Abstract

Understanding the carbon footprint of biomass products is of considerable practical relevance for energy conservation and emission reduction. Conducting carbon footprint assessment of bamboo scrimber products via Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) facilitates the quantitative characterization of their environmental performance and further enhances the improvement in cleaner production. This study established a model of life cycle and inventory data set for bamboo scrimber flooring from ‘cradle to gate’ that accurately quantifies carbon emissions during raw material transportation and product production stages. Two types of bamboo scrimber flooring processes were investigated: deep carbonization and shallow carbonization. Additionally, this study compared the carbon footprints of products processed using bamboo scrimber flooring and bamboo plywood production methods. Results showed that the carbon emissions during the processing of 1 m3 of deep carbon and shallow carbon bamboo scrimber flooring were 1845.99 kg CO2-eq and 1570.85 kg CO2-eq, respectively. When coupling the carbon storage of raw material supply and product usage stages, the life cycle carbon footprints for 1 m3 of deep carbon and shallow carbon bamboo scrimber flooring were 962.23 kg CO2-eq and 677.86 kg CO2-eq, respectively. The carbon emissions and life cycle carbon footprint for the processing of bamboo plywoods were 1435.55 kg CO2-eq and 640.23 kg CO2-eq, respectively. Through the analysis of different processes and their effects, adhesives were identified as the primary factor influencing the carbon footprint.

1. Introduction

Currently, China’s reliance on afforestation for increasing carbon sinks is gradually diminishing, while the use of wood products post-harvest from forests is expected to provide considerable carbon sequestration and emission reduction value. As prominent wood-based products, wood-based panel products have generally been recognized for their low-carbon attributes. Conducting carbon footprint studies on wood-based panel products based on Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) can quantitatively demonstrate their environmental friendliness and then provide quantitative methods and data support for clean production and continuous improvement in wood-based panel products throughout their life cycle.

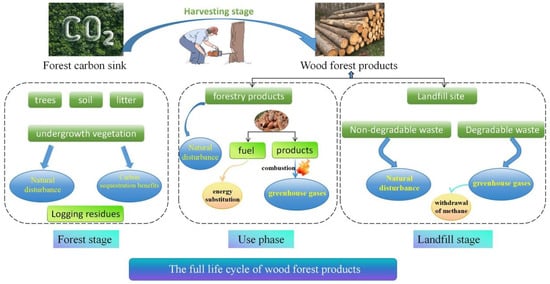

To evaluate the carbon footprint of wood-based panel products, it is essential to clarify the major life cycle stages that include carbon storage in the forest ecosystem, carbon emissions during the production stage and carbon sequestration during the product usage stage, as well as the processes of these stages in mitigating climate change [1]. These processes are shown in Figure 1. Chen et al. analyzed the integrated accounting methods for forest carbon sinks and wood product carbon storage from a forest stand scale perspective [2]. These processes describing carbon storage or emissions under three scenarios include ‘forest carbon storage without harvesting’, ‘secondary forest carbon storage + life cycle analysis results of wood products’ and ‘secondary forest carbon storage + life cycle analysis results of wood products + substitution reduction effects of wood products’. Qin et al. [3] considered time factors and bio-carbon fluxes in their dynamic life cycle analysis of the carbon footprint of forest products. It suggests that the use of wood products and substitution of fossil energy can achieve long-term climate emission reductions, compensating for carbon losses due to forest harvesting over a 100-year time scale, thus achieving carbon neutrality. Zhou et al. [4,5] studied carbon transfer rates and carbon storage models of bamboo board and filament products produced under different technical conditions (integration, reconstitution, expansion), and estimated the carbon storage of harvested bamboo boards at a regional scale using the Weibull distribution probability model of bamboo culm diameters. Most existing studies focus on a single stage of forest growth or product production, with insufficient consideration for the carbon sequestration of the product itself, and a lack of research on the interconnections between stages. A comprehensive dynamic evaluation of the carbon footprint based on the complete life cycle of trees from growth to end-of-life is needed [6,7].

Figure 1.

Flowchart of forest product Life Cycle Assessment.

Reconstituted materials are prepared from biomass resources such as planted trees. Bamboo and desert shrubs are processed into reconstituted units through fiber orientation separation technology. These units undergo precise gluing, controlled drying, systematic assembly, and uniform lamination to produce high-performance composite materials with controllable properties, designable structures, and adjustable specifications [8]. Bamboo scrimber flooring—a typical reconstituted material product—is widely used as flooring in indoor and outdoor construction, parks, and seaside locations [9].

This study aims are as follows: (1) Accurately quantify the life cycle carbon footprint of bamboo scrimber flooring, compare the carbon emissions of products manufactured using different processing technologies, and offer scientific support for clean production in enterprises. (2) This study combines carbon sequestration from raw material forest growth management, carbon emissions during the production stage and the product’s own carbon sequestration to construct an integrated model of the net emission reduction effect of bamboo scrimber flooring products over their life cycle. It also systematically establishes an LCA-based carbon footprint evaluation technical system for bamboo scrimber flooring products.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The bamboo scrimber flooring and plywood manufacturers selected for this study are located in Longquan in Zhejiang province. The density of bamboo scrimber flooring products is 1.21 g/cm3. The production processes for deep carbon and shallow carbon bamboo scrimber flooring are fundamentally similar, differing only in the temperatures set during the carbonization treatment stage. The bamboo used for plywoods is chosen from Mao bamboo aged over four years with a diameter at breast height (DBH) exceeding 9 cm.

