Abstract

Renewable energy communities are emerging as key players in the sustainable energy transition, yet there is a lack of systematic approaches for evaluating the digital tools that support their development and operation. This study proposes a comprehensive methodology for assessing tools for supporting renewable energy communities, based on a system of key performance indicators and the multi-criteria decision analysis framework method. Twenty-three specific sub-criteria were defined and scored for each tool, and a weighted sum model was applied to aggregate performance. To ensure robust comparison, criteria weights were derived using both expert judgement (pairwise comparisons of ranking and analytical hierarchy process) and objective data-driven methods (the entropy-based method and the criteria importance through intercriteria correlation weighting method). The framework was applied to a diverse sample of contemporary renewable energy community’s tools, including open-source, commercial, and European Union project tools. Key findings indicate that some of the tools have shown noticeable rank shifts between expert-weighted and data-weighted evaluations, reflecting that expert opinions emphasize technical and operational features while objective variability elevates environmental and economic criteria. This assessment enables stakeholders to compare energy community tools based on structured criteria, offering practical guidance for tool selection and highlighting areas for future improvement.

1. Introduction

The transition to renewable energy is a central priority of modern energy policy, driven by climate goals, energy security concerns, and declining technology costs. Renewable energy sources (RES) are now recognized as essential for building sustainable and resilient energy systems. At the European Union (EU) level, directives such as the Renewable Energy Directive (EU) 2018/2001 [1] and its amendment Directive 2023/2413 [2], together with the Internal Electricity Market Directive (EU) 2019/944 [3], set binding targets for renewable deployment and promote citizen participation in community-based initiatives.

Within this broader framework, Renewable Energy Communities (RECs) and Citizen Energy Communities (CECs) have emerged as key instruments for local empowerment, active consumer involvement, and the integration of distributed renewables. The concept of RECs represents a more participative and democratic model for organising and managing energy systems, reflecting the growing societal interest in alternative, citizen-driven arrangements. RECs are distinguished by several core principles: inclusive and voluntary governance, citizen-centric ownership and effective control, and a primary purpose oriented towards social and environmental benefits rather than financial profit [4]. Accelerating REC development is not only a policy goal but also a socio-technical necessity for achieving the EU’s 2040 climate neutrality targets, as decentralized systems enhance resilience and citizen engagement [4].

As decentralized energy production expands, demand for planning and management tools has also increased. They have become essential for efficient, optimized, and well-controlled implementation of energy communities (ECs) within energy systems, providing technological support for system optimization, energy modelling, and data management to ensure effective operation and help achieve social and economic benefits for the communities [5]. Various comparisons and evaluations of energy modelling tools (EMTs) and cases of their use can be found in the recent academic literature. Reviews are usually focused on software tools for urban energy system modelling [6], urban building energy monitoring [7], and hybrid energy system designs [8].

For instance, the authors of [9] provide a valuable initial overview of digital tools supporting RECs, although the analysis remains primarily descriptive and limited to qualitative classification across design, creation, and operation phases. The evaluation does not apply a formalized scoring system, a weighting mechanism, or a structured decision-support framework, which restricts reproducibility and comparability across tools. Additionally, the scope of assessment omits key functional areas that are increasingly critical for REC implementation, such as EV integration, demand response aggregation, user-centric design features, and support for socio-legal frameworks. No attention is given to usability aspects, participatory tools, or how tools address localized regulatory or governance contexts—all of which are essential for real-world community adoption and scalability. In this way, while the study offers a broad typological landscape of available tools, it leaves unaddressed the question of which ones perform best under varying user priorities or functional requirements.

The authors of [10] propose a qualitative evaluation approach for energy system modelling frameworks, examining properties like transparency (open-source), collaborative potential, and structural flexibility. Their approach is tailored to the structural and philosophical characteristics of modelling tools—primarily at the developer and framework level—and therefore lacks consideration of emerging themes crucial to REC tools, such as social participation, regulatory adaptation layers, and open interface usability.

A systematic review in [11] offers a timely and structured review of twelve EMTs relevant to RECs; the focus here lies predominantly on the representation of data inputs, simulation features, and technical outputs across a general REC planning workflow. Although the study identifies which tools support techno-economic and, to a lesser extent, spatial and environmental modelling, it does not apply a formal scoring system or weighting mechanism to evaluate tool performance systematically. Their assessment is qualitative in nature and does not point out the relative importance of each criterion. In addition, the review highlights—but does not deeply explore—the lack of social participation tools, EV integration, or user-oriented outputs such as dashboards and governance support. Moreover, the authors do not benchmark tools using real-world operational criteria such as interoperability, usability, or readiness for community deployment, leaving a gap in actionable decision support for creators of RECs.

Paper [12] emphasizes that most academic modelling of EC focuses primarily on technical and economic outputs, often neglecting dimensions such as co-creation, educational support, and citizen empowerment. This mirrors gaps identified in digital tool assessments, where features enabling collaborative design, shared decision-making, and local capacity-building are rarely incorporated. The authors of [13], through qualitative interviews, further illustrate the evolving role of digital mediation within RECs. Their study finds that while tools increasingly support technical functions like monitoring and demand response optimization, stakeholders express a clear demand for more participatory and relational features. These include capabilities for peer knowledge exchange, shared project initiation, and coordination with external institutional actors—functionalities that are largely absent in current tool offerings.

Article [14] offers a technically detailed review of open datasets and tools for local ECs, serving as a valuable technical catalogue. However, it lacks a systematic evaluation of platform usability and practical applicability from a stakeholder perspective. Key dimensions such as user participation, regulatory adaptability, and educational support are overlooked, and no structured comparison or decision-support framework is provided to guide tool selection based on multidimensional performance.

Across literature, a range of methodological approaches have been used to evaluate and compare EMTs. A common approach is feature-based benchmarking: many reviews compile a checklist of functionalities and assess which tools have which features. For example, Ref. [9] maps each tool against services needed in each project phase (design, creation, operation), essentially creating a feature matrix to identify strengths and voids. Similarly, Ref. [11] compares tools by the types of inputs they require and the outputs they produce (technical, financial, environmental, spatial), using a structured comparison framework. These studies rely on document analysis and tool documentation to score capabilities, often presented in comparative tables. Another technique employed is multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA). Some reviews explicitly rank or score tools against multiple criteria. For instance, broader energy system model evaluations have introduced qualitative scoring on dimensions like transparency, complexity handling, and collaboration support. According to [15], stakeholder integration in energy system modelling remains limited, as most frameworks still prioritize technical and economic performance over participatory and social dimensions. Their systematic review, based on a SWOT analysis of more than eighty studies, highlights that current modelling tools rarely include mechanisms for co-design, user feedback, or stakeholder interaction throughout the modelling process. The authors argue that this technocentric orientation reduces the applicability of such tools for community-level energy planning and decision-making. They identify opportunities for improvement through the adoption of hybrid approaches—combining MCDA, participatory modelling, and digital interfaces—to better capture local priorities, social acceptance, and behavioural factors. These findings reinforce the relevance of incorporating social and participatory criteria into the KPI framework used to evaluate REC tools.

Some researchers have taken a case study simulation approach to tool evaluation, which are applied to a common scenario to compare results and user experience. For example, Ref. [16] conducted a practical comparison of an optimization model vs. a simulation model for the same municipal energy system, highlighting differences in outcomes and modelling effort. Though not focused on REC tools per se, this demonstrates the value of side-by-side case studies to reveal how the choice of tools can influence planning recommendations.

