism but can emerge through multiple combinations of antecedent conditions. Specifically, configurations S1 and S2 suggest that when environmental (E) and social (S) practices are strong and consumer trust is high, elevated booking intention may still occur even in the absence of salient governance (G) initiatives or high environmental awareness. From a configurational perspective, these pathways illustrate the potentially important role of consumer trust across different ESG combinations, rather than implying a necessary or universal effect. In addition, configurations S3 and S5 indicate that a favorable corporate image may function jointly with other psychological factors as part of alternative pathways to high booking intention. Even when certain ESG cues or environmental awareness are relatively weak, higher booking intention may still be observed when consumers maintain a positive overall evaluation of the hotel and a sufficient level of trust. These results suggest that corporate image tends to operate in conjunction with other conditions within specific configurations, rather than acting as an isolated driver of booking intentions. Configurations S4 and S6 further highlight the importance of alignment between hotel ESG practices and consumers’ value orientations. When governance transparency and environmental-related practices co-occur within specific configurations, high booking intention may be associated with these combinations even if other ESG dimensions or consumer trust is less pronounced. This pattern implies that value congruence may act as an amplifying or triggering condition under certain circumstances. Taken together, the fsQCA findings demonstrate that diverse combinations of ESG practices and consumer psychological responses can lead to similar behavioral outcomes, reflecting causal diversity, asymmetry, and equifinality in hotel booking decisions. Importantly, these configurational results are not intended to validate the linear relationships identified in the PLS-SEM analysis, but rather to provide a complementary perspective that helps illuminate the multiple pathways through which sustainability-oriented hotel practices may be associated with consumers’ booking intentions.

It is also necessary to further clarify the explanatory power of the structural model. Although the R2 values of the key endogenous constructs in this study were at a moderate level, such magnitudes are both reasonable and consistent with expectations in hospitality and tourism research that focuses on consumer perceptions and psychological mechanisms. Consumers’ booking intentions are influenced by a wide range of factors, including price, location, prior experience, and individual preferences, many of which fall outside the scope of the present study. Rather than attempting to exhaustively account for all determinants of booking behavior, this research concentrated on ESG-related psychological pathways. From this perspective, the observed R2 values reflect the model’s effectiveness in explaining specific perceptual and cognitive mechanisms, rather than its ability to fully predict consumer intentions.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

Building on existing research on hotel ESG practices and consumer behavior, this study provides several incremental theoretical insights. By introducing a consumer-psychological perspective, it offers a more detailed depiction of how hotel ESG initiatives are associated with consumers’ booking intentions, thereby complementing prior studies in this area. The existing literature has largely focused on the macro-economic outcomes of ESG in the hospitality industry, such as firm performance and investment returns (Ding & Tseng, 2023 [14]; Chung et al., 2024 [16]) or has emphasized consumers’ overall and functional evaluations of corporate social responsibility (Lee & Rhee, 2023 [40]). In contrast, relatively limited attention has been paid to how consumers form behavioral intentions through specific psychological mechanisms in sustainability-related contexts. Against this backdrop, the present study applied the Stimulus–Organism–Response (S-O-R) framework to the context of hotel ESG management and further distinguished corporate image and consumer trust as two key psychological responses. The results indicate that different ESG dimensions, as external stimuli, are not associated with booking intentions through a single psychological pathway, but rather through differentiated mediating mechanisms. Accordingly, without altering the core logic of S–O–R theory, this study provides a more refined, mechanism-level understanding of how ESG practices are linked to consumers’ booking intentions in the hotel context.

Second, this study refines the distinct psychological roles of corporate image and consumer trust in linking hotel ESG initiatives to booking intentions. Although prior research has examined these constructs in the contexts of ESG performance management, investment decision-making, and sustainable consumption (Lew et al., 2024 [48]; Chung et al., 2024 [16]; Lee & Rhee, 2023 [40]), their differentiated behavioral effects have been less clearly articulated in the hotel sustainability context. The findings show that different ESG dimensions are associated with booking intentions through distinct psychological pathways: social and governance practices are more closely related to corporate image evaluations, whereas environmental and social practices are more strongly associated with consumer trust. In addition, environmental awareness exhibits a significant moderating effect only on the relationship between environmental practices and corporate image, suggesting that consumers selectively process ESG information in line with their value orientations. Together, these results provide a more fine-grained understanding of consumer psychological mechanisms in sustainable hotel marketing.