2.2. Carbon Emissions in the Production Stage

2.2.1. Functional Units and System Boundary

The functional units for this study are defined as 1 m3 of deep carbon bamboo scrimber flooring. It includes 1 m3 of shallow carbon bamboo scrimber flooring and 1 m3 of bamboo plywood products.

System Boundary: Based on the evaluation goals and objectives, to better focus on the production processes and factory operations improvement in wood-based panels, the system boundary for the carbon footprint evaluation of wood-based panels in this study is ‘cradle to gate’, mainly including raw material acquisition (including carbon emissions from the planting and growth stages of Mao bamboo), transportation, product production, and warehousing distribution.

2.2.2. Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) Algorithm

The essence of LCI calculation for wood-based panel products is to replace intermediate products with the resource consumption and environmental emissions throughout their life cycle processes and accumulate all resource consumption and environmental emissions. As a result, the transfer of resource consumption and environmental emissions across each life cycle stage is revealed. Different intermediate products become comparable after being summed up and converted to comparable resource and environmental indicators through the summary calculation [10].

The quantification of greenhouse gas emissions and removals for each unit process in the wood-based panel product system is summarized to obtain the carbon footprint of the wood-based panel product. It is expressed in terms of carbon dioxide equivalent (kg CO2-eq). The calculation formula is as follows.

where EGHG is the product’s carbon footprint (kg CO2-eq). ADi is the activity data for the ith greenhouse gas source, EFi is the emission factor for the ith activity and GWPi is the global warming potential value for the ith activity with values referenced from the IPCC First Assessment Report ‘The Physical Science Basis’.

2.2.3. Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA) Algorithm

The LCI results for wood-based panels are characterized (multiplied by characterization factors), normalized (divided by normalization reference values) and weighted (multiplied by weighting factors) to obtain comprehensive indicators which constitute the LCA results. The LCA calculation involves summing the LCI substance indicators for the life cycle process, and then summing the characterization indicators, normalization indicators, and weighted comprehensive indicators. This method encompasses the entire process and includes multiple resource and environmental impact types [11].

The following calculation methods were used for the carbon footprint of each unit process [1].

- Raw Material Acquisition Stage

The formula for calculating carbon emissions in the raw material acquisition stage of wood-based panel products is as follows.

where GM is the carbon footprint of the raw material acquisition stage and is the physical quantity of the i-th raw material, in kg. is the physical quantity of the j-th energy source, in kg. is the emission factor for the ith material, is the emission factor for the j-th energy source and ηij is the yield rate of the i-th material and j-th energy source.

- 2.

- Transportation Stage

This stage of the carbon footprint mainly comes from the carbon emissions generated by the transportation of raw materials which is calculated as follows.

where GT is the carbon footprint of the allocation stage. is the physical quantity of the l-th transported products. Dl is the transportation distance. γl is the emission factor of the means used in transportation. Nk is the amount of the k-th greenhouse gases emitted. is the global warming potential of the k-th GHGs.

- 3.

- Product Production Stage

The formula for calculating the carbon emissions consumed in the production stage of wood-based panels is as follows.

where GP is the carbon footprint of the production stage. is the physical quantity of the j-th energy group. is the emission factor of the j-th energy source. Nk is the amount of the k-th greenhouse gases emitted. GWPk is the global warming potential of the k-th GHGs. ηjk is the energy efficiency of the production process.

2.3. LCA Index System for Artificial Board Products

With the continuous deepening of LCA research and the increasing availability of environmental baseline data for products, the evaluation content of product environmental impact types has become more accurate and comprehensive. Considering the environmental impacts during the production process of artificial board products, this study mainly considers the types of environmental impacts listed in Table 1 and the life cycle inventory factors are categorized into each impact type.

Table 1.

Environmental impact indices of artificial boards.

In addition, based on the definition of research objectives and the characteristics of artificial board products. This study focuses on the impact type of global warming that using the global warming potential (GWP) to quantify the product carbon footprint. It adopts the methods and greenhouse gas characterization factors proposed in the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report to calculate the product life cycle carbon footprint value. The method is based on the relative radiative forcing values obtained over a 100-year timeframe for other greenhouse gases compared to carbon dioxide, which are used as characterization factors to convert the emissions of other greenhouse gases into CO2-equivalents (CO2-eq).

2.4. Life Cycle Modeling Platform and Database

This study attempted to introduce eFootprint and the localized baseline database CLCD into the carbon footprint evaluation work of artificial boards. This system supports a standardized workflow compliant with ISO–LCA standards and can complete the entire LCA work online, including data entry and modeling, calculation, and data quality assessment. The Chinese Life Cycle Database (CLCD) contains thousands of production process data for hundreds of bulk energy sources, raw materials, and chemicals. These data are derived from Chinese industry statistics, relevant standards, and public reports from enterprises [12].

