Abstract

Enhancing the social dimension of sustainability is essential for improving the livability of informal settlements, yet its evaluation is often constrained by the absence of reliable socio-economic data. This study addresses this challenge by demonstrating how a rigorous, form-based analysis can be utilized to interpret the social potential embedded within the physical structure of informal settlements. Focusing on the Saadi neighborhood in Shiraz, Iran, the research applies a validated four-part morphological framework—integrated with Space Syntax principles—to examine how specific spatial configurations create conditions supportive of social interaction and territorial security. Rather than attempting to measure social sustainability directly, the study conceptualizes physical morphology as a tangible proxy through which socially supportive spatial conditions can be inferred. The analysis reveals three critical morphological drivers: (1) a fine-grained urban fabric that directly enhances walkability and co-presence; (2) a low vertical profile that ensures visual permeability and informal surveillance; and (3) semi-private residential clusters that function as defensible space. These findings highlight how the physical form of informal settlements contains an underlying social logic that can be systematically decoded. The paper concludes that form-based analysis provides a replicable pathway for identifying the spatial scaffolding that supports community life, offering valuable insights for socially oriented upgrading strategies in data-scarce contexts.

1. Introduction

Rapid urbanization in the Global South has solidified informal settlements as a dominant mode of city-making, necessitating a paradigm shift in how these environments are understood and managed. In the wake of global crises—most notably the COVID-19 pandemic—the discourse on urban resilience has expanded beyond physical infrastructure toward a stronger emphasis on the social dimension of sustainability [1,2]. Social sustainability, defined by qualities such as social equity, community cohesion, safety, and interaction, is now recognized as a critical determinant of livability in high-density urban environments [3]. However, translating these concepts into practice remains challenging, particularly in developing regions. Wahab [4] argues that transforming informal settlements into liveable communities requires strategies that go beyond physical upgrading to address the socio-functional needs of residents.

Evaluating social sustainability in informal settlements remains methodologically fraught due to the chronic scarcity of reliable socio-economic data and the fluid nature of demographic structures. In the absence of conventional datasets, the built environment itself presents a stable and observable medium through which social dynamics can be interpreted. Contemporary urban theory posits that physical form is not a neutral container but an active agent that creates specific “spatial affordances” for social behavior [5]. This relationship is particularly evident in the Middle Eastern context; as Sharifi and Murayama [6] highlight in their study of Iranian cities, traditional and organic urban forms have historically played a pivotal role in sustaining social bonds, a quality often compromised in modern, planned developments.

The configuration of street networks, the permeability of boundaries, and the density of the fabric directly influence patterns of movement and co-presence, which are the fundamental prerequisites for social interaction [7]. Ali et al. [8] further emphasize this link, demonstrating that specific urban forms significantly impact social sustainability indicators such as social equity and safety. Consequently, urban morphology—the study of urban form—offers a powerful, yet underutilized, lens for diagnosing the social potential of informal settlements.

Despite the clear theoretical link between form and social life, empirical studies often bifurcate into sociological ethnographies or purely physical surveys. Recent scholarship in Space Syntax, rooted in the foundational work of Hillier regarding ‘deformed grids’ [9] and expanded by scholars in informal contexts [10], has begun to bridge this gap. Hillier [11] argues that the “organic” patterns found in such settlements are not accidental but represent “sustainable forms” generated by movement economies. These irregular grids often possess a high degree of internal integration, fostering strong local community bonds that top-down planning frequently fails to replicate [12,13]. However, there remains a lack of integrated frameworks that combine these configurational insights with a multi-scalar morphological analysis, particularly within the context of Iranian informal urbanism.

This study addresses this research gap by proposing a form-based analytical approach to evaluate the social sustainability of the Saadi neighborhood in Shiraz, Iran. It is hypothesized that the settlement’s physical morphology contains a latent social logic that can be systematically decoded. Building upon a validated morphological model [14], this research interrogates how specific physical attributes—from the macro-scale topographical enclosure to the meso-scale street network and micro-scale building interfaces—create spatial conditions conducive to social interaction and territorial security. By focusing on the observable physical form, the study aims to provide a replicable, evidence-based method for identifying the inherent social assets of informal settlements, thereby informing more context-sensitive and socially sustainable upgrading strategies [15].

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the relevant literature linking urban morphology, space syntax, and social sustainability; Section 3 outlines the methodological framework; Section 4 presents the empirical results of the Saadi case study; Section 5 discusses the findings in relation to the social potential of space; and Section 6 concludes with implications for urban design and policy.

2. Literature Review

This section synthesizes the theoretical intersections between informal urbanism, urban morphology, and social sustainability. It argues that the physical form of a settlement is not merely a container for social life but an active determinant of social sustainability, shaping patterns of interaction, territoriality, and community resilience.

2.1. Social Sustainability in the Context of Informal Settlements

While sustainable development has traditionally prioritized environmental and economic dimensions, recent urban scholarship has re-centered social sustainability as a critical pillar for the livability of high-density urban environments [16]. In the context of the built environment, social sustainability is defined by the capacity of urban form to foster social equity, community cohesion, sense of safety, and quality of life [3].

