Abstract

Transboundary plastic waste management is poorly understood due to the limited availability of comprehensive approaches to monitor plastic waste and pollution flows. To address this issue, this paper provides a detailed review of the existing monitoring methodologies and challenges associated with the acquisition of data on transboundary plastics. Data were extracted from 108 articles sourced from Scopus and Google Scholar using a systematic literature search, and from grey literature using a snowball search. Overall, 45 studies were included in the analysis and classified based on the monitoring methodologies employed, ranging from sampling with a laboratory analysis, to field studies, remote sensing studies, and oceanographic models. Based on the literature review, this paper supports the need to employ an integrated monitoring approach for the study of transboundary plastics that can overcome the limitations of individual technologies, while leveraging the strengths and opportunities of a technological mix. The paper also calls for understanding the value of monitoring technologies in supporting more effective decision-making on plastic waste reduction.

1. Introduction

Plastic waste in water bodies has been largely studied (see [1] for an extensive review), and a growing body of literature has concentrated on the implications of mismanaged plastic waste in coastal regions [2,3,4]. While scholars agree that tracking plastic waste and pollution flows is fundamental to implementing effective waste and pollution management strategies, observational data still fails to capture the full extent of transboundary plastic movement, and its transfer across socio-technical systems and into the sea, as well as its rooting causes.

Traditionally, plastic pollution is detected using in situ surveys, such as a visual census for macroplastics and water sampling for microplastics [5]. In recent years, satellite imagery and aerial surveys have emerged as new monitoring techniques due to their ability to grant a comprehensive spatio-temporal assessment of plastic pollution across larger regions [6,7], which could bring substantial benefits to the study of transboundary plastics. However, despite the fact that a wide array of methods exists and several authors have demonstrated their potential for detecting and quantifying the sources and mass loss of plastics to the ocean, their suitability for the global assessment of plastic pollution is being held up by the lack of standardized monitoring methodologies [8].

To overtake these constraints, a pioneering study introduced the concept of an integrated marine debris observing system (IMDOS), raising the need for combining different monitoring methods at different levels of analysis for a synoptic assessment of plastic pollution under real world conditions [9]. This is especially relevant along larger and border regions, where pollution monitoring is constrained by a number of interrelated issues, such as the inconsistent traceability of pollution flows due to different monitoring and accounting frameworks, different systems for keeping material flows accountable, or the insufficient exchange of information and analytics on pollution across borders [10], hence calling for collaborative cross-national efforts [11]. Moreover, when plastic flows outside the border of national jurisdictions and enters international waters, its monitoring and management become impossible [12].

Taking the stance of the research stream that supports the transition to an integrated monitoring of plastic pollution, the primary aim of this research is to evaluate the potential of both traditional and innovative monitoring methodologies, with a particular focus on the opportunities and limitations for detecting plastic flows across large-scale and transboundary regions, and to explore the added decision-support value of combining multiple monitoring techniques to investigate plastic waste management at different levels and scales of analysis.

The comprehensive monitoring of plastic waste and pollution flows is greatly advocated towards the proper management of plastic waste and control of plastic pollution. It is, in fact, imperative to supply more accurate estimates of the total amounts of plastic released into the ocean, especially when efficient metrics for accounting for transboundary plastics are lacking, hence hindering our ability to address mismanaged flows as “we can manage only what we can measure” [13]. Additionally, an integrated approach to the study of a complex environmental restoration challenge such as transboundary plastic pollution is fundamental to informing local, regional, and international governance to curb the stream of plastic entering the marine environment [14]. The systemic monitoring and assessment of global plastic pollution is essential in order to inform science-based policies and track the progress in mitigating and reducing the multifaceted impacts of plastic pollution on the environment [15]. Ultimately, this can supplement the current inadequacy of the international policy response to the problem of transboundary plastics by offering a consistent and harmonized approach to mapping the global movement of plastics [16].

Recent legal scholarship offers valuable insights into strengthening plastic pollution monitoring. Ref. [17] highlights that integrating environmental rights with the rights of nature provides a normative basis for monitoring plastics’ impacts on both human and ecological health. Ref. [18] underscores the importance of civil society in enforcing environmental law, a dynamic highly relevant where community-based initiatives often supply the most reliable data on plastic leakage. Meanwhile, ref. [19] shows that ambiguity in the legal definition of “waste” complicates enforcement, an issue directly affecting how plastics are classified, traced, and monitored. In conclusion, effective plastic pollution monitoring requires not only technical measurement systems but also clear legal definitions, strong institutional–societal enforcement dynamics, and a rights-based framework that justifies the sustained observation of plastics’ impacts on both humans and ecosystems.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reports the study’s methodology. Section 3 reports on the main findings, providing an overview of the existing plastic monitoring methodologies. Section 4 discusses the decisional value of traditional and emergent monitoring technologies against an integrated monitoring methodology. Finally, Section 5 draws conclusions and provides some final remarks.

2. Materials and Methods

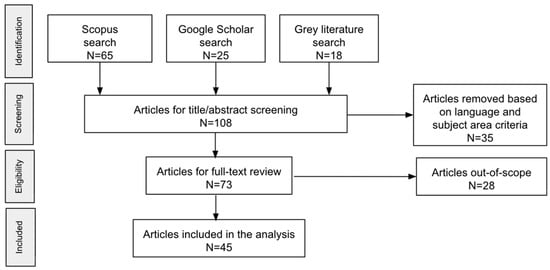

For this analysis, a literature search was conducted in June 2024 with the aim of providing a comprehensive analysis of traditional and emergent techniques for monitoring plastic pollution. Monitoring methodologies were retrieved from a systematic literature search on the Scopus and Google Scholar databases, using a single-string search approach (TITLE-ABS-KEY plastic* AND pollution AND monitor* OR detect* OR track* OR method* OR tech* OR tool*). Abstracts were screened based on language (English) and subject area (Environmental Science; Engineering; Energy; Materials Science; Business, Management and Accounting; Chemical Engineering). After the abstract screening and full-text review, 32 studies were included in the analysis based on their relevance. An additional 13 studies were retrieved from a snowball search of grey literature, including institutional reports, monitoring guidelines, and protocols. Based on the full-text review, included studies were then revised based on the monitoring techniques employed. Figure 1 shows a summary of the systematic literature search approach.

Figure 1.

Systematic literature search approach.

3. Results

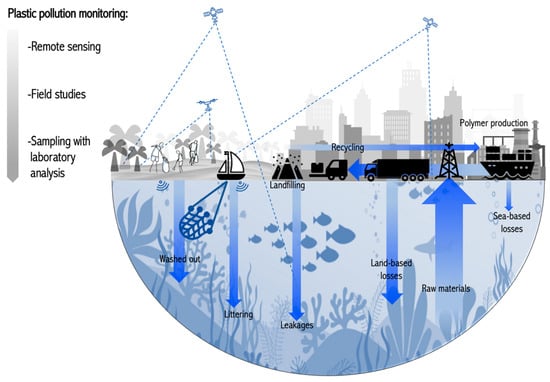

The extant literature offers remarkable examples of techniques for monitoring marine plastic pollution at different levels and scales. In the following subsections, we present an overview of the existing methodologies (Figure 2) and related challenges.

