Abstract

The aim of the study is to analyze the challenges and opportunities of conversions and adaptations of Polish modernist hotel buildings to new functions. Preliminary research shows that hotels constitute a significant group among unused buildings from that period. This issue remains unexplored, while the market situation shows that investors will increasingly face an economic, social, and environmental dilemma as to demolish existing facilities and replace them with new structures or thoroughly rebuild and reuse. The study was conducted based on an analysis of groups of criteria in terms of the potential and difficulties associated with investments utilizing the existing hotel fabric, taking into account environmental, formal, structural, functional, and socio-cultural aspects. The results of the study show that the conversion or adaptation of modernist hotels in Poland to a new function is primarily determined by technical issues, i.e., the original structural layout and technical condition of the building, and such investments require decisive action, primarily in terms of replacing external partitions and adapting internal communication systems. However, it has been proven that, in many cases, such investments are possible, and they bring a number of environmental and social benefits, so they are at least desirable from the perspective of sustainable development.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Overview

Over the last three decades, the Polish economy has grown steadily, beginning in the early 1990s after the first non-Communist government implemented economic reforms. By 2024, GDP reached US $914,696.43 million, ranking Poland 21st globally [1,2]. Although classified by the International Monetary Fund as an ‘Emerging and Developing Economy’, Poland aims to join the ‘Advanced Economies’ group in the near future [3].

Economic growth coincides with urban densification, while many mid-20th century buildings approach functional obsolescence due to material deterioration, evolving norms, and socio-economic changes. Thomsen and Van der Flier distinguish physical and functional obsolescence, showing that sound buildings may become unsuitable before failing physically [4]. This raises challenges for architects and planners seeking sustainable and economically viable redevelopment [5].

With limited undeveloped land, brownfield redevelopment is increasingly pursued [6,7], but such sites suit only specific functions, pushing developers toward existing urban buildings with declining uses [8]. Redevelopment options include demolition for new construction—sometimes restricted by conservation rules—or adaptive reuse, which reduces environmental impact but involves technical challenges [9,10,11,12].

In Poland, hotels form a notable group among buildings for redevelopment. Changing codes and service standards have made many older hotels functionally inadequate, leading to closures and new developments elsewhere. This particularly affects mid-to-late 20th century modernist hotels, such as CRACOVIA and FORUM Hotels in Cracow (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

The CRACOVIA Hotel—a building that served as an exclusive hotel between 1965 and 2011, designed in the spirit of Krakow modernism by Professor Witold Cenckiewicz. Currently listed as a historic monument, it cannot be reopened in its primary form and function for technical reasons and has remained unoccupied for over a decade (photo: Wojciech Duliński).

Figure 2.

The FORUM Hotel—a prominently located (vis-à-vis the famous Wawel Castle) estate that ceased hotel operations in 2002. Architecture preserved in the spirit of pronounced brutalism of the modernist era has, over the years, become the subject of dispute among architects, urban planners, and conservators, which ultimately contributed to the present investment impasse (photo: Wojciech Duliński).

Aging, underutilized buildings are a growing concern, with obsolete hotels facing demolition or redevelopment. Research is needed to assess how existing hotel stock can reduce carbon footprint, support sustainable urban development, and address technical, regulatory, and economic challenges. While adaptive reuse of other building types in Poland has been studied, systematic exploration of hotel redevelopment remains limited. This study examines hotels as a distinct typology within urban densification and sustainable refurbishment discussions.

1.2. Adaptive Reuse Feasibility

Adaptive reuse is a well-established approach in contemporary architecture, demonstrating that existing buildings can be successfully transformed for new functions [13,14]. Although formally recognized only in the late 20th century, the practice has a long tradition of extending building life rather than replacing structures [15]. It supports sustainability by retaining embodied carbon, conserving resources, preserving cultural identity, and offering flexibility for modern needs [5,16]. Studies show that refurbishment can outperform demolition in environmental impact, whole-life carbon, and community value, especially when addressed early in design [17,18].

Renowned architectural transformations show reuse is feasible in demanding contexts. The Louvre in Paris illustrates how a royal palace was successfully reimagined into one of the world’s leading museums, a cultural function very different from its original purpose. Similarly, Tate Modern in London demonstrates how a decommissioned power station could be adapted into an international contemporary art gallery, preserving the monumental industrial character while accommodating new cultural programs [15,19]. The Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg, which integrates a new concert hall into the structure of a 1960s warehouse, is another example that illustrates how adaptive reuse can merge historic structures with bold contemporary additions [20]. These projects show that specialized functions can fit within existing buildings when carefully adapted.

In Poland, several projects demonstrate the viability of adaptive reuse [21]. The former Żnin Sugar Factory was transformed into a hospitality and leisure complex, preserving its heritage while accommodating hotels, restaurants, and cultural amenities [22]. Warsaw’s Hala Koszyki now combines a historic market hall with a modern food hall and public space, and Fabryka Norblina integrates offices, cultural institutions, and retail within a restored factory. These examples show that adaptive reuse in Poland is technically feasible and socially and economically beneficial.

Hotels represent a building type that has also been adapted to new uses across the world. Many conversions have turned former hotels into residential buildings, taking advantage of their repetitive floor plans and service cores. In Los Angeles, the CECIL Hotel was transformed into affordable housing, responding to urgent social needs. In the US more broadly, numerous former chain hotels, such as CROWNE PLAZA or HOLIDAY INN properties, have been successfully converted into micro-apartments, co-living spaces, or affordable housing. These examples show how adaptive reuse of hotel stock has become a widespread strategy to address contemporary challenges.

Polish cases of hotel transformation are emerging as well, with the FORUM Hotel in Kraków, closed and abandoned in 2002, representing a particularly relevant example (Figure 2).

This modernist landmark, once the most recognizable hotel in Poland, is currently the object of architectural discussion regarding its possible transformation into a different facility [23]. This shift from hospitality to other use signals a growing interest in reprogramming mid-to-late 20th century hotels in Poland, making it an important field of investigation for future research. Currently, no methodological studies have been conducted on this typology of buildings and their reuse possibilities, which may be identified as one reason why the reuse process seems somewhat delayed, representing a significant research gap. The evidence from international contexts demonstrates that adaptive reuse is not only feasible but also increasingly favored as a sustainable and culturally valuable design strategy, offering strong justification for examining the transformation potential of Poland’s hotel stock in more detail.

1.3. Characteristics of Mid-to-Late 20th Century Hotels in Poland

Most modernist hotel buildings in Poland were constructed in the 1960s and 1970s, under strong pressure for rapid, economical construction driven by post-war reconstruction, industrialization, and urban migration. This affected both technical quality and architectural standards. The regulations of the time (primarily: Regulation of the Chairman of the Committee for Construction, Urban Planning and Architecture of 21 July 1961 on the technical conditions to be met by general construction buildings) did not address thermal protection, resulting in single-layer external walls, often with decorative cladding but without insulation. Large-panel construction suffered from production inaccuracies, creating thermal bridges at slab joints, corners, and other vulnerable points. Uneven settling, combined with fast construction, further aggravated these issues. In addition, accessibility requirements were absent, leaving buildings difficult or impossible to use for users with mobility impairments.

A common issue among analyzed hotels is their progressive deterioration, which significantly limits preservation and adaptive reuse. Many hotels experienced decades of poor maintenance due to ownership changes after 1989 or long abandonment, leading to advanced degradation [24]. Economically built hotels often deteriorated to the point where renovation is questionable environmentally and financially. For instance, the CRACOVIA Hotel in Kraków, despite an architectural competition in 2023, faced severe structural and biological issues—including fungal infestation, reinforcement corrosion, and insufficient fire resistance—requiring extensive replacement of the building fabric, except for the main entrance and staircase [25].