2.4.1. Material Transfer Analysis in the Production Stage of Artificial Board Products

The comprehensive material transfer rate of bamboo scrimber flooring is the product of the material transfer rates at each production stage. The comprehensive material transfer model is as follows.

where λcomprehensive is the comprehensive material transfer rate of bamboo scrimber flooring. mcutting, after is the material weight after cutting. mplaning, after is the material weight after planing. msanding, after is the material weight after sanding. mcutting, before is the material weight before cutting. mslicing, before is the material weight before slicing. mjointing, before is the material weight before jointing.

λcomprehensive = λcutting × λslicing × λplaning × λjointing × λsanding = (mcutting, after/mcutting, before) × (mslicing, after/mslicing, before) × (mplaning, after mplaning, before) × (mjointing, after/mjointing, before) × (msanding, after/msanding, before) = (mcutting, after × mplaning, after × msanding, after)/(mcutting, before × mslicing, before × mjointing, before)

Considering factors such as product density, moisture content, comprehensive material transfer rate, and bamboo moisture content, the weight of bamboo required to produce a specified volume of bamboo scrimber flooring is calculated using the following model.

where Mbamboo is the weight of bamboo required for producing bamboo scrimber flooring. Vreconstituted is the volume of bamboo scrimber flooring with 1 m3 used as the functional unit in this study. ρreconstituted is the density of bamboo scrimber flooring. ωreconstituted is the moisture content of bamboo scrimber flooring. λcomprehensive is the comprehensive material transfer rate of bamboo scrimber flooring. ωbamboo is the moisture content of bamboo. The calculated weight of bamboo required to produce 1 m3 of bamboo scrimber flooring is 2335.52 kg for deep carbon and 2438.1 kg for shallow carbon.

Mbamboo = Vreconstituted × ρreconstituted × (1 − ωreconstituted)/[λcomprehensive(1 − ωbamboo)]

The comprehensive material transfer rate of bamboo plywoods is the product of the material transfer rates at each production stage. The comprehensive material transfer model is as follows.

λbamboo template = λcutting × λremoving outer nodes × λremoving inner nodes × λyellow planing × λgreen planing × λtrimming = (mcutting, after/mcutting, before) × (mremoving outer nodes, after/mremoving outer nodes, before) × (mremoving inner nodes, after/mremoving inner nodes, before) × (myellow planing, after/myellow planing, before) × (mgreen planing, after/mgreen planing, before) × (mtrimming, after/mtrimming, before) = (mgreen planing, after × mtrimming, after)/(mcutting, before × mtrimming, before)

In the above formula, λbamboo template is the comprehensive material transfer rate of bamboo plywoods. mgreen planing, after is the material weight after green planing. mtrimming, after is the material weight after trimming. mcutting, before is the material weight before cutting. mtrimming, before is the material weight before trimming.

Considering the product density, moisture content, comprehensive material transfer rate and bamboo moisture content, the weight of bamboo required to produce a specified volume of bamboo plywood is calculated using the following model.

where mbamboo is the weight of bamboo required for producing bamboo plywoods. Vbamboo template is the volume of bamboo plywood, with 1 m3 used as the functional unit in this study. ρbamboo template is the density of bamboo plywood. ωbamboo template is the moisture content of bamboo plywood. λbamboo template is the comprehensive material transfer rate of bamboo plywoods. ωbamboo is the moisture content of bamboo. The calculated weight of bamboo required to produce 1 m3 of bamboo plywood is 3142.46 kg.

mbamboo = Vbamboo template × ρbamboo template × (1 − ωbamboo template)/(λbamboo template × (1 − ωbamboo))

2.4.2. Carbon Storage Measurement in Raw Material Supply

Forest (bamboo forest) harvesting is divided into three parts: trunk, branches, and leaves [13]. The trunk part (bamboo culm) is transported to the factory for product production, and its carbon storage is considered part of the product carbon storage. To avoid redundant calculations, this carbon sink from forest management is not considered [14]. Carbon fixed by branches and leaves through photosynthesis is considered to be fully released into the ecosystem after harvesting, maintaining carbon balance [15]. The remaining root system after harvesting is generally retained and can continue to act as a carbon sink [16]. This study focuses on the carbon storage in underground biomass after harvesting.

Fixed plots are set up in a bamboo forest at the raw material production site in Longquan in Zhejiang province. The plot area is 400 m2 (20 m × 20 m) with three plots surveyed. Each bamboo in the plot is measured and biomass is determined [17,18,19].

Plot Survey: Each 20 m × 20 m bamboo forest plot has similar elevation, terrain characteristics, nutrient conditions, disturbance history, succession status, and community structure. During the vegetation survey, all woody plants with a diameter at breast height (DBH) ≥ 1 cm are marked with red paint at the DBH position (1.3 m above the ground) and numbered. Subsequent work includes species identification, recording tree species names, measuring DBH and tree height, recording sprouting and other indicators, and noting the relative coordinates of each tree in the plot.