Figure 2.

Summary of monitoring techniques.

3.1. Single-Method Monitoring Techniques

Monitoring techniques can vary greatly based on the scale of analysis at which the monitoring is conducted, the type and size of the plastics, and the environmental compartments sampled (Table 1; Figure 1) [20]. Methods to assess the micro- (<5 mm) and nano-debris (<1 μm) involve the collection of samples in the field and their laboratory analysis [21]. Larger size classes—including mega- (>1000 mm), macro- (25–1000 mm), and mesoplastics (5–25 mm)—are generally assessed using visual observation methods and the collection of samples, such as during shoreline transects or trawling surveys [22,23]. These protocols have increasingly involved citizen scientists in the collection and basic analysis of plastics during beach cleanups [24,25,26,27,28], as well as specialized recreationists (e.g., scuba diver volunteers [29]).

For regions with high concentrations of larger debris, remote sensing approaches are becoming more prevalent. These include satellite-based observations [8,30], aerial surveys (e.g., using aircrafts or drones [31]), and underwater visual surveys of seafloor litter (e.g., using remotely operated vehicles [32,33]).

Finally, oceanographic models serve to simulate abundance and the physical mechanisms that govern the transport of floating plastics (see [34] for a detailed review). These models have remarkably been used to assess regional and global plastic releases from land to sea [35,36], compute the floating debris dispersal and predict areas of possible convergence [37,38], and identify the primary sources of plastic pollution [39].

Table 1.

Overview of different techniques for monitoring ocean plastics.

Table 1.

Overview of different techniques for monitoring ocean plastics.

| Scale | Single-Method Methodologies | Compartments | Debris Size | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling with laboratory analysis | Sand sieving (within quadrats) | Shoreline | Meso, micro | [23,40,41] |

| Sediment cores | Shoreline, seafloor | Micro | [21,22,42] | |

| Trawling | Sea surface, water column, seafloor | Micro, meso, macro | [22,23,41,43,44,45,46,47] | |

| Bulk water sampling | Sea surface, water column | Micro | [21,23,46,47] | |

| Biota sampling | All marine organisms | Nano, micro | [23,45,48,49,50,51,52] | |

| Field studies | Macrodebris survey | Shoreline | Macro | [22,23,41,44,45,53,54,55,56,57,58] |

| Direct observation | Sea surface, shoreline | Macro | [23,44,45,54,59] | |

| Scuba diving, snorkeling, manta tow | Shallow seafloor | Macro | [22,23,29,41,44,45,54,60] | |

| Entanglement visual survey | Fish, marine mammals, seabirds, sea turtles | Macro | [22,23] | |

| Remote sensing | Vessel-based aerial survey | Sea surface | Macro | [22,23,41,61] |

| Aircraft-based aerial survey | Sea surface, shoreline | Macro | [22,31] | |

| Submersibles and remote operated vehicles | Seafloor | Macro | [22,23,32,33,54] | |

| Unmanned aerial vehicle and drones | Sea surface, shoreline | Meso, macro | [6,57,62,63,64] | |

| Optical satellite data | Sea surface, shoreline | Macro | [6,7,64,65] | |

| Hyperspectral/multispectral earth observation | Sea surface, shoreline | Micro, meso, macro | [8,12,66,67,68,69,70,71] | |

| SAR (synthetic-aperture radar) | Sea surface, shoreline | Micro, meso, macro | [72,73] |

3.2. Towards Integrated Monitoring

Despite the variety of existing techniques, large knowledge gaps still exist around the state and movement of plastics across larger areas, as is the case for border regions, hence the importance of introducing multi-method monitoring methodologies that combine two or more techniques to collect information on plastic pollution at different levels and spatio-temporal scales. Notably, ref. [65] combined remote sensing observations with in situ observations to detect macroplastics in the Caribbean Sea, along the Guatemala-Honduras international border. In this study, high-resolution satellite images acquired from multiple sensors and spectral signatures were used to monitor the sources and transport mechanisms of plastic debris around the bay. Then, direct observations were collected through vessel and diving expeditions to verify the accuracy of the satellite observations and integrate additional debris that could not be detected via satellite.

Another example, proposed by [74], combined satellite data (imagery and spectra) with hydrodynamic models and in situ observations collected through trawling and sentiment sampling to monitor microplastics in the Adriatic Sea, along the Italy–Balkans border. In these studies, multiple monitoring methods are combined to provide a uniform, large-coverage assessment of plastic flows over an extended period of time.

3.3. Challenges with Existing Methods

In situ surveys (sampling and field studies) have traditionally been used to monitor marine plastic as they provide ground-truth reliable information on the sampling area. However, despite their effectiveness, they present a number of limitations. First, in situ surveys necessitate tremendous human effort and are time-consuming [5]. A second issue lies in the inability of these methods to account for the large diversity of land-based sources (e.g., riverine plastic emissions), which are considered the dominant input of marine pollution [35,48]. Thirdly, in situ surveys fail to capture the movement and transboundary nature of marine plastic pollution [75,76], as they are not suitable for large spatial areas [5].

Remote sensing techniques have more recently emerged as a valuable option to bridge some of the abovementioned gaps. Indeed, despite the fact that remote sensing technologies are still in their infancy, they could make a ground-breaking contribution to tackling plastic pollution, as they provide continuous temporal coverage that does not require human effort, harmonized data collection, and global coverage that can fill in gaps between sparse in situ observations [7]. However, studies demonstrate that different technologies can present technology-specific limitations pertaining to (i) the spatial resolution, which affects the ability to detect microplastics and smaller plastic concentrations from satellite imagery [30]; (ii) the limited temporal and spatial coverage [20], which hinder the detection of transboundary mechanisms; (iii) the operational costs (e.g., using drones or aerial surveys, and purchasing higher resolution images) [20]; and (iv) the operational capacity (TRL = 6–7), which is often confined to field-level demonstrations [77].

Another problem is that the existing approaches to monitoring plastic movements still fail to support and guide decision-making on the management and containment of transboundary plastic flows, which remain an open question. In fact, uncertainty remains concerning the ability of the existing methodologies to detect possible loopholes in the plastic value chain, including those related to the mismanagement of plastic waste, material loss or discharge into water bodies, and material leakages [2]. Another issue concerns the ability to properly detect and assess the impacts (ecological, social, and economic) associated with the system’s outflows [2,78,79,80] and the dislocated effects [81] of plastic’s consumption and end-of-life management. Finally, the lack of specific knowledge on the management of plastic flows can also hamper the possibility to guide policies and industrial recommendations.

Scholars contest that the existing approaches have separately assessed different information and decision-support dimensions, but methodologies that combine different methods into a consistent integrated monitoring methodology are still lacking [9]. An effective integrated monitoring methodology should offer a consistent combination of methods and instruments, also including qualitative and theoretical analyses, for collecting data on marine debris at different spatio-temporal scales and levels [9]. The availability of such a methodology should be considered a priority in light of providing a science-based assessment of how and where plastics move, and, thus, supporting more effective decision-making on ocean plastic pollution reduction [2,20].