Finally, adopting a configurational perspective, this study offers incremental theoretical insights into how hotel ESG activities are associated with consumers’ booking intentions. By combining PLS-SEM and fsQCA as complementary analytical approaches, the study not only identifies the average net effects of ESG dimensions on consumer intentions, but also illustrates how different combinations of antecedent conditions may be linked to similar behavioral outcomes. Specifically, the fsQCA results suggest that high booking intention does not rely on a single ESG dimension or an isolated psychological mechanism but may emerge through diverse configurations of ESG practices, corporate image, consumer trust, and environmental awareness. This integrative methodological approach provides a complementary lens for understanding causal complexity and asymmetry in ESG-related influence mechanisms, thereby addressing multi-path patterns that may be overlooked when relying solely on linear models.

5.3. Managerial Implications

First, the findings highlight the pivotal roles of corporate image and consumer trust in converting hotel ESG efforts into consumers’ booking intentions. Rather than treating ESG disclosure merely as a compliance requirement, hotel managers should strategically design initiatives that consumers can clearly perceive, evaluate, and attribute to the brand. To achieve this, hotels may prioritize social initiatives and transparent governance practices that enhance corporate reputation while simultaneously investing in visible and credible environmental actions that directly foster consumer trust. By doing so, ESG signals are more likely to be internalized by consumers and translated into favorable booking decisions.

Second, hotel companies should formulate targeted sustainability-related marketing communication strategies that reflect the differentiated effects of ESG dimensions. Social and governance initiatives serve more effectively in shaping a positive corporate image, whereas environmental and social efforts better enhance consumer trust (Lee & Rhee, 2023 [40]). Thus, instead of adopting a uniform disclosure approach, hotels should tailor their ESG-related communication focus to the psychological outcomes each dimension evokes. Social contributions and governance transparency should mainly support brand image building, while environmental initiatives should be communicated in more direct and credible ways, such as through concrete, observable, and verifiable information (e.g., visible practices, third-party certifications, or experience-linked cues), to reinforce trust. Moreover, given that consumers with higher environmental awareness are more sensitive to environmental cues, hotels may selectively emphasize environmental information to this segment to improve communication efficiency and encourage booking intentions.

Finally, hotel companies should prioritize ESG practice portfolios that align with their existing resources. The configurational findings of this study hold strong managerial relevance, revealing that multiple pathways can effectively enhance booking intentions. From a resource allocation perspective, managers do not need to make high-level investments across all ESG dimensions simultaneously; rather, different combinations of initiatives can achieve the same market goal, higher booking conversion. Specifically, the six effective configurations identified in this study provide hotels with strategic options to tailor ESG practices according to resource conditions and target customer segments. For markets with high environmental awareness, allocating resources toward environmental and social actions while reinforcing corporate image and trust (e.g., Configuration S6) may be more cost-efficient. Conversely, for markets with lower sustainability concern, focusing on strengthening overall ESG credibility and consumer trust alone (e.g., Configuration S5) can still generate desirable conversion outcomes. Thus, hotels should align ESG strategies with both resource capabilities and segment characteristics to improve conversion efficiency and build sustainable competitive advantage.

6. Limitations and Future Research

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations that suggest directions for future research. First, the analysis was based on a single hotel brand and a single-country sample of Chinese consumers. Although this design helps control for brand heterogeneity and enhances internal consistency, it may limit the generalizability of the findings across different brand contexts and cultural settings. In addition, due to the online survey method and the use of screening questions at the beginning to ensure recent stays at an ESG-rated Huazhu hotel, older consumers aged 50 and above may be underrepresented in the final sample. Future research could adopt multi-brand and cross-cultural comparative designs to further examine the robustness of the results. Second, this study relied on booking intention rather than actual booking behavior, which raises concerns related to the attitude–behavior gap. Future studies may integrate transaction data, field experiments, or longitudinal approaches to assess whether and how hotel ESG practices translate into real consumption behaviors. Third, the cross-sectional nature of the data constrains the examination of dynamic causal relationships among ESG practices, consumer psychological responses, and booking intentions. Longitudinal or experimental designs could provide deeper insights into the temporal and causal processes underlying these relationships. Finally, while this study focused on corporate image and consumer trust as key psychological mechanisms, it did not capture all of the possible pathways through which different ESG dimensions may influence booking decisions. In addition, some potentially relevant control variables, such as prior stay experience, brand familiarity, or perceived service quality, were not explicitly incorporated into the model, which may introduce a risk of omitted variable bias. Future research could incorporate additional constructs, such as brand attachment, brand credibility, or brand experience, to further enrich the understanding of ESG-driven consumer behavior.