In informal settlements, where formal state support and public amenities are often absent, the social dimension of sustainability takes on an existential significance. The community relies on strong social networks for resilience, resource sharing, and security. However, assessing social sustainability in these contexts is challenging due to the lack of reliable socio-economic data. Consequently, recent studies suggest shifting the analytical focus from transient demographic metrics to the stable, observable attributes of the physical environment, positing that the built form itself creates the necessary “spatial affordances” for a socially sustainable community [5]. This aligns with Rapoport’s [17] foundational “man-environment” framework, which posits that physical elements act as non-verbal cues that can either inhibit or facilitate specific social behaviors.

2.2. Urban Morphology: The Physical Dimension of Social Potential

Urban morphology, the systematic study of the physical form of settlements, provides the primary lens for this assessment. Unlike formal cities planned from the top down, informal settlements are described in the recent literature as “self-organized” or “emergent” morphologies. Dovey [18] conceptualizes these settlements as “complex adaptive assemblages,” where the urban form evolves incrementally through the interactions of residents. These areas are characterized by incremental growth, irregular street networks, and a fine-grained mix of uses [19].

Crucially, this specific morphology is inextricably linked to social performance. The “fine grain” of the urban fabric—characterized by small plots and frequent entrances—has been shown to increase the permeability of the street interface, thereby enhancing social interaction and economic vitality [15]. Dovey and King [20] note that the morphology and visibility within these settlements play a crucial role in shaping the social interface between public and private realms. Thus, morphological analysis serves as a critical tool for decoding the “social logic” embedded in the physical layout, revealing how specific forms function as mechanisms for social cohesion rather than indicators of disorder [12].

While configurational approaches focus on connectivity, other morphological traditions, particularly the typo-morphological approach rooted in the work of Conzen and the Italian school, emphasize the persistence of building types and their adaptation over time. In informal settlements, this perspective is crucial for understanding how specific housing typologies—such as the courtyard house in the Middle East—evolve incrementally to accommodate changing social needs while maintaining cultural norms of privacy [21].

Furthermore, the structural indicators of informal morphology (location, fabric, typology, materiality) were established and validated in a preceding methodological study [14]. Building on those findings, the current research shifts the analytical focus from identification to interpretation, specifically examining how these established morphological patterns function socially to support community resilience.

However, applying these theories requires attention to context. As noted by Carrilho and Trindade [22], while some biophysical parameters of informality (such as density and accretion) are universal across the Global South, local cultural drivers—such as the specific requirements for gendered privacy in Iranian culture [23] or climate-responsive shading strategies—significantly shape how these forms are inhabited.

2.3. Space Syntax and Configurational Logic

To operationalize the link between form and social behavior, this study integrates principles from Space Syntax theory. This approach posits that the spatial configuration of the street network directly influences movement patterns and the probability of human encounter [24]. Karimi [25] emphasizes that configurational structures are the primary generators of “social spaces,” arguing that analytical, evidence-based design must account for these underlying network properties.

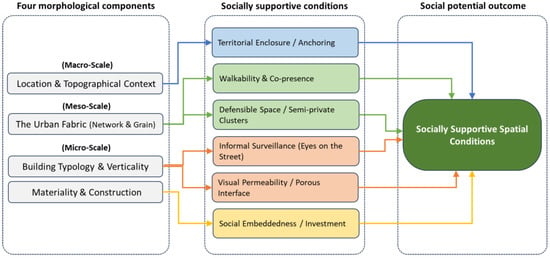

Recent empirical applications of Space Syntax in informal contexts have demonstrated that the “organic” grid often possesses high levels of local integration and connectivity, which facilitates “co-presence”—the fundamental prerequisite for social interaction [13]. Askarizad and Safari [7] argue that spatial configurations that promote visibility and accessibility significantly enhance behavioral patterns related to social interaction. In informal settlements, the hierarchy of the network—often transitioning from integrated commercial spines to segregated, semi-private residential clusters—creates a diverse range of social spaces [26]. Cutini et al. [27] further validate this approach, demonstrating through spatial analysis that informal settlements often exhibit a high degree of spatial logic that supports their socio-functional resilience. Therefore, analyzing the configurational properties of the network provides quantitative evidence regarding the settlement’s capacity to support a vibrant and safe social life (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework illustrating the link between urban morphology and socially supportive conditions. The diagram demonstrates how specific morphological components (left) translate into social affordances (center): (1) Location & Topographical Context establishes territorial enclosure and anchoring; (2) The Urban Fabric (network and grain) directly drives walkability and co-presence through configuration, while simultaneously creating defensible space via semi-private clusters; (3) Building Typology & Verticality facilitates informal surveillance and visual permeability through porous interfaces; and (4) Materiality signals social embeddedness. These spatial conditions collectively determine the social potential outcome of the settlement (Source: Authors).

The conceptual linkages within the framework are grounded in established urban theories. Firstly, the macro-scale territorial enclosure draws on Newman’s [28] concept of defined territories fostering community identity, later observed in informal settlements by Samper et al. [19]. Secondly, at the meso-scale, the link between urban fabric and co-presence is derived from Space Syntax theory, which posits that network integration drives movement and encounter [7,24]. Simultaneously, the identification of defensible clusters aligns with Kamalipour and Peimani’s [12] findings on the protective function of cul-de-sacs. Thirdly, the micro-scale connection between typology and informal surveillance references Jacobs’ [29] ‘eyes on the street,’ confirmed in recent morphological studies by Mehaffy et al. [5]. Finally, material consolidation is interpreted as a proxy for social embeddedness, reflecting Turner’s [30] seminal work on housing as a verb.

