Composite Modified Clay Mineral Integrated with Microbial Active Components for Restoration of Black-Odorous Water

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Modified Clay Mineral Materials

2.1.1. Preparation of Modified Clay Mineral (Na-Z)

2.1.2. Preparation of Modified Clay Mineral (Mg-Al-La-LTHs@SBt)

2.2. Scheme for Preparation of Immobilized Microorganisms

2.3. Experimental Design

2.3.1. Experiment on Adsorption of Modified Clay Minerals

2.3.2. Experiment on Long-Term Restoration of Black-Odorous Water

2.4. Characterization and Analytical Methods

2.4.1. Material Characterization

2.4.2. Detection Methods for Pollutants in Overlying Water and Sediment

2.4.3. Data Analysis Methods

2.4.4. High-Throughput Sequencing

3. Results and Discussion

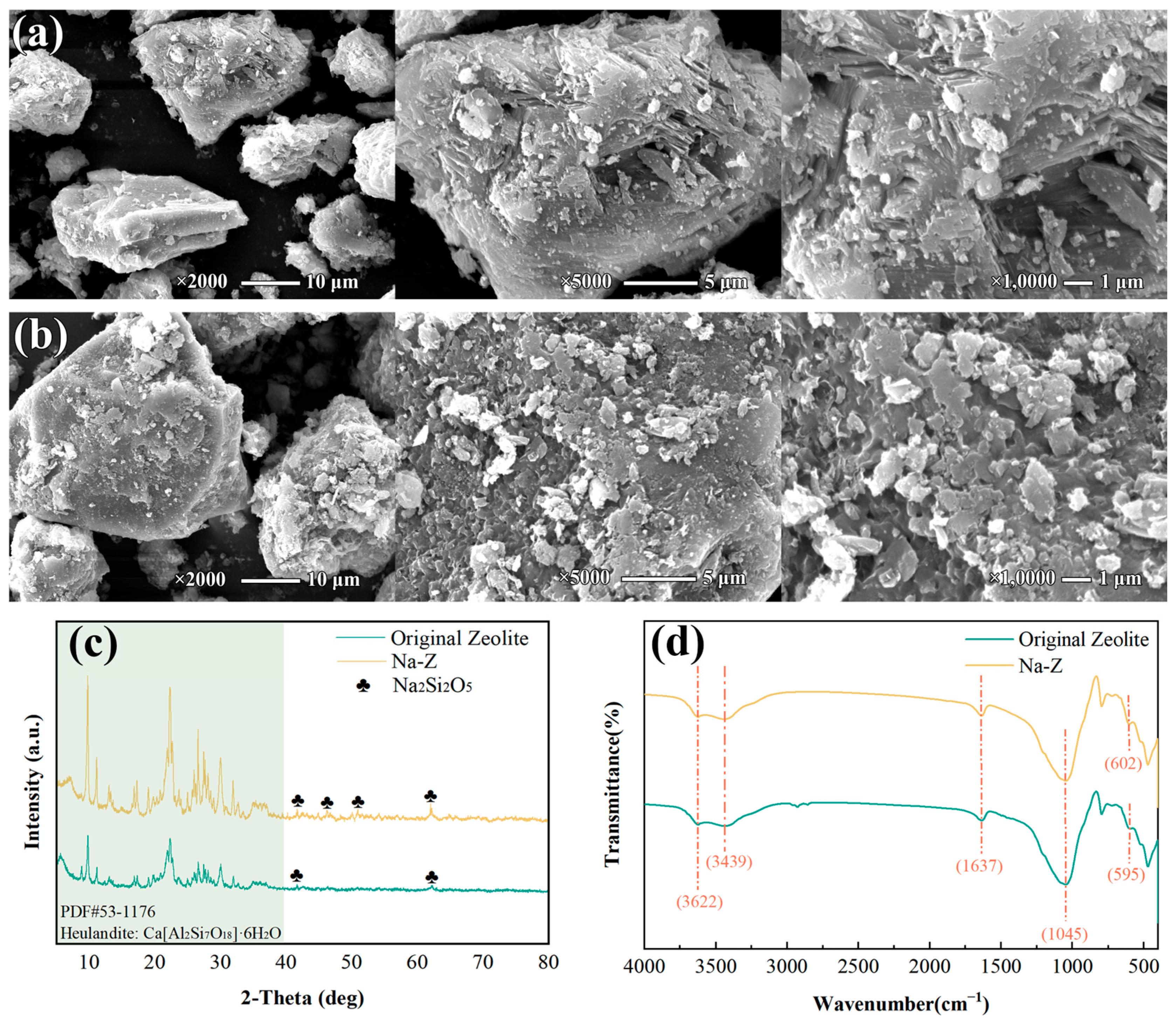

3.1. Characterization and Analysis of Modified Clay Minerals