Another important methodological dimension concerns the integration of stakeholder perspectives and usability evaluations into tool assessment. Although a relatively uncommon occurrence, some studies have included surveys or interviews to capture user feedback regarding the functionality and applicability of EMTs. For instance, the Finnish study on digital mediation within RECs collected practitioner insights on missing or underdeveloped platform features, highlighting the need for participatory design and relational functionalities [13]. Moreover, the authors of paper [15] have called for the inclusion of user-centred evaluation criteria—such as interface usability, documentation quality, and the learning curve—within tool benchmarking frameworks. Nevertheless, quantitative usability metrics such as the time required to configure simulations, the frequency of operational errors or user satisfaction ratings, remain largely absent from the comparative literature. This methodological gap indicates that most reviews still assess tools based on documented functionalities rather than empirical user testing, limiting the understanding of real-world performance and accessibility.

Despite the proliferation of digital tools designed to support RECs, existing evaluations remain fragmented and limited in scope. Prior studies have primarily focused on technical modelling capabilities or high-level descriptions of tool functionalities, often omitting critical dimensions such as environmental performance, social engagement, and regulatory adaptability. Key reviews in the field have revealed several recurring gaps: the limited integration of electric mobility and multi-vector energy systems, insufficient support for participatory design and citizen interaction, and an overarching emphasis on feasibility indicators at the expense of broader sustainability and usability considerations. Moreover, while some frameworks qualitatively assess platform features, they often lack reproducible scoring methodologies, structured prioritization of evaluation criteria, and actionable insights for community stakeholders. Crucially, no existing study provides a comprehensive, multi-domain comparison of REC tools using a formalized KPI and weighting framework. The absence of reproducible scoring and stakeholder-sensitive prioritization leaves a significant gap in practical decision support for real-world REC development.

To address these gaps, this study introduces a structured and reproducible evaluation framework that can rank REC tools according to multiple stakeholder-valued criteria. The framework combines key performance indicators (KPIs) with MCDA. The framework spans six functional criteria—technical, operational, economic, environmental, social, and quality and adoption—disaggregated into 23 measurable sub-criteria. The framework applies stakeholder-weighted aggregation using the weighted sum model (WSM) [17] to capture the priorities of non-expert community members. Each criterion is scored on a normalized scale, and aggregated scores are calculated using both expert-informed and data-driven weighting methods. This dual-layered approach enables sensitivity analysis to reflect varying stakeholder priorities and enhances transparency in the comparison of tools.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- A comprehensive KPI–MCDA framework for evaluating REC software across technical, economic, environmental, social, usability, and governance criteria is presented;

- Incorporation of multiple weighting methods (stakeholder-derived vs. data-driven) is used to enhance transparency and replicability;

- Demonstration of the framework on representative tools to highlight underexplored features such as EV integration, participatory co-design modules, usability, transparency metrics, and legal adaptability is offered.

By structuring evaluation in this way, our approach moves beyond prior studies to provide actionable, multidimensional performance scores that reflect the diverse needs of REC practitioners and community stakeholders.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the methodology, including tool selection criteria, the KPI calculation and the MCDA process; Section 3 reports the evaluation results across a sample of tools; the discussion and the conclusions are summarised in the last two sections.

2. Methodology

The selection of the tools was guided by two eligibility criteria designed to ensure that each entry could be evaluated transparently and on equal methodological footing. First, a platform or tool had to be documented through an official, publicly accessible source—such as a project website, product page, user or administrator manual, or open repository—detailing functionalities relevant to REC. Second, the platform had to be accessible for independent inspection, either via a public demo or sandbox, a time-limited trial, an openly available installer or codebase, or sufficiently detailed technical documentation to enable functional verification without vendor mediation. Solutions were excluded when they failed to satisfy either of these two conditions.

Using this procedure, the authors first compiled a longlist of 30 REC-related tools from peer-reviewed articles, EU project deliverables, and structured web searches. To capture practice-oriented tools under-represented in journals, the authors complemented the literature scan by systematically querying official project and vendor websites, documentation portals, user manuals, open repositories, demo or sandbox instances, and publicly available installers using controlled keywords (such as ‘REC tool/platform’, ‘energy sharing software’, ‘community microgrid’, ‘REC toolkit’, ‘EV smart charging for RECs’). Application of the two eligibility criteria described above reduced this list to 19 tools. No geographical restrictions were imposed: both European and global tools were considered and included whenever they met the documentation and accessibility requirements.

In addition to the desk-based review, the authors interacted directly with those tools that provide open-source distributions or public demo/sandbox environments. In practice, MiGRIDS Lite, OpenEMS, PROCSIM and the Rectool Simulator were installed or accessed via their publicly available repositories or web interfaces, and representative workflows were tested to validate the documented functionalities. For the remaining tools such as Cleanwatts, Hive Power FLEXO, Powerledger, GreenPocket Energy Cockpit, BECoop, UP-STAIRS, there was no access and the assessment relied on official documentation.

Building on this corpus, the authors conduct a structured desk-based [18,19] evaluation of digital tools that support the design, creation, or operation of RECs. The objective is to compare alternatives on a common, multi-criteria basis that reflects the needs of a non-expert audience (e.g., consumers or/and community initiators), while remaining transparent and reproducible.

The methodology has two pillars:

- A KPI framework structured across six dimensions;

- A scoring rubric with normalized 0/0.5/1 criteria and stakeholder-weighted aggregation via MCDA, using a WSM [20,21,22] as the primary ranking method.

MCDA methodologies have been widely applied across areas including renewable energy planning, transportation, sustainability assessment, quality management, and supply chain optimization. Their adaptability allows researchers to customize criteria and weighting systems to adapt the methodology to specific context of research [21]. MCDA provides a structured and systematic framework for managerial decision-making by explicitly incorporating multiple criteria or objectives into the evaluation and ranking of alternative options. MCDA formalizes the decision-making process, thereby enhancing both the quality of decisions and the quality of decision-making practices, by explicitly documenting the applied criteria, their relative weights, and the rationale behind scoring [22].

This KPI–MCDA decision framework is developed for structured evaluation, which combines a set of KPIs with MCDA techniques to guide tool selection. It includes four steps: (1) define evaluation criteria and sub-criteria; (2) score each alternative using a standard rubric (e.g., 0/0.5/1); (3) assign weights to criteria (via expert judgment or data-driven methods); and (4) compute overall scores using the weighted sum model. This structure can be adapted to other domains by modifying the criteria and scoring rules while retaining the same MCDA logic.

This decision framework is not limited to REC tools; the same approach of KPI selection, scoring, and weight sensitivity analysis can be applied to evaluating alternatives in other domains of sustainability or technology selection.

The KPI assessment methodology includes five consecutive steps for evaluation of each tool (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

KPI assessment methodology.

Figure 1 summarises the KPI assessment methodology, which consists of five consecutive steps that are described in detail in Section 2.1, Section 2.2, Section 2.3 and Section 2.4. First, the KPI definition step (Section 2.1) identifies the main performance domains that describe the tools’ functional and qualitative characteristics. Second, the ranking of criteria (Section 2.2) specifies the most relevant sub-criteria within each domain and organises them according to their importance. Appendix A provides the full scoring table and the three-level (0/0.5/1) scoring rubric for each sub-criterion. Third, each tool is evaluated against all sub-criteria within every KPI dimension (Section 2.2), reflecting its actual features, functionality, and performance; the resulting sub-criterion scores are then aggregated into dimension-level KPIs, forming the input dataset for the subsequent MCDA step (Section 2.3). Fourth, the weight coefficients for the six KPI dimensions are calculated (Section 2.4), determining how significant each criterion is compared to the others by applying both expert-judgement-based and objective data-driven methods. Finally, the weighted sum model (WSM) is implemented (Section 2.3) to combine all weighted scores into a single overall index for each tool, enabling their comparative ranking and the identification of top-performing solutions.

The authors chose a simple three-level scoring scheme to balance granularity with consistency in evaluation. A binary 0/1 scale was too coarse to capture partial fulfilment of criteria, while a more fine-grained scale could give a false sense of precision given the qualitative nature of many criteria. The midpoint score of 0.5 allows the authors to indicate that a tool partially meets a criterion.