3. Methodology

This study adopts a deductive, multi-scalar methodological approach to evaluate the social sustainability of the Saadi neighborhood through the lens of urban morphology. The research design is predicated on the re-operationalization of a pre-validated four-part morphological framework [14]. While the original framework was designed for general morphological reading, in this study, it is specifically adapted to function as a diagnostic tool for identifying “socially supportive spatial conditions.”

3.1. Case Study Context: Saadi Neighborhood

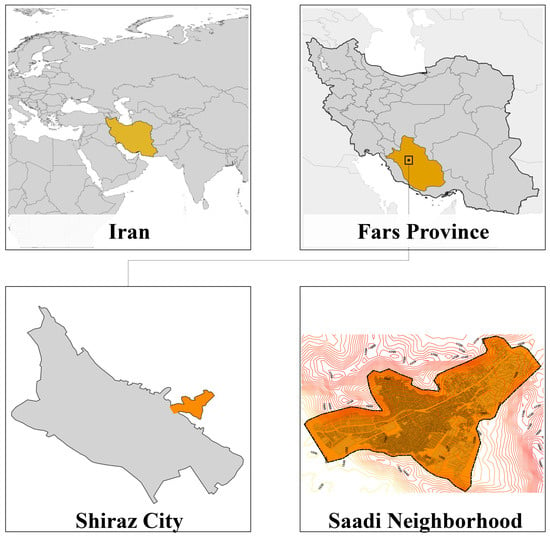

The Saadi neighborhood, located on the northeastern periphery of Shiraz, Iran (Figure 2), serves as the empirical case study. Home to a population exceeding 51,000, the settlement is characterized by a history of incremental, self-organized growth spanning over four decades [31]. Its morphology, shaped by severe topographical constraints and unauthorized construction, presents a complex urban fabric that defies standard planning typologies. This context offers a critical testing ground for evaluating how social logic emerges within an unplanned, high-density environment.

Figure 2.

Location of the Saadi neighborhood within the city of Shiraz, Iran. The map highlights the settlement’s peripheral position and its specific topographical setting, which acts as a physical container for the community (Source: Adapted from [14]).

3.2. The Analytical Framework: Form as a Proxy for Social Logic

To bridge the gap between physical form and social sustainability, the four morphological indicators of the framework are conceptualized as spatial proxies for specific social affordances. The assessment is structured hierarchically, with each morphological component linked to a specific social outcome based on established urban theories:

- Location & Topographical Context (Macro-Scale): This indicator analyzes the settlement’s natural boundaries and siting. It is evaluated for its capacity to create “territorial anchoring”—the degree to which physical enclosure fosters a distinct sense of place and community identity. This indicator draws on Newman’s [28] foundational concept of defined territories, which has been identified by Samper et al. [19] as a critical factor for social stability in informal settlements.

- The Urban Fabric & Network Configuration (Meso-Scale): This component analyzes the interaction between the street network and the urban grain. Drawing on Space Syntax principles, the analysis focuses on how the fine-grained texture and intersection density drive “walkability and co-presence.” As argued by Hillier and Hanson [21] and Askarizad and Safari [7], higher network integration directly correlates with increased potential for social interaction. Simultaneously, the analysis identifies semi-private clusters (cul-de-sacs) that function as “defensible space,” providing safe territories for vulnerable groups as observed by Kamalipour and Peimani [12]. Key metrics include movement hierarchy and intersection density, established predictors of social interaction [32].

- Building Typology & Verticality (Micro-Scale): This indicator examines the interface between the private dwelling and the public street, as well as the height of structures. It assesses the “visual permeability” of frontages to evaluate the potential for “informal surveillance.” This aligns with Jacobs’ [29] theory of ‘eyes on the street,’ where low-rise, active frontages foster a self-regulating environment of safety, a relationship recently quantified in urban morphology by Mehaffy et al. [5].

- Materiality & Construction (Micro-Scale): This indicator interprets the physical fabric as a semiotic system. The transition from temporary to permanent materials is analyzed as a marker of “social embeddedness” and territorial claim. This proxy is grounded in Turner’s [30] theory of incremental housing, where material consolidation serves as tangible evidence of a resident’s long-term investment and commitment to the community structure [33].

3.3. Data Collection and Procedural Steps

A mixed-methods approach was employed, triangulating geospatial data with on-site qualitative surveying. The procedure followed three sequential steps, consistent with the analytical atlas developed in the broader research project:

- Step 1: Geospatial and Network Analysis: High-resolution satellite imagery (0.5 m resolution) and municipal base maps were utilized within a GIS environment (ArcGIS 10.8) to digitize the urban fabric. A detailed network analysis was conducted to categorize circulation paths into a functional hierarchy. This categorization allowed for the evaluation of network integration and the identification of “deep” spaces versus “integrated” axes, interpreting the configurational logic of the settlement without relying on purely abstract simulations [13].