3.1.1. Characterization and Analysis of Modified Zeolite

3.1.2. Characterization and Analysis of Modified Bentonite

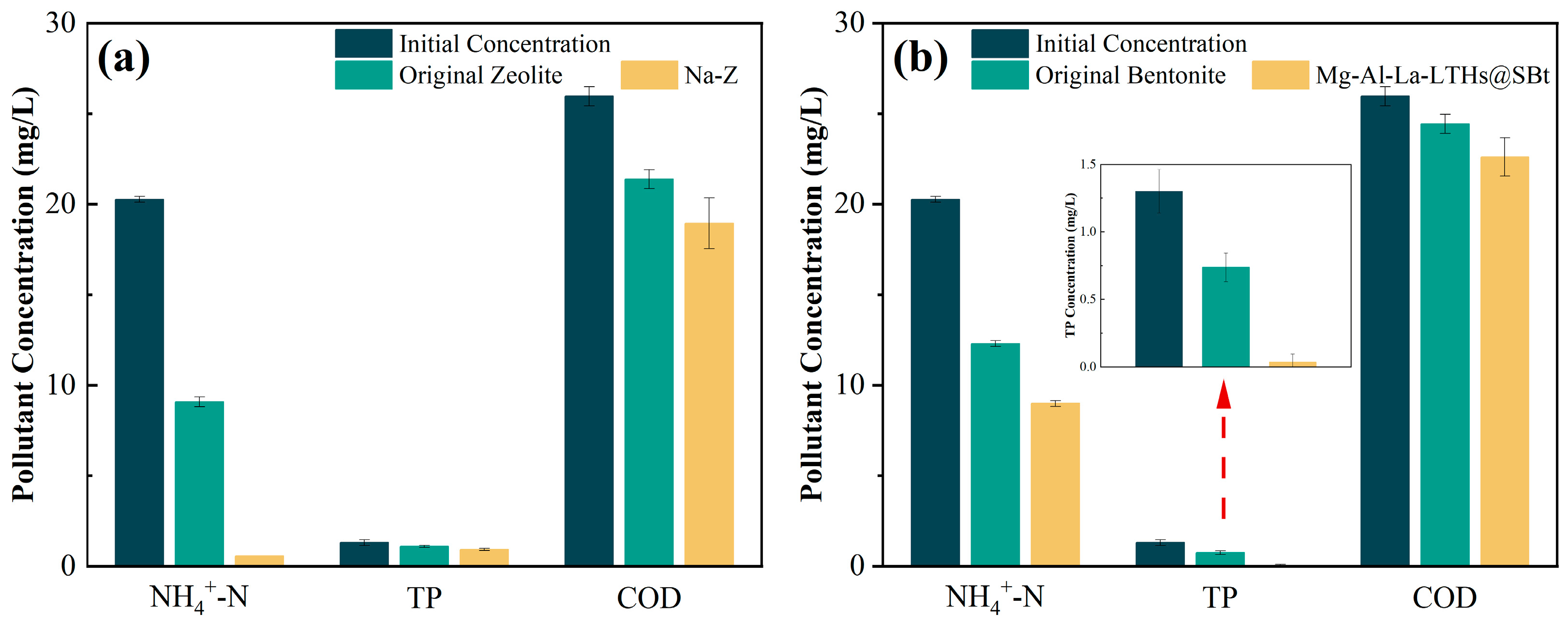

3.2. Adsorption Effect of Modified Clay Minerals on Pollutants

3.3. Effect of Composite Remediation Agent in Restoring Black-Odorous Water

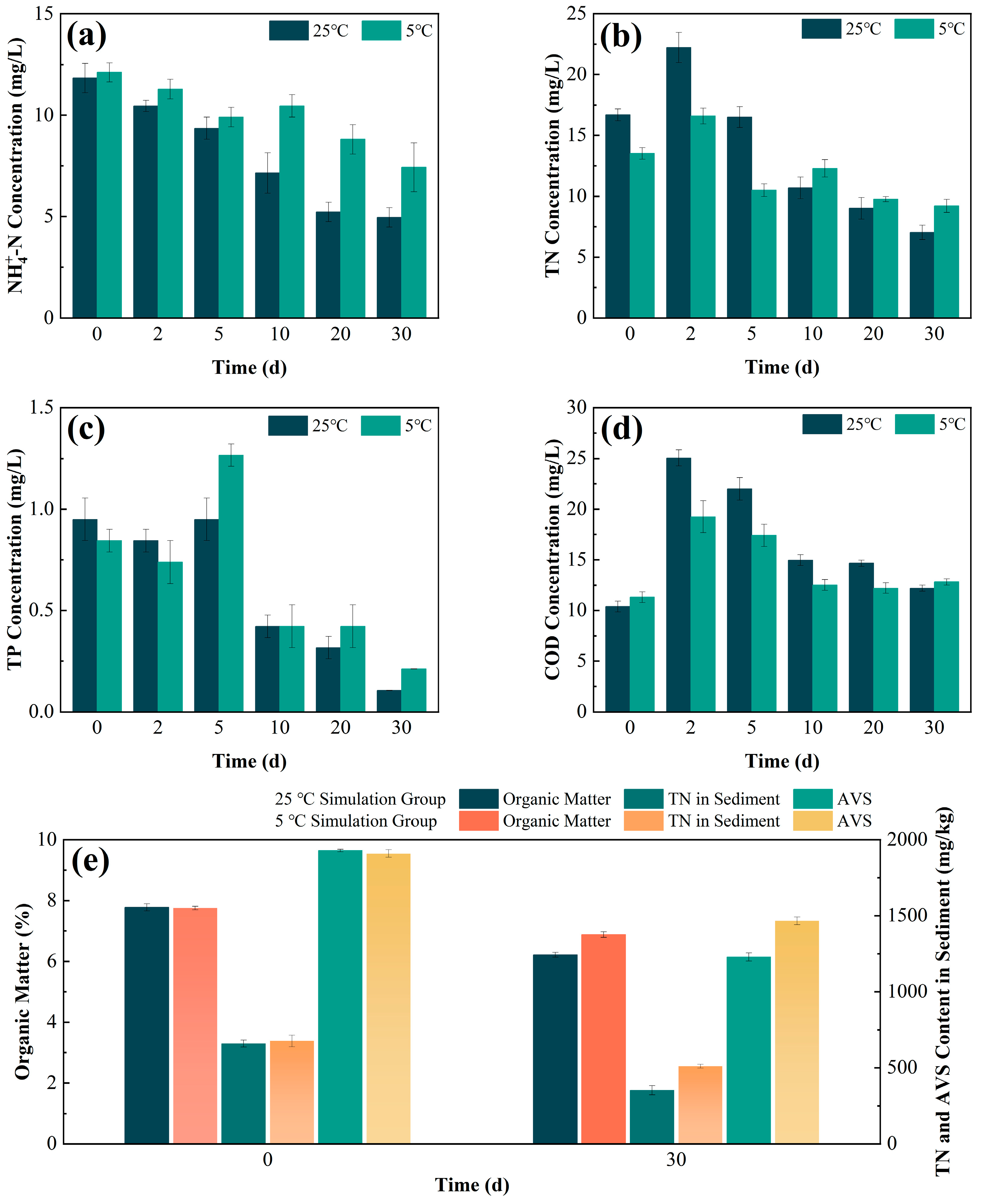

3.3.1. Performance of Composite Remediation Agent in Treating Black-Odorous Overlying Water

3.3.2. Effect of Composite Remediation Agent on Black-Odorous Sediment

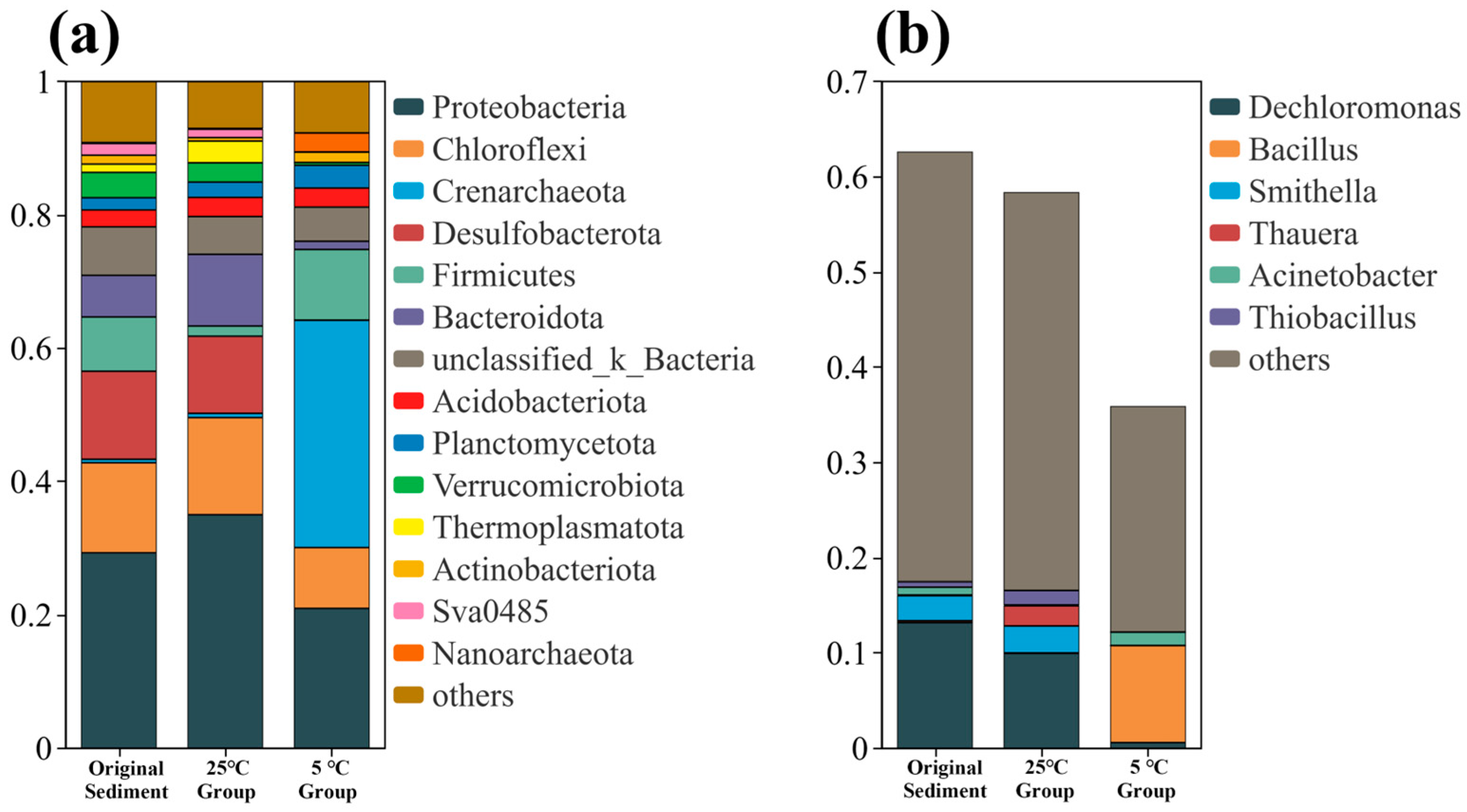

3.4. Changes in Microbial Community Structure of Sediment

3.5. Mechanism of Remediation Agent

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The modified clay minerals (Na-Z and Mg-Al-La-LTHs@SBt) exhibited strong adsorption capabilities, particularly for nutrient pollutants. In simulated experiments using actual black-odorous water, Na-Z