Table 2 compares the information and decision-support value (as defined by [82]) of different monitoring methodologies.

Table 2.

Overview of information and decision-support value of different monitoring methodologies.

3.4. An Integrated Monitoring Methodology for Mapping Transboundary Plastics

Compared to the existing methodologies, integrated monitoring can bring about several advantages. First, such a methodology would be able to supply the current understanding of the magnitude, distribution, and temporal variability of plastic pollution, and their sources, fate, and pathways from land to sea [8,83]. Second, science-based quantitative information is useful for informing decisions on multiple fronts: for example, a richer knowledge of plastic losses from socio-technical systems can support decisions on how to sustainably manage material and pollution flows towards a circular economy of plastics [2]. Third, it would enable an assessment of the waste management infrastructure in place, including the existing loopholes in the value chain, inadequate disposal, and failures in the waste collection and recovery systems [2,20]. Fourth, such an assessment can guide the implementation of priority actions and transformative policies regarding waste management, as well as industrial recommendations for practitioners, via the identification of the points where plastic pollution can be most effectively managed and reduced [20]. Finally, integrated monitoring could address unanswered questions on the multifold impacts of mismanaged plastics (e.g., ecological impacts on ocean ecosystems, economic impacts on local economies, and social impacts) and trace them back to their generating sectors [2,84].

4. Discussion

4.1. Decision-Support Value of Monitoring Technologies

At present, the proper management of all plastic flows is hampered by our ability to answer questions about global plastic releases and losses from socio-technical systems into the environment, which, in turn, is being held up by the lack of standardized integrated methodologies for monitoring plastic pollution flows. Gaps in the research have emerged relative to the role and decision-support value of monitoring techniques (individually and combined) in providing ground-truth knowledge of plastic losses and leakages from different economic and societal sectors, and, hence, implementing effective containment strategies. Hence, based on the results of this review, we identified the following interrelated decisional areas that can be addressed through integrated monitoring (Table 3): (1) the identification of loopholes in the plastic cycle; (2) improving the data collection on mismanaged plastic flows; (3) the definition of needs and priorities to guide policies; and (4) providing science-based industrial recommendations for managing plastic flows.

Table 3.

Summary of existing challenges and opportunities relative to the identified decisional areas.

By implementing integrated monitoring frameworks, policymakers, industry stakeholders, and researchers can not only improve the transparency of plastic flows but also anticipate the emerging risks, evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, and, ultimately, promote a more circular and sustainable approach to plastic waste management. This approach underscores the need for harmonized methodologies that can bridge knowledge gaps and inform both local and global strategies for mitigating the plastic pollution in coastal areas.

4.1.1. Identification of Loopholes in the Plastic Cycle

Open Challenges

Managing plastic pollution requires extensive knowledge of pollution movement, starting from loss through fate and final sinks [2]. In particular, ref. [2] showed that global plastic losses to the environment were estimated at 9.2 million tonnes (Mt) in 2015, comprising approximately 67% macroplastics and 33% microplastics. Across the plastic life cycle, the use and end-of-life stages represent the largest sources of environmental losses, contributing about 36% and 55% of the total, respectively. However, there is still much uncertainty about the location and variability of the sources and pathways of mismanaged plastics [8,42,83,85]. The analysis of pollution sources is a complicated task due to (i) the presence of a large number of unidentified plastic fragments that could originate from multiple sources; (ii) uncertainties about the geographical origin of pollution, which is especially relevant when managing transboundary flows that can be transported over long distances for an undetermined period of time; and (iii) the poor understanding of the means of release through which plastic debris leaves the intended economic sector and enters the environment [86].

Examples of Technological Limitations of Existing Methodologies

When considering the monitoring methodologies in isolation, several technology-specific limitations arise. For example, the remote sensing of plastics is hampered by the resolution capacity of satellites (typically ranging from 5 m to 1 km), which makes it difficult or nearly impossible to detect pollution movements from space platforms, especially for smaller debris dispersed in the ocean or along beaches [20]. Concerning field sampling techniques, detecting pollution sources and pathways through visual inspection can become problematic when dealing with plastic fragments or items that cannot be directly connected to a specific source or way of release [86]. Thus, a plastic bottle stranded on the beach could be attributed to littering from beach users, or be transported over long distances through riverways, or be improperly disposed of in coastal waters and beached.

Opportunities from Integrated Monitoring

Integrated monitoring opens up new avenues for tracing back plastic accumulations to their original geographic and economic sources. Firstly, field observations and sampling offer multiple instruments to determine the composition of plastic loads through visual inspection and laboratory analysis, and, when possible, attribute litter to its original application sector [86,87,88]. Secondly, satellite data have been increasingly used to identify and map resource-use patterns and material flows across larger regions, and are especially useful in the context of cross-national industries to increase the value chain transparency [81], as is the case of transboundary plastic mechanisms. Thirdly, such data can be combined with historical sources, national statistics, and reports of industrial activities to deepen the understanding of the land uses and economic activities with potential for marine pollution. Fourthly, experimental monitoring can be combined with plastic flows modeling (e.g., material flow analysis) to support the study of all plastic and pollution flows along the plastic value chain. Combining all these methods into an integrated monitoring methodology provides (i) the mapping of loopholes in the current plastic value chain, waste collection, and management infrastructure; (ii) insights into the existing problems and most critical spatial areas that necessitate priority interventions to contain material leakages and losses at the source; (iii) new knowledge of the variability of waste streams and uncaptured material flows; and (iv) the geographical and spatial distribution of polluting actors and activities, that can help us become more aware of their contributions and plastic footprint and, hence, implement ad hoc containment strategies.

4.1.2. Improving Data Collection on Mismanaged Plastic Flows

Open Challenges

The current assessments of the distribution and composition of pollution flows, spatio-temporal variability of plastic loads, and possibility of recovery are patchy [8,34]. One part of the problem originates from the lack of comprehensive estimates of plastic waste losses and mismanaged fractions, as these amounts are likely to end up in unauthorized dumpsites, be illegally disposed of, or be handled by the informal waste sector [2].

Examples of Technological Limitations of Existing Methodologies

Gaps in the research have emerged relative to the suitability of the existing remote sensing and in situ techniques for detecting marine plastics. For example, there is still uncertainty about the relationship between plastic litter composition and remote sensing reflectance, which can especially affect the ability of satellite technologies to detect plastics in water (see [8]). Issues can be related to the presence of other materials with a similar chemical composition to plastic debris, which can interfere with plastic detection, or to the characteristics of the sampled surface, which can affect the spectral response (e.g., a rougher surface will produce a more diffuse reflection), or to the mismatch between the known spectral bands for plastic materials and the observed ones (e.g., when plastic is transported for longer periods, its chemical composition might be affected by weathering, solar radiations, and degradation in ways that are still unknown) [8]. Hence, such analyses necessitate further knowledge of the spectra associated with plastic debris at the microscopic level. Concerning in situ sampling, a visual census is less effective in identifying the materials, types, and composition of smaller debris or fragments [87], and requires a further chemical analysis.