- Step 2: Morphological Mapping: Detailed figure-ground and urban grain maps were produced using CAD and GIS tools to quantify the density and texture of the fabric. These maps highlight the “fine grain” and high building coverage ratio that support pedestrian permeability and social intimacy.

- Step 3: Fieldwork and Ground-Truthing: Systematic field surveys were conducted to validate the spatial data. This involved photographic documentation of social behaviors in different spatial types to corroborate the link between the identified spatial configuration and observed social interaction patterns [5].

4. Results: The Social Potential of Saadi’s Morphology

The application of the multi-scalar framework to the Saadi neighborhood reveals a distinct morphological profile. The findings demonstrate that the settlement’s physical form possesses a coherent spatial logic that actively supports social sustainability through specific configurational attributes defined in the analytical model.

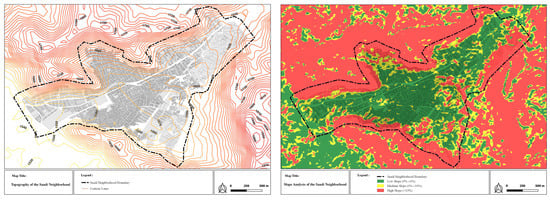

4.1. Macro-Scale: Topographical Enclosure and Territorial Anchoring

The macro-scale analysis reveals that the Saadi neighborhood is morphologically defined by its topographical container. Situated within a natural basin and bounded by steep mountain slopes, the settlement possesses strong physical edges. Consistent with the macro-scale indicators validated in [14], this analysis confirms that topography acts not merely as a constraint, but as a defining “container” for urban growth.

From a social sustainability perspective, this territorial enclosure functions as a critical asset (Figure 3). It fosters a strong sense of “territorial anchoring” and community identity. The topography acts as a natural container for social relations, limiting the fluidity of movement in and out of the settlement and thereby increasing the familiarity and recognition among residents. As posited in the conceptual framework, such defined boundaries are essential for transforming a physical space into a socially meaningful territory.

Figure 3.

Macro-scale topographical analysis of the Saadi neighborhood. The slope analysis reveals the settlement’s containment within a natural basin. This morphological enclosure creates distinct physical boundaries that foster a strong sense of territorial anchoring and community identity among residents (Source: Adapted from [14]).

4.2. Meso-Scale: Urban Fabric Driving Walkability and Defensible Space

The meso-scale analysis of The Urban Fabric (Network & Grain) provides compelling evidence for the settlement’s social potential. Building on the consensus established in [14] regarding the interplay of network and grain, the analysis identifies two critical morphological outcomes:

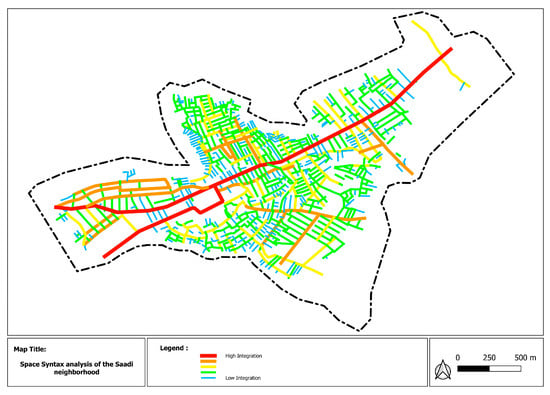

- Walkability and Co-presence: The street network is characterized by a “deformed grid” structure with a high density of intersections and short street segments. Combined with the fine-grained urban texture—identified in [14] as a key determinant of informal morphology—this creates a highly permeable network that naturally slows down traffic and prioritizes pedestrians. Albabely and Alobaydi [34] emphasize that such network properties, particularly connectivity, are the strongest insights for predicting urban pedestrian movement densities. In configurational terms, this morphology drives “walkability” and increases the probability of “co-presence” and casual social exchange (Figure 4). The analysis confirms that the integrated collector streets function as the social spine where public life converges. This reflects Mehta’s [35] taxonomy of sociability, where street characteristics directly invite staying and interaction.

Figure 4. Configuration of the urban fabric and street network. (Left) The figure-ground map illustrates the fine-grained texture which increases pedestrian permeability. (Right) The street network analysis highlights the high density of intersections. Collectively, this configuration drives walkability and increases the probability of social co-presence, while the cul-de-sacs (shown in darker lines) create defensible semi-private clusters (source: adapted from [14]).

Figure 4. Configuration of the urban fabric and street network. (Left) The figure-ground map illustrates the fine-grained texture which increases pedestrian permeability. (Right) The street network analysis highlights the high density of intersections. Collectively, this configuration drives walkability and increases the probability of social co-presence, while the cul-de-sacs (shown in darker lines) create defensible semi-private clusters (source: adapted from [14]).

To empirically validate these observations, a Space Syntax analysis (Axial Integration) was conducted to map the configurational logic of the settlement (Figure 5). The analysis reveals a distinct ‘deformed wheel’ structure. The spectrum ranges from highly integrated axes (shown in red) which form the primary movement skeleton connecting the settlement to the city arterial roads, to the highly segregated segments (shown in blue) which correspond to the residential cul-de-sacs.