2.1. KPI Definition

Based on the analysis of existing studies on KPI frameworks [23,24,25,26,27] for energy systems and community-oriented systems, six main KPI dimensions were defined to evaluate digital tools for REC: technical modelling, operational, economic, environmental, social, and quality and adoption (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

KPI framework for evaluating digital tools for REC.

2.2. KPI Sub-Criteria

The second step focuses on identifying and structuring detailed criteria within each KPI dimension.

The 23 KPI sub-criteria were derived from a longlist of indicators collected from previous KPI frameworks for ECs, studies on energy system and microgrid tools, and the documentation of existing REC-related platforms [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. The team of authors then refined this list by (i) retaining only those indicators that are directly relevant for evaluating digital tools supporting RECs, (ii) merging or removing redundant items with overlapping meaning, and (iii) ensuring that each remaining sub-criterion can be operationalised consistently from publicly available documentation, demos or open-source code.

2.2.1. Technical Modelling

In the technical modelling (TECH) KPI dimension, the authors identified and evaluated a set of sub-criteria that capture the platform’s ability to represent the technical complexity of RECs and their multi-energy interactions. These sub-criteria address the modelling depth, analytical scope, and realism of technical functionalities.

The ‘Energy vectors’ criterion (TECH_vec) [28] assesses the extent to which a platform models multiple energy carriers and their couplings within a community context. Multi-vector capability is essential for representing sector coupling (e.g., electricity-to-heat via heat pumps, combined heat and power, thermal storage, and electric-vehicle smart charging), thereby enabling integrated techno-economic assessment rather than electricity-only appraisals. A platform scores higher when it can model several carriers and their interactions, rather than electricity alone.

The ‘Optimisation’ criterion (TECH_opt) evaluates whether the platform goes beyond basic simulation to offer design or operational optimization, and whether the optimization objective space is single- or multi-dimensional.

The ‘Simulation capability’ (TECH_sim) criterion evaluates the temporal fidelity and breadth of the simulation engine used for techno-economic assessment and operational studies. Higher capability entails time-series simulation over full annual cycles, sub-hourly granularity where needed (e.g., EV/BESS control), and consistent mass-/energy-balance handling across coupled vectors [29].

The ‘Forecasting’ (TECH_forec) criterion assesses whether the platform provides endogenous forecasting of key time series relevant to REC planning and operation (e.g., load/consumption, renewable generation).

The ‘LV/MV grid constraints or losses’ (TECH_grid) criterion addresses the representation of distribution-network feasibility—voltage bounds, thermal limits, losses, reverse power flows, and curtailment—at low and medium voltage levels. For RECs, distribution constraints often determine admissible asset sizing and operational envelopes [30].

The ‘Spatial/GIS capabilities’ (TECH_spat) criterion evaluates geospatial awareness and place-based modelling, including building-level siting, roof orientation and shading, community perimeter rules (e.g., same-substation constraints), and proximity to thermal networks or other infrastructures. Spatialized modelling is a prerequisite for actionable planning and compliance with jurisdiction-specific REC boundaries.

2.2.2. Operations and Control

The Operations and Control (OPER) dimension assesses whether a platform is ready for day-to-day operation of an EC: running diverse assets, ingesting telemetry, producing actionable analytics and reports, settling energy sharing, exposing reliable interfaces, and coordinating flexibility.

The criterion ‘Asset classes’ (OPER_ascl) valuates the scope and diversity of assets that the platform can natively model, monitor, or control within an energy community framework. It reflects both the breadth (the variety of asset types) and depth (the level of technical detail and control granularity) of device integration [31].

The ‘Analytics and reporting’ criterion (OPER_analyt) [32] evaluates the platform’s data analytics, performance assessment, and reporting capabilities, which are essential for operational optimization and strategic decision support. It covers the transformation of raw telemetry data into actionable insights, including statistical analysis, KPI tracking, detection of anomalies, and forecasting of trends. Advanced tools integrate predictive or prescriptive analytics, provide automated performance summaries, and enable custom report generation for various stakeholders (operators, policymakers, or community members).

‘Demand response and flexibility aggregation’ (OPER_flex) [33] assesses the platform’s ability to aggregate and activate flexibility from distributed energy resources (DERs) and controllable loads—including batteries, heat pumps, and smart appliances. It focuses on how effectively the system can enrol flexible assets, predict available flexibility, nominate resources for activation, and execute automated control strategies in response to internal signals or market events.

The ‘EV management’ sub-criterion (OPER_EV) evaluates the platform’s native capabilities for EV charging management, including smart-charging policies and schedule configuration. Emphasis is placed on the coordination of charging with price/tariff signals, renewable generation forecasts, and distribution-network constraints, as required for cost-effective and grid-compliant operation in energy communities.

2.2.3. Economic

The economic dimension of KPI (ECON) evaluates a platform’s capability to support techno-economic assessment and market realism [34].

‘Financial indicators’ (ECON_fin) assess whether the platform implements standard project-finance indicators [35] for community-scale assets and portfolios, enabling rigorous techno-economic appraisal and comparability across scenarios.

The sub-criterion ‘Tariff/market models’ [12] (ECON_tar) evaluates how realistically the platform represents end-user tariffs and market price signals—from flat/static rates to time-of-use, dynamic wholesale/retail, or real-time pricing—since tariff fidelity materially affects REC economics and operational strategies.

‘Sensitivity analysis’ (ECON_sens) tests the robustness of techno-economic results to variation in key drivers (prices, load/generation, discount rate, etc.), via batch ‘what-if’ runs or formal uncertainty modules.

‘Benefit-sharing calculators’ [36] (ECON_shar) determine whether the platform provides transparent and configurable mechanisms for distributing collective benefits and costs within the REC. It focuses on how energy, financial savings, and operational costs are allocated among members based on predefined or dynamic sharing rules.

2.2.4. Environmental

The environmental (ENVIR) [26] KPI dimension evaluates the platform’s capability to quantify, monitor, and optimize the environmental performance of RECs. Its purpose is twofold: first, to assess what environmental impacts are measured, focusing on robust and transparent carbon accounting; and second, to examine how these metrics influence decision-making through the integration of environmental objectives or constraints into system design and operational optimization.

The ‘Carbon accounting’ (ENVIR_carb) sub-criterion verifies whether the tool quantifies greenhouse-gas impacts of REC designs/operations with sufficient temporal and geographic resolution.

Environmental objective support (ENVIR_obj) assesses whether environmental performance is treated as a first-class decision driver. Mature tools embed emissions (or emission intensity) as a design/operation objective alongside cost and reliability, or as binding constraints. This enables transparent trade-off analysis and policy-aligned planning.

2.2.5. Social

This KPI dimension evaluates how effectively the platform supports transparent participation, communication, and decision-making within the REC [37]. It focuses on whether members have clear visibility of data, results, and impacts, as well as access to interactive tools or dashboards that promote understanding and engagement. The dimension also examines the presence of mechanisms for capturing member preferences, feedback, and co-design inputs, ensuring that community decisions reflect user priorities rather than purely technical optimization. Additionally, it considers whether the platform provides built-in guidance, tutorials, or simplified interfaces that help users participate meaningfully without requiring advanced technical skills.

The ‘Member portals and transparency dashboards’ sub-criterion (SOC_trans) addresses user-facing transparency. It evaluates how clearly the platform communicates energy, financial, and environmental data to community members through dashboards, portals, and reports. This criterion focuses on member-level visibility and trust, ensuring that users can understand and verify community performance and decision-making outcomes.

The ‘Co-design features’ (SOC_des) sub-criterion assesses the platform’s capability to actively involve community members in planning, decision-making, and operational processes through participatory design functionalities.

