Abstract

It is well known that the features of self-driving vehicles depend on communication technologies to demonstrate their benefits. Since these technologies are still under development and face numerous obstacles, this highlights the need to develop a modern approach to solving congestion during the transitional phase. In this study, we worked on developing an integrated new operational strategy that maximizes the benefits of the variable speed limit strategy and expands its impact by coordinating its operation with the spacing policy mechanism in vehicles equipped with adaptive cruise control (ACC) to provide an innovative approach aims to operate vehicles with low levels of autonomy and leverage their ability to maintain short time gaps to operate as an effective category to improve traffic conditions, aided by existing transportation systems. To achieve this, we employed PTV-VISSIM to develop the VSL algorithm, which was coded using the VisVAP interface. We also used VISSIM features to model and develop the characteristics of the ACC vehicles and the spacing policy. Different control strategies were tested individually and in combination at various penetration rates, and the results demonstrated the superiority of our proposal to integrate the VSL mechanism with the short-time gap recommendation strategy. The strategy’s effect was also evident in emissions reductions of 52% to 86% and in fuel consumption decreases of 52% to 87% compared to the no-control scenario, and of 56% to 28% compared to the typical VSL scenario, supporting an environmental sustainability approach in traffic strategies.

1. Introduction

Although vehicles equipped with Adaptive Cruise Control (ACC) have been widely available for over a decade and offer technological advantages, their impact remains limited or unclear in many field studies [1,2,3,4]. This is mainly because most ACC systems rely on relatively conservative default time-gap settings that are higher than those used by conventional drivers, thereby reducing the route’s operational capacity and limiting the expected benefits at high deployment levels. In addition to inconsistent driver use of the system, one reason may be the lack of supporting infrastructure. Therefore, the theoretical advantages of the ACC system in improving traffic flow and mitigating shock wave disturbances in mixed traffic environments are rarely realized [5,6,7]. The solution may lie in developing simplified operation strategies that do not require advanced communication technologies, specialized environments, or high costs, as it could be achieved by leveraging existing intelligent traffic system (ITS) strategies. Standardizing speeds and smoothing out variations between them, along with regulating and shortening time gaps, will not only help alleviate these problems but also reduce fuel consumption and emissions in mixed traffic, thus supporting efforts to transition towards sustainable transport [8,9].

1.1. Variable Speed Limit Control (VSL)

Many studies have confirmed the effectiveness of smart traffic management strategies, and speed standardization is a successful approach in this area. Variable Speed Limit Control (VSL) is one such approach. VSL is a type of intelligent transportation system (ITS) that uses traffic detection and technology to set acceptable speed limits for drivers based on current roadway and traffic conditions. These regulation speeds are typically shown on overhead or portable variable message signs (VMS). By using traffic detection technologies to decide acceptable speed limits for drivers based on current roadway and traffic circumstances. When the variable-speed limit system is activated, all vehicles will attempt to adjust their speed to a similar range. The potential for VSL to eliminate speed differences between cars and lanes is known as speed harmonization. Traffic turbulence, such as merging and lane-changing, is reduced when a smaller speed differential is maintained, which reduces braking and makes the longitudinal system more stable, thus helping maintain relatively smaller gaps. By harmonizing speed differences and stabilizing traffic flow. VSL strategy may contribute to reducing the deterioration caused by the introduction of ACC-AVs [10,11,12,13].

1.2. Time Headway and “Spacing Policy,” in AV

The penetration of autonomous vehicles is increasing, especially at lower levels such as vehicles equipped with the ACC-AV system, which, although they have been in the market for a long time, still operate as conventional vehicles without taking advantage of their useful features that could contribute to raising the efficiency of road operations and enhancing safety and sustainability. Previous studies indicate that traffic flow may not significantly improve with ACC vehicles due to traffic unpredictability and the presence of large gaps between vehicles, which can negatively impact the capacity [14,15]. Although ACC drivers have a set of gap settings, the default values for time gap and acceleration are a bit conservative. These conservative parameter values will result in reduced road capacity compared to conventional manual vehicles, where human driver behavior can be described as more aggressive [16].The key point here is that the (ACC) system’s range of acceleration and time gap settings, when set to its minimum, is less conservative than manual driving, so adaptive cruise control systems can improve handling by maintaining following gaps as short as one second, compared to the two-second minimum often preferred by conventional drivers [17,18].That is due to its multiple features, including the so-called “spacing policy,” which determines the distance between the preceding and following vehicles. This policy allows the system to maintain a fixed distance from the vehicle ahead by controlling the throttle and brake, according to the driver’s settings. Reducing the vehicle interval has previously been suggested to achieve capacity gains, as studies indicate that this can occur at a high adaptive cruise control penetration rate when an interval setting between 1.20 and 1.10 s is chosen [19]. Based on the above, the main objective of our research will be to develop a strategy for integrating a variable-speed limit system with an AV spacing policy, recommending a short time gap. Therefore, the hypothesis to be evaluated is that this strategy is effective in mixed traffic environments. And test its impact on traffic efficiency, fuel consumption, and emissions. The hypothesis is based on scientific facts that were considered when developing the proposed operational strategy and identifying its key elements and their respective roles. And highlights these facts by referring to fundamental microscopic variables, their characteristics, and their interrelationships. The hypothesis uses the minimum time-gap setting for ACC vehicles as a critical factor. Time headway is an accurate measure of traffic behavior in car-following models at the microscopic level, defined as the time interval between two vehicles passing a given point. Many studies have shown that the average time headway is inversely related to traffic flow rate (q) under steady-state conditions, making it a key variable for linking individual driver behavior to traffic flow and road capacity. This can be formulated as follows:

where q denotes the traffic flow (veh/second), h is the average time headway (seconds), Cv refers to the theoretical capacity, and hm is the minimum time headway [20,21]. When the headway between vehicles decreases, more vehicles can pass through in the same unit of time, resulting in higher flow and greater capacity. In conventional vehicles, the following time is inconsistent with speed; in ACC vehicles, it is virtually constant across all speeds according to the system’s settings, while only the distance between vehicles is adjusted to reflect the current speed ACC systems are governed by the Constant Time Gap Law, which is expressed by the following equation.

where S represents the distance between two vehicles (meters), v is the vehicle speed (m/s), h denotes the fixed time headway set by the system or by the user (seconds), and S0 corresponds to a minimum stopping distance. This results in greater sequential regularity, which improves the theoretical capacity of roads under conditions of sufficient deployment and a stable system. However, it is not that simple; there are practical limitations to consider. Although ACC vehicles can maintain a constant time headway in almost all velocities, the gains from activating the ACC system will vary due to several practical factors, including the penetration rate and the time gap setting pattern [22,23,24]. In mixed traffic, high penetration rates and adopting long time gaps (≥2.2 s) will significantly reduce capacity, specifically during periods of high demand. Despite a stable string, the number of vehicles crossing a given time unit decreases, leading to earlier congestion compared to shorter gaps, while intermediate gaps, which typically range from ~1.5 to 2.0 s, allow for more flexible movement and greater utilization of the theoretical capacity. Unlike automated vehicles, which tend to follow a path, human drivers make lane-changing maneuvers when a suitable gap appears, seeking a faster route, which can lead to increased erratic behavior. By minimizing the time gap to the lower limit, typically estimated at 0.8–1.2 s, high levels of capacity are achievable. However, challenges remain in chain stability and headway dispersion, especially before reaching high penetration rates. Setting a short time gap makes the ACC system extremely sensitive, as any slight change in the speed of the preceding vehicle can lead to a sharp deceleration or sudden stop. A conventional driver typically brakes at a rate of 1.5–2.0 m/s2, while the ACC system brakes at higher values, sometimes as high as 3–4 m/s2, to achieve a consistent gap. This variation in deceleration rates resulting from heterogeneous interactions between vehicles in mixed traffic will lead to inhomogeneity in flow, turbulence amplification, and a loss of theoretical capacity gains [25,26]. This highlights the necessity of developing simple, practical strategies that can be implemented during this transitional phase.