Opportunities from Integrated Monitoring

Integrating multiple data collection techniques allows for (i) a more comprehensive classification of debris’ physico-morphological characteristics; (ii) overcoming and complementing the limits of individual technologies relative to material detection, thus increasing the technological capacity; and (iii) bridging the gaps from the cross-national data collection, pertaining to the use of different accounting and measuring systems. Therefore, for example, while optical and hyperspectral imaging from space and aerial surveys can be used to detect the spatio-temporal variability and composition of plastic loads on larger areas (e.g., [6,71]), sampling yields a further level of analysis and/or validation of the satellite observations (e.g., [70]).

4.1.3. Definition of Needs and Priorities to Guide Policies

Open Challenges

A substantial reduction in plastic inputs into water bodies is at the forefront of ocean stewardship [78,79,80,89,90], and international efforts to govern marine pollution have been underway for decades (from MARPOL [91,92,93] to the most recent Global Plastic Treaty [94,95,96]). Nevertheless, several interrelated issues persist. First, ocean governance in matters of pollution and material discharge is fragmented across national and local jurisdictions, which contrasts with the globalized nature of the plastic value chain, hence making it more difficult to link industrial losses to their potential impacts [97]. Second, existing leakage reduction policies, both at the national and industrial level, are limited in focus and coverage, and necessitate a far larger scale of implementation to effectively address the challenges of transboundary plastic pollution [98]. Third, the implementation of these policies is highly uneven across different jurisdictions, which is reflected in the substantial differences in the local waste infrastructure and industry conduct [97], limiting the combined efforts for managing and retaining transboundary plastics [10].

Examples of Technological Limitations of Existing Methodologies

The limited scale and low frequency of observations can severely affect the ability of monitoring to depict a comprehensive picture of plastic pollution and related issues, including identifying high-priority areas that require urgent intervention and monitoring the effects of policy implementation over time. For the first, different analyses require different spatial and temporal scales. At present, there is a mismatch between the scales of spatial and temporal remote sensing observations, especially when considering short intervals of time [8]. For the latter, the frequency of remote sensing observations is constrained by the revisit time of different satellites (ranging between days and weeks), which can limit the acquisition of high-resolution imagery, especially when tracking highly dynamic environmental compartments such as rivers and estuaries [99]. The scale and frequency of field studies too are limited by several factors, such as the greater need of human resources and time effort required for continuous and/or repeated measurements [5].

Opportunities from Integrated Monitoring

Combining qualitative and quantitative techniques in pollution monitoring enables us to capture the full spectrum of areas that require priority action and intervention, from leakage origin, to uncaptured material flows with potential to harm the environment and marine ecosystems, to areas that are most at risk of or impacted by plastic pollution. Identifying such areas is crucial to guiding and designing future implementations to meet the specific needs and challenges of marine plastic pollution [100]. Integrated monitoring can serve several purposes: (i) It enables the definition of indicators and standards for comprehensively assessing and reporting plastic movement, especially in the case of transboundary issues that require a common understanding of priorities and needs [100]. (ii) It also provides ground-truth information on the state of waste collection and management to guide ad hoc leakage control interventions, such as litter control to restrict litter generating activities; source control to reduce the sources of pollution and reduce their potential losses into waterways; or downstream control measures such as the installation of physical barriers for retaining litter from entering the ocean, or the promotion of cleanup and removal efforts [101]. (iii) Knowledge of needs and priorities can guide and support the implementation of industry-level measures across the entire plastic value chain, such as extended producer responsibility and management of resource and waste flows, targeting flows that are more at risk of becoming marine pollution [102]. (iv) Finally, integrated monitoring allows us to assess the impacts of policy implementation over time, evaluating the progress, comparing the effectiveness of different policies, and steering the implementation of new policies based on the results.

4.1.4. Providing Science-Based Industrial Recommendations for Managing Plastic Flows

Open Challenges

The effective management of plastic leakages requires significant innovation across the entire value chain [98]. Many industries are taking the lead in the fight against plastic pollution by implementing individual and isolated solutions that often result in a mixture of widely varying business practices at different levels and scales, which bring about even further fragmentation along the value chain [100]. This is also intensified by the general tendency of industrial actors to overvalue individual responsibility and self-governance as management principles [97], as well as to link sustainability performance to brand value, which can turn sustainability actions into mere market competition rather than system-level benefits [103]. Therefore, these practices necessitate systemic coordination and informed design to meet the specific challenges of plastic pollution [100].

Examples of Technological Limitations of Existing Methodologies

Spatially explicit data on the locations and magnitude of the impacts associated with global value chains are needed to establish a relationship between the industry and related environmental impacts [81], especially in areas that are hardly perceived as threat hotspots [104]. However, it is often difficult to draw such connections between pollution-generating sectors and activities (e.g., fishing, offshore mining, maritime transport, tourism, illegal dumping, transport, etc.) and their contributions to plastic pollution, due to the paucity of observation-based pattern recognition and matching algorithm systems to match the hotspot of marine litter and their trajectories with their respective sources [20].

Opportunities from Integrated Monitoring

If integrated monitoring serves the purpose of mapping the spatial distribution of sources and economic sectors generating pollution on one side, it is also fundamental for supplying industrial actors with science-based evidence of plastic leakages and loopholes along the value chain, high-risk mismanaged waste streams, and infrastructural inefficiencies. Knowledge of the weaknesses and opportunities along the value chain equips industrial players with a powerful tool to implement impactful measures and create the enabling conditions for a system change [98]. This can translate into concrete actions to improve companies’ business circularity and reduce their plastic footprint, engage in collaborative efforts to reduce waste generation, and mitigate the impacts of plastic pollution at all stages of the value chain (from production to use and end of life) [89,98].