Across Europe, mid-20th-century architecture is increasingly recognized as cultural heritage. Frameworks such as the Granada Convention (1985), Faro Convention (2005), and UNESCO Historic Urban Landscapes (2011) promote integrated conservation, combining legal and financial tools with community participation and landscape-scale value assessment [26,27,28]. These instruments support revitalization by improving coordination, accelerating decisions, and increasing predictability. In Poland, the 2003 Act on the Protection and Care of Monuments, heritage inventories, and institutional programmes reinforce modernist architecture protection. Various initiatives also raise public awareness and social capital around preservation and adaptive reuse [29]. Although communist-era architecture was long viewed as “unwanted heritage,” conservation debates now emphasize value-based assessment. Contemporary evaluations consider material and technical authenticity, spatial integrity, and the role in collective memory. Consequently, mid-to-late 20th-century hotels are recognized both as technical challenges and as cultural resources, whose revitalization contributes to urban identity and sustainable development [30].

1.4. Aim of the Research

The preservation and adaptation of Polish modernist hotels from the second half of the twentieth century remains highly unfavorable. Investors often hesitate due to limited public support, and in the absence of clear evaluation tools, demolition frequently prevails over reuse. Valuable examples, such as the SUDETY Hotel in Jelenia Góra, have been irreversibly lost [31,32]. This underscores the urgent need for systematic research and practical guidelines.

Developing a framework to assess the architectural and environmental potential of these buildings could improve decision-making for investors and public authorities, supporting cultural heritage protection and socio-cultural sustainability. Many hotels remain in limbo, neither adapted nor demolished, highlighting the research necessity [33]. The study focuses on challenges and opportunities of adaptive reuse in this building typology, addressing key questions:

- To what extent can mid-to-late 20th century Polish hotels be adapted to new functions, considering spatial, structural and installation factors?

- What scope of intervention is required to implement new uses?

- Can adaptive reuse be considered sustainable, especially using ‘low-tech’ architectural strategies?

- What are the environmental benefits of adaptive reuse in the fields of ecological, socio-cultural, functional or economic aspects?

The research aims to determine whether adaptive reuse of modernist hotels in Poland is environmentally feasible and competitive with new construction, reducing construction impact while offering a sustainable alternative. The study approaches sustainable development primarily from an architectural perspective. Rather than analyzing and dissecting technologically advanced installation systems, the focus is on ‘low-tech’ architectural strategies that can meaningfully contribute to long-term environmental responsibility.

2. Methods

Given the substantial similarities identified among the existing hotel buildings, the applied research method is based on analyzing available data with reference to distinct groups of problem areas. These groups were extracted from the broad domain of sustainable development and intentionally narrowed to those aspects that can be meaningfully influenced by architectural, low-tech intervention within adaptive reuse projects.

Within each group, specific problem areas were further identified. These represent domains in which architectural decisions have the potential to shape the final outcomes of an adaptive reuse investment’s sustainability performance. These problem areas constitute the analytical framework for the study.

The adopted method is not intended as an exhaustive case-study review of all adaptive reuse projects of this type. Instead, it examines aspects selected—based, among others, on data availability—across representative examples in order to establish patterns and demonstrate the feasibility and recurring potential of such interventions. The aim, therefore, is not to analyze every building individually, but to identify the capacities and constraints within each problem area that may be extrapolated to a wider group of buildings sharing the same typology. In this sense, the method provides a structured foundation for future, more detailed investigations and may guide preliminary assessments at the early stages of possible investment processes.

Because the problem areas differ in nature, the methodological tools employed also vary accordingly. For factors of a quantitative character—such as the thermal performance of partitions or embodied-carbon retention—computational assessment methods were used to quantify potential benefits and risks. For a wide range of qualitative or “soft” factors, common in architectural analysis, expert evaluation of selected examples was applied to identify design opportunities and limitations specific to each problem area. Finally, when addressing evaluation pathways, the study employs an examination of the LEED framework as a comparative tool, highlighting where adaptive reuse can more easily achieve sustainability credits relative to new construction, and where such credits present greater challenges.

The problem groups, problem areas within them and adopted analysis methodologies were summarized in the table below (Table 1). Established methodology, although structured for the purpose of this research, can equally serve as a replicable assessment framework in different buildings’ typologies and in separate geographical regions.

Table 1.

A summary of problem groups, problem areas within each group, and adopted analysis methodologies.

3. Materials

The buildings used as examples to analyze the research problem are similar in terms of their original function (hotel), geographical location and date of construction. All of them were built in Poland in the 1960s, 1970s and early 1980s, i.e., at a time when the country was a non-sovereign socialist republic. The examples refer to buildings that have been rebuilt or converted and adapted to a new function in the last decade. The analysis also includes examples of hotels that have been out of use for years and remain empty although they are located on attractive plots and their future is widely discussed in architectural circles, by municipal authorities and interested investors. Additionally, the study points out examples of buildings that share similar typology and continue their operations as hotel facilities after minor renovations (Table 2).

Table 2.

The overview of examples of hotel buildings.

The extensively analyzed cases were intentionally selected to represent a range of urban locations, building sizes, and intervention scenarios, including completed conversions and unrealized but extensively studied redevelopment proposals. Together, they reflect recurring architectural, structural, and regulatory conditions characteristic of mid-to-late 20th-century hotel buildings in Poland, allowing typological patterns to be identified rather than isolated case-specific outcomes.

The research materials were obtained mainly from specialist and scientific literature. In some cases, archival documentation and professional reports made available to interested parties during architectural competitions for building adaptation projects were used. These materials included expert opinions and reports from on-site inspections and local surveys. Additionally, in some cases, construction documentation was provided by the owners or managers of the completed projects.

The collected materials are discussed in more detail in the following sections of the study. Section 4 (Urban and architectural characteristics) describes the functional, formal and structural solutions characteristic of the analyzed type of buildings, as well as aspects of their location in urban structures. Presenting this overview serves as an introductory part and aims to outline general, recurring architectural principles characteristic of this era, thereby providing essential contextual understanding. Section 5 (Results) presents the obtained and employed materials together with findings, in a correlated narrative conducted in line with the established research methodology.

4. Urban and Architectural Characteristics

4.1. Preferable Locations

Hotels built in the 1960s–1980s were usually located in the city centre. Typically, they were situated in the city centre (Hotel METROPOL in Warsaw), on the main thoroughfares of the city and in close relation to the Old Town (Hotel MERKURY in Poznań, Hotel SKANPOL in Kołobrzeg) [34,35]. Located close to the historic part of the city, services, green areas and transport stations (railway, bus), they were intended to provide residents and tourists with good accessibility, such as the STOBRAWA Hotel in Kluczbork. This building, located about 500 m from the main square and in the neighborhood of a park, is an example of the integration of hotels with the urban structure (Figure 3). The proximity of various types of services further increases their attractiveness, despite occasional inconveniences such as traffic noise along the main roads.

Figure 3.

The location of STOBRAWA Hotel in Kluczbork, with reference to the city center (compiled by Katarzyna Zawada-Pęgiel based on https://earth.google.com, accessed on 27 October 2025).

4.2. Formal and Functional Typology

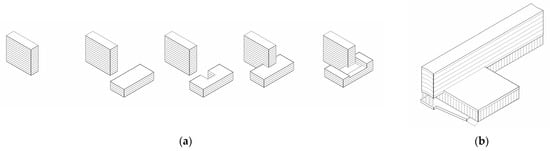

Hotels inspired by modernism and brutalism, designed according to the standards and spatial and functional solutions of the time, often took on similar forms. Most commonly, these buildings were designed in simplified geometric forms—standing or lying prisms, with rectangular floor plans and often extended podiums (Figure 4). When analyzing the dimensions of the buildings, one can notice vertical towers several stories high (e.g., the STOBRAWA hotel) with or without a podium, as well as horizontal, compact blocks with several stories and pavilions of various configurations and scales (e.g., the CRACOVIA hotel, the FORUM hotel) [36,37].

Figure 4.

Typical geometric forms of the buildings: (a) Building masses: from simple (left) to complex (right); (illustration by Anna Taczalska-Ryniak based on: Charytonow, E. Projektowanie architektoniczne, 4th ed.; Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne: Warsaw, Poland, 1980; p. 44.) [36]. (b) An example of a Cracovia Hotel: a slender cuboid positioned horizontally on an extended pavilion-shaped podium (illustration by Anna Taczalska-Ryniak).