S = v × h + S0

1.3. Background and Motivation

According to the literature, many solutions have been developed to address traffic congestion as advanced levels of autonomous vehicles are introduced, including specialized speed-adjustment algorithms that operate proactively or reactively to address capacity shortages [27,28,29]. Furthermore, significant efforts have been made to develop solutions to address undesirable effects and improve the performance of the adaptive cruise control system. One such strategy is the offline gap control strategy, which relies on the adaptive cruise control system’s settings to control speed and spacing. This is achieved by optimizing the use of these settings based on field trials, historical data, or simulations before the vehicle is put into operation, rather than adjusting them dynamically [30]. In this context, some studies have improved the time gaps to be within a range of 0.64 to 2.40 s. Researchers also studied the types of spacing policies, including constant spacing (CS), constant time gap (CTG), and variable time gap (VTG), and their effects on the stability of vehicle fleets. The last two types were found to be stable when designed appropriately, though the conclusions are not without some reservations [31,32,33,34,35]. More advanced systems, including cooperative driving systems, still face challenges related to communication, practical obstacles, and other difficulties inherent to these technologies. This presents another negative reason, in addition to the observed negative effects of adaptive cruise control. Other efforts have been made to develop real-time gap control systems, recognizing the significant obstacles that still need to be addressed, such as communication delays, radar processing losses, and numerous uncertainties [36]. While a limited number of researchers have sought alternative solutions or operational strategies to leverage the characteristics of low-automated vehicles that have entered the market without relying on communication. In light of the theoretical analysis of the impact of time-gap settings in Adaptive Cruise Control (ACC) systems, the importance of developing strategic time-gap control policies becomes clear to improve the performance of these vehicles and to leverage their benefits. This may occur aided by a supportive infrastructure that encourages or mandates human drivers to activate the ACC system with the proper settings in their automated vehicles. Therefore, this study aims to bridge this gap and present a simple, applicable integrated operational strategy that combines VSL with the spacing policy for vehicles equipped with ACC, a short-time gap recommendation test, and speed determination, all in accordance with actual traffic conditions. The study objectives can be summarized as follows:

1—Designing a coordinated control framework that combines VSL and ACC vehicle spacing policy by linking infrastructure-based speed strategies with vehicle-level longitudinal control recommendations.

2—Modeling and implementing the proposed strategy using the PTV-VISSIM simulation platform to enable dynamic speed adjustment and implementation of automated spacing policies.

3—Evaluate the impact of individual and combined strategies (VSL only, short setup in ACC only, and a combination of both) on traffic flow stability and environmental sustainability.

4—Analyzing the impact of different rates of ACC vehicle deployment on the effectiveness of the integrated strategy within mixed traffic scenarios.

5—Evaluate the impact of the integrated strategy on reducing emissions and its role in supporting sustainable transport goals.

6—Providing operational and application recommendations on how to integrate infrastructure control with vehicle-level control in existing intelligent transportation systems without using advanced communication technologies.

In this research, we present a new scientific contribution in the form of developing an integrated control strategy that directly links the variable speed limits (VSL) issued by the infrastructure with the spacing policies of vehicles equipped with Adaptive Cruise Control (ACC), as this research focus has not received sufficient attention in previous studies. Most previous work has focused on studying VSL or ACC separately [37,38,39]. Based on idealized assumptions of high levels of automation, this research aims to bridge this gap by modeling the realistic coexistence of conventional vehicles and vehicles equipped with Active Cruise Control (ACC) at varying deployment rates. The research used a PTV-VISSIM(Germany) simulation environment to enable control at two layers: the first relies on infrastructure to generate optimal speeds, and the second relies on the vehicle to adjust spacing. This integration enables a more comprehensive and realistic assessment of the strategy’s impact on traffic stability and emissions, offering an innovative and applicable approach to developing smart, sustainable transportation systems.

2. VISSIM Simulation Model for the Study Area

The relationship between the deployment of autonomous vehicles and their impact on the mixed-traffic environment is complex and depends on multiple factors. This has reinforced the importance of micro simulation models in this field, which have gained increasing popularity in traffic management and transportation analysis due to their speed, safety, and feasibility compared to field implementation and testing. In this study, we selected the VISSIM 2024 platform for its outstanding capabilities in simulating complex networks and scenarios. It provides detailed modeling of various vehicle behavior settings, especially for automated vehicles, including features and attributes of ACC) vehicles that are crucial for this paper. This study focuses on a two-kilometer section of the O-1 highway through the Bosphorus Bridge in Istanbul Turkey. The observation area begins at the Yıldız interchange, where a three-lane main expressway merges with a two-lane mixed expressway and a third dedicated bus lane (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Modeled study area by VISSIM (a). Top view of study area (b).

2.1. Simulation and Evaluation Settings

The total simulation time is 5400 s, including three calibration time intervals per run. The first period is a fifteen-minute warm-up (0–900 s) to ensure the network initializes properly, followed by one hour of actual running time (900–4500 s) during which the simulation outputs are collected, and lastly concluding with fifteen minutes (4500–5400 s) for the cool-down phase at the end of the simulation period. Also, to speed up the work, we have chosen to activate these two attributes: ‘QuickMode’ and ‘UseMaxSimSpeed.’ According to Transport for London (TfL, 2010), for microsimulation modeling using VISSIM, the minimum number of simulations per scenario is 10. Furthermore, in cases of high network complexity or sensitivity, more than 10 runs may be necessary [40]. Based on that, twenty independent runs were performed for each scenario using the same initial conditions but different seeds to eliminate stochastic discrepancies; the average total time was recorded. Table 1 describes the simulation settings used.

Table 1.

VISSIM model settings.

2.2. Model Calibration and Validation

Each microscopic simulation program includes a set of parameters to calibrate the model according to specific local conditions. Therefore, it is necessary to adjust the default values of these variables to simulate driver behavior based on geographic location and driving conditions. In VISSIM, the Wiedemann car-following model is used. Two types of the Wiedemann model are included for driving behavior parameters: Wiedemann 74 (W74) and Wiedemann 99 (W99). Generally, urban arterials are modeled using the W74 model, while freeways and divergence regions are recommended for the W99 model. In this study, first, baseline calibration was performed using field data by running multiple simulations until the optimal model was identified. The methodology for parameter selection involved iterative runs, visual assessments, and comparisons to validate the model. The model was then validated using datasets other than the calibration dataset. Also, a well-established Geoffrey E. Havers (GEH) formula was employed for traffic volume calibration and validation [41].

where q represents traffic flow volume (vehicles/hour).