Figure 5.

Space Syntax analysis of the Saadi neighborhood (Axial Integration). The map visualizes the configurational hierarchy: red lines indicate highly integrated spaces (social spines/high co-presence), while blue lines indicate segregated spaces (residential cul-de-sacs/defensible space) (Source: Authors).

This quantitative visualization confirms the dual nature of the fabric: the red lines represent the ‘social spines’ where high integration values predict high rates of co-presence and economic vitality, while the vast network of blue segments provides the ‘deep’ spatial structure necessary for privacy.

- Defensible Space in Semi-private Clusters: A pervasive feature of the fabric is the abundance of cul-de-sacs (indicated by the blue lines in Figure 5) branching off the local streets. While conventional planning often criticizes these as “segregated,” the analysis reveals their vital social function as “defensible space.” This observation is consistent with Iranmanesh and Kamalipour [36], who describe the morphogenesis of access networks in informal settlements as a process that naturally creates hierarchical zones of privacy. These semi-private clusters create protected territories where 5–10 households share a common zone, supporting the formation of micro-communities.

Fieldwork validation further corroborates these configurational findings. As illustrated in Figure 6, a clear behavioral distinction exists between the spatial types. The integrated axes (Type A) function as corridors of movement and commerce, characterized by dynamic pedestrian flows. In contrast, the segregated cul-de-sacs (Type B) are not abandoned spaces; rather, they host static social activities. Photographic evidence captures how residents appropriate these deep spaces for children’s play, communal gatherings, and extension of domestic life, validating the hypothesis that spatial segregation in informal settlements often fosters, rather than inhibits, localized social bonding.

Figure 6.

Photographic documentation of social behaviors validating the configurational analysis. (A) High-integration streets functioning as active commercial spines with high pedestrian movement. (B) Deep, segregated cul-de-sacs functioning as safe “outdoor living rooms” for neighborly interactions and communal gatherings, confirming the social value of defensible space (source: Authors).

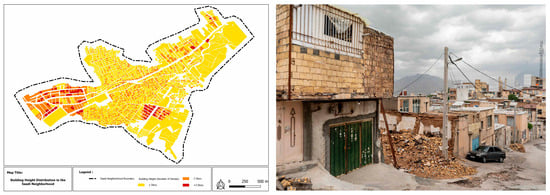

4.3. Micro-Scale: Verticality and Visual Permeability

At the architectural scale, the Building Typology & Verticality indicator reveals a specific spatial relationship. Following the typological classification developed in [14], the dominant typology consists of low-rise (1–2 stories) structures with direct street access. This low vertical profile creates a human-scale ratio between building height and street width.

Field analysis confirms that this morphology results in high “visual permeability.” Unlike high-rise blocks where the street is distant, the low verticality ensures that the street remains visible and audibly connected to the interior of the homes. This porous interface generates a robust system of “informal surveillance” (eyes on the street), creating a self-regulating environment of safety (Figure 7). Shirazi [37] argues that such compact urban forms and neighboring densities are pivotal in fostering social activity and a sense of belonging. The prevalent use of threshold spaces—steps and stoops—further activates this interface, facilitating neighborly contact.

Figure 7.

Micro-scale analysis of building typology and verticality. The prevalence of low verticality (1–2 stories) combined with active frontages ensures high visual permeability between the private dwelling and the public street. This spatial interface facilitates informal surveillance (eyes on the street) and enhances perceived safety (source: adapted from [14]).

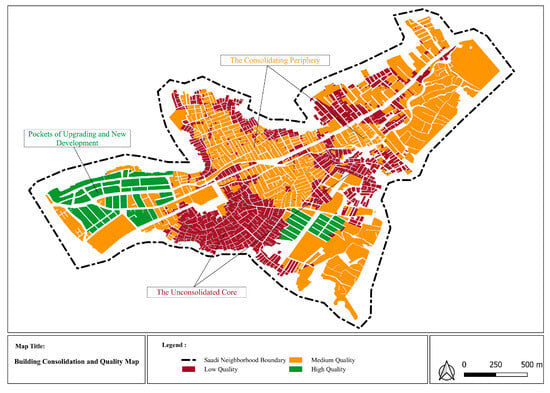

4.4. Micro-Scale: Materiality as Social Embeddedness

Finally, the material analysis reveals a landscape of “incremental consolidation.” The spatial distribution of building quality shows a clear progression from temporary materials in the core to permanent brick and concrete in the consolidating zones.

As argued in [14], materiality in informal contexts functions as a semiotic system. Here, this material solidification is interpreted as a tangible signal of “social embeddedness.” The investment in defining boundaries and upgrading structures articulates the residents’ claim to the city and their long-term commitment to the community (Figure 8). As outlined in the framework, this transition from provisional to permanent morphology serves as a physical proxy for social stability and resident resilience.

Figure 8.

Spatial patterns of incremental consolidation. The map visualizes the distribution of building quality, showing a progression from temporary materials in the core to permanent structures in the periphery. This transition in materiality serves as a tangible proxy for social embeddedness and signals the residents’ long-term investment in the community te23rritory (source: adapted from [14]).