Author Contributions

B.Z. conceptualized the idea, contributed to the study design, organized the data collection, ran the analyses, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. S.J. contributed to the research methodology, supervised this research and edited the original manuscript before submission. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study as it did not involve any personally identifiable information.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

| Variable | Measurement Item | Author | ||

| ESG Activities | Environmental (E) | ENV1 | Reduces carbon and greenhouse gas emissions. | Lee & Rhee (2023) [40]; Bae et al. (2023) [54]; Koh et al. (2022) [42] |

| ENV2 | Uses eco-friendly energy and materials. | |||

| ENV3 | Practices recycling and waste reduction. | |||

| ENV4 | Protects biodiversity and minimizes harmful chemicals. | |||

| Social (S) | SOC1 | Supports local community development. | ||

| SOC2 | Provides fair working conditions for employees. | |||

| SOC3 | Respects customer rights and privacy. | |||

| SOC4 | Promotes diversity and inclusion. | |||

| Governance (G) | GOV1 | Manages business ethically and transparently. | ||

| GOV2 | Complies with laws and regulations. | |||

| GOV3 | Discloses ESG information openly. | |||

| GOV4 | Has clear accountability in management. | |||

| Corporate Image (CI) | CI1 | Has a favorable image in the minds of customers. | Lien et al. (2015) [55]; Ryu et al. (2019) [47] | |

| CI2 | Is perceived as a reputable and trustworthy company. | |||

| CI3 | Is recognized as a socially responsible and reliable brand. | |||

| CI4 | Leaves a positive overall impression on customers. | |||

| Consumer Trust (CT) | CT1 | Believes that the company keeps its promises. | Ladhari & Michaud (2015) [51]; Górska-Warsewicz & Kulykovets (2020) [57] | |

| CT2 | Feels confident in the company’s reliability. | |||

| CT3 | Thinks the company acts in the best interest of its customers. | |||

| CT4 | Trusts the company to provide honest and transparent information. | |||

| Consumer Booking Intention (CBI) | CBI1 | Intends to book a stay at this hotel in the future. | Lien et al. (2015) [55]; Kim et al. (2017) [52]; Ling et al. (2023) [58] | |

| CBI2 | Is willing to choose this hotel over other alternatives. | |||

| CBI3 | Would recommend this hotel to others for booking. | |||

| CBI4 | Is likely to make an online reservation with this hotel soon. | |||

| Environmental Awareness (EAW) | EAW1 | I am concerned about environmental pollution. | Dunlap & Jones (2002) [20]; Laroche et al. (2002) [21]; Sharabati et al. (2023) [60] | |

| EAW2 | I believe that environmental pollution on Earth is a serious problem. | |||

| EAW3 | I think human activities are seriously destroying the environment. | |||

| EAW4 | I believe that when humans destroy nature, the consequences are often disastrous. | |||

| EAW5 | I think environmental pollution caused by single-use products is very serious. | |||