A characteristic of hotel buildings is the clear distinction between the lower floors and the upper residential segments. The lower floors, segments (beyond the main form) were usually glazed over their entire height. Intended for lobbies, restaurants, conference rooms and nightclubs, they are characterised by an open plan and flexible construction systems. The upper segments, intended for residential functions, are characterised by repetitive solutions and a rigid structural system based on walls.

Hotels constructed as modular, segmented, or prefabricated systems, exhibit geometric façades (arrangement and proportion of windows, spandrel spaces, details) (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Despite their repetitiveness, the buildings have distinctive features, such as prominently cantilevered entrances and multi-level staircases, which accentuate and emphasise the size and prestige of the building.

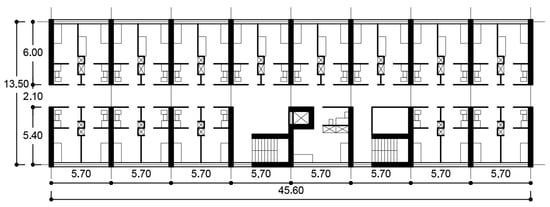

The interior arrangement of hotels is also standardised and modularised. Based on the technical design standards of the time and reference units (a single hotel bed, functional components and equipment), corresponding unit sizes were applied, with modular dimensions including: 2.40–3.60 × 4.80–6.00 m (increased by a module of 0.60 m) [36]. This means that typical unit areas ranged from approximately 11.50 m2 to 24.00 m2 (Figure 5 and Figure 6), and within a wall-based structural system with a 5.70–6.00 m span, two rooms could have been accommodated per module (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

The rigid modularity of a typical hotel floor plan (illustration by Marek Bystroń, based on information from: Charytonow, E. Projektowanie architektoniczne, 4th ed.; Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne: Warsaw, Poland, 1980; p. 192) [36].

Figure 6.

Examples of typical hotel room arrangements: (a) two rooms within a 5.7 m modular structural layout (illustration by Marek Bystroń, based on information from: Charytonow, E. Projektowanie architektoniczne, 4th ed.; Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne: Warsaw, Poland, 1980; p. 192); (b) different standard rooms and their connection to modular dimensions (illustrated by Marek Bystroń, based on information from Charytonow, E. Projektowanie architektoniczne, 4th ed.; Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne: Warsaw, Poland, 1980; p. 194) [36].

The standardization of architectural modules also applies to the height of structural segments. Analysis of examples shows that the net heights of the original structures were typically around 2.5 m. In the BRDA Hotel, the height between structural slabs of the residential floors was initially 2.55 m, while in the STOBRAWA Hotel, floor heights in the residential part ranged around 2.56 m [38]. In the FORUM Hotel, floor-to-ceiling heights varied between 2.20 and 2.48 m [39,40]. From the perspective of contemporary construction standards, such heights are generally at the lower end of the functional range, limiting flexibility for certain modern requirements but reflecting the architectural and technical norms of the period.

4.3. Structural Typology

The structural typology of the hotel buildings is based on a mixed structural system combining monolithic and prefabricated elements.

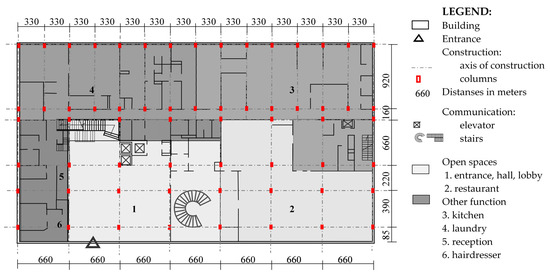

The underground levels were typically built as hybrid, monolithic wall-and-column structures arranged in a nearly square grid with a span of approximately 5.5–6.0 m. The ground floors were constructed as skeletal column-beam or column-slab systems, which provided both flexibility and architectural openness (Figure 7). Similar structural systems, including frames, trusses and stiffening walls, were used for pavilions and parts of the building extending beyond the main building area.

Figure 7.

The plan of the ground floor of HELIOS Hotel in Toruń, designed in the 1970s. Illustration of a hybrid structural system of load-bearing columns and walls, providing open spaces in the lobby, restaurant and other functional areas (illustration by Katarzyna Zawada-Pęgiel based on: Charytonow, E. Projektowanie architektoniczne, 4th ed.; Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne: Warsaw, Poland, 1980; p. 198) [36].

The structure, comprising the hotel room sections, consists predominantly of wall-based systems, typically employing prefabricated transverse load-bearing walls positioned perpendicular to the external façades, forming two-bay structural layouts.

Two trends are visible in the analyzed examples: the podium and the upper accommodation floors. Complex transfer systems—such as beam grids, waffle slabs, or shear-transfer structures—were often introduced between these sections to redistribute loads from the superstructure to the column grid of the podium. These transfer zones frequently reached considerable heights; for instance, in the BRDA Hotel, the height of the transfer structure measured approximately 2.12 m [41] (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

The cross-section of BRDA Hotel, with indication of the characteristic transfer structural system (Illustration by Katarzyna Zawada-Pęgiel based on Architectural design documentation for the conversion of a BRDA Hotel into a residential building with services on the ground floor and first floor).

5. Results

5.1. Environmental and Ecological Sustainability

5.1.1. Operational Energy Performance

Initial research points out that modernist buildings constructed mainly in the 1960s and 1970s are structures with low passive energy efficiency, characterized by significant heat transfer through external partitions, as well as door and window openings. Their reuse requires a substantial increase in their energy efficiency, primarily through the use of passive protection methods, and this is a necessary action in any reconstruction, modernization and adaptation project.

Below is a computational analysis and comparison of building envelope transmission losses, before and after adaptive reuse, using the BRDA as an example. The analysis compares external walls’ and windows’ thermal transmission as a key factor among low-tech solutions that affects the overall energy efficiency (Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5). The calculations are limited to passive heat transfer through external walls and windows and do not account for ventilation or infiltration losses, thermal bridges, system efficiencies, or operational and control strategies. The BRDA is considered a representative example of its typology, as it is characteristic of the period in terms of massing, façade articulation, and spatial assumptions, and it has already undergone adaptive reuse, enabling direct comparison and verification of envelope performance before and after intervention.

Table 3.

Calculation of the heat transfer coefficient (U) for an external wall before and after adaptive reuse for BRDA Hotel.

Table 4.

Calculation of heat loss H [W/K] through external walls, for the entire BRDA Hotel.

Table 5.

Calculation of heat loss H [W/K] through windows, for the entire BRDA building.

The heat transfer coefficient of the building before adaptive reuse is 3.94 times greater than that of the building after adaptive reuse.

After adaptive reuse, the heat loss coefficient drops from approx. 3123 W/K to approx. 832 W/K, which means that heat loss through the walls is reduced by about 73%.

After replacing the windows, the heat loss coefficient drops from approx. 4306 W/K to approx. 1368 W/K, which means that heat loss through the windows is reduced by about 68%.

In summary, prior to adaptive reuse of the BRDA building, heat loss through the walls and windows of the building amounted to 7.4 kW (for every degree difference between the external and internal temperatures), whereas after adaptive reuse this value is 2.2 kW. This means a reduction in transmission losses of approx. 70.3%.

The technical and construction regulations in force in the 1960s and 1970s allowed for the construction of buildings that were highly energy inefficient. Reusing these buildings today requires a thorough reconstruction of the external partitions, including, above all, the addition of thermal insulation and the replacement of woodwork. It is therefore primarily an investment challenge that should be taken into account during the planning process.

5.1.2. Material Circularity

Modernist buildings adapted today mostly date from the 1960s–70s, making their life cycles 50–60 years old. Conversions rely on reusing existing materials and structures, extending building life and supporting circular economy principles.

In practice, reuse is often limited by poor structural condition. Durable elements like aluminum or prefabricated concrete panels can be preserved, while seals, fittings, timber, and paint degrade quickly. Curtain-wall and composite façades often need specialized restoration—dismantling, over-cladding, structural injections, or secondary glazing—which raises costs but usually retains a better carbon balance than full replacement [43,44].