Biomass Measurement: One standard bamboo per plot is selected. Bamboo has a complex underground rhizome system. Each standard bamboo is divided into five parts: bamboo culm, branches, leaves, rhizome, and rhizome roots. Bamboo rhizomes and roots are collected using a small sampling method [20]. The above-ground parts are divided into branches, leaves, and culm (stalk). Fresh weights are measured and samples of different organs are taken back to the laboratory for drying. The fresh weight, dry weight, and actual moisture content of each sample are determined.

Carbon Storage Calculation: The carbon content of bamboo comes from the ‘Assessment of Biomass and Carbon Storage in Chinese Forest Vegetation’ [17] with a reference value of 0.5042 kg CO2-eq/kg.

2.4.3. Carbon Storage Calculation for Artificial Board Products

Equipment: Cutter, grinder, oven, electronic scale, vernier caliper, micrometer and Germany Jena multi N/C® 3100 Total Organic Carbon/Total Nitrogen Analyzer (Analytik Jena, Jena, Germany).

Sample Preparation: Samples are pretreated [21].

- Artificial board samples are cut into 50 × 50 mm pieces, four pieces per sample, for density and moisture content measurement.

- A cutting machine processes the samples into pieces approximately 3 cm in length and no more than 3 mm in thickness, which are then ground.

Due to the small amount of samples used in the experiment. The study ensures comprehensive and uniform sampling by ‘three-stage grinding method’. The first stage involves grinding about 600 g of the sample and mixing it thoroughly. Then take out 200 g for the second stage, mix it again, and take 100 g for the third stage. After the final grinding, the samples are dried at 85 °C until a constant weight is achieved. Then they are bottled for subsequent carbon content and thermogravimetric measurements.

Carbon Content Measurement: The organic carbon content of artificial board samples is measured using the dry combustion method. Specifically, 15–20 mg of dried sample powder is weighed and then fully decomposed and combusted at 1000 °C under a pure oxygen flow. The carbon elements in the sample are converted into CO2 and quantified using the oxidation–non-dispersive infrared absorption method.

Carbon Storage Calculation: First, measure the density of the samples by measuring the dimensions of the 50 × 50 mm pieces. Take two measurements from different positions for accuracy and calculate the average density. Samples are then dried at 85 °C until completely dry then cooled to room temperature and weighed again to calculate the average moisture content [22]. The formula for carbon storage calculation is as follows:

where Cs is the carbon storage of the sample, in kg/m3. Cf is the carbon content of the sample, in %. MC is the moisture content of the sample, in %. m is the mass of the sample, in g. V is the volume (or surface area) of the sample, in m3 (or m2).

Cs = Cf × (1 − MC) × m/V

2.5. Integrated Assessment

The mathematical expression for the integrated assessment can be simplified as follows:

where TC represents the carbon footprint of the artificial board product life cycle. FC represents the carbon storage in the raw material supply stage. PTC represents the carbon footprint of the raw material extraction and production stages of the artificial board product. PDC represents the carbon sequestration capability of the artificial board product.

TC = FC + PTC + PDC

The bio-carbon storage during the use phase of the artificial board product is calculated according to the method described in ‘PAS2050:2008’ [23]. If the total carbon storage benefit of a product exists for 2–25 years after product formation (after which the carbon storage benefit ceases), the weight factor for CO2 storage benefit during the 100-year assessment period (F0) is calculated as follows:

where n is the number of years the product maintains full carbon storage benefit after formation.

The CO2 storage amount (S, kg CO2) for a product used for n years is calculated as follows.

where C is the bio-carbon content of the product (kg C). The conversion factor from carbon to CO2 is .

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Material Transfer Analysis

The production of bamboo scrimber flooring employs the ‘bamboo-based fiber composite material manufacturing technology’, which enables factories to directly process bamboo as raw material without the need for splitting, removing the green layer, or yellowing processes. This technology is suitable for processing both large-diameter Mao bamboo and small-diameter miscellaneous bamboo, with a bamboo utilization rate of over 90% [24].

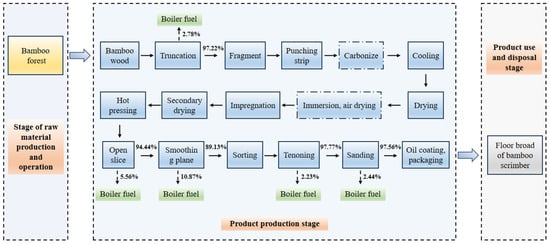

The life cycle and material transfer rates of various processes for bamboo scrimber flooring are shown in Figure 2. By tracking and measuring the material transfer rates of each production stage of deep carbon bamboo scrimber flooring and multiplying the material transfer rates of each process, the overall material transfer rate from raw bamboo to the finished product is 78.06%.

Figure 2.

Bamboo scrimber flooring life cycle.

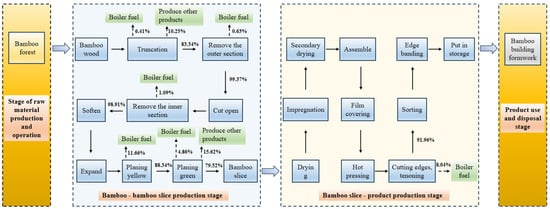

The production process from raw bamboo to bamboo plywood is designed as follows: Raw bamboo undergoes steps such as cutting, removing outer nodes, splitting, softening, flattening, and removing the green and yellow layers to form bamboo strips. These strips are then dried, glued, assembled, hot-pressed, and trimmed to form artificial boards based on the principles of plywood construction.