The ‘Education’ (SOC_educ) sub-criterion evaluates the platform’s ability to educate, guide, and support users—both community members and administrators—through a combination of integrated assistance tools and external documentation. It measures how effectively the platform lowers technical barriers and ensures that users can understand, operate, and expand the system confidently.

2.2.6. Quality Indicators

The ‘Quality indicators’ (QUAL) KPI dimension evaluates the overall maturity, robustness, and user-readiness of the platform supporting RECs. It focuses on how well the tool performs in practical implementation, ensuring reliability, usability, and long-term sustainability [38]. The dimension consists of six sub-criteria described below.

The ‘Usability’ (QUAL_us) sub-criterion assesses how intuitive and user-friendly the platform interface is for different user groups (e.g., administrators, members, operators). Tools that offer multilingual interfaces, contextual help, and user-tailored dashboards demonstrate enhanced usability.

The ‘Reliability and performance’ (QUAL_perf) sub-criterion evaluates the platform’s technical robustness, responsiveness, and stability under different operational conditions. It includes aspects such as system uptime, error handling, data integrity, and computational efficiency. Tools that maintain consistent performance during peak data loads or simulation runs, and that provide redundancy and backup mechanisms, score higher.

The ‘Openness’ (QUAL_open) sub-criterion refers to the technical and architectural openness of the platform. It evaluates whether the system provides open-source access, transparent algorithms, well-documented application programming interfaces, and compliance with interoperability standards. The focus is on developer- and integrator-level transparency—ensuring reproducibility, interoperability, and long-term vendor independence.

2.3. KPI Calculation and Tool Evaluation

In this study, each sub-criterion is scored on a three-level scale 0/0.5/1, where 0 denotes no support (or no verifiable evidence), 0.5 denotes partial support, and 1 denotes full support with documented/demonstrated evidence.

The dimension-average KPI score for tool i is computed as the arithmetic mean over its sub-criteria [23]:

where d is the dimension label (d ∈ {TECH, OPER, ECON, ENVIR, SOC, QUAL}); nd is the total amount of sub-criteria of dimension d; j is the index of the sub-criterion within dimension d (j ∈ {1, …, nd}); i is the index of the tool (i ∈ {1, …, I}); is the sub-criterion score for dimension d of i-th tool on sub-criterion j, ({0; 0.5; 1}). Descriptions of the scoring levels for every sub-criterion in each dimension are provided in Appendix A.

To compute the overall performance score Si for the i-th evaluated platform, the WSM [39,40] is applied. This model aggregates the normalized performance scores from each of the six defined KPI dimensions, according to their assigned weight coefficients wd:

where is the weight of dimension d, and .

2.4. Determination of Weight Coefficients

In this review, the authors have employed four well-established approaches to determine the weighting coefficients [41] wd for the six offered KPI dimensions: rank order centroid (ROC) [42,43] analytic hierarchy process (AHP, pairwise comparisons) [44,45,46], entropy weight method (EWM) [47] and the criteria importance through intercriteria correlation (CRITIC) [48]. These methods were chosen for their reproducibility, transparency, and firm grounding in MCDA literature [49]. The ROC and AHP approaches use the authors’ expert judgment in a structured manner, while EWM and CRITIC derive weights objectively from the variability and correlation of the data. All four methods produce a normalized weight vector (summing to 1), which is then used to weight each dimension’s contribution in the overall performance evaluation by the WSM model. A comparative analysis of different weight sets is provided in Section 3.

2.4.1. ROC

In this case, the ROC method serves as a transparent, non-compensatory weighting approach suitable in the absence of stakeholder-derived numerical weights. It relies on the assumption that decision-makers (here, the authors) can establish a rank order of KPI dimension importance (from 1 to 6), even if they cannot specify precise magnitudes of difference between them.

To determine the final ranking, the authors agreed to use the average rank method, which is widely applied in multi-criteria analysis. The formula for calculating the average rank for each criterion is as follows [50]:

where is the average rank of criterion ; is the rank assigned to criterion by author ; Auth is the number of authors.

In expression (4), denotes the weight assigned to the th dimension by the ROC method [42]:

The variable is the total number of KPI dimensions, and is the rank of the th dimension (with for the highest-ranked dimension and for the lowest). The summation index runs from to , so sums the reciprocals of the integers from through . Dividing this sum by normalizes the weights so that all weights sum to one. Thus, a higher-ranked dimension (smaller ) has more terms in the sum and therefore receives a larger , reflecting its relatively greater importance.

2.4.2. AHP

In this case, AHP was applied as a structured expert judgement method in the absence of stakeholder surveys. The research team constructed a 6 × 6 reciprocal pairwise comparison matrix A, covering the six KPI dimensions, using a simplified Saaty scale [51]. Each matrix element reflects the perceived importance of dimension d relative to dimension r. The matrix is reciprocal: add = 1 (for all diagonal elements), adr = 1/ard (when d ≠ r).

The resulting pairwise comparison matrix has the following form:

where A is the pairwise comparison matrix of the dimensions.

The weight coefficient by the AHP method is calculated as follows [44]:

where adr indicates how much more important dimension d is compared to dimension r; is geometric mean of row d; index d denotes the row corresponding to the dimension whose weight is being calculated; k is the row index in the normalisation term ; r is the column index used in the product to compute the geometric mean of row d.

2.4.3. EWM

The fundamental idea of EWM [52] is that a dimension provides more decision-making value if its values are more dispersed (less uncertain or more informative). Conversely, dimensions with uniformly distributed scores are considered less informative and are therefore assigned lower weights. Since it uses only data (no expert judgements), EWM was selected to cross-check subjective schemes (ROC and AHP) in hybrid weighting.

The normalized weight for each KPI dimension by EWM is evaluated as follows [53]:

where k is an auxiliary index, k ∈ {1, …, C}; is the divergence of each dimension d and computes as:

where Ed is the entropy of dimension d. Dimensions with a higher divergence are considered more informative.

The entropy is defined as follows:

where represents the normalized proportion of the performance of tool i on KPI dimension d, relative to all other tools for that dimension; I is the total number of tools.

Expression (9) is bounded in [0, 1], where Ed = 1 implies a uniform distribution (low discriminating power) and Ed = 0 implies high contrast (high information content).

The normalized proportion of the performance of tool i on KPI dimension d is calculated as follows:

where ε is a small positive constant (in this case, ε = 10–12) to prevent division by zero. This normalization ensures , mimicking a probability distribution over tools for each dimension.

Entropy captures the contrast intensity or information richness of each criterion. The greater the dispersion of data, the higher the criterion’s ability to distinguish alternatives, and thus the higher its assigned weight. As a result, EWM tends to assign the highest weights to criteria that best differentiate the performance of alternatives—those that contain the most ‘information’ about the decision space.

2.4.4. CRITIC

The CRITIC method [48] is another objective approach that assigns weights by considering both the contrast intensity (standard deviation) and conflict (correlation) among criteria. It emphasizes criteria that vary strongly and are less correlated with others.

The weight for each KPI dimension by CRITIC is evaluated as follows:

where is the information content (contrast intensity) of dimension d; is the information content of dimension k.

The parameter is calculated as follows:

where is the standard deviation of dimension d; ρdk is the Pearson correlation [54] between dimensions d and k. The correlation analysis between dimensions is calculated by vector .

is evaluated by Equation (13):

where

The Pearson correlation between dimensions is estimated as:

3. Results

3.1. Overview of the Selected EMTs

The objective of this section is to present and interpret the comparative results of the evaluated software tools across the six defined KPI dimensions. Each tool was assessed based on its performance across 23 sub-criteria spanning technical, operational, economic, environmental, social, and quality-related dimensions. The scoring followed the normalized 0/0.5/1 scale described earlier, enabling consistent comparison and aggregation across functionally diverse tools.