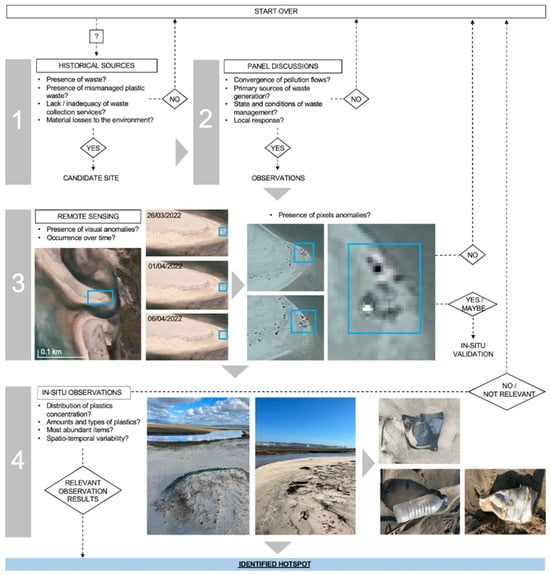

4.2. Implementing an Integrated Approach

A preliminary example of integrated monitoring is offered by [82,105]. In their study, the authors applied integrated monitoring to (i) identify hotspots of plastic pollution along the U.S.–Mexico international border; (ii) determine the pollution sources (geographical and economic sectors, and activities generating plastics), pathways (from land to sea), and driving causes; (iii) and quantitatively estimate the spatio-temporal variability of transboundary plastic flows. The proposed integrated approach gathered data from four main sources: First, they used historical data of chemicals and pollutants on the ground surface and in sediment samples contained in water flows across the Tijuana River Watershed and compared them with the current physical, chemical, and biological water quality conditions of the Tijuana River. This step allowed us to identify hotspots of trash accumulation (by weight and density), with a particular focus on plastic debris. Second, based on the hotspot identification, they confirmed the identified areas with a panel of experts on waste management and pollution on both sides of the international border. The goal of the panel discussion was to review and validate the results obtained from the hotspot identification and better define the areas for conducting remote sensing and in situ observations. Third, they obtained optical satellite images of the pollution hotspots to determine key features of the locations, pollution entry points, and areas of possible debris accumulations. Finally, they conducted in situ observations within the sampling areas previously identified via satellite, recording the photographic evidence, notes, category, and amount, and estimating the coverage of plastic waste. An overview of the methodology used is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Example application of integrated monitoring for the Tijuana River Watershed.

4.3. Limitations and Future Recommendation

The integrated monitoring methodology presented in this paper is not intended to be exhaustive, but, rather, it offers a pilot application illustrating the value of combining different qualitative and quantitative methods to capture the broader picture of transboundary plastic movements. Some limitations of this approach can be attributed to the type of data collected and to the specific techniques included in this analysis. Thus, future research could explore the added value of integrating further remote sensing observations, such as hyperspectral or multispectral imagery, which can yield a richer assessment of the litter composition, or an aircraft-based survey to provide high-resolution data at different scales and levels.

The analysis of [82,105] shows that losses can result from inadequate waste management and calls for an improvement of the waste collection and management infrastructure as a direct means to reduce plastic losses. To this end, cross-border solutions are imperative to effectively manage plastic waste streams on both sides of the international border. Suggested options include (but are not limited to) the standardization of waste collection and treatment targets between San Diego and Tijuana, the ban of illegal dumping sites along the Tijuana River, the maintenance and improvement of existing waste-retainment systems located across the international border. At the local level, pollution monitoring enables us to identify the areas that require priority intervention as well as the main issues with existing waste management activities, including formal and informal beach cleanups. A more detailed understanding of these challenges is critical to guiding and designing policies to meet the specific needs and implement tailored regulatory instruments [100]. Finally, at the industrial level, effective interventions can include (i) closing the leakage points within the collection and waste management infrastructure to eliminate the inadequate disposal, accidental losses, and mismanagement of plastic waste near waterways; (ii) expanding plastic waste collection to reduce the probability of leakage into water bodies; and (iii) combining a variety of end-of-life management technologies to recover and treat plastic waste [89].

This holistic systemic understanding of plastic losses throughout the entire plastic life cycle can support meaningful mitigation and leakage control strategies, as the effective management of plastic pollution requires combined efforts at all stages of the value chain [99].

5. Conclusions

The main objective of this review is to track traditional and novel methods to monitor plastic pollution across larger and border regions, and understand their value in supporting more effective decision-making on plastic waste reduction. To this end, we compared the information and decision-support value of traditional single-method techniques against integrated monitoring. Despite the fact that the latter is still in its infancy, it has already demonstrated the potential to bridge the open challenges associated with traditional techniques, while providing a robust methodology to (1) identify loopholes in the plastic cycle, (2) improve the existing data collection on mismanaged plastic flows, (3) define the needs and priorities to guide policies, and (4) provide science-based industrial recommendations for managing plastic flows.

By integrating multiple data sources and methods, integrated monitoring provides a more complete understanding of the spatial and temporal patterns of plastic flows. This approach not only strengthens the scientific foundation for regulatory and policy decisions but also promotes cross-border collaboration in tackling this global environmental challenge. In addition, it helps design targeted interventions, optimize the use of resources, and monitor the progress toward sustainability goals. As monitoring technologies and analytical tools continue to improve, integrated approaches are expected to play an increasingly important role in guiding adaptive management strategies and achieving a significant reduction in plastic pollution.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M.; methodology, C.M., D.V. and G.F.; formal analysis, C.M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M.; writing—review and editing, C.M., D.V., G.F., P.T., C.A. and S.C.; visualization, C.M.; supervision, P.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kasavan, S.; Yusoff, S.; Fakri, M.F.R.; Siron, R. Plastic pollution in water ecosystems: A bibliometric analysis from 2000 to 2020. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 313, 127946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryberg, M.W.; Hauschild, M.Z.; Wang, F.; Averous-Monnery, S.; Laurent, A. Global environmental losses of plastics across their value chains. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 151, 104459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebreton, L.; Andrady, A. Future scenarios of global plastic waste generation and disposal. Palgrave Commun. 2019, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, K.B.; Chen, K.; Chen, P.; Wang, C.; Cai, M. Socioeconomic relation with plastic consumption on 61 countries classified by continent, income status and coastal regions. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2021, 107, 786–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salgado-Hernanz, P.M.; Bauzà, J.; Alomar, C.; Compa, M.; Romero, L.; Deudero, S. Assessment of marine litter through remote sensing: Recent approaches and future goals. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 168, 112347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topouzelis, K.; Papakonstantinou, A.; Garaba, S.P. Detection of floating plastics from satellite and unmanned aerial systems (Plastic Litter Project 2018). Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2019, 79, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, L.; Clewley, D.; Martinez-Vicente, V.; Topouzelis, K. Finding plastic patches in coastal waters using optical satellite data. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Vicente, V.; Clark, J.R.; Corradi, P.; Aliani, S.; Arias, M.; Bochow, M.; Bonnery, G.; Cole, M.; Cózar, A.; Donnelly, R.; et al. Measuring marine plastic debris from space: Initial assessment of observation requirements. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximenko, N.; Corradi, P.; Law, K.L.; Van Sebille, E.; Garaba, S.P.; Lampitt, R.S.; Galgani, F.; Martinez-Vicente, V.; Goddijn-Murphy, L.; Veiga, J.M.; et al. Toward the integrated marine debris observing system. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vito, D.; Fernandez, G.; Maione, C. A toolkit to monitor marine litter and plastic pollution on coastal tourism sites. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2022, 21, 1721–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Proceedings of the United Nations Environment Assembly at Its Fifth Session; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021; Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/items/8beac987-e233-4780-a25f-5aff72cf52bb (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- De Giglio, M.; Dubbini, M.; Cortesi, I.; Maraviglia, M.; Parisi, E.I.; Tucci, G. Plastics waste identification in river ecosystems by multispectral proximal sensing: A preliminary methodology study. Water Environ. J. 2021, 35, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, J.; Billard, G. The challenges of measuring plastic pollution. Field Actions Science Reports. J. Field Actions 2019, 19, 68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Vince, J.; Hardesty, B.D. Plastic pollution challenges in marine and coastal environments: From local to global governance. Restor. Ecol. 2017, 25, 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Bank, M.S.; Swarzenski, P.W.; Duarte, C.M.; Rillig, M.C.; Koelmans, A.A.; Metian, M.; Wright, S.; Provencher, J.F.; Sanden, M.; Jordaan, A.; et al. Global plastic pollution observation system to aid policy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 7770–7775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, G.; Failler, P. Governing plastic pollution in the oceans: Institutional challenges and areas for action. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 112, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessina, S. The Link Between Environmental Rights and the Rights of Nature: The Virtues of a Complexity-Based Approach. Jurid. Trib.-Rev. Comp. Int. Law 2025, 15, 406. [Google Scholar]