The complete life cycle of the bamboo plywood studied in this paper is shown in Figure 3. By tracking and measuring the material transfer rates at each production stage and multiplying the material transfer rates of each process, an overall material transfer rate from raw bamboo to the finished product of 52.92% is obtained.

Figure 3.

Bamboo plywood form work life cycle.

3.2. Carbon Emissions in the Production Process of Bamboo Scrimber Flooring

3.2.1. Comparison of Different Heat Treatment Processes for Bamboo Scrimber

The carbon emissions during the production phase of 1 m3 of deep carbon bamboo scrimber flooring are 1845.99 kg CO2-eq. The highest sensitivity in the production inventory of deep carbonized bamboo scrimber flooring is adhesives, with a contribution rate of 88.18%. The sensitivity of electricity in the reconstituted board production process is 13.90%, while the sensitivity of carbon emissions from raw bamboo production and management is 13.69%. Moreover, the sensitivities for the transportation of raw bamboo are 2.95% and 2.50%. Other raw materials have smaller sensitivities. It is evident that adhesives, electricity and raw bamboo are the major sources of carbon emissions throughout the life cycle of deep carbon bamboo scrimber flooring. Adhesives are the main raw material input that have a carbon footprint of 1627.80 kg CO2-eq (accounting for 88.18% of the carbon emissions in the product production phase).

The carbon emissions during the production phase of 1 m3 of shallow carbon bamboo scrimber flooring are 1570.85 kg CO2-eq. The highest sensitivity in the inventory of shallow carbon bamboo scrimber flooring production is for adhesives, with a contribution rate of 84.16%. The sensitivity of electricity in the reconstituted board production process is 16.52%. The sensitivity of raw bamboo is 15.32%, and the sensitivity of raw bamboo transportation is 2.54%. Other raw materials have smaller sensitivities.

It is evident that adhesives, electricity, and raw bamboo are the major sources of carbon emissions throughout the life cycle of shallow carbon bamboo scrimber flooring.

3.2.2. The Impact of Adhesives

Adhesives, as the main raw material input for shallow carbonized bamboo scrimber flooring, contributed 1321.98 kg CO2-eq (84.16% of production stage carbon emissions. Previous studies on the carbon footprint of bamboo scrimber flooring indicated that the carbon emission from the processing of 1 m3 of bamboo scrimber flooring is 143.5591 kg CO2-eq, which is significantly lower than the data obtained in this study. The analysis reveals two main reasons: Firstly, previous studies [21] did not consider the carbon emissions from the cultivation, management, and operation activities of raw bamboo, as well as external energy consumption such as power, water, and fertilizers. Secondly, previous studies only considered the carbon emissions during the use phase of adhesives without taking into account the upstream production process of adhesives. Resin impregnation is the core step in the high-quality preparation of reconstituted materials. The currently widely used discontinuous batch impregnation can only ensure the uniformity of adhesive impregnation by reducing the moisture content of reconstituted units and extending the impregnation time. This leads to increased adhesive usage and energy consumption during the preparation process. Optimizing the impregnation process by considering factors such as the moisture content of bamboo bundles, cross-sectional size, solid content of adhesives, and impregnation time, or adopting continuous roller impregnation technology, can enhance production efficiency and reduce energy consumption [25].

3.2.3. Comparison of Reconstituted and Laminated Production Methods

A life cycle model of the product was established on eFootprint to calculate the LCA results for 1 m3 of bamboo plywood. The carbon emission during the production process of 1 m3 of bamboo plywood is 1435.55 kg CO2-eq. In the inventory of bamboo plywood production, the factor with the highest sensitivity is adhesives, with a contribution rate of 78.32%. The sensitivity of electricity consumption is 17.98%, and other raw materials have smaller sensitivities. Evidently, adhesives and electricity consumption are major sources of carbon emissions throughout the life cycle of bamboo plywoods. LCA studies on plywood are relatively scarce with existing research primarily focused on the United States and few reports from other countries. Yang, et al. [21] surveyed eight representative plywood companies in the southeastern United States and found that the environmental load during the production process was significantly higher than during the operational phase. The carbon footprint of producing 1 m3 of plywood was 698 kg CO2-eq in the southeastern United States and 674 kg CO2-eq in the Pacific Northwest region.

Through inventory sensitivity analysis, it was found that adhesives have a high inventory sensitivity with carbon footprint contributions of 88.18%, 84.16% and 78.32% for deep carbon bamboo scrimber flooring, shallow carbon bamboo scrimber flooring, and bamboo plywoods, respectively. Combined with inventory analysis, it was found that the weights of adhesive consumed in producing 1 m3 of deep carbon bamboo scrimber flooring, shallow carbon bamboo scrimber flooring, and bamboo plywood were 470 kg, 420 kg, and 140 kg, respectively. The differences in carbon footprints among products are primarily attributed to the higher adhesive consumption in the production of high-emission artificial board products. This suggests that utilizing lower-carbon upstream materials or alternative clean energy can reduce carbon emissions during the production process.