Based on the defined selection criteria, Table 1 provides an overview of the selected software tools, including their primary goals, applicable spatial scale, and scope. The tools’ focus areas range from microgrid dispatch optimization to municipal-scale REC planning, reflecting the diversity of functionalities and use cases relevant to community energy systems.

Table 1.

Overview of the selected EMTs for EC assessment, considering the main aim of the software, scale and scope, availability, integration with other software, simulation type, reference studies in which the tool is considered.

The tools span a broad spatial spectrum—from individual households and microgrids (e.g., MiGRIDS Lite, OpenEnergyMonitor) to municipal and district-level communities (e.g., LocalRES, eNeuron), and even national or cross-border implementations (e.g., Powerledger, Energy Web, REScoopVPP). Several tools, such as OpenEMS or Hive Power FLEXO, explicitly support scalability from small communities to industrial or grid-level integration. Tools such as eNeuron, LocalRES, and Cleanwatts emphasize multi-vector optimisation (electricity, heat, mobility), while others like Powerledger and Energy Web focus on market mechanisms, trading, and blockchain infrastructure. Tools like GreenPocket and REScoop Energy Community Platform emphasize community engagement, transparency, and governance, while Rectool and PROCSIM focus on planning and dataset-based modelling.

3.2. Results by Methodological Step

This section presents the outcomes of the KPI-based evaluation following the sequence of methodological steps defined in the assessment framework. Each step reflects a specific stage of the analysis—from KPI definition and ranking of sub-criteria scoring, KPI dimension weighting, to the final evaluation of each tool.

3.3. KPI Results

According to Equation (1), the dimension-average KPI score for each tool is computed. Results of the scoring levels for every sub-criterion in each dimension are provided in Appendix B, Appendix C and Appendix D. The results of KPI scores for each considered tool are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Average KPIs of the tools.

Table 2 presents a heatmap of average KPI scores across six evaluation dimensions for each assessed tool. Warmer colours indicate lower scores, while cooler colours highlight stronger performance.

The heatmap reveals that some tools—such as eNeuron, (+)CityxChange, Cleanwatts, Hive Power FLEXO, and Powerledger—exhibit consistently high values across all KPI categories. These platforms combine strong technical capabilities, sustainability features, and user adoption, making them well-balanced solutions for integrated REC applications.

Other tools, such as BECoop, MiGRIDS Lite, LocalRES, and PROCSIM, show high scores in only one or two categories while scoring low elsewhere. This suggests functional specialization and alignment with narrower use cases rather than comprehensive energy community support.

Meanwhile, platforms like OpenEMS, REScoopVPP, and Energy Web display more uneven performance, excelling in specific technical or infrastructure areas but lacking strength across all KPI dimensions. These patterns underscore the importance of matching tools to the intended scope and priorities of each REC initiative.

3.4. Ranking of KPI Dimension

In this paper, all authors independently proposed their rankings for six evaluation criteria that are essential for decision-making in the studied context. Each author assigned ranks from 1 (most important) to 6 (least important). The purpose of this stage was to consolidate these individual rankings into a unified order of importance, which would later serve as the basis for calculating weight coefficients for each criterion. According to the methodology described in Section 2.1., to determine the final ranking, the authors agreed to use the average rank method, which is widely applied in multi-criteria analysis. The collected data and the results of the consolidation method are summarized in Table 3 below.

Table 3.

Rankings of each KPI criterion by author.

By applying a transparent mathematical approach, the team ensured that the final ranking reflects the collective expertise of all contributors.

3.5. Results of Weight Coefficients

The final results of all the weight calculations, based on Section 2, are presented in Table 4. A 6 × 6 reciprocal comparison matrix constructed by the AHP method is shown in Appendix E.

Table 4.

Weight coefficients by the ROC, AHP, EWM and CRITIC methods.

In the EWM and CRITIC objective weighting methods, the input dataset is the I × C matrix X = of the dimension-average KPI scores defined in Section 2.3. Each element of this matrix is the aggregated score of a given tool on a given KPI dimension, obtained by averaging the tool’s sub-criterion scores in that dimension. EWM uses this matrix to compute entropy-based variability for each dimension, while CRITIC derives standard deviations and Pearson correlations from the same matrix to quantify contrast intensity and inter-dimension conflict.

The sum of the weight coefficients assigned to all KPI dimensions equals 1.0 for each of the four methods, confirming that the normalization was performed correctly, and that each method maintains a valid weight distribution across all the evaluated criteria.

Table 4 demonstrates that the ROC weights align with the established priorities. The TECH and OPER dimensions have the highest weights—0.4083 and 0.2417 respectively—confirming their critical role in the decision-making framework. Mid-ranked dimensions such as QUAL (0.1583) and ECON (0.1028) add moderate value, whereas SOC (0.0611) and ENVIR (0.0278) contribute less. This spread shows a clear focus on technical and operational factors, while environmental and social considerations, though included, have a less pronounced effect on the total performance score.

The AHP weights closely follow the consolidated ranking, with TECH (0.3735) and OPER (0.2545) emerging as the most influential dimensions. QUAL (0.1620) and ECON (0.1021) occupy intermediate positions, whereas SOC (0.0650) and ENVIR (0.0430) remain the least significant ones. This distribution confirms the strong emphasis on technical and operational dimensions, while still incorporating qualitative and sustainability considerations into the decision-making framework.

EWM produced a distribution that differs significantly from that of expert-based methods. ENVIR (0.3386) and ECON (0.2369) emerged as the most influential criteria due to their high variability, whereas TECH (0.1328) and OPER (0.1262) received moderate weights. SOC (0.1040) and QUAL (0.0614) contributed the least. This outcome highlights the value of incorporating data-driven weighting to complement subjective assessments and strengthen the robustness of the overall evaluation.

The last method, CRITIC, produced a criterion with a high variability and low correlation. ENVIR (0.2046) and SOC (0.1811) emerged as the most influential ones, reflecting their distinctive informational contribution. OPER (0.1643) and QUAL (0.1591) received moderate weights, while ECON (0.1536) and TECH (0.1373) were the least significant ones. This outcome demonstrates how CRITIC complements other methods by highlighting criteria that reduce redundancy and enhance the robustness of the overall evaluation.

The ROC and AHP methods pointed to TECH and OPER as the top priorities. That pretty much matches what the authors had already thought was important. The EWM and CRITIC methods work a bit differently since they base their weights on the data itself and are data-driven techniques. These methods identified the ENVIR and ECON domains as the most significant ones, emphasizing the role of environmental and economic variability in the dataset. This really puts the spotlight on how much environmental and economic data can shift the results.

The differences between the weighting methods reveal that ROC and AHP reflect broader strategic or expert-defined priorities, while EWM and CRITIC uncover insights rooted in the intrinsic patterns and variability of the data.

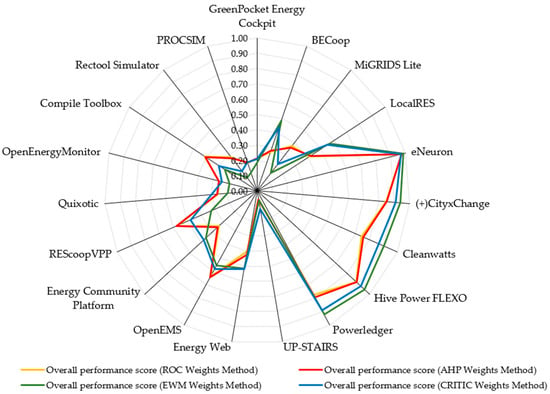

3.6. Results of Final Score

Figure 3 represents the overall performance scores of the tools under four different weighting methods. Each line traces the normalized KPI score for a tool under one weighting scheme, allowing for a direct visual comparison across methods (see Equation (2)). This figure highlights how the choice of weighting approach—expert-based or data-driven—influences the relative assessment of each tool. Numeric results are available in Appendix F.

Figure 3.

The overall performance scores of the tools.