References

- Skogen, K.; Helland, H.; Kaltenborn, B. Concern about climate change, biodiversity loss, habitat degradation and landscape change: Embedded in different packages of environmental concern? J. Nat. Conserv. 2018, 44, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.; Jung, M. Effect of ESG activities and firm’s financial characteristics. Korean J. Financ. Stud. 2020, 49, 681–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, R.A.; Méxas, M.P.; Meirino, M.J.; Sampaio, M.C.; Costa, H.G. Criteria for assessing a sustainable hotel business. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 262, 121347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, S.; Bernard, S.; Singal, M. The impact of sustainability certifications on performance and competitive action in hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 108, 103379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.T.J.; Lee, J.S.; Sheu, C. Are lodging customers ready to go green? An examination of attitudes, demographics, and eco-friendly intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casado-Díaz, A.B.; Sellers-Rubio, R.; Rodriguez-Sanchez, C.; Sancho-Esper, F. Predictors of willingness to pay a price premium for hotels’ water-saving initiatives. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 773–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Jo, Y.; Lee, S.; Park, J.; Cho, J.; Kim, H. ESG for Sustainability in Hospitality and Tourism: A Theoretical and Practical Review with a Future Research Agenda. J. Travel Res. 2025, 65, 00472875251363629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.Y.; Fan, W.S.; Tsai, M.C. The Mediating Role of Employee Perceived Value in the ESG–Sustainability Link: Evidence from Taiwan’s Green Hotel Industry. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velaoras, K.; Menegaki, A.N.; Polyzos, S.; Gotzamani, K. The role of environmental certification in the hospitality industry: Assessing sustainability, consumer preferences, and the economic impact. Sustainability 2025, 17, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarimoglu, E.; Gunay, T. The extended theory of planned behavior in Turkish customers’ intentions to visit green hotels. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 1097–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.C.; Park, J. Threat-induced sustainability: How COVID-19 has affected sustainable behavioral intention and sustainable hotel brand choice. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2024, 48, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.; Chen, H.; Bernard, S. The incidence of environmental status signaling on three hospitality and tourism green products: A scenario-based quasi-experimental analysis. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2023, 46, 101076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Zaman, U. Sustainable consumer-brand relationship: The role of sustainable marketing in shaping room booking intentions in green hospitality services. Acta Psychol. 2025, 258, 105197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, X.; Tseng, C.J. Relationship between ESG strategies and financial performance of hotel industry in China: An empirical study. Nurture 2023, 17, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Chiriko, A.Y.; Kim, S.S.; Moon, H.G.; Choi, H.; Han, H. ESG management of hotel brands: A management strategy for benefits and performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 125, 103998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.; Nguyen, L.T.M.; Nguyen, D.T.T. Improving hotels’ operational efficiency through ESG investment: A risk management perspective. Serv. Sci. 2024, 16, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhou, H.; Liu, Y.; Lu, R. Optimal environmental quality and price with consumer environmental awareness and retailer’s fairness concerns in supply chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 213, 1063–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wang, W.; Tao, Y.; Shao, M.; Yu, C. Understand the Chinese Z generation consumers’ green hotel visit intention: An extended theory of planned behavior model. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugiarti, M.; Adawiyah, W.R.; Rahab, R. Green hotel visit intention and the role of ecological concern among young tourists in Indonesia: A planned behavior paradigm. Tour. Int. Interdiscip. J. 2022, 70, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.; Jones, R. Environmental Concern: Conceptual and Measurement Issues. In Handbook of Environmental Sociology; Dunlap, R., Michelson, W., Eds.; Greenwood Press: London, UK, 2002; pp. 482–542. [Google Scholar]

- Laroche, M.; Tomiuk, M.A.; Bergeron, J.; Barbaro-Forleo, G. Cultural differences in environmental knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours of Canadian consumers. Can. J. Adm. Sci./Rev. Can. Des Sci. L’Adm 2002, 19, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, E.; Jang, S.S. Restaurant experiences triggering positive electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) motivations. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Xu, Y.; Liu, G.; Wang, T.; Du, C. Understanding firm performance on green sustainable practices through managers’ ascribed responsibility and waste management: Green self-efficacy as moderator. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, J. Stimulus-organism-response reconsidered: An evolutionary step in modeling (consumer) behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2002, 12, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A.; Mehrabian, A. Distinguishing anger and anxiety in terms of emotional response factors. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1974, 42, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, R. Validation of an SOR model for situation, enduring, and response components of involvement. J. Mark. Res. 1982, 19, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandita, S.; Mishra, H.G.; Chib, S. Psychological impact of COVID-19 crises on students through the lens of Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) model. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 120, 105783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochreiter, V.; Benedetto, C.; Loesch, M. The stimulus-organism-response (SOR) paradigm as a guiding principle in environmental psychology: Comparison of its usage in consumer behavior and organizational culture and leadership theory. J. Entrep. Bus. Dev. 2022, 42, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asyraff, M.A.; Hanafiah, M.H.; Aminuddin, N.; Mahdzar, M. Adoption of the Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) model in hospitality and tourism research: Systematic literature review and future research directions. Asia-Pac. J. Innov. Hosp. Tour. 2023, 12, 19–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.J.; Lee, C.K.; Jung, T. Exploring consumer behavior in virtual reality tourism using an extended stimulus-organism-response model. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]