3.3. Integrated Evaluation of Carbon Emission Reduction Post-Bamboo Harvest

3.3.1. Extending the System Boundary to the Raw Material End

The formula for calculating the carbon storage in the raw material supply stage in this study is as follows.

where Csupply is the carbon storage in the raw material supply stage. mraw material is the weight of raw materials required to produce 1 m3 of artificial board product. According to the material transfer model of the product. The weights of raw bamboo required to produce 1 m3 of deep carbon bamboo scrimber flooring, shallow carbon bamboo scrimber flooring and bamboo plywood are 2335.52 kg, 2438.1 kg and 3142.46 kg, respectively. ηpost-harvest is the proportion of the underground biomass to the raw bamboo biomass post-harvest, which is 25.89%. λ is the carbon content rate of the tree species which is 0.5042 kg CO2-eq/kg. ηraw material is the proportion of raw material biomass to the raw bamboo biomass with a value of 55.03%.

Csupply = (mraw material × ηpost-harvest × λ)/ηraw material,

From the formula. It is calculated that the carbon storage in the raw material supply stage for producing 1 m3 of deep carbon bamboo scrimber flooring, shallow carbon bamboo scrimber flooring and bamboo plywood are 554.01 kg CO2-eq, 578.34 kg CO2-eq and 745.43 kg CO2-eq, respectively. It can be seen that compared with bamboo plywoods, the raw material supply stage of bamboo scrimber flooring has a lower carbon storage mainly because producing 1 m3 of artificial board product requires more raw bamboo for plywoods, which leads to more CO2 fixed in the corresponding underground biomass.

3.3.2. Extending the System Boundary to the Product Use End

The carbon storage per cubic meter of deep carbon bamboo scrimber flooring is the highest, reaching 591.65 kg/m3.The carbon storage of deep carbon bamboo scrimber flooring, shallow carbon bamboo scrimber flooring, bamboo plywood, and wood-based panel products is 591.65 kg/m3, 564.57 kg/m3, 358.08 kg/m3, and 253.55 kg/m3, respectively. It can be seen that the carbon storage per cubic meter of bamboo scrimber flooring is higher than that of plywood. The main reasons are that the density of bamboo scrimber flooring is higher than that of plywood, with deep carbon bamboo scrimber flooring having a density of 1.21 g/cm3, which is greater than that of bamboo plywood (density of 1.08 g/cm3). Additionally, the adhesive usage in the production of bamboo scrimber flooring is greater than that of bamboo plywoods, being 470 kg and 140 kg, respectively. The carbon content rate of water-soluble phenolic resin is about 68.85% [22] which also contributes to the higher carbon storage in bamboo scrimber flooring. For plywood, the carbon storage in bamboo plywood is higher than that in wood plywood. Bamboo plywood is generally composed of grooved equal-thickness bamboo strips, glued on both sides with water-soluble phenolic resin using a four-roller coating machine with an adhesive amount of 300–350 g/m2. Wood plywood used indoors typically employs urea–formaldehyde resin, which has a carbon content rate of only 26.67%, much lower than that of phenolic resin. This may lead to the higher carbon content rate in bamboo plywood compared to wood plywood.

3.4. Integrated Evaluation

From the results of the carbon storage measurements of the products, the carbon storages of deep carbon bamboo scrimber flooring, shallow carbon bamboo scrimber flooring, and bamboo plywood are 591.65 kg/m3, 564.57 kg/m3, and 358.08 kg/m3, respectively. In this study, the designed service lives of deep carbon bamboo scrimber flooring, shallow carbon bamboo scrimber flooring, and bamboo plywoods are 20 years, 20 years, and 5 years, respectively. The carbon storage effect during the product use stage for deep carbon bamboo scrimber flooring, shallow carbon bamboo scrimber flooring, and bamboo plywoods offsets emissions of 329.75 kg CO2-eq, 314.65 kg CO2-eq and 49.89 kg CO2-eq, respectively.

By coupling the carbon storage at the raw material supply stage with the ‘cradle—to—gate’, carbon footprint and the carbon storage and delayed emissions of the products (Table 2). The life cycle carbon footprint of the three types of artificial board products was calculated using Formula (6).

Table 2.

Carbon footprint of various links in wood-based panel products.

The calculation results show that the life cycle carbon footprints from raw material management to the product use stages for 1 m3 of deep carbon bamboo scrimber flooring, shallow carbon bamboo scrimber flooring, and bamboo plywoods are 962.23 kg CO2-eq, 677.86 kg CO2-eq, and 640.23 kg CO2-eq, respectively. Combining the analysis of carbon footprints at different product stages, it was discovered that products with high carbon emissions during the production stage also possess larger carbon storage during the use stage. For example, compared to bamboo plywood, bamboo scrimber flooring has relatively higher emissions during the production stage. However, with a designed service life of 20 years, the delayed emission effect of the product is significant. This indicates that when comparing product carbon footprints, a comprehensive analysis should consider the use scenario and added value of the product.