Tools such as eNeuron, CityxChange, Cleanwatts, Hive Power FLEXO and Powerledger consistently achieve the highest scores using all four weighting schemes. This indicates that these tools deliver balanced performance across technical, operational, economic, and sustainability criteria, regardless of the weight approach.

While the overall ranking of leading tools remains stable, differences appear in mid- and low-performing tools. For example, BECoop, MiGRIDS Lite, REScoopVPP, Compile Toolbox and Rectool Simulator show noticeable variation between ROC and AHP methods and data-driven methods (EWM, CRITIC). This suggests that expert judgment emphasizes technical and operational aspects, whereas objective methods highlight variability in environmental and economic indicators. ROC and AHP consistently assign greater weight to technical and operational KPIs, resulting in higher scores for tools with strong engineering and control capabilities.

Under the EWM and CRITIC methods, tools with strong environmental and economic performance—such as (+)CityxChange, Cleanwatts, Powerledger, Energy Web and LocalRES—gain a relative advantage compared to expert-based weighting. This is because the environmental and economic criteria show higher variation across tools and are less correlated with other dimensions. As a result, the objective methods assign them more weight, which amplifies the scores of tools that perform well in these areas.

3.7. Real-World Applications of REC Tools

To support the practical relevance of the proposed evaluation framework, the authors briefly summarize three real-world implementations of tools included in the assessment.

3.7.1. Powerledger and Decentralized Market Mechanisms

The quantitative results underscore that platforms excelling in the ECON dimension (specifically the Benefit-sharing calculators, ECON_shar), and QUAL dimension (particularly Openness, QUAL_open), often integrate sophisticated market mechanisms that enforce transparency and fairness. This finding is empirically validated by the deployment of Powerledger, a tool evaluated within this framework. Powerledger leverages blockchain technology to facilitate peer-to-peer energy trading, moving beyond static optimization calculations to dynamic, market-driven energy allocation [91]. In demonstrations such as the Brooklyn Microgrid project and various deployments across Australia and Southeast Asia, the platform utilizes a dual token model (e.g., POWR, Sparkz) to allow residential and commercial participants to transparently share and transact their energy surplus at mutually desired prices [69,91].

This practical implementation directly addresses the sub-criterion of ECON_shar by providing an auditable, decentralized ledger for transactional settlements. The use of blockchain technology inherently reinforces the QUAL_open criterion, establishing a trust layer necessary for scaling community participation, which often presents a major barrier in traditional centralized energy systems. Thus, the high scoring of Powerledger in these domains is justified by its capacity to enable the scalability of trust and financial transparency through the distributed ledger technology.

3.7.2. +CityxChange and Participatory Planning for Positive Energy Blocks

The evaluation framework’s prioritization of SOC criteria is validated by large-scale EU demonstration projects focusing on co-creation, such as the +CityxChange initiative, which aims to develop positive energy blocks in urban environments [62].

While technical optimization is often a primary design goal, the +CityxChange project explicitly demonstrates that successful REC implementation requires digital platforms that actively facilitate co-design features (SOC_des) and effective member portals and transparency dashboards (SOC_trans). This platform is designed to enable citizen participation, transforming energy consumers into active prosumers and ‘positive energy champions’ through integrated physical and digital engagement strategies. This intentional focus ensures that technical optimizations are aligned with community preferences and behaviors.

The +CityxChange model confirms that achieving high performance ENVIR goals, such as carbon reduction for PEBs, is dependent on strong performance in the SOC dimension. The SOC_des participatory framework acts as the necessary mediation layer, converting purely technical goals into achievable behavioral outcomes within the community [64].

3.7.3. Cleanwatts Kiplo and Automated Operational Control

The consistent robustness of top-ranked platforms in the Operational (OPER) domain is driven by their capacity to manage multi-asset environments and respond dynamically to grid needs, as demonstrated by the Cleanwatts Kiplo STEP (Smart Transactive Energy Platform) [64]. Kiplo is implemented as a commercial, end-to-end management system designed to automate the coordination of diverse assets, including PV, BESS, and EV chargers, to maximize local self-consumption while ensuring regulatory compliance. Kiplo has implemented its community energy platform in Miranda do Douro, Portugal—the country’s first REC under the new RED II framework. The platform excels in demand response and flexibility aggregation (OPER_flex) by connecting local energy markets to multi-layered upstream markets. This feature allows the REC to monetize small-load flexibility while adhering to existing physical, legal, and regulatory barriers and frameworks.

This deployment provides a concrete validation of how tools can successfully execute complex EV management (OPER_EV) strategies, optimizing charging schedules against dynamic price signals and renewable energy forecasts [66]. The ability of the platform to maintain automated, compliant coordination reveals that such tools are evolving from simple optimization engines into regulatory enabling infrastructure (OPER/ECON). This functionality is crucial for achieving high scores in operational readiness and addresses the policy challenge of integrating decentralized flexibility into centralized grids, while assuring system security.

4. Discussion

This paper presents a structured KPI–MCDA evaluation of digital tools supporting RECs, aiming to close existing gaps in platform assessment methodologies. Previous literature has primarily focused on technical and economic functionalities, often omitting critical aspects such as user engagement, regulatory adaptability, EV implementation or platform usability. The results confirm that while several tools perform well across multiple functional dimensions, many others show strong performance in only a narrow set of criteria, which limits their broader applicability in real-world community contexts.

During the analysis, several methodological and practical considerations emerged that shaped the final approach and should be considered when interpreting the results. Firstly, the selection of the pairwise comparison scale for the AHP component required careful deliberation. The authors evaluated two options: the discrete odd-number scale commonly used in AHP (e.g., 1, 3, 5) and broader ranges such as 1–5 or 1–9, as proposed in classical AHP literature. While a 1–9 scale offers granularity, empirical observations indicated that the perceived differences in criterion importance across tools were moderate rather than extreme. Therefore, to avoid overstating the influence of marginal differences, the authors opted for a limited 1–5 scale. This compromise balances methodological rigour with real-world interpretability and reflects the underlying distribution of expert judgment. Another practical issue concerned the uniqueness of pairwise ratings. After internal deliberation, the authors concluded that permitting repeated scores across criteria was more realistic. In real-world settings, multiple criteria may be viewed as equally important, and forcing strict ordinal rankings could misrepresent true expert preferences. Allowing repeated values helped retain the semantic integrity of expert assessments and avoided introducing artificial precision into the weighting model. Recognizing the inherent subjectivity of expert-derived weights, the authors further triangulated results using two objective, data-driven methods: EWM and CRITIC. These methods rely solely on the observed variability and correlation within the data and offer complementary perspectives.

If considering the ranking results from the perspective of commercial versus open-source tools, it becomes evident that separating these categories is unnecessary. Both types of solutions exhibit strengths and weaknesses depending on the weighting method and performance criteria. Commercial tools such as Cleanwatts and Powerledger achieve high scores under the EWM and CRITIC methods, indicating strong performance under data-driven or variability-sensitive criteria. Meanwhile, open-source tools like OpenEMS and OpenEnergyMonitor perform competitively under weighting schemes such as ROC or AHP, showing that open-source solutions can also excel when expert-based or rank-based weighting is applied. The table also shows instances where commercial and open-source tools achieve very similar performance scores—for example, GreenPocket Energy Cockpit (commercial) and OpenEnergyMonitor (open source) under the AHP method—indicating that neither category is inherently superior across all evaluation dimensions.