A further challenge concerns the poor and substandard quality and composition of construction materials used during the communist period in Poland. Moreover, some contain hazardous substances, such as asbestos or other materials emitting volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which must be safely removed and disposed of rather than reused, which limits the implementation of circular economy strategies.

Adaptive reuse thus offers both opportunities—extending life, reducing embodied carbon, preserving cultural value—and challenges, including degraded or hazardous materials, high refurbishment costs, and outdated systems. Effective adaptation requires careful life cycle assessment and design strategies balancing environmental performance with architectural integrity, considering investment budget at the same time.

5.1.3. Embodied Carbon Retention

Whole-building LCA analyses repeatedly show that the renovation or adaptation of existing buildings can reduce the total environmental impact by several dozen per cent compared to demolition and new construction. Studies indicate reductions of around 50% to 75%, depending on the assumptions made and the scope of works conducted.

Below, an example of the reconstruction of the BRDA hotel has been analyzed to assess its environmental impact (Table 6 and Table 7). The environmental impact of the existing building undergoing reconstruction has been compiled and compared, and the environmental impact of demolishing the existing building and replacing it with a new one, identical to the one being reconstructed, has been analyzed. Simplified calculations were used—comparing the carbon footprint of the production of building components, broken down by main building materials. Transport, construction, use and final demolition processes were not included.

Table 6.

Calculation of the carbon footprint (CF) for BRDA Hotel—after adaptive reuse.

Table 7.

Calculation of the carbon footprint (CF) assuming the demolition of the existing BRDA Hotel and reconstruction of an identical twin building.

In summary, a comparative analysis of two scenarios for the development of the BRDA Hotel—the renovation of the existing building and its complete demolition and construction of a new twin facility—indicates a clear environmental advantage for the adaptation option.

The total (simplified) carbon footprint of the reconstruction is 80,120 kg CO2e, while in the demolition and new construction scenario it reaches 1,689,909 kg CO2e. This means that the ‘demolish and build’ option generates approximately 21 times higher emissions, and the use of an adaptation strategy allows for a 95% reduction in the carbon footprint. These results confirm that extending the life cycle of existing building structures—through modernization and change in function—is one of the most effective tools for reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the construction sector.

The possibility of preserving individual elements depends on their original function and location. As noted in the “Material Circularity” section, it is generally easier to retain structural components with relatively large cross-sections and no direct weather exposure than façade or interior finishes subject to daily use.

In new buildings, structural elements (sub-and superstructure) are the main carriers of embodied carbon, averaging ~65% of the footprint in office buildings (48% superstructure, 17% foundations), compared with ~16% for façades and ~4% for interior finishes. Retaining the load-bearing structure therefore preserves far more embodied carbon than simply overcladding an existing façade [45]. Preserving foundations, cores and floor slabs can retain ~40–65% of the total footprint of a typical new building of this scale, depending on typology. For mid- to late-20th-century hotels with reinforced concrete structures, the priority is thus to maintain the structural grid (foundations, cores, slabs) and replace the cladding, as shown by the conversion of the STOBRAWA Hotel in Kluczbork into housing, where practically only the reinforced concrete structure was retained (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Subsequent phases of the STOBRAWA Hotel life cycle: (a) the original condition as of 10 June 2015 (source: https://nto.pl/hotel-stobrawa-wystawiony-na-sprzedaz-to-najwyzszy-budynek-w-kluczborku/gh/c1-4713931, accessed on 12 October 2025); (b) the construction phase in 2022 (source: https://radio.opole.pl/100,629113,kluczborski-hotel-stobrawa-w-przebudowie-a-miesz, accessed on 12 October 2025); (c) the current state after modernization as of 18 August 2025 (source: https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=1188524946645209&set=a.552894753541568, accessed on 12 October 2025).

Maintaining the existing structural layout can significantly improve the building’s energy balance, provided that:

- The new function can be fitted into the existing structural grid, which is difficult in typical hotel superstructures with dense load-bearing walls between every or every second room;

- Functional requirements are compatible with available storey heights, which is challenging given relatively low ceilings (Polish regulations usually require a minimum net height of 2.5 m);

- The predicted live loads are compatible with the existing structure. In Poland, hotels designed to PN-82/B-02003 [46] typically assumed 1.5 kN/m2 for guest rooms and bathrooms, while current Eurocode 1 (PN-EN 1991-1-1) [47] recommends 1.5–2.0 kN/m2 for rooms in residential, hospital and hotel buildings, 2.0–3.0 kN/m2 for offices, and 3.0–4.0 kN/m2 for areas with fixed seating such as conference or lecture rooms.

This summary shows that the structure of former hotel buildings often no longer meets current requirements for functions other than residential and hotel use, which can significantly hinder the process of conversion to other functions. Hence, maintaining the existing structural tissue, as a major partition for prospective carbon retention limitation, is conditionally subjective to the planned functionality of the building after its redevelopment.

5.2. Socio-Cultural Sustainability

5.2.1. Heritage Value Retention, Urban Identity and Placemaking

From a socio-cultural perspective, sustainable development relies on preserving and activating heritage values to ensure long-term, socially acceptable, and ecologically and economically rational interventions [5]. In adapting mid-20th-century Polish hotels, the focus is on retaining heritage—honoring the architectural significance of modernism and postmodernism and engaging local communities in the design process.

A key challenge is the status of such buildings as ‘unwanted heritage.’ Public perception is often mixed, as seen after the 2006 demolition of the SUPERSAM store, highlighting debates over post-war modernism and the concept of dissonant heritage-material remnants of contested eras with overlapping, sometimes uncomfortable narratives [48].

Late 20th-century hotels, such as the POLONEZ in Poznań, BRDA in Bydgoszcz, and WIENIAWA in Wrocław, carried social, entertainment, and representative functions, generating positive memories and local identity. This symbolic capital fosters social acceptance, stakeholder engagement, and effective heritage interpretation, increasing the likelihood of successful adaptive reuse.

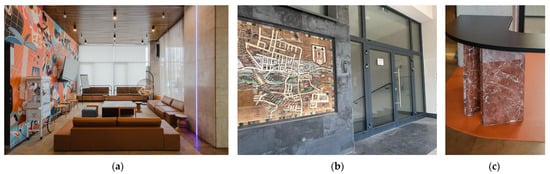

Even when disused, these buildings retain historical and social significance. Adaptive reuse can reactivate their potential on a macro scale—preserving overall structures, like the STOBRAWA Hotel’s undulating roof—and on a micro scale (Figure 9)—retaining interiors, décor, or furnishings, as in the POLONEZ Hotel’s granite pillars, slatted ceiling, and marble floor, or STOBRAWA’s ceramic city map and corridor graphics (Figure 10). Micro-scale reuse can also transform existing elements for new functions, supporting sustainable development and the circular economy.

Figure 10.

Examples of micro-scale heritage preservations: (a) the interior of POLONEZ Hotel in Poznań, with original granite cladding on the pillars, slatted ceiling and marble floor (source: https://sztuka-wnetrza.pl/galleries/thumbsfit_in_900x600/_DSC836-HDR.jpg, accessed on 12 October 2025); (b) the original ceramic map of Kluczbork near the entrance to STOBRAWA apartments—former STOBRAWA Hotel (source: https://www.booking.com/hotel/pl/apartament-stobrawa.pl.html?chal_t=1760815593478&force_referer=&activeTab=photosGallery, accessed on 18 October 2025); (c) the reuse of red marble cladding recovered during renovation process as a support for the reception counter in POLONEZ Hotel (source: https://www.whitemad.pl/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Student-Depot-Poznan-16.jpg, accessed on 18 October 2025).

Heritage authorities play a key role in protecting mid-20th-century hotels through formal tools (register entries, conservation decisions) and methodological instruments (value assessments, change management plans, material guidelines). While this ensures clarity and predictability, it can limit functional flexibility and increase costs and risks, requiring close designer–conservator cooperation, compatible technologies, budget reserves, and parallel funding.