Table 2 presents a detailed comparison of simulated and observed traffic volumes for the study area. In addition to GEH statistics, the obtained results confirmed the success of model calibration and validation, as the values were within the acceptable range.

Table 2.

Traffic flow volume as a result of GEH Statistics for Base Model Scenario.

3. Developing a Novel VSL Strategy to Control Autonomous Vehicles

Previous studies have supported the principle of integrating or coordinating traffic control strategies, and results have shown that this approach can maximize their performance, help address congestion, and improve traffic conditions [42,43,44]. This section introduces the control strategy developed in this study, which leverages the capabilities of ACC-AVs as its core component, supported by traffic information and control strategies from existing intelligent transportation systems. The proposal is based on controlling the speed and time-gap settings to enhance traffic flow efficiency on highways by adjusting the driving behavior of ACC-AVs. One of the three key components in this proposal is the commonly utilized traffic management technique known as variable speed limits (VSL). We recommend broadening its effectiveness as a traffic control method by integrating, alongside adjustments to speed limits, time-gap recommendations to activate the time-gap-based spacing policy for low-level automated vehicles. Our research adopts an internal approach to modeling the behavior of low-level automated vehicles. This method is a simplified, widely used technique in prior studies examining the impacts of connected and automated vehicles [45]. W99 was employed to simulate the behavior of both human-driven vehicles (HDVs) and automated vehicles equipped with an adaptive cruise control system (ACC-AVs). The W99 has ten adjustable parameters, labeled CC0 through CC9. These driving behavior parameters were calibrated to represent observed conditions. Necessary modifications were applied to the car-following and lane-changing parameters. The modified parameters for each category in the internal model within VISSIM are demonstrated in Table A1 (See Appendix A).

3.1. Modeling the Variable Speed Limit Control (VSL)

Variable speed limit control is recognized as a promising method for mitigating capacity drop. Several strategies have aimed to reduce and standardize vehicle speed variations by controlling VSL limits to achieve greater stability and uniformity, thereby increasing capacity. According to several studies, the proper implementation of a variable speed limit system can indeed alleviate congestion problems caused by high-speed variations between vehicles and allow traffic to better use available capacity [46,47,48]. We select this system to be the main element in this strategy and play a vital role. For the VISSIM simulation, the first step was to develop and code the variable-speed limit algorithm. The variable-speed limit control algorithm is designed using rule-based (RB) logic [49]. This method links real-time traffic data to predefined speed limit values to trigger the operational decisions necessary for setting variable speed limits. Many previous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of this type of VSL algorithm in improving traffic congestion performance and enhancing network stability [50,51]. This logic is based on the Fundamental Diagram (FD), which illustrates the relationship between flow q, density k, and velocity v according to the equation:

q = k × v

Based on this, three operating regions have been defined: free-flow, pre-critical, and congested. The RB-VSL controller uses real-time measurements from detectors located on the mainline downstream of the merging bottleneck to estimate the traffic volume, as one detector per lane per vehicle class was defined. VisVAP, its vehicle-actuated programming (VAP) feature, was utilized to establish and implement the VSL control algorithm for our research. Also, VisVAP was used to count vehicle traffic on the mainline via the detectors. The passenger car unit (PCU) was defined based on two well-established sources: the Highway Capacity Manual (HCM) and Transport for London (TfL2010). Each vehicle was assigned a PCU value of 1.0 for passenger cars and light goods vehicles (LGV), 1.5 for medium goods vehicles (MGV), 2.0 for buses, 2.3 for heavy goods vehicles (HGV), and 3.0 for articulated buses [52]. The data were aggregated every 1 min. The result was smoothed by averaging the current 1-min result with the previous 1-min period. This is deemed an important action because it eliminates significant jumps in the results, which may occur if the vehicle flow changes suddenly due to local queuing. The equation below shows the calculation of Qb, which is the sum of all current flows at the end of each evaluation period of 1 min, as Qv denotes the current and previous volumes were measured for each vehicle class, taking into account the PCU factor.

where v1 = Car, v2 = Heavy vehicle, v3 = Metro bus, v4 = Bus, and v5 = Mini bus.

On the other hand, VSL signs were modeled using desired speed decisions (DSD); two sets of DSDs were placed in the network. The first one was on the mainline near the loading point, and the second one was after the merge. Both are updated simultaneously. The mainline speed limit is updated each minute based on the outputs of the VisVAP calculation. IF-THEN rules would map measured traffic volumes to appropriate speed limit actions. With low traffic volume, the maximum speed limit would be displayed to maintain a high throughput. As the traffic volume approaches its critical level, the speed will be reduced to v2 to regulate upstream flow. Once the volumes exceed the critical value, the minimum speed v1 would be applied to prevent further traffic breakdown at the bottleneck point. Hence, the estimated volume serves as the primary state variable for triggering rule-based speed limit decisions. (See Table 3). Visvap’s Set_des_speed (…) function was used to update the desired speed decisions every minute based on the volume thresholds.

Table 3.

Assumed parameters and critical volumes for the developed variable speed limit VSL algorithm.

The rule-based algorithm developed in this study for variable speed limit control is displayed as pseudo-code and is attached in Appendix B.

3.2. Modeling (Time-Gap Recommendation Strategy)

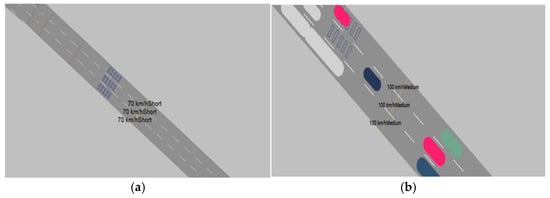

First, three time distribution categories were defined to represent the short, medium, and long settings: 0.8 s, 1.5 s, and 2.2 s. The inputs were extracted from ISO (2010) [53]. In VISSIM 2024, there is a feature called ‘Attribute Modification,’ which allows the user to update certain object attributes during the simulation. We used this feature to update the CC1 parameter concurrently with the speed limit update, and the object filter was activated to apply the gap-time distribution updates only to ACC-AV vehicles. Regarding the time gap setting recommended in this study, we selected the minimum gap setting to take advantage of the ACC-AVs’ ability to implement short-time gaps, as several studies have indicated that using minimum time gap parameter settings in autonomous vehicles can greatly enhance traffic conditions [54] (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Visualization of the micro-simulation model: (a) Proposed strategy, (b) Modified VSL model.