For smaller-scale, household-level tools focused on technical control, expert-derived weighting methods like ROC and AHP (which place the greatest importance on technical and operational criteria) tend to favor these platforms. Under ROC/AHP weightings, tools with strong engineering and control capabilities achieve higher overall scores, reflecting how expert judgment emphasizes technical performance. In contrast, community-level planning tools and larger district-scale platforms oriented toward market integration gain an edge under objective data-driven methods, EWM and CRITIC, which assign greater weight to environmental and economic criteria. These entropy- and correlation-based weightings amplify the scores of tools excelling in sustainability or market-trading features, since those dimensions exhibit higher variability across the tool set. Consequently, the impact of each weighting scheme is scope-dependent: expert-based weights benefit technology-centric solutions at the household/microgrid scale, whereas objective methods highlight platforms aligned with broader community and market goals. Notably, the most well-rounded tools such as eNeuron, CityxChange, Cleanwatts, deliver balanced performance across all criteria and thus rank highly under every weighting approach. This underscores that comprehensive, multi-domain design ensures a tool remains a top performer regardless of whether the evaluation emphasizes technical control or community-focused sustainability priorities.

The authors intend to explore this balance further in future work, focusing on how different combinations of platform functionalities—such as real-time flexibility control, co-design interfaces, and environmental optimization—can be integrated into scalable, user-friendly digital infrastructures. Particular attention will be paid to the role of interoperability standards, open-source architectures, and modular design in enhancing platform adaptability across diverse regulatory contexts. Additionally, future studies will investigate the incorporation of user feedback and empirical testing to refine the scoring framework and better align platform evaluation with the lived experiences of REC stakeholders.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study provide valuable insights that extend beyond the numerical rankings of the evaluated platforms. The consistent top performance of eNeuron, (+)CityxChange, Cleanwatts, Hive Power FLEXO, and Powerledger across all weighting schemes does not reflect a methodological coincidence but rather the robustness and comprehensiveness of their design. These platforms simultaneously address technical, operational, economic, environmental, social, and quality domains, demonstrating that balanced multi-domain integration, rather than specialization in one area, determines overall excellence in the multi-criteria evaluation context. Meanwhile, the variability observed among mid-ranked platforms such as BECoop, MiGRIDS Lite, REScoopVPP, Rectool, and PROCSIM under different weighting scenarios reveals that the relevance and performance of each tool are highly dependent on stakeholder priorities. This indicates that platform suitability is contextual and should align with whether a project is primarily technology-driven or community-oriented. A review of the results also shows that the distinction between commercial and open-source tools does not translate into systematic performance differences. High and low scores appear in both categories depending on the weighting approach.

From a practical perspective, the findings suggest that the selection of tools should be guided by project-specific objectives rather than overall ranking. For ECs that prioritise operational control, flexibility, and integration of EV or demand response, tools with strong operational capabilities are more appropriate. Conversely, initiatives focusing on early-stage design and planning would benefit from tools that demonstrate superior capability in feasibility and spatial analysis. The six KPI dimensions proposed in this study can serve as a comprehensive framework for structuring technical specifications, procurement processes, and evaluation protocols, helping to prevent the omission of critical functionalities such as network constraint modelling, energy-sharing mechanisms, or multi-objective optimisation. In addition, the analysis underscores the importance of modularity and interoperability: while universal tools can serve as a system’s core, the integration of specialised solutions through open interfaces and scalable architectures can improve overall system performance and adaptability.

At the policy level, the results highlight the need to embed environmental and economic sharing dimensions in national and regional regulatory frameworks. Since the rankings are most sensitive to these domains under data-driven weighting schemes, policymakers should consider incorporating requirements for carbon accounting, transparent benefit allocation, and lifecycle performance tracking into public funding programmes and pilot project evaluations. Establishing a baseline set of functional requirements for REC digital tools—covering grid constraint modelling, flexibility management, multi-objective optimisation, and user transparency—would reduce fragmentation among projects and ensure interoperability across different governance levels. Furthermore, the use of publicly available KPI reporting and disclosure of weighting schemes would enhance comparability and accountability across municipal and community-led initiatives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: L.P. and A.M.; methodology: L.P., S.H. and I.D.; software: S.H. and L.P.; validation: R.Z. and P.N.; formal analysis: L.P., S.H., R.Z. and P.N.; investigation: R.Z., S.H. and P.N.; resources: L.P. and I.D.; writing—original draft preparation: L.P., S.H., R.Z. and P.N.; writing—review and editing: L.P. and A.M.; visualization: S.H.; supervision: A.M.; project administration: A.M.; funding acquisition: L.P. and A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research conducted in this publication was funded by the Latvian Council of Science for the project LV_UA/2025/2 and by the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine under the grant number 0125U002848 ‘Development of an open-source tool to support energy communities with electric vehicles and battery energy storage’.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

| Sub-Criteria | Sub-Criterion Score | ||

| x = 0 | x = 0.5 | x = 1 | |

| TECH_vec | Single vector only | Two vectors | Three or more vectors with explicit couplings |

| TECH_opt | No optimizer (scenario calculation only) | Single-objective optimization | Multi-objective optimization or equivalent explicit trade-off exploration |

| TECH_Sim | Aggregate/static or seasonal snapshot calculations without continuous time-series | Hourly time-series over representative periods or full year with limited sub-hourly support | Full-year time-series with optional sub-hourly steps, consistent multi-vector balance, and documented numerical/validation details. |

| TECH_forec | No built-in forecasting | Built-in forecasting for at least one stream (e.g., PV or load) or automated import from external services without accuracy reporting | Configurable multi-stream forecasting (load and RES at minimum) with documented methods, horizon/cadence control, and accuracy/confidence reporting. |

| TECH_spat | Non-spatial, aggregate inputs only | Basic GIS support (layer import, georeferencing of assets) | Advanced spatial analytics (3D/shading, geoprocessing queries, perimeter/network checks) |

| TECH_grid | Single-bus balance without grid representation | Simplified treatment (aggregate losses or transformer caps) | Explicit LV/MV network model with power-flow and constraint checking |

| ECON_fin | Costs only | Some KPIs (e.g., LCOE and payback) but not the full set or without transparent assumptions | Full KPI set (NPV, LCOE, IRR, payback) with parameterized assumptions and clear reporting |

| ECON_tar | Single flat tariff only | Multiple static/TOU tariffs or limited dynamic import | Native dynamic pricing support and per-member/asset tariff assignment with different tariff set scenarios. |

| ECON_sens | No built-in sensitivity | Manual/scenario-by-scenario variation with limited aggregation | Integrated batch sensitivity or stochastic analysis with summarized robustness metrics |

| ECON_shar | No explicit sharing logic (manual spreadsheets required) | Single or hard-coded scheme with limited configurability | Multiple configurable schemes (including dynamic allocation) with transparent statements and exports |

| ENVIR_carb | No emission quantification or only static, generic emission factors without transparency or time resolution | Basic carbon accounting is implemented using national or annual average factors, with limited spatial or temporal granularity | Comprehensive carbon accounting framework with high-resolution (hourly or regional) emission factors, transparent methodology, and automatic tracking of emissions across scenarios or operational periods |

| ENVIR_obj | Environmental indicators are reported only as outputs; no influence on design, control, or optimisation decisions | Environmental parameters (e.g., CO2 intensity, renewable share) can be used qualitatively or as secondary evaluation metrics but not directly optimised or constrained | Environmental performance explicitly incorporated as an optimisation objective or constraint (e.g., CO2 minimisation, renewable penetration target, emission caps), with capability for trade-off and scenario analysis |

| SOC_trans | No member-facing interface or dashboards; information is only accessible to administrators | Basic dashboards with limited visibility (e.g., simple energy or cost summaries without detailed breakdowns or role differentiation) | Comprehensive, role-based member portal with detailed visualisation of energy, cost, and environmental data; includes data export, report generation, and transparency features that support trust and engagement |

| SOC_des | No participatory or feedback mechanisms; community members have no structured way to provide input | Basic feedback options (e.g., static survey or manual preference collection) without integration into platform logic or scenario design | Fully integrated co-design environment with interactive tools (surveys, voting, preference inputs) and feedback loops that directly influence planning, optimisation, or governance decisions. |