3.5. Analysis of Substitution Emission Reduction Effect

In this study, bamboo plywood was used as the main model, and steel templates were used as the substitute model. The production of steel templates with equivalent functionality to 1 m3 of bamboo plywood was compared. To quantify the inputs/outputs in the system, the functional unit was defined as producing 1 m3 of bamboo plywoods and steel templates with equivalent functionality to 1 m3 of bamboo plywoods. The carbon footprint of steel templates with equivalent functionality to 1 m3 of bamboo plywoods is 13,154.86 kg CO2-eq.

Comparative studies have found that bamboo plywoods have a significantly lower environmental impact than steel templates with equivalent functionality. This is especially evident in terms of carbon footprint, primary energy consumption, and water resource consumption. The environmental impact of steel templates is approximately ten times higher than that of bamboo plywood. Studies have shown that the substitution emission reduction effect is, on average, more than the carbon content of the product itself. When used in construction, it can even be as high as 2 to 10 times more than the carbon content of the product itself [24,26]. This is consistent with the results of this study, where the substitution emission reduction effect can be coupled with the increased carbon storage of forest products [9,27]. However, it should also be noted that most studies are often limited to energy substitution or partial product-type substitution. There is relatively little research that incorporates various energy and product substitutions throughout the full life cycle while concurrently considering post-harvest carbon storage in forest management.

3.6. Limitations of the Study

Studies have shown that at the end of the life cycle, 60% of waste artificial boards can be treated by incineration and 40% by landfill [28]. This was used as the baseline scenario (S0). The scenario simulation results of different waste treatment methods show that, compared to the S0 scenario, the scheme of treating all products by incineration (S1) contributes relatively little to carbon storage while the scenario of treating all products by landfill (S3) can offset most of the greenhouse gas emissions over the life cycle [25]. Due to the complexity of processes involving recycling, landfill, and incineration, future studies will focus on the carbon footprint of the product disposal stage. Plantation is the main source of wood products, and its biomass carbon storage changes frequently. Stable and long-lasting soil carbon pool is of great importance for the carbon sequestration potential of plantations [29]. Forest soil is also recognized as the most promising carbon sink [30]. Afforestation, harvesting, and other forest management practices have a direct impact on the soil carbon cycle [31]. However, there is insufficient understanding of the dominant control factors and control processes of soil organic carbon and inaccurate assessment of the atmospheric carbon balance. Related studies still have many uncertainties [32]. In this study, the proportions of underground biomass carbon storage offsetting the carbon emissions in the production stage for deep carbon bamboo scrimber flooring, shallow carbon bamboo scrimber flooring, and bamboo plywoods (calculated as the ratio of carbon storage in the supply stage to the carbon footprint in the production stage) reached 30.01%, 36.82%, and 51.93%, respectively.

Future research will further consider the factors of post-harvest soil carbon storage to further highlight the carbon sequestration advantages of woody materials.

4. Conclusions

A carbon footprint evaluation framework based on LCA was constructed that included four aspects: goal and scope definition, inventory analysis, life cycle modeling, and result interpretation. The functional units of this study were determined to be 1 m3 of deep carbon bamboo scrimber flooring, 1 m3 of shallow carbon bamboo scrimber flooring, and 1 m3 of bamboo plywoods. The system boundary was ‘cradle-to-gate’, including stages such as raw material acquisition and transportation, product production, warehousing and distribution. Considering the characteristics of artificial board products, the system boundary was extended to include both upstream and downstream stages, comprehensively considering the carbon storage of raw material supply and the products themselves. The main conclusions are as follows.

- (1)

- The production-stage carbon footprint of bamboo scrimber flooring products was accurately quantified. The LCA impact assessment and result interpretation for the two types of artificial board products revealed that the carbon emissions during the production process of 1 m3 of deep carbon bamboo scrimber flooring and shallow carbon bamboo scrimber flooring were 1845.99 kg CO2-eq and 1570.85 kg CO2-eq, 1435.55 kg CO2-eq, respectively. Further sensitivity analysis revealed that adhesives had the greatest sensitivity in the product production stage inventory.

- (2)

- Combine the carbon emissions during the production phase of wood-based panel products with the carbon storage during the raw material supply phase and the carbon storage during the product use phase, thereby achieving a comprehensive assessment of the carbon footprint across the entire life cycle. The life cycle carbon footprints of 1 m3 of deep carbon bamboo scrimber flooring and shallow carbon bamboo scrimber flooring were 962.23 kg CO2-eq, 677.86 kg CO2-eq and 640.23 kg CO2-eq, respectively.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Z. and G.Z.; Data curation, G.Z.; Investigation, N.S.; Methodology, A.Z. and X.T.; Software, A.Z.; Writing—original draft, A.Z. and W.T.; Writing—review and editing, X.T. and W.T.; Validation, A.Z., G.Z. and X.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work of this paper is jointly funded by research project of China National Academy of Bamboo Industry (2025YJY08) and 2025 annual key scientific and technological project of the East China Survey and Planning Institute of the National Forestry and Grassland Administration ‘Key Technologies for Preparing Engineering Building Materials in Nature Reserves and Environmental Impact Assessment’ (HDY25N020). The funder is Anming Zhu.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

LCA: Life Cycle Assessment; DBH: diameter at breast height; LCI: Life Cycle Inventory; LCIA: Life Cycle Impact Assessment; PCF: product carbon footprint; GWP: global warming potential; CO2-eq: CO2-equivalents; CLCD: Chinese Life Cycle Database.