3.3. Simulation Scenarios

After completing the modeling of the main elements of the proposed strategy, it was necessary to determine the appropriate mechanism for its implementation. This section presents four scenarios that were tested based on the traffic control strategies included in each, either individually or collectively. Examining the results for each case is a crucial step in assessing the contribution of each measure. Previous studies have confirmed that the effect of specific gaps in the adaptive speed control system on total flow and power will be very limited at low spread rates (<40). Whereas the effect of gaps becomes clear and direct at high spread rates >60 [55,56]. In this study, each scenario was evaluated with varying ACC vehicle penetration rates, ranging from 30% to 80% of the total number of vehicles. The penetration rate represents the percentage of vehicles whose longitudinal movement is controlled by ACC activation, not the percentage of vehicles equipped with the technology. Therefore, the remaining traffic consists of human-driven vehicles (HVs), including conventional vehicles not equipped with adaptive cruise control (ACC) and those equipped with it but whose drivers do not activate it. In Table 4, the selected policies for each scenario are summarized by control case.

Table 4.

Simulation scenarios and their corresponding control configurations.

3.4. Scenario 1: No Traffic Control

In scenario 1, no control policies are implemented, and the time gaps in ACC-AVs are determined randomly by the driver’s preference. First, the deployment rate of autonomous vehicles starts from zero, with all vehicles being manually driven. This scenario was mentioned in the calibration section, where the observed data were entered. This scenario was calibrated and verified, and it accurately reflects real-world traffic conditions. After 20 repetitions, the average vehicle delay (AVD) for all vehicles (s/veh) and the total fuel consumption (liter) were determined to be 44.50 s and 229 L, the resulting emissions, namely carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen oxides (NOx), and volatile organic com-pounds (VOC), were also calculated in grams and amounted to 16,005, 3114, 3709, respectively. Previous studies have confirmed that introducing ACC-AVs with uncontrolled gap values can reduce overall traffic flow efficiency [57]. To study this issue, we tested different (ACC) penetration rates, ranging from 30% to 80%. The randomly measured ACC gap values ranged from 0.8 to 2.2 s, with an average higher than the calibrated value for manual vehicles. Simulations were run using the ACC-AVs penetration rates (PRs). Lastly, the average vehicle delay, total fuel consumption, and emissions for each PR were averaged over 20 iterations. It must be noted here that, due to the model is congested, and the emergence of some outliers that could distort the results, the number of simulations was increased to enhance accuracy and reliability, despite the obvious improvements

3.5. Scenario 2: Variable Speed Limit (VSL) Control Strategy

The existing variable-speed limit strategy and different penetration rates of ACC-equipped vehicles were implemented. Also, three categories of time gaps are modeled using random distributions to represent different driver preferences. This simulates the actual form of VSL and the way of ACC vehicles currently operate, for comparison with the approach proposed in this study. We examine the implementation of the VSL, which affects the network individually, without utilizing any other components. Based on traffic volume thresholds for each speed, the VSL algorithm dynamically adjusts speed restrictions. For time gaps, there is no enforcement of rules, so drivers choose their time gaps randomly from three typical options (short, medium, and long) displayed by the system, typically ranging from 0.8 to 2.2 s. Additionally, we must note that drivers’ adherence to speed limits is a crucial factor in the success of this strategy. For VSL, adherence is the condition in which the vehicle’s speed during that time period is equal to or less than the limit displayed on the sign [58,59]. This study assumes drivers fully adhere to the imposed speed limits.

3.6. Scenario 3: Time-Gap Recommendation Strategy (TGR) Based on Spacing Policy

In this scenario, the strategy of recommending short time-gap settings for ACC vehicles was tested by applying it individually, without any other strategies or restrictions. Four deployment ratios were assumed to represent vehicles that actually use the ACC longitudinal control system during operation. Variable message signs will provide drivers with the required time gap settings. This study assumes full driver adherence to the recommended settings. Regarding the recommended time-gap pattern, short time gaps have traditionally been among the most important features of autonomous vehicles, as they have a noticeable impact on traffic characteristics Therefore, we set the proposed time gap to the minimum (short) pattern, approximately 0.8 s. To verify the impact of the time gap recommendation policy and demonstrate its effectiveness.

3.7. Scenario 4: Integrated Control Strategy for Operating Variable Speed Limits Based on AV Spacing Policy

This is a full-control situation, as scenario 4 combines cases 2 and 3, integrating the variable-speed limit with the time-gap recommendation strategy. The first objective in this strategy is to reduce the large variation in speed differences, mitigating lane-change maneuvers and shock waves. VSL is a core element in the suggested integrated control strategy. The main role of this VSL was to harmonize speed differences and stabilize traffic flow. A variable-speed limit strategy helps reduce the deterioration caused by the introduction of ACC-AVs. The second objective of the proposed strategy is to regulate the time gaps by recommending the proper mode. To achieve this goal, the ACC’s feature, the spacing policy, should be activated and supported by the Variable Message Signs (VMS) system to provide drivers with information on the time gap pattern to apply. In this study, ACC’s drivers were asked to set the gap mode and select a “short” mode (0.8 s) to avoid long and medium gaps. Accordingly, four different AV penetration rates are tested for vehicles equipped with the ACC system. A variable speed limit is applied in conjunction with a recommendation to set a short time gap setting. Drivers will receive instructions on speed and time-gap settings via variable message signs. This scenario assumes that ACC vehicle drivers will adhere to the displayed setting recommendations.

4. Results and Discussions

This paper proposes a new operational strategy to maximize the benefits of the variable-speed limit strategy and expand its impact by coordinating its operation with the spacing policy mechanism adopted by autonomous vehicles at various levels, particularly at lower levels. This section presents the results of the scenarios tested in this study, discusses the effectiveness of the approach followed, and demonstrates its impact through an integrated assessment of traffic efficiency and the environmental dimension. This approach relies on developing a simplified operational strategy that employs the control systems available in the intelligent transportation system, along with the automated vehicle technologies already on the market, as effective basic elements, without requiring advanced communication technologies or additional infrastructure. The first element will be the well-established variable-speed limit system, which has proven effective at standardizing and harmonizing speeds on highways and in bottleneck areas. The second element will be Variable Message Signs (VMS), which provide drivers with information about speed and the time-gap settings to be configured in their vehicles. As drivers adjust their speed limits and recommended time-gap settings via the ACC interface in their vehicles based on information displayed on the VMS boards across the controlled network. The third element will be vehicles equipped with adaptive cruise control, which are widely available. The capabilities of ACC are used to adapt the driving behavior of vehicles equipped with this system; its spacing policy feature adjusts the time gaps between vehicles in the network. It is important to note here the vital role that driver commitment will play in this strategy. It is essential to highlight the vital role of driver compliance in achieving the desired gains from the proposed strategy. This compliance will be demonstrated through adherence to speed limits and the recommended time gap pattern, which must be adjusted via the adaptive cruise control interface settings in their vehicles. The scenarios tested in this study assume full driver compliance. In this regard, four scenarios were conducted, using several performance metrics to evaluate the effectiveness of the control strategies both individually and collectively. The results demonstrated the superiority of the proposed strategy, which achieved significant reductions in delay rates, the number of stops, fuel consumption, and emissions, directly proportional to the increase in the penetration rate of autonomous vehicles. The following sections explain the strategy’s impact on the measured parameters.

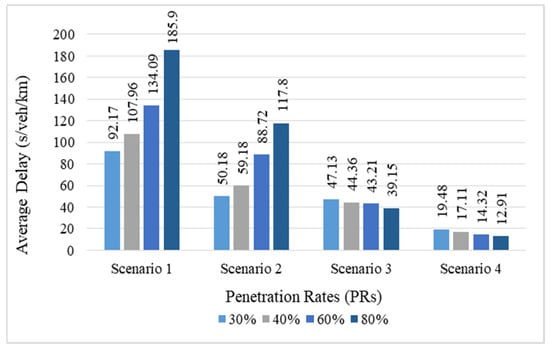

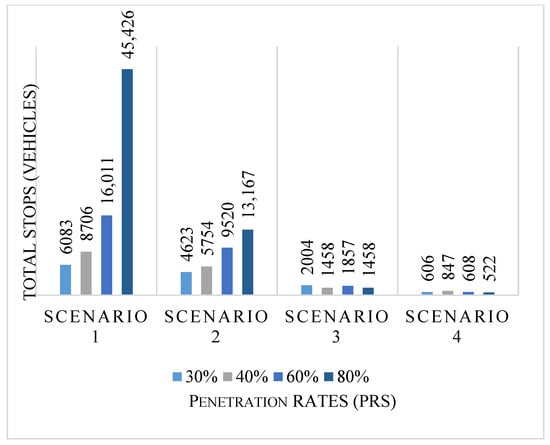

4.1. Average Delay and Total Stops

Table 5 summarizes the average delay (sec) and the total number of network interruptions (Total number of stops) for each scenario and at different penetration rates. Scenario 1 recorded the highest delay rates, which increased with greater autonomous vehicle penetration. Although there is stability in flow, the increase in the proportion of ACC-AVs using long or medium time gaps is causing a capacity loss that has led to more delay. In addition to AVs’ typically less aggressive driving behavior, which tends to follow the preceding vehicle, regular vehicles use a lane-change maneuver to move to a faster lane. Therefore, deterioration increases continuously with the growing prevalence of motor vehicles, along with other factors related to speed variations, which lead to more braking maneuvers and are evident in the higher number of stops in this scenario. This is further compounded by other factors and problems inherent to mixed traffic. The results show that as the ACC-AV penetration rate increases, the average of all measured parameters also increases. For example, the percentage increase in the delay rate ranged from 51% to 76% compared to the calibrated scenario, which means traffic conditions are getting worse. This finding supports the earlier hypothesis, based on previous research showing that, compared to conventional vehicles, random gaps in uncontrolled ACC-AVs will result in decreased capacity and worsened traffic conditions. In scenario 2, implementing a variable speed limit reduced delays by up to 37% and total stops by 71% compared to the no-traffic control scenario. This demonstrates the effectiveness of VSL in coordinating speeds and limiting course-change maneuvers through speed uniformity. But with the continued presence of long- and medium-term gaps, delay rates still increase as the penetration rate of ACC-AVs rises. According to scenario 3, the recommended gap strategy significantly reduced delays by 49% to 79% and total stops by 67% to 97% with AV penetration. This indicates that maintaining short gaps between vehicles improved capacity and road throughput, especially during congestion. However, some delay has persisted, and the number of stops has fluctuated due to string instability and speed variability. Our results are consistent with recent literature, which emphasizes that achieving dynamic stability in mixed traffic environments, which include conventional vehicles and others equipped with Adaptive Cruise Control (ACC) systems, depends critically on how these systems handle the minimum time gap. Although reducing the time gap to around 0.8 s increases capacity, this option may, in mixed traffic, amplify speed disturbances and spread deceleration waves due to differences in response times between human drivers and automated vehicles, causing instability in the traffic chain. In a related context, the integrated strategy combining the variable speed limit with the recommended time gap policy outperformed all scenarios, including scenario 3. The addition of a variable speed limit contributed to traffic stability and reduced volatility by smoothing out speed variations between lanes. This, in turn, reduced lane-changing maneuvers and sudden braking waves, thereby improving traffic flow stability. Furthermore, the increased capacity resulting from shorter gaps improved overall network performance. In particular, reducing delays by approximately 79–93% and total stops by 83–98%, compared to the no-control scenario (see Figure 3 and Figure 4).ACC, which are distinguished from traditional vehicles by their ability to maintain constant time gaps at all speeds, has contributed to facilitating the adoption of the short gap and benefiting from its advantages on capacity.

Table 5.

Average delays and total stops among scenarios.

Figure 3.

Comparison of Average Vehicle Delay among Scenarios at Different Penetration Rates (PRs).

Figure 4.

Comparison of Total Stops among Scenarios at Different Penetration Rates (PRs).

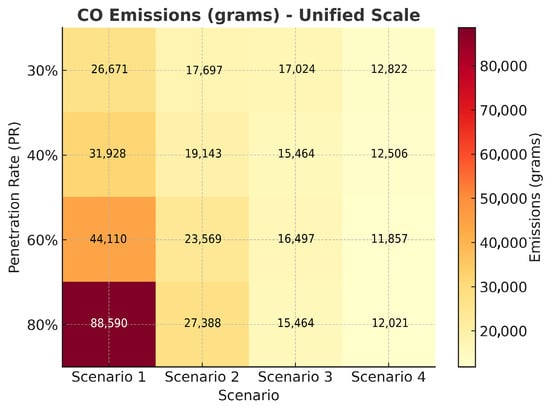

4.2. Fuel Consumption and Emissions

The environmental dimension is a crucial factor in developing sustainable transport systems. Established environmental pollution indicators, such as emissions and fuel consumption, are used as important benchmarks for evaluating the performance of different systems and strategies. In this research, the performance of each scenario and its environmental impact were evaluated by measuring fuel consumption and emissions, as shown in Table 6, Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9, where the results of carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, and volatile organic compounds emissions, as well as fuel consumption, are included. The rate of reduction in emissions ranged between 52% and 86%.

Table 6.

CO Emissions (grams).

Table 7.

NOX Emissions (grams).

Table 8.

VOC Emissions (grams).

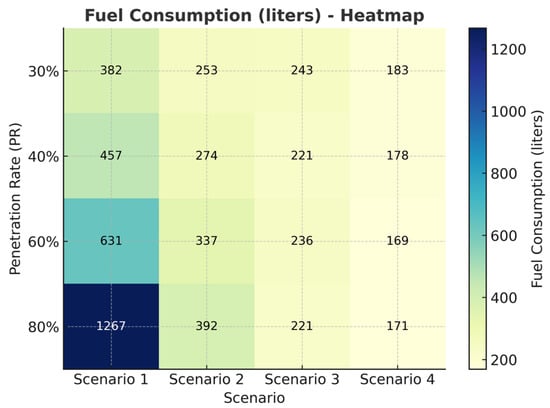

Table 9.

Fuel consumption (liters).

Also, when observing the heat maps below, we find that the first scenario recorded the highest percentages across all metrics, whereas in the second scenario, the VSL strategy contributed to a significant improvement over the first. However, fuel consumption and emissions continued to increase as autonomous vehicles became more widespread, a natural consequence of differences in response and maneuver execution rates between traditional drivers and self-driving vehicles. In the third scenario, the results fluctuated between rising and falling due to the chain’s instability. In the fourth scenario, we see the effect of the integrated strategy through the noticeable decrease that coincides with the increased spread of automated vehicles, with a continuous and clear difference compared to the state of no control (See Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8). This illustrates how the integrated strategy contributed to reducing acceleration processes, which, in turn, led to reduced fuel consumption and emissions. Our results confirm what many studies have shown: that higher acceleration rates significantly increase vehicle emissions [60,61].

Figure 5.

Carbon Monoxide (CO) emissions heat-map of the entire network for all vehicles.

Figure 6.

Nitrogen Oxides (NOx) emissions heat-map of the entire network for all vehicles.

Figure 7.

Volatile Organic Compounds (VOC) emissions heat-map of the entire network for all vehicles.

Figure 8.

Heat-map for fuel consumption of the entire network for all vehicles.

The first scenario shows high fuel consumption that increases with the increasing penetration rates of (ACC-AVs); in contrast, the fourth scenario, which implements the proposed integrated strategy, maintains significantly low fuel consumption and emissions in a continuous form with penetration rates. The reduction is about 52% 87% compared to the no-control scenario and 56% to 28% compared to the typical VSL scenario. Therefore, scenario 4 clearly represents the best option in terms of network efficiency and operational and environmental improvements.

5. Conclusions

This research presents a modern coordination framework that develops an integrated control strategy linking Variable Speed Limits (VSL) with spacing policies for vehicles equipped with Adaptive Cruise Control (ACC). From this perspective, we developed a new strategy for operating variable-speed limits to determine the appropriate time-gap pattern for ACC-AV vehicles and thereby improve their performance. The proposed model provides an integrated operational strategy that uses the same requirements as the existing VSL model. After conducting simulations and gradually increasing the penetration rates of ACC-AVs, we conclude that the proposed VSL strategy framework significantly improves traffic efficiency, especially as autonomous vehicle penetration rates increase. This confirms the hypothesis that deploying these vehicles with an appropriate control policy can improve speeds and mitigate shock wave propagation and traffic oscillations. The promising results of the proposed model are noteworthy. The measured parameters showed significant improvements compared to the no-control condition. The results showed that this approach has helped reduce delays, emissions, and fuel consumption, and it also improves overall traffic flow. However, other practical requirements must also be considered. This paper aims to develop integrated strategies that leverage the features of ACC vehicles, especially their ability to maintain a stable short gap, and to demonstrate the extent to which this pattern can be adopted and the supporting conditions required to achieve it. For example, the drivers’ full commitment, which is a key factor in the results. Since this study did not address drivers’ noncompliance, future research may explore the effects of implementing the strategy under different conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S.A., M.K., and M.E.; data curation, R.S.A., M.K., and M.E.; formal analysis, R.S.A., M.K., and M.E.; investigation, R.S.A., M.K., and M.E.; methodology, R.S.A., M.K., and M.E.; software, R.S.A.; validation, R.S.A., M.K., and M.E.; resources, R.S.A., M.K., and M.E.; visualization, R.S.A.; writing—original draft preparation, R.S.A.; writing—review and editing, M.K. and M.E.; supervision, M.K. and M.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the conclusions of this study are available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This study is part of the thesis by the corresponding author from Istanbul Gelişim University, Turkey. We thank the PTV group (Germany) for providing an unlimited, thesis-based version of the VISSIM software.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VSL | Variable Speed Limit Control |

| ACC | Adaptive Cruise Control |

| VisVAP | vehicle-actuated programming |

| CACC | Cooperative Adaptive Cruise Control |

| SAE | Society of Automotive Engineers |

| AV | Automated Vehicles |

| CS | Constant Spacing |

| CTG | Constant Time Gap |

| VTG | Variable Time Gap |

| ITS | Intelligent Transportation System |

| VMS | Variable Message Signs |

| TfL | Transport for London |

| HDVs | human-driven vehicles |

| GEH | Geoffrey E. Havers |

| HCM | Highway Capacity Manual |

| LOS | Level of Service (Grade A–F based on Highway Capacity Manual (HCM)) |

| PCU | Passenger Car Unit |

| TGR | Time-gap Recommendation |

| PR | Penetration Rate |

| AVD | Average Vehicle Delay (in sec for all vehicles) |

| CO | Carbon Monoxide (grams). |

| NOx | Nitrogen Oxides (grams). |

| VOC | Volatile Organic Compounds (grams). |

| TFC | Total Fuel Consumption (liter). |

| # of Stops | Total Stops for all vehicles (total number). |

| ADAS | Advanced Driver Assistance Systems |

Appendix A

Table A1.

The modified parameters of driving behavior for each category in the internal model within VISSIM.

Table A1.

The modified parameters of driving behavior for each category in the internal model within VISSIM.

| Driving Behavior | Parameters | HDVs Freeway | HDVs Merging | Metro Bus Freeway | Metro Bus Merging | ACC-AVs Freeway | ACC-AVsMerging |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Following Parameters | Look ahead distance(m) | 0.00–250 | 0.00–250 | 0.00–250 | 0.00–250 | 0.00–250 | 0.00–250 |

| Look-back distance (m) | 0.00–150 | 0.00–150 | 0.00–150 | 0.00–150 | 0.00–150 | 0.00–150 | |

| Number of interacting objects | 2 | 6 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 4 | |

| Car following Parameters | CC0 | 1.5 m | 1.5 m | 1.5 m | 0.7 m | 0.7 m | 1.5 m |

| CC1 | 0.9 s | 0.4 s | 0.9 s | 0.4 s | 0.8 s | 0.8 s | |

| CC2 | 4.0 m | 4.0 m | 3.0 m | 3.0 m | 0.0 m | 0.0 m | |

| CC3 | −8.0 s | −8.0 s | −8.0 s | −8.0 s | −8.0 s | −8.0 s | |

| CC4 | −0.10 | −0.10 | −0.10 | −0.10 | −0.10 | −0.10 | |

| CC5 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | |

| CC6 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| CC7 | 0.10 m/s2 | 0.10 m/s2 | 0.10 m/s2 | 0.10 m/s2 | 0.10 m/s2 | 0.10 m/s2 | |

| CC8 | 3.5 m/s2 | 3.5 m/s2 | 3.5 m/s2 | 3.5 m/s2 | 3.5 m/s2 | 3.5 m/s2 | |

| CC9 | 1.5 m/s2 | 1.5 m/s2 | 1.5 m/s2 | 1.5 m/s2 | 1.5 m/s2 | 1.5 m/s2 | |

| lane change Parameters | Maximum deceleration, own vehicle (m/s2) | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.00 | 4.00 | −4.00 | −4.00 |

| Maximum deceleration, trailing vehicle (m/s2) | 3.0 | 3.0 | 4.5 | 4.5 | −3.00 | −3.00 | |

| −1 m/s2 per distance, own vehicle and trailing vehicle (m) | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | |

| Accepted deceleration, own vehicle (m/s2) | −1.0 | −0.8 | −1.0 | −1.0 | −1.0 | −1.0 | |

| Accepted deceleration, trailing vehicle (m/s2) | −1.0 | −1.5 | −1.5 | −1.5 | −0.5 | −0.5 | |

| Waiting time before diffusion (s) | 60 | 120.0 | 120.0 | 120.0 | 60.0 | 60.0 | |

| Minimum Clearance, front/rear (m) | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| Safety distance reduction factor | 0.6 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.6 | 0.6 | |

| Maximum deceleration for cooperative braking (m/s2) | −3.0 | −3.5 | −5.0 | −5.0 | −3.0 | −3.0 | |

| Zipper Merging (s) | Not activated | activated | Not activated | activated | Not activated | activated | |

| Cooperative lane change | activated | activated | activated | activated | activated | activated | |

| Maximum collision time (s) | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | |

| Maximum speed difference (km/h) | 15 | 30.0 | 30.0 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 50.0 | |

| lateral | Observe adjacent lanes | activated | activated | activated | activated | activated | activated |

| Collision time gain (s) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

Appendix B

The pseudo-code of the rule-based algorithm created in this study for variable speed limit control.

- Define constants: PCU_HGV, PCU_BusMetro, PCU_BusNormal, PCU_BusMini.

- Define smoothing factor ALFA ∈ (0, 1].

- Define flow thresholds (e.g., Qat120ToDecSp).

- Define evaluation interval IntervalLength (seconds).

- If init = 0 (first run):

- Set initial desired speeds (km/h): Lights = 120, ACC = 120, Heavy vehicles = 100, Metro buses = 80.

- Apply speeds to vehicle groups.

- Measure and store initial flow rates as previous values: qCarPrev, qHGVPrev, qBusMetroPrev, qBusNormalPrev, qBusMiniPrev.

- Start periodic evaluation timer with interval IntervalLength.

- Set init←1.

- Every evaluation period (IntervalLength): Measure current flow rates: qCar, qHGV, qBusMetro, qBusNormal, qBusMini.

- Apply Exponential Moving Average (EMA): qCarZ = ALFA × qCar + (1 − ALFA) × qCarPrev; qHGVZ = ALFA × qHGV + (1 − ALFA) × qHGVPrev; qBusMetroZ = ALFA × qBusMetro + (1 − ALFA) × qBusMetroPrev; qBusNormalZ = ALFA × qBusNormal + (1 − ALFA) × qBusNormalPrev; qBusMiniZ = ALFA × qBusMini + (1 − ALFA) × qBusMiniPrev.

- Compute total equivalent flow: Qb = qCarZ + (PCU_HGV × qHGVZ) + (PCU_BusMetro × qBusMetroZ) + (PCU_BusNormal × qBusNormalZ) + (PCU_BusMini × qBusMiniZ).

- Record Qb and individual smoothed flows.

- If v_des_Light ≥ 120 then:

- If Qb > Qat120ToDecSp, reduce speeds: Lights = 100, ACC = 100, others adjusted proportionally.

- Apply new speeds to all vehicle groups.

- Else: maintain current speeds.

- Else: apply lower-tier adjustment rules (e.g., 100→80 km/h).

- Update previous flow values: qCarPrev←qCar; qHGVPrev←qHGV; qBusMetroPrev←qBusMetro; qBusNormalPrev←qBusNormal; qBusMiniPrev←qBusMini

References

- Society of Automotive Engineers J3016: Taxonomy and Definitions for Terms Related to Driving Automation Systems for On-Road Motor Vehicles. 2021. Available online: https://www.sae.org/standards/content/j3016_202104/ (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Alshabibi, N.M. Impact Assessment of Integrating AVs in Optimizing Urban Traffic Operations for Sustainable Transportation Planning in Riyadh. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louati, A.; Louati, H.; Kariri, E. Harmonized Autonomous–Human Vehicles via Simulation for Emissions Reduction in Riyadh City. Futur. Internet 2025, 17, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Liu, D.; Wu, S.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zou, Y. Enhancing Mixed Traffic Flow with Platoon Control and Lane Management for Connected and Autonomous Vehicles. Sensors 2025, 25, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, R.; James, R.; Melson, C.L.; Hu, J.; Bared, J. Characterizing the Impact of Production Adaptive Cruise Control on Traffic Flow: An Investigation. Transp. B Transp. Dyn. 2018, 7, 992–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosca, M.A.; Oprea, F.C.; Dragu, V.; Dinu, O.M.; Costea, I.; Burciu, S. Evaluating the impact of automated vehicle penetration on traffic flow: A microsimulation-based approach. Systems 2025, 13, 751. [Google Scholar]

- Makridis, M.; Mattas, K.; Ciuffo, B. Response Time and Time Headway of an Adaptive Cruise Control. An Empirical Characterization and Potential Impacts on Road Capacity. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 21, 1677–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, T.; Liu, J.; Qin, X.; Yu, S. Effects of vehicle gap changes on fuel economy and emission performance of the traffic flow in the ACC strategy. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Jiang, R.; He, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Li, L.; Liu, R.; Chen, X. Automated vehicle-involved traffic flow studies: A survey of assumptions, models, speculations and perspectives. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021, 127, 103101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleiman, G.M.; Bezgin, N.Ö.; Ergun, M.; Gürsoy, M.; Karaşahin, M. Effects of speed management and roadway parameters on traffic flow along arterials. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Transp. 2017, 170, 346–362. [Google Scholar]

- Nezamuddin, N.; Jiang, N.; Zhang, T.; Waller, S.T.; Sun, D. Traffic Operations and Safety Benefits of Active Traffic Strategies on TxDOT Freeways; Technical Report; The University of Texas at Austin: Austin, TX, USA, 2011; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, P.Y.J.; Chen, S.; Dong, J.; Du, R.; Li, Y.; Labi, S. Leveraging the Capabilities of Connected and Autonomous Vehicles and Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning to Mitigate Highway Bottleneck Congestion. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.05436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamin, A.E. Optimal Differential Variable Speed Limit Control in a Connected and Autonomous Vehicle Environment for Freeway Off-Ramp Bottlenecks. J. Transp. Eng. Part A Syst. 2023, 149, 04023009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L. Cooperative Adaptive Cruise Control Vehicles on Highways: Modelling and Traffic Flow Characteristics. Ph.D. Thesis, TU Delft Transport and Planning, Delft, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.-F.; Gao, Z.-Y.; Zhao, X.-M. The effect of ACC vehicles to mixed traffic flow consisting of manual and ACC vehicles. Chin. Phys. B 2008, 17, 4440–4445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aittoniemi, E. Evidence on impacts of automated vehicles on traffic flow efficiency and emissions: Systematic review. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 16, 1306–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shladover, S.E.; Nowakowski, C.; Lu, X.Y.; Hoogendoorn, R. Using Cooperative Adaptive Cruise Control (CACC) to Form High-Performance Vehicle Streams; UC Berkeley: California Partners for Advanced Transportation Technology: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Postigo, I.; Olstam, J.; Rydergren, C. Effects on traffic performance due to heterogeneity of automated vehicles on motorways: A microscopic simulation study. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Vehicle Technology and Intelligent Transport Systems, Online, 28–30 April 2021; SciTePress: Setúbal, Portugal, 2021; pp. 142–151. [Google Scholar]

- Ntousakis, I.A.; Nikolos, I.K.; Papageorgiou, M. On microscopic modelling of adaptive cruise control systems. Transp. Res. Procedia 2015, 6, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suweda, I.W. Time headway analysis to determine the road capacity. J. Spektran 2016, 42, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Mathew, T. Fundamental Parameters of Traffic Flow; IIT Bombay: Mumbai, India, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Milanés, V.; Shladover, S.E.; Ferlis, R.; Laabs, G.; Nowakowski, C.; Kawazoe, H.; Nakamura, M. Cooperative Adaptive Cruise Control in Real Traffic Scenarios. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2014, 15, 296–303. [Google Scholar]

- Treiber, M.; Kesting, A. Traffic Flow Dynamics: Data, Models and Simulation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- van Arem, B.; van Driel, C.J.; Visser, R. The impact of cooperative adaptive cruise control on traffic-flow characteristics. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2006, 7, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Li, X.; Sai, Y.; Carrese, S.; Di Luca, L. Evaluation of throughput in ACC-equipped traffic using behaviorally plausible models. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.05380. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, M.; Wang, X.; Wang, X. Car-following headways in different driving situations: A naturalistic driving study. In Proceedings of the 16th COTA International Conference of Transportation Professionals, Shanghai, China, 6–9 July 2016; pp. 1419–1428. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Rakha, H.A. Feedback control speed harmonization algorithm: Methodology and preliminary testing. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2017, 81, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L.; Hu, J.; Dong, Y. Speed harmonization with enhanced precision. J. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Lian, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Qian, R.; Li, D.; Zheng, J. Anti-bullying Adaptive Cruise Control: A proactive right-of-way protection approach. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.12197. [Google Scholar]

- El-Baklish, S.K.; Kouvelas, A.; Makridis, M.A. Driving towards stability and efficiency: A variable time gap strategy for Adaptive Cruise Control. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2025, 174, 105074. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; Xu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Fu, C.; Li, K.; Hu, M. Spacing policies for adaptive cruise control: A survey. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 50149–50162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Willigen, W.H.; Schut, M.C.; Kester, L.J. Approximating safe spacing policies for adaptive cruise control strategies. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE Vehicular Networking Conference (VNC), Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 14–16 November 2011; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Ioannou, P. Adaptive vehicle following control system with variable time headways. In Proceedings of the 44th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, Seville, Spain, 15 December 2005; pp. 3880–3885. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Rajamani, R. Should adaptive cruise-control systems be designed to maintain a constant time gap between vehicles? IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2004, 53, 1480–1490. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Oya, M.; El Kamel, A. A safety spacing policy and its impact on highway traffic flow. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium, Xi’an, China, 3–5 June 2009; pp. 960–965. [Google Scholar]

- Kanellakopoulos, I.; Nelson, P.; Stafsudd, O. Intelligent sensors and control for commercial vehicle automation. Annu. Rev. Control. 1999, 23, 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, W.; Liu, S.; Xiang, Y. Reducing the risk of rear-end collisions with infrastructure-to-vehicle integration of variable speed limit control and adaptive cruise control system. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2016, 17, 745–752. [Google Scholar]

- Fondzenyuy, S.K. The impact of speed limit change on emissions: A systematic review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakowski, C.; Shladover, S.E.; Cody, D.; Bu, F.; O’Connell, J.; Spring, J.; Dickey, S.; Nelson, D. Cooperative Adaptive Cruise Control: Testing Drivers’ Choices of Following Distances; UC Berkeley ITS Research Center: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Transport for London. Microsimulation Modelling Guidelines; Version 1.0; Transport for London: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, O. The GEH measure and quality of the highway assignment models. In Proceedings of the European Transport Conference, Salzburg, Austria, 7–11 October 2012; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Aty, M.; Haleem, K.; Cunningham, R.; Gayah, V. Application of variable speed limits and ramp metering to improve safety and efficiency of freeways. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium on Freeway and Tollway Operations, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–24 June 2009; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Dadashzadeh, N.; Ergun, M. An integrated variable speed limit and ALINEA ramp metering model in the presence of high bus volume. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Yang, X.T.; Zhang, L.; Lee, M.; Zhou, W.; Raqib, M. An integrated modeling framework for active traffic management and its applications in the Washington, DC area. J. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 25, 609–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidler, V.; Buck, H.S.; Kautzsch, L.; Vortisch, P.; Weyland, C.M. Simulation of autonomous vehicles based on Wiedemann’s car following model in PTV vissim. In Proceedings of the 98th Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board (TRB), Washington, DC, USA, 13 January 2019; pp. 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgiou, M.; Kosmatopoulos, E.; Papamichail, I. Effects of Variable Speed Limits on Motorway Traffic Flow. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2008, 2047, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Ahn, S. Variable speed limit control for severe non-recurrent freeway bottlenecks. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2015, 51, 210–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, M.L.; Chang, G.-L. Applications of Variable Speed Control for Contending with Recurrent Highway Congestion. 2014. Available online: https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/27725 (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Lin, P.-W.; Chang, G.-L. A general rule-based variable speed limit control strategy for freeway bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the TRB Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, USA, 11–15 January 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Aty, M.; Cunningham, R.J.; Gayah, V.V.; Hsia, L. Dynamic variable speed limit strategies for real-time crash risk reduction on freeways. Transp. Res. Rec. 2008, 2078, 108–116. [Google Scholar]

- Khondaker, B.; Kattan, L. Variable speed limit: A microscopic analysis in a connected vehicle environment. Transp. Res. Part C 2015, 58, 146–159. [Google Scholar]

- Transportation Research Board. Highway Capacity Manual; Transportation Research Board: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 15622:2010; Intelligent Transport Systems—Adaptive Cruise Control Systems—Performance Requirements and Test Procedures. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- Manolis, D.; Spiliopoulou, A.; Vandorou, F.; Papageorgiou, M. Real time adaptive cruise control strategy for motorways. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2020, 115, 102617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, D.; Horváth, B. Vehicle automation impact on traffic flow and stability: A review of literature. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2023, 20, 132–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Lee, J.; Mao, S. Effects of Adaptive Cruise Control System on Traffic Flow and Safety Considering Various Combinations of Front Truck and Rear Passenger Car Situations. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2024, 2678, 1009–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korbmacher, R.; Khound, P.; Tordeux, A. Understanding Collective Stability of ACC Systems: From Theory to Real-World Observations. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.04530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Edara, P.; Sun, C. Speed limit effectiveness in short-term rural interstate work zones. Transp. Lett. 2013, 5, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, R.A.; Fontaine, M.D.; Khattak, Z.H. Driver response to variable speed limits on I-66 in northern Virginia. J. Transp. Eng. Part A Syst. 2019, 145, 04019021. [Google Scholar]

- Rakha, H.; Ding, Y. Impact of stops on vehicle fuel consumption and emissions. J. Transp. Eng. 2003, 129, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, K.; Rakha, H.; Trani, A.; Van Aerde, M. Estimating vehicle fuel consumption and emissions based on instantaneous speed and acceleration levels. J. Transp. Eng. 2002, 128, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.