| SOC_educ | No built-in help, onboarding, or external documentation; users must rely on ad hoc support | Basic user manual or FAQ provided; limited contextual help or outdated documentation | Comprehensive learning ecosystem combining interactive onboarding, contextual help, structured documentation (user & developer), and online training resources ensuring accessibility for all user types |

| OPER_ascl | The platform supports only a single or very limited asset type (e.g., PV monitoring only) with no control or interoperability functions | Multiple asset types are represented but with limited depth (e.g., monitoring without control or lack of standardized integration) | Wide range of controllable and observable assets supported natively, with full data integration, real-time control capability, and interoperability across multiple device classes |

| OPER_analyt | No analytical or reporting functionality beyond raw data logs | Basic analytics and standard KPI visualisation (e.g., daily/weekly summaries) | Advanced analytics with predictive/prescriptive functions, automated KPI tracking, and multi-user report generation |

| OPER_flex | No flexibility or demand response capabilities; assets operate independently | Basic manual or schedule-based flexibility activation; limited to a single asset class (e.g., batteries or EVs) | Full flexibility aggregation with automated event handling, forecasting, multi-asset coordination (including EVs), and verification of delivery |

| OPER_EV | Absence of EV-specific functionality beyond manual metering/logging | Support for imported charging schedules or basic rule-based charging, without optimization against price/RES signals and without explicit handling of network constraints | Integrated, policy-based smart charging with optimization against dynamic prices and RES forecasts, explicit enforcement of network/connection constraints, and provision of monitoring and compliance logs |

| QUAL_us | Complex, unintuitive interface requiring expert-level knowledge; no guidance or accessibility support | Moderately usable interface with partial structure and limited contextual help | Highly intuitive, user-centred design with clear workflows, multilingual support, and built-in interactive guidance |

| QUAL_perf | Platform exhibits frequent errors, crashes, or data inconsistencies; performance degrades significantly under normal load | Platform operates reliably under standard conditions but shows occasional instability or slow performance under heavy computation or large datasets | Platform demonstrates high reliability and computational performance with stable uptime, efficient resource management, and proven resilience during intensive simulations or multi-user operation |

| QUAL_open | Closed-source platform with proprietary data models and no public documentation or APIs | Partially open system (e.g., documented APIs or selected modules available) with limited transparency | Fully open or transparent ecosystem: open-source code, public API documentation, open data models, and community-driven development |

Appendix B

| KPI/Tools/Tool | GreenPocket Energy Cockpit | BECoop | MiGRIDS Lite | LocalRES | eNeuron | (+)CityxChange | Cleanwatts | Energy Web |

| Technical | ||||||||

| Energy vector | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Simulation capability | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Forecasting | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Optimization | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Spatial/GIS | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 |

| LV/MV grid constraints & losses | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Operational | ||||||||

| Asset classes | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| EV management | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Analytics and reporting | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Demand response/flexibility aggregation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Economic | ||||||||

| Financial KPIs | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 |

| Tariff/market models | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Sensitivity | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 |

| Benefit-sharing calculators | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 |

| Environmental | ||||||||

| Carbon accounting | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Environmental objectives | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Social | ||||||||

| Member portals & transparency | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Co-design features | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 |

| Education | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Quality and Adoption | ||||||||

| Usability | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Reliability and performance | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Openness | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 |

Appendix C

| KPI/Tools/Tool | OpenEMS | Hive Power FLEXO | Powerledger | UP-STAIRS | Energy Community Platform | Rectool Simulator | Procsim |

| Technical | |||||||

| Energy vector | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Simulation capability | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Forecasting | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Optimization | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Spatial/GIS | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| LV/MV grid constraints & losses | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Operational | |||||||

| Asset classes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| EV management | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Analytics and reporting | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Demand response/flexibility aggregation | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Economic | |||||||

| Financial KPIs | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Tariff/market models | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Sensitivity | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 |

| Benefit-sharing calculators | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Environmental | |||||||

| Carbon accounting | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Environmental objectives | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Social | |||||||

| Member portals & transparency | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Co-design features | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Education | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 |

| Quality and Adoption | |||||||

| Usability | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Reliability and performance | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 |

| Openness | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Appendix D

| KPI/Tools/Tool | Compile Toolbox/ComPilot & Related Tools | REScoopVPP | Quixotic | OpenEnergyMonitor |

| Technical | ||||

| Energy vector | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 |

| Simulation capability | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 |

| Forecasting | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 |

| Optimization | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Spatial/GIS | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| LV/MV grid constraints & losses | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Operational | ||||

| Asset classes | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 |

| EV management | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Analytics and reporting | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Demand response/flexibility aggregation | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Economic | ||||

| Financial KPIs | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tariff/market models | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Sensitivity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Benefit-sharing calculators | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Environmental | ||||

| Carbon accounting | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Environmental objectives | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Social | ||||

| Member portals & transparency | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Co-design features | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 |

| Education | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Quality and Adoption | ||||

| Usability | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Reliability and performance | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 |

| Openness | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.5 |

Appendix E

| TECH | OPER | QUAL | ECON | SOC | ENVIR | |

| TECH | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| OPER | 1/2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| QUAL | 1/3 | 1/2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| ECON | 1/4 | 1/3 | 1/2 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| SOC | 1/5 | 1/4 | 1/3 | 1/2 | 1 | 2 |

| ENVIR | 1/6 | 1/5 | 1/4 | 1/3 | 1/2 | 1 |

Appendix F

| Tool/Weighting Methods | Total KPI Values Before Weighting | Overall Performance Score (ROC Weights Method) | Overall Performance Score (AHP Weights Method) | Overall Performance Score (EWM Weights Method) | Overall Performance Score (CRITIC Weights Method) |

| GreenPocket Energy Cockpit | 1.2917 | 0.2138 | 0.2128 | 0.1871 | 0.2087 |

| BECoop | 2.5000 | 0.2690 | 0.2769 | 0.4834 | 0.4392 |

| MiGRIDS Lite | 1.4167 | 0.3701 | 0.3584 | 0.1477 | 0.2218 |

| LocalRES | 3.0833 | 0.4063 | 0.4179 | 0.5646 | 0.5481 |

| eNeuron | 5.8333 | 0.9736 | 0.9731 | 0.9872 | 0.9713 |

| (+)CityxChange | 5.4167 | 0.8452 | 0.8527 | 0.9417 | 0.9100 |

| Cleanwatts | 5.1250 | 0.7469 | 0.7587 | 0.9044 | 0.8673 |

| Hive Power FLEXO | 5.5000 | 0.8792 | 0.8839 | 0.9526 | 0.9209 |

| Powerledger | 5.2500 | 0.7771 | 0.7905 | 0.9199 | 0.8882 |

| UP-STAIRS | 0.6667 | 0.0569 | 0.0595 | 0.0640 | 0.1197 |

| Energy Web | 2.9583 | 0.4018 | 0.4251 | 0.5171 | 0.5210 |

| OpenEMS | 3.5000 | 0.6371 | 0.6435 | 0.5578 | 0.5819 |

| Energy Community Platform | 2.7500 | 0.3400 | 0.3498 | 0.4553 | 0.4737 |

| REScoopVPP | 2.8750 | 0.5709 | 0.5742 | 0.3272 | 0.4763 |

| Quixotic | 1.7500 | 0.2574 | 0.2637 | 0.1932 | 0.2996 |

| OpenEnergyMonitor | 1.4583 | 0.2575 | 0.2589 | 0.1863 | 0.2397 |

| Compile Toolbox | 1.8750 | 0.4115 | 0.4038 | 0.2523 | 0.2980 |

| Rectool Simulator | 1.0417 | 0.2795 | 0.2684 | 0.1084 | 0.1613 |

| PROCSIM | 1.1667 | 0.1928 | 0.1945 | 0.1239 | 0.1954 |

References