References

- Green, C.; Avitabile, V.; Farrell, E.P.; Byrne, K.A. Reporting harvested wood products in national greenhouse gas inventories: Implications for Ireland. Biomass Bioenergy 2006, 30, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ter, M. Assessing the greenhouse gas effects of harvested wood products manufactured from managed forests in Canada. Forestry 2018, 91, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z. Development Status and Trend of Plywood Industry in China. China For. Prod. Ind. 2020, 57, 1–3+9. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, F.; Shi, Y. Present Situation and Prospect of Building Formwork Products in China. Constr. Technol. 2017, 46, 98–101. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, G.; Jiang, P. Density, storage and spatial distribution of in Phyllostachys pubescens forest. Sci. Sylvae Sin. 2004, 40, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, B.; Ma, X. Connotation of bamboo carbon footprint and its regulating effect on bamboo industrial development. World Bamboo Ratt. 2020, 18, 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Yang, H. Study on carbon emission reduction path of China’s wood-based panel industry based on international carbon footprint standards. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2019, 29, 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, B. Scrimber: The leading edge of timber technology. In Proceedings of the 2nd Pacific Timber Engineering Conference, Auckland, New Zealand, 28–31 August 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Qin, L.; Yu, W. Manufacturing Technology of Bamboo-Based Fiber Composites Used as Outdoor Flooring. Sci. Sylvae Sin. 2014, 50, 133–139. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, J.; Zhang, F.; Xu, C. Evaluation of life cycle inventory at macro level: A case study of mechanical coke production in China. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess 2015, 20, 751–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Shaked, S.; Rosenbaum, R. Analytical uncertainty propagation in life cycle inventory and impact assessment: Application to an automobile front panel. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess 2010, 15, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.L.; Wang, H. Method and basic model for development of Chinese reference life cycle database. Acta Sci. Circumst. 2010, 30, 2136–2144. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H. Studies on Standing Tree Biomass Models and the Corresponding Parameter Estimation. Ph.D. Thesis, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.Q.; Yu, Z.H. Research trends and future key issues of global harvested wood products carbon science. J. Nanjing For. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 45, 219–228. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S. Study on the Anti-Mildew Performance of Rhizoma Corydalis Compound Nano-TiO2 on Bamboo; Inner Mongolia Agricultural University: Huhehaote, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.G.; Van, E. Accounting Carbon Storage in Decaying Root Systems of Harvested Forests. AMBIO 2012, 41, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.G.; Liu, J. Biomass and Distribution Patterns of Pinus massoniana Plantation in Northwest Guangxi. Guangxi For. Sci. 2010, 39, 189–192+219. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.X.; He, D.B. Moisture content and model of Pinus Massoniana in Southern China. Cent. S. For. Inventory Plan. 2011, 30, 56–60+64. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Jiang, Z.H. Biomass allocation of aboveground components of Phyllostachys edulis and its variation with body size. Chin. J. Ecol. 2014, 33, 2019–2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, C. Study on the Rule of Nitrogen Utilization and Its Influence Factors in Phyllostachys Edulis Forests; Chinese Academy of Forestry: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.J.; Fu, W.S.; Yu, W.J. Research status of the parameters of internal-mat conditions during hot-pressing. For. Grassl. Mach. 2008, 4, 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W. Research on the Determination of Wood Carbon Content Rate and Carbon Storage Database; Northeast Forestry University: Harbin, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- PAS2050:2008; Evaluation Specifications for Greenhouse Gas Emissions during the Life Cycle of Goods and Services. British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2008.

- Zhang, Y. Study on the Effect of Color and Physical-Mechanical Properties for Heat-Treated Bamboo; Chinese Academy of Forestry: Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lun, F.; Liu, M.; Zhang, D. Life Cycle Analysis of Carbon Flow and Carbon Footprint of Harvested Wood Products of Larix principis-rupprechtii in China. Sustainability 2016, 8, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathre, R.; O’Connor, J. Meta-analysis of greenhouse gas displacement factors of wood product substitution. Environ. Sci. Policy 2010, 13, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churkina, G.; Organschi, A.; Reyer, C.P.O. Buildings as a global carbon sink. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunet, N.P.; Jochheim, H.; Brunet, N. Effect of cascade use on the carbon balance of the German and European wood sectors. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Y.; Zhou, L.Y. Application of blockchain technology in carbon footprint tracing and accounting of textile and apparel products. J. Silk 2023, 60, 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, M.F.; Zhang, X.S. Effect of management practices on forest platation soil carbon. Chin. J. Ecol. 2010, 29, 2265–2271. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, J.C.; Tate, K.R.; Mcmurtrie, R.E. Mechanisms for changes in soil carbon storage with pasture to Pinus radiata land-use change. Glob. Change Biol. 2010, 9, 1294–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.W.; Huang, Z.L. Advances on effect of forest management on soil carbon sequestration. J. Henan Agric. Sci. 2012, 41, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.