- Todorović, B. A Comparative Analysis of Environmental Activism in Albania, Romania and Serbia: Lessons in Civil Society Enforcement of Administrative Law. Jurid. Trib. 2025, 15, 108–140. [Google Scholar]

- Lazíková, J.; Rumanovská, L.U. Waste in the EU Law. Jurid. Trib.-Rev. Comp. Int. Law 2024, 14, 260–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garello, R.; Plag, H.P.; Shapiro, A.; Martinez, S.; Pearlman, J.; Pendleton, L. Technologies for Observing and Monitoring Plastics in the Oceans. In OCEANS 2019-Marseille; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo-Ruz, V.; Gutow, L.; Thompson, R.C.; Thiel, M. Microplastics in the marine environment: A review of the methods used for identification and quantification. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 3060–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MSFD. Marine Litter: Technical Recommendations for the Implementation of MSFD Requirements; European Commission: Ispra, Italy, 2011; Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC67300 (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- GESAMP. Guidelines for the Monitoring and Assessment of Plastic Litter and Microplastics in the Ocean; Kershaw, P.J., Turra, A., Galgani, F., Eds.; GESAMP Reports and Studies, No. 99 (IMO/FAO/UNESCO-IOC/UNIDO/WMO/IAEA/UN/UNEP/UNDP/ISA Joint Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Environmental Protection); International Maritime Organization: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo-Ruz, V.; Thiel, M. Distribution and abundance of small plastic debris on beaches in the SE Pacific (Chile): A study supported by a citizen science project. Mar. Environ. Res. 2013, 87, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelms, S.E.; Eyles, L.; Godley, B.J.; Richardson, P.B.; Selley, H.; Solandt, J.L.; Witt, M.J. Investigating the distribution and regional occurrence of anthropogenic litter in English marine protected areas using 25 years of citizen-science beach clean data. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 263, 114365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelms, S.E.; Easman, E.; Anderson, N.; Berg, M.; Coates, S.; Crosby, A.; Eisfeld-Pierantonio, S.; Eyles, L.; Flux, T.; Gilford, E.; et al. The role of citizen science in addressing plastic pollution: Challenges and opportunities. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 128, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambonnet, L.; Vink, S.C.; Land-Zandstra, A.M.; Bosker, T. Making citizen science count: Best practices and challenges of citizen science projects on plastics in aquatic environments. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 145, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syberg, K.; Palmqvist, A.; Khan, F.R.; Strand, J.; Vollertsen, J.; Clausen, L.P.W.; Feld, L.; Hartmann, N.B.; Oturai, N.; Møller, S.; et al. A nationwide assessment of plastic pollution in the Danish realm using citizen science. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotti, G.; Esposito, V.; D’Alessandro, M.; Panti, C.; Vivona, P.; Consoli, P.; Figurella, F.; Romeo, T. Seafloor litter along the Italian coastal zone: An integrated approach to identify sources of marine litter. Waste Manag. 2021, 124, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C. Remote detection of marine debris using satellite observations in the visible and near infrared spectral range: Challenges and potentials. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 259, 112414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebreton, L.; Slat, B.; Ferrari, F.; Sainte-Rose, B.; Aitken, J.; Marthouse, R.; Hajbane, S.; Cunsolo, S.; Schwarz, A.; Levivier, A.; et al. Evidence that the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is rapidly accumulating plastic. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioakeimidis, C.; Papatheodorou, G.; Fermeli, G.; Streftaris, N.; Papathanassiou, E. Use of ROV for assessing marine litter on the seafloor of Saronikos Gulf (Greece): A way to fill data gaps and deliver environmental education. SpringerPlus 2015, 4, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, S.; Saito, H.; Fletcher, R.; Yogi, T.; Kayo, M.; Miyagi, S.; Ogido, M.; Fujikura, K. Human footprint in the abyss: 30 year records of deep-sea plastic debris. Mar. Policy 2018, 96, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardesty, B.D.; Harari, J.; Isobe, A.; Lebreton, L.; Maximenko, N.; Potemra, J.; Van Sebille, E.; Vethaak, A.D.; Wilcox, C. Using numerical model simulations to improve the understanding of micro-plastic distribution and pathways in the marine environment. Front. Mar. Sci. 2017, 4, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebreton, L.; Van Der Zwet, J.; Damsteeg, J.W.; Slat, B.; Andrady, A.; Reisser, J. River plastic emissions to the world’s oceans. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Sebille, E.; Aliani, S.; Law, K.L.; Maximenko, N.; Alsina, J.M.; Bagaev, A.; Bergmann, M.; Chapron, B.; Chubarenko, I.; Cózar, A.; et al. The physical oceanography of the transport of floating marine debris. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 023003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, M.; Lebreton, L.C.; Carson, H.S.; Thiel, M.; Moore, C.J.; Borerro, J.C.; Galgani, F.; Ryan, P.G.; Reisser, J. Plastic pollution in the world’s oceans: More than 5 trillion plastic pieces weighing over 250,000 tons afloat at sea. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maximenko, N.; Hafner, J.; Niiler, P. Pathways of marine debris derived from trajectories of Lagrangian drifters. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2012, 65, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liubartseva, S.; Coppini, G.; Lecci, R.; Clementi, E. Tracking plastics in the Mediterranean: 2D Lagrangian model. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 129, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPA. EPA’s Microplastic Beach Protocol: A Community Science Protocol for Sampling Microplastic Pollution; United States Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2021-09/microplastic-beach-protocol_sept-2021.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Lippiatt, S.; Opfer, S.; Arthur, C. Marine Debris Monitoring and Assessment: Recommendations for Monitoring Debris Trends in the Marine Environment; NOAA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2013. Available online: https://marinedebris.noaa.gov/modeling-and-monitoring/marine-debris-monitoring-and-assessment-recommendations-monitoring-debris-trends-marine-environment (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Thompson, R.C.; Olsen, Y.; Mitchell, R.P.; Davis, A.; Rowland, S.J.; John, A.W.; McGonigle, D.; Russell, A.E. Lost at sea: Where is all the plastic? Science 2004, 304, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galgani, F.; Leaute, J.P.; Moguedet, P.; Souplet, A.; Verin, Y.; Carpentier, A.; Goraguer, H.; Latrouite, D.; Andral, B.; Cadiou, Y.; et al. Litter on the sea floor along European coasts. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2000, 40, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheshire, A.C.; Adler, E.; Barbière, J.; Cohen, Y.; Evans, S.; Jarayabhand, S.; Jeftic, L.; Jung, R.T.; Kinsey, S.; Kusui, E.T.; et al. UNEP/IOC Guidelines on Survey and Monitoring of Marine Litter; UNEP Regional Seas Reports and Studies, No. 186; IOC Technical Series No. 83; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2009; pp. xii+120. [Google Scholar]

- JRC. Guidance on Monitoring of Marine Litter in European Seas. EUR 26113 EN; Joint Research Centre of the European Commission: Ispra, Italy, 2013.