5. Discussion

The empirical findings from the Saadi neighborhood provide a robust counter-narrative to the prevailing discourse that equates informal urbanism with spatial disorder. Instead, the morphological analysis reveals a coherent “social logic of space” embedded within the settlement’s physical fabric. This section discusses the implications of these findings, arguing that the specific spatial configurations identified—the integrated pedestrian network and the defensible micro-clusters—function as critical infrastructure for social sustainability.

5.1. The Social Logic of Organic Form: Synergy of Configuration and Activity

The analysis demonstrates that the “organic” or “deformed” grid of Saadi is not a symptom of chaos, but an adaptive response that prioritizes social interaction. Consistent with recent findings in Space Syntax research [7], the high intersection density and short street segments within the settlement naturally slow down movement, increasing the probability of “co-presence” among residents. Karimi [25] argues that these configurational structures are not accidental but are the primary generators of “social spaces,” acting as the invisible framework that orchestrates human encounter.

However, social vitality is not solely a product of spatial configuration; it is equally dependent on the activity character of the space. As Montgomery [38] argues, successful urban places emerge from the interplay of form and activity. In Saadi, the integrated street segments identified in the analysis are not empty channels; they are characterized by a high degree of functional mix, lining with small-scale shops, workshops, and communal services. This aligns with Mehta’s [35] taxonomy of sociability, which suggests that street characteristics—specifically the permeability of edges and the presence of commercial nodes—directly invite staying behavior and static social interaction.

Consequently, the morpho-functional synergy in Saadi transforms the potential for movement into sustained social vitality. Compared with the highly segregated, car-oriented street layouts common in many planned districts, this configuration creates a continuous “interface of encounter” [15]. This validates Hillier’s [11] proposition that organic patterns in cities often represent “sustainable forms” generated by movement economies, which naturally evolve to maximize accessibility and social exchange.

5.2. Morphology as a Buffer Against Socio-Spatial Inequality

In the context of the Special Issue’s focus on socio-spatial inequality, the findings offer a significant insight. While the Saadi neighborhood suffers from infrastructural deprivation (lack of formal services), its morphology offers a distinct form of “socio-spatial resilience” [15]. The human-scaled environment democratizes access to the public realm; the street is fully accessible to the elderly, children, and those without private vehicles, addressing the issue of mobility justice.

This finding resonates strongly with Sharifi and Murayama’s [6] study of Iranian cities, which highlights how traditional urban forms—characterized by compactness and walkability—have historically sustained social bonds that are often compromised in modern, dispersed developments. In Saadi, the “compact urban form” facilitates frequent neighboring and social activity, a correlation strongly supported by Shirazi [37] and Ali et al. [8], who found similar positive impacts of urban form on social sustainability indicators in the Middle Eastern context.

Furthermore, the prevalence of “deep spaces” (cul-de-sacs) provides a layer of passive security and territorial control. These semi-private clusters create safe havens for vulnerable demographics, mitigating some of the harsher effects of economic marginalization. As Rapoport [17] posits in his man-environment framework, these physical elements act as non-verbal cues that define territory, allowing residents to claim ownership and exercise informal control over their immediate environment.

Comparatively, these findings align with observations in other Global South contexts. For instance, studies on the favelas of Latin America similarly highlight how steep topography and organic street networks, despite hindering vehicular access, create strong internal social cohesion and surveillance [20]. Similarly, research on peri-urban settlements in sub-Saharan Africa suggests that material consolidation is a universal proxy for social stability [22]. However, a key distinction in the Iranian context, as observed in Saadi, is the profound influence of inward-looking privacy (the courtyard typology). This creates a sharper distinction between the semi-private cul-de-sac and the public thoroughfare compared to the more porous street-life found in some Latin American cases. This suggests that while the “logic” of informal morphology is globally recognizable, its specific social performance is modulated by local cultural codes.

5.3. Implications for Practice: From Regularization to Surgical Upgrading

The diagnostic insights provided by this form-based analysis have direct implications for urban planning practices. Standard upgrading approaches often involve “regularization”—widening streets and imposing orthogonal grids—which risks destroying the fine-grained fabric that sustains the community’s social life [39]. Wahab [4] emphasizes that transforming informal settlements into liveable communities requires strategies that go beyond mere physical standardization to address the unique socio-functional needs of residents.

The results of this study advocate for a “surgical upgrading” approach. Instead of erasing the existing morphology, interventions should aim to enhance the specific spatial affordances identified. For instance, maintaining the narrow street profiles preserves the pedestrian dominance and social intimacy, while targeted infrastructural improvements (such as lighting or paving) can be applied to the “integrated cores” to maximize their social potential. This approach is supported by Barella [40], who advocates for “acupunctural” and strategic GIS implementations to support community-oriented upgrading without displacing the social fabric.

This strategy aligns with the concept of “incremental urbanism” described by Iranmanesh and Kamalipour [36], where the morphogenesis of the access network is respected as an evolving process. By identifying key morphological nodes through Space Syntax, planners can intervene precisely where it matters most, yielding significant social benefits without the disruption of wholesale redevelopment [41].