achieved a 93.94% removal rate for NH4+-N, while Mg-Al-La-LTHs@SBt demonstrated a 125% improvement in TP removal compared to unmodified bentonite. The porous structures and surface functional groups of these materials also fostered a favorable microenvironment for microbial colonization.

- (2)

- Under simulated seasonal conditions, the composite remediation agent exhibited superior pollutant removal at 25 °C, particularly for TN, TP, and organic matter. Despite reduced microbial activity at 5 °C, the agent maintained excellent remediation performance through its inherent adsorption properties and partial microbial functionality, demonstrating good environmental adaptability across varying temperatures.

- (3)

- High-throughput sequencing of sediment samples revealed that the treatment enriched functional microbial phyla (e.g., Proteobacteria) and beneficial genera (e.g., Thiobacillus) while reducing the abundance of sulfate-reducing bacteria (e.g., Desulfobacterota). These shifts suggest that the composite agent facilitated beneficial changes in nitrogen and sulfur cycling at the micro-ecological level, supporting a synergistic mechanism of pollutant degradation and stabilization.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LTHs | Layered Ternary Hydroxides |

| PVA | Polyvinyl Alcohol |

| SA | Sodium Alginate |

| PEG | Polyethylene Glycol |

| NH4+-N | Ammonium Nitrogen |

| NO2−-N | Nitrite Nitrogen |

| NAR | Nitrite Accumulation Rate |

| TN | Total Nitrogen |

| TP | Total Phosphorus |

| COD | Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| AVS | Acid Volatile Sulfide |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscope |

| SEM-EDS | Scanning Electron Microscopy–Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy |

| XRD | X-Ray Diffraction |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

References

- Tian, Y.; Hu, Y.; Su, M.; Jia, Q.; Lian, X.; Jiao, L. Mitigation Measures Could Aggravate Unbalanced Nitrogen and Phosphorus Emissions from Land-Use Activities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 4627–4636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Meng, F.; Zhang, L.; Qin, Y.; Xue, H.; Liang, Z. Toxicity Threshold and Ecological Risk of Nitrate in Rivers Based on Endocrine-Disrupting Effects: A Case Study in the Luan River Basin, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 930, 172859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderian, D.; Noori, R.; Heggy, E.; Bateni, S.M.; Bhattarai, R.; Nohegar, A.; Sharma, S. A Water Quality Database for Global Lakes. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 202, 107401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupoae, O.-D.; Cristea, D.S.; Petrea, Ș.M.; Iticescu, C.; Radu, R.I.; Isai, V.M. A Mindset toward Greening the Blue Economy: Analyzing Social Environmental Awareness of Aquatic Ecosystem Protection. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2025, 210, 123901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Zhou, J.; Jin, Z.; Zhou, H. Simultaneous Capacitive Removal of Nitrate and Phosphate Pollutants via Zr-BTB@CNTs Electrode for Remediation of Aquatic Eutrophication. Desalination 2026, 617, 119451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Feng, M.; Ma, Q.; Liu, C. Enhanced Nitrogen Removal Performance of Microorganisms to Low C/N Ratio Black-Odorous Water by Coupling with Iron-Carbon Micro-Electrolysis. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 110893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Ye, J.; Zhang, W.; Hu, F.; Guo, Q.; Xu, Z. The Blackening Process of Black-Odor Water: Substance Types Determination and Crucial Roles Analysis. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 443, 130295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, D.; Liao, P.; Hu, X.; Yang, Y.; Chen, J. Effective Removal of Nitrogen and Phosphorus from a Black-Odorous Water by Novel Oxygen-Loaded Adsorbents. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 466, 143146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Wen, J.; Zhang, S.; Wu, C.; Ouyang, H.; Hu, N.; Li, X.; Qiu, X. The Coupling of Sulfide and Fe-Mn Mineral Promotes the Migration of Lead and Zinc in the Redox Cycle of High pH Floodplain Soils. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 472, 134546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, J.; Yang, Y.; Pan, G. Oxygen Micro-Nanobubbles for Mitigating Eutrophication Induced Sediment Pollution in Freshwater Bodies. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 331, 117281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; You, X. Critical Review of Magnetic Polysaccharide-Based Adsorbents for Water Treatment: Synthesis, Application and Regeneration. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 323, 129118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, Q.; Qi, X.; Yin, Q.; Liu, B.; He, K. Response and Synergistic Effect of Microbial Community to Submerged Macrophyte in Restoring Urban Black and Smelly Water Bodies. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 53, 103906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otunola, B.O.; Ololade, O.O. A Review on the Application of Clay Minerals as Heavy Metal Adsorbents for Remediation Purposes. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2020, 18, 100692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Feng, Y.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Wu, R. Adsorption and Immobilization of Phosphorus from Eutrophic Seawater and Sediment Using Attapulgite—Behavior and Mechanism. Chemosphere 2023, 313, 137390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- España, V.A.A.; Sarkar, B.; Biswas, B.; Rusmin, R.; Naidu, R. Environmental Applications of Thermally Modified and Acid Activated Clay Minerals: Current Status of the Art. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2019, 13, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikau, R.; Lujaniene, G. Adsorption Behaviour of Pollutants: Heavy Metals, Radionuclides, Organic Pollutants, on Clays and Their Minerals (Raw, Modified and Treated): A Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 309, 114685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barakan, S.; Aghazadeh, V. The Advantages of Clay Mineral Modification Methods for Enhancing Adsorption Efficiency in Wastewater Treatment: A Review. Env. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 2572–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Xie, R.; Chen, Y.; Pu, X.; Jiang, W.; Yao, L. A Novel Mesoporous Zeolite-Activated Carbon Composite as an Effective Adsorbent for Removal of Ammonia-Nitrogen and Methylene Blue from Aqueous Solution. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 268, 726–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velarde, L.; Nabavi, M.S.; Escalera, E.; Antti, M.-L.; Akhtar, F. Adsorption of Heavy Metals on Natural Zeolites: A Review. Chemosphere 2023, 328, 138508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lei, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Gao, J.; Zhao, S. Nitrogen Removal by Modified Zeolites Coated with Zn-Layered Double Hydroxides (Zn-LDHs) Prepared at Different Molar Ratios. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2018, 87, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Liu, D.-F. Tapping the Potential of Wastewater Treatment with Direct Ammonia Oxidation (Dirammox). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 7106–7108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; He, T.; Wu, P.; Wang, C.; Zheng, C. Recent Advances in the Nitrogen Cycle Involving Actinomycetes: Current Situation, Prospect and Challenge. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 419, 132100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, D.; He, G.; Yang, Z.; Xiong, X.; Liu, W. Activity and Community Structure of Nitrifiers and Denitrifiers in Nitrogen-Polluted Rivers along a Latitudinal Gradient. Water Res. 2024, 254, 121317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X. Heavy Metals Remediation through Lactic Acid Bacteria: Current Status and Future Prospects. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Li, B.; Ding, C.; Ni, R.; Lin, X. Core-Shell Structured Magnetic Beads Based on Sodium Alginate/Chitosan for Nitrogen Removal Enhancement. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 512, 162203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, H.A.; Ni, S.-Q.; Ahmad, S.; Zhang, J.; Ali, M.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W.; Tan, Z.; Wang, Q. Gel Immobilization: A Strategy to Improve the Performance of Anaerobic Ammonium Oxidation (Anammox) Bacteria for Nitrogen-Rich Wastewater Treatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 313, 123642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Sun, H.; Li, X.; Lu, Q.; Qin, P.; Yang, Y.; Lai, D.; Luo, L.; Peng, X.; et al. Accelerated Removal and Mechanism of Tetracycline from Water Using Immobilized Bacteria Combined with Microalgae. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Ma, H.; Su, X.; Song, J.; Liu, P.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y. Improved Nitrate Removal by Polyvinyl Alcohol/Sodium Alginate Hydrogel Beads Entrapping Salt-Tolerant Composite Bioagent AHM M3. Desalination 2024, 591, 118009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Li, M.; Wang, C.; Fan, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, H.; Wang, H. Enhanced Treatment of Landfill Leachate by Biochar-Based Aerobic Denitrifying Bacteria Functional Microbial Materials: Preparation and Performance. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1139650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, D.; Tabassum, S.; Li, J.; Altundag, H. Synergistic Effect of Reinforced Cellulose Nanofibrils/Polyethylene Glycol Embedded Particles in Ammonia Nitrogen Wastewater: An in-Depth Microbial Denitrification Analysis. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 68, 106336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrjou, A.; Hadaeghnia, M.; Ehsani Namin, P.; Ghasemi, I. Sodium Alginate/Polyvinyl Alcohol Semi-Interpenetrating Hydrogels Reinforced with PEG-Grafted-Graphene Oxide. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 263, 130258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yu, D.; Wang, Y.; Chen, G.; Tang, P.; Huang, S. A Novel Control Strategy for the Partial Nitrification and Anammox Process (PN/A) of Immobilized Particles: Using Salinity as a Factor. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 302, 122864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Cui, L.; Lin, B.; Zhang, J.; Huang, Z. Advanced Treatment of Piggery Tail Water by Dual Coagulation with Na+ Zeolite and Mg/Fe Chloride and Resource Utilization of the Coagulation Sludge for Efficient Decontamination of Cd2+. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 202, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Liu, K.; Wu, Z.; Wang, F. Internal Curing Mechanism of Zeolite Pretreated with NaCl under Microwave and Ultrasonic Conditions. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 78, 107633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Cui, S.; Fu, Z.; Song, X.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y. Preparation of Lanthanum-Modified Bentonite and Its Combination with Oxidant and Coagulant for Phosphorus and Algae Removal. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 59, 104925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Fu, Y.; Jiang, W.; Ye, Y.; Kang, J.; Liu, D.; Ren, Y.; Li, D.; Luo, C.; Xu, Z. Enhanced Phosphate Removal by Zeolite Loaded with Mg–Al–La Ternary (Hydr)Oxides from Aqueous Solutions: Performance and Mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 357, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Ding, Q.; Li, W.; Deng, J.; Lin, Q.; Li, J. Enhanced Treatment of Organic Matters in Starch Wastewater through Bacillus Subtilis Strain with Polyethylene Glycol-Modified Polyvinyl Alcohol/Sodium Alginate Hydrogel Microspheres. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 347, 126741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Tan, L.; Sun, H.; Chong, C.; Li, L.; Sun, B.; Yao, Z.; Zhuang, Y.; Wang, L. Manipulating Gelatinization, Retrogradation, and Hydrogel Properties of Potato Starch through Calcium Chloride-Controlled Crosslinking and Crystallization Behavior. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 357, 123371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zeng, J.; Zhang, M.; Sun, H.; Li, Y. Preparation and Properties of Functional Ionic Liquid Cross-linked Polyacrylamide-based Gel Microspheres with Compressive Strength and Stability. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2025, 65, 2642–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Zhu, X.; Fang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, X.; Zhu, X. Pyrolysis Temperature Dependent Effects of Biochar on Shifting Fluorescence Spectrum Characteristics of Soil Dissolved Organic Matter under Warming. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 892, 164656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Li, T.; Wang, Z.; Radu, T.; Jiang, H.; Wang, L. Effect of Aeration on Water Quality and Sediment Humus in Rural Black-Odorous Water. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 320, 115867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, F.; Peng, Y.; Kama, R.; Sajid, S.; Memon, F.U.; Ma, C.; Li, H. Enhanced Nutrient Removal from Aquaculture Wastewater Using Optimized Constructed Wetlands: A Comprehensive Screening of Microbial Complexes, Substrates, and Macrophytes. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 69, 106634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, P.J.; Fallowfield, H.J. Natural and Surfactant Modified Zeolites: A Review of Their Applications for Water Remediation with a Focus on Surfactant Desorption and Toxicity towards Microorganisms. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 205, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Fang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, K.; Tan, B.; Zhou, J. Succinic Acid-Assisted Modification of a Natural Zeolite and Preparation of Its Porous Pellet for Enhanced Removal of Ammonium in Wastewater via Fixed-Bed Continuous Flow Column. J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 48, 102906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Zhong, L.; Yu, Z.; Liu, W.; Abdel-Fatah, M.A.; Li, J.; Zhang, M.; Yu, J.; Dong, W.; Lee, S.S. Enhanced Adsorptive Removal of Ammonium on the Na+/Al3+ Enriched Natural Zeolite. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 298, 121507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, X. Adsorption of CO2 by a Novel Zeolite Doped Amine Modified Ternary Aerogels. Environ. Res. 2022, 214, 113855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Simon, A.O.; Jiao, C.; Zhang, M.; Yan, W.; Rao, H.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J. Rapid Removal of Sr2+, Cs+ and UO22+ from Solution with Surfactant and Amino Acid Modified Zeolite Y. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2020, 302, 110244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, R.; Donne, S.W.; Beyad, Y.; Liu, X.; Duan, X.; Yang, T.; Su, P.; Sun, H. Co-Pyrolysis of Wood Chips and Bentonite/Kaolin: Influence of Temperatures and Minerals on Characteristics and Carbon Sequestration Potential of Biochar. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanly, S.; Jelmy, E.J.; Nair, C.P.R.; John, H. Carbon Dioxide Adsorption Studies on Modified Montmorillonite Clay/Reduced Graphene Oxide Hybrids at Low Pressure. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 103344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katti, D.R.; Thapa, K.B.; Katti, K.S. The Role of Fluid Polarity in the Swelling of Sodium-Montmorillonite Clay: A Molecular Dynamics and Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy Study. J. Rock. Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2018, 10, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Yan, B.; Zou, X.; Cao, X.; Dong, L.; Lyu, X.; Li, L.; Qiu, J.; Chen, P.; Hu, S.; et al. Study on Ionic Liquid Modified Montmorillonite and Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2020, 587, 124311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasinskyi, V.; Malinowski, R.; Bajer, K.; Rytlewski, P.; Miklaszewski, A. Study of Montmorillonite Modification Technology Using Polyvinylpyrrolidone. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16, 105296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, P.; Lu, J.; Jiang, S.Y.; Lee, C.-H.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Ruan, H.D. Calcination Effect on Multi-Adsorption Abilities of Modified Montmorillonite. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2025, 343, 131008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, M.; Bayati, B.; Kazemian, H. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Phosphate Separation from Water Using HEU Zeolite: Unveiling Promising Strategies for Eutrophication Control. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2025, 396, 113733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, L.; Liu, S.; Yuan, D.; Zhang, Q.; Han, Z. Guest Cation Functionalized Metal Organic Framework for Highly Efficient C2 H2 /CO2 Separation. Small 2024, 20, 2405561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dithmer, L.; Lipton, A.S.; Reitzel, K.; Warner, T.E.; Lundberg, D.; Nielsen, U.G. Characterization of Phosphate Sequestration by a Lanthanum Modified Bentonite Clay: A Solid-State NMR, EXAFS, and PXRD Study. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 4559–4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandhi, D.; Bandyopadhyay, R.; Soni, B. Naturally Occurring Bentonite Clay: Structural Augmentation, Characterization and Application as Catalyst. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 57, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-L.; Yang, Y.-L.; Tan, X.; Li, X.; Zhao, L. Enhanced Nutrients Removal from Low C/N Ratio Rural Sewage by Embedding Heterotrophic Nitrifying Bacteria and Activated Alumina in a Tidal Flow Constructed Wetland. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 413, 131513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ya, T.; Liu, J.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Hai, R.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X. Metagenomic Insights into the Symbiotic Relationship in Anammox Consortia at Reduced Temperature. Water Res. 2022, 225, 119184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Gong, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, Y. Assessing the Influence of the Ecological Restoration Project on the Submerged Aquatic Vegetation in the Baiyangdian Lake, Northern China. Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 2024, 24, 864–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wei, Q.; Luo, Q.; Li, J.; Lin, B. XSBR-Mediated Biomass Polymers: A New Strategy to Solve the Low Toughness and High Hydrophilicity of Sodium Alginate Based Films and Use in Food Packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 318, 144979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Zhang, J. Sequential Combination of NaClO Chain Breakage/CuxO Catalytic Oxidation Processes for High Efficiency Treatment of Ultra-High Concentration PVA Wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, P.; Wang, X.; He, X.; Li, E.; Lan, Q.; Liu, Y.; Yin, D. Promotion Effect of Foam Formation on the Degradation of Polyvinyl Alcohol by Ozone Microbubble. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 111192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Dong, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, Z.; Cui, Z.; Ni, S.-Q. Using Sulfide as Nitrite Oxidizing Bacteria Inhibitor for the Successful Coupling of Partial Nitrification-Anammox and Sulfur Autotrophic Denitrification in One Reactor. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 475, 146286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Z.; Song, X.; Wang, Y.; Cao, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, B.; Chen, Y.; Arefe, A. Intensified Heterotrophic Denitrification in Constructed Wetlands Using Four Solid Carbon Sources: Denitrification Efficiency and Bacterial Community Structure. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 267, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Xu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zhou, X.; Lin, J.; Ruan, A. The Response Mechanism of Microorganisms to the Organic Carbon-Driven Formation of Black and Odorous Water. Environ. Res. 2023, 231, 116255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, W.; Liu, X.; Sheng, Y. Functional Microorganisms Drive the Formation of Black-Odorous Waters. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourne, D.G.; Morrow, K.M.; Webster, N.S. Insights into the Coral Microbiome: Underpinning the Health and Resilience of Reef Ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 70, 317–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Gu, X.; Wang, H.; Ma, J.; Huang, Y. Organic Sulfur-Driven Denitrification Pretreatment for Enhancing Autotrophic Nitrogen Removals from Thiourea-Containing Wastewater: Performance and Microbial Mechanisms. Water Res. 2025, 282, 123753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, B.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, W.; Peng, Y. Enrichment of Anammox Biomass during Mainstream Wastewater Treatment Driven by Achievement of Partial Denitrification through the Addition of Bio-Carriers. J. Environ. Sci. 2024, 137, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Zheng, F.; Wang, Z.; Hayat, K.; Veiga, M.C.; Kennes, C.; Chen, J. Unveiling Novel Pathways and Key Contributors in the Nitrogen Cycle: Validation of Enrichment and Taxonomic Characterization of Oxygenic Denitrifying Microorganisms in Environmental Samples. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 908, 168339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.W.; Shorten, P.R.; Altermann, E.; Roy, N.C.; McNabb, W.C. Competition for Hydrogen Prevents Coexistence of Human Gastrointestinal Hydrogenotrophs in Continuous Culture. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambacorta, F.V.; Dietrich, J.J.; Yan, Q.; Pfleger, B.F. Rewiring Yeast Metabolism to Synthesize Products beyond Ethanol. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2020, 59, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, C.; He, T.; Wang, C.; Zhang, M.; Yang, L.; Yang, L. Key Enzymes, Functional Genes, and Metabolic Pathways of the Nitrogen Removal-Related Microorganisms. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 54, 1672–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Zhao, X.; Senbati, Y.; Song, K.; He, X. Nitrogen Removal by Heterotrophic Nitrifying and Aerobic Denitrifying Bacterium Pseudomonas Sp. DM02: Removal Performance, Mechanism and Immobilized Application for Real Aquaculture Wastewater Treatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 322, 124555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, J.; Xie, M.; Yu, X.; Feng, H.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, T. A Review of the Definition, Influencing Factors, and Mechanisms of Rapid Composting of Organic Waste. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 342, 123125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ni, R.; Yang, Q.; Wang, B.; Li, G.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Fang, W.; Xu, D.; Gong, H.; et al. Composite Modified Clay Mineral Integrated with Microbial Active Components for Restoration of Black-Odorous Water. Sustainability 2026, 18, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010033

Ni R, Yang Q, Wang B, Li G, Zhao J, Zhang H, Zhang X, Fang W, Xu D, Gong H, et al. Composite Modified Clay Mineral Integrated with Microbial Active Components for Restoration of Black-Odorous Water. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010033

Chicago/Turabian StyleNi, Rui, Qian Yang, Bingyang Wang, Gezi Li, Jianqiang Zhao, Houkun Zhang, Xiaoqiu Zhang, Wei Fang, Dong Xu, Hui Gong, and et al. 2026. "Composite Modified Clay Mineral Integrated with Microbial Active Components for Restoration of Black-Odorous Water" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010033

APA StyleNi, R., Yang, Q., Wang, B., Li, G., Zhao, J., Zhang, H., Zhang, X., Fang, W., Xu, D., Gong, H., Bai, G., & Li, B. (2026). Composite Modified Clay Mineral Integrated with Microbial Active Components for Restoration of Black-Odorous Water. Sustainability, 18(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010033