- Song, Y.K.; Hong, S.H.; Jang, M.; Kang, J.H.; Kwon, O.Y.; Han, G.M.; Shim, W.J. Large accumulation of micro-sized synthetic polymer particles in the sea surface microlayer. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 9014–9021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setälä, O.; Magnusson, K.; Lehtiniemi, M.; Norén, F. Distribution and abundance of surface water microlitter in the Baltic Sea: A comparison of two sampling methods. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 110, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GESAMP. Sources, Fate and Effects of Microplastics in the Marine Environment: Part Two of a Global Assessment; Kershaw, P.J., Rochman, C.M., Eds.; (IMO/FAO/UNESCO-IOC/UNIDO/WMO/IAEA/UN/UNEP/UNDP Joint Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Environmental Protection); GESAMP Reports & Studies Series 93; International Maritime Organization: London, UK, 2016; 220p. [Google Scholar]

- Karami, A.; Golieskardi, A.; Choo, C.K.; Romano, N.; Ho, Y.B.; Salamatinia, B. A high-performance protocol for extraction of microplastics in fish. Sci. Total. Environ. 2017, 578, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, T.M.; Vethaak, A.D.; Almroth, B.C.; Ariese, F.; van Velzen, M.; Hassellöv, M.; Leslie, H.A. Screening for microplastics in sediment, water, marine invertebrates and fish: Method development and microplastic accumulation. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 122, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fourie, A.J.; Marlin, D. Sample Preparation Manual for the Analysis of Plastic-Related Pollutants; African Marine Waste Network, Sustainable Seas Trust: Gqeberha, South Africa, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dellisanti, W.; Leung, M.M.L.; Lam, K.W.K.; Wang, Y.; Hu, M.; Lo, H.S.; Fang, J.K.H. A short review on the recent method development for extraction and identification of microplastics in mussels and fish, two major groups of seafood. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 186, 114221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OSPAR. Guideline for Monitoring Marine Litter on the Beaches in the OSPAR Maritime Area; OSPAR Commission: London, UK, 2010; Available online: https://repository.oceanbestpractices.org/handle/11329/1466 (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Galgani, F.; Fleet, D.; Van Franeker, J.; Katsanevakis, S.; Maes, T.; Mouat, J.; Oosterbaan, L.; Poitou, I.; Hanke, G.; Thompson, R.; et al. Marine Strategy Framework Directive: Task Group 10 Report Marine Litter; IFREMER: Brest, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sheavly, S.B. National Marine Debris Monitoring Program: Final Program Report, Data Analysis and Summary; Prepared for U.S. Environmental Protection Agency by Ocean Conservancy; Grant Number X83053401-02; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Water: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; 76p. [Google Scholar]

- NOWPAP. Guidelines for Monitoring Litter on the Beaches and Shorelines of the Northwest Pacific Region; NOWPAP CEARAC: Toyama City, Japan, 2007; Available online: https://www.unep.org/nowpap/resources/toolkits-manuals-and-guides/guidelines-monitoring-marine-litter-beaches-and-shorelines-0 (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Opfer, S.C.; Arhur, C.; Lippiatt, S. NOAA Marine Debris Shoreline Survey Field Guide; NOAA Marine Debris Program: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2012; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Barnardo, T.; Ribbink, A.J. African Marine Litter Monitoring Manual; Sustainable Seas Trust: Port Elizabeth, South Africa, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, P.G. A simple technique for counting marine debris at sea reveals steep litter gradients between the Straits of Malacca and the Bay of Bengal. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2013, 69, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donohue, M.J.; Boland, R.C.; Sramek, C.M.; Antonelis, G.A. Derelict fishing gear in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands: Diving surveys and debris removal in 1999 confirm threat to coral reef ecosystems. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2001, 42, 1301–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, M.; Hinojosa, I.; Vásquez, N.; Macaya, E. Floating marine debris in coastal waters of the SE-Pacific (Chile). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2003, 46, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deidun, A.; Gauci, A.; Lagorio, S.; Galgani, F. Optimising beached litter monitoring protocols through aerial imagery. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 131, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taddia, Y.; Corbau, C.; Buoninsegni, J.; Simeoni, U.; Pellegrinelli, A. UAV Approach for Detecting Plastic Marine Debris on the Beach: A Case Study in the Po River Delta (Italy). Drones 2021, 5, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topouzelis, K.; Papageorgiou, D.; Karagaitanakis, A.; Papakonstantinou, A.; Arias Ballesteros, M. Remote sensing of sea surface artificial floating plastic targets with Sentinel-2 and unmanned aerial systems (plastic litter project 2019). Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikaki, A.; Karantzalos, K.; Power, C.A.; Raitsos, D.E. Remotely sensing the source and transport of marine plastic debris in Bay Islands of Honduras (Caribbean Sea). Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuña-Ruz, T.; Uribe, D.; Taylor, R.; Amézquita, L.; Guzmán, M.C.; Merrill, J.; Martínez, P.; Voisin, L.; Mattar, C. Anthropogenic marine debris over beaches: Spectral characterization for remote sensing applications. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 217, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremezi, M.; Kristollari, V.; Karathanassi, V.; Topouzelis, K.; Kolokoussis, P.; Taggio, N.; Aiello, A.; Ceriola, G.; Barbone, E.; Corradi, P. Pansharpening PRISMA Data for Marine Plastic Litter Detection Using Plastic Indexes; IEEE Access: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; Volume 9, pp. 61955–61971. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, B.; Sannigrahi, S.; Sarkar Basu, A.; Pilla, F. Development of Novel Classification Algorithms for Detection of Floating Plastic Debris in Coastal Waterbodies Using Multispectral Sentinel-2 Remote Sensing Imagery. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddijn-Murphy, L.; Peters, S.; Van Sebille, E.; James, N.A.; Gibb, S. Concept for a hyperspectral remote sensing algorithm for floating marine macro plastics. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 126, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshtaghi, M.; Knaeps, E.; Sterckx, S.; Garaba, S.; Meire, D. Spectral reflectance of marine macroplastics in the VNIR and SWIR measured in a controlled environment. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garaba, S.P.; Dierssen, H.M. An airborne remote sensing case study of synthetic hydrocarbon detection using short wave infrared absorption features identified from marine-harvested macro-and microplastics. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 205, 224–235. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, M.C.; Ruf, C.S. Toward the detection and imaging of ocean microplastics with a spaceborne radar. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 4202709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davaasuren, N.; Marino, A.; Boardman, C.; Alparone, M.; Nunziata, F.; Ackermann, N.; Hajnsek, I. Detecting microplastics pollution in world oceans using SAR remote sensing. In IGARSS 2018-2018 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 938–941. [Google Scholar]