5.4. Rethinking Informality Through Social Potential

By interpreting physical morphology as an indicator of social potential, this study contributes to a growing shift in urban research—from viewing informality as a problem to understanding it as a spatially rich, socially productive urban landscape. Dovey [18] conceptualizes such settlements not as disordered slums, but as “complex adaptive assemblages,” where the urban form evolves incrementally through the micro-interactions of residents.

The Saadi neighborhood exemplifies this adaptability. The visibility and morphology of the settlement play a crucial role in shaping the social interface between public and private realms, as noted by Dovey and King [20]. The physical solidification of the fabric serves as a proxy for social stability, challenging the notion that informality is inherently temporary or unstable. In this way, the study reframes informal settlements as environments where social life is deeply embedded in the spatial structure. Peimani and Kamalipour [42] suggest that interventions in the Global South must assemble urban design in a way that respects these existing forms of urbanity. This reconceptualization opens new pathways for socially responsive upgrading strategies, particularly in cities where morphological resilience and social vitality often coexist with infrastructural scarcity.

6. Conclusions

This research was premised on the hypothesis that the physical form of informal settlements contains a latent social logic that can be analytically interpreted. Through the application of a multi-scalar morphological framework to the Saadi neighborhood in Shiraz, the study has demonstrated that urban morphology serves as a powerful diagnostic tool for identifying the spatial potential for social sustainability.

However, it is crucial to acknowledge that physical form acts as a container rather than a sole determinant. While morphology creates the necessary spatial affordances for interaction, social sustainability is ultimately realized through the interplay of this physical structure with the functional characteristics of the area (such as land-use mix and economic activities) and the agency of its residents.

6.1. Synthesis of Findings

The empirical analysis confirms that the “organic” grid of Saadi operates according to a discernible configurational logic. The high connectivity and intersection density were found to facilitate movement economy, providing the structural prerequisite for co-presence. Yet, as highlighted in the discussion, this spatial potential is activated by the settlement’s functional character—specifically the mixed-use nature of the integrated streets.

Similarly, the identification of “deep spaces” (semi-private cul-de-sacs) highlighted the settlement’s capacity to generate defensible territories. These morphological attributes do not guarantee social cohesion on their own, but they provide a supportive spatial scaffolding that protects vulnerable groups and allows community life to flourish, distinguishing the self-organized fabric from the alienating sterility often found in rigid, mono-functional master plans.

6.2. Policy Implications: Towards Morphologically Sensitive Upgrading

The diagnostic capacity of this form-based analysis offers a critical foundation for shifting urban policy from “eradication” to “integration.” The results suggest that top-down interventions which impose orthogonal grids or widen streets risk dismantling the very spatial mechanisms that sustain the community’s social capital. Instead, a “morphologically sensitive upgrading” strategy is advocated. This approach involves:

- Recognizing Spatial Assets: Identifying and protecting the integrated pedestrian spines and semi-private clusters as essential social infrastructure.

- Surgical Intervention: Instead of generic infrastructure provision, interventions should be acupunctural and specific. For example, paving and lighting the “integrated” collector streets identified by Space Syntax can boost their function as economic spines. Conversely, in the deep cul-de-sacs, interventions should focus on stabilizing slopes and providing small-scale communal water points or pocket parks, reinforcing their role as safe play areas for children without disrupting the private social fabric [43].

- Enabling Incrementalism: Supporting the user-led process of consolidation through tenure security and technical assistance, acknowledging that the physical solidification of the fabric is a proxy for social stability [19].

6.3. Future Research Directions

While this study focused on the physical determinants of social sustainability, future research could productively integrate this morphological framework with qualitative ethnographic methods to capture the lived experience of these spaces more directly. Additionally, comparative applications of this framework across diverse informal typologies in the Global South would help to establish a broader “taxonomy of informal social logic,” further refining the tools available to urban planners and designers.

In conclusion, achieving social sustainability in the rapidly urbanizing Global South requires a paradigm shift in how we read informal cities. By learning to interpret the social potential embedded in their physical form, urban practitioners can move beyond deficit-based narratives and develop interventions that respect, sustain, and enhance the inherent vitality of these communities [2].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.N.; Methodology, S.N.; Software, S.N.; Validation, B.O.V.; Formal analysis, S.N.; Writing—review & editing, B.O.V.; Supervision, B.O.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alesaily, Z.; Albialy, A. Future Cities: A Bibliometric Review, 1875 to 2024. Sustain. Futures 2025, 7, 100801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat. World Cities Report 2022: Envisaging the Future of Cities; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2022; Available online: https://unhabitat.org/wcr/2022/ (accessed on 25 December 2025).