The planned adaptive reuse of the CRACOVIA Hotel in Kraków illustrates this approach. An architectural competition aimed to convert the building into a Museum of Design and Architecture and a Model Centre for Creative Industries was largely influenced by conservation guidelines from the Municipal Conservator of Monuments. These included:

- Replacing deteriorated parts and reconstructing them in original form,

- Preserving key elements of the ground floor, mezzanine, and basement, including the entrance hall, mosaic, decorative ceilings, and former ORBIS office,

- Reconstructing façades and architectural details such as window divisions, proportions, articulation, and color scheme,

- Restoring the former restaurant and banquet areas with characteristic openwork façades [49,50].

This shows respect for the CRACOVIA Hotel’s architectural and cultural value. Cooperation with heritage authorities creates a structured adaptation framework: while strict conservation limits flexibility and raises costs, it ensures a predictable process with designer–conservator partnership, reversible technologies, and potential funding. The hotel exemplifies a ‘conservative transformation,’ where preserving key attributes enables new cultural functions, enhancing socio-cultural sustainability.

A synthesis of recurring challenges and opportunities across key examined cases is represented in Table 8.

Table 8.

A synthesis of recurring heritage value retention, urban identity and placemaking challenges and opportunities across key cases.

5.2.2. Accessibility

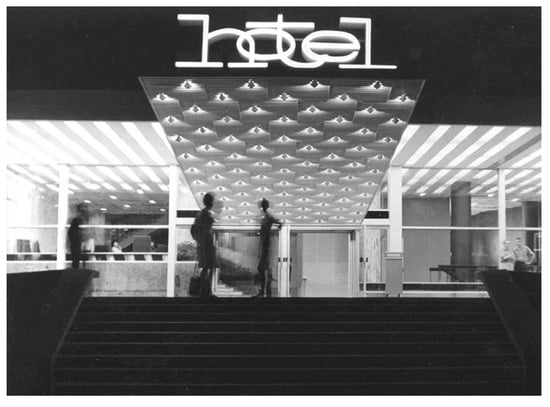

Hotels built in the 1960s and 1970s often have accessibility issues. Raised ground floors, designed to allow partially recessed basements and enhance prestige, meant entrances were reached only by steps. While the grand staircases highlighted the main entrance, they blocked access for people with reduced mobility (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

The representative, raised-above-ground-level entrance to the CRACOVIA Hotel in Krakow, photograph from the 1960s (source: https://niaiu.pl/hotel-cracovia/, accessed on 12 September 2025).

Inside, the building also posed serious accessibility challenges for people with disabilities. Reception desks were too high for wheelchair users, and hotel rooms were not designed for limited mobility. Technical standards at the time did not require accessible design. A standard room module of 5.70–6.00 m housed two double rooms with bathrooms 1.45–1.46 m wide—just below today’s minimum maneuvering space of 1.5 by 1.5 m [36]. Entrance doors were narrow (0.8 m), and corridors, especially after installing wardrobes, were only slightly wider than the doors (Figure 5 and Figure 6).

Modern regulations now require accessibility in both new buildings and adaptive reuse projects. The 2020 Regulation of the Minister of Development, referencing the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, mandates accessibility, including for the elderly. The 2004 Regulation on hotel facilities and the 2002 Regulation on technical building conditions specify requirements for entrances, lifts, and circulation spaces. Design manuals also emphasize removing technical barriers like steps, thresholds, and slippery floors, while ensuring safety, comfort, lighting, and signage [51,52,53].

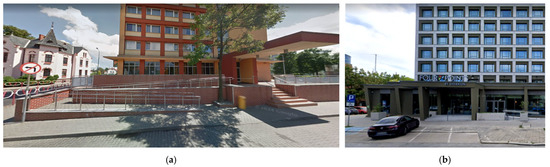

Consequently, any conversion of an older hotel to a modern hotel or new function must improve accessibility. A common example is adding dedicated wheelchair ramps at building entrances (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Examples of dedicated ramps constructed during adaptation processes: (a) The QUBUS Hotel in Złotoryja, formerly known as Hotel GOLD (source: https://earth.google.com, accessed on 23 October 2025). (b) The FOUR POINTS BY SHERATON Hotel in Wrocław, formerly known as WIENIAWA Hotel (source: https://earth.google.com, accessed on 23 October 2025).

Newly built hotels use larger design modules, mostly: 3.00 m, 3.60 m, 3.90 m and 4.20 m. They result primarily from the standard of the facility, the adopted structural axis spacing in the building and the technology used in its construction. In the analyzed examples of the conversion of modernist hotels into modern facilities, there is a tendency to enlarge residential units, including, in extreme cases, connection of original adjacent rooms [53] (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

One of the rooms at the FOUR POINT BY SHERATON Hotel in Wrocław (formerly WIENIAWA Hotel). The photo shows the opening left after the demolition of a wall that formerly separated two independent residential units (source: https://www.horecabc.pl/nowy-four-points-by-sheraton-otwarty-we-wroclawiu/, accessed on 12 October 2025).

Demolition of partition walls is common in converting modernist hotels to new functions. For example, the BRDA Hotel in Bydgoszcz was adapted to mixed office and residential use by removing most non-load-bearing walls, allowing functional layouts and compliance with modern technical standards, including accessibility—wider doors and corridors, an enlarged shaft for a lift for stretchers and disabled persons, and accessible sanitary facilities.

Accessibility issues in 1960s–70s hotels fall into two categories: structural elements (e.g., elevated ground floors, narrow corridors) requiring major alterations like ramps, and replaceable finishes or furnishings (e.g., handrails, furniture) typically addressed during renovations. While the first may demand significant interventions, the second has less impact on sustainability considerations. A synthetic summary of recurring barriers across key cases is presented in Table 9.

Table 9.

A synthesis of recurring accessibility challenges across key cases.

5.3. Spatial Flexibility and Adaptability

The spatial adaptability of mid-20th-century hotels is key to their potential for sustainable transformation. Internal reconfigurations depend on structural systems, floor heights, and circulation, with flexibility supporting longer building lifespans, reduced demolition waste, and resource optimization [54,55].

Polish hotels from the 1960s–1980s were mainly reinforced concrete—wall-bearing, frame, or mixed—with modular spans of 5–7.5 m, limiting flexibility compared to modern skeleton-frame structures (with spans of 6–9 m). Most used mixed systems, which now aid adaptive reuse: podiums suit commercial or office functions, while upper parts convert to residential or dormitory use.

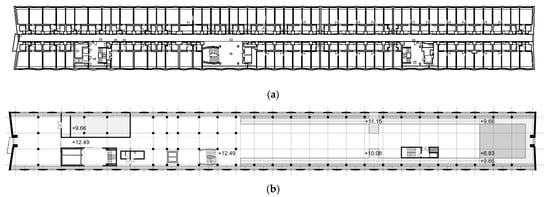

Examples such as the BRDA and STOBRAWA Hotels illustrate this logic. In the first one, the podium was converted into retail and office spaces, while the twin towers were transformed into apartments. STOBRAWA’s higher section was adapted for residential use, and the lower segment for services, including a kindergarten (Figure 14). Similar approaches were applied in WIENIAWA and IKAR hotels, where the removal of non-loadbearing partitions and the merging of two or more rooms enabled the creation of contemporary housing units. These cases demonstrate that functional continuity between the original and new uses—such as the transformation of hotels into apartments, student housing, or upgraded hotels—reduces the need for deep structural interventions, minimizes embodied carbon, and lowers construction waste, aligning with sustainable retrofit principles.

Figure 14.

The plan views of STOBRAWA hotel ground floor: (a) pre-development inventory; (b) construction design stage, with kindergarten technology incorporated into the former banquet hall (source: materials provided by the Stobrawa Apartments LLC, DeSilva Development).

More radical conversions, like turning the CRACOVIA Hotel into a cultural institution, require significant structural changes, including partial demolition of load-bearing elements and full interior reconstruction (Figure 15). While preserving the exterior and architectural character, such interventions raise economic and environmental concerns due to high material replacement and embodied carbon footprint.

Figure 15.

A comparison of floor plans of the CRACOVIA Hotel demonstrating the extensiveness of planned intervention into existing structure: (a) architectural survey (source: Matejko, M. Inwentaryzacja architektoniczna Hotelu Cracovia, 2017). Załącznik merytoryczny M10 konkursu Hotel Cracovia—Konkurs SARP Nr 1039 (source: https://sarp.krakow.pl/2023/05/04/hotel-cracovia/, accessed on 3 August 2025); (b) a winning proposal by Lewicki Łatak Design Office in the architectural competition for the concept of renovating the former CRACOVIA hotel into a cultural institution: the Museum of Design and Architecture and the Model Centre for Supporting Creative Industries, (source: https://www.architekturaibiznes.pl/konkurs/i-nagroda-cracovia,30805.html#lg=1&slide=3, accessed on 30 October 2025).

The internal communication system strongly affects hotel adaptability. Many mid-20th-century hotels have central vertical cores with long corridors, complicating functional changes. In the BRDA Hotel, lift shafts were added and new horizontal routes created; STOBRAWA improved existing circulation and linked it to underground facilities. Often, communication systems do not meet current regulations, requiring additional lifts, ramps, alternative escape routes, or regulatory exemptions.

Floor height remains another determining factor of flexibility. Upper hotel floors typically offer structural heights of 2.50 to 2.55 m, which, after including acoustic and installation layers, result in effective ceiling heights of about 2.45 m—merely adequate for residential use (still requiring formal exemption from technical regulations) but insufficient for office or public functions. Ground floors and podium zones, by contrast, often have heights exceeding 3.0 m, enabling the introduction of service, commercial, or coworking uses. The characteristic, intermediate transfer floors between the ground floor and the residential parts offer two possibilities of new functional designations: as an additional height for large volumes on the ground floor, or as a technical void to facilitate the distribution of ventilation and other installations (Figure 8).

Recent adaptations favor residential and service uses—apartments, student housing, coworking spaces—while cultural reuse is less common but important for heritage preservation. Repetitive modular layouts support standardization, prefabrication, and efficient retrofitting, aligning with sustainable design principles.

Challenges remain: low floor heights, central cores, long corridors, structural walls, and prefabricated elements limit flexibility and installation of new systems, often requiring exemptions from fire or acoustic regulations. Mixed structural systems offer the most flexible reuse, combining lower-floor services with upper-floor residences. Adaptation extends building lifespan, preserves urban and social identity, and reduces environmental impact, but balancing technical compliance, economic viability, and heritage integrity is essential for sustainable transformation.

5.4. Process-Related Sustainability

5.4.1. Design Innovation

Interventions in existing buildings may seem limiting at first, but the constraints of the pre-existing environment can foster innovative design. Creative approaches enable effective use of the existing fabric, allowing sustainable development that minimizes disruption while maximizing functional and aesthetic potential.

Examples of projects and implementations involving the adaptive reuse of Polish hotels from the previous political era further illustrate this point. For instance, in the renovation of a workers’ hotel in Opole, which was transformed into the headquarters of the ARTPUNKT Center for Artistic Education, the design introduced a secondary façade to complement the existing building structure. This intervention enabled more deliberate control over heat gains and losses through the external envelope, thereby improving the building’s energy performance [56] (Figure 16).

Figure 16.

The double Skin Façade on the ARTPUNKT building in Opole. With an innovative design approach, the building gained a new architectural character and improved energy performance simultaneously (source: https://www.archiweb.cz/en/b/artpunkt-centrum-umeleckeho-vzdelavani-centrum-edukacji-artystycznej, accessed on 26 September 2025).

Examples of innovative design are evident in proposals for the CRACOVIA Hotel adaptation, which creatively repurpose existing structural elements and spatial layouts. In one proposal by CHYBIK+KRISTOF, AKE Studio, and Kuba Snopek, hotel room structures and the distinctive “box-shaped” transfer slab were adapted as exhibition spaces (Figure 17). Similarly, at the BRDA Hotel in Bydgoszcz, a transfer slab was used to house modern building systems, enhancing the building’s environmental performance.

Figure 17.

A rendering from the 2023 competition entry by CHYBIK+KRISTOF, AKE Studio and Kuba Snopek for the adaptation of the CRACOVIA Hotel to the Museum of Design and Architecture. A design approach that utilizes the structure of former hotel rooms and the interior of a technical double floor structure as a space for exhibits, while simultaneously creating additional exhibition spaces within the new fabric of the building (source: AKE Studio collection).

5.4.2. Monitoring and Evaluation

Although sustainability certification for hotels and complex adaptations is still uncommon in Poland, the growing demand for measurable environmental performance has increased interest in multi-criteria systems such as LEED. Because LEED applies uniform criteria to both new buildings and major renovations, it enables objective comparison of investment strategies early in the analysis. A review of LEED v5 BUILDING DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION (BD+C) shows that most requirements can be met similarly by new and renovated buildings, though some credits may be easier or more difficult to achieve when adapting existing hotels to new uses (Table 10) [57].

Table 10.

A classification of credits selected as not equally achievable for new constructions and major renovations—from LEED v5—Building Design and Construction (BD+C): New Construction and Major Renovations.

The analysis indicates that certain aspects of sustainable development are inherently more difficult to achieve in the process of renovating and adapting existing hotels for new functions. Nevertheless, the certification system emphasizes a set of factors that can significantly contribute to reducing the carbon footprint of such investments. For investors, conducting this type of assessment at a very early stage of the project and confronting it with economic considerations may provide valuable support and strengthen the credibility of pursuing adaptive reuse as a viable development strategy.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

In order to carry out the planned study, several thematic groups were first identified, covering environmental and ecological, socio-cultural, functional and spatial and process issues. Within each group, specific criteria for analysis and comparison were recognized. Next, research methods were selected for the criteria and thematic groups, including either quantitative measures, where possible, or professional assessment of non-measurable aspects. The study primarily analyzed low-tech architectural solutions, i.e., design and investment measures that do not require buildings to be equipped with advanced installation systems. The study was based on data from literature, press reports and technical documentation of buildings. Its aim is to outline the key capacities and constraints typical of a particular building typology. In doing so, it provides a structured basis for further studies and can support preliminary assessments in early investment stages. The set of criteria and research method developed can also be reused to evaluate a group of buildings of any function, in any geographical location.

The environmental and ecological aspects include criteria for operational energy performance, material circularity, and embodied carbon retention.

Based on the technical documentation obtained for the conversion and adaptation of the BRDA Hotel into residential premises, the heat transfer coefficients for external partitions were calculated and compared. The calculation showed that the conversion significantly improved these indicators. Currently, the external walls have a heat transfer coefficient that is 73% better than before the intervention, and the glass window sets have improved their parameters more than threefold.

It has been shown that the very fact of renovating a building originally constructed 50–60 years earlier extends its life cycle and is therefore beneficial from the point of view of the circulation of building materials, which, at least to some extent, remain reused. Moreover, their demolition and transport are not necessary, as they are used on site.

In the further part of the study, based on examples of completed investments, it was shown that the elements with the greatest potential for preservation are the load-bearing structures of reinforced concrete, which are largely resistant to the effects of time. The example of the reconstruction and adaptation of the BRDA Hotel also shows that reuse, even without taking into account the environmental impact of transporting building materials to the construction site, allows for a reduction in carbon dioxide emissions of 95%. At the same time, it was demonstrated that the use of this structure is possible provided that it remains in good technical condition and has a load-bearing capacity appropriate for its planned function.

The group of socio-cultural aspects analyzed included the preservation of the historical value of the buildings and their accessibility.

The importance of preserving the historical value of buildings that have played a socio-cultural and urban role over the years is demonstrated by the examples of the disused CRACOVIA and FORUM hotels in Krakow, whose future is widely discussed in architectural circles, by local authorities and interested investors. Although no decision has yet been made regarding their future, none of the parties involved are suggesting that they be demolished. Examples of completed investments of the researched building typology also demonstrate the value of preserving specific architectural details, both on a macro scale, such as the unique forms of pavilion roofs, and on a micro scale, such as historic mosaics and wall decorations.

Ways of adapting buildings to contemporary requirements in terms of accessibility, in particular for wheelchair users, have been described. Architectural solutions were presented, including the reconstruction of entrance areas and the adaptation of the width of passageways and corridors, as well as maneuvering spaces in general, and furniture solutions. It was demonstrated that, in accordance with the applicable regulations, this adaptation covered all of the completed adaptation investments. A significant improvement in the accessibility of the facilities after the reconstruction was therefore demonstrated.

The study of functional and spatial aspects included an analysis of the solutions implemented in completed investments. It was pointed out that it is necessary to adapt the communication layout, both horizontally in terms of corridor width and access length, and vertically in terms of supplementing the necessary communication shafts.

At the same time, it was demonstrated that the low usable height of the floors, standardized in the post-war period, essentially limits the possibility of adapting the former hotel floors to functions other than residential. In this regard, examples of the conversion of buildings for the purposes of a modern hotel and apartments were cited, and the possibility of adapting them to other collective residential functions (e.g., student halls of residence) was demonstrated.

The introductory chapter, devoted to the presentation and discussion of design principles common to late modernist hotel buildings in Poland, points out that they were designed on centrally located plots of land in cities. These locations remain attractive today, providing pedestrian access and excellent transport links to other parts of the city. Therefore, decisions regarding the future of these buildings should be approached with particular sensitivity—although over the years, their culture- and society-shaping role has been undermined.

It has been shown that preserving original architectural details, both on a macro and micro scale, can be a design innovation. Examples of completed investments and competition projects have also shown that even though the redevelopment of existing fabric is more difficult than building from scratch and requires a number of design challenges to be taken into account, it also offers the potential to create unconventional design solutions.

Multi-criteria certification of hotel facilities, especially those undergoing renovation, is still not popular in Poland, and none of the examples cited have been evaluated. Nevertheless, a simplified, hypothetical analysis was carried out using the criteria assessed during the LEED evaluation as an example. It was shown that in many areas, investments involving the renovation and adaptation of buildings are rewarded compared to new-build projects. This fact alone demonstrates the pro-environmental nature and potential of such projects.

The study therefore showed that the conversion and adaptation of late modernist hotel buildings in Poland is not only possible but also beneficial from an environmental point of view, especially when compared to projects involving the demolition of existing structures and their replacement with new ones. Generally, in all analyzed problem areas, the post-adaptation outcome proved that the adaptive-reuse contributes to sustainable development principles (Table 11).

Table 11.

Comparative evaluation matrix of adaptive reuse performance across established problem areas.

At the same time, however, several criteria for such conversions were identified, including, above all, the good technical condition of the existing load-bearing structure and its flexibility, sufficient to introduce a new or updated function in accordance with applicable regulations. As has been shown, in the case of former hotel floors, this function can, in principle, only be residential or collective accommodation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.D., A.T.-R., K.Z.-P. and M.B.; Methodology, W.D., A.T.-R., K.Z.-P. and M.B.; Validation, W.D., A.T.-R., K.Z.-P. and M.B.; Formal analysis, W.D., A.T.-R., K.Z.-P. and M.B.; Resources, W.D., A.T.-R., K.Z.-P. and M.B.; Data curation, W.D., A.T.-R., K.Z.-P. and M.B.; Writing—original draft, W.D.; Writing—review & editing, W.D., A.T.-R., K.Z.-P. and M.B.; Supervision, W.D.; Project administration, W.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the following architectural studios and companies for providing design materials (in alphabetical order): AKE Studio sp. z o.o. sp. k., CON-PROJECT sp. z.o.o., MIXD, Stobrawa Sp. z o.o.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lehman, H. The Polish Growth Miracle: Outcome of Persistent Reform Efforts. IZA Policy Pap. 2012, 40, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group’s GDP Statistics (Current US$). Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- World Economic Outlook Database. Groups and Aggregates Information (Last Updated: April 2025). Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2023/October/groups-and-aggregates (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Thomsen, A.; Van der Flier, K. Understanding obsolescence: A conceptual model for buildings. Build. Res. Inf. 2011, 39, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, S. UnDoing Buildings. Adaptive Reuse and Cultural Memory, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Masrabaye, F. Sustainable brownfield redevelopment and planning: Bibliometric and visual analysis. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Ding, Q.; Shi, Y. Current Status and Prospects of Ecological Restoration and Brownfield Reuse Research Based on Bibliometric Analysis: A Literature Review. Land 2025, 14, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballice, G.; Paykoc, E. Re-architecture of existing building stock with sustainable approach: The analysis of the City of Izmir. J. Environ. Prot. Ecol. 2014, 15, 1610–1618. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/291486155 (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Fisher-Gewirtzman, D. Adaptive Reuse Architecture Documentation and Analysis. J. Archit. Eng. Technol. 2016, 5, 1000172. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309519831 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Wong, L. Adaptive Reuse. Extending the Lives of Buildings, 1st ed.; Birkhäuser: Berlin, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lanz, F.; Pendlebury, J. Adaptive reuse: A critical review. J. Archit. 2022, 27, 441–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brania, N. Adaptation of Office Buildings for Residential Purposes as a Response to Problems in the Real Estate Market; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2023; pp. 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takva, Y.; Takva, Ç.; İlerisoy, Z.Y. Sustainable Adaptive Reuse Strategy Evaluation for Cultural Heritage Buildings. Int. J. Built Environ. Sustain. 2023, 10, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, V.W.Y.; Hao, J.J.L. Adaptive reuse in sustainable development. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2019, 19, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L. Adaptive Reuse in Architecture. In A Typological Index, 1st ed.; Birkhäuser: Berlin, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, G. Circular economy strategies for adaptive reuse of cultural heritage buildings to reduce environmental impacts. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 152, 104507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragança, L.; Mateus, R.; Koukkari, H. Building Sustainability Assessment. Sustainability 2010, 2, 2010–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, H.; Świerzawski, J. Assessing the environmental benefits of adaptive reuse in historical buildings. A case study of a life cycle assessment approach. Sustain. Environ. Int. J. Environ. Health Sustain. 2024, 10, 2375439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabak, P.; Sirel, A. Adaptive Reuse as a Tool for Sustainability: Tate Modern and Bilgi University Cases. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Contemporary Affairs in Architecture and Urbanism—ICCAUA, Analya, Turkey, 11–13 May 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalçınkaya, Ş. Iconic Buildings in Urban Sustainability. Eskişeh. Tech. Univ. J. Sci. Technol. A—Appl. Sci. Eng. 2020, 21, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowińska-Heim, J. Adaptive Reuse of Architectural Heritage and Its Role in the Post-Disaster Reconstruction of Urban Identity: Post-Communist Łódź. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cukrownia Żnin: A Sugar Factory Turned into a Hotel. Available online: https://www.cyrilzammit.com/design-diary/cukrownia-znin-a-sugar-factory-turned-into-a-hotel (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Kapera, I.; Cziomer, M.; Wolak, G. Hotele historyczne: Uwarunkowania rozwoju, znaczenie w turystyce i przykłady z Krakowa. Tur. Rozw. Reg. 2024, 22, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemkiewicz, T. Conservation Issues of Post-War Modernist Architecture in Poland. Archit. Urban. 2021, 55, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karczmarczyk, S.; Bereza, W.; Bubula, Ł.; Kowalcze, R.; Stężowski, P.; Oleś, K. Ekspertyza Konstrukcyjno-Budowlana Dotycząca Możliwości Adaptacji Istniejącego Układu Nośnego Budynku Dawnego Hotelu “Cracovia” Do Funkcji Muzealnych (Structural and Construction Expertise Concerning the Possibility of Adapting the Existing Load-Bearing Structure of the Former “Cracovia” Hotel Building for Museum Use), Kraków, Poland. 2020. Available online: https://sarp.krakow.pl/2023/05/04/hotel-cracovia/ (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Council of Europe. Convention for the Protection of the Architectural Heritage of Europe, Granada, Spain. 1985. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/168007a087 (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Council of Europe. Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society, Faro, Portugal. 2005. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/1680083746 (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- UNESCO. Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape, Paris, France. 2011. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/hul/ (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Sołtysik, M.J. (Ed.) Modernizm w Europie—Modernizm w Gdyni. Architektura Budynków Usług Społecznych w Europie Środkowej i Wschodniej XX Wieku (Modernism in Europe—Modernism in Gdynia. Architecture of Public Services Buildings in Central and Eastern Europe of the 20th Century); Urząd Miasta Gdyni, Wydział Architektury Politechniki Gdańskiej: Gdańsk, Poland, 2024; Available online: https://www.gdynia.pl/modernizm/cykl-modernizm-w-europie-modernizm-w-gdyni,7219/nr-9-architektura-budynkow-uslug-spolecznych-w-europie-srodkowej-i-wschodniej-xx-wieku-pl-eng,589999 (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Lewicki, J. Ocena wartości zabytków epoki modernizmu. Przeszłość—Teraźniejszość—Przyszłość (Assessment of the value of modernist-era monuments. Past—Present—Future). Wiad. Konserw. 2017, 49, 38–50. Available online: https://repozytorium.biblos.pk.edu.pl/redo/resources/28484/file/suwFiles/LewickiJ_OcenaWartosci.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- The Former Hotel Sudety Has Disappeared from the Landscape. Available online: https://jeleniagora.naszemiasto.pl/dawny-hotel-sudety-znika-z-krajobrazu-zobacz-zdjecia-z-rozbiorki-i-archiwalne-z-wnetrza/ar/c1p2-27719467 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Ciarkowski, B. Function resulting from the form—Adapting the post-war modernist architecture for new functional programs. Prot. Cult. Herit. 2020, 9, 15–28. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/347482343 (accessed on 20 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Carrero, R.; Malvárez, G.; Navas, F.; Tejada, M. Negative impacts of abandoned urbanisation projects in the Spanish coast and its regulation in the Law. J. Coast. Res. Spec. Issue 2009, 56, 1120–1124. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25737961 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Szafer, T.P. Nowa Architektura Polska Diariusz Lat 1966–1970 (New Polish Architecture, Diary of the Years 1966–1970), 1st ed.; Wydawnictwo Arkady: Warsaw, Poland, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Szafer, T.P. Polska Architektura Współczesna; Wydawnictwo Interpress: Warsaw, Poland, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Charytonow, E. Projektowanie Architektoniczne (Architectural Design), 4th ed.; Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne: Warsaw, Poland, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Szafer, T.P. Nowa Architektura Polska, Diariusz Lat 1971–1975 (New Polish Architecture, Diary of the Years 1971–1975), 1st ed.; Wydawnictwo Arkady: Warsaw, Poland, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Design Documentation for the Redevelopment of the Stobrawa Hotel into Apartments; Stobrawa sp.z o.o.: Kluczbork, Poland, 2022.

- Rumieńczyk, B. Hotel Forum—Relikt Przeszłości, Wyspa Wolności Czy Urzędniczy Pat? (Hotel Forum—A Relic of the Past, an Island of Freedom, or a Bureaucratic Stalemate?). Available online: https://wiadomosci.onet.pl/tylko-w-onecie/hotel-forum-relikt-przeszlosci-wyspa-wolnosci-czy-urzedniczy-pat/gcjf5m (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Białkiewicz, J.J. Controversies around protection of postwar modernism in Cracow upon the example of the Forum hotel. Wiad. Konserw.—J. Herit. Conserv. 2016, 47, 95–105. Available online: https://yadda.icm.edu.pl/baztech/element/bwmeta1.element.baztech-1b0f6010-22bf-433b-a1cb-99019ca6f7f3 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Architectural Design Documentation for the Redevelopment of the BRDA Hotel into a Residential Building with Commercial Spaces on the Ground Floor and First Floor; Con-Project sp. z.o.o.: Bydgoszcz, Poland, 2020.

- PN-EN ISO 6946:2017-10; Building Components and Building Elements—Thermal Resistance and Thermal Transmittance—Calculation Methods. PKN: Warsaw, Poland, 2020.

- Millard, W.B. Longevity and Sustainability of Curtain Walls. Archit. Rec. 2024, 212, 120–121. Available online: https://glifos.unis.edu.gt/digital/tesis/REVISTAS/AR/2024/2024005.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Świerzawski, J.; Kleszcz, J.; Hu, M.; Kmiecik, P. Quantifying the Environmental Benefit of Adaptive Reuse: A Case Study in Poland. In Proceedings of the ACSA 112th Annual Meeting: Disrupters on the Edge, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 14–16 March 2024; pp. 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London Energy Transformation Initiative (LETI). LETI Climate Emergency Design Guide: How New Buildings Can Meet UK Climate Change Targets, London, Great Britain. 2020. Available online: https://www.levittbernstein.co.uk/site/assets/files/3494/leti-climate-emergency-design-guide.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- PN-82/B-02003; Loads on Building Structures—Technological Variable Loads—Variable Actions During Exploitation and Assembling. PKN: Warsaw, Poland, 1982. Available online: https://arch.pg.edu.pl/documents/175777/69365302/Norma%20PN-82-B-02003%20Obci%C4%85%C5%BCenia-zmienne-technologiczne.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- PN-EN 1991-1-1:2004; Eurocode 1—Actions on Structures—Part 1-1: General Actions—Densities, Self-Weight, Imposed Loads for Buildings. PKN: Warsaw, Poland, 2004. Available online: https://www.phd.eng.br/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/en.1991.1.1.2002.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Ciarkowski, B. Unwanted heritage and its cultural potential. Values of modernist architecture from the times of the Polish People’s Republic. Maz. Stud. Reg. 2017, 22, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decision of the Małopolska Regional Monument Conservator in Kraków, Dated 4 November 2016, Concerning the Entry of a Cultural Property into the Register of Immovable Monuments, Reference Number: L.dz.OZKr.5140.A.58.2015.DW19. Available online: https://sarp.krakow.pl/2023/05/04/hotel-cracovia/ (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Resolution No. 2/22/2022 of the Provincial Council for the Protection of Monuments at the Małopolska Regional Monument Conservator, Dated 28 April 2022, Concerning the Plans to Adapt the Former “Cracovia” Hotel in Kraków for Museum Purposes. Available online: https://sarp.krakow.pl/2023/05/04/hotel-cracovia/ (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Błądek, Z. Hotele Bez Barier; Wydawnictwo Palladium Architekci—Błądek, Manikowski: Poznań, Poland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski, K. Włącznik 2.0. Projektowanie Bez Barier, 1st ed.; Fundacja Integracja: Warsaw, Poland, 2024; Available online: https://integracja.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/wlacznik_2_0_dostepny-.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2024).

- Błądek, Z. (Ed.) Nowoczesne Hotelarstwo. Od Projektowania Do Wyposażenia, (Modern Hotel Industry. From Design to Equipment), 2nd ed.; Oficyna Wydawniczo-Poligraficzna “Adam”: Warsaw, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Staehr, E.R.; Stevik, T.K.; Houck, L.D. Adaptability in the Building Process: A Multifaceted Perspective Across the Life Cycle of a Building. Buildings 2025, 15, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver Heckmann, O.; Budig, M.; Amanda Ng Qi Boon, A.; Hudert, M. Advancing Flexibility and Circular Design by Evaluative Computational Tools. In Proceedings of the Responsive Cities: Disrupting Through Circular Design Symposium 2019, Barcelona, Spain, 15–16 November 2019; pp. 132–145. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341852510 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Ahmed, M.; Abel-Rahman, A.; Ali, A.; Suzuki, M. Double Skin Façade: The State of Art on Building Energy Efficiency. J. Clean Energy Technol. 2016, 4, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LEED v5—Building Design and Construction (BD+C): New Construction and Major Renovations. Available online: https://www.usgbc.org/credits (accessed on 25 August 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.