- Atwood, E.C.; Falcieri, F.M.; Piehl, S.; Bochow, M.; Matthies, M.; Franke, J.; Carniel, S.; Sclavo, M.; Laforsch, C.; Siegert, F. Coastal accumulation of microplastic particles emitted from the Po River, Northern Italy: Comparing remote sensing and hydrodynamic modelling with in situ sample collections. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 138, 561–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krelling, A.P.; Souza, M.M.; Williams, A.T.; Turra, A. Transboundary movement of marine litter in an estuarine gradient: Evaluating sources and sinks using hydrodynamic modelling and ground truthing estimates. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 119, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, L.M.; Agostini, V.O.; Lima, A.R.A.; Ward, R.D.; Pinho, G.L.L. The fate of plastic litter within estuarine compartments: An overview of current knowledge for the transboundary issue to guide future assessments. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 279, 116908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellou, N.; Gambardella, C.; Karantzalos, K.; Monteiro, J.G.; Canning-Clode, J.; Kemna, S.; Arrieta-Giron, C.A.; Lemmen, C. Global assessment of innovative solutions to tackle marine litter. Nat. Sustain. 2021, 4, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Report of the First Meeting of the Ad Hoc Open-Ended Expert Group on Marine Litter and Microplastics; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018; Available online: https://apps1.unep.org/resolutions/uploads/business_and_industry_major_group_submission_may_29_2018_v.2.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- UNEP. Report of the Second Meeting of the Ad Hoc Open-Ended Expert Group on Marine Litter and Microplastics; United Nations Environment Programme: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://resolutions.unep.org/resolutions/uploads/2nd_ahoeeg_business_and_industry_submission_6_december_2018.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- UNEP. Report of the Third Meeting of the Ad Hoc Open-Ended Expert Group on Marine Litter and Microplastics; United Nations Environment Programme: Bangkok, Thailand, 2019; Available online: https://www.unep.org/events/un-environment-event/third-meeting-ad-hoc-open-ended-expert-group-marine-litter-and (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Moran, D.; Giljum, S.; Kanemoto, K.; Godar, J. From satellite to supply chain: New approaches connect earth observation to economic decisions. One Earth 2020, 3, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maione, C.; Vito, D.; Fernandez, G.; Trucco, P. Characterization of Transboundary Transfer Mechanisms for Improved Plastic Waste Management: A Study on the US–Mexico Border. Water 2025, 17, 1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, G.; Orlando-Bonaca, M. Ten inconvenient questions about plastics in the sea. Environ. Sci. Pol. 2018, 85, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cózar, A.; Echevarría, F.; González-Gordillo, J.I.; Irigoien, X.; Úbeda, B.; Hernández-León, S.; Palma, Á.T.; Navarro, S.; García-de-Lomas, J.; Ruiz, A.; et al. Plastic debris in the open ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 10239–10244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, J.M.; Fleet, D.; Kinsey, S.; Nilsson, P.; Vlachogianni, T.; Werner, S.; Galgani, F.; Thompson, R.C.; Dagevos, J.; Gago, J.; et al. Identifying Sources of Marine Litter; MSFD GES TG Marine Litter Thematic Report, JRC Technical Report, EUR 28309; MSFD: Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tramoy, R.; Blin, E.; Poitou, I.; Noûs, C.; Tassin, B.; Gasperi, J. Riverine litter in a small urban river in Marseille, France: Plastic load and management challenges. Waste Manag. 2022, 140, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Marine Plastic Debris and Microplastics—Global Lessons and Research to Inspire Action and Guide Policy Change; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016; Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/publication/marine-plastic-debris-and-microplastics-global-lessons-and-research-inspire (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- UNEP. Mapping of Global Plastic Value Chain and Plastic Losses to the Environment: With a Particular Focus on Marine Environment; United Nations Environment Programme: Paris, France, 2018; Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/mapping-global-plastics-value-chain-and-plastics-losses-environment-particular (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- UNGC. Ocean Stewardship 2030. In Ten Ambitions and Recommendations for Growing Sustainable Ocean Business; United Nations Global Compact: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- IMO. Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter; International Maritime Organization: London, UK, 1972; Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/ourwork/environment/pages/london-convention-protocol.aspx (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- IMO. International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships 1973/78; International Maritime Organization: London, UK, 1973; Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/about/conventions/pages/international-convention-for-the-prevention-of-pollution-from-ships-(marpol).aspx (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- IMO. 1996 Protocol to the Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter, 1972; International Maritime Organization: London, UK, 2006; Available online: https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/OurWork/Environment/Documents/PROTOCOLAmended2006.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- UNEP. Zero Draft Text of the International Legally Binding Instrument on Plastic Pollution, Including in the Marine Environment; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2023; Available online: https://resolutions.unep.org/resolutions/uploads/algeria_0.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- UNEP. Revised Draft Text of the International Legally Binding Instrument on Plastic Pollution, Including in the Marine Environment; United Nations Environment Programme: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2024; Available online: https://hiraishi.cool.coocan.jp/Data/Plastics-.Draft%20Text-Contemts.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- UNEP. Compilation of Draft Text of the International Legally Binding Instrument on Plastic Pollution, Including in the Marine Environment; United Nations Environment Programme: Busan, Republic of Korea, 2024; Available online: https://docs.un.org/en/UNEP/PP/INC.5/4 (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Dauvergne, P. Why is the global governance of plastic failing the oceans? Glob. Environ. Change 2018, 51, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Pew Charitable Trusts; SYSTEMIQ. Breaking the Plastic Wave: A Comprehensive Assessment of Pathways Towards Stopping Ocean Plastic Pollution; The Pew Charitable Trusts: London, UK, 2020; Available online: https://www.systemiq.earth/breakingtheplasticwave/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Wu, W.; Yang, Z.; Chen, C.; Tian, B. Tracking the environmental impacts of ecological engineering on coastal wetlands with numerical modeling and remote sensing. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 302, 113957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. From Pollution to Solution. In A Global Assessment of Marine Litter and Plastic Pollution; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. From City to Sea: Management of Litter and Plastics in Urban Areas—A Guide for Municipalities; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/290281634796071121/pdf/From-City-to-Sea-Integrated-Management-of-Litter-and-Plastics-and-Their-Effects-on-Waterways-A-Guide-for-Municipalities.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- EIA.; Greenpeace. Checking out plastic policy. In Assessing UK Retailer Positions on Policy Approaches to Reducing Plastic Pollution; Environmental Investigation Agency: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, P.; Feber, D.; Granskog, A.; Nordigården, D.; Ponkshe, S. The Drive Toward Sustainability in Packaging—Beyond the Quick Wins. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/paper-forest-products-and-packaging/our-insights/the-drive-toward-sustainability-in-packaging-beyond-the-quick-wins (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Moran, D.; Kanemoto, K. Identifying species threat hotspots from global supply chains. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 1, 0023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maione, C. Unfolding the Systemic Role of Emerging End-of-Life Technologies Towards a Circular Economy of Plastics. Ph.D. Thesis, Politecnico di Milano, Milan, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.