- Larimian, T.; Sadeghi, A. Measuring urban social sustainability: Scale development and validation. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2021, 48, 621–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, B. Transforming Nigerian informal settlements into liveable communities: Strategies and challenges. In The 2017 Edition of Mandatory Continuing Professional Development Programme (MCPDP) of the Nigerian Institute of Town Planners; Nigerian Institute of Town Planners: Abuja, Nigeria, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehaffy, M.W.; Porta, S.; Rofè, Y.; Salingaros, N.A. Urban nuclei and the geometry of streets: The ‘emergent neighborhoods’ model. Urban Des. Int. 2020, 25, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A.; Murayama, A. Changes in the traditional urban form and the social sustainability of contemporary cities: A case study of Iranian cities. Habitat Int. 2013, 38, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askarizad, R.; Safari, H. The influence of social interactions on the behavioral patterns of the people in urban spaces. Cities 2020, 101, 102687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.H.; Al-Betawi, Y.N.; Al-Qudah, H.S. Effects of urban form on social sustainability–a case study of Irbid, Jordan. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 2019, 11, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B. Centrality as a process: Accounting for attraction inequalities in deformed grids. Urban Des. Int. 1999, 3, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, K. A configurational approach to analytical urban design: ‘Space syntax’ methodology. Urban Des. Int. 2012, 17, 297–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B. (Ed.) Spatial Sustainability in Cities: Organic Patterns and Sustainable Forms; Royal Institute of Technology (KTH): Stockholm, Sweden, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kamalipour, H.; Peimani, N. Assemblage thinking and the city. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 46, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askarizad, R.; Daudén, P.J.; Garau, C. Exploring the role of configurational accessibility of alleyways on facilitating wayfinding transportation within the organic street network systems. Transp. Policy 2024, 157, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezhadmasoum, S.; Vehbi, B.O. An Integrated Morphological Framework for Analyzing Informal Settlements: The Case of Saadi Neighborhood, Shiraz. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.A.; Ubarevičienė, R.; Van Ham, M. Morphological evaluation and regeneration of informal settlements: An experience-based urban design approach. Cities 2022, 128, 103798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperiale, A.J.; Vanclay, F. Re-designing social impact assessment to enhance community resilience for disaster risk reduction, climate action and sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 1571–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapoport, A. Human Aspects of Urban Form: Towards a Man—Environment Approach to Urban Form and Design; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovey, K. Informal urbanism and complex adaptive assemblage. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2012, 34, 349–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samper, J.; Shelby, J.A.; Behary, D. The paradox of informal settlements revealed in an ATLAS of informality: Findings from mapping growth in the most common yet unmapped forms of urbanization. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovey, K.; King, R. Forms of informality: Morphology and visibility of informal settlements. Built Environ. 2011, 37, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moudon, A.V. Built for Change: Neighborhood Architecture in San Francisco; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Carrilho, J.; Trindade, J. Sustainability in Peri-Urban Informal Settlements: A Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memarian, G.; Brown, F.E. Climate, culture, and religion: Aspects of the traditional courtyard house in Iran. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 2003, 20, 181–198. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B.; Hanson, J. The Social Logic of Space; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, K. The configurational structures of social spaces: Space syntax and urban morphology in the context of analytical, evidence-based design. Land 2023, 12, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia Ben Cherifa, Y.; Rejeb Bouzgarrou, A.; Claramunt, C.; Rejeb, H. Re-appropriation of public spaces in the Tunisian city of Sousse post COVID-19 pandemic. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2025, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutini, V.; Di Pinto, V.; Rinaldi, A.M.; Rossini, F. Informal settlements spatial analysis using space syntax and geographic information systems. In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2019; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, O. Defensible Space: Crime Prevention Through Urban Design; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, J.F.C. Housing by People: Towards Autonomy in Building Environments; Marion Boyars: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Statistical Center of Iran (SCI). Population Distribution of Informal Settlements in Iran; SCI: Tehran, Iran, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yamu, C.; van Nes, A.; Garau, C. Bill Hillier’s Legacy: Space Syntax—A Synopsis of Form and Social Function of the City. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheuya, S.A. Housing Transformations and Urban Livelihoods in Informal Settlements: The Case of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; Spring Center: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; Dortmund University: Dortmund, Germany, 2004; Available online: https://sol.unibo.it/SebinaOpac/resource/UBO02676718 (accessed on 25 December 2025).

- Albabely, S.; Alobaydi, D. Impact of Street Network Properties on Urban Pedestrian Movement Densities: Insights from Iraq. Int. Soc. Study Vernac. Settl. 2024, 11, 136–151. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, V. Streets and social life in cities: A taxonomy of sociability. Urban Des. Int. 2019, 24, 16–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranmanesh, A.; Kamalipour, H. A configurational morphogenesis of incremental urbanism: A comparative study of the access network transformations in informal settlements. Cities 2023, 140, 104444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, M.R. Compact urban form: Neighbouring and social activity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, J. Making a city: Urbanity, vitality and urban design. J. Urban Des. 1998, 3, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, R.A.; Malhotra, R.; Buddhiraju, K.M. Identifying informal settlements using contourlet assisted deep learning. Sensors 2020, 20, 2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barella, J. Strategic and acupunctural GIS implementation within community-oriented organizations: Evidence-based insights from a South African participatory action research for informal settlement upgrading. Cartographica 2020, 55, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalipour, H. Improvising places: The fluid ecology of informal urbanism. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peimani, N.; Kamalipour, H. Assembling transit urban design in the global South: Urban morphology in relation to forms of urbanity and informality in the public space surrounding transit stations. Urban Sci. 2022, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hin, L.L.; Xin, L. Redevelopment of urban villages in Shenzhen, China–An analysis of power relations and urban coalitions. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.