Spatial and Temporal Unevenness in the Operation of Urban Public Transport and Parking Spaces

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methods

2.2. Study of the Unevenness of Passenger Volume over Time

- Developing long-term adaptive strategies based on long-term trends;

- Creating flexible response mechanisms within the acceptable subset of Ur;

- Integrating forecasting models into planning processes.

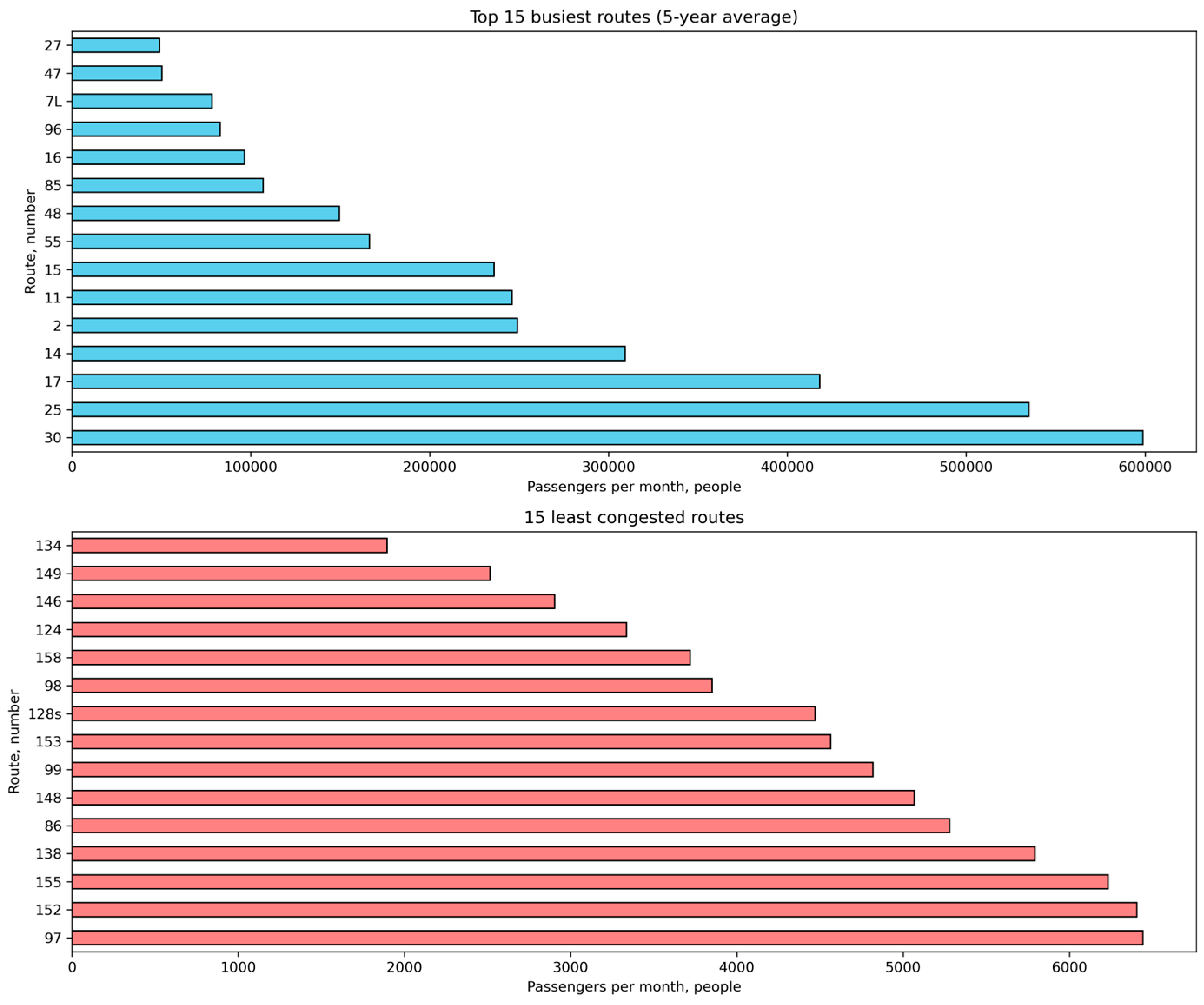

- “Very High Load”—routes in the upper quartile (75–100%), with the highest number of passengers transported by urban public transport, for which xi ∈ (Q3, +∾), that is xi > q0.75;

- “High Load”—routes in the 50–75% quantile, for which xi ∈ (Q2, Q3), that is q0.5 < xi ≤ q0.75;

- “Medium Load”—routes with the passenger volume in the 25–50% range, for which xi ∈ (Q1, Q2), that is q0.25 < xi ≤ q0.5;

- “Low Load”—routes in the lower quartile (0–25%), having a minimal number of passengers transported by urban public transport, for which xi ∈ (−∾, Q1), that is, xi ≤ q0.25.

2.3. Study of the Unevenness of Parking Space Operation over Time

2.4. Research Hypothesis

3. Results

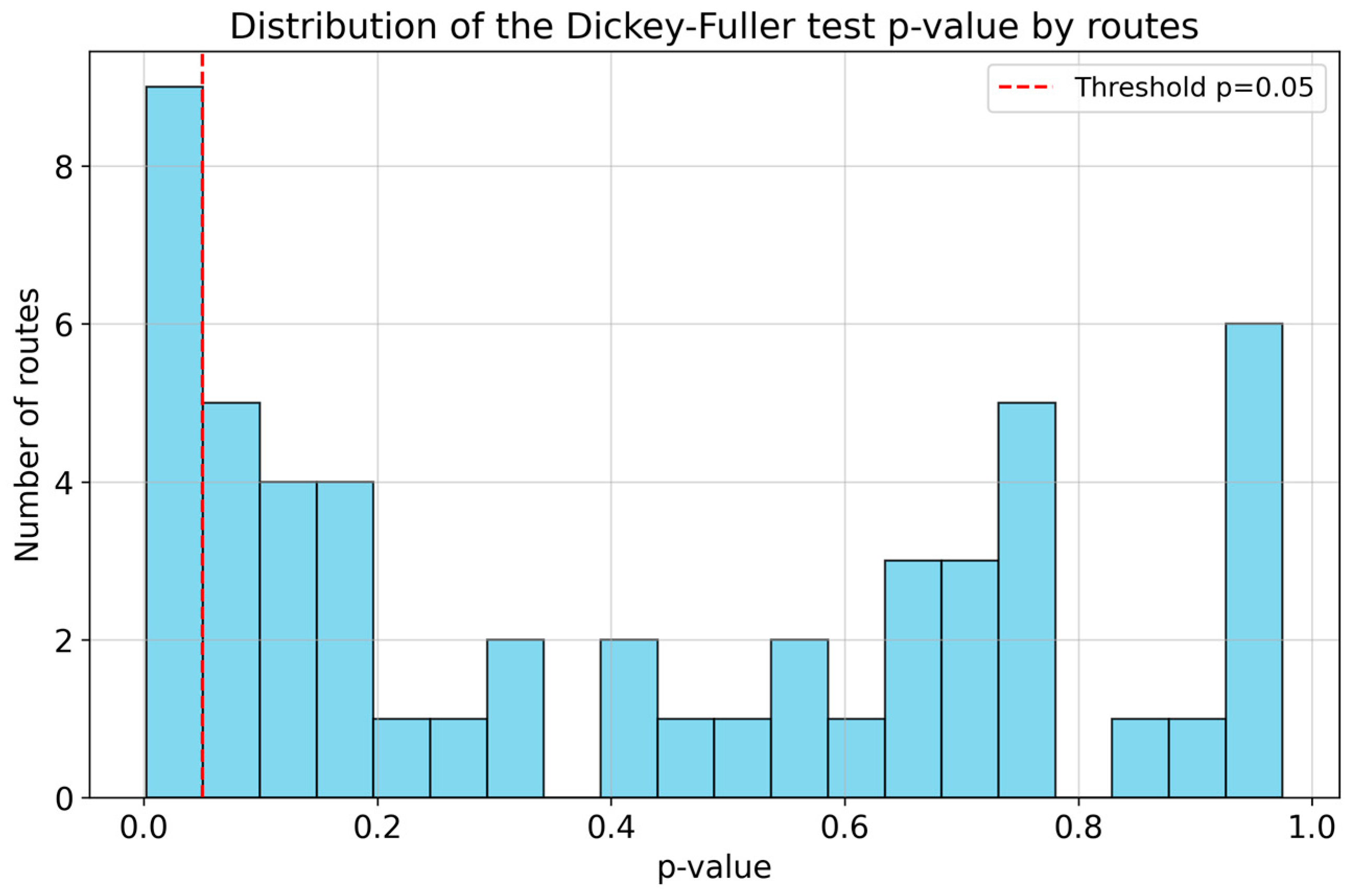

3.1. Analysis of the Spatiotemporal Unevenness in the Operation of Public Transport Routes

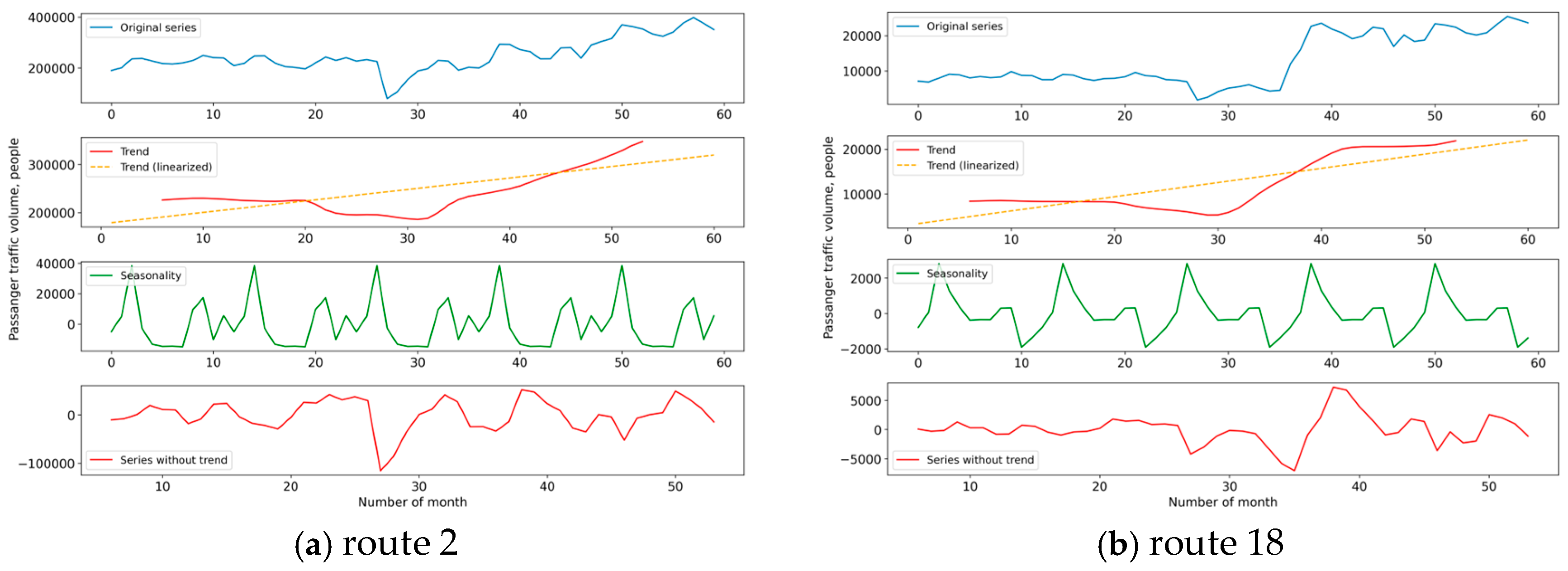

- With a decreasing trend (21 routes): 25, 30, 11, 14, 15, 17, 20, 27, 47, 48, 60, 86, 97, 98, 99, 119, 129, 135, 141, 149, 155;

- With an increasing trend (5 routes): 2, 18, 33, 100, 144;

- With no trend (constant average) (22 routes): 9, 10, 16, 32, 53, 55, 63, 85, 91, 96, 100 k, 121, 124, ‘128 s’, 134, 138, 146, 148, 152, 153, 156, 158.

3.2. Analysis of the Temporal Unevenness in the Operation of Parking Spaces

- Methods assuming normality are undesirable for constructing forecast confidence intervals.

- The series may contain outliers or varying variance.

4. Discussion

- Revising route groups in lots during municipal tenders for passenger transportation on urban routes;

- Forming holdings from carriers to create a common reserve of buses to compensate for service disruptions due to various reasons (vehicle malfunction, driver illness, other organizational issues), during the procurement of new additional buses (during system development), and renewal of rolling stock;

- Creating more flexible terms in municipal contracts for adjusting contract parameters for routes with a declining trend based on passenger traffic volume;

- Introducing this parameter into the list of calculation parameters in digital twins of cities and intelligent transport systems;

- Introducing conditions for activating route optimization procedures in the operating algorithms of digital twins of cities and intelligent transport systems when specified threshold deviations for the passenger traffic volume parameter are reached, including by changing the carrying capacity or route. For example, if traffic volumes increase and passenger flow changes on certain route sectors, additional trips on shorter routes may be introduced. If traffic volumes decrease, some trips may be transferred to shorter routes.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Burrows, A.; Bradburn, J.; Cohen, T. Journeys of the Future. Introducing Mobility as a Service; Atkins Global: Singapore, 2015; p. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Turoń, K. Sustainable Urban Mobility Transitions—From Policy Uncertainty to the CalmMobility Paradigm. Smart Cities 2025, 8, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arliansyah, J.; Prasetyo, M.R.; Kurnia, A.Y. Planning of city transportation infrastructure based on macro simulation model. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2017, 7, 1262–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, G.; Gruyter, D. Exploring links between the sustainability performance of urban public transport and land use in international cities. J. Transp. Land Use 2018, 11, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almansoub, Y.; Zhong, M.; Raza, A.; Safdar, M.; Dahou, A.; Al-qaness, M.A.A. Exploring the Effects of Transportation Supply on Mixed Land-Use at the Parcel Level. Land 2022, 11, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, L.; Kusadokoro, M.; Chitose, A.; Chen, C. Development of socially sustainable transport research: A bibliometric and visualization analysis. Travel Behav. Soc. 2023, 30, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chainikov, D.; Zakharov, D.; Kozin, E.; Pistsov, A. Studying Spatial Unevenness of Transport Demand in Cities Using Machine Learning Methods. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, G.A.; Nihan, N.L. Using Time-Series Designs to Estimate Changes in Freeway Level of Service, despite Missing Data. Transp. Res. Part A Gen. 1984, 18, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Lv, H. STEFT: Spatio-Temporal Embedding Fusion Transformer for Traffic Prediction. Electronics 2024, 13, 3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Dong, W.; Lin, H.; Lu, Y.; Wan, C.; Yin, Y.; Qin, Z.; Yang, C.; Yuan, Q. Multi-layer regional railway network and equitable economic development of megaregions. Sustain. Mobil. Transp. 2025, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabiri, S.; Heaslip, K. Inferring transportation modes from GPS trajectories using a convolutional neural network. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2018, 86, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Qi, D. Deep spatio-temporal residual networks for citywide crowd flows prediction. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2016, 31, 1655–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Xie, K.; Ozbay, K.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Z. Use of deep learning to predict daily usage of bike sharing systems. Transp. Res. Rec. 2018, 2672, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.; Sohn, K. Image-based learning to measure trac density using a deep convolutional neural network. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2017, 19, 1670–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszkowska, E.; Filipowicz-Chomko, M.; Górecka, D.; Majewska, E. Sustainable Cities and Communities in EU Member States: A Multi-Criteria Analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, A.I.; Petrova, D.A. Sustainability of Transport System of Large Russian City in the Period of COVID-19: Methods and Results of Assessment. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Akioui, A.; Monzon, A. Spatial Analysis of COVID-19 Pandemic Impacts on Mobility in Madrid Region. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Feng, Y.; Luo, W.; Ren, Y.; Tan, J.; Jiang, X.; Xue, Q. The Impacts of COVID-19 and Policies on Spatial and Temporal Distribution Characteristics of Traffic: Two Examples in Beijing. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, J.E.B.; Torres, L.E.T.; Tabare, A.; Álvarez-Martínez, D. Optimization of Bus Dispatching in Public Transportation Through a Heuristic Approach Based on Passenger Demand Forecasting. Smart Cities 2025, 8, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babapourdijojin, M.; Corazza, M.V.; Gentile, G. Systematic Analysis of Commuting Behavior in Italy Using K-Means Clustering and Spatial Analysis: Towards Inclusive and Sustainable Urban Transport Solutions. Future Transp. 2024, 4, 1430–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi, F. Visions, Paradigms, and Anomalies of Urban Transport. Future Transp. 2024, 4, 938–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, W.; Zhang, S.; Liu, F.; Pang, L. Dynamic Optimization of Exclusive Bus Lane Location Considering Reliability: A Case Study of Beijing. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, D.; Arribas-Bel, D.; Rowe, F. Tracking the Transit Divide: A Multilevel Modelling Approach of Urban Inequalities and Train Ridership Disparities in Chicago. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korzen, M.; Kruszyna, M. Public Transport Planning Using Modified Ant Colony Optimization. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreyre, F.; Chouaki, T.; Coulombel, N.; Berrada, J.; Hörl, S. Beyond Traditional Public Transport: A Cost–Benefit Analysis of First and Last-Mile AV Solutions in Periurban Environment. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J. Study on Customized Shuttle Transit Mode Responding to Spatiotemporal Inhomogeneous Demand in Super-Peak. Information 2021, 12, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zeng, W. Revealing Urban Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Emission Characteristics and Influencing Mechanisms from the Perspective of Commuting. Sustainability 2019, 11, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Kong, W.; Zhou, M.; Zhou, T.; Xu, Y.; Li, M. Prediction of Urban Taxi Travel Demand by Using Hybrid Dynamic Graph Convolutional Network Model. Sensors 2022, 22, 5982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhu, J. Characteristics, Impacts and Trends of Urban Transportation. Encyclopedia 2022, 2, 1168–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, S.; Makarov, N.; Antoniou, C. Graph Neural Networks as Strategic Transport Modelling Alternative—A Proof of Concept for a Surrogate. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 18, 2059–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Yu, H.; Wang, Y. Large-Scale Transportation Network Congestion Evolution Prediction Using Deep Learning Theory. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0119044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Route Category | Route No. | Route Length, Travel Interval | Number of Peaks | Peak Periods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increasing trend | 2 | Lr = 26.1 km, I = 15 min | 2 | fall and spring |

| 18 | Lr = 13.3 km, I = 45 min | 2 | spring | |

| Decreasing trend | 30 | Lr = 18 km, I = 5 min | 2 | spring and fall |

| 97 | Lr = 28.7 km, I = 120 min | 1 | summer (suburban route) | |

| Trend remains unchanged | 91 | Lr = 16.2 km, I = 110 min | 2 | fall and winter |

| 134 | Lr = 22.4 km, I = 180 min | 1 | summer (suburban route) |

| Route No. | Changes in Transportation Volumes, % | R2 Value for the Linear Equation Approximating the Annual Trend | Mean Squared Error (MSE) Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | +26.9 | 0.43 | 0.43 |

| 18 | +134.4 | 0.67 | 0.67 |

| 30 | −29.2 | 0.60 | 0.60 |

| 97 | −26.4 | 0.48 | 0.48 |

| 91 | - | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| 134 | - | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| No. | Route No. | Harmonic No. | Half-Amplitude of Oscillation | Initial Phase, Months | r2 | r | tr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 10,084.43 | 1.07 | 0.21 | 0.4583 | 1.63 |

| 2 | 2 | 13,836.64 | 6.42 | 0.4 | 0.6325 | 2.58 | |

| 3 | 3 | 4974.72 | 7.62 | 0.05 | 0.2236 | 0.72 | |

| 4 | 4 | 10,466.70 | 0.77 | 0.22 | 0.4690 | 1.68 | |

| 5 | 5 | 7244.02 | 1.60 | 0.1 | 0.3162 | 1.05 | |

| 6 | 30 | 1 | 12,731.83 | 9.43 | 0.02 | 0.1414 | 0.45 |

| 7 | 2 | 75,542.75 | 8.43 | 0.81 | 0.9000 | 6.52 | |

| 8 | 3 | 12,506.99 | 5.35 | 0.02 | 0.1414 | 0.45 | |

| 9 | 4 | 19,561.67 | 0.99 | 0.05 | 0.2236 | 0.72 | |

| 10 | 5 | 23,954.16 | 0.95 | 0.08 | 0.2828 | 0.93 |

| No. | Route No. | Area Under Development |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | northwestern part of the city |

| 2 | 18 | northwestern part of the city |

| 3 | 33 | northwestern part of the city |

| 4 | 100 | southwestern part of the city |

| 5 | 144 | northwestern part of the city |

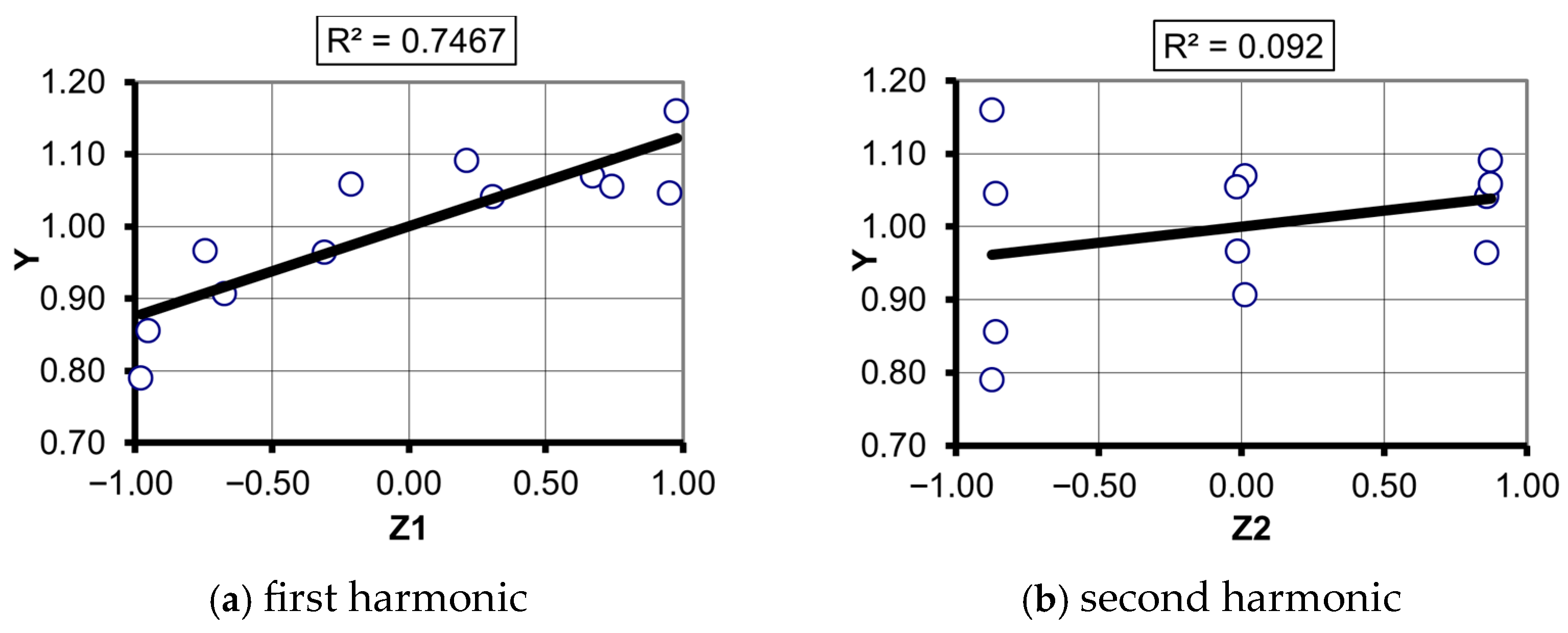

| Harmonic No. | Half-Amplitude of Oscillation | Initial Phase, Months | r2 | r | tr | t0.95 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1067.7 | 6.59 | 0.746 | 0.864 | 5.42 | 2.23 |

| 2 | 375.0 | 7.03 | 0.092 | 0.303 | 1.01 | |

| 3 | 209.3 | 8.06 | 0.028 | 0.167 | 0.54 | |

| 4 | 236.9 | 4.95 | 0.036 | 0.190 | 0.61 | |

| 5 | 355.6 | 10.92 | 0.082 | 0.286 | 0.94 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zakharov, D.; Kozin, E.; Bazanov, A.; Fadyushin, A.; Pistsov, A. Spatial and Temporal Unevenness in the Operation of Urban Public Transport and Parking Spaces. Sustainability 2026, 18, 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010225

Zakharov D, Kozin E, Bazanov A, Fadyushin A, Pistsov A. Spatial and Temporal Unevenness in the Operation of Urban Public Transport and Parking Spaces. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):225. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010225

Chicago/Turabian StyleZakharov, Dmitrii, Evgeniy Kozin, Artyom Bazanov, Alexey Fadyushin, and Anatoly Pistsov. 2026. "Spatial and Temporal Unevenness in the Operation of Urban Public Transport and Parking Spaces" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010225

APA StyleZakharov, D., Kozin, E., Bazanov, A., Fadyushin, A., & Pistsov, A. (2026). Spatial and Temporal Unevenness in the Operation of Urban Public Transport and Parking Spaces. Sustainability, 